Background: INF2 is not regulated by typical formin autoinhibition.

Results: INF2 is autoinhibited in cells and is constitutively active in biochemical actin polymerization assays containing only actin monomers but is inhibited by proteins that bind actin monomers.

Conclusion: INF2 can be activated by actin monomers.

Significance: A component of INF2 regulation might be the ability to sense free actin monomer levels.

Keywords: Actin, Cdc42, Endoplasmic Reticulum (ER), Formin, Rho

Abstract

INF2 is an unusual formin protein in that it accelerates both actin polymerization and depolymerization, the latter through an actin filament-severing activity. Similar to other formins, INF2 possesses a dimeric formin homology 2 (FH2) domain that binds filament barbed ends and is critical for polymerization and depolymerization activities. In addition, INF2 binds actin monomers through its diaphanous autoregulatory domain (DAD) that resembles a Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein homology 2 (WH2) sequence C-terminal to the FH2 that participates in both polymerization and depolymerization. INF2-DAD is also predicted to participate in an autoinhibitory interaction with the N-terminal diaphanous inhibitory domain (DID). In this work, we show that actin monomer binding to the DAD of INF2 competes with the DID/DAD interaction, thereby activating actin polymerization. INF2 is autoinhibited in cells because mutation of a key DID residue results in constitutive INF2 activity. In contrast, purified full-length INF2 is constitutively active in biochemical actin polymerization assays containing only INF2 and actin monomers. Addition of proteins that compete with INF2-DAD for actin binding (profilin or the WH2 from Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein) decrease full-length INF2 activity while not significantly decreasing activity of an INF2 construct lacking the DID sequence. Profilin-mediated INF2 inhibition is relieved by an anti-N-terminal antibody for INF2 that blocks the DID/DAD interaction. These results suggest that free actin monomers can serve as INF2 activators by competing with the DID/DAD interaction. We also find that, in contrast to past results, the DID-containing N terminus of INF2 does not directly bind the Rho GTPase Cdc42.

Introduction

Formin proteins are potent actin assembly factors that regulate a variety of actin-based structures in eukaryotic cells (1). A key functional domain of formins is the approximately 400-amino acid formin homology 2 (FH2) domain, an antiparallel donut-shaped dimer. Biochemically, the FH2 can accelerate actin nucleation significantly and, subsequently, regulates elongation by remaining processively bound to the fast-growing barbed end of the actin filament. The FH1 domain, N-terminally to the FH2, binds the actin monomer-binding protein profilin, accelerating the elongation rate of the FH2-bound barbed end (2, 3).

Many formins, termed diaphanous-related formins, are regulated by an autoinhibitory mechanism (4–6), with the most detailed evidence for this model coming from the mammalian formin mDia1. In mDia1, the N-terminal diaphanous inhibitory domain (DID)3 binds with submicromolar affinity to the diaphanous autoregulatory domain (DAD) (7–9), inhibiting FH2 domain activity by steric occlusion and DAD sequestration (10, 11). Activation of mDia1 occurs through GTP-RhoA binding to a region overlapping the DAD-interacting region of DID, competing with the DID/DAD interaction and freeing the FH2 domain (7–9, 12).

Recent evidence suggests that regions C-terminal to the FH2 participate in actin assembly by formins. The C termini of multiple formins, including mDia1 and FMNL3, strongly accelerate actin polymerization (13, 14), an effect that appears to be due to increased nucleation rate, not increased elongation. Similarly, a region immediately C-terminal to the FH2 of the formin INF2 also strongly affects its activity on actin (15, 16). INF2 is an unique formin in that it accelerates both actin polymerization and depolymerization, the latter dependent on a potent filament-severing activity that requires ATP hydrolysis and phosphate release from the filament (15). The DAD-containing region of INF2 both accelerates FH2-mediated polymerization and is required for severing/depolymerization.

These results are significant in view of the emerging cellular roles of INF2. INF2 exists as two distinct splice variants that have very different cellular localizations and functions. The prenylated INF2-CAAX variant binds tightly to the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) and mediates mitochondrial fission (17), whereas the INF2-non-CAAX variant is cytoplasmic and plays a role in Golgi organization (18). INF2 may play additional roles in vesicular trafficking, microtubule stabilization, and centrosome orientation (19–21). Mutations in the DID region of INF2 result in two human diseases, focal segmental glomerulosclerosis (22) and Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease (23).

Despite the similar C-terminal requirements for full activity, both the exact nature of the formin C-terminal effect and the C-terminal sequence involved are protein-specific for the three best characterized formins (INF2, mDia1, and FMNL3). The DAD of INF2 also binds an actin monomer with submicromolar affinity through an interaction similar to that of a WASp homology 2 (WH2) motif (Fig. 1 (15)). In contrast, amino acids C-terminal to the DAD of mDia1 play a role in its stimulatory effect on the FH2 domain, but core DAD residues do not appear important to this effect (13). Furthermore, the C terminus of mDia1 binds actin monomers weakly, with an estimated dissociation constant of > 50 μm (13, 14). FMNL3 represents a third variation, with a WH2-like sequence N-terminal to, but distinct from, its DAD. This WH2-like sequence binds actin monomers with low micromolar affinity, intermediate between INF2 and mDia1 C termini (14).

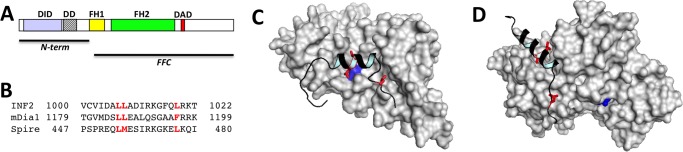

FIGURE 1.

