Abstract

Background

A kinetic model analysis was recently proposed to estimate the 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (18F-FDG) integrated activity in an arbitrary tissue that uses tracer uptake and release rate constants. The aim of the current theoretical paper was to estimate 18F-FDG integrated activity using one standardized uptake value (SUV).

Methods

A further kinetic model analysis allowed us to derive an analytical solution for integrated activity determination, involving both irreversible and reversible trapping. It only uses SUV, which is uncorrected for 18F physical decay (SUVuncorr, in g.mL−1) and is assessed about its peak value. Measurement uncertainty of the estimate was also assessed.

Results

In a tissue (volume V, in mL) that irreversibly traps 18F-FDG, the total number of disintegrations can be estimated as: ÃC = 162 * 105 * SUVuncorr * V * ID / W (ID, injected dose, in MBq; W, patient’s weight, in kg), where SUVuncorr is a mean over V and is assessed between 55 and 110 min after tracer injection. The relative uncertainty ranges between 18% and 30% (the higher the uptake, the lower the uncertainty). Comparison with the previous Zanotti-Fregonara’s model applied to foetus showed less than 16% difference. Furthermore, calculated integrated activity estimates were found in good agreement with Mejia’s results for healthy brain, lung and liver that show various degrees of tracer trapping reversibility and various fractions of free tracer in blood and interstitial volume.

Conclusion

Estimation of integrated activity in an arbitrary tissue using one SUV value is possible, with measurement uncertainty related to required assumptions. A formula allows quick estimation that does not underestimate integrated activity so that it could be helpful in circumstances such as accidental exposure, or for epidemiologic purposes such as in patients having undergone several examinations.

Keywords: 18F-FDG dosimetry, Integrated activity, Kinetic modelling, SUV

Background

18F-fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (18F-FDG PET) imaging has become indispensible for managing many diseases, either malignant or benign [1,2]. However, in all nuclear medicine procedures, it is important to assess the absorbed dose deposited from internally distributed radionuclides. This assessment requires combination of integrated activity in source regions and of the so-called S values that relate mean absorbed dose in an arbitrary region to integrated activity in source regions [3,4]. Since the level of irradiation induced by diagnostic examinations remains well below the threshold of appearance of deterministic effects, a degree of simplification can be accepted for absorbed dose determination. Tables of S values derived from anthropomorphic mathematical phantoms are given in MIRD pamphlets for various radionuclides and organs. Average integrated activity, i.e. the total number of disintegrations that occur from the time of tracer administration (zero) to (theoretically) infinity, or the mean residence time (ratio of integrated activity to injected activity), can be derived from healthy volunteer studies, or from a number of examinations in patients [5]. ‘Model-based’ dosimetric approaches are usually considered as sufficient to deduce a first order estimate of irradiation induced by the nuclear medicine procedure [6]. However, even in current clinical 18F-FDG PET imaging, getting a better estimate (i.e. more patient-specific) of the absorbed dose may be relevant, although the only available parameter for 18F-FDG uptake is semi-quantitative, i.e. the standardized uptake value (SUV) index. As an example, a first estimation has been made a posteriori by Zanotti-Fregonara et al. (Z-F) for an 18F-FDG examination accidentally performed during pregnancy [7,8]. It could also be helpful for epidemiologic purpose such as in patients having undergone numerous examinations.

A kinetic model analysis was recently proposed to calculate the integrated activity in an arbitrary tissue for 18F-FDG PET imaging, and its efficacy was demonstrated in the brain [9]. That study used 18F-FDG uptake and release rate constants for grey matter and white matter, which were calculated from literature data involving dynamic acquisitions, i.e. involving several measurements [10]. In comparison, the aim of the present theoretical work was to investigate whether an estimate of 18F-FDG integrated activity in an arbitrary tissue can be computed by only using SUV obtained from a single static acquisition. For this, an analytical solution derived from a kinetic model analysis was established, involving a population-based input function. This analytical solution allows determination of integrated activity that only uses SUV uncorrected for 18F physical decay (SUVuncorr) and assessed about its peak. A formula was derived that was compared to that of Z-F and its results for foetus, assuming irreversible trapping [7,8]. Furthermore, estimates for healthy brain, lung and liver that show various degrees of tracer trapping reversibility and various fractions of free tracer in blood and interstitial volume, were calculated from this analytical solution and literature data, and were compared to results published by Mejia et al. [11]. This work also assesses the measurement uncertainty of the integrated activity estimation that is related to required assumptions.

