Abstract

OBJECTIVES

Psychosocial factors may drive people with irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) to seek health care, but whether psychological factors are causally linked to IBS is controversial. One hypothesis is that IBS is a heterogeneous syndrome comprising two distinct conditions, one psychological and the other biological. However, it is unclear how many people with IBS in the community have little somatization and minimal psychosocial distress. The aim of our study was to estimate the proportion of people with IBS in a representative US community, who have low levels of somatic and psychological symptoms.

METHODS

The cohort comprised subjects from three randomly selected population studies from Olmsted County, Minnesota. All of them filled out a validated gastrointestinal (GI) symptom questionnaire, the Symptom Checklist-90-R (SCL-90-R), and the Somatic Symptom Checklist (SSC) comprising 11 somatic complaint items. Logistic regression models were used to evaluate the associations between somatic symptoms/psychosocial factors and IBS, adjusting for age and gender.

RESULTS

Of the 501 eligible subjects, 461 (92%) provided complete data (mean age = 56 years, 49% female). IBS (Rome II criteria) was associated with both higher SSC and Global Severity Index (GSI of SCL-90-R) scores. Among subjects with high (>75th percentile) SSC scores, 43% reported IBS vs. 10% of those with low (<25th percentile) SSC scores. Among those with high (>60) GSI scores, 23% reported IBS vs. 6% with low (<40) GSI scores. Specifically, none of the IBS subjects had both low SSC and low GSI scores.

CONCLUSIONS

Psychological factors and somatization are strongly associated with IBS in the community. However, IBS may not be related to low psychological distress and/or somatization.

INTRODUCTION

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a very common functional gastrointestinal (GI) disorder that is characterized by abdominal pain or discomfort in association with altered bowel habits (1–3). Although the cause of the disorder remains essentially unknown, IBS is currently conceptualized as a bio-psychosocial disorder with disturbances of motor function, heightened visceral sensitivity, and possibly central nervous system disturbances (4–6). Early life experiences (e.g., abuse), adult stressors (e.g., divorce or bereavement), lack of social support, and other social learning experiences can affect both an individual’s physiological and psychological responses, and may precipitate abdominal distress, as well as psychiatric disorders (4,7–11).

Following landmark studies by Drossman et al. (12) and Whitehead et al. (13), psychosocial factors in IBS have been considered to be related to inducing illness behavior rather than being causally related to the condition itself (14–16). However, there is a considerable body of evidence supporting an association between psychological distress, environmental stress, and functional GI disorders, especially IBS (17–19). In a recent population-based nested case–control study (17), psychosocial distress as measured by the Symptom Checklist-90-R (SCL-90-R) was significantly associated with the presence of a functional GI disorder and was not explained by health-care utilization. Furthermore, in the systemic review, Whitehead et al. (20) reported that between a quarter and a third of patients with IBS meet the criteria for somatization disorder, which is much higher than in the normal population. However, they suggested that the reported association of somatization disorder with IBS represents only a portion of the psychiatric spectrum of somatization, which was defined by very strict criteria. Other studies (21–23) have also observed an excess somatization tendency in outpatients with IBS. It is conceivable that less severe forms of somatization are more common in IBS in the community, but this is poorly documented. In addition, few data regarding the association between IBS and somatization and/or psychosocial distress exist in the community.

Thus, we aimed to estimate the association of somatic symptoms and global psychological distress with IBS status in community subjects, and to evaluate whether the Somatic Symptom Checklist (SSC) provides a valid measure of somatization assessed by the SCL-90-R in patients with or without IBS. We hypothesized that a subgroup of the population with IBS in the community has high somatization and psychosocial distress scores, and the others have normal scores.

METHODS

Subjects

The Olmsted County, Minnesota, population comprises ~120,000 individuals, of which 89% are white; sociodemographically, this community resembles the US white population. Mayo Clinic is the major provider of medical care (24). During any given 4-year period, more than 95% of the local residents will have had at least one local health-care contact (24). Pertinent clinical data are accessible because the Mayo Clinic has maintained, since 1910, extensive indices on the basis of clinical and histological diagnoses and surgical procedures (25). The system was further developed by the Rochester Epidemiology Project, which created similar indices for the records of the other providers of medical care to Olmsted County residents. Therefore, the Rochester Epidemiology Project records linkage system provides essentially an enumeration of the population from which samples can be collected (24). These data resources have been used in a series of investigations into the epidemiology of functional GI disorders (26–30).

Using this system, a series of age- and gender-stratified random samples of residents of Olmsted County were mailed validated self-reported GI symptom questionnaires (Talley BDQ (Bowel Disease Questionnaire) or a close validated derivative). The Talley BDQ has been shown to be a reliable and valid measure of GI symptoms (31). The BDQ consists of GI symptoms that record symptoms of IBS and the SSC, which consists of questions about relevant symptoms and illnesses (e.g., headaches, backaches, lethargy, insomnia), but excludes any GI items, and subjects are instructed to indicate how often each occurred (0 = not a problem to 4 = occurs daily) and how bothersome each was (0 = not a problem to 4 = extremely bothersome when occurs) during the past year, using separate 5-point scales (32,33).

