Malignant hyperthermia is a rare, but potentially fatal, problem. Bariatric surgeons and anesthesiologists need be aware of the early signs of this complication.

Keywords: Malignant hyperthermia, Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding, End-tidal carbon dioxide, Desflurane

Abstract

Background:

We report a rare case of malignant hyperthermia during laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding.

Case Description:

A 32-y-old female with no previous history of adverse reaction to general anesthesia underwent laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding. Intraoperative monitoring revealed a sharp increase in end-tidal carbon dioxide, autonomic instability, and metabolic and respiratory acidosis, along with other metabolic and biochemical derangements. She was diagnosed with malignant hyperthermia. Desflurane, the anesthetic agent was discontinued, and the patient was started on intravenous dantrolene.

Results:

The surgery was completed, and the patient was brought to the surgical intensive care unit for continued postoperative care. She developed muscle weakness and phlebitis that resolved prior to discharge.

Conclusion:

Prompt diagnosis and treatment of malignant hyperthermia leads to favorable clinical outcome. This clinical entity can occur in the bariatric population with the widely used desflurane. Bariatric surgeons and anesthesiologists alike must be aware of the early clinical signs of this rare, yet potentially fatal, complication.

INTRODUCTION

Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding (LAGB) is the least-invasive form of bariatric surgery. It is safe and effective.1–6 Moreover, it is increasingly being performed on an outpatient basis. Malignant hyperthermia (MH) is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication that can occur from administration of certain general anesthetics.7–10 Its incidence ranges from 1:5000 to 1:50,000 to 100,000 administrations of general anesthetics.8 Since its introduction as an anesthetic agent, desflurane has been classified as a weak trigger of MH.11 Its widespread use has changed the clinical presentation of MH.11 Tachycardia and late onset presentations are some features of MH induced by desflurane.11,12 Nevertheless, its facilitation of rapid postoperative recovery, particularly in obese patients, makes it an ideal choice during bariatric surgery.13–15

Here we report a case of MH during LAGB, with desflurane as the maintenance anesthetic agent. Review of the literature reveals one publication in which a case of MH was described as a complication during LAGB.4 The utilization of an anesthesiology team familiar with the biochemical and metabolic derangements associated with MH will permit timely diagnosis and treatment of the disorder, thus leading to better outcomes. Given the potential fatal outcome of MH, treatment with dantrolene should be initiated once the diagnosis is suspected.16

CASE REPORT

A 32-y old, 96 kg female with a body mass index of 41 kg/m2, was evaluated at our institution for bariatric consultation. Her past medical history included asthma, hyperlipidemia, and infertility. Her past surgical history consisted of knee arthroscopy and dilation and curettage; both were performed while she was under general anesthesia, uneventfully. Preoperative evaluation revealed no personal history or family history of adverse reaction to anesthetics.

The patient underwent LAGB. After adequate preoxygenation, general anesthesia was induced with a combination of propofol (200 mg), fentanyl (100mcg), and rocuronium (50 mg). The trachea was intubated and general anesthesia was maintained using a combination of oxygen and air (1:1), desflurane (5% to 6%), and fentanyl, as needed.

