The calcium-dependent protease Calpain A targets Cactus/IκB for proteolysis. Calpain A generates Cactus fragments deleted of Toll-responsive N-terminal sequences that are incorporated into signaling complexes with NFκB/c-Rel. It is proposed that Calpain A regulates free Cactus and modulates Toll signals in the Drosophila embryo and immune system.

Abstract

Calcium-dependent cysteine proteases of the calpain family are modulatory proteases that cleave their substrates in a limited manner. Among their substrates, calpains target vertebrate and invertebrate IκB proteins. Because proteolysis by calpains potentially generates novel protein functions, it is important to understand how this affects NFκB activity. We investigate the action of Calpain A (CalpA) on the Drosophila melanogaster IκB homologue Cactus in vivo. CalpA alters the absolute amounts of Cactus protein. Our data indicate, however, that CalpA uses additional mechanisms to regulate NFκB function. We provide evidence that CalpA interacts physically with Cactus, recognizing a Cactus pool that is not bound to Dorsal, a fly NFκB/Rel homologue. We show that proteolytic cleavage by CalpA generates Cactus fragments lacking an N-terminal region required for Toll responsiveness. These fragments are generated in vivo and display properties distinct from those of full-length Cactus. We propose that CalpA targets free Cactus, which is incorporated into and modulates Toll-responsive complexes in the embryo and immune system.

INTRODUCTION

Calpains are Ca2+-dependent modulatory proteases with numerous substrates and functions. They have been implicated in several diseases, such as limb-girdle muscular dystrophy, Huntington disease, Alzheimer disease, and cancer (Bertipaglia and Carafoli, 2007). Unlike degrading enzymes, calpains cleave substrates in a limited manner, generating novel activities by substrate proteolysis (Friedrich and Bozoky, 2005; Sorimachi et al., 2011). For instance, μ-calpain cleaves the signaling molecule β-catenin, generating an active form that has different targets from those of the full-length molecule and is correlated with specific fate choices during mouse hepatoblast differentiation (Lade et al., 2012). Proteolysis is an essential step in the regulation of NFκB activity (Baud and Derudder, 2011). Calpain-dependent proteolysis of the inhibitor IκBα has been reported in cancer cell lines, regulating apoptosis (Pianetti et al., 2001; Li et al., 2010). Calpain 3 deficiency is also associated with perturbations in the IκBα/NFκB pathway in limb-girdle muscular dystrophy (Baghdiguian et al., 1999). In the immune system, vertebrate m-calpain cleaves IκB proteins in response to tumor necrosis factor α (Han et al., 1999). Moreover, it has been suggested that m- and μ-calpain regulate IκB in parallel to signals through IL-1 or Toll (Han et al., 1999; Shumway et al., 1999; Shen et al., 2001). Although potentially important as a therapeutic target in cancer progression and in modulating the immune response, the functional significance of calpains in regulating NFκB activity has been poorly addressed.

We used the invertebrate model organism Drosophila melanogaster to investigate in more detail the mechanism of calpain action and the functional significance of Calpain A in modulating NFκB activity. Four calpains have been described in Drosophila: calpains A–C and Sol (Friedrich et al., 2004). Unlike vertebrate proteins, Drosophila calpains act as monomers, and no calpastatin inhibitor has been described in the fruitfly. The classic calpains A and B (CalpA and CalpB) are expressed in different tissues throughout several stages of development (Emori and Saigo, 1994; Park and Emori, 2008; Theopold et al., 1995; Jekely and Friedrich, 1999). CalpB has been implicated in a model of AML1-ETO oncoprotein in the fruitfly and migration of somatic border cells during oogenesis (Osman et al., 2009; Kokai et al., 2012). CalpA is also expressed maternally, and low levels of maternally loaded mRNA for CalpA are present in the early embryo (Emori and Saigo, 1994). CalpA presents a unique characteristic in that it displays a hydrophobic domain that may favor association to membranes (Theopold et al., 1995). Accordingly, CalpA is localized to the submembranous apical compartment in early syncytial-stage embryos (Emori and Saigo, 1994). We showed that CalpA knockdown (KD) increases protein levels of the IκB protein Cactus (Cact), resulting in altered NFκB pathway responses and patterning of the early embryo (Fontenele et al., 2009). These data indicate that calpains may perform a conserved role to regulate NFκB activity in vertebrates and invertebrates, thus motivating a more detailed investigation of their functional significance.

The Drosophila IκB protein Cact was first identified as a maternal-effect mutation required for dorsal–ventral (DV) patterning of the embryo (Schupbach and Wieschaus, 1989; Geisler et al., 1992). Later work by several groups showed that cact regulates NFκB activity during embryogenesis and innate immunity in response to Toll signals. Activation of the Toll pathway begins with binding of the Spätzle ligand to Toll transmembrane receptors. On receptor oligomerization, the adaptor proteins dMyD88 and Tube recruit the Pelle kinase to the plasma membrane (Belvin and Anderson, 1996; Sun et al., 2002, 2004; Marek and Kagan, 2012). Phosphorylation and degradation of Cact ensues, releasing NFκB-like proteins for nuclear translocation. In the embryo, Cact regulates nuclear translocation of the NFκB/Rel protein Dorsal (Dl) and activation/repression of target genes (for references see Moussian and Roth, 2005). In the immune system both Rel proteins Dl and Dif are regulated by Cact to control the response to fungi and Gram-positive bacteria (for references see Hoffmann, 2003).

The levels of Rel-complexed and free Cact are regulated by two proteolytic pathways, controlling responses to Toll activation. Whereas Toll receptor activation leads to phosphorylation, ubiquitination, and ultimately Cact proteasomal degradation, a second pathway for Cact degradation has been reported in the embryo, which involves phosphorylation by CKII (Liu et al., 1997; Packman et al., 1997). Different portions of the Cact molecule are targets for the Toll-dependent (Anderson et al., 1985; Hecht and Anderson, 1993; Roth et al., 1991; Shelton and Wasserman, 1993; Gillespie and Wasserman, 1994; Drier et al., 1999; Sun et al., 2004) and Toll-independent pathways (Belvin et al., 1995; Bergmann et al., 1996; Reach et al., 1996; Liu et al., 1997). Residues on the N-terminal portion are phosphorylated upon activation of the Toll pathway, whereas CKII phosphorylation of Ser residues located inside the C-terminal PEST domain primes Cact for degradation independent of Toll (Liu et al., 1997; Packman et al., 1997). The Cact PEST domain is also required for proteolysis by CalpA since levels of C-terminal deleted Cact are unchanged in presence of the protease (Fontenele et al., 2009). This pattern is similar to that proposed for vertebrate IκBα (Shumway et al., 1999; Shen et al., 2001), in which Toll signals lead to N-terminal phosphorylation followed by IκBα proteasomal degradation, and constitutive degradation depends on phosphorylation of residues inside the PEST domain. Moreover, the PEST domain is necessary and sufficient for IκB proteolysis by μ-calpain in vitro (Shumway et al., 1999). Here we produce C-terminal–tagged Cact forms that allow us to precipitate Cact that is not part of Rel complexes. Using these tools, we investigate how CalpA regulates Cact protein levels in vivo and discuss the action of CalpA to modulate Toll signals during embryogenesis and the innate immune response.

RESULTS

Cactus and Calpain A physically interact

Vertebrate calpains target IκB proteins for proteolytic cleavage. It has not been shown decisively, however, whether they target free or Rel-bound IκB. Furthermore, CalpA action decreases Cact levels in Drosophila, but it is unclear whether this action is direct. We developed a V5/His C-terminal–tagged CalpA (hereafter termed CalpA-V5) for inducible expression in S2 cells, allowing us to detect full-length as well as N-terminally cleaved CalpA, the latter indicative of autoproteolysis (Jekely and Friedrich, 1999). CalpA-V5 responds to an increase or decrease in calcium levels with a decrease or increase in CalpA-V5 protein levels, respectively (Figure 1, A and B). This is in agreement with a decrease in calpain levels after activation by calcium as a result of autoproteolysis and subsequent degradation (Jekely and Friedrich, 1999). In addition, on lowering available calcium via a 5-h ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid (EGTA) treatment, two CalpA-V5 bands appear on Western blots (Figure 1A). This suggests that the slow-migrating band is full-length CalpA-V5, whereas the fast-migrating band that migrates as the sole form in basal conditions (as dimethyl sulfoxide [DMSO]) is actually the N-terminal–truncated CalpA-V5. This would imply that most CalpA produced in S2 cells is rapidly cleaved. In agreement with our previous results showing that CalpA regulates Cact levels in embryos, CalpA-V5 expression lowers Cact levels. CalpA activation in the presence of ionomycin, which increases Ca2+, results in a further decrease in Cact protein (Figure 1, A and C).

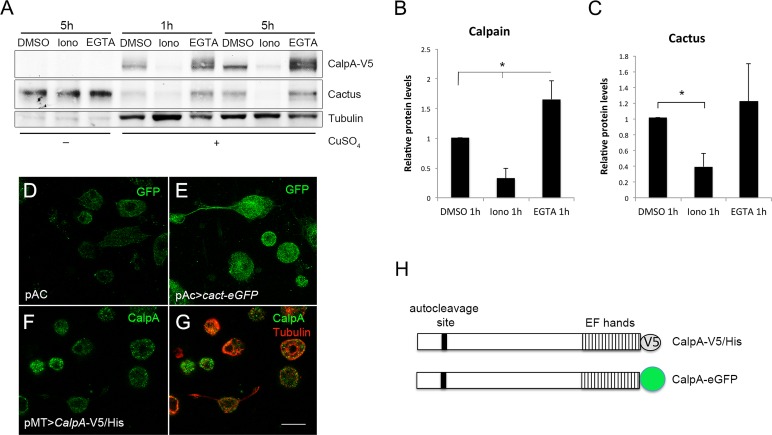

FIGURE 1:

Calpain A alters Cactus levels in S2 cells. (A) Western blot of samples from S2 cells transfected for 48 h with pMT-CalpA-V5. CalpA and endogenous Cact levels are shown before and after induction of the transgene with CuSO4. After 24 h of induction, cells were treated with 5 μM ionomycin (Iono), the calcium chelator EGTA (5 mM), or vehicle (DMSO) for 1 or 5 h. Tubulin was used as loading control. (B, C) Quantification shows that CalpA-V5 levels (B) change by increasing (Iono) or decreasing (EGTA) Ca2+. Cact levels (C) decrease significantly with ionomycin. Statistical significance defined by Student's t test, *p < 0.05. (D–G) Immunostaining for GFP (D, E) or V5 (F, G) in S2 cells transfected with (D) empty pAC vector, (E) pAC>cact-eGFP, and (F, G) pMT-CalpA-V5; Tubulin was used to reveal the cell outline. (H) Schematic of CalpA with C-terminal V5/His or GFP tag, site for autoproteolysis, and penta EF-hand Ca2+ binding region harboring the short hydrophobic domain. Scale bar (D–F), 10 μm.

