Abstract

Decades of clinical and basic research indicate significant links between altered hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA)-axis hormone dynamics and major depressive disorder (MDD). Recent neuroimaging studies of MDD highlight abnormalities in stress response circuitry regions which play a role in the regulation of the HPA-axes. However, there is a dearth of research examining these systems in parallel, especially as related to potential trait characteristics. The current study addresses this gap by investigating neural responses to a mild visual stress challenge with real-time assessment of adrenal hormones in women with MDD in remission and controls. 15 women with recurrent MDD in remission (rMDD) and 15 healthy control women were scanned on a 3T Siemens MR scanner while viewing neutral and negative (stress-evoking) stimuli. Blood samples were obtained before, during, and after scanning for measurement of HPA-axis hormone levels. Compared to controls, rMDD women demonstrated higher anxiety ratings, increased cortisol levels, and hyperactivation in the amygdala and hippocampus, p<0.05, FWE-corrected in response to the stress challenge. Among rMDD women, amygdala activation was negatively related to cortisol changes and positively associated with duration of remission. Findings presented here provide evidence for differential effects of altered HPA-axis hormone dynamics on hyperactivity in stress response circuitry regions elicited by a well-validated stress paradigm in women with recurrent MDD in remission.

Keywords: depression, stress, HPA-axis, sex differences, fMRI

1. INTRODUCTION

Major depressive disorder (MDD) is the fourth leading cause of disease burden worldwide (Ustun et al., 2004), and the incidence in women is twice that of men (Kendler et al., 2006). Thus, understanding the pathophysiology of MDD has widespread implications for attenuation and prevention (Ustun et al., 2004), particularly in women. Studies have implicated abnormal hormone dynamics in mood disorders, supporting the involvement of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA)-axis in MDD (Plotsky et al., 1998, Young and Korszun, 2002). In fact, hormonal dysregulation in women has been found to precede MDD onset (Harlow et al., 2003), suggesting it reflects underlying subsyndromal MDD expression. Despite these findings, there are few studies characterizing the neurobiological pathways associated with the co-occurrence of mood-related brain circuitry deficits and altered hormone secretion.

Human studies demonstrate consistent HPA-axis abnormalities associated with MDD, specifically hypercortisolemia as reflected by elevated levels of cortisol in plasma, cerebrospinal fluid, and 24h urine (Carroll et al., 1976a, Carroll et al., 1976b) at baseline and in response to psychological stress (Burke et al., 2005). Lower DHEAS (an androgen precursor produced by the adrenal gland) (Young et al., 2002) levels have been reported, with mixed results regarding adrenocorticotropin hormone (ACTH) levels (Kalin et al., 1982, Linkowski et al., 1985, Deuschle et al., 1997, Posener et al., 2000, Young et al., 2001). HPA-axis abnormalities such as elevated cortisol, which is positively associated with age (Nelson et al., 1984) and number of episodes (Sher et al., 2004), may be implicated in vulnerability to MDD (or a trait) and not only related to clinical state (Vreeburg et al., 2009).

The comorbidity between depression and disordered HPA-axis hormone dynamics is not surprising from a brain circuitry point of view, given that MDD is a disorder which involves hypothalamic nuclei, amygdala, hippocampus, anterior cingulate cortex (ACC), subgenual ACC (sgACC), and medial and orbitofrontal cortex (mPFC, OFC) (Dougherty and Rauch, 1997, Mayberg, 1997, Drevets, 1999, Sheline et al., 2001), regions dense in glucocorticoid receptors (McEwen et al., 1986). Most consistently, evidence supports hyperactivation of several of these limbic regions in response to negative stimuli in MDD, as demonstrated by recent meta-analyses of functional neuroimaging studies employing emotion paradigms (Delvecchio et al., 2012, Hamilton et al., 2012). However, the vast majority of these studies have focused on state characteristics (i.e., individuals currently in a major depressive episode). In the few investigations of potential trait markers in the brain [i.e., in remitted depression (rMDD)], results appear less consistent, with mixed reports of hyperactivation or hypoactivation of the amygdala, PFC, and ACC compared to controls (Hooley et al., 2005, Ramel et al., 2007, Wang et al., 2008, Okada et al., 2009, Holsen et al., 2011, Dichter et al., 2012, Kerestes et al., 2012), likely due to differences in study design (i.e., cognitive vs. emotional paradigms).

Collectively, these brain regions implicated in MDD overlap substantially with the neural circuitry involved in arousal and response to stressful events (Fuchs et al., 1985, Keverne, 1988, Price, 1999). Neuroimaging studies designed to evoke a stress response in healthy adults report activation in these same regions (hypothalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, ACC, mPFC, and OFC) using a variety of paradigms, including sadness induction (Ottowitz et al., 2004), passive viewing of negative valence, high arousal stimuli (Goldstein et al., 2005, van Stegeren et al., 2007, Cunningham-Bussel et al., 2009, Root et al., 2009, Goldstein et al., 2010b), and psychosocial stressors such as the Montreal Imaging Stress Task, which involves a mental arithmetic task and continuous negative feedback on task performance (Wang et al., 2007, Pruessner et al., 2008).

Concurrent measurement of endogenous cortisol secretion (usually salivary cortisol) during these stress paradigms has allowed for investigation of relationships between brain activity and HPA-axis responsivity. In response to psychosocial stressors, findings appear highly variable, with some reporting increases in the PFC and OFC related to pre- to post-stressor change in cortisol (Wang et al., 2007) and others showing decreases in the hypothalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, OFC, and ACC in cortisol “responders” (i.e., those classified based on an increase in cortisol following the stressor) (Pruessner et al., 2008). For passive viewing of negative stimuli paradigms, negative relationships between cortisol reactivity and ventromedial PFC activity (Root et al., 2009) and negative correlations between cortisol levels and activation of the amygdala were observed (Pruessner et al., 2008, Cunningham-Bussel et al., 2009), although the reverse (positive association between limbic activation and cortisol change) has also been shown (van Stegeren et al., 2007, Root et al., 2009). These inconsistencies could be driven by methodological approaches (pre-/post-stress cortisol change vs. diurnal cortisol amplitude), as well as the substantial individual differences (even amongst health controls) which exist in the cortisol response, introducing significant variability in the main outcome measure. Exogenous cortisol administration, conversely, is associated with decreased activation of the amygdala and hippocampus during rest in healthy controls (Lovallo et al., 2010).

Few studies have concurrently examined neural functioning and HPA-axis responsivity in depression. In early FDG-PET studies, endogenous plasma cortisol levels (obtained at one timepoint just prior to the PET scan, thus conceptualized as reflecting response to the “stress” of the scanning environment) were positively associated with glucose metabolism in the amygdala (but not the hippocampus) in individuals with MDD (Drevets et al., 2002b), as well as the pre- to post-treatment change in glucose metabolism in the amygdala (Drevets et al., 2002a). Further, although endogenous salivary cortisol levels did not change in response to an emotional memory fMRI paradigm in either MDD or control subjects, during administration of exogenous cortisol (hydrocortisone vs. placebo), MDD women demonstrated greater hippocampal activation during encoding of neutral words compared to healthy women (Abercrombie et al., 2011). These studies point to important potential relationships between limbic dysfunction and abnormalities in the HPA-axis in MDD.