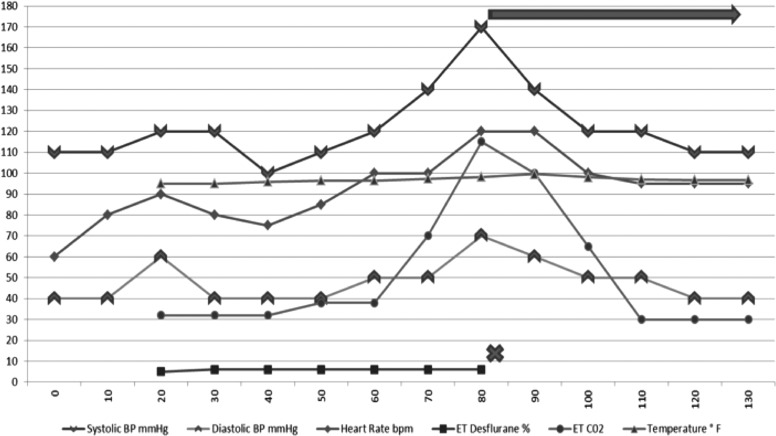

Towards the end of the laparoscopic portion of the operation (35 min from induction of general anesthetic), she experienced rapid physiologic changes consistent with MH. Her end-tidal carbon dioxide (ETCO2) increased from 32 mm Hg to 80 mm Hg within 5 min, and peaked at 115 mm Hg. The patient's heart rate increased from 70 to 80 beats per minute to sinus tachycardia at 129 beats per minute. Her blood pressure trended up from an average 110/50 mm to 162/60 mm Hg, and her temperature increased from 35.8°C to 37.5°C. Arterial blood gas was consistent with mixed acidosis; her arterial blood gas demonstrated a pH of 7.15, partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PCO2) of 49 mm Hg, and bicarbonate (HCO3-) of 17.3 mmol/L. Her urine was straw-colored with a red tinge. The volatile anesthetic was immediately discontinued, and 175 mg of intravenous dantrolene was administered; furthermore, minute volume and the fraction of inspired oxygen (FiO2) were increased. She immediately responded to the treatment. Her ETCO2 subsequently decreased to 31 mm Hg, and her pulse (129 to mid 80s), temperature (37.5°C to 36.0°C), and blood pressure returned to her baseline of 115/50 mm Hg (Figure 1). The surgery was completed uneventfully, with a total operative time of 63 min.

Figure 1.

Intraoperative anesthetic course. Anesthesia induction occurred at 20 min. At 80 min (60 min after induction) MH was diagnosed, desflurane was discontinued and dantrolene was started. The patient responded immediately to treatment, and reversal of metabolic derangements was observed.

Biochemically, the patient had elevated creatine kinase MB (CKMB) and creatine kinase of 84.2ng/mL and 22233u/L, respectively, which peaked at 91.1ng/mL and 49220u/L on the first postoperative day 1. Postoperative management with intravenous dantrolene (1 mg/kg every 6 h) was continued for an additional 36 h. The patient remained hemodynamically stable. Her acidosis resolved, and the remainder of her metabolic and biochemical derangements progressively improved to normal values. She developed muscle weakness, which improved with physical therapy. She also developed phlebitis of her forearm, where dantrolene was infused. The phlebitis was treated conservatively with arm elevation and warm compresses. The patient was discharged home on postoperative day 8 in good and stable condition.

DISCUSSION

We present a rare, but potentially life threatening, intraoperative complication of bariatric surgery. The patient's rapid and severe metabolic and biochemical derangements and their subsequent rapid reversal with administration of dantrolene are strongly suggestive of malignant hyperthermia.17,18 Desflurane will likely remain in widespread use in the bariatric population given its quick offset and effectiveness,13–15 and its use is justified because it is a weak trigger of MH; moreover, other inhalation anesthetics, such as halothane, sevoflurane, isoflurane, and enflurane, are all potential triggers of MH. Additionally, succinylcholine, the depolarizing neuromuscular blocking agent, has been reported to be itself a trigger of MH.11,12,19 Nevertheless, it is important to note that MH can be triggered up to 6 h after general anesthesia induction when desflurane is used.12 In view of increasing same-day discharge after LAGB, particular emphasis should be placed on the potential for delayed presentation of this complication of general anesthesia and the potential severe adverse consequences that can occur if MH is not recognized and treated promptly.

The potentially fatal nature of MH mandates treatment as soon the diagnosis is suspected. The principles of treatment of MH start with immediate discontinuation of the trigger agent. The patient is then hyperventilated to decrease the ETCO2, which is then followed by administration of dantrolene. The initial dose of dantrolene is 2.5 mg/kg, and this dose is repeated as needed; the dose can be titrated up to 10 mg/kg until resolution of the patient's tachycardia and hypercarbia.18 Dantrolene is then continued at 1 mg/kg every 4 to 8 h for 24 to 48 h. While dantrolene is being infused, hyperthermia must be controlled by all means available to the treating physician. Rapid cooling continues until a core body temperature of 38.5°C is reached. Continued care for the next 36 h to 48 h is then performed in the intensive care unit, where the patient is monitored and treated for arrhythmias, biochemical disturbances and metabolic disturbances. Urine output is increased to 2 mL/kg/hour with administration of fluids, mannitol, and furosemide as needed.8 Once the patient is stabilized with documented improvement of metabolic and biochemical derangements, attention to possible complications of dantrolene and ways to curtail their progression are warranted.

Our patient developed muscle weakness and phlebitis, the 2 most common complications of dantrolene administration.16 Administration of dantrolene as well as aggressive fluid resuscitation was discontinued after 36 h once she demonstrated objective evidence of improvement. Although these maneuvers may have decreased the potential complications from dantrolene, continued administration of the drug through a central line could have decreased the chance of phlebitis development.16

CONCLUSION

Malignant hyperthermia is a very rare phenomenon, but bariatric surgeons, anesthesiologists, and all medical personnel involved in perioperative care of bariatric patients should be aware of early signs of MH. Early recognition and prompt treatment reduce the morbidity and potential mortality of this serious complication.

