Abstract

This study examined the impact of point-of-sale (POS) tobacco marketing restrictions in Australia and Canada, in relation to the United Kingdom and the United States where there were no such restrictions during the study period (2006–10). The data came from the International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey, a prospective multi-country cohort survey of adult smokers. In jurisdictions where POS display bans were implemented, smokers’ reported exposure to tobacco marketing declined markedly. From 2006 to 2010, in Canada, the percentages noticing POS tobacco displays declined from 74.1 to 6.1% [adjusted odds ratio (OR) = 0.26, P < 0.001]; and reported exposure to POS tobacco advertising decreased from 40.3 to 14.1% (adjusted OR = 0.61, P < 0.001). Similarly, in Australia, noticing of POS displays decreased from 73.9 to 42.9%. In contrast, exposure to POS marketing in the United States and United Kingdom remained high during this period. In parallel, there were declines in reported exposures to other forms of advertising/promotion in Canada and Australia, but again, not in the United States or United Kingdom. Impulse purchasing of cigarettes was lower in places that enacted POS display bans. These findings indicate that implementing POS tobacco display bans does result in lower exposure to tobacco marketing and less frequent impulse purchasing of cigarettes.

Introduction

In the new era of tobacco control, advertising and promotion of tobacco products has been prohibited in many countries in traditional media outlets such as broadcast (i.e. television and radio), print and outdoor billboards. As a result of these restrictions, the tobacco industry has increasingly turned to retail point-of-sale (POS) displays as a means of marketing their products to consumers [1–3]. POS tobacco displays have always been an important way for tobacco marketers to reach consumers as such displays often advertise price promotions (e.g. 2 for 1) and promote impulse purchases [1, 4–8]. Indeed, the mere presence of advertising for brands helps to normalize tobacco products in the eyes of the public (especially among young people) [2–4, 9, 10]. A recent review on tobacco marketing restrictions found that POS displays are the least regulated marketing channel and highlighted a need to address the immediate and long-term consequences of such marketing [11].

Some jurisdictions have strengthened tobacco marketing restrictions to include prohibiting the display of tobacco products at the POS. Iceland was the first country to implement a tobacco display ban in 2001. Since then, a number of jurisdictions have adopted POS marketing restrictions for tobacco products, including Thailand (in September 2005), Ireland (July 2009), Norway (January 2010), Finland (January 2012), Canada and Australia (both with a gradual implementation) [12–15].

The public supports limiting or banning POS display of tobacco products [14–16]. For example, Brown et al. found that the levels of support for a ban on POS displays were high (ranged between 55 and 82%) among adult smokers, and support was comparable across 10 Canadian provinces, irrespective of whether tobacco displays within shops had been banned in each of the studied provinces [15].

In Canada and Iceland where POS display bans implemented as part of comprehensive tobacco control measures, there has been a decrease in youth and/or adult smoking prevalence [17–19], and the bans may have contributed to these reductions, but there was no evaluation of their independent effect.

As falls in smoking prevalence resulting from POS tobacco display bans (and other tobacco control measures) are likely to be gradual rather than immediate [13, 20, 21], it is important to monitor the changes of exposure to tobacco displays and overall tobacco marketing over time and across different jurisdictions. However, little has been documented about the differences in adult smokers’ exposure to tobacco advertising and promotional activities between countries with strong POS display restrictions and those that have weak (or no) policies. In addition, there is very little published research longitudinally assessing the impact of POS display bans on adult smokers’ cigarette purchasing behaviors in countries with varying restrictions.

This study examines the variability in POS marketing restrictions in Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States and the effect of these varying restrictions on adult smokers’ exposure to tobacco product marketing and their cigarette purchasing behaviors. By early 2011, all Canadian provinces/territories had adopted POS tobacco display bans; some Australian states/territories also started to do so since late 2009; whereas in the United Kingdom and United States there were no systematic bans implemented by early 2011. (Note: In its Healthy Lives, Healthy People: A Tobacco Control Plan for England, published in March 2011, the UK Government included a commitment to implement POS legislation in England in large shops from April 2012 and in smaller shops from April 2015 [22].)

Table I summarizes the POS display ban implementation dates for Canadian and Australian jurisdictions [along with data collection dates for our studied waves of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey].

Table I.

POS tobacco display ban implementation date and data collection date

| Country/jurisdiction | Implementation date | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Canadian provinces/territories | ||

