Abstract

Geobacillus stearothermophilus is a gram-positive, thermophilic bacterium, spores of which are very heat resistant. Raman spectroscopy and differential interference contrast microscopy were used to monitor the kinetics of germination of individual spores of G. stearothermophilus at different temperatures, and major conclusions from this work were as follows. 1) The CaDPA level of individual G. stearothermophilus spores was similar to that of Bacillus spores. However, the Raman spectra of protein amide bands suggested there are differences in protein structure in spores of G. stearothermophilus and Bacillus species. 2) During nutrient germination of G. stearothermophilus spores, CaDPA was released beginning after a lag time (T lag) between addition of nutrient germinants and initiation of CaDPA release. CaDPA release was complete at T release, and ΔT release (T release – T lag) was 1–2 min. 3) Activation by heat or sodium nitrite was essential for efficient nutrient germination of G. stearothermophilus spores, primarily by decreasing T lag values. 4) Values of T lag and T release were heterogeneous among individual spores, but ΔT release values were relatively constant. 5) Temperature had major effects on nutrient germination of G. stearothermophilus spores, as at temperatures below 65°C, average T lag values increased significantly. 6) G. stearothermophilus spore germination with exogenous CaDPA or dodecylamine was fastest at 65°C, with longer Tlag values at lower temperatures. 7) Decoating of G. stearothermophilus spores slowed nutrient germination slightly and CaDPA germination significantly, but increased dodecylamine germination markedly. These results indicate that the dynamics and heterogeneity of the germination of individual G. stearothermophilus spores are generally similar to that of Bacillus species.

Introduction

Many components of the spore germination machinery are conserved between spore forming members of the Bacillales [1]. Bacillus subtilis spore germination can be initiated by a variety of chemicals, including nutrients, cationic surfactants, and enzymes, as well as by hydrostatic pressure [2]. Nutrient germinants for spore germination generally include amino acids, purine derivatives, and sugars, and are species and strain specific. These nutrient germinants interact with germination receptors (GRs) located in the inner spore membrane [2], stimulating the release of the spore core’s large (∼10% of spore dry wt) depot of pyridine-2,6-dicarboxylic acid (dipicolinic acid [DPA]) and divalent cations, predominantly Ca2+, which are likely present as a 1∶1 chelate (CaDPA) [3]. CaDPA in the core is released and replaced by water in stage I of spore germination, and CaDPA release then triggers stage II of germination, a major event which is the hydrolysis of spores’ peptidoglycan cortex by cortex lytic enzymes (CLEs) [2], [4]. Concomitant with cortex hydrolysis, the core’s full rehydration ultimately leads to resumption of enzyme activity, and initiation of metabolism and macromolecular synthesis in the core, and thus spore outgrowth [2], [5].

B. subtilis spores contain three major GRs, termed GerA, GerB and GerK, each of which contains A, B and C subunits all of which are required for GR function [2]. These GRs are encoded by three tricistronic operons, each of which appears to encode a single GR [1], [2]. The GerD protein is also essential for proper GR function, and the proteins encoded by the spoVA operon are essential for DPA uptake in sporulation and probably CaDPA release during germination as well [1], [6], [7]. Geobacillus stearothermophilus is a Gram-positive spore-forming thermophile. Genomic analysis suggests that G. stearothermophilus has clear homologs of the B. subtilis GR genes as well as gerD and spoVAB, C, D genes, and genes encoding the cortex lytic enzymes CwlJ and SleB [1], [8].

G. stearothermophilus spores are the most wet heat-resistant among spores of aerobic spore-forming bacteria, and can spoil a variety of types of foodstuffs [9]–[12]. These spores are also commonly used as a biological indicator to evaluate the effectiveness of sterilization processes, in particular wet heat. However, the germination of spores of G. stearothermophilus species is much less well studied than that of spores of Bacillus species. Limited studies have shown that G. stearothermophilus spores germinate in response to low mol wt nutrient germinants including amino acids, purine and pyrimidine nucleosides, and sugars. However, the kinetics of the germination of individual G. stearothermophilus spores and the heterogeneity among individual spores in a population has not been studied.

