This report describes the occurrence of a cecal bascule (cecal volvulus) following laparoscopic ventral hernia repair and notes that the consequences of this complication can be serious.

Keywords: Cecal bascule, Cecal volvulus, Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair

Abstract

Introduction:

We present a case of a cecal bascule, a rare type of cecal volvulus, as a complication of a laparoscopic ventral hernia repair.

Case Description:

A 73-y-old male with a ventral hernia underwent an uneventful elective laparoscopic repair. He developed an acute abdomen on postoperative day 6, and imaging demonstrated a cecal bascule. Exploratory laparotomy revealed a cecal bascule with an ischemic and perforated cecum, and a right hemicolectomy was performed.

Discussion:

Laparoscopic tension-free ventral hernia repairs have become more common, especially for obese patients. We discuss some risk factors that can predispose a patient to having a cecal volvulus postoperatively. Although cecal volvulus is a very rare complication after laparoscopic surgery, it can result in serious complications.

INTRODUCTION

A laparoscopic approach for ventral hernia repairs was first described in 1992 by LeBlanc and Booth and has quickly become a popular technique. Numerous studies have shown that this minimally invasive technique leads to a lower rate of postoperative complications and morbidity.1,2 However, laparoscopic techniques are not without their own complications. As the number of intraabdominal laparoscopic procedures increase, rare and serious complications have begun to be reported. Intestinal volvulus is one such rare complication, with a handful of cases reported.3–6 We present the first reported case known of a postoperative complication of a cecal bascule and perforation after a routine, uneventful laparoscopic ventral hernia repair (LVHR).

CASE REPORT

A 73-y-old male underwent an elective LVHR with mesh placement for a symptomatic reducible ventral hernia. His past medical history was significant for obesity with a body mass index of 30, coronary artery disease with coronary artery stent placement, and hypertension. His only previous abdominal surgery was an open appendectomy. He had been evaluated multiple times in the emergency department in the past year for episodes of pain localized to his periumbilical region with nausea and vomiting. On physical examination, he was found to be obese with tenderness around the umbilicus, with a palpable mass that was believed to be a ventral hernia. Computed tomography (CT) scan confirmed the presence of a ventral hernia containing small bowel and fat with no evidence of strangulation. The decision was made to complete the ventral hernia repair using a laparoscopic approach.

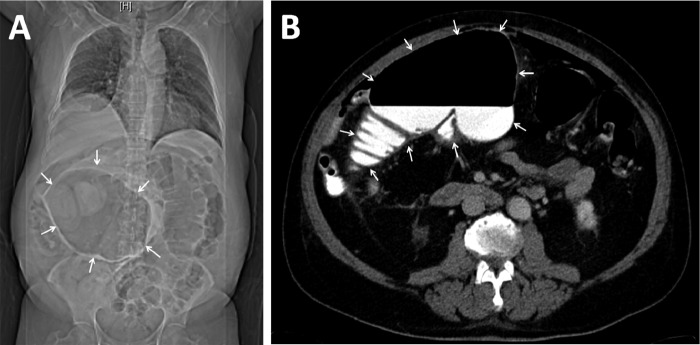

The procedure was completed with the placement of a 12-cm polyester composite mesh that was sutured to the anterior abdominal wall and then tacked in a double-crown fashion. No adhesions were observed, the bowel was minimally manipulated, and the cecum was visualized and appeared unremarkable. The operation was uneventful and took 70 min, and the patient was admitted for pain control. His early postoperative course was noncomplicated, and he began to tolerate a diet. On postoperative day 4, he began to complain of some abdominal pain and distension. On postoperative day 6, he became febrile and had a significant leukocytosis. CT scan revealed a significant pneumoperitoneum and an acutely distended cecum, which appeared to have twisted cephalad to itself in the shape of a cecal bascule (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Whole-body CT on postoperative day 6, depicting a significant pneumoperitoneum, dilated colon, and cecal bascule. (A) Scout view demonstrating a distended cecum, which has been displaced superiorly. (B) Dilated cecum with air-fluid level.