INF2 domains and DAD interaction with DID or actin monomers. A, bar diagram showing INF2 domains. The N-terminal and FFC constructs used in this work are shown. B, alignments of INF2 DAD (human) with mDia1 DAD (mouse) and Spire WH2 domain 2 (Drosophila). Key hydrophobic residues mediating interaction with actin or DID are shown in red. C, model of INF2 DID/DAD interaction on the basis of the mouse mDia1 DID/DAD crystal structure (PDB code 2BAP). Gray, DID surface; black, DAD main chain. The position of the DID Ala-149 residue is shown in blue, illustrating why its mutation to D disrupts the DID/DAD interaction. Key interacting leucines in DAD are shown in red (also highlighted in B). D, model of INF2 DAD (black) bound to actin monomer (gray) on the basis of the Drosophila Spire WH2#2/actin crystal structure (PDB code 3MN5). Gray, actin surface; black, DAD main chain. Key interacting leucines in DAD are shown in red (also highlighted in B). ATP bound to actin is shown in blue.

One unresolved question concerns the relationship between actin interaction and regulation in the C-terminal region. This question is particularly acute for INF2 because actin- and DID-binding sequences overlap in the DAD (Fig. 1). Indeed, mutation of three leucine residues in the DAD disrupts both actin and DID binding (15, 24). These results suggest that actin monomers and DID may compete for DAD binding, with the result that actin monomers can relieve autoinhibition. In this work, we present evidence supporting this hypothesis.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

DNA Constructs

The human INF2 ORF clone (catalog no. SC313010) was obtained from OriGene Technologies, Inc. Fragments of the clone were amplified using the EXPAND PCR system (Roche) and subcloned into the eGFP-C1 vector (Clontech). Similarly, INF2-CAAX (amino acids 1–1249) and INF2-full-non-CAAX (amino acids 1–1240) were generated by PCR and cloned into eGFP-C1. Point mutations were made using QuikChange mutagenesis (Stratagene). For insect cell expression, INF2-full-non-CAAX (mouse) was PCR-amplified and cloned into pFastBac1 (Invitrogen). The mCherry-Sec61b was a gift from Jennifer Lippincott-Schwartz (NIGMS, National Institutes of Health).

Cellular Experiments

U2OS human osteosarcoma cells (a gift from Duane Compton, Geisel School of Medicine) were maintained in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium with 4.5 g/liter glucose, 584.0 mg/liter l-glutamine, 110.0 mg/liter sodium pyruvate, and 10% calf serum (Atlanta Biologicals) at 37 °C and 5% CO2. Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen) was used for all plasmid transfections according to the protocol of the manufacturer. 100 ng of each plasmid DNA was used for all transfections, and the cells were analyzed 16–18 h post-transfection. Cells were fixed with 4% formaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.4) for 15 min at room temperature. After washing with PBS, cells were permeabilized on ice with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS for 15 min. Cells were then washed with PBS prior to blocking with 2.5% calf serum in PBS for 1 h at room temperature. Actin was stained using 100 nm TRITC-phalloidin (Sigma). Images were captured using one of the following systems: Wave FX spinning disc confocal system (Quorum Technologies, on a Nikon Eclipse microscope) using the 491-nm laser and 525/20 filter for GFP, the 403-nm laser and 460/20 filter for DAPI, and the 561-nm laser and 593/40 filter for Texas red and the laser-scanning Nikon A1RSi confocal workstation with a PMT DU4 and Galvano scanner and 405-, 488-, 561-, and 639.5-nm lasers. Images were acquired using Metamorph and were processed using Nikon Elements and Adobe Photoshop CS.

Protein Expression and Purification

INF2-FH1FH2C (FFC, human CAAX variant, amino acids 469–1249) was expressed in Escherichia coli as a GST fusion protein following procedures used previously (25). After expression, extracts were passed over glutathione-Sepharose (GE Biosciences), cleaved with tobacco etch virus protease to elute INF2-FFC, and further purified by ion exchange chromatography on SourceQ. INF2-N terminus (human, amino acids 1–420) was expressed as a GST fusion in pGEX-KT, purified over glutathione-Sepharose, eluted with glutathione, and then gel-filtered over Superdex200 (GE Biosciences). Alternately, INF2-Nterm was cleaved with thrombin before gel filtration. INF2-Cterm (amino acids 941–1249) was expressed as a GST fusion protein and purified over glutathione-Sepharose and Superdex200. All INF2 proteins were stored at −80 °C in K50MEID (50 mm KCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 1 mm EGTA, 10 mm imidazole (pH 7.0), and 1 mm DTT). mDia1 N terminus (mouse, amino acids 1–548) was expressed and purified as described in Ref. 8. Rabbit skeletal muscle actin was purified from acetone powder (26) and labeled with pyrenyliodoacetamide (27). Both unlabeled and labeled actin were gel-filtered on Superdex 200 and stored in G buffer (2 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 0.5 mm DTT, 0.2 mm ATP, 0.1 mm CaCl2, and 0.01% sodium azide) at 4 °C. Human profilin I was expressed in bacteria and purified as described in Ref. 28 and stored in 2 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 0.5 mm EGTA, and 1 mm DTT. Cdc42 was expressed and purified using bacterial and insect cell systems as described previously (29) and stored in TDEM (10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.0), 0.5 mm DTT, 1 mm EGTA, and 1 mm MgCl2) containing 10 μm GDP.

Full-length INF2 was expressed in Sf9 cells using the Bac to Bac expression system (Invitrogen) following the instructions of the manufacturer. Cells were harvested for protein purification 2.5 days post-infection, washed three times in cold PBS, resuspended in EB (50 mm Hepes 7.6 (at 4 ºC), 300 mm NaCl, 1 mm MgCl2, 1 mm DTT, 2 μg/ml leupeptin, 10 μg/ml aprotinin, 1 μg/ml calpeptin, 1 μg/ml calpain inhibitor 1, 1 μg/ml pepstatin A, and 1 mm benzamidine) and lysed by Dounce. The high-speed supernatant was passed over Q-Sepharose followed by Source Q15, eluting from the latter using an NaCl gradient between 150 and 300 mm NaCl. Actin concentration was quantified by its extinction coefficient (25,974 m−1 cm−1 at 290 nm). Other protein concentrations were quantified by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad) and confirmed by Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE using known concentrations of actin as standards.