In this study, we investigated the nutrient and non-nutrient germination of multiple individual intact and decoated G. stearothermophilus spores at various temperatures. We also measured the CaDPA level and Raman spectra of individual G. stearothermophilus spores and compared these with those of spores of several Bacillus species, as well as effects of different activation methods on kinetics of germination of individual G. stearothermophilus spores. This work has provided new information on the dynamics of and the heterogeneity in the germination of G. stearothermophilus spores.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Species Used and Spore Preparation

Spores of G. stearothermophilus NGB101 were prepared and purified as described previously [13]. The Bacillus species used in this work were Bacillus subtilis PS533 [14] and Bacillus cereus T (originally obtained from H.O. Halvorson). Spores of these species were prepared and stored as described [15], [16]. All spores used in this work were free (>98%) of growing or sporulating cells, as determined by phase contrast microscopy.

Measurement of CaDPA Level and Raman Spectra of Individual Spores by Laser Tweezers Raman Spectroscopy

The CaDPA levels of individual spores of various species were determined by laser tweezers Raman spectroscopy at 25°C [17]. Briefly, an individual spore was captured with laser tweezers, and its Raman spectrum was acquired with an integration of 20 s and a laser power of 20 mW at 780 nm. Spectra of 30 individual spores were measured and averaged. The CaDPA level in an individual spore was determined from the peak intensity at 1,017 cm−1 in its Raman spectrum relative to the peak intensity of the same Raman band from a CaDPA solution of known concentration (50 mM) and by multiplying this concentration value by the excitation volume of 1 fl to obtain attomoles of CaDPA/spore [17]. Raman spectra of 30 individual spores of G. stearothermophilus, B. subtilis and B. cereus at 25, 65, and 95°C were also averaged for analysis of heat-induced changes in spores’ molecular components.

Activation of G. stearothermophilus Spores

Unless noted otherwise, prior to germination experiments, G. stearothermophilus spores were activated by one of three methods: 1) incubation in water at 100°C for 30 min followed by cooling in ice water for 15 min; 2) incubation in water at 30°C for 120 h; or 3) incubation in 0.2 M sodium nitrite (pH 8.0) at 30°C for 17 h. Germination of unactivated G. stearothermophilus spores was also carried out in a few experiments.

Monitoring Germination of Single Spores by Raman Spectroscopy and Differential Interference Contrast (DIC) Microscopy

The germination of an individual G. stearothermophilus spore with 0.1 mM L-valine in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) at 65°C was monitored simultaneously by Raman spectroscopy and DIC microscopy, as described [18], [19]. Briefly, a single G. stearothermophilus spore was optically captured immediately after the addition of 65°C 0.1 mM L-valine/10 mM sodium phosphate buffer. Both the Raman spectra and DIC microscopy images of the trapped spore were recorded simultaneously for a period of 45 min with intervals of 30 s per spectrum and 15 s per image frame, respectively. Note that the low concentration of L-valine used in this experiment was to slow spore germination sufficiently to allow its measurement by Raman spectroscopy.

Monitoring Germination of Multiple Individual Spores by DIC Microscopy

The germination of a number of individual spores was simultaneously monitored with DIC microscopy [18]. Prior to germination, the spores were routinely activated at 100°C for 30 min unless noted otherwise. Briefly, 1 µl of heat-activated spores (108 spores/ml in water) was spread on the surface of a glass coverslip glued to a clean and sterile sample container. The spores on the container were quickly dried in a vacuum chamber at room temperature so that they adhered to the coverslip. The spore container was then mounted on a microscope heat stage kept at the appropriate temperature. Preheated germinant / buffer solution was then added to the container, and a digital CCD camera (12 bits; 1600 by 1200 pixels) was used to record the DIC images at a rate of 1 frame per 15 s for 60–120 min. These DIC images were analyzed with a computation program in Matlab to locate each spore’s position and to calculate the summed pixel intensity. The DIC image intensity of each spore was plotted as a function of the incubation time (with a resolution of 15 s).

