Abstract

Because states play such a prominent role in the U.S. health care system, they have long grappled with how to best control health care costs while maintaining high quality of care. There are many policy tools available to address efficiency and quality concerns — from pure state regulation to market-oriented competition designs. Given public discourse and official party platforms, one would assume that states controlled by Democrats would be more likely to adopt regulatory reforms. This study examines whether party control, as well as other economic and political factors, is associated with adopting wage pass-through (WPT) policies, which direct a portion of Medicaid reimbursement or its increase toward nursing home staff in an effort to reduce staff turnover, thereby increasing efficiency and the quality of care provided. Contrary to expectations, results indicate that states with Republican governors were against WPT adoption only when for-profit industry pressure increased; otherwise, they were more likely to favor adoption than their Democratic counterparts. This suggests a more complex relationship between partisanship and state-level policy adoption than is typically assumed. Results also indicate that state officials reacted predictably to prevailing political and economic conditions affecting state fiscal-year decisions but required sufficient governing capacity to successfully integrate WPTs into existing reimbursement system arrangements. This suggests that WPTs represent a hybrid between comprehensive and incremental policy change.

Medicaid is the major purchaser of nursing home care in the United States, accounting for 40.6 percent of total spending in 2008 (Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services [CMS] 2010). By 2019 total Medicaid nursing home spending is expected to reach $105 billion, more than two times that spent by the program in 2004 (ibid.). Several mechanisms have been put in place to promote the quality of care delivered to nursing home residents paid for by Medicaid. On the one hand, nursing homes must comply with federal Medicaid regulations to be eligible for reimbursement. This includes being subject to inspections of patients’ records, reviews of procedures and policies, some observations of care practices and patients, and the release of publicly available information (Harrington, Mullan, and Carrillo 2004; Miller and Mor 2008). In addition to contracting with CMS to conduct the pertinent inspections, state officials attempt to promote quality through the ways they elect to reimburse nursing facilities under Medicaid (Miller et al. 2009). This is reflected in the promulgation of payment system attributes such as pay for performance. It includes incentives to bolster the level and type of staffing available as well.

Key to promoting quality is recruiting and retaining a well-trained, stable workforce, including both professional staff such as registered nurses (RNs), licensed practical nurses (LPNs), physicians, therapists, and administrators, and paraprofessional staff (e.g., certified nurse aides [CNAs]) who provide the bulk of care on a day-to-day basis. The importance of direct-care staff is reflected in a large body of research demonstrating a relationship between the type, quantity, and organization of staffing and the quality of care received (Bostick et al. 2006; CMS 2002; Harrington, Zimmerman, et al. 2000). Nonetheless, the fifty-two thousand just five years earlier (American Health Care staff turnover rate for CNAs was 65.6 percent in 2007; the number of vacant positions was approximately sixty thousand, up from Association 2008). In all, the number of CNAs has declined by more than one hundred thousand full-time equivalents (FTEs) since 1992 (Miller and Mor 2007). This is despite significant growth in the number of nursing home residents, not to mention the average number of beds per facility and proportion of residents eighty-five years and older with activity of daily living limitations (Decker 2005; Jones et al. 2009; Centers for Disease Control and National Center for Health Statistics 2010). It is projected that the United States will need close to 1.5 million additional paraprofessional staff, including 422,000 nurse aides, orderlies, and attendants, between 2008 and 2018 alone (U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics [BLS] 2010). The projected supply, however, is not expected to keep up with the demand.

Challenges in recruiting and retaining CNAs derive from several factors. There is widespread public perception that care for elderly people, particularly in nursing homes, is low quality (Kaiser Family Foundation 2005). This also is emotionally and physically demanding work, with high rates of injury and assault, for example. Insufficient training and continuing education, limited autonomy, perceived lack of value and respect, and few opportunities for career advancement contribute as well (Bowers, Esmond, and Jacobson 2003; CMS 2002; Mickus, Luz, and Hogan 2004). The long-term-care workforce is also among the most poorly compensated in the nation. This is especially true of nurse aides, who, with a median hourly wage of $9.13 in 2005 (and even lower starting wages of $7.96), are more than twice as likely as other workers to be low income or live in poverty (68 percent vs. 30 percent) (Baughman and Smith 2007; Smith and Baughman 2007). Very few are offered health insurance coverage or other benefits from their employers (e.g., vacation time, tuition assistance, pension coverage, or child care) (Fishman et al. 2004; Smith and Baughman 2007). With wages and benefits so low, nursing homes find it difficult to compete with fast-food restaurants and other low-wage service sectors with less-challenging work environments. They also find it challenging to compete with hospitals, which typically pay substantially more for similar work (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services 2003).

Given the potential importance of compensation for enhancing recruitment and retention, state governments have sought to improve staffing levels through wage pass-through (WPT) programs that require that a portion of Medicaid reimbursement or its increase be directed toward staffing, through enhanced wages or benefits or increasing the number of nurse aides or other direct-care workers. The purpose of this study is to examine what factors promote or impede state adoption of a WPT initiative in a given year. Although WPT programs are the primary means through which states have sought to improve staffing and, in turn, quality, no systematic empirical research has been conducted to examine the comparative influence of external and internal factors on the adoption decision. That WPT adoption may be related to such factors is reflected in prior research identifying significant associations between political, economic, programmatic, interstate, and federal-level factors with policies affecting Medicaid generally and nursing home reimbursement specifically (Allen, Pettus, and Haider-Markel 2004; Barrilleaux and Miller 1988; Davidson 1978; Grogan 1999; Harrington, Mullan, and Carrillo 2004; Harrington, Carrillo, et al. 2000; Kane et al. 1998; Kousser 2002; Miller 2005, 2006a, 2006b; Miller and Wang 2009a, 2009b; Pracht 2007; Swan, Harrington, and Pickard 2000; Swan et al. 1997, 2001).

A Primer on Wage Pass-through

Prevailing research suggests a relationship between Medicaid payment levels and CNA wages, benefits, satisfaction, and overall levels of staffing (Bishop et al. 2009; CMS 2002; Harrington, Swan, and Carrillo 2007). Thus one policy option to promote staffing might be to increase the Medicaid per diem rates received by facilities. That this may be effective in doing so is reflected in Medicaid nursing home reimbursement rates being considerably lower than Medicare and private-pay rates and, according to the nursing home industry, oftentimes lower than the actual costs of providing care (Eljay 2009). That this may not be effective is reflected in the rather modest statistical relationships found between actual increases in Medicaid payments and staffing (Feng et al. 2008; Harrington, Swan, and Carrillo 2007). It also is unclear whether nursing homes would direct additional dollars to staffing rather than other areas. A more targeted approach may be necessary.

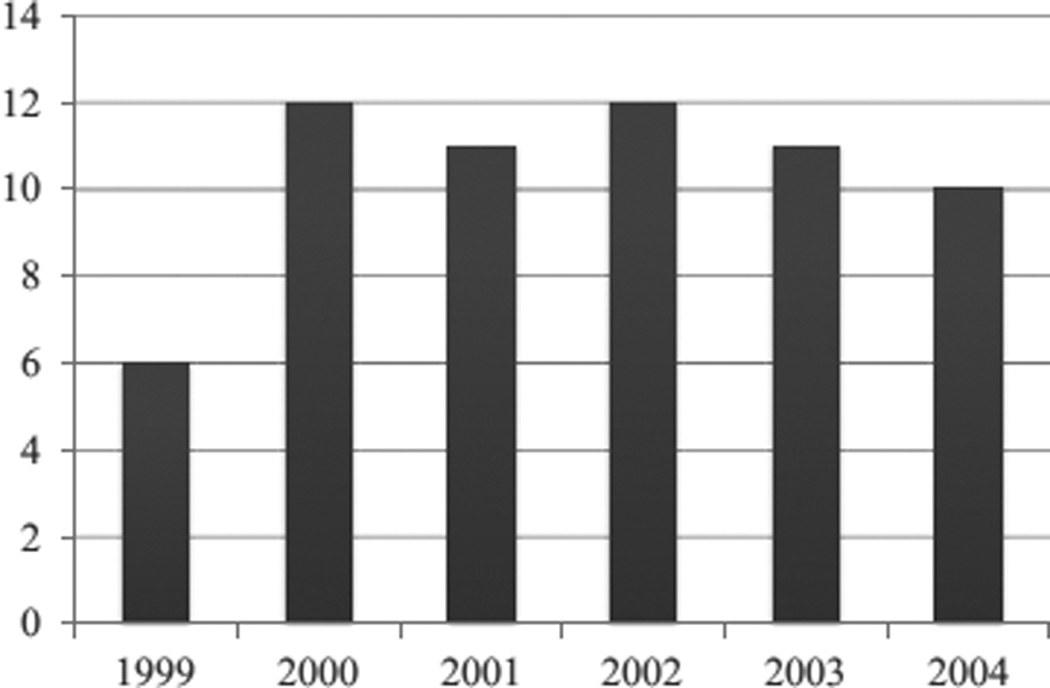

WPT programs earmark additional Medicaid reimbursement for increasing compensation for direct-care workers. Virtually all Medicaid programs reimburse nursing homes using cost centers that specify how much of the total payment should be directed to such areas as nursing, housekeeping, capital, and administration. Those states earmarking more money for staffing set higher limits on how much they are willing to pay for nursing than the other cost categories specified. Overall, the number of states with WPTs for nursing home reimbursement has varied from year to year, ranging from six in 1999 to twelve in 2000, eleven in 2001, twelve in 2002, eleven in 2003, and ten in 2004 (fig. 1). There also has been quite a bit of variation in which states have chosen to adopt a WPT in any given year. Indeed, only one state (Delaware) had a WPT throughout this entire time period and only two (Texas and Vermont) in four of the five years. In all, twenty-three states have implemented a WPT during at least one of the years reported.