Cact is a cytosolic protein that, in early embryogenesis, either is bound to Dl as part of a signaling complex or forms a dimer with Cact alone (Isoda and Nusslein-Volhard, 1994). Both Dl-bound (2Dl:1Cact) and unbound Cact (2Cact) may be phosphorylated at N-terminal Ser residues in response to Toll pathway activation (Bergmann et al., 1996; Reach et al., 1996; Fernandez et al., 2001). In agreement with subcellular localization studies, Cact and C-terminal green fluoresent protein (GFP)–tagged Cact (Cact-eGFP) are present in the cytosol of S2 cells (Figure 1E). CalpA-V5 is present in the cytosol; however, particulate distribution of CalpA-V5 is also observed (Figure 1, F and G). This may correspond to inner plasma membrane localization of CalpA, in agreement with enrichment of CalpA in the submembranous domain during embryogenesis (Emori and Saigo, 1994; Fontenele et al., 2009). Thus the effect of CalpA on Cact levels in S2 cells and embryos and the distribution of both proteins in the embryo support the notion that Cact may be a direct CalpA target.

To test this hypothesis, we performed coimmunoprecipitation (coIP) experiments using Cact-eGFP and CalpA-V5. With use of anti-GFP antisera, Cact-eGFP coimmunoprecipitates CalpA-V5, indicating that CalpA interacts physically with Cact in S2 cells (Figure 2A). On the other hand, Dl does not coimmunoprecipitate CalpA-V5 (Figure 2B), suggesting that an interaction between these proteins either does not exist or is too weak or transient to be detected by our methods.

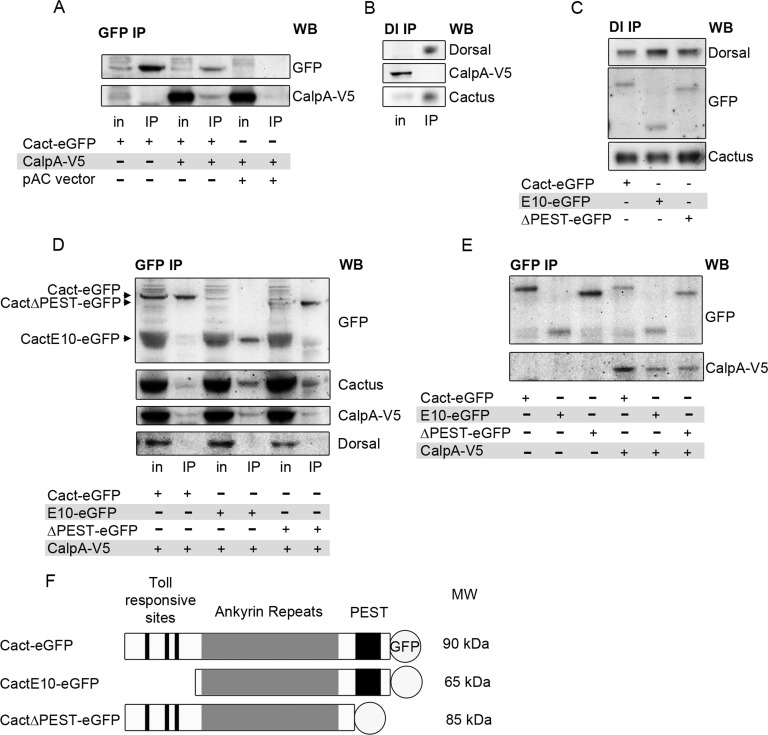

FIGURE 2:

Calpain binds Cactus. (A) Immunoprecipitation of Cact with anti-GFP antibodies. S2 cells were transfected with pMT-CalpA-V5 and pAC>cact-eGFP or pAC vector. On induction with CuSO4, whole-cell lysates show CalpA expression (in, input), which coimmunoprecipitates with Cact-eGFP (IP). (B) Using protein G–bound antibodies against Dl, endogenous Cact coimmunoprecipitates with Dl, but not CalpA. (C) Cells expressing N-terminal–deleted (E10-eGFP) or C-terminal–deleted (ΔPEST-eGFP) tagged Cact or full-length Cact-eGFP. All Cactus constructs coimmunoprecipitate with Dl. Western blot (WB) for GFP shows GFP constructs. Only the endogenous Cact region is shown in Cact WB. (D, E) Cells transfected with pMT-CalpA-V5 and pAC>cact-eGFP, pAC>cactE10-eGFP, or pAC>cactΔPEST-eGFP. All Cact constructs bind CalpA-V5, endogenous Cact, but not Dl in IPs using anti-GFP (D). (E) Comparison of IPs from cells expressing (+) or not expressing (–) CalpA-V5 shows that levels of Cact-eGFP and CactΔPEST-eGFP are reduced in the presence of CalpA. Cells were treated under identical conditions except for the presence or absence of CuSO4, and identical amounts were loaded on gels. (F) Graphic representation of GFP-tagged Cact constructs showing the region harboring Toll-responsive phosphorylation sites and sites for phosphorylation by Toll-independent signaling (PEST). MW denotes approximate size observed on SDS–PAGE.

The interaction between CalpA and Cact, but not Dl, suggests that CalpA may coimmunoprecipitate with Cact that is not complexed to Dl. Cact-eGFP displays several characteristics that indicate it forms functional complexes with Dl and simulates endogenous Cact function. First, it interacts with Dl in S2 cells, as it coimmunoprecipitates with Dl antisera (Figure 2C). Second, in nonreducing gels we observe an additional Dl complex in embryos expressing Cact-eGFP (Supplemental Figure S1A). The higher molecular weight is consistent with formation of a 2Dl:1Cact-eGFP complex. Finally, maternal expression of Cact-eGFP partially recovers a loss-of-function Cact phenotype and results in Cact-eGFP distribution that parallels endogenous Cact (Supplemental Figure S1, B and C). On the other hand, GFP antiserum does not coimmunoprecipitate Dl in S2 cells expressing Cact-eGFP constructs (Figure 2D). Earlier studies suggested that C-terminal Cact epitopes are buried inside 2Dl:1Cact complexes and thus are not recognized by antibodies against this portion of the molecule (Whalen and Steward, 1993). This may also explain why Cact-eGFP does not coimmunoprecipitate Dl (Figure 2D), although it does form trimeric complexes with Dl, similar to wild-type Cact (Supplemental Figure S1A). Therefore the presence of a C-terminal GFP tag in Cact favors immunoprecipitation of Cact that is not part of a complex with Dl. Accordingly, whereas Cact-eGFP does not coimmunoprecipitate Dl, it does coimmunoprecipitate endogenous Cact, suggesting it is able to form a dimer with nontagged Cact (Figure 2D). This Dl-independent Cact may constitute the free Cact pool, reported as target of constitutive degradation (Belvin et al., 1995; Bergmann et al., 1996; Liu et al., 1997).

The N-terminus and the C-terminal domains of Cact and IκBα harbor residues that are targets for Toll-dependent and constitutive degradation, respectively. To test whether the interaction between Cact and CalpA depends on these domains, we produced N-terminal–deleted (CactE10-eGFP) and C-terminal–deleted (CactΔPEST-eGFP) constructs. As shown for full-length Cact-eGFP, C- and N-terminal–truncated Cact also coimmunoprecipitates nontagged Cact but does not coimmunoprecipitate Dl (Figure 2D). This is easily seen in immunoprecipitates (IPs) for CactΔPEST-eGFP, for which an endogenous Cact band coimmunoprecipitates with CactΔPEST-eGFP. This is harder to interpret in IPs for CactE10-eGFP, since this truncated form migrates at the same position as endogenous Cact. Therefore the band identified as Cact in coIP with CactE10-eGFP may actually correspond to the truncated tagged plus the endogenous Cact molecules. On the basis of the increased protein amounts recognized by anti-Cact antisera as compared with IP for full-length Cact-eGFP, we infer that endogenous Cact coimmunoprecipitates with CactE10-eGFP. Of importance, truncated Cact coimmunoprecipitates CalpA-V5 (Figure 2, D and E). Owing to the fact that CactΔPEST-eGFP and CactE10-eGFP associate with wild-type Cact, however, it is unclear whether CalpA-V5 interacts directly with truncated Cact-eGFP or this association is established through endogenous full-length Cact. In summary, although it is unclear whether N- or C-terminal Cact domains are required for an interaction with CalpA, we show that Cact complexes harboring these truncated forms are still able to interact with this protease. Furthermore, Dl coimmunoprecipitates truncated Cact. This indicates that truncated Cact-eGFP is also able to form a complex with Dl, in agreement with the literature (Belvin et al., 1995; Bergmann et al., 1996; Reach et al., 1996; Liu et al., 1997).

These results provide evidence that Cact associates with CalpA and that CalpA targets Cact that is not complexed to Dl, thus free Cact.

Calpain A generates a C-terminal–truncated Cactus fragment devoid of Toll-responsive sequences

Calpains were first described as Ca2+-dependent enzymes with degradation functions. However, more recent analysis shows that calpains cleave their substrates in a limited number of sites, often resulting in a modification of their activity. For this reason they are now termed modulatory proteases (Sorimachi et al., 2011). To address whether CalpA cleaves Cact in a limited manner to modulate its activity, we first searched for evidence of Cact truncated forms. Maternal expression of cact-eGFP generates, in addition to full-length Cact-eGFP (90 kDa), a smaller, 64-kDa fragment. This fragment migrates slightly faster than CactE10-eGFP and thus lacks an N-terminal portion of the molecule (Figure 3A). This pattern is observed in S2 cells as well as in blastoderm embryos, indicating that the mechanism that generates these fragments is present in both contexts. Furthermore, PEST-deleted Cact also migrates as a full-length and a truncated form, with the truncated form slightly smaller that CactE10-eGFP, consistent with absence of the PEST domain (Figure 3A).