| Manitoba | 1 January 2004 | Pre W5a |

| Nunavutb | 1 February 2004 | Pre W5 |

| Saskatchewan | 1 January 2005c | Pre W5 |

| Prince Edward Island | 1 June 2006 | Pre W5 |

| Wave 5 data collection: October 2006–February 2007 | ||

| Northwest Territories | 21 January 2007 | During W5 |

| Nova Scotia | 31 March 2007 | Between W5 and W6 |

| Wave 6 data collection: September 2007–February 2008 | ||

| British Columbia | 31 March 2008 | Between W6 and W7 |

| Ontario | 31 May 2008 | Between W6 and W7 |

| Quebec | 31 May 2008 | Between W6 and W7 |

| Alberta | 1 July 2008 | Between W6 and W7 |

| Wave 7 data collection: October 2008–July 2009 | ||

| New Brunswick | 1 January 2009 | During W7 |

| Yukon | 15 May 2009 | During W7 |

| Newfoundland and Labrador | 1 January 2010 | Between W7 and W8 |

| Australian states/territories | ||

| Australian Capital Territory | 31 December 2009 | Between W7 and W8 |

| New South Wales | 1 July 2010 | Between W7 and W8 |

| Wave 8 data collection: 13 July 2010–May 2011 | ||

| Western Australia | 22 September 2010 | During W8 |

| Victoria | 1 January 2011 | During W8 |

| Northern Territory | 2 January 2011 | During W8 |

| Tasmania | 1 February 2011 | During W8 |

| Queensland | 18 November 2011 | Post W8 |

| South Australia | 1 January 2012 | Post W8 |

a‘W’ means ‘Wave’ of the ITC-4 Survey. bNunavut and other two Canadian territories (Yukon and Northwest Territories) were excluded in the analysis (excluded from the sampling frame because of small population size). cThe Canadian province of Saskatchewan banned retail display of tobacco in 2002, but this law was challenged by the tobacco industry and was struck down. However, the Supreme Court of Canada unanimously upheld the constitutionality of the legislation in January 2005.

Methods

Data source and participants

The data for this study came from Wave 5 to Wave 8 of the ITC Four Country Survey (the ITC-4 Survey), which has been running annually since 2002 in Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom and the United States. A detailed description of the conceptual framework and methods of the ITC-4 Survey has been reported by Fong et al. [23] and Thompson et al. [24], and more detail is available at http://www.itcproject.org. Briefly, the ITC-4 Survey employs a prospective multi-country cohort design and involves telephone surveys of representative cohorts of adult smokers in each country using random-digit dialling. The sample size per country was initially around 2000 at each wave, with replenishment sampling from the same sampling frame used to maintain sample size across waves (with a slightly reduced sample from Wave 7, mainly due to budget). At the time of initial recruitment, participants were aged 18+ years, had smoked at least 100 cigarettes lifetime, and had smoked at least once in the past 30 days. Wave 5 survey data (total n = 8242 for four countries) were collected between October 2006 and February 2007; Wave 6 (n = 8193) in late 2007; Wave 7 (n = 7206) in late 2008 and Wave 8 (n = 5939) from July 2010. In this study, only those participants who were current smokers at the time of the survey were included in data analyses. Each country’s analytic sample size at each selected wave (Waves 5–8) and their characteristics are summarized in Table II.

Table II.

Sample characteristics, by country

| Canada | United States | United Kingdom | Australia | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. of current smokers at each selected wavea | |||||

| Wave 5 (in late 2006) | 1741 | 1789 | 1706 | 1801 | 7037 |

| Wave 6 (2007) | 1708 | 1743 | 1643 | 1791 | 6885 |

| Wave 7 (2008) | 1510 | 1518 | 1487 | 1372 | 5887 |

| Wave 8 (2010) | 1243 | 1262 | 977 | 1111 | 4593 |

| Gender (% female) | 53.4 | 54.5 | 55.8 | 53.0 | 54.2 |

| Identified minority group (%) | 11.1 | 20.9 | 4.9 | 12.3 | 12.8 |

| Age at recruitment (%)b | |||||

| 18–24 | 12.5 | 11.2 | 8.5 | 13.8 | 11.5 |

| 25–39 | 30.1 | 25.6 | 31.3 | 35.1 | 30.2 |

| 40–54 | 36.6 | 36.5 | 33.8 | 34.2 | 35.4 |

| 55+ | 20.9 | 26.6 | 26.4 | 16.9 | 22.9 |

| Education at recruitment (%)c | |||||

| Low | 48.5 | 45.6 | 60.6 | 63.5 | 53.8 |

| Moderate | 36.4 | 38.2 | 25.1 | 22.2 | 31.1 |

| High | 14.8 | 16.1 | 13.5 | 14.1 | 14.7 |

| Income at recruitment (%)c | |||||

| Low | 28.1 | 37.0 | 31.1 | 26.7 | 31.1 |

| Moderate | 34.2 | 32.9 | 31.5 | 32.5 | 32.8 |

| High | 29.4 | 23.5 | 27.6 | 34.3 | 28.3 |

| No information | 8.4 | 6.9 | 9.8 | 6.5 | 7.8 |

| CPD at recruitment (%) | |||||

| 1–10 | 31.4 | 31.3 | 29.8 | 29.6 | 30.6 |

| 11–20 | 42.6 | 45.8 | 53.4 | 40.2 | 45.6 |

| 21–30 | 21.0 | 12.9 | 11.7 | 22.8 | 16.8 |

| 31+ | 4.5 | 9.3 | 4.8 | 7.0 | 6.6 |

Percentages were based on unweighted data. For some variables, the numbers of cases were fewer than the total, due to some ‘don’t know’ and ‘missing’ cases. aFor the numbers of new recruits in each wave, please refer to Li et al. (2012) paper [25]. bFor all participants recruited from Wave 1 to Wave 8; and this applies to the other variables in the table. cFor the definition of each category, please see the ‘Measures’ section.

Measures

The ITC-4 Survey was standardized across countries with respondents being asked essentially the same questions, with only minor variations in colloquial speech or usual reference.

