Abstract

Background

Antibody response to the inactivated influenza vaccine is not well described in kidney transplant recipients on newer, but commonly used, immunosuppression medications. We hypothesized that kidney transplant recipient participants on tacrolimus-based regimens would have decreased antibody response compared with healthy controls.

Study Design

Prospective cohort study of 53 kidney transplant recipient and 106 healthy control participants over the 2006–2007 influenza season. All participants received standard inactivated influenza vaccine.

Setting and participants

Kidney transplant recipients on tacrolimus-based regimens at a single academic medical center and healthy controls.

Predictor

Presence of kidney transplant.

Outcomes

Proportion of participants achieving seroresponse (four-fold rise in antibody titer) and seroprotection (antibody titer greater than 1:32) one month after vaccination.

Measurements

Antibody titers before vaccination and one month after vaccination using hemagglutinin inhibition assays for influenza types A/H1N1, A/H3N2, and B.

Results

A smaller proportion of the transplantation group compared with the healthy control group developed the primary outcomes of seroresponse or seroprotection for all three influenza types at one month post vaccination. The response to influenza type A/H3N2 was statistically different, with the transplantation group having 69% decreased odds of developing seroresponse (95% CI 0.16 to 0.62, P = 0.001) and 78% decreased odds of developing seroprotection (95% CI 0.09 to 0.53, P = 0.001) compared with healthy controls. When participants less than 6 months from time of transplantation were considered, this group had significantly decreased response to the vaccine as compared with healthy controls.

Limitations

Decreased sample size; potential for confounders; outcome measure used is the standard but does not give information about vaccine efficacy.

Conclusions

Kidney transplant recipients, especially within 6 months of transplantation, had diminished antibody response to the 2006–07 inactivated influenza vaccine.

Keywords: influenza, vaccination, immunosuppression, kidney transplant, tacrolimus

Introduction

Solid organ transplantation has become increasingly successful with improved immunosuppression therapy, but infection remains a major therapeutic complication. Of increasing recognition are respiratory viral pathogens, which are the most common cause of community-acquired infection in this population.1 Influenza viruses cause an acute, febrile respiratory illness that can result in more complicated illness in immunosuppressed individuals. In contrast to other respiratory viruses, effective vaccines against influenza exist and work by invoking an antibody response, primarily against the envelope glycoprotein hemagglutinin.2

Kidney transplant recipients are chronically immunosuppressed due to the medications used to prevent rejection of their allografts. Though the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends that kidney transplant recipients receive influenza vaccination,3 their response to the vaccine and its overall effectiveness are not well described. Results from previous studies in this area often conflict, lack adequate power, and depend upon immunosuppression regimens no longer commonly used.4–11 In particular, no study has specifically considered tacrolimus even though it is the basis of the most widely used regimens for kidney transplantation today.12

We conducted a prospective cohort study to compare the influenza vaccine-induced antibody response in kidney transplant recipients on tacrolimus-based regimens to the response seen in healthy control participants. We hypothesized that kidney transplant recipients on tacrolimus-based regimens would have decreased antibody responses compared with healthy control individuals.

Methods

Study Design

The Institutional Review Board of Vanderbilt University Medical Center (VUMC) approved this project and informed consent was obtained from all study participants. We conducted a prospective cohort study of kidney transplant recipients and healthy controls at VUMC to compare the antibody response to the trivalent, inactivated, intramuscularly administered influenza vaccine in kidney transplant recipients on a tacrolimus-based immunosuppression regimen to that of healthy control participants. Kidney transplant recipients were recruited from the VUMC Renal Transplant Clinic during October and November 2006 based on the following inclusion criteria: aged 18 to 69 years, taking a tacrolimus-based immunosuppression regimen, and being greater than thirty days from the transplantation procedure. Healthy controls aged 18 to 69 years were recruited during the same time period. Controls included family members of enrolled transplant recipients and individuals from the VUMC community. No matching of transplant recipient and control participants was done. Exclusion criteria for both groups included previous receipt of the 2006–2007 influenza vaccine, known anaphylactic reactions to eggs or prior influenza vaccine, or presence of moderate to severe acute febrile illness in the week prior to enrollment.

Enrolled participants participated in two study visits. The first visit consisted of data and serum collection, and administration of inactivated influenza vaccine. A data collection form was completed for each participant using self-reported medical history. Confirmation of data was provided through the VUMC electronic medical record. Information obtained included basic demographic data, previous influenza vaccine exposure, and for transplant recipients, the date of transplantation, induction agent and maintenance immunosuppressive regimen, and donor source. Serum was collected to measure baseline influenza antibody titer and serum creatinine. Each transplant recipient and control participant was then administered the 2006–2007 trivalent inactivated intramuscular influenza vaccine (Fluvirin; manufactured by Chiron Vaccines Limited, Liverpool UK, Lot # 69480, expiration 6/30/2007) given as a single 0.5 ml dose into the deltoid muscle. The 2006–2007 influenza vaccine contained 15 µg hemagglutinin each of A/New Caledonia/20/99 (H1N1), A/Wisconsin/67/2005 (H3N2), and B/Malaysia/2506/2004 viruses. The second visit occurred one month later, with serum collected to measure post vaccination influenza antibody titer and serum creatinine. Participants were given contact information to report any adverse reactions related to vaccination or study visits. Antibody response to the vaccine was measured by checking anti-hemagglutinin antibody levels in each participant’s serum using the hemagglutinin inhibition (HI) test and reporting the result as a geometric mean titer.13 The primary endpoints were seroresponse, defined as a four-fold rise in antibody titer from baseline, and seroprotection, defined as antibody titer of 1:32 or greater, representing the 50% protective threshold.14–17 The secondary outcomes included associations of antibody response with sex, age, immunosuppression, time from transplantation, and kidney function. Kidney function was reported as serum creatinine in mg/dL or as estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) using the 4-variable MDRD Study equation.18

Laboratory Methods

Serum was processed for serum urea nitrogen and creatinine measurements on the day of obtainment by the Vanderbilt Clinical Research Center core laboratory. Another 3 to 5 mL of serum was aliquoted and frozen at −80° Celsius until being tested for antibody response at VUMC Division of Pediatric Infectious Diseases Research Laboratory. Prior to HI testing, all serum samples were treated with receptor-destroying enzyme (RDE II “Seiken”; Denka Seiken Co., LTD., Tokyo, Japan) with 3 parts RDE to 1 part serum and incubated at 37° Celsius for 18–20 hours. Phosphate buffered saline (PBS) was added to each sample for a final serum dilution of 1:8 followed by incubation at 56° Celsius for one hour. HI testing was performed as previously described.19 All samples were tested in duplicate using the 2006–07 WHO influenza reagent kit from the CDC (Atlanta, GA) with Turkey red blood cells (CBT Farms, Chestertown, Maryland).