However, it remains unclear the degree to which individuals with depression demonstrate abnormalities in relationships between endogenous cortisol levels and brain activity, as measured in parallel and in response to an established stress paradigm. Furthermore, studies to date have not focused on potential trait features of depression (i.e., those in remission), despite evidence that brain activity (Hooley et al., 2005, Wang et al., 2008, Okada et al., 2009, Holsen et al., 2011, Dichter et al., 2012, Kerestes et al., 2012) and HPA-axis (Kathol, 1985, Deshauer et al., 1999, Bhagwagar et al., 2003, Vreeburg et al., 2009, Morris et al., 2012) abnormalities may persist following recovery and thus signal a potential vulnerability to relapse. Thus, building on our previous findings (Holsen et al., 2011), the current study was designed to address the importance of integrating hormone-brain associations in a sample of women with recurrent MDD in remission (rMDD) using a mild stress response fMRI paradigm (viewing of negative and neutral stimuli) in parallel with plasma hormone assessments of HPA-axis responsivity. We hypothesized that compared to controls, rMDD women would demonstrate significant differences in HPA-axis hormones, dysfunction in hypothalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, ACC, sgACC, OFC, and mPFC in response to a mild stress challenge, and that cortisol and/or ACTH levels would account for significant variance in between-group differences in brain activation.

2. EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

2.1. Sample

Participants were selected from the 17,741 Boston and Providence pregnancies from the Collaborative Perinatal Project (CPP), known as the New England Family Study (NEFS) (Goldstein et al., 2010a). The CPP was initiated over 40 years ago to investigate prospectively the prenatal and familial antecedents of pediatric, neurological, and psychological disorders of childhood (Niswander and Gordon, 1972). Women (recruited 1959–1966) were representative of patients receiving prenatal care, thus unselected for psychiatric status. Across NIMH-funded adult follow-up studies of their offspring, we identified 1214 subjects, 508 diagnosed with DSM-IV major depressive disorder (MDD) and 706 healthy controls (HCs) (ORWH-NIMH P50 SCOR MH082679). Systematic structured clinical interviews on all potential subjects were conducted by trained M.A.-level clinical interviewers. Expert diagnosticians (including J.M.G. and J. Donatelli) reviewed all information to determine final best estimate diagnoses. Of 508 MDD cases, 205 had recurrent episodes, of which 148 were women. Cases thus represented a truly general population sample of women with MDD.

Of these, we re-recruited for brain imaging 15 recurrent MDD women who were in remission (rMDD) and 15 healthy control women (HC) comparable on ethnicity (all Caucasian), right-handedness, socioeconomic status, and general intelligence (see Table 1). Selection of this subsample for brain imaging was based on current mood status and other eligibility criteria. Due to recruitment of their mothers during the NEFS study period (1959–1966), all women were between ages 43–50 years with rMDD women slightly older than HCs. rMDD women had generally experienced two or more episodes (two experienced only one lengthy episode rather than discrete multiple episodes); one woman with more than two episodes had a seasonal pattern. Full remission was defined as not having experienced any MDD symptoms for >30 days prior to scanning. One woman was in partial remission due to continuing loss of interest and mild guilt, but no other symptoms. Healthy controls did not meet DSM-IV criteria for any current Axis 1 disorders. Comorbid current (in the rMDD group) and past (rMDD and HC groups) Axis 1 diagnoses are reported in Table 1. Among rMDD, one woman reported a previous MDD psychiatric hospitalization, seven reported previous psychotherapy, thirteen had previous medication trials, and only six were currently taking psychotropic medication (listed in Table 1). HCs were not taking any psychotropic medication. No rMDD or HC subjects were taking oral contraceptives or hormone replacement therapy.

Table 1.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics in Depressed and Healthy Women

| Characteristic | Healthy Controls (HC) (n=15) |

Remitted MDD Women (rMDD) (n=15) |

Between-Group Comparisons |

t | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||||

| Age (years) | 45.1 | 2.2 | 47.4 | 2.1 | MDD > HC | 3.06 | 0.005 |

| BMI | 28.0 | 7.3 | 28.9 | 6.0 | |||

| Parental SESa | 5.8 | 1.9 | 5.9 | 1.6 | |||

| Education (years) | 14.4 | 2.0 | 14.4 | 1.9 | |||

| Estimated Full Scale IQb | 106.1 | 14.29 | 105.3 | 13.1 | |||

| Age at symptom onset (years) | -- | -- | 24.6 | 8.9 | |||

| Duration of illness (years) | -- | -- | 22.4 | 9.2 | |||

| Duration of remission (years) | -- | -- | 4.6 | 5.0 | |||

| n | % | n | % | ||||

| Handedness (right) c | 14 | 93.3 | 13 | 86.7 | |||

| Ethnicity (% Caucasian) | 15 | 100 | 15 | 100 | |||

| Current psychotropic medicationd | -- | -- | 6 | 40 | |||

| Comorbid diagnosis | |||||||

| Currente | -- | -- | 6 | 40.0 | |||

| Pastf | 1 | 6.7 | 7 | 46.7 | |||

Parental socioeconomic status (SES) was a composite index of family income, education, and occupation and ranged from 0.0 (low) to 9.5 (high).

Full Scale IQ estimated using the sum of age-scaled scores from the WAIS-R Vocabulary and Block Design subtests, and the conversion table C-37 from Sattler, 1992 (p. 851). Sattler, J. (1992). Assessment of Children, 3rd Edition. San Diego: Jerome Sattler.

Data available on 14 of 15 HC subjects and 15 of 15 rMDD subjects.

Six rMDD women were currently taking psychotropic medications: four were taking a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI; fluoxetine [three] or citalopram [one]), one was taking an SSRI (sertraline) in combination with buproprion, one was taking a serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor (venlafaxine) in combination with buproprion.

Current comorbid Axis 1 diagnoses in the rMDD group included: one subject with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; one with Anxiety Disorder, NOS; four subjects with Panic Disorder, without Agorophobia; one subject with Dysthymic Disorder; and one subject with Specific Phobia, Situational Type. In the HC group, there were no subjects with current Axis 1 diagnoses.

Past comorbid Axis 1 diagnoses in the rMDD group included: six subjects with Alcohol Abuse; one subject with Alcohol Dependence; one subject with Cannabis Abuse; one subject with Cocaine Abuse; one subject with Sedative Dependence; and one subject with Panic Disorder, with Agorophobia. In the HC group, past Axis 1 diagnoses included one subject with Caffeine-Induced Anxiety Disorder.

2.2. Procedures

Human subjects and methods approval was granted by Partners Healthcare and Brown University. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Subjects tracked their cycles for three to four months. Findings from the late follicular/midcycle menstrual phase (days 10–15 assessed by patient history) are presented here. Groups did not differ on mean cycle day (M=13.56, t=0.24; n.s.). On the morning of the study visit, rMDD women completed the 17-item Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression [HAM-D] with trained study staff to assess current mood state. All subjects scored less than eight [except for the subject in partial remission (HAM-D score = 11)], indicating they were not clinically symptomatic (10 of 15 scored less than four) and thus findings would represent potential MDD “trait” characteristics rather than “clinical state”. Mood and anxiety levels were assessed using the Profile of Mood States (POMS) and the Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) administered pre- and post-scanning.

