Abstract

Two methods commonly used to quantify ectoparasites on live birds are visual examination and dust-ruffling. Visual examination provides an estimate of ectoparasite abundance based on an observer’s timed inspection of various body regions on a bird. Dust-ruffling involves application of insecticidal powder to feathers that are then ruffled to dislodge ectoparasites onto a collection surface where they can then be counted. Despite the common use of these methods in the field, the proportion of actual ectoparasites they account for has only been tested with Rock Pigeons (Columba livia), a relatively large-bodied species (238–302 g) with dense plumage. We tested the accuracy of the two methods using European Starlings (Sturnus vulgaris; ~75 g). We first quantified the number of lice (Brueelia nebulosa) on starlings using visual examination, followed immediately by dust-ruffling. Birds were then euthanized and the proportion of lice accounted for by each method was compared to the total number of lice on each bird as determined with a body-washing method. Visual examination and dust-ruffling each accounted for a relatively small proportion of total lice (14% and 16%, respectively), but both were still significant predictors of abundance. The number of lice observed by visual examination accounted for 68% of the variation in total abundance. Similarly, the number of lice recovered by dust-ruffling accounted for 72% of the variation in total abundance. Our results show that both methods can be used to reliably quantify the abundance of lice on European Starlings and other similar-sized passerines.

Keywords: Brueelia, European Starling, feather lice, parasite, Phthiraptera, pyrethrin, Sturnus vulgaris

Several methods can be used to quantify ectoparasites on birds (Clayton and Walther, 1997), ranging from those used with dead birds, such as body washing, to those used with live birds, such as visual examination and dust-ruffling (Clayton and Drown 2001). Visual examination involves timed counts of ectoparasites on different host body regions, but without removing any parasites. Individual counts are then either summed for an overall estimate of ectoparasite abundance, or used in multiple regression models that predict total abundance (Clayton and Drown 2001). An advantage of visual examination is that it is essentially a form of sampling with replacement that can be used repeatedly over time to track changes in ectoparasite load.

Dust-ruffling is a more invasive technique that removes ectoparasites from hosts (sampling without replacement). This method involves application of an insecticidal powder, often pyrethrin-based, followed by ruffling of the feathers over a clean surface for one or more timed intervals (Walther and Clayton 1997). Ectoparasites are then counted immediately, or preserved and counted later.

Using a rarefaction approach where birds were ruffled repeatedly to the point of diminishing returns, Walther and Clayton (1997) showed that dust-ruffling provided reliable estimates of lice on Common Swifts (Apus apus) and Rock Pigeons (Columba livia). However, these authors did not estimate the proportion of total lice accounted for by dust-ruffling. To date, the proportion of lice accounted for by dust-ruffling and other methods has been determined in only one study. Clayton and Drown (2001) compared the number of lice accounted for by dust-ruffling, visual examination, and other methods to the total number of lice on feral Rock Pigeons.

In recent years, ornithologists have used dust-ruffling and visual examination to estimate the abundance of lice on different species of birds, including passerines (Shutler et al. 2004, Balakrishnan and Sorenson 2007, Carrillo et al. 2007, Gomez-Diaz et al. 2008, Londono et al. 2008, Sychra et al. 2008, MacLeod et al. 2010, Fairn et al. 2012). However, differences between species (e.g., size, plumage density, and feather oiliness) may affect the accuracy of these methods. For example, visual examination and dust-ruffling involve manipulating the plumage with fingers and forceps and the smaller size of many passerines may make this more difficult, possibly reducing accuracy.

We compared the proportion of lice accounted for by visual examination and dust-ruffling to the total number of lice on European Starlings (Sturnus vulgaris). Starlings weigh ~75 gms (Feare 1985), which is 25–30% of the mass of Rock Pigeon (~238–302 g; Gibbs et al. 2001). The total number of lice was determined using a body-washing method that accounts for 99% of the louse population (Clayton and Drown 2001). Using this approach, we determined the fraction of lice observed or recovered by each of the two methods, and whether that fraction was a statistically significant predictor of total louse abundance.

METHODS

We used European Starlings and their lice (Brueelia nebulosa) to test the methods. Brueelia nebulosa was the only species of ectoparasite found on birds in our study. We did not include feather mites because recent studies indicate that they are commensals, rather than parasites (Proctor 2003, Galvan et al. 2012). Brueelia nebulosa (Phthiraptera: Ischnocera) is a common species of louse found on European Starlings (Boyd 1951, Kettle 1983). Brueelia are 1.5–2.0 mm long and are permanent ectoparasites that spend all stages of their life cycle on the body of hosts (Boyd 1951, Williams 1981). Like other Ischnoceran feather lice, B. nebulosa feed on feathers and use their tarsal claws to cling to feathers (Bush et al. 2006).