Demographics and smoking-related variables

Demographics variables included sex (male, female), age at recruitment (18–24, 25–39, 40–54, 55 and older) and identified majority/minority group, which was based on the primary means of identifying minorities in each country (i.e. racial/ethnic group in the United Kingdom, Canada and the United States; and English language spoken at home in Australia). Due to the differences in economic development and educational systems across the four countries, only relative levels of education and income were used. ‘Low’ level of education referred to those who completed high school or less in Canada, the United States and Australia or secondary/vocational or less in the United Kingdom; ‘moderate’ meant community college/trade/technical school/some university (no degree) in Canada and the United States, college/university (no degree) in the United Kingdom or technical/trade/some university (no degree) in Australia and ‘high’ referred to those who completed university or postgraduate studies in all countries. Household income was also grouped into ‘low’ [<US$30 000 (or £30 000 in the United Kingdom) per year], ‘moderate’ [between US$30 000 and US$59 999 (or £30 000 and £44 999 in the United Kingdom)] and ‘high’ categories [equal to or greater than US$60 000 (or £45 000 in the United Kingdom)].

Cigarettes per day (CPD) was asked at each wave and recoded to: ‘1–10 CPD’, ‘11–20 CPD’, ‘21–30 CPD’ and ‘30+ CPD’.

Measures of exposure to tobacco advertising and promotion

Across the studied waves, participants were asked about the overall salience of pro-smoking cues (unprompted recall) via the following question: ‘In the last 6 months, how often have you noticed things that promote smoking?’ The participants were then prompted to recall if they had noticed advertisements in specific channels (with posters/billboards asked for all four countries), and if they had noticed any types of promotion (gifts/discounts on other products, clothing with cigarettes brand name and competitions linked to cigarettes, for all countries).

Participants were also asked the following specific questions regarding POS tobacco displays and advertising: ‘In the last month, have you seen cigarette packages being displayed, including on shelves or on the counter?’ (question asked from Wave 5 onward); and ‘In the last 6 months, have you noticed cigarettes or tobacco products being advertised on store windows or inside stores where tobacco is sold?’ (question asked at all waves). Response options were ‘yes’, ‘no’ and ‘don’t know’. Those who answered ‘yes’ were regarded as having been exposed to POS tobacco displays/advertising.

Cigarette brands and their purchasing

The participants were asked if they had a regular brand and variety of cigarettes, and if they bought their regular brand at the last purchase. They were also asked (from Wave 6) if in the last 6 months they had ever bought a brand other than their usual brand because they noticed a POS promotion (a tobacco advertisement or a display) for a brand. In addition, from Wave 8, smokers were asked if tobacco displays made them buy unplanned cigarettes.

Data analysis

Country/group differences in the same year (wave) were assessed using logistic regression modeling. Taking into consideration the correlated nature of the data within participants across survey waves, we used the generalized estimating equations (GEEs) approach to compute parameter estimates and assess changes over time (over waves). The GEE modeling included a specification for an unstructured within-subject correlation structure, and parameter estimates were computed using robust variance. All models were controlled for age, sex, education, income and CPD. To facilitate the comparison of prompted recall of tobacco advertising and promotion in various channels, an overall index (‘noticing tobacco advertisements/promotion in any other specific channels’) was computed, in which participants who answered ‘yes noticed’ in any of the following four channels (other than POS) were coded as ‘1’, otherwise coded as ‘0’: posters/billboards, gifts/discounts on other products, clothing with cigarettes brand name and competitions linked to cigarettes. Based on the ‘implementation date’ information in Table I, a ‘display ban status’ variable was computed for all individuals for all the studied waves. A participant’s ‘display ban status’ was coded as ‘1’ (‘yes, with a display ban’) if his/her province/state started to implement a POS tobacco display ban policy before (or on) the date the participant was interviewed, otherwise coded as ‘0’ (‘no display ban’). The differences of tobacco marketing exposure between those with and without a display ban were then compared. All analyses were conducted using Stata Version 12.1.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was approved by the institutional review boards or research ethics boards of the University of Waterloo (Canada), Roswell Park Cancer Institute (the United States), University of Strathclyde (the United Kingdom), University of Stirling (United Kingdom), The Open University (United Kingdom) and The Cancer Council Victoria (Australia).

Results

Exposure to tobacco advertising and promotional activities

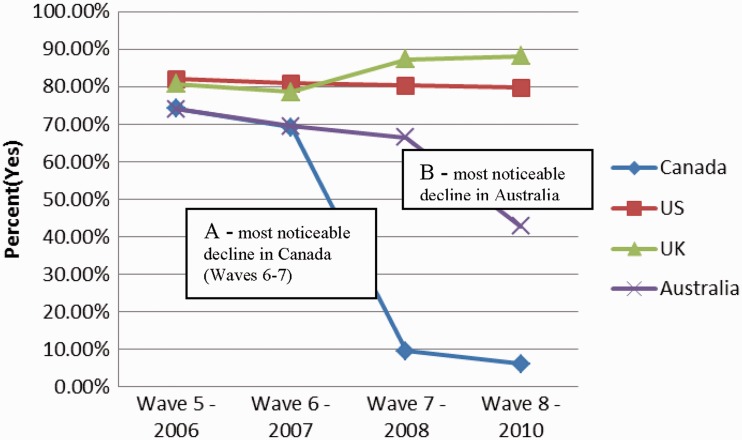

As shown in Table III and Fig. 1, banning POS displays in Canada markedly decreased reported exposure to tobacco marketing at the POS. For example, noticing of POS tobacco displays significantly decreased from 74.1% in Wave 5 to 6.1% in Wave 8 [adjusted odds ratio (AOR) = 0.26, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.24–0.28, P < 0.001, GEE modeling results (see the bottom of Table III), including all four waves’ data]. The most noticeable decline occurred between 2007 (Wave 6) and 2008 (Wave 7) (As indicated in Fig. 1 with note ‘A’) when the most populous Canadian provinces introduced POS display bans. A similar trend was found for POS tobacco advertising exposure (decreased from 40.3% in Wave 5 to 14.1% in Wave 8, AOR = 0.61, P < 0.001).

