Abstract

Purpose of the Study: To evaluate the extent to which religious affiliation and self-identified religious importance affect advance care planning (ACP) via beliefs about control over life length and end-of-life values. Design and Methods: Three hundred and five adults aged 55 and older from diverse racial and socioeconomic groups seeking outpatient care in New Jersey were surveyed. Measures included discussion of end-of-life preferences; living will (LW) completion; durable power of attorney for healthcare (DPAHC) appointment; religious affiliation; importance of religion; and beliefs about who/what controls life length, end-of-life values, health status, and sociodemographics. Results: Of the sample, 68.9% had an informal discussion and 46.2% both discussed their preferences and did formal ACP (LW and/or DPAHC). Conservative Protestants and those placing great importance on religion/spirituality had a lower likelihood of ACP. These associations were largely accounted for by beliefs about God’s controlling life length and values for using all available treatments. Implications: Beliefs and values about control account for relationships between religiosity and ACP. Beliefs and some values differ by religious affiliation. As such, congregations may be one nonclinical setting in which ACP discussions could be held, as individuals with similar attitudes toward the end of life could discuss their treatment preferences with those who share their views.

Key Words: Advance directive, living wills, durable power of attorney for healthcare

Many religious organizations in the United States have issued formal statements on appropriate end-of-life (EOL) care. The U.S. Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB, 2009) advocates life-sustaining treatments that do not lead to undue suffering, whereas the National Association of Evangelicals (1994) approves withdrawal of life support that unnaturally extends life. Position statements do not, however, fully determine EOL decisions among congregants. Congregants may discuss illness and death during services for the deceased, and the spiritual emphasis of hospice care often attracts congregant volunteers. Therefore, we might anticipate that persons with greater religious participation would be more prone to engage in advance care planning (ACP) because religious exposure may inform knowledge of religious teachings and EOL practices.

This speculative hypothesis, however, is not supported by empirical studies. Self-identified religious importance (hereafter referred to as religiosity), religious service attendance, and positive religious and spiritual coping are negatively associated with ACP likelihood (Allen et al., 2003; Balboni et al., 2007; Phelps et al., 2009; True et al., 2005). These counterintuitive findings raise the following question: Why are highly religious people less likely to engage in ACP, particularly when ACP may specify treatment preferences consistent with one’s religious beliefs, including preferences for intensive medical intervention?

Further, one might expect denominational differences in EOL teachings to translate into different ACP rates; those belonging to religions with specific teachings may have well-defined EOL preferences, making them more likely to engage in ACP. Empirical studies do not support this hypothesis, however; both Catholicism and conservative Protestantism provide detailed EOL teachings to members, yet their members are not consistently more likely than others to do ACP (Black, Reynolds, & Osmand, 2008; Carr & Khodyakov, 2007). Regardless of religious affiliation, the degree to which individuals agree with or follow the teachings of religious organizations varies and may depend on factors such as theological liberalism or conservatism (Sharp, Carr, & MacDonald, 2012).

Although prior studies have evaluated differences in ACP rates and EOL treatment decisions by religious denomination and participation (Black et al., 2008, Phillips et al., 2011; Randall & Bishop, 2012), relatively little is known about why and how religion shapes ACP. Understanding attitudinal factors that encourage ACP is crucial for improving EOL care. Those who do not engage in ACP are at higher risk of having care discordant with their preferences (Mack, Weeks, Wright, Block, & Prigerson 2010). We propose that religiosity and denomination are associated with attitudes regarding individual control over life and death: (a) beliefs about who controls life length and (b) values related to control over physical functioning, social interactions, and spiritual needs at the EOL. These attitudes, in turn, may affect whether one engages in ACP. Our work is guided by the Common Sense Model (CSM) of Illness Representations.

Conceptual Framework

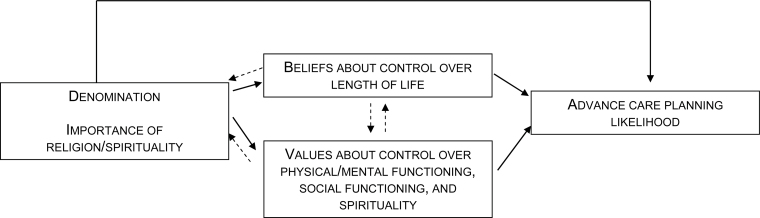

The CSM states that individuals’ perceptions of their own health and illnesses affect the decisions they make when seeking health care (Leventhal, Diefenbach, & Leventhal, 1992). Illness perceptions include perceived controllability of an illness or a scenario (here, EOL in general); those who believe their illness is controllable are more likely to seek treatment. Similarly, those who believe that the timing and nature of death are beyond one’s own control may be less likely to engage in ACP. After defining ACP and religious constructs below, we describe how religiosity and denomination may be associated with beliefs and values about control over the circumstances of one’s own death. We use the CSM to explain how these beliefs and values may influence likelihood of engaging in ACP (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Conceptual model. Solid lines indicate relationships examined in this study. Dashed lines indicate other possible relationships between constructs.

Advance Care Planning.—Various care preferences can be transmitted via ACP, and no set of preferences is “correct.” Further, preferences may change over time. For these reasons, we focus on the completion, but not the content, of ACP. ACP includes informal discussions and formal transmissions of preferences for or against different types of EOL. Formal tools include living wills (LW), which are written records of health care preferences and durable power of attorney for healthcare (DPAHC) appointments, which provide a person with legal authority to make decisions if a patient is incapacitated. Because formal ACP has limitations, including patient access to the document at critical decision-making moments (Perkins, 2007), practitioners encourage supplementation of formal ACP with informal discussions of preferences with family members and care providers. Although discussions are not legally binding, they help patients clarify their treatment preferences and values with those who may represent them in future decisions (Doukas & Hardwig, 2003). Discussions are more nuanced and may better reflect values and beliefs that are influenced by religion than formal planning, which is often initiated in time-limited health care settings by providers (Carr, 2012). Discussions also may appeal to members of religious groups who are uncomfortable with boilerplate language in traditional LWs or that restrict the statements LWs may include (Mitchell & Whitehead, 1993; USCCB, 2009).

Religious Affiliation, Religiosity, and Spirituality.—Most studies find that religiosity/spirituality and theological conservatism are more relevant constructs than specific religious affiliation in influencing EOL care, as individuals within groups vary widely in their adherence to formal denominational teachings (e.g., Sharp et al., 2012). Religiosity refers to formal sets of beliefs and involvement with a religious group, whereas spirituality refers to the “individual’s subjective experience of the sacred” (Idler et al., 2009). Theological conservatism refers to beliefs emphasizing holy writings as direct teachings of God. This perspective is particularly associated with some faith traditions, such as Baptists and other evangelical Christians.

Religion and Beliefs and Values About Control.—

Beliefs about control over length of life. Perceived controllability of health influences actions taken to address health scenarios (Leventhal et al., 1992). Perceived control over the EOL includes the degree to which one believes that the timing of death is determined by God and beyond individual control. Religious affiliation and religiosity/spirituality may influence beliefs about control over life length. Members of conservative religious groups often place great importance on personal relationships with God and believe that life events reflect God’s will. Beliefs that a higher power controls medical outcomes are more prevalent among adherents to theologically conservative than liberal denominations (Sharp et al., 2012). For instance, in a study of EOL beliefs in an African American sample that was primarily Baptist, respondents frequently alluded to “a higher power that has the last say” (Bullock, 2006). By contrast, beliefs that death is a natural part of life may be more prevalent among individuals who view religion as unimportant or who have no religious affiliation; they may be less prone to interpret daily events and experiences as having religious significance (Davis-Berman, 2011).

