Abstract

Context

Rural counties in the U.S. have higher rates of obesity, sedentary lifestyle, and associated chronic diseases than non-rural areas, yet the management of obesity in rural communities has received little attention from researchers.

Objective

To compare 2 extended-care programs for weight management with an education control group.

Design, Setting, and Participants

234 obese women from rural communities who completed an initial 6-month weight-loss program were randomized to extended-care, delivered via telephone counseling or face-to-face sessions, or to an education control group. Cooperative Extension Service offices in six medically underserved rural counties served as venues for the trial. The study was conducted from June 2003 to May 2007.

Interventions

The extended-care programs entailed problem-solving counseling delivered in 26 biweekly sessions. Control group participants received 26 biweekly newsletters containing weight-control advice.

Main Outcome Measure

Change in weight from randomization.

Results

Mean weight at study entry was 96.4 kg. Mean weight loss during the initial 6-month intervention was 10.0 kg. One year after randomization, participants in the telephone and face-to-face conditions regained less weight (means ± SE = 1.3 ± 0.7 and 1.2 ± 0.6 kg, respectively) than those in the education control group (3.7 ± 0.6 kg; Ps = 0.02 and 0.03). The beneficial effects of extended-care counseling were mediated by greater adherence to behavioral weight-management strategies, and cost analyses indicated that telephone counseling was less expensive than face-to-face intervention.

Conclusion

Extended care delivered either by telephone or face-to-face sessions improved the one-year maintenance of lost weight compared to education alone. Telephone counseling constitutes an effective and cost-efficient option for long-term weight management. Delivering lifestyle interventions via the existing infrastructure of the Cooperative Extension Service represents a viable means of research translation into rural communities with limited access to preventive health services.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov number, NCT00201006.

INTRODUCTION

Rural counties in the U.S. have higher rates of obesity,1,2,3 sedentary lifestyle,3,4 and associated chronic diseases1,5,6,7 than non-rural areas, yet treatment of obesity in the rural population has received little research attention. Efficacy trials, typically conducted with urban participants and delivered by experts working in academic medical centers, show that lifestyle interventions involving diet, exercise, and behavior modification produce clinically significant weight reductions.8,9,10,11 Nonetheless, participants commonly regain one-third to one-half of their lost weight during the year following treatment.8,12,13 If lost weight is not maintained, the health benefits associated with weight loss may not be sustained.8,14 Extended-care programs that include clinic-based follow-up sessions may improve the maintenance of lost weight.8,11,12,15 However, in rural communities, distance to health care centers represent a significant barrier to ongoing care.1,5,7 Therefore, it is important to examine alternative venues for the treatment of obesity as well as alternative methods of delivering extended care, such as the use of telephone counseling rather than face-to-face sessions.7

This randomized trial compared the effectiveness of extended-care programs designed to promote successful long-term weight management. Cooperative Extension Service (CES)16 offices in rural communities served as the venues for the trial. Participants completed a standard six-month lifestyle modification program and then were assigned randomly to telephone counseling, face-to-face counseling, or an education control group. We hypothesized that the interventions delivered either by telephone or by face-to-face sessions would produce better maintenance of lost weight than the control condition and that the beneficial effects of extended care would be mediated by improved adherence to behavioral weight-management strategies.

METHODS

Participants

The study included 234 women, 50–75 years of age, with a body-mass index (BMI, kg/m2) greater than 30 and a body weight less than 159.1 kg. Eligible participants were free of uncontrolled hypertension and diabetes and had no active (within 12 months) manifestations of cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, renal, or hepatic disease. The use of medications known to affect body weight and a weight loss of 4.5 kg or greater in the preceding six months also were exclusion criteria. Psychosocial contraindications included substance abuse and clinically significant depression.