Table III.

Reported exposure to tobacco advertising and promotional activities over time, by country

| Canada | United States | United Kingdom | Australia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 (Wave 5) | ||||

| Exposed to POS tobacco displays (% yes, na) | 74.10 | 81.99 | 80.77 | 73.94 |

| (n = 1741) | (n = 1788) | (n = 1706) | (n = 1801) | |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI, cross-country comparison in same wave!) | Reference | 1.59 (1.36–1.88)*** | 1.51 (1.29–1.78)*** | 0.99 (0.86–1.16) |

| Exposed to POS tobacco advertising (% yes) | 40.26 | 82.61 | 35.17 | 31.76 |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI, cross-country comparison) | Reference | 7.69 (6.57–9.02)*** | 0.82 (0.71–0.95)** | 0.67 (0.58–0.77)*** |

| Overall salience: noticed things that encourage smoking (% yesb) | 20.91 | 33.72 | 17.64 | 18.71 |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI, cross-country comparison) | Reference | 1.99 (1.71–2.32)*** | 0.81 (0.69–0.96)* | 0.84 (0.71–0.99)* |

| Noticed tobacco advertisements/promotion in any other specific channelsc (% yes) | 46.64 | 82.06 | 39.57 | 33.43 |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI, cross-country comparison) | Reference | 5.54 (4.75–6.47)*** | 0.77 (0.67–0.89)*** | 0.55 (0.49–0.63)*** |

| 2007 (Wave 6) | ||||

| Exposed to POS tobacco displays (% yes, n) | 69.20 | 80.88 | 78.56 | 69.40 |

| (n = 1708) | (n = 1742) | (n = 1642) | (n = 1791) | |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI, cross-country comparison) | Reference | 1.92 (1.64–2.25)*** | 1.67 (1.43–1.96)*** | 1.02 (0.87–1.18) |

| Exposed to POS tobacco advertising (% yes) | 34.45 (1707) | 85.31 | 27.81 | 25.57 |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI, cross-country comparison) | Reference | 12.51 (10.5–14.84)*** | 0.74 (0.63–0.85)*** | 0.62 (0.54–0.72)*** |

| Overall salience (% yes) | 19.37 | 35.28 | 16.14 | 19.54 |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI, cross-country comparison) | Reference | 2.29 (1.95–2.67)*** | 0.76 (0.64–0.92)** | 0.95 (0.81–1.13) |

| Noticed advertisements/promotion in any other channels (%) | 39.87 | 80.34 | 31.22 | 30.93 |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI, cross-country comparison) | Reference | 6.61 (5.67–7.72)*** | 0.69 (0.59–0.79)*** | 0.65 (0.56–0.75)*** |

| 2008 (Wave 7) | ||||

| Exposed to POS tobacco displays (% yes, n) | 9.56 | 80.36 | 87.27 | 66.42 |

| (n = 1506) | (n = 1517) | (n = 1485) | (n = 1370) | |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI, cross-country comparison) | Reference | 40.09 (32.3–49.75)*** | 69.46 (55.1–87.71)*** | 20.25 (16.42–24.98)*** |

| Exposed to POS tobacco advertising (% yes) | 17.65 | 75.68 | — | — |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI, cross-country comparison) | Reference | 15.98 (13.2–19.22)*** | — | — |

| Overall salience (% yes) | 17.12 | 30.78 | 14.74 | 13.49 |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI, cross-country comparison) | Reference | 2.21 (1.86–2.63)*** | 0.82 (0.67–1.01) | 0.74 (0.60–0.91)** |

| Noticed advertisements/promotion in any other channels (%) | 30.13 | 82.02 | 37.19 | 26.02 |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI, cross-country comparison) | Reference | 11.70 (9.83–13.94)*** | 1.43 (1.22–1.66)*** | 0.81 (0.68–0.95)* |

| 2010 (Wave 8) | ||||

| Exposed to POS tobacco displays (% yes, n) | 6.14 | 79.70 | 88.10 | 42.86 |

| (n = 1237) | (n = 1256) | (n = 975) | (n = 1106) | |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI, cross-country comparison) | Reference | 61.69 (46.9–80.99)*** | 117.6 (86.8–159.6)*** | 11.59 (8.91–15.07)*** |

| Exposed to POS tobacco advertising (% yes) | 14.14 (1238) | 71.24 (1255) | — | — |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI, cross-country comparison) | Reference | 16.16 (13.1–19.91)*** | — | — |

| Overall salience (% yes) | 14.63 | 29.86 | 14.05 | 12.30 |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI, cross-country comparison) | Reference | 2.49 (2.04–3.05)*** | 0.95 (0.74–1.20) | 0.82 (0.63–1.04) |