Our method for acquiring HPA-axis hormone level changes in response to the visual stress challenge “in real time” using serial blood samples was applied here. Trained nurses inserted a saline-lock IV line in the non-dominant forearm. Blood acquisition commenced during fMRI scanning, with an in-scanner blood draw (Time 0; 1020h) drawn approximately 5 minutes after the subject was introduced into the magnet (after the first few MRI set-up scans) and just prior to the start of the stress paradigm. A 15 min in-scanner blood sample was drawn after the first two runs of the stress paradigm at 1035h, followed by a 30 min in-scanner blood draw at 1050h, and 60 min and 90 min blood draws, out-of-scanner in a quiet room, at approximately 1120h and 1150h, respectively. Subjects remained inside the bore of the magnet during in-scanner blood draws. The timing of these blood draws was based on the expected peak response (following the onset of the visual stress challenge) of ACTH at 15–30 min and cortisol at approximately 60 min. Hormone data were missing or not reported for some subjects due to poor IV access preventing blood acquisition during scanning (four HC; one rMDD) or difficulty with blood draw at one timepoint during scanning (one MDD for ACTH at Time 30).

Approximately 30cc of blood were sampled at each time point, allowed to clot for 45–60 min, spun, aliquoted, and stored frozen at −80 °C. Serum hormones were analyzed in duplicate with commercial immunoassay kits: cortisol (0.04 ug/dL;000000 4.4–6.7%); ACTH (1.5 pg/mL; 2.5– 5.5%): Immunoradiometric Assay (IRMA), DiaSorin, Inc., Stillwater, MN. Given significant differences in individual cortisol and ACTH responses, subjects were classified according to whether they demonstrated increases (responders) or decreases (non-responders) in serum hormone levels following onset of the stress paradigm (i.e. from Time 0) through the expected peak response time. For responders, change in each hormone (cortisol, ACTH) was measured by subtracting the basal from the peak level.

Functional MRI (fMRI) scanning was conducted using Siemens Tim Trio 3T MR scanner with a 12-channel head coil.180 functional volumes were acquired using a spin echo, T2*- weighted sequence (TR=2000 ms; TE=40 ms; FOV=200×200 mm; matrix=64×64; in-plane resolution=3.125 mm; slice thickness=5 mm; 23 contiguous slices aligned to the AC-PC plane). A visual stimuli task paradigm was presented to evoke a mild stress response, adapted from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS) and described and validated in our previous publications (Goldstein et al., 2005, Goldstein et al., 2010b, Holsen et al., 2011). Briefly, participants viewed fixation, neutral, and negative [according to affective valence (unpleasant/neutral) and arousal (high/low)] images, and pressed a button when a new image appeared in order to ensure attention. The mild stress paradigm lasted approximately 18 minutes (3 runs of 6 minutes each). For additional experimental details see (Holsen et al., 2011). After the fMRI session, participants were shown two blocks of negative and neutral images (presented on a laptop computer) and provided subjective ratings of arousal.

2.3. Data analysis

fMRI data were preprocessed using Statistical Parametric Mapping (SPM8) (Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, 2008) and custom routines in MATLAB (Mathworks, Inc., 2000) and included realignment and geometric unwarping of EPI images using magnetic fieldmaps, correction for bulk-head motion, nonlinear volume-based spatial normalization (standard Montreal Neurological Institute brain template), spatial smoothing with a Gaussian filter (6mm at FWHM), and artifact detection (http://web.mit.edu.ezp-prod1.hul.harvard.edu/swg/software.htm) to identify outliers in the global mean image time series (threshold: 3.5) and movement (threshold: 0.7; measured as scan-to-scan movement, separately for translation and rotation) parameters. rMDD women had slightly more outliers (M=12.2, SD=13.9) than HC women (M=4.8, SD=4.0), however, this difference was not statistically significant (p>0.05). Outliers were entered as nuisance regressors in the first-level, single-subject GLM analysis. Specific comparisons of interest (negative versus neutral) from single-subject analyses were then tested using linear contrasts, and SPM T-maps created based on these contrasts.

Results from the single-subject level were submitted to second-level random effects analyses of the between group (rMDD vs. HC) contrast. Given hypotheses about specific brain regions, we used the small volume correction approach in SPM8 which limits voxel-wise analyses to voxels within a priori regions of interest (ROIs). Anatomic borders of ROIs (hypothalamus, amygdala, hippocampus, OFC, mPFC, ACC, sgACC) were defined using a manually segmented MNI-152 brain and implemented as overlays on the SPM8 canonical brain using the Wake Forest University PickAtlas ROI toolbox for SPM (Maldjian et al., 2003). False positives were controlled using family-wise error (FWE) correction. Within an anatomic ROI, significant results identified using small volume correction (initial voxel-wise height threshold: p<0.05 uncorrected) are reported as significant if they additionally met the peak-level threshold of p<0.05, FWE-corrected.

Anatomic overlays were used on each subject’s statistical maps to acquire signal change values across ROIs. Values indicated the degree of change in signal detected between negative and neutral stimuli. Average percent signal change (psc) values were obtained using the REX toolbox (Whitfield-Gabrieli, 2009) and used to calculate effect sizes for group differences (Cohen’s d = 2t/√df) and in brain-hormone GLM analyses. The psc values were defined based on activation clusters from the rMDD vs. HC group contrast and drawn from spheres around the maximum voxel within each cluster.

Behavioral data were analyzed using SPSS (version 19; SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL) using independent t-tests (demographic and clinical characteristics; stimuli ratings) or repeated-measures ANOVAs (mood and anxiety ratings). Correlations between behavioral, hormone, and brain data were calculated using Pearson correlation coefficients. A p<0.05 was designated for statistical significance.

3. RESULTS

Women with rMDD reported higher STAI trait anxiety scores than HC women; however, mean levels in the rMDD group were below the clinical range (see Table 2), consistent with their remission status. Analysis of the pre- and post-scan anxiety ratings (STAI state) revealed a significant effect of session with increases in anxiety post-scan compared to pre-scan (F=9.87, df=1, p<0.05) and case status (F=6.37, p<0.05), but no session by case interaction (F=1.67, n.s.). However, post-scan, rMDD women rated subjective anxiety higher than HC women (t=2.34, p<0.05; see Table 2). These results imply that rMDD women demonstrated overall significantly higher state anxiety than HC women, and that both groups demonstrated increases in anxiety following the mild stress paradigm (see Table 2). Closer examination of mean ratings indicated that the average state anxiety rating increased 7 points in rMDD women compared to 3 points in HC women. Thus, the lack of session by case interaction was likely driven by significant variability in the rMDD women in post-scan ratings. Analysis of the pre- and post-mood ratings (POMS) subscales revealed no significant session by case interactions. Subjective stimuli ratings did not differ between groups. Collectively, these findings suggest a somewhat more marked response to the mild stress challenge in rMDD women, with significantly higher anxiety after the challenge, consistent with a lower threshold for stress reactivity despite equivalent stimuli ratings as HC women.

Table 2.