Sample Size

Our sample size calculation was designed to test the null hypothesis that antibody response to the standard inactivated influenza vaccine one month post influenza vaccination in kidney transplant recipients on a tacrolimus-based immunosuppression regimen is not statistically different from the response in healthy control participants. Based on previous studies, we considered a 20% difference in seroresponse and seroprotection between the two groups to be clinically significant. With our dichotomous outcome variable, we used the chi-square test with a two-sided significance α of 0.05 and 80% power, estimating seroprotection response to be 80% in the healthy control group and 60% in the kidney transplant recipient group, finding we needed 81 patients per group. Given the possibility it may be easier to enroll healthy controls than transplant recipients meeting inclusion criteria over the defined enrollment period, we calculated if we were to enroll twice as many controls as cases, we would need 118 controls and 59 transplant recipient participants. Calculations were made using PS software, version 2.1.31.

Statistical Analysis

Baseline categorical variables were summarized with two proportions testing using the chi-square or Fisher’s exact tests. Continuous baseline characteristics were evaluated for normality of distribution. If values had normal distribution Student’s t test was used; alternatively, Mann-Whitney U test was used for continuous variables with nonnormal distribution. The Wilcoxon signed-rank test was used for paired data. The primary endpoint was the dichotomous outcome variable of the proportion of patients achieving seroresponse or seroprotection at one month post vaccination. For univariate analysis, the chi-square test was used to detect differences in proportions for control and exposure groups. Binary logistic regression was used to obtain adjusted odds ratios. For multivariate analysis, logistic regression modeling was used to explain the relationship between the outcome and independent variables obtained during baseline assessment and to control for confounding. Participants with only one study visit were excluded from final analysis of the primary outcome since data from two time points was needed to make this assessment. Statistical analyses were performed with the statistical software SPSS (version 16.0, SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) and R (www.r-project.org).

Results

Baseline characteristics

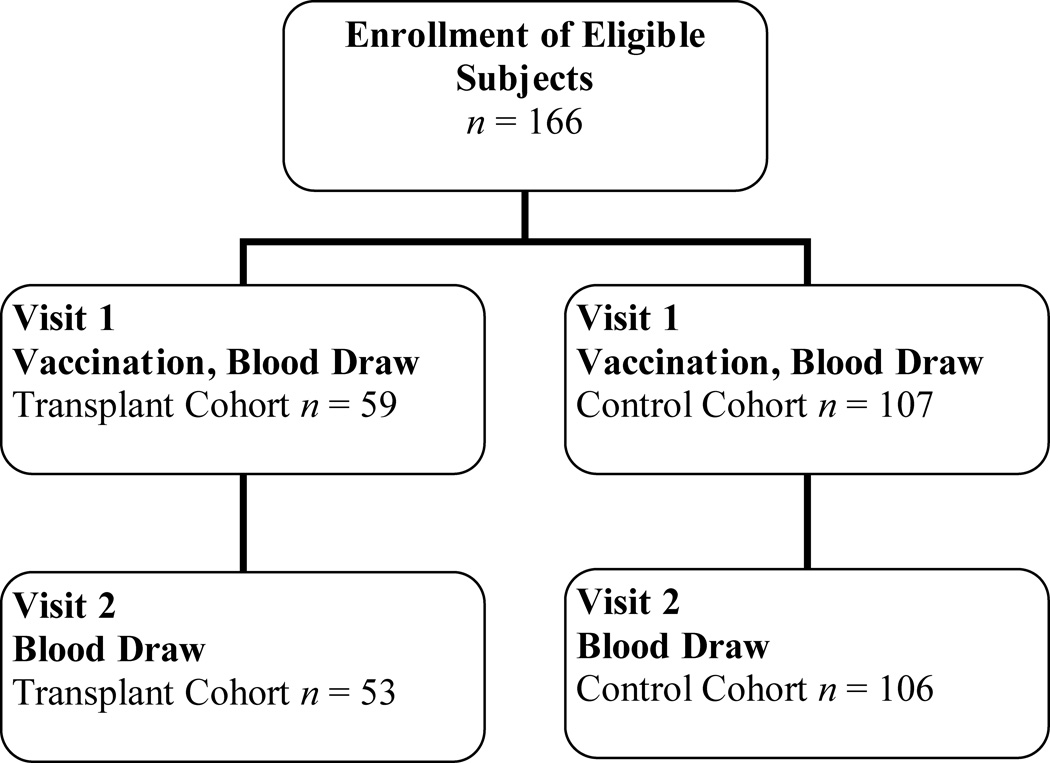

A total of 107 healthy control individuals and 59 kidney transplant recipients were enrolled in the study during October and November 2006; of these, 106 control and 53 transplant recipient participants completed the second follow up visit (99% and 90%, respectively, Figure 1). No difference in the ages of the two groups were seen (control mean age 41.0 ± 12 years, transplant recipients mean age 44.0 ± 10.3 years). Other demographics did vary, with more women in the healthy control group and more African-Americans in the transplant recipient group. As expected, measures of kidney function were significantly different for the two groups (P < 0.001). Both groups had similar high rates of reported influenza vaccination in prior years. Baseline seroprotection, represented as a titer of greater than or equal to 1:32 prior to receiving the influenza vaccination, was noted in 45% or greater of both groups for all three influenza types (Table 1).

Figure 1.

Study enrollment and follow up.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 159 participants.

| Controls (n = 106) |

Transplant Recipients (n = 53) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 41.0 ± 12.1 | 44.0 ± 10.3 | 0.1 |

| Women | 72 (67.9) | 20 (37.7) | <0.001 |

| Race* | 0.003 | ||

| White | 92 (86.8) | 42 (79.2) | |

| Black | 4 (3.8) | 10 (18.9) | |

| Asian | 8 (7.5) | 0 (0) | |

| American Indian or Alaskan native | 2 (1.9) | 1 (1.9) | |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl) | 0.9 ± 0.2 | 1.5 ± 0.6 | <0.001 |

| Glomerular filtration rate (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 85.1 ± 17.4 | 59.8 ± 19.7 | <0.001 |

| Previous influenza vaccination‡ | 89 (84.0) | 50 (94.3) | 0.2 |

| Baseline seroprotection§ | |||

| A/H1N1 | 58 (54.7) | 32 (60.4) | 0.5 |

| A/H3N2 | 70 (66.0) | 24 (45.3) | 0.01 |

| B | 62 (58.5) | 33 (62.3) | 0.7 |

Note: Values expressed as mean ± SD or number (percent).

Race was self-reported.

Conversion factors for units: serum creatinine in mg/dL to µmol/L, x88.4; eGFR in mL/min/1.73 m^2 to mL/s/1.73 m^2, x0.01667.

Previous influenza vaccination was self-reported.

Seroprotection defined as antibody titer ≥ 1:32.

As shown in Table 2, diabetes mellitus was the most common cause of end stage renal disease (26.4%) in the transplant recipient participants, and about half had a cadaveric donor source. Median time since transplantation was 307 days (interquartile range 103.5 to 837 days). Following study design, all participants were on tacrolimus-based regimens with two-thirds of participants on either tacrolimus/ mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) or tacrolimus/ MMF/ prednisone protocols. About 30% of participants were on anti-viral prophylaxis, reflecting a significant portion of participants in the early posttransplantation period.