Figure 1.

Medicaid Wage Pass-through Adoption for Nursing Homes, 1999–2004

Source: Brown University Survey of State Long-Term Care Policies (Grabowski et al. 2008)

WPT initiatives typically take one of two forms: (1) specifying that a certain dollar amount, say, $0.50 to $4.00 per day, be designated per staff hour (or patient day), or (2) requiring that a specified proportion of a payment increase be used for wages and benefits (North Carolina Division of Facility Services 2000). Especially important are auditing and enforcement procedures, which although potentially burdensome, ensure that additional funding is spent on the anticipated targets. There is concern that facilities might fail to direct additional Medicaid dollars to workers as intended (Trewyn 2001).

Texas has an extensive WPT program. Although voluntary, 85 percent of Medicaid-participating facilities have elected to enroll (Miller et al. 2009). Enrolled facilities agree to keep direct-care staffing above minimum standards. They also submit annual reports verifying that they have met these requirements. The program includes twenty-seven possible levels of payment enhancement depending on available appropriations. Each level corresponds to an additional minute of licensed vocational nurse equivalent care above the statewide average per resident day and is associated with $0.33 per diem. These range from level 1 to level 27 enhancements of $0.34 to $8.92 per resident day, respectively, based on available appropriations. The state implemented a level 7 enhancement of $2.32 per day in fiscal year 2007.

Another prominent WPT effort was implemented in Florida (Hyer, Temple, and Johnson 2009). Adopted in 1999, the purpose was to stimulate providers to recruit and retain qualified nursing staff using an add-on to the patient care component of the Medicaid rate. Approximately $40 million was appropriated for the program, with 600 of Florida’s 648 Medicaid facilities electing to take part. Participating facilities received add-ons ranging from $0.50 to $2.81 and averaging $1.96 per day. The program was associated with additional facility spending of $107,152, on average, on salaries and benefits for direct-care workers between 1999 and 2000, as well as increased staffing hours, primarily among CNAs. It was not until the introduction of higher minimum staffing standards in 2002 did total staff hours per resident day change, however.

Because of a paucity of data, little is known as to whether WPT programs achieved their intended goals. Of twelve WPT states responding to a 1999 survey, four reported that they had a positive impact on recruitment and retention, three that they had no impact, and three that the impact was unknown (North Carolina Division of Facility Services 2000). Results from four unsophisticated evaluations have also been mixed: Michigan experienced a 61 percent increase in CNA wages and a 21 percent decline in turnover over the thirteen years of its WPT program; wages for nurse aides in Massachusetts increased by 8.7 percent during the first year of that state’s program and vacancy rates stabilized; after one year of implementation, turnover in Kansas nursing homes declined from 111 to 101 percent; total compensation for direct-care workers in Wyoming increased from $9.08 to $13.74 per hour, and turnover declined from 52 to 37 percent over the first three months of that state’s effort (Harris-Kojetin et al. 2004; Paraprofessional Healthcare Institute 2003).

Significance of Wage Pass-through Adoption

This research adds to the existing literature in several ways. Because states play such a prominent role in the U.S. health care system, they have long grappled with how to best control health care costs while maintaining high quality of care. There are many policy tools available to address efficiency and quality concerns — from pure state regulation to market-oriented competition designs. Given public discourse and official party platforms, one would assume states controlled by Democrats would be more likely to adopt regulatory reforms. This expectation is suggested by the extant literature, that ideologically more liberal states with Democratic public officials are more likely to favor government interventions and expenditures to improve quality and increase Medicaid spending than ideologically conservative states with Republican officials (Barrilleaux and Miller 1988; Erikson, Wright, and McIver 1993; Harrington, Mullan, and Carrillo 2004; Harrington, Carrillo, et al. 2000; Miller 2005). But is this always the case? Evidence from the federal level indicates that the relationship between partisanship and regulation in the health sector may not be so clear-cut. From 1971 to 1973, for example, the Nixon administration instituted wage and price controls to help curb inflation. Despite the rhetoric of diagnosis-related groups increasing competition, the Reagan administration championed the 1983 enactment of the Medicare Prospective Payment system to slow the rate of growth in hospital expenditures (Oberlander 2003). More recently, antistate, privatization approaches to health reform appear favorable to politicians across the political spectrum, including delegation of key activities to profit-making firms and individual consumers under the 2003 Medicare Prescription Drug, Improvement, and Modernization Act and the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (Morgan and Campbell 2011a, 2011b). The present study examines whether the more complex dynamic identified between partisanship, price regulation, and health reform at the federal level also plays out among the states.

Although several studies have examined the correlates of Medicaid nursing home reimbursement, most have done so with respect to overall levels of payment or provisions intended to improve cost efficiency, access to care, equity in provider payment, and service capacity (Miller 2006a, 2006b; Miller and Wang 2009a, 2009b; Swan, Harrington, and Pickard 2000; Swan et al. 1997, 2001). None have done so with respect to incentives built into state payment systems to improve quality. As far as we are aware, only one previous study (Harrington, Mullan, and Carrillo 2004) has used fifty-state statistical techniques to examine the correlates of state adoption of policies intended to improve the quality of nursing home care — in this case, the stringency of nursing home regulatory enforcement. It is widely believed that staffing is perhaps the most important determinant of quality. This and the lack of comparative state research with respect to quality make understanding the determinants of WPT adoption, the primary means for states to incentivize staffing increases through Medicaid nursing home reimbursement, of inherent interest.

Quality and staffing concerns are typically cited as the primary reasons for WPT adoption (Hyer, Temple, and Johnson 2009; North Carolina Division of Facility Services 2000; Paraprofessional Healthcare Institute 2003). Thus, despite limited evidence on the efficacy of WPTs, particularly during the time period studied, state officials nonetheless elected to pursue these programs in an effort to address these important issues. There are several reasons why this might have been the case. On their face, WPTs make sense: providing an increase in reimbursement and requiring that increase to go to staffing should be associated with an increase in staffing. While implementation challenges may have hampered efficacy in practice, the presence of a “plausible and sensible model of how [the] program [was] supposed to work” may have increased stakeholder confidence in the effectiveness of WPTs beyond the paucity of evidence available (Weiss 1998: 55). State officials may also have adopted WPT programs for reasons independent of program efficacy. Many policy makers want to address intractable policy problems even if clear evidence about the effectiveness of available interventions has yet to be generated. Although rational incentives favor adopting potentially efficacious policy options, cognitive and normative imperatives that influence whether a policy is perceived to be legitimate and appropriate can spur states to adopt policies independent of program efficacy (Miller and Banaszak-Holl 2005; DiMaggio and Powell 1991; Walker 1969). Thus state officials may have adopted WPT programs, amid uncertainty about their effectiveness, both because the program theory led officials to believe that WPT programs should work and because they perceived WPTs to be a legitimate and appropriate strategy for improving nursing home quality. Modeling WPT adoption provides us with the opportunity to identify the determinants of state policy action in an area where considerations beyond program efficacy may have been paramount.

Comparative state policy researchers typically model the adoption of policies that show substantial stability, that when adopted, tend to persist over time (Berry and Berry 2007). In the Medicaid nursing home reimbursement area, this includes case-mix adjustment, fair rental reimbursement, and provider taxes (Miller 2006b; Miller and Wang 2009a, 2009b). It is clear from the distribution of WPT adoption in our data set that most states, most of the time, decide annually whether to implement or keep these programs. As such, states could (and did) adopt and unadopt WPT programs annually. That this is indeed the case is supported by the observations of key actors in this process. This is reflected in the observations of the American Health Care Association and National Center for Associated Living (2008) — the major organization advocating on behalf of for-profit nursing homes — which highlights the fiscal-year nature of policy change in this area. It is also reflected in a statement by the Paraprofessional Healthcare Institute (2003: 3–4), which ties WPT adoption to the state budget: “Since both provider rates and pass-through amounts are set within the context of the state budget process, provider payments — and thus, indirectly, wages to workers — are dependent on overall budget availability and on the political choices governors and state legislators must make between competing spending priorities within that budget.” Part of what makes WPTs interesting, therefore, is their lack of stability, with states adopting and abandoning WPT programs in quick succession and potentially adopting and abandoning them once again in future years.