Unless noted otherwise, G. stearothermophilus spores were germinated at various temperatures in: (i) 1 mM L-valine in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0); (ii) 1 mM AGFK (a mixture of 1 mM each of L-asparagine, D-glucose, D-fructose, and potassium ions) in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0); (iii) 60 mM CaDPA made to pH 7.4 with Tris base; and (iv) 1 mM dodecylamine in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0). Except for dodecylamine and CaDPA germination, spores were routinely activated for 30 min at 100°C prior to germination experiments unless noted otherwise.

Chemical Decoating of G. stearothermophilus Spores and Germination of Decoated Spores

Spores of G. stearothermophilus at an optical density at 600 nm of ∼10 were decoated by treatment with 1% sodium dodecylsulfate (SDS)–0.1 M NaOH–0.1 M NaCl–0.1 M dithiothreitol for 30 min at 65°C [20]. This procedure removes much of the spore’s coat protein as well as the spore’s outer membrane [20]. The decoated spores were washed at least 10 times with 0.1 M NaCl by centrifugation to remove all traces of the decoating solution and suspended in water. The decoated spores were then germinated with various agents with or without activation treatment as described above.

Data Analysis

The DIC microscope that monitored individual spores was set such that the polarizer and analyzer were crossed, and thus the DIC bias phase was zero. After adding pre-heated germinant/buffer solution to spores on the coverslips, a digital CCD camera was used to record the DIC images. These images were analyzed with a Matlab program to locate each spore’s position and to calculate the averaged pixel intensity of an area of 20×20 pixels that covered the whole individual spore on the DIC image. The DIC image intensity of each individual spore was plotted as a function of the incubation time and the initial intensity (the first DIC image recorded after the addition of the germinant) was normalized to 1 and the intensity at the end of measurements was normalized to zero. Invariably, the latter value had been constant for ≥10 min at the end of measurements.

From the time-lapse DIC image intensity, we can determine the time of completion of the rapid fall of ∼75% in spore DIC image intensity, which is concomitant with the time of completion of spore CaDPA release (T release). CaDPA release kinetics during germinationof individual spores were described by the parameters T lag, T release and ΔT release [7], [18]. We also defined the additional germination parameters, T lys and ΔT lys where T lys is the time when spore cortex hydrolysis is completed as determined by the completion of the fall in the spore’s DIC image intensity, and ΔT lys = (T lys-T release).