Mood and Anxiety Ratings in Depressed and Healthy Women

| Rating Scale | Healthy Controls (HC) |

Remitted MDD Women (rMDD) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | ||

| HAM-D (17-item) total score | -- | -- | 3.07 | 3.6 | |

| STAIa | |||||

| Trait anxiety scoreb | 28.9 | 4.7 | 38.7 | 10.3 | |

| State anxiety score | Pre-scan | 27.5 | 6.6 | 31.1 | 8.4 |

| Post-scanc | 29.5 | 6.4 | 38.1 | 12.4 | |

| POMSd | |||||

| Tension-Anxiety | Pre-scan | 30.1 | 0.5 | 31.1 | 2.2 |

| Post-scan | 30.7 | 2.2 | 30.9 | 11.3 | |

| Depression-Dejection | Pre-scan | 33.4 | 2.7 | 34.6 | 3.8 |

| Post-scan | 33.4 | 2.6 | 37.1 | 7.4 | |

| Anger-Hostility | Pre-scan | 37.5 | 1.1 | 38.2 | 1.9 |

| Post-scan | 37.5 | 1.1 | 39.7 | 7.6 | |

| Vigor-Activity | Pre-scan | 59.4 | 9.0 | 58.0 | 8.0 |

| Post-scan | 58.1 | 10.6 | 51.6 | 10.8 | |

| Fatigue-Inertiae | Pre-scan | 36.2 | 2.4 | 37.6 | 3.6 |

| Post-scan | 38.6 | 4.2 | 42.7 | 6.9 | |

| Confusion-Bewilderment | Pre-scan | 30.2 | 0.8 | 31.5 | 2.1 |

| Post-scan | 30.1 | 0.5 | 33.0 | 5.0 | |

| IAPS Stimuli Ratingsf | |||||

| Negative arousal | 4.2 | 1.9 | 4.2 | 1.9 | |

| Negative valence | 7.5 | 1.3 | 7.7 | 1.1 | |

Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI) is a self-report of current and “usual” levels of anxiety.

rMDD > HC, p<0.05.

rMDD > HC, p<0.05

Profile of Mood States (POMS) is a self-report of current mood states.

Significant increase in mood rating in rMDD women post-scan, vs. HC women, p<0.05.

After the fMRI scanning session, subjects rated a selection of the International Affective Picture System (IAPS) stimuli on valence and arousal.

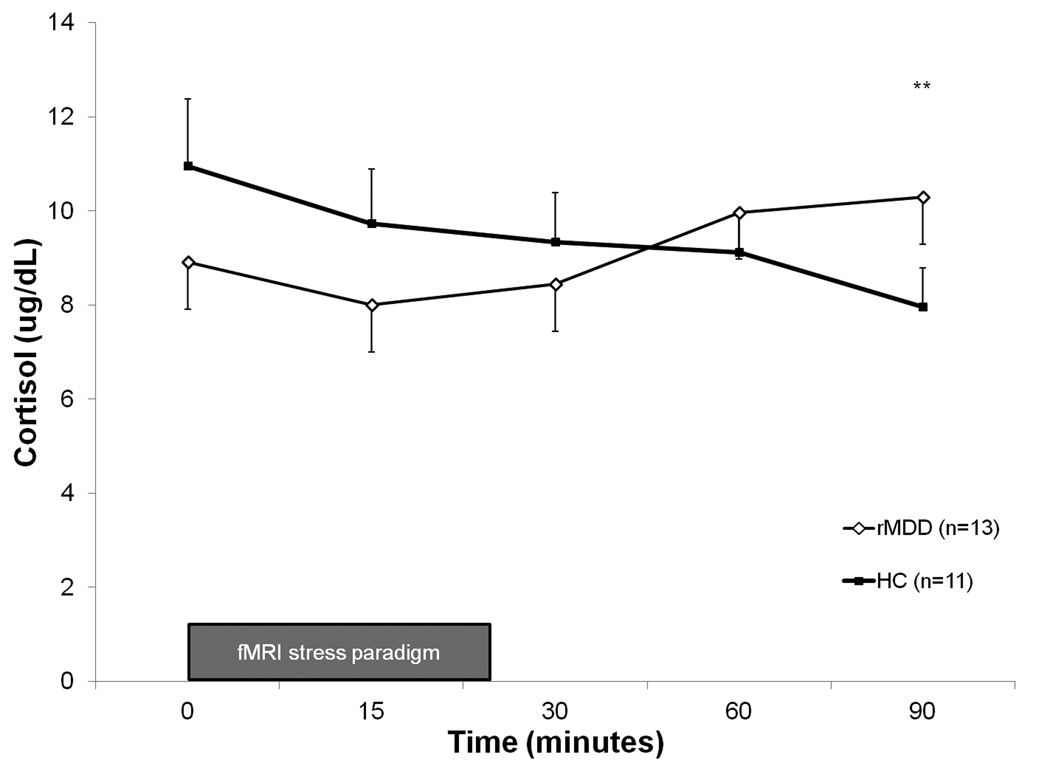

ACTH and cortisol levels were not significantly different between groups pre-scan (at Time 0; t values 0.9–1.3, n.s.). However, compared to HC women, rMDD women exhibited increased cortisol and ACTH levels over time, with significantly higher levels of ACTH at 30 minutes (t=2.20; p<0.05) and cortisol at 90 minutes following onset of the mild stress paradigm (t=2.17; p<0.05; see Figure 1), while HC women on average did not show this response. In the classification of individual cortisol responsivity, 100% (n=13) of rMDD women were classified as responders compared to 9% of HC women. This classification was significantly different between groups (X2=20.3; p<0.001), and indicated greater HPA-axis responsivity to stress in rMDD women. For ACTH, groups were not different in their distribution of responders (66.7% of rMDD, n=8; 54.5% of HC, n=6) and non-responders (33.3% of rMDD, n=4; 45.5% of HC, n=5) (X2=0.35; n.s.).

Figure 1.

Cortisol levels in rMDD and healthy control subjects, measured in response to mild stress paradigm during and following fMRI scanning. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. **rMDD > HC, p<0.05.