Table 2.

Characteristics of the transplant recipient group.

| Total (n = 53) |

Tx < 6 months (n = 19) |

Tx > 6 months (n= 34) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (y) | 44.0 ± 10.3 | 46.4 ± 9.3 | 42.7 ± 10.7 | 0.3 |

| Women | 20 (37.7) | 8 (42.1) | 12 (35.3) | 0.6 |

| Race* | 0.7 | |||

| White | 42 (79.2) | 15 (78.9) | 27 (79.4) | |

| Black | 10 (18.9) | 4 (21.1) | 6 (17.6) | |

| Asian | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | |

| American Indian or Alaskan native | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.9) | |

| Serum creatinine (mg/dl)† | 1.5 ± 0.6 | 1.4 ± 0.6 | 1.5 ± 0.7 | 0.4 |

| Glomerular filtration rate (mL/min/1.73 m2) | 59.8 ± 19.7 | 61.8 ± 18.8 | 58.6 ± 20.3 | 0.9 |

| Previous influenza vaccination‡ | 50 (94.3) | 18 (94.7) | 32 (94.1) | 0.9 |

| Baseline seroprotection§ | ||||

| A/H1N1 | 32 (60.4) | 11 (57.9) | 21 (61.8) | 0.8 |

| A/H3N2 | 24 (45.3) | 8 (42.1) | 16 (47.1) | 0.7 |

| B | 33 (62.3) | 12 (63.2) | 21 (61.8) | 0.9 |

| Type of transplant | 0.2 | |||

| Cadaveric | 27 (50.9) | 12 (63.2) | 15 (44.1) | |

| Living | 26 (49.1) | 7 (36.8) | 19 (55.9) | |

| Time since transplantation (d) | 307 (104–837) | 70 (36–177) | 650 (312–1137) | <0.001 |

| Cause of kidney failure | 0.2 | |||

| Diabetes | 14 (26.4) | 7 (36.8) | 7 (20.6) | |

| Glomerulonephritis | 12 (22.6) | 3 (15.8) | 9 (26.5) | |

| Polycystic kidney disease | 10 (18.9) | 6 (31.6) | 4 (11.8) | |

| Hypertension | 9 (17.0) | 2 (10.5) | 7 (20.6) | |

| Obstruction | 5 (9.4) | 0 (0) | 5 (14.7) | |

| Other/unknown | 3 (5.7) | 1 (5.3) | 2 (5.8) | |

| First transplant | 47 (88.7) | 17 (89.5) | 30 (88.2) | 0.9 |

| Prior rejection episode | 8 (15.1) | 0 (0) | 8 (23.5) | 0.02 |

| Induction agent | 0.3 | |||

| Anti-thymocyte antiglobulin | 33 (62.3) | 14 (73.7) | 19 (55.9) | |

| Basiliximab | 12 (22.6) | 4 (21.0) | 8 (23.5) | |

| Alemtuzumab | 3 (5.7) | 1 (5.3) | 2 (5.9) | |

| Other | 5 (9.4) | 0 (0) | 5 (14.7) | |

| Immunosuppression regimen | <0.001 | |||

| Tacrolimus/ MMF | 18 (34.0) | 15 (78.9) | 3 (8.8) | |

| Tacrolimus/ MMF/ prednisone | 17 (32.1) | 2 (10.5) | 15 (44.1) | |

| Tacrolimus/ MPA | 4 (7.5) | 1 (5.3) | 3 (8.8) | |

| Tacrolimus/ MPA/ prednisone | 6 (11.3) | 1 (5.3) | 5 (14.7) | |

| Tacrolimus/ prednisone | 1 (1.9) | 0 (0) | 1 (2.9) | |

| Other | ||||

| Tacrolimus total daily dose (mg) | 5.7 ± 3.1 | 5.5 ± 2.2 | 5.9 ± 3.6 | 0.9 |

| Tacrolimus trough level (ng/mL) | 6.9 ± 2.1 | 7.4 ± 1.9 | 6.6 ± 2.1 | 0.1 |

| Prednisone use | 30 (56.6) | 3 (15.8) | 27 (79.4) | <0.001 |

| MMF/MPA use | 44 (83) | 19 (100) | 25 (73.5) | 0.01 |

| MMF total daily dose (mg)* | 1600 ± 497 | 1765 ± 437 | 1444 ± 511 | 0.6 |

| MPA total daily dose (mg)† | 1008 ± 372 | 1080 ± 509 | 990 ± 373 | 0.8 |

| Antiviral prophylaxis | 16 (30.2) | 13 (68.4) | 3 (8.8) | <0.001 |

Note: Values expressed as mean ± SD, median (25th – 75th percentiles), or number (percent). P refers to comparison between those transplanted < 6 months and > 6 months. Abbreviations: Tx, transplanted; MMF, mycophenolate mofetil; MPA, mycophenolic acid. Conversion factors for units: serum creatinine in mg/dL to µmol/L, x88.4; eGFR in mL/min/1.73 m^2 to mL/s/1.73 m^2, x0.01667.