Results

Raman Spectra and Average CaDPA Level of Individual G. Stearothermophilus Spores

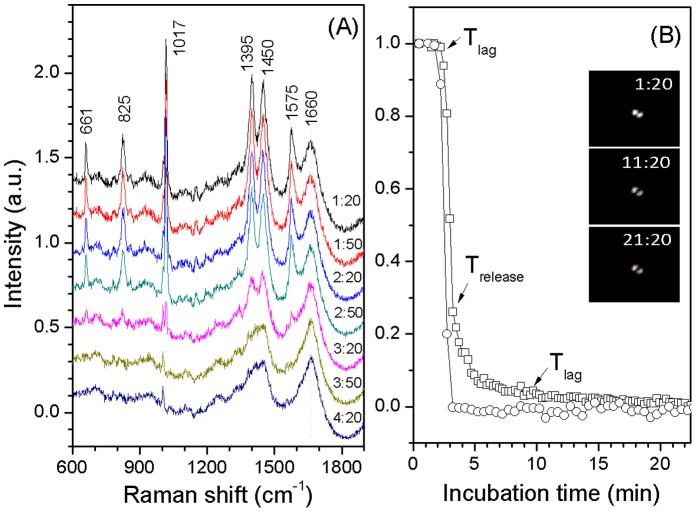

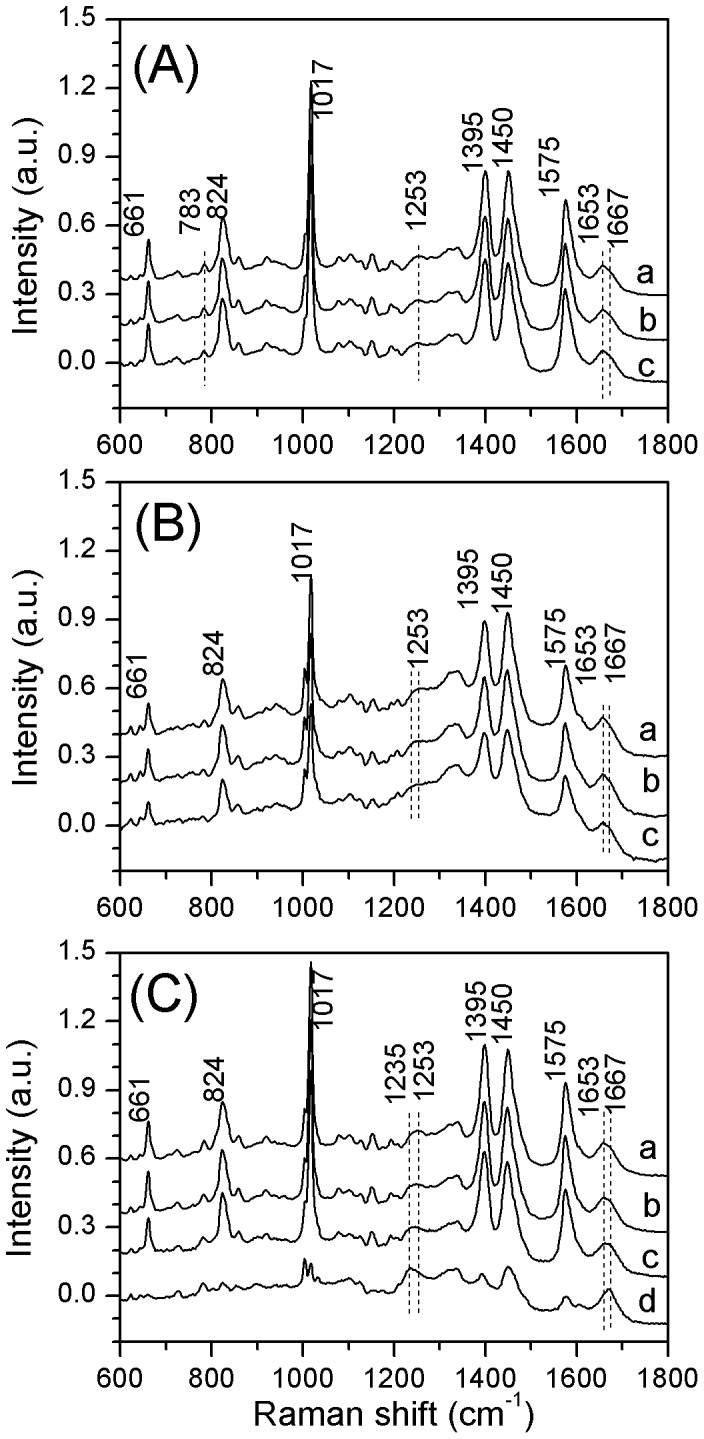

CaDPA dominates the Raman spectra of individual spores of Bacillus species [21], and this was also the case for spores of G. stearothermophilus (Fig. 1). The intensity of the CaDPA-specific 1,017 cm−1 Raman band in the average spectrum from 30 individual spores indicated that the CaDPA level in the core of G. stearothermophilus spores was ∼ 382 mM, and this value was only slightly higher than the values for B. subtilis and B. cereus spores (Table 1).

