Abstract

Purpose

The need to improve chemotherapeutic efficacy against head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC) is well recognized. In this study, we investigated the potential of targeting the established tumor vasculature in combination with chemotherapy in head and neck cancer.

Methods

Experimental studies were carried out in multiple human HNSCC xenograft models to examine the activity of the vascular disrupting agent (VDA) 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid (DMXAA) in combination with chemotherapy. Multimodality imaging (magnetic resonance imaging, bioluminescence) in conjunction with drug delivery assessment (fluorescence microscopy), histopathology and microarray analysis was performed to characterize tumor response to therapy. Long-term treatment outcome was assessed using clinically-relevant end points of efficacy.

Results

Pretreatment of tumors with VDA prior to administration of chemotherapy increased intratumoral drug delivery and treatment efficacy. Enhancement of therapeutic efficacy was dependent on the dose and duration of VDA treatment but was independent of the chemotherapeutic agent evaluated. Combination treatment resulted in increased tumor cell kill and improvement in progression-free survival and overall survival in both ectopic and orthotopic HNSCC models.

Conclusion

Our results show that preconditioning of the tumor microenvironment with an antivascular agent primes the tumor vasculature and results in enhancement of chemotherapeutic delivery and efficacy in vivo. Further investigation into the activity of antivascular agents in combination with chemotherapy against HNSCC is warranted.

Keywords: head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, angiogenesis, vascular targeting, vascular disrupting agents

INTRODUCTION

Head and neck squamous cell carcinomas (HNSCC) represent a biologically diverse group of neoplasms that vary in their clinical presentation and aggressiveness (1). While the addition of chemotherapy to loco-regional treatment provides clinical benefit, tumor recurrence remains a major therapeutic hurdle (2). Additionally, head and neck cancer patients often develop substantial treatment-related toxicities with debilitating aesthetic and functional consequences. It is therefore important to evaluate and develop novel targeted therapeutic strategies for head and neck cancers.

Tumor angiogenesis is a critical determinant of malignant transformation and progression of most solid tumors including HNSCC (3, 4). In addition to serving as the primary source of oxygen and nutrients to the growing tumor mass, the vascular system also serves as a conduit for drug delivery. Tumor vascularity has previously been shown to affect response to chemotherapy and potentially predict treatment outcome in head and neck cancer (5, 6). Based on this knowledge, we hypothesized that selective disruption of the tumor vasculature could be of therapeutic benefit in HNSCC. We have tested this hypothesis using the small molecule tumor vascular disrupting agent (VDA), 5, 6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid (DMXAA; ASA404) (7). Our previous preclinical studies have demonstrated that (i) as single agents, VDAs exhibit moderate antitumor activity against HNSCC evidenced by tumor growth inhibition and delayed tumor regrowth, (ii) functional alterations in tumor vasculature following VDA therapy can be successfully detected using clinically-relevant non-invasive imaging techniques (e.g. magnetic resonance imaging, ultrasound), and, (iii) early vascular response to VDA therapy correlates with treatment outcome (8, 9). Since VDAs compromise blood flow to tumors, it is generally believed that chemotherapy should be administered prior to VDA treatment. As a result, a majority of preclinical studies investigating the efficacy of VDAs in the combination setting have been carried out using this sequence (chemotherapy prior to VDA administration). Phase II and Phase III clinical trials of the VDA DMXAA have also employed this sequence with patients receiving the VDA following administration of chemotherapy (10, 11).

It is well recognized that tumor response to VDAs is characterized by an early increase in endothelial permeability and extravasation of plasma and macromolecules which subsequently contributes to vascular stasis and shutdown (12, 13). Given this temporal nature of vascular response to VDA therapy (14-16), we hypothesized that pretreatment of tumors with a VDA could lead to priming of the tumor vasculature within a few hours of treatment facilitating increased drug delivery and conditioning of the tumor microenvironment for subsequent chemotherapy. To test this hypothesis, we examined the interaction between tumor-VDAs and chemotherapy against ectopic (subcutaneous) and orthotopic FaDu tumors and HNSCC xenografts established from surgical tumor tissue. Using non-invasive multimodality imaging in conjunction with drug delivery, histopathology and gene expression profiling, we characterized the functional and molecular changes occurring within the tumor microenvironment following VDA therapy and evaluated the therapeutic efficacy of combined VDA and chemotherapy against head and neck cancer.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Tumor models

Experimental studies were carried out using eight-to-twelve week old severe combined immunodeficient (SCID) mice bred in house within the Laboratory Animal Resource at Roswell Park Cancer Institute (RPCI) or athymic nude mice (foxn1/nu, Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN). Animals were housed in micro isolator cages, provided standard chow/water and maintained on 12-hour light/dark cycles in an HEPA-filtered environment. Studies were carried out using the FaDu head and neck carcinoma cell line (ATCC; Manassas, VA) and HNSCC xenografts derived from surgical tumor tissue. We have previously described the procedures for establishing ectopic (subcutaneous) and orthotopic FaDu tumors and patient tumor-derived HNSCC xenografts (9, 17). Tissue specimens were obtained from patients following written consent and under a research protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board and the research ethics committee. All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at RPCI.

Drugs

DMXAA powder (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) was dissolved in phosphate-buffered saline (1x PBS; pH = 7.4) at a concentration of 5 mg/ml and administered at 20 or 25 mg/kg by intraperitoneal injection. Irinotecan (Camptosar®; CPT-11), Docetaxel (Taxotere®) and Doxorubicin (Adriamycin®) was obtained from the pharmacy at Roswell Park Cancer Institute. Irinotecan was administered at a dose of 50 mg/kg by intravenous injection. Docetaxel was reconstituted in PBS and administered at a dose of 10 or 20 mg/kg by intraperitoneal injection. Doxorubicin was administered intravenously at a dose of 30 mg/kg.

Fluorescence microscopy

Drug delivery assessment was performed using the anthracycline Doxorubicin. Fluorescence microscopy was utilized to quantify the autofluorescence of the drug. For these studies, mice bearing subcutaneous FaDu tumors received either doxorubicin (30 mg/kg, i.v.) or DMXAA (25 mg/kg, i.p.) 1 hour prior to Doxorubicin. One hour post administration of Doxorubicin, tumors were excised, snap frozen and ~10 μm thick frozen sections were cut. Five maximum intensity projections were acquired using a Leica confocal microscope using identical acquisition parameters as described previously (18). All images were processed using LAS AF Lite (Leica, Germany) and Analyze 7.0 (Analyze Direct, Overland Park, KS).

Bioluminescence Imaging

Orthotopic tumor growth of luciferase-transfected FaDu cells (lentiviral firefly luciferase construct; Genecopoeia Inc., Rockville, Maryland) was monitored by bioluminescence imaging using the Xenogen IVIS imaging system (Caliper Life Sciences, Alameda, CA). D-Luciferin (Gold Biotechnologies, St. Louis, MO) was administered (75 mg/kg; s.c.) prior to imaging. Approximately 1 minute post injection, mice were serial imaged for 15 minutes, with 1 minute intervals. The imaging parameters were: medium binning, 1 f/stop, blocked excitation filter and an open emission filter, with the field of view set to 22 cm to image 3 mice at once. Image processing and analysis were carried out using Living Image software (Caliper Life Sciences, Alameda, CA).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging

Experimental MRI examinations were conducted in a 4.7T/33-cm horizontal bore magnet (GE NMR Instruments, Fremont, CA) equipped with AVANCE digital electronics (Bruker Biospec, Paravision 3.0.2; Bruker Medical Inc., Billerica, MA), a removable gradient coil insert (G060) generating a maximum field strength of 950 mT/m and a custom-designed 35-mm RF transmit-receive coil. Animals were secured in a form-fitted, MR compatible sled (Dazai Research Instruments, Toronto, Canada) equipped with temperature and respiratory monitoring sensors. Animal body temperature was maintained at 37°C during imaging using an air heater system (SA Instruments Inc., Stony Brook, NY), and automatic temperature feedback was initiated through thermocouples in the sled. A phantom containing 0.15 mM gadopentetate dimeglumine (Gd-DTPA; Magnevist, Berlex Laboratories, Wayne, NJ) was used for monitoring changes in noise and system performance. Data acquisition consisted of initial localizer scans followed by T2-weighted (T2W) spin echo images with the following parameters: Field of view (FOV) =3.20 × 3.20 cm, matrix (MTX) = 256 × 192, slice thickness = 1 mm, NEX = 4, TR = 2500 ms, TEeff = 41.0 ms, RARE/Echoes= 8/8. T1-weighted (T1W) spin echo images were acquired with the following parameters: Field of view (FOV) =3.20 × 3.20cm, matrix (MTX) = 128 × 128, slice thickness = 1.00 mm, NEX = 2, TR = 404ms, TEeff = 7.8 ms. Following image acquisition, raw image sets were transferred to a processing workstation and converted into Analyze™ format (AnalyzeDirect, version 7.0; Overland Park, KS). All post processing of imaging data was carried out in Analyze™ and MATLAB (Mathworks Inc., Natick, MA). A region of interest (ROI) was manually traced around the entire tumor area on each tumor slice excluding the surrounding skin. Tumor volume was calculated by measuring the cross sectional area on each slice and multiplying their sum by the slice thickness. Serial T1-weighted images were acquired before and after administration of albumin-GdDTPA (0.1 mmol/kg, University of California, San Francisco, CA). Relative blood volume estimates were obtained from tumor enhancement calculated from the normalized signal intensity values (8, 19).

Immunohistochemistry and histology

Tumors were excised from control and treated animals and placed in formalin (BD Biosciences, San Diego, CA) for immunohistochemical and histologic evaluation. Tumor sections were immunostained for the proliferation marker, Ki-67 (RM-9106-S1; Clone SP6; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Fremont, CA). Paraffin sections cut at 4μm were placed on charged slides, and dried at 60°C for one hour. Slides were cooled to room temperature, deparaffinized in three changes of xylene, and rehydrated using graded alcohols. Endogenous peroxidase was quenched with aqueous 3% H2O2 for 10 minutes and washed with PBS/T. Slides were loaded on a Dako autostainer and serum free protein block (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) was applied for 5 minutes, blown off, antibodies were applied for one hour, and rinsed with PBS/T. For Ki-67 staining, biotinylated goat anti-rabbit IgG (Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA) secondary antibody was applied for 30 minutes, followed by the Elite ABC Kit (Vectastain, Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA), also for 30 minutes, and the DAB chromogen (Dako, Carpinteria, CA) for 5 minutes. Slides were counterstained with Harris hematoxylin (Poly Scientific, Bayshore, NY). Slides containing histologic sections of control and treated tumors were scanned and digitized using the Scanscope XT system (Aperio, Vista, CA) and images of whole tumor sections were captured using the ImageScope software. Areas of necrosis and Ki67 positivity were traced using the medical imaging software Analyze 7.0 (AnalyzePC; AnalyzeDirect, OverlandPark, KS) and reported as a percentage of the whole tumor area. Values are reported as mean ± standard error. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) with multiple comparison (Tukey test) was used to compute statistical significance (p<0.05) between groups.

Therapeutic response assessment

For animals bearing subcutaneous tumors, caliper measurements were made to calculate tumor volume (mm3) using the formula, V = ½(L × W2), where L is the longest axis, and W – axis perpendicular to L. Measurements were made 2 to 3 times a week and plotted as change in tumor volume over time. All treatments were initiated using experimental groups with matched tumor volumes. Tumor-doubling times were calculated from change in tumor volume over time using an exponential growth equation and differences analyzed for statistical significance using a one-way ANOVA in GraphPad Prism (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Animals were euthanized when tumor burden reached the threshold for euthanasia as per institutional protocols. Animals with no visible/palpable tumor at the end of the 60-day period were considered to be cured. For mice bearing orthotopic head and neck tumors, tumor volume was calculated from multislice T2W MR images acquired once a week over a period of 4-8 weeks. Disease progression was defined as a doubling in tumor volume of orthotopic tumors on MRI exams and progression free survival (PFS) curves were generated using this criterion (20). Kaplan-Meier survival curves were generated and differences in survival analyzed using the log-rank test.

RNA extraction

Total RNA isolation was carried out using a MagMAX™ Express-96 Magnetic Particle Processor and the MagMAX™-96 Total RNA Isolation Kit according to the manufacturer's protocol. RNA concentration was quantified by fluorescence measurement using SYBR Green II (Invitrogen, Life Technologies, Grand Island, NY) and a Synergy HT reader (BioTek, Winooski, VT). The RNA quality was characterized by the quotient of the 28S to 18S ribosomal RNA electropherogram peaks using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer.

Amplification, labeling and BeadChip hybridization of RNA samples

The Illumina Total Prep RNA Amplification Kit (Ambion, Grand Island, NY, USA) was used to transcribe 200ng of total RNA according to the manufacture's recommendation(s). Approximately, 700ng of cRNA was hybridized at 58°C for 16 hours to Illumina HumanHT-12 v4 Expression BeadChips (Illumina Inc. San Diego, CA) and scanned using an Illumina Bead Array Reader and Bead Scan Software.

Data processing

Data processing was performed with Genome Studio version 2011.1 and the R Language and Environment for Statistical Computing (R) 2.13.2 in combination with Bioconductor 2.10 (21), The Bioconductor lumi package (22) was used for quality control. The normalizations executed by Illumina Genome Studio were all applied to the expression values on the original scale. If background adjustment was performed, we used the standard background correction offered by Bead Studio (bg_*). Data was subsequently normalized using variance stabilization (VSN) and quantile normalization across samples using the functions in the ‘lumi’ Bioconductor (available at www.bioconductor.org).

Differentially expressed genes were selected using a modified version of the Rank Product procedure (Rank Prod) and allows detection of differentially expressed genes by non-parametric ranking genes according to the difference in abundance between control and drug treatment samples. After calculating ‘control/ treatment ratios’ for all possible comparisons between biological replicates, genes are sorted according to the fold change ratios determined for each comparison into separate lists. The occurrence of a gene being depleted or enriched is evaluated by calculating its geometric rank product (RP). To estimate the probability of observing a specific RP value, a P-value is calculated. Importantly, RP values of several million random permutations of the original expression values (matrix) are estimated. These values are then used to calculate the likeliness of observing a RP value equal to or smaller than the one under consideration by random chance. Finally, a ‘Frequency Significance Score’ was estimated i.e. when all genes with RP values smaller/greater than the RP under consideration are corrected based on the permuted values.

Integrative bioinformatic and pathway analysis

For network and pathway enrichment analysis, we used the Reactome FI and Cytoscape plugin in (v2.8.1). The edge-betweenness algorithm was used to find network modules in protein interaction networks. Significantly enriched pathway gene sets were exported and analyzed using Enrichment Map (23) to determine relationships between pathways. The functional enrichment analyses for pathways were based on binomial test. False discovery rates were calculated based on 1,000 permutations on all genes in the network. To investigate functional network and gene ontology relationships, candidate genes were first categorized using the Panther classification system (24). For each molecular function, biological process or pathway term in PANTHER, the genes associated with that term were evaluated according to the likelihood that their numerical values were drawn randomly from the overall distribution of values. The Mann-Whitney U Test (Wilcoxon Rank-Sum Test) was used to determine the P-value relative to overall list of values that were input.

RESULTS

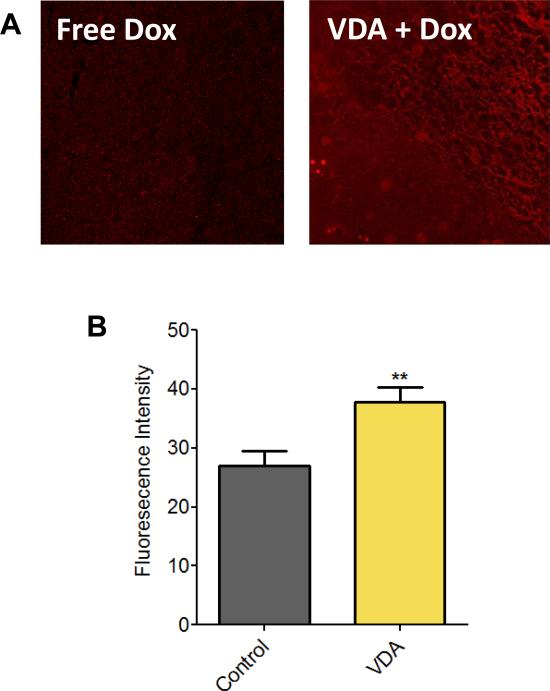

Vascular priming enhances intratumoral drug delivery

We assessed the impact of vascular priming on chemotherapeutic delivery using Doxorubicin. Doxorubicin was chosen for its autofluorescence properties which permits semi-quantitative assessment of drug concentration by fluorescence microscopy (25). Tumor-bearing mice were treated with either Doxorubicin alone (30 mg/kg, i.v.) or pretreated with DMXAA (25 mg/kg, i.p.) 1 hour prior to administration of Doxorubicin). Tumors were excised 1 hour post doxorubicin administration for microscopy. In support of our hypothesis, we observed increased fluorescence in tumors pre-treated with VDA compared to doxorubicin only controls (Fig. 1A). Quantitative estimates of fluorescence intensity also revealed a significant increase (p<0.01) in tumors pretreated with VDA (Fig. 1B).

