Abstract

Atopic dermatitis (AD), a common chronic inflammatory skin disease, is characterized by inflammatory cell skin infiltration. The JAK-STAT pathway has been shown to play an essential role in the dysregulation of immune responses in AD, including the exaggeration of Th2 cell response, the activation of eosinophils, the maturation of B cells, and the suppression of regulatory T cells (Tregs). In addition, the JAK-STAT pathway, activated by IL-4, also plays a critical role in the pathogenesis of AD by upregulating epidermal chemokines, pro-inflammatroy cytokines, and pro-angiogenic factors as well as by downregulating antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) and factors responsible for skin barrier function. In this review, we will highlight the recent advances in our understanding of the JAK-STAT pathway in the pathogenesis of AD.

Keywords: JAK-STAT, atopic dermatitis, Th2, skin, inflammation

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common skin disease manifested clinically by chronic inflammation and characterized histologically by skin infiltration of inflammatory cells including predominantly lymphocytes, eosinophils, and mast cells. It affects 10–20% of children and 1–3% of adults in developed countries,1 and the prevalence is increasing. Many of these patients also suffer from asthma and allergic rhinitis2 along with intense itching and skin infection. Although the pathogenesis and etiology of AD remain to be completely understood, this multifactorial disease likely results from a complex crosstalk between genetic and environmental factors. Exaggerated Th2 response, disruption of the epidermis barrier functions, high levels of serum IgE, and decreased production of antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) are the key findings in AD.3,4 Data from human and animal studies indicate that AD is a Th2 dominant inflammatory skin disease at the acute stage followed by Th1 involvement at the chronic stage of the disease.3-5 Specifically, this notion of Th2-dominance in AD is validated by a mouse model we have successfully generated through overexpressing IL-4, a key Th2 cytokine, in the basal epidermis using a epidermis-specific keratin 14 promoter.6 The IL-4 transgenic (Tg) mice spontaneously develop skin lesions, serological abnormalities, and skin infection, which fulfil the clinical and histological diagnostic criteria for human AD.6 Consistent with an inflammatory disease process, upregulation of chemokines,7,8 proinflammatory cytokines,5 B cell activation molecules,9 angiogenic factors,10,11 and several critical adhesion molecules12 has been found in these Tg mice.

The JAK-STAT pathway is a classical signal transduction pathway for numerous cytokines and growth factors. The binding of ligands to their receptors leads to JAK activation, which in turn phosphorylates and activates STATs. The activated STATs then translocate to the cell nucleus to regulate their target genes. The JAK family includes JAK1, JAK2, JAK3, and TYK2, and the STAT family includes STAT1, STAT2, STAT3, STAT5A/B, and STAT6. As a negative regulator of the JAK-STAT pathway, the SOCS family consists of cytokine-inducible SH2 domain-containing protein (CIS) and SOCS1–7. SOCSs may act on the activation loop of JAKs, or they may interact with phosphotyrosines in the cytoplasmic domain of cytokine receptors, suppressing the JAK-STAT pathway with a negative feedback mechanism.13 In this review, we will discuss the roles that the JAK-STAT pathway plays in the pathophysiology of AD.

JAK-STAT in Th2 Differentiation

Since AD is a Th2-dominant disease, examination of how the JAK-STAT pathway regulates Th2 differentiation would help us to understand the possible roles that JAK-STAT play in AD. It is well established that IL-4 promotes the differentiation of Th2 cells, which in turn produce IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13. The study of IL-4 and the IL-4 receptor α-null mice demonstrated clearly that IL-4 is required for a Th2 response and the production of Th2 cytokines.14,15 In addition, studies from the IL-4 Tg mice demonstrated upregulation of the Th2 cytokines.5 Consistently, the IL-4 Tg mice generated on a Th2-dominant strain, BALB/c mice, develop earlier onset and worse AD-like skin lesions than the IL-4 Tg mice generated on a Th1-dominant strain, C57BL/6 mice, suggesting that the Th2 systemic immune milieu, in addition to cutaneous Th2 immune milieu, plays an essential role in the pathogenesis of AD.16 Additionally, knocking out Bcl-6, a transcription factor functioning to regulate IL-4 signal transduction, leads to Th2-mediated hyperimmune response in many organs, further supporting the regulatory function of IL-4 on Th2 immunity.17 Importantly, IL-4 signals through the JAKs-STAT6 pathway to regulate Th2-related target genes in lymphocytes, firmly supporting a role of JAK-STAT in Th2 regulation.18

In addition to IL-4, other factors are also important for Th2 differentiation. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), known to promote Th2 differentiation, to activate natural killer T cells and basophils, and to affect B cell maturation, has been reported to be associated with AD.19 While the murine TSLP receptor signals via STAT3, STAT5/Tec, a Src type kinase, the human TSLP receptor activates STAT1, STAT3, STAT5/JAK1, and JAK2.20,21

It has been reported that histamine enhances the secretion of Th2 cytokines such as IL-4, IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13 and inhibits the production of Th1 cytokines.22 Histamine was shown to stimulate IL-13 production through the JAK-STAT pathway in a murine Th2 cell line.23 In addition, tyrphostin, a JAK-STAT pathway inhibitor, reversed the effects of histamine on IFNγ, IL-5, and IL-10 production.24 Horr et al. have shown that histamine, by acting through the H4 receptors on T cells, can suppress STAT1 activation and help to drive the Th2 response, leading to the development of AD.25

It is generally accepted that TYK2, JAK2, and STAT4, which are IL-12 signaling pathway components, are essential for Th1 cell differentiation, while JAK1, JAK3, and STAT6, which are IL-4 signaling components, are critical for Th2 differentiation.20 In addition, STAT5A/B, which are involved in the upregulation of GATA3 and IL-4Rα, and STAT3, which helps STAT6 bind to its target genes, also play some roles in Th2 cell differentiation.20,26,27