Recently, two systematic empirical investigations have been reported. Feng et al. (2010) assess the impact of Medicaid WPT policies on direct-care staffing in U.S. nursing homes across all forty-eight continental states. Results indicate that states introducing WPTs experienced net 3 to 4 percent increases in CNA hours per resident day in the years after adoption. Baughman and Smith (2007) assess the impact of Medicaid WPT policies on direct-care wages. Results indicate that direct-care workers in states with WPTs earn, on average, 7 percent more per hour than workers in states without these programs. Though promising, these studies assume that WPTs are exogenous rather than endogenous events, driven partly by a state’s underlying political, economic, and programmatic circumstances. Unless factors that lead to policy shifts are accounted for, estimates of policy impact in studies such as these may be biased (Besley and Case 2000). This lends further importance to delineating what factors, if any, promote or impede adoption in this area.

Hypothesis

Medicaid is the largest fiscal item in state budgets, accounting for 20.7 percent of total state spending in 2008 (National Association of State Budget Officers 2009). Long-term care is particularly salient, as it constitutes one-third of total Medicaid expenditures, with 70 percent being directed to institutional care for the aged and disabled (Burwell, Sredl, and Eiken 2009). Indeed, Medicaid is the major purchaser of nursing home care, accounting for 40.6 percent of total spending in 2008 (CMS 2010). Furthermore, nearly all nursing home beds are Medicaid certified, while two-thirds of residents rely on Medicaid to pay for their care (Jones et al. 2009; U.S. General Accounting Office [GAO] 2003).

Because of the large amount of money spent, Medicaid nursing facility reimbursement is highly salient politically and economically, both for state bureaucrats delegated primary responsibility for designing new payment methodologies and for legislators, governors, nursing homes, residents, and others who closely watch how program dollars are spent. The way Medicaid pays for direct-care staff is especially significant. This is both because staffing represents the largest component of most states’ rates and because most constituency groups — public officials, providers, consumer advocates — rank the direct-care “workforce” among the top three challenges facing long-term care (Miller, Mor, and Clark 2010).

Conversations with key constituents suggest that changes made to the way nursing homes are paid usually involve a number of actors, with initial policy development taking place through formal task forces or informal meeting groups managed by the state Medicaid agency.1 Key participants typically include state Medicaid officials and nursing home industry representatives and their respective consultants. Key participants also include staff from the governor’s office and legislature, not to mention resident advocates and, occasionally, other interested parties (e.g., state survey and certification staff, union representatives). While state agencies sometimes have the power to implement the policy changes devised, legislative approval is typically required before they go into effect.

Foremost among nursing home industry concerns is a desire to increase reimbursement while retaining maximal levels of autonomy in deciding how that money is spent (Miller 2008; Miller, Mor, and Clark 2010). Foremost among elder advocacy concerns is improving access and quality of care, primarily through regulatory changes but also through incentives built into provider payment systems (Long-Term Care Community Coalition 2004; Miller, Mor, and Clark 2010). Because adoption of WPT programs is closely tied to fiscal-year funding and the state budget process, state officials must carefully balance their ideological and partisan predispositions to achieving certain goals or helping certain groups with the realities of prevailing programmatic and fiscal circumstances and the capacity of government “to formulate coherent, creative and plausible policy and carry it out efficiently, effectively, and accountably” (Thompson 1998: 260). The external environment matters as well. Internal state processes are embedded in broader, contextual conditions deriving from other states’ actions and changes in federal law and regulation. The Medicaid nursing home arena is characterized by picket-fence federalism (Miller and Banaszak-Holl 2005). Federal statutes and regulations influence nursing homes, both directly, say, through public reporting (Nursing Home Compare) or the way Medicare pays for skilled nursing facility care, and indirectly, by establishing the broad parameters within which state Medicaid programs operate. Public, for-profit, and not-for-profit actors at both the state and national levels influence state policy making in this area also.

In light of the aforementioned discussion, we propose that state decisions to adopt a WPT program in a given year to be a function of a broad array of factors. Potential explanations are organized according to whether they (1) derive from the external context within which WPT adoption decisions takes place; (2) represent the interests and capacities of key participants involved in the process; and (3) characterize the fiscal and programmatic inputs that inform state decision making in this area.

External Context

Federal policy change, especially the Balanced Budget Act (BBA) of 1997, may have influenced adoption. In addition to repealing the federal Boren Amendment, which granted states more discretion over Medicaid nursing home reimbursement (Miller 2008), the BBA restructured Medicare payments to health care providers, including skilled nursing facilities (SNFs). SNFs had traditionally been paid under a reasonable cost-based, retrospective system. However, beginning with the 1999 fiscal year, reimbursement shifted to a prospectively determined payment rate for a day of SNF care, adjusted for patient acuity and other factors using case-mix methods. The adoption of prospective payment had its intended effect, leading to a sudden, dramatic decline in Medicare expenditures on SNFs (Rivers and Tsai 2002). This contributed even further to more general pressure for nursing homes to keep costs down, including limiting staffing levels and the wages, benefits, and training opportunities available to direct-care workers. Konetzka et al. (2004) demonstrate that the BBA had a strong negative impact on the level of RN and LPN staffing; White (2005 – 2006) demonstrates that it had a strong negative impact on nonprofessional staffing levels as well (i.e., CNAs). Perhaps as a response to these changes, state and federal officials’ concerns about the quality of care provided in the nation’s nursing homes heightened (Office of the Inspector General 1999; GAO 1999). To help alleviate the adverse financial impact of the BBA while being responsive to growing concerns about staffing and quality, some states may have adopted WPT programs. Since nursing homes in some states rely on Medicare more than nursing homes in other states, we posit that the influence of the BBA on WPT adoption may have been greater in states with more Medicare-dependent nursing homes.

Other states’ policies toward WPTs may have mattered as well. Previous research suggests regional diffusion of public policies (Allen, Pettus, and Haider-Markel 2004; Berry and Berry 1990, 2007; Miller 2006a, 2006b). Because state officials are often uncertain about the potential impact of adopting particular policies, they may look to previously adopting states to make means-ends connections clearer (Walker 1969). They also may look to other states to find out what is considered the “right thing to do” or the “state of the art,” regardless of impact, perhaps a more likely scenario given limited information on the efficacy of WPT programs at the time (Miller and Banaszak-Holl 2005). Consistent with this discussion, we posit that states are more likely to adopt a WPT program if their neighbors have already done so.

Key Participants

State adoption of WPTs also may have been influenced by interest group activity on behalf of the elderly (Harrington, Mullan, and Carrillo 2004; Miller 2006b). Resident advocates prefer that providers be held accountable for how increases in reimbursement are used, say, for example, making payment growth contingent on nursing home compliance with federal quality standards (Edelman 1997). Conversations with key constituents, however, suggest that advocates are not equally active in all states. Thus, while advocates tend to play less of a role in reimbursement policy discussions than other groups, in some states such as New York, Minnesota, Oregon, and California they are especially active, supporting the adoption of policy changes advantageous from the consumer point of view. Since shortages in the long-term-care workforce adversely affect staffing and, in turn, quality, we expect states with more powerful elderly advocacy lobbies to be more likely to adopt a WPT program.

Being heavily dependent on Medicaid for revenue, nursing homes also are extremely active in trying to influence policy in this area. Prior research indicates that nursing home industry activity is associated with Medicaid policies affecting nursing home spending, eligibility, enforcement, and reimbursement (Barrilleaux and Miller 1988; Grogan 1999; Harrington, Mullan, and Carrillo 2004; Miller 2006a, 2006b; Miller and Wang 2009b). While the industry would prefer to maintain high levels of Medicaid payment, it generally does not favor WPTs as a mechanism for doing so. There are several reasons, foremost among which include the administrative burdens typically imposed and the desire to maintain predictable revenue levels, not to mention the freedom to allocate revenue as the industry sees fit. This position is reflected in congressional testimony by the American Health Care Association and National Center for Assisted Living (2008: 7): “A Medicaid [WPT] for direct care staff wages is not the answer to [the staffing] problem… . [WPTs] are tied to fiscal year funding, and are therefore temporary. Without a federal mandate for ongoing stable funding of staffing costs, our workforce is vulnerable to the whims of each state budget process… . there [also] are numerous issues with implementing and overseeing these programs.” In light of industry concerns, we posit that states with more powerful nursing home lobbies are less likely to adopt.