Methods

Kinetic model analysis

Let us define the SUV at time t, normalized to body weight, and corrected for18F physical decay, i.e. SUVcorr(t) (g.mL−1) [12]:

| (1) |

where ATot(t) is the whole 18F-FDG activity per tissue unit volume at time t (kBq.mL−1), which is corrected for18F physical decay (and includes trapped tracer and free tracer), W is the patient’s weight (kg), and ID is the injected dose (MBq).

First, the dosimetry purpose of this work requires calculation of the area under the curve (AUC) of the tissue activity changes with time, i.e. the AUC of the so-called tissue time activity curve (TAC). For this, the results of a previous study are summarized below [9]. A two-compartment model analysis was previously developed to assess radiotracer uptake in tissues, assuming constant uptake and release rates, K (min−1) and kR (min-1), respectively (in comparison with the three-compartment model of Sokoloff et al. [13], K is (k1k3) / (k2 + k3) and kR is (k2k4) / (k2 + k3)). The rate of trapped radiotracer change per tissue unit volume at steady state, i.e. dCTrap / dt (mL−1 min−1), is described by the following differential equation:

| (2) |

where Cp(t) is the number of tracer molecules per plasma unit volume at time t (mL−1), and λ is the 18F physical decay constant (min−1). Equation 2 yields the TAC of trapped 18F-FDG per tissue unit volume at time t, i.e. ATrap(t):

| (3) |

where Ci and αi are the coefficients of the 18F-FDG input function (IF), which is usually assumed to be a three-exponential curve [14,15]. Such a shape for the IF allows a simple analytic integration of ATrap(t) from zero to infinity, providing integrated activity for trapped 18F-FDG per tissue unit volume (mL−1). Furthermore, adding the part of free 18F-FDG in blood and reversible compartment, i.e. F (no unit), and hence extending the initial two-compartment model to a three-compartment model, provides total integrated (cumulated) activity for 18F-FDG, i.e. the total number of disintegrations ÃC (no unit) occurring in a tissue volume (V/mL) [9]:

| (4) |

where ‘Σ(λCi/αi)’ is the input function AUC of the tracer (AUCIF; in mL−1).

Second, because in the present framework the only available parameter for 18F-FDG uptake is the SUV, it is then necessary to focus on the ratio K / (λ + kR) (i.e. uptake / (decay + release)) in the right hand side of Equation 4 and to find a further relationship between the parameters. Therefore, let us consider the following equation that temporarily put aside F:

| (5) |

and let us write that at the trapped tracer peak, i.e. when dCTrap / dt = 0, Equation 2 yields:

| (6) |

As a result, the combination of Equations 1, 5 and 6 provides the following expression for 18F-FDG integrated activity in a tissue:

| (7) |

where SUVuncorr(t) is SUV that is not corrected for18F physical decay. It should be noted that the use of SUVuncorr(tpeak) in Equation 7, i.e. the use of ATot(tpeak) instead of ATrap(tpeak), involves the activity of both trapped and free tracer in blood and reversible compartment, the latter being related to F that was temporarily put aside in Equation 5.

Third, deriving a formula from Equation 7 requires that the second ratio appearing in the right-hand-side of Equation 7 be calculated. In this connection, this ratio can be expressed by means of a normalized input function for injected dose and initial distribution volume, i.e. [AUCNIF / λCpN(t)], as proposed by Vriens et al. from a patient population [15]. Thus,

| (8) |

Alternatively, Equation 8 can be expressed by using Equation 1 as

| (9) |

where ATot.uncorr(tpeak) is the peak radioactive concentration (kBq.mL−1), which is not corrected for18F physical decay.