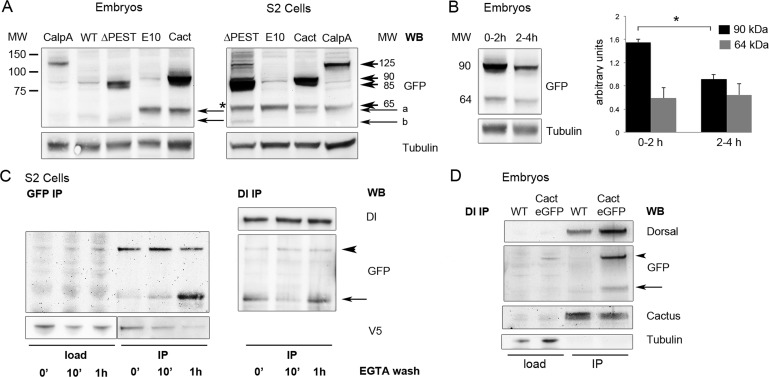

FIGURE 3:

C-terminal Cactus fragments are generated by the action of CalpA and are present in Dl complexes. (A) C-terminal, GFP-tagged CalpA and Cact constructs are visualized in 0- to 2-h-old embryos and in S2 cells by Western blot. Arrowheads indicate full-length tagged proteins (125, 90, 85, and 65 kDa for CalpA-eGFP, Cact-eGFP, CactΔPEST-eGFP, and CactE10-eGFP respectively), and arrows indicate C-terminal fragments (a for Cact-eGFP, b for CactΔPEST-eGFP fragments). Note that the Cact-eGFP fragment migrates slightly faster than CactE10-eGFP. Asterisk denotes nonspecific band detected by the anti-GFP antibody. Tubulin was used as loading control. (B) Analysis of Cact-eGFP protein over time. Embryos containing six copies of maternally driven Cact-eGFP constructs were collected at 2-h intervals. Full-length Cact-eGFP (90 kDa) decreases over time at a faster rate than C-terminal fragments (64 kDa). Bars represent Cact-eGFP relative to tubulin protein levels. Statistical significance defined by Student's t test, *p < 0.05. (C) CalpA generates Cact fragments. To attain high levels of Cact-eGFP expression, S2 cells were transfected with pT>cact-eGFP, Actin-Gal4, and pMT>CalpA-V5/His. After 24 h in the presence of CuSO4 to induce CalpA expression, cells were treated 5 h with EGTA, subsequently washed with fresh medium for the times indicated, and submitted to immunoprecipitation for anti-GFP. Arrowhead indicates full-length Cact-eGFP, which decreases over time (GFP IP, left), whereas the amount of a Cact-eGFP fragment (arrow) increases. Equivalent amounts of the same samples submitted to GFP IP were used for IP with anti-Dl (Dl IP, right). Both full-length and Cact-eGFP fragments coimmunoprecipitate with Dl. The load portion of the anti-V5 blot was underexposed to reveal that the decrease in CalpA-V5 in the GFP IP lanes after 1 h EGTA wash is not due to a smaller protein input for IP. (D) Lysates from wild-type (WT) embryos or embryos expressing six copies of cact-eGFP were immunoprecipitated with anti-Dl. Endogenous Cact (Cactus), as well as Cact-eGFP (GFP) full-length (arrowhead) and C-terminal fragments (arrow), coimmunoprecipitate with Dl.

In the early embryo cact function depends on maternal expression, with decreasing maternal cact replaced by zygotic cact as gastrulation progresses (Kidd, 1992). Accordingly, expression of cact-eGFP under a maternal promoter generates protein that is maternally provided and decreases in abundance as the embryo ages (Figure 3B). However, N-terminal–truncated Cact-eGFP levels do not decrease to the same extent, suggesting that the Cact-eGFP fragment (64 kDa) is more stable than the full-length molecule. Classic cact mutants that produce N-terminal–truncated Cact, termed cact[E10] and cact[BQ] (Bergmann et al., 1996; Roth, 2001), do not respond to Toll signals and present greater stability in cells and embryos, in agreement with the foregoing interpretation.

Next we asked whether Cact C-terminal fragments were generated by the action of CalpA. We expressed CalpA-V5 and cact-eGFP in S2 cells and assayed the levels of Cact and CalpA as a function of time in the presence of Ca+2. In these conditions we observe that full-length Cact levels decrease with time after washing out the Ca+2 chelator EGTA. We find a corresponding increase in the levels of 64-kDa, N-terminal–deleted Cact (arrow in Figure 3C). CalpA levels that coimmunoprecipitate with Cact-eGFP also decrease with time (Figure 3C), indicating that CalpA is released from this interaction after Cact cleavage. This behavior is consistent with the action of CalpA, as autolysis is followed by termination of activity (Friedrich et al., 2004). Therefore we conclude that CalpA is able to cleave Cact and generate a C-terminal fragment that corresponds in size to fragments present in vivo.

Because Cact exists either as a dimer or bound to two Dl molecules, we asked whether the Cact fragment generated by the action of CalpA is able to interact with Dl. Part of the same lysate used in the previous experiment was used to test whether the fragments generated by CalpA coimmunoprecipitate with Dl antisera. Indeed, coIP with Dl reveals that Cact-eGFP C-terminal fragments are able to interact with Dl (Figure 3C). This result was unexpected, considering the previous assay showing that CalpA coimmunoprecipitates with Cact but not Dl and is therefore unlikely to cleave Cact inside the complex. One way to explain this result is to propose that Cact fragments generated by CalpA are incorporated into 2Dl:1Cact complexes, exchanging with full-length Cact. Of interest, a Cact-eGFP fragment of similar size is observed in vivo to coimmunoprecipitate with Dl (Figure 3D). Fragments from endogenous Cact that correspond in size to the deletion observed for Cact-eGFP also coimmunoprecipitate with Dl in S2 cells and embryos (Supplemental Figure S2). Thus C-terminal Cact fragments generated by CalpA are likely produced in vivo and predicted to regulate Toll-responsive 2Dl:1Cact complexes.

To unambiguously identify the 64-kDa fragment as an N-terminally deleted Cact-eGFP fragment generated by CalpA-V5 in S2 cells (as in Figure 3C), we excised this band from gels and analyzed it by mass spectrometry. Identification of unique peptides for Cact and GFP confirms that this band is indeed a Cact-eGFP fragment. Furthermore, no sequences before amino acid residue 149 were detected, conforming with the size of the fragment and the interpretation that Cact cleaved by CalpA lacks N-terminal sequences responsive to Toll (Supplemental Figure S3). Two high-probability cleavage sites in Cactus are predicted after the Toll-responsive sequences, at positions 145 and 153 (as defined by sequence analysis at Calpain for Modulatory Proteolysis Database [http://calpain.org]; duVerle et al., 2010). The cact[E10] and cact[BQ] mutants encode proteins that start at position 145 in full-length Cact (Bergmann et al., 1996). Therefore Cact fragments generated by CalpA proteolysis may share properties similar to these gain-of-function alleles. It is interesting to note that porcine m-calpain cleaves human IκBα in vitro, deleting sequences for Toll responsiveness (Schaecher et al., 2004) and thus suggesting a conserved mechanism for calpain action.

Quantifying the effect of CalpA on the embryonic DV axis

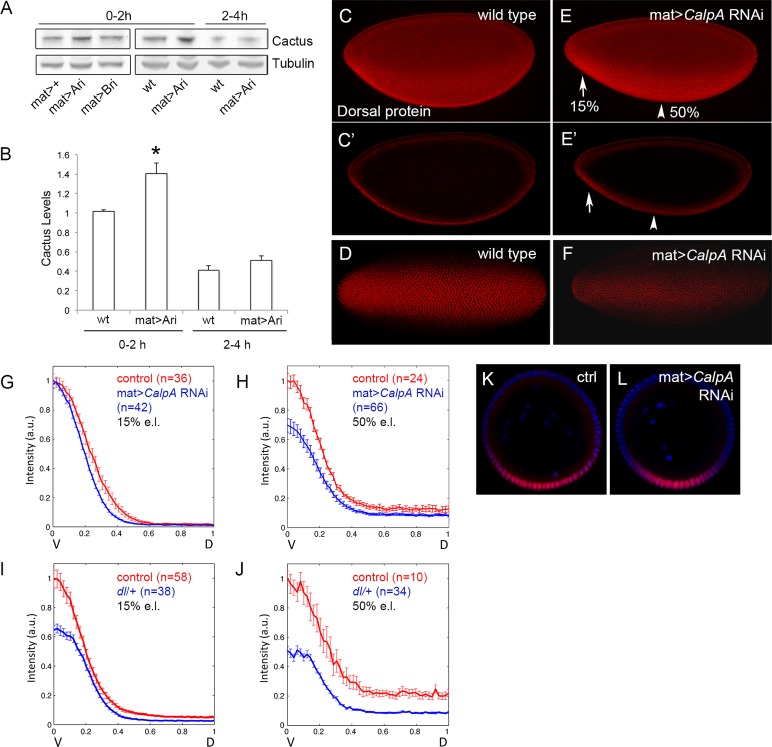

The interactions described between CalpA and Cact suggest that CalpA may display fundamental roles in regulating NFκB activity in vivo. The best characterized roles for cact are during embryonic DV patterning and in the systemic immune response. CalpA is expressed maternally, generating mRNA that is loaded into the oocyte and detected during early embryogenesis (Emori and Saigo, 1994; Theopold et al., 1995). We previously showed that injection of double-stranded RNA for CalpA altered Cact levels, Dl distribution, and Dl target gene expression in the early embryo (Fontenele et al., 2009). To quantify the effect of CalpA on the Dl gradient, we performed KD using UAS-CalpA RNA interference (RNAi) lines (Transgenic RNAi Project [Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA], pValium10) driven by a maternal GAL4 driver, a condition that reduces variability compared with double-strand RNA injections. A 50% reduction in CalpA mRNA levels was observed, leading to a 1.5- to 2.0-fold increase in the levels of full-length Cact (Figure 4, A and B). This effect is specific to CalpA KD, but not CalpB KD, in syncytial-stage embryos (0- to 2-h development). As a result, the nuclear Dl gradient is reduced, especially in the middle of the embryo (Figure 4, C–F). CalpA KD also reduces the ventral twist and snail expression domains, targets of activation by high levels of nuclear Dl (data not shown; Fontenele et al., 2009). We quantified the effect of CalpA KD on the Dl gradient by measuring the gradient in fixed embryo optical cross sections. It was shown that the wild-type Dl gradient increases in amplitude with developmental time (Kanodia et al., 2009; Liberman et al., 2009) and varies in width along the anterior–posterior axis (Kim et al., 2011; Reeves et al., 2012). CalpA KD alters the shape of the Dl gradient, reducing the amplitude of the gradient at 50% egg length (e.l.) in cycle 14 embryos. The shape of the gradient is also altered at 15% e.l., although the amplitude is not reduced as at 50% e.l. (Figure 4, G, H, K, and L). These alterations are consistent with the decrease in twist and snail domains, as well as with modifications in the size of lateral neuroectodermal territories previously reported (Fontenele et al., 2009, and data not shown). Of importance, basal (dorsal region) Dl levels are unaltered at any position under CalpA KD, unlike the reduction seen by lowering the dose of the dl gene (Figure 4, I and J). This indicates that the visible effects of CalpA on the Dl gradient are restricted to ventrolateral regions where the Toll receptor is active instead of regulating the total amount of Dl along the DV axis, which is capable of shuttling between nuclei and cytoplasm (DeLotto et al., 2007).

