Abstract

Objective

Older women with ovarian cancer have increased cancer-related mortality and chemotherapy toxicity. CA125 is a sensitive biomarker for tumor burden. The study evaluates the association between CA125, geriatric assessment (GA), and treatment toxicity.

Methods

This is a secondary subset analysis of patients age ≥65 with ovarian cancer accrued to a multicenter prospective study that developed a predictive toxicity score for older adults with cancer. Clinical and geriatric covariates included sociodemographics, GA (comorbidity, social support, functional, nutritional, psychological, cognitive status), treatment, and labs. Utilizing bivariate analyses, we determined the association of abnormal CA125 (≥35 U/mL) with baseline GA, grade 3–5 toxicity (CTCAE v.3), dose adjustments, and hospitalization. Logistic regression analysis was used to check for potential confounder for association between CA125 and chemotherapy toxicity.

Results

Fifty-one (10%) of 500 patients accrued to the primary study had a diagnosis of ovarian (92%), peritoneal (4%), or fallopian tube (4%) cancer. Median age was 72 (range, 65–86). Forty-six patients (90%) had stage III–IV disease. Twenty-three patients (45%) received first-line chemotherapy, and 34 (67%) received platinum-doublet therapy. Thirty-six (71%) had an abnormal CA125. Grade 3–5 toxicity occurred in 19 patients (37%). Abnormal CA125 was associated with assistance with instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) (p<0.05), lower performance status (p=0.05), grade 3–5 toxicity (p=0.03), non-heme toxicity (p=0.04), and dose reductions (p=0.01). No association between CA125 level and total toxicity score was observed.

Conclusions

Among older women with ovarian cancer, abnormal CA125 was associated with poor pre-treatment functional status and an increased probability of chemotherapy toxicity and dose reduction.

Keywords: CA125, older women, ovarian cancer, chemotherapy toxicity, functional status

Introduction

More than half of the women diagnosed with ovarian cancer are 65 years of age or older [1,2]. As our population ages, the incidence of malignancies, including ovarian cancer, in older adults is expected to significantly rise [3,4]. Older women are less likely to be offered standard treatments, have poorer outcomes, and develop higher toxicity to treatment for ovarian cancer [5–7]. Advanced age has been shown to be an independent risk factor for survival in ovarian cancer [8,9]. The challenges for oncologists lie in the heterogenicity of this patient population; some will tolerate chemotherapy as well as younger women, while others will experience severe toxicity [10]. The identification of risk factors besides chronologic age will be vital to guide treatment decisions such as aggressive surgical debulking and/or chemotherapy.

CA125 is the most widely used biomarker in the management of ovarian cancer [11,12]. Despite the well-characterized limitations of a solitary CA125 level, this biomarker has high sensitivity in advanced disease and is useful as a surrogate for ovarian cancer tumor burden [13]. Numerous studies have demonstrated CA125 as a prognostic factor for overall survival and response to chemotherapy [14–16]. Greater tumor burden in older women, marked by an elevated baseline CA125 level, may result in decreased functional status and poorer tolerance to cancer treatment due to the increased physiological stress. The elevated CA125 level and association with outcomes in older women with ovarian cancer has not previously been evaluated.

Several studies have demonstrated the predictive value of a cancer-specific geriatric assessment (GA) for estimating the risk of severe toxicity from chemotherapy in older adults with cancer; however, this has not been commonly used in women with gynecologic cancer [17,18]. The Cancer and Aging Research Group (CARG) GA measures functional status, co-morbid medical conditions, cognition, psychological status, social functioning-support, and nutritional status [17]. This GA is mostly self-administered and feasible. A shorter predictive model derived from this GA (11-point toxicity score) identified patients at greatest risk of grade 3–5 chemotherapy toxicity with greater precision than chronological age or performance status alone.

The objective of this study was to evaluate the association of baseline (pre-chemotherapy) CA125 level with chemotherapy toxicity and GA parameters in older women with epithelial ovarian cancer. This can be clinically useful to better identify and target interventions to a subgroup of older ovarian cancer patients at highest risk of treatment toxicity.