Z-F model

Zanotti-Fregonara et al. assessed 18F-FDG integrated activity in embryo assuming (a) instantaneous tracer uptake, (b) irreversible trapping and (c) the maximal SUV (hottest pixel; corrected for18F physical decay) recorded 60 min after the injection, could be taken as an initial activity concentration that exponentially decays with time [7,8]. In other words, the total number of disintegrations ÃZ (no unit) occurring in embryo volume V (mL), was obtained from the area under the curve (AUC) of the function ‘ATot(t = 60) * exp(−λt)’, which is

| (10) |

Assuming irreversible trapping in our model, comparison with Z-F model, i.e. comparison of Equations 8 and 10, is equivalent to comparing two ratios, i.e. [AUCNIF / λCpN(tpeak)] versus [exp(60λ) / λ], respectively.

Note that the two models lead to a very close final equation when it is assumed that (a) tracer is trapped irreversibly and (b) tracer plasma decay is tracer physical decay, as shown in the Appendix.

Results

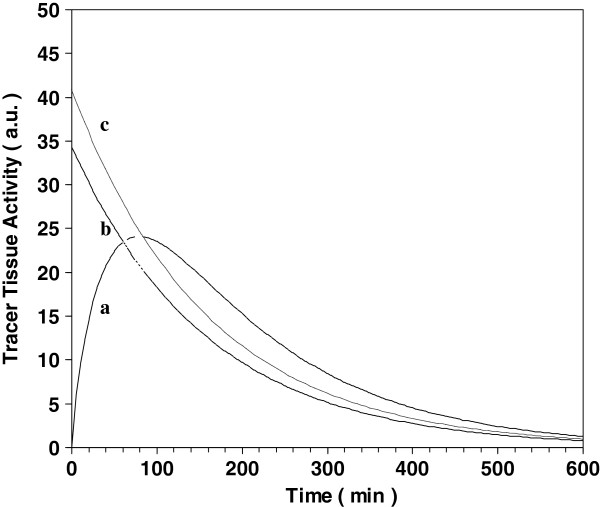

Curve a in Figure 1 was obtained from Equation 3 for irreversible trapping, showing that tissue activity peaks at t = 79 min (leading to a [AUCNIF / λCpN(tpeak)] ratio of 269 min), by using median values for the time constants of the normalized 18F-FDG input function of Vriens et al. [15] [in comparison with Vriens et al. results (Table two-first column) the decay constants were modified in our model to take 18F physical decay into account]. Using minimal and maximal inter quartile values for these time constants leads to a [AUCNIF/λCpN(tpeak)] ratio of 272 and 262 min, for tissue activity peak at 82 and 76 min, respectively. In other words, the relative difference between the ratio obtained and minimal and maximal inter-quartile values is 3.8%. An estimate of integrated activity occurring in a tissue volume (V, in mL) can be computed from either Equation 8 or 9, and using AUCNIF / λCpN(tpeak) = 269 min, as

Figure 1.

Model comparison. Curve (a) Trapped tracer activity (in arbitrary unit) versus time (in minutes) from Equation 3, assuming irreversible trapping, and the input function of Vriens et al. for 18F-FDG was used [15]. Curve (b) (full line) Z-F function, i.e. ATot(t = 60) * exp(−λt) (the value for ATot(t=60) was taken from curve a). Curve (c) (dotted line) Z-F function with ATot(t = 84) (instead of ATot(t = 60)) that gives similar AUC for the two models.

| (11) |

| (12) |

Curve a in Figure 1 also shows that when SUVuncorr in Equation 11 (or peak radioactive concentration ATot.uncorr in Equation 12) is assessed at t = 55 min or t = 110 min after injection, it is 5% lower than that obtained at peak time t = 79 min.