STAT6 regulates genes involved in Th2 and B cell differentiation, IgE class switching, and MHC class II production.15,18 While STAT4 null mice fail to generate Th1 cells and conditional STAT3 knockout mice have an exaggerated Th1 response,28 STAT6 null mice have impaired Th2 cell development and IgE class switching.29 On the contrary, mice expressing constitutively active STAT6 (STAT6VT) develop an AD-like skin lesion.30 In addition, several STAT6 polymorphisms are also associated with a predisposition to allergic diseases and high levels of IgE.31,32

JAK3 is expressed in natural killer cells, T cells, and B cells. A JAK3 mutation in severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID) patients leads to the absence of T cells and natural killer cells and the production of dysfunctional B cells.33 JAK3-null mice also have similar defects.34

In humans, a loss-of-function mutation in TYK2 leads to defects in multiple cytokine signaling pathways including type I IFN, IL-6, and IL-12.35-37 These patients showed impaired Th1 differentiation and accelerated Th2 differentiation with clinical manifestations including unusual susceptibility to various microorganism infections, AD-like skin lesions, and high serum IgE levels, suggesting a regulatory role of the JAK family in Th2 differentiation.

Another TYK2 null mutation and hypomorphic mutations in STAT3 are associated with the hyper-IgE syndrome (HIES), a primary immunodeficiency characterized by AD like-skin lesions, susceptibility to infections, and high serum IgE levels.38 In this syndrome, IL-12 and IFN/β signal pathways are defective, thus blocking the Th1 differentiation. As a result, the Th2 response is exaggerated, leading to similar clinical findings as AD.38 Because STAT3 is important for B cell proliferation and differentiation, HIES patients have decreased number of memory B cells as compared with AD patients.39

As a negative regulator of the JAK-STAT pathway, suppressor of cytokine signaling 2 (SOCS2) deletion leads to increased susceptibility to AD as compared with wild-type mice. These mice show an exaggerated Th2 response along with significantly elevated serum IgE levels, eosinophilia and low IL-17 levels. SOCS2-knockout CD4+ T cells display constitutively high levels of STAT6 phosphorylation as compared with wild type T cells.40 In addition, IL-2-induced STAT5 activation, also involved in the early Th2 differentiation, is exaggerated in the SOCS2-knockout CD4+ T cells.40 On the other hand, IL-12-stimulated STAT4 phosphorylation is unaffected, and IL-6 mediated STAT3 phosphorylation is inhibited. Since it is generally accepted that the development of the Th1, Th2, and Th17 immune responses are mediated by STAT4/STAT1, STAT6/STAT5, and STAT3 respectively,40,41 the increased STAT6/STAT5 activation and suppressed STAT3 activation naturally lead to an exaggerated Th2 response at the expense of Th17.40

Another example of the JAK family involvement in Th2 immunity is shown in NC/Nga mice that develop AD-like skin inflammation. Nakagawa et al. reported that Pyridone 6 (P6), a pan-JAK inhibitor, delayeded the onset and reduced the severity of AD-like skin lesions in NC/Nga mice.42 P6 suppressed the IFN-γ/STAT1, IL-2/STAT5, and IL-4/STAT6 signaling pathways strongly while it suppressed IL-6/STAT3 pathway only modestly, resulting in reduction of the Th1 and Th2 responses but the enhancement of the T17 response.42

JAK-STAT in Eosinophils

Eosinophil skin infiltration is frequently observed in the skin lesions of AD patients and AD mouse models.43-46 Although STAT6 null mice have defects in Th2 differentiation and IgE class switching,47 crossing these mice with NC/Nga mice cannot prevent the development of AD-like skin lesions.48 Even though these mice do not produce IgE and Th2 cytokines, the histological features of their skin lesions are similar to that of AD.48 These authors suggested that a Th2 response is not absolutely necessary for the development of AD-like skin lesions; instead, IFN- γ and eosinophil skin infiltration may play an essential role.48

Eosinophils express the IL-31 receptor A (IL-31RA),49 and IL-31 has the ability to delay the apoptosis of eosinophils and to stimulate the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines through JAK-STAT.49,50 In addition, IL-5, mainly involved in B cell proliferation and differentiation, was shown to induce eosinophilia when upregulated.51 Conversely IL-5 or IL-5 receptor α chain (IL-5Rα) null mice show defects in B cells and eosinophils.52 In eosinophils, IL-5 signals through the JAK2-STAT1/STAT5 and MAP kinases pathways to regulate genes involved in cell proliferation, survival and effector functions.52-54

JAK-STAT in Tregs

In the skin, regulatory T cells (Tregs) help to regulate the immune response, and in AD, Treg function is suppressed.55-57 Depleting Treg cells significantly increased the severity of the skin inflammation in OVA-sensitized mice.58 In T cells, IL-4-activated STAT6 upregulates GATA3, the master regulator of Th2 cells. GATA3 in turn suppresses Foxp3, the master regulator in Treg cells.59 This regulatory pathway could possibly explain why Treg function is suppressed in AD. In addition, STAT5A/B and STAT3 may also play important roles in the regulation of Foxp3.60 On the other hand, Foxp3 can also suppress GATA3’s ability to regulate Th2 genes.59 It was reported that the IFN-γ gene transfer stimulates Treg related cytokines and improves AD-like symptoms of NC/Nga mice.61 This finding, however, seems to contradict the notion that IFN- γ is a promoting factor for AD.48 On the clinical level, treatment with a low-dose cyclosporine A is effective in reducing skin inflammation with simultaneous increase of Treg population in AD patients, further supporting a role of Treg in AD.62

JAK-STAT in Th17 Cells

STAT3, mediating the IL-23 and IL-6 pathways, is critical for the differentiation of Th17 Cell.63,64 In the early stage of human AD, the number of Th17 cells is increased,3 and IL-17 has been reported to upregulate adhesion molecules on keratinocytes, enhancing T cell-keratinocyte adhesion and T cell-mediated cytotoxicity.65 However, in chronic AD, the Th17 pathway is suppressed,66 which could account for the AMP deficiency in AD.3

