Abstract

Gastric cancer is the fourth most common type of cancer, but diagnosis is often delayed. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy is currently the gold standard for evaluating gastric cancer. Also other imaging modalities, such as computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging are employed for identifying gastric cancer, but particularly for cancer staging. Ultrasound (US) is a first-line imaging modality used to examine organs in the abdomen, and during these examinations gastric cancer may be incidentally detected. Very few studies in the literature have investigated the role of US in gastric disease. However, more recently, some authors have reported on the use of contrast-enhanced US (CEUS) and US-elastography in gastric disease using both endoscopic and transabdominal approach. In this paper, we present a case of gastric cancer studied by CEUS and transabdominal US-elastography.

Keywords: Gastric cancer, Ultrasound, CEUS, US-elastography

Sommario

La neoplasia gastrica rappresenta il quarto tumore per incidenza, ma la sua identificazione è spesso ritardata. Al giorno d’oggi la esofagogastroduodenoscopia rappresenta l’indagine di elezione. Tra le metodiche di Imaging, la TC e la RM sono oggi usate per l’identificazione, ma soprattutto per lo staging. L’ecografia, è la metodica di primo livello nello studio per la patologia addominale e talvolta può indentificare incidentalmente dei tumori gastrici. In letteratura sono presenti pochi lavori riguardo il ruolo degli ultrasuoni per la patologia gastrica. Recentemente sono stati pubblicati dei lavori riguardanti l’uso della CEUS e dell’elastosonografia sia con approccio transendoscopico sia transaddominale. Presentiamo qui un caso di tumore gastrico studiato sia con CEUS che con elastosonografia.

Introduction

Gastric cancer is the fourth most common type of cancer with a global annual detection rate of about 930,000 cases [1], but the high death rate shows that patients are still diagnosed too late [2]. Symptoms are often uncharacteristic and diagnosis is therefore based on imaging investigation rather than clinical examination. Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is the current gold standard for evaluating gastric cancer, but this invasive procedure it is not well tolerated by all patients as it causes anxiety and discomfort. Ultrasound (US) is the first imaging modality used in patients with abdominal pain or other abdominal symptoms, and incidental detection of gastric cancer has been reported in connection with US examination. However, very few studies in the literature have investigated the role of US in the diagnosis of gastric cancer and there is limited evidence related to the use of contrast-enhanced US (CEUS) and US-elastography. In this paper, we present a case of gastric cancer studied by color Doppler US, CEUS and US-elastography.

Case description

A 67-year-old man was hospitalized due to fatigue, weight loss and iron deficiency anemia as well as abdominal discomfort. Abdominal US examination performed with high standard US equipment (Toshiba 500 and a 3–5 MHz convex probe) did not reveal focal lesions in the abdominal parenchymal organs, but an extensive and heterogeneous, hypoechoic mass of 12 cm in diameter in the larger curvature of the stomach was identified (Fig. 1a). Color Doppler showed vascularity within the mass (Fig. 1b) thus suggesting a neoplastic lesion. CEUS was performed immediately after conventional US. Intravenous administration of 2.4 ml of contrast media (Sonovue, Bracco, Milan, Italy) was followed by a bolus injection of 5 ml of saline solution.