INF2-Cterm Labeling and Anisotropy

INF2-Cterm (12.5 μm) was mixed with tetramethylrhodamine succinimide (TMR) (250 μm, Molecular Probes) in 25 mm sodium phosphate (pH 7.0), 50 mm NaCl, 0.25 mm EDTA, and 0.125 mm DTT for 60 min at 23 °C. Then the reaction was terminated by addition of Tris-HCl (pH 8.0) to a final concentration of 100 mm. The reaction was gel-filtered on Superose12 (GE Biosciences) equilibrated in polymerization buffer. Final protein concentration was determined by Bradford assay (Bio-Rad) and TMR concentration using the extinction coefficient of 74,000 m−1 cm−1 at 555 nm. The calculated ratio of TMR:INF2-Cterm was 0.86.

Antibody Preparation

Rabbit polyclonal antibodies against the INF2 N terminus or mDia1 N terminus were produced through Covance Inc. Antibodies were affinity-purified using the GST fusion proteins covalently attached to Sulfo-link resin (Pierce) and eluted in 200 mm glycine-HCl (pH 2.5). Antibodies were dialyzed into PBS.

Actin Polymerization Assays

Unlabeled and pyrene-labeled actin were mixed in G buffer to produce a 5% pyrene-actin stock. This stock was converted to Mg2+ salt by 2 min of incubation at 23 °C in 1 mm EGTA/0.1 mm MgCl2 immediately prior to polymerization. Polymerization was induced by addition of 10× KMEI (500 mm KCl, 10 mm MgCl2, 10 mm EGTA, and 100 mm imidazole (pH 7.0)) to a concentration of 1×, with the remaining volume made up by G-Mg (G buffer containing 0.1 mm MgCl2 instead of CaCl2). Pyrene fluorescence (excitation 365 nm, emission 410 nm) was monitored in a 96-well fluorescence plate reader (Tecan Infinite M1000, Mannedorf, Switzerland). The time between mixing of final components and start of fluorimeter data collection was measured for each assay and ranged between 15 and 20 s.

GST Pull-down Assays

Purified GST fusions were mixed with glutathione-Sepharose 4B beads in assay buffer (1× KMEI + 0.5% thesit + 1 mm DTT) overnight at 4 °C, washed in assay buffer, and then the amount of bound GST fusion was quantified by Bradford assay. Cdc42 was charged with 5′-guanylyl imidodiphosphate (GMP-PNP) or GDP by mixing 10 mm Cdc42 with 1 mm nucleotide in 1× KMEI. To this solution, EDTA was added to 2 mm from a 500 mm stock, and the mixture was incubated for 10 min at 30 °C. An additional 2 mm MgCl2 was added from a 1 m stock, and the mixture was placed on ice. Binding reactions contained 9 mm GST fusion and 3 mm of the putative binding partner (Cdc42 or INF2-FFC) in assay buffer and were mixed for 30 min at 4 °C. After centrifugation (1800 × g for 2 min in a swinging bucket rotor), supernatants were removed, and pellets were washed briefly in assay buffer. Supernatants and pellets were analyzed by Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE.

RESULTS

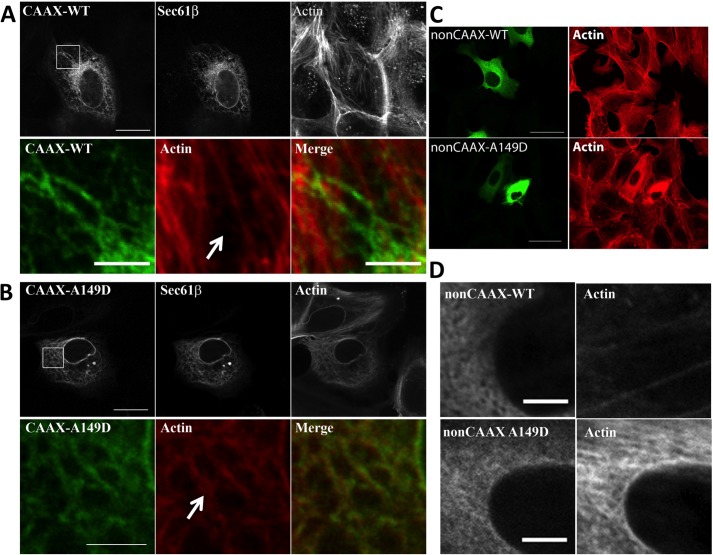

To test whether the DID/DAD interaction contributes to INF2 regulation in cells, we mutated a key DID residue for DAD binding in a plasmid expressing full-length GFP-INF2-CAAX and transfected this construct into U2OS cells. This mutation, alanine 149 to aspartate (A149D) is predicted to strongly compromise INF2 DID/DAD affinity on the basis of the effect of the analogous mutation (A256D) in the DID of mDia1 (7, 9), which adds both charge and bulk into the hydrophobic binding pocket. Our modeling studies suggest similar structures for INF2 and mDia1 DIDs (Fig. 1). As in our past findings (18, 24), wild-type INF2-CAAX associates with the ER but causes only a low level of actin polymerization on the ER surface, as judged by TRITC-phalloidin staining (Fig. 2A). In contrast, the A149D mutant causes a significant proportion of the phalloidin staining to shift from stress fibers to the ER surface (Fig. 2B). To confirm that the GFP-INF2-CAAX localization represents the ER, we used CFP-Sec61p as an ER marker and found that its staining overlapped with GFP (Fig. 2, A and B). Accumulation of actin on the ER occurs in over 90% of A149D cells examined while occurring in less than 10% of wild-type cells (> 100 cells examined).