Methods

This study is a secondary subset analysis of data from a large multicenter, prospective, longitudinal study by CARG evaluating the utility of a comprehensive GA in predicting chemotherapy toxicity among a cohort of older adults with cancer [17]. Patients were eligible if they were aged ≥ 65 years, had a diagnosis of cancer (excluding non-melanoma skin cancer), were scheduled to receive a new chemotherapy regimen, were English speaking, and were able to provide informed consent. Informed consent was obtained from all study participants. The institutional review boards at all seven participating sites approved this study.

The CARG GA measures functional status (i.e., ability to live independently at home and in the community), co-morbid medical conditions, cognition, psychological status, social functioning-support, and nutritional status (Table 1). This GA is mostly self-administered, feasible, and short (mean time to completion, 27 minutes). A member of the health care team assisted those who needed help with completing the questionnaire.

Table 1.

Description of Geriatric Assessment measures

| Measure | Description | Scoring | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Functional status | Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IADL) (Older Americans Resources and Services subscale) | 7 items evaluating the ability of complete activities required to maintain independence in the community | Score, 0–14, a score of 14 indicates no impairment in the completion of IADL |

| Karnofsky performance status | Global evaluation of physical function as determined by patient self-report or by the physician | Score, 0–100%; a score of 100% indicates normal physical function | |

| Falls | Self-reported no. of falls in the 6 mos. before the study | Score is variable, no. of falls reported | |

| Timed Get Up and Go Test | Test of physical mobility as measured by time in seconds it takes to stand up from chair, walk a distance of 3 meters, turn, and return to sit in chair. | Score is measured in time in seconds. Scores <10 seconds indicate normal mobility; scores >14 seconds indicate higher risk of falls | |

|

| |||

| Cognitive status | Blessed Orientation-Memory Concentration (BOMC) scale | 6 weighted items evaluating 3 components of cognitive function (i.e., orientation, memory, concentration) | Score, 0–28; scores ≥11 indicate significant underlying cognitive impairment |

|

| |||

| Nutritional status | Unintentional weight loss | Self-reported weight loss in the last 6 mos. before the study | |

|

| |||

| Psychological status | Hospital Anxiety/Depression Scale (HADS) | 14 items on a Likert scale, with 7 items evaluating for anxiety symptoms and 7 evaluating for depressive symptoms | Score, 0–42; scores ≥15 indicate significant underlying anxiety or depression |

|

| |||

| Social support | Medical Outcomes Study (MOS) Social Activity scale | 4 items on a Likert scale evaluating how physical or emotional problems interfere with social activities | Score, 0–100; higher scores indicate requiring greater support with social activity |

| MOS Social Support Survey: Emotional and Tangible subscales | 12 items on a Likert scale evaluating quality of life across medical conditions | Score, 0–100; higher scores indicate requiring greater support | |

|

| |||

| Comorbidity | Number, type, and severity of comorbidity | “Yes-or-no” checklist of 13 comorbid conditions with a 3-point Likert scale rating the impact of each condition on daily function | Scored as the no. and type of comorbid illnesses |

| Number of prescription medications | Self-reported no. of daily prescription medications | Scored as the no. of medications | |

Baseline sociodemographic characteristics, tumor characteristics (tumor type and stage), and pretreatment laboratory data (white blood cell [WBC] count, hemoglobin, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, albumin, liver function tests, and CA125) were recorded. Treatment characteristics including chemotherapy regimen, line of chemotherapy (first line or greater), the use and timing of growth factors (primary or secondary prophylaxis) were captured. Surgical information (i.e., whether the patients were receiving chemotherapy in a neoadjuvant or adjuvant regimen) was not captured in the study data.