Values for EOL care. EOL values differ by religiosity and affiliation, and many values reflect the desire to control treatment (e.g., valuing not being connected to machines), situations surrounding death (e.g., the place of death), or relationships (e.g., resolving family disagreements). Catholic teachings that individuals “are not the owners of [their] lives” (USCCB, 2009, p. 29) and that life support should be continued except in extraordinary circumstances may translate into a value emphasizing use of all available treatments at the EOL among some Catholics (Sharp et al., 2012). In addition, religious individuals who believe the circumstances of death are beyond their control may be less likely to value controlling location of death or circumstances surrounding EOL care.

Influence of beliefs and values about control on ACP likelihood. Belief that a higher power controls life length is related to lower formal ACP rates (Carr, 2011; True et al., 2005). If an outcome is viewed as beyond one’s control, and attempting to take control is viewed as counter to God’s will, the CSM suggests that there would be little reason to plan for future health care scenarios and to engage in ACP (see Johnson, Kuchibhatla, & Tulsky, 2008). In addition, valuing religious experiences at the EOL could be associated with lower ACP rates if planning is thought to be against God’s wishes and one conceives of one’s relationship with God in a personal way (True et al., 2005). Persons who highly value life-extending treatment and view it as “as consistent with the will of God in EOL decision-making” may incorrectly view ACP as a tool that necessarily limits treatment and thus have lower ACP rates (Winter, Dennis, & Parker 2009, p. 427; Winter & Parks, 2011).

By contrast, less observant and/or more theologically liberal individuals who believe that death is a natural part of life might be more willing to engage in ACP because taking control over the dying process is consistent with secular beliefs that emphasize individualism and autonomy (Sharp et al., 2012). Individuals who value controlling the circumstances of their death and who view ACP as a means of control should be more likely to engage in ACP.

Other Influences on ACP.—Religious affiliation and religiosity are associated with educational attainment and race, and these both predict ACP rates. Highly educated individuals are less likely to use religious beliefs while making decisions (Schieman, 2011) and more likely to engage in ACP (Carr & Khodyakov, 2007). African Americans are more likely to belong to conservative Protestant denominations (Idler et al., 2009) and are generally less likely to do formal ACP (Kwak & Haley, 2005). They also are more likely to believe that the timing of death is within the hands of God (Carr, 2011). A more in-depth discussion of the intersection of race and religion is beyond the scope of this article but excellent discussions of this topic can be found elsewhere (Bullock, 2006; Phipps et al., 2003; Schmid, Allen, Haley, & DeCoster, 2010; Smith et al., 2008).

In sum, we evaluate pathways by which religious affiliation and religiosity may be associated with ACP in a diverse outpatient sample of adults with chronic illnesses while controlling for sociodemographic factors that may account for a spurious relationship.

Design and Methods

Our sample included community-dwelling adults aged 55 and older from the New Jersey EOL study. Participants were recruited from two hospital clinics and a cancer center and had diagnoses of colorectal cancer, type 2 diabetes, or congestive heart failure. Individuals self-identifying as healthy also were recruited, but in our interviews, most of these participants reported a major health condition. Of the 575 patients meeting inclusion criteria, 53% (n = 305) consented to a face-to-face interview between 2006 and 2008. Reasons for nonparticipation included discomfort with or insufficient time for research participation. Further study details are available elsewhere (Carr, 2011). This study was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of Rutgers University and the University of Medicine and Dentistry of New Jersey.

Dependent Variables

Informal ACP Discussion.—Respondents were asked whether they had discussed EOL health care plans and preferences with anyone: “Have you discussed your plans about the types of medical treatment you want or don’t want to receive if you become seriously ill in the future?”

Formal ACP.—Respondents reported whether they had a “living will or advance directive” or DPAHC. We group these activities together as formal ACP because they typically are done in tandem; 81% of respondents with an LW had a DPAHC and 89% of those with a DPAHC had an LW.

Explanatory Variables

Religious Affiliation.—Respondents chose their affiliation from a list: mainline Protestant (e.g., Episcopalian, Lutheran), conservative Protestant (e.g., Evangelical Christian, Baptist), Catholic (Roman Catholic, Greek Orthodox, Russian Orthodox), Jewish, others (Hindu, Muslim, Unitarian), or none. These affiliations reflect labeling conventions consistent with those used in the literature (Idler et al., 2009; Sherkat, 2010; Smith, 1990), and these labels do not necessarily characterize the specific theological beliefs of persons within each denominational subgroup.

Religiosity and Spirituality.—Respondents rated the importance of religion and spirituality and the degree to which they believed that spiritual or religious beliefs would influence their medical decisions if they were seriously ill (Ehman, Ott, Short, Ciampa, & Hansen-Flaschen, 1999). Religiosity and spirituality were highly correlated (φ = 0.62) and combined into one variable (1 = religion and/or spirituality very or extremely important; 0 = neither very or extremely important). Influence of beliefs on medical decisions was dichotomized (1 = very, extremely; 0 = somewhat, not very much, not at all). Respondents indicated frequency of attendance at religious services. Attendance was correlated with religiosity/spirituality (point biserial correlation = 0.41) and was therefore not included in multivariate models. Instead, we focused on attitudinal aspects of religion.

Beliefs.—Respondents indicated strength of agreement with statements about who/what controls life length (original to study or from Wong, Reker, & Gesser, [1994]). Principal factor analysis produced a God control [GC] (α = 0.89, range 0–4) versus natural death [ND] factor (α = 0.70, range 0–3). The GC score is the average of answers to three items (“It is God’s will when one’s life will end”; “The length of one’s life is determined by God”; and “I believe in turning my health problems over to God”). The ND score is the average of answers to two items (“Death should be viewed as a natural, undeniable and unavoidable event”; “Death is simply a part of the process of life”). Higher scores indicate greater strength of belief.

Values.—Values placed on physical and mental functioning, family and social functioning, and spirituality were assessed. Respondents rated the importance of 14 EOL elements (e.g., “using all available treatments”; adapted from Steinhauser et al. [2000]; full list in Table 1). Responses were dichotomized (very vs somewhat, not very, or not at all important), reflecting the skewed distribution of responses. “Don’t know” responses were coded as missing.

Table 1.

Characteristics of Sample, New Jersey End of Life Study (N = 305)

| Variables | N (%) or M (SD) |

| Advance care planning | |

| Informal discussion | 210 (68.9) |

| Formal ACP | 153 (50.2) |

| Informal and formal ACP | 141 (46.2) |

| Religious affiliation, religiosity, and spirituality | |

| Religious affiliation | |

| Mainline Protestant | 68 (22.3) |

| Conservative Protestant | 50 (16.4) |

| Catholic | 95 (31.1) |

| Jewish | 53 (17.4) |

| Other | 18 (5.9) |

| None | 17 (5.6) |

| Religion and/or spirituality is very or extremely important | 228 (74.8) |

| Religious beliefs will influence medical decisions very much or extremely | 116 (38.0) |

