Abstract

Ammonia serves as the source of energy and reductant and as a signaling molecule that regulates gene expression in obligate ammonia-oxidizing chemolithotrophic microorganisms. The gammaproteobacterium, Nitrosococcus oceani, was the first obligate ammonia-oxidizer isolated from seawater and is one of the model systems for ammonia chemolithotrophy. We compared global transcriptional responses to ammonium and the catabolic intermediate, hydroxylamine, in ammonium-starved and non-starved cultures of N. oceani to discriminate transcriptional effects of ammonium from a change in overall energy and redox status upon catabolite availability. The most highly expressed genes from ammonium- or hydroxylamine-treated relative to starved cells are implicated in catabolic electron flow, carbon fixation, nitrogen assimilation, ribosome structure and stress tolerance. Catabolic inventory-encoding genes, including electron flow-terminating Complexes IV, FoF1 ATPase, transporters, and transcriptional regulators were among the most highly expressed genes in cells exposed only to ammonium relative to starved cells, although the differences compared to steady-state transcript levels were less pronounced. Reduction in steady-state mRNA levels from hydroxylamine-treated relative to starved-cells were less than five-fold. In contrast, several transcripts from ammonium-treated relative to starved cells were significantly less abundant including those for forward Complex I and a gene cluster of cytochrome c encoding proteins. Identified uneven steady-state transcript levels of co-expressed clustered genes support previously reported differential regulation at the levels of transcription and transcript stability. Our results differentiated between rapid regulation of core genes upon a change in cellular redox status vs. those responsive to ammonium as a signaling molecule in N. oceani, both confirming and extending our knowledge of metabolic modules involved in ammonia chemolithotrophy.

Keywords: Nitrosococcus, ammonia-oxidizing bacteria, ammonium, hydroxylamine, redox, signaling, global gene expression, microarray

Introduction

Obligate ammonia-oxidizing chemolithotrophic bacteria (AOB) facilitate key transformations in the global nitrogen cycle that interconnect nitrification, denitrification and ammonification (Klotz and Stein, 2011; Stein and Klotz, 2011; Simon and Klotz, 2013). When facilitated by AOB, all of these processes take place under oxic conditions because the first (mono-oxygenation of ammonia) and last (disposal of electrons) steps of catabolic electron flow require free molecular oxygen. AOB obtain all of their energy and reductant by catabolic oxidation of ammonia to nitrite, the first in the two-step nitrification process historically referred to as nitritation. Thus, AOB consume ammonia and oxygen for both maintenance of proton-motive force and growth via autotrophic chemosynthesis (Arp et al., 2002).

Ammonia oxidation is facilitated by two dedicated enzyme complexes that were once considered unique to AOB (Arp et al., 2002): ammonia monooxygenase (AMO, amoCAB, EC:1.14.99.39) and hydroxylamine dehydrogenase (HAO, haoA, EC:1.7.2.6). However, in recent times both AMO and HAO complexes have been identified in many diverse genome backgrounds (Klotz and Stein, 2008; Klotz et al., 2008; Sayavedra-Soto et al., 2011; Tavormina et al., 2011, 2013; Coleman et al., 2012; Hanson et al., 2013; Simon and Klotz, 2013). When expressed together in non-chemolithotrophs, such as methane-oxidizing bacteria (MOB; including Proteobacteria and Verrucomicrobia), these two protein complexes facilitate nitritation; however, the electrons extractable from hydroxylamine cannot be used to support growth via chemolithotrophic catabolism (Klotz and Stein, 2011; Stein and Klotz, 2011). Gene expression studies demonstrated that the haoA-associated gene haoB, adjacent to haoA and formerly known as orf2 (Bergmann et al., 2005), is co-expressed with haoA in the genomes of nitritating gammaproteobacterial AOB and MOB (Poret-Peterson et al., 2008; Campbell et al., 2011b). However, in order to utilize the electrons extracted from hydroxylamine during nitritation, AOB but not nitritating MOB employ the cytochrome c protein, cM552 (cycB) as a cognizant quinone reductase (Elmore et al., 2007; Kim et al., 2008) that either directly interacts with HAO or obtains electrons indirectly via cytochrome c554 (cycA) (Hooper et al., 2005; Klotz et al., 2008; Kern et al., 2011; Simon and Klotz, 2013). Earlier results indicated that the haoA and cycAB genes are under control of different promoters in N. europaea (Sayavedra-Soto et al., 1994; Arp et al., 2002; Hommes et al., 2002), however, gammaproteobacterial AOB such as N. oceani appear to produce distinct haoAB, cycAB and haoAB-cycAB transcripts indicating complex regulation similar to what was reported for the regulation of genes in the amo gene cluster (El Sheikh and Klotz, 2008; El Sheikh et al., 2008). Cytochrome cM552 belongs to a large superfamily of membrane-associated cytochrome c proteins (NapC/NrfH) that exchange electrons with the quinone/quinol pool (Bergmann et al., 2005; Simon and Klotz, 2013). Generally in bacterial genomes, the cycB gene encoding cM552 is clustered with other genes encoding catalytic periplasmic proteins that facilitate reduction of nitrogen oxides such as nitrate reductase (nap), nitrite reductase (nrf), and/or homologues of cytochrome c554 that function as nitric oxide reductases (Upadhyay et al., 2006; Klotz and Stein, 2011; Simon and Klotz, 2013).

Although the ever-increasing number of sequenced microbial genomes has revealed that amoCAB, haoAB, and cycAB genes are not unique to AOB (Arp et al., 2007), it appears that ammonia-dependent chemolithotrophy requires the presence and co-expression of all of these gene clusters (Klotz and Stein, 2011). So far, only the gene encoding the small red-copper protein nitrosocyanin, ncyA, (Arciero et al., 2002; Basumallick et al., 2005) has been identified in the genomes of all AOB with the exception of the oligotrophic Nitrosomonas sp. Is79 strain (Bollmann et al., 2012). The ncyA gene is conspicuously absent from other microbes including non-chemolithotrophic nitritating bacteria like the MOB (Campbell et al., 2011b; Klotz and Stein, 2011) and chemolitotrophic nitritating Thaumarchaeota (Walker et al., 2010). As AOB have two nitritation-dependent pathways that result in production of nitric and nitrous oxides, one starting with hydroxylamine oxidation and the other with nitrite reduction, this activity represents a significant drain to the redox status of the bacteria (Stein, 2011). Therefore, electron flow into and out of the quinone pool needs to be tightly regulated, perhaps by employing the product of the ncyA gene as a redox sensitive switch that directs electrons extracted by HAO to different acceptor proteins. However, this hypothesis remains to be tested.

To date, there is no clear conceptual understanding of the regulation of the amoCAB, haoAB, cycAB, and ncyA genes by cellular redox status and/or by general signaling molecules like ammonium (Sayavedra-Soto et al., 1996; Stein et al., 1997; Bollmann et al., 2005; Wei et al., 2006) or nitrogen oxides (Cho et al., 2006; Beyer et al., 2009; Cua and Stein, 2011; Kartal et al., 2012) and evidence of differential regulation of these gene sets in different genomic backgrounds has increased with every study. For instance, some studies of Nitrosomonas europaea ATCC 19718 report increased transcription of amoCAB genes and protein synthesis upon exposure to ammonium (Hyman and Arp, 1995; Sayavedra-Soto et al., 1996; Stein et al., 1997), whereas another study comparing expression levels between ammonium-starved and growing cells showed unvaried amoCAB transcript levels (Wei et al., 2006).