Figure 1. Impact of vascular priming on drug delivery.

(A) Fluorescence microscopic images of subcutaneous FaDu tumors treated with Doxorubicin alone (Free Dox) or VDA (DMXAA 25 mg/kg, i.p.) in combination with Doxorubicin administration (VDA + Dox). (B) Bar graph shows quantification of fluorescent intensity levels from confocal microscopy images. A total of 14 fields were analyzed from 3 tumors per group (**p <0.01).

Dose and duration of VDA treatment influences treatment efficacy

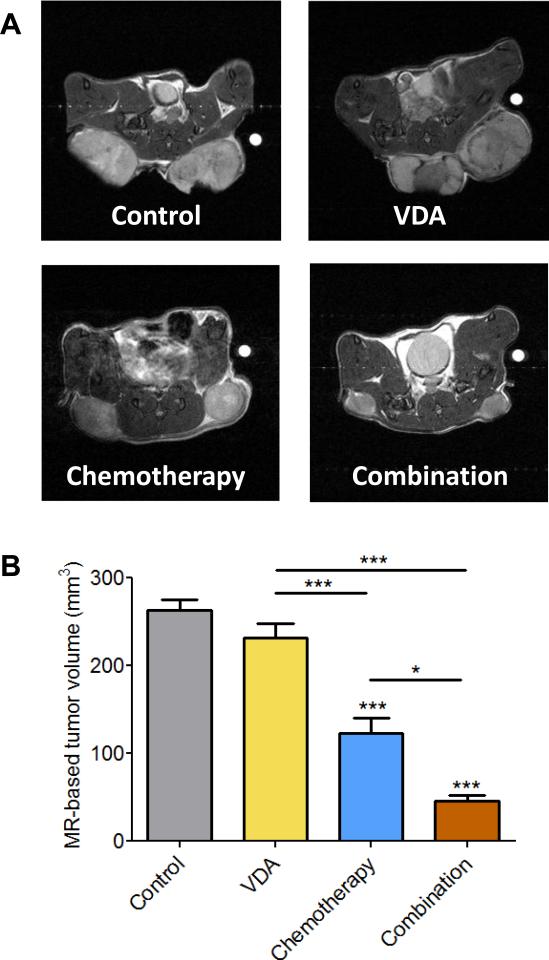

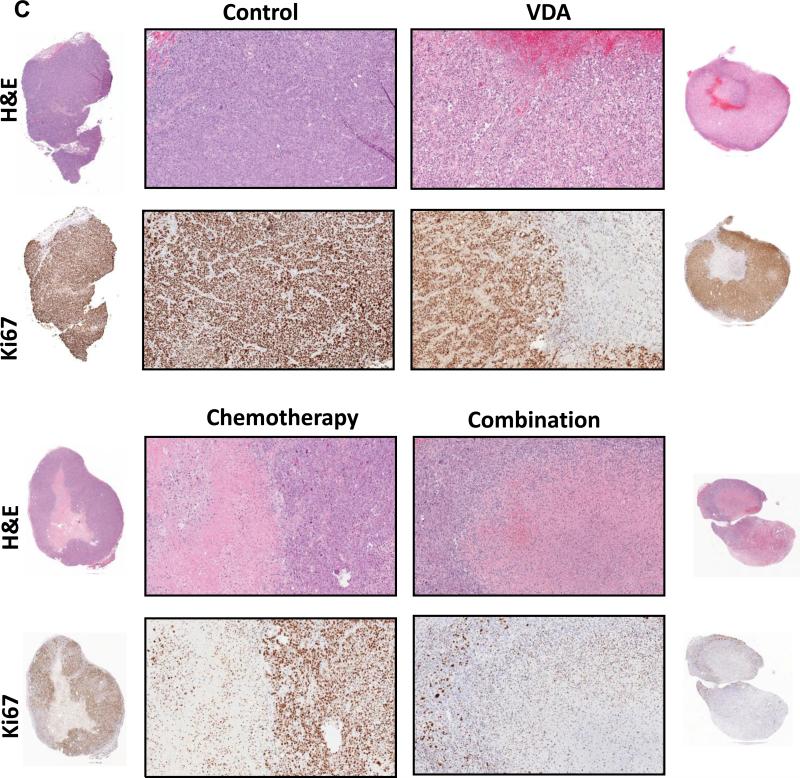

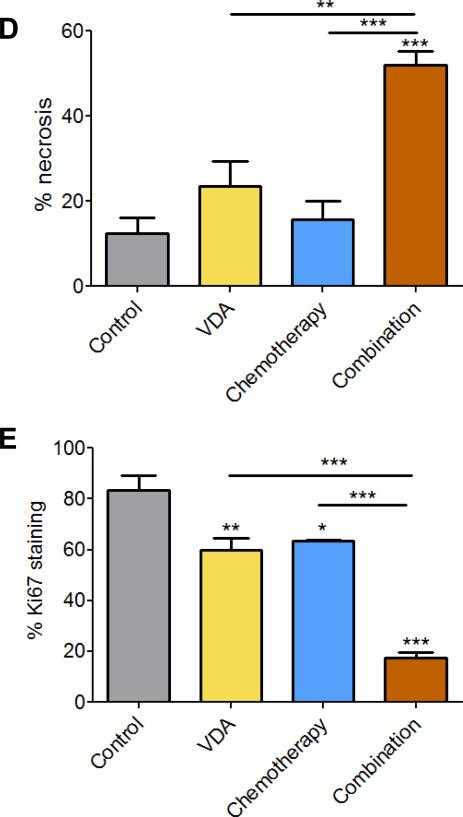

Next, we examined the impact of VDA dose and duration on treatment efficacy in the combination setting using the topoisomerase inhibitor, Irinotecan (CPT-11) in subcutaneous FaDu tumors and patient tumor-derived HNSCC xenografts. Administration of a single dose of CPT-11 (50 mg/kg, i.p.) 2 hours post priming with DMXAA (20 mg/kg, i.p.) did not result in any potentiation of antitumor activity in both tumor models (Supplementary Figs. 1 and 2). In the subcutaneous FaDu tumor model, administration of a single injection of DMXAA at a higher dose (25 mg/kg, i.p.) in combination with Irinotecan (50 mg/kg, i.p. 2 hours post VDA) resulted in the greatest increase in median survival compared to control animals (Supplementary Fig. S3). However, differences in median survival between combination and single agent treatments were not statistically significant. We then treated mice bearing subcutaneous FaDu tumors with DMXAA (25 mg/kg, i.p) in combination with Irinotecan (CPT; 50 mg/kg, i.p.) 2 hours post VDA once a week for 2 weeks. Magnetic resonance imaging and histopathologic assessment (Fig. 2) were carried out 48 hours post second treatment. MRI revealed a significant reduction in tumor volume (Fig 2A & B) following combination treatment compared to untreated controls (p<0.001), chemotherapy alone (p<0.05), and VDA alone (p<0.001). Corresponding immunohistochemical (Ki67) and histologic (H&E) sections of tumors are shown in Fig. 2C. When administered as single agents, chemotherapy and VDA resulted in minimal tumor necrosis. In comparison, combination treatment resulted in extensive necrosis (Fig. 2D) and reduction in Ki67 positivity (Fig. 2E) compared to controls and single agent treatments.

Figure 2. MRI and histopathologic assessment of HNSCC response to combination treatment.