JAK-STAT in Mast Cells

In the skin lesions of AD patients as well as AD mouse models, the number of mast cells is increased.6,67 IL-9 stimulates VEGF production from human mast cells through the activation of STAT3 in an in vitro experiment.68 Interestingly, IL-9 serum levels in AD patients are not different from those of non-AD controls even though IL-9 and its receptors are upregulated in the lesional skin of the AD patients,68 suggesting that the upregulation of VEGF in mast cells via IL-9 may be a localized cutaneous phenomenon. The prominent increase of mast cell VEGF production and angiogenesis in an AD animal model also supports the role of JAK-STAT in this immune pathway10,11

JAK-STAT in Epidermal Keratinocytes

Being a major cell type of the skin and possessing the ability to participate in various immune responses, epidermal keratinocytes are likely an active player in the skin inflammation of AD.69,70 We and others have shown that the dysregulation of the keratinocyte genes by IL-4 play an important role in AD.8,71-74 Two types of IL-4 receptors have been identified. The type I receptor consisting of IL-4Rα and IL-2Rγc chains is expressed in hematopoietic cells, while the type II receptor consisting of IL-4Rα and IL-13Rα1 is expressed in other cell types including keratinocytes.75,76

In keratinocytes, both IL-4 AND IL-13 binds to IL-4Rα and IL-13R1. IL-13Rα2, which was reported as a dominant negative inhibitor for both IL-4 and IL-13, binds to IL-13 with high affinity, but lacks a significant cytoplasmic domain.77 We have previously reported that IL-13Rα2 is upregulated by IL-4 in keratinocytes.71 In AD patients this gene is similarly upregulated.78 This may be due to a negative feedback mechanism available to keratinocytes to maintain homeostasis.

We have also shown that IL-4 upregulates chemokines CCL8, CCL24, CCL25, CCL26, CCL3L1, CXCL6, and CXCL16,8,71 all known for their roles in the pathophyisology of AD. The eotaxin subfamily that consists of CCL11/eotaxin-1, CCL24/eotaxin-2, and CCL26/eotaxin-3 plays an important role in AD.43,79,80 Eotaxins bind to the chemokine cysteine–cysteine receptor 3 (CCR3), which are expressed predominantly on eosinophils, recruiting these cells to the inflammatory site. Skin infiltrating eosinophils release a variety of cytotoxic granule proteins to cause tissue damage.44 In the regulation of CCL26, though both STAT3 and STAT6 are phosphorylated by IL-4, only STAT6 is functionally activated.8 Detailed analysis of the promoter of the CCL26 gene has shown that the STAT6 response element consists of two palindromic half sites TTC and GAA spaced by four nucleotides. Others also reported that STAT6, different from other STAT members, prefers the STAT sites with four spacing nucleotides.81 In addition to tyrosine phosphorylation, STAT3 activation may also involve serine phosphorylation82 and lysine acetylation.83 Knockout mice studies indirectly support our results in that while STAT6 null mice demonstrated defects in eosinophil tissue infiltration,29,84 the STAT3 Cre-loxP knockout mice did not show similar defects.29 Furthermore, IL-4 and IL-13 double knockout mice, when sensitized with ovalbumin, develop a skin lesion characterized by intact CD4+ dermal infiltration, severely diminished eosinophil infiltration, and undetectable OVA-specific IgE levels,85 suggesting that STAT6 activation is required for eosinophil skin infiltration in AD.

In addition to chemokines, IL-4 also upregulates pro-inflammatory factors, such as IL-1α, IL-19, IL-20, IL-25, IL-27, IL-12Rβ2, IL31RA, and nitric oxide synthase 2 (NOS2).71 Moreover, we demonstrated that IL-4 signals through the JAK-STAT pathway to regulate IL-19 expression in keratinocytes.86

Using PCR array, we have found that that IL-4 upregulates angiogenic or lymphangiogenic-related genes, such as VEGF, ANG-1, ANGL-4, IGF1, Notch4, PGF, and MCP-1.11,71 Using the IL-4 Tg mice and cell culture, we showed that CD11b+ macrophages attracted to the skin lesion by MCP-1 may account for lymphangiogenesis observed in AD by secreting VEGF-C.11

While IL-4 upregulates chemokines, pro-inflammatory factors, angiogenic factors in keratinocytes, it downregulates antimicrobial peptides (AMPs) or factors involved in APM production.71 Other groups have also demonstrated that the dysregulation of AMPs affects the development of AD.87 Human β-defensin-3 (HBD-3), which is significantly decreased in AD, is downregulated by IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13.88 In addition, HBD-2 and human cathelicidin (LL-37) were also found to be reduced in AD skin lesions as compared with psoriasis.89 Howell et al. suggested that low levels of LL-37 suppressed by IL-4 and IL-13 through STAT6 may be the mechanism responsible for increased vaccinia virus replication as occurred in eczema vaccinatum of AD patients.90

Skin barrier function defects are critical for the development of AD.91 In addition to the filaggrin mutations in some AD patients, cytokines are now known to induce the downregulation of several barrier proteins. Loricrin and involucrin are two important factors for skin barrier function. They are downregulated by IL-4 and IL-13 in keratinocytes, and in STAT6 transgenic mice, their expression is significantly decreased as well.92 In addition, filaggrin, which is reduced in acute AD skin lesion, is also suppressed by IL-4 and IL-13 in keratinocytes.93 Interestingly, while IL-4 markedly reduces ceramide levels in the epidermis by downregulating the expression of serine-palmitoyl transferase-2, acid sphingomyelinase, and β-glucocerebrosidase, Th1 cytokines (GM-CSF/IFN-γ/TNF-α) increase the ceramide levels.94

Taken together, the role that IL-4 plays in the dysregulation of keratincoyte functions in AD involves the upregulation of chemokines, pro-inflammatory factors, and pro-angiogenic factors and the downregulation of AMPs and factors responsible for skin barrier function.