We captured 20 starlings with walk-in traps in Salt Lake City, Utah. Birds were housed separately or in pairs in wire-mesh cages (45.7 × 53.3 × 58.4 cm) in a shed-like aviary on the roof of our biology building. Birds were fed a mixture of ground dog food (Purina large breed puppy chow, Nestlé Purina, St. Louis, MO), turkey starter, wheat germ, and vitamins, as well as fresh vegetables and mealworms ad libitum. Temperatures in the animal facility varied from 21 to 25°C and relative humidity from 50 to 70%.

Birds were examined in the open doorway of the aviary, providing both natural light and protection from wind. Dust-ruffling cannot be performed in windy conditions because both the dusting powder and dislodged ectoparasites are blown off the collection surface (Clayton and Drown 2001). All data were collected on a single day from 11:00–15:00 under sunny, calm conditions. Magnification was not necessary during visual examination because both nymphal and adult lice were visible with the naked eye. All data were collected by JAHK. Each bird was visually examined, dust-ruffled, then euthanized and frozen in a separate ziplock bag.

Visual examination

Birds were held on their back in one hand while the other hand was used to manipulate the bird. Each bird was examined for 3 min and the number of lice recorded. The wings and tail were fully extended, fanned out, and examined for 30 sec each. Both the dorsal and ventral sides of each flight feather (wings and tail) were examined. The shorter, denser feathers of the back, nape, keel, and vent areas were examined for 60 sec per region. The feathers on these areas were lifted with forceps to systematically examine the dorsal and ventral sides. Our previous observations revealed that most B. nebulosa on starlings are located on the rump and nape. Few lice were observed on the wings or tail.

Dust-ruffling

Immediately after visual examination, each bird was dust-ruffled in the same protected aviary space. Dust-ruffling was performed over a cafeteria tray lined with clean, white paper. We used Z3 Flea and Tick powder (Zema, Research Triangle Park, NC) that contains 0.1% pyrethrins and 1.0% piperonyl butoxide, a synergist. This is the same brand of dusting powder used by Clayton and Drown (2001). Pyrethrins have been shown to have no effect on the survival of nestling or adult birds (Clayton and Tompkins 1995). Approximately ~1–2 g of powder was worked into the plumage over the entire body, including the head, which took about 3 min. Care was taken to avoid the eyes and mouth. Immediately after application of the powder, the plumage was gently ruffled for 2 min over the collection surface. A single bout of ruffling was performed to minimize stress to the birds (see Discussion). The contents of the white paper were then funneled into a vial with 95% ethanol. Vials were stored in a −20°C freezer until further processing. For counting, the contents of each vial were emptied onto white filter paper (bleached coffee filters). The wet (semi-transparent) filter paper was then placed over a plastic grid and systematically examined under 10× magnification with a dissecting microscope and the lice counted.

Body-washing

Immediately after dust-ruffling, birds were euthanized using Halothane (inhalation anesthetic), placed in individual ziplock bags, and frozen. At a later date, each bird was thawed and washed (Clayton and Drown 2001). For washing, each bird was placed in a 1-liter, unused paint can with 30 ml of dishwashing liquid (Palmolive Ultra, Colgate-Palmolive Co., New York, NY) and deionized (DI) water. The can was then placed on an industrial paint shaker and shaken for 10 min. The bird was removed from the can and rinsed with DI water over a large (19-liter) bucket. The bird was then placed back in the can with DI water (only), and then shaken for an additional 10 min. The bird was removed from the can and again rinsed with DI water over a 19-liter bucket. The paint can was also rinsed thoroughly into the bucket. Following collection of the rinse, the final contents of the collection bucket were strained through a funnel containing white filter paper. Finally, the filter paper was placed over the plastic grid and all lice counted under 10× magnification with the dissecting scope. Care was taken during the washing process to avoiding losing lice, or mixing lice between birds.

Statistical analysis

Count data from visual examination and dust-ruffling were log transformed (log (number of lice +1)) to achieve normality. We used linear regression to compare the accuracy of each method in predicting total louse abundance, which was the sum of lice collected by dust-ruffling and body washing. Two separate sets of analyses are presented, one where only infested birds were used to estimate the accuracy of each method, and a second one where all (infested and uninfested) birds were used. Analyses were performed in Prism v. 5.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA). Values are presented as means ± SE.

