Abstract

Background

Some veterans, and especially those with mental disorders, have difficulty reintegrating into the civilian workforce.

Purpose

The objectives of this study were to describe the scope of the existing literature on mental disorders and unemployment and to identify factors potentially associated with reintegration of workers with mental disorders into the workforce.

Data Sources

The following databases were searched from their respective inception dates: MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cumulative Index Nursing Allied Health (CINAHL), and PsycINFO.

Study Selection

In-scope studies had quantitative measures of employment and study populations with well-described mental disorders (eg, anxiety, depression, posttraumatic stress disorder, substance-use disorders).

Data Extraction

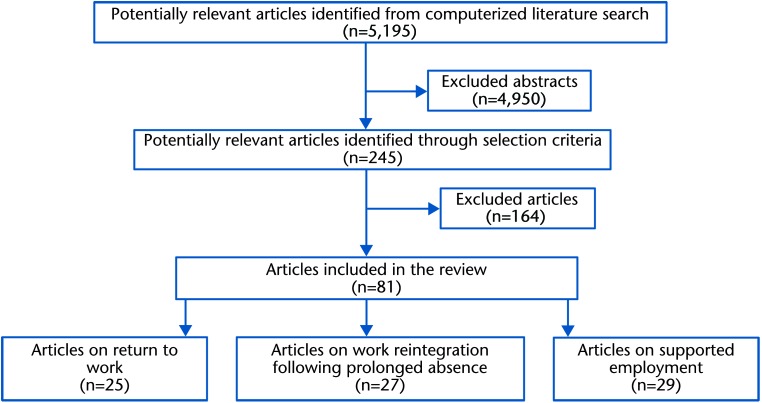

A systematic and comprehensive search of the relevant published literature up to July 2009 was conducted that identified a total of 5,195 articles. From that list, 81 in-scope studies were identified. An update to July 2012 identified 1,267 new articles, resulting in an additional 16 in-scope articles.

Data Synthesis

Three major categories emerged from the in-scope articles: return to work, supported employment, and reintegration. The literature on return to work and supported employment is well summarized by existing reviews. The reintegration literature included 32 in-scope articles; only 10 of these were conducted in populations of veterans.

Limitations

Studies of reintegration to work were not similar enough to synthesize, and it was inappropriate to pool results for this category of literature.

Conclusions

Comprehensive literature review found limited knowledge about how to integrate people with mental disorders into a new workplace after a prolonged absence (>1 year). Even more limited knowledge was found for veterans. The results informed the next steps for our research team to enhance successful reintegration of veterans with mental disorders into the civilian workplace.

There is a paucity of relevant research into mental health and work, in which work spans a spectrum from keeping the workforce well and at work to returning or introducing people to work.1 Our research team was established to contribute to this area by building expertise in civilian workplace reintegration of veterans with mental disorders.

Canadian veterans are former Canadian Forces personnel with as little as 1 day of service to more than 30 years of service. They leave the military workforce for a variety of reasons and subsequently many seek employment in a new civilian workplace after release from the military. Some veterans may seek a civilian job for the first time, whereas others may have had considerable prior civilian job experience. The transition from the military to civilian workplace can be difficult for some veterans.2 Reintegration difficulties are compounded for those with a mental health problem, as observed in Britain3 and the United States.4,5 In Canada, 24% of recently released veterans reported a mental health condition.2 Many of these veterans were released after service in the protracted conflicts in southwest Asia.

The target population that our team will study is a subset of Canadian veterans—those with a chronic mental disorder who are patients at Operational Stress Injury (OSI) Clinics across Canada. These clinics treat patients with a broad range of mental health problems, including anxiety disorders (eg, posttraumatic stress disorder [PTSD]) and mood disorders (eg, major depressive disorder) that may result from military operational duties. Each clinic has an interdisciplinary team that includes psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, and social workers. Our research team also is multidisciplinary, with a range of expertise that includes psychology, psychiatry, epidemiology, military and veteran health, occupational therapy, and rehabilitation.

For many veterans, a successful transition to civilian life includes success in the civilian workplace. Our team is interested in the best strategies and interventions to maximize work for those with a mental disorder. We began by looking for evidence of effective programs that will enhance successful reintegration of veterans with mental disorders into the civilian workplace. The objectives of this systematic literature review were to describe the scope of the existing literature on mental disorders and unemployment and to identify factors potentially associated with reintegration of workers with mental disorders into the workforce.

Method

Data Searches and Sources

The objectives of the scoping literature review were used to design the search strategy framed by the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome) format. The inclusion terms for the computerized literature search by the 4 PICO categories were: (1) study population had a mental health disorder, particularly depression, PTSD, anxiety, substance-use disorder, with or without comorbid conditions; (2) intervention described by the study, with no criteria specified; (3) study method was an observational study or experimental study, such as a randomized controlled trial (RCT); and (4) study outcomes included a measure of resumption of employment. Within each category, search terms were joined by an “OR” Boolean operator. Only articles identified by “AND” joining the categories were kept for review.

The computerized search of the literature was carried out in July 2009 by the Institute for Work and Health, Toronto, Canada, and updated in 2012 as described below. The search included articles in English and French. The following databases were searched from their respective inception dates: MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL), and PsycINFO. Search terms included a number of database-specific, controlled vocabulary terms (eg, MeSH terms in MEDLINE) and additional text words such as the work terminology based on prior literature reviews by the institute. The inclusive search strategy identified a total of 5,195 articles to July 2009 after duplicates were removed.*

Study Selection

Abstracts of the 5,195 articles were initially screened by 2 reviewers: a PhD candidate in mental health epidemiology and an occupational therapist with an MEd in applied psychology and a PhD in community mental health. On the basis of the contents of the abstract, the reviewers excluded articles with vague measures of mental disorders or employment or articles with a case study method. To ensure consistency, the reviewers initially duplicated their reading of 25 abstracts, resulting in substantial agreement (κ=0.71) to keep or reject the paper for postscreening review. The review of abstracts resulted in acquisition of 245 articles.