(A) Panel of images represent axial T2-weighted images of mice showing subcutaneous FaDu tumors from control, VDA alone (DMXAA 25 mg/kg, i.p.), chemotherapy alone (CPT-11 50 mg/kg, i.p.) and combination groups (n=6 tumors per group). Images were acquired 48 hours post 2nd dose of treatment. (B) Bar graph shows tumor volumes calculated from multislice T2-weighted images of animals in all four groups (*p<0.05, ***p<0.001). (C) Panel of images represents photomicrographs of hematoxylin & eosin (H&E) and Ki67 stained sections of tumors from control and treatment groups (n = 3 per group). Whole tumor sections are also shown adjacent to the 10x magnified images. Quantitative estimates of necrosis (D) and Ki67 staining (E) showed increased necrosis and decreased in tumor proliferation following combination treatment compared to controls and either monotherapy (*p<0.05, **p<0.01***p<0.001).

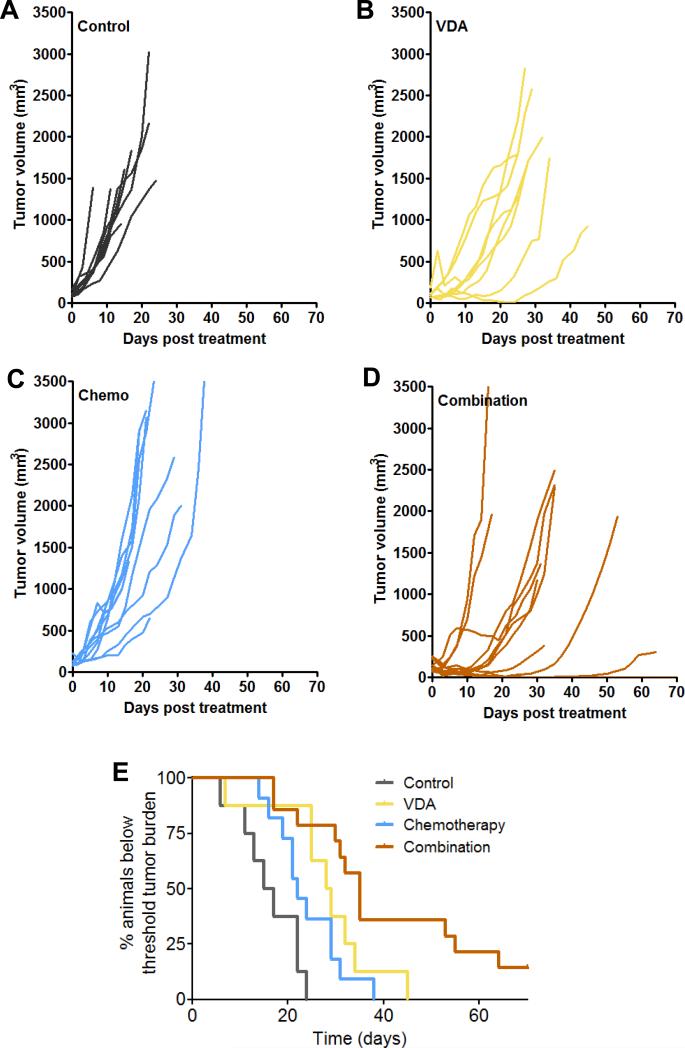

Enhancement of therapeutic efficacy by VDA is independent of the class of chemotherapy employed

We then determined if the increased chemotherapeutic efficacy by VDA treatment could be recapitulated using the anti-mitotic taxane, Docetaxel (Taxotere®), approved for clinical use in head and neck cancer (25). In these studies, mice bearing subcutaneous FaDu xenografts were treated with DMXAA (ASA; 25 mg/kg, i.p.) once a week for 3 weeks. Docetaxel (20 mg/kg, i.p.) was administered 2 hours post VDA for three weeks. Fig. 3 shows the change in tumor volumes of individual animals in control (A), VDA alone (B), chemotherapy alone (C) and combination groups (D). Tumor growth was monitored over a 60-day period to generate Kaplan-Meier survival curves (based on % of animals below threshold tumor burden requiring euthanasia). As shown in Fig. 3E, combination treatment conferred a significant survival benefit compared to control (p<0.0001), VDA alone (p<0.05) and chemotherapy alone (p<0.01) with ~20% animals in the combination group remaining alive at the end of the study.

Figure 3. In vivo efficacy of vascular disruption in combination with chemotherapy against subcutaneous FaDu tumor xenografts.

Change in tumor volumes of individual animals in control (A), VDA (B; DMXAA 25 mg/kg, i.p, once a week for 3 weeks), chemotherapy (C; Docetaxel 20 mg/kg, i.p. once a week for 3 weeks) and combination groups (n=8-14 mice per group) (D) over the 60-day monitoring period. Kaplan-Meier survival analysis of animals in all 4 groups is also shown (E). Combination treatment conferred a significant survival benefit compared to control (p<0.0001), VDA alone (p<0.05) and chemotherapy alone (p<0.01) (n=8-14 mice per group).

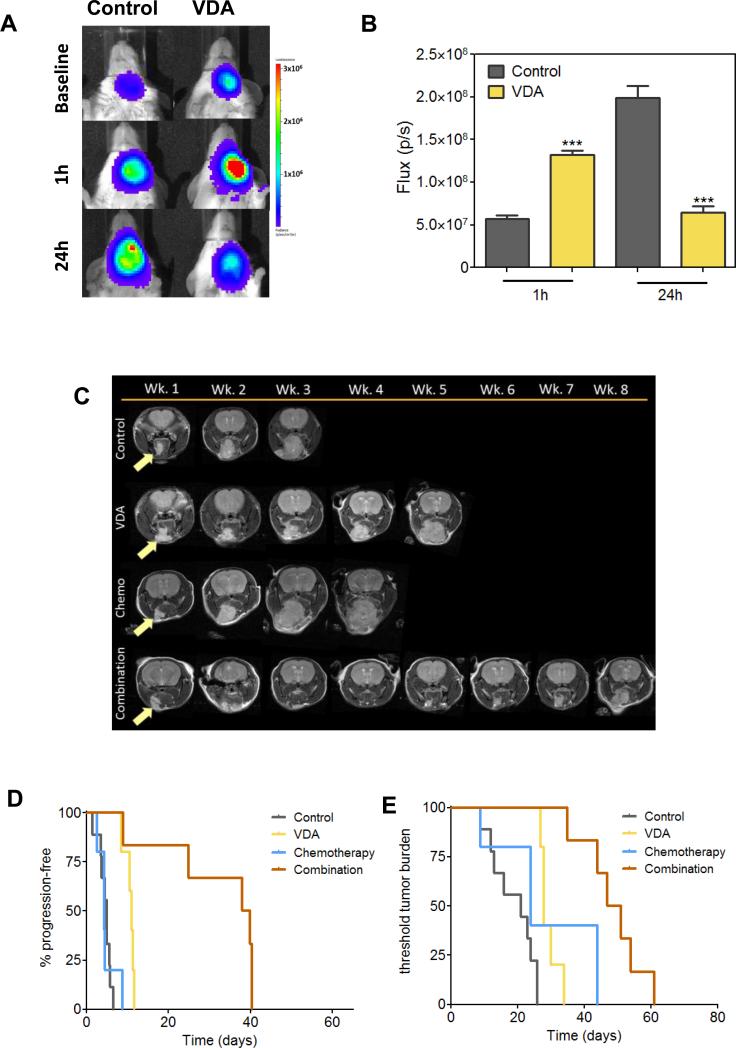

We also evaluated the activity of vascular disruption in combination with chemotherapy against orthotopic FaDu xenografts (Fig. 4). We used dynamic bioluminescence imaging (BLI; 26) to examine the early response of orthotopic FaDu tumors to VDA therapy (Fig. 4A & B). Consistent with our observations in subcutaneous tumors, dynamic BLI (Supplementary Figure S4) revealed an early increase in bioluminescent flux 1 hour post VDA treatment suggestive of enhanced delivery of the luciferin substrate to the tumor. At 24 hours post treatment, BLI revealed a reduction in flux indicative of VDA-induced vascular collapse and tumor cell kill (27). Contrast-enhanced MRI revealed a reduction in relative blood volume 24 hours post VDA treatment (Supplementary Figure S4). Long-term treatment efficacy was assessed by monitoring change in tumor volume of orthotopic FaDu tumors using MRI following treatment with DMXAA (25mg/kg, i.p.) alone or in combination with Docetaxel (10mg/kg, i.p.) administered 2 hours post VDA for three weeks. Figure 4C shows axial T2-weighted images of mice bearing orthotopic FaDu tumors in control and treatment groups. A significant increase in progression-free survival (Figure 4D) was seen following combination treatment compared to single agent treatment and controls (p<0.01 or greater). Kaplan-Meier analysis of overall survival also showed a significant increase with combination treatment (49 days; Fig. 4E) compared to controls (21 days; p<0.001), VDA alone (28 days; p<0.001), and chemotherapy alone (24 days; p<0.05). Individual tumor volumes calculated from T2-weighted MRI acquired weekly are shown in Supplementary Figure S5.