FIGURE 2.

Disruption of the DID/DAD interaction causes constitutive actin polymerization by INF2 in cells. Shown is the effect of transfected GFP-INF2 constructs on actin organization in U2OS cells that were transfected with GFP-INF2 and the ER marker CFP-Sec61β (A and B) or GFP-INF2 alone (C and D) for 16–18 h and then fixed and stained with TRITC-phalloidin. All images were acquired with the same exposure times for actin and GFP and adjusted in the same manner. Enlarged images are single Z slices (0.2 μm) from confocal micrographs. A, INF2-CAAX WT showing ER localization but minimal actin filament accumulation on the ER (arrow). The lower panels denote the boxed region. Scale bars = 20 μm (upper panels) and 5 μm (lower panels). B, the INF2-CAAX A149D mutant showing ER localization and most of the cellular actin filament staining tracing the ER (compare the transfected cell to the non-transfected cell in the upper panels). Scale bars = 20 μm (upper panels) and 5 μm (lower panels). C, INF2-non-CAAX WT (upper panels) and A149D mutant (lower panels) showing normal actin filament staining for the WT but greatly increased actin filaments in A149D. Scale bars = 50 μm. D, Close-ups of the perinuclear regions of cells transfected with WT (upper panels) or A149D INF2-non-CAAX. Note the large increase in actin staining for the A149D mutant. Scale bars = 5 μm.

We extended these results by conducting a similar experiment on the INF2-non-CAAX isoform, which localizes to the cytosol with some enrichment in the perinuclear region around the Golgi (18). Wild-type INF2-non-CAAX causes no apparent change in the phalloidin staining pattern compared with non-transfected cells (Fig. 2C), whereas INF2-non-CAAX-A149D causes a marked increase in cytosolic phalloidin staining (Fig. 2D). Quantification of perinuclear phalloidin staining versus cellular GFP intensity shows that the A149D mutant, but not the wild type, causes increased filament accumulation versus the wild type at a range of transfection levels (not shown). These results suggest that the DID and DAD of INF2 participate in an autoinhibitory interaction, similar to other formins, such as mDia1.

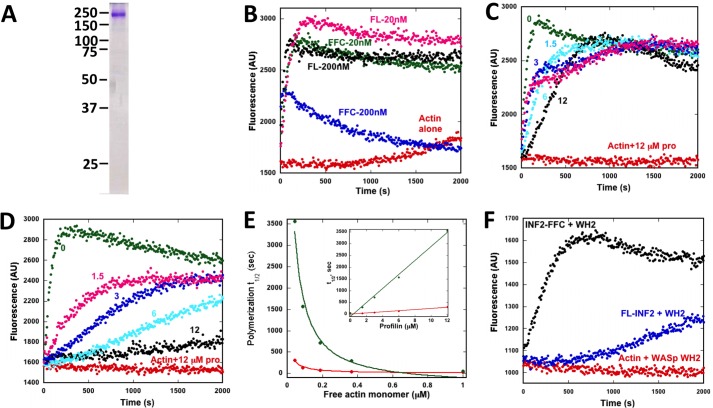

However, the results contradict our previous biochemical results showing that the DID-containing N terminus (INF2-NT) of INF2 does not inhibit actin polymerization acceleration by INF2-FFC (24). One possibility is that the trans-interaction of INF2-NT with INF2-FFC does not accurately recapitulate the situation in the full-length protein. To test this hypothesis, we expressed and purified full-length INF2 (non-CAAX) from an insect cell system (Fig. 3A) and tested its actin polymerization activity using a pyrene-actin assay. Full-length INF2 retains equivalent actin polymerization activity to INF2-FFC (Fig. 3B). Unlike INF2-FFC, however, full-length INF2 does not accelerate actin depolymerization (Fig. 3B). This result is also similar to the trans-assay, in which INF2-NT inhibits actin depolymerization by INF2-FFC (24). Thus, the cellular data suggesting DID/DAD-dependent INF2 autoinhibition of actin polymerization are in conflict with biochemical results showing no autoinhibition of polymerization but inhibition of depolymerization.

FIGURE 3.

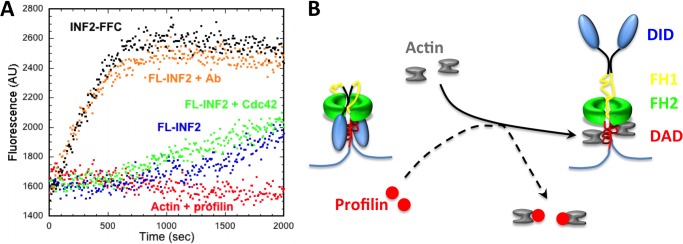

Free actin monomers activate full-length INF2. Shown are pyrene-actin assays containing 1 μm actin monomer (10% pyrene label). A, Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE of purified full-length INF2-non-CAAX used in these assays. Numbers represent molecular weight markers. B, effect of 20 or 200 nm INF2-FFC or full-length INF2 on actin polymerization in the absence of profilin. Note the rapid polymerization/depolymerization caused by 200 nm FFC but not by 200 nm full-length. AU, arbitrary units. C, effect of increasing profilin concentration (numbers indicate micromolar profilin) on 20 nm INF2-FFC polymerization activity. D, effect of increasing profilin concentration on 20 nm full-length INF2 polymerization activity. E, polymerization half-times (t½) for INF2-FFC and full-length INF2 as a function of profilin concentration (inset) or of calculated free actin monomer concentration (on the basis of a profilin:actin Kd of 0.5 μm (40)). F, effect of the WASp WH2 motif (48 μm) on FL-INF2 or INF2-FFC activity (20 nm INF2).