| Noticed advertisements/promotion in any other channels (%) | 30.41 | 77.26 | 37.15 | 24.12 |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI, cross-country comparison) | Reference | 8.38 (6.98–10.06)*** | 1.40 (1.17–1.68)*** | 0.71 (0.59–0.85)*** |

| Over-wave comparison—GEE modeling results (adjusted OR, 95% CI!) (Wave 5 exposure as reference) | ||||

| Exposed to POS tobacco displays | 0.26 (0.24–0.28)*** | 0.96 (0.90–1.02) | 1.24 (1.16–1.32)*** | 0.67 (0.64–0.71)*** |

| Exposed to POS tobacco advertising | 0.61 (0.57–0.64)*** | 0.78 (0.74–0.82)*** | 0.70 (0.62–0.80)*** | 0.74 (0.65–0.84)*** |

| Overall salience | 0.87 (0.82–0.92)*** | 0.92 (0.87–0.97)** | 0.91 (0.85–0.97)** | 0.83 (0.78–0.89)** |

| Noticed advertisements/promotion in any other channels | 0.58 (0.46–0.73)*** | 0.95 (0.90–1.01) | 0.97 (0.92–1.02) | 0.85 (0.82–0.90)*** |

aThe number of valid cases (n) for this measure are slightly fewer than the total number of current smokers at the specific wave in a particular country (e.g. in the United States), and this applies to other specific measures, waves and countries. All odds ratios for cross-country comparison are generated using logistic regression modeling, whereas odds ratios for over-wave comparison are generated with GEE modeling, and adjusted for age, sex, education, income and CPD. bAt least once in a while. cThese specific channels are posters/billboards, gifts/discounts on other products, clothing with cigarettes brand name and competitions linked to cigarettes. ‘—’ The question was not asked in the United Kingdom and Australia at Waves 7 and 8, respectively. Significant at *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Fig. 1.

Noticing POS tobacco displays over time.

Similarly, in Australia, we can see a significant decline in reported exposure to tobacco displays [especially between 2008 and 2010 (Waves 7 and 8) when some Australian states started to implement a POS display ban, as indicated in Fig. 1 with note ‘B’]. The percentages of noticing POS displays decreased from 73.9% in Wave 5 to 42.9% in Wave 8 (AOR = 0.67, P < 0.001).

In contrast, exposure to POS marketing in the United States and United Kingdom remained constantly high (or even with some increase) over studied waves (e.g. for over-wave comparison of exposure to POS tobacco displays in the United States, AOR = 0.96, P = 0.11; and in the United Kingdom, an overall increase in reported exposure to POS displays was observed: AOR = 1.24, P < 0.001, Table III).

We further explored whether POS display bans translated into an overall decrease in exposure to tobacco promotional activities (beyond the POS). As can be seen from Table III, in all the waves, comparatively higher proportions of US smokers reported having noticed things that encourage smoking (overall salience); over waves, there is a decrease in overall salience of tobacco promotional activities in Canada (declined from 20.9% in Wave 5 to 14.6% in Wave 8, AOR = 0.87, P < 0.001). There are also some decreases in the other countries, but they are not as consistent/considerable as in Canada. When exposures to any other (other than POS) specific advertising/promotional sources (e.g. posters/billboards, gifts/discounts on other products) were assessed, significant over-wave declines were found only in Canada (AOR = 0.58, P < 0.001) and Australia (AOR = 0.85, P < 0.001) (Table III).

Cigarette purchasing behaviors

As shown in Table IV, across all four countries for all studied waves the vast majority of smokers reported that they had a regular brand of cigarettes and bought their regular brands in last purchase. Compared with the other three countries, Canada had few smokers reporting having had a regular brand and bought it last time.

Table IV.

Reported cigarette purchasing behaviors over time, by country

| Canada | United States | United Kingdom | Australia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2006 (Wave 5) | ||||

| Had a regular brand and bought it last time (% yes, na) | 83.50 | 88.27 | 88.15 | 88.15 |

| (n = 1739) | (n = 1782) | (n = 1705) | (n = 1797) | |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI, cross-country comparison in same wave!) | Reference | 1.46 (1.21–1.77)*** | 1.45 (1.19–1.76)*** | 1.49 (1.23–1.81)*** |

| 2007 (Wave 6) | ||||

| Had a regular brand and bought it last time (% yes, n) | 79.95 | 84.64 | 89.89 | 87.76 |

| (n = 1616) | (n = 1680) | (n = 1592) | (n = 1708) | |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI, cross-country comparison) | Reference | 1.37 (1.14–1.64)** | 2.24 (1.82–2.74)*** | 1.84 (1.52–2.22)*** |

| Bought non-usual brand because of displays/advertising(% yes, nb) | 11.0 | 23.9 | 8.59 | 5.28 |

| (n = 818) | (n = 792) | (n = 908) | (n = 834) | |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI, cross-country comparison) | Reference | 2.64 (2.00–3.49)*** | 0.77 (0.56–1.06) | 0.43 (0.29–0.63)*** |

| 2008 (Wave 7) | ||||

| Had a regular brand and bought it last time (% yes, n) | 82.67 | 87.30 | 87.01 | 91.08 |

| (n = 1496) | (n = 1512) | (n = 1478) | (n = 1368) | |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI, cross-country comparison) | Reference | 1.43 (1.17–1.76)** | 1.40 (1.14–1.72)** | 2.17 (1.72–2.74)*** |