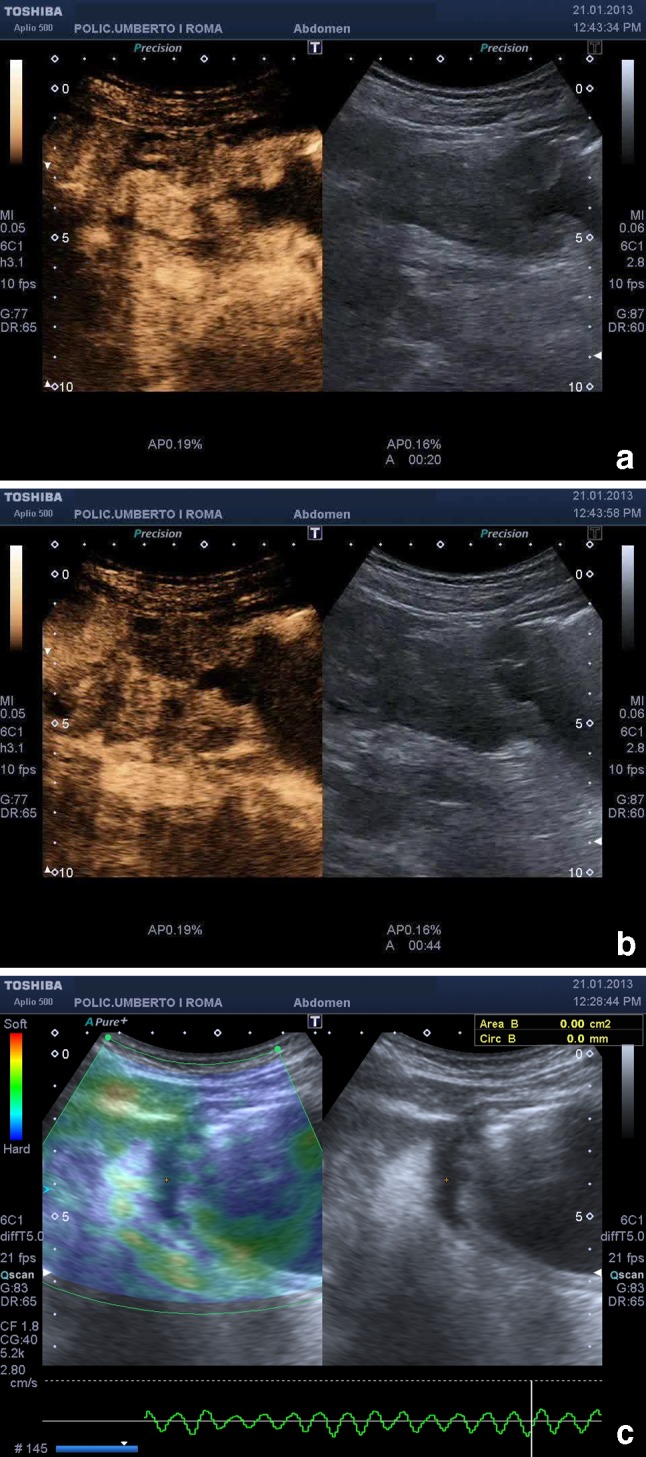

Fig. 1.

CEUS showed extensive and hypoechoic gastric wall thickening with intense enhancement and subsequent wash-out (a, b). At US-elastography the lesion appeared stiff (c) (blue)

CEUS examination was performed with the mechanical index set at 0.06–0.08, the focus set under the region of interest and dual mode imaging which combined fundamental and harmonic signals. The examination lasted 5 min starting from the moment of intravenous administration of contrast agent. CEUS examination of the stomach was completed 120 s after contrast injection with a study of the liver in order to rule out possible metastases. CEUS showed arterial uptake and venous wash-out (Fig. 1a, b). These events occurred at different times which could be correlated to the thickness of the gastric wall, thereby revealing pathological vascularization. Some perigastric lymph node metastases were also detected. At US-elastography the gastric lesion as well as the lymph nodes appeared stiff (Fig. 1c).

Endoscopic examination and biopsy confirmed the presence of extensive gastric cancer (adenocarcinoma). Subsequent staging using computed tomography (CT) confirmed US and CEUS findings. After surgery the patient had a normal postoperative course.

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. Informed consent was obtained from the patient before the examination and for the publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Discussion and conclusions

EGD is the current gold standard for evaluating gastric cancer (detection, characterization and biopsy under direct visual control). However, this invasive investigation is not well tolerated by all patients as it causes anxiety and discomfort.

One of the objectives of modern medicine is to identify widely accessible, well-tolerated, noninvasive, accurate diagnostic procedures. US is currently considered a first-line imaging modality for studying patients with unspecific abdominal pain, particularly to detect possible liver diseases. However, transabdominal US does not permit visualization of the entire stomach, such as the larger curvature and the sub-diaphragmatic segment, which are usually obscured by the presence of air. In these situations, the examination is considered inconclusive and endoscopy is therefore performed for possible tumor detection and endosonography for tumor staging, if required.

The introduction of US contrast agents and US-elastography has offered new possibilities for US investigation, also in the evaluation of gastrointestinal tract disorders, and CEUS with intravenous administration of contrast agent is therefore increasingly being performed [3, 4]. CEUS is mainly used in the detection and characterization of liver lesions, identification of infarction or ischemic areas, visualization of leaking blood vessels (in stenting or aneurysm surgery) and in the evaluation of response to oncologic treatment [5]. CEUS has also proved to be useful in the diagnosis of digestive tract inflammatory diseases such as hemorrhagic rectocolitis and Crohn’s disease including quantification and detection of prognostic indicators.