| Number of days attends religious services/year | 36.1 (37.7) |

| Belief scalesa | |

| God controls (GC) life length (3 items; range: 0–4) | 2.6 (1.2) |

| Death is a natural part of life (ND) (2 items; range: 0–3) | 2.4 (0.5) |

| Physical/mental functioning valuesb | |

| Using all available treatments | 92 (30.2) |

| Not being connected to machines | 173 (56.7) |

| Being free of pain | 231 (75.7) |

| Being free of shortness of breath | 227 (74.4) |

| Knowing what to expect about one’s physical condition | 254 (83.3) |

| Being mentally aware | 272 (89.2) |

| Controlling place of death | 81 (26.6) |

| Family/social functioning valuesb | |

| Resolving unfinished business with family and friends | 173 (56.7) |

| Having family and loved ones with | 252 (82.6) |

| Feeling that one’s family is prepared for death | 150 (49.2) |

| Having one’s financial affairs in order | 238 (78.0) |

| Having funeral arrangements planned | 136 (44.6) |

| Spiritual valuesb | |

| Being at peace with God | 240 (78.7) |

| Feelings of life completeness | 163 (53.4) |

| Health | |

| Self-assessed health is fair or poor | 140 (45.9) |

| Number of chronic conditions | 2.6 (1.7) |

| Average ADL/IADL difficulty (range:1–4) | 2.1 (0.9) |

| Sociodemographics | |

| Age | 69.2 (8.8) |

| Female | 193 (63.3) |

| Married | 158 (51.8) |

| Education | |

| Less than a high school education | 59 (19.3) |

| High school education | 92 (30.2) |

| More than a high school education | 153 (50.2) |

| Race | |

| White | 184 (60.3) |

| Black | 80 (26.2) |

| Other | 41 (13.4) |

| Hispanic ethnicity | 55 (18.0) |

| Very or somewhat difficult to pay monthly bills | 119 (39.0) |

Notes: ACP = advance care planning; DPAHC = durable power of attorney for healthcare; ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = independent activities of daily living; ND = natural death.

Formal planning comprises a living will and/or DPAHC.

aHigher numbers indicate stronger beliefs.

bPercentage indicate very important (vs somewhat, not very, or not at all important).

Sociodemographics.—Respondents’ age, gender, marital status, education, race (White, Black, other), and Hispanic ethnicity were recorded. Respondents reported how difficult it was to pay monthly bills (very or somewhat vs not very or not at all).

Health.—We dichotomized self-rated health as fair or poor versus good, very good, or excellent. We included a count of chronic conditions that a doctor had told the respondent he/she had or for which the respondent was taking medications. The average difficulty respondents reported for nine activities of daily living (ADLs) and/or independent activities of daily living (IADLs) was calculated. Higher scores indicate poorer functioning.

Analyses

We used analysis of variance and chi-square tests to examine bivariate associations among religious affiliation, values, beliefs, and informal and formal ACP. We used logistic regression to examine informal discussions and combined ACP (informal plus formal ACP; 92% of respondents with formal ACP also reported informal discussions).

Individuals missing data on GC or ND beliefs, religious affiliation, or sociodemographic or health characteristics were dropped from the regressions, leading to a sample size of 292 for informal discussion models and 291 for combined ACP models. Mean substitution was used for missing values for religiosity/spirituality, the influence of beliefs on medical decisions, and values. Of the regression sample, less than 1% (n = 3) of respondents were missing data on religiosity/spirituality. Twelve percent (n = 36) of respondents were missing data on one or more physical functioning values, 13% (n = 39) were missing data on family values, and 11% (n = 33) were missing data on spiritual values. We constructed a variable indicating when there was at least one missing response for the value questions.

We estimated binary logistic regression models to evaluate the extent to which affiliation and religiosity are associated with ACP and the degree to which these relationships are accounted for by beliefs and/or values. Explanatory variables in each model were as follows: (a) Model 1: religious affiliation; (b) Model 2: affiliation, religiosity/spirituality, influence of religious beliefs; (c) Model 3: Model 2 + belief scales; (d) Model 4: Model 2 + values; (e) Model 5: Model 2 + belief scales + values; and (f) Model 6: Model 5 + sociodemographics and health (see Tables 4 and 5 for full list of variables). Within outcomes, model fit was compared with Akaike’s information criterion with a small sample size correction (AICc). Analyses were performed with SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Inc., Cary, NC).

Table 4.

Odds Ratios (OR) and 95% Confidence Intervals (CIs) From Logistic Regressions Examining Associations Between Informal Discussions and Religion, Beliefs about Control Over Length of Life, Values, Health, and Sociodemographics (n = 292)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religious affiliation | Religious affiliation, religiosity, and spirituality | Model 2 + beliefs | Model 2 + values | Model 2 + beliefs + values | Model 5 + sociodemographics + health status | |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Religious affiliation, religiosity, and spirituality | ||||||

| Conservative Protestant | 0.41 (0.21, 0.81)** | 0.41 (0.20, 0.84)* | 0.65 (0.31, 1.40) | 0.55 (0.24, 1.25) | 0.74 (0.31, 1.77) | 0.87 (0.30, 2.55) |

| Catholic | 0.70 (0.40, 1.23) | 0.71 (0.40, 1.25) | 1.03 (0.56, 1.89) | 1.09 (0.55, 2.17) | 1.26 (0.62, 2.59) | 1.62 (0.66, 3.97) |

| Religion/spirituality is very/ extremely important | 0.65 (0.33, 1.26) | 1.36 (0.62, 2.99) | 0.90 (0.40, 2.05) | 1.40 (0.57, 3.42) | 1.32 (0.50, 3.43) | |

| Religious beliefs will strongly influence medical decisionsa | 1.44 (0.81, 2.57) | 1.93 (1.04, 3.60)* | 1.89 (0.98, 3.67) | 2.56 (1.25, 5.26)* | 2.25 (1.03, 4.94)* | |

| Belief scalesb | ||||||

| God controls (GC) length of life | 0.48 (0.34, 0.67)*** | 0.47 (0.30, 0.72)*** | 0.54 (0.34, 0.87)* | |||

| Death is a natural part of life (natural death, ND) | 1.55 (0.96, 2.51) | 1.57 (0.91, 2.71) | 1.42 (0.78, 2.58) | |||

| Physical/mental functioning valuesc | ||||||

| Using all available treatments | 0.51 (0.27, 0.97)* | 0.47 (0.24, 0.93)* | 0.46 (0.22, 0.96)* | |||

| Not being connected to machines | 2.45 (1.30, 4.62)** | 2.79 (1.43, 5.45)** | 2.48 (1.19, 5.16)* | |||

| Being free of pain | 0.65 (0.30, 1.41) | 0.68 (0.31, 1.49) | 0.75 (0.32, 1.77) | |||

| Being free of shortness of breath | 0.71 (0.32, 1.56) | 0.81 (0.35, 1.87) | 1.14 (0.46, 2.77) | |||

| Knowing what to expect about one’s physical condition | 1.12 (0.47, 2.70) | 1.10 (0.44, 2.77) | 1.08 (0.40, 2.92) | |||

| Being mentally aware | 0.24 (0.06, 0.93)* | 0.24 (0.06, 0.97)* | 0.16 (0.03, 0.78)* | |||

| Controlling place of death | 1.47 (0.71, 3.03) | 1.50 (0.70, 3.20) | 1.71 (0.74, 3.96) | |||

| Family/social functioning values | ||||||

| Resolving unfinished business with family and friends | 0.95 (0.47, 1.91) | 0.93 (0.45, 1.91) | 0.88 (0.40, 1.94) | |||

| Having family and loved ones with | 1.09 (0.50, 2.38) | 1.26 (0.55, 2.88) | 1.46 (0.59, 3.61) | |||

| Feeling that one’s family is prepared for death | 2.59 (1.30, 5.13)** | 2.35 (1.16, 4.78)* | 2.56 (1.19, 5.49)* | |||

| Having one’s financial affairs in order | 1.16 (0.54, 2.49) | 1.01 (0.46, 2.22) | 1.38 (0.57, 3.33) | |||