| Bought non-usual brand because of displays/advertising (% yes, n) | 4.84 | 16.40 | 7.35 | 2.82 |

| (n = 888) | (n = 756) | (n = 898) | (n = 673) | |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI, cross-country comparison) | Reference | 4.05 (2.82–5.84)*** | 1.59 (1.07–2.37)* | 0.55 (0.32–0.95)* |

| 2010 (Wave 8) | ||||

| Had a regular brand and bought it last time (% yes, n) | 84.52 | 85.77 | 87.45 | 89.37 |

| (n = 1227) | (n = 1251) | (n = 972) | (n = 1101) | |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI, cross-country comparison) | Reference | 1.11 (0.89–1.38) | 1.27 (0.99–1.62) | 1.54 (1.20–1.97)** |

| Bought non-usual brand because of displays/advertising (% yes, n) | 4.26 | 17.44 | 6.96 | 3.26 |

| (n = 657) | (n = 579) | (n = 546) | (n = 552) | |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI, cross-country comparison) | Reference | 4.99 (3.22–7.49)*** | 1.72 (1.04–2.86)* | 0.75 (0.41–1.37) |

| Bought unplanned cigarettes due to display (% yes, n) | 2.43 | 7.09 | 5.85 | 3.98 |

| (n = 1237) | (n = 1256) | (n = 975) | (n = 1105) | |

| Adjusted OR (95% CI, cross-country comparison) | Reference | 3.26 (2.13–4.99)*** | 2.49 (1.58–3.91)*** | 1.54 (0.96–2.49) |

| Over-wave comparison—GEE modeling results (adjusted OR, 95% CI!) | ||||

| Had a regular brand and bought it last time (Wave 5 as reference) | 1.04 (0.98–1.11) | 0.98 (0.91–1.04) | 0.95 (0.88–1.02) | 1.09 (1.01–1.17)* |

| Bought non-usual brand because of displays/advertising (Wave 6 as reference) | 0.58 (0.46–0.73)*** | 0.79 (0.68–0.90)** | 0.89 (0.73–1.08) | 0.71 (0.53–0.95)* |

aThe number of valid cases (n) for this measure is smaller than the total number of current smokers at this wave in Canada, and this applies to the other measure, waves and countries. Out of the valid cases, we reported the percentage of respondents who had a regular brand and bought it last time. All odds ratios for cross-country comparison are generated using logistic regression modeling, whereas odds ratios for over-wave comparison are generated with GEE modeling, and adjusted for age, sex, education, income and CPD. bThis question was only asked from Wave 6. Significant at *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

The proportions of buying non-usual brand cigarettes because of noticing tobacco displays/advertising were generally low (<11%) in Australia, Canada and the United Kingdom between Waves 6 and 8 (this question was only asked from Wave 6), and a trend of significant decline can be seen in Canada (AOR = 0.58, P < 0.001) and Australia (AOR = 0.71, P < 0.05), but no significant change was found in the United Kingdom (AOR = 0.89, P = 0.24). The United States had the highest levels of buying non-usual brands because of noticing tobacco advertising/displays. Although there is a trend of decline (from 23.9% in Wave 6 to 16.4% in Wave 7), the reported level was still as high as 17.4% in Wave 8.

Participants were asked in Wave 8 if cigarettes display led them to buy unplanned cigarettes. The results show that compared with smokers in Canada, smokers in the United States (AOR = 3.26, P < 0.001) and United Kingdom (AOR = 2.49, P < 0.001) were more likely to buy unplanned cigarettes because of exposure to cigarette displays (Table IV).

Differences in exposure between smokers with and without a point-of-sale tobacco display ban

Based on the ‘display ban status’ of participants (regardless which country they were from), we conducted GEE modeling to compare tobacco marketing exposure levels of those with and without a POS tobacco display ban (for Waves 7 and 8 only, because the sample size of the group ‘with a display ban’ is too small in earlier waves). As can be seen in Table V, in both Waves 7 and 8, those smokers who were covered by a POS display ban were less likely to be exposed to POS tobacco displays or advertising/promotional activities in the other specific channels, had a lower level of overall salience of tobacco marketing, and were less likely to purchase non-usual brand of cigarettes (or buy unplanned cigarettes in Wave 8) because of exposure to tobacco displays/advertising.

Table V.

Differences in exposure between smokers with a POS tobacco display ban and those without a ban (all four countries)

| 2008 (Wave 7) |

2010 (Wave 8) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 5887a) |

(n = 4593) |

|||||

| No display ban | With a display ban | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | No display ban | With a display ban | Adjusted OR (95% CI) | |

| % exposed to POS tobacco displays | 77.21 | 6.83 | 0.02 (0.01–0.03)*** | 77.81 | 9.09 | 0.03 (0.02–0.04)*** |

| % noticed things that encourage smokingb (overall salience) | 19.79 | 17.27 | 0.85 (0.72–0.99)* | 20.19 | 14.53 | 0.68 (0.57–0.79)*** |

| % noticed tobacco advertisements/promotion in any other specific channelsc | 48.76 | 29.91 | 0.43 (0.38–0.49)*** | 51.84 | 28.21 | 0.35 (0.31–0.40)*** |