The SCL-90-R is a measure of psychological state (34). It has question items that ask on a 5-point scale, how much a certain problem has bothered the subject over the past 7 days. This allows nine scales to be derived, namely somatization, obsessive-compulsive, interpersonal sensitivity (feelings of personal inadequacy and inferiority), depression, anxiety, hostility, phobic anxiety, paranoid ideation, and psychoticism. The nine raw symptom distress scores are transformed into normative T scores on the basis of samples of non-patient normal males and females (all SCL-90-R subscale scores were transformed into a standardized T score with a mean of 50 and s.d. of 10 as defined by the manual) (34).

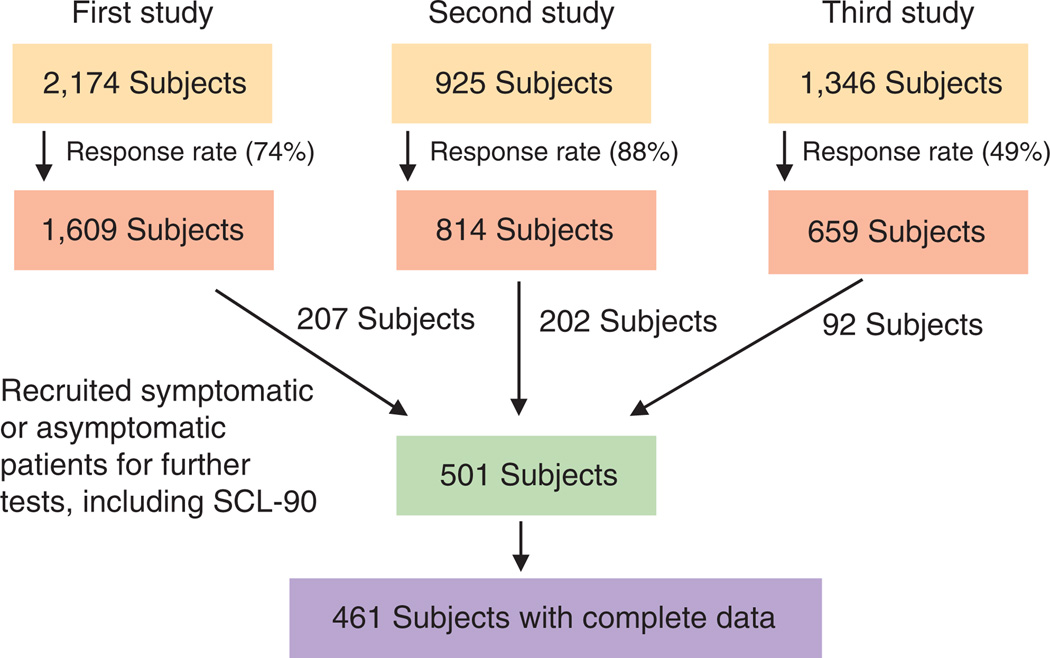

Subjects for this study were pooled from follow-up studies on the basis of three population-based survey studies (17,35–37), in which they filled out both a validated GI symptom questionnaire, which contained the SSC (with 11 somatic complaint items in common across the three surveys), and SCL-90-R. Briefly, in the first population-based study (36,37), the questionnaires were mailed to an age- and gender-stratified random sample of 2,174 eligible residents of Olmsted County aged 65 years and more (response rate 74%). In the second population-based study (17), the questionnaires were mailed to an age-and gender-stratified random sample of residents of Olmsted County aged 20–50 years; a total of 814 (88%) of 925 eligible subjects responded. In the third population-based study (35), an age- and gender-stratified random sample of 1,346 eligible Olmsted County residents, aged 20–80 years were mailed questionnaires; 659 subjects responded (response rate 49%). We have shown in earlier studies (17,35) that there were no clinically important differences in gender, age, or SSC scores between responders and non-responders. Following each of these surveys, specific GI symptomatic and asymptomatic responders were recruited for further outpatient studies, which included having the subjects fill out the SCL-90-R questionnaire (Figure 1). We used these pooled patients, who filled out both a validated GI symptom questionnaire, which contained the SSC, and SCL-90-R, for this study.

Figure 1.

Algorithm of pooled data from three population-based studies.

Therefore, a total of 501 subjects with appropriate research authorization for the use of their medical records for research were pooled from the three earlier follow-up studies obtained from community-based surveys, of which 461 had complete information on all data items examined in this study (Figure 1).

Definition of IBS

IBS was defined by the modified Rome II criteria, namely abdominal discomfort or pain more than six times in the past year that has at least two out of three features, such as: (i) relieved with defecation, (ii) onset associated with more or fewer stool specimens, and (iii) onset associated with looser or harder stool specimens (38). We have applied this definition in earlier studies and shown that it provides data similar to that of a physician interview (27,39).

Statistical analysis

To address the overall aim of this study, logistic regression models (to predict IBS, yes vs. no) were used to evaluate the associations between somatization/psychosocial factors and reporting symptoms consistent with IBS, adjusting for age and gender. The proportion of subjects reporting symptoms consistent with IBS was estimated in subgroups defined by the combination of SSC score categories (25th and 75th percentile cutoffs) and categories of the SCL-90-R Global Severity Index (GSI) scale (defined by the usual cutoffs of 40 and 60, i.e., the standardized score mean (± s.d.) of 50 (± 10). Multiple linear regression models were used to assess the association of the SSC score with SCL-90-R scores adjusting for age, gender, and IBS status. In particular, this analysis assessed the ability of the SSC score to predict the SCL-90-R somatization scale. All P-values were two-sided, and those <0.05 were considered statistically significant. The different analyses each focused on different hypotheses and thus, no adjustment for multiple tests was made.