Although the nursing home industry generally opposes WPT adoption, this may be particularly true among for-profit facilities. For-profits allocate resources differently from nonprofits. By law, nonprofit facilities must invest profits in pursuit of the organization’s mission. For-profit facilities have no such requirement and, in addition to providing a rate of return to investors, must pay taxes while typically compensating executives more generously (Comondore et al. 2009). Because “staff is the largest element of costs for most homes,” O’Neill et al. (2003: 1320) observe, “one mechanism for increasing profit [and paying for these expenses is] to decrease costs by decreasing staff time or wages.” This is likely the major reason why for-profits staff at substantially lower levels and offer lower wages and benefits than nonprofits. Given pressure to allocate resources elsewhere, it is likely that for-profits are more adversely affected by WPT adoption than nonprofits. Because they typically serve higher proportions of Medicaid residents, proprietary facilities are also more likely to be subject to states’ WPT provisions, further incentivizing opposition (Jones et al. 2009; O’Neill et al. 2003). Consistent with this discussion, we posit that states with higher for-profit penetration will be less likely to adopt a WPT program.

The political party affiliation of the governor may also influence the likelihood of adoption. As reported earlier, prior studies suggest that ideologically more liberal states with Democratic public officials are more likely to favor government interventions and expenditures to improve quality and increase Medicaid spending (Barrilleaux and Miller 1988; Erikson, Wright, and McIver 1993; Harrington, Mullan, and Carrillo 2004; Harrington, Carrillo, et al. 2000; Miller 2005). Since WPT programs typically operate partly through increases in reimbursement, we expect states with Democratic governors to be more likely to adopt such programs. Because Democratic officials tend to be less sympathetic to nursing home industry interests than Republican officials (Miller 2006b; Mor, Miller, and Clark 2010), and because for-profit facilities are posited to be most vehement in their opposition to WPT programs while exhibiting the poorest quality of care, on average, we also expect the likelihood of WPT adoption to increase with for-profit representation under Democratic governors and to decrease with for-profit representation under Republicans.

Previous studies indicate a positive association between governing capacity and state policy innovation in a broad range of areas, including changes in Medicaid nursing home payment methodologies (Berry and Berry 1990, 2007; Miller 2005, 2006b; Miller and Wang 2009a). States with greater governing capacity may be able to develop and implement WPTs while overcoming impediments that might otherwise augur against them — for example, instituting the requisite auditing and enforcement procedures that ensure that payment increases indeed show up as higher wages and more generous benefits. Three indicators of governing capacity are considered: governors with greater statutory and constitutional authority (Beyle and Ferguson 2008; Miller 2006b); legislative bodies with higher salaries, greater resources, and longer sessions (Berry, Berkman, and Schneiderman 2000; Huber, Shipan, and Pfahler 2001; Miller 2006b; Miller and Wang 2009a); and agencies with greater financial, intellectual, and other resources (Barrilleaux and Miller 1988; Schneider and Jacoby 1996; Miller 2006b; Miller and Wang 2009a). We expect states with greater capacity to be more likely to adopt a WPT program than states with less capacity in each of these areas.

Fiscal and Programmatic Inputs

The likelihood of WPT adoption may be influenced by programmatic factors as well. States pass WPT programs with the aim of increasing staffing and thereby quality. This suggests that states with higher existing staffing levels may be less inclined to adopt such measures than states with lower levels. Since professional staffing is most closely associated with more favorable resident outcomes (Decker 2006; Harrington, Zimmerman, et al. 2000; Horn et al. 2010), this may be especially true where RN and LPN staffing is concerned. By contrast, states with more Medicaid-dependent nursing homes may be more inclined to consider a WPT because of greater concern among state officials about how Medicaid dollars are spent, not to mention greater leverage with which to influence provider behavior. This also may be true of states with more generous standards for qualifying for Medicaid nursing home coverage. Indeed, more generous states may experience greater pressure not only to control spending, as prior research demonstrates (Harrington, Carrillo, et al. 2000; Miller 2005, 2006b), but also to pursue WPT and other initiatives that better enable nursing homes to provide quality care to Medicaid recipients.

States with higher reimbursement rates may be more likely to adopt as well. States vary substantially in how much they pay nursing homes, with, for example, the average per diem rate in 2004 ranging from less than $100 in five states to over $165 in six (Grabowski et al. 2008). States with higher average per diem payments have more room with which to carve out and devote at least a portion of their rate or its increase to direct-care workers. In addition, home care availability may increase the likelihood of adoption. Growth in the home-and community-based services (HCBS) sector has markedly increased the demand for workers. Indeed, among the fastest-growing occupations are home health aides and personal/home care aides (BLS 2010). Expansion of HCBS has exacerbated challenges that nursing homes face in recruiting and retaining their own staff. This may have helped spur some states to adopt WPT programs to better enable nursing homes to compete for the limited pool of workers available, an incentive that would have been greater in states with higher concentrations of HCBS.

Finally, state economic and fiscal circumstances may have affected adoption. Not only do fiscal crises make it more difficult for states to innovate (Berry and Berry 1990, 2007), but they make it more difficult for states to fund Medicaid at existing levels and thus less likely to adopt a WPT program. There also may be less need for states to implement a pass-through as adverse fiscal circumstances increase unemployment, thereby making it easier for nursing homes to recruit and retain direct-care staff. Thus, for example, the tight labor market in the late 1990s exacerbated the labor shortage in long-term care, while the recession years of the early 2000s eased it somewhat given fewer alternative employment options available. Consistent with this discussion, we expect states in weaker fiscal health to be less likely to adopt a WPT. Furthermore, since states with greater fiscal capacities have broader tax bases with which to innovate and to support higher levels of reimbursement, we expect them to be more likely to adopt a WPT as well.

Methods

This study models state adoption of a WPT program in a given year. A random effects panel data design was used to identify the determinants of adoption. This approach was appropriate in light of the lack of stability in the adoption decision. Both the data and other evidence (noted earlier) suggest that states determine whether to adopt or unadopt these programs annually. The state year is the unit of analysis. Arizona is excluded because of missing data and its unique Medicaid system. Hawaii and Alaska also are excluded because of missing data. They also do not share borders with other states.

Dependent Variable

The dependent variable, state WPT adoption, is a dichotomous variable coded as 1 if a state adopted a WPT in a given year and 0 otherwise. Data on WPT adoption derive from periodic telephone interviews and mail surveys of state Medicaid officials (Grabowski et al. 2008).

Independent Variables

Implementation of the BBA is measured using the average percentage of certified nursing facility residents paid for by Medicare. Data derive from Harrington, Carrillo, and LaCava 2006.

Neighboring state adoptions are measured using the proportion of contiguous states adopting a WPT program, lagged one year. Data derive from Grabowski et al. 2008.

Elder advocacy power and nursing home industry power are conceptualized as being a function of interest group strength and size (Grogan 1999; Miller 2006b). Strength derives from the Hrebenar-Thomas study, in which experts in state politics categorized interest groups in each of the fifty states into one of two categories: those among the most consistently effective, and those rising or declining in power, regularly active but not among the most effective, or occasionally active (Nownes, Thomas, and Hrebenar 2008). Based on these rankings, senior citizen and nursing home strength were coded 2 if they appeared in the first category of the Hrebenar and Thomas list, 1 if they appeared in the second category, and 0 if they did not appear at all. These measures of strength were then interacted with proxies for interest group size — percentage population sixty-five years and older and nursing home beds per one thousand sixty-five and older, respectively — to generate the measures of elder advocacy and nursing home industry power used. Data derive from Hrebenar and Thomas 1998 – 2007, the U.S. Census Bureau 2007, and the American Health Care Association 2007.

For-profit nursing home penetration is measured using the percentage of nursing facilities with for-profit ownership. Data derive from Harrington, Carrillo, and LaCava 2006.

Governor’s party is a dichotomous variable coded as 1 if the state’s governor is a Democrat and 0 otherwise.2 Data derive from Lindquist 2007.

Gubernatorial power is an index obtained from factor analysis of indicators developed by Beyle and Ferguson (2008), including appointment power, budgetary power, and separately elected officials. Data derive from the Council of State Governments 2000 – 2005.

Legislative professionalism is measured using an index based on factor analysis of the natural log of calendar days and per member staff, as well as operating expenditures and compensation, converted to 2004 dollars using the Consumer Price Index (CPI) (Miller 2006b). Data derive from the Council of State Governments 2000 – 2005, National Conference of State Legislatures 2000 – 2004, 2002 – 2006, 2004, and the U.S. Census Bureau 2000 – 2004b, 2007.3

Administrative capacity is measured using the number of FTE public welfare employees per one thousand population. Data derive from the Annual Survey of Governments undertaken by the U.S. Census Bureau 2000 – 2004a.