35 participants on MMF, 17 Tx < 6 months and 18 Tx > 6 months

10 participants on MPA, 2 Tx < 6 months and 8 Tx > 6 months

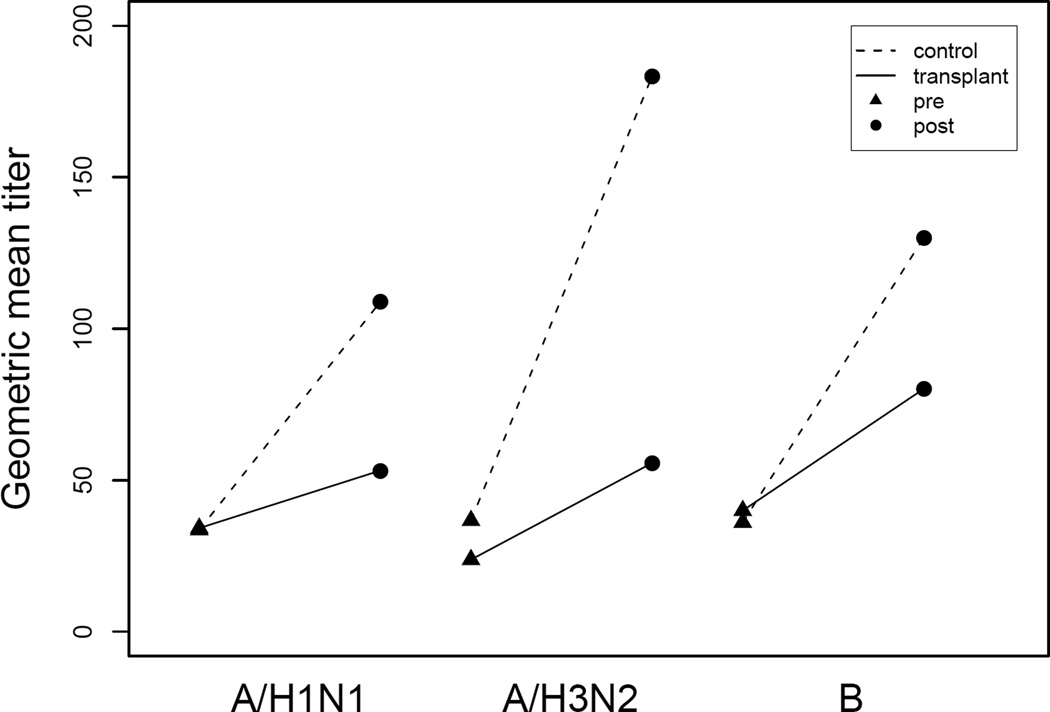

Antibody titers

Geometric mean titers are shown in Figure 2. No significant differences in prevaccination geometric mean titers for A/H1N1 and B types were observed between the control and transplant recipient groups with the difference for A/H3N2 of borderline significance (36.7 controls, 23.8 transplant recipients, P = 0.05). Post vaccination titers increased significantly from baseline for all three influenza types within both groups. The mean change in pre to post vaccination titer was significantly different between the control and transplant recipient groups for all three types.

Figure 2.

Serologic response to the 2006–07 inactivated influenza vaccine expressed as geometric mean titers. For control group: A/H1N1 pre 33.6, post 108.9; A/H3N2 pre 36.7, post 180.4; B pre 36.1, post 130.1. For transplant recipient group: A/H1N1 pre 34.2, post 53.2, A/H3N2 pre 23.8, post 55.7; B pre 40, post 80.2.