Furthermore, Figure 1 compares the plots of the 18F-FDG TAC from Equation 3 (curve a) and of the function ATot(t = 60) * exp(−λt) from Z-F model (curve b). Curve b was plotted using the value of ATot(t = 60) obtained in curve a. The area under each curve is the integrated activity assessed from each model, respectively. Figure 1 visually suggests that the two AUCs are very close. This visual interpretation is confirmed by the comparison between the ratios [AUCNIF / λCpN(tpeak)] and [exp(60λ) / λ], which only differ by 16%: 269 min versus 232 min, respectively. In this connection, the total number of disintegrations occurring in the foetus obtained from the present study and from the Z-F model [8] (SUVcorr(t = 60) = 4.5 g.mL-1, V = 21 mL, and 71-kg mother) is estimated to 14,720,000 and 12,623,000/MBq injected to the mother, respectively. Comparison between the [AUCNIF / λCpN(tpeak)] and [exp(60λ) / λ] ratios further indicates that the two AUCs in Figure 1 would be equal if the SUV was acquired at t = 84 min after injection (curve c) (alternatively, the two AUCs can also be equal when a low 18F-FDG release occurs in the tissue of interest, resulting in a lower AUC of the tissue TAC and in a shift of peak time to t = 77 min, instead of t = 79 min).

For healthy grey and white matter, which reversibly trap 18F-FDG, the [AUCNIF / λCpN(t)] ratio is 185 and 189 min, for peak activity at t = 61 and 63 min [9,10], respectively. For the healthy brain, integrated activity was calculated from Equation 8, assuming that brain was 50% gray and 50% white matter, with 805-mL volume each (as 2.3% of a 70-kg patient, with a brain density of 1) [10,16]. For SUVuncorr(tpeak = 60) = 4 g.mL−1 (= (5.3 + 2.7) / 2, on average [17]) and ID = 37 MBq, the total integrated activity for healthy brain compares with that calculated by Mejia et al.: 7.97 versus 6.57 (±1.51) MBq.h [11].

For the healthy lung, which irreversibly traps 18F-FDG, integrated activity was calculated from Equation 12 and experimental literature data [18]. Assuming that lung volume is 1,120 mL (as 1.6% of a 70-kg patient, with lung parenchyma density of 1) [16], for ATot.uncorr(tpeak) = 1.62 kBq.mL−1 on average (Table one in [18]), the total integrated activity for healthy lung compares with that calculated by Mejia: 0.93 versus 0.86 (±0.10) MBq.h for an administered activity (ID) of 37 MBq [11].

For the healthy liver, which reversibly traps 18F-FDG, the [AUCNIF / λCpN(t)] ratio is 164 min, for peak activity at about t = 55 min (Figure two in [19]). Total peak activity is 8.6 kBq/mL, and hence SUVuncorr(tpeak) = 1.7 g.mL-1, a value identical to that obtained by Minamimoto et al. [17]. The total integrated activity was calculated from Equation 12, assuming that liver volume is 1,280 mL (as 2.0% of a 64-kg patient, with liver parenchyma density of 1) [16]. The total integrated activity for healthy liver compares with that calculated by Mejia: 3.47 versus 4.14 (±1.09) MBq.h, for an administered activity (ID) of 37 MBq [11].

Discussion

Analytical solution of integrated activity

This theoretical work showed that the calculation of an estimate of integrated activity in an arbitrary tissue using one SUV value, or using one radioactive concentration value (Equation 8 and 9, respectively), is possible. However, this estimation requires the following: (a) the use of a population-based input function [15], which is involved in the [AUCNIF / λCpN(tpeak)] ratio (Equations 8 and 9) and (b) the use of SUV, which is uncorrected for 18F physical decay (either to the time of injection or to the beginning of acquisition) and is assessed about its peak value. The value of 18F-FDG release rate constant in the tissue of interest plays a role in the peak timing and hence in the value of CpN(tpeak) (indeed, Equation 3 shows that the peak timing depends on the release rate constant, on the physical decay constant, and on the time constants of the 18F-FDG IF, whereas the uptake rate constant plays a role in the SUVuncorr(tpeak) amplitude). If the 18F-FDG release rate constant from the tissue is unknown, and hence if the SUVuncorr peak time is unknown, assuming that kR is negligible (i.e. an irreversible trapping) leads to an overestimate. In current clinical practice, this overestimate is more acceptable than an underestimate and can be very quickly computed as ÃC = 162 * 105 * SUVuncorr(tpeak) * V * ID/W (Equation 11).