RESULTS

Demographic features

Of the 461 subjects pooled for this study, 48% were female and the mean (± s.d.) age was 56 years (± 22). Of the 461 subjects, 106 (23%, 95% CI (95% confidence interval): 19–27) met the Rome criteria for a diagnosis of IBS. The demographic features of the subjects with and without IBS are presented in Table 1. No statistically significant associations between IBS status and age, marital status, smoking, alcohol, educational level, or BMI (body mass index) (Table 1) were detected. However, a significant association between IBS status and physician visits for bowel problems in the last year was detected (adjusted for age and gender), with visits more common in subjects with IBS compared with those without IBS.

Table 1.

Distribution of demographic variables in subjects with and without IBS

| Overall, n=461 (%) | IBS, n=106 (%) | Non-IBS, n=355 (%) | P valuea | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean ± s.d. | 56 ± 22 | 47 ± 18 | 58 ± 22 | <0.001 |

| Female, n (%) | 223 (48.4%) | 52 (49.1%) | 171 (48.2%) | 0.87 |

| Married | 312 (67.7%) | 73 (68.9%) | 239 (67.3%) | 0.90 |

| Educational levelb | 0.25 | |||

| Less than high school | 51 (11.1%) | 4 (3.8%) | 47 (13.2%) | |

| High school/some college | 199 (43.2%) | 46 (43.4%) | 153 (43.1%) | |

| College/professional training | 113 (24.5%) | 21 (19.8%) | 92 (25.9%) | |

| Ever smoked | 62 (13.5%) | 20 (18.9%) | 42 (11.8%) | 0.46 |

| Ever used alcohol | 228 (49.5%) | 46 (43.4%) | 182 (51.3%) | 0.008 |

| BMI, mean±s.d. | 27 ± 5 | 27 ± 5 | 27 ± 6 | 0.92 |

| Physician visits in the past year | 96/267 (40.0%) | 39/76 (51.3%) | 57/191 (29.8%) | <0.001 |

BMI, body mass index; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome.

From a logistic regression model to predict IBS, adjusting for age and gender.

A minority failed to provide their information on educational level.

Psychological distress in subjects with and without IBS

The mean scores for the SCL-90-R subscales (Table 2) and those for the 11 somatic complaints of the SSC (Table 3) in subjects with IBS, without IBS, and overall are given in Tables 2 and 3. A significant association of IBS status with all subscale scores of the SCL-90-R was detected (adjusted for age and gender), with numerically greater mean scores observed in subjects with IBS (except for phobic anxiety, Table 2). Although the overall SCL-90-R phobic anxiety scores for IBS and non-IBS subjects were identical (Table 2), there were modest associations between IBS status and phobic anxiety scores within age and gender subgroups (data not shown).

Table 2.

The mean scores of SCL-90-R domains in subjects with and without IBS

| SCL-90-R domain | IBS (n=106) | Non-IBS (n=355) | Overall (n=461) | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Global Severity Index | 54±9 | 49±10 | 50±10 | <0.001 |

| Somatization | 55±8 | 50±10 | 52±10 | <0.001 |

| Obsessive-compulsive | 54±9 | 51±9 | 51±9 | <0.001 |

| Interpersonal sensitivity | 52±10 | 50±9 | 50±9 | 0.01 |

| Depression | 55±9 | 51±10 | 52±10 | <0.001 |

| Anxiety | 50±10 | 47±9 | 48±10 | <0.001 |

| Hostility | 50±8 | 47±8 | 48±8 | 0.008 |

| Phobic anxiety | 49±7 | 49±7 | 49±7 | 0.04 |

| Paranoid ideation | 50±9 | 46±8 | 47±8 | <0.001 |

| Psychoticism | 52±9 | 49±7 | 50±8 | <0.001 |

IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; SCL-90-R, Symptom Checklist-90-R.

From a logistic regression model to predict IBS, adjusting for age and gender.

Table 3.

The mean score of 11 somatic complaints from the SSC in subjects with and without IBS

| SSC items | IBS (n=106) | Non-IBS (n=355) | Overall (n=461) | P valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall SSC score | 0.7±0.5 | 0.5±0.5 | 0.6±0.5 | <0.001 |

| Headache | 1.3±1.0 | 0.7±0.9 | 0.8±1.0 | <0.001 |

| Backache | 1.2±1.1 | 0.9±1.2 | 1.0±1.2 | 0.001 |

| Asthma | 0.1±0.6 | 0.1±0.5 | 0.1±0.6 | 0.73 |

| Insomnia | 1.0±1.2 | 0.7±1.1 | 0.8±1.1 | <0.001 |

| High blood pressure | 0.2±0.6 | 0.2±0.6 | 0.2±0.6 | 0.25 |

| Fatigue | 1.4±1.2 | 0.9±1.1 | 1.1±1.2 | <0.001 |

| General stiffness | 1.1±1.2 | 0.9±1.2 | 1.0±1.2 | 0.002 |

| Heart palpitations | 0.3±0.6 | 0.2±0.6 | 0.2±0.6 | 0.06 |

| Eye pain | 0.4±1.0 | 0.2±0.6 | 0.2±0.7 | 0.002 |

| Dizziness | 0.5±0.9 | 0.4±0.9 | 0.4±0.9 | 0.01 |

| Weakness | 0.3±0.7 | 0.3±0.9 | 0.3±0.9 | 0.26 |

IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; SSC, Somatic Symptom Checklist.