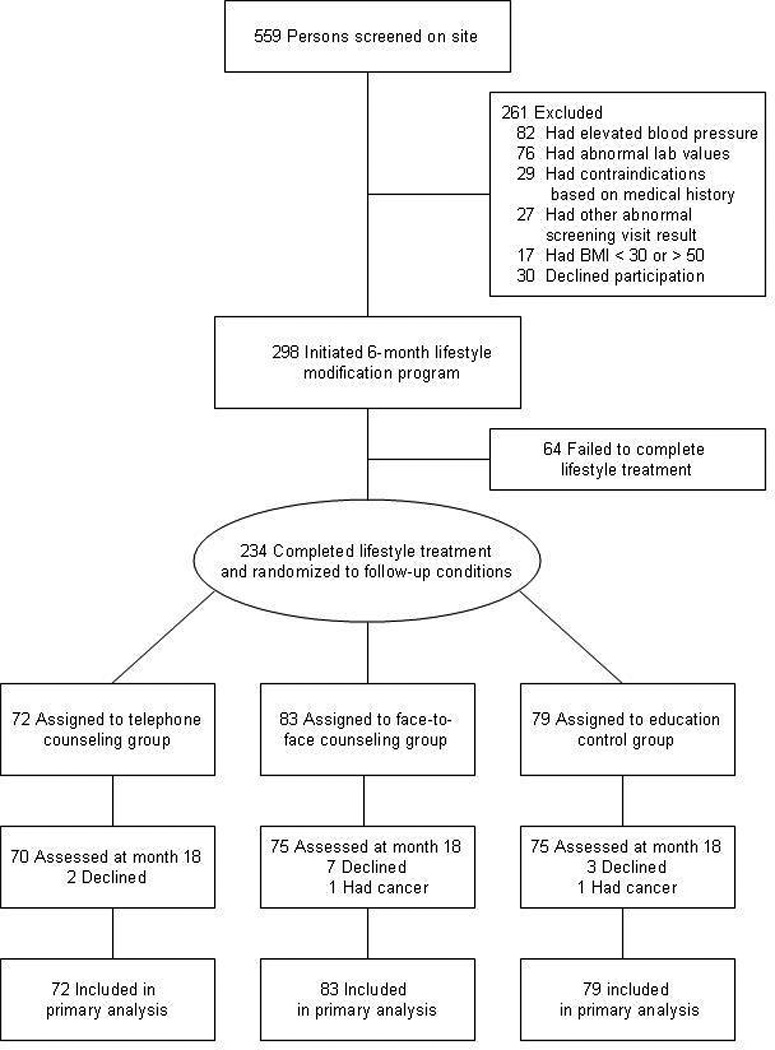

Study announcements were mailed to households in six rural17 counties in northern Florida. All six counties have been designated in whole or in part as “Health Professional Shortage Areas.”18 Five hundred and fifty-nine women who responded to the announcements were invited to an orientation/screening session iwherein the study was described and informed consent obtained. Height, weight, and blood pressure were measured by a registered nurse, who took a medical history, drew a fasting sample of blood, and obtained a 12-lead electrocardiogram. The blood sample was analyzed for metabolic and lipid profiles. Findings from the screening visit were reviewed by the study physician who determined medical eligibility; 261 women were excluded from participation (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of Enrollment, Randomization, and Follow-up

The remaining 298 women participated in a standard six-month lifestyle modification program for weight loss. The program was delivered in groups of 10–14 participants at local CES offices. Group leaders were CES Family and Consumer Sciences agents or individuals with bachelors or masters degrees in nutrition, exercise science, or psychology (hired by the University of Florida). Family and Consumer Sciences agents, (formerly known as “home economists”) have a minimum of a bachelors degree with education and training in food science, dietetics, and nutrition. The group leaders were provided with extensive training in lifestyle weight-loss treatment that included session-by-session supervisory contacts (1 hour each) and eight bimonthly workshops (6 hours each).

The contents of the lifestyle program were modeled after the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP)19 and included a low-calorie eating pattern (1200 kcal/day), increased physical activity (30 min/day of walking) and training in behavior modification strategies such as goal setting and daily self-monitoring of food intake.11,20 Modifications to the DPP approach included group rather than individual counseling21 and home-based rather than center-based exercise.22 We also included additions that our pilot testing suggested were issues of special concern to women from rural areas, such as cooking demonstrations to illustrate low-calorie preparation of “Southern” dishes, strategies for coping with a lack of family support for weight loss, and techniques for healthful eating while away from home.

A total of 234 women (78.5%) completed the initial lifestyle intervention; these participants comprised the sample for the randomized trial. The study, approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Florida, was conducted from June 2003 to May 2007.

Extended-Care Conditions

Prior to the start of the extended-care phase, participants in all conditions received written handouts describing how to use problem-solving strategies to deal with obstacles to the maintenance of lost weight.23 All participants were encouraged to continue using behavioral weight-control strategies, and they were asked to complete written self-monitoring logs of food intake on at least two weekdays and one weekend day per week. Participants in the telephone and education control groups were provided with postage-paid envelopes to return the records to the counselors. Participants in the face-to-face condition were asked to bring the records to their office-based sessions.

Telephone counseling

Seventy-two participants were assigned to receive individual telephone counseling that included 26 biweekly sessions conducted with the same counselors who led the initial lifestyle program. The telephone contacts were scheduled in advance. The sessions, 15–20 minutes in length, involved problem solving of barriers to the maintenance of eating and exercise behaviors required for sustaining lost weight. The counselors used the five-stage problem-solving model described by Perri et al.:23,24 (a) orientation (i.e., developing an appropriate coping perspective – “Problems are a normal part of managing your weight, but they can be dealt with effectively.”); (b) definition (i.e., specifying the problem and goal behaviors – “What is the particular problem facing you right now? What is your goal in this situation?”); (c) generation of alternatives (i.e., brainstorming potential solutions – “The greater the range of possible solutions you consider, the greater your chances of developing an effective solution.”); (d) decision making (i.e., anticipating the probable outcomes of different options – “What are the likely short- and long-term consequences of each of your options?”); and (e) implementation and evaluation (i.e., trying out a plan and evaluating its effectiveness – “What solution plan are your going to try and how will you know if it works?”).

Face-to-face counseling

Eighty-three participants were assigned to receive face-to-face counseling, which was comprised of 26 biweekly group sessions, conducted at the CES offices, by the same counselors who led the initial lifestyle program. These 60-minute sessions involved group problem solving of barriers to the maintenance of eating and exercise behaviors required for sustaining lost weight. The group leaders utilized the problem-solving model described above.

Education control

Seventy-nine participants were assigned to an education control condition. They received 26 biweekly newsletters that contained tips for maintaining weight-loss progress along with recipes for low-calorie meals. Prior to the extended-care phase, they received the same problem-solving handouts used in the telephone and face-to-face conditions.

Outcomes

Primary outcomes included changes in body weight and BMI during the one-year experimental period. Secondary outcomes included changes in selected cardiovascular risk factors (blood pressure, blood lipids, and glycemic control). Outcomes were measured at Months 6 and 18 by a mobile assessment team that included a registered nurse and medical technician who were masked to participants’ randomized assignment. Certified scales were used to measure participants’ weights. Blood pressure was measured after a five-minute rest. Levels of triglycerides, total cholesterol, low-density lipoprotein (LDL) cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, and glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c) were analyzed by Quest Diagnostics® from a blood sample obtained after an overnight fast.

Behavioral adherence was calculated by counting the number of self-monitoring records completed during the yearlong experimental period. The use of written self-monitoring, a central component of behavior modification interventions, represents the single behavioral strategy most closely associated with successful weight management.25,26,27,28

Attrition, Attendance, and Telephone Call Completion

Fourteen participants, 6% of the sample, were lost to follow-up (Figure 1). This number included any randomized participant who completed the initial lifestyle program and 6-month assessment but failed to return for the 18-month evaluation. There were no significant differences in attrition among groups. In the face-to-face condition, the mean (±SD) number of sessions attended was 13.8±8.6. In the telephone condition, the mean (±SD) number of completed telephone sessions was 21.1±5.7.