| Having funeral arrangements planned | 0.77 (0.39, 1.51) | 0.73 (0.36, 1.47) | 0.71 (0.33, 1.51) | |||

| Spiritual values | ||||||

| Being at peace with God | 0.45 (0.17, 1.20) | 1.03 (0.34, 3.14) | 1.12 (0.35, 3.62) | |||

| Feelings of life completeness | 0.70 (0.34, 1.46) | 0.69 (0.32, 1.50) | 0.56 (0.24, 1.32) | |||

| Any missing values observations | 0.33 (0.15, 0.76)** | 0.34 (0.15, 0.80)* | 0.46 (0.18, 1.19) | |||

| Sociodemographics | ||||||

| Age | 1.02 (0.98, 1.06) | |||||

| Female | 1.21 (0.59, 2.46) | |||||

| Married | 1.24 (0.58, 2.63) | |||||

| Less than a high school education | 0.59 (0.24, 1.44) | |||||

| Raced | ||||||

| Black | 0.59 (0.21, 1.66) | |||||

| Other | 0.38 (0.14, 1.05) | |||||

| Hispanic ethnicity | 0.29 (0.10, 0.83)* | |||||

| Very/somewhat difficult to pay monthly bills | 1.80 (0.81, 3.98) | |||||

| Health | ||||||

| Self-assessed health—fair or poor | 0.76 (0.34, 1.67) | |||||

| Number of chronic conditions | 0.99 (0.79, 1.25) | |||||

| Average ADL/IADL difficulty | 1.45 (0.92, 2.27) | |||||

| AICc | 363.16 | 364.88 | 344.45 | 341.00 | 329.65 | 331.11 |

Notes: ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = independent activities of daily living; AICc = Akaike’s information criterion with a correction for small sample size.

aReligious beliefs will influence medical decisions “very much or extremely” vs not at all, not very, or somewhat.

bHigher numbers indicate stronger beliefs.

cVery important vs somewhat, not very, or not at all important.

dReference category is White.

*p < .05. ** p < .01. ***p < .001.

Table 5.

Odds Ratios (OR) and Confidence Intervals (CI) from Logistic Regressions Examining Associations Between Combined ACP (Informal Discussion plus a LW and/or a DPAHC) and Religion, Beliefs about Control Over Length of Life, Values, Health, and Sociodemographics (n = 291)

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Religious affiliation | Religious affiliation, religiosity, and spirituality | Model 2 + beliefs | Model 2 + values | Model 2 + beliefs + values | Model 5 + sociodemographics + health status | |

| OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | OR (95% CI) | |

| Religious affiliation, religiosity, and spirituality | ||||||

| Conservative Protestant | 0.29 (0.14, 0.60)*** | 0.33 (0.16, 0.70)** | 0.54 (0.25, 1.21) | 0.43 (0.18, 1.01) | 0.56 (0.23, 1.37) | 1.22 (0.38, 3.90) |

| Catholic | 0.57 (0.34, 0.96)* | 0.60 (0.35, 1.01) | 0.87 (0.49, 1.54) | 0.89 (0.48, 1.68) | 0.99 (0.52, 1.90) | 1.05 (0.46, 2.39) |

| Religion/spirituality is very/ extremely important | 0.57 (0.31, 1.05) | 1.11 (0.54, 2.26) | 0.98 (0.47, 2.08) | 1.33 (0.60, 2.93) | 1.66 (0.70, 3.96) | |

| Religious beliefs will strongly influence medical decisionsa | 1.11 (0.64, 1.92) | 1.46 (0.80, 2.65) | 1.17 (0.62, 2.20) | 1.38 (0.71, 2.71) | 1.07 (0.50, 2.27) | |

| Belief Scalesb | ||||||

| God controls (GC) length of life | 0.50 (0.37, 0.67)*** | 0.54 (0.38, 0.78)*** | 0.69 (0.46, 1.03) | |||

| Death is a natural part of life (natural death, ND) | 1.82 (1.13, 2.93)* | 1.78 (1.06, 3.00)* | 1.82 (1.03, 3.23)* | |||

| Physical/mental functioning valuesc | ||||||

| Using all available treatments | 0.60 (0.33, 1.10) | 0.57 (0.31, 1.08) | 0.50 (0.25, 1.02) | |||

| Not being connected to machines | 1.72 (0.96, 3.09) | 1.86 (1.01, 3.42)* | 1.66 (0.85, 3.22) | |||

| Being free of pain | 0.75 (0.39, 1.43) | 0.70 (0.36, 1.39) | 0.80 (0.38, 1.66) | |||

| Being free of shortness of breath | 0.39 (0.20,0.76)** | 0.43 (0.21, 0.88)* | 0.46 (0.22, 0.998)* | |||

| Knowing what to expect about one’s physical condition | 0.94 (0.43, 2.03) | 0.92 (0.40, 2.07) | 0.94 (0.39, 2.31) | |||

| Being mentally aware | 0.50 (0.20, 1.25) | 0.52 (0.20, 1.35) | 0.45 (0.16, 1.27) | |||

| Controlling place of death | 2.08 (1.09, 4.00)* | 2.18 (1.10, 4.32)* | 2.80 (1.29, 6.09)** | |||

| Family/social functioning values | ||||||

| Resolving unfinished business with family and friends | 0.97 (0.50, 1.88) | 0.93 (0.47, 1.83) | 1.02 (0.49, 2.14) | |||

| Having family and loved ones with | 0.65 (0.32, 1.31) | 0.75 (0.36, 1.58) | 0.85 (0.37, 1.93) | |||

| Feeling that one’s family is prepared for death | 1.60 (0.86, 2.99) | 1.44 (0.75, 2.75) | 1.38 (0.67, 2.84) | |||

| Having one’s financial affairs in order | 0.86 (0.43, 1.73) | 0.75 (0.36, 1.54) | 0.98 (0.44, 2.21) | |||

| Having funeral arrangements planned | 1.21 (0.66, 2.22) | 1.19 (0.63, 2.24) | 1.30 (0.64, 2.64) | |||

| Spiritual values | ||||||

| Being at peace with God | 0.45 (0.19, 1.03) | 0.96 (0.36, 2.54) | 1.03 (0.36, 2.90) | |||

| Feelings of life completeness | 0.99 (0.50, 1.97) | 1.04 (0.51, 2.14) | 0.76 (0.34, 1.72) | |||

| Any missing values observations | 0.56 (0.23, 1.34) | 0.59 (0.24, 1.45) | 0.66 (0.24, 1.78) | |||

| Sociodemographics | ||||||

| Age | 1.00 (0.96, 1.04) | |||||

| Female | 0.55 (0.28, 1.10) | |||||

| Married | 0.64 (0.31, 1.33) | |||||

| Less than a high school education | 0.57 (0.20, 1.64) | |||||

| Raced | ||||||

| Black | 0.18 (0.06, 0.55)** | |||||

| Other | 0.21 (0.05, 0.77)* | |||||

| Hispanic ethnicity | 0.14 (0.04, 0.47)** | |||||

| Very/somewhat difficult to pay monthly bills | 1.24 (0.59, 2.61) | |||||

| Health | ||||||

| Self-assessed health—fair or poor | 1.68 (0.76, 3.75) | |||||

| Number of chronic conditions | 0.96 (0.77, 1.20) | |||||

| Average ADL/IADL difficulty | 1.26 (0.81, 1.95) | |||||

| AICc | 394.39 | 395.09 | 368.45 | 372.83 | 359.52 | 345.71 |

Notes: ACP = advance care planning; DPAHC = durable power of attorney for healthcare; LW = living will; ADL = activities of daily living; IADL = independent activities of daily living; AICc = Akaike’s Information Criterion with a correction for small sample size.

aReligious beliefs will influence medical decisions “very much or extremely” versus not at all, not very, or somewhat.

bHigher numbers indicate stronger beliefs.

cVery important vs somewhat, not very, or not at all important.

dReference category is White.

