A single-incision laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy appears to be an appropriate method to manage gastrointestinal stromal tumors given the nature and location of their lesions.

Keywords: Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor, Single-incision sleeve gastrectomy

Abstract

Background:

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are rare mesenchymal tumors that are located specifically in the gastrointestinal tract, with up to 60% of occurrences in the stomach, 30% in the small intestine, and 10% in the esophagus, colon, and rectum. The annual incidence of GISTs is about 15 cases per million, which in the United States equals 5000 cases per year. In most cases, these tumors are asymptomatic and are found incidentally on computed tomography scan or by endoscopy. Preoperative evaluation is based on location, size, and anatomic features and helps to confirm the diagnosis of the GIST and assess outcomes. Surgical intervention is the gold standard for treatment of nonmetastatic GISTs.

Case Presentation:

We report the case of an 80-year-old man with a gastric mass on the posterior surface of the greater curvature of the stomach at the junction of the gastric antrum and the pylorus, found incidentally on a computed tomography scan. The patient underwent a diagnostic laparoscopy and a single-incision laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy. After histologic evaluation, the resected lesion was determined to be a gastrointestinal stromal tumor.

Conclusion:

A single-incision laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy for the resection of GISTs is a feasible and appropriate method if the lesion is a safe distance from the pylorus and the gastroesophageal junction for gross negative margins to be obtained. Its advantages include decreased pain and a shorter hospital stay compared with other methods.

INTRODUCTION

Gastrointestinal stromal tumors (GISTs) are rare mesenchymal tumors that are located specifically in the gastrointestinal tract. Nearly 60% occur in the stomach, 30% in the small intestine, and 10% in the esophagus, colon, and rectum.1 GISTs can also occur in extraintestinal sites in the abdomen and pelvis, such as the omentum, the retroperitoneum, and the mesentery.2 With the advent of electron microscopy and immunohistochemistry, it has been realized that GIST tumors originate from the interstitial cells of Cajal, which are pluripotent cells. These cells are located throughout the gastrointestinal tract and in and around the myenteric plexus; they regulate intestinal motility.3 As a result of immunohistochemical analyses, GISTs stain positive for c-kit (CD117) and CD34, sometimes for actin, and always negative for desmin and S-100. Malignant GISTs will show active mutations of the c-kit gene, which leads to a constitutively active tyrosine kinase and an increased cell division rate.1 GISTs are most commonly found in men, with the average age of incidence occurring in the fifth decade of life.4 The incidence of GIST is about 15 cases per million annually, which in the United States equals 5000 cases per year.5 In most cases, the tumors are asymptomatic and are found incidentally on computed tomography (CT) scan or at endoscopy. Other manifestations depend on the location of the GIST and can include anemia, bleeding, and abdominal pain. Preoperative evaluation is dependent on location and is necessary to confirm or determine the likelihood of the diagnosis of GIST, the dimensions of the primary lesion, and its possible metastasis.6 Endoscopic ultrasonography evaluation is highly sensitive, specific, and accurate in assessing GISTs when coupled with an ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration.7 Surgical intervention is the gold standard for the treatment of nonmetastatic GISTs. Lymph node metastases are rare with GIST tumors; therefore, lymph node resection is not routinely performed.7 Microscopic margins of resection have not proven to affect the overall survival rate. These aspects of GISTs make them amenable to minimally invasive surgical resection, where obtaining gross margins are feasible and advantageous to the patient in terms of morbidity. The size and location of the GIST determine the type of resection technique applied; the wedge, the sleeve, and partial gastrectomy are the preferred approaches.6 Laparoscopic resection and open resection are equivalent in operative time (160 vs 169 min), estimated blood loss (106 mL vs 129 mL), and perioperative complications. However, the average length of hospital stay for the laparoscopic approach was 3.8 days, whereas the stay for the open resection was approximately 6.2 days.8 The rate of recurrence over a 10-year period was similar for both the laparoscopic and open approaches.9