Statistical Analysis

The sample size was selected to provide a statistical power of .80 to detect a 2.5% difference in weight regain between groups (two-tailed testing with Bonferroni adjustments). We used a replicated Latin square design with county and session time serving as factors.

The data were analyzed using SAS software.29 Preliminary analyses revealed that a greater number of black women were randomized to the telephone group (P =0.04). There were no other significant differences among conditions in baseline characteristics (Table 1) or in changes in weight and other outcomes following the initial weight-loss program (Table 2). Three missing-not-at-random (MNAR) approaches were used to examine the data. Differences in weight and secondary outcomes between 6 and 18 months were analyzed using pattern mixture models.30 For each treatment group, we computed

where P is the proportion that did not complete extended care, (Y_18-Y_6) is the estimated difference in means for the completers, and Δ is a sensitivity parameter that corresponds to the difference in means for the study non-completers. Different values of Δ correspond to common missing data assumptions for participants who were lost to follow-up:

Δ = 3.6 corresponds to regaining 0.3 kg/month after leaving the study,

Δ = (Y_0 – Y_6) corresponds to returning to baseline weight, where Y_0 is the baseline weight and Y_6 is the weight after initial treatment (at 6 months), and

Δ = 0 corresponds to weight staying constant after Month 6.

Table 1.

Baseline Characteristics of Randomized Participantsa

| Characteristics | Telephone Counseling (n =72) |

Face-to-Face Counseling (n=83) |

Education Control Group (n=79) |

Randomized Population (n=234) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age, mean (SD), y | 59.8 (6.2) | 59.2 (6.2) | 58.6 (6.0) | 59.4 (6.1) |

| Race/Ethnicity, No. (%) | ||||

| Black, Non-Hispanicb | 21 (29.2) | 13 (15.7) | 9 (11.4) | 43 (18.3) |

| Hispanic | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.2) | 3 (3.8) | 5 (2.1) |

| White | 48 (66.7) | 69 (83.1) | 64 (81.0) | 181 (77.3) |

| Other (Asian, Native American, or Pacific Islander) |

2 (2.8) | 0 (0) | 3 (3.8) | 5 (2.1) |

| Education, No. (%) | ||||

| < 12 years | 26 (36.1) | 30 (36.1) | 32 (40.5) | 88 (37.6) |

| 13–15 years | 28 (38.9) | 41 (49.4) | 27 (34.2) | 96 (41.0) |

| > 16 years | 18 (25.0) | 12 (14.4) | 20 (25.3) | 50 (21.4) |

| Household income/y, No. (%) | ||||

| < $35,000 | 35 (48.6) | 44 (53.0) | 25 (31.6) | 104 (44.4) |

| $35,000 to $49,999 | 12 16.7) | 18 (21.7) | 21 (26.6) | 51 (21.8) |

| $50,000 to $74,999 | 14 (13.9) | 14 (16.9) | 18 (22.8) | 46 (19.7) |

| > $75,000 | 10 (13.9) | 6 (7.2) | 14 (17.7) | 30 (12.8) |

| Not reported | 1 (1.4) | 1 (1.2) | 1 (1.3) | 3 (1.3) |

| Body weight, mean (SD), kg | 96.4 (16.8) | 97.8 (14.3) | 95.0 (13.4) | 96.4 (15.6) |

| BMI, mean (SD), kg/m2 | 36.9 (5.7) | 37.1 (4.5) | 36.2 (4.3) | 36.8 (4.9) |

| Systolic BP, mean (SD), mm Hg | 125.4 (9.6) | 125.4 (9.6) | 126.6 (8.4) | 125.8 (9.2) |

| Diastolic BP, mean (SD), mm Hg | 74.4 (8.3) | 74.5 (8.0) | 76.2 (6.4) | 75.0 (7.6) |

| Triglycerides, mean (SD), mg/dl | 134.3 (64.2) | 150.8 (59.0) | 149.2 (60.4) | 145.2 (61.3) |

| Total Cholesterol, mean (SD) mg/dl | 206.1 (34.1) | 208.3 (29.1) | 206.1 (29.9) | 206.9 (30.9) |

| HDL-Cholesterol, mean (SD) mg/dl | 58.3 (14.6) | 54.8 (11.6) | 55.7 (13.1) | 56.2 (13.2) |

| LDL-Cholesterol, mean (SD) mg/dl | 120.9 (31.6) | 123.4 (27.7) | 120.5 (29.5) | 121.7 (29.4) |

| Glycosylated hemoglobin, mean (SD), % HbA1c | 6.0 (0.6) | 6.0 (0.8) | 5.8 (0.6) | 6.0 (0.7) |

Abbreviations: BMI, body mass index, calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared; BP = blood pressure.

SI conversion factors: To convert values for triglycerides to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.01129; to convert values for cholesterol to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.02586; to convert values for glucose to millimoles per liter, multiply by 0.05551.

All values are at the start of initial weight-loss program.

There was a larger proportion of black women assigned to the telephone condition than to the other groups (P = 0.04).

Table 2.