Figure 1. Raman spectra of individual spores. Raman spectra of individual G. stearothermophilus (A), B. subtilis (B), and B. cereus spores (C), measured at 25°C (curve a), 65°C (curve b) and 95°C (curve c), respectively.

Curve d in Fig. 1(C) is the Raman spectrum of single B. cereus spores that had lost their CaDPA at 95°C. All the spectra were averages from 30 individual spores determined as described in Methods. The dotted lines are the protein bands of amide I (1653/1667 cm−1) and amide III (1253 cm−1), respectively.

Table 1. CaDPA level in individual G. stearothermophilus and Bacillus spores*.

| Spores | CaDPA level (mM) |

| G. stearothermophilus | 382±79 |

| B. cereus | 350±105 |

| B. subtilis | 335±42 |

CaDPA levels in 30 individual spores of various Bacillales species were determined, and mean values and standard deviations were calculated as described in Materials and Methods.

Fig. 1 also shows the average Raman spectra of individual G. stearothermophilus spores measured at 25, 65, and 95°C, in comparison to spectra of B. subtilis and B. cereus spores. The peaks at 661, 824, 1,017, 1,395 and 1,575 cm−1 are the bands due to CaDPA, while the dotted lines denote the protein bands of amide I (1653/1667 cm−1) and amide III (1253 cm−1), respectively. The bands at 1,653 and 1,667 cm−1 are assigned to the α-helical and nonregular structures of the amide I (peptide bond C = O stretch) of proteins, respectively [22]–[24]. Raman spectra of B. subtilis and B. cereus spores (Fig. 1(B, C)) show that as the temperature was increased from 25 to 95°C, the intensity of the 1653 cm −1 band was slightly decreased and the intensity at 1667 cm−1 slightly increased. Similarly, the peak of the 1253 cm−1 band (protein amide III) was slightly shifted to the left at the higher temperatures. This suggests that the structure of proteins in B. subtilis and B. cereus spores had changed significantly from an α-helical structure to a nonregular structure at high temperature, indicative of significant denaturation of proteins in these spores as found previously [24]–[26]. Indeed, when incubated at 95°C, some B. cereus spores lost their CaDPA, the 1653c m−1 band shifted to 1667 cm−1, and the 1253 cm−1 band shifted to 1235 cm−1 (curve d in Fig. 1(C)), suggesting that significant protein denaturation took place after CaDPA release at 95°C. In contrast to results with B. subtilis and B. cereus spores, the Raman bands of protein amide I (1653/1667 cm−1) were unchanged for G. stearothermophilus spores at 95°C (Fig. 1(A)), indicating that these spores’ proteins are stable even at 95°C, consistent with these spores’ extremely high wet heat resistance. The amide III band (1230–1300 cm−1) region centered at 1253 cm−1 shifted to a lower wavenumber at 65°C and at 95°C for B. cereus spores, but for G. stearothermophilus and B. subtilis spores, this change was less prominent. The Raman band at 783 cm−1 seen at 25°C is attributed to ring breathing of cytosine/thymine/uracil and the O–P–O symmetric stretch of the phosphodiester bond in DNA and RNA [27], [28]. At 95°C, the Raman band at 783 cm−1 was nearly unchanged, suggesting that the double helical structure of nucleic acids in G. stearothermophilus spores is stable at elevated temperature.