CASE REPORT

In August 2010, an 80-year-old white man was admitted with a gastric mass that was found incidentally on a CT scan earlier in the year during hypercoagulability testing for a deep vein thrombosis in his right calf in which an inferior vena cava filter was placed. The patient had a follow-up abdominal CT scan in March 2010, which demonstrated a polypoid lesion of the serosal margin of the stomach (Figure 1). Endoscopic ultrasonography was performed in May 2010, and the findings revealed a hypoechoic submucosal nodule on the greater curvature of the stomach at the union of the gastric body and antrum toward the posterior wall, and measuring approximately 18 × 16 mm. No adjacent adenopathy was noted. A fine-needle aspiration was performed at the same time and revealed a spindle-cell lesion, increasing the likelihood of a gastrointestinal stromal tumor. It was decided that a flexible endoscopy was not needed because of the information obtained via CT scan and endoscopic ultrasonography, which showed that gross clear margins could be obtained. The location of the tumor in relation to the gastroesophageal junction and pylorus was also determined.

Figure 1.

Contrast CT scan of the abdomen showing a polypoid lesion along the anterior gastric body.

The patient was subsequently referred to a surgical oncologist for evaluation and treatment. On presentation, the patient was asymptomatic and denied any gastrointestinal complaints, including nausea and/or vomiting. His medical history was significant for hypertension, hyperlipidemia, atrial fibrillation, and a deep vein thrombosis secondary to hypercoagulability. The patient had a surgical history significant only for a hernia repair. His medications were lisinopril, 20 mg twice daily; amlodipine, 5 mg daily; warfarin, 6 mg daily and 7 mg every third day; and simvastatin, half-capsule daily. He was retired, had previously worked as a certified public accountant, denied tobacco and drug use, and drank alcohol occasionally. On examination, he was a well-nourished man with a weight of 94.5 kg, height of 177.8 cm, and a body mass index (BMI) of 29.9. His vitals signs were within normal limits, and his physical examination was negative except for an irregular heart rhythm. It was recommended that the patient undergo a diagnostic laparoscopy with possible gastrectomy. The patient consented for a single-incision laparoscopic approach with a possible conversion to open resection if needed.

Surgical Therapy

The patient was placed in the supine position on the operating table, and general anesthesia was administered. His abdomen and pelvis were prepped and draped for diagnostic laparoscopy. A Hasson-type opening technique was performed with a 2.5-cm midline incision above the umbilicus. Electrocautery was used to carry the incision downward into the abdomen. A 2.5-cm incision was made in the fascia, and a GelPOINT applied single port (Applied Medical, Rancho Santa Margarita, CA) was placed into the abdomen via a single incision. Multiple ports were placed through the GelPOINT port to allow for a single-incision approach (Figure 2). On exploration of the abdomen, small adhesions were found, and a laparoscopic lysis of the adhesions was performed. The patient was then placed in the reverse Trendelenburg position, and a laparoscopic LigaSure device (Covidien, Boulder, Colorado, USA) was used to divide the greater omentum between the colon and the greater curvature of the stomach. Care was taken not to injure the right gastroepiploic artery. The stomach was lifted near the pylorus, and a 2- to 3-cm exophytic lesion in the posterior portion of the greater curvature was found (Figure 3). On discovery of the lesion, it was determined that a partial gastrectomy would be feasible and gross margins would be obtained. A sleeve gastrectomy was performed by stapling across the greater curvature to excise the mass and a portion of the stomach (Figure 4). The right gastroepiploic artery along the greater curvature was then divided along that area to allow the formation of a gastric sleeve to fully excise the lesion with margins. An Endo GIA stapler (Covidien) with a green load of Peri-Strips (Synovis, Deerfield, Illinois, USA) was fired at least 3 times to ensure adequate stapling and resection. The specimen was given to the pathology department, and negative gross margins were confirmed. Irrigation and a check for hemostasis were performed. The port was removed, and the fascia and skin were closed (Figure 5). Pathologic findings confirmed the diagnosis of a gastrointestinal stromal tumor. Postoperatively, the patient tolerated the procedure without complications or complaints and had an uneventful hospital course. On postoperative day 0, he received nothing by mouth, on postoperative day 1 he was begun on clear liquids, and he was discharged home on postoperative day 3. At the 3-week follow-up appointment, the patient had no complaints of pain or gastrointestinal irregularity. His incision healed with no signs of infection or wound breakdown.

Figure 2.

Single-incision GelPOINT port setup.