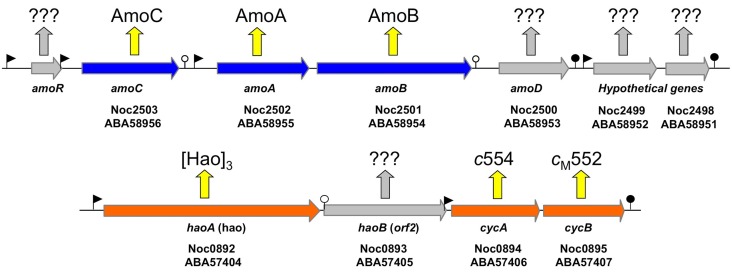

According to the current literature, the gammaproteobacterial genus Nitrosococcus is exclusively represented by marine and high salt-tolerant AOB (O'Mullan and Ward, 2005; Campbell et al., 2011a). In contrast to genomes of betaproteobacterial AOB that encode multiple, nearly identical copies of amoCAB and haoAB-cycAB gene clusters, Nitrosococcus genomes encode only one copy of each (Klotz et al., 2006; Arp et al., 2007; Campbell et al., 2011a; Klotz and Stein, 2011). The ncyA gene exists as a single copy in all AOB genomes (Klotz and Stein, 2011). In contrast, the complement of quinol-oxidizing electron flow inventory encoded in the genomes of nitrosococci is more diverse than that encoded in betaproteobacterial AOB genomes (Klotz and Stein, 2011). Thus, Nitrosococcus is an ideal model for discriminating differences between signaling- and energy-mediated expression of genes encoding essential inventory for catabolism and chemosynthesis. Thus, far, it has been shown that ammonium induces expression of the amoRCABD gene cluster encoding the AMO complex (Figure 1), whereby the individual overlapping operons in this cluster exhibited different patterns of regulation and expression (El Sheikh and Klotz, 2008; El Sheikh et al., 2008).

Figure 1.

Map of the amo gene cluster based on the genome sequence of N. oceani ATCC 19707. Filled arrows represent open reading frames. The promoters and transcriptional terminators are represented by flags and stem loops, respectively. Week terminators are indicated by an open circle. The amoR gene (not annotated in the genome and thus not represented on the array) is unique to Nitrosococcus oceani (strain ATTC 19707, AFC27, AFC132, and C-27) and Noc2499 and Noc2498 are hypothetical genes conserved in the genome sequenced strains of all three species in the genus Nitrosococcus (N. oceani, N. watsonii, and N. halophilus). Identified and hypothetical expression products are given by respective protein annotation or question marks, respectively.

In the present study, we used a Nimblegen-platform quadroplex microarray to investigate the differences between ammonium- and hydroxylamine-induced transcriptomes of N. oceani after denial of ammonia as an energy source. The premise for the experimental design was that genes similarly regulated between the ammonium and hydroxylamine treatments would be considered as “energy/redox status-regulated,” whereas genes more highly expressed under the ammonium compared to the hydroxylamine treatment would be considered as “ammonium-regulated.” The results allowed us to discriminate inventory that responds strongly and rapidly to a change in cellular redox status from exclusive members of the ammonia stimulon. The global transcriptional responses of N. oceani were compared to other AOB to better understand and define the core function and regulation of obligate ammonia-oxidizing chemolithotrophs.

Materials and methods

Bacterial growth and experimental treatments

Nitrosococcus oceani type-strain ATCC 19707 was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection and maintained at a temperature of 30°C in the dark without shaking on marine mineral salts medium as described previously (Graham et al., 2011). To attain sufficient biomass, multiple cultures were grown in 0.6- and 1-L batches of medium in 2- and 4-L Erlenmeyer flasks, respectively, and titrated to pH 8.0 daily with K2CO3. Cells were grown to late exponential growth phase as determined by NO−2 concentration, harvested by centrifugation (8000 × g, 15 min at 4°C), washed twice with NH3-free growth medium, and resuspended into 800 mL fresh NH3-free growth medium containing 5 mM HEPES. The resuspended cells were divided into four 200 mL aliquots for the following experimental treatments: (1) NH+4-Starved: Cells were denied energy and reductant by omitting (NH4)2SO4 from the growth medium for 24 h. (2) NH+4-Induced: Induction of gene expression by ammonium was investigated by exposing ammonium-starved cells (20 h) to 5 mM (NH4)2SO4 for 4 h. (3) Control: The control treatment was comprised of cells incubated in growth medium with 5 mM (NH4)2SO4 for 24 h. (4) NH2OH - Induced: Induction of gene expression by exposure to hydroxylamine was investigated by exposing ammonium-starved cells (23.5 h) to 0.2 mM NH2OH for 30 min. Biomass was collected by centrifugation following the specified exposure times and used immediately for RNA extraction.

RNA extraction

RNA was extracted with the FastRNA Pro Blue kit (Qbiogene, Irvine, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA pellets were resuspended in 100 mL of nuclease-free 0.1 mM EDTA (Ambion, Austin, TX, USA). Resuspended RNA was checked for integrity by visualization of ribosomal bands on an Ethidium bromide-stained agarose gel and quantified by absorbance at 260 nm on a spectrophotometer (Beckman DU 640, Fullerton, CA, USA). Each extraction yielded 15–30 μg total RNA. Intact RNA samples were treated with RQ1 RNase-free DNase (Promega, Madison, WI, USA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations, ethanol-precipitated, and resuspended in 20 mL of 0.1 mM EDTA and re-checked for degradation. A portion of the RNA was used in cDNA synthesis and the remainder was stored at −20°C. RNA was converted to first-strand cDNA using 200 ng of random nonamer primer with Superscript III (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) reverse transcriptase according to the manufacturer's instructions at an extension temperature of 50°C for 60 min. A portion of the first-strand cDNA was used in second-strand cDNA synthesis according to the manufacturer's instructions. The second-strand cDNA was shipped to NimbleGen Systems (Reykjavik, Iceland) for processing, labeling and microarray hybridization.

Array design, hybridization and analysis

The genome sequence from N. oceani (GenBank chromosome accession no. CP000127) was used by NimbleGen for microarray design and manufacture. The NimbleGen 4 × 72 K multiplex microarray slide contained 72,000 probe sets per array and four arrays per slide. Four replicates of the genome were included per array and six 60-mer probes represented each open reading frame (ORF) in the genome (the finished N. oceani genome is annotated to have 3017 ORFs). A quality control check (hybridization) was performed for each array, which contained on-chip control oligonucleotides. Double-stranded cDNA was random-prime labeled with Cy3-nonamers and hybridized to the microarrays. The microarrays were washed, dried, and scanned at 5 μ m resolution using a GenePix 4000B microarray scanner (Molecular Devices, Sunnyvale, CA). Data were extracted from scanned images using NimbleScan software (NimbleGen).

Microarray data analysis

Investigation of reproducible differences between treatments was performed using the CLC Genomics Workbench software package. Data were processed using quantile normalization and background correction was performed using the robust multi-array average (RMA) method. Data were visualized with scatter plots to examine the distribution of hybridizing cDNAs to Nitrosococcus probes (equivalent to NGS reads). Intensities were adjusted to have the same interquartile range. A linear model fit was determined for each gene using the CLC Genomics Workbench.

Expression ratios were calculated from the averages of four independent microarray hybridizations (i.e., a total of 16 spots averaged per gene, per treatment) and presented as: (1) Induction of transcripts responsive to ammonium (NH+4-Induced/NH+4-Starved); (2) Induction of transcripts responsive to NH2OH (NH2OH-Induced/NH+4-Starved); (3) Repression or degradation of transcripts from denial of ammonium as an energy source (NH+4-Starved/Control); and (4) Transcripts responsive to ammonium in non-starved cells (NH+4-Induced/Control). Hybridization results, ratios, and standard deviations from replicate microarray hybridizations are provided in Supplemental Table 1.

