Summary

This review highlights the progress made thus far in characterizing the behavioral and cellular mechanisms through which cannabinoids regulate energy homeostasis. We performed microstructural analysis of feeding behavior in gonadectomized guinea pigs and gonadally intact, transgenic CB1 receptor knockout mice to determine how cannabinoids affect circadian rhythms in food intake and meal pattern. We also implanted data loggers into the abdominal cavity to correlate the appetite-modulating properties of cannabinoids with changes in core body temperature. We then coupled the effects on feeding behavior and temperature regulation with synaptic changes in the hypothalamic feeding circuitry via whole-cell patch clamp electrophysiological recording from neurons in the arcuate nucleus (ARC), in order to gain a more global perspective on the cannabinoid modulation of energy homeostasis. We observed marked sex differences in cannabinoid effects on food intake and core body temperature — with male guinea pigs exhibiting a comparatively greater sensitivity to the hyperphagia and hypophagia, as well as the hypothermia and hyperthermia, produced by CB1 receptor agonists and antagonists, respectively. In addition, male but not female CB1 receptor knockout mice show a diminished nocturnal food intake and average daily body weight relative to their wildtype littermate controls. The disparity in the CB1 receptor-mediated hyperphagia is paralleled by sex differences in the cellular effects of cannabinoids at anorexigenic, guinea pig proopiomelanocortin (POMC) synapses. Postsynaptically, cannabinoids potentiate an A-type K+ current (IA) in POMC neurons from female guinea pigs, whereas in males the activation of an inwardly rectifying K+ current is observed. Presynaptically, while cannabinoids inhibit glutamatergic input onto POMC neurons in males and females to similar degrees, males are more refractory to the cannabinoid-induced inhibition of convergent GABAergic input than females. These data reveal pervasive sex differences in the cannabinoid regulation of energy homeostasis that are consistent with changes in the excitability of POMC neurons.

Keywords: Cachexia, Obesity, GABA, Glutamate, CB1 receptor, K+ channels

1. Introduction

Over the past 30 years the literature is marked by a number of reports demonstrating sex differences in the biological activity and metabolism of cannabinoids. Males consume marijuana in greater amounts, at higher rates, and report a greater subjective psychotropic effect of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) than do females (Paton and Kandel, 1978; Perez-Reyes et al., 1981; Penetar et al., 2005). Men also exhibit higher circulating levels of THC, and are much more likely to be arrested for driving under the influence of cannabis (Jones et al., 2008). On the other hand, female rodents express greater amounts of hepatic cytochrome P-450 isozymes and aldehyde oxygenase activity that may facilitate conversion of THC to potent bioactive metabolites such as 11-hydroxy-THC (Narimatsu et al., 1991; Watanabe et al., 1992; Narimatsu et al., 1992). In addition, self-administration of the CB1 receptor agonist WIN 55,212-2 in female Long Evans and Lister Hooded rats is more rapidly acquired, and more robustly maintained, than in their male counterparts (Fattore et al., 2007). These reported inequities in cannabinoid ingestion or self-administration, coupled with disparate metabolism, xenobiotic transformation and expression of cannabinoid receptors (Rodríguez de Fonseca et al., 1994), would differentially alter cannabinoid availability and signal strength in the target tissues and brain regions, and thus the biological effects of cannabinoids, in males and females. Indeed, cannabinoids elicit a comparatively greater antinociception and locomotor effects in female rodents (Tseng and Craft, 2001; Wiley, 2003; Tseng et al., 2004), and women are more susceptible to cannabinoid-induced hemodynamic changes and visuospatial memory impairment than men (Pope et al., 1997; Mathew et al., 2003). Cannabinoids also regulate the transcription of proopiomelanocortin (POMC) and preprocorticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) genes in a sexually differentiated manner; with the THC-induced increases in CRH expression in males dependent upon the presence of dihydrotestosterone, and the increases in POMC expression in females dependent upon the presence of estrogen (Corchero et al., 2001). In addition, they interact with other drugs of abuse such as nicotine to modulate anxiety in a sex-specific fashion(Marco et al., 2006). Given the burgeoning wealth of evidence for sex differences in cannabinoid regulated biology, we focus here on those pertaining to the behavioral and cellular mechanisms through which cannabinoids modulate energy homeostasis.