RESULTS

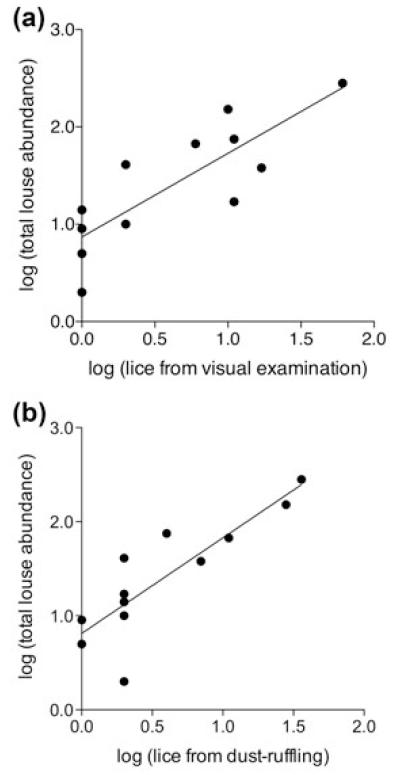

Twelve of the 20 birds (60%) were parasitized by lice. The mean number of lice on infested birds was 58.3 ± 23.7 (range = 1 – 280). Although the mean percentage of total lice observed during visual examination was only 14.0 ± 5.7%, this method accounted for 68% of the variation in lice among infested birds (linear regression r2 = 0.68, P = 0.001, N = 12; Fig. 1a). Dust-ruffling removed only 16.1 ± 7.8% of total lice, but the method accounted for 72% of the variation in lice among infested birds (r2 = 0.72, P = 0.0004, N = 12; Fig. 1b).

Fig. 1.

Linear regression of total louse abundance on the number of lice observed or collected on infested birds using (a) visual examination and (b) dust-ruffling methods. Each point represents a single bird.

Including uninfested and infested birds in the analyses slightly improved the ability of each method to predict total louse number. When all 20 birds were included, visual examination accounted for 72% of the variation in total lice among birds (linear regression r2 = 0.72, P < 0.0001, N = 20). Dust-ruffling accounted for 76% of the variation in total lice among birds (r2 = 0.76, P < 0.0001, N = 20).

DISCUSSION

Clayton and Drown (2001) found that ~9% of Rock Pigeon lice were observed by visual examination, which predicted 70% of the variation in louse abundance assessed by body washing. Using similar methods, we observed 14% of total lice during visual examination of starlings. Although this is a relatively small proportion of the total number of lice, the method predicted 68% of variation in total louse abundance. Thus, visual examination predicted the abundance of lice on starlings nearly as well as it did for pigeons.

Clayton and Drown (2001) found that dust-ruffling recovered 33% of lice on pigeons, which predicted 88% of the variation in louse abundance. We found that dust-ruffling recovered 16% of lice from starlings, and predicted 72% of the variation in total louse abundance. Thus, dust-ruffling accounted for more variation in total louse abundance on starlings than visual examination. Although dust-ruffling was a significant predictor of total louse abundance on starlings, the method did not account for as much variation in lice on starlings as it did for pigeons (Clayton and Drown 2001). One possible explanation for the differences between our results and those of Clayton and Drown (2001) is that the smaller size of starlings may have made handling and dust-ruffling more difficult, decreasing the number of lice recovered. Additional testing of these methods on even smaller birds, such as House Sparrows (Passer domesticus), would be useful.

Depending on the birds or ectoparasites being sampled, several modifications may be necessary to maintain or improve the accuracy of these methods. For example, additional time may be needed when inspecting or ruffling birds with large crests or long tails. In addition, seeing lice in newly grown plumage following molt is more difficult, at least on pigeons (Moyer et al. 2002). Some feather lice eat the downy regions of feathers, making it easier to see lice over time. In addition, to better observe lice in regions with stiff or dense feathers, such as those on the back or breast adjacent to the keel, we recommend using forceps.

The amount of flea and tick powder used for dust ruffling may also vary with plumage characteristics and bird size. We used ~1–2 g, which was sufficient to cover the plumage of starlings with a light coating of dust. We recommend that investigators determine at the outset of a study how much dust is required to achieve a light coating, depending on the size and plumage of the study species. In addition, the plumage of some birds in our study was oily and appeared to absorb the dusting powder. We used about the same amount of powder on each starling to keep our protocol consistent among birds. However, our results may have been influenced by the oiliness of the plumage of some birds. Dust-ruffling may be even more accurate on birds with plumage that is less oily.