Dynamics of Germination of Single G. stearothermophilus Spores

Fig. 2 shows dynamics of an optically trapped individual G. stearothermophilus spore during L-valine germination at 65°C, as monitored by Raman spectroscopy and DIC microscopy. After the addition of the germinant the CaDPA level as measured by the 1017 cm−1 band [17] and the DIC image intensity were nearly unchanged before T lag at ∼ 2.2 min. The intensity of the 1017 cm−1 band then quickly dropped to zero and the spore’s DIC image intensity decreased ∼70% by T release at ∼ 3.2 min. In this experiment, the DIC image intensity of the G. stearothermophilus spore usually continued to fall (but see below) until Tlys at ∼ 9.6 min, corresponding to the completion of spore cortex hydrolysis, and then remained constant. As seen with the germination of Bacillus spores [19], the termination point of the rapid fall in DIC image intensity precisely corresponded to the completion of CaDPA release for G. stearothermophilus spores.

Figure 2. Dynamics of nutrient germination of an optically trapped individual G. stearothermophilus spore.

A heat activated (30 min, 100°C) spore was germinated at 65°C with 0.1 mM L-valine in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0), and the spore was monitored by Raman spectroscopy and DIC microscopy as described in Methods. Time-lapse Raman spectra of the trapped spores after the addition of L-valine were shown in (A). The indicated peaks at 661, 825, 1,017, 1,395 and 1,575 cm−1 are the CaDPA bands. Normalized intensities of the CaDPA band at 1017−1 (○) and DIC images (□) as the function of incubation time were shown in (B). The CaDPA band intensities and DIC image intensities were normalized to their initial values right after the addition of L-valine, and the DIC image intensity at 25 min was normalized to 0. The interval between Raman spectrum acquisitions was 30 s, and the interval between DIC image acquisitions was 15 s. The inserts in Fig. 2(B) are the time-lapse DIC images of the trapped spore with a scale bar of 2 µm. The DIC image of a single spore appears as two bright spots in DIC microscopy.

Effect of Different Activation Methods on G. stearothermophilus Spore Germination