The patients were followed from the beginning until the end of the chemotherapy course. The following outcomes were collected: 1) grade 3–5 toxicity using the National Cancer Institute Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (NCI CTCAE) version 3.0; 2) dose delays; 3) dose reductions; and 4) hospitalizations. A predictive model and risk score for chemotherapy toxicity was developed using the baseline demographic, clinical, and geriatric variables. The toxicity score (range, 0–23) can be tabulated from major risk factors, including: 1) age ≥ 72, 2) cancer type (GI or GU), 3) standard chemotherapy dosing, 4) number of chemotherapy drugs, 5) hemoglobin <11g/dl in males and <10g/dl in females 6) renal dysfunction (creatinine clearance <34 mL/min calculated with Jeliffe formula using ideal weight), 7) decreased hearing, 8) one or more falls in last 6 months, 9) requiring assistance with taking medication (IADL, instrumental activities of daily living), 10) limited walking 1 block, and 11) decreased social activity due to physical or emotional health. A higher score is more predictive of toxicity. The toxicity score identified patients at greatest risk of grade 3–5 chemotherapy toxicity with greater precision than chronological age or performance status alone.

Statistical Considerations

The secondary subset analysis included the patients with a diagnosis of ovarian, fallopian tube, or primary peritoneal cancer. Chi square test or Fisher’s exact probability calculation method was used to examine the association of abnormal CA125 level (defined as ≥ 35 U/mL) [19,20] and baseline sociodemographic and clinical information, tumor variables, geriatric characteristics, risk of grade 3–5 toxicity, dose delays, dose reductions, early treatment discontinuation, and hospitalization. Student t-test was used to check the difference of GA variables between the normal CA125 group and abnormal CA125 group.

For each of the patients in the subset, a chemotherapy toxicity score was calculated using the risk factor variables identified in the parent study. Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare total toxicity score between patients with normal CA125 and patients with abnormal CA125. Multivariate logistic regression was performed to check if the total toxicity score is a potential confounder for the association between CA125 and chemotherapy toxicity. STATA SE 12.0 (College Station, Texas, StataCorp) was utilized for the analysis. R (R Foundation) software created the figures.

Results

Fifty-one of the 500 patients accrued to the primary study had a diagnosis of ovarian, primary peritoneal, or fallopian tube malignancy. Baseline patient characteristics and GA scores were examined (Table 2). The mean age of the 51 patients was 72 years (range, 65 to 86 years) and the majority of patients (n=46, 90%) had stage III or IV cancer. The most common comorbidities were arthritis (n=24, 47%), osteoporosis (n=20, 39%), and stomach disorders (n=12, 24%). Chemotherapy use included: 23 (45%) first line, 34 (67%) platinum-doublet, 14 (27%) single agent, and 3 (6%) chemotherapy plus bevacizumab. Thirty-three patients (65%) initiated chemotherapy at the standard doses. The patients in the study were a heterogeneous group, consisting of women who received neoadjuvant, adjuvant, and palliative chemotherapy regimens for their ovarian cancer. Surgical information was not captured in this study.

Table 2.

Baseline patient characteristics and Geriatric Assessment measures

| Patient Characteristics (n=51 patients) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | Median 72 yo | Range 65–86 |