One possible explanation is that actin monomer binding to the DAD of INF2 competes with DID binding, relieving autoinhibition and activating polymerization. Indeed, INF2-DAD binds actin monomers and resembles an actin monomer-binding WH2 motif (15). To test this hypothesis, we conducted pyrene-actin polymerization assays using varying concentrations of profilin, which binds at an overlapping site on actin to WH2 motifs (30, 31). Increasing concentrations of profilin should progressively inhibit the polymerization activity of full-length INF2 if free actin monomers activate INF2 through DAD binding. As a control, we tested the effect of profilin on INF2-FFC polymerization activity and found a minimal inhibitory effect (Fig. 3C). In contrast, full-length INF2 polymerization activity is strongly inhibited by increasing profilin concentration (Fig. 3D). We quantified the polymerization activity of INF2 by measuring the half-time (t½) to full polymerization, with a larger t½ denoting lower polymerization activity. We plotted t½ versus free actin monomer concentration (meaning not bound to profilin) in addition to plotting against profilin concentration (Fig. 3E). These results show a concentration-dependent increase in INF2 activity with increasing free actin monomer concentration. To test this effect further, we used the WH2 motif from WASp to compete with the DAD of INF2 for actin monomer binding. Because WASp-WH2 binds actin monomers more weakly than profilin, a higher concentration is needed but produces a similar inhibitory effect on full-length INF2 (but not INF2-FFC) activity (Fig. 3F).

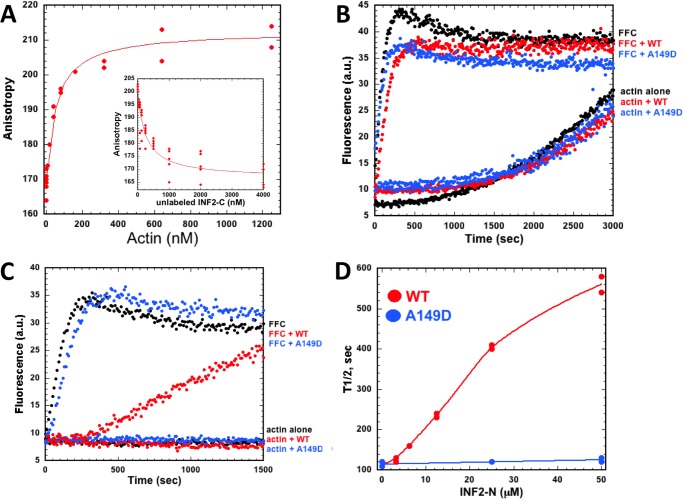

We have shown previously that the DAD-containing C terminus of mouse INF2 binds to actin monomers (15). To verify this interaction for the human protein, we labeled human INF2-Cterm with TMR and then conducted fluorescence anisotropy experiments in the presence of varying concentrations of latrunculin B (LatB)-stabilized actin monomers, similar to past studies. These assays show that TMR-INF2-C binds the actin monomer with a Kdapp of 0.12 μm (Fig. 4A). To test whether the TMR label contributes to the binding affinity, we conducted competition assays in which fixed concentrations of TMR-INF2-C and LatB-stabilized actin monomers are mixed with unlabeled INF2-C. In these experiments, increasing unlabeled INF2-C reduces the anisotropy of TMR-INF2-C, suggesting competitive binding with a Kdapp of 0.18 μm (Fig. 4A, inset). These experiments show that, similar to mouse INF2, the C terminus of human INF2 binds actin monomers.

FIGURE 4.

The N terminus of IFN2 inhibits actin polymerization by INF2-FFC only when free actin monomer concentration is low. A, fluorescence anisotropy assay for actin monomer binding by INF2-Cterm. TMR-labeled INF2-Cterm (5 nm) was mixed with varying concentrations of LatB-stabilized actin (1.5 moles LatB:1 mole actin), and anisotropy was recorded. Inset, competition assay in which 5 nm TMR-INF2-Cterm and 200 nm LatB/actin were mixed with varying concentrations of unlabeled INF2-C, and anisotropy was recorded. B and C, pyrene-actin polymerization assays (1 μm actin monomer, 10% pyrene labeled) using 20 nm INF2-FFC and 50 μm INF2-Nterm (wild-type or A149D mutant) in the absence of profilin (B) or in the presence of 12 μm profilin (C). a.u., arbitrary units. D, concentration dependence of INF2-Nterm (wild-type and A149D mutant) on INF2-FFC inhibition as measured by the half-time to full polymerization.

Our previous results showed that mouse INF2-Nterm was unable to inhibit mouse INF2-FFC when added in trans (15). We confirmed this result with the human proteins, testing 50 μm INF2-Nterm and finding no inhibition on 20 nm INF2-FFC (Fig. 4B). We next conducted these assays in the presence of 12 μm profilin, which allowed inhibition of the full-length protein. Under these conditions, INF2-Nterm inhibits INF2-FFC, whereas the A149D point mutation does not (Fig. 4C). We were unable to reach a saturating concentration of wild-type INF2-Nterm in these assays, testing up to 50 μm (Fig. 4D). These results suggest that the DID/DAD interaction of INF2 is low-affinity compared with that of mDia1 (4, 8). Indeed, fluorescence anisotropy assays using TMR-INF2-Cterm failed to show saturating binding at the highest testable concentrations of INF2-Nterm (not shown).