All subscales rated on a 5-point scale anchored by (0) not at all and (4) extremely.

From a logistic regression model to predict IBS, adjusting for age and gender.

Similarly, a significant association of IBS status with the overall SSC scores was detected (adjusted for age and gender) with greater scores observed in IBS subjects (Table 3). In particular, the separate frequency and severity of the overall mean scores were greater in subjects with IBS than in those without IBS (data not shown). In addition, IBS status was significantly associated with each of the somatic items (except asthma, heart palpitations, high blood pressure, and weakness) adjusting for age and gender.

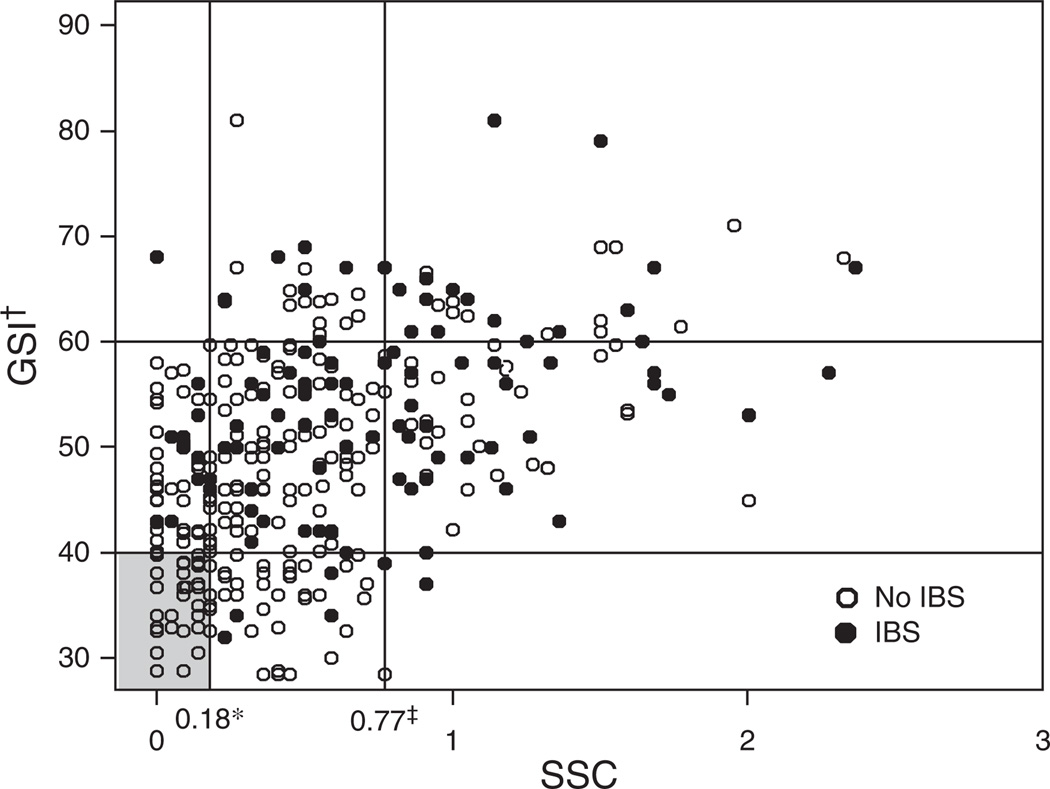

Distribution of the subjects with IBS according to the SSC and GSI scores of the SCL-90-R are shown in Table 4 and in Figure 2. Among subjects with high (>75th percentile) SSC scores, 40% reported IBS vs. 11% of those with low (<25th percentile) SSC scores. Among those with high (>60) GSI scores, 33% reported IBS vs. 8% with low (<40) GSI scores. Specifically, none of the 106 IBS subject had both a low SSC score and a low GSI score as defined above.

Table 4.

Distribution of IBS status according to SSC and GSI domain of the SCL-90-R

| SSC score | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| <0.18 (<25%) | 0.18–0.77 (25–75%) | >0.77 (>75%) | Total | |||||

| GSIa | IBS, n/N | % With IBS | IBS, n/N | % With IBS | IBS, n/N | % With IBS | IBS, n/N | % With IBS |

| <40 | 0/35 | 0 | 5/39 | 13% | 1/2 | 50% | 6/76 | 8% |

| 40–60 | 10/66 | 15% | 37/176 | 21% | 29/70 | 40% | 76/312 | 24% |

| >60 | 1/2 | 50% | 7/30 | 23% | 16/41 | 39% | 24/73 | 33% |

| Total | 11/103 | 11% | 49/245 | 20% | 46/113 | 40% | 106/461 | 23% |

IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; GSI, Global Severity Index; SCL-90-R, Symptom Checklist-90-R; SSC, Somatic Symptom Checklist.

Standardized T scores with a mean of 50 and s.d. of 10.

Figure 2.

Distribution of subjects with and without irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) according to the Somatic Symptom Checklist (SSC) and the Global Severity Index (GSI) of SCL-90-R. * 0.18 Is the 25th percentile of SSC distribution; ‡ 0.77 Is the 75th percentile of SSC distribution; † GGSI scores were transformed into standardized T scores with a mean of 50 and s.d. of 10.