Contributor Information

Josue Chery, Department of Surgery, NY Methodist Hospital, Brooklyn, NY, USA..

Chiba Shintaro, Department of Surgery, NY Methodist Hospital, Brooklyn, NY, USA..

Ambibola Pratt, Department of Surgery, NY Methodist Hospital, Brooklyn, NY, USA..

Ronell Kirkley, Department of Anesthesia, NY Methodist Hospital, Brooklyn, NY, USA..

Barbara Hearne, Department of Anesthesia, NY Methodist Hospital, Brooklyn, NY, USA..

Andrew Beyzman, Department of Anesthesia, NY Methodist Hospital, Brooklyn, NY, USA..

Piotr Gorecki, Department of Surgery, NY Methodist Hospital, Brooklyn, NY, USA..

References:

- 1. Chapman AE, Kiroff G, Game P, et al. Laparoscopic adjustable gastric banding in the treatment of obesity: a systematic literature review. Surgery. 2004;135(3):326–351 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Parikh MS, Shen R, Weiner M, Siegel N, Ren CJ. Laparoscopic bariatric surgery in super-obese patients (BMI>50) is safe and effective: a review of 332 patients. Obes Surg. 2005;15(6):858–863 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. O'Brien PE, Dixon JB. Lap-band: outcomes and results. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2003;13(4):265–270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Carelli AM, Youn HA, Kurian MS, Ren CJ, Fielding GA. Safety of the laparoscopic adjusted gastric band: 7-year data from a U.S. center of excellence. Surg Endosc. 2010;24(8):1819–1823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ren CJ, Horgan S, Ponce J. US experience with the LAP-BAND system. Am J Surg. 2002;184(6B):46S–50S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ren CJ, Weiner M, Allen JW. Favorable early results of gastric banding for morbid obesity: the American experience. Surg Endos. 2004;18(3):543–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Denborough M. Malignant hyperthermia. Lancet. 1998;352(9134):1131–1136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rosenberg H, Davis M, James D, Pollock N, Stowell K. Malignant hyperthermia. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2007;2:21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Simon HB. Hyperthermia. N Engl J Med. 1993;329(7):483–487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Litman RS, Rosenberg H. Malignant hyperthermia-associated diseases: state of the art uncertainty. Anesth Analg. 2009;109(4):1004–1005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Wedel DJ, Gammel SA, Milde JH, Iaizzo PA. Delayed onset of malignant hyperthermia induced by isoflurane and desflurane compared with halothane in susceptible swine. Anesthesiology. 1993;78(6):1138–1144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Papadimos TJ, Almasri M, Padgett JC, Rush JE. A suspected case of delayed onset malignant hyperthermia with desflurane anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 2004;98(2):548–549 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McKay RE, Malhotra A, Cakmakkaya OS, Hall KT, McKay WR, Apfel CC. Effect of increased body mass index and anesthetic duration on recovery of protective airway reflexes after sevoflurane vs. desflurane. Br J Anesth. 2010;104(2):175–182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. La Colla L, Albertin A, La Colla G, Mangano A. Faster wash-out and recovery for desflurane vs. sevoflurane in morbidly obese patients when no premedication is used. Br J Anesth. 2007;99(3):353–358 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vallejo MC, Sah N, Phelps AL, O'Donnell J, Romeo RC. Desflurane versus sevoflurane for laparoscopic gastroplasty in morbidly obese patients. J Clin Anesth. 2007;19(1):3–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Brandom BW, Larach MG, Chen MS, Young MC. Complications associated with the administration of dantrolene 1987 to 2006: a report from the North American Hyperthermia Registry of the Malignant Hyperthermia Association of the United States. Anesth Analg. 2011;112(5):1115–1123 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Rosero EB, Adesanya AO, Timaran CH, Joshi GP. Trends and outcomes of malignant hyperthermia in the United States, 2000 to 2005. Anesthesiology. 2009;110(1):89–94 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Larach MG, Gronert GA, Allen GC, Brandom BW, Lehman EB. Clinical presentation, treatment, and complications of malignant hyperthermia in North America from 1987 to 2006. Anesth Analg. 2010;110(2):498–507 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Hopkins PM. Malignant hyperthermia: pharmacology of triggering. Br J Anaesth. 2011;107(1):48–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]