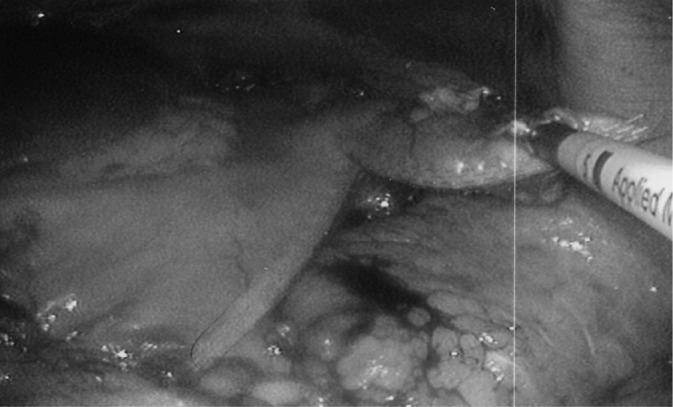

Figure 3.

Exposure of the exophytic lesion on the greater curvature of the stomach.

Figure 4.

Sleeve gastrectomy to excise the lesion with an Endo GIA stapler.

Figure 5.

Single-port incision site located midline 2.5 cm above the umbilicus after removal of the port.

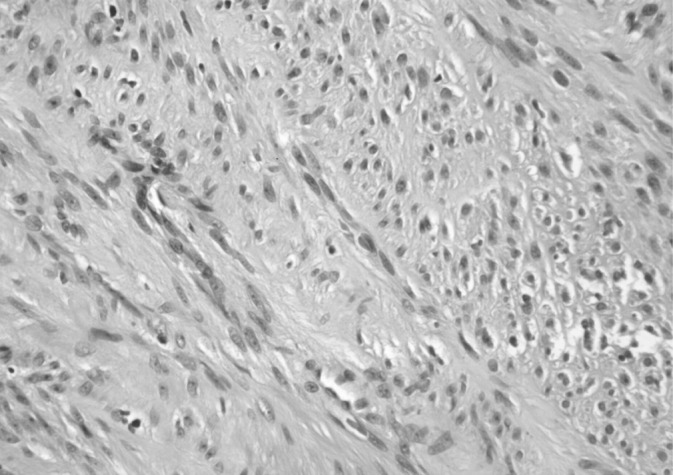

Histopathologic Findings

The tumor was 3.5 cm at its greatest dimension and had a white-tan fleshy cut surface without areas of hemorrhage or necrosis. Microscopically, the tumor consisted of a cellular proliferation of spindled cells with eosinophilic cytoplasm arranged in intersecting fascicles without pleomorphism. The mitotic rate was low, with one mitotic cell division in 50 high-power fields. Ki-67 confirmed the low proliferation of the tumor. Mucosal invasion was not identified. Immunohistochemistry analysis performed on the tumor was positive for C-Kit (CD117), vimentin, and CD34, and was negative for MAK-6, desmin, and actin (Figures 6–10).

Figure 6.

Gastrointestinal stromal tumor with hematoxylin and eosin staining (original magnification ×40).

Figure 7.

GIST with c-kit (CD117) antibody staining (brown) (original magnification ×20).

Figure 8.

GIST with CD34 staining (original magnification ×40).

Figure 9.

GIST with Ki67 staining (original magnification ×40).

Figure 10.

GIST with staining for vimentin (original magnification ×40).

DISCUSSION

GIST tumors are rare mesenchymal tumors that originate from the interstitial cells of Cajal. Most of these tumors are located in the stomach and can be further assessed and confirmed by endoscopic ultrasonography and ultrasound-guided fine-needle aspiration. Immunohistochemistry staining of GIST tumors are positive for c-kit (up to 95%) and are negative for desmin and S-100. The most common method of treatment is surgical resection. Laparoscopic resection is ideal for GIST tumors because of their low incidence of metastasis, thus less need for lymph node resection, and the decreased need for microscopic margins.

Our patient was an 80-year-old previously healthy man whose submucosal gastric mass was incidentally discovered on CT scan upon admission for a workup for deep vein thrombosis and inferior vena cava filter placement. The mass was confirmed to be a GIST upon pathologic testing. The patient was asymptomatic for his GIST and denied any GI symptoms. His complete blood count laboratory results showed hemoglobin and hematocrit values within normal limits and a BMI of 29.9.