| Cancer Type | n = pts | % |

| Ovarian | 47 | 92 |

| Peritoneal | 2 | 4 |

| Fallopian Tube | 2 | 4 |

| Cancer stage | ||

| I | 4 | 8 |

| II | 1 | 2 |

| III | 19 | 37 |

| IV | 27 | 53 |

| Treatment | ||

| Single-agent chemotherapy | 14 | 27 |

| Platinum-doublet chemotherapy | 34 | 67 |

| Chemotherapy plus Bevacizumab | 3 | 6 |

| Line of chemotherapy | ||

| 1st line | 23 | 45 |

| 2 or more lines | 28 | 55 |

| Standard dose | ||

| No | 18 | 35 |

| Yes | 33 | 65 |

| Comorbidities | ||

| Arthritis | 24 | 47 |

| Circulation problems | 7 | 14 |

| Depression | 11 | 22 |

| Diabetes | 4 | 8 |

| Emphysema | 2 | 4 |

| Glaucoma | 4 | 8 |

| High blood pressure | 19 | 37 |

| Heart Disease | 7 | 14 |

| Liver/Kidney Disease | 1 | 2 |

| Other cancers | 14 | 27 |

| Osteoporosis | 20 | 39 |

| Stomach disorders | 12 | 24 |

| Stroke | 1 | 2 |

| Geriatric Assessment Measures | Mean ± SD | Range |

| Functional status | ||

| Physician-rated KPS | 80±10 | 60–100 |

| Self-rated KPS | 87±10 | 60–100 |

| IADL OARS scale 0–14 | 13±1 | 8–14 |

| MOS physical 0–100 | 75±22 | 20–100 |

| No. of falls in past 6 months | 0±1 | 0–6 |

| Timed get up and go test (sec) | 11±5 | 5.2–36.7 |

| Cognitive status (BOMC) scale 0–28 | 4±5 | 0–28 |

| Nutritional status | ||

| % unintentional weight loss in 6 mo. | 5±7 | 0–23 |

| Psychological status | ||

| HADS scale 0–42 | 8±5 | 0–24 |

| Social Support: MOS scale | 86±17 | 45.8–100 |

| Social Activity: MOS scale | 57±18 | 0–87.5 |

| Comorbidity | ||

| No. of comorbidities | 2±2 | 0–5 |

| No. of prescription medications | 4±3 | 0–17 |

Depression Scale; IADL= Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; KPS=Karnofsky Performance Scale; OARS IADL= Older Americans Resources and Services Instrumental Activities of Daily Living.

The median score on the IADL subscale was 14 (range, 8–14), with 41% of patients requiring assistance with their IADLs; 14% of patients had physician-rated KPS (Karnofsky Performance Status) < 70%, and 20% reported at least one fall in the last 6 months, indicating significant functional impairment. Blessed Orientation-Memory-Concentration (BOMC) test scores ≥11 were observed in 4%, indicating clinically significant cognitive impairment. Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) scores ≥15 were observed in 14%, indicating severe anxiety or depressive symptoms. Unintentional weight loss (>5% of body weight) in the last 6 months was observed in 39%, reflecting lower nutritional status. The mean ±SD number of comorbidities was 2±2 (range, 0–5), and the median number of prescription medications per patient was 4±3 (range, 0–17).

Grade 3–5 chemotherapy toxicity occurred in 19 patients (37%) (Table 3). Of the 52 toxicities observed, 48 (92%) were grade 3, 3 (6%) were grade 4, and 1 (2%) was grade 5. The most common toxicity was grade 3 dehydration (n=8, 16%), and the single grade 5 toxicity was characterized by neutropenic infection, observed in a patient receiving a platinum-doublet treatment regimen. Hematological toxicity, characterized by neutropenia, thrombocytopenia, or anemia, was seen in 11 patients (22%); all required hospitalization. Treatment adjustments included: 17 (33%) dose reductions, 18 (35%) dose delays, and 10 (20%) early treatment discontinuations. Cancer stage and line of chemotherapy were not significantly associated with toxicity.

Table 3.

Bivariate analysis

| Chemotherapy Toxicity | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall N=51 (%) | Normal baseline CA125 (n=15) | Abnormal baseline CA125 (n=36) | p value | |

| Grade 3–5 | 19 (37) | 2 (13) | 17 (47) | 0.03* |

| Heme | 11 (22) | 1 (7) | 10 (28) | 0.14 |

| Non-heme | 15 (30) | 1 (7) | 14 (39) | 0.04* |

| Hospitalization | 11 (22) | 2 (13) | 9 (25) | 0.47 |

| Dose reduction | 17 (33) | 1 (7) | 16 (44) | 0.01* |

| Dose delay | 18 (35) | 5 (33) | 13 (36) | 1.0 |

| Discontinuation of chemotherapy | 10 (20) | 1 (7) | 9 (25) | 0.25 |

| Geriatric Assessment | ||||

| Mean GA score | Mean GA score | |||

| Function (MOS physical) | 75.2 | 75.5 | 0.97 | |

| Function (IADL) | 13.7 | 12.9 | 0.05* | |

| Function (MD KPS) | 86.0 | 80.9 | 0.05* | |

| Function (Patient-rated KPS) | 88.7 | 86.9 | 0.59 | |

| Falls | 0.5 | 0.3 | 0.46 | |

| Timed Up and Go | 9.6 | 11.4 | 0.40 | |

| Psychological status (HADS) | 7.8 | 8.3 | 0.88 | |

| Social activity | 61.7 | 55.7 | 0.27 | |

| Social support | 88.9 | 86.3 | 0.38 | |

| No. of comorbidities | 3.1 | 2.2 | 0.49 | |

| No. of prescription medications | 4.7 | 4.1 | 0.76 | |

statistically significant

HADS= Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; IADL= Instrumental Activities of Daily Living; KPS= Karnofsky Performance Scale; MOS=Medical Outcomes Study