FIGURE 4:

Calpain A KD alters the format of the Dorsal gradient during embryogenesis. (A) Western blot analysis reveals that CalpA KD with the maternal tub67Gal4 driver (mat>Ari) increases the levels of Cact protein in blastoderm embryos (0–2 h) but has no effect after gastrulation (2–4 h). CalpB KD has no effect (mat>Bri). Tubulin was used as loading control. (B) Quantification of protein bands shows a small but significant increase in the levels of Cact in 0- to 2-h embryos (*p < 0.05; Student's t test). (C–F) Dl gradient in wild-type (C, D) and CalpA KD (E, F) shows a reduction in the Dl gradient, especially at 50% embryo length (arrowhead), as seen in the lateral projected Z-sections (C, E) and in cross-sections (C′, E′) of the same embryos. Embryos in ventral view (D, F) show a narrow domain of high Dl in the KD (F). Anterior is left, posterior is right. Dorsal is up in C and E. (G–L) Embryos were cut transversely, and the nuclear Dl gradient was quantified at 15% (G, I) or 50% (H, J) e.l. compared with control embryos (Histone-GFP) stained concomitantly. The x-axis represents the space from the ventralmost point (V; x = 0) to the dorsalmost point (D; x = 1). The y-axis represents the intensity of nuclear Dl, where the gradient was normalized with respect to the control Dl gradient. Error bars correspond to the SEM. (G) At 15% e.l. (left) the format of the Dl gradient is modified in embryos from the CalpA RNAi (in blue) compared with control embryos (red). Basal Dl levels in dorsal regions are unchanged. At 50% e.l. (H) the amplitude of the gradient is also decreased in CalpA RNAi. (I, J) A reduction in the dose of dl (blue) results in a decrease in the amplitude of the Dl gradient as well as in the basal Dl levels at 15% e.l. (I) and is more prominent at 50% e.l. (J). Here n corresponds to the number of gradients analyzed. (K, L) Optical sections at 15% e.l. to illustrate the Dl gradient in control (K) and CalpA RNAi (L) embryos. Plots in G–J are statistically significant based on Student's t test (p < 0.05).

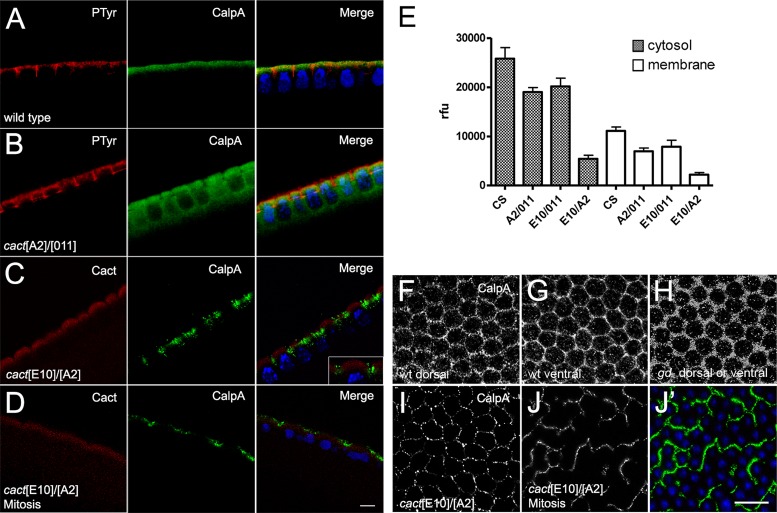

CalpA protein is apically enriched in the submembranous cytoplasm of the embryo syncytium (Emori and Saigo, 1994; Fontenele et al., 2009). It displays a dynamic pattern: at each mitotic division CalpA is evenly redistributed in the cytoplasm (Supplemental Figure S4). We observed that apical CalpA distribution depends on Cact (Fontenele et al., 2009). In cact loss-of-function mutants apical restriction is lost (Figure 5, A and B; Fontenele et al., 2009), whereas in cact[E10] mutants CalpA is distributed as patches close to the membrane (Figure 5, C and I) and does not redistribute during mitosis (Figure 5, D and J). In both conditions calpain activity, measured with a fluorescent substrate, is decreased (Figure 5E). These results agree with the physical interaction demonstrated earlier between these proteins.

FIGURE 5:

The cactus[E10] gain-of-function mutant alters CalpA distribution and activity. (A) Wild-type syncytial blastoderm embryo showing endogenous CalpA beneath the plasma membrane, marked with anti-phosphotyrosine antisera. (B) In loss-of-function cact mutants CalpA is diffuse in the cytoplasm. (C, D) In a gain-of-function cact mutant (cact[E10]/cact[A2] mothers), CalpA distribution is patchy during interphase (C) and remains so during mitosis (D). CalpA in green and Hoechst nuclear stain in blue; Phosphotyrosine in red in A and B, and Cact in red in C and D. (E) Calpain activity decreases in loss-of-function (cact[A2]/cact[011] mothers) and gain-of-function (cact[E10]/cact[011] and cact[E10]/cact[A2] mothers) cact mutants as compared with wild-type (CS). Values are statistically significant based on one-way analysis of variance (p < 0.05). The decrease in activity in membrane-enriched fractions does not result from a redistribution to the cytosol. (F–J) CalpA distribution in sagittal view of (F) dorsal and (G) ventral region of a wild-type embryo, (H) embryo from a gd-/gd- mother, and (I, J) embryos from cact[E10]/cact[A2] mothers during interphase (I) or mitosis (J, J′). Nuclei are blue in J′ to reveal detail in CalpA (green) distribution. Scale bars, 5 μm (A–D), 10 μm (F–J).

The dependence of CalpA activity on cact suggests that it may be regulated by Toll signals. Calpain activity is unchanged in the absence of Toll signals, however, such as in embryos from gd- mothers (gastrulation defective) or by unpatterned Toll activation, such as embryos from Tl[10B] mothers (gain-of-function Toll allele; Fontenele et al., 2009). Apical enrichment is also maintained in these mutant conditions. On the other hand, apical CalpA distribution is slightly altered, depending on the level of Toll signaling. In embryos that lack upstream Toll signals (from gd- mothers) the CalpA mesh-like distribution is not as “tight” as in ventral regions of a wild-type embryo where Toll signals are active (Figure 5, F–H). Of interest, CalpA distribution at the dorsal side of wild-type embryos is more homogeneous than in the ventral region (Figure 5, F and G). Therefore upstream elements of the Toll pathway do not seem to affect the levels of CalpA activity or CalpA apical enrichment, although they do influence CalpA distribution inside the submembranous compartment.

CalpA regulates Cactus function in the immune system

In addition to embryonic DV patterning, Cact plays a fundamental role in the immune system. Innate immunity in Drosophila involves systemic and cellular responses (Hoffmann, 2003). During larval stages the fat body—invertebrate structure functionally equivalent to the vertebrate liver—controls the systemic response to infection by activating the Toll and Imd pathways (Nicolas et al., 1998; Manfruelli et al., 1999; De Gregorio et al., 2002). Infection by fungi and Gram-positive bacteria activates the Toll pathway, leading to nuclear translocation of the Rel proteins Dl and Dif (Ip et al., 1993; Lemaitre et al., 1996, 1997; Meng et al., 1999; Michel et al., 2001; Ligoxygakis et al., 2002; Rutschmann et al., 2002; Tauszig-Delamasure et al., 2002; Tanji et al., 2010). Gram-negative bacterial infection activates the Imd pathway and nuclear translocation of Relish (Lemaitre et al., 1995; Georgel et al., 2001; Lu et al., 2001; Choe et al., 2002).

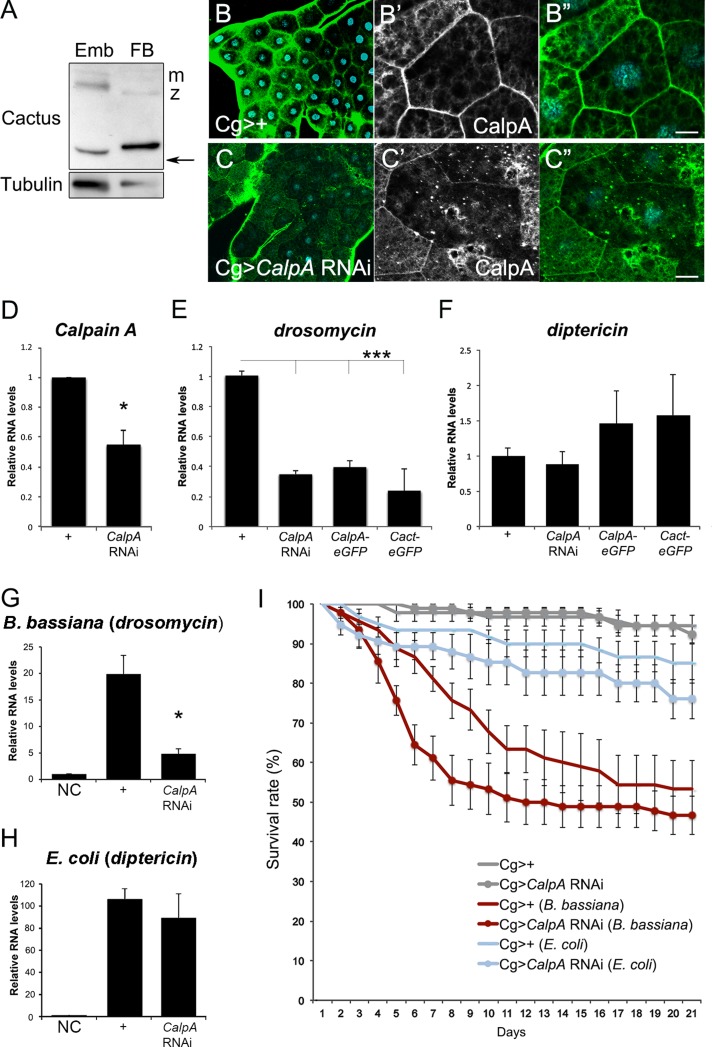

We investigated whether CalpA regulates Cact function in the fat body. Two endogenous Cact bands are detected in the fat body, the smaller corresponding in size to a deletion of the Toll-responsive N-terminal region (Figure 6A). This suggests that Cact fragments generated by CalpA may play a role in the immune system as well as in the embryo. CalpA protein is evenly distributed throughout the larval fat body tissue (Figure 6B). CalpA KD using the Cg-Gal4 driver induces a ∼60% reduction in CalpA mRNA levels (Figure 6D). As a result, irregularly decreased CalpA staining is seen in fat body cells (Figure 6, B and C). Both CalpA loss and gain of function reduce the basal drosomycin mRNA levels, a well-established target of Toll pathway activation (Figure 6E). In contrast, no significant alteration was observed on diptericin mRNA levels, reflecting the absence of an effect on the Imd pathway (Figure 6F). Accordingly, drosomycin mRNA levels are decreased in CalpA KD larvae challenged with spores from the fungus Beauveria bassiana (Figure 6G), whereas the response to Gram-negative Escherichia coli is unchanged (Figure 6H). This behavior is repeated in the adult. CalpA KD adults challenged with B. bassiana display a reduced survival rate compared with controls (Figure 6I). Therefore CalpA functions in the larval and adult immune system to modulate Toll pathway–induced responses.