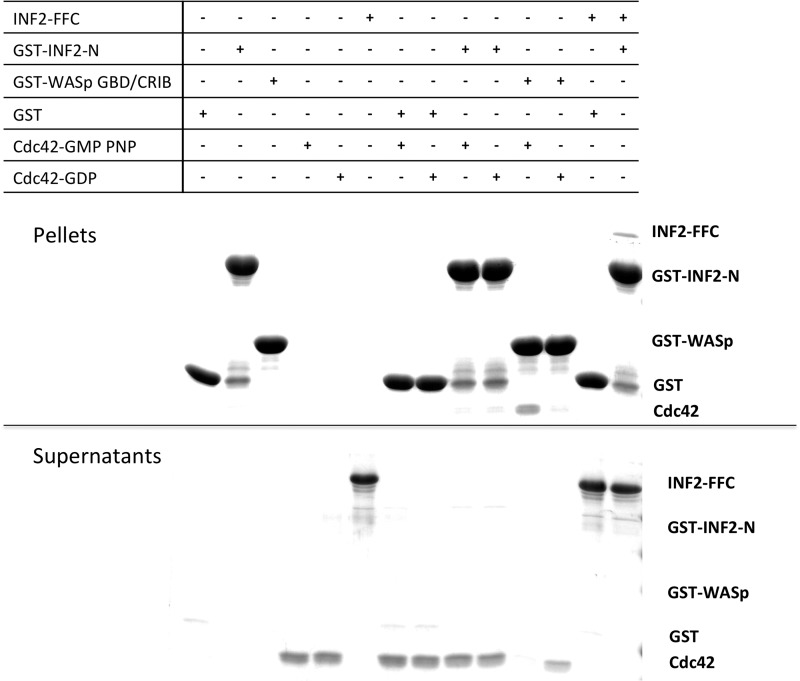

If actin monomers activate INF2 by competing with DID for DAD binding, the reverse scenario should also be true. Factors that compete with DAD for DID binding should activate INF2. This model is similar to the activation mechanism for mDia1 whereby GTP-bound RhoA binds to a region overlapping the DAD binding site (7–9, 12). Another Rho family GTPase, Cdc42, has been proposed to bind and activate INF2, on the basis of assays using cell extracts as the source of Cdc42 (20, 21). We tested the ability of GTP-charged Cdc42 to directly bind the DID-containing N terminus of INF2 using GST pull-down assays similar to those used in the previous work but in which both Cdc42 and INF2 N terminus were present as purified proteins. These assays show no evidence for direct binding between INF2 N terminus and Cdc42, whereas the positive control reactions (Cdc42 binding to the WASp CRIB (Cdc42/Rac interactive binding) domain and INF2 N terminus binding to INF2-FFC) do display binding (Fig. 5). The Cdc42 used in this experiment was produced in insect cells and purified from the membrane fraction. Thus, it is likely to contain the C-terminal prenyl modification. Use of bacterially expressed, non-prenylated Cdc42 produces similar results (not shown).

FIGURE 5.

The N terminus of INF2 does not display a high-affinity direct interaction with Cdc42. Cdc42 was precharged with either GMP-PNP or GDP and then mixed (3 μm) with 9 μm of GST-fusion of the N terminus of IFN2 (amino acids 1–420) bound to glutathione-Sepharose beads in actin polymerization buffer. Beads were isolated by centrifugation, and supernatant and pellet were analyzed by Coomassie-stained SDS-PAGE (equal volumes loaded). Positive controls were the CRIB of WASp for verification of Cdc42 binding ability and INF2-FFC for verification of INF2-N binding ability.

We also tested the effect of Cdc42 on full-length INF2 in actin polymerization assays containing profilin. A 50-fold molar excess of GMP-PNP-charged Cdc42 over INF2 fails to change the polymerization time course, suggesting that Cdc42 does not disrupt the autoinhibitory DID/DAD interaction (Fig. 6A). Similarly, use of GDP-charged Cdc42 has no effect on INF2 activity (not shown). In the absence of a physiological INF2 activator, we used a polyclonal antibody against the N terminus if INF2 (anti-INF2-NT) as a means of disrupting the DID/DAD interaction. Full-length INF2-non-CAAX is premixed with the antibody, followed by its addition into pyrene-actin polymerization assays containing profilin. The anti-INF2-NT antibody activates INF2 activity (Fig. 6A), whereas a nonspecific antibody does not (not shown). These results suggest that antibody binding to DID disrupts the DID/DAD interaction, activating actin polymerization.

FIGURE 6.

Competition with DID/DAD binding activates full-length INF2. A, pyrene-actin assays containing 1 μm actin monomer (10% pyrene), 12 μm profilin, and 20 nm full-length INF2. After preincubation with anti-INF2-Nterm antibody (0.1 mg/ml, 650 nm), INF2 is active. In contrast, GMP-PNP-charged Cdc42 (1 μm, bacterially expressed) has no effect on INF2 activity. AU, arbitrary units. B, model for actin monomer activation of INF2. In the absence of actin, INF2 is autoinhibited through the DID/DAD interaction. Actin monomer binding to DAD competes with DID binding, freeing the FH2 domain. Profilin sequesters actin monomers from DAD binding, preventing activation.

DISCUSSION

We show here that INF2 is autoinhibited but that free actin monomers can compete with the DID/DAD interaction, activating actin polymerization (Fig. 6B). It is unclear whether this mechanism is generally applicable, although actin monomer binding to regions surrounding the DAD occurs for several formins (13–15). mDia1 appears to be autoinhibited even in the presence of free actin monomers (4, 32), which might be due to the extremely low affinity of its DAD region for actin or to the fact that the actin binding site does not overlap the DID binding site (13, 14). The C-terminal region of FMNL3 binds actin monomers with micromolar affinity, but the region responsible for this binding is distinct from the canonical DAD region. Thus, it might not be predicted to play a significant role in regulation (14, 33). Structural information on the autoinhibitory interaction of FMNL formins would be extremely interesting in this respect.