2. Sex differences in the cannabinoid regulation of feeding and core body temperature

Both naturally occurring and synthetic cannabinoids stimulate hyperphagia (Cota et al., 2003; Fride et al., 2005) and hypothermia (Fitton and Pertwee, 1982; Hillard et al., 1999). Microstructural analyses of the effects of the CB1 receptor agonist WIN 55,212-2 on food intake and meal pattern in gonadectomized guinea pigs show a considerably more robust stimulation of intake in males than in females. This is characterized by a more prolonged, acute increase in hourly intake that peaks 2 h after administration, and a more extensive, latent nocturnal increase in hourly intake (Fig. 1), that collectively translates into a more substantial, cumulative daily intake measured 24 h after administration (Fig. 2). In males, the hyperphagia produced by WIN 55,212-2 is associated with increased meal size and duration, and a latent increase in meal frequency, whereas in females it is coupled with both acute and latent increases in meal frequency (Diaz et al., in press). Conversely, the CB1 receptor antagonist AM251 produced a modest decrease in hourly food intake that overall was greater in males than in females. AM251 acutely reduced intake 2 h after administration, and blocked the peak intake that occurred 1 h after lights off (19:00 h), to equivalent degrees in male and female animals (Fig. 1). However, the antagonist produced a prolonged and pronounced decrease in hourly intake during the latter part of the nocturnal period that was observed exclusively in males (Fig. 1). This disparate anorectic effect of AM251 is associated with both acute and latent nocturnal decreases in meal frequency in male but not female guinea pigs (Diaz et al., in press). Interestingly, the circadian hourly intake pattern observed in AM251-treated male guinea pigs very closely resembled that exhibited by male CB1 receptor knockout mice; especially with regard to the reduced nocturnal hourly intake compared to male wildtype littermate controls (Fig. 3). This differential cannabinoid modulation of appetite is paralleled by equally disparate changes in core body temperature. For example, the peak hypothermia produced by WIN 55,212-2 is ∼0.5 °C greater in males than in females, and the hyperthermic effect of AM251 is likewise more extensive in males than in females (Fig. 4).

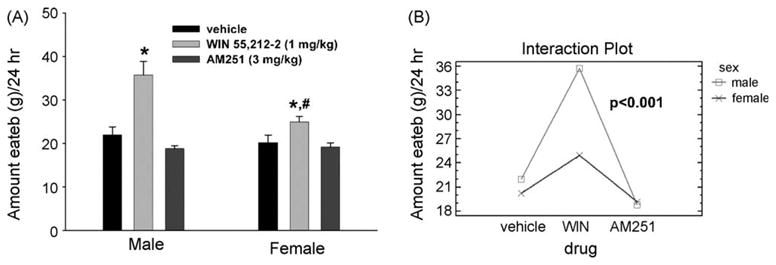

Figure 1.

Sex differences in cannabinoid-induced alterations in hourly food intake. (A) Gonadectomized male and female animals were injected with WIN 55,212-2 (1 mg/kg; s.c.), AM251 (3 mg/kg; s.c.) or their cremephor/ethanol/saline vehicle at 08:00 and immediately placed back into their respective feeding chambers. The symbols represent means and vertical lines 2 S.E.M. (n = 4) of the total amount of food consumed every hour over a 24-h period. The data to the left of the injection arrow represent the average cumulative intake measured at hourly intervals from 1:00 to 8:00 a.m. across the 7 days of exposure. *Values from animals treated with WIN 55,212-2 that are significantly different (multi-factorial ANOVA/LSD; p < 0.05) than those observed in vehicle-treated controls. #Values from females that are significantly different (multi-factorial ANOVA/LSD; p < 0.05) than those from their male counterparts. **Values from animals treated with AM251 that are significantly different (multi-factorial ANOVA/LSD; p < 0.05) than those observed in vehicle- or agonist-treated animals. (B) An interaction plot that illustrates the significant interaction between sex and drug, and the significant changes in hourly intake in agonist- and antagonist-treated animals. Printed with permission from Diaz et al. (in press) (S. Karger AG, Basel).

Figure 2.

Sex differences in cannabinoid-induced alterations in daily food intake. (A) Gonadectomized male and female animals were injected with WIN 55,212-2 (1 mg/kg; s.c.), AM251 (3 mg/kg; s.c.) or their cremephor/ethanol/saline vehicle at 08:00 and immediately placed back into their respective feeding chambers. The vertical bars represent means and vertical lines 1 S.E.M. (n = 4) of the total amount of food consumed over a 24-h period. *Values from animals treated with WIN 55,212-2 that are significantly different (multi-factorial ANOVA/LSD; p < 0.05) than those observed in vehicle-treated animals. #Values from female animals that are significantly different (multi-factorial ANOVA/LSD; p < 0.05) than those from males. (B) An interaction plot illustrating the significant interaction between sex and drug, and the significant increase in daily food intake in agonist-treated animals. Printed with permission from Diaz et al. (in press) (S. Karger AG, Basel).

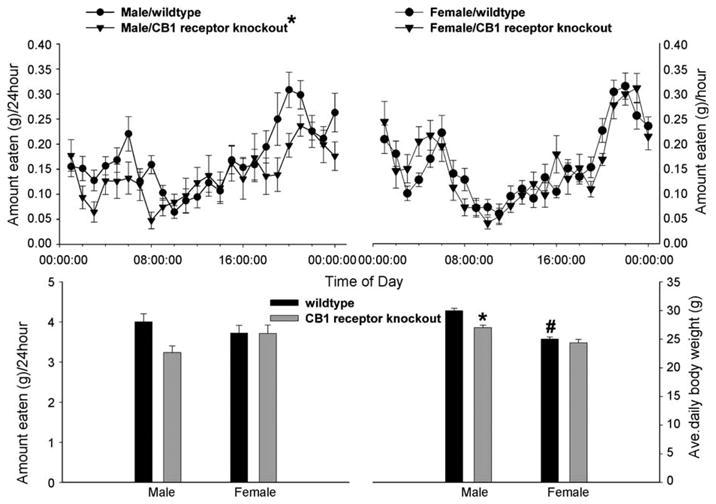

Figure 3.