Predictors of IBS

The ability of the each of the somatic complaints included in the SSC and that of each subscale of the SCL-90-R to predict IBS vs. non-IBS is summarized in Table 5. Logistic regression analysis indicated that all of the SCL-90-R subscales (except phobic anxiety) were significantly (P < 0.05) associated with IBS relative to non-IBS (adjusting for age, gender, educational level, marital status, smoking, alcohol use, and BMI, Table 5). The community subjects with greater somatization scores had greater odds for IBS (OR (odds ratio) 2.2 per unit, 95% CI: 1.2–3.8). Of the 11 somatic complaints, a higher score for 7 items (but not asthma, high blood pressure, and dizziness) was associated with greater odds for reporting IBS compared with the non-IBS group (Table 5).

Table 5.

Predictors of reporting IBS vs. non-IBS, adjusting for age, gender, educational level, marital status, smoking, alcohol use, and body mass index

| Odds ratio (95% CI) | P value | |

|---|---|---|

| SSC score (per unit) | 2.2 (1.2–3.8) | <0.001 |

| Headache | 1.69 (1.25, 2.28) | <0.001 |

| Backache | 1.39 (1.07, 1.81) | 0.002 |

| Asthma | 1.18 (0.76, 1.84) | 0.45 |

| Insomnia | 1.57 (1.20, 2.05) | <0.001 |

| High blood pressure | 1.10 (0.53, 2.26) | 0.80 |

| Fatigue | 2.06 (1.55, 2.74) | <0.001 |

| General stiffness | 1.50 (1.13, 2.00) | 0.005 |

| Heart palpitations | 1.64 (1.02, 2.62) | 0.04 |

| Eye pain | 1.59 (1.10, 2.30) | 0.01 |

| Dizziness | 1.37 (0.94, 1.98) | 0.10 |

| Weakness | 1.43 (0.99, 2.07) | 0.06 |

| SCL-90-R (per unit) | ||

| Global Severity Index | 1.09 (1.05, 1.13) | <0.001 |

| Somatization | 1.10 (1.06, 1.15) | <0.001 |

| Obsessive-compulsive | 1.08 (1.04, 1.12) | <0.001 |

| Interpersonal sensitivity | 1.04 (1.01, 1.07) | 0.01 |

| Depression | 1.07 (1.04, 1.11) | <0.001 |

| Anxiety | 1.06 (1.03, 1.10) | <0.001 |

| Hostility | 1.05 (1.01, 1.09) | 0.01 |

| Phobic anxiety | 1.05 (1.00, 1.10) | 0.07 |

| Paranoid ideation | 1.06 (1.02, 1.100 | 0.001 |

| Psychoticism | 1.08 (1.04, 1.12) | <0.001 |

CI, confidence interval; IBS, irritable bowel syndrome; SCL-90-R, Symptom Checklist-90-R; SSC, Somatic Symptom Checklist.

Correlations between SSC and SCL-90-R

In the total study sample, a univariate analysis revealed that the SSC scores were positively correlated with somatization, depression, anxiety, and the GSI subscale of the SCL-90-R (all P < 0.05) (Table 6). Furthermore, in multiple linear regression models, adjusting for age, gender, and IBS status, the overall SSC score was most strongly correlated with the somatization subscale, with a partial r2 value of 31%, whereas, e.g., for the GSI score, the partial r2 of the SSC score was 17%.

Table 6.

Correlation between SSC scores and SCL-90-R domains

| SCL-90-R domain |

SSC scores | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Pearson | Spearman | P value | |

| Global Severity Index | 0.47 | 0.48 | <0.001 |

| Somatization | 0.60 | 0.57 | <0.001 |

| Obsessive-compulsive | 0.34 | 0.35 | <0.001 |

| Interpersonal sensitivity | 0.29 | 0.27 | <0.001 |

| Depression | 0.38 | 0.40 | <0.001 |

| Anxiety | 0.33 | 0.30 | <0.001 |

| Hostility | 0.16 | 0.14 | 0.002 |

| Phobic anxiety | 0.34 | 0.16 | <0.001 |

| Paranoid ideation | 0.19 | 0.18 | <0.001 |

| Psychoticism | 0.27 | 0.26 | <0.001 |

SCL-90-R; Symptom Checklist-90-R; SSC, Somatic Symptom Checklist.

DISCUSSION

In this population-based study, we assessed the association of somatic and psychological symptoms with IBS status, and examined predictors of IBS for each of the items in the SSC and for each SCL-90 subscale. The significant associations corresponded to higher levels of psychological distress and somatization in patients with IBS. Interestingly, we did not find any community subject with low psychological distress and somatic complaints scores to have IBS. It is noted that, headaches, backaches, insomnia, fatigue, general stiffness, heart palpitations, and eye pain were all individually associated with IBS status in the general population on the basis of the Rome criteria.