Each of the 245 potentially relevant articles was independently reviewed by at least 2 members of the 9 coinvestigators on the research team. With the use of the full text of the article, each person determined whether the article should be excluded for poorly described measures of mental disorders or employment or case study method (the same exclusion criteria applied to the abstracts). In-scope studies (as determined by at least 1 reader) included quantitative measures of employment for populations with well-described mental disorders (eg, anxiety, depression, PTSD, substance abuse). Eighty-one articles were considered in-scope at this stage of the review. The selection of articles on work and mental disorders for this review is summarized in the Figure.

Figure.

Selection of articles for review.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

To provide some structure to the reading of the articles, a form was completed to describe the population of interest, how the outcome of work was measured, the intervention (if any), and the factors identified as influencing work for people with mental disorders. To expedite the process with the large number of selected articles, authors of the articles reviewed were not contacted for additional information. The process was inclusive; if 1 or more reviewers said the article should be kept, it was kept. Quality assessment did not examine the sources of bias but focused on the relevance of the study to the objectives of the review, the choice of quantitative outcome measures of work, the differentiation of mental disorders, and the adequacy of the defining characteristics of the intervention.

Data Synthesis

A narrative synthesis was used because the studies were diverse in terms of interventions. Thematic analysis systematically identified the recurrent themes and concepts across the in-scope studies.

The potential factors identified by the literature were mapped to the framework agreed to by the team before undertaking the review. We planned a systematic synthesis of studies of reintegration to work; however, the results of the scoping review were too limited to accomplish this (see “Discussion” section).

2012 Update of the Literature Review

This review was updated in 2012 to provide reassurance that no important articles were missed. The Veterans Affairs Canada library re-ran the computerized search described above for the period of July 2009 to July 2012. This stage identified a total of 1,267 articles after duplicates were removed. Abstracts of these 1,267 articles were screened by the lead author, through the use of the criteria described above. The review of abstracts resulted in acquisition of 49 articles. With the use of the full text of the article, the lead author determined whether the articles were in-scope, with the same criteria applied to the abstracts. As the result of this update, 16 articles were added to the review.

Results

Scope of the Literature

This review found a history of publications on work and mental health dating back to 1919. The 81 articles considered in-scope for this review dated from 1996 to 2009 and covered a wide variety of designs and methods. In-scope studies included populations with well-described mental disorders (eg, depression, anxiety, PTSD, substance-use disorders) and quantitative measures of employment.

Three major categories emerged from the in-scope articles:

return to work (RTW)—employment with same employer after a short work absence;

supported employment (SE)—employment as entry to the workforce; and

reintegration—employment with a new employer, usually after a prolonged work absence.

Return to work.

The RTW category was assigned to 25 articles that dealt with employment in the same workplace after a short work absence (sick leave) for mental disorders. Much of the RTW literature describes people with musculoskeletal disorders and was not included in this review. The full list of the in-scope RTW articles is described elsewhere.6

Eleven articles were on RTW for depression. These articles were summarized by a Cochrane systematic review that concluded there was no evidence of effective treatments to reduce sick leave after examining RCTs for antidepressant medication, enhanced primary care, and psychological interventions.7

Four articles addressed RTW for comorbid musculoskeletal disorders and depression. These articles were summarized by a systematic review that concluded for workers within 3 months of onset of nonspecific lower back pain, depression was the consequence of sick leave rather than its cause.8 Sick leave was longest for patients with comorbid chronic pain, depression, and musculoskeletal problems.9

Two articles focused on RTW for adjustment disorders. Sick leave was decreased by a brief psychosocial intervention10 and by rehabilitation care that included consultation with the work supervisor.11 Seven other articles dealt with RTW for a mixture of mental health conditions and described initiatives in varying detail.

One study12 developed an RTW intervention for mental health problems through the use of the musculoskeletal RTW literature. The paradigm described sick leave as not simply the consequence of illness and impairment, but the result of complex interactions between the worker, health care, work environment, and financial compensation systems. Four steps were identified for an intervention: (1) evaluate work situation—identify barriers and facilitators to work; (2) evaluate readiness to commit to RTW—reactivate employment relationship and provide psychological, occupational, and physical conditioning; (3) establish active commitment to RTW—reduce obstacles for RTW and instigate progressive reintegration to work; and (4) maintain work.

Supported employment.

The SE category was assigned to 29 articles that dealt with employment as entry to the workforce for people with severe mental illness that includes diagnoses of schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorders, bipolar disorders, and personality disorders. Because many of these disorders were excluded from this review, in-scope articles do not form a comprehensive review of SE. The full list of the in-scope SE articles is described elsewhere.6

The SE literature has been well summarized with a series of reviews. Supported employment emerged during the 1980s, in contrast to earlier models that emphasized prevocational training.13 By 2001, a Cochrane review concluded that SE was effective to increase competitive employment, and there was no clear evidence that prevocational training was effective.14 One SE initiative, individual placement and support (IPS), has emerged as the standardization of evidence-based SE. The most recent review in 2008 demonstrated the effectiveness of IPS to increase competitive employment from 23% for control participants to 61% for clients with severe mental illness.15 The most recent RCT of IPS was conducted in Europe.16 The concept of supported employment was illuminated with this quote: “There is a thread that connects the programs that get clients working: staff throughout their organizations possess a high opinion of the abilities, talents, and spirit of their consumers.”17(p238) Despite the mounting evidence, the availability of SE programs in Canada was limited in 2006.18

The literature generally includes poor descriptions of initiatives. In contrast, IPS has a defined set of 6 principles19: (1) the goal is competitive employment; (2) admission is based on the desire to work, no exclusions are based on symptoms or work readiness; (3) rapid job searches are initiated that avoid preplacement training; (4) mental health and vocational services are integrated within a single team; (5) attention is on consumer preference rather than providers' judgments; and (6) follow-up support is time-unlimited and individualized. These critical ingredients have led to development of fidelity scales that can describe IPS in detail20 and are used to replicate interventions and encourage empirical testing.