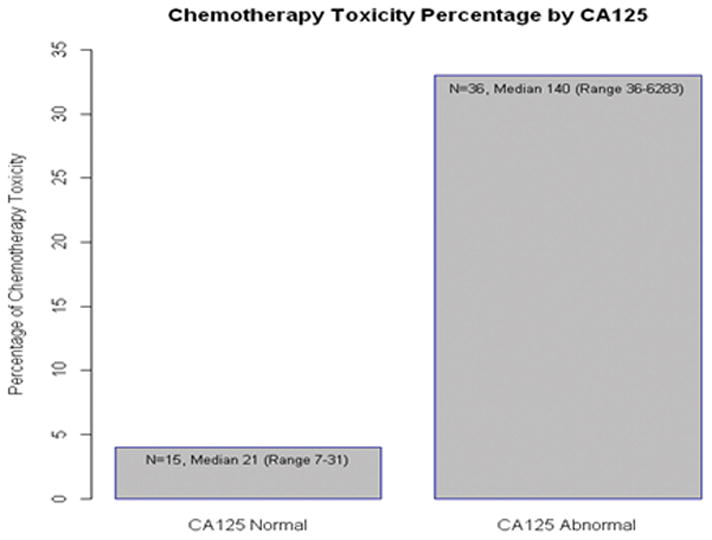

Elevated or abnormal baseline CA125, defined as CA125 >35 U/mL, was observed in 36 patients (71%). The median CA125 level was 140 (range, 36–6283) in this group (Figure 1). Patients with abnormal CA125 were more likely to experience grade 3–5 toxicity, non-hematological toxicity, and chemotherapy dose reductions compared to patients with a normal baseline CA125 level. In bivariate analysis, abnormal CA125 level was associated with poorer functional status (Figure 1). Patients with abnormal CA125 were more likely to require assistance with IADLs, with a lower mean IADL score of 12.9 compared to 13.7. IADL was scored 0–14, with lower scores indicating more assistance with activities. Abnormal baseline CA125 level was associated with lower physician-rated KPS, with a mean KPS of 80.6% compared to 86% in the normal CA125 group. There was no association with CA125 level and number of comorbidities, prescription medications, nutritional status, or HADS scores. Baseline patient demographics, including age, were similar between the normal and abnormal CA125 groups. There was no statistical difference in CA125 levels by cancer stage (I–III vs IV) or line of chemotherapy (first line versus second or greater).

Figure 1.