* p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Results

The average age of respondents was 69 years (range 55–90), and 63.3% were female (Table 1). The sample was 60.3% White, 26.2% Black, and 13.4% other race. Eighteen percent were Hispanic. About half (45.9%) had fair or poor self-rated health. Over two thirds (68.9%) reported an informal discussion and half had an LW and/or a DPAHC (50.2%). Of those with discussions, 67.8% did formal ACP; 46.2% did a combination of informal and formal ACP.

The most common religious affiliations were Catholic (31.1%), mainline Protestant (22.3%), Jewish (17.4%), and conservative Protestant (16.4%). Religion/spirituality was very or extremely important to most respondents (74.8%).

More than half the respondents highly valued the following physical and mental functioning items: being mentally aware (89.2%), knowing what to expect about one’s condition (83.3%), freedom from pain (75.7%), freedom from shortness of breath (74.4%), and not being connected to machines (56.7%). Over half highly valued the following family and social functioning items: having loved ones nearby at the EOL (82.6%), having financial affairs in order (78.0%), and resolving unfinished business with family and friends (56.7%). Of the spiritual values, over half highly valued being at peace with God (78.7%) and feeling that one’s life is complete (53.4%).

Most values were correlated only weakly within categories (|Cramer’s V| = 0.00–0.31, physical and mental functioning; 0.03–0.31, family and social functioning; 0.14, spiritual functioning). GC and ND beliefs were not significantly correlated (Pearson correlation coefficient = −0.03; Table 2).

Table 2.

Intercorrelationsa Between Religion/Spirituality Variables Used in Multivariate Analysis (N = 292)

| Conservative Protestant affiliation | Catholic affiliation | Religion/spirituality very or extremely important | Religious beliefs will strongly influence medical decisionsb | Strongly valuing being at peace with God | Strongly valuing feelings of life completeness | GC beliefs | |

| Religion/spirituality: very or extremely important | 0.237*** | 0.043 | |||||

| Religious beliefs will strongly influence medical decisionsb | 0.258*** | 0.005 | 0.427*** | ||||

| Strongly valuing being at peace with God | 0.232*** | 0.251*** | 0.498*** | 0.342*** | |||

| Strongly valuing feelings of life completeness | 0.127* | −0.098 | 0.131* | 0.170** | 0.139* | ||

| GC beliefs | 0.277*** | 0.179** | 0.539*** | 0.419*** | 0.680*** | 0.101 | |

| ND beliefs | −0.112 | −0.026 | 0.026 | 0.075 | 0.016 | 0.066 | −0.029 |

Notes: GC = God control; ND = natural death.

aPearson correlations are listed when at least one variable is continuous. Phi values are listed when both variables are dichotomous.

bReligious beliefs will influence medical decisions “very much or extremely” vs not at all, not very, or somewhat.

* p < .05. ** p < .01. *** p < .001.

Bivariate Associations Among Religious Affiliation, Beliefs, Values, and ACP

Chi-square tests (Table 3) revealed that Jewish respondents had the highest rates of informal discussions (86.8%), formal ACP (70.8%), and combined informal and formal ACP (76.9%), whereas conservative Protestant respondents had the lowest ACP rates (discussions: 54.0%, formal ACP: 32.0%, and combined ACP: 26.0%).

Table 3.

Chi-Square Tests and ANOVAs Between Religious Affiliation and Religiosity, Spirituality, Beliefs, Values, and Type of ACP (n = 301)a

| Variables | Conservative Protestant (n = 50) | Mainline Protestant (n = 68) | Catholic (n = 95) | Jewish (n = 53) | Other (n = 18) | None (n = 17) | p valueb |

| Advance care planning (N, %) | |||||||

| Informal discussion | 27 (54.0) | 46 (67.7) | 63 (66.3) | 46 (86.8) | 11 (61.1) | 14 (82.4) | .009 |

| Formal | 16 (32.0) | 32 (47.8) | 43 (45.3) | 42 (80.8) | 9 (50.0) | 11 (64.7) | <.001 |

| Informal and formal | 13 (26.0) | 29 (42.7) | 40 (42.1) | 40 (76.9) | 8 (44.4) | 11 (64.7) | <.001 |

| Religiosity and spirituality, N (%) or M (SD) | |||||||

| Religion and/or spirituality is very or extremely important | 49 (98.0) | 58 (85.3) | 74 (77.9) | 25 (47.2) | 15 (83.3) | 4 (23.5) | <.001 |

| Annual mean attendance at religious services | 58.6 (37.9) | 39.8 (35.8) | 39.9 (38.2) | 15.1 (27.1) | 37.5 (37.2) | 2.3 (7.2) | <.001 |

| Religious beliefs will strongly influence medical decisionsc | 33 (66.0) | 29 (42.6) | 37 (38.9) | 8 (15.1) | 7 (38.9) | 2 (11.8) | <.001 |

| Belief scale,d Mean score (SD) | |||||||

| God controls (GC) life length | 3.3 (0.7) | 2.8 (1.0) | 2.9 (1.0) | 1.7 (1.0) | 2.6 (1.1) | 0.8 (0.9) | <.001 |

| Death is a natural part of life (natural death, ND) | 2.3 (0.5) | 2.4 (0.6) | 2.4 (0.5) | 2.5 (0.5) | 2.6 (0.5) | 2.7 (0.4) | .08 |

| Valuese, N (%) | |||||||

| Physical/mental functioning values | |||||||

| Using all available treatments | 23 (46.0) | 19 (27.9) | 28 (29.5) | 14 (26.4) | 4 (22.2) | 2 (11.8) | .08 |

| Not being connected to machines | 30 (60.0) | 38 (55.9) | 52 (54.7) | 29 (54.7) | 12 (66.7) | 11 (64.7) | .90 |

| Being free of pain | 43 (86.0) | 49 (72.1) | 71 (74.7) | 37 (69.8) | 15 (83.3) | 13 (76.5) | .42 |

| Being free of shortness of breath | 47 (94.0) | 51 (75.0) | 76 (80.0) | 29 (54.7) | 14 (77.8) | 9 (52.9) | <.001 |

| Knowing what to expect about one’s physical conditionf | 44 (88.0) | 59 (86.8) | 79 (83.2) | 41 (77.4) | 15 (83.3) | 13 (76.5) | .65 |

| Being mentally awaref | 48 (96.0) | 59 (86.8) | 83 (87.4) | 47 (88.7) | 17 (94.4) | 15 (88.2) | .59 |

| Controlling place of death | 19 (38.0) | 14 (20.6) | 20 (21.1) | 19 (35.9) | 5 (27.8) | 4 (23.5) | .13 |

| Family/social functioning values | |||||||

| Resolving unfinished business with family and friends | 35 (70.0) | 42 (61.8) | 48 (50.5) | 30 (56.6) | 9 (50.0) | 7 (41.2) | .17 |

| Having family and loved ones with | 43 (86.0) | 51 (75.0) | 81 (85.3) | 45 (84.9) | 15 (83.3) | 14 (82.4) | .57 |

| Feeling that one’s family is prepared for death | 27 (54.0) | 33 (48.5) | 41 (43.2) | 30 (56.6) | 9 (50.0) | 8 (47.1) | .69 |

| Having one’s financial affairs in order | 43 (86.0) | 53 (77.9) | 75 (78.9) | 40 (75.5) | 12 (66.7) | 12 (70.6) | .55 |

| Having funeral arrangements planned | 35 (70.0) | 29 (42.6) | 32 (33.7) | 27 (50.9) | 6 (33.3) | 4 (23.5) | <.001 |

| Spiritual values | |||||||

| Being at peace with God | 50 (100.0) | 60 (88.2) | 89 (93.7) | 24 (45.3) | 14 (77.8) | 1 (5.9) | <.001 |

| Feelings of life completeness | 33 (66.0) | 41 (60.3) | 45 (47.4) | 29 (54.7) | 7 (38.9) | 7 (41.2) | .13 |