Sex differences in the cannabinoid regulation of energy homeostasis in gonadally intact, male and female CB1 receptor knockout mice vs. their respective wildtype littermate controls. The top row illustrates the sexually dimorphic alterations in hourly food in take. The symbols represent means and vertical lines 2 S.E.M. (n = 4) of the total amount of food consumed every hour over a 24-hperiod. The bottom row shows the changes in daily food intake (left panel) and body weight (right panel). The vertical bars represent means and vertical lines1 S.E.M.(n = 4) of the total amount of food consumed over 24 h(left panel) and the average daily body weight observed over the entire monitoring period (right panel). *Values from male CB1 receptor knockout mice that are significantly different (multi-factorial ANOVA/LSD; p < 0.05) than those observed in littermate controls. #Values from females that are significantly different (multi-factorial ANOVA/LSD; p < 0.05) than those from their male counterparts. Printed with permission from Diaz et al. (in press) (S. Karger AG, Basel).

Figure 4.

Sex differences in the cannabinoid modulation of core body temperature. Gonadectomized male and female animals were injected with WIN 55,212-2 (1 mg/kg; s.c.), AM251 (3 mg/kg; s.c.) or their cremephor/ethanol/saline vehicle at 08:00 and immediately placed back into their respective feeding chambers. The symbols represent means and vertical lines 2 S.E.M. (n = 4) of the core body temperature recorded every seven minutes by data loggers inserted into the abdominal cavity at the time of castration. *Values from animals treated with WIN 55,212-2 that are significantly different (multi-factorial ANOVA/LSD; p < 0.05) than those observed in vehicle-treated controls. #Values from females that are significantly different (multi-factorial ANOVA/LSD; p < 0.05) than those from males. **Values from animals treated with AM251 that are significantly different (multi-factorial ANOVA/LSD; p < 0.05) than those observed in vehicle- or agonist-treated animals. Printed with permission from Diaz et al. (in press) (S. Karger AG, Basel).

3. Sex differences in the pre- and postsynaptic actions of cannabinoids at POMC synapses

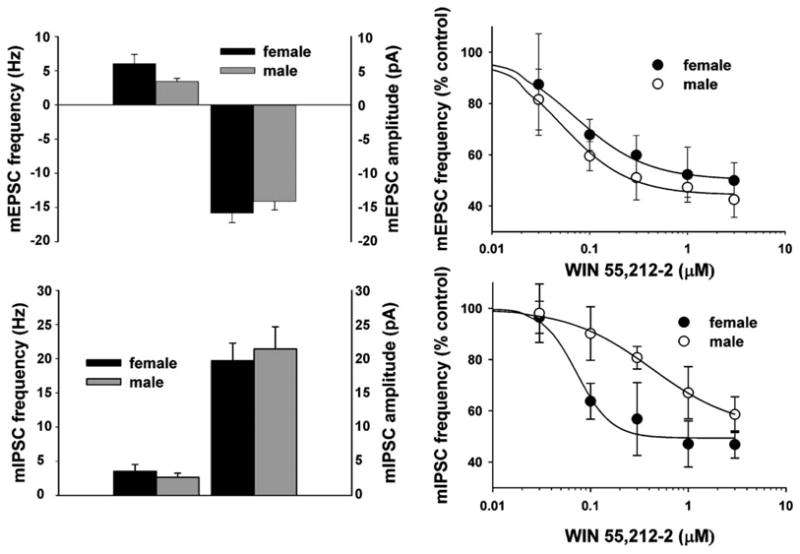

It has long been known that exogenous and endogenous cannabinoids presynaptically inhibit neurotransmitter release in the central nervous system, including in hypothalamic nuclei such as the arcuate nucleus (ARC; Hentges et al., 2005; Nguyen and Wagner, 2006; Ho et al., 2007; Diaz et al., in press), lateral hypothalamus (Jo et al., 2005; Huang et al., 2007) and paraventricular nucleus (Di et al., 2005) that largely comprise the hypothalamic feeding circuitry. In addition, the hypothalamic levels of endogenous cannabinoids are decreased by leptin (Di Marzo et al., 2001) and increased by ghrelin (Kola et al., 2008). At anorexigenic ARC POMC synapses CB1 receptor agonists inhibit both glutamate and γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) release in slices from both transgenic mice (Hentges et al., 2005) and guinea pigs (Nguyen and Wagner, 2006; Diaz et al., in press), an example of the latter of which is shown in Fig. 5. While POMC neurons from male and female guinea pigs are similarly responsive to the reduction of glutamatergic mEPSC frequency produced by WIN 55,212-2 (Diaz et al., in press), the cells from male animals are considerably less sensitive to the agonist-induced attenuation of GABAergic mIPSC frequency than those from female animals (Fig. 6). This is manifested by a selective rightward shift in the agonist dose—response curve to inhibit mIPSC frequency, and a ∼6× reduction in agonist potency (females: IC50 = 72.6 nM; males: IC50 = 427.6 nM; Fig. 7). This demonstrates that the cannabinoid-induced alteration in GABAergic neurotransmission at POMC synapses is sexually differentiated.

Figure 5.

Double-labeling of an arcuate neuron that is immunopositive for a phenotypic marker characteristic of POMC neurons. (A) Color photomicrograph that illustrates the biocytin-streptavidin-cy2 labeling (denoted by the arrow). (B) Color photomicrograph of the α-MSH immunofluorescence observed in the perikarya of A as visualized with cy3 (also denoted by the arrow). (C) Composite overlay illustrating the double labeling in this arcuate neuron. All photomicrographs were taken with a 40× objective. Printed with permission from Ho et al. (2007) (Elsevier).