The use of the semi-quantitative SUV index obtained from a single acquisition for integrated activity estimation requires assumptions presented above, resulting in different origins of measurement uncertainty. The measurement uncertainty that is related to the product ‘162 * 105’, i.e. related to the [AUCNIF / λCpN(tpeak)] ratio, was estimated to be ±3.8%, i.e. the relative difference between the [AUCNIF / λCpN(tpeak)] ratio obtained by using minimal and maximal inter quartile values for the time constants of the normalized 18F-FDG IF of Vriens et al. [15]. Although this relative uncertainty is low, it is suggested that it could be still reduced by using, in each patient, a more specific IF adjusted with a single blood sample, instead of a population-based input function, as proposed by authors [14,20]: in other words, Equation 7 could be used instead of Equation 8. Note that such a method could be applied in particular in hyperglycaemic patients, while SUVuncorr(tpeak) (even if it is lowered owing to a high blood glucose level) should be used as such, with appropriate measurement uncertainty discussed below. First, in current clinical practice, a strict time delay between injection and acquisition cannot be always fulfilled to obtain SUVuncorr peak value. However, curve a in Figure 1 shows that trapped tracer radioactive concentration, and hence SUVuncorr, smoothly peaks at t = 79 min, and at t = 55 min or t = 110 min after injection, i.e. a typical acquisition time window, its value is 5% lower than that obtained at peak time. Second, SUV in itself involves a relative measurement uncertainty, which is the same for SUV either corrected or uncorrected for physical decay. In a recent study, de Langen et al. [21] showed that SUVmax repeatability, and hence SUVmax measurement uncertainty, was significantly greater than that of SUVmean, i.e. SUV averaged over several voxels. Therefore, the use of SUVmean appears relevant for dosimetry purpose. It can be obtained over a tissue volume, exhibiting either homogeneous or heterogeneous 18F-FDG uptake, as well as over a volume of interest within heterogeneous uptake (in this connection, the brain that is built of white and grey matter may be considered as an example of heterogeneous uptake). The SUVmean measurement uncertainty can be estimated from Figure two C in De Langen et al. study showing a minimal-maximal repeatability of 13% to 30% (with 95% confidence limit), leading then to a relative measurement uncertainty of 9.2% to 21.2% (=13/21/2 to 30/21/2). However, it should be noted that the use of the SUVmax value over a tissue volume, instead of SUVmean, may provide an overestimate (that is more acceptable than an underestimate), and the SUVmax measurement uncertainty can be obtained in the study of de Langen [21].

As a summary, for estimation of integrated activity from Equation 11: SUVuncorr may be averaged over the tissue volume and should be assessed between 55 and 110 min after injection. The total uncertainty of the estimate ranges between 18% and 30% (as 18 = 3.8 + 5 + 9.2 and 30 = 3.8 + 5 + 21.2, i.e. simply summing the measurement uncertainties of different origins, respectively), depending on the tissue uptake: the higher the uptake, the lower the uncertainty.