Results

Gene expression ratios between energy-induced vs. starved cells

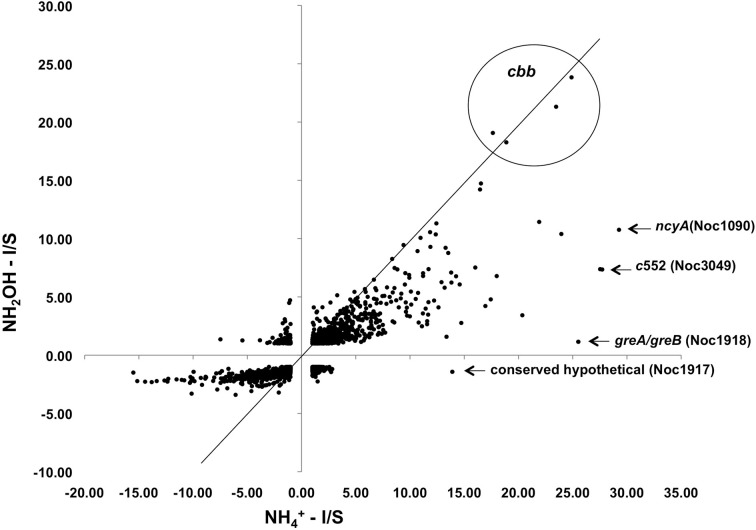

Exposure of N. oceani cells to either ammonium or hydroxylamine as an energy source allowed examination of global gene expression as the result of a change in cellular redox status. Steady-state mRNA levels varied from +30 to −16-fold when provided with ammonium or hydroxylamine relative to cells deprived of energy (Figure 2). Responses to ammonium resulted in greater variation across the genome when compared to responses to hydroxylamine in genes that were under-expressed relative to starved control cells, however, variation in upregulated genes was similar between the two treatments (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Expression ratios for genes across the N. oceani genome (chromosome and plasmid) for hydroxylamine-induced versus ammonium-induced cells relative to a starved-cell control.

Examination of individual genes and gene clusters affected by ammonium or hydroxylamine exposure showed the greatest response in modules for primary and secondary electron flow (Table 1) and carbon fixation (Figure 2; Table 2). It was expected that the primary inventory for chemolithotrophic ammonia oxidation (amoCAB, haoAB, cycAB, and ncyA), would be highly induced upon exposure to an energy-generating substrate, and particularly to ammonium. However, the steady-state levels of transcripts from ammonia monooxygenase (amoCAB, Noc2503, 2502, 2501) and hydroxylamine dehydrogenase (haoA, Noc0892) structural genes were not significantly changed, whereas the transcript levels of other genes in these two clusters (Noc2500, 2499; Noc0893, Noc0895) were significantly increased in response to ammonium or hydroxylamine and decreased in ammonium-starved relative to control cells (Figure 1; Table 1). Similarly, while levels of the cycA (Noc0894) transcript were not elevated, cycB (Noc0895) transcript levels were higher after exposure to ammonium or hydroxylamine. mRNA levels of the gene encoding nitrosocyanin (ncyA, Noc1090) were among the most elevated in response to ammonium or hydroxylamine (Figure 2; Table 1), and they were significantly reduced in ammonium-starved relative to control cells (Table 1). As for carbon fixation and assimilation, genes in the operon encoding Ribulose-1,5-bis-phosphate Carboxylase/Oxygenase (RuBisCO) was among the most highly expressed by ammonium or hydroxylamine as were genes in an operon encoding glycolytic enzymes likely involved in gluconeogenesis (Table 2). The gene encoding a key regulatory protein for N-assimilation, PII, was also highly expressed as a result of exposure to ammonium or hydroxylamine (Table 2).

Table 1.

Expression ratios of genes and gene clusters in catabolic modules for “Energy and Primary and Secondary Electron Flow.”

| Locus tag | Gene product | Predicted function | Relative expression ratios | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NH+4–I/S | NH2OH–I/S | S/C | NH+4–I/C | |||

| Noc2503 | AmoC | Ammonia monooxygenase subunit C | −1.11 | −1.10 | 1.05 | −1.06 |

| Noc2502 | AmoA | Ammonia monooxygenase subunit A | 1.22 (1.60) | 1.12 (11.5) | −1.32 | −1.09 |

| Noc2501 | AmoB | Ammonia monooxygenase subunit B | 1.41 | 1.22 | −1.47 | −1.04 |

| Noc2500 | AmoD | Periplasmic membrane protein (1 TMS) | 21.91 | 11.43 | −10.91 | 2.00 |

| Noc2499 | Hyp | Hypothetical periplasmic protein | 13.28 | 9.21 | −5.39 | 2.46 |

| Noc2498 | Hyp | Integral transmembrane protein (4TMS) | 2.43 | 1.86 | −1.56 | 1.56 |

| Noc0089 | NirK | Nitrite reductase nirK (EC:1.7.2.1) | −1.16 (10.10) | −1.17 (7.80) | −1.01 | −1.17 |

| Noc0889 | Mco | Multi-copper oxidase | 6.12 | 1.65 | −2.34 | 2.64 |

| Noc0890 | CytL | Cytochrome c P460 (NO & NH2OH detox) | 6.80 | 5.75 | −2.62 | 2.59 |

| (Noc0891) | GntR | Transcriptional regulator | 1.88 | 1.15 | 1.15 | 1.73 |

| Noc0892 | HaoA | Hydroxylamine DH (EC:1.7.2.6, [HaoA]3) | 3.88 (7.20) | 3.61 (15.3) | −3.31 | 1.17 |

| Noc0893 | HaoB | Unknown [HaoA]3-associated protein | 10.97 | 10.07 | −6.34 | 1.73 |

| Noc0894 | CycA | Cytochrome c554 | 2.77 | 2.76 | −2.28 | 1.21 |

| Noc0895 | CycB | Cytochrome cM552 | 9.40 | 9.45 | −4.13 | 2.28 |

| Noc0299 | [Fe-S] | Rieske protein (CIII, EC:1.10.2.4) | 11.85 (13.10) | 10.55 (49.60) | −4.39 | 2.70 |

| Noc0298 | CytB | Cytochrome b (CIII, EC:1.10.2.3) | 4.00 | 3.66 | −2.31 | 1.70 |

| Noc0297 | Cytc1 | Cytochrome c1 (CIII, EC:1.10.2.2) | 3.57 | 3.59 | −2.15 | 1.65 |

| Noc0552 | CccA | Di-heme c552 (COG 2010; class IV) | 13.19 | 5.79 | −2.52 | 5.22 |

| Noc0551 | DsbA | DsbA oxidoreductase | 7.15 | 2.44 | −1.40 | 5.10 |

| Noc0751 | c552 | Mono-heme c552 (COG 2863; class I) | 12.22 (3.90) | 4.69 (2.90) | −2.18 | 5.60 |

| Noc1089 | Pgb | Protoglobin (heme binds O2, CO & NO) | 8.25 | 4.58 | −3.45 | 2.41 |

| Noc1090 | NcyA | Nitrosocyanin | 29.27 | 10.76 | −14.23 | 2.06 |

| (Noc2967) | NsrR | Transcriptional regulator | 2.32 (1.50) | 1.64 (2.10) | −1.37 | 1.69 |