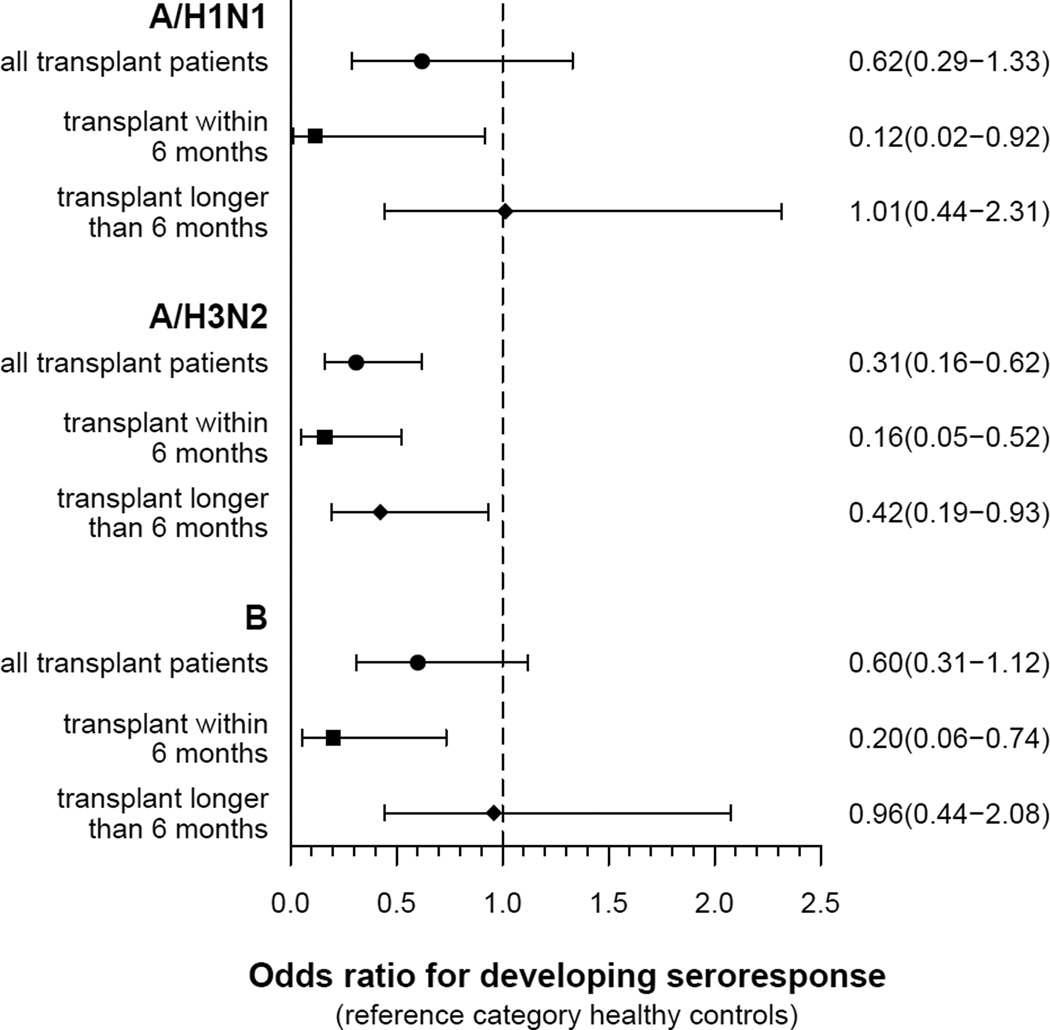

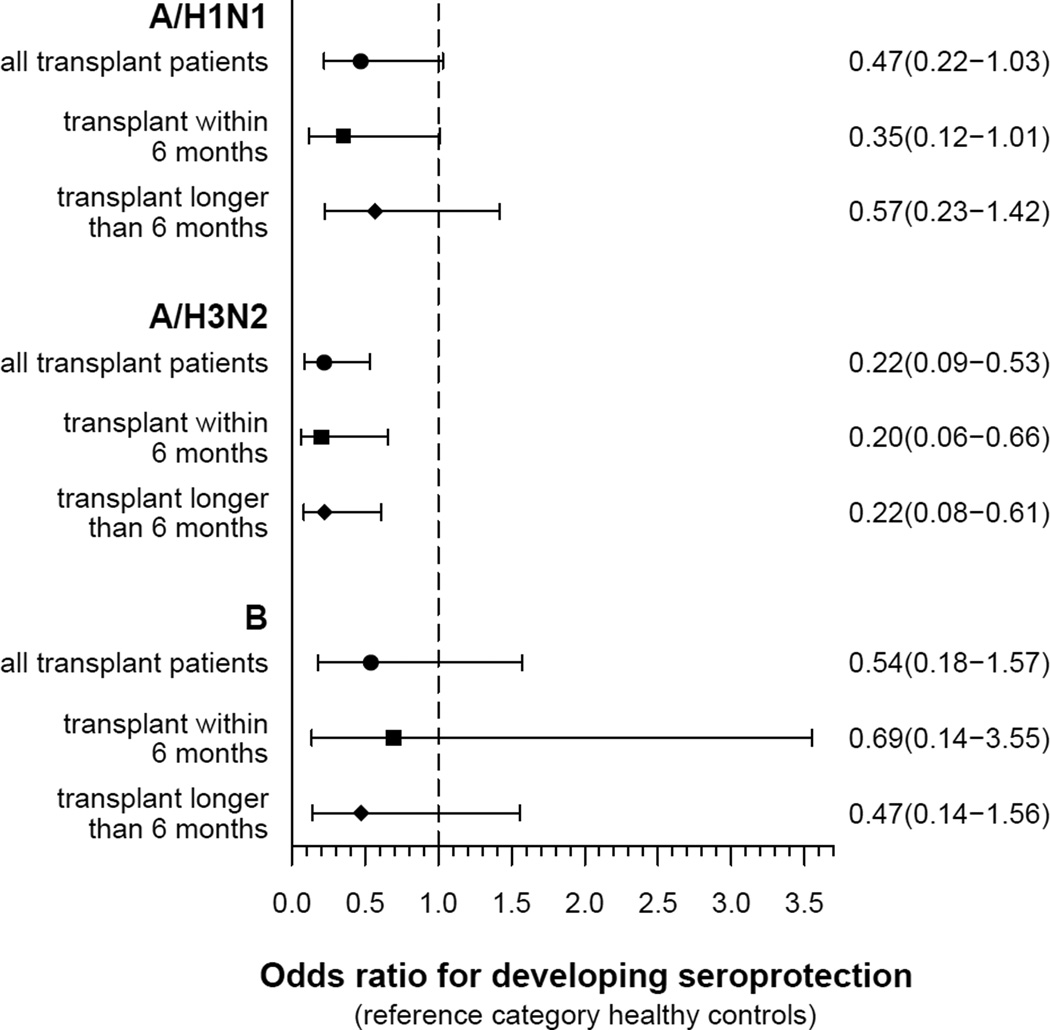

Primary Outcome: Seroresponse and Seroprotection

A smaller proportion of the transplant recipient group compared with the healthy control group developed the primary outcomes of seroresponse or seroprotection for all three influenza types at one month post vaccination (Table 3). The differences were statistically significant only for influenza type A/H3N2, where the transplant recipient group had 0.31 decreased odds of developing seroresponse (95% CI 0.16 to 0.62, P = 0.001) and 0.22 decreased odds of developing seroprotection (95% CI 0.09 to 0.53, P = 0.001) compared with healthy controls (Figures 3 & 4). These results remained unchanged after adjusting for age, sex, and race (Table 4). On univariate analysis, neither basic demographic factors nor serum creatinine were strong predictors across all outcomes (Table S1).

Table 3.

Percentages and odds ratios of developing antibody response to the 2006–07 influenza vaccine in all participants.

| Controls (%) N = 106 |

Transplant Recipients (%) N = 53* |

Unadjusted Odds Ratio |

95% CI | P | Adjusted Odds Ratio |

95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seroresponse (four-fold rise) | ||||||||

| A/H1N1 | 32.1 | 22.6 | 0.62 | 0.29–1.33 | 0.2 | 0.93 | 0.36–2.41 | 0.9 |

| Tx < 6 months | 5.3 | 0.12 | 0.02–0.92 | 0.04 | 0.19 | 0.02–1.55 | 0.1 | |

| Tx > 6 months | 32.4 | 1.01 | 0.44–2.31 | 0.9 | 1.68 | 0.58–4.86 | 0.3 | |

| A/H3N2 | 62.3 | 34.0 | 0.31 | 0.16–0.62 | 0.001 | 0.29 | 0.12–0.67 | 0.004 |

| Tx < 6 months | 21.1 | 0.16 | 0.05–0.52 | 0.002 | 0.16 | 0.05–0.55 | 0.004 | |

| Tx > 6 months | 41.2 | 0.42 | 0.19–0.93 | 0.03 | 0.40 | 0.15–1.03 | 0.06 | |

| B | 48.1 | 35.8 | 0.60 | 0.31–1.12 | 0.1 | 0.48 | 0.21–1.13 | 0.09 |

| Tx < 6 months | 15.8 | 0.20 | 0.06–0.74 | 0.02 | 0.18 | 0.05–0.74 | 0.02 | |

| Tx > 6 months | 47.1 | 0.96 | 0.44–2.08 | 0.9 | 0.76 | 0.29–1.97 | 0.6 | |

| Seroprotection (post titer ≥ 1:32) | ||||||||

| A/H1N1 | 83.0 | 69.8 | 0.47 | 0.22–1.03 | 0.06 | 0.49 | 0.19–1.25 | 0.1 |

| Tx < 6 months | 63.2 | 0.35 | 0.12–1.01 | 0.05 | 0.40 | 0.13–1.29 | 0.1 | |

| Tx > 6 months | 73.5 | 0.57 | 0.23–1.42 | 0.2 | 0.56 | 0.19–1.71 | 0.3 | |

| A/H3N2 | 91.5 | 69.8 | 0.22 | 0.09–0.53 | 0.001 | 0.28 | 0.10–0.81 | 0.02 |

| Tx < 6 months | 68.4 | 0.20 | 0.06–0.66 | 0.008 | 0.26 | 0.07–0.91 | 0.04 | |

| Tx > 6 months | 70.6 | 0.22 | 0.08–0.61 | 0.003 | 0.30 | 0.09–0.99 | 0.05 | |

| B | 92.5 | 86.8 | 0.54 | 0.18–1.57 | 0.3 | 0.44 | 0.12–1.59 | 0.2 |

| Tx < 6 months | 89.5 | 0.69 | 0.14–3.55 | 0.7 | 0.64 | 0.11–3.65 | 0.6 | |

| Tx > 6 months | 85.3 | 0.47 | 0.14–1.56 | 0.2 | 0.34 | 0.08–1.44 | 0.1 | |

Note: Model adjusted for control versus transplant participant, age, baseline serum creatinine.

Abbreviation: Tx, transplanted.

N = 19 for transplant participants < 6 months from time of transplant, N= 34 for transplant participants > 6 months from time of transplant.

Figure 3.

Odds ratios (95% CI) for the primary outcome seroresponse (four-fold rise in antibody titer).

Figure 4.

Odds ratios (95% CI) for the primary outcome seroprotection (antibody titer ≥ 1:32).

Table 4.