It is well known that psychological and psychiatric comorbidity is common among patients with IBS (17,20,40). The American Gastroenterological Association technical review on IBS (16) reported that the prevalence of a psychiatric disorder ranges from 40 to more than 90% among patients with IBS referred to tertiary care centers, but argued that these studies overestimated the true prevalence of psychosocial disturbance in patients with IBS because psychological factors influence whether patients consult physicians. Several studies carried out in volunteers (12,13,41) reported that persons with IBS, who do not see physicians, are psychologically similar to those without bowel complaints. In contrast, more recent population studies (42–45) have suggested that the earlier volunteer non-population-based studies may have been biased, but this view is still controversial (16). Koloski et al. (19) reported that psychiatric diagnoses, neuroticism, more highly threatening life event stress, an external locus of control, and ineffectual coping styles were significantly associated with having a diagnosis of IBS and/or dyspepsia, and somatization was independently associated with IBS in a random population sample from Sydney, Australia. Similarly, in a nested case–control study, Locke et al. (17) observed that psychological distress as measured by SCL-90-R was associated with functional GI disorders, and this observation was not explained by referral bias; others have come to similar conclusions (44,45). Sayuk et al. (46) reported that a higher burden of the current somatic symptoms was a strong predictor of a functional bowel disease in outpatients presenting with GI complaints. However, the burden of psychological distress in IBS remains unclear in the community, as studies have failed to document how many IBS sufferers are totally free of psychological comorbidity. Our study has shown in a general population sample that higher somatization and higher psychosocial distress were both associated with IBS, and more importantly no IBS patient had both a low somatic symptom score and a low psychological distress score. The definition of the normal range of SCL-90-R scores was based on commercially used cutoff definitions that are widely accepted (34,47). For the somatization score, the choice of the 25th and 75th percentile cutoffs was somewhat arbitrary but intuitively reasonable, and was intended to give a sufficient number of subjects in each of the “cells”. We postulate that high somatization and psychosomatic distress levels represent true risk factors for IBS in the community, although our data do not establish causality. Psychological distress is also an important factor in IBD (inflammatory bowel disease) (47,48). Sewitch et al. (47) studied the psychosocial distress in 200 patients with IBD from tertiary care settings. They showed that patients with IBD had higher levels of psychological distress than controls; the mean GSI score of patients with IBD was 57.1 (s.d. = 9.4). These results are comparable with the findings in this study, in which the mean GSI score of community subjects with IBS was 54 (s.d. = 9).

Of the 11 somatic complaints included from the SSC, we found that 7 items were significantly associated with IBS independent of age, gender, education level, marital status, smoking, alcohol use, and BMI. Whitehead et al. (40) reported that 48 of 51 symptom-based diagnoses were significantly more common in patients with IBS vs. that in controls, including headache, back pain, sleep disorder, muscle weakness, pelvic pain, and blurred vision. Although the finding of higher somatic complaints in IBS vs. that in controls was similar to our results, they did not find any unique associations between these symptom-based diagnoses and IBS. However, our study suggests that the majority of the somatic complaints are independently associated with IBS. It is noted that, the study of Whitehead et al. (40) was not population-based, the subjects were recruited from a primary health-care system, and the findings were based on an administrative database rather than on a survey or other direct methods of measuring somatic symptoms.

Recently, there has been an increasing interest in overhauling the classification of somatoform disorders in the diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (DSM) classification, including adding a broad spectrum of bodily symptom complaints (IBS, chronic fatigue syndrome, fibromyalgia, and chronic benign pain syndrome) (49–51). Fink et al. (49) showed that functional somatic symptoms could be grouped into three main symptom clusters, namely GI, CP (cardio-pulmonary), and MS (musculoskeletal). In addition, they found significantly inter-correlated correlation coefficients of 0.40–0.45 (Spearman’s rho) between a number of the symptoms from CP, GI, and MS symptom groups, and suggested that the three functional somatic syndromes are all different representations of a common latent phenomenon. Our study also showed that the eight somatic complaint items were associated with IBS, raising the possibility that a subset with IBS in the community may not have a specific entity but are a part of a general syndrome of bodily distress.

The strengths of this study include the investigation of a pooled sample that was obtained from random population-based samples that were not seeking health care for their bowel complaints. This should have minimized selection bias, even though one of limitations of this study is that we were required to use the data from subjects who had completed both the SSC and SCL-90-R in our earlier population-based studies (17,27,35,36). However, we have shown, after a careful review, that there were no systematic differences between individuals who participated and non-participants, including in terms of age, gender, or SSC score in our earlier studies (17,35,36). We did not study subjects at the onset of their symptoms and thus, cannot discriminate factors important in the initiation of symptoms from those responsible for symptom persistence. Thus, we cannot address causality from this study; the study of a prevalent case does not allow for the assessment of cause and effect. We do not have information regarding which subject with IBS acquired the condition after infection, although we believe this is likely to be the minority (52,53). However, our data do suggest that psychological factors are more important in community subjects with IBS than has been anticipated. Finally, the current data cannot be generalized to the entire US population because the racial composition of this community is predominantly white (54).

We conclude from this population-based study that psychological factors are strongly associated with IBS in the community; notably, somatization is significantly associated with IBS independent of age, gender, education level, marital status, smoking, alcohol use, and BMI. Interestingly, we did not find an IBS community subject who was free of psychological distress and somatic symptoms. These data suggest that psychological factors may be more strongly associated with IBS than expected. Further prospective studies evaluating the potential causal role of psychological factors in IBS are warranted covering both genetic and environmental determinants.

Study Highlights.

WHAT IS CURRENT KNOWLEDGE

-

✓

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is currently conceptualized as a biopsychosocial disorder with disturbances of motor function, heightened visceral sensitivity, and possible central nervous system disturbances.

-

✓

Psychosocial factors have been considered to drive patients to seek health care instead of being causally related to the condition itself.

-

✓

It is unknown how many people with IBS in the community have less somatization and minimal psychosocial distress.