Reintegration.

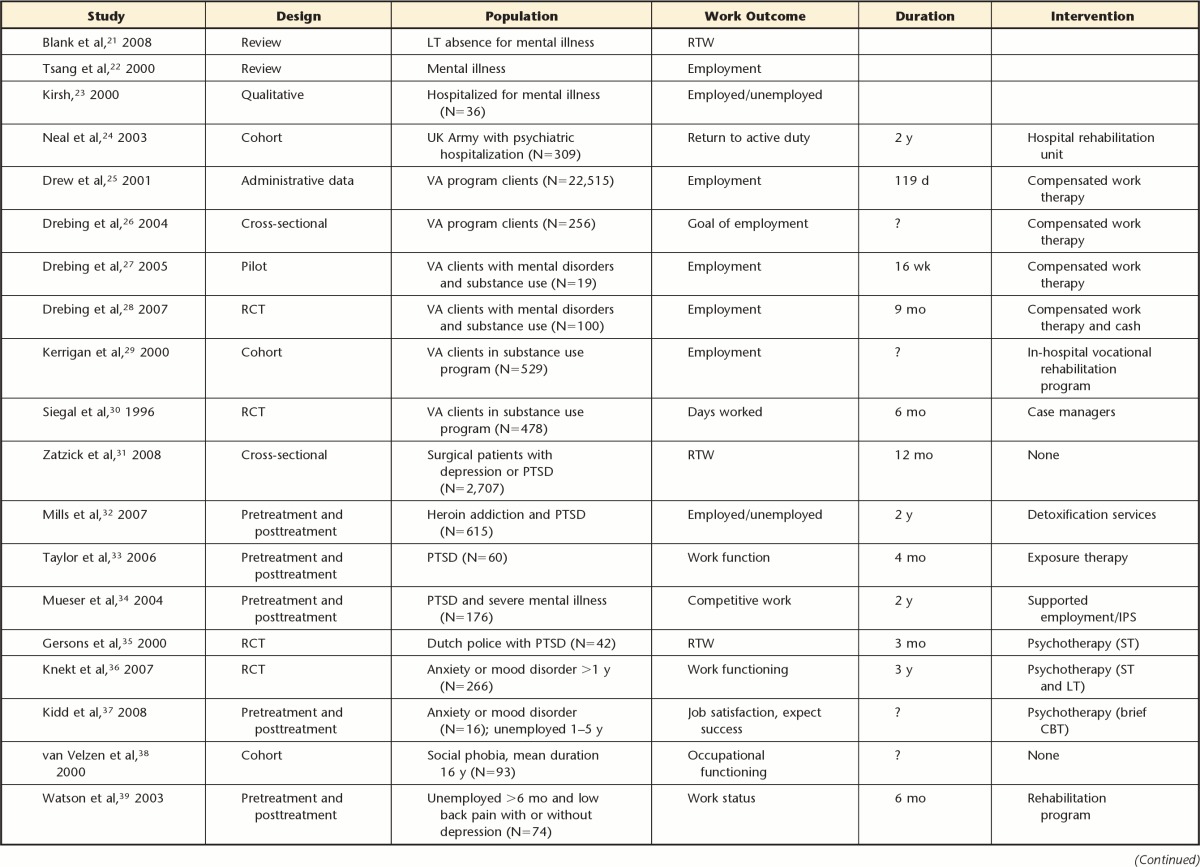

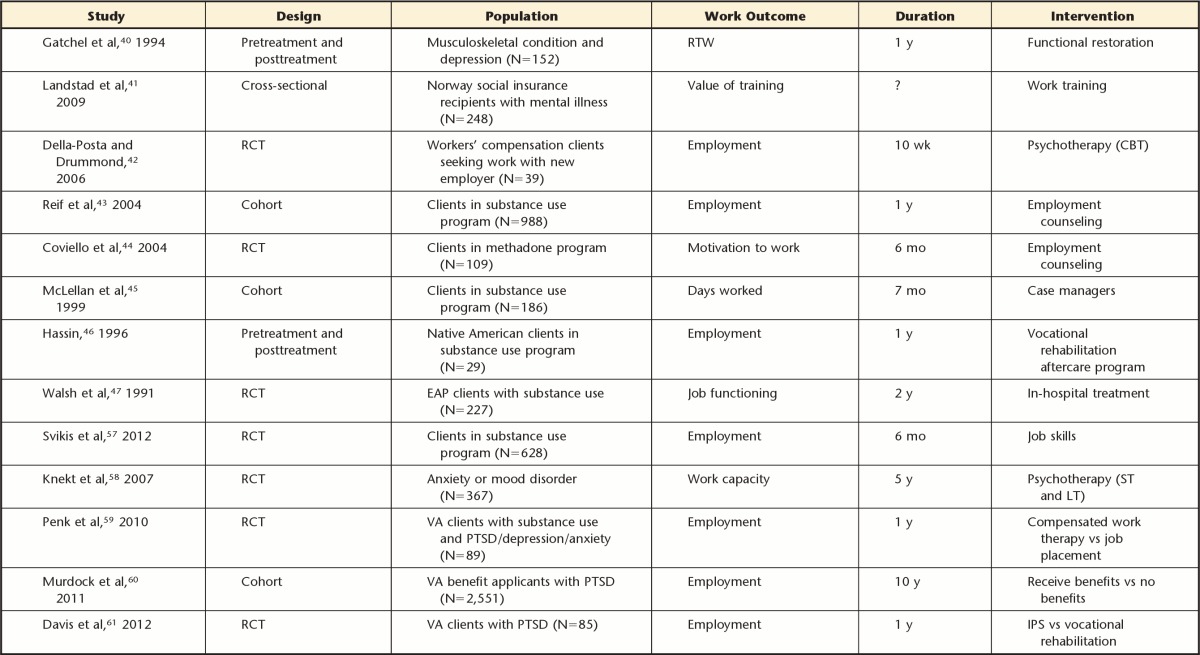

The reintegration category was assigned to 27 articles on return to employment in a new workplace after a prolonged work absence for people with a mental disorder. The Table lists characteristics of the in-scope reintegration articles and includes the additional 5 articles found in the 2012 update.