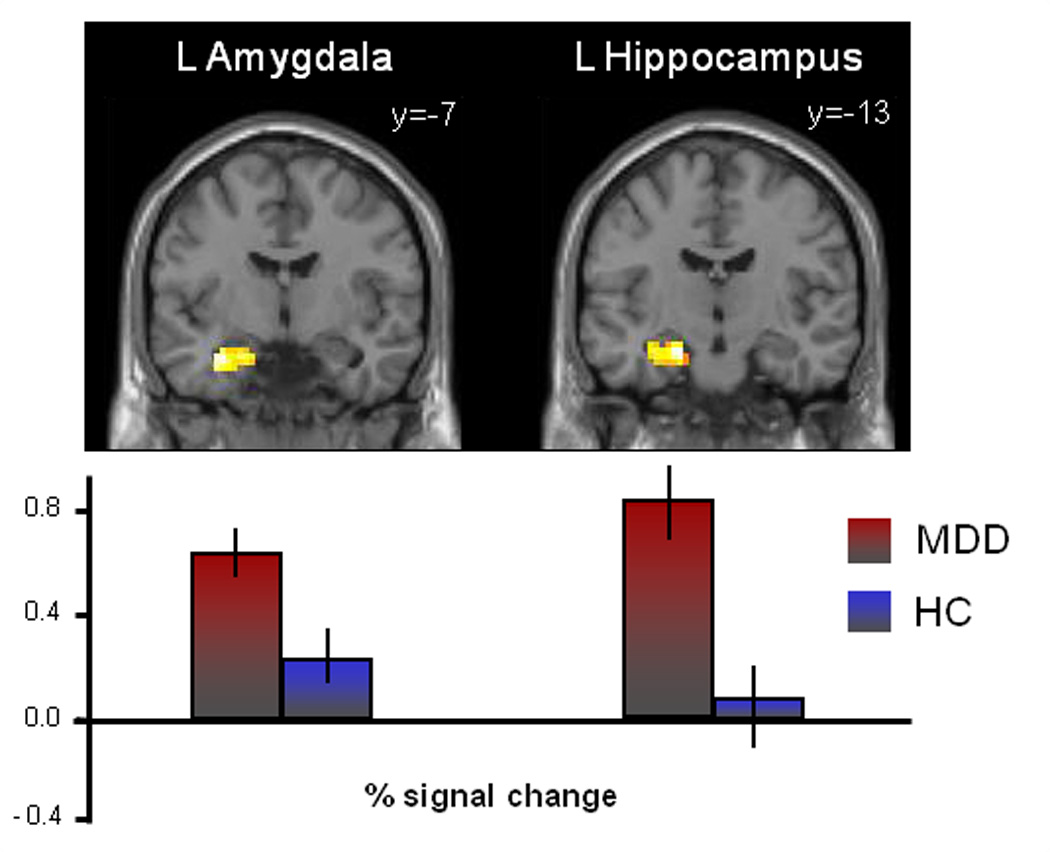

In parallel with behavioral and hormone responses to the mild stress challenge, rMDD women displayed hyperactivation to negative (vs. neutral) stimuli in the left amygdala (effect size = 1.11) and hippocampus (effect size = 1.33) at p<0.05, FWE-corrected (see Table 3). Percent signal change (psc) values extracted from anatomical regions of interest are plotted in Figure 2. At an uncorrected p<0.05 level, rMDD women showed greater activation in the right hypothalamus, amygdala, hippocampus and ACC and left sgACC at p<0.05 (effect sizes: 0.85– 1.29). There were no regions in which HC women exhibited greater activation than MDD women. We further examined the potential effects of remission and medication status (in the rMDD women) on the between-group results. Analysis of the 6 MDD women on medications compared to the 9 off medications and to controls indicated that although STAI scores were slightly (but not significantly) higher in unmedicated women, hyperactivity in stress response regions remained in both groups. Similarly, removing the data of the 1 rMDD woman in partial remission did not alter the overall group findings. Thus, hormone and brain results were not driven by the women on medications or the single participant in partial remission (data available on request).

Table 3.

Regions of Activation in Comparisons of Negative to Neutral Stimuli: Between-Group Contrasts

| Contrast | Region of Interest (ROI) | x | y | za | Z | Voxels | Uncorrected p-valueb |

Voxel-level FWE-corrected p-valuec |

Effect sized | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| rMDD > HC | ||||||||||

| Hypothalamus | R | 9 | −7 | −14 | 2.34 | 13 | 0.010 | 0.095 | 0.86 | |

| Amygdala | R | 18 | −1 | −29 | 2.43 | 24 | 0.008 | 0.119 | 0.90 | |

| Amygdala | L | −30 | −7 | −23 | 2.84 | 36 | 0.002 | 0.048 | 1.11 | |

| Hippocampus | R | 36 | −19 | −14 | 2.99 | 84 | 0.001 | 0.072 | 1.29 | |

| Hippocampus | L | −18 | −13 | −20 | 3.44 | 101 | 0.000 | 0.023 | 1.33 | |

| Anterior Cingulate Cortex | R | 6 | 8 | 28 | 3.34 | 162 | 0.000 | 0.089 | 1.27 | |

| Subgenual ACC | L | −3 | 17 | −11 | 2.38 | 9 | 0.009 | 0.145 | 0.85 | |

| HC > rMDD | ||||||||||

| none | ||||||||||

Coordinates are presented in MNI space.

Within an anatomic ROI, results identified using small volume correction with voxel-wise peak-level height threshold: p<0.05, uncorrected for multiple comparisons.

False positives controlled using family-wise error (FWE) correction. Results are reported (in bold) as significant if they additionally met the peak-level threshold of p<0.05, FWE-corrected.

Effect sizes based on average percent signal change values (beta weights averaged across 4mm radius spheres for amygdala and hypothalamus and 6mm radius spheres for other regions, drawn around the maximum voxel of difference within an anatomical ROI) were obtained using the REX toolbox for SPM8.

Figure 2.

Significant hyperactivation of stress response circuitry regions in rMDD women in comparison to healthy control subjects. Activations of hypothesized regions of interest were derived using restriction to within anatomical borders (defined by a manually segmented MNI brain) with the small volume correction tool in SPM8. Activations in Figure 2 are selected from Table 3, centered on the peak voxel of activation with a p<0.05 (uncorrected). Error bars indicate standard deviations.

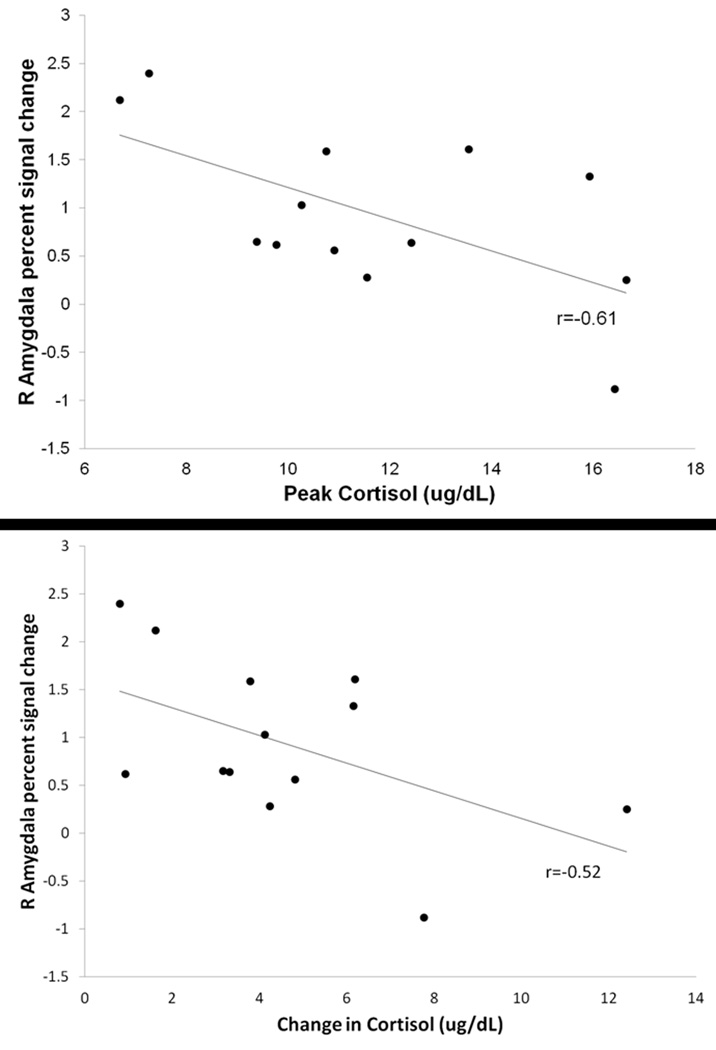

To examine the relationship between cortisol responsivity (as defined as increases in cortisol in response to the mild stress challenge) and amygdala activation during the mild stress paradigm, analyses were restricted to rMDD women, all of whom were classified as cortisol responders. Amongst rMDD women, percent signal change in the right amygdala was negatively related to peak cortisol (r=−0.61, p<0.05; see Figure 3a) and to change in cortisol at a trend level (r=−0.52, p=0.07; see Figure 3b). Cortisol response was not significantly related to hippocampal hyperactivity either measured as “peak response” or “change over time” (r values |0.14–0.42|, n.s.). Thus, rMDD women with the highest cortisol levels exhibited the lowest amygdala activity in response to stress and lack of response (little correlation) from the hippocampus.

Figure 3.

Associations between amygdala hyperactivation and cortisol reactivity in response to mild stress paradigm. (a) Correlation between right amygdala psc and peak cortisol response in rMDD women (p<0.05). (b) Correlation between right amygdala psc and change in cortisol in rMDD women (p=0.071).