Comparison with Z-F model

To the very best of our knowledge, the only previously published analytical solution for estimating integrated activity from one SUV value was that of Zanotti-Fregonara et al. in the framework of foetal dosimetry. This is the reason why the present model was compared to that of Z-F [7,8]. The results of the two models, assuming irreversible trapping, were found in very good agreement with only a 16% difference. It is suggested that this difference is very likely overestimated. Indeed, the model comparison indicates that the estimates would be equal if the SUV was acquired at t = 84 min after injection (comparison of the AUC of curve a to curve c in Figure 1). A 16% difference was found with SUV obtained at 60 min after tracer injection, but this time delay is that of the start of the whole imaging procedure and not that of the particular step of PET imaging that involved the tissue of interest (embryo). Zanotti-Fregonara et al. indicated that imaging was obtained from the base of the skull to the mid-thigh level (7 table positions, 3-min per position). If so, taking also into account the time duration of the CT, the actual time delay between injection and acquisition was very likely longer than 60 min, and hence closer to 84 min. As a summary, it is suggested that the agreement between the two models mainly comes from (a) the common assumption that SUV is assessed about the SUVuncorr peak and (b) that the 18F half-life somewhat dominates the decay of the trapped 18F-FDG TAC, as visually shown by Figure 1. Nevertheless, it is suggested that the main benefit of the proposed model over the Z-F model is that reversible trapping is also addressed.

Furthermore, in the framework of foetal dosimetry, it should be noted that both models can only provide a rough estimate of the integrated activity, because several unknown factors may influence the 18F-FDG uptake by the foetal tissues. In particular, foetal blood glucose level depends on that of the mother because glucose molecules can pass through the placental barrier, and therefore it is reasonable to assume a similar fate for glucose analogue molecules like 18F-FDG molecules. However, a main limitation of the integrated activity estimation from the two models is that the foetal 18F-FDG IF may be different from that of the mother. In addition, it should be noted that the foetal dosimetry should also involve the bladder as a source region, because it is close to the foetus and it is filled with urinary 18F-FDG [22].

Comparison with Mejia’s results

Calculated integrated activity estimates were found in good agreement with Mejia’s results for healthy brain, lung and liver that show various degrees of tracer trapping reversibility and various fractions of free tracer in blood and interstitial volume. Healthy brain reversibly traps 18F-FDG and F is much lower than the ratio K / (λ + kR): 4.6% and 5.9% for grey and white matter, respectively [9]. Healthy lung irreversibly traps 18F-FDG and F is not negligible in comparison with the ratio K / (λ + kR): 63% at peak time [18]. Healthy liver reversibly traps 18F-FDG and F is not negligible in comparison with the ratio K / (λ + kR): 26% at peak time [19]. Furthermore, it should be noted that neglecting reversibility of the 18F-FDG uptake in healthy brain and liver leads to an overestimation of integrated activity that can be approached by comparing the [AUCNIF / λCpN(tpeak)] ratio obtained at t = 62 and 55 min to that obtained at t = 79 min (=269/187 and 269/164), which differs by 44% and 64%, respectively: the greater the release rate constant, the greater the overestimation.

Furthermore, Mejia et al. assume a two-exponential decay for lung and liver TAC and a five-exponential decay for brain TAC that can be applied to experimental tissue data, respectively [11]. In comparison, the present study assumes a multi-exponential decay of the tracer IF leading to an analytical expression for integrated activity (Equation 4) that involves the sum ‘Σ(λCi/αi)’, which is the AUC of the tracer IF. This sum is close to the sum expressed in the right hand side of Equation A4 obtained by Mejia [11], thus suggesting that for integrated activity estimation, assuming a multi-exponential decay of the tissue TAC should be implicitly connected to assuming a multi-exponential decay of the tracer IF.

Conclusions

This theoretical work showed that an estimate of cumulated activity in an arbitrary tissue can be computed from an equation that involves the tissue SUV, which is used without physical decay correction and is assessed about its peak (i.e. SUVuncorr(tpeak)). Furthermore, if the 18F-FDG release rate constant from the tissue is unknown, in other words, if peak time of SUVuncorr is unknown, this work shows that assuming an irreversible trapping leads to an overestimate. This overestimate is more acceptable than an underestimate and can be very quickly computed as ÃC = 162.105 * SUVuncorr * V * ID/W (V, tissue volume, in mL; ID, injected dose, in MBq; W, patient’s weight, in kg), where SUVuncorr is a mean over V and is assessed between 55 and 110 min after injection. However, this calculation requires assumptions leading to a relative measurement uncertainty for the estimate that ranges between 18% and 30% (the higher the uptake, the lower the uncertainty). It is suggested that estimating 18F-FDG integrated activity using one SUV value could be helpful in circumstances such as accidental exposure, or for epidemiologic purposes such as in patients having undergone several examinations.