Unadjusted and adjusted odds ratio (95% CI) of kidney transplant recipients developing the outcomes seroresponse or seroprotection compared with controls.

| Seroresponse OR (95% CI) | Seroprotection OR (95% CI) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A/H1N1 | A/H3N2 | B | A/H1N1 | A/H3N2 | B | |

| Group | 0.62 (0.29–1.33) | 0.31 (0.16–0.62) | 0.60 (0.31–1.12) | 0.47 (0.22–1.03) | 0.22 (0.09–0.53) | 0.54 (0.18–1.57) |

| Group + age | 0.69 (0.32–1.50) | 0.32 (0.16–0.64) | 0.65 (0.33–1.23) | 0.51 (0.23–1.13) | 0.22 (0.09–0.54) | 0.58 (0.20–1.71) |

| Group + sex* | 0.51 (0.23–1.13) | 0.29 (0.14–0.61) | 0.63 (0.31–1.27) | 0.48 (0.21–1.08) | 0.29 (0.11–0.74) | 0.39 (0.13–1.23) |

| Group + race | 0.62 (0.29–1.36) | 0.31 (0.16–0.62) | 0.60 (0.30–1.18) | 0.47 (0.22–1.03) | 0.21 (0.09–0.52) | 0.52 (0.18–1.53) |

| Group + serum creatinine | 0.89 (0.35–2.25) | 0.28 (0.12–0.66) | 0.47 (0.20–1.09) | 0.48 (0.19–1.22) | 0.28 (0.10–0.80) | 0.43 (0.12–1.55) |

| Group + previous vaccination | 0.66 (0.31–1.44) | 0.31 (0.16–0.62) | 0.62 (0.31–1.23) | 0.48 (0.22–1.04) | 0.18 (0.07–0.46) | 0.52 (0.18–1.54) |

Note: Group is kidney transplant recipients versus healthy controls.

Reference category for sex is women.

One-third of the transplant recipient participants were 6 months or less from date of kidney transplantation, a time period of more intense immunosuppression. Therefore, stratified analyses were conducted for kidney transplant recipient participants less than or greater than 6 months (defined as less or greater than 183 days) from time of transplantation compared with the healthy control group. Of the 53 transplant recipient participants, 19 were less than 6 months and 34 were greater than 6 months since transplantation. The two transplant recipient groups did not differ between each other by age, sex, race, baseline kidney function, cadaveric versus living donor source, induction agent, prior influenza vaccination, or baseline seroprotection. More prednisone use was seen in the group greater than 6 months post transplantation (Table 2). For the outcome seroresponse, kidney transplant recipient participants within 6 months of transplantation were significantly less likely than healthy controls to develop a four-fold rise in titer for all three influenza types. Those transplanted greater than 6 months were also significantly less likely than controls to develop seroresponse for type A/H3N2 (Table 3, Figure 3). Seroprotection results were similar for the A subtypes, with those less than 6 months from transplantation having a decreased odds of developing seroprotection compared with healthy controls. No difference was seen for B (Figure 4).

A subgroup analysis was performed considering only participants without baseline seroprotection since participants with baseline seroprotection would already have met the outcome of seroprotection and might influence the results of seroresponse as well. By selecting these participants, the new cohort size for A/H1N1 was 69, for A/H3N2 65, and for B 64. The odds of susceptibles achieving a protective titer ranged 54–85% lower in transplant recipient participants, supporting the results of the full cohort (Table 5).

Table 5.

Percentages and odds ratios of developing antibody response to the 2006–07 influenza vaccine in participants without baseline seroprotection.

| Control (%) |

Transplant (%) |

Unadjusted Odds Ratio |

95% CI | P | Age Adjusted Odds Ratio |

95% CI | P | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Seroresponse (four-fold rise) | ||||||||

| A/H1N1* | 58.3 | 38.1 | 0.44 | 0.15–1.26 | 0.1 | 0.41 | 0.14–1.23 | 0.1 |

| Tx < 6 months | 12.5 | 0.10 | 0.01–0.90 | 0.04 | 0.09 | 0.01–0.82 | 0.03 | |

| Tx > 6 months | 53.8 | 0.83 | 0.24–2.86 | 0.8 | 0.82 | 0.23–2.94 | 0.8 | |

| A/H3N2† | 88.9 | 55.2 | 0.15 | 0.04–0.55 | 0.004 | 0.16 | 0.04–0.55 | 0.004 |

| Tx < 6 months | 36.4 | 0.07 | 0.01–0.36 | 0.001 | 0.07 | 0.01–0.36 | 0.001 | |

| Tx > 6 months | 66.7 | 0.25 | 0.06–1.04 | 0.06 | 0.25 | 0.60–1.05 | 0.06 | |

| B‡ | 75.0 | 50.0 | 0.33 | 0.11–1.01 | 0.05 | 0.25 | 0.07–0.88 | 0.03 |

| Tx < 6 months | 28.6 | 0.13 | 0.02–0.79 | 0.03 | 0.10 | 0.01–0.69 | 0.02 | |

| Tx > 6 months | 61.5 | 0.53 | 0.14–1.98 | 0.4 | 0.41 | 0.10–1.77 | 0.2 | |

| Seroprotection (post titer ≥ 1:32) | ||||||||

| A/H1N1* | 62.5 | 23.8 | 0.19 | 0.06–0.60 | 0.005 | 0.15 | 0.04–0.53 | 0.003 |

| Tx < 6 months | 12.5 | 0.09 | 0.01–0.76 | 0.03 | 0.07 | 0.01–0.63 | 0.02 | |

| Tx > 6 months | 30.8 | 0.27 | 0.07–0.99 | 0.05 | 0.23 | 0.06–0.91 | 0.04 | |

| A/H3N2† | 75.0 | 44.8 | 0.27 | 0.10–0.78 | 0.02 | 0.28 | 0.10–0.79 | 0.02 |

| Tx < 6 months | 45.5 | 0.28 | 0.07–1.13 | 0.07 | 0.31 | 0.07–1.29 | 0.1 | |

| Tx > 6 months | 44.4 | 0.27 | 0.08–0.88 | 0.03 | 0.26 | 0.08–0.86 | 0.03 | |

| B‡ | 84.1 | 65.0 | 0.35 | 0.10–1.19 | 0.09 | 0.31 | 0.09–1.12 | 0.07 |

| Tx < 6 months | 71.4 | 0.47 | 0.08–2.94 | 0.4 | 0.44 | 0.07–2.89 | 0.4 | |

| Tx > 6 months | 61.5 | 0.30 | 0.08–1.20 | 0.09 | 0.25 | 0.06–1.10 | 0.07 | |

Note: Model adjusted for control versus transplant participant, age.

Abbreviation: Tx, transplanted.

N = 48 for controls and N = 21 (N= 8 less than 6 months, N = 13 greater than 6 months) for transplant recipients for A/H1N1.

N = 36 for controls and N = 29 (N = 11 less than 6 months, N = 18 less than 6 months) for transplant recipients for A/H3N2.

N = 44 for controls and N = 20 (N = 7 less than 6 months, N = 13 less than 6 months) for transplant recipients for B.

As noted, baseline kidney function differed between the two groups. To understand how kidney function might influence vaccine response, multivariate logistic regression was performed. Covariates included were group (transplant recipient versus control), age, and serum creatinine. The results were overall unchanged (Table 3). Due to the almost non-overlapping distribution of group and serum creatinine, strong colinearity between these two covariates produced too much instability for the model to be used for the smaller cohort of participants with no baseline seroprotection. This cohort was adjusted for group and age (Table 5).

Serum creatinine in transplant recipient participants at the one month follow up visit was not significantly different from the baseline measurement. No adverse events were reported by any of the study participants consistent with the known safety profile of the inactivated influenza vaccine.