Pruritis in AD is induced by complicated crosstalks among keratinocytes, immune cells, and nerve fibers.95 The data from the Nc/Nga mice studies indicate that although IL-4 is a key mediator of the inflammatory process in AD, IL-31 might be the key causative factor for pruitus.50 In addition, IL-31 transgenic mice developed a Th2 immune response with severe pruritic skin lesions similar to AD.96

IL-31 is upregulated in the skin of AD patients, and it induces the itching sensation either by direct stimulation of the dorsal root ganglion fibers that express IL-31RA or by indirect stimulation of pruritic factors from keratinocytes.50,97 IL-31 receptor activation in keratinocytes induces calcium influx and STAT3 mediated β-endorphin production, which may contribute to the peripheral itching in AD.98

Conclusion

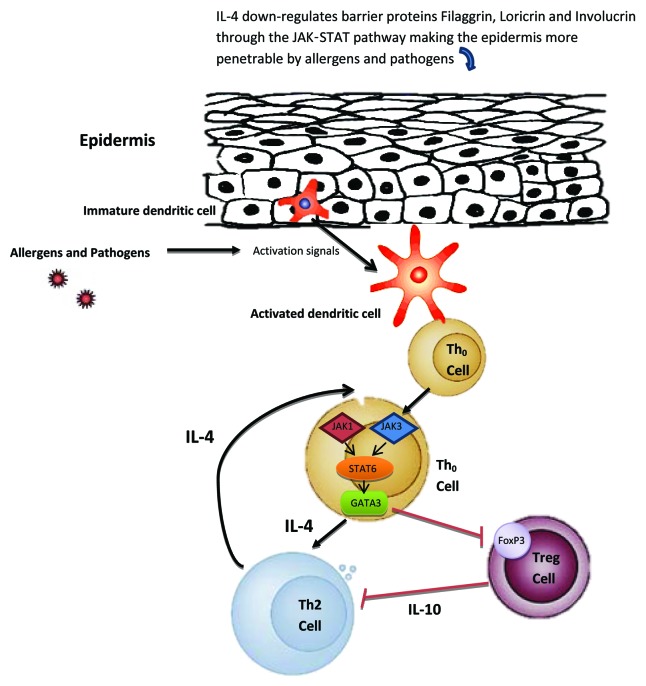

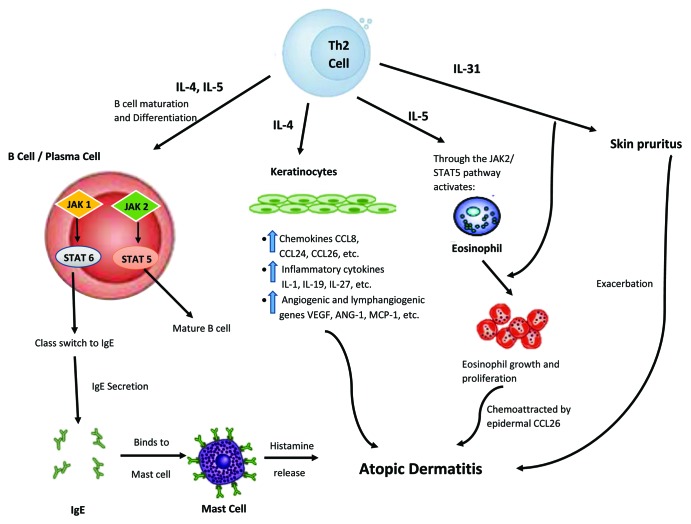

Thus far, data from our laboratory and others seem to indicate an influential role of JAK-STAT in the pathogenesis of AD, with IL-4 being a key mediator (Figs. 1 and 2). Specifically, the JAK-STAT pathway is instrumental for the Th2 cell differentiation. In the immune milieu of AD, the enhancement of Th2 cell proliferation and their release of various cytokines via the JAK-STAT pathway is likely the critical factor for the inflammatory responses in AD. This Th2 immune upregulation could then lead to B cell maturation and plasma cell differentiation, resulting in the hyper-secretion of IgE. IgE binding to skin mast cells causes histamine release, which further exacerbates AD. Similarly, this hyper Th2 immune milieu triggers epidermal cells to release various chemokines, pro-inflammatory cytokines, and angiogenic factors that participate in AD pathophysiology. Moreover, IL-5 released from this hyper Th2 milieu could activate eosinophils that are attracted to the skin by the eotaxin subfamily, further worsening the AD condition. In addition, by way of IL-31, an inducer of pruritus, AD becomes increasingly intensified.

Figure 1. Proposed mechanism of JAK-STAT involvement in atopic dermatitis (AD) development, part I. Skin barrier function defects are critical for the development of AD. In addition to the filaggrin gene mutation defects in some AD patients, IL-4 is also able to downregulate barrier proteins filaggrin, loricrin and involucrin through the JAK-STAT pathway making the epidermis more penetrable by allergens and pathogens. Once penetrated through the epidermis, allergens/pathogens are detected by dendritic cells, which become subsequently activated to present these antigens to naïve Th0 cells. The Th0 cell can then differentiate into the Th2 cell through the JAK1,3-STAT6 pathway under the influence of IL-4. In the Th0 cells, the STAT6 pathway can also upregulate GATA3, a master regulator of Th2 cells. GATA3 in turn suppresses Foxp3, the master regulator in Treg cells, thus allowing more T cells to be activated. Black arrows indicate activation pathway. Red lines indicate inhibition pathway.

Figure 2. Proposed mechanism of JAK-STAT involvement in atopic dermatitis (AD) development, part II. Here, Th2 cells play a significant role. By their abilities to provide IL-4 and IL-5 stimulation via the JAK-STAT pathway, immature B cells could be differentiated into mature B cell and plasma cells would undergo antibody heavy chain switching to IgE class. The subsequent binding of IgE to skin mast cells could lead to release of histamine, which is known to exacerbate AD. Similarly, this hyper Th2 immune milieu, particularly IL-4, could trigger epidermal cells to produce and release various chemokines (such as CCL26), pro-inflammatory cytokines, and angiogenic factors, leading to AD pathophysiology. Moreover, IL-5 released from this hyper Th2 milieu could, through JAK-STAT pathway, activate eosinophils, and attract them to the skin via CCL26, further worsening the AD condition. In addition, by way of IL-31, an inducer of pruritus, AD symptoms could become increasingly intensified. Black arrows indicate activation pathway. Red lines indicate inhibition pathway.