Figure 6.

CB1receptor activation decreases mIPSC frequency to different degrees in ARC neurons from male and female animals. There are six membrane current traces — three that are 25 s in duration and three that are 5 s in duration and represent expanded portions of their respective upper traces that are enclosed by the rectangle that show the mIPSCs in an ARC neuron from a gonadectomized male (top two rows) and female (bottom two rows) under basal (left column), and agonist-stimulated (middle and right columns) conditions. To the right of the traces are cumulative probability plots depicting the interval between contiguous mIPSCs and their amplitudes for each of the three treatment conditions. The ARC neuron from the male animal exhibited a basal mIPSC frequency of 12.2 Hz, whereas the cell from the female animal had a baseline frequency of 13.7 Hz. 100 nM WIN 55,212-2 had no effect on mIPSC frequency relative to baseline control in the ARC neuron from the male animal, whereas the agonist evoked a ∼33% decrease in the cell from the female animal. The higher 1 μM concentration elicited a ∼54% reduction in mIPSC frequency in the ARC neuron from the male animal, and a ∼41% diminution in the cell from the female animal. Printed with permission from Diaz et al. (in press) (S. Karger AG, Basel).

Figure 7.

Sex differences in the CB1 receptor-mediated inhibition of mEPSC and mIPSC frequency. Top left: composite bar graph illustrating the basal mEPSC frequency and amplitude in ARC neurons from gonadectomized male and female animals. Bars represent means and vertical lines 1 S.E.M. of the basal mEPSC frequency (left) and amplitude (right) measured in ARC neurons obtained from female (black columns; n = 28) and male (gray columns; n = 17) animals. Note the nearly twofold higher basal mEPSC frequency in ARC neurons from females. Top right: composite dose—response curves for the decrease in mEPSC frequency produced by WIN 55,212-2 in ARC neurons from gonadectomized, female (●) and male (○) animals. The curves were fit via logistic equation to the data points. Symbols represent means and vertical lines 2 S.E.M. (n = 2—12) of the mEPSC frequency seen with varying concentrations of WIN 55,212-2 that were normalized to their respective control values. Bottom left: composite bar graph illustrating the basal mIPSC frequency and amplitude in ARC neurons from gonadectomized male and female animals. Bars represent means and vertical lines 1 S.E.M. of the basal mIPSC frequency (left) and amplitude (right) measuredin ARC neurons obtained from female (black columns; n = 11) and male (gray columns; n = 9) animals. Bottom right: composite dose—response curves for the decrease in mIPSC frequency produced by WIN 55,212-2 in ARC neurons from gonadectomized, female (●) and male (○) animals. The curves were fit via logistic equation to the data points. Symbols represent means and vertical lines 2 S.E.M. (n = 2—12) of the mIPSC frequency seen with varying concentrations of WIN 55,212-2 that were normalized to their respective control values. Note the prominent rightward shift in the agonist dose—response curve for the male. Printed with permission from Diaz et al. (in press) (S. Karger AG, Basel).

In addition to the presynaptic inhibition of glutamate and GABA release, CB1 receptor agonists also modulate postsynaptic K+ currents. Indeed, WIN 55,212-2 enhances the transient, A-type K+ current (IA) in cultured hippocampal neurons (Deadwyler et al., 1995; Mu et al., 1999), and activates G protein-gated, inwardly rectifying K+ (GIRK) currents in AtT20 cells (Mackie et al., 1995; Garcia et al., 1998) and Xenopus oocytes (Henry and Chavkin, 1995; McAllister et al., 1999). We found that WIN 55,212-2 augments the IA in POMC neurons from female but not male guinea pigs by right-shifting the voltage dependence of its inactivation (Fig. 8), and decreasing the amount of hyper-polarization required to remove Kv 4.2 channel inactivation (Tang et al., 2005). On the other hand, the anandamide analog ACEA induces a slow outward current in POMC neurons from male (Fig. 9) but not female (Tang et al., 2005) animals that reverses polarity near EK+ and increases slope conductance characteristic of GIRK activation. Thus, both the cannabinoid-induced presynaptic modulation of GABA release, and the postsynaptic modulation of K+ currents, is sexually disparate.

Figure 8.

CB1 receptor activation alters the voltage dependence of the IA inactivation in a sex-dependent fashion. (A) The IA evoked under baseline control conditions in hypothalamic neurons from female (top) and male (bottom) guinea pigs during the inactivation protocol. The IA is observed as a transient outward current immediately following delivery of the test pulse (denoted by the arrow). (B) The IA evoked in the presence of WIN 55,212-2 (1 μM) in the same neurons using the same inactivation protocol as in (A). (C) Composite inactivation curves for the IA derived from recordings of female (top) and male (bottom) guinea pig hypothalamic neurons. The Boltzmann equation fits the curves to the corresponding data points. Symbols and accompanying vertical lines represent means 2 S.E.M. of peak currents normalized to the Imax that were observed at the test pulse following a given pre-pulse. The horizontal dashed lines seen in both graphs represent I/Imax = 0.5 = V1/2. Top graph: three vertical dotted lines intersect the abscissa at different points; representing the V1/2 observed under baseline control conditions (center), in the presence of 1 μM WIN 55,212-2 (right) and in the presence of WIN 55,212-2 and the CB1 receptor antagonist AM251 (left). Bottom graph: two vertical dotted lines intersect the abscissa; the one on the right represents the V1/2 observed under baseline control conditions, and the one on the left represents the V1/2 observed in the presence of 1 μM WIN 55,212-2. *The estimated V1/2 derived from hypothalamic neurons in the presence of WIN 55,212-2 that is significantly different (p < .05; one-way ANOVA/LSD) than that observed under baseline control conditions and in the presence of the antagonist. Taken from Tang et al. (2005).