| % bought non-usual brand because of displays/advertisingd | 8.91 | 4.67 | 0.49 (0.34–0.70)*** | 10.30 | 3.99 | 0.35 (0.24–0.52)*** |

| % bought unplanned cigarettes due to display | — | — | — | 6.13 | 2.52 | 0.39 (0.27–0.54)*** |

aThe number of valid cases (n) for different measures are slightly different and smaller than the total number of current smokers at the wave due to some ‘don’t know’ and ‘missing’ cases, and this applies to Wave 8. ‘No display ban’ group as reference; all odds ratios are generated using logistic regression, and adjusted for age, sex, education, income and CPD. bAt least once in a while. cThese specific channels are posters/billboards, gifts/discounts on other products, clothing with cigarettes brand name and competitions linked to cigarettes. dThis measure only includes those who were asked of this question (n = 3215 at Wave 7; n = 2334 at Wave 8). ‘—’ The question was not asked in the United Kingdom and Australia at Waves 7. Significant at *P < 0.05; **P < 0.01; ***P < 0.001.

Discussion

In jurisdictions where POS display bans were implemented such as in Canada and some states of Australia reported exposure to tobacco marketing by adult smokers declined markedly. In contrast, in the United States and United Kingdom where there were no such restrictions during the study period, reported exposure to POS tobacco displays and other forms of marketing remained high and relatively stable (especially in the United States). Our data also suggest that impulse purchasing of cigarettes was lower in places that enacted POS display bans.

The reported reduction in exposure to tobacco marketing associated with the POS display bans were detected soon after the bans were implemented. For example, in Canada, some of the most populous provinces (i.e. Alberta, British Columbia, Ontario and Quebec, together accounting for more than 80% of the population of the country) introduced and started implementing display bans between Waves 6 and 7 (between 2007 and 2008), and a marked decline of reported exposure to POS tobacco displays/advertising was detectable in Wave 7. Similarly, in Australia, some states/territories started to implement display bans before/during Wave 8 (2010/11) and their effects on reported display exposure began to show when the smokers were surveyed in Wave 8, although Australia showed a weaker downward trend when compared with Canada. This may be because a lower proportion of the Australian population (about a third) was exposed to the ban at the time of the survey. Whereas in the other two countries (the United States and United Kingdom), no such display bans had been implemented during the study period, and no significant changes in reported exposure to POS tobacco displays were detected (and this applied to exposures to promotional activities in other specific channels).

Our results clearly show that on top of POS tobacco display bans reducing reported exposure to tobacco marketing among smokers, they show that these bans were associated with lowered reports of impulse purchasing (both buying non-usual brands and unplanned cigarettes as a result of seeing the POS cigarette display). This is an important finding as it complements research showing that POS tobacco marketing stimulates impulse cigarette purchases, encourages tobacco use and undermines the efforts of those trying to quit [1, 4–10]. It is clear that advertising acts as a cue to use tobacco, and removing cues leads to a reduction in use-associated activities. These findings provide evidence of the effectiveness of prohibiting POS displays as an effective tobacco control strategy, and make it plausible that the bans contributed to the declines in smoking found in Canada [17, 19] and Iceland [18] following their implementation.

This study has limitations. In some jurisdictions, such as New South Wales and Australian Capital Territory, POS display bans were only introduced/implemented very recently (around Wave 8), so only the initial impact could be examined. The medium/long-term impact of the POS display bans in these jurisdictions (especially on smokers’ quitting behaviors) needs to be evaluated in subsequent waves of the ITC-4 Survey.

In addition, there are features of the POS measures employed that led to lower reliability. For example, the use of self-report measures over a recall period of 6 months. It should be noted, however, that these measures did change over time as predicted, despite the lower reliability. The same can be said of other challenges to measurement and to statistical power, such as the smaller sample sizes at Waves 7 and 8, especially for the United Kingdom (in Wave 8 no replenishment smokers were recruited there). Hence, the measurement challenges did not interfere with our ability to detect the impact of POS display bans. Exposure to POS tobacco advertising is a relevant measure in this study, but this question was not asked in Australia or in the United Kingdom for Waves 7 and 8, and this to some extent limited our ability to conduct more systematic and longer term cross-country comparisons for this variable. Finally, we think it unlikely the key findings are affected by levels of other forms of tobacco advertising, as these levels are low in the United Kingdom, although by far the highest in the United States, and neither country showed the effects we attribute to POS bans.

In spite of its limitations, this study (with its prospective multi-country cohort design), allowed for changes in tobacco marketing exposure and cigarette purchasing behaviors over time to be assessed, and cross-country variations in different jurisdictions with various levels of POS regulations to be compared.

The findings of this study indicate that implementing POS tobacco display bans (as has been done in Canada and Australia) reduces exposure to tobacco marketing and lowers reported impulse purchasing of cigarettes.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank other members of the ITC Four Country Survey team for their support. Our special thanks go to Dr Hua-Hie Yong for his useful suggestions in data analysis and assistance in obtaining some information regarding the POS display ban implementation dates in Australia.

Funding

The National Cancer Institute at the National Institutes of Health of the United States (P50 CA111326, P01 CA138389 and R01 CA100362); Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (045734); Canadian Institutes of Health Research (57897, 79551 and 115016); National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia (265903 and 450110); Cancer Research United Kingdom (C312/A3726); Canadian Tobacco Control Research Initiative (014578) and the Ontario Institute for Cancer Research, with additional support from the Propel Centre for Population Health Impact, Canadian Cancer Society and a Prevention Scientist Award from the Canadian Cancer Society Research Institute. The funding sources had no role in the study design, in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data, in the writing of the manuscript, nor in the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of interest statement

None declared.