Changes in Outcomes During the 6-Month Initial Weight Loss Program

| Outcomea | Telephone Counseling (n =72) |

Face-to-Face Counseling (n=83) |

Education Control Group (n=79) |

Randomized Populationb (n=234) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Body weight, mean (SE), kg | −9.4 (0.6) | −10.1 (0.6) | −10.5 (0.6) | −10.0 (0.4) |

| BMI, mean (SE), kg/m2 | −3.6 (0.2) | −3.8 (0.2) | −4.0 (0.2) | −3.8 (0.1) |

| Waist (cm) | −8.1 (0.7) | −8.6 (0.6) | −8.2 (0.7) | −8.3 (0.4) |

| Systolic blood pressure, mean (SE), mm Hg |

−7.3 (1.4) | −7.6 (1.3) | −9.0 (1.3) | −8.0 (0.8) |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mean (SE), mm Hg |

−4.0 (1.0) | −3.3 (0.9) | −3.4 (0.9) | −3.5 (0.5) |

| Triglycerides, mean (SE), mg/dl | −14.0 (6.9) | −29.6 (6.7) | −17.6 (6.7) | −20.5 (3.0) |

| Total Cholesterol, mean (SE) mg/dl | −10.7 (3.6) | −18.8 (3.4) | −12.9 (3.5) | −14.2 (2.0) |

| HDL-Cholesterol, mean (SE) mg/dl | −3.7 (0.9) | −3.2 (0.9) | −3.3 (0.9) | −3.4 (0.5) |

| LDL-Cholesterol, mean (SE) mg/dl | −3.9 (3.3) | −9.7 (3.2) | −5.8 (3.2) | −6.5 (1.9) |

| Glycosylated hemoglobin, mean (SE), % HbA1c | −0.2 (0.1) | −0.3 (0.1) | −0.3 (0.1) | −0.3 (0.03) |

Missing values in the secondary outcomes were accounted for using SAS Proc Mixed28 under a missing at random assumption.

Significant changes in all outcomes were observed from Month 0 to Month 6 (all P values < 0.001) for the total study population, but there were no significant differences among the three groups on any outcomes prior to the start of the randomized, extended-care phase at Month 6.

The first scenario is based on the documented pattern of weight regain following lifestyle treatment.13,26,27 The second scenario assumes a return to baseline values for participants lost to follow-up.24,31 The third scenario is based on the less conservative but commonly used “last observation carried forward” approach,31 which assumes that participants lost to follow-up have fully maintained the progress observed at their last assessment visit. Because there is no consensus on the approach to missing data in weight-loss studies,31 we examined the data using three MNAR scenarios. However, all three approaches revealed the same pattern of significant findings. Because the rate of weight regain following lifestyle treatment has been well documented, we present the weight change outcomes according to the first scenario. Changes in cardiovascular risk factors during the year following lifestyle treatment are less well known; therefore, we present those outcomes according to the second scenario.

Finally, we fit linear regression models with treatment and adherence as covariates to test the hypothesis that adherence served as a mediator32 of the relationship between extended care and weight change from month 6 to 18.

Examination of Costs

We conducted an exploratory analysis to assess costs of the extended-care conditions from the perspective of both the participants and the program. Participants completed a cost questionnaire at enrollment, with updates at month 6 and 18. Information regarding time spent in extended-care activities, including counseling, program-related reading and record keeping, exercise, and other activities (e.g., trying new recipes) were included in the 18-month assessment.

Data regarding workforce participation and wages as valuations for time spent in program-related activities were collected at all time points. The overall median of self-reported wages ($10.50/hour) was used to value participant time. Travel costs for program participation were calculated for face-to-face participants using the self-reported round-trip mileage multiplied by a standard rate of 44.5¢/mile, plus an estimate of time spent in transit. Travel costs (distance and time) were multiplied by the number of face-to-face sessions attended. For the telephone condition, we assumed each participant completed the average number of telephone sessions. Other data needed to assess participant time were collected via the cost survey. For extreme outliers and cases with missing values, we substituted the median value for that study arm.

Costs of program operations, based on data collected by the research team, included the value of time for group leaders ($14.31/hour) and assistants ($11.45/hour) in all program-related activities, including preparation, session time, and training. Other program operating costs included telephone service for telephone counseling sessions, space rental fees for face-to-face counseling sessions, time and materials for preparing the newsletters, and staff time related to program administration.

RESULTS

Weight Changes

The mean (±SE) weight loss accomplished by the 234 women who completed the initial lifestyle modification program was 10.0±0.4 kg. There were no significant between-group differences in any outcome prior to the randomized phase of the trial (Table 2). At the conclusion of the initial lifestyle program, significant within-group improvements across all conditions were observed in blood pressure, blood lipids, and glycemic control (Table 2).