Could actin monomer binding represent a physiological activation mechanism for INF2? On the basis of the cytoplasmic concentrations of actin, profilin, and thymosin β4 (a sequestering protein whose actin monomer binding site overlaps that of INF2-DAD), the concentration of free actin monomer is estimated to be in the micromolar range in mammalian cells (34, 35). Fluctuations in cellular actin polymerization, increasing or decreasing the free monomer pool, could conceivably increase or decrease INF2 activity, similar (but in an opposite manner) to models of serum response factor-negative regulation by actin monomer levels (36). Because INF2 plays a role in mitochondrial dynamics (17) and because mitochondria play central roles in cellular homeostasis (37, 38), such a mechanism could be a means for monitoring cellular state. Interestingly, the activity of mDia1 is also increased by increases in actin monomer concentration (35, 39), but the mechanism of this effect appears different from that of INF2 because this effect does not require DID or DAD regions.

Our findings suggesting no high affinity direct interaction between the N terminus of INF2 and Cdc42 are at odds with previous results (20, 21). The differences in the source of Cdc42 may, however, explain the conflicting results. In the previous studies, Cdc42 was from cell extracts, whereas we used purified Cdc42 (both prenylated and non-prenylated). The source of INF2 was very similar in both studies, being a bacterially expressed DID-containing construct fused to the C terminus of glutathione S-transferase (INF2 amino acids 1–340 in Refs. 20, 21 and 1–420 in this study). Therefore, it is possible that Cdc42 and INF2 interact through additional proteins present in cellular extracts and that these additional proteins might serve as stabilizing factors for the DID/DAD interaction.

Acknowledgments

We thank Matthias Geyer for suggesting the idea of actin monomer-mediated activation. We also thank Sonja Kuehn (Geyer laboratory) for the models in Fig. 1 and Monica Stermon for many additions to the process.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 GM069818 (to H. N. H.). This work was also supported by a National Science Foundation predoctoral fellowship (to A. L. H.).

- DID

- Diaphanous inhibitory domain

- DAD

- diaphanous autoregulatory domain

- ER

- endoplasmic reticulum

- TRITC

- tetramethylrhodamine isothiocyanate

- FFC

- FH1FH2C

- TMR

- tetramethylrhodamine-succinimide

- AA

- aliphatic amino acid

- NT

- N terminus

- WASp

- Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein.