Figure 9.

Top left: a reversible outward current elicited by the anandamide derivative ACEA in an arcuate neuron from an intact male guinea pig. This outward current was produced by ACEA (1 μM) from a holding potential of −60 mV in the presence of 1 μM TTX. The break in the trace in the upper panel represents the time necessary to conduct a second I/V relationship, and the early stages of ACEA clearance from the slice. Top right: an I/V plot that reveals the ACEA-induced increase in slope conductance as well as the reversal potential (−97 mV) near the Nernst equilibrium potential for K+. The symbols represent the changes in membrane current (ΔI) observed at different membrane voltages (Vm) that were caused by ACEA. The increase in slope conductance estimated by linear regression between −60 and −80 mVwas (2.75 nS), whereas that between −100 and −130 mV was even greater (4.76 nS; rectification ratio: 1.7). Bottom left: another example of the CB1 receptor-mediated outward current recorded in an arcuate neuron from a male guinea pig. This reversible, ACEA-induced outward current (12.2 pA at −60 mV) was observed in the presence of 1 μMTTX. The break in the trace represents the time necessary to conduct a second I/V in the presence of drug, as well as the early stages of drug clearance from the slice. Bottom right: this trace shows the effect of ACEA observed in the presence of the CB1 receptor antagonist AM251 (1 μM). The data was obtained from the same neuron as shown in the bottom left. Note that AM251 completely blocked the ACEA-induced outward current. Adapted from Ho et al. (2007) (Elsevier).

4. Significance

The results gathered by our laboratory over the past few years point to a marked sex difference in the cannabinoid regulation of energy homeostasis — with males being more responsive than females to the appetite modulating and body temperature regulating properties of these compounds. These findings have clear clinical relevance. Men consume marijuana in greater amounts, and use it more frequently for a greater reported psychotropic effect, than women (Paton and Kandel, 1978; Perez-Reyes et al., 1981; Penetar et al., 2005). In most of the case studies and randomized, placebo-controlled studies describing the effectiveness of THC in ameliorating cachexic symptoms and promoting appetite in patients with cancer (Walsh et al., 2005) and HIV/AIDS (Woolridge et al., 2005; Haney et al., 2005), as well as with irretractable chronic pain (Lynch et al., 2006), the vast majority of study participants were men. However, in another clinical trial that examined the ability of cannabis extract and THC to mitigate against anorexia and cachexia in cancer patients more equitably distributed across gender, the results were nowhere near as impressive (Strasser et al., 2006). Moreover, female rodents are more sensitive to the appetite-suppressant effects of the adipostat leptin (Woods et al., 2003), which is known to decrease hypothalamic levels of endogenous cannabinoids (Di Marzo et al., 2001). This indicates the necessity of considering gender when contemplating the use of cannabinoids as pharmacotherapy against body wasting and emaciation in these clinical situations.

While many consider the CB1 receptor as the predominant subtype expressed in the central nervous system, recent evidence has demonstrated that the CB2 subtype is expressed in brain areas important for the control of energy homeostasis such as the ARC, ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus, and the brain stem (Van Sickle et al., 2005; Gong et al., 2006). In addition, the cannabinoid agonist WIN 55,212-2 employed in many of our studies has considerable affinity for the CB2 receptor (Cota et al., 2006). Despite this apparent lack of receptor specificity, however, the hyperphagia, the reduction in both evoked EPSC amplitude and mEPSC frequency, and the activation of postsynaptic K+ conductances in POMC neurons caused by WIN 55,212-2 are blocked by the CB1 receptor antagonist AM251 (Tang et al., 2005; Nguyen and Wagner, 2006; Ho et al., 2007; Figs. 8 and 9). Moreover, the hypophagia seen in the male CB1 receptor knockout mice is very similar to that observed in male, AM251-treated male guinea pigs (Diaz et al., in press). Collectively, this indicates that the cannabinoid effects that we see regarding energy homeostasis are in fact CB1 receptor-mediated.

The sex difference in the cannabinoid regulation of energy homeostasis observed at the behavioral level is accompanied by differential underlying changes in the cellular physiology at POMC synapses. At POMC synapses from female animals there is an intrinsically higher basal mEPSC frequency than is observed in males, and CB1 receptor agonists presynaptically inhibit glutamate and GABA with equivalent potency and efficacy (Diaz et al., in press). At POMC synapses from male animals, glutamatergic nerve terminals are just as sensitive to CB1 receptor stimulation as those seen in females, whereas the GABAergic nerve terminals are relatively resistant (Diaz et al., in press). Thus, the presynaptic actions of cannabinoids differentially impact the glutamatergic and GABAergic input converging on POMC neurons, and thereby alter the excitability of these cells in sex-specific ways. In females, CB1 receptor activation would preferentially shift the balance toward excitation due to elevated synaptic levels of glutamate, whereas in males the balance is shifted toward inhibition due to augmented synaptic levels of GABA. These synaptic dynamics are illustrated in Fig. 10.