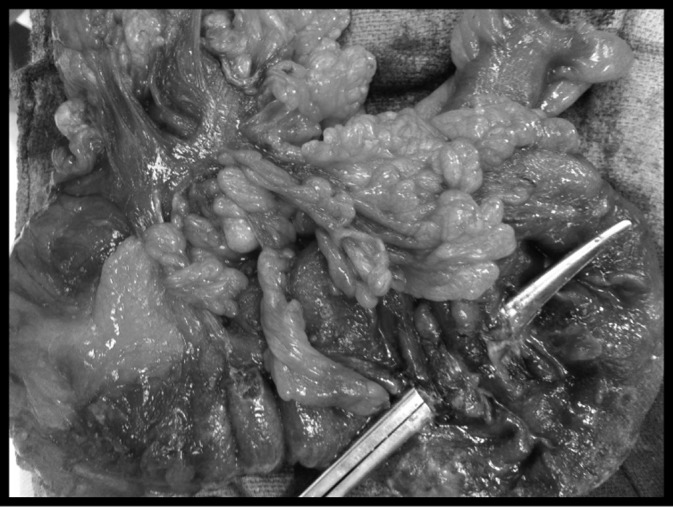

The patient underwent an emergent exploratory laparotomy, and purulent peritonitis was found. The cecum was largely distended, and a large patch of the anterior wall was ischemic, gangrenous, friable on manipulation, and had multiple perforations. There was a thick adhesive band connecting the cecum to the transverse colon, which displaced the cecum anteriorly and superiorly to form a cecal bascule (Figure 2). The colon was also distended, with significant necrosis extending up the ascending colon. A right hemicolectomy was performed with a side-to-side anastomosis. The fascia was closed, but the wound was left open and packed.

Figure 2.

Resected specimen after completion of right hemicolectomy with cecal wall opened.

On postoperative day 1, the patient became severely septic and hypotensive and was reexplored emergently. The ileocolic anastomosis appeared gross intact, but as a result of the patient's severe sepsis and hemodynamic instability, the anastomosis was excised and an end ileostomy and transverse colon mucous fistula were placed. The patient's postoperative course included a long stay in the surgical intensive care unit, but he progressed well and was discharged from the hospital on postoperative day 75 from his original ventral hernia repair.

DISCUSSION

A cecal volvulus is usually caused by axial torsion of the cecum around its mesentery, leading to a closed loop obstruction. A cecal bascule is a rare form of cecal volvulus where the cecum folds anteriorly and superiorly onto itself or the ascending colon without any torsion.7 For a cecal volvulus to occur, there must be a redundant cecum or some form of anatomic predisposition that allows the cecum, terminal ileum, and ascending colon to have increased mobility.3,7–9 This cecal mobility can occur as a result of defective retroperitoneal fixation of the cecum secondary to incomplete intestinal rotation during the final stages of embryogenesis. Based on autopsies, approximately 11% of adults have the cecal mobility to form a volvulus and 25% of adults have the mobility to form a bascule.10,11 However, cecal volvulus is actually a very rare occurrence, with an incidence of 2.8 to 7.1 per million people per year and accounts for 1% to 1.5% of adult intestinal obstructions.7 Additionally, only 10% to 15% of cecal valvulae are cecal bascules.8,12 The presentation of cecal volvulus can be quite variable, ranging from a self-limited, intermittent abdominal pain to acute pain with peritonitis secondary to gangrenous bowel or perforation.7,13

Several clinic series have identified previous abdominal surgery as a risk factor, with 23% to 53% of patients developing cecal volvulus having had a previous abdominal surgery.3,7 It has been theorized that postoperative adhesions may play a role in forming a point of fixation allowing for rotation of the colon and small bowel.8 Other factors that have been postulated include chronic constipation, adynamic ileus, distal colonic obstruction, late-term pregnancy, and high fiber intake.8

Given the morbidity and recurrence rates of open ventral hernia repairs, especially in obese patients, the decision was made to complete the repair laparoscopically, which has been shown to decrease the morbidity and rate of recurrence. A number of cases of intestinal volvulus have been reported after a laparoscopic abdominal surgery. However, this is the first report after an LVHR and only the second case of a cecal bascule after laparosopic surgery. Because of the rarity of cecal volvulus as a postoperative complication, there have been no widely accepted recommendations about systemic assessment of the omentum and viscera upon completion of a laparoscopic surgery. In our case, the omentum and peritoneal cavity was inspected for any bleeding that needed to be controlled at the end of the surgery, but no abnormalities were noted. In addition, aside from the fibrous band attached to the cecum, there were minimal adhesions in the abdomen that could have predisposed the patient to forming an intestinal volvulus of any kind.