Percentage of Chemotherapy Toxicity vs. CA125 level

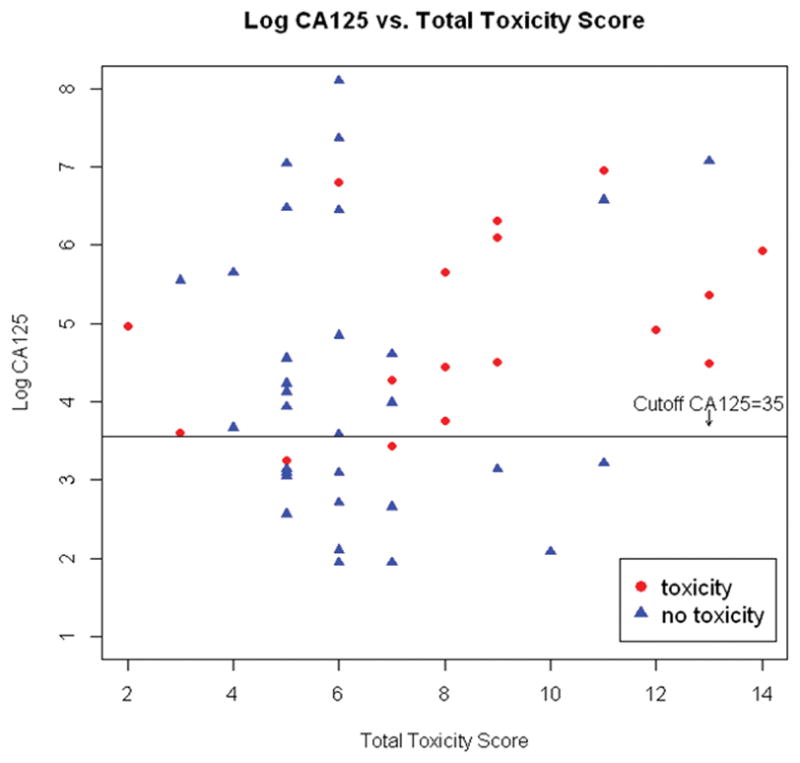

Wilcoxon rank sum test was used to compare the total toxicity score between patients with normal CA125 and patients with abnormal CA125. The median toxicity score for both groups was 6; the mean toxicity score was 6.7 in the normal CA125 group and 7.3 in the abnormal CA125 group. There was not a statistically significant difference (p=0.685); however, the overall toxicity scores for both groups were low (Table 4). Multivariate logistic regression analysis showed total toxicity score is not a confounder in the association between CA125 and chemotherapy toxicity (change of regression coefficient of CA125=8.5%). The combination of abnormal CA125 and high total toxicity scores (8 or greater) appears to be most associated with grade 3–5 chemotherapy toxicity (Figure 2). Log CA125 is presented in the figure to better illustrate the data given the large range of CA125 values.

Table 4.

Association between total toxicity score and CA125

| Total toxicity score | Normal CA125 (n=15) | Abnormal CA125 (n=33)* | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 6.7 | 7.3 | 0.685 |

| Median | 6 | 6 | |

| SD | 1.9 | 3.2 | |

| Range | 5–11 | 2–14 |

3 missing values for this group

Figure 2.

Log CA125 level vs. Total Toxicity Score

Discussion

We demonstrated that an abnormal baseline CA125 is an additional risk factor for chemotherapy toxicity for older women with ovarian cancer and is associated with poorer functional status. We also provided a prospective description of an older patient population with ovarian cancer receiving chemotherapy. To date, there is no reported, large prospective trial in the United States dedicated to older women with gynecologic cancer.

In this series, most women were stage III–IV (90%), treated with platinum-doublets (67%), given standard dose chemotherapy (65%), and generally healthy, with few comorbidities (mean 2) and high functional status (mean IADL13, KPS 80%). Nonetheless, morbidity was high; 37% of patients had severe chemotherapy toxicity (grade 3–5), one-third required dose modifications, and 20% were hospitalized.

Our study explored the predictive value of CA125 level in the setting of a comprehensive cancer-specific GA tool developed by the CARG in older women with ovarian cancer. Pre-chemotherapy CA125 level has been previously shown to be an independent prognostic factor for overall survival and is commonly used as a surrogate for tumor burden [14,21]. In our study, older women with elevated CA125 were more likely to experience grade 3–5 chemotherapy toxicity, especially non-hematological toxicity, and require dose reductions. They were also more likely to require assistance with their activities of daily living and have lower physician-rated KPS. We recognize that a single dichotomized CA125 level has limitations; however, as a surrogate for disease burden [22], it can be a useful biomarker of residual disease after debulking or overall tumor burden. This higher burden of disease may further stress and weaken physiologic reserves, impairing functional status and ability to tolerate chemotherapy.

An abnormal CA125 level was an independent predictor of chemotherapy toxicity and was not associated with the total toxicity score developed by CARG, which includes variables of age, cancer type, chemotherapy dosing, chemotherapy drug, hemoglobin, hearing, falls, taking medicines, walking one block, and social activity. The combination of abnormal CA125 level with the toxicity score of 8 or greater may be more predictive than the 11-point toxicity score alone in an ovarian cancer population; however, this is a hypothesis that requires further investigation as the toxicity score model was developed in a patient population with a heterogeneity of solid cancers and may not be optimized for ovarian cancer.