FIGURE 6:

CalpA regulates Toll pathway responses in the fat body. (A) Cact protein in larval fat body (FB) and 0- to 2-h embryos (Emb). Note the maternal (m) and zygotic (z) full-length bands and the truncated (arrow) forms. Tubulin was used as loading control. (B, C) CalpA protein staining (green) in control (B; Cg-GAL4>+), and CalpA KD (C; Cg-GAL4>UAS-Dicer2; UAS-CalpA RNAi) larval fat body. The KD is more effective in some cells than others; however, decreased submembranous immunoreactivity is observed in most cells, as shown in high magnification (B′′, B′′′; C′′, C′′′). (D) qRT-PCR shows 50% reduction in CalpA mRNA levels in the CalpA KD. (E–H) qRT-PCR for drosomycin (E, G) and diptericin (F, H) in control larvae (Cg-GAL4>+) or larvae expressing UAS-Dicer2; UAS-CalpA RNAi, UAS-CalpA-eGFP, or UAS-cact-eGFP under the control of Cg-GAL4. Basal (E, F) drosomycin levels are significantly decreased by alterations in CalpA and cact. On challenge (G) with B. bassiana, drosomycin levels decrease in the CalpA KD relative to control Cg-GAL4>+. No difference is observed upon challenge with E. coli (H). Statistical significance defined by Student's t test, *p < 0.05. (I) Viability in B. bassiana–challenged but not E. coli–challenged Cg>CalpA RNAi adult flies is significantly decreased relative to Cg>+ controls. Statistical significance assigned by log-rank (Mantel–Cox) test for the first 15 d and by Gehan–Breslow–Wilcoxon test for the entire period, p < 0.05. Scale bar, 10 μm (B′′, C′′). NC = no challenge.

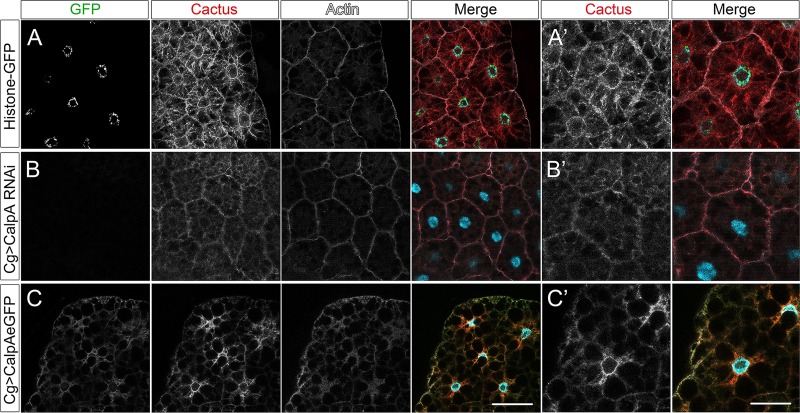

Cact distribution in the large cells of the fat body is modified by changes in CalpA levels (Figure 7). In wild-type cells most Cact protein is cytoplasmic; however, staining close to the plasma membrane is also observed, colocalizing with filamentous actin (Figure 7A). This may reflect Cact protein in close proximity to the Toll signaling complexes, whereas cytoplasmic Cact may reflect protein released from these complexes and/or in transit to the membrane. Strikingly, upon CalpA KD, cytoplasmic Cact decreases greatly and submembranous distribution is maintained (Figure 7B). Conversely, CalpA overexpression results in a general decrease in Cact levels but especially in loss of Cact at the membrane (Figure 7C). A decrease in filamentous actin is also seen in this condition.

FIGURE 7:

CalpA modifies Cactus distribution in the larval fat body. (A) Control (Cg-GAL4>+), (B) CalpA KD (Cg-GAL4>UAS-Dicer2; UAS-CalpA RNAi), and (C) CalpA-eGFP–overexpressing (Cg-GAL4>UAS-CalpA-eGFP) fat body cells showing Histone-GFP (green in A) or CalpA-eGFP (green in B, C), Cact (red), phalloidin (white), and Hoechst nuclear stain (blue) in all merged images. CalpA KD induces decreased Cact in the cytoplasm and maintains submembranous Cactus, which colocalizes with filamentous actin, whereas CalpA overexpression induces the inverse effect. (A′–C′) High magnification of fat body cells from A–C. Scale bars, 50 μm (A–C), 25 μm (A′–C′).

The decrease in basal drosomycin mRNA levels upon CalpA KD correlates with the decrease in cytoplasmic Cact and suggests a decrease in NFκB activation. This conforms with the interpretation that cytoplasmic Cact harbors a signaling component (Wu and Anderson, 1998). The similar decrease in drosomycin mRNA levels upon CalpA overexpression, however, is puzzling. If CalpA acts solely by stimulating Cact degradation, one would expect that CalpA overexpression, by decreasing total Cact, should result in greater NFκB activity. One way to interpret these results is to propose that CalpA regulates Cact availability to participate in Toll signaling complexes. In this scenario CalpA KD would inhibit the release of Cact to participate in Toll signaling complexes with Dl and Dif, keeping it unavailable at the submembranous compartment. On CalpA overexpression, the absence of Cact at the membrane, available to renew Toll-responsive complexes, would explain the low expression levels of the NFκB target drosomycin. Thus a correct balance of CalpA activity would be required to favor Toll responses. Alternatively, low drosomycin under CalpA overexpression may result from high levels of nonresponsive CactE10 fragments, inhibiting Toll signals, or from abnormalities in the cytoskeletal array that keeps components of the Toll pathway in place for signaling. Regardless of the mechanism, these results demonstrate that CalpA alters Cact function in the immune system by affecting Toll pathway activity.

DISCUSSION

CalpA binds and cleaves Cactus

Combined with our previous results, we showed that CalpA regulates Cact and that interfering with CalpA activity results in phenotypes associated with the NFκB pathway in the embryo and fat body. It was an open question, however, whether Cact is a direct target of CalpA activity in vivo. The present results show that CalpA and Cact physically interact in S2 cells. In addition, N-terminal–deleted Cactus is generated by the action of CalpA. This deletion occurs in the proximity of a predicted CalpA cleavage site. Finally, we observe increased levels of truncated Cact upon an increase in Ca2+ levels in the presence of CalpA. Thus, although we have not completely ruled out the existence of an intermediary protein in this process, data presented here support the hypothesis that Cact is a direct CalpA target.

The action of vertebrate μ-calpain to interact with and cleave IκBα depends on a C-terminal PEST sequence (Shumway et al., 1999; Shen et al., 2001). It is unclear in Drosophila which sequences in Cact are required to interact with CalpA, since truncated Cact is complexed to full-length Cact. CalpA mRNA injections that decrease the levels of full-length Cact are unable to decrease PEST-deleted Cact (Fontenele et al., 2009), arguing that CalpA does require the Cact PEST domain for cleavage. We observe, however, a C-terminal CactΔPEST-eGFP fragment in vivo that corresponds in size to a deletion potentially generated by CalpA (Figure 3A). To resolve this conflict, one can suggest that CalpA has higher affinity for full-length than PEST-deleted Cact. Additional studies are necessary to test this prediction. Conversely, the Cact N-terminus may be required for CalpA action. The amount of CactE10-eGFP that IPs with anti-GFP sera is unaltered in the presence or absence of CalpA-V5 (Figure 2), and CalpA mRNA injections do not significantly alter the levels of injected CactE10 (Fontenele et al., 2009). CalpA action releases the Cact N-terminus, likely terminating the interaction between the two proteins. Thus N-terminal–deleted Cact may not be a CalpA substrate. In accordance with this interpretation, CalpA does not colocalize with Cact in cact[E10]/cact[A2] embryos (Figure 5C).

Cactus regulates CalpA activity and localization

The calcium requirement for calpain activity in vitro is much greater than that observed in vivo. Thus it was suggested that the proximity to substrates and/or membranes may lower the calcium concentration required for activation (Friedrich et al., 2004). The proximity of CalpA to the Cact substrate in the apical submembranous compartment may allow activation in spite of low Ca2+ concentrations. In fact, the decrease in calpain activity in cact– embryos shows that Cact is essential not only for localization but also for CalpA activity (Fontenele et al., 2009; present results). Before mitosis an apical calcium wave passes through the embryo starting at the poles, triggering nuclear divisions in the embryonic syncytium (Foe and Alberts, 1983). CalpA diffuses into the cytoplasm during mitosis, likely in response to this wave. Of interest, in cact[E10]/cact[A2] embryos CalpA remains membrane restricted and calpain activity is low, indicating that CalpA redistribution to the cytoplasm requires full-length Cact. Therefore a likely scenario is that during interphase Cact provides the substrate proximity for CalpA activity in the presence of low Ca2+. Cact also restricts CalpA distribution and allows it to sense the apical calcium wave during mitosis, followed by cytoplasmic redistribution of the protease. Thus it is tempting to speculate that Cact regulates and is regulated by CalpA. Others have suggested a similar interplay between calpain 2 and its substrate Fak in adhesion dynamics (Chan et al., 2010).

CalpA targets free Cact

In vertebrate cells IκBα functions as the primary regulator of NFκB. To ensure proper NFκB activity, degradation/turnover of free and NFκB-associated IκBα must be tightly regulated in basal as well as in stimulated conditions. Phosphorylation by IKKs leads to signal-dependent degradation of free and bound IκBα, and CKII activity induces IκBα degradation under basal conditions (Han et al., 1999; Shumway et al., 1999; Shen et al., 2001). Pando and Verma (2000), however, report that C-terminal CKII phosphorylation targets both free and NFκB-associated IκBα and contributes to NFκB-associated IκBα signal-dependent degradation. Whereas the IKK-independent degradation constant for free IκBα is 2000 times greater than for NFκB-associated IκBα, free IκBα degradation is a major determinant of constitutive and signal-responsive NFκB activity (O'Dea et al., 2007).