Badea et al. [6] have recently published their experience with CEUS in gastrointestinal tumors. They found that the vast majority of malignancies presented a typical CEUS behavior with arterial uptake of contrast media followed by a rather quick wash-out. They reported that contrast uptake was intense and heterogeneous in infiltrative malignant tumors, whereas two cases of gastrointestinal stromal tumor (GIST) presented intense, homogeneous uptake during the arterial phase and no wash-out [7]. It has been suggested that the typical behavior of gastric cancer reported by Badea could be correlated with the presence of arteriovenous shunts and a well-represented circulatory bed. In our patient, US investigation yielded similar results. Grey-scale US identified an extensive and hypoechoic gastric lesion associated with rounded, hypoechoic perigastric lymph nodes, and after contrast injection there was arterial uptake of contrast media followed by a rather quick wash-out. Another important issue to be emphasized is that during the portal and late phase of CEUS it is possible to evaluate the liver parenchyma to rule out possible metastases. CEUS has been reported to be accurate and roughly comparable to multi-detector CT or MRI [5].

In our patient, we furthermore performed transabdominal elastography which confirmed that the extensive lesion and the lymph nodes were very stiff. Our findings were in accordance with the results reported in the literature [8, 9]. It is reported that malignancy should be suspected in the presence of a lesion measuring >30–40 mm in diameter, with irregular outer contours or ulceration and an inhomogeneous structure with anechoic (cystic) internal structures and lymph node infiltration.

Our results show that transabdominal US may allow detection and characterization of gastric tumors. However, there are some limitations linked to US, such as the patient’s constitution, bloating and poor compliance.

Due to the high diagnostic accuracy of EGD, this method is undoubtedly the current gold standard for the diagnosis of gastric carcinoma. Oral administration of contrast agent may be indicated to overcome the inadequate distension of the gastric wall, while CEUS can identify parameters indicating the nature of the tumor. CEUS examination provides a better definition of the lesion by identifying neoplastic blood circulation, if any. CEUS and US-elastography are simple and easy to perform and may therefore become additional tools for a more accurate evaluation of gastrointestinal cancer also in patients with comorbid conditions.

Conflict of interest

Vito Cantisani, Antonello Rubini and Guglielmo Miniagio declare that they have no conflict of interest related to this paper.

Informed consent

All procedures followed were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000 (5). All patients provided written informed consent to enrolment in the study and to the inclusion in this article of information that could potentially lead to their identification.

Human and animal studies

The Study was conducted in accordance with all institutional and national guidelines for the care and use of laboratory animals.

References

- 1.Parkin DM, Bray F, Ferlay J, Pisani P (2002) Global cancer statistics, 2002 (2005) CA Cancer J Clin 55:74–108 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Hohenberger P, Gretschel S. Gastric cancer. Lancet. 2003;362:305–315. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13975-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Claudon M, Dietrich CF, Choi BI, Cosgrove DO, Kudo M, Nolsøe CP, et al. Guidelines and good clinical practice recommendations for Contrast Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS) in the liver—update 2012: A WFUMB-EFSUMB initiative in cooperation with representatives of AFSUMB, AIUM, ASUM, FLAUS and ICUS. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2013;39(2):187–210. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2012.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Piscaglia F, Nolsøe C, Dietrich CF, Cosgrove DO, Gilja OH, Bachmann Nielsen M. The EFSUMB Guidelines and Recommendations on the Clinical Practice of Contrast Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS): update 2011 on non-hepatic applications. Ultraschall Med. 2012;33(1):33–59. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1281676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cantisani V, Ricci P, Erturk M, Pagliara E, Drudi F, Calliada F, et al. Detection of hepatic metastases from colorectal cancer: prospective evaluation of gray scale US versus SonoVue® low mechanical index real time-enhanced US as compared with multidetector-CT or Gd-BOPTA-MRI. Ultraschall Med. 2010;31(5):500–505. doi: 10.1055/s-0028-1109751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Badea R, Socaciu M, Ciobanu L, Hagiu C, Golea A. Contrast-enhanced ultrasonography (CEUS) for the evaluation of the inflammation of the digestive tract wall. J Gastrointestin Liver Dis. 2010;19:439–444. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Badea R, Neciu C, Iancu C, Al Hajar N, Pojoga C, Botan E (2012) The role of i.v. and oral contrast enhanced ultrasonography in the characterization of gastric tumors. A preliminary study. Med Ultrason 14(3):197–203 [PubMed]

- 8.Dietrich CF, Jenssen C, Hocke M, Cui XW, Woenckhaus M, Ignee A. Imaging of gastrointestinal stromal tumours with modern ultrasound techniques—a pictorial essay. Z Gastroenterol. 2012;50(5):457–467. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1282076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jenssen C, Dietrich CF. Endoscopic ultrasound of gastrointestinal subepithelial lesions. Ultraschall Med. 2008;29(3):236–256. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1027388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]