| Noc2969 | SenC | Nitric oxide reductase sNOR (coxBA-senC) | 8.54 | 2.82 | −1.64 | 5.22 |

| Noc2970 | NorY | Nitric oxide reductase sNOR (coxBA-senC) | 2.74 | 2.00 | −2.43 | 1.12 |

| Noc2971 | NorS | Nitric Oxide reductase sNOR (coxBA-senC) | 9.56 | 7.04 | −7.02 | 1.36 |

| Noc3044 | SU III | Type-A Complex IV HCO-1 (EC:1.9.3.1) | 3.61 | 1.55 | −2.85 | 1.27 |

| Noc3045 | SU IV | Type-A Complex IV HCO-1 (Assembly) | 6.93 | 3.00 | −5.10 | 1.36 |

| Noc3046 | SU I | Type-A Complex IV HCO-1 (EC:1.9.3.1) | 6.40 | 2.93 | −5.16 | 1.24 |

| Noc3047 | SU II | Type-A Complex IV HCO-1 (EC:1.9.3.1) | 4.73 (9.70) | 2.71 (5.00) | −4.51 | 1.05 |

| Noc3048 | Hyp | Cytoplasmic membrane protein (2 TMS) | 17.99 | 6.79 | −11.79 | 1.53 |

| Noc3049 | c552 | Mono-heme c552 (COG 2863; class I) | 27.72 | 7.35 | −12.61 | 2.20 |

| Noc3050 | c552 | Mono-heme c552 (COG 2863; class I) | 7.24 (17.10) | 3.58 (7.00) | −5.28 | 1.37 |

| Noc3073 | AtpE | FoF1-Type ATP Synthase (EC:3.6.3.14) | 9.62 | 3.73 | −3.22 | 2.99 |

| Noc3074 | AtpB-F1 | FoF1-Type ATP Synthase (EC:3.6.3.14) | 8.73 | 4.71 | −4.05 | 2.15 |

| Noc3075 | AtpC-F1 | FoF1-Type ATP Synthase (EC:3.6.3.14) | 5.94 | 3.56 | −4.01 | 1.48 |

| Noc3076 | AtpA-F1 | FoF1-Type ATP Synthase (EC:3.6.3.14) | 11.70 | 4.55 | −5.17 | 2.27 |

| Noc3077 | AtpD-F1 | FoF1-Type ATP Synthase (EC:3.6.3.14) | 7.08 | 3.47 | −4.63 | 1.53 |

| Noc3078 | AtpB-F0 | FoF1-Type ATP Synthase (EC:3.6.3.14) | 17.44 | 4.79 | −5.68 | 3.07 |

| Noc3079 | AtpC-F0 | FoF1-Type ATP Synthase (EC:3.6.3.14) | 3.76 | 2.26 | −3.05 | 1.23 |

| Noc3080 | AtpA-F0 | FoF1-Type ATP Synthase (EC:3.6.3.14) | 1.61 | 1.20 | −1.48 | 1.08 |

| Noc2552 | NuoN | NDH-1 (Reverse Complex-I) | 1.34 | −1.39 | −1.15 | 1.17 |

| Noc2553 | NuoM | NDH-1 (Reverse Complex-I) | −1.26 | −1.71 | 1.03 | −1.22 |

| Noc2554 | NuoL | NDH-1 (Reverse Complex-I) | 1.49 | −1.35 | −1.04 | 1.43 |

| Noc2555 | NuoK | NDH-1 (Reverse Complex-I) | 3.17 | 1.09 | −1.15 | 2.74 |

| Noc2556 | NuoJ | NDH-1 (Reverse Complex-I) | 3.75 | 1.51 | −1.48 | 2.54 |

| Noc2557 | NuoI | NDH-1 (Reverse Complex-I) | 3.33 | 1.46 | −1.20 | 2.76 |

| Noc2558 | NuoH | NDH-1 (Reverse Complex-I) | −1.12 | −1.18 | 1.05 | −1.07 |

| Noc2559 | NuoG | NDH-1 (Reverse Complex-I) | 2.66 | 1.32 | −1.07 | 2.47 |

| Noc2560 | NuoF | NDH-1 (Reverse Complex-I) | 1.57 | 1.36 | −1.12 | 1.40 |

| Noc2561 | NuoE | NDH-1 (Reverse Complex-I) | 5.35 | 1.69 | −1.28 | 4.19 |

| Noc2562 | NuoD | NDH-1 (Reverse Complex-I) | 2.07 | 1.33 | −1.28 | 1.62 |

| Noc2563 | NuoC | NDH-1 (Reverse Complex-I) | 3.54 | 1.94 | −1.59 | 2.23 |

| Noc2564 | NuoB | NDH-1 (Reverse Complex-I) | 2.58 | 1.38 | −1.25 | 2.07 |

| Noc2565 | NuoA | NDH-1 (Reverse Complex-I) | 4.15 | 1.38 | −1.28 | 3.25 |

| Noc0474 | NuoA | NuoAHJKLLMN (C I-membrane arm) | −1.89 | −1.45 | 1.09 | −1.73 |

| Noc0475 | NuoH | NuoAHJKLLMN (C I-membrane arm) | −12.29 | −2.02 | 1.23 | −9.98 |

| Noc0476 | NuoJ | NuoAHJKLLMN (C I-membrane arm) | −8.88 | −2.01 | 1.29 | −6.90 |

| Noc0477 | NuoK | NuoAHJKLLMN (C I-membrane arm) | −3.39 | −1.43 | 1.23 | −2.75 |

| Noc0478 | NuoL | NuoAHJKLLMN (C I-membrane arm) | −10.05 | −1.99 | 1.34 | −7.48 |

| Noc0479 | NuoL | NuoAHJKLLMN (C I-membrane arm) | −11.52 | −2.08 | 1.39 | −8.27 |

| Noc0480 | NuoM | NuoAHJKLLMN (C I-membrane arm) | −5.23 | −2.06 | 1.23 | −4.24 |

| Noc0481 | NuoN | NuoAHJKLLMN (C I-membrane arm) | −3.50 | −1.71 | 1.20 | −2.93 |

| Noc1797 | Cyt_C | Mono-heme cytochrome c protein | −7.34 | −1.37 | 9.24 | 1.25 |

| Noc1798 | Cyt_C | Mono-heme cytochrome c protein | −7.52 | −1.51 | 6.86 | −1.10 |

| Noc1799 | NemA | NADH-flavin oxidoreductase (EC:1.3.1.34) | −9.95 | −1.43 | 12.43 | 1.25 |

| Noc1800 | Cyt_C | Di-heme cytochrome c protein | −15.51 | −1.49 | 13.70 | −1.13 |

Values represent average ratios from four hybridization experiments per gene, per treatment. Bolded ratios indicate those that are considered to have significant differences (changes greater than 5-fold) in gene expression between compared treatments. Values in parentheses represent ratios from qPCR experiments reported previously (Graham et al., 2011) employing the same RNA preparations as used for the microarray hybridizations. Values in bold indicate that both methods yielded consistent results.

Table 2.