In Drosophila Cact exists as free and NFκB-bound forms. During embryogenesis Cact forms two different complexes: one composed of Cact only and another bound to a Dl dimer (Isoda and Nusslein-Volhard, 1994). The complex with Dl is part of the signaling module that responds to Toll activation. On Cact proteasomal degradation in response to Toll, the Dl dimer is released to enter the nucleus (Moussian and Roth, 2005). The Cact dimer or “free Cact” is also able to respond to Toll signals since it is subject to Toll-dependent degradation in the ventral region of dl– embryos (Belvin et al., 1995; Bergmann et al., 1996). In addition, free Cact is subject to Toll-independent degradation to maintain low levels of Cact in the absence of Dl. It was proposed this ensures that free Cact does not titrate out Toll signals, allowing a sensitive response (Bergmann et al., 1996; Liu et al., 1997). In the fat body Cact interacts with both Dl and Dif but may also exist in a Rel-free form (Nicolas et al., 1998; Wu and Anderson, 1998; Manfruelli et al., 1999). Although it seems clear that modifying the amount of free Cact alters the Dl gradient, its physiological significance is elusive.

Our data are consistent with CalpA interacting with a Cact pool that is not bound to Dl, constituting free Cact. Because CalpA KDs result in significant effects on ventrolateral regions of the embryonic Dl gradient, this supports the hypothesis that by regulating free Cact Toll responses are regulated. More than decreasing total levels of free Cact by degradation, however, CalpA generates truncated Cact that is more stable than the full-length form. These fragments lack Toll-responsive sequences, implying that they are not degraded in response to Toll and thus display activity that is different from full-length Cact. We provide evidence that Cact fragments are generated in vivo, both during embryogenesis and in the larval fat body. Of importance, C-terminal Cact fragments coimmunoprecipitate with Dl in vivo, indicating that CalpA regulates how free Cact is incorporated into signaling complexes to alter signals downstream of Toll. CalpA KD result in a modest (1.5- to 2-fold) increase in the levels of full-length Cact. A twofold increase in Cact may fall into the limits not predicted to result in an embryonic phenotype, whereas one dose of the cact[E10] allele is enough to produce 30% of weakly dorsalized embryos (Govind et al., 1993). Thus the effect of CalpA KD on the Dl gradient may result mainly from an imbalance of C-terminal Cact (CactE10) fragments generated by the protease. In vertebrates, IκB fragments generated by the action of calpains have been detected as intermediates in the degradation process (Han et al., 1999; Schaecher et al., 2004; Li et al., 2010). It will be interesting to investigate how truncated IκB functions to regulate Toll signals during the vertebrate immune response.

Contribution of CalpA to Toll responses

The enrichment of CalpA at the plasma membrane is consistent with a role in the regulation of signaling complexes. Recent data implicate calpains in the regulation of transmembrane receptors and their downstream signaling components. For instance, calpains-1 and -2 cleave the TRPC5 receptor, leading to neuronal growth cone collapse (Kaczmarek et al., 2012). Conversely, m-calpain stabilizes acetylcholine receptor clusters present at the neuromuscular junction (Chen et al., 2007), and μ-calpain cleaves β-catenin associated with membrane receptors (Lade et al., 2012). Curiously, CalpA distribution responds to the formation of Toll signaling complexes. The mesh-like submembranous CalpA array present in ventral regions of the embryos is modified in the absence of an active Toll ligand (embryos from gd- mothers). Enrichment of CalpA and general calpain activity at the membrane are not modified under this condition, unlike cact– embryos. Thus Toll signals are not required for CalpA activity. The redistribution of CalpA in response to Toll signals, however, suggests that this protease interacts with some part of the Toll signaling complex.

Although Cact is a cytosolic protein, assembly of the Toll signaling complex takes place at the membrane. It has been suggested that upon ligand binding, Toll receptors undergo homodimerization. As a consequence, the sorting adaptor MyD88 that binds Tube through its Death Domain recruits this complex to Toll. Subsequent binding of the kinase Pelle to the MyD88-Tube complex promotes Pelle activation, leading to phosphorylation and proteasomal degradation of Cact (Belvin and Anderson, 1996; Towb et al., 1998; Schiffmann et al., 1999; Horng and Medzhitov, 2001; Sun et al., 2002, 2004; Charatsi et al., 2003; Moncrieffe et al., 2008; Marek and Kagan, 2012). Two reports suggest that Drosophila Toll signaling requires endocytosis (Huang et al., 2010; Lund et al., 2010). Recent evidence, however, supports the notion that at least the initial steps in Toll signaling take place at the plasma membrane (Sun et al., 2002, 2004; Marek and Kagan, 2012). Considering the localization of CalpA and its effects in modifying Cact and signaling through Toll, it is possible that CalpA action is also initiated at the plasma membrane.

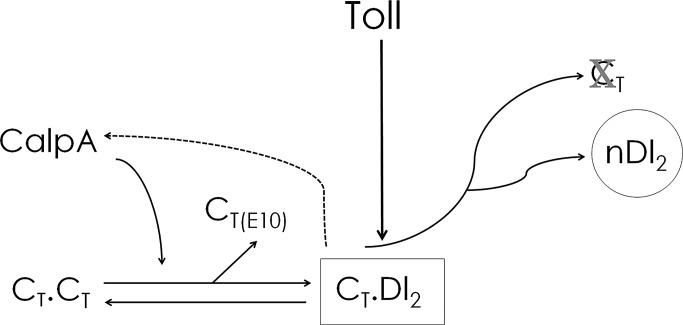

In view of the data presented here and evidence from the literature that calpain proteases regulate the composition and turnover of signaling complexes (Yuan et al., 1997; Li and Iyengar, 2002; Calle et al., 2006; de Thonel et al., 2010), we propose a model of CalpA function to regulate IκB elements and Toll signals in Drosophila (Figure 8): Cact binds CalpA in the submembranous cytoplasm as a complex (2Cact) devoid of Dl. Cleavage by CalpA liberates Cact from this complex, either as full-length or N-terminal–deleted Cact, allowing these IκB molecules to incorporate into the signaling complex with Dl (2Dl:1Cact). Newly incorporated full-length Cact responds to Toll and suffers degradation, liberating more Dl for nuclear translocation. Because the action of CalpA is to favor Toll signals in the embryo and fat body, this mechanism could potentially be used to replenish the downstream elements for Toll signaling (with full-length Cact) and/or terminate the signal (with truncated Cact devoid of Toll-responsive sequences), allowing new signaling complexes to form. In this scenario CalpA action on free Cact would help to sustain Toll signals over time or provide precision to NFκB responses. Future quantitative analysis and modeling will be fundamental to distinguishing between these possibilities.

FIGURE 8:

Model for the action of CalpA in modifying Toll signals. On the basis of a reduction of the Dl gradient in the embryo and the reduced expression of Dl target genes in the embryo and fat body upon CalpA KD, we propose a model for the action of CalpA to increase signaling through Toll: CalpA targets free Cact (CT⋅CT), releasing protein, which is incorporated into a complex with Dl (CT⋅Dl2). This complex responds to Toll signals, leading to Cact degradation and nuclear translocation of Dl (nDl2). In the process of releasing free Cact, C-terminal Cact fragments are produced (CT[E10]). Because Calpain activity is reduced in cact loss of function and CalpA distribution is altered by Toll signals, the model incorporates a positive feedback loop from Toll-responsive Cact:2Dl complexes (CT⋅Dl2, dashed arrow). Although not depicted, Cact fragments (CT[E10]) are also able to incorporate into a complex with Dl. Variations in the relative amount of full-length to truncated Cact may differentially affect Dl nuclear translocation.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Fly stocks and genetics

Lines used in this study were as follows: loss-of-function cact[A2] and cact[011], generously provided by Steve Wasserman (University of California, San Diego); and gain-of-function cact[E10] and gd[7], obtained from the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center (Indiana University, Bloomington, IN). The Cg-GAL4 driver line used in this study was described previously to drive expression in the larval and adult fat body (Asha et al., 2003). All KDs were induced in the presence of UAS-Dicer2, obtained from the Bloomington Stock Center. UAS-CalpA RNAi and UAS-CalpB RNAi were obtained from the TRIP stock collection at the Bloomington Drosophila Stock Center.

Constructs for S2 cell expression

pMT-CalpA-V5/His was produced by amplification of Kpn-CalpA-Not from cDNA clone LD22862 (pOT2-CalpA), cut and ligated into pMT-HisC with KpnI/NotI. pAcPA-CalpA-eGFP was produced by overlap extension using LD22826 and pBS-eGFP as templates, with the eGFP sequence lacking the first Met cloned in frame with CalpA, and inserted into pAcPA with KpnI/NotI. pAcPA-cact-eGFP was generated by amplifying two overlapping fragments using as templates cDNA clone LD10168 (pBS-cactus) and pBS-eGFP. Left and right fragments were used for overlap extension with Expand High Fidelity polymerase using 5′ and 3′ primers to generate full-length cact-eGFP and ligated into TopoTA. eGFP was placed in frame with Cact, losing the first Met residue. A BssHII + XhoI fragment was cut from Topo-cact-eGFP and ligated into pBS, generating pBS-cact-eGFP. A similar strategy was used to generate pBS-cactE10-eGFP and pBS-cactΔPEST-eGFP. Primer sequences to amplify cactE10 are initiated at a PstI internal site, leaving the first possible ATG start codon at position 144, similar to cact[E10] mutants previously described. A PstI/XhoI fragment was inserted into pBS to generate pBS-cactE10-eGFP. Primer sequences to amplify PEST-deleted cactus end at residue 458 (Val), (before the 459 + 460 ACGCCT that was converted to a stop codon in Reach et al., 1996). pAcPA-cact-eGFP was generated by cutting pBS-cact-eGFP with BamHI/Xho and ligating into pAcPA. The same strategy was used for generating pAcPA-cactE10-eGFP and pAcPA- cactΔPEST-eGFP.

Transgenic constructs

CaMat-cact-eGFP was generated by cutting pBS-cact-eGFP with Spe/Xho and ligating into pCaMatβGalBam, deleted of the β-galactosidase gene (a kind gift of David Stein (University of Texas); Fernandez et al., 2001). This places constructs downstream of the Drosophila tubulin α-4 (α67C) promoter. CaMat-cactE10-eGFP and CaMat-cactΔPEST-eGFP were generated using a similar strategy. Several independent lines of CaMat-cact-eGFP constructs were obtained by standard P-element–mediated germline transformation (Genetic Services, Cambridge, MA). A pTiger construct for driving UASp-cact-eGFP was generated by cutting pAcPA-cact-eGFP and ligating into BamHI/NheI-cut pTiger. pTiger-CalpA-eGFP was generated by cutting pAcPA-CalpA-eGFP into KpnI/NotI-cut pTiger. pTiger is a derivative of pUASp (Ferguson et al., 2012). pTiger constructs were integrated into the attPVK00027-docking site using the ΦC31 system (Markstein et al., 2008). All constructs were sequenced before use in cell transfection or transformation. Primers used for production of S2 cell and transgenic constructs are available upon request.