Table.

Characteristics of Reintegration Studiesa

RTW=return to work, VA=US Veterans Administration, ?=unknown, PTSD=posttraumatic stress disorder, ST=short term, LT=long term, CBT=cognitive-behavioral therapy, RCT=randomized controlled trial, EAP=employee assistance program, IPS=individual placement and support.

One review found little robust evidence that mental illness prolongs work absence and contradictory conclusions as to which factors carry the greatest risk of absence.21 A previous review found that symptoms had inconsistent associations with work absence.22 A qualitative study described the meaningfulness of work, job satisfaction, and tenure.23

Only 7 of the in-scope articles were studies of veterans, and all of these articles were assigned to the reintegration category. One article described a program to return British soldiers to active duty,24 but this was considered RTW for serving military, not veterans. Four articles described compensated work therapy for American veterans,25–27 with half the clients expressing the goal of competitive employment.28 Two articles described American substance abuse initiatives.29,30 None of these 7 articles provided information on their military service characteristics.

Five articles were based on populations with a diagnosis of PTSD; none of these were studies of veterans. One year after hospitalization for serious injury, 30% of patients with PTSD were working compared with 60% for those without PTSD; 20% of patients with comorbid PTSD and depression were working.31 Patients with both PTSD and heroin addiction had lower rates of employment after 2 years compared with patients with heroin addiction only.32 Patients with PTSD and depression had increased work impairment.33 People with both PTSD and schizophrenia did not benefit from IPS.34 A study of Dutch police with PTSD of approximately 4 years' duration demonstrated a significantly increased rate of return to police work 3 months after treatment with eclectic psychotherapy: 86% versus 60% in a wait-list control group.35

Five articles were based on populations with other diagnoses. Patients with anxiety or mood disorder for more than 1 year had no differences in employment 3 years after initiation of psychotherapy for either 6 months/short-term or 3 years/long-term.36 Patients with anxiety or mood disorders reported improved mastery but no improvement in regard to employment after cognitive-behavioral therapy.37 Patients with social phobia demonstrated higher occupational functioning than those with avoidant personality disorder.38 Depression reduced rates of finding a new employer 6 months after rehabilitation for chronic low back pain, but length of time out of work did not reduce rates.39 One year after rehabilitation that incorporated mental health professionals, 85% of patients with comorbid musculoskeletal injury and depression were working.40

An additional 7 articles were assigned the reintegration theme. One study described social insurance recipients in Norway who received work training.41 Another study described workers' compensation clients who received cognitive-behavioral therapy.42 Substance abuse initiatives included employment counseling,43,44 clinical case managers,45 aboriginal vocational rehabilitation,46 and hospitalization.47

Most of the reintegration articles provided very little description of an intervention and few measures of confounders and provided inadequate information for quality assessment. This review found that studies were not similar enough to synthesize and that it was inappropriate to pool results for the reintegration category.

2012 Update of Scope of Literature

Return to work for anxiety disorders showed a decrease in sick leave after cognitive-behavior therapy.48 A Cochrane review found moderate evidence that workplace interventions can reduce sick leave for workers with musculoskeletal disorders; there was no evidence of their effectiveness for mental health problems.49

The SE literature has expanded to other countries with generous social security programs such as Switzerland, finding 48% competitive employment in the IPS group compared with 17% in the vocational rehabilitation group that emphasized “train then place.”50 Individual placement and support also was effective for people with comorbid severe mental illness and substance-use disorder: 60% competitive employment compared with 24% in vocational rehabilitation.51 The trajectory of symptoms was the same for working and nonworking people with severe mental illness.52 Clients with severe mental illness benefit from IPS regardless of their work history or clinical background; this finding refutes the practice of excluding individuals on the basis of disability income or symptoms.53 This was among the many barriers described for the implementation of SE.54 The reluctance to refer people with symptoms for SE has relevance for Canada, where an examination of 23 SE programs found only 13% followed the IPS model.55 The control group of vocational rehabilitation used in the SE literature is described in a review.56

The reintegration literature did not find interventions that improved employment in patients with substance use disorders57 or those with mood or anxiety disorders.58 Also included were 3 new studies of veterans. One study continued the examination of compensated work therapy that was not effective to increase employment.59 Another study found similar rates of employment for veterans with PTSD among those awarded or denied a benefit claim, emphasizing the complex relationship between compensation and health.60 The recent randomized trial in US veterans with PTSD provides evidence of the effectiveness of IPS in this population with 76% competitive employment compared with 28% in vocational rehabilitation.61

Factors Associated With Work Reintegration and Mental Disorders

To identify factors that may be associated with reintegration of workers with mental disorders after a prolonged absence, we assessed the 81 in-scope articles. The 27 articles that more directly applied to reintegration were too limited; therefore, we cast a wider net by looking at all 81 articles. The identified factors were organized into 4 systems, with a model originally developed for RTW for people with musculoskeletal disorders.62 We adapted this model for veterans with mental disorders by defining the 4 systems as: (1) workplace system—Department of National Defence military service that they are leaving and civilian work that they are entering; (2) personal system—veteran with mental disorder; (3) health care system—OSI clinics and provincial health services; and (4) compensation system—Veterans Affairs Canada legislation and programs.