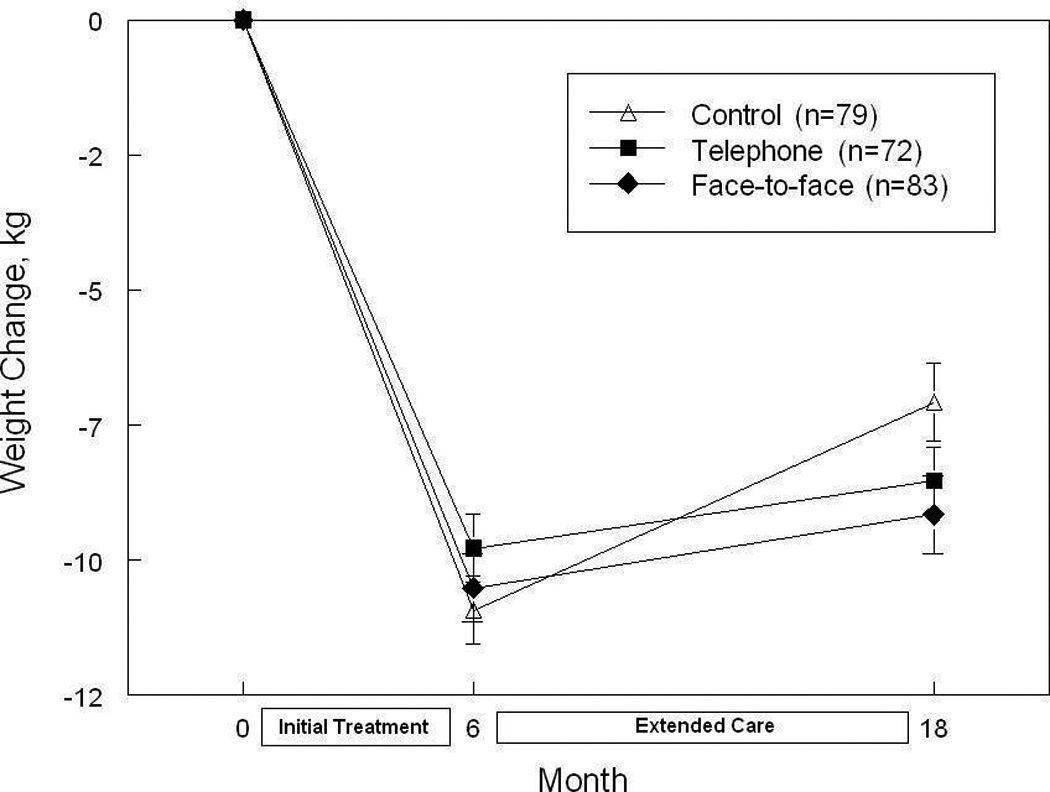

At the conclusion of the 12-month extended-care period, participants who received either telephone or face-to-face counseling regained less weight (1.3±0.6 and 1.2±0.7 kg) compared with those in the education control condition (3.7±0.6 kg; Ps=0.02 and 0.03, respectively; Figure 2). Similarly, telephone and face-to-face counseling resulted in significantly smaller increases in BMI (0.45±.27 and 0.44±.25 kg/m2), as compared with the education control group (1.42 ±.26 kg/m2, Ps=0.03 and 0.02, respectively). The effects for county and counselor on short- and long-term changes in weight were not significant.

Figure 2.

Weight Changes (mean ± SE) during the Initial Weight-Loss Phase (Months 0–6) and during the Extended-Care Phase (Months 6–18)

Secondary Outcomes

There were no significant between-group changes for the secondary outcomes (Table 3). The improvements in cardiovascular risk factors observed at Month 6 for the most part were maintained at Month 18. However, improvements in LDL- and total cholesterol observed at Month 6 were not sustained at Month 18 despite a mean decrease in body weight (from baseline) of more than 7%. Across the entire sample, weight gain was associated with a decrease in HDL-cholesterol (rho=-.24, P< 0.001) and with increases in triglycerides (rho=.28, P<0.001), and HbA1c (rho=.25, P < 0.001), but not with changes in LDL- (rho=.01, P=0.89) or total cholesterol (rho=.03, P=0.67).

Table 3.

Changes in Outcomes from Months 6 to 18 According to Extended-Care Condition

| Outcomea | Telephone Counseling (n =72) |

Face-to-Face Counseling (n=83) |

Education Control Group (n=79) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Body Weight, mean (SE), kg | 1.2 (0.7)b | 1.3 (0.6)b | 3.7 (0.7)c |

| BMI, mean (SE), kg/m2 | 0.45 (0.27)b | 0.44 (0.25)b | 1.42 (0.26)c |

| Systolic BP, mean (SE), mm Hg | 2.1 (1.4) | 3.1 (1.3) | 3.3 (1.3) |

| Diastolic BP, mean (SE), mm Hg | 2.5 (1.0) | 3.0 (0.9) | 1.1 (0.9) |

| Triglycerides, mean (SE), mg/dl | 1.4 (6.2) | 9.7 (5.5) | 6.1 (5.8) |

| Total cholesterol, mean (SE), mg/dl | 3.8 (3.6) | 11.6 (3.3)c | 11.6 (3.4)c |

| HDL-Cholesterol, mean (SE), mg/dl | 1.1 (0.9) | 2.8 (0.8)c | 2.7 (0.9)c |

| LDL-Cholesterol, mean (SE), mg/dl | 2.3 (3.2) | 6.9 (2.9)d | 8.0 (3.0)d |

| Glycosylated hemoglobin, mean (SE), HbA1c, % |

0.0 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.1) | 0.1 (0.1) |

Estimates for body weight and BMI were calculated using MNAR procedure in which participants lost to follow-up were assumed to have regained 0.3 kg per month since leaving the study. Estimates for other outcomes were completed using a MNAR procedure that corresponded to setting a sensitivity parameter equal to a value consistent with a baseline carried forward type of analysis.

P<0.05 (Bonferroni adjusted) for the between-group comparison vs. the control group.

P<0.01 (Bonferroni adjusted) for the within-group change from Month 6 to 18.

P<0.05 (Bonferroni adjusted) for the within-group change from Month 6 to 18.

Adherence

Adherence to behavioral weight-management strategies, as measured by the mean (±SE) number of days with self-monitoring records for food intake, was significantly higher in the telephone (131±12) and face-to-face (109±10) counseling arms, as compared with the control group (80±10; Ps=0.006 and 0.03, respectively). A significant relationship between adherence and weight changes during Months 6 to 18 was observed, with poorer adherence resulting in greater weight gain. A 10% decrease in adherence resulted in a weight gain of 0.9 kg (SE=1.3; P <0.001). Finally, controlling for the between-group differences in adherence reduced the effect of extended care to a non-significant level; the difference between the telephone and the control groups was reduced by more than 50% and the difference between the face-to-face and the control conditions was decreased by approximately 25%. Thus, the beneficial impact of extended care on weight management was mediated by adherence to behavioral self-management strategies.23

Costs

The pattern of costs across conditions showed that the face-to-face intervention incurred the highest costs, followed by the telephone condition, and then the educational control group (Table 4). The data for program costs and costs to the participant indicated the same pattern of findings. Face-to-face counseling entailed the largest costs to the participants due to the expenses associated with the travel required for session attendance. Program costs per participant were twice as high for the face-to-face intervention as compared with the telephone counseling condition due to greater staffing costs in the face-to-face condition.