S2 cell culture and transfection

S2 cells were cultured in Schneider's cell medium (Gibco, Carlsbad, CA) containing 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum. Cells were transfected with CellFectin (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) according to manufacturer's instructions. pAcPA vector was used for expression of cact-eGFP, cactΔPEST-eGFP, cactE10-eGFP, and CalpA-eGFP in S2 cells unless stated otherwise. pMT-V5/His (Invitrogen) was used for expression of CalpA-V5/His in S2 cells. Protein expression was induced by treatment of 0.7 mM CuSO4 at 24 h after transfection.

Immunoblotting and immunoprecipitation

S2 cells were transfected with the pAcPA or pMT constructs described in the text for 48 h. Cells were harvested and lysed with 200 μl of ice-cold lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% NP-40, protease inhibitor cocktail [Complete; Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany]) and centrifuged for 20 min at 4°C to remove cell debris. After preclearing of total cell lysates with protein G–Sepharose beads (for anti-Dorsal IPs) or with protein A–Sepharose beads (for anti-GFP IPs) for 20 min, the lysates were incubated with 30 μl of antibody-bound agarose beads (cross-linked with monoclonal anti-Dl antibody [Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank; DSHB; University of Iowa, Iowa City, IA]) or polyclonal anti-GFP antibody [Nova Biologicals, Oceanside, CA]) at 4°C for 3 h. Beads were washed three times with lysis buffer and then boiled in SDS–PAGE sample buffer at 95°C for 5 min and electrophoresed on NuPAGE 10% Bis-Tris gel (Invitrogen). Bleach-dechorionated embryos were homogenized in lysis buffer (one embryo/μl) and prepared directly with sample buffer for SDS–PAGE or prepared for IP analysis as described. CalpA-V5/His protein was detected by immunoblotting onto polyvinylidene fluoride membranes using an anti-V5 monoclonal antibody (1:2000; Invitrogen). Full-length and truncated Cact-eGFP were detected by immunoblotting using an anti-GFP polyclonal antiserum (1:1000; Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO). Endogenous Cactus and Dorsal were detected with monoclonal antibodies from DSHB (anti-Dl, 1:100, and anti-Cact, 1:500, respectively). Anti–α-tubulin was used as loading control (DM1α; 1:3000; Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) Antibodies were covalently attached to protein G or A–Sepharose beads as in Araujo et al. (2003). Quantification of blots was performed by measuring band intensity relative to tubulin, from direct luminescence using FluorChem HD2 and Alphaview software (Alpha Innotech, Santa Clara, CA) or from exposed films using the histogram function of Photoshop (Adobe, San Jose, CA). Graphs correspond to mean and SEM.

Immunohistochemistry of S2 cells, embryos, and fat body

S2 cells grown on chamber slides were used for immunofluorescence. After 48 h of transfection, cells were fixed for 10 min in 4% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.0, and permeabilized in PBST buffer (PBS + 0.1% Tween 20). Cells were blocked with 5% normal goat serum, incubated for 1 h with primary antibody (anti-V5, 1:1000; anti-GFP, 1:500), and subsequently incubated with secondary Alexa Fluor 488 antibodies and phalloidin–Alexa 568, mounted in Aquamount. After dechorionation in bleach, embryos were fixed in fixation buffer (PBS, 4% formaldehyde, and 50% heptane) for 20 min and devitelinized by hand shaking in methanol. After three washes with PBST, embryos were blocked with 5% normal goat serum in PBST for 1 h and incubated with the primary antibodies overnight at 4°C. Third-instar larval fat bodies were dissected in cold PBS and permeabilized in three changes of PBST for 1.5 h. Fat body tissue was blocked and incubated with primary antibodies as described. Primary antibodies used were monoclonal anti-Dl (7A4; 1:100; DSHB), anti-Cactus (3H12; 1:500; DSHB), anti-phosphotyrosine (1:1000; Cell Signaling, Beverly, MA), and polyclonal anti-calpain (1:100; a generous gift of Emori Saigo, Tokyo University) and anti-GFP (1:500; Millipore, Billerica, CA). Secondary antibodies used were Alexa Fluor 488 goat anti-rabbit and Alexa Fluor 568 goat anti-mouse (1:500; Invitrogen/Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR), incubated for 1 h at room temperature. Embryos were incubated with phalloidin–Alexa 568 for 15 min to detect polymerized actin. Alexa Fluor 568 donkey anti-mouse, Alexa Fluor 488 donkey anti-rabbit, and phalloidin–Alexa 647 were used for multiple detection in fat body. Hoechst 33342 was used at 1 μg/ml for nuclear stains. The fluorescence was detected by confocal microscopy using a Leica SP5-AOBS microscope (Leica Microsystems, Wetzlar, Germany). Quantification of the Dl gradient in embryos is described in Kanodia et al. (2009), using either a microfluidic device to measure the gradient at 15% e.l. (Chung et al., 2011) or hand-cut embryos to define the gradient at 40–60% e.l. Values for nuclear Dl levels correspond to mean and SEM.

Calpain activity

Calpain activity measurements are described in Fontenele et al. (2009). Values correspond to mean and SEM.

Quantitative real-time PCR

Quantitative real-time PCR (qRT-PCR) was performed as in Fontenele et al. (2009). RNA was isolated by the TRIzol method from 0- to 3-h dechorionated embryos or from third-instar larvae, purified, and used for reverse transcription using random primers (Superscript III; Invitrogen). Measurements were performed with an ABI 7500 Real-Time PCR System by using the SYBR Green PCR Core Reagents Kit (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Primer pairs used were as follows: drs sense, 5′-GTACTTGTTCGCCCTCTTCG-3′; drs antisense, 5′-CTTGCACACACGACGACAG-3′; dipt sense, 5′-ACCGCAGTACCCACTCAATC-3′; dipt antisense, 5′-CCCAAGTGCTGTCCATATCC-3′. All samples were analyzed in biological triplicates, and the levels of mRNAs detected were normalized to control rp49 values. Values are displayed as mean, and error bars correspond to SEM.

Fly infection and fly survival experiments

To induce septic injury, larvae or flies were pricked with a thin tungsten needle previously dipped in a concentrated culture of E. coli and grown at 25°C. Activation of the Toll pathway was induced by fungal infection with needles coated with B. bassiana spores. Larvae were used for RNA extraction and qRT-PCR as described. drs and dipt levels were measured 12 and 6 h after challenge, respectively. For survival experiments adult male fly survival was monitored for 20 d. Ninety flies were used for each condition, in three independent experiments.

Mass spectrometry, sample preparation, and data analysis

These are given in the Supplementary Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Ben Garcia for use of the cell culture facility; David Stein, Steve Wasserman, Stanislav Svartsman, Emori Saigo, and Maria Luisa Paço-Larson for reagents; and Vania Bittencourt for B. bassiana cultures. We thank Steve Wasserman, Stanislav Shvartsman, and the two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments on the manuscript and members of the Schupbach and Wieschaus labs for helpful suggestions throughout this work. We are indebted to the Bloomington Indiana Drosophila Stock Center and the Kyoto Stock Center for flies and Joe Goodhouse and Graziella Ventura for help with confocal microscopy. We are deeply grateful to Gail Barcelo for technical assistance. This work was in great part developed while H.A. was spending a sabbatical in the Schupbach laboratory, and it was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute and by U.S. Public Health Service Grant RO1 GM077620 to T.S. and a CNPq/Brasil sabbatical fellowship and grant to H.A (201064/2010-3 and 471734/2010-1).

Abbreviations used:

- Cact

cactus

- CalpA

Calpain A

- coIP

coimmunoprecipitation

- EGTA

ethylene glycol tetraacetic acid

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- IP

immunoprecipitate

- KD

knockdown

- RNAi

RNA interference

Footnotes

This article was published online ahead of print in MBoC in Press (http://www.molbiolcell.org/cgi/doi/10.1091/mbc.E13-02-0113) on July 17, 2013.