Notes: ANOVA = analysis of variance; ACP = advance care planning.

aReligious affiliation data are missing for four respondents. Percentages are calculated out of non-missing observations.

b p values reported are from the overall comparison of means across all categories. Post hoc analyses demonstrate that conservative Protestant respondents differ significantly (p < .05) from all other groups on the measures that are significant across all categories as well as belief in death as a natural part of life, valuing having all available treatments and resolving unfinished business with family and friends.

cReligious beliefs will influence medical decisions “very much or extremely” vs not at all, not very, or somewhat.

dHigher numbers indicate stronger beliefs.

ePercentage indicating very important (vs. somewhat, not very, or not at all important).

fChi-square test may not be valid due to fewer than five observations in at least two cells or 0 observations in one or more cells.

Religious affiliation was significantly associated with religiosity/spirituality, with conservative Protestants the most likely to report that religion/spirituality were very or extremely important to them (98.0% of conservative Protestants). They were the most likely to report that religious beliefs would influence their medical decisions (67.4%) and had the highest religious service attendance.

Conservative Protestants had the strongest GC beliefs, whereas Jewish and nonaffiliated respondents had the weakest. A post hoc two-sample t test found that conservative Protestants had significantly weaker ND beliefs when compared with all other respondents.

Few values were significantly related to affiliation. Under physical and mental functioning values, conservative Protestants were more likely (94.0%) than Jewish (54.7%) and nonaffiliated respondents (52.9%) to highly value freedom from shortness of breath (p < .001). With respect to family and social functioning values, conservative Protestants were the most likely to highly value planned funeral arrangements (p < .001). Among spiritual values, conservative Protestants (100.0%) and Catholics (93.7%) were more likely than Jewish (45.3%) or nonaffiliated respondents (5.9%) to value peace with God (p < .001). Because we did not have sufficient sample size to include each affiliation in our multivariate models, we categorized respondents as conservative Protestant, Catholic, or other.

Informal Discussions—Multivariable Models

Conservative Protestant, but not Catholic, affiliation was associated with lower discussion likelihood (Odds Ratio [OR] = 0.41, 95% Confidence Interval [CI] = 0.21–0.81). This effect persisted after we adjusted for other religion variables (Model 2, Table 4). The conservative Protestant effect was accounted for by the addition of beliefs and values to the model. When beliefs were considered (Model 3), affiliation was no longer significant, and stronger GC beliefs were associated with lower discussion likelihood (OR [CI] = 0.48 [0.34–0.67]). Stronger beliefs that religious beliefs would influence decisions were associated with greater discussion likelihood (OR [CI]= 1.93 [1.04–3.60]). Valuing using all available treatments was associated with lower discussion odds (OR [CI]= 0.51 [0.27–0.97]; Model 4), and this variable also eliminated the effect of affiliation. Other values were associated with discussion likelihood. Persons who strongly valued mental awareness were less likely to have discussions (OR [CI]= 0.24 [0.06–0.93]). Discussions were more likely among respondents who strongly valued avoiding machines (OR [CI]= 2.45 [1.30–4.62]) and feeling that one’s family is prepared for death (OR [CI]= 2.59 [1.30–5.13]). When values and beliefs were added to the model simultaneously (Model 5), the relationships among values, beliefs, and ACP remained the same. These relationships persisted and model fit did not improve when we controlled for sociodemographics and health (Model 6).

Combined ACP—Multivariable Models

Conservative Protestantism (OR [CI]= 0.29 [0.14–0.60]; Model 1, Table 5) and Catholicism (OR [CI]= 0.57 [0.34–0.96]) were associated with lower odds of combined ACP. However, when other religion variables were added to the model, only conservative Protestant affiliation remained associated with lower combined ACP likelihood (OR [CI] = 0.33 [0.16–0.70]; Model 2). Religiosity/spirituality (negatively associated with combined ACP likelihood in chi-square tests) fully accounted for the Catholic effect but only partially accounted for the conservative Protestant effect.

As with discussions, associations between conservative Protestantism and combined ACP were accounted for by both beliefs and values. When beliefs were added to the model (Model 3), stronger GC beliefs were associated with lower combined ACP likelihood (OR [CI] = 0.50 [0.37–0.67]), and stronger ND beliefs were associated with higher combined ACP likelihood (OR [CI] = 1.82 [1.13–2.93]). Valuing freedom from shortness of breath (valued strongly by conservative Protestants) was associated with lower combined ACP likelihood (OR [CI]= 0.39 [0.20–0.76]; Model 4). Strongly valuing controlling place of death, which was not associated with religious affiliation, was associated with twice the odds of combined ACP (OR [CI]= 2.08[1.09–4.00]).

When values and beliefs were analyzed simultaneously (Model 5), the relationships among combined ACP and beliefs and values remained the same as in previous models. However, controlling for health and sociodemographics in the final model (Model 6) improved model fit and accounted for some of the relationships among beliefs, values, and combined ACP. Stronger ND beliefs and valuing controlling place of death remained associated with higher odds of combined ACP, and valuing freedom from shortness of breath remained associated with lower odds of combined ACP. We ran a sensitivity analysis in which “influence of beliefs on medical decisions” was split into three categories (not at all/not very, somewhat, very/extremely) rather than dichotomized. Shortness of breath was no longer associated with combined ACP in this specification.

Discussion

Our study examined whether and how religion affects ACP via beliefs and values about EOL control. Strong bivariate associations between religious affiliation and ACP were largely accounted for by beliefs and values about control in multivariate models. Beliefs about God’s control over life length differed by affiliation, but, contrary to our hypotheses, many values about control over the EOL were equally important across religious groups. Overall, beliefs in God’s control over life length were associated with lower likelihood of ACP (either informal or formal), whereas valuing individual control over EOL circumstances was associated with greater ACP likelihood. This is in line with the CSM; individuals are more likely to engage in health-related actions when they perceive control over an illness or scenario.

Religious Affiliation and ACP

Conservative Protestants were the least likely to engage in ACP, and Catholic respondents were less likely to engage in ACP than respondents with Jewish or no religious affiliation. Similar patterns have been observed elsewhere (Black et al., 2008; Carr & Khodyakov, 2007). The relationship between Catholic affiliation and ACP disappeared after accounting for religiosity/spirituality. Catholic respondents were more likely to view religion/spirituality as very important compared with Jewish respondents or those with no affiliation, and highly religious/spiritual individuals from any affiliation were less likely to do ACP. By contrast, the relationship between conservative Protestantism and ACP persisted after accounting for religiosity/spirituality and largely reflects differences by affiliation in beliefs about control over life length and in EOL values. One possible explanation is that conservative Protestants are more theologically conservative, and theologically conservative beliefs—such as literal interpretation of the Bible—can pose obstacles to ACP (Sharp et al., 2012).