Among geriatric patients, functional status is a strong predictor of morbidity and mortality [23]. In France, the Group d’Investigateurs Nationaux pour l’Etude des Cancers Ovariens (GINECO) group prospectively studied 83 patients >70 years old with stage III or IV ovarian cancer receiving carboplatin and cyclophosphamide to evaluate a primary endpoint of chemotherapy completion and use of comprehensive GA in predicting severe toxicity [24]. Depression, functional dependence, and performance status ≥2 were independent predictors of treatment toxicity. CA125 was evaluated as a covariate but not found to be significantly associated with chemotherapy toxicity and not included in the multivariate analysis. The disparate results in CA125 level association with toxicity may be explained by the differences in their patient population. The GINECO study was composed primarily of newly diagnosed stage III patients (75%), and 90% underwent laparotomy, with 21% achieving optimal debulking prior to chemotherapy. In our study, the majority of patients (53%) had stage IV or recurrent disease. The higher tumor burden with advanced disease may reflect why abnormal CA125 level was associated with chemotherapy toxicity in our study.

There are limitations to our findings. The population was relatively small and heterogeneous, consisting of women receiving different treatment regimens and some who had received prior chemotherapy. Our endpoints and results were primarily descriptive and hypothesis generating. The study does not take into account whether patients had cytoreductive surgery, which clearly can impact baseline CA125 level. Furthermore, older women who underwent surgical resection are likely to be fundamentally different in terms of functional status and comorbidities compared to those who did not.

However, our study provides new prospective data in chemotherapy toxicity in women 65 or older with ovarian cancer. It is the first study to evaluate the role of CA125 levels in older women and show an association between CA125 with GA variables. To our knowledge, there are no previous studies evaluating the relationship of CA125 level and chemotherapy toxicity in patients of any age. The combination of abnormal CA125 level and the GA toxicity score may be more predictive of chemotherapy toxicity in an ovarian cancer population than the toxicity score alone and merits further evaluation. Future trials will be needed to confirm the potential association between abnormal CA 125 level and chemotherapy toxicity and geriatric variables. If abnormal baseline CA 125 is predictive of higher treatment toxicity, this would be clinically useful to identify patients who would most benefit from a comprehensive GA to detect areas of vulnerability, chemotherapy dose adjustments, and closer monitoring for treatment toxicity. The CARG toxicity score is being explored in several upcoming prospective trials for the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG), which will allow for further investigation of the predictive ability of the toxicity score and CA125 levels.

Footnotes

Disclosure Statement

Cary Gross: Research support, Medtronic Inc; Scientific advisory board, Fair Health Inc. Arti Hurria: Research support, Celgene and GSK; Consulting, Seattle Genetics and GTx