Nursing home staffing is measured using the average number of licensed nursing hours per resident day in certified nursing facilities, lagged one year. Data derive from Harrington, Carrillo, and LaCava 2006. All fiscal and programmatic variables are lagged one year under the assumption that state officials typically formulate current policy based partly on the prior year’s circumstances.

Nursing home Medicaid dependence is measured using the average percentage of residents paid for by Medicaid, lagged one year. Data derive from Harrington, Carrillo, and LaCava 2006.

Medicaid program eligibility is coded as 1 if a state had a medically needy program for Supplemental Security Income recipients and 0 otherwise, lagged one year. Data derive from the Social Security Administration 2000 – 2004.

Nursing home reimbursement is measured using the average Medicaid per diem rate, lagged one year and adjusted to 2004 dollars using the CPI. Data derive from Grabowski et al. 2008.

Home care availability is measured using the number of certified Medicare home health care agencies per one hundred thousand population, lagged one year. Data derive from CMS 2000 – 2004 and the U.S. Census Bureau 2007.

Fiscal health is measured using the unemployment rate, lagged one year. Data derive from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics 2007. A budget-based measure of fiscal health is also used: percentage budgetary surplus. This is defined as [(total state revenue – total state spending)/total spending]*100, lagged one year (Berry and Berry 1990). Data derive from the Annual Survey of Government Finances undertaken by the U.S. Census Bureau 2000 – 2004b.

Fiscal capacity is measured using the natural log of per capita gross state product, lagged one year and adjusted to 2004 dollars using the CPI. Data derive from the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis 2007.

Analysis

Random effects panel models were employed in this study. Analyses were estimated using PROC GLIMMIX in SAS 9.2, which allows users to model random variation in longitudinal data, including random effects (between-state variation) and serial correlation (within-state variation). A random intercept was incorporated into our models to account for between-state variation and the potential for omitted variable bias. Yearly fixed effects and robust standard errors, which account for the clustering of observations within states (Diggle, Liang, and Zeger 1994), were used to address the potential for serial correlation. Given that one year of data is lost when prior neighboring state adoption is included, two models were estimated: one with this variable, one without.

The model with prior neighboring state adoption included 235 observations across forty-seven states from 2000 to 2004. In all, fifty-seven cases, or 24 percent, were scored adoption during this time period. The model excluding prior neighboring state adoption included 282 observations across forty-seven states from 1999 to 2004. In all, sixty-three cases, or 22 percent, were scored adoption during this time period. The log odds or β estimates are converted to odds ratios (eβ) to facilitate interpretation.4 We also report predicted probabilities for our significant findings using the model with neighboring state adoption (t – 1) when year = 2004, medically needy program = 1, and all other variables are held constant at their means.5 These results are stratified by the governor’s political party affiliation.

We explore whether Democratic governors are less responsive to for-profit nursing facilities than Republican governors by reestimating our models with the addition of a term for Democratic governor*percentage for-profit nursing facility interaction. Here the coefficient on percentage for-profit facilities indicates the relationship between percentage for-profit and WPT adoption under Republican governors. The relationship between percentage for-profit and WPT adoption under Democratic governors is determined by multiplying the odds ratio on percentage for-profit by the odds ratio on the term for Democratic governor*percentage for-profit interaction. Our interaction findings are also examined graphically using the model with neighboring state adoption (t – 1), by medically needy program (t – 1) and year, with all other variables held constant at their means.6

Table 1 summarizes our hypotheses in light of the measurement strategies outlined. Table 2 reports descriptive statistics for all variables across the entire study period. None of the explanatory variables were highly correlated (all |r|< .60), and tolerance tests showed no problematic multicollinearity.

Table 1.

Measurement and Expected Signs on Coefficients for Explanatory Variables

| Variables | Measurement | Sign |

|---|---|---|

| Balanced Budget Act implementation | Average percentage of nursing home residents paid for by Medicare | + |

| Neighboring state adoptions | Percentage of contiguous states adopting a wage pass-through program (t – 1) | + |

| Elder advocacy power | Senior lobby strength*percentage 65+ | + |

| Nursing home industry power | Industry lobby strength*beds per 1,000 65+ | − |

| For-profit nursing home penetration | Percentage of nursing facilities with for-profit ownership | − |

| Democratic governor | 1 = Democratic governor; 0 = otherwise | + |

| Gubernatorial power | Gubernatorial power index | + |

| Legislative professionalism | Legislative professionalism index | + |

| Administrative capacity | FTE public welfare employees per 1,000 population | + |

| Nursing home staffing | Average licensed nurse hours per resident day in certified nursing facilities (t – 1) | − |

| Nursing home Medicaid dependence | Average percentage of nursing home residents paid for by Medicaid (t – 1) | + |

| Medicaid program eligibility | Medically needy program (t – 1) | + |

| Nursing home reimbursement | Average Medicaid per diem rate (t – 1) | + |

| Home care availability | Home health agencies per 100,000 (t – 1) | + |

| Fiscal health | [(total revenue – total spending)/total spending]*100 (t – 1) | + |

| Fiscal health | Unemployment rate (t – 1) | − |

| Fiscal capacity | Per capita gross state product (t – 1) (logged) | + |

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Study Variables, 1999–2004 (N = 282)

| Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balanced Budget Act implementation | 10.213 | 2.941 | 3.900 | 18.200 |

| Percent contiguous states w/pass-through (t – 1)a | 17.482 | 20.578 | .000 | 100.000 |

| Elder advocacy power (strength*size) | 3.631 | 6.594 | .000 | 29.807 |

| Nursing home industry power (strength*size) | 29.726 | 47.671 | .000 | 167.519 |

| Percentage nursing facilities for-profit | 62.593 | 15.545 | 7.300 | 86.100 |

| Democratic governor | .394 | .489 | .000 | 1.000 |

| Gubernatorial power index | 6.876 | 1.402 | 3.477 | 9.374 |

| Legislative professionalism index | 22.945 | 2.692 | 15.103 | 29.017 |

| FTE public welfare employees/1,000 | 1.075 | .499 | .043 | 2.199 |

| Average licensed nurse hours/resident day (t – 1) | 1.420 | .212 | 1.000 | 2.300 |

| Average percentage Medicaid residents (t – 1) | 65.968 | 6.867 | 49.200 | 82.100 |

| Medically needy program (t – 1) | .702 | .458 | .000 | 1.000 |

| Average per diem Medicaid rate (t – 1) | 117.288 | 23.350 | 71.817 | 189.822 |

| Home health agencies/100,000 (t – 1) | 3.518 | 2.094 | .590 | 12.920 |

| [(Total revenue – spending)/spending]*100 (t – 1) | 6.107 | 15.530 | −27.977 | 124.883 |

| Unemployment rate (t – 1) | 4.552 | 1.137 | 2.300 | 8.100 |

| Per capita gross state product (t – 1) (logged) | 10.486 | .173 | 10.107 | 11.057 |

| Senior citizen influence (strength) | .280 | .495 | .000 | 2.000 |

| Nursing home influence (strength) | .553 | .843 | .000 | 2.000 |

| Percentage population 65+ (size) | 54.113 | 16.038 | 19.475 | 100.173 |

| Beds per 1,000 65+ (size) | 12.669 | 1.618 | 8.569 | 18.145 |

The neighboring state adoption variable has 235 observations from 2000 through 2004.

Results

Models predicting WPT adoption with prior neighboring state adoption (2000 – 2004) and without prior neighboring state adoption (1999 – 2004) are reported in table 3. significant findings were mostly consistent across both models estimated. As expected, states with more professional legislatures (b1 = .450, b2 = .475, both p < .01) and capable public welfare bureaucracies (b1 = 2.633, p1 < .001; b2 = 2.131, p2 < .01) were more likely to adopt a WPT program, which supports the expectation that both the legislature and state Medicaid agency would be key participants in this area and that stronger governing capacity would facilitate adoption. Thus, for each additional FTE public welfare employee per one thousand, states were more than eight to thirteen times more likely to adopt a WPT program in a given year (Odds Ratio1 [OR1] = 13.915, OR2 = 8.423). In addition, results indicate that states with higher percentages of nursing home residents paid for by Medicaid were more likely to adopt (b1 = .088, p1 < .10), suggesting a 9.2 percent increase in the likelihood of adoption for each percentage point increase in the proportion of Medicaid residents served (OR1 = 1.092). This is consistent with the expectation that adoption would be more likely in states with greater concern about how Medicaid dollars were spent and greater leverage with which to influence workforce practices. The same is true for percentage budgetary surplus, which, in proving positively related to adoption (b1 = .028, p1 < .05; b2 = .037, p2 < .01), was consistent with the expectation that financially healthier states would be more likely to do so. The probability of adoption also increased with the proportion of previously adopting neighboring states (b1 = .026, p < .05). Thus, whereas each percentage point increase in excess revenue is associated with a 2.8 to 3.8 percent increase in the likelihood of WPT adoption (OR1 = 1.028, OR2 = 1.038), each percentage point increase in the proportion of previously adopting neighbors is associated with a 2.6 percent increase (OR1 = 1.026).