The amount of time spent on visual examination and dust-ruffling has varied among studies (Lindell et al. 2002, Whiteman and Parker 2004, Balakrishnan and Sorenson 2007, Martin et al. 2007). Long observation times or repeated bouts of ruffling may stress birds (Silverin 1998). In many species, stress hormone levels increase significantly after only 3 min of handling (Silverin 1998, Müuller et al. 2006). To reduce stress, our protocol included a maximum of 3 min for visual examination and 5 min for dust-ruffling (including application of dust and ruffling). With visual examination, 3 min was sufficient to systematically inspect all regions of the body without undo stress to the bird (i.e., panting). Repeated bouts of ruffling, to the point of diminishing returns, can allow recovery of greater numbers of ectoparasites than a single bout (Walther and Clayton 1997, Poiani et al. 2000). However, because repeated bouts of ruffling may not always be possible (Carleton et al. 2012), we chose to test the efficacy of a single bout of ruffling. Our results show that even a single bout is sufficient to estimate total louse abundance.

Modifications of visual examination or dust-ruffling techniques may also be necessary depending on the type of ectoparasite being quantified (Marshall 1981). Both visual examination and dust-ruffling work best for permanent ectoparasites, such as lice, that spend their entire life cycle on hosts. Ectoparasites such as fleas or flies that have stages off the host, and those that can more easily escape during handling, such as hippoboscid flies, are not as easily quantified using these methods (Clayton and Drown 2001). To quantify non-permanent ectoparasites using dust-ruffling, birds should be placed in a paper bag immediately after application of dusting powder to increase the likelihood that vagile ectoparasites will be killed by the dust.

Microhabitat use by parasites should also be considered (Johnson et al. 2005). For example, ectoparasites like ticks that feed on the blood of their hosts may be difficult to dislodge if they are attached. In addition, species of lice that live inside the shafts of feathers will not be observed during visual examination or removed by dust-ruffling (Walther and Clayton 1997, Moyer et al. 2002). Other methods, such as KOH dissolution, may be necessary to quantify these types of ectoparasites (Clayton and Drown 2001).

In summary, our results show that both visual examination and dust-ruffling are reliable methods for quantifying lice abundance on European Starlings and presumably other similarsized passerines. However, awareness of host and parasite biology is important in determining the best procedure for quantifying ectoparasite abundance in other systems.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank F. Goller, S. Nielsen, and T. Riede for their assistance in the field, and S. Bush for helpful comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by a Frank M. Chapman award to JAHK, and NSF grant DEB-0816877 to DHC. All procedures were approved by the University of Utah Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (protocol #05–08009).

LITERATURE CITED

- Balakrishnan CN, Sorenson MD. Dispersal ecology versus host specialization as determinants of ectoparasite distribution in brood parasitic indigobirds and their estrildid finch hosts. Molecular Ecology. 2007;16:217–229. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2006.03142.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd EM. A survey of parasitism of the starling Sturnus vulgaris L. in North America. Journal of Parasitology. 1951;37:56–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bush SE, Sohn E, Clayton DH. Ecomorphology of parasite attachment: experiments with feather lice. Journal of Parasitology. 2006;92:25–31. doi: 10.1645/GE-612R.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carleton RE, Mertins JW, Yabsley MJ. Parasites and pathogens of Eastern Bluebirds (Sialia sialis): a field survey of a population nesting within a grass-dominated agricultural habitat in Georgia, U.S.A., with a review of previous records. Comparative Parasitology. 2012;79:30–43. [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo CM, Valera F, Barbosa A, Moreno E. Thriving in an arid environment: high prevalence of avian lice in low humidity conditions. Ecoscience. 2007;14:241–249. [Google Scholar]

- Clayton DH, Drown DM. Critical evaluation of five methods for quantifying chewing lice (Insecta: Phthiraptera) Journal of Parasitology. 2001;87:1291–1300. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2001)087[1291:CEOFMF]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton DH, Tompkins DM. Comparative effects of mites and lice on the reproductive success of Rock Doves (Columba livia) Parasitology. 1995;110:195–206. doi: 10.1017/s0031182000063964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clayton DH, Walther BA. Collection and quantification of arthropod parasites of birds. In: Clayton DH, Moore AJ, editors. Host-parasite evolution: general principles and avian models. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 1997. pp. 419–440. [Google Scholar]