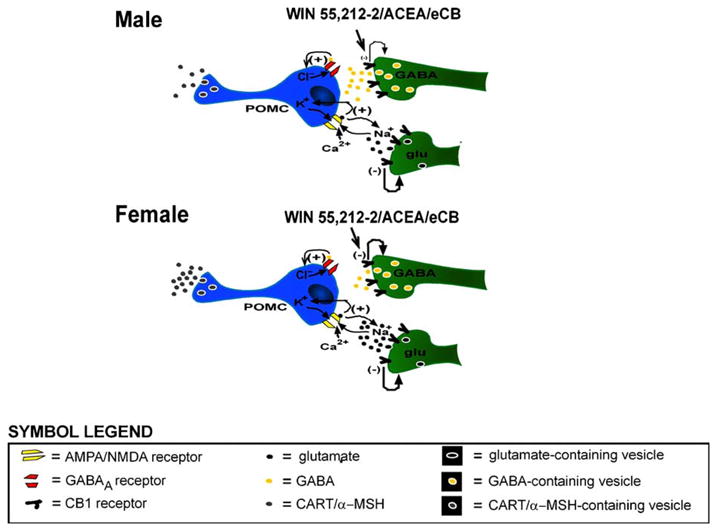

Figure 10.

Schematic diagrams depicting the proposed cellular mechanism of action that may account, in part, for the sexually differentiated, cannabinoid-induced hyperphagia. Presynaptic CB1 receptors on glutamatergic and GABAergic nerve terminals are activated by exogenous administration of agonists such as WIN 55,212-2 or arachidonyl-2-chloroethylamide (ACEA), or by endogenous cannabinoids (eCBs) such as anandamide, whereupon they inhibit to the release of glutamate or GABA. The degree to which these neurotransmitters are presynaptically inhibited varies in males and females. In males, cannabinoids preferentially inhibit glutamatergic input, whereas in females the glutamatergic and GABAergic nerve terminals are equally responsive to CB1 receptor-mediated presynaptic inhibition. Therefore, the net inhibitory effect of cannabinoids on the excitability of POMC neurons is greater in males than in females, which would partly explain why males are more responsive to the cannabinoid-induced hyperphagia than females.

In addition to these presynaptic actions, CB1 receptor-mediated activation of postsynaptic K+ conductances in POMC neurons may also contribute to the observed homeostatic sex differences. For example, CB1 receptor stimulation positively modulates the IA in POMC neurons of female but not male animals by shifting the voltage dependence of inactivation to more depolarized levels (Tang et al., 2005), and activates a G protein-gated inwardly rectifying K+ (GIRK) current in POMC neurons of male but not female animals (Tang et al., 2005; Ho et al., 2007). The IA is a rapidly activating and inactivating current mediated by the outflow of K+ ions through 4-AP-sensitive channels (Hille, 1992), and increases the interspike interval between action potentials, thereby reducing neuronal firing rate by opposing depolarizing stimuli that bring a neuron to threshold for activation of voltage-gated Na+ channels (Rudy, 1988). Along these lines, a putative augmentation of the IA in hypothalamic thermosensitive neurons would decrease the rate of change of the depolarizing prepotential and thus the firing rate of these cells (Boulant, 1998), which may provide the basis for the cannabinoid-induced hypothermia observed in this and other studies (Fitton and Pertwee, 1982; Hillard et al., 1999). On the other hand, the activation of GIRK results in a slow, inhibitory postsynaptic potential (slow IPSP) at resting membrane potentials due to the selective outflow of K+ (Rudy, 1988), that reverses polarity and markedly increases conductance at potentials negative to the equilibrium potential for K+ (Hille, 1992). The resultant GIRK-mediated current underlying the slow IPSP has a better capacity to keep the membrane potential below threshold for action potential generation than the IA, and thus a greater inhibitory impact on neuronal firing rate. This would also help explain why the CB1 receptor-mediated inhibition of POMC neurons might be more extensive in males than in females. In conclusion, our findings lend considerable insight into the pleiotropic mechanisms through which cannabinoids regulate energy homeostasis in a sexually differentiated fashion.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by PHS Grants DA00521 and DA024314, and an intramural research grant from Western University of Health Sciences.

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest: The authors disclose that there are no financial or personal conflicts of interest that could inappropriately influence the conduct of the experiments described in this work.