Table 3.

Models of Wage Pass-through Adoption, with and without Neighboring State Adoption (t – 1) (2000–2004, 1999–2004)

| With Neighboring State (2000–2004) |

Without Neighboring State (1999–2004) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | Beta (SE) |

Odds Ratio |

Beta (SE) |

Odds Ratio |

| Balanced Budget Act implementation | −.041 (.167) | .960 | −.058 (.142) | 0.944 |

| Neighboring state adoption (t – 1) | .026** (.014) | 1.026 | — | — |

| Elder advocacy power (strength*size) | .039 (.501) | 1.040 | −.079 (.339) | .924 |

| Industry power (strength*size) | −.086*** (.033) | .918 | −.072*** (.028) | .931 |

| Percentage nursing facilities for-profit | −.049** (.025) | .952 | −.051*** (.022) | .950 |

| Governor’s party Democratic | −.758 (.546) | .469 | −.782 (.530) | .457 |

| Gubernatorial power | −.249 (.333) | .780 | −.138 (.307) | .871 |

| Legislative professionalism | .450*** (.176) | 1.568 | .475*** (.193) | 1.608 |

| Administrative capacity | 2.633**** (.798) | 13.915 | 2.131*** (.785) | 8.423 |

| Avg. licensed nursing hours/day (t – 1) | −2.297 (1.910) | .101 | −1.731 (1.660) | .177 |

| Avg. percentage Medicaid residents (t – 1) | .088* (.066) | 1.092 | .071 (.057) | 1.074 |

| Medically needy program (t – 1) | −.462 (.962) | .630 | −.510 (.940) | .600 |

| Average per diem Medicaid rate (t – 1) | .025 (.021) | 1.025 | .013 (.021) | 1.013 |

| Home health agencies/100,000 (t – 1) | .295 (.236) | 1.343 | .012 (.162) | 1.012 |

| Percentage budgetary surplus (t – 1) | .028** (.015) | 1.028 | .037*** (.015) | 1.038 |

| Unemployment rate (t – 1) | −.717* (.490) | .488 | −.896** (.500) | .408 |

| Per capita gross state product (t – 1) (log) | −2.092 (2.866) | .123 | −2.533 (2.881) | .079 |

| Senior citizen influence (strength) | .570 (6.727) | 1.768 | 2.028 (4.576) | 7.599 |

| Nursing home influence (strength) | 4.644*** (1.741) | 103.959 | 3.832** (1.514) | 46.155 |

| Percentage population 65+ (size) | −.442** (.237) | .643 | −.386* (.221) | 0.680 |

| Beds per 1,000 65+ (size) | −.021 (.036) | 0.979 | −.010 (.033) | 0.990 |

| Year 2000 | — | — | 1.097** (.520) | 2.995 |

| Year 2001 | −.777 (.497) | .460 | .343 (.742) | 1.409 |

| Year 2002 | .579 (.845) | 1.784 | 2.022** (.814) | 7.553 |

| Year 2003 | .895 (1.267) | 2.447 | 2.952** (1.165) | 19.144 |

| Year 2004 | .776 (1.312) | 2.173 | 2.724** (1.217) | 15.241 |

| Constant | 14.922 (30.757) | 20.391 (20.889) | ||

|

N = 235, 47 states Cases scored adopt: 24% −2 log pseudo likelihood: 1247.61 |

N = 282, 47 states Cases scored adopt: 22% −2 log pseudo likelihood: 1507.14 |

|||

Notes: Cell entries are pseudo maximum likelihood estimated slopes with odds ratios to the right and robust standard errors below. Alaska, Hawaii, and Arizona were excluded from all analyses because of missing data. SE = standard error

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

(All significance tests are one-tailed except for those of the intercept, yearly indicators, and four strength/size variables used to calculate senior advocacy and nursing home power.)

By contrast, WPT adoption was negatively associated with both the proportion of for-profit nursing homes (b1 = −.049, p1 < .05; b2 = −.051, p2 < .01) and nursing home industry power (b1 = −.086, p1 < .01; b2 = −.072, p2 < .01). Together these findings support the expectation that nursing homes would oppose state policy action in this area, with a percentage point increase in for-profit representation, for example, being associated with a 5 percent decrease in the likelihood of adoption (OR1 = 0.952, OR2 = 0.950). Adoption also was less likely to occur in states with higher unemployment rates (b1 = −.717, p1 < .10; b2 = −.896, p2 < .05), thereby further supporting the proposition that states would refrain from adopting WPT programs under adverse fiscal circumstances. Results suggest a 50 to 60 percent reduction in the probability of adoption for each percentage point increase in the unemployment rate (OR1 = 0.488, OR2 = 0.408).

Predicted probabilities are reported in table 4. No matter the indicator, the predicted probability of WPT adoption tends to be lower under Democratic than Republican governors. No matter who is in charge of the statehouse, however, a high value on industry power, percentage for-profit, and unemployment results in substantially lower probabilities of adoption than lower values. In states with Democratic governors, for example, the probability of WPT adoption decreases from .64 to .09 to .04 when percentage for-profit increases from its minimum (7.3 percent) to median (66.7 percent) and maximum (86.1 percent) values, respectively. In states with Republican governors, the probability of adoption declines from .79 to .17 and .07 across these same values. When unemployment increases from its minimum (2.3 percent) to maximum (8.1 percent) values, the predicted probability of adoption declines by .37 in Democratic states and .55 in Republican states.

Table 4.

Estimated Probability of Wage Pass-through (WPT) Adoption for Significant Predictors at Select Values, Democratic Governor versus Republican/Other Governora

| Variables | Probability of WPT Adoption |

Variables | Probability of WPT Adoption |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Industry Power | Governorb (D) |

Governor (R/O) |

Percent for-Profit Nursing Facility | Governor (D) |

Governor (R/O) |

||

| Minimum | 0 | .59 | .76 | Minimum | 7.30 | .64 | .79 |

| 1st Quartile | 0 | .59 | .76 | 1st Quartile | 52.00 | .17 | .30 |

| Median | 0 | .59 | .76 | Median | 66.70 | .09 | .17 |

| 3rd Quartile | 68.59 | 0 | .01 | 3rd Quartile | 74.00 | .06 | .13 |

| Maximum | 161.63 | 0 | 0 | Maximum | 86.10 | .04 | .07 |

| Percent Medicaid (t – 1) | Governor (D) |

Governor (R/O) |

Neighboring State Adoption (t – 1) | Governor (D) |

Governor (R/O) |

||

| Minimum | 49.20 | .03 | .05 | Minimum | 0 | .07 | .14 |

| 1st Quartile | 61.30 | .07 | .14 | 1st Quartile | 0 | .07 | .14 |

| Median | 65.60 | .10 | .20 | Median | 16.67 | .10 | .20 |

| 3rd Quartile | 71.10 | .16 | .28 | 3rd Quartile | 25.00 | .13 | .23 |

| Maximum | 82.10 | .33 | .51 | Maximum | 100.00 | .50 | .68 |

| Legislative Professionalism | Governor (D) |

Governor (R/O) |

FTE Public Welfare Employees/1,000 | Governor (D) |

Governor (R/O) |

||

| Minimum | 15.10 | .00 | .01 | Minimum | 0.04 | .01 | .02 |

| 1st Quartile | 21.57 | .06 | .12 | 1st Quartile | 0.78 | .05 | .10 |

| Median | 23.19 | .12 | .22 | Median | 1.07 | .10 | .20 |

| 3rd Quartile | 24.35 | .18 | .32 | 3rd Quartile | 1.42 | .23 | .39 |

| Maximum | 29.02 | .64 | .79 | Maximum | 2.20 | .69 | .83 |

| Percent Budgetary Surplus (t – 1) | Governor (D) |

Governor (R/O) |

Unemployment Rate (t – 1) | Governor (D) |

Governor (R/O) |

||

| Minimum | −27.98 | .05 | .09 | Minimum | 2.30 | .38 | .57 |

| 1st Quartile | −7.51 | .08 | .16 | 1st Quartile | 3.70 | .18 | .33 |

| Median | 3.51 | .10 | .20 | Median | 4.50 | .11 | .21 |

| 3rd Quartile | 13.92 | .13 | .25 | 3rd Quartile | 5.40 | .06 | .12 |

| Maximum | 124.88 | .77 | .88 | Maximum | 8.10 | .01 | .02 |

This table presents the predicted probabilities for the significant variables using the model with neighboring state adoption (t – 1) (table 3) when year = 2004, medically needy program = 1, and all other variables are held constant at their means.