The factors described in the in-scope articles are organized by means of this model. However, they are considered potential factors because the literature is contradictory and their quality is variable.21

Workplace system factors potentially include employment, sick-leave days, local unemployment rate, job satisfaction, job success or occupation activity, support or problems with colleagues and supervisors, and work that balances challenge and predictability. Quality of leadership was the main finding in a recent study.63

Personal system factors potentially include work history, work capacity or ability, social skills or support, family relationships, stressful life events outside of work, recovery expectation, fear avoidance, locus of control, mastery, and importance of work to quality of life. In a recent study, personal incentives were associated with employment, but there was no evidence that personal barriers such as symptoms were associated with lack of employment.64

Health care system factors potentially include differentiation between diagnosis of depression, stress, and anxiety and symptomatology, cognitive function, general dysfunction, and the lengthy periods of both relapse and recovery.

Compensation system factors potentially include finances and perceived or real financial disincentives to returning to work known as the “benefit trap.” A recent study noted that additional research is needed to explore the complex relationship between compensation and health outcomes.64

Discussion

The existing literature provided 5 key findings to inform the development of research to enhance successful reintegration of veterans with mental disorders into the civilian workplace.

Few Studies Were Conducted in Populations of Veterans

Only 10 articles on work reintegration of veterans were included in this review, despite the need that we have identified. None of these articles were of Canadian veterans; most were American veterans. The RTW literature does not directly apply to veterans because they are not on a brief absence before a return to the military workplace. The SE literature deals with prolonged absence but for severe mental disorders instead of the more common disorders in veterans (eg, PTSD, depression).

The Literature Dealing With Reintegration to a New Workplace After a Prolonged Absence for Those With Mental Health Disorders Is Sparse

Despite the comprehensiveness of this review on work and mental health, only 32 articles were identified that addressed employment after a prolonged work absence for people with a mental disorder and their need for reintegration to the workforce in a new workplace. The quality of these studies did not provide evidence for effective interventions in this area.

People With Mental Health Conditions Can Return to Work After a Prolonged Absence

Competitive employment rates were increased from 23% to more than 60% for people with severe mental illness by effective supported employment programs. However, competitive employment may be full-time or part-time, with payment as low as minimum wage.

Prolonged Absence From the Workplace Does Not Require Reduction of Symptoms Before Seeking Work

The most promising intervention for work was IPS. This effective program of supported employment does not exclude people on the basis of symptoms. Sick leave is not simply the consequence of illness and impairment but is the result of complex interactions in which health and work influence each other, and the RTW can improve mental health.

There Is No Clear Consensus on Which Factors Are Associated With Work Among People With Mental Disorders

The literature provides many potential risk factors that may predict short-term sickness absence. The existing literature is contradictory, emphasizes personal factors, shows a paucity of compensation system factors, and provides no factors related to military service. The literature provided little consideration of the issues affecting prolonged absence, job loss, and the subsequent need to reintegrate into the workforce with a new employer.

Several major issues emerged from the existing literature. Much of the literature focused on either work or health outcomes. Work outcomes usually emphasized a dichotomy between employed and unemployed. There was remarkably inconsistent reporting of the duration of unemployment, differentiation between a new or existing job, or part-time or full-time status. Few studies provided diagnostic inclusion criteria. The definitions of poor mental health varied widely, were often not based on validated and reliable scales, and had inconsistent reporting of the duration of the diagnosis. Much of the literature described a program or intervention by including all their clients with a heterogeneous assortment of diagnoses that require different treatment regimens. Few studies provided a detailed description of the intervention. This problem also has been noted by other researchers examining PTSD65 and by those examining RTW for musculoskeletal disorders who call the result “black box evaluation.”66 Few studies accounted for important confounding factors such as physical health conditions, income, or education. Few studies were RCTs, the method often required by evidence reviews. Although this review may have missed studies, the limitations and inconsistency of the literature that was included made it difficult to develop descriptive evidence tables or to pool results in a synthesis. The lack of RCTs restricted us to a scoping review that did not assess the quality of evidence in each article.

The lack of literature that we found that deals with reintegration to a new workplace after a prolonged absence from work for people with mental health disorders is corroborated by a recent review of PTSD that found no literature that provided evidence on work outcomes.65 Other reviews have found no evidence of effective interventions to reduce sick leave for workers with depression7 or adjustment disorders.49 On the other hand, symptom alleviation is effective for cognitive-behavioral therapy for PTSD65 and antidepressants for depression.67 This discrepancy supports the assumption that RTW and resolution of symptoms are not directly correlated.49

A primary focus on the amelioration of symptoms for people with mental health disorders is unlikely to facilitate their work reintegration. This conclusion is supported by evidence for effective employment programs for people with severe mental illness that do not exclude people on the basis of symptoms,15 whose symptoms may not improve with work,52 and whose symptoms are not a barrier to job acquisition,53,64 and for musculoskeletal disorders, in which interventions that reduce sick leave are not effective in reducing symptoms.51 Work and health influence each other in complex interactions.12 Optimal care includes making effective treatments more available, accessible, and acceptable.54

Individual placement and support clearly emerged in our literature review as the most promising tool to facilitate workplace reintegration for those with mental disorders; multiple randomized trials have shown it to be clearly superior to conventional vocational rehabilitation approaches in leading to competitive employment, more weeks of work, and higher incomes among those with serious mental illness. For this reason, IPS is now the standard practice for US Department of Veterans Affairs clients with serious mental illness who want to work, and their first trials of PTSD indicate that IPS also will help the much larger population of young veterans with service-related mental disorders.53 Although questions remain about the intensity and duration of the support needed, IPS is the most appealing starting point for the development of an intervention to facilitate workplace reintegration for veterans with mental disorders.