References

- 1.Carter OBJ, Mills BW, Donovan RJ. The effect of retail cigarette pack displays on unplanned purchases: results from immediate post-purchase interviews. Tob Control. 2009;18:218–21. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.027870. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Paynter J, Edwards R, Schluter P, et al. Point of sale tobacco displays and smoking among 14–15 years olds in New Zealand: a cross-sectional study. Tob Control. 2009;18:268–74. doi: 10.1136/tc.2008.027482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wakefield M, Germain D, Durkin S, et al. An experimental study of effects on schoolchildren of exposure to point-of-sale cigarette advertising and pack displays. Health Educ Res. 2006;21:338–47. doi: 10.1093/her/cyl005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Henriksen L, Flora J, Feighery E, et al. Effects on youth of exposure to retail tobacco advertising. J Appl Soc Psychol. 2002;32:1771–89. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wakefield M, Germain D, Henriksen L. The effect of retail cigarette pack displays on impulse purchase. Addiciton. 2008;103:322–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2007.02062.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lovato C, Linn G, Stead LF, et al. Impact of tobacco advertising and promotion on increasing adolescent smoking behaviours. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2003;4:CD003439. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Paynter J, Edwards R. The impact of tobacco promotion at the point of sale: a systematic review. Nicotine Tob Res. 2009;11:25–35. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntn002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Germain D, McCarthy M, Wakefield M. Smoker sensitivity to retail tobacco displays and quitting: a cohort study. Addiciton. 2009;105:159–63. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02714.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pollay R. More than meets the eye: on the importance of retail cigarette merchandising. Tob Control. 2007;16:270–4. doi: 10.1136/tc.2006.018978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mackintosh AM, Moodie C, Hastings G. The association between point-of-sale displays and youth smoking susceptibility. Nicotine Tob Res. 2012;14:616–20. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntr185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Henriksen L. Comprehensive tobacco marketing restrictions: promotion, packaging, price and place. Tob Control. 2012;21:147–53. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Action on Smoking and Health. Tobacco Displays at the Point of Sale. Available at: http://www.smokefreeaction.org.uk/files/docs/PoSD.pdf. 2010. Accessed: 5 September 2012.

- 13.McNeil A, Lewis S, Quinn C, et al. Evaluation of the removal of point-of-sale tobacco displays in Ireland. Tob Control. 2011;20:137–43. doi: 10.1136/tc.2010.038141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kickling J, Miller C. Cigarette pack and advertising displays at point of purchase: community demand for restrictions. Int J Consum Stud. 2008;32:574–8. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brown A, Boudreau C, Moodie C, et al. Support for removal of point-of-purchase tobacco advertising and displays: findings from the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Canada survey. Tob Control. 2012;21:555–559. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2011-050153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cancer Research UK. Press Release: huge public support to remove cigarette vending machines and tobacco displays in shops. 25 July 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Canadian Tobacco Use Monitoring Survey. Health Canada, 2011. Available at: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hc-ps/tobac-tabac/research-recherche/stat/ctums-esutc_2011-eng.php. Accessed: 29 August 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 18.How many Icelanders smoke? Statistics Iceland. Available at: http://www.statice.is/Pages/2004. Accessed: 15 February 2013.

- 19.Health Canada. Canadian Tobacco Use Monitoring Survey 2007. Available at: http://www.hc-sc.gc.ca/hl-vs/tobac-tabac/research-recherche/stat/ctums-esutc_2007-eng.php. Accessed: 2 September 2012.

- 20.The Centre for Tobacco Control Research, University of Stirling. Point of Sale Display of Tobacco Products. 2008. Available at: http://info.cancerresearchuk.org/prod_consump/groups/cr_common/@nre/@pol/documents/generalcontent/crukmig_1000ast-3338.pdf. Accessed: 2 September 2012.

- 21.ASH Scotland. Evidence for Youth Smoking Prevention Measures. 2011. Available at: http://www.ashscotland.org.uk/media/3929/Evidence_base_for_smoking_prevention_measures_May2011.pdf. Accessed: 3 September 2012.

- 22.The Department of Health (of UK) Healthy Lives, Healthy People: A Tobacco Control Plan for England. 2011. Available at: http://www.dh.gov.uk/prod_consum_dh/groups/dh_digitalassets/documents/digitalasset/dh_124960.pdf. Accessed: 16 September 2012.

- 23.Fong GT, Cummings KM, Borland R, et al. The conceptual framework of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Policy Evaluation Project. Tob Control. 2006;15(Suppl. 3):iii3–11. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.015438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thompson ME, Fong GT, Hammond D, et al. Methods of the International Tobacco Control (ITC) Four Country Survey. Tob Control. 2006;15(Suppl. 3):iii12–8. doi: 10.1136/tc.2005.013870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li L, Borland R, Yong H, et al. The association between exposure to point-of-sale anti-smoking warnings and smokers' interest in quitting and quit attempts: findings from the International Tobacco Control Four Country Survey. Addiction. 2012;107:425–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03668.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]