Table 4.

Participant and Program Costs from Months 6 to 18 According to Extended-Care Condition

| Costs | Telephone Counseling (n=72) |

Face-to-Face Counseling (n=83) |

Education Control Group (n=79) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participant Costs | |||

| Reading/record keeping, mean (SD), hr | 16.0 (18.1) | 15.7 (18.9) | 10.4 (15.7) |

| Time in counseling, mean (SD), hr | 10.2 (12.4) | 21.3 (16.0) | N/A |

| Time spent exercising, mean (SD), hr | 109.2 (87.9) | 99.5 (88.8) | 110.9 (115.5) |

| Other program-related time, mean (SD), hr | 48.8 (64.5) | 35.5 (61.0) | 41.4 (85.3) |

| Travel time, mean (SD), hr | N/A | 13.4 (8.9) | N/A |

| Subtotal: program time, mean (SD), hr | 199.1 (136.7) | 185.4 (130.5) | 177.7 (161.2) |

| Travel distance, mean (SD), mi | N/A | 472.1 (477.6) | N/A |

| Total participant costs, mean (SD), $ | 1933 (1436) | 2157 (1449) | 1708 (1692) |

| Program Costsa | |||

| Interventionist time, mean (SD), hr | 63.0 (11.3) | 126.0 (0) | N/A |

| Program assistant time, mean (SD), hr | 24.0 (4.3) | 78.0 (0) | 104.0 (0) |

| Subtotal: personnel costs, mean (SD), $ | 1863 (162.3) | 3589 (0) | 1191 (0) |

| Other costs (e.g., telephone, postage, handouts, space rentalb), mean (SD), $ |

396.0 (6.5) |

1036.0 (6.5) | 163.9 (29.5) |

| Program costs/participant, mean (SD), $ | 191.5 (21.1) | 396.6 (73.2) | 115.8 (19.0) |

|

Total costs/participant (mean of participant costs + mean of program costs), $ |

2124.5 | 2554.6 | 1823.8 |

For certain program costs, such as interventionist time to conduct a face-to-face group session, there is no variation by number of participants, hence the SD is 0).

The extension offices provided the space without charge for this study. However, given that the space available was limited and available on a competitive basis, we estimated the value based on rental charges for similar space by local churches in these communities.

DISCUSSION

This study demonstrated that 12-month extended-care programs delivered either by telephone counseling or by face-to-face sessions significantly improved the maintenance of lost weight. Obese women from medically underserved rural counties, who initially lost a mean (±SE) of 10.0±0.4 kg via lifestyle modification, regained smaller amounts of weight when provided with telephone counseling (1.3±0.7 kg) or face-to-face sessions (1.2±0.6 kg) as compared to participants assigned to an education control group (3.7±0.6 kg). Similarly, during the 12 months following initial treatment, the control group experienced an increase in BMI that was three times larger than the changes observed in the telephone and face-to-face counseling conditions.

The TOURS Trial is the first randomized controlled trial to demonstrate the effectiveness of telephone counseling for the long-term management of obesity in rural communities. Because distance represents a major barrier to medical care in rural areas,1,5,7 the availability of a treatment modality that does not require time and costs for travel and attendance at clinic visits represents a potentially important approach to providing ongoing care to rural residents. Moreover, in the present study, delivering extended care via telephone was less costly than providing face-to-face sessions. Travel expenses associated with the face-to-face program resulted in higher participant costs compared with the telephone condition (means=$2,157 vs. $1,933), and program costs per participant were twice as high for the face-to-face treatment compared with telephone counseling (means= $397 vs. $192) due to fixed program costs of conducting on-site sessions.

Both the telephone and face-to-face counseling programs employed a structured problem-solving model23 to guide clinical decision making, and both encouraged the continued use of behavioral self-regulation strategies,33 particularly the self-monitoring of food intake.27,34 Our findings showed higher levels of adherence to this recommendation in the telephone and face-to-face conditions, compared with the control group. Consistent with self-regulation theory,35,36 which emphasizes the integral role of vigilance (i.e., self-monitoring) in behavior change, we hypothesized that the relationship between extended-care counseling and long-term weight loss success would be mediated by the completion of food records during Months 6 to 18. Our findings, which supported this hypothesis, highlight the critical role that vigilant monitoring of food intake may play in the maintenance of lost weight.28,36

Several potential limitations of our study should be noted. Middle-aged and older obese women who completed an initial program of lifestyle modification comprised the study sample. The generalizability of our findings to the treatment of men, younger women, and those who drop out of initial treatment is unknown. We chose to focus on women, ages 50–75 years of age, for several reasons. The World Health Organization37 has noted that the time of menopause and the two decades following it are associated with weight gain, and the WHO has emphasized the need for interventions that specifically target weight loss and increased physical activity in obese women 50 years and older. Moreover, for women, but not men, obesity poses a greater burden with regard to decreased quality of life38 and increased rates of depression,39 and women over 50 in rural areas experience higher rates of obesity,1 depression,40 and heart disease1 than their urban counterparts.