Future research directions to shed light on factors in workplace reintegration of veterans with mental disorders have been identified by this literature review. The population of veterans with mental disorders has not been well studied, and further research on this population can contribute to the sparse literature on employment for others with a mental disorder who are seeking a new workplace after a prolonged work absence. The existing literature provided many potential factors associated with work reintegration and mental disorders. Unfortunately, these factors have not been assessed for their ability to predict RTW with a new employer after a prolonged absence21 or for their appropriateness for a veteran model. Our team noted the lack of factors describing the compensation system or the veteran experience. Subsequently, our next step was to undertake a qualitative study with veterans and the professionals they deal with to describe experiences and perceptions of barriers to and facilitators of workplace reintegration for veterans with mental health conditions.68 This step will further develop the work originally designed for RTW for people with musculoskeletal disorders62 toward a model for understanding work reintegration and mental health for veterans. Our team also is working with the Barriers to Employment and Coping Efficacy Scales (BECES), a tool used in clinical practice to inform case planning for people with severe mental disorders.69 The development of BECES-V provides contextualization of the tool's questions for military veterans, with the potential to document the nature of the barriers encountered by veterans with a broader range of mental disorders during transition to civilian workplaces.70 Our team will benefit from this work to determine the essential components of a potentially effective work intervention.

Because this scoping review confirmed that studies were not similar enough to synthesize in a meta-analysis, the need for well-designed RCTs is emphasized. The design of an RCT will require work measures that describe prolonged absence in more detail than sick-leave days or employed versus unemployed. Because our population of interest has been unemployed for many years, a follow-up of more than 1 year is required. The inclusion criteria for mental disorders must be based on validated and reliable scales used across the OSI network and restricted to a small number of diagnoses such as PTSD, depression, or both. Understanding who will benefit from an effective intervention will require analytical techniques for patients with complex conditions who do not fit clearly into standard diagnostic categories71 and accounting for confounding factors such as comorbid physical health conditions.

This comprehensive literature review found generally limited knowledge about how to integrate people with mental disorders into the workplace after a prolonged absence. Even less was found for veterans. Whereas the most promising intervention was IPS, there is only recent evidence of its potential for our population of interest. Further research on the epidemiology of the factors involved in work reintegration for veterans with mental disorders is needed to form an important basis to intervention studies that will provide insight into what works and what does not work. A robust body of evidence is essential in promoting successful transition from military service to the civilian workplace, in particular for veterans with mental disorders. A broader body of knowledge is needed on employment in a new workplace after a prolonged work absence for any people with a mental disorder.

Footnotes

Dr Van Til, Dr Fikretoglu, Dr Patten, Dr Wang, Dr Wong, Dr Zamorski, Dr Loisel, and Dr Pedlar provided concept/idea/research design. Dr Van Til, Dr Fikretoglu, Dr Pranger, Dr Patten, Dr Zamorski, Dr Thompson, and Dr Pedlar provided writing. Dr Van Til, Dr Pranger, Dr Wang, and Dr Zamorski provided data collection. Dr Van Til, Dr Fikretoglu, Dr Pranger, and Dr Zamorski provided data analysis. Dr Van Til and Dr Pedlar provided project management. Dr Van Til, Dr Fikretoglu, Dr Patten, and Dr Pedlar provided fund procurement. Dr Van Til, Dr Wang, Dr Shields, and Dr Pedlar provided institutional liaisons. Dr Pranger, Dr Patten, Dr Wang, Dr Wong, Dr Zamorski, Dr Corbiére, Dr Shields, and Dr Thompson provided consultation (including review of manuscript before submission).

When the article was written, many of the authors were under the employ of the Government of Canada; these include: Dr Van Til, Dr Fikretoglu, Dr Pranger, Dr Wong, Dr Zamorski, Dr Shields, Dr Thompson, and Dr Pedlar, who were employed by either the Department of Veterans Affairs or the Department of National Defence. The Departments of Veterans Affairs and National Defence are federal government departments and any copyrighted material created by a federal employee is Crown copyright.

The information in this article was the topic of an oral presentation at the Canadian Military and Veteran Health Research Forum; November 14-16, 2011; Kingston, Ontario, Canada.

This work was funded by the Canadian Institutes for Health Research.

An Excel spreadsheet with details on the articles is available by contacting the first author; full search strategy also is available.

References

- 1. Kirby MJL, Keon WJ. Out of the Shadows At Last: Transforming Mental Health, Mental Illness, and Addiction Services in Canada. Ottawa, Ontario, Canada: Standing Senate Committee on Social Affairs, Science and Technology; 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thompson JM, MacLean MB, Van Til L, et al. Survey on Transition to Civilian Life: Report on Regular Force Veterans. Research Directorate, Veterans Affairs Canada, Charlottetown, and Director General Military Personnel Research and Analysis, Department of National Defence, Ottawa: January 4, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 3. Iversen A, Nikolaou V, Greenberg N, et al. What happens to British veterans when they leave the armed forces? Eur J Public Health. 2005;15:175–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Anderson K, Mitchell J. Effects of military experience on mental health problems and work behaviour. Med Care. 1992;30:554–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Savoca E, Rosenheck R. The civilian labor market experiences of Vietnam-era veterans: the influence of psychiatric disorders. J Mental Health Policy Econ. 2000;3:199–207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Van Til LD, Pranger T, Pedlar D. Literature Review of Work and Mental Disorders. Veterans Affairs Canada Research Directorate Technical Report, December 17, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nieuwenhuijsen K, Bültmann U, Neumeyer-Gromen A, et al. Interventions to improve occupational health in depressed people. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008;(2):CD006237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Iles RA, Davidson M, Taylor NF. Psychosocial predictors of failure to return to work in non-chronic non-specific low back pain: a systematic review. Occup Environ Med. 2008;65:507–517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Sanders SH, Brena SF. Empirically derived chronic pain patient subgroups: the utility of multidimensional clustering to identify differential treatment effects. Pain. 1993;54:51–56 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. van der Klink JJ, Blonk RW, Schene AH, van Dijk FJ. Reducing long term sickness absence by an activating intervention in adjustment disorders: a cluster randomised controlled design. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60:429–437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nieuwenhuijsen K, Verbeek JH, Siemerink JC, Tummers-Nijsen D. Quality of rehabilitation among workers with adjustment disorders according to practice guidelines; a retrospective cohort study. Occup Environ Med. 2003;60(suppl 1):i21–i25 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Briand C, Durand MJ, St Arnaud L, Corbiere M. Work and mental health: learning from return-to-work rehabilitation programs designed for workers with musculoskeletal disorders. Int J Law Psychiatry. 2007;30:444–457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bond GR, Drake RE, Mueser KT, Becker DR. An update on supported employment for people with severe mental illness. Psychiatr Serv. 1997;48:335–346 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Marshall M, Bond GR, Huxley P. Vocational rehabilitation for people with severe mental illness. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2001;(2):CD003080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Bond GR, Drake RE, Becker DR. An update on randomized controlled trials of evidence-based supported employment. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2008;31:280–290 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Burns T, Catty J. IPS in Europe: the EQOLISE trial. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2008;31:313–317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Gowdy EL, Carlson LS, Rapp CA. Practices differentiating high-performing from low-performing supported employment programs. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2003;26:232–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kirsh B, Krupa T, Cockburn L, Gewurtz R. Work initiatives for persons with severe mental illnesses in Canada: a decade of development. Can J Commun Ment Health. 2006;25:173–191 [Google Scholar]