Figure 4. Antitumor activity of combination treatment against orthotopic FaDu tumors.

(A) Bioluminescent images of control and VDA-treated mice bearing orthotopic FaDu tumors at baseline, 1hr and 24hrs post VDA treatment (DMXAA 25mg/kg × 1 dose) (n=3 mice per group). (B) Reported flux values over time for control and VDA treated mice. A significant increase in flux was observed at 1 hour (p<0.001) followed by a reduction at 24 hours hours post VDA treatment (p<0.001). (C) T2-weighted images of mice bearing orthotopic FaDu tumors (arrows) acquired once a week during the eight week monitoring period. Significant tumor growth inhibition following combination treatment compared to single agent treatment and controls. Kaplan-Meier plots showing progression free survival (D) and overall survival (E) of animals from all four groups. Combination treatment resulted in a significant increase in OS of animals compared to VDA alone (p<0.001) and chemotherapy alone (p<0.05) (n=5-9 mice per group).

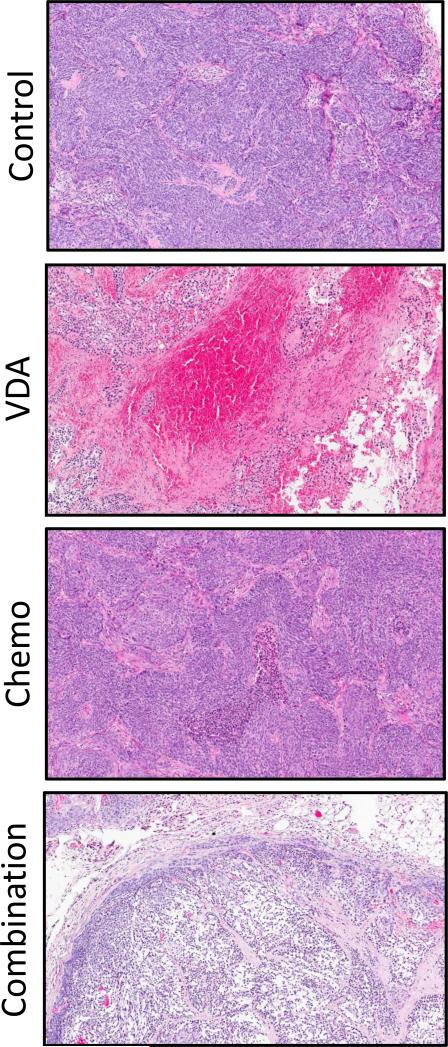

Vascular disruption in combination with chemotherapy exhibits improved antitumor activity against patient tumor-derived HNSCC xenografts

Finally, we examined the efficacy of vascular disruption in combination with chemotherapy against patient tumor-derived xenografts. Mice bearing ectopic patient tumor xenografts were treated with the tumor DMXAA (25 mg/kg, i.p.) in combination with Docetaxel (10 mg/kg, i.p.). Figure 5 shows H&E stained sections of patient tumor-derived HNSCC xenografts excised from control and treated animals. Densely packed viable tumor cells with a few necrotic areas were visible in control sections. VDA-treated tumors showed areas of hemorrhaging and central necrosis with surviving viable rim. Docetaxel-treated tumors showed minimal necrosis while tumor sections of animals treated with the combination showed evidence of extensive necrosis. To define the transcriptional effects of DMXAA in patient tumor-derived HNSCC xenografts, we performed gene expression profiling and bioinformatics analysis. Using a modified Rank Product method for identifying differentially expressed genes and a FDR cut-off value of 0.05 as being significant, a core set of genes was identified that were positively or negatively regulated by DMXAA. Next, we used network community analysis to automatically identify modules that contain genes and their products that are involved in common processes. The results (shown in Supplementary Fig. 6) were consistent with DMXAA exerting its antivascular activity through cytokine induction and chemokine modulation, including induction of tumor necrosis factor (TNF-alpha) and interleukin (IL-6) canonical pathways (28-30). Analysis of the functional interactions between gene classes in the transcriptomes under study with Gene Ontology identified several annotated biomarkers including IL-8, MMP-10, STAT1, STC1, FSTL3, CXCL1 and CTSB.

Figure 5. Response of patient tumor-derived HNSCC xenografts to combined VDA-chemotherapy.

Hematoxylin and eosin stained sections of patient tumor-derived HNSCC xenografts 24 hours post treatment with VDA alone (25 mg/kg, i.p.) or in combination with chemotherapy (Docetaxel, 10 mg/kg, i.p.). Images shown are at 10x magnification. Extensive necrosis was seen following combination treatment compared to VDA alone or chemotherapy alone.

DISCUSSION

The abnormal tumor vascular network poses an important physiological barrier that adversely affects intratumoral drug delivery and distribution (3). Phenotypic differences between normal tissue and tumor vasculature have been well documented in experimental model systems (31). In addition to these structural differences, homeostatic mechanisms that efficiently regulate vascular function in normal tissues are absent in tumor vasculature. It is believed that these structural and functional deficiencies render tumor vessels more susceptible to fluctuations in perfusion/permeability following VDA treatment which in turn result in irreversible and catastrophic vascular damage (12, 32). Since VDAs result in an early increase in tumor vascular permeability in vivo (12-16), we postulated that it may be optimal to administer chemotherapy shortly after VDA treatment (within 1-4 hours) when the blood flow to the tumor has not been completely compromised. It was our hypothesis that the early enhancement of permeability following VDA treatment would potentially increase intratumoral drug delivery and enhance therapeutic efficacy. To test this hypothesis, we evaluated the combination of VDA and chemotherapy using a two hour interval, with chemotherapy administered 2 hours after VDA treatment. In support of our hypothesis, we observed increased drug delivery following pretreatment of tumors with VDA (2 hours prior to chemotherapy administration). In support of this approach, Marysael et al., have previously reported increased accumulation of the necrosis avid agent, Hypericin, when administered 24 hours after treatment with DMXAA (33). In our study, enhancement of therapeutic efficacy was dependent on the VDA dose employed. This is not entirely surprising given the steep dose response of curve of DMXAA in vivo (14, 34). Given that VDAs exhibit moderate antitumor activity as single agents, studies have investigated and demonstrated favorable interactions between VDA and chemotherapeutics in experimental model systems (35, 36). However, only a few preclinical studies have explored the impact of sequence and schedule on treatment outcome (34, 37, 38). Siemann et al., have previously investigated the effect of administering DMXAA before or after cisplatin in a sarcoma model (37). In the study, tumor response assessment was made using the clonogenic survival assay to calculate the tumor surviving fraction 24 hours after a single treatment. The results showed that pretreatment with the VDA DMXAA (1-2 hours) prior to cisplatin administration did not result in any enhancement of therapeutic efficacy. Siim et al., investigated the effect of timing of DMXAA treatment on the antitumor activity of paclitaxel in a mammary tumor model (34). The study revealed comparable tumor response rates when paclitaxel was administered up to 4 hours before or 1 hour after DMXAA treatment. In the same study, it was shown that administration of paclitaxel 4 hours after VDA treatment resulted in substantial loss of antitumor activity, presumably due to impaired drug delivery (36). Consistent with these observations (37, 38), we did not observe any enhancement of antitumor activity after a single treatment with the VDA in combination with chemotherapy. More importantly, we observed that the enhancement was dependent on duration of VDA treatment with maximal potentiation observed with three weeks of treatment. This suggests that sustained disruption of vasculature in combination with tumor cell kill is necessary for durable antitumor responses. Computational modeling of tumor response to VDAs has also suggested that administration of VDAs once every three weeks maybe sub-optimal and insufficient for steady tumor growth inhibition (39). Similar observations between treatment length and outcome have also been observed with antiangiogenic agents (40). Bagri et al. (40) have shown that longer exposure to anti-VEGF antibodies resulted in maximal therapeutic benefit and prevented regrowth of tumors following cytoablative therapy.