D = Democratic; R/O = Republican/Other

Alternatively, high values on legislative professionalism, percentage Medicaid, public welfare employees, percentage budgetary surplus, and previously adopting neighbors are associated with markedly higher probabilities of adoption than low values. In states with Democratic governors, for example, the probability of WPT adoption rises from .03 to .10 to .33 when percentage Medicaid increases from its minimum (49.2 percent) to median (65.6 percent) and maximum (82.1 percent) values, respectively. In states with Republican governors, the probability of adoption rises from .05 to .20 and .51 across these same values. When the number of FTE public welfare employees per one thousand increases from its minimum (.04) to median (1.07) value, the predicted probability of adoption rises by approximately .09 and .18 in Democratic and Republican states, respectively, with an additional increase in the probability of adoption of .59 and .63 given an additional increase to 2.20 FTEs, the maximum value recorded in the data set. When the proportion of neighboring states increases from its median (16.7 percent) to maximum (100 percent) values, the probability of adoption rises by .40 under Democratic governors and .48 under Republicans. When percentage budget surplus increases from its minimum (−27.98 percent) to median (3.51 percent) to maximum (124.88 percent) values, the probability of adoption rises from .05 to .10 and .77, respectively, under Democratic governors and .09 to .20 and .88, respectively, under Republicans.

The interaction models are reported in table 5. Each model reveals a significant negative relationship between percentage for-profit nursing facilities and WPT adoption in states with Republican governors (b1 = −.060, p1 < .05; b2 = −.065, p2 < .01). This indicates that each percentage point increase in the proportion of for-profit facilities is associated with a 5.8 to 6.3 percent decrease in the likelihood of WPT adoption under Republican governors, all else being equal (OR1 = 0.937, OR2 = 0.942). Both models, however, display a positive sign on the Democratic governor*percentage for-profit interaction (b1 = .087, p1 < .05, OR1 = 1.099; b2 = .094, p2 < .05, OR2 = 1.091), thereby indicating that the inverse relationship between percentage for-profit facilities and WPT adoption otherwise seen with Republican governors may be dampened or eliminated when Democrats hold the governorship. Indeed, this appears to be the case as the odds of adoption increases by 3 percent for each percentage point increase in the proportion of for-profit facilities when Democratic governors are in control, all else being equal (model 1: 1.030 = .937*1.099; model 2: 1.028 = .942*1.091).

Table 5.

Models of Wage Pass-through Adoption with Democratic Governor*Percentage For-Profit Interaction, with and without Neighboring State Adoption (t – 1) (2000–2004, 1999–2004)a

| With Neighboring State (2000–2004) |

Without Neighboring State (1999–2004) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Independent Variables | Beta (SE) |

Odds Ratio |

Beta (SE) |

Odds Ratio |

| Percentage nursing facilities for-proft | −.060* (.027) | .937 | −.065** (.024) | .942 |

| Governor’s party Democrat | −6.424* (2.636) | .001 | −6.969* (2.854) | .002 |

| Governor’s party Democrat*percentage nursing facilities for-proft | .087* (.046) | 1.099 | .094* (.046) | 1.091 |

| Constant | 5.800 (31.451) | 11.594 (32.094) | ||

|

N = 235, 47 states Cases scored adopt: 24% −2 log pseudo likelihood: 1266.06 |

N = 282, 47 states Cases scored adopt: 22% −2 log pseudo likelihood: 1531.13 |

|||

Note: Cell entries are pseudo maximum likelihood estimated slopes with odds ratios to the right and robust standard errors below. Alaska, Hawaii, and Arizona were excluded from all analyses because of missing data.

Other variables include the BBA, neighboring state adoption (t – 1), elder advocacy power, industry power, gubernatorial power, legislative professionalism, administrative capacity, avg. licensed nursing hours/resident day (t – 1), avg. percentage Medicaid residents (t – 1), medically needy program (t – 1), avg. per diem Medicaid rate (t – 1), home health agencies/1,000 65+ (t – 1), state budget (t – 1), unemployment (t – 1), per capita gross state product (log) (t – 1), senior influence, nursing home influence, percent 65+, beds/1,000 65+, year indicators.

p < .05;

p < .01

(all significance tests are one-tailed)

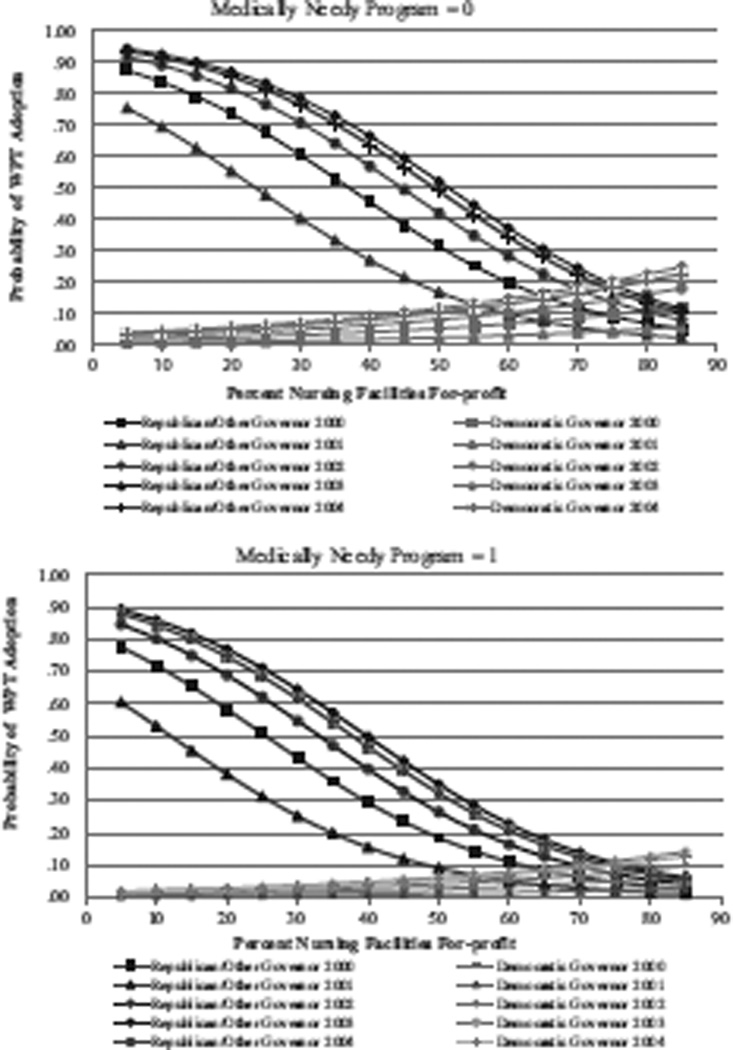

Figure 2 illustrates these relationships graphically. It shows that under Republican governors the probability of WPT adoption was relatively high when the proportion of for-profit facilities was low. As the proportion of for-profit facilities rose, however, the probability of adoption declined rapidly until it was quite low when the proportion of for-profits was at its maximum value. By contrast, under Democratic governors the probability of WPT adoption was nearly zero when the proportion of for-profit facilities was comparatively low. As the proportion of for-profit facilities rose, however, the probability of adoption increased, though not to the highest levels exhibited when Republicans were in control. Still, when the proportion of for-profit facilities was at its highest, it appears as if Democratic governors were slightly more likely to adopt a WPT program than Republican governors, though this difference does not appear to be substantively significant.

Figure 2.

The Moderating Effect of Governor’s Party on the Relationship between Percentage For-Proft Nursing Facility and the Probability of Wage Pass-through (WPT) Adoptiona

aThis figure presents the interaction of governor’s party affiliation with average percentage for-profit nursing facilities by medically needy program (t – 1) and year, with all other variables held constant at their means. Results derive from the model with neighboring state adoption (t – 1) (table 5). They are similar when the model without neighboring state adoption (t – 1) is used.

Discussion

This study modeled state adoption of a WPT program in a given year. Contrary to expectations, results from the predicted probability and interaction analysis findings indicate that states with Democratic governors may have been less likely to adopt WPT initiatives than states with Republican governors, thereby suggesting the presence of a more complex dynamic between partisanship and price regulation than typically assumed at the state level. That Republican states were more likely to adopt a WPT program than Democratic states may have to do with the types of quality improvement initiatives typically favored by members of the two major political parties. In general, the Democratic Party offers substantially stronger support for efforts to improve nursing home quality than the Republican Party. Furthermore, to the extent that they address the issue, Republicans typically favor incentive-based strategies, while Democrats lean toward approaches in the command-and-control mold. This difference in perspective is reflected in findings from a recent survey of long-term-care specialists where Democrats were nearly ten percentage points more likely than Republicans to believe that more aggressive enforcement and higher staffing standards would be effective or very effective strategies for ensuring and improving nursing home quality, and Republicans were more than fifteen percentage points more likely to believe that higher payments and pay for performance would be effective or very effective for doing so (Mor, Miller, and Clark 2010). Thus, while Democratic governors may have been more likely to support efforts to improve nursing home quality, their focus in doing so may have emphasized minimum staffing ratios and enhancements to the survey and certification process before incentives embedded in the way nursing homes were paid. This is in contrast to Republican governors who, in being much more likely to support industry interests as they relate to regulation and other matters, may have focused on WPTs and other potential enhancements to providers’ revenue streams, to the extent that they were moved to act on concerns about the quality of care delivered in nursing homes at all. However, as the lobbying strength of for-profit nursing homes grew, Republican officials may have been more likely to cater to industry preferences precluding adoption of any initiative limiting nursing homes’ autonomy to spend revenue as they saw fit. By contrast, Democratic officials may have become more likely to adopt as for-profit interests became more prevalent, possibly because of rising concerns about the level of staffing and quality of care provided by the average facility within their states.