Beliefs About God’s Control Over Life Length

The relationship between conservative Protes- tantism and lower rates of informal ACP discussions was accounted for by stronger beliefs in God’s control over life length. Because conservative Protestants are more likely to believe that an outside entity controls life length, they may feel less of a need to plan for the EOL. Their lower combined ACP likelihood also was partly accounted for by GC beliefs, but this relationship was not evident after controlling for health and socio demographics. This may reflect the fact that African Americans are over-represented among conservative Protestants, and African Americans have lower ACP rates than Whites (Carr, 2011).

The relationship between conservative Protes tantism and lower rates of combined ACP was also accounted for by weaker beliefs in death as a natural part of life. Those endorsing this belief were more likely to engage in combined ACP. Persons who do not believe that God controls life length might feel a need to appoint a specific person to take control in case they are incapacitated. “Control over the future” is one reason for wanting an LW or a DPAHC (Phipps et al., 2003). Individuals who believe that death is a natural part of life may engage in ACP because they want to ensure that they have an opportunity to die when nature—not medicine—intended (Cohen-Mansfield et al., 1991). Alternatively, individuals who believe that death is a natural event may be less fearful of discussing death, making them more likely to engage in ACP.

Values Regarding Control Over EOL

The association between conservative Protes tantism and low discussion rates was accounted for by valuing having all available treatments. Individuals valuing all treatments may not feel a need to discuss preferences; when preferences are unknown, the default is often to receive life-sustaining treatments. These results align with other studies showing that valuing all treatments coincides with stronger faith in God (Winter et al., 2009) and that persons preferring aggressive treatments are less likely to do ACP (Winter & Parks, 2011).

The association between conservative Protestantism and low combined ACP likelihood also was accounted for by valuing freedom from shortness of breath in some models. This value may indicate that individuals want control over EOL oxygen access and do not want to limit treatment options via ACP. There may be a misconception that dyspnea would not be addressed when treatments such as ventilation are restricted, when in fact, shortness of breath is a common symptom focus of palliative care. This relationship may be spurious; it weakened when we controlled for sociodemographics, and the conservative Protestants in our sample are of lower socioeconomic status.

Other values associated with preferences for individual control over the dying process were associated with ACP likelihood without being associated with affiliation; they were held in equal proportions across religious affiliations. Avoiding machines and feeling that one’s family is prepared for death were related to greater discussion likelihood. Valuing controlling place of death was associated with higher combined ACP likelihood. A desire to be mentally aware at the EOL was associated with lower discussion likelihood, perhaps reflecting a belief that one would retain sufficient mental clarity to make his/her own EOL decisions. Several of these control values are characteristic of what many view as a “good” death (Carr, 2012). Additionally, our sample was relatively highly educated, and highly educated people tend to value control over fatalism (Powe & Finnie, 2003). This suggests that there may be individuals in religious groups that have traditionally shied away from ACP who want more control over the EOL. Educating individuals that ACP is about transmitting preferences and that it is not synonymous with limiting treatment may promote receipt of care concordant with values and spiritual needs.

Limitations

Our results provide insight into the roles of control beliefs and values in the relationship between religion and ACP behaviors, but denominations are only one of several factors influencing individuals’ health-related decisions. Theological liberal and conservative Catholics and Protestants differ widely in preferences for EOL treatments (Sharp et al., 2012); heterogeneity of Catholic EOL viewpoints was dramatically demonstrated in the case of Terri Schiavo. Our sample size does not allow us to stratify Catholics or conservative Protestants by ideological beliefs; however, the nonsignificant effects of Catholicism may reflect heterogeneity within the category.

In addition, our results among conservative Protestants might be confounded by race, as 86% of the conservative Protestant respondents were African American. However, adding sociodemographics to our analysis of informal discussions did not improve model fit. For combined ACP, there was a difference by race, with White and non-Hispanic respondents more likely than other respondents to have engaged in combined ACP. This is consistent with most existing literature (Kwak & Haley, 2005; Phipps et al., 2003; Smith et al., 2008).

Our sample size precluded us from examining relationships between ACP rates and differences in values beyond the dichotomies we studied and from accounting for the effect of unobserved variables on the probability of having missing responses on the values questions. In addition, our sample’s religious distribution differs from the national distribution; it includes fewer conservative Protestant (16.6%) and more Jewish (17.6%) respondents than in the United States overall (26.3%; 1.7%, respectively; Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life, 2008). Our findings are only generalizable to others within Judeo-Christian belief systems. Furthermore, these data are cross-sectional, so we cannot determine how religion, values, and beliefs influence each other.

Conclusions and Implications for Policy and Practice

ACP encompasses discussions as well as formal documents such as LWs. Although most religious groups do not prohibit the use of LWs or DPAHCs, they may recommend restrictions on what kinds of treatments can be specified in these documents or who is designated to resolve treatment dilemmas (Grodin, 1993; USCCB, 2009). For these reasons, highly religious individuals, especially those with a strong belief in God’s control over the EOL, may be hesitant to engage in any kind of ACP. One type of ACP that may be more appealing to religious individuals is the more flexible and personal “Five Wishes Document,” where individuals can document wishes found in traditional LWs as well as religious beliefs (http://www.agingwithdignity.org/five-wishes.php).

Our findings could inform interfaith clergy training programs about EOL care, perhaps modeled after the former Robert Wood Johnson Foundation Compassion Sabbath program (http://www.rwjf.org/reports/grr/038338.htm). Religious congregations could work with members to engage in ACP modes that are in line with religious teachings and individual beliefs and values. Although there is heterogeneity of beliefs and actions within affiliations, congregations may be a good nonclinical setting in which to have ACP discussions. Congregational leaders who can interpret religious teachings might enable individuals who might not otherwise plan for the EOL to consider ACP. It is important to have ACP discussions in community settings before medical crises occur, without the stressful context of immediate life-and-death decision making.

Funding

D. Carr was the PI of the New Jersey End of Life Study, which was funded by a grant from the National Institute of Aging to the Center for the Study of Health Beliefs and Behaviors, Rutgers University (AG023958). M. Garrido was a National Institute of Mental Health postdoctoral trainee (T32 MH16242-29) at Rutgers University at the time this study was completed and is currently supported by a Junior Faculty Career Development Award from the National Palliative Care Research Center.

Conflict of Interest

No competing financial interests exist. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the position or policy of the Department of Veterans Affairs or the United States government.

References

- Allen R. S., DeLaine S. R., Chaplin W. F., Marson D. C., Bourgeois M. S., Dijkstra K., Burgio L. D. (2003). Advance care planning in nursing homes: Correlates of capacity and possession of advance directives. The Gerontologist, 43, 309–317. 10.1093/geront/43.3.309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balboni T., Vanderwerker L. C., Block S. D., Paulk M. E., Lathan C. S., Peteet J. R., Prigerson H. G. (2007). Religiousness and spiritual support among advanced cancer patients and associations with end-of-life treatment preferences and quality of life. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 25, 555–560. 10.1200/JCO.2006.07.9046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Black K., Reynolds S. L., Osman H. (2008). Factors associated with advance care planning among older adults in southwest Florida. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 27, 93–109. 10.1177/0733464807307773 [Google Scholar]