In addition to improving drug delivery, pretreating of tumors with the VDA may also serve to enhance chemotherapeutic efficacy through other mechanisms. A consistent observation seen in experimental tumor models is the presence of viable tumor cells and blood vessels in the periphery that survive VDA therapy and contribute to tumor regrowth and treatment resistance (41). Studies have demonstrated that VDAs trigger rapid mobilization of bone-marrow derived circulating endothelial progenitor cells (CEPs) and vascular modulatory cells such as pro-angiogenic monocytes and tumor-associated macrophages to the tumor margins, which in turn, facilitate revascularization and tumor cell repopulation (41, 42). This adaptive response is presumably a consequence of VDA-induced hypoxia which activates hypoxia inducible factor 1α (HIF-1α) and increased expression of pro-angiogenic factors and survival pathways (43). It has therefore been suggested that administration of chemotherapy or an antiangiogenic agent after VDA therapy will allow targeting these CEPs and prevent tumor regrowth (41, 44). In this regard, blockade of CXCR4 signaling has also been shown to suppress VDA-induced CEP mobilization, inhibit tumor infiltration of proangiogenic Tie2-expressing macrophages and improve therapeutic efficacy of VDAs in preclinical models (42).

Another benefit of combining VDA with chemotherapy is the inherent targeting of multiple compartments within the tumor, as the VDA targets endothelial cells and induces necrosis of the tumor core, while conventional cytotoxics act on the proliferating rim of viable cells at the well-perfused tumor periphery (12, 34, 35). We investigated two different classes of chemotherapeutic agents-the topoisomerase I inhibitor, Irinotecan, and the anti-mitotic taxane, Docetaxel. Irinotecan, though not part of the standard of care in HNSCC, has been shown to be moderately efficacious against recurrent/metastatic disease (45). The addition of docetaxel to standard induction chemotherapy (5-FU and Cisplatin) has been shown to increase survival in patients with locoregionally advanced HNSCC in Phase III trials (46). While we observed improved efficacy with both agents, efficacy in the combination setting is likely to be influenced by the mechanism of action of the VDA and the chemotherapeutic agent employed. DMXAA is a small molecule VDA that exerts its antivascular effects both directly on the vascular endothelial cells and indirectly involving the modulation of the host immune system (7, 28-30). Our gene expression analysis results are consistent with these known effects of DMXAA on cytokine induction and chemokine modulation including induction of tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) and IFN-inducible protein 10 (22-24). However, other VDAs currently undergoing preclinical and clinical development such as combretastatin and its analogues exert their antivascular activity by destabilization of microtubules (47). It has therefore been suggested that chemotherapeutics (e.g. taxanes) that stabilize microtubules may interfere with the anti-vascular activity of VDAs (48). Pretreatment of tumors with the VDA can therefore avoid the potential antagonistic activity of chemotherapeutics acting on tubulin. Supportive evidence for this hypothesis has been demonstrated in a previous study by Martinelli et al, which showed that pretreatment of tumors with the VDA ZD6126 before paclitaxel treatment resulted in improved therapeutic activity (38). Collectively, these observations highlight the influence of scheduling on the complex interaction between VDA and chemotherapy.

We recognize some of the limitations of the study. The two hour interval used in our study was chosen based on the known temporal effects of VDA treatment on vascular function and our previous studies carried out with DMXAA in the combination setting (13-16). While we did not compare treatment outcomes when VDA and chemotherapy were administered at varying intervals, contrast-enhanced MRI of tumors did not reveal any difference in tumor perfusion at 2 hours post VDA treatment compared to 20 minutes (the interval utilized in clinical studies) post treatment. Interestingly, while the combination of VDA and Irinotecan was well tolerated with the 2 hour interval, we observed unacceptable toxicity (~50% deaths in tumor-bearing animals) with the concurrent administration of VDA and Irinotecan. Nevertheless, a direct comparison of outcomes with varied schedules and sequences would further strengthen the argument for pretreatment of tumors with VDA prior to chemotherapy. Secondly, in our study, Doxorubicin was chosen for its autofluorescence properties and Irinotecan was utilized based on our intent to investigate the influence of the class of chemotherapeutic agent (e.g. Topoisomerase inhibitors vs. Taxanes) on the antitumor activity in the combination setting with the VDA. However, Irinotecan and Doxorubicin are not a part of the standard of care for HNSCC. It would therefore be useful to examine the therapeutic impact of VDAs in combination with other agents such as Cisplatin and 5-Fluorouracil. And finally, investigation using a non responsive cell line would have been helpful in examining the potential mechanisms involved in resistance to VDA therapy. Studies to address some of these limitations are currently underway in our laboratory.

Nevertheless, we believe the findings of our study have important clinical implications. The recently failed Phase III study of DMXAA has dampened the enthusiasm of tumor-VDAs in the clinical arena (11). Although further clinical evaluation of DMXAA is unlikely, other VDAs (e.g. fosbretabulin, crolibulin, and Oxi4053) are undergoing preclinical and clinical development. We are currently investigating the antivascular and antitumor activity of the tubulin-binding agent, Crolibulin (EPC2407) that is currently undergoing Phase I/II evaluation in anaplastic thyroid cancer (Clinicaltrials.gov ID: NCT01240590). Early observations with EPC2407 also support our approach of vascular priming of tumors prior to administration of chemotherapy (Seshadri, unpublished observation). Taken together, our studies suggest that the dose, duration and schedule of VDA treatment are likely to influence efficacy in the combination setting. Future clinical trials of VDAs should therefore evaluate the impact of sequence/schedule and duration of VDA treatment on efficacy. In this regard, the use of non-invasive imaging methods in conjunction with pharmacokinetic assessment (49) may prove valuable in the design of clinical trials of VDAs. Secondly, the poor survival associated with recurrent or metastatic HNSCC underscores the critical therapeutic needs of this patient population. While there has been active interest in targeting angiogenesis in HNSCC, attention has been focused primarily on antiangiogenic agents. Only a few studies have examined the potential of VDA therapy against head and neck cancers. The results of our studies demonstrate the utility of tumor-VDAs in the treatment paradigm for head and neck cancer (47, 50). Further investigation into the activity of VDAs, particularly in combination with chemotherapy and novel targeted therapies against HNSCC is warranted.

Supplementary Material

Figure S1. Tumor growth curves and doubling times of control, VDA (DMXAA 20 mg/kg, i.p), chemotherapy (CPT-11, 50 mg/kg, i.p.) and combination treated animals bearing subcutaneous FaDu tumors (n=6-9 mice per group). Animals received a single injection of either agent alone or in combination. No significant differences in tumor growth or doubling times were observed between the experimental groups.

Figure S2. Tumor growth curves and doubling times of control, VDA (DMXAA 20 mg/kg, i.p), chemotherapy (CPT-11, 50 mg/kg, i.p.) and combination treated animals bearing subcutaneous patient tumor-derived HNSCC xenografts (n=5-7 mice per group). Animals received a single injection of either agent alone or in combination. No significant differences in tumor growth or doubling times were observed between the experimental groups.

Figure S3. Tumor growth curves and doubling times of control, VDA (DMXAA 25 mg/kg, i.p), chemotherapy (CPT-11, 50 mg/kg, i.p.) and combination treated animals bearing subcutaneous FaDu xenografts (n=4-6 mice per group). Animals received a single injection of either agent alone or in combination. Animals that received combination treatment showed a significant increase in median survival compared to controls (p<0.01).

Figure S4. Dynamic BLI of HNSCC response to VDA treatment. (A) Flux values over time (minutes post luciferin injection) of orthotopic FaDu tumors at 1 hour and 24 hours post VDA treatment. (B) Contrast-enhanced MRI of orthotopic HNSCC xenografts. Normalized images of contrast enhancement following administration of albumin-GdDTPA in control and VDA-treated orthotopic FaDu tumors 24 hours post treatment (25 mg/kg, i.p.). (C) Relative blood volume estimates showed a significant (p=0.01) decrease in VDA-treated tumors compared to untreated controls (n= 3 per group).