- 19. Bond GR. Supported employment: evidence for an evidence-based practice. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2004;27:345–359 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Koop JI, Rollins AL, Bond GR, et al. Development of the DPA Fidelity Scale: using fidelity to define an existing vocational model. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2004;28:16–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Blank L, Peters J, Pickvance S, et al. A systematic review of the factors which predict return to work for people suffering episodes of poor mental health. J Occup Rehabil. 2008;18:27–34 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Tsang H, Lam P, Ng B, Leung O. Predictors of employment outcome for people with psychiatric disabilities: a review of the literature since the mid '80s. J Rehabil. 2000;66:19–31 [Google Scholar]

- 23. Kirsh B. Work, workers, and workplaces: a qualitative analysis of narratives of mental health consumers. J Rehabil. 2000;66:24–30 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Neal LA, Kiernan M, Hill D, et al. Management of mental illness by the British Army. Br J Psychiatry. 2003;182:337–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Drew D, Drebing CE, Van Ormer A, et al. Effects of disability compensation on participation in and outcomes of vocational rehabilitation. Psychiatr Serv. 2001;52:1479–1484 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Drebing CE, Van Ormer EA, Krebs C, et al. The impact of enhanced incentives on vocational rehabilitation outcomes for dually diagnosed veterans. J Appl Behav Anal. 2005;38:359–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Drebing CE, Van Ormer EA, Mueller L, et al. Adding contingency management intervention to vocational rehabilitation: outcomes for dually diagnosed veterans. J Rehabil Res Dev. 2007;44:851–865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Drebing CE, Van Ormer EA, Schutt RK, et al. Client goals for participating in VHA vocational rehabilitation: distribution and relationship to outcome. Rehabil Couns Bull. 2004;47:162–172 [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kerrigan AJ, Kaough JE, Wilson BL, et al. Vocational rehabilitation outcomes of veterans with substance use disorders in a partial hospitalization program. Psychiatr Serv. 2000;51:1570–1572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Siegal HA, Fisher JH, Rapp RC, et al. Enhancing substance abuse treatment with case management: its impact on employment. J Subst Abuse Treat. 1996;13:93–98 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Zatzick D, Jurkovich GJ, Rivara FP, et al. A national US study of posttraumatic stress disorder, depression, and work and functional outcomes after hospitalization for traumatic injury. Ann Surg. 2008;248:429–435 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mills KL, Teesson M, Ross J, Darke S. The impact of post-traumatic stress disorder on treatment outcomes for heroin dependence. Addiction. 2007;102:447–454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Taylor S, Wald J, Asmundson GJG. Factors associated with occupational impairment in people seeking treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder. Can J Commun Ment Health. 2006;25:289–301 [Google Scholar]

- 34. Mueser KT, Essock SM, Haines M, et al. Posttraumatic stress disorder, supported employment, and outcomes in people with severe mental illness. CNS Spectrums. 2004;9:913–925 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Gersons BP, Carlier IV, Lamberts RD, van der Kolk BA. Randomized clinical trial of brief eclectic psychotherapy for police officers with posttraumatic stress disorder. J Trauma Stress. 2000;13:333–347 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Knekt P, Lindfors O, Laaksonen MA, et al. ; Helsinki Psychotherapy Study Group Effectiveness of short-term and long-term psychotherapy on work ability and functional capacity: a randomized clinical trial on depressive and anxiety disorders. J Affective Disord. 2008;107:95–106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kidd SK, Boyd GM, Bieling P, et al. Effect of a vocationally-focused brief cognitive behavioural intervention on employment-related outcomes for individuals with mood and anxiety disorders. Cogn Behav Ther. 2008;37:247–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Van Velzen CJM, Emmelkamp PMG, Scholing A. Generalized social phobia versus avoidant personality disorder: differences in psychopathology, personality traits, and social and occupational functioning. J Anxiety Disord. 2000;14:395–411 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Watson PJ, Booker CK, Moores L, Main CJ. Returning the chronically unemployed with low back pain to employment. Eur J Pain. 2004;8:359–369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Gatchel RJ, Polatin PB, Mayer TG, Garcy PD. Psychopathology and the rehabilitation of patients with chronic low back pain disability. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 1994;75:666–670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Landstad B, Hedlund M, Wendelborg C, Brataas H. Long-term sick workers experience of professional support for re-integration back to work. Work. 2009;32:39–48 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Della-Posta C, Drummond PD. Cognitive behavioural therapy increases re-employment of job seeking worker's compensation clients. J Occup Rehabil. 2006;16:223–230 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Reif S, Horgan CM, Ritter GA, Tompkins CP. The impact of employment counseling on substance user treatment participation and outcomes. Subst Use Misuse. 2004;39:2391–2424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Coviello DM, Zanis DA, Lynch K. Effectiveness of vocational problem-solving skills on motivation and job-seeking action steps. Subst Use Misuse. 2004;39:2309–2324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. McLellan AT, Hagan TA, Levine M, et al. Does clinical case management improve outpatient addiction treatment? Drug Alcohol Depend. 1999;55:91–103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Hassin J. After substance abuse treatment, then what? The NARTC/Oregon Tribal and Vocational Rehabilitation Project. Am Rehabil. 1996;22:12–19 [Google Scholar]