WHAT IS NEW HERE

-

✓

Psychological factors, particularly somatization, are strongly associated with IBS in the community.

-

✓

No subject in the community with IBS was free of psychological distress and/or somatic symptoms.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank Susan M. Schlichter for her assistance in the preparation of this paper.

Financial support: This study was made possible in part by the Rochester Epidemiology Project (Grant R01-AR30582 from the National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases).

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Guarantor of the article: Nicholas J. Talley, MD, PhD.

Specific author contributions: Design, analysis, and/or writing or revision of the paper: Rok Seon Choung, G. Richard Locke III, Alan R. Zinsmeister, and Nicholas J. Talley; statistical analysis and revision of the paper: Alan R. Zinsmeister and Cathy D. Schleck.

Potential competing interests: Talley and the Mayo Clinic have licensed the Talley Bowel Disease Questionnaire.

REFERENCES

- 1.Longstreth GF. Definition and classification of irritable bowel syndrome: current consensus and controversies. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 2005;34:173–187. doi: 10.1016/j.gtc.2005.02.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thompson WG. Irritable bowel syndrome: pathogenesis and management. Lancet. 1993;341:1569–1572. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90705-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zighelboim J, Talley NJ. What are functional bowel disorders? Gastroenterology. 1993;104:1196–1201. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(93)90293-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Levy RL, Olden KW, Naliboff BD, et al. Psychosocial aspects of the functional gastrointestinal disorders. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:1447–1458. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mayer EA, Naliboff BD, Chang L, et al. Stress and irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2001;280:G519–G524. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.2001.280.4.G519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monnikes H, Tebbe JJ, Hildebrandt M, et al. Role of stress in functional gastrointestinal disorders. Evidence for stress-induced alterations in gastrointestinal motility and sensitivity. Dig Dis. 2001;19:201–211. doi: 10.1159/000050681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Talley NJ, Fett SL, Zinsmeister AR. Self-reported abuse and gastrointestinal disease in outpatients: association with irritable bowel-type symptoms. Am J Gastroenterol. 1995;90:366–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Delvaux M, Denis P, Allemand H. Sexual abuse is more frequently reported by IBS patients than by patients with organic digestive diseases or controls. Results of a multicentre inquiry. French Club of Digestive Motility. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 1997;9:345–352. doi: 10.1097/00042737-199704000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ali A, Toner BB, Stuckless N, et al. Emotional abuse, self-blame, and self-silencing in women with irritable bowel syndrome. Psychosom Med. 2000;62:76–82. doi: 10.1097/00006842-200001000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Whitehead WE, Crowell MD, Robinson JC, et al. Effects of stressful life events on bowel symptoms: subjects with irritable bowel syndrome compared with subjects without bowel dysfunction. Gut. 1992;33:825–830. doi: 10.1136/gut.33.6.825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bennett EJ, Tennant CC, Piesse C, et al. Level of chronic life stress predicts clinical outcome in irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 1998;43:256–261. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drossman DA, McKee DC, Sandler RS, et al. Psychosocial factors in the irritable bowel syndrome. A multivariate study of patients and nonpatients with irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:701–708. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(88)80017-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Whitehead WE, Bosmajian L, Zonderman AB, Schuster MM, et al. Symptoms of psychologic distress associated with irritable bowel syndrome. Comparison of community and medical clinic samples. Gastroenterology. 1988;95:709–704. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(88)80018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Whitehead WE, Crowell MD. Psychologic considerations in the irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterol Clin North Am. 1991;20:249–267. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Smith RC, Greenbaum DS, Vancouver JB, et al. Psychosocial factors are associated with health care seeking rather than diagnosis in irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1990;98:293–301. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(90)90817-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Drossman DA, Camilleri M, Mayer EA, et al. AGA technical review on irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 2002;123:2108–2103. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.37095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Locke GR, III, Weaver AL, Melton LJ, III, et al. Psychosocial factors are linked to functional gastrointestinal disorders: a population based nested case-control study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2004;99:350–357. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2004.04043.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Talley NJ, Boyce PM, Jones M. Predictors of health care seeking for irritable bowel syndrome: a population based study. Gut. 1997;41:394–398. doi: 10.1136/gut.41.3.394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koloski NA, Boyce PM, Talley NJ. Somatization an independent psychosocial risk factor for irritable bowel syndrome but not dyspepsia: a population-based study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2006;18:1101–1109. doi: 10.1097/01.meg.0000231755.42963.c6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Whitehead WE, Palsson O, Jones KR. Systematic review of the comorbidity of irritable bowel syndrome with other disorders: what are the causes and implications? Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1140–1156. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whorwell PJ, McCallum M, Creed FH, et al. Non-colonic features of irritable bowel syndrome. Gut. 1986;27:37–40. doi: 10.1136/gut.27.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Maxton DG, Morris J, Whorwell PJ. More accurate diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome by the use of ‘non-colonic’ symptomatology. Gut. 1991;32:784–786. doi: 10.1136/gut.32.7.784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choung RS, Locke GR, III, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Alternating bowel pattern: what do people mean? Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2006;23:1749–1755. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2006.02953.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Melton LJ., III History of the Rochester Epidemiology Project. Mayo Clin Proc. 1996;71:266–274. doi: 10.4065/71.3.266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kurland LT, Molgaard CA. The patient record in epidemiology. Sci Am. 1981;245:54–63. doi: 10.1038/scientificamerican1081-54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Schleck CD, et al. Dyspepsia and dyspepsia subgroups: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:1259–1268. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Van Dyke C, et al. Epidemiology of colonic symptoms and the irritable bowel syndrome. Gastroenterology. 1991;101:927–934. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90717-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Talley NJ, Phillips SF, Melton J, III, et al. A patient questionnaire to identify bowel disease. Ann Intern Med. 1989;111:671–674. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-111-8-671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Talley NJ, O’Keefe EA, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms in the elderly: a population-based study. Gastroenterology. 1992;102:895–901. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(92)90175-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Talley NJ, Weaver AL, Zinsmeister AR, et al. Onset and disappearance of gastrointestinal symptoms and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Am J Epidemiol. 1992;136:165–177. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116483. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Talley NJ, Phillips SF, Wiltgen CM, et al. Assessment of functional gastrointestinal disease: the bowel disease questionnaire. Mayo Clin Proc. 1990;65:1456–1479. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)62169-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Attanasio V, Andrasik F, Blanchard EB, et al. Psychometric properties of the SUNYA revision of the psychosomatic symptom checklist. J Behav Med. 1984;7:247–257. doi: 10.1007/BF00845390. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Locke GR, III, Zinsmeister AR, Talley NJ, et al. Risk factors for irritable bowel syndrome: role of analgesics and food sensitivities. Am J Gastroenterol. 2000;95:157–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2000.01678.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Derogatis LR, Rickels K, Rock AF. The SCL-90 and the MMPI: a step in the validation of a new self-report scale. Br J Psychiatry. 1976;128:280–289. doi: 10.1192/bjp.128.3.280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Castillo EJ, Camilleri M, Locke GR, et al. A community-based, controlled study of the epidemiology and pathophysiology of dyspepsia. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;2:985–996. doi: 10.1016/s1542-3565(04)00454-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Evans JM, Fleming KC, Talley NJ, et al. Relation of colonic transit to functional bowel disease in older people: a population-based study. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:83–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb01018.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Talley NJ, Fleming KC, Evans JM, et al. Constipation in an elderly community: a study of prevalence and potential risk factors. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:19–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Saito YA, Talley NJ, L JM, et al. The effect of new diagnostic criteria for irritable bowel syndrome on community prevalence estimates. Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2003;15:687–694. doi: 10.1046/j.1350-1925.2003.00441.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Talley NJ, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ., III Irritable bowel syndrome in a community: symptom subgroups, risk factors, and health care utilization. Am J Epidemiol. 1995;142:76–83. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a117548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Whitehead WE, Palsson OS, Levy RR, et al. Comorbidity in irritable bowel syndrome. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:2767–2776. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2007.01540.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Sandler RS, Drossman DA, Nathan HP, et al. Symptom complaints and health care seeking behavior in subjects with bowel dysfunction. Gastroenterology. 1984;87:314–318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Koloski NA, Boyce PM, Talley NJ. Is health care seeking for irritable bowel syndrome and functional dyspepsia a socially learned response to illness? Dig Dis Sci. 2005;50:153–162. doi: 10.1007/s10620-005-1294-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koloski NA, Talley NJ, Boyce PM. Epidemiology and health care seeking in the functional GI disorders: a population-based study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2002;97:2290–2299. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2002.05783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Talley NJ, Boyce PM, Jones M. Is the association between irritable bowel syndrome and abuse explained by neuroticism? A population based study. Gut. 1998;42:47–53. doi: 10.1136/gut.42.1.47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Herschbach P, Henrich G, von Rad M. Psychological factors in functional gastrointestinal disorders: characteristics of the disorder or of the illness behavior? Psychosom Med. 1999;61:148–153. doi: 10.1097/00006842-199903000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sayuk GS, Elwing JE, Lustman PJ, et al. High somatic symptom burdens and functional gastrointestinal disorders. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;5:556–562. doi: 10.1016/j.cgh.2006.11.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sewitch MJ, Abrahamowicz M, Bitton A, et al. Psychological distress, social support, and disease activity in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96:1470–1479. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2001.03800.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mikocka-Walus AA, Turnbull DA, Moulding NT, et al. Controversies surrounding the comorbidity of depression and anxiety in inflammatory bowel disease patients: a literature review. Inflamm Bowel Dis. 2007;13:225–234. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fink P, Toft T, Hansen MS, et al. Symptoms and syndromes of bodily distress: an exploratory study of 978 internal medical, neurological, and primary care patients. Psychosom Med. 2007;69:30–39. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31802e46eb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kroenke K. Physical symptom disorder: a simpler diagnostic category for somatization-spectrum conditions. J Psychosom Res. 2006;60:335–339. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychores.2006.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fink P, Rosendal M. Recent developments in the understanding and management of functional somatic symptoms in primary care. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2008;21:182–188. doi: 10.1097/YCO.0b013e3282f51254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Longstreth GF, Hawkey CJ, Mayer EA, et al. Characteristics of patients with irritable bowel syndrome recruited from three sources: implications for clinical trials. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2001;15:959–964. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2001.01010.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barbara G, Stanghellini V, Cremon C, et al. Almost all irritable bowel syndromes are post-infectious and respond to probiotics: controversial issues. Dig Dis. 2007;25:245–248. doi: 10.1159/000103894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Melton LJ., III The threat to medical-records research. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1466–1470. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199711133372012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]