Expression ratios of genes and gene clusters in catabolic modules for “Carbon Fixation and Assimilation” and “Nitrogen Assimilation.”

| Locus tag | Gene product | Predicted function | Relative expression ratios | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NH+4–I/S | NH2OH–I/S | S/C | NH+4–I/C | |||

| Noc0330 | Hyp | Associated with RuBisCO operon | 17.64 | 19.07 | −2.84 | 6.20 |

| Noc0331 | CbbX | RuBisCO (ATPase) | 24.89 | 23.83 | −4.38 | 5.69 |

| Noc0332 | CbbS | RuBisCO (small subunit) | 18.88 | 18.26 | −11.07 | 1.71 |

| Noc0333 | CbbL | RuBisCO (large subunit) | 23.47 | 21.31 | −12.45 | 1.88 |

| Noc2808 | Tkt2 | Transketolase (EC:2.2.1.1) | 11.20 | 6.79 | −4.51 | 2.49 |

| Noc2807 | GapA | Glyceraldehyde-3-P dehydrogenase (EC:1.2.1.12) | 7.88 | 5.81 | −4.70 | 1.68 |

| Noc2806 | Pgk | Phosphoglycerate kinase (EC:2.7.2.3) | 2.74 | 2.31 | −2.18 | 1.25 |

| Noc2805 | PykF | Pyruvate kinase (EC:2.7.1.40) | 2.17 | 1.62 | −1.40 | 1.55 |

| Noc2804 | ALDOB | Fructose-bis-phosfate aldolase (EC:4.1.2.13) | 5.88 | 4.54 | −3.12 | 1.89 |

| Noc2492 | RPE | Ribulose-phosfate 3-epimerase (EC:5.1.3.1) | 9.53 | 6.06 | −2.02 | 4.73 |

| Noc2493 | PGLP | Phosphoglycolate phosphatase (EC:3.1.3.18) | 2.59 | 2.43 | −1.57 | 1.65 |

| Noc0715 | GlnB/K | Nitrogen regulatory protein P-II | 13.82 | 6.23 | −2.28 | 6.05 |

| Noc2573 | CPS | Carbamoyl-phosfate synthase, small subunit | 6.97 | 2.84 | −1.51 | 4.63 |

| Noc2572 | CPS | Carbamoyl-phoshate synthase, large subunit | 4.96 | 1.56 | −1.39 | 3.59 |

Values represent average ratios from four hybridization experiments per gene, per treatment. Bolded ratios indicate those that are considered to have significant differences in gene expression between compared treatments (changes greater than 5-fold).

Other noteworthy catabolic inventory induced by ammonium or hydroxylamine included genes encoding cytochrome P460 (cycL, Noc0890), mono- (Noc3049) and di-heme cytochrome c552 proteins (Noc0552), Rieske protein of Complex III (Noc0299), and the NorS component (Noce2971) of cytochrome c-linked nitric oxide reductase, sNOR (Table 1). Stress tolerance genes encoding tellurium resistance protein TerB (Noc1001) and the protein chaperone GroES (Noc2922), and a gene encoding the acyl carrier protein AcpP (Noc1664) were also among the most highly induced by exposure to ammonium or hydroxylamine (Table 3).

Table 3.

Expression ratios of genes and gene clusters in other functional categories.

| Locus tag | Gene product | Predicted function | Relative expression ratios | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NH+4–I/S | NH2OH–I/S | S/C | NH+4–I/C | |||

| DNA | ||||||

| Noc0448 | HsdR | Type I site-specific deoxyribonuclease | −11.04 | −2.12 | 1.30 | −8.51 |

| Noc0447 | HsdR | Type I restriction-modification system endonuclease | −1.27 | −1.86 | 1.28 | 1.01 |

| Noc0446 | HsdS | Restriction endonuclease S subunit | −10.81 | −2.16 | 1.21 | −8.92 |

| Noc1205 | HsdR | Type III restriction enzyme | −1.67 | −1.31 | 1.20 | −1.38 |

| Noc1204 | HsdS | Restriction modification system DNA specificity domain | −3.72 | −1.74 | 1.19 | −3.11 |

| Noc1203 | PnpA | DNA polymerase, beta-like region | −8.15 | −2.21 | 1.42 | −5.74 |

| Noc1202 | DUF86 | Hypothetical | −10.29 | −2.38 | 1.49 | −6.91 |

| Noc1201 | YfiC | N-6 DNA methylase | −5.04 | −1.77 | 1.21 | −4.16 |

| Noc2535 | PnpA | DNA polymerase, beta-like region | −8.05 | −1.92 | 1.21 | −6.67 |

| Noc2536 | PnpB | Nucleotidyltransferase substrate binding protein | −5.35 | −1.43 | 1.19 | −4.48 |

| TRANSCRIPTION | ||||||

| Noc1918 | GreA/B | Transcription elongation factor | 25.52 | 1.15 | −20.84 | 1.22 |

| Noc1917 | Hyp | Hypothetical protein | 13.90 | −1.67 | −11.56 | 1.20 |

| Noc2610 | RNP-1 | RNA binding protein | 16.95 | 4.22 | −2.27 | 7.46 |

| Noc2010 | DksA | C-4 type zinc finger protein | 16.02 | 7.52 | −2.16 | 7.43 |

| TRANSLATION | ||||||

| Noc2332 | RplL | Large subunit ribosomal protein L7/L12 | 23.95 | 10.40 | −5.74 | 4.17 |

| Noc2640 | RpmB | Large subunit ribosomal protein L28 | 16.45 | 14.21 | −6.57 | 2.51 |

| Noc2641 | RpmG | Large subunit ribosomal protein L33 | 12.43 | 11.30 | −5.51 | 2.28 |

| Noc2309 | RplF | Large subunit ribosomal protein L6 | 11.44 | 3.99 | −5.10 | 2.24 |

| Noc3037 | RpsT | Small subunit ribosomal protein S20 | 11.18 | 3.58 | −1.63 | 6.86 |

| Noc2319 | RplV | Large subunit ribosomal protein L22 | 10.69 | 8.93 | −5.04 | 2.13 |

| Noc2122 | YhbC | Ribosomal maturation protein | 9.71 | 4.08 | −1.76 | 5.51 |

| Noc0042 | RpsU | Small subunit ribosomal protein S21 | 5.74 | 1.26 | −1.14 | 5.04 |

| FLAGELLA/PILI | ||||||

| Noc0833 | MotA | Proton channel | −3.24 | −1.77 | 1.22 | −2.66 |

| Noc0834 | MotB | Flagellar motor protein MotB | −6.70 | −1.77 | 1.19 | −5.62 |

| Noc2365 | FliD | Flagellar hook-associated protein 2 | −7.15 | −2.09 | 1.40 | −5.14 |

| Noc1658 | FliH | Flagellar assembly | 7.71 | 1.93 | −1.37 | 5.64 |

| Noc2270 | FimT | Type-IV fimbiral pilin related signal peptide protein | −10.24 | −1.88 | 1.24 | −8.24 |

| Noc2271 | PilV | Type IV pilus assembly protein | −6.18 | −1.96 | 1.41 | −4.39 |

| Noc2272 | PilW | Type IV pilus assembly protein | −5.49 | −2.28 | 1.61 | −3.40 |

| Noc2273 | PilX | Type IV pilus assembly protein | −3.33 | −1.79 | 1.50 | −2.23 |

| Noc2274 | PilY | Type IV pilus assembly protein PilY1 | −6.61 | −1.97 | 1.26 | −5.25 |

| Noc2275 | PilE | Bacterial general secretion pathway protein H | −2.78 | −1.48 | 1.27 | −2.18 |

| TRANSPORT | ||||||

| Noc1626 | Sul1 | Sulfate transporter | 20.35 | 3.42 | −16.51 | 1.24 |

| Noc1194 | Fur | Ferric uptake regulation protein | 6.29 | 1.84 | −1.17 | 5.35 |

| Noc0294 | CzcA | Heavy metal efflux pump; CzcA family | −6.53 | −1.89 | 1.17 | −5.54 |

| STRESS TOLERANCE | ||||||

| Noc1001 | TerB | Tellurium resistance | 16.54 | 14.73 | −6.64 | 2.50 |

| Noc2922 | GroES | Protein folding chaperone | 14.25 | 6.77 | −2.68 | 5.30 |

| LIPIDS | ||||||

| Noc1664 | AcpP | Acyl carrier protein; fatty acid biosynthesis | 27.53 | 7.38 | −5.36 | 5.13 |

| Noc0157 | HlyIII | Channel protein, hemolysin III family COG1272 | −13.35 | −2.22 | 1.36 | −9.83 |

Values represent average ratios from four hybridization experiments per gene, per treatment. Bolded ratios indicate those that are considered to have significant differences in gene expression between compared treatments (changes greater than 5-fold).