Our understanding of the JAK-STAT pathway and its relationship to the dysregulated immune response and keratinocyte function is still in its infancy. We have many unanswered questions. What are JAKs’ and STATs’ tissue-specific functions? How does the JAK-STAT pathway crosstalk with other pathways in AD? What exact roles do the different JAKs and STATs play in the pathogenesis of AD? Answering these questions will enable us to target more specifically the key components of the complex pathophysiology of AD, thus providing the best treatment for this disease.

Acknowledgments

This work is in part supported by the Albert H. and Mary Jane Slepyn Endowed Fellowship (L.B.), and the Dr Orville J. Stone Endowed Professorship (L.S.C.).

Glossary

Abbreviations:

- AD

atopic dermatitis

- AMP

antimicrobial peptide

- Tg

transgenic

- SOCS

suppressor of cytokine signaling

- CIS

cytokine-inducible SH2 domain-containing protein

- TSLP

thymic stromal lymphopoietin

- SCID

severe combined immunodeficiency

- HIES

hyper-IgE syndrome

- IL-31RA

IL-31 receptor A

- Tregs

regulatory T cells

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/jak-stat/article/24137

References

- 1.Saito H. Much atopy about the skin: genome-wide molecular analysis of atopic eczema. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2005;137:319–25. doi: 10.1159/000086464. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kapoor R, Menon C, Hoffstad O, Bilker W, Leclerc P, Margolis DJ. The prevalence of atopic triad in children with physician-confirmed atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:68–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2007.06.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guttman-Yassky E, Nograles KE, Krueger JG. Contrasting pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis--part II: immune cell subsets and therapeutic concepts. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1420–32. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guttman-Yassky E, Nograles KE, Krueger JG. Contrasting pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis--part I: clinical and pathologic concepts. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1110–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.01.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen L, Martinez O, Overbergh L, Mathieu C, Prabhakar BS, Chan LS. Early up-regulation of Th2 cytokines and late surge of Th1 cytokines in an atopic dermatitis model. Clin Exp Immunol. 2004;138:375–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2004.02649.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan LS, Robinson N, Xu L. Expression of interleukin-4 in the epidermis of transgenic mice results in a pruritic inflammatory skin disease: an experimental animal model to study atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2001;117:977–83. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-202x.2001.01484.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chen L, Lin SX, Agha-Majzoub R, Overbergh L, Mathieu C, Chan LS. CCL27 is a critical factor for the development of atopic dermatitis in the keratin-14 IL-4 transgenic mouse model. Int Immunol. 2006;18:1233–42. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxl054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bao L, Shi VY, Chan LS. IL-4 regulates chemokine CCL26 in keratinocytes through the Jak1, 2/Stat6 signal transduction pathway: Implication for atopic dermatitis. Mol Immunol. 2012;50:91–7. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2011.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen L, Lin SX, Overbergh L, Mathieu C, Chan LS. The disease progression in the keratin 14 IL-4-transgenic mouse model of atopic dermatitis parallels the up-regulation of B cell activation molecules, proliferation and surface and serum IgE. Clin Exp Immunol. 2005;142:21–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2005.02894.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen L, Marble DJ, Agha R, Peterson JD, Becker RP, Jin T, et al. The progression of inflammation parallels the dermal angiogenesis in a keratin 14 IL-4-transgenic model of atopic dermatitis. Microcirculation. 2008;15:49–64. doi: 10.1080/10739680701418416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi VY, Bao L, Chan LS. Inflammation-driven dermal lymphangiogenesis in atopic dermatitis is associated with CD11b+ macrophage recruitment and VEGF-C up-regulation in the IL-4-transgenic mouse model. Microcirculation. 2012;19:567–79. doi: 10.1111/j.1549-8719.2012.00189.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen L, Lin SX, Amin S, Overbergh L, Maggiolino G, Chan LS. VCAM-1 blockade delays disease onset, reduces disease severity and inflammatory cells in an atopic dermatitis model. Immunol Cell Biol. 2010;88:334–42. doi: 10.1038/icb.2009.107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Alexander WS, Hilton DJ. The role of suppressors of cytokine signaling (SOCS) proteins in regulation of the immune response. Annu Rev Immunol. 2004;22:503–29. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.22.091003.090312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kopf M, Le Gros G, Bachmann M, Lamers MC, Bluethmann H, Köhler G. Disruption of the murine IL-4 gene blocks Th2 cytokine responses. Nature. 1993;362:245–8. doi: 10.1038/362245a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pernis AB, Rothman PB. JAK-STAT signaling in asthma. J Clin Invest. 2002;109:1279–83. doi: 10.1172/JCI15786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Reichle ME, Chen L, Lin SX, Chan LS. The Th2 systemic immune milieu enhances cutaneous inflammation in the K14-IL-4-transgenic atopic dermatitis model. J Invest Dermatol. 2011;131:791–4. doi: 10.1038/jid.2010.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ye BH, Cattoretti G, Shen Q, Zhang J, Hawe N, de Waard R, et al. The BCL-6 proto-oncogene controls germinal-centre formation and Th2-type inflammation. Nat Genet. 1997;16:161–70. doi: 10.1038/ng0697-161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Goenka S, Kaplan MH. Transcriptional regulation by STAT6. Immunol Res. 2011;50:87–96. doi: 10.1007/s12026-011-8205-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang Y, Zhou B. Functions of thymic stromal lymphopoietin in immunity and disease. Immunol Res. 2012;52:211–23. doi: 10.1007/s12026-012-8264-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.O’Shea JJ, Plenge R. JAK and STAT signaling molecules in immunoregulation and immune-mediated disease. Immunity. 2012;36:542–50. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wohlmann A, Sebastian K, Borowski A, Krause S, Friedrich K. Signal transduction by the atopy-associated human thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP) receptor depends on Janus kinase function. Biol Chem. 2010;391:181–6. doi: 10.1515/bc.2010.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Packard KA, Khan MM. Effects of histamine on Th1/Th2 cytokine balance. Int Immunopharmacol. 