- 47. Walsh DC, Hingson RW, Merrigan DM, et al. A randomized trial of treatment options for alcohol-abusing workers. N Engl J Med. 1991;325:775–782 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Linden M, Zubragel D, Bar T. Occupational functioning, sickness absence and medication utilization before and after cognitive-behaviour therapy for generalized anxiety disorders. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2011;18:218–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. van Oostrom SH, Driessen MT, de Vet HCW, et al. Workplace interventions for preventing work disability. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009(2):CD006955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Hoffmann H, Jackel D, Glauser S, Kupper Z. A randomised controlled trial of the efficacy of supported employment. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2012;125:157–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Mueser KT, Campbell K, Drake RE. The effectiveness of supported employment in people with dual disorders. J Dual Diagn. 2011;7:90–102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kukla M, Bond GR, Xie H. A prospective investigation of work and nonvocational outcomes in adults with severe mental illness. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2012;200:214–222 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Campbell K, Bond GR, Drake RE, et al. Client predictors of employment outcomes in high-fidelity supported employment: a regression analysis. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2010;198:556–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Pogoda TK, Cramer IE, Rosenheck RA, Resnick SG. Qualitative analysis of barriers to implementation of supported employment in the Department of Veterans Affairs. Psychiatr Serv. 2011;62:1289–1295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Corbière M, Lanctôt N, Lecomte T, et al. A Pan-Canadian evaluation of supported employment programs dedicated to people with severe mental disorders. Comm Ment Health J. 2010;46:44–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Chamberlain MA, Fialka Moser V, Schuldt Ekholm K, et al. Vocational rehabilitation: an educational review. J Rehabil Med. 2009;41:856–869 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Svikis DS, Keyser-Marcus L, Stitzer M, et al. Randomized multi-site trial of the Job Seekers' Workshop in patients with substance use disorders. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2012;120:55–64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Knekt P, Lindfors O, Laaksonen MA, et al. Quasi-experimental study on the effectiveness of psychoanalysis, long-term and short-term psychotherapy on psychiatric symptoms, work ability and functional capacity during a 5-year follow-up. J Affect Disord. 2011;132:37–47 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Penk W, Drebing CE, Rosenheck RA, et al. Veterans Health Administration Transitional work experience vs. job placement in veterans with co-morbid substance use and non-psychotic psychiatric disorders. Psychiatr Rehabil J. 2010;33:297–307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Murdoch M, Sayer NA, Spoont MR, et al. Long-term outcomes of disability benefits in US veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2011;68:1072–1080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Davis LL, Leon AC, Toscano R, et al. A randomized controlled trial of supported employment among Veterans with posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychiatr Serv. 2012;63:464–470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Loisel P, Buchbinder R, Hazard R, et al. Prevention of work disability due to musculoskeletal disorders: the challenge of implementing evidence. J Occup Rehabil. 2005;15:507–524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Munir F, Burr H, Hansen JV, et al. Do positive psychosocial work factors protect against 2-year incidence of long-term sickness absence among employees with and those without depressive symptoms? A prospective study. J Psychosom Res. 2011;70:3–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Larson JE, Ryan CB, Wassel AK, et al. Analyses of employment incentives and barriers for individuals with psychiatric disabilities. Rehabil Psychol. 2011;56:145–149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Institute of Medicine (IOM) Treatment of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: An Assessment of the Evidence. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2008. Available at: http://www.nap.edu/catalog/11955.html Accessed September 17, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 66. Durand MJ, Vachon B, Loisel P, et al. Constructing the program impact theory for an evidence-based work rehabilitation program for workers with low back pain. Work. 2003;21:233–242 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Arroll B, Elley CR, Fishman T, et al. Antidepressants versus placebo for depression in primary care. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009(3):CD007954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Farrar P, Buchner D, Pranger T. Barriers and Facilitators to Optimal Workplace Re-integration of Veterans With Mental Health Conditions. Qualitative Study Report. Report to Veterans Affairs Canada, December 20, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 69. Corbière M, Mercier C, Lesage AD. Perceptions of barriers to employment, coping efficacy, and career search efficacy in people with mental illness. J Career Assessment. 2004;12:460–478 [Google Scholar]

- 70. Thompson JM, Corbière M, Van Til M, et al. BECES-V: Modification of the BECES Tool (Barriers to Employment and Coping Efficacy Scales) for Veterans With Mental Health Problems Reintegrating in the Workplace. Veterans Affairs Canada, Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island, and CAPRIT (Action Centre for Prevention and Rehabilitation of Work Disability), School of Rehabilitation, Université de Sherbrooke, Longueuil, Quebec: VAC Research Directorate Technical Report June 20, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 71. Macias C, Jones DR, Hargreaves WA, et al. When programs benefit some people more than others: tests of differential service effectiveness. Administration Policy Mental Health Mental Health Serv Res. 2008;35:283–294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]