- Bullock K. (2006). Promoting advance directives among African Americans: A faith-based model. Journal of Palliative Medicine, 9, 183–195. 10.1089/jpm.2006.9.183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D. (2011). Racial differences in end-of-life planning: Why don’t Blacks and Latinos prepare for the inevitable? Omega—Journal of Death & Dying, 63(1)1–20. 10.2190/OM.63.1.a [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D. (2012). ‘I don’t want to die like that…’: The impact of significant others’ death quality on advance care planning. The Gerontologist. Advance online publication. 10.1093/geront/gns051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr D., Khodyakov D. (2007). End-of-life health care planning among young-old adults: An assessment of psychosocial influences. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences, 62B(2)135–141 Retrieved from http://psychsocgerontology.oxfordjournals.org/ (accessed on October 4, 2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen-Mansfield J., Rabinovich B. A., Lipson S., Fein A., Gerber B., Weisman S., Pawlson G. (1991). The decision to execute a durable power of attorney for health care and preferences regarding the utilization of life-sustaining treatments in nursing home residents. Archives of Internal Medicine, 151, 289–294. 10.1001/archinte.1991.00400020053012 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis-Berman J. (2011). Conversations about death: Talking to residents in independent, assisted, and long-term care settings. Journal of Applied Gerontology, 30, 353–369. 10.1177/ 0733464810367637 [Google Scholar]

- Doukas D. J., Hardwig J. (2003). Using the family covenant in planning end-of-life care: Obligations and promises of patients, families, and physicians. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 51, 1155–1158. 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2003.51383.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehman J., Ott B., Short T., Ciampa R., Hansen-Flaschen J. (1999). Do patients want physicians to inquire about their spiritual or religious beliefs if they become gravely ill? Archives of Internal Medicine, 159, 1803–1806. 10–1001/pubs.Arch Intern Med.-ISSN-0003-9926-159-15-ioi80537 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grodin M. A. (1993). Religious advance directives: The convergence of law, religion, medicine, and public health. American Journal of Public Health, 83, 899–903. 10.2105/AJPH.83.6.899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idler E. L., Boulifard D. A., Labouvie E., Chen Y. Y., Krause T. J., Contrada R. J. (2009). Looking inside the black box of “attendance at services”: New measures for exploring an old dimension in religion and health research. International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 19(1)1–20. 10.1080/10508610802471096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson K. S., Kuchibhatla M., Tulsky J. A. (2008). What explains racial differences in the use of advance directives and attitudes toward hospice care? Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 56, 1953–1958. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2008.01919.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal H., Diefenbach M., Leventhal E. A. (1992). Illness cognition: Using common sense to understand treatment adherence and affect cognition interactions. Cognitive Therapy & Research, 16(2)143–163. 10.1007/BF01173486 [Google Scholar]

- Kwak J., Haley W. E. (2005). Current research findings on end-of-life decision making among racially or ethnically diverse groups. The Gerontologist, 45, 634–641. 10.1093/geront/45.5.634 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mack J. W., Weeks J. C., Wright A. A., Block S. D., Prigerson H. G. (2010). End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: Predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 28, 1203–1208. 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell C. B., Whitehead M. K. (1993). A time to live, a time to die: Advance directives and living wills. Ethics & Medicine, 9(1)2–5 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Association of Evangelicals (1994). Euthanasia: Termination of medical treatment Retrieved from http://www.euthanasia.com/evangel.html (accessed on March 8, 2012)

- Perkins H. S. (2007). Controlling death: The false promise of advance directives. Annals of Internal Medicine, 147, 51–57 Retrieved from http://annals.org/journal.aspx (accessed on October 4, 2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pew Forum on Religion and Public Life (2008). U.S. religious landscape survey. Religious beliefs and practices: Diverse and politically relevant. Pew Forum Retrieved from http://religions.pewforum.org/pdf/report2-religious-landscape-study-full.pdf (accessed on October 4, 2012).

- Phelps A. C., Maciejewski P. K., Nilsson M., Balboni T. A., Wright A. A., Paulk M. E., et al. (2009). Religious coping and use of intensive life-prolonging care near death in patients with advanced cancer. Journal of the American Medical Association, 301, 1140–1147. 10.1001/jama.2009.341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips L. L., Allen R. S., Harris G. M., Presnell A. H., DeCoster J., Cavanaugh R. (2011). Aging prisoners’ treatment selection: Does prospect theory enhance understanding of end-of-life medical decisions? The Gerontologist, 51, 663–674. 10.1093/geront/gnr039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phipps E., True G., Harris D., Chong U., Tester W., Chavin S. I., Braitman L. E. (2003). Approaching the end of life: Attitudes, preferences, and behaviors of African-American and White patients and their family caregivers. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 21(3)549–554. 10.1200/JCO.2003.12.080 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powe B., Finnie R. (2003). Cancer fatalism: The state of the science. Cancer Nursing, 26(6)454–465 Retrieved from http://journals.lww.com/cancernursingonline/pages/default.aspx (accessed on October 4, 2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall G. K., Bishop A. J. (2012). Direct and indirect effects of religiosity on valuation of life through forgiveness and social provisions among older incarcerated males. The Gerontologist. Advance online publication. 10.1093/geront/gns070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schieman S. (2011). Education and the importance of religion in decision making: Do other dimensions of religiousness matter? Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 50(3)570–587. 10.1111/j.1468-5906.2011.01583.x [Google Scholar]

- Schmid B., Allen R. S., Haley P. P., DeCoster J. (2010). Family matters: Dyadic agreement in end-of-life medical decision making. The Gerontologist, 50, 226–237. 10.1093/geront/gnp166 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharp S., Carr D., MacDonald C. (2012). Religion and end-of-life treatment preferences: Assessing the effects of religious denomination, beliefs, and practices. Social Forces, 91, 275–298 Retrieved from http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/social_forces/ (accessed on October 4, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- Sherkat D. E. (2010). The religious demography of the United States: Dynamics of affiliation, participation, and belief. In Ellison C., Hummer R. (Eds.), Religion, families, and health: Population-based research in the United States (pp. 403–430). New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press; [Google Scholar]

- Smith A. K., McCarthy E. P., Paulk E., Balboni T. A., Maciejewski P. K., Block S. D., Prigerson H. G. (2008). Racial and ethnic differences in advance care planning among patients with cancer: Impact of terminal illness acknowledgement, religiousness, and treatment preferences. Journal of Clinical Oncology, 26, 4131–4137. 10.1200/JCO.2007.14.8452 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith T. W. (1990). Classifying Protestant denominations. Review of Religious Research, 31, 225–245 Retrieved from http://rra.hartsem.edu/reviewof.htm (accessed on October 4, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- Steinhauser K., Christakis N., Clipp E., McNeilly M., McIntyre L., Tulsky J. (2000). Factors considered important at the end of life by patients, family, physicians, and other care providers. Journal of the American Medical Association, 284, 2476–2482. 10.1001/jama.284.19.2476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- True G., Phipps E. J., Braitman L. E., Harralson T., Harris D., Tester W. (2005). Treatment preferences and advance care planning at the end of life: The role of ethnicity and spiritual coping in cancer patients. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 30, 174–179. 10.1207/s15324796abm3002_10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United States Conference of Catholic Bishops (USCCB). (2009). Ethical and religious directives for Catholic health care services (5th ed.). Washington, DC: USCCB Publishing; Retrieved from http://www.usccb.org/ (accessed on October 4, 2012). [Google Scholar]

- Winter L., Dennis M. P., Parker B. (2009). Preferences for life-prolonging medical treatments and deference to the will of God. Journal of Religion and Health, 48, 418–430. 10.1007/s10943-008-9205-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winter L., Parks S. M. (2011). Acceptors and rejecters of life-sustaining treatment: Differences in advance care planning characteristics. Journal of Applied Gerontology. Advance online publication. 10.1177/0733464811399079 [Google Scholar]

- Wong P. T., Reker G. T., Gesser G. (1994). Death Attitude Profile–Revised: A multidimensional measure of attitudes toward death. In Neimeyer R. A. (Ed.), Death anxiety handbook: Research, instrumentation and application (pp. 121–128). Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis; [Google Scholar]