Discussion

In this prospective cohort study, we showed that the proportion of participants developing a four-fold rise in titer or a post vaccination titer of greater than 1:32 to the 2006–07 inactivated influenza vaccine was decreased in kidney transplant recipients compared with healthy controls. While the overall difference was statistically significant only for the A/H3N2 type, participants less than 6 months post transplantation had significantly decreased antibody responses for all 3 influenza types compared with healthy controls. Further, controlling for presence of baseline seroprotection magnified the difference observed between the transplant recipient and healthy control groups. These results may be clinically important to the practice of influenza vaccination in kidney transplant recipients on current immunosuppression protocols including tacrolimus. A more definitive study with larger sample size would be useful for generalizing these results.

Tacrolimus is a type of calcineurin inhibitor that blocks T cell lymphokine production and inhibits B cell activation and proliferation, putting participants at higher risk for bacterial and viral infection,20 and potentially a decreased response to vaccines dependent on these functions. Previous studies evaluating cyclosporine, an older type of calcineurin inhibitor no longer used as commonly for post kidney transplantation immunosuppression, suggested it caused decreased antibody response to influenza vaccine. Two studies compared kidney transplant recipients treated with cyclosporine versus azathioprine, and both found the cyclosporine groups had a decreased response to influenza vaccine compared with controls.9, 10 We selected participants taking only tacrolimus-based regimens because tacrolimus is part of the most widely used initial regimens for kidney transplantation in the United States. Tacrolimus formed 82% of all regimens for 2006, compared to 12% for cyclosporine.21 By focusing on this drug, we also minimized our chance of seeing no significant difference based on confounders that may have been introduced by considering multiple different regimens at once.

The immediate time period post transplantation is one of intense immunosuppression, due to use of induction immunosuppression agents at time of surgical transplantation and higher doses of immunosuppressive medication in the first several months. The immunosuppressive effects supplied by an induction agent depend on the agent used, but can last months.22, 23 The schedule for tapering down the dose of immunosuppression varies by center, but in general, as practiced at our institution, doses are usually tapered after 6 months providing an arbitrary but clinically reasonable cut point for greater or lesser immunosuppression for a general kidney transplant recipient. Accordingly, when stratifying the transplant recipient group by less than or greater than six months since time of transplantation, we were able to detect significantly poorer antibody responses to the influenza vaccine in the transplant recipients less than 6 months compared with healthy controls. These findings remained statistically significance despite the transplant recipient groups containing smaller numbers of participants once divided, meaning we had less power to find such differences.

At our institution, influenza vaccination is routinely offered to recipients who are one month or more post transplantation, which may vary from other centers that choose to wait longer. Our cohort, with a median time from transplantation of 307 days, has a considerably decreased time from transplantation compared to the two most recent published studies about kidney transplant recipients and influenza vaccination. In these studies, participants less than 6 months from were excluded and time from transplantation was 53 months (mean) in one study and 6.3 years (median) in the other.24, 25 Our finding suggests the vaccine may not work as well in these early post transplantation participants. As a result, clinicians should have a greater suspicion for susceptibility to influenza despite vaccination in this group. One could also consider not administering the vaccine until a recipient is at least 6 months post transplantation. However, even though those transplanted less than 6 months do not respond as well as healthy controls, some individuals do have a response and are protected, raising the question of the cost-benefit of giving the vaccine earlier. This group could be further studied to see if a second vaccine dose such as is given in children would help boost antibody response.26, 27

The difference seen in antibody response to A/H3N2 versus the other influenza types is not unusual. Response to different components of the vaccine may vary based on prior exposures to circulating wild type viruses and previous vaccination.28–30 These exposures also resulted in several cohort members having the presence of protective antibodies greater than 1:32. Clinically, the proportions of participants without baseline seroprotection are interesting to examine since they are the subgroup at risk for influenza infection during the concurrent season. As a result, we analyzed these participants separately, and found results similar to the larger cohort. As determined in other studies, presence of baseline seroprotection prior to vaccination results in less robust vaccine responses.8, 25, 28

Our findings differ from main findings of two recent papers that examined cohorts of kidney transplant recipients and found that seroresponse and seroprotection post-vaccination was similar between transplant recipients and healthy controls.24, 25 In addition to differences in time from transplantation as already discussed, these studies differ from the present one in types of immunosuppression being used. In the study by Scharpé et al., the transplant recipient group was on a variety of immunosuppressants whereas our study only considers transplant recipients on tacrolimus-based regimens, as we were concerned with defining responses in kidney transplant recipient participants on the most common type of calcineurin inhibitor in use. Keshtkar-Jahromi et al. compared vaccine responses in participants on mycophenolate mofetil versus azathioprine in addition to prednisolone and cyclosporine.

Several limitations of our study exist. First, since everyone received the vaccine, it was not possible to randomize the participants. One way to address this in future studies is to match the participants for certain variables like age, sex, or race to help minimize confounding. Second, while the proportion of responders in the overall transplantation group was always less for each influenza type compared with healthy controls, our primary outcome measures of seroresponse and seroprotection were not always statistically significant. Given this trend, a larger cohort might provide increased power to find this difference statistically significant. Third, we were unable to perform extensive multivariate analysis due to small number of events/non-events. We were able to control for some important confounders, however, through limitations of the inclusion criteria, stratified analysis, and subgroup analysis. One potential confounder is decreased kidney function. Previous studies have shown diminished response to influenza vaccination in participants with chronic kidney disease, particularly in dialysis patients.31, 32 In kidney transplant recipients, older studies have conflicted on the role of immunosuppression versus decreased kidney function as a cause for impaired vaccine response.5, 33 Since the transplant recipient and control groups had an almost non-overlapping distribution of serum creatinine, adjustment for serum creatinine in the multivariable logistic regression model introduced instability to the model due to colinearity between presence of transplant and serum creatinine, but overall the results for the full cohort were unchanged once adjusted for serum creatinine. Addition of a concurrent group of chronic kidney disease patients with similar kidney function to the transplant recipient group should be explored in future studies.

In summary, we found that the proportion of transplant recipient participants with antibody response to the inactivated influenza vaccine was consistently less compared with controls for all three influenza types, but this reaches statistical significance only for A/H3N2. When participants less than 6 months from time of transplantation were considered, this group had a significantly decreased response to the vaccine as compared with healthy controls, especially for the A subtypes. Future studies comparing transplantation patients to chronic kidney disease patients with similar kidney function or using influenza vaccines with booster doses in participants within 6 months of transplantation may provide more comprehensive information in this area.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Support: Supported in part by Vanderbilt CTSA grant 1 UL1 RR024975 from the National Center for Research Resources, National Institutes of Health; NIH/NRSA Training Grant 5 T32 DK007569-17; and K24 DK62849 from the National Institute of Diabetes, Digestive and Kidney Diseases.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Financial Disclosure: None.

Supplementary Material

Table S1: Univariate analysis of selected covariates for the outcomes seroresponse and seroprotection expressed as odds ratios.

Note: The supplementary material accompanying this aricle (doi: ____) is available at www.ajkd.org.