References

- Boulant JA. Hypothalamic neurons: mechanisms of sensitivity to temperature. Ann NY Acad Sci. 1998;856:108–115. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1998.tb08319.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corchero J, Manzanares J, Fuentes JA. Role of gonadal steroids in the corticotropin-releasing hormone and proopiomelanocortin gene expression response to Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol in the hypothalamus of the rat. Neuroendocrinology. 2001;74:185–192. doi: 10.1159/000054685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cota D, Marsicano G, Lutz B, Vicennati V, Stalla GK, Pasquali R, Pagotto U. Endogenous cannabinoid system as a modulator of food intake. Int J Obesity. 2003;27:289–301. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cota D, Tschöp MH, Horvath TL, Levine AS. Cannabinoids, opioids and eating behavior: the molecular face of hedonism? Brain Res Rev. 2006;51:85–107. doi: 10.1016/j.brainresrev.2005.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deadwyler SA, Hampson RE, Mu J, Whyte A, Childers S. Cannabinoids modulate voltage sensitive potassium A-current in hippocampal neurons via a cAMP-dependent process. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1995;273:734–743. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Marzo V, Goparahu SK, Wang L, Liu J, Bátkai S, Járai Z, Fezza F, Miura GI, Palmiter RD, Sugiura T, Kunos G. Leptin-regulated endocannabinoids are involved in maintaining food intake. Nature. 2001;410:822–825. doi: 10.1038/35071088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di S, Malcher-Lopes R, Marcheselli VL, Bazan NG, Tasker JG. Rapid glucocorticoid-mediated endocannabinoid release and opposing regulation of glutamate and γ-aminobutyric acid inputs to hypothalamic magnocellular neurons. Endocrinology. 2005;145:4292–4301. doi: 10.1210/en.2005-0610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz S, Farhang B, Hoien J, Stahlman M, Adatia N, Cox JM, Wagner EJ. Sex differences in the cannabinoid modulation of appetite, body temperature and neurotransmission at POMC synapses. Neuroendocrinology. doi: 10.1159/000191646. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fattore L, Spano MS, Altea S, Angius F, Fadda P, Fratta W. Cannabinoid self-administration in rats: sex differences and the influence of ovarian function. Br J Pharmacol. 2007;152:795–804. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0707465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitton AG, Pertwee RG. Changes in body temperature and oxygen consumption rate of conscious mice produced by intra-hypothalamic and intracerebroventricular injections of Δ9-tetra-hydrocannabinol. Br J Pharmacol. 1982;75:409–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1982.tb08802.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fride E, Bregman T, Kirkham TC. Endocannabinoids and food intake: newborn suckling and appetite regulation in adulthood. Exp Biol Med. 2005;230:225–234. doi: 10.1177/153537020523000401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia DE, Brown S, Hille B, Mackie K. Protein kinase C disrupts cannabinoid actions by phosphorylation of the CB1 cannabinoid receptor. J Neurosci. 1998;18:2834–2841. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-08-02834.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gong JP, Onaivi ES, Ishiguro H, Liu QR, Tagliaferro PA, Brusco A, Uhl GR. Cannabinoid CB2 receptors: immuno-histochemical localization in the rat brain. Brain Res. 2006;1071:10–23. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2005.11.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haney M, Rabkin J, Gunderson E, Foltin RW. Dronabinol and marijuana in HIV+ marijuana smokers: acute effects on caloric intake and mood. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;181:170–178. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-2242-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry DJ, Chavkin C. Activation of inwardly rectifying potassium channels (GIRK1) by co-expressed rat brain cannabinoid receptors in Xenopus oocytes. Neurosci Lett. 1995;186:91–94. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(95)11289-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hentges ST, Low MJ, Williams JT. Differential regulation of synaptic inputs by constitutively released endocannabinoids and exogenous cannabinoids. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9746–9751. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2769-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hillard CJ, Manna S, Greenberg MJ, Dicamelli R, Ross RA, Stevenson LA, Murphy V, Pertwee RG, Campbell WB. Synthesis and characterization of potent and selective agonists of the neuronal cannabinoid receptor (CB1) J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;289:1427–1433. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hille B. Potassium channels and chloride channels. In: Hille B, editor. Ionic Channels of Excitable Membranes. Sinauer Associates, Inc.; Sunderland, MA: 1992. pp. 115–139. [Google Scholar]