Data from RT-qPCR assays presented in Table 1 were performed using the same RNA preparations as for microarray hybridizations, employing primer sets designed against core catabolic genes as reported elsewhere (Graham et al., 2011). Only few of the ratios derived from RT-qPCR matched those from microarray hybridization experiments; for instance, genes encoding haoA (Noc0892), nirK nitrite reductase (Noc0089) and two genes in the Complex IV terminal oxidase gene cluster (Noc3047, 3050) were highly expressed according to RT-qPCR in cells exposed to ammonium or hydroxylamine, but were not highly expressed according to microarray hybridization. Also surprising was high expression of amoA upon exposure to hydroxylamine, but not to ammonium, according to RT-qPCR, but not microarray hybridization experiments. The pattern of amoA expression using arrays is also in contradiction to prior studies on regulation of the ammonia monooxygenase operon by ammonium in N. oceani, which was assessed by RT-qPCR and Northern analysis (El Sheikh and Klotz, 2008; El Sheikh et al., 2008).

Significantly reduced steady-state transcript levels were identified only when comparing results from ammonium-exposed and starved cells, indicating transcript degradation or gene repression as part of the ammonium-responsive stimulon rather than as a response to a change in cellular redox status.

Genes responsive to ammonium as a signaling molecule

Genes for which significant changes in transcript levels were identified after exposure to ammonium, but not to hydroxylamine, relative to both starved and non-starved control cells can be considered bona fide components of the ammonia-responsive stimulon. Such genes with increased transcript levels included those encoding DsbA disulfide oxidoreductase (Noc0551), a mono-heme cytochrome c552 (Noc0751), the SenC component of sNOR nitric oxide reductase (Noc2969), two transcriptional regulators (Noc2610, 2010), ribosomal structural proteins (Noc3037, 2122, 0042), flagellar assembly protein FliH (Noc1658), and a ferric uptake regulatory protein (Noc1194) (Tables 1, 3). Genes with decreased transcript levels included several that contribute to synthesis of forward Complex I (Noc0475-0476, 0478-0479), restriction endonucleases and DNA polymerases (Noc0448, 0446, 1203, 2535), flagellar and Type IV pilus proteins (Noc0834, 2365, 2270-2272, 2274), a Czc heavy metal efflux pump (Noc0294), and a hemolysin channel protein (Noc0157) (Tables 1, 3).

A number of genes also showed significant changes in transcript levels upon exposure to ammonium, but not hydroxylamine, relative to the ammonium-starved, but not to the control cells taken directly from batch cultures. Highly expressed genes in this category included those encoding a multi-copper oxidase (Noc0889), clusters encoding Complex IV terminal oxidase (Noc3045, 3036, 3050), F0F1 ATPase (Noc3073-3078) and carbamoyl-phosfate synthase (Noc2573-2572), and a very highly expressed sulfate transporter (Noc1626) (Tables 1–3). Genes with reduced transcript levels in this category included a four-gene cluster encoding cytochrome c related proteins (Noc1797-1800).

Degradation of transcripts during starvation from ammonium

Transcript degradation was assessed by comparing expression of genes in ammonium-starved cells relative to non-starved control cells. The most depleted transcripts in starved cells included those encoding the amoD transcript (member of the amo operon, Noc2500), the haoB transcript (member of the hao operon, Noc0893), ncyA (nitrosocyanin, Noc1090), the norS transcript (member of the nitric oxide reductase operon, Noc2971), several genes in the Complex IV terminal oxidase gene cluster (Noc3045-3050), transcripts encoding CbbL and CbbS of RuBisCO (Noc0332-0333), transcriptional elongation factors (Noc1918-1917), a number of ribosomal proteins (Noc2332, 2640, 2641, 2309, 2319), the ammonium-induced sulfate transporter (Noc1626), the TerB tellurium resistance protein (Noc1001), and acyl carrier protein AcpP (Noc1664) (Tables 1–3). Only the four-gene cluster encoding cytochrome c related proteins with unknown function was represented with higher transcript levels in starved relative to non-starved cells (Noc1797-1800) (Table 1).

Discussion

The primary findings from this study are that: (1) N. oceani was far more responsive to general changes in redox/energy status than to ammonium as a signaling molecule alone, (2) genes involved in carbon fixation were among the most highly affected by a change in redox/energy status, which makes sense given that this is the most energy and reductant requiring process in chemolithotrophic metabolism; (3) several genes involved in primary catabolic electron flow were regulated by changes in redox/energy status, however, not all clustered or operonal genes were represented by equal and/or equal changes in transcript levels including those genes shown to be regulated by ammonium in prior studies (Sayavedra-Soto et al., 1996; El Sheikh and Klotz, 2008; El Sheikh et al., 2008); and (4) transcription of ncyA (nitrosocyanin) was the most highly responsive to changes in redox/energy status, indicating an essential function to bacterial ammonia chemolithotrophy. Patterns of transcript abundance in N. oceani were significantly different from those observed in certain marine metatranscriptomes where amoA, amtB (ammonium transporter), and nirK (nitrite reductase) mRNAs from ammonia-oxidizing thaumarchaeota were among the most highly represented (Gifford et al., 2010). This perhaps indicates a different response to redox/energy status between the marine ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and thaumarchaeota. Furthermore, the results suggest that key inventory and/or its principle regulation may be entirely different between representatives of ammonia-oxidizing chemolithotrophs from two domains of life.

Several genes encoding primary catabolic and carbon fixation inventory were responsive to ammonium or hydroxylamine and also exhibited reduced expression during ammonium-starvation. This suggests a direct linkage between energy homeostasis—the provisional usage of catabolic energy and reducing power—with carbon fixation and oxidative phosphorylation. The role of nitrosocyanin in catalysis and electron transfer has been discussed controversially in the literature without defining its role in ammonia chemolithotrophy other than its exclusivity to obligate ammonia-oxidizing bacteria (Klotz and Stein, 2011). The null hypothesis to disprove in the future is that nitrosocyanin determines whether electrons extracted by HAO from hydroxylamine will reduce either cytochromes c554 or cM552. The specific electron acceptor will then determine whether electrons directly enter the quinone pool or whether they become available for distribution to other electron sinks such as sNOR. Given that two electrons can contribute to energy conservation per ammonia molecule oxidized, complemented by the many possible electrogenic and electroneutral electron flow processes in the branched oxidative electron transport chain of Nitrosococcus (Klotz and Stein, 2011; Simon and Klotz, 2013), the need for controlling the direction of electron flow is evident. Increased expression of genes encoding components of AMO, HAO, CytB, cytochrome P460, sNOR, and nitrosocyanin with either ammonium or hydroxylamine suggests that oxidative electron flow favors not only nitrite production but, in particular the removal of nitric oxide by sNOR (reduction to N2O) or cytochrome P460 (oxidation to nitrite) when NO is produced by oxidation of hydroxylamine (Stein, 2011). This activity makes sense for maximizing electron flow between AMO/HAO with Complexes III and IV at high substrate oxidation rates by using periplasmic cytochromes and nitric oxide reductase as catabolic overflow electron sinks (Stein, 2011).