Appendix

When the present model is developed assuming that (a) tracer is trapped irreversibly, i.e. kR = 0, and that (b) tracer plasma decay equals the tracer physical decay, Equation 5 becomes:

| (13) |

where Cp(t = 0) is the number of tracer molecules per plasma unit volume (in mL−1) at the time of injection. Furthermore, when kR = 0, at the trapped tracer peak Equation 6 becomes:

| (14) |

When tracer plasma decay equals tracer physical decay, i.e. Cp(tpeak) = Cp(t = 0) * exp(−λtpeak), combining Equations 1, 13 and 14 provides a further expression for 18F-FDG integrated activity in a tissue as follows:

| (15) |

where SUVcorr(tpeak) is SUV that is corrected for18F physical decay and that is assessed at the trapped tracer peak, which is t = 160 min, as shown in a previously published work [23]. Comparison of Equations 10 and 15 shows they are very close except that SUVcorr is not assessed at the same time delay after injection, i.e. 60 and 160 min, respectively.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Authors' contributions

EL conceived the model analysis, participated in the study design and coordination, and in the manuscript writing. MB participated in the study design, in the model interpretation and in the manuscript writing. JB participated in the study design, in the model interpretation and in the manuscript writing. RM participated in the study design, in the model interpretation and in the manuscript writing. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Contributor Information

Eric Laffon, Email: elaffon@u-bordeaux2.fr.

Manuel Bardiès, Email: manuel.bardies@inserm.fr.

Jacques Barbet, Email: jacques.barbet@univ-nantes.fr.

Roger Marthan, Email: Roger.Marthan@u-bordeaux2.fr.

Acknowledgement

We would like to thank the anonymous reviewer whose criticism improved the manuscript.