- Ho J, Cox JM, Wagner EJ. Cannabinoid-induced hyperphagia: correlation with inhibition of proopiomelanocortin neurons? Physiol Behav. 2007;92:507–519. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2007.04.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang H, Acuna-Goycolea C, Li Y, Cheng HM, Obrietan K, van den Pol AN. Cannabinoids excite hypothalamic melanin-concentrating hormone but inhibit hypocretin/orexin neurons: implications for cannabinoid actions on food intake and cognitive arousal. J Neurosci. 2007;27:4870–4881. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0732-07.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo YH, Chen YJL, Chua SC, Talmage DA, Role LW. Integration of endocannabinoid and leptin signaling in an appetite-related neural circuit. Neuron. 2005;48:1055–1066. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones AW, Holmgren A, Kugelberg FC. Driving under the influence of cannabis: a 10-year study of age and gender differences in the concentrations of tetrahydrocannabinol in blood. Addiction. 2008;103:452–461. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02091.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kola B, Farkas I, Christ-Crain M, Wittmann G, Lolli F, Amin F, Harvey-White J, Liposits Z, Kunos G, Grossman AB, Fekete C, Korbonits M. The orexigenic effect of ghrelin is mediated through central activation of the endogenous cannabinoid system. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1797. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lynch ME, Young J, Clark AJ. A case series of patients using medical marihuana for management of chronic pain under the Canadian Marihuana Medical Access Regulations. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2006;32:497–501. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2006.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackie K, Lai Y, Westenbroek R, Mitchell R. Cannabinoids activate an inwardly rectifying potassium conductance and inhibit Q-type calcium currents in AtT20 cells transfected with rat brain cannabinoid receptor. J Neurosci. 1995;15:6552–6561. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-10-06552.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marco EM, Llorente R, Moreno E, Biscaia JM, Guaza C, Viveros MP. Adolescent exposure to nicotine modifies acute functional responses to cannabinoid agonists in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2006;172:46–53. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2006.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mathew RJ, Wilson WH, Davis R. Postural syncope after marijuana: a transcranial Doppler study of the hemodynamics. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2003;75:309–318. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(03)00086-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McAllister SD, Griffin G, Satin LS, Abood ME. Cannabinoid receptors can activate and inhibit G protein-coupled inwardly rectifying potassium channels in a Xenopus oocyte expression system. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;291:618–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mu J, Zhuang SY, Kirby MT, Hampson RE, Deadwyler SA. Cannabinoid receptors differentially modulate potassium A and D currents in hippocampal neurons in culture. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;291:893–902. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narimatsu S, Watanabe K, Matsunaga T, Imaoka S, Funae Y, Yoshimura H. Cytochrome P-450 isozymes involved in the oxidative metabolism of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol by liver microsomes of adult female rats. Drug Metab Dispos. 1992;20:79–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narimatsu S, Watanabe K, Yamamoto I, Yoshimura H. Sex difference in the oxidative metabolism of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol in the rat. Biochem Pharmacol. 1991;41:1187–1194. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(91)90657-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen QH, Wagner EJ. Estrogen differentially modulates the cannabinoid-induced presynaptic inhibition of amino acid neurotransmission in proopiomelanocortin neurons of the arcuate nucleus. Neuroendocrinology. 2006;84:123–137. doi: 10.1159/000096996. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paton SM, Kandel DB. Psychological factors and adolescent illicit drug use: ethnicity and sex differences. Adolescence. 1978;13:187–200. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Penetar DM, Kouri EM, Gross MM, McCarthy EM, Rhee CK, Peters EN, Lukas SE. Transdermal nicotine alters some of marijuana's effects in male and female volunteers. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2005;79:211–223. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Reyes M, Owens SM, Di Guiseppi S. The clinical pharmacology and dynamics of marihuana cigarette smoking. J Clin Pharmacol. 1981;21:201S–207S. doi: 10.1002/j.1552-4604.1981.tb02596.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pope HG, Jacobs A, Mialet JP, Yurgelun-Todd D, Gruber S. Evidence for a sex-specific residual effect of cannabis on visuospatial memory. Psychother Psychosom. 1997;66:179–184. doi: 10.1159/000289132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez de Fonseca F, Cebeira M, Ramos JA, Martín M, Fernández-Ruiz JJ. Cannabinoid receptors in rat brain areas: sexual differences, fluctuations during estrous cycle and changes after gonadectomy and sex steroid treatment. Life Sci. 1994;54:159–170. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(94)00585-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rudy B. Diversity and ubiquity of K channels. Neuroscience. 1988;25:729–749. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(88)90033-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strasser F, Luftner D, Possinger K, Ernst G, Ruhstaller T, Meissner W, Ko YD, Schnelle M, Reif M, Cerny T. Comparison of orally administered cannabis extract and delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol in treating patients with cancer-related anorexia-cachexia syndrome: a multicenter, phase III, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial from the cannabis-study-group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3394–3400. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang SL, Tran V, Wagner EJ. Sex differences in the cannabinoid modulation of an A-type K+ current in neurons of the mammalian hypothalamus. J Neurophysiol. 2005;94:2983–2986. doi: 10.1152/jn.01187.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng AH, Craft RM. Sex differences in antinociceptive and motoric effects of cannabinoids. Eur J Pharmacol. 2001;430:41–47. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(01)01267-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tseng AH, Harding JW, Craft RM. Pharmacokinetic factors in sex differences in Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol-induced behavioral effects in rats. Behav Brain Res. 2004;154:77–83. doi: 10.1016/j.bbr.2004.01.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Sickle MD, Duncan M, Kingsley PJ, Mouihate A, Urbani P, Mackie K, Stella N, Makriyannis A, Piomelli D, Davison JS, Marnett LJ, Di Marzo V, Pittman QJ, Patel KD, Sharkey KA. Identification and functional characterization of brainstem cannabinoid CB2 receptors. Science. 2005;310:329–332. doi: 10.1126/science.1115740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh D, Kirkova J, Davis MP. The efficacy and tolerability of long-term use of dronabinol in cancer-related anorexia: a case series. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;30:493–495. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watanabe K, Matsunaga T, Narimatsu S, Yamamoto I, Yoshimura H. Sex difference in hepatic microsomal aldehyde oxygenase activity in different strains of mice. Res Commun Chem Pathol Pharmacol. 1992;78:373–376. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiley JL. Sex-dependent effects of Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol on locomotor activity in mice. Neurosci Lett. 2003;352:77–80. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2003.08.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woods SC, Gotoh K, Clegg DJ. Gender differences in the control of energy homeostasis. Exp Biol Med. 2003;228:1175–1180. doi: 10.1177/153537020322801012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woolridge E, Barton S, Samuel J, Osorio J, Dougherty A, Holdcroft A. Cannabis use in HIV for pain and other medical symptoms. J Pain Symptom Manage. 2005;29:358–367. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2004.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]