Results also suggest that the predictors of WPT adoption represent a hybrid between incremental and nonincremental policy change in the Medicaid nursing home reimbursement arena. In making annual decisions to implement a WPT program, state officials reacted predictably to prevailing political and economic concerns affecting Medicaid and the state budget. WPTs tend to be small, incremental add-ons above the basic reimbursement rate. This is in contrast to, say, case-mix adjustment, which affects a much larger proportion of what nursing homes are paid. Since WPTs tend to be comparatively small, marginal changes to states’ reimbursement methodologies, state officials may have been sensitive to similar political, economic, and programmatic factors that influence other fiscal-year decisions. This is in contrast to case-mix reimbursement, which, in distributing a considerably larger slice of the reimbursement pie, tends to be adopted much more intermittently and therefore tends to be more independent of annual considerations such as these (Miller 2006b; Miller and Wang 2009a). Like case-mix and other nonincremental changes, however, WPT adoption also depended on states’ capacities to govern. This suggests a necessity for certain resource and expert levels when adopting WPT programs not typically required when making other, annual adjustments to state reimbursement systems, including such routinely considered matters as inflation factors, cost center limitations, and ancillary services inclusions.

Focusing on key participants results does not support the expectation that states with more powerful elder advocacy groups would be more likely to adopt a WPT. As such, it is consistent with analyses demonstrating significant associations between elderly advocacy strength and nursing home reimbursement levels but not the adoption of particular methodologies for adjusting payment for resident acuity and compensating nursing homes for capital expenditures (Miller 2006b; Miller and Wang 2009a). It further comports with the more general finding that elder advocates tend to be among the less influential organized interests across the states. This is reflected in the Hrebenar-Thomas study where hospital and nursing home associations, for example, were ranked the fifth most influential interest across the fifty states in 2007 behind business, teacher, utility, and manufacturer interests, and senior citizens/AARP the thirty-ninth most influential, next to last on the list, just ahead of pro-tobacco interests (Nownes, Thomas, and Hrebenar 2008). Together these findings suggest that elder advocates tend to be more concerned with issues related to overall payment, eligibility, benefits, and quality rather than the particular payment methodologies used.

Given the comparative lobbying strength of providers, it should not be surprising that states with more powerful nursing home lobbies were less likely to adopt a WPT program. This is the obverse of previous studies indicating that states with more powerful industry lobbies were more likely to adopt payment systems with more generous levels of reimbursement (Miller 2006b; Miller and Wang 2009b). Together these findings suggest that nursing home industry representatives can be effective in promoting/impeding reimbursement policy changes consistent/inconsistent with their interests. Conversations with industry representatives further reinforce the notion that nursing homes do not view WPT programs favorably. “They want to tell us how to spend it,” reported one representative. “And there’s no way you can do that. It just doesn’t work.” Said another: “We would agree that we need more salaries and benefits for our employees. We would not agree in the manner in which the money was delivered to facilities, mandating salary increases. The problem with a mandate is it is very prescriptive… . every nursing home needs to be run differently.”

That states with higher proportions of for-profit nursing homes were even less likely to adopt a WPT program than states with more powerful nursing home lobbies generally suggests that the extent to which one segment of the industry loses makes a difference where policy adoption is concerned. Previous research indicates that some segments of the industry support certain reimbursement policy changes that other segments oppose. One example is case-mix reimbursement that is favored by some facilities because they serve disproportionately higher numbers of heavy care residents and is opposed by others because they serve less burdensome ones (Miller 2008; Miller and Banaszak-Holl 2005). Another example is the imposition of provider taxes: although favored by the industry generally because they enable states to increase reimbursement levels, these taxes tend to be opposed by those with higher proportions of private-pay residents because the industry is less likely to receive taxes back in the way of higher payment (Miller and Wang 2009b). Results reported here provide a useful contrast, illustrating that even in situations where there are no “winners,” the extent to which one segment of the industry loses can nonetheless have a marked effect on the likelihood of adoption. This may be particularly true when that segment is for-profit nursing homes. Not only might they be affected more by WPT programs than non-profit facilities and, as such, have greater incentive to oppose adoption, but they tend to have greater freedom than other industry segments to allocate the resources necessary to mobilize against them.

Given the effectiveness of industry interests in precluding WPT adoption, state officials might consider several strategies with which to gain industry buy-in. This includes better balancing the reimbursement increases obtained with the additional administrative and auditing burdens imposed. It also includes the adoption of more general WPT programs that while requiring the industry to spend more on direct-care staff do not specify in great depth the types of staff or the kinds of expenses to which those increases should be directed. It further includes trading off advancements in one policy area for another. Several states have gained industry support for case-mix reimbursement by instituting a provider tax with which to acquire additional funding (Miller and Wang 2009b). Concurrent implementation of a WPT program with a tax might work the same way. Here a tax could be used to bolster reimbursement beyond what it would have been otherwise, a portion of which could then be used for pass-through purposes. This dynamic played out in at least one state. The responsible implementing official explained: “The legislature passed a provider fee for the first time and the industry supported it. They are now paying a fee and the proceeds from that fee have financed additional wage rate enhancements.”

As noted, results indicate that state officials reacted to prevailing fiscal and programmatic concerns as one would expect. This is reflected in the finding that states with higher unemployment rates and less healthy budgetary situations were less likely to adopt a WPT program. It also is reflected in the finding that states with higher proportions of Medicaid residents were more likely to adopt. Together these findings buttress results from earlier studies suggesting that states react rationally and predictably to prevailing fiscal and programmatic concerns when formulating public policy for Medicaid reimbursement and other areas (Berry and Berry 1990; Harrington, Carrillo, et al. 2000; Miller 2006a, 2006b; Miller and Wang 2009b; Swan, Harrington, and Pickard 2000).

The economy’s role was a particularly noteworthy topic among key stakeholders. This is reflected in the comments of one state Medicaid official who reported that “a pretty good provider once told me, … ‘we do well in bad economic times and we do terrible when it’s booming because we can’t keep the labor force.’” It also is reflected in the comments of another official who, in explaining WPT adoption, reported that the state “had achieved unemployment of about two percent or less. And nursing homes couldn’t compete with other employers. Other employers can bump their prices around and pay their employees more until they can get enough employees. And so nursing homes were losing their nursing assistants to McDonald’s and places like that, who were paying as much or more for much less stressful work. And so basically there was a very strongly conveyed message that more money was needed so that they could pay their workers better so that [they] could provide good care.”

Findings further indicate that states with more professional legislatures and greater administrative capacity were more likely to adopt a WPT program. This suggests that states with greater governing capacity are in a better position to implement such initiatives. This is consistent with the notion that changes to the ways nursing homes are reimbursed often require substantial financial resources, administrative wherewithal, technical expertise, and political support to develop, adopt, and implement (Miller et al. 2009; Miller and Banaszak-Holl 2005). This is reflected in the use of large task forces and informal working groups in some states: “We work together on implementing new programs such as the WPT,” according to one state Medicaid official. “We had a taskforce where we met with the freestanding nursing facility industry, the for-profits, the not-for-profits, the hospitals-based. We even had the advocates and the unions involved in [making the change].” Effectuating innovation, even with respect to small, incremental add-ons such as WPTs, is not easy. Substantial legislative and administrative challenges need to be overcome. Said one Medicaid official: “The legislature … [goes] through and figure[s] out what they want to do. The department goes back and costs it out and gives those figures to the legislature and that’s what gets adopted. We do all the cost estimates… . [But] once the legislation [is] passed then we … [have] to figure out what that really [means]. What are the policies involved? Can you include bonuses? Can you not include bonuses? There’s a lot of little nuances and particulars in that. And that’s what we were involved in.” As a general rule, more complex reimbursement systems with more moving parts require more data and staff to implement and understand (Miller et al. 2009). Absent sufficient capacity, implementation can quickly become an “administrative nightmare,” according to one state informant.