Although the ammonia stimulon as revealed from the microarray data was sparsely populated compared to the gene complement regulated by redox/energy status, it can be concluded that increased transcript availability of genes encoding Complex IV and ATPase along with decreased transcript availability of genes encoding forward Complex I suggests a boost to the production of proton motive force and ATP. This result is consistent with the maximization of catabolic electron flow and upregulation of periplasmic electron sinks to optimize electron flow to the terminal oxidase (Stein, 2011).

One caveat of the results presented in Table 1 is the lack of consistency between the data sets generated with the microarray approach and in the RT-qPCR experiments. Although neither method revealed increased steady-state levels of amoA mRNA following exposure to ammonium, amoA mRNA levels following exposure to hydroxylamine and haoA and nirK transcript levels following exposure to either ammonium or hydroxylamine were significantly higher when using RT-qPCR compared to employing the microarray approach. It is possible that that the identified differences in both data sets are due to the inherent differences in hybridization kinetics between the two technologies, differential processing that occurs at least in amo (El Sheikh and Klotz, 2008) and hao (Poret-Peterson et al., 2008) transcripts, and differences in location of hybridizing regions across each gene. It is also important to realize that the analysis of both raw data sets utilized different normalization procedures.

The differences observed between techniques suggest that a quantitation of differences in transcriptional regulation and processing should be based on a gene-by-gene analysis using linearized standard templates in order to reveal why transcripts of certain members of gene clusters and operons are being detected at higher copy numbers than others across a microarray. Regardless of which technique is more accurate, when comparing gene expression data in N. oceani with that from betaproteobacterial ammonia-oxidizers (Bollmann et al., 2005; Wei et al., 2006; Cua and Stein, 2011; Kartal et al., 2012), it is evident that ammonia-dependent chemolithotrophy does not follow a single regulatory principle. While each phylotype appears to have maintained regulatory principles tied to the history of a given genome, they appear to have also adapted slightly different regulatory features that they acquired together with cohort-specific inventory to maximize their survival and growth, a process that likely also varied based on the environment (i.e., marine vs. freshwater and soil).

Taken together, this study effectively separated the effects of ammonium in its unprotonated form (ammonia) as an energy source from its role as a signaling molecule on regulatory processes in N. oceani that reflect themselves in varying steady-state transcript levels. The experimentally forced changes to cellular redox/energy status of N. oceani cells exerted a strong effect on inventory implicated in carbon fixation and catabolic electron flow to the terminal oxidase, indicating that these two functions are the most significant to survival and growth of this bacterium. It has been shown before that minuscule concentrations of ammonium are sufficient for the induction of gene expression (El Sheikh and Klotz, 2008; El Sheikh et al., 2008). In the marine environment, obligate ammonia-oxidizing bacteria are likely not thwarted by access to ammonium, but rather by environmental changes that could result in misdirection of electron flow along the catabolic pipeline. The identified coordinated expression of catabolic inventory, periplasmic electron sinks, nitrosocyanin and carbon fixation genes thus suggests that N. oceani is well adapted to quickly sense changes in energy availability to optimize growth and survival in a changing environment.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Martin G. Klotz was funded by the NSF (grants EF-0404129, EF-0541797 and MCB-0948292/1202648) and incentive funds provided by the University of North Carolina. Lisa Y. Stein was funded by a Discovery Grant from the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://www.frontiersin.org/Evolutionary_and_Genomic_Microbiology/10.3389/fmicb.2013.00277/abstract

References

- Arciero D. M., Pierce B. S., Hendrich M. P., Hooper A. B. (2002). Nitrosocyanin, a red cupredoxin-like protein from Nitrosomonas europaea. Biochemistry 41, 1703–1709 10.1021/bi015908w [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arp D. J., Chain P. S., Klotz M. G. (2007). The impact of genome analyses on our understanding of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 61, 503–528 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093449 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arp D. J., Sayavedra-Soto L. A., Hommes N. G. (2002). Molecular biology and biochemistry of ammonia oxidation by Nitrosomonas europaea. Arch. Microbiol. 178, 250–255 10.1007/s00203-002-0452-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basumallick L., Sarangi R., Debeergeorge S., Elmore B., Hooper A. B., Hedman B., et al. (2005). Spectroscopic and density functional studies of the red copper site in nitrosocyanin: role of the protein in determining active site geometric and electronic structure. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 127, 3531–3544 10.1021/ja044412+ [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergmann D. J., Hooper A. B., Klotz M. G. (2005). Structure and sequence conservation of hao cluster genes of autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing bacteria: evidence for their evolutionary history. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 5371–5382 10.1128/AEM.71.9.5371-5382.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer S., Gilch S., Meyer O., Schmidt I. (2009). Transcription of genes coding for metabolic key functions in Nitrosomonas europaea during aerobic and anaerobic growth. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 16, 187–197 10.1159/000142531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollmann A., Schmidt I., Saunders A. M., Nicolaisen M. H. (2005). Influence of starvation on potential ammonia-oxidizing activity and amoA mRNA levels of Nitrosospira briensis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 1276–1282 10.1128/AEM.71.3.1276-1282.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollmann A., Sedlacek C. J., Norton J., Laanbroek H. J., Suwa Y., Stein L. Y., et al. (2012). Complete genome sequence of Nitrosomonas sp. Is79—an ammonia oxidizing bacterium adapted to low ammonium. Stand. Genomic Sci. 7, 351–896 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M. A., Chain P. S., Dang H., El Sheikh A. F., Norton J. M., Ward N. L., et al. (2011a). Nitrosococcus watsonii sp. nov., a new species of marine obligate ammonia-oxidizing bacteria that is not omnipresent in the world's oceans: calls to validate the names ‘Nitrosococcus halophilus’ and ‘Nitrosomonas mobilis.’ FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 76, 39–48 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2010.01027.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M. A., Nyerges G., Kozlowski J. A., Poret-Peterson A. T., Stein L. Y., Klotz M. G. (2011b). Model of the molecular basis for hydroxylamine oxidation and nitrous oxide production in methanotrophic bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 322, 82–89 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02340.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho C. M.-H., Yan T., Liu X., Wu L., Zhou J., Stein L. Y. (2006). Transcriptome of Nitrosomonas europaea with a disrupted nitrite reductase (nirK) gene. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 4450–4454 10.1128/AEM.02958-05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman N. V., Le N. B., Ly M. A., Ogawa H. E., McCarl V., Wilson N. L., et al. (2012). Hydrocarbon monooxygenase in Mycobacterium: recombinant expression of a member of the ammonia monooxygenase superfamily. ISME J. 6, 171–182 10.1038/ismej.2011.98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cua L. S., Stein L. Y. (2011). Effects of nitrite on ammonia-oxidizing activity and gene regulation in three ammonia-oxidizing bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 319, 169–175 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2011.02277.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elmore B. O., Bergmann D. J., Klotz M. G., Hooper A. B. (2007). Cytochromes P460 and c'-beta; a new family of high-spin cytochromes c. FEBS Lett. 581, 911–916 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.01.068 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Sheikh A. F., Klotz M. G. (2008). Ammonia-dependent differential regulation of the gene cluster that encodes ammonia monooxygenase in Nitrosococcus oceani ATCC 19707. Environ. Microbiol. 10, 3026–3035 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01766.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El Sheikh A. F., Poret-Peterson A. T., Klotz M. G. (2008). Characterization of two new genes, amoR and amoD, in the amo operon of the marine ammonia oxidizer Nitrosococcus oceani ATCC 19707. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 312–318 10.1128/AEM.01654-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gifford S. M., Sharma S., Rinta-Kanto J. M., Moran M. A. (2010). Quantitative analysis of a deeply sequenced marine microbial metatranscriptome. ISME J. 5, 461–472 10.1038/ismej.2010.141 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graham J. E., Wantland N. B., Campbell M., Klotz M. G. (2011). Characterizing bacterial gene expression in nitrogen cycle metabolism with RT-qPCR, in Methods Enzymol., Vol. 46 : Research on Nitrification and Related Processes, Pt B, eds. Klotz M. G., Stein L.Y. (San Diego, CA: Elsevier Academic Press Inc; ), 345–372 10.1016/B978-0-12-386489-5.00014-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanson T. E., Campbell B. J., Kalis K. M., Campbell M. A., Klotz M. G. (2013). Nitrate ammonification by Nautilia profundicola AmH: experimental evidence consistent with a free hydroxylamine intermediate. Front. Microbiol. 4:180 10.3389/fmicb.2013.00180 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hommes N. G., Sayavedra-Soto L. A., Arp D. J. (2002). The roles of the three gene copies encoding hydroxylamine oxidoreductase in Nitrosomonas europaea. Arch. Microbiol. 178, 471–476 10.1007/s00203-002-0477-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooper A. B., Arciero D. M., Bergmann D., Hendrich M. P. (2005). The oxidation of ammonia as an energy source in bacteria in respiration, in Respiration in Archaea and Bacteria: Diversity of Procaryotic Respiratory Systems, ed Zannoni D. (Dordrecht: Springer; ), 121–147 [Google Scholar]