References

- 1.Kotton CN, Fishman JA. Viral infection in the renal transplant recipient. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2005;16(6):1758–1774. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2004121113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vilchez RA, Fung J, Kusne S. The pathogenesis and management of influenza virus infection in organ transplant recipients. Transpl Infect Dis. 2002;4(4):177–182. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3062.2002.t01-4-02001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fiore AE, Shay DK, Haber P, et al. Prevention and control of influenza. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP), 2007. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2007;56(RR-6):1–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carroll RN, Marsh SD, O'Donoghue EP, Breeze DC, Shackman R. Response to influenza vaccine by renal transplant patients. Br Med J. 1974;2(5921):701–703. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.5921.701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pabico RC, Douglas RG, Betts RF, McKenna BA, Freeman RB. Antibody response to influenza vaccination in renal transplant patients: correlation with allograft function. Ann Intern Med. 1976;85(4):431–436. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-85-4-431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Stiver HG, Graves P, Meiklejohn G, Schroter G, Eickhoff TC. Impaired serum antibody response to inactivated influenza A and B vaccine in renal transplant recipients. Infect Immun. 1977;16(3):738–741. doi: 10.1128/iai.16.3.738-741.1977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kumar SS, Ventura AK, VanderWerf B. Influenza vaccination in renal transplant recipients. Jama. 1978;239(9):840–842. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Briggs WA, Rozek RJ, Migdal SD, et al. Influenza vaccination in kidney transplant recipients: cellular and humoral immune responses. Ann Intern Med. 1980;92(4):471–477. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-92-4-471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang KL, Armstrong JA, Ho M. Antibody response after influenza immunization in renal transplant patients receiving cyclosporin A or azathioprine. Infect Immun. 1983;40(1):421–424. doi: 10.1128/iai.40.1.421-424.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Versluis DJ, Beyer WE, Masurel N, Wenting GJ, Weimar W. Impairment of the immune response to influenza vaccination in renal transplant recipients by cyclosporine, but not azathioprine. Transplantation. 1986;42(4):376–379. doi: 10.1097/00007890-198610000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sanchez-Fructuoso AI, Prats D, Naranjo P, et al. Influenza virus immunization effectivity in kidney transplant patients subjected to two different triple-drug therapy immunosuppression protocols: mycophenolate versus azathioprine. Transplantation. 2000;69(3):436–439. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200002150-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Foley RN, Collins AJ. End-stage renal disease in the United States: an update from the United States renal data system. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18(10):2644–2648. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2007020220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schwartz B, Martin SW. Principles of Epidemiology and Public Health. In: SS Long., editor. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Inc; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 14.European Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products. Note for guidance on harmonization of requirements for influenza vaccines, March 1997 (CPMP/BWP/214/96) Vol. 12. Brussels: European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products; Mar, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fox JP, Hall CE, Cooney MK, Foy HM. Influenzavirus infections in Seattle families, 1975–1979. I. Study design, methods and the occurrence of infections by time and age. Am J Epidemiol. 1982;116(2):212–227. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a113407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Warburton MF. Immunization against influenza. Med J Aust. 1972;1(11):546–547. doi: 10.5694/j.1326-5377.1972.tb46935.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rudenko LG, Slepushkin AN, Monto AS, et al. Efficacy of live attenuated and inactivated influenza vaccines in schoolchildren and their unvaccinated contacts in Novgorod, Russia. J Infect Dis. 1993;168(4):881–887. doi: 10.1093/infdis/168.4.881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Levey AS, Coresh J, Greene T, et al. Using standardized serum creatinine values in the modification of diet in renal disease study equation for estimating glomerular filtration rate. Ann Intern Med. 2006;145(4):247–254. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-145-4-200608150-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kendal AP, Skehel JJ, Pereira MS. Concepts and procedures for laboratory-based influenza surveillance. Atlanta: US Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Centers for Disease Control; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Peters DH, Fitton A, Plosker GL, Faulds D, Tacrolimus A review of its pharmacology, and therapeutic potential in hepatic and renal transplantation. Drugs. 1993;46(4):746–794. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199346040-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) and the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) 2007 Annual Report of the U.S. Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients: Transplant Data 1997–2006. Rockville, MD: Health Resources and Services Administration, Healthcare Systems Bureau, Division of Transplantation; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hardinger KL, Schnitzler MA, Miller B, et al. Five-year follow up of thymoglobulin versus ATGAM induction in adult renal transplantation. Transplantation. 2004;78(1):136–141. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000132329.67611.3f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kirk AD. Induction immunosuppression. Transplantation. 2006;82(5):593–602. doi: 10.1097/01.tp.0000234905.56926.7f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Keshtkar-Jahromi M, Argani H, Rahnavardi M, et al. Antibody Response to Influenza Immunization in Kidney Transplant Recipients Receiving either Azathioprine or Mycophenolate: A Controlled Trial. Am J Nephrol. 2008;28(4):654–660. doi: 10.1159/000119742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Scharpe J, Evenepoel P, Maes B, et al. Influenza vaccination is efficacious and safe in renal transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2008;8(2):332–337. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-6143.2007.02066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Englund JA, Walter EB, Fairchok MP, Monto AS, Neuzil KM. A comparison of 2 influenza vaccine schedules in 6- to 23-month-old children. Pediatrics. 2005;115(4):1039–1047. doi: 10.1542/peds.2004-2373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Neuzil KM, Jackson LA, Nelson J, et al. Immunogenicity and reactogenicity of 1 versus 2 doses of trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine in vaccine-naive 5-8-year-old children. J Infect Dis. 2006;194(8):1032–1039. doi: 10.1086/507309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edwards KM, Dupont WD, Westrich MK, Plummer WD, Jr, Palmer PS, Wright PF. A randomized controlled trial of cold-adapted and inactivated vaccines for the prevention of influenza A disease. J Infect Dis. 1994;169(1):68–76. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.1.68. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hoskins TW, Davies JR, Smith AJ, Allchin A, Miller CL, Pollock TM. Influenza at Christ's Hospital: March, 1974. Lancet. 1976;1(7951):105–108. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(76)93151-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Keitel WA, Cate TR, Couch RB, Huggins LL, Hess KR. Efficacy of repeated annual immunization with inactivated influenza virus vaccines over a five year period. Vaccine. 1997;15(10):1114–1122. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(97)00003-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dinits-Pensy M, Forrest GN, Cross AS, Hise MK. The use of vaccines in adult patients with renal disease. Am J Kidney Dis. 2005;46(6):997–1011. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2005.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Osanloo EO, Berlin BS, Popli S, et al. Antibody responses to influenza vaccination in patients with chronic renal failure. Kidney Int. 1978;14(6):614–618. doi: 10.1038/ki.1978.170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gilbertson DT, Unruh M, McBean AM, Kausz AT, Snyder JJ, Collins AJ. Influenza vaccine delivery and effectiveness in end-stage renal disease. Kidney Int. 2003;63(2):738–743. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2003.00787.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.