Figure S5. Tumor growth curves for control, VDA (DMXAA 25 mg/kg, i.p once a week for 3 weeks), chemotherapy (Taxotere, 10 mg/kg, i.p. once a week for 3 weeks) and combination treated animals bearing orthotopic FaDu xenografts (n=5-9 mice per group).

Figure S6. DMXAA-specific extended functional interaction network from patient tumor-derived HNSCC xenografts. Gene Nodes in different clusters are displayed in different colors. Functional interactions (FIs) extracted from pathways are shown in solid lines, while those based on naïve-bayes classifier (NBC) are shown in dashed lines (for example, CXCL9-CXCL10). FIs involved in activation, expression regulation or catalysis are shown with an arrowhead on the end of the line, while FIs involved in inhibition are shown with a ‘T’ bar.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the staff of the shared resources at RPCI for their technical assistance in performing these studies: Laboratory Animal Resource, Small Animal Bio-Imaging Resource, Genomics and Microarray, Tissue culture and media facility, and Pathology Resource Network. This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute R21-CA133688 (M.S.), the Alliance Foundation (M.S.) and utilized core resources supported the NCI Cancer Center Support Grant CA016156 (Trump, DL).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

M.F, J.K and J.L contributed equally to this work

Conflict of Interest statement: The authors declare that they have no competing financial interests in relation to the work described in the study.

Some of the results of this study were presented at the Annual meeting of the American Head and Neck Society held in July 2012.

REFERENCES

- 1.Patel SG, Shah JP. TNM staging of cancers of the head and neck: striving for uniformity among diversity. CA Cancer J Clin. 2005;55:242–8. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.55.4.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blanchard P, Baujat B, Holostenco V, Bourredjem A, Baey C, Bourhis J, et al. Meta-analysis of chemotherapy in head and neck cancer (MACH-NC): a comprehensive analysis by tumour site. Radiother Oncol. 2011;100:33–40. doi: 10.1016/j.radonc.2011.05.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Folkman J. Tumor angiogenesis: therapeutic implications. N Engl J Med. 1971 Nov 18;285:1182–6. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197111182852108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zätterström UK, Brun E, Willén R, Kjellén E, Wennerberg J. Tumor angiogenesis and prognosis in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Head Neck. 1995;17:312–8. doi: 10.1002/hed.2880170407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Galmarini FC, Galmarini CM, Sarchi MI, Abulafia J, Galmirini D. Heterogeneous distribution of tumor blood supply affects the response to chemotherapy in patients with head and neck cancer. Microcirculation. 2000;7:405–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kaanders JH, Wijffels KI, Marres HA, Ljungkvist AS, Pop LA, van den Hoogen FJ, et al. Pimonidazole binding and tumor vascularity predict for treatment outcome in head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 2002;62:7066–74. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Baguley BC, Ching LM. DMXAA: an antivascular agent with multiple host responses. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2002;54:1503–11. doi: 10.1016/s0360-3016(02)03920-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seshadri M, Mazurchuk R, Spernyak JA, Bhattacharya A, Rustum YM, Bellnier DA. Activity of the vascular-disrupting agent 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid against human head and neck carcinoma xenografts. Neoplasia. 2006;8:534–42. doi: 10.1593/neo.06295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seshadri M, Sacadura NT, Coulthard T. Monitoring antivascular therapy in head and neck cancer xenografts using contrast-enhanced MR and US imaging. Angiogenesis. 2011;14:491–501. doi: 10.1007/s10456-011-9233-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Pili R, Rosenthal MA, Mainwaring PN, Van Hazel G, Srinivas S, Dreicer R, et al. Phase II study on the addition of ASA404 (vadimezan; 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid) to docetaxel in CRMPC. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:2906–14. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lara PN, Jr, Douillard JY, Nakagawa K, von Pawel J, McKeage MJ, Albert I, Losonczy G, et al. Randomized phase III placebo-controlled trial of carboplatin and paclitaxel with or without the vascular disrupting agent vadimezan (ASA404) in advanced non-small-cell lung cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2965–71. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2011.35.0660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tozer GM, Kanthou C, Baguley BC. Disrupting tumour blood vessels. Nat Rev Cancer. 2005;5:423–35. doi: 10.1038/nrc1628. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Baguley BC, Siemann DW. Temporal aspects of the action of ASA404 (Vadimezan; DMXAA). Expert Opinion Investig Drugs. 2010;19:1413–25. doi: 10.1517/13543784.2010.529128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Seshadri M, Spernyak JA, Mazurchuk R, Camacho SH, Oseroff AR, Cheney RT, et al. Tumor vascular response to photodynamic therapy and the antivascular agent 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid: implications for combination therapy. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:4241–50. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhao L, Ching LM, Kestell P, Kelland LR, Baguley BC. Mechanisms of tumor vascular shutdown induced by 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid (DMXAA): Increased tumor vascular permeability. Int J Cancer. 2005;116:322–6. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Seshadri M, Spernyak JA, Maiery PG, Cheney RT, Mazurchuk R, Bellnier DA. Visualizing the acute effects of vascular-targeted therapy in vivo using intravital microscopy and magnetic resonance imaging: correlation with endothelial apoptosis, cytokine induction, and treatment outcome. Neoplasia. 2007;9:128–35. doi: 10.1593/neo.06748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seshadri M, Merzianu M, Tang H, Rigual NR, Sullivan M, Loree TR, et al. Establishment and characterization of patient tumor-derived head and neck squamous cell carcinoma xenografts. Cancer Biol Ther. 2009;8:2275–83. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.23.10137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bhattacharya A, Seshadri M, Oven SD, Tóth K, Vaughan MM, Rustum YM. Tumor vascular maturation and improved drug delivery induced by methylselenocysteine leads to therapeutic synergy with anticancer drugs. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3926–32. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orth RC, Bankson J, Price R, Jackson EF. Comparison of single- and dual-tracer pharmacokinetic modeling of dynamic contrast-enhanced MRI data using low, medium, and high molecular weight contrast agents. Magn Reson Med. 2007;58:705–16. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh M, Lima A, Molina R, Hamilton P, Clermont AC, Devasthali V, et al. Assessing therapeutic responses in Kras mutant cancers using genetically engineered mouse models. Nat Biotechnol. 2010;28:585–93. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gentleman RC, Carey VJ, Bates DM, Bolstad B, Dettling M, Dudoit S, et al. Bioconductor: open software development for computational biology and bioinformatics. Genome Biol. 2004;5:R80. doi: 10.1186/gb-2004-5-10-r80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Du P, Kibbe WA. Lin SM: lumi: a pipeline for processing Illumina microarray. Bioinformatics. 2008;24:1547–48. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Merico D, Isserlin R, Stueker O, Emili A, Bader GD. Enrichment map: a network-based method for gene-set enrichment visualization and interpretation. PLoS One. 2010;5:e13984. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0013984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mi H, Guo N, Kejariwal A, Thomas PD. PANTHER version 6: protein sequence and function evolution data with expanded representation of biological pathways. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007;35:D247–D252. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Primeau AJ, Rendon A, Hedley D, Lilge L, Tannock IF. The distribution of the anticancer drug doxorubicin in relation to blood vessels in solid tumors. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:8782–8. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-1664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Vermorken JB, Remenar E, van Herpen C, Gorlia T, Mesia R, Degardin M, et al. Cisplatin, fluorouracil, and docetaxel in unresectable head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1695–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun A, Hou L, Prugpichailers T, Dunkel J, Kalani MA, Chen X, Kalani MY, Tse V. Firefly luciferase-based dynamic bioluminescence imaging: a noninvasive technique to assess tumor angiogenesis. Neurosurgery. 2010;66:751–7. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000367452.37534.B1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mason RP, Zhao D, Liu L, Trawick ML, Pinney KG. A perspective on vascular disrupting agents that interact with tubulin: preclinical tumor imaging and biological assessment. Integr Biol (Camb) 2011;3:375–87. doi: 10.1039/c0ib00135j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang LC, Thomsen L, Sutherland R, Reddy CB, Tijono SM, Chen CJ, et al. Neutrophil influx and chemokine production during the early phases of the antitumor response to the vascular disrupting agent DMXAA (ASA404). Neoplasia. 2009;11:793–803. doi: 10.1593/neo.09506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sun J, Wang LC, Fridlender ZG, Kapoor V, Cheng G, Ching LM, et al. Activation of mitogen-activated protein kinases by 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid (DMXAA) plays an important role in macrophage stimulation. Biochem Pharmacol. 2011;82:1175–85. doi: 10.1016/j.bcp.2011.07.086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henare K, Wang L, Wang LC, Thomsen L, Tijono S, Chen CJ, et al. Dissection of stromal and cancer cell-derived signals in melanoma xenografts before and after treatment with DMXAA. Br J Cancer. 2012;106:1134–47. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2012.63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ruoslahti E. Specialization of_tumour_vasculature. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:83–90. doi: 10.1038/nrc724. Review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Siemann DW. The unique characteristics of tumor vasculature and preclinical evidence for its selective disruption by Tumor-Vascular Disrupting Agents. Cancer Treat Rev. 2011;37:63–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ctrv.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Marysael T, Ni Y, Lerut E, de Witte P. Influence of the vascular damaging agents DMXAA and ZD6126 on hypericin distribution and accumulation in RIF-1 tumors. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2011;137:1619–27. doi: 10.1007/s00432-011-1032-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Siim BG, Lee AE, Shalal-Zwain S, Pruijn FB, McKeage MJ, Wilson WR. Marked potentiation of the antitumour activity of chemotherapeutic drugs by the antivascular agent 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid (DMXAA) Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2003;51:43–52. doi: 10.1007/s00280-002-0529-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.McKeage M, Kelland L. 5,6-Dimethylxanthenone-4-Acetic Acid (DMXAA): Clinical potential in combination with taxane-Based chemotherapy. American Journal of Cancer. 2006;5:155–62. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lash CJ, Li AE, Rutland M, Baguley BC, Zwi LJ, Wilson WR. Enhancement of the anti-tumour effects of the antivascular agent 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid (DMXAA) by combination with 5-hydroxytryptamine and bioreductive drugs. Br J Cancer. 78:439. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1998.512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siemann DW, Mercer E, Lepler S, Rojiani AM. Vascular targeting agents enhance chemotherapeutic agent activities in solid tumor therapy. Int J Cancer. 2002;99:1–6. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martinelli M, Bonezzi K, Riccardi E, Kuhn E, Frapolli R, Zucchetti M, et al. Sequence dependent antitumour efficacy of the vascular disrupting agent ZD6126 in combination with paclitaxel. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:888–94. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gevertz JL. Computational modeling of tumor response to vascular-targeting therapies--part I: validation. Comput Math Methods Med. 2011:830515. doi: 10.1155/2011/830515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Bagri A, Berry L, Gunter B, Singh M, Kasman I, Damico LA, et al. Effects of anti-VEGF treatment duration on tumor growth, tumor regrowth, and treatment efficacy. Clin Cancer Res. 2010;16:3887–900. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-09-3100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shaked Y, Ciarrocchi A, Franco M, Lee CR, Man S, Cheung AM, et al. Therapy-induced acute recruitment of circulating endothelial progenitor cells to tumors. Science. 2006;313:1785–7. doi: 10.1126/science.1127592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Welford AF, Biziato D, Coffelt SB, Nucera S, Fisher M, Pucci F, et al. TIE2-expressing macrophages limit the therapeutic efficacy of the vascular-disrupting agent combretastatin A4 phosphate in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121:1969–73. doi: 10.1172/JCI44562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Dachs GU, Steele AJ, Coralli C, Kanthou C, Brooks AC, Gunningham SP, Currie MJ, Watson AI, Robinson BA, Tozer GM. Anti-vascular agent Combretastatin A-4-P modulates hypoxia inducible factor-1 and gene expression. BMC Cancer. 2006;7:280. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-6-280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Taylor M, Billiot F, Marty V, Rouffiac V, Cohen P, Tournay E, et al. Reversing resistance to vascular-disrupting agents by blocking late mobilization of circulating endothelial progenitor cells. Cancer Discov. 2012;2:434–49. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Murphy BA, Cmelak A, Burkey B, Netterville J, Shyr Y, Douglas S, et al. Topoisomerase I inhibitors in the treatment of head and neck cancer. Oncology (Williston Park) 2001;15:47–52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vermorken JB, Remenar E, van Herpen C, Gorlia T, Mesia R, Degardin M, et al. Cisplatin, fluorouracil, and docetaxel in unresectable head and neck cancer. N Engl J Med. 2007;357:1695–704. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa071028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yeung SC, She M, Yang H, Pan J, Sun L, Chaplin D. Combination chemotherapy including combretastatin A4 phosphate and paclitaxel is effective against anaplastic thyroid cancer in a nude mouse xenograft model. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:2902–9. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taraboletti G, Micheletti G, Dossi R, Borsotti P, Martinelli M, Fiordaliso F, et al. Potential antagonism of tubulin-binding anticancer agents in combination therapies. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:2720–6. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Jameson MB, Head M. Pharmacokinetic evaluation of vadimezan (ASA404, 5,6-dimethylxanthenone-4-acetic acid, DMXAA). Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol. 2011;7:1315–26. doi: 10.1517/17425255.2011.614389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Clémenson C, Jouannot E, Merino-Trigo A, Rubin-Carrez C, Deutsch E. The vascular disrupting agent ombrabulin (AVE8062) enhances the efficacy of standard therapies in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma xenograft models. Invest New Drugs. Apr. 2013;31(2):273–84. doi: 10.1007/s10637-012-9852-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Figure S1. Tumor growth curves and doubling times of control, VDA (DMXAA 20 mg/kg, i.p), chemotherapy (CPT-11, 50 mg/kg, i.p.) and combination treated animals bearing subcutaneous FaDu tumors (n=6-9 mice per group). Animals received a single injection of either agent alone or in combination. No significant differences in tumor growth or doubling times were observed between the experimental groups.