A number of factors played a role in the formation of the bascule and perforation in our patient who required emergent surgery. He had undergone a previous abdominal surgery (an open appendectomy) with the possibility of the formation of adhesions creating a point of fixation. As discussed earlier, this previous abdominal surgery predisposed him to having a volvulus.3,7 Further, previous appendectomy could increase cecal mobility, which is a requirement for the formation of a volvulus. The dissection during the appendectomy could have freed peritoneal attachments leading to mobilization of part of the ascending colon and terminal ileum, allowing the cecum the increased mobility necessary to form a bascule. Routine inspection of the omentum at the end of the uneventful LVHR did not show any evidence of abnormalities, and no adhesions were visualized. However, during the exploratory laparotomy to address the cecal bascule, a thick adhesive band was found connecting the cecum to the transverse colon. This band likely acted as a point of fixation, allowing the formation of the bascule. This band was most likely a result of the previous appendectomy and had been present for years. However, the patient did not form a cecal bascule until after the ventral hernia repair. Postoperatively, the patient developed an ileus, which has been postulated to be a risk factor for the formation of cecal bascule because of the resulting colonic distension. This distension and the history of cardiovascular disease likely contributed to the cecal ischemia and resultant perforation.

CONCLUSION

We present the first reported postoperative complication of cecal bascule, a rare form of cecal volvulus, after LVHR. Because minimally invasive techniques are used more frequently for ventral hernia repairs, it is important to keep in mind this rare complication of intestinal volvulus. Although this complication is very rare, the consequences can be quite serious, as they were for our patient. It is important to keep this complication in mind after laparoscopic surgery, especially if a routine postoperative course is not noted.

Contributor Information

Joseph Kim, Mount Sinai Medical Center, NY, New York, USA..

Scott Nguyen, Mount Sinai Medical Center, NY, New York, USA..

Parkson Leung, Mount Sinai Medical Center, NY, New York, USA..

Celia Divino, Mount Sinai Medical Center, NY, New York, USA..

References:

- 1. Heniford BT, Park A, Ramshaw BJ, Voeller G. Laparoscopic repair of ventral hernias: nine years' experience with 850 consecutive hernias. Ann Surg. 2003;238:391–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Novitsky YW, Cobb WS, Kercher KW, et al. Laparoscopic ventral hernia repair in obese patients: a new standard of care. Arch Surg. 2006;141:57–61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ferguson L, Higgs Z, Brown S, McCarter D, McKay C. Intestinal volvulus following laparoscopic surgery: a literature review and case report. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2008;18:405–410 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. McIntosh SA, Ravichandran D, Wilmink AB, Baker A, Purushotham AD. Cecal volvulus occurring after laparoscopic appendectomy. JSLS. 2001;5:317–318 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bariol SV, McEwen HJ. Cecal volvulus after laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Aust N Z J Surg. 1999;69:79–80 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ulloa SA, Ramirez LO, Ortiz VN. Cecal volvulus after laparoscopic liver biopsy. Bol Asoc Med P R. 1997;89:195–196 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Consorti ET, Liu TH. Diagnosis and treatment of caecal volvulus. Postgrad Med J. 2005;81:772–776 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rabinovici R, Simansky DA, Kaplan O, Mavor E, Manny J. Cecal volvulus. Dis Colon Rectum. 1990;33:765–769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Gupta S, Gupta SK. Acute cecal volvulus: report of 22 cases and review of literature. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1993;25:380–384 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wolfer JA, Beaton LE, Anson BJ. Volvulus of the cecum. Anatomical factors in its etiology: report of case. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1942;74:882–894 [Google Scholar]

- 11. Donhauser JL, Atwell S. Volvulus of the caecum. Arch Surg. 1949;58:129–148 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Madiba TE, Thomson SR. The management of cecal volvulus. Dis Colon Rectum. 2002;45:264–267 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gupta S, Gupta SK. Acute cecal volvulus: report of 22 cases and review of literature. Ital J Gastroenterol. 1993;25:380–384 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]