References

- Som P, Atkins HL, Bandoypadhyay D, Fowler JS, MacGregor RR, Matsui K, Oster ZH, Sacker DF, Shiue CY, Turner H, Wan CN, Wolf AP, Zabinski SV. A fluorinated glucose analog, 2-fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose (F-18): nontoxic tracer for rapid tumor detection. J Nucl Med. 1980;3:670–675. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valk PE, Bailey DL, Townsend DW, Maisey MN. Positron Emission Tomography, Basic Science and Clinical Practice. London: Springer; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Loevinger R, Budinger TF, Watson EE. MIRD Primer for Absorbed Dose Calculations (revised). Ed. New York: The Society of Nuclear Medicine; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Bolch WE, Eckerman KF, Sgouros G, Thomas SR. MIRD pamphlet no. 21: a generalized schema for radiopharmaceutical dosimetry - standardization of nomenclature. J Nucl Med. 2009;3:477–484. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.056036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hays MT, Watson EE, Thomas SR, Stabin M. Radiation absorbed dose estimates from 18F-FDG. MIRD dose estimate report no. 19. J Nucl Med. 2002;3:210–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Annals of the ICRP 106. Radiation dose to patients from radiopharmaceuticals. ICRP Publication. 2008;3(1–2):85. doi: 10.1016/j.icrp.2008.08.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanotti-Fregonara P, Champion C, Trebossen R, Maroy R, Devaux J-Y, Hindié E. Estimation of the β+ dose to the embryo resulting from 18F-FDG administration during early pregnancy. J Nucl Med. 2008;3:679–682. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.107.048900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zanotti-Fregonara P, Jan S, Taieb D, Cammilleri S, Trebossen R, Hindié E, Mundler O. Absorbed 18F-FDG dose to the foetus during early pregnancy. J Nucl Med. 2010;3:803–805. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.071878. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laffon E, Bardiès M, Barbet J, Marthan R. Kinetic model analysis for absorbed dose calculation applied to brain in [18F]-FDG PET imaging. Cancer Biother Radiopharm. 2010;3:665–669. doi: 10.1089/cbr.2010.0836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps ME, Huang SC, Hoffman EJ, Selin C, Sokoloff L, Kuhl DE. Tomographic measurement of local cerebral glucose metabolic rate in humans with (F-18)2-fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose: validation of method. Ann Neurol. 1979;3:371–388. doi: 10.1002/ana.410060502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mejia AA, Nakamura T, Masatoshi I, Hatazawa J, Masaki M, Watanuki S. Estimation of absorbed doses in humans due to intravenous administration of fluorine-18-fluorodeoxyglucose in PET studies. J Nucl Med. 1991;3:699–706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boellaard R. Standards for PET image acquisition and quantitative data analysis. J Nucl Med. 2009;3:11S–20S. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.108.057182. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sokoloff L, Reivich M, Kennedy C, Des Rosiers MH, Patlak CS, Pettigrew KD, Sakurada O, Shinohara M. The [14C]deoxyglucose method for the measurement of local cerebral glucose utilization: theory, procedure, and normal values in the conscious and anesthetized albino rat. J Neurochem. 1977;3:897–916. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1977.tb10649.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter GJ, Hamberg LM, Alpert NM, Choi NC, Fischman AJ. Simplified measurement of deoxyglucose utilization rate. J Nucl Med. 1996;3:950–955. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vriens D, de Geus-Oei L-F, Oyen WJG, Visser EP. A curve-fitting approach to estimate the arterial plasma input function for the assessment of glucose metabolic rate and response to treatment. J Nucl Med. 2009;3:1933–1939. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.109.065243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diem K, Lentner C. Composition chimique du corps humain. 7. Basle: Ciba-Geigy SA; 1978. p. 528. (In Tables Scientifiques). [Google Scholar]

- Minamimoto R, Takahashi N, Inoue T. FDG-PET of patients with suspected renal failure: standardized uptake values in normal tissues. Ann Nucl Med. 2007;3:217–222. doi: 10.1007/s12149-007-0012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laffon E, de Clermont H, Vernejoux J-M, Jougon J, Marthan R. Feasibility of assessing [(18)F]FDG lung metabolism with late dynamical imaging. Mol Imaging Biol. 2011;3:378–384. doi: 10.1007/s11307-010-0345-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laffon E, Adhoute X, de Clermont H, Marthan R. Is liver SUV stable over time in 18F-FDG PET imaging? J Nucl Med Technol. 2011;3:1–6. doi: 10.2967/jnmt.111.090027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hapdey S, Buvat I, Carson JM, Carrasquillo JA, Whatley M, Bacharach SL. Searching for alternatives to full kinetic analysis in 18F-FDG PET: an extension of the simplified kinetic analysis method. J Nucl Med. 2011;3:634–641. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.079079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Langen AJ, Vincent A, Velasquez LM, van Tinteren H, Boellaard R, Shankar LK, Boers M, Smit EF, Stroobants S, Weber WA, Hoekstra OS. Repeatability of 18F-FDG uptake measurements in tumours: a meta-analysis. J Nucl Med. 2012;3:701–708. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.111.095299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takalkar AM, Khandelwal A, Lokitz S, Lilien DL, Stabin MG. 18F-FDG PET in pregnancy and fetal radiation dose estimate. J Nucl Med. 2011;3:1035–1040. doi: 10.2967/jnumed.110.085381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laffon E, Cazeau A-L, Monet A, de Clermont H, Fernandez P, Marthan R, Ducassou D. The effect of renal failure on 18FDG uptake: a theoretic assessment. J Nucl Med Technol. 2008;3:200–202. doi: 10.2967/jnmt.107.049627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]