- Feare CJ. The starling. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Fairn ER, Mclellan NR, Shutler D. Are lice associated with Ring-billed Gull chick immune responses? Waterbirds. 2012;35:164–169. [Google Scholar]

- Galvan I, Aguilera E, Atienzar F, Barba E, Blanco G, Canto JL, Cortes V, FRIAS O, Kovacs I, Melendez L, MØLLER AP, Monros JS, Pap PL, Piculo R, Senar JC, Serrano D, Tella JL, Vagasi CI, Vogeli M, Jovani R. Feather mites (Acari: Astigmata) and body condition of their avian hosts: a large correlative study. Journal of Avian Biology. 2012;43:273–279. [Google Scholar]

- Gibbs D, Barnes E, Cox J. Pigeons and doves: a guide to the pigeons and doves of the world. Yale University Press; New Haven, CT: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Gomez-Diaz E, Navarro J, Gonzalez-Solis J. Ectoparasite community structure on three closely related seabird hosts: a multiscale approach combining ecological and genetic data. Ecography. 2008;31:477–489. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson KP, Bush SE, Clayton DH. Correlated evolution of host and parasite body size: tests of Harrison’s rule using birds and lice. Evolution. 2005;59:1744–1753. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kettle PR. The seasonal incidence of parasitism by Phthiraptera on starlings (Sturnus vulgaris) in England. New Zealand Entomologist. 1983;7:403–408. [Google Scholar]

- Lindell CA, Gavin TA, Price RD, Sanders AL. Chewing louse distributions on two Neotropical thrush species. Comparative Parasitology. 2002;69:212–217. [Google Scholar]

- Londono GA, Levey DJ, Robinson SK. Effects of temperature and food on incubation behavior of the Northern Mocking-bird, Mimus polyglottos. Animal Behaviour. 2008;76:669–677. [Google Scholar]

- Macleod CJ, Paterson AM, Tompkins DM, Duncan RP. Parasites lost—do invaders miss the boat or drown on arrival? Ecology Letters. 2010;13:516–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1461-0248.2010.01446.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall AG. The ecology of ectoparasitic insects. Academic Press; London, UK: 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Martin LB, Pless MI, Wikelski MC. Greater seasonal variation in blood and ectoparasite infections in a temperate than a tropical population of House Sparrows Passer domesticus in North America. Ibis. 2007;149:419–423. [Google Scholar]

- Moyer BR, Gardiner DW, Clayton DH. Impact of feather molt on ectoparasites: looks can be deceiving. Oecologia. 2002;131:203–210. doi: 10.1007/s00442-002-0877-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- C Müller,, Jenni-Eiermann S, Blondel J, Perret P, Caro SP, Lambrechts M, Jenni L. Effect of human presence and handling on circulating corticosterone levels in breeding Blue Tits (Parus caeruleus) General and Comparative Endocrinology. 2006;148:163–171. doi: 10.1016/j.ygcen.2006.02.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poiani1 A, Goldsmith AR, Evans MR. Ectoparasites of House Sparrows (Passer domesticus): an experimental test of the immunocompetence handicap hypothesis and a new model. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 2000;47:230–242. [Google Scholar]

- Proctor HC. Feather mites (Acari: Astigmata): ecology, behavior, and evolution. Annual Reviews in Entomology. 2003;48:185–209. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ento.48.091801.112725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shutler D, Mullie A, Clark RG. Tree Swallow reproductive investment, stress, and parasites. Canadian Journal of Zoology. 2004;82:442–448. [Google Scholar]

- Silverin B. Stress response in birds. Poultry and Avian Biology Reviews. 1998;9:153–168. [Google Scholar]

- Sychra O, Literak I, Podzemny P, Benedikt V. Insect ectoparasites from wild passerine birds in the Czech Republic. Parasite. 2008;15:599–604. doi: 10.1051/parasite/2008154599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walther BA, Clayton DH. Dust-ruffling: a simple method for quantifying ectoparasite loads of live birds. Journal of Field Ornithology. 1997;68:509–518. [Google Scholar]

- Whiteman NK, Parker PG. Effects of host sociality on ectoparasite population biology. Journal of Parasitology. 2004;90:939–947. doi: 10.1645/GE-310R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams NS. The Brueelia (Mallophaga: Philopteridae) of the Meropidae (Aves: Coraciiformes) Journal of the Kansas Entomological Society. 1981;54:510–518. [Google Scholar]