2003;3:909–20. doi: 10.1016/S1567-5769(02)00235-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Elliott KA, Osna NA, Scofield MA, Khan MM. Regulation of IL-13 production by histamine in cloned murine T helper type 2 cells. Int Immunopharmacol. 2001;1:1923–37. doi: 10.1016/S1567-5769(01)00117-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Osna N, Elliott K, Chaika O, Patterson E, Lewis RE, Khan MM. Histamine utilizes JAK-STAT pathway in regulating cytokine production. Int Immunopharmacol. 2001;1:759–62. doi: 10.1016/S1567-5769(01)00009-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Horr B, Borck H, Thurmond R, Grösch S, Diel F. STAT1 phosphorylation and cleavage is regulated by the histamine (H4) receptor in human atopic and non-atopic lymphocytes. Int Immunopharmacol. 2006;6:1577–85. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2006.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Stritesky GL, Muthukrishnan R, Sehra S, Goswami R, Pham D, Travers J, et al. The transcription factor STAT3 is required for T helper 2 cell development. Immunity. 2011;34:39–49. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2010.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liao W, Schones DE, Oh J, Cui Y, Cui K, Roh TY, et al. Priming for T helper type 2 differentiation by interleukin 2-mediated induction of interleukin 4 receptor alpha-chain expression. Nat Immunol. 2008;9:1288–96. doi: 10.1038/ni.1656. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Takeda K, Clausen BE, Kaisho T, Tsujimura T, Terada N, Förster I, et al. Enhanced Th1 activity and development of chronic enterocolitis in mice devoid of Stat3 in macrophages and neutrophils. Immunity. 1999;10:39–49. doi: 10.1016/S1074-7613(00)80005-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Akira S. Functional roles of STAT family proteins: lessons from knockout mice. Stem Cells. 1999;17:138–46. doi: 10.1002/stem.170138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sehra S, Bruns HA, Ahyi AN, Nguyen ET, Schmidt NW, Michels EG, et al. IL-4 is a critical determinant in the generation of allergic inflammation initiated by a constitutively active Stat6. J Immunol. 2008;180:3551–9. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.3551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Weidinger S, Klopp N, Wagenpfeil S, Rümmler L, Schedel M, Kabesch M, et al. Association of a STAT 6 haplotype with elevated serum IgE levels in a population based cohort of white adults. J Med Genet. 2004;41:658–63. doi: 10.1136/jmg.2004.020263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tamura K, Arakawa H, Suzuki M, Kobayashi Y, Mochizuki H, Kato M, et al. Novel dinucleotide repeat polymorphism in the first exon of the STAT-6 gene is associated with allergic diseases. Clin Exp Allergy. 2001;31:1509–14. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.2001.01191.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Russell SM, Tayebi N, Nakajima H, Riedy MC, Roberts JL, Aman MJ, et al. Mutation of Jak3 in a patient with SCID: essential role of Jak3 in lymphoid development. Science. 1995;270:797–800. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5237.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ortmann RA, Cheng T, Visconti R, Frucht DM, O’Shea JJ. Janus kinases and signal transducers and activators of transcription: their roles in cytokine signaling, development and immunoregulation. Arthritis Res. 2000;2:16–32. doi: 10.1186/ar66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Minegishi Y, Saito M, Morio T, Watanabe K, Agematsu K, Tsuchiya S, et al. Human tyrosine kinase 2 deficiency reveals its requisite roles in multiple cytokine signals involved in innate and acquired immunity. Immunity. 2006;25:745–55. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Saito M, Nagasawa M, Takada H, Hara T, Tsuchiya S, Agematsu K, et al. Defective IL-10 signaling in hyper-IgE syndrome results in impaired generation of tolerogenic dendritic cells and induced regulatory T cells. J Exp Med. 2011;208:235–49. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang Q, Su HC. Hyperimmunoglobulin E syndromes in pediatrics. Curr Opin Pediatr. 2011;23:653–8. doi: 10.1097/MOP.0b013e32834c7f65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Minegishi Y, Karasuyama H. Defects in Jak-STAT-mediated cytokine signals cause hyper-IgE syndrome: lessons from a primary immunodeficiency. Int Immunol. 2009;21:105–12. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Speckmann C, Enders A, Woellner C, Thiel D, Rensing-Ehl A, Schlesier M, et al. Reduced memory B cells in patients with hyper IgE syndrome. Clin Immunol. 2008;129:448–54. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2008.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Knosp CA, Carroll HP, Elliott J, Saunders SP, Nel HJ, Amu S, et al. SOCS2 regulates T helper type 2 differentiation and the generation of type 2 allergic responses. J Exp Med. 2011;208:1523–31. doi: 10.1084/jem.20101167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O’Shea JJ, Lahesmaa R, Vahedi G, Laurence A, Kanno Y. Genomic views of STAT function in CD4+ T helper cell differentiation. Nat Rev Immunol. 2011;11:239–50. doi: 10.1038/nri2958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakagawa R, Yoshida H, Asakawa M, Tamiya T, Inoue N, Morita R, et al. Pyridone 6, a pan-JAK inhibitor, ameliorates allergic skin inflammation of NC/Nga mice via suppression of Th2 and enhancement of Th17. J Immunol. 2011;187:4611–20. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1100649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Owczarek W, Paplińska M, Targowski T, Jahnz-Rózyk K, Paluchowska E, Kucharczyk A, et al. Analysis of eotaxin 1/CCL11, eotaxin 2/CCL24 and eotaxin 3/CCL26 expression in lesional and non-lesional skin of patients with atopic dermatitis. Cytokine. 2010;50:181–5. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2010.02.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Kapp A. [The role of eosinophilic granulocytes for the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis /neurodermatitis. Eosinophilic products as markers of disease activity] Hautarzt. 1993;44:432–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Leiferman KM, Ackerman SJ, Sampson HA, Haugen HS, Venencie PY, Gleich GJ. Dermal deposition of eosinophil-granule major basic protein in atopic dermatitis. Comparison with onchocerciasis. N Engl J Med. 1985;313:282–5. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198508013130502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chen L, Overbergh L, Mathieu C, Chan LS. The development of atopic dermatitis is independent of Immunoglobulin E up-regulation in the K14-IL-4 SKH1 transgenic mouse model. Clin Exp Allergy. 2008;38:1367–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2008.02987.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shimoda K, van Deursen J, Sangster MY, Sarawar SR, Carson RT, Tripp RA, et al. Lack of IL-4-induced Th2 response and IgE class switching in mice with disrupted Stat6 gene. Nature. 