Figure S2. Tumor growth curves and doubling times of control, VDA (DMXAA 20 mg/kg, i.p), chemotherapy (CPT-11, 50 mg/kg, i.p.) and combination treated animals bearing subcutaneous patient tumor-derived HNSCC xenografts (n=5-7 mice per group). Animals received a single injection of either agent alone or in combination. No significant differences in tumor growth or doubling times were observed between the experimental groups.

Figure S3. Tumor growth curves and doubling times of control, VDA (DMXAA 25 mg/kg, i.p), chemotherapy (CPT-11, 50 mg/kg, i.p.) and combination treated animals bearing subcutaneous FaDu xenografts (n=4-6 mice per group). Animals received a single injection of either agent alone or in combination. Animals that received combination treatment showed a significant increase in median survival compared to controls (p<0.01).

Figure S4. Dynamic BLI of HNSCC response to VDA treatment. (A) Flux values over time (minutes post luciferin injection) of orthotopic FaDu tumors at 1 hour and 24 hours post VDA treatment. (B) Contrast-enhanced MRI of orthotopic HNSCC xenografts. Normalized images of contrast enhancement following administration of albumin-GdDTPA in control and VDA-treated orthotopic FaDu tumors 24 hours post treatment (25 mg/kg, i.p.). (C) Relative blood volume estimates showed a significant (p=0.01) decrease in VDA-treated tumors compared to untreated controls (n= 3 per group).

Figure S5. Tumor growth curves for control, VDA (DMXAA 25 mg/kg, i.p once a week for 3 weeks), chemotherapy (Taxotere, 10 mg/kg, i.p. once a week for 3 weeks) and combination treated animals bearing orthotopic FaDu xenografts (n=5-9 mice per group).

Figure S6. DMXAA-specific extended functional interaction network from patient tumor-derived HNSCC xenografts. Gene Nodes in different clusters are displayed in different colors. Functional interactions (FIs) extracted from pathways are shown in solid lines, while those based on naïve-bayes classifier (NBC) are shown in dashed lines (for example, CXCL9-CXCL10). FIs involved in activation, expression regulation or catalysis are shown with an arrowhead on the end of the line, while FIs involved in inhibition are shown with a ‘T’ bar.