4. DISCUSSION

Extant literature has provided substantial evidence of abnormal stress responsivity in the etiology of MDD, most often focusing on HPA-axis hormones and their targets in the central nervous system in individuals currently in a depressed state. Here, we present evidence that even in remission, women with recurrent MDD display dysregulation on multiple levels involved in their response to a stress challenge. In response to a mild stress challenge, rMDD women (compared to healthy controls): a) reported increased anxiety; b) exhibited increased HPA-axis responsivity; c) displayed hyperactivity in the amygdala and hippocampus, and d) demonstrated associations between brain hyperactivation and HPA-axis alterations. Findings represent an advance in our understanding of the role of HPA activity and brain activity in rMDD in women compared to healthy women.

Our sample of rMDD women exhibited HPA-axis reactivity in response to a mild stressor. Remarkably, classification of cortisol responders versus non-responders matched completely with case group status, with all rMDD subjects meeting criteria as responders and all controls as non-responders. Further, as a group, rMDD women demonstrated increases in ACTH following the stress paradigm, with significantly greater levels at T30 compared to healthy controls, which generally showed decreases over the course of blood sampling. These findings are consistent with previous reports of persistent HPA-axis dysregulation in remitted MDD (Kathol, 1985, Deshauer et al., 1999, Bhagwagar et al., 2003, Vreeburg et al., 2009, Morris et al., 2012), and collectively, provide evidence of HPA-axis hyperresponsivity as a potential trait marker of MDD. Studies have suggested that this may signal vulnerability to relapse in individuals demonstrating this phenotype (Morris et al., 2012).

In contrast, there have been reports of hyporeactivity of the HPA-axis in response to significant psychosocial stress in rMDD women (Ahrens et al., 2008). This discrepancy may be due to sample demographics (our subjects were on average 6 years younger) or procedural differences (our paradigm was designed to invoke a mild stress reaction). Alternatively, HPA-axis responses may differ depending on whether the woman is in an acute depressive episode or following recovery (Bouhuys et al., 2006, Morris et al., 2012), given that some individuals demonstrate normalization in remission while others exhibit persistent abnormalities in ACTH and cortisol responses. Our sample of rMDD women showed activation of ACTH and cortisol secretion following mild stress. Increased ACTH and cortisol suggests abnormalities at the central nervous system (CNS) level of the HPA circuit with hypersecretion of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH) by the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus (PVN).

This is supported by our brain imaging findings of hyperactivity in the arousal region, right amygdala, signaling an initiation of the stress response, and hyperactivity in the hippocampus. However, there was a lack of association between how the CNS responded to stress and how the HPA circuitry functioned. Hyperactivity of the amygdala was related to lower cortisol response and there was little relationship between hippocampus and cortisol response. Although we understand that there was insufficient temporal resolution to determine how the endogenous changes in cortisol were precisely affecting activity in our regions of interest, we suggest that increased amygdala activity to decreased cortisol responsivity reflects dysregulation in the feedback from hippocampal glucocorticoid action to the central nucleus of the amygdala, which stimulates release of CRH from the hypothalamic PVN. PVN abnormalities in MDD have been identified at the postmortem level, particularly in neurons containing ER-α (Bao et al., 2005), in addition to the well-known abnormalities found in the amygdala and hippocampus. Thus, further research using functional connectivity in women with rMDD is needed to explore these brain-hormone relations.

Our findings of hyperactivation of the amygdala and hippocampus in response to negative stimuli are consistent with findings in currently depressed (Sheline et al., 2001, Fahim et al., 2004) and remitted (Ramel et al., 2007, Hooley et al., 2009) MDD subjects. Further, amygdala activation has been negatively associated with endogenous (Pruessner et al., 2008, Cunningham-Bussel et al., 2009) and exogenous (Lovallo et al., 2010) cortisol in healthy control subjects. This is not completely consistent (Drevets et al., 2002b, van Stegeren et al., 2007, Root et al., 2009), likely driven by sample selection (currently depressed versus remitted subjects) and methodological approaches (resting state PET, use of a single baseline cortisol assessment). The fact that we observed similar heightened activations in a sample of recurrent MDD women in remission suggests hyperactivation of stress response circuitry may be a potential characteristic trait of MDD in women and may speak to the cumulative effects of lifelong recurrent MDD. In contrast, in a pilot study of rMDD women, we reported hypoactivation of stress response circuitry using a similar paradigm (Holsen et al., 2011). However, in that study we targeted younger women (mean age 34), who were all premenopausal with regular menstrual cycles, in contrast to our current sample of older women with several in perimenopause (mean age 46; there was no overlap in ages among these samples). Moreover, in the current study, we were able to further elucidate how dysregulation of stress response regions in rMDD is associated with real-time HPA-axis hormone responses.

Our study design had a number of strengths, including systematic clinical phenotyping, incorporation of multiple levels of measuring the stress response, assessment of serum hormones in response to a stress challenge in real time during fMRI scanning, and inclusion of recurrent rMDD women, the majority of whom were unmedicated. In fact, our analysis of medication effects yielded null results, indicating that our rMDD versus HC findings were not driven by the small number of women on medications. We understand that that our power to detect group differences was limited by a small sample size and some technical difficulties in the scanner during multiple blood draw timepoints. In addition, the age range of our study sample (43–50) coincides with the perimenopausal transition (marked by significant fluctuations in gonadal hormones) which prevented the straightforward examination of the effect of HPG-axis hormones on HPA-axis and stress response circuitry hyperactivation in our rMDD women. Finally, we understand that the ideal timing for cortisol collection may not be early morning (given the diurnal decrease following morning wakening levels). However, because our rMDD group showed ACTH and cortisol increases after a stress paradigm at a time when endogenous cortisol is highest, we may have underestimated the extent of this activation. Moreover, given that we also collected gonadal hormones, which necessitated fasting, scanning had to be acquired during the early morning time period for subject convenience and comfort.

Some might argue against our use of a mild stress challenge rather than a severe psychosocial stressor involving components of uncontrollability and social-evaluative threat (Dickerson and Kemeny, 2004). However, previous reports indicate that currently depressed individuals report increased negative affect even in response to daily life stressors (Myin-Germeys et al., 2003), and we would argue that our mild stress challenge has better content validity and important implications for response to “everyday stress” in rMDD subjects in particular. Recent findings in remitted depression suggest that higher cortisol to a low-stress task (but not a high-stress task) predicted risk for onset of subsequent depressive symptoms (Morris et al., 2012), suggesting that mild stress not only produces a stress response in rMDD, but also has the potential to serve as a marker of vulnerability to relapse. Future studies can address some of the limitations in our study by employing larger sample sizes of pre- or post-menopausal women, and collecting hormone and brain data during the late afternoon, when cortisol levels are stable and/or implementing dexamethasone/CRH test in remitted rMDD women. Finally, although we make reference to findings in remitted MDD indicating potential “trait” characteristics, due to the fact that we did not assess brain and hormone functioning prior to MDD onset, we cannot exclude the possibility that these abnormalities may reflect illness “scarring” as a consequence of experiencing multiple depressive episodes.

In conclusion, our findings provide evidence for the importance of understanding the impact of HPA-axis hormone abnormalities on hyperactivity in the brain in response to stress in women with recurrent MDD in remission. Altered neuroendocrine dynamics identified in these women and their impact on brain activity abnormalities are important clues for the potential development of sex-dependent hormonal treatments. Further, we provided support for the necessity of measuring peripheral HPA-axis hormones in parallel with neuroimaging data. Our results represent an important step in understanding potential traits characterized by behavioral, neuroendocrine, and brain dysfunction in women with MDD, which contribute to understanding sex differences in MDD.