1996;380:630–3. doi: 10.1038/380630a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yagi R, Nagai H, Iigo Y, Akimoto T, Arai T, Kubo M. Development of atopic dermatitis-like skin lesions in STAT6-deficient NC/Nga mice. J Immunol. 2002;168:2020–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.168.4.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cheung PF, Wong CK, Ho AW, Hu S, Chen DP, Lam CW. Activation of human eosinophils and epidermal keratinocytes by Th2 cytokine IL-31: implication for the immunopathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. Int Immunol. 2010;22:453–67. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxq027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cornelissen C, Lüscher-Firzlaff J, Baron JM, Lüscher B. Signaling by IL-31 and functional consequences. Eur J Cell Biol. 2012;91:552–66. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcb.2011.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Molfino NA, Gossage D, Kolbeck R, Parker JM, Geba GP. Molecular and clinical rationale for therapeutic targeting of interleukin-5 and its receptor. Clin Exp Allergy. 2012;42:712–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03854.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takatsu K, Nakajima H. IL-5 and eosinophilia. Curr Opin Immunol. 2008;20:288–94. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kotsimbos AT, Hamid Q. IL-5 and IL-5 receptor in asthma. Mem Inst Oswaldo Cruz. 1997;92(Suppl 2):75–91. doi: 10.1590/S0074-02761997000800012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Ochiai K, Tanabe E, Ishihara C, Kagami M, Sugiyama T, Sueishi M, et al. Role of JAK2 signal transductional pathway in activation and survival of human peripheral eosinophils by interferon-gamma (IFN-gamma) Clin Exp Immunol. 1999;118:340–3. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.1999.01068.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Honda T, Miyachi Y, Kabashima K. Regulatory T cells in cutaneous immune responses. J Dermatol Sci. 2011;63:75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2011.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Agrawal R, Wisniewski JA, Woodfolk JA. The role of regulatory T cells in atopic dermatitis. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2011;41:112–24. doi: 10.1159/000323305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hayashida S, Uchi H, Moroi Y, Furue M. Decrease in circulating Th17 cells correlates with increased levels of CCL17, IgE and eosinophils in atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol Sci. 2011;61:180–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2010.10.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Fyhrquist N, Lehtimäki S, Lahl K, Savinko T, Lappeteläinen AM, Sparwasser T, et al. Foxp3+ cells control Th2 responses in a murine model of atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132:1672–80. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Chapoval S, Dasgupta P, Dorsey NJ, Keegan AD. Regulation of the T helper cell type 2 (Th2)/T regulatory cell (Treg) balance by IL-4 and STAT6. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;87:1011–8. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1209772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Yao Z, Kanno Y, Kerenyi M, Stephens G, Durant L, Watford WT, et al. Nonredundant roles for Stat5a/b in directly regulating Foxp3. Blood. 2007;109:4368–75. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-11-055756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Watcharanurak K, Nishikawa M, Takahashi Y, Kabashima K, Takahashi R, Takakura Y. Regulation of immunological balance by sustained interferon-γ gene transfer for acute phase of atopic dermatitis in mice. Gene Ther. 2012;20:538–44. doi: 10.1038/gt.2012.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Brandt C, Pavlovic V, Radbruch A, Worm M, Baumgrass R. Low-dose cyclosporine A therapy increases the regulatory T cell population in patients with atopic dermatitis. Allergy. 2009;64:1588–96. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Yang XO, Panopoulos AD, Nurieva R, Chang SH, Wang D, Watowich SS, et al. STAT3 regulates cytokine-mediated generation of inflammatory helper T cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:9358–63. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600321200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hirahara K, Ghoreschi K, Laurence A, Yang XP, Kanno Y, O’Shea JJ. Signal transduction pathways and transcriptional regulation in Th17 cell differentiation. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2010;21:425–34. doi: 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2010.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cavani A, Pennino D, Eyerich K. Th17 and Th22 in skin allergy. Chem Immunol Allergy. 2012;96:39–44. doi: 10.1159/000331870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Guttman-Yassky E, Lowes MA, Fuentes-Duculan J, Zaba LC, Cardinale I, Nograles KE, et al. Low expression of the IL-23/Th17 pathway in atopic dermatitis compared to psoriasis. J Immunol. 2008;181:7420–7. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.7420. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Kawakami T, Ando T, Kimura M, Wilson BS, Kawakami Y. Mast cells in atopic dermatitis. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:666–78. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sismanopoulos N, Delivanis DA, Alysandratos KD, Angelidou A, Vasiadi M, Therianou A, et al. IL-9 induces VEGF secretion from human mast cells and IL-9/IL-9 receptor genes are overexpressed in atopic dermatitis. PLoS One. 2012;7:e33271. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0033271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Esche C, de Benedetto A, Beck LA. Keratinocytes in atopic dermatitis: inflammatory signals. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2004;4:276–84. doi: 10.1007/s11882-004-0071-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pastore S, Mascia F, Girolomoni G. The contribution of keratinocytes to the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. Eur J Dermatol. 2006;16:125–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Bao L, Shi VY, Chan LS. IL-4 up-regulates epidermal chemotactic, angiogenic, and pro-inflammatory genes and down-regulates antimicrobial genes in vivo and in vitro: Relevant in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. Cytokine 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hatano Y, Adachi Y, Elias PM, Crumrine D, Sakai T, Kurahashi R, et al. The Th2 cytokine, interleukin-4, abrogates the cohesion of normal stratum corneum in mice: implications for pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. Exp Dermatol. 2013;22:30–5. doi: 10.1111/exd.12047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Brandt EB, Sivaprasad U. Th2 Cytokines and Atopic Dermatitis. J Clin Cell Immunol. 