A single-incision laparoscopic diagnostic exploration was the surgical approach selected for this patient. Findings included a 2- to 3-cm exophytic lesion on the posterior aspect of the greater curvature of the stomach near the junction between the pylorus and the gastric body. A sleeve gastrectomy was performed to resect the lesion with gross negative margins. Peri-Strips (Covidien) were used to reinforce the staple line because of the patient's long-term anticoagulation therapy to treat his atrial fibrillation and hypercoagulability. Previous studies have demonstrated reduced bleeding and reductions in intraoperative complications in certain patients.10

Minimally invasive sleeve gastrectomy operations are most commonly performed for bariatric surgery. Indications include a BMI >60 kg/m2, severe comorbidities (eg, poor cardiorespiratory status, cirrhosis), arthritis with a dependence on nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medication, and a conversion of a failed laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Sleeve gastrectomies have an advantage over other bariatric procedures, such as the Roux-en-Y gastric bypass, because they do not lead to a risk of iron deficiency anemia, calcium malabsorption, marginal ulceration, or internal herniation.11 A laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy was feasible for this patient because of the location of the lesion, the size of the lesion, and its distance from the gastroesophageal junction and the pylorus. Furthermore, this lesion was on the posterior aspect of the greater curvature of the stomach, and there was no evidence of lymphadenopathy or a need for a nodal biopsy. A noted advantage of performing a single-incision laparoscopic sleeve gastrectomy versus its conventional multiport counterpart is a decrease in postoperative pain because there is only one incision site versus 5 or 7 sites with conventional sleeve gastrectomy laparoscopy, faster recovery, and a decreased length of hospital stay.11

Contributor Information

Evan Ong, Department of Surgery, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA..

Andrew I. Abrams, Department of Surgery, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA..

Elizabeth Lee, Department of Surgery, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA..

Carol Jones, Department of Surgery, University of Arizona, Tucson, AZ, USA..

References:

- 1. Miettinen M, Sarlomo-Rikala M, Lasota J. Gastrointestinal stromal tumor: recent advances in understanding of their biology. Hum Pathol. 1999;30(10):1213–1220 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. DeMatteo RP, Lewis JJ, Leung D, et al. Two hundred gastrointestinal stromal tumors: recurrence patterns and prognostic factors for survival. Ann Surg. 2000;231:51–58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kindblom LG, Remotti HE, Aldenborg F, et al. Gastrointestinal pacemaker cell tumor (GIPACT): gastrointestinal stromal tumor show phenotypic characteristics of the interstitial cells of Cajal. Am J Pathol. 1998;152(5):1259–1269 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Kindblom LG, Meis-Kindblom J, Bümming P, et al. Incidence, prevalence, phenotype and biologic spectrum of gastrointestinal stromal cell tumors (GIST)—a population-based study of 600 cases [abstract]. Ann Oncol. 2002;13(Suppl 5):15711863097 [Google Scholar]

- 5. Dholakia C. Minimally invasive resection of gastrointestinal stromal tumors. Surg Clin North Am. 2008;88(5):1009–1918 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Akahosi K, Sumida Y, Matsui N, et al. Preoperative diagnosis of gastrointestinal stromal tumor by endoscopic ultrasound guided fine needle aspiration. World J Gastroenterol 2007;13(14):2077–2082 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Matthews BD, Walsh RM, Kercher KW, et al. Laparoscopic vs. open resection of gastric stromal tumors. Surg Endosc. 2002;16:803–807 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Nishimura J, Nakajima K, Omori T, et al. Surgical strategy for gastric gastrointestinal tumors: laparoscopic vs. open resection. Surg Endosc. 2007;21(6):875–878 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Frantzides CT, Carlson MA. Atlas of Minimally Invasive Surgery. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier; 2009 [Google Scholar]

- 10. Angrisani L, Lorenzo M, Borrelli V, Ciannella M, Bassi UA, Scarano P. The use of bovine pericardial strips on linear stapler to reduce extraluminal bleeding during laparoscopic gastric bypass: prospective randomized clinical trial. Obes Surg. 2004;14(9):1198–1202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Angrisani L, Cutolo PP, Buchwald JN, et al. Laparoscopic reinforced sleeve gastrectomy: early results and complications. Obes Surg. 2011;21(6):783–793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]