The design of this trial did not permit an examination of the independent effects of changes in diet composition, physical activity, and weight change on the secondary outcomes. The maintenance of lost weight was associated with sustained improvement in some but not all secondary outcomes. From baseline to Month 18, the study population demonstrated an overall mean (+SE) weight loss of 7.9±0.7, which was accompanied by significant decreases in systolic blood pressure (−5.2±0.8 mm Hg), triglycerides (−14.8±3.4 mg/dl), and glycosylated hemoglobin (−2.1±.0.4%). However, the improvements in LDL- and total cholesterol observed at Month 6 were not sustained at Month 18, yet the increases in LDL- and total cholesterol from Months 6 to 18 were not associated with a regaining of lost weight. These findings imply that a return toward baseline dietary composition patterns, rather than weight regain, may account for the lack of sustained improvement in LDL- and total cholesterol.41

An additional study limitation involves the intensity of treatment provided to participants in this trial. Our initial program of lifestyle modification and our extended-care interventions provided a high frequency of contacts—a total of 50 sessions over 18 months. This level of treatment intensity is comparable to that provided in efficacy trials such as the DPP9 and the Look AHEAD Study.10 Indeed, the magnitude of weight reductions achieved with economically disadvantaged participants in the rural communities of the current study compares quite favorably to the weight losses achieved in large multi-site trials, conducted in academic medical centers with middle-class participants.9,10,12 Nonetheless, the intensity of our intervention may represent a barrier to wide-spread dissemination. Future studies should examine the effectiveness of lower doses of initial treatment and extended care.

The translation of findings derived from efficacy trials to community-based practices represents a key objective of the NIH Roadmap initiative.42 Most obesity treatment studies have been conducted in the resource-rich environments of academic medical centers, and few studies have translated efficacious interventions such as the DPP for dissemination into medically underserved community settings.43,44 Delivering lifestyle interventions via the existing infrastructure of CES16 represents a potentially effective and efficient means of research translation into rural communities with limited access to preventive health services.1,7 With offices in almost all 3,100 counties of the U.S., the CES16 could make a significant contribution toward reducing geographic disparities in access to preventive health services—an objective of high national priority as detailed in Healthy People 2010.45

In summary, the results of the TOURS Trial support the NIH Guidelines8 that recommend “continuous care” for the management of obesity. Our findings highlight the benefits of extended-care interventions11,39 and indicate that telephone counseling represents an effective and cost-efficient approach to the management of obesity in underserved rural settings.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support: This study was supported by a Demonstration and Dissemination Grant from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute, R18 HL073326.

Role of the Sponsor: The study sponsor did not participate in the design or conduct of the trial or in preparation of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Author Contributions: Dr. Perri had full access to all of the data in the study and takes full responsibility for the integrity and accuracy of the data analysis

Study concept and design: Perri, Limacher, Lutes, Bobroff, Dale, & Martin

Acquisition of data: Perri, Limacher, Durning, Janicke, Lutes, Dale, & Martin

Analysis and interpretation of data: Perri, Limacher, Durning, Lutes, Bobroff, Daniels, Radcliff, & Martin

Drafting of the manuscript: Perri, Daniels, Janicke, & Radcliff

Critical revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Perri, Limacher, Durning, Janicke, Lutes, Bobroff, Dale, Daniels, Radcliff, & Martin

Statistical analysis: Daniels, Radcliff

Obtained funding: Perri

Administrative, technical, or material support: Perri, Limacher, Durning, Janicke, Lutes, Bobroff, Dale, Radcliff, & Martin

Study supervision: Perri, Limacher, Janicke, Lutes, Dale, & Martin.

Financial Disclosures: Dr. Perri and Dr. Limacher have received grant support from Orexigen Therapeutics.

Additional Contributions: We are indebted to Marcia Stefanick, Ph.D., Ronald Prineas, M.D., and John Foreyt, Ph.D., who served on the study’s Data and Safety Monitoring Board, to Catherine Loria, Ph.D., from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, to the University of Florida IFAS Cooperative Extension Service Offices in Bradford, Columbia, Dixie, Lafayette, Levy, and Putnam Counties, Florida, and to the staff of the University of Florida Weight Management Program for their contributions to the completion of this trial.

REFERENCES

- 1.Eberhardt MS, Ingram DD, Makuc DM, et al. Health, United States, 2001. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2001. Urban and rural health chartbook. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jackson JE, Doescher MP, Jerant AF, et al. A national study of obesity prevalence and trends by type of rural county. J Rural Health. 2005;21:140–148. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2005.tb00074.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lutfiyya MN, Lipsky MS, Wisdom-Behounek J, et al. Is rural residency a risk factor for overweight and obesity for U.S.children? Obesity. 2007;15:2348–2356. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Patterson PD, Moore CG, Probst JC, et al. Obesity and physical inactivity in rural America. J Rural Health. 2004;20:151–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-0361.2004.tb00022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Phillips CD, McLeroy KR. Health in rural America: remembering the importance of place. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:1660–1663. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.10.1661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barnett E, Halverson J. Disparities in premature coronary heart disease mortality by region and urbanicity among black and white adults ages 35–64, 1985–1995. Public Health Rep. 2000;115:52–64. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gamm LD, Hutchison LL, Dabney BJ, et al., editors. Rural Healthy People 2010: A Companion Document to Healthy People 2010. Vols. 1–3. College Station, TX: Texas A&M University System Health Science Center, School of Rural Public Health, Southwest Rural Health Research Center; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Institutes of Health, National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Clinical guidelines on the identification, evaluation, and treatment of overweight and obesity in adults: The evidence report. Obes Res. 1998;6:51S–209S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group. Reduction in the incidence of type 2 diabetes with lifestyle intervention or metformin. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:393–403. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa012512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.The Look AHEAD Research Group. Reduction in weight and cardiovascular disease risk factors in individuals with type 2 diabetes: one-year results of the Look AHEAD trial. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1374–1383. doi: 10.2337/dc07-0048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wadden TA, Butryn ML, Wilson C. Lifestyle modification for the management of obesity. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2226–2238. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.051. Erratum in: Gastroenterology 2007;133:371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Svetkey LP, Stevens VJ, Brantley PJ, et al. Comparison of strategies for sustaining weight loss: the Weight Loss Maintenance Randomized Controlled Trial. JAMA. 2008;299:1139–1148. doi: 10.1001/jama.299.10.1139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jeffery RW, Drewnowski A, Epstein LH, et al. Long-term maintenance of weight loss: Current status. Health Psychol. 2000;19:5–16. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.19.suppl1.5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wadden TA, Anderson DA, Foster GD. Two-year changes in lipids and lipoproteins associated with the maintenance of a 5% to 10% reduction in initial weight: some findings and some questions. Obes Res. 1999;7:170–178. doi: 10.1002/j.1550-8528.1999.tb00699.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perri MG, Corsica JA. Improving the maintenance of weight lost in behavioral treatment of obesity. In: Wadden TA, Stunkard AJ, editors. Handbook of obesity treatment. 3rd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Guilford; 2002. pp. 357–379. [Google Scholar]