Highlights.

We studied women with and without recurrent major depression, in remission.

rMDD women showed higher amygdala and hippocampus activity in response to stress.

In rMDD women, amygdala activity was negatively related to change in cortisol.

Amygdala activity was positively associated with duration of illness in rMDD women.

ACKNOLWEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health Office for Research on Women’s Health and Mental Health (ORWH-NIMH) P50 MH082679 (Goldstein, P.I.). L.M.H. was also funded by NIMH K01 MH091222. The research was conducted with support from Harvard Catalyst | The Harvard Clinical and Translational Science Center (NIH #UL1 RR025758). We thank Jenn Walch, M.Ed. and Anne Remington for help with project management, Harlyn Aizley, M.Ed. for clinical interviewing, and Jo-Ann Donatelli, Ph.D. for her contributions to diagnostic review with Dr. Goldstein. The authors also thank Stuart Tobet, Ph.D. and Robert Handa, Ph.D. for their collaborative work with the Goldstein Lab (on P50 MH082679) regarding the impact of hormones on stress response circuitry and mood and anxiety.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Abercrombie HC, Jahn AL, Davidson RJ, Kern S, Kirschbaum C, Halverson J. Cortisol's effects on hippocampal activation in depressed patients are related to alterations in memory formation. J Psychiatr Res. 2011;45:15–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens T, Deuschle M, Krumm B, van der Pompe G, den Boer JA, Lederbogen F. Pituitary-adrenal and sympathetic nervous system responses to stress in women remitted from recurrent major depression. Psychosom Med. 2008;70:461–467. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31816b1aaa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao AM, Hestiantoro A, Van Someren EJ, Swaab DF, Zhou JN. Colocalization of corticotropin-releasing hormone and oestrogen receptor-alpha in the paraventricular nucleus of the hypothalamus in mood disorders. Brain. 2005;128:1301–1313. doi: 10.1093/brain/awh448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhagwagar Z, Hafizi S, Cowen PJ. Increase in concentration of waking salivary cortisol in recovered patients with depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2003;160:1890–1891. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.10.1890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bouhuys AL, Bos EH, Geerts E, van Os TW, Ormel J. The association between levels of cortisol secretion and fear perception in patients with remitted depression predicts recurrence. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2006;194:478–484. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd.0000228502.52864.ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burke HM, Davis MC, Otte C, Mohr DC. Depression and cortisol responses to psychological stress: a meta-analysis. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2005;30:846–856. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll BJ, Curtis GC, Davies BM, Mendels J, Sugerman AA. Urinary free cortisol excretion in depression. Psychol Med. 1976a;6:43–50. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700007480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll BJ, Curtis GC, Mendels J. Cerebrospinal fluid and plasma free cortisol concentrations in depression. Psychol Med. 1976b;6:235–244. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700013775. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham-Bussel AC, Root JC, Butler T, Tuescher O, Pan H, Epstein J, Weisholtz DS, Pavony M, Silverman ME, Goldstein MS, Altemus M, Cloitre M, Ledoux J, McEwen B, Stern E, Silbersweig D. Diurnal cortisol amplitude and fronto-limbic activity in response to stressful stimuli. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2009;34:694–704. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2008.11.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delvecchio G, Fossati P, Boyer P, Brambilla P, Falkai P, Gruber O, Hietala J, Lawrie SM, Martinot JL, McIntosh AM, Meisenzahl E, Frangou S. Common and distinct neural correlates of emotional processing in Bipolar Disorder and Major Depressive Disorder: a voxel-based meta-analysis of functional magnetic resonance imaging studies. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2012;22:100–113. doi: 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deshauer D, Grof E, Alda M, Grof P. Patterns of DST positivity in remitted affective disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 1999;45:1023–1029. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(98)00334-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deuschle M, Schweiger U, Weber B, Gotthardt U, Korner A, Schmider J, Standhardt H, Lammers CH, Heuser I. Diurnal activity and pulsatility of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal system in male depressed patients and healthy controls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1997;82:234–238. doi: 10.1210/jcem.82.1.3689. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dichter GS, Kozink RV, McClernon FJ, Smoski MJ. Remitted major depression is characterized by reward network hyperactivation during reward anticipation and hypoactivation during reward outcomes. J Affect Disord. 2012;136:1126–1134. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.09.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dickerson SS, Kemeny ME. Acute stressors and cortisol responses: a theoretical integration and synthesis of laboratory research. Psychol Bull. 2004;130:355–391. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.130.3.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty D, Rauch SL. Neuroimaging and neurobiological models of depression. Harv Rev Psychiatry. 1997;5:138–159. doi: 10.3109/10673229709000299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drevets WC. Prefrontal cortical-amygdalar metabolism in major depression. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;877:614–637. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09292.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drevets WC, Bogers W, Raichle ME. Functional anatomical correlates of antidepressant drug treatment assessed using PET measures of regional glucose metabolism. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2002a;12:527–544. doi: 10.1016/s0924-977x(02)00102-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drevets WC, Price JL, Bardgett ME, Reich T, Todd RD, Raichle ME. Glucose metabolism in the amygdala in depression: relationship to diagnostic subtype and plasma cortisol levels. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2002b;71:431–447. doi: 10.1016/s0091-3057(01)00687-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fahim C, Stip E, Mancini-Marie A, Mensour B, Leroux JM, Beaudoin G, Bourgouin P, Beauregard M. Abnormal prefrontal and anterior cingulate activation in major depressive disorder during episodic memory encoding of sad stimuli. Brain Cogn. 2004;54:161–163. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuchs SA, Edinger HM, Siegel A. The organization of the hypothalamic pathways mediating affective defense behavior in the cat. Brain Res. 1985;330:77–92. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(85)90009-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JM, Buka SL, Seidman LJ, Tsuang MT. Specificity of familial transmission of schizophrenia psychosis spectrum and affective psychoses in the New England family study's high-risk design. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2010a;67:458–467. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JM, Jerram M, Abbs B, Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Makris N. Sex differences in stress response circuitry activation dependent on female hormonal cycle. J Neurosci. 2010b;30:431–438. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3021-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldstein JM, Jerram M, Poldrack R, Ahern T, Kennedy DN, Seidman LJ, Makris N. Hormonal cycle modulates arousal circuitry in women using functional magnetic resonance imaging. J Neurosci. 2005;25:9309–9316. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2239-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton JP, Etkin A, Furman DJ, Lemus MG, Johnson RF, Gotlib IH. Functional neuroimaging of major depressive disorder: a meta-analysis and new integration of base line activation and neural response data. Am J Psychiatry. 2012;169:693–703. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.11071105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harlow BL, Wise LA, Otto MW, Soares CN, Cohen LS. Depression and its influence on reproductive endocrine and menstrual cycle markers associated with perimenopause: the Harvard Study of Moods and Cycles. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2003;60:29–36. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.60.1.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holsen LM, Spaeth SB, Lee JH, Ogden LA, Klibanski A, Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Goldstein JM. Stress response circuitry hypoactivation related to hormonal dysfunction in women with major depression. J Affect Disord. 2011;131:379–387. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2010.11.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooley JM, Gruber SA, Parker HA, Guillaumot J, Rogowska J, Yurgelun-Todd DA. Cortico-limbic response to personally challenging emotional stimuli after complete recovery from depression. Psychiatry Res. 2009;171:106–119. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2008.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hooley JM, Gruber SA, Scott LA, Hiller JB, Yurgelun-Todd DA. Activation in dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in response to maternal criticism and praise in recovered depressed and healthy control participants. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:809–812. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kalin NH, Weiler SJ, Shelton SE. Plasma ACTH and cortisol concentrations before and after dexamethasone. Psychiatry Res. 1982;7:87–92. doi: 10.1016/0165-1781(82)90056-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kathol RG. Persistent elevation of urinary free cortisol and loss of circannual periodicity in recovered depressive patients. A trait finding. J Affect Disord. 1985;8:137–145. doi: 10.1016/0165-0327(85)90036-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kendler KS, Gatz M, Gardner CO, Pedersen NL. A Swedish national twin study of lifetime major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:109–114. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kerestes R, Ladouceur CD, Meda S, Nathan PJ, Blumberg HP, Maloney K, Ruf B, Saricicek A, Pearlson GD, Bhagwagar Z, Phillips ML. Abnormal prefrontal activity subserving attentional control of emotion in remitted depressed patients during a working memory task with emotional distracters. Psychol Med. 2012;42:29–40. doi: 10.1017/S0033291711001097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keverne EB. Central mechanisms underlying the neural and neuroendocrine determinants of maternal behaviour. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 1988;13:127–141. doi: 10.1016/0306-4530(88)90010-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linkowski P, Mendlewicz J, Leclercq R, Brasseur M, Hubain P, Golstein J, Copinschi G, Van Cauter E. The 24-hour profile of adrenocorticotropin and cortisol in major depressive illness. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1985;61:429–438. doi: 10.1210/jcem-61-3-429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovallo WR, Robinson JL, Glahn DC, Fox PT. Acute effects of hydrocortisone on the human brain: an fMRI study. Psychoneuroendocrinology. 2010;35:15–20. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2009.09.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maldjian JA, Laurienti PJ, Kraft RA, Burdette JH. An automated method for neuroanatomic and cytoarchitectonic atlas-based interrogation of fMRI data sets. NeuroImage. 2003;19:1233–1239. doi: 10.1016/s1053-8119(03)00169-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mayberg HS. Limbic-cortical dysregulation: a proposed model of depression. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 1997;9:471–481. doi: 10.1176/jnp.9.3.471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McEwen BS, De Kloet ER, Rostene W. Adrenal steroid receptors and actions in the nervous system. Physiol Rev. 1986;66:1121–1188. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1986.66.4.1121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morris MC, Rao U, Garber J. Cortisol responses to psychosocial stress predict depression trajectories: social-evaluative threat and prior depressive episodes as moderators. J Affect Disord. 2012;143:223–230. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2012.05.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myin-Germeys I, Peeters F, Havermans R, Nicolson NA, DeVries MW, Delespaul P, Van Os J. Emotional reactivity to daily life stress in psychosis and affective disorder: an experience sampling study. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 2003;107:124–131. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0447.2003.02025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nelson WH, Orr WW, Jr, Shane SR, Stevenson JM. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity and age in major depression. J Clin Psychiatry. 1984;45:120–121. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Niswander KR, Gordon M. The Women and Their Pregnancies: The Collaborative Perinatal Study of the National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare; Government Printing Office; 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Okada G, Okamoto Y, Yamashita H, Ueda K, Takami H, Yamawaki S. Attenuated prefrontal activation during a verbal fluency task in remitted major depression. Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2009;63:423–425. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1819.2009.01952.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ottowitz WE, Dougherty DD, Sirota A, Niaura R, Rauch SL, Brown WA. Neural and endocrine correlates of sadness in women: implications for neural network regulation of HPA activity. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;16:446–455. doi: 10.1176/jnp.16.4.446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plotsky PM, Owens MJ, Nemeroff CB. Psychoneuroendocrinology of depression. Hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 1998;21:293–307. doi: 10.1016/s0193-953x(05)70006-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Posener JA, DeBattista C, Williams GH, Chmura Kraemer H, Kalehzan BM, Schatzberg AF. 24-Hour monitoring of cortisol and corticotropin secretion in psychotic and nonpsychotic major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2000;57:755–760. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.57.8.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price JL. Prefrontal cortical networks related to visceral function and mood. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1999;877:383–396. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1999.tb09278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pruessner JC, Dedovic K, Khalili-Mahani N, Engert V, Pruessner M, Buss C, Renwick R, Dagher A, Meaney MJ, Lupien S. Deactivation of the limbic system during acute psychosocial stress: evidence from positron emission tomography and functional magnetic resonance imaging studies. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:234–240. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.04.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramel W, Goldin PR, Eyler LT, Brown GG, Gotlib IH, McQuaid JR. Amygdala reactivity and mood-congruent memory in individuals at risk for depressive relapse. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:231–239. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Root JC, Tuescher O, Cunningham-Bussel A, Pan H, Epstein J, Altemus M, Cloitre M, Goldstein M, Silverman M, Furman D, Ledoux J, McEwen B, Stern E, Silbersweig D. Frontolimbic function and cortisol reactivity in response to emotional stimuli. Neuroreport. 2009;20:429–434. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e328326a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheline YI, Barch DM, Donnelly JM, Ollinger JM, Snyder AZ, Mintun MA. Increased amygdala response to masked emotional faces in depressed subjects resolves with antidepressant treatment: an fMRI study. Biol Psychiatry. 2001;50:651–658. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(01)01263-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sher L, Oquendo MA, Galfalvy HC, Cooper TB, Mann JJ. The number of previous depressive episodes is positively associated with cortisol response to fenfluramine administration. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1032:283–286. doi: 10.1196/annals.1314.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ustun TB, Ayuso-Mateos JL, Chatterji S, Mathers C, Murray CJ. Global burden of depressive disorders in the year 2000. Br J Psychiatry. 2004;184:386–392. doi: 10.1192/bjp.184.5.386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Stegeren AH, Wolf OT, Everaerd W, Scheltens P, Barkhof F, Rombouts SA. Endogenous cortisol level interacts with noradrenergic activation in the human amygdala. Neurobiol Learn Mem. 2007;87:57–66. doi: 10.1016/j.nlm.2006.05.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vreeburg SA, Hoogendijk WJ, van Pelt J, Derijk RH, Verhagen JC, van Dyck R, Smit JH, Zitman FG, Penninx BW. Major depressive disorder and hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activity: results from a large cohort study. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2009;66:617–626. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Korczykowski M, Rao H, Fan Y, Pluta J, Gur RC, McEwen BS, Detre JA. Gender difference in neural response to psychological stress. Soc Cogn Affect Neurosci. 2007;2:227–239. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsm018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Krishnan KR, Steffens DC, Potter GG, Dolcos F, McCarthy G. Depressive state-and disease-related alterations in neural responses to affective and executive challenges in geriatric depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:863–871. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07101590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield-Gabrieli S. Region of Interest Extraction (REX) Toolbox. Boston, MA: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Young AH, Gallagher P, Porter RJ. Elevation of the cortisol-dehydroepiandrosterone ratio in drug-free depressed patients. Am J Psychiatry. 2002;159:1237–1239. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.7.1237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young EA, Carlson NE, Brown MB. Twenty-four-hour ACTH and cortisol pulsatility in depressed women. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2001;25:267–276. doi: 10.1016/S0893-133X(00)00236-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young EA, Korszun A. The hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis in mood disorders. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2002;31:63–78. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8529(01)00002-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]