- Hyman M. R., Arp D. J. (1995). Effects of ammonia on the de novo synthesis of polypeptides in cells of Nitrosomonas europaea denied ammonia as an energy source. J. Bacteriol. 177, 4974–4979 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kartal B., Wessels H., van der Biezen E., Francoijs K. J., Jetten M. S. M., Klotz M. G., et al. (2012). Effects of nitrogen dioxide and anoxia on global gene and protein expression in long-term continuous cultures of Nitrosomonas eutropha C91. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 78, 4788–4794 10.1128/AEM.00668-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kern M., Klotz M. G., Simon J. (2011). The Wolinella succinogenes mcc gene cluster encodes an unconventional respiratory sulfite reduction system. Mol. Microbiol. 82, 1515–1530 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07906.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H. J., Zatsman A., Upadhyay A. K., Whittaker M., Bergmann D., Hendrich M. P., et al. (2008). Membrane tetraheme cytochrome cm552 of the ammonia-oxidizing Nitrosomonas europaea: a ubiquinone reductase. Biochemistry 47, 6539–6551 10.1021/bi8001264 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz M. G., Arp D. J., Chain P. S., El-Sheikh A. F., Hauser L. J., Hommes N. G., et al. (2006). Complete genome sequence of the marine, chemolithoautotrophic, ammonia-oxidizing bacterium Nitrosococcus oceani ATCC 19707. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 6299–6315 10.1128/AEM.00463-06 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz M. G., Schmid M. C., Strous M., Op Den Camp H. J., Jetten M. S., Hooper A. B. (2008). Evolution of an octahaem cytochrome c protein family that is key to aerobic and anaerobic ammonia oxidation by bacteria. Environ. Microbiol. 10, 3150–3163 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2008.01733.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz M. G., Stein L. Y. (2008). Nitrifier genomics and evolution of the nitrogen cycle. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 278, 146–156 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2007.00970.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz M. G., Stein L. Y. (2011). Genomics of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and insights to their evolution, in Nitrification, eds Ward B. B., Arp D. J., Klotz M. G. (Washington, DC: ASM Press; ), 57–93 [Google Scholar]

- O'Mullan G. D., Ward B. B. (2005). Relationship of temporal and spatial variabilities of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria to nitrification rates in Monterey Bay, California. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 71, 697–705 10.1128/AEM.71.2.697-705.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poret-Peterson A. T., Graham J. E., Gulledge J., Klotz M. G. (2008). Transcription of nitrification genes by the methane-oxidizing bacterium, Methylococcus capsulatus strain Bath. ISME J. 2, 1213–1220 10.1038/ismej.2008.71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayavedra-Soto L. A., Hamamura N., Liu C.-W., Kimbrel J. A., Chang J. H., Arp D. J. (2011). The membrane-associated monooxygenase in the butane-oxidizing Gram-positive bacterium Nocardioides sp. strain CF8 is a novel member of the AMO/PMO family. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 3, 1758–2229 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2010.00239.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayavedra-Soto L. A., Hommes N. G., Arp D. J. (1994). Characterization of the gene encoding hydroxylamine oxidoreductase in Nitrosomonas europaea. J. Bacteriol. 176, 504–510 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sayavedra-Soto L. A., Hommes N. G., Russell S. A., Arp D. J. (1996). Induction of ammonia monooxygenase and hydroxylamine oxidoreductase mRNAs by ammonium in Nitrosomonas europaea. Mol. Microbiol. 20, 541–548 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1996.5391062.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon J., Klotz M. G. (2013). Diversity and evolution of bioenergetic systems involved in microbial nitrogen compound transformations. Bioch. Biophys. Acta. 1827, 114–132 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.07.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein L. Y. (2011). Heterotrophic nitrification and nitrifier denitrification, in Nitrification, eds Ward B. B., Arp D. J., Klotz M. G. (Washington, DC: ASM Press; ), 95–114 [Google Scholar]

- Stein L. Y., Arp D. J., Hyman M. R. (1997). Regulation of the synthesis and activity of ammonia monooxygenase in Nitrosomonas europaea by altering pH to affect NH3 availability. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 63, 4588–4592 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stein L. Y., Klotz M. G. (2011). Nitrifying and denitrifying pathways of methanotrophic bacteria. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 39, 1826–1831 10.1042/BST20110712 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavormina P. L., Orphan V. J., Kalyuzhnaya M. G., Jetten M. S. M., Klotz M. G. (2011). A novel family of functional operons encoding methane/ammonia monooxygenase-related proteins in gammaproteobacterial methanotrophs. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 3, 91–100 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2010.00192.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tavormina P. L., Ussler W., Steele J. A., Connon S. A., Klotz M. G., Orphan V. J. (2013). Abundance and distribution of diverse membrane-bound monooxygenase (Cu-MMO) genes within the Costa Rica oxygen minimum zone. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 5, 414–423 10.1111/1758-2229.12025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Upadhyay A. K., Hooper A. B., Hendrich M. P. (2006). NO reductase activity of the tetraheme cytochrome c554 of Nitrosomonas europaea. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128, 4330–4337 10.1021/ja055183+ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker C. B., de La Torre J. R., Klotz M. G., Urakawa H., Pinel N., Arp D. J., et al. (2010). Nitrosopumilus maritimus genome reveals unique mechanisms for nitrification and autotrophy in globally distributed marine crenarchaea. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 8818–8823 10.1073/pnas.0913533107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wei X., Yan T., Hommes N. G., Liu X., Wu L., McAlvin C., et al. (2006). Transcript profiles of Nitrosomonas europaea during growth and upon deprivation of ammonia and carbonate. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 257, 76–83 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2006.00152.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.