- 16.United States Department of Agriculture, Cooperative State, Research, Education, and Extension Service. [Accessed October 22, 2007]; doi: 10.1095/biolreprod.105.048686. ( http://www.csrees.usda.gov/qlinks/extension.html.) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.US Department of Agriculture and Economic Research Services. Measuring rurality: Rural-urban continuum codes. [Accessed October 22, 2007]; ( http://www.ers.usda.gov/Briefing/Rurality/RuralUrbCon.)

- 18.US Department of Health and Human Services. [Accessed October 21, 2007];List of designated primary medical care, mental health, and dental health professional shortage areas. ( http://bhpr.hrsa.gov/shortage.)

- 19.The Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP): description of lifestyle intervention. Diabetes Care. 2002;25:2165–2171. doi: 10.2337/diacare.25.12.2165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wing RR. Behavioral approaches to the treatment of obesity. In: Bray GA, Bouchard C, editors. Handbook of Obesity: Clinical Applications. 2nd ed. New York: Marcel Dekker; 2004. pp. 147–167. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Renjilian DA, Perri MG, Nezu A, et al. Individual versus group therapy for obesity: effects of matching participants to their treatment preferences. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:717–721. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Perri MG, Martin AD, Leermakers EA, et al. Effects of group- versus home-based exercise in the treatment of obesity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 1997;65:278–285. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.65.2.278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perri MG, Nezu AM, Viegener BJ. Improving the long-term management of obesity: Theory research, and clinical guidelines. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Perri MG, Nezu AM, McKelvey WF, et al. Relapse prevention training and problem-solving therapy in the long-term management of obesity. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2001;69:722–726. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Baker RC, Kirschenbaum DS. Self-monitoring may be necessary for successful weight control. Behav Ther. 1993;24:377–394. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wadden TA, Berkowitz RJ, Sarwer DB, et al. Benefits of lifestyle modification in the pharmacologic treatment of obesity. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:218–227. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.2.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wadden TA, Berkowitz RI, Womble LG, et al. Randomized trial of lifestyle modification and pharmacotherapy for obesity. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:2111–2120. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa050156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Streit KJ, Stevens NH, Stevens VJ, et al. Food records: A predictor and modifier of weight change in a long-term weight loss program. J Am Diet Assoc. 1991;91:213–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.SAS Institute, Inc. SAS System, Version 9.1. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Little RJA. A class of pattern-mixture models for normal missing data. Biometrika. 1994;81:471–483. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Streiner DL. The case of the missing data: methods of dealing with dropouts and other research vagaries. Can J Psychiatry. 2002;47:68–75. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baron RM, Kenny DA. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J Personal Soc Psychol. 1986;51:1173–1182. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.51.6.1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Foster GD. Clinical implications for the treatment of obesity. Obesity. 2006;14:S182–S185. doi: 10.1038/oby.2006.303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Helsel DL, Jakicic JM, Otto AD. Comparison of techniques for self-monitoring eating and exercise behaviors on weight loss in a correspondence-based intervention. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:1807–1810. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kanfer FH, Gaelick-Buys L. In: Self-management methods. In. Helping people change: a textbook of methods. 4th ed. Kanfer FH, Goldstein AP, editors. New York: Pergamon; 1991. 1991. pp. 305–360. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wing RR, Tate DF, Gorin AA, et al. A self-regulation program for maintenance of weight loss. N Eng J Med. 2006;355:1563–1571. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa061883. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.World Health Organization. Obesity: Preventing and managing the global epidemic (Publication No. WHO/NUT/NCD/98.1) Geneva: World Health Organization; 1998. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wadden TA, Womble LG, Stunkard AJ, et al. Psychosocial consequences of obesity and weight loss. In: Wadden TA, Stunkard AJ, editors. Handbook of obesity treatment. New York: Guilford Press; 2002. pp. 144–169. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carpenter KM, Hasin DS, Allison DB, et al. Relationship between obesity and DSM-IV major depressive disorder, suicide ideation, and suicide attempts: Results from a general population study. Am J Public Health. 2000;90:251–257. doi: 10.2105/ajph.90.2.251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Blazer DG, Kessler RC, McGonagle KA, et al. The prevalence and distribution of major depression in a national community sample: The National Comorbidity Survey. Am J Psychiat. 1994;151:979–986. doi: 10.1176/ajp.151.7.979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Executive summary of the third report of the National Cholesterol Education Program (NCEP) expert panel on detection, evaluation and treatment of high blood cholesterol in adults (Adult Treatment Panel III) JAMA. 2001;285:2486–2497. doi: 10.1001/jama.285.19.2486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zerhouni EA. Translational and clinical science – time for a new vision. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1621–1623. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsb053723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kerner J, Rimer B, Emmons K. Introduction to the special section on dissemination: Dissemination research and research dissemination: how can we close the gap? Health Psychol. 2005;24:443–446. doi: 10.1037/0278-6133.24.5.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McTigue KM, Harris R, Hemphill B, et al. Screening and intervention for obesity in adults: summary of the evidence for the U.S. Preventive Service Task Force. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:933–949. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-11-200312020-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.US Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy people 2010: With understanding and improving health and objectives for improving health. Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office; 2000. [Google Scholar]