References

- 1.National Center for Health Statistics. Health, United States, 2011: With Special Feature on Socioeconomic Status and Health. Hyattsville, Maryland: 2012. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tew WP, Lichtman S. Ovarian Cancer in Older Women. Semin Oncol. 2008;35:582–589. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2008.08.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Edwards BK, Howe HL, Ries LA, et al. Annual report to the nation on the status of cancer, 1973–1999, featuring implications of age and aging on U.S. cancer burden. Cancer. 2002;94:2766–2792. doi: 10.1002/cncr.10593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yancik R, Ries LA. Cancer in older persons: an international issue in an aging world. Semin Oncol. 2004;31:128–136. doi: 10.1053/j.seminoncol.2003.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tew W, Java J, Chi DS, et al. Treatment outcomes for older women with advanced ovarian cancer: results from a phase III clinical trial (GOG182) J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:15s. (suppl; abstr 5030) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Maas HA, Kruitwagen RF, Lemmens VE, et al. The influence of age and co-morbidity on treatment and prognosis of ovarian cancer: a population-based study. Gynecol Oncol. 2005;97:104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2004.12.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sundararajan V, Hershman D, Grann VR, et al. Variations in the use of chemotherapy for elderly patients with advanced ovarian cancer: a population-based study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:173–178. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.20.1.173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thigpen T, Brady MF, Omura GA, et al. Age as a prognostic factor in ovarian carcinoma. The Gynecologic Oncology Group experience. Cancer. 1993;71:606–614. doi: 10.1002/cncr.2820710218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hightower RD, Nguyen HN, Averette HE, et al. National survey of ovarian carcinoma. IV: patterns of care and related survival for older patients. Cancer. 1994;73:377–383. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19940115)73:2<377::aid-cncr2820730223>3.0.co;2-#. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Eisenhauer EL, Tew W, Levine DA, et al. Response and outcomes in elderly patients with stage IIIC-IV ovarian cancer receiving platinum-taxane chemotherapy. Gynecol Oncol. 2007;106:381–387. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2007.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bast RC, Jr, XUFJ, Yu YH, et al. CA 125: the past and the future. Int J Biol Markers. 1998;13:179–187. doi: 10.1177/172460089801300402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meyer T, Rustin GJ. Role of tumour markers in monitoring epithelial ovarian cancer. Br J Cancer. 2000;82:1535–1538. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2000.1174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nustad K, Bast RC, Jr, Brien TJ, et al. Specificity and affinity of 26 monoclonal antibodies against the CA 125 antigen: first report from the ISOBM TD-1 workshop. International Society for Oncodevelopmental Biology and Medicine. Tumour Biol. 1996;17:196–219. doi: 10.1159/000217982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Riedinger JM, Wafflart J, Ricolleau G, et al. CA 125 half-life and CA 125 nadir during induction chemotherapy are independent predictors of epithelial ovarian cancer outcome: results of a French multicentric study. Ann Oncol. 2006;17:1234–1238. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdl120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rustin GJ, Gennings JN, Nelstrop AE, et al. Use of CA-125 to predict survival of patients with ovarian carcinoma. North Thames Cooperative Group. J Clin Oncol. 1989;7:1667–1671. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1989.7.11.1667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Markman M, Federico M, Liu PY, et al. Significance of early changes in the serum CA-125 antigen level on overall survival in advanced ovarian cancer. Gynecol Oncol. 2006;103:195–198. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2006.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hurria A, Togawa K, Mohile SG, et al. Predicting chemotherapy toxicity in older adults with cancer: a prospective multicenter study. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3457–3465. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.34.7625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kanesvaran R, Li H, Koo KN, Poon D. Analysis of prognosis factors of comprehensive geriatric assessment and development of a clinical scoring system in elderly Asian patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:3620–3627. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.32.0796. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kenemans P, van Kamp GJ, Oehr P, Verstraeten RA. Heterologous double-determinant immunoradiometric assay CA 125 II: reliable second-generation immunoassay for determining CA 125 in serum. Clin Chem. 1993;39:2509–2513. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bast RC, Jr, Klug TL, St John E, et al. A radioimmunoassay using a monoclonal antibody to monitor the course of epithelial ovarian cancer. N Engl J Med. 1983;309:883–887. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198310133091503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Davidson NG, Khanna S, Kirwan PH, Bircumshaw D. Prechemotherapy serum CA125 level as a predictor of survival outcome in epithelial carcinoma of the ovary. Clin Oncol. 1991;3:32–36. doi: 10.1016/s0936-6555(05)81038-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gupta D, Lis CG. Role of CA 125 in predicting ovarian cancer survival – a review of the epidemiological literature. J Ovarian Res. 2009;2:13. doi: 10.1186/1757-2215-2-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Reuben DB, Rubenstein LV, Hirsch SH, Hays RD. Value of functional status as a predictor of mortality: Results of a prospective study. Am J Med. 1992;93:663–669. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(92)90200-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Freyer G, Geay JF, Touzet S, et al. Comprehensive geriatric assessment predicts tolerance to chemotherapy and survival in elderly patients with advanced ovarian carcinoma: a GINECO study. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:1795–1800. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]