REFERENCES

- 1. Campellone K. G., Welch M. D. (2010) A nucleator arms race. Cellular control of actin assembly. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 11, 237–251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Goode B. L., Eck M. J. (2007) Mechanism and function of formins in control of actin assembly. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 76, 593–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Paul A. S., Pollard T. D. (2009) Review of the mechanism of processive actin filament elongation by formins. Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 66, 606–617 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Li F., Higgs H. N. (2003) The mouse formin mDia1 is a potent actin nucleation factor regulated by autoinhibition. Curr. Biol. 13, 1335–1340 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schulte A., Stolp B., Schönichen A., Pylypenko O., Rak A., Fackler O. T., Geyer M. (2008) The human formin FHOD1 contains a bipartite structure of FH3 and GTPase-binding domains required for activation. Structure 16, 1313–1323 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Wallar B. J., Stropich B. N., Schoenherr J. A., Holman H. A., Kitchen S. M., Alberts A. S. (2006) The basic region of the diaphanous-autoregulatory domain (DAD) is required for autoregulatory interactions with the diaphanous-related formin inhibitory domain. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 4300–4307 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lammers M., Rose R., Scrima A., Wittinghofer A. (2005) The regulation of mDia1 by autoinhibition and its release by Rho*GTP. EMBO J. 24, 4176–4187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Li F., Higgs H. N. (2005) Dissecting requirements for auto-inhibition of actin nucleation by the formin, mDia1. J. Biol. Chem. 280, 6986–6992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Otomo T., Otomo C., Tomchick D. R., Machius M., Rosen M. K. (2005) Structural basis of Rho GTPase-mediated activation of the formin mDia1. Mol. Cell 18, 273–281 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Nezami A., Poy F., Toms A., Zheng W., Eck M. J. (2010) Crystal structure of a complex between amino and carboxy terminal fragments of mDia1. Insights into autoinhibition of diaphanous-related formins. PloS ONE 5, e12992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Otomo T., Tomchick D. R., Otomo C., Machius M., Rosen M. K. (2010) Crystal structure of the Formin mDia1 in autoinhibited conformation. PloS ONE 5, e12892. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Rose R., Weyand M., Lammers M., Ishizaki T., Ahmadian M. R., Wittinghofer A. (2005) Structural and mechanistic insights into the interaction between Rho and mammalian Dia. Nature 435, 513–518 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gould C. J., Maiti S., Michelot A., Graziano B. R., Blanchoin L., Goode B. L. (2011) The formin DAD domain plays dual roles in autoinhibition and actin nucleation. Curr. Biol. 21, 384–390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Heimsath E. G., Jr., Higgs H. N. (2012) The C terminus of formin FMNL3 accelerates actin polymerization and contains a WH2 domain-like sequence that binds both monomers and filament barbed ends. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 3087–3098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Chhabra E. S., Higgs H. N. (2006) INF2 is a WH2 motif-containing formin that severs actin filaments and accelerates both polymerization and depolymerization. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 26754–26767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Ramabhadran V., Gurel P. S., Higgs H. N. (2012) Mutations to the formin homology 2 domain of INF2 Protein have unexpected effects on actin polymerization and severing. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 34234–34245 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Korobova F., Ramabhadran V., Higgs H. N. (2013) An actin-dependent step in mitochondrial fission mediated by the ER-associated formin INF2. Science 339, 464–467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Ramabhadran V., Korobova F., Rahme G. J., Higgs H. N. (2011) Splice variant-specific cellular function of the formin INF2 in maintenance of Golgi architecture. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 4822–4833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Andrés-Delgado L., Antón O. M., Bartolini F., Ruiz-Sáenz A., Correas I., Gundersen G. G., Alonso M. A. (2012) INF2 promotes the formation of detyrosinated microtubules necessary for centrosome reorientation in T cells. J. Cell Biol. 198, 1025–1037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Andrés-Delgado L., Antón O. M., Madrid R., Byrne J. A., Alonso M. A. (2010) Formin INF2 regulates MAL-mediated transport of Lck to the plasma membrane of human T lymphocytes. Blood 116, 5919–5929 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Madrid R., Aranda J. F., Rodríguez-Fraticelli A. E., Ventimiglia L., Andrés-Delgado L., Shehata M., Fanayan S., Shahheydari H., Gómez S., Jiménez A., Martín-Belmonte F., Byrne J. A., Alonso M. A. (2010) The formin INF2 regulates basolateral-to-apical transcytosis and lumen formation in association with Cdc42 and MAL2. Dev. Cell 18, 814–827 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Brown E. J., Schlöndorff J. S., Becker D. J., Tsukaguchi H., Tonna S. J., Uscinski A. L., Higgs H. N., Henderson J. M., Pollak M. R. (2010) Mutations in the formin gene INF2 cause focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. Nat. Genet. 42, 72–76 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Boyer O., Nevo F., Plaisier E., Funalot B., Gribouval O., Benoit G., Cong E. H., Arrondel C., Tête M. J., Montjean R., Richard L., Karras A., Pouteil-Noble C., Balafrej L., Bonnardeaux A., Canaud G., Charasse C., Dantal J., Deschenes G., Deteix P., Dubourg O., Petiot P., Pouthier D., Leguern E., Guiochon-Mantel A., Broutin I., Gubler M. C., Saunier S., Ronco P., Vallat J. M., Alonso M. A., Antignac C., Mollet G. (2011) INF2 mutations in Charcot-Marie-Tooth disease with glomerulopathy. N. Engl. J. Med. 365, 2377–2388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chhabra E. S., Ramabhadran V., Gerber S. A., Higgs H. N. (2009) INF2 is an endoplasmic reticulum-associated formin protein. J. Cell Sci. 122, 1430–1440 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gaillard J., Ramabhadran V., Neumanne E., Gurel P., Blanchoin L., Vantard M., Higgs H. N. (2011) Differential interactions of the formins INF2, mDia1, and mDia2 with microtubules. Mol. Biol. Cell 22, 4575–4587 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Spudich J. A., Watt S. (1971) The regulation of rabbit skeletal muscle contraction. I. Biochemical studies of the interaction of the tropomyosin-troponin complex with actin and the proteolytic fragments of myosin. J. Biol. Chem. 246, 4866–4871 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. MacLean-Fletcher S., Pollard T. D. (1980) Mechanisms of action of cytochalasin B on actin. Cell 20, 329–341 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Harris E. S., Li F., Higgs H. N. (2004) The mouse formin, FRLa, slows actin filament barbed end elongation, competes with capping protein, accelerates polymerization from monomers, and severs filaments. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 20076–20087 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Higgs H. N., Pollard T. D. (2000) Activation by Cdc42 and PIP(2) of Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASp) stimulates actin nucleation by Arp2/3 complex. J. Cell Biol. 150, 1311–1320 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chereau D., Kerff F., Graceffa P., Grabarek Z., Langsetmo K., Dominguez R. (2005) Actin-bound structures of Wiskott-Aldrich syndrome protein (WASP)-homology domain 2 and the implications for filament assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 16644–16649 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Husson C., Cantrelle F. X., Roblin P., Didry D., Le K. H., Perez J., Guittet E., Van Heijenoort C., Renault L., Carlier M. F. (2010) Multifunctionality of the β-thymosin/WH2 module. G-actin sequestration, actin filament growth, nucleation, and severing. Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 1194, 44–52 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Maiti S., Michelot A., Gould C., Blanchoin L., Sokolova O., Goode B. L. (2012) Structure and activity of full-length formin mDia1. Cytoskeleton 69, 393–405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Vaillant D. C., Copeland S. J., Davis C., Thurston S. F., Abdennur N., Copeland J. W. (2008) Interaction of the N- and C-terminal auto-regulatory domains of FRL2 does not inhibit FRL2 activity. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 33750–33762 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Pollard T. D., Blanchoin L., Mullins R. D. (2000) Molecular mechanisms controlling actin filament dynamics in nonmuscle cells. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 29, 545–576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Higashida C., Kiuchi T., Akiba Y., Mizuno H., Maruoka M., Narumiya S., Mizuno K., Watanabe N. (2013) F- and G-actin homeostasis regulates mechanosensitive actin nucleation by formins. Nat. Cell Biol. 15, 395–405 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Posern G., Treisman R. (2006) Actin' together. Serum response factor, its cofactors and the link to signal transduction. Trends Cell Biol. 16, 588–596 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Martinou J. C., Youle R. J. (2011) Mitochondria in apoptosis. Bcl-2 family members and mitochondrial dynamics. Dev. Cell 21, 92–101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Youle R. J., van der Bliek A. M. (2012) Mitochondrial fission, fusion, and stress. Science 337, 1062–1065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Higashida C., Suetsugu S., Tsuji T., Monypenny J., Narumiya S., Watanabe N. (2008) G-actin regulates rapid induction of actin nucleation by mDia1 to restore cellular actin polymers. J. Cell Sci. 121, 3403–3412 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Pantaloni D., Carlier M. F. (1993) How profilin promotes actin filament assembly in the presence of thymosin β 4. Cell 75, 1007–1014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]