REFERENCES

- Anderson KV, Jurgens G, Nusslein-Volhard C. Establishment of dorsal-ventral polarity in the Drosophila embryo: genetic studies on the role of the Toll gene product. Cell. 1985;42:779–789. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(85)90274-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo H, Negreiros E, Bier E. Integrins modulate Sog activity in the Drosophila wing. Development. 2003;130:3851–3864. doi: 10.1242/dev.00613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asha H, Nagy I, Kovacs G, Stetson D, Ando I, Dearolf CR. Analysis of Ras-induced overproliferation in Drosophila hemocytes. Genetics. 2003;163:203–215. doi: 10.1093/genetics/163.1.203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baghdiguian S, et al. Calpain 3 deficiency is associated with myonuclear apoptosis and profound perturbation of the IkappaB alpha/NF-kappaB pathway in limb-girdle muscular dystrophy type 2A. Nat Med. 1999;5:503–511. doi: 10.1038/8385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baud V, Derudder E. Control of NF-kappaB activity by proteolysis. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 2011;349:97–114. doi: 10.1007/82_2010_101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belvin MP, Anderson KV. A conserved signaling pathway: the Drosophila Toll-dorsal pathway. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 1996;12:393–416. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belvin MP, Jin Y, Anderson KV. Cactus protein degradation mediates Drosophila dorsal-ventral signaling. Genes Dev. 1995;9:783–793. doi: 10.1101/gad.9.7.783. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann A, Stein D, Geisler R, Hagenmaier S, Schmid B, Fernandez N, Schnell B, Nusslein-Volhard C. A gradient of cytoplasmic Cactus degradation establishes the nuclear localization gradient of the dorsal morphogen in Drosophila. Mech Dev. 1996;60:109–123. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(96)00607-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bertipaglia I, Carafoli E. Calpains and human disease. Subcell Biochem. 2007;45:29–53. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4020-6191-2_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calle Y, Carragher NO, Thrasher AJ, Jones GE. Inhibition of calpain stabilises podosomes and impairs dendritic cell motility. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:2375–2385. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan KT, Bennin DA, Huttenlocher A. Regulation of adhesion dynamics by calpain-mediated proteolysis of focal adhesion kinase (FAK) J Biol Chem. 2010;285:11418–11426. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.090746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charatsi I, Luschnig S, Bartoszewski S, Nusslein-Volhard C, Moussian B. Krapfen/dMyd88 is required for the establishment of dorsoventral pattern in the Drosophila embryo. Mech Dev. 2003;120:219–226. doi: 10.1016/s0925-4773(02)00410-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen F, et al. Rapsyn interaction with calpain stabilizes AChR clusters at the neuromuscular junction. Neuron. 2007;55:247–260. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2007.06.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choe KM, Werner T, Stoven S, Hultmark D, Anderson KV. Requirement for a peptidoglycan recognition protein (PGRP) in Relish activation and antibacterial immune responses in Drosophila. Science. 2002;296:359–362. doi: 10.1126/science.1070216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung K, Kim Y, Kanodia JS, Gong E, Shvartsman SY, Lu H. A microfluidic array for large-scale ordering and orientation of embryos. Nat Methods. 2011;8:171–176. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Gregorio E, Spellman PT, Tzou P, Rubin GM, Lemaitre B. The Toll and Imd pathways are the major regulators of the immune response in Drosophila. EMBO J. 2002;21:2568–2579. doi: 10.1093/emboj/21.11.2568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Thonel A, Ferraris SE, Pallari HM, Imanishi SY, Kochin V, Hosokawa T, Hisanaga S, Sahlgren C, Eriksson JE. Protein kinase Czeta regulates Cdk5/p25 signaling during myogenesis. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:1423–1434. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-10-0847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLotto R, DeLotto Y, Steward R, Lippincott-Schwartz J. Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling mediates the dynamic maintenance of nuclear Dorsal levels during Drosophila embryogenesis. Development. 2007;134:4233–4241. doi: 10.1242/dev.010934. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drier EA, Huang LH, Steward R. Nuclear import of the Drosophila Rel protein Dorsal is regulated by phosphorylation. Genes Dev. 1999;13:556–568. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.5.556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- duVerle D, Takigawa I, Ono Y, Sorimachi H, Mamitsuka H. CaMPDB: a resource for calpain and modulatory proteolysis. Genome Inform. 2010;22:202–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emori Y, Saigo K. Calpain localization changes in coordination with actin-related cytoskeletal changes during early embryonic development of Drosophila. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:25137–25142. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson SB, Blundon MA, Klovstad MS, Schupbach T. Modulation of gurken translation by insulin and TOR signaling in Drosophila. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:1407–1419. doi: 10.1242/jcs.090381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernandez NQ, Grosshans J, Goltz JS, Stein D. Separable and redundant regulatory determinants in Cactus mediate its dorsal group dependent degradation. Development. 2001;128:2963–2974. doi: 10.1242/dev.128.15.2963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foe VE, Alberts BM. Studies of nuclear and cytoplasmic behaviour during the five mitotic cycles that precede gastrulation in Drosophila embryogenesis. J Cell Sci. 1983;61:31–70. doi: 10.1242/jcs.61.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontenele M, Carneiro K, Agrellos R, Oliveira D, Oliveira-Silva A, Vieira V, Negreiros E, Machado E, Araujo H. The Ca2+-dependent protease Calpain A regulates Cactus/I kappaB levels during Drosophila development in response to maternal Dpp signals. Mech Dev. 2009;126:737–751. doi: 10.1016/j.mod.2009.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich P, Bozoky Z. Digestive versus regulatory proteases: on calpain action in vivo. Biol Chem. 2005;386:609–612. doi: 10.1515/BC.2005.071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Friedrich P, Tompa P, Farkas A. The calpain-system of Drosophila melanogaster: coming of age. Bioessays. 2004;26:1088–1096. doi: 10.1002/bies.20106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geisler R, Bergmann A, Hiromi Y, Nusslein-Volhard C. cactus, a gene involved in dorsoventral pattern formation of Drosophila, is related to the I kappa B gene family of vertebrates. Cell. 1992;71:613–621. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90595-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Georgel P, Naitza S, Kappler C, Ferrandon D, Zachary D, Swimmer C, Kopczynski C, Duyk G, Reichhart JM, Hoffmann JA. Drosophila immune deficiency (IMD) is a death domain protein that activates antibacterial defense and can promote apoptosis. Dev Cell. 2001;1:503–514. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(01)00059-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie SK, Wasserman SA. Dorsal, a Drosophila Rel-like protein, is phosphorylated upon activation of the transmembrane protein Toll. Mol Cell Biol. 1994;14:3559–3568. doi: 10.1128/mcb.14.6.3559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govind S, Brennan L, Steward R. Homeostatic balance between dorsal and cactus proteins in the Drosophila embryo. Development. 1993;117:135–148. doi: 10.1242/dev.117.1.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han Y, Weinman S, Boldogh I, Walker RK, Brasier AR. Tumor necrosis factor-alpha-inducible IkappaBalpha proteolysis mediated by cytosolic m-calpain. A mechanism parallel to the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway for nuclear factor-kappab activation. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:787–794. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.2.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hecht PM, Anderson KV. Genetic characterization of tube and pelle, genes required for signaling between Toll and dorsal in the specification of the dorsal-ventral pattern of the Drosophila embryo. Genetics. 1993;135:405–417. doi: 10.1093/genetics/135.2.405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoffmann JA. The immune response of Drosophila. Nature. 2003;426:33–38. doi: 10.1038/nature02021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horng T, Medzhitov R. Drosophila MyD88 is an adapter in the Toll signaling pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:12654–12658. doi: 10.1073/pnas.231471798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang HR, Chen ZJ, Kunes S, Chang GD, Maniatis T. Endocytic pathway is required for Drosophila Toll innate immune signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:8322–8327. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1004031107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ip YT, Reach M, Engstrom Y, Kadalayil L, Cai H, Gonzalez-Crespo S, Tatei K, Levine M. Dif, a dorsal-related gene that mediates an immune response in Drosophila. Cell. 1993;75:753–763. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(93)90495-c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isoda K, Nusslein-Volhard C. Disulfide cross-linking in crude embryonic lysates reveals three complexes of the Drosophila morphogen dorsal and its inhibitor cactus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5350–5354. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.12.5350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jekely G, Friedrich P. The evolution of the calpain family as reflected in paralogous chromosome regions. J Mol Evol. 1999;49:272–281. doi: 10.1007/pl00006549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaczmarek JS, Riccio A, Clapham DE. Calpain cleaves and activates the TRPC5 channel to participate in semaphorin 3A-induced neuronal growth cone collapse. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:7888–7892. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205869109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanodia JS, Rikhy R, Kim Y, Lund VK, DeLotto R, Lippincott-Schwartz J, Shvartsman SY. Dynamics of the Dorsal morphogen gradient. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:21707–21712. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0912395106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kidd S. Characterization of the Drosophila cactus locus and analysis of interactions between cactus and dorsal proteins. Cell. 1992;71:623–635. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90596-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim Y, Andreu MJ, Lim B, Chung K, Terayama M, Jimenez G, Berg CA, Lu H, Shvartsman SY. Gene regulation by MAPK substrate competition. Dev Cell. 2011;20:880–887. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2011.05.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kokai E, Paldy FS, Somogyi K, Chougule A, Pal M, Kerekes E, Deak P, Friedrich P, Dombradi V, Adam G. CalpB modulates border cell migration in Drosophila egg chambers. BMC Dev Biol. 2012;12:20. doi: 10.1186/1471-213X-12-20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lade A, Ranganathan S, Luo J, Monga SP. Calpain induces N-terminal truncation of beta-catenin in normal murine liver development: diagnostic implications in hepatoblastomas. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:22789–22798. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.378224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaitre B, Kromer-Metzger E, Michaut L, Nicolas E, Meister M, Georgel P, Reichhart JM, Hoffmann JA. A recessive mutation, immune deficiency (imd), defines two distinct control pathways in the Drosophila host defense. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:9465–9469. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.21.9465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaitre B, Nicolas E, Michaut L, Reichhart JM, Hoffmann JA. The dorsoventral regulatory gene cassette spatzle/Toll/cactus controls the potent antifungal response in Drosophila adults. Cell. 1996;86:973–983. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemaitre B, Reichhart JM, Hoffmann JA. Drosophila host defense: differential induction of antimicrobial peptide genes after infection by various classes of microorganisms. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:14614–14619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.26.14614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberman LM, Reeves GT, Stathopoulos A. Quantitative imaging of the Dorsal nuclear gradient reveals limitations to threshold-dependent patterning in Drosophila. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:22317–22322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0906227106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li C, Chen S, Yue P, Deng X, Lonial S, Khuri FR, Sun SY. Proteasome inhibitor PS-341 (bortezomib) induces calpain-dependent IkappaB(alpha) degradation. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:16096–16104. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.072694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li G, Iyengar R. Calpain as an effector of the Gq signaling pathway for inhibition of Wnt/beta -catenin-regulated cell proliferation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13254–13259. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202355799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ligoxygakis P, Pelte N, Hoffmann JA, Reichhart JM. Activation of Drosophila Toll during fungal infection by a blood serine protease. Science. 2002;297:114–116. doi: 10.1126/science.1072391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu ZP, Galindo RL, Wasserman SA. A role for CKII phosphorylation of the cactus PEST domain in dorsoventral patterning of the Drosophila embryo. Genes Dev. 1997;11:3413–3422. doi: 10.1101/gad.11.24.3413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Wu LP, Anderson KV. The antibacterial arm of the Drosophila innate immune response requires an IkappaB kinase. Genes Dev. 2001;15:104–110. doi: 10.1101/gad.856901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lund VK, DeLotto Y, DeLotto R. Endocytosis is required for Toll signaling and shaping of the Dorsal/NF-kappaB morphogen gradient during Drosophila embryogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:18028–18033. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1009157107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manfruelli P, Reichhart JM, Steward R, Hoffmann JA, Lemaitre B. A mosaic analysis in Drosophila fat body cells of the control of antimicrobial peptide genes by the Rel proteins Dorsal and DIF. EMBO J. 1999;18:3380–3391. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.12.3380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marek LR, Kagan JC. Phosphoinositide binding by the Toll adaptor dMyD88 controls antibacterial responses in Drosophila. Immunity. 2012;36:612–622. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.01.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Markstein M, Pitsouli C, Villalta C, Celniker SE, Perrimon N. Exploiting position effects and the gypsy retrovirus insulator to engineer precisely expressed transgenes. Nat Genet. 2008;40:476–483. doi: 10.1038/ng.101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meng X, Khanuja BS, Ip YT. Toll receptor-mediated Drosophila immune response requires Dif, an NF-kappaB factor. Genes Dev. 1999;13:792–797. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.7.792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michel T, Reichhart JM, Hoffmann JA, Royet J. Drosophila Toll is activated by Gram-positive bacteria through a circulating peptidoglycan recognition protein. Nature. 2001;414:756–759. doi: 10.1038/414756a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moncrieffe MC, Grossmann JG, Gay NJ. Assembly of oligomeric death domain complexes during Toll receptor signaling. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:33447–33454. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805427200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moussian B, Roth S. Dorsoventral axis formation in the Drosophila embryo—shaping and transducing a morphogen gradient. Curr Biol. 2005;15:R887–R899. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2005.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicolas E, Reichhart JM, Hoffmann JA, Lemaitre B. In vivo regulation of the IkappaB homologue cactus during the immune response of Drosophila. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:10463–10469. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.17.10463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Dea EL, Barken D, Peralta RQ, Tran KT, Werner SL, Kearns JD, Levchenko A, Hoffmann A. A homeostatic model of IkappaB metabolism to control constitutive NF-kappaB activity. Mol Syst Biol. 2007;3:111. doi: 10.1038/msb4100148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]