2011;2 doi: 10.4172/2155-9899.1000110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Howell MD, Fairchild HR, Kim BE, Bin L, Boguniewicz M, Redzic JS, et al. Th2 cytokines act on S100/A11 to downregulate keratinocyte differentiation. J Invest Dermatol. 2008;128:2248–58. doi: 10.1038/jid.2008.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Jiang H, Harris MB, Rothman P. IL-4/IL-13 signaling beyond JAK/STAT. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2000;105:1063–70. doi: 10.1067/mai.2000.107604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Wery-Zennaro S, Letourneur M, David M, Bertoglio J, Pierre J. Binding of IL-4 to the IL-13Ralpha(1)/IL-4Ralpha receptor complex leads to STAT3 phosphorylation but not to its nuclear translocation. FEBS Lett. 1999;464:91–6. doi: 10.1016/S0014-5793(99)01680-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wu AH, Low WC. Molecular cloning and identification of the human interleukin 13 alpha 2 receptor (IL-13Ra2) promoter. Neuro Oncol. 2003;5:179–87. doi: 10.1215/S1152851702000510. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Hussein YM, Ahmad AS, Ibrahem MM, Elsherbeny HM, Shalaby SM, El-Shal AS, et al. Interleukin 13 receptors as biochemical markers in atopic patients. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2011;21:101–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Yawalkar N, Uguccioni M, Schärer J, Braunwalder J, Karlen S, Dewald B, et al. Enhanced expression of eotaxin and CCR3 in atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 1999;113:43–8. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.1999.00619.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Kagami S, Kakinuma T, Saeki H, Tsunemi Y, Fujita H, Nakamura K, et al. Significant elevation of serum levels of eotaxin-3/CCL26, but not of eotaxin-2/CCL24, in patients with atopic dermatitis: serum eotaxin-3/CCL26 levels reflect the disease activity of atopic dermatitis. Clin Exp Immunol. 2003;134:309–13. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2249.2003.02273.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Ehret GB, Reichenbach P, Schindler U, Horvath CM, Fritz S, Nabholz M, et al. DNA binding specificity of different STAT proteins. Comparison of in vitro specificity with natural target sites. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:6675–88. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M001748200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Decker T, Kovarik P. Serine phosphorylation of STATs. Oncogene. 2000;19:2628–37. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yuan ZL, Guan YJ, Chatterjee D, Chin YE. Stat3 dimerization regulated by reversible acetylation of a single lysine residue. Science. 2005;307:269–73. doi: 10.1126/science.1105166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Miyata S, Matsuyama T, Kodama T, Nishioka Y, Kuribayashi K, Takeda K, et al. STAT6 deficiency in a mouse model of allergen-induced airways inflammation abolishes eosinophilia but induces infiltration of CD8+ T cells. Clin Exp Allergy. 1999;29:114–23. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2222.1999.00405.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.He R, Kim HY, Yoon J, Oyoshi MK, MacGinnitie A, Goya S, et al. Exaggerated IL-17 response to epicutaneous sensitization mediates airway inflammation in the absence of IL-4 and IL-13. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:761–70, e1. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.07.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Bao L, Alexander J, Shi VY, Chan LS. IL-4 up-regulates epidermal IL-19 expression in atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2012;132(Suppl 1):S1–S18. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.79. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Schittek B. The antimicrobial skin barrier in patients with atopic dermatitis. Curr Probl Dermatol. 2011;41:54–67. doi: 10.1159/000323296. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Howell MD, Boguniewicz M, Pastore S, Novak N, Bieber T, Girolomoni G, et al. Mechanism of HBD-3 deficiency in atopic dermatitis. Clin Immunol. 2006;121:332–8. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Howell MD, Novak N, Bieber T, Pastore S, Girolomoni G, Boguniewicz M, et al. Interleukin-10 downregulates anti-microbial peptide expression in atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2005;125:738–45. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-202X.2005.23776.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Howell MD, Gallo RL, Boguniewicz M, Jones JF, Wong C, Streib JE, et al. Cytokine milieu of atopic dermatitis skin subverts the innate immune response to vaccinia virus. Immunity. 2006;24:341–8. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Wolf R, Wolf D. Abnormal epidermal barrier in the pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis. Clin Dermatol. 2012;30:329–34. doi: 10.1016/j.clindermatol.2011.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Kim BE, Leung DY, Boguniewicz M, Howell MD. Loricrin and involucrin expression is down-regulated by Th2 cytokines through STAT-6. Clin Immunol. 2008;126:332–7. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2007.11.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Howell MD, Kim BE, Gao P, Grant AV, Boguniewicz M, Debenedetto A, et al. Cytokine modulation of atopic dermatitis filaggrin skin expression. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120:150–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2007.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sawada E, Yoshida N, Sugiura A, Imokawa G. Th1 cytokines accentuate but Th2 cytokines attenuate ceramide production in the stratum corneum of human epidermal equivalents: an implication for the disrupted barrier mechanism in atopic dermatitis. J Dermatol Sci. 2012;68:25–35. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Yosipovitch G, Papoiu AD. What causes itch in atopic dermatitis? Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2008;8:306–11. doi: 10.1007/s11882-008-0049-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Dillon SR, Sprecher C, Hammond A, Bilsborough J, Rosenfeld-Franklin M, Presnell SR, et al. Interleukin 31, a cytokine produced by activated T cells, induces dermatitis in mice. Nat Immunol. 2004;5:752–60. doi: 10.1038/ni1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Kasraie S, Niebuhr M, Baumert K, Werfel T. Functional effects of interleukin 31 in human primary keratinocytes. Allergy. 2011;66:845–52. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02545.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Lee CH, Hong CH, Yu WT, Chuang HY, Huang SK, Chen GS, et al. Mechanistic correlations between two itch biomarkers, cytokine interleukin-31 and neuropeptide β-endorphin, via STAT3/calcium axis in atopic dermatitis. Br J Dermatol. 2012;167:794–803. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2012.11047.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]