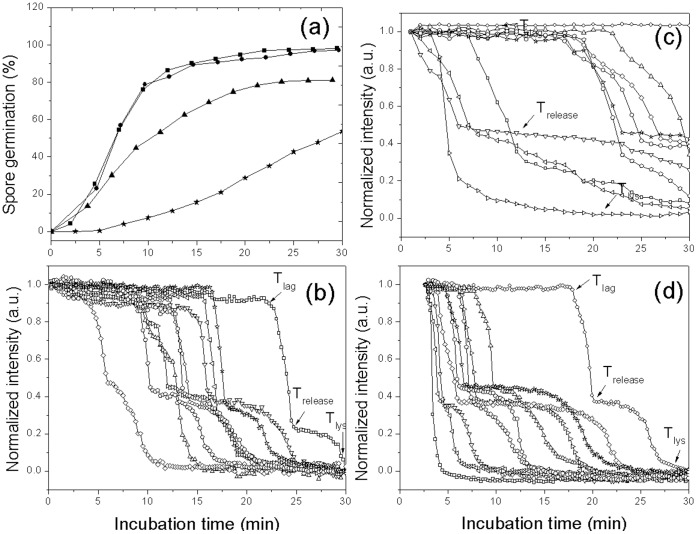

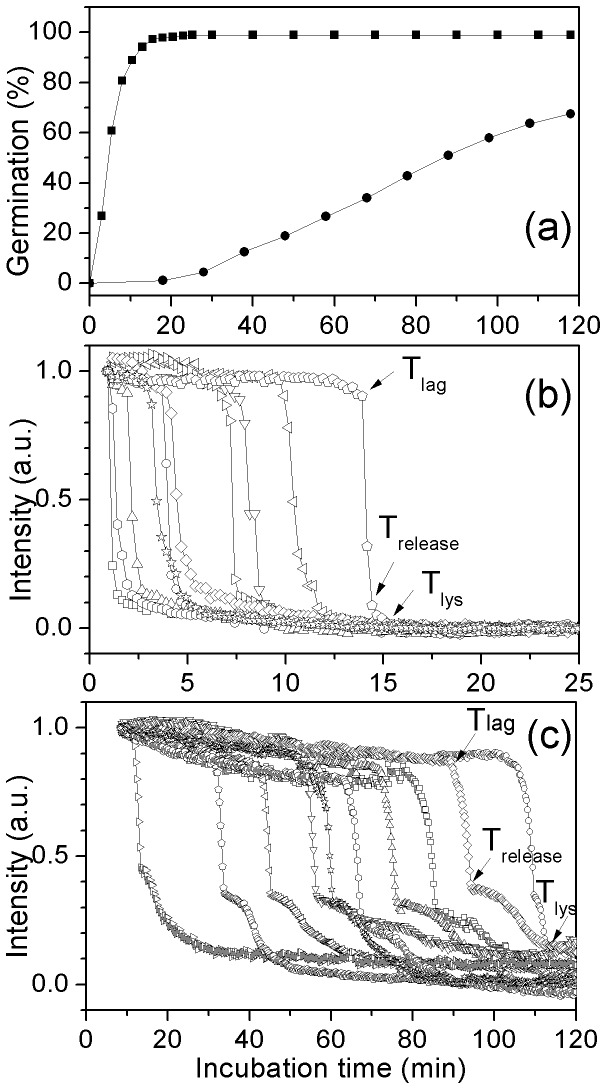

Previous studies [29], [30] have shown that germination of G. stearothermophilus spores becomes much more rapid if the spores are first given an activation treatment such as incubation in water for short times at a high temperature, long times in water at a moderate temperature, or incubation in sodium nitrite at a moderate temperature for intermediate times. The current work demonstrated that these different activation regimens led to different kinetics of L-valine germination of individual G. stearothermophilus spores at 65°C (Table 2; Fig. 3). All three activation regimens increased the overall rates of spore germination, almost completely by decreasing average T lag values with minimal if any effects on values for ΔT release and ΔT lys. Note also that for a number of the individual spores activated by various regimens, following the initial rapid fall in DIC image intensity of ∼ 60%, there was an lag of 5–20 min following T release and before the further fall in DIC image intensity. This was also seen in many other germination experiments (see below), although the reason for this lag period is not clear.

Table 2. Effect of activation methods on G. stearothermophilus spore germination*.

| Activation method | No. of spores examined(% spore germination) | T lag (min) | T release(min) | ΔT release(min) | T lys | ΔT lys(min) |

| No activation | 458 (53.7) | 12.6±6.2 | 14.1±6.2 | 1.4±0.8 | 19.5±6.2 | 5.4±2.8 |

| 100°C, 30 min | 264 (98.1) | 5.0±3.9 | 6.4±4.0 | 1.4±0.8 | 13.1±5.6 | 6.7±3.4 |

| 30°C, 0.2 M NaNO2, 17 h | 248 (97.2) | 4.4±3.2 | 5.5±3.3 | 1.1±0.6 | 11.5±5.6 | 6.0±2.9 |

| 30°C, 5 d | 523 (81.1) | 6.2±4.3 | 7.4±4.3 | 1.2±0.6 | 13.6±5.8 | 6.2±3.5 |

Activated or unactivated spores were germinated at 65°C with 1 mM L-valine in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0) for 30 min, and kinetic parameters for all germinations were determined by analysis of ≥248 spores that germinated as described in Methods.

Figure 3. Effects of different activation methods on germination of multiple individual G. stearothermophilus spores.

Spores were activated by various methods, and germinated at 65°C with 1.0 mM L-valine and 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0), and germination of individual spores was monitored by DIC microscopy as described in Methods. Germination of ≥248 individual spores (Table 2) that were activated in 0.2 M sodium nitrite (pH 8.0) at 30°C for 17 h (•), in water at 30°C for 120 h (▴), in water at 100°C for 30 min (▪), or without activation (*) was shown in (a). Kinetics of germination of ten individual spores without activation (b); activated at 30°C for 120 h (c), and activated in 0.2 M sodium nitrite (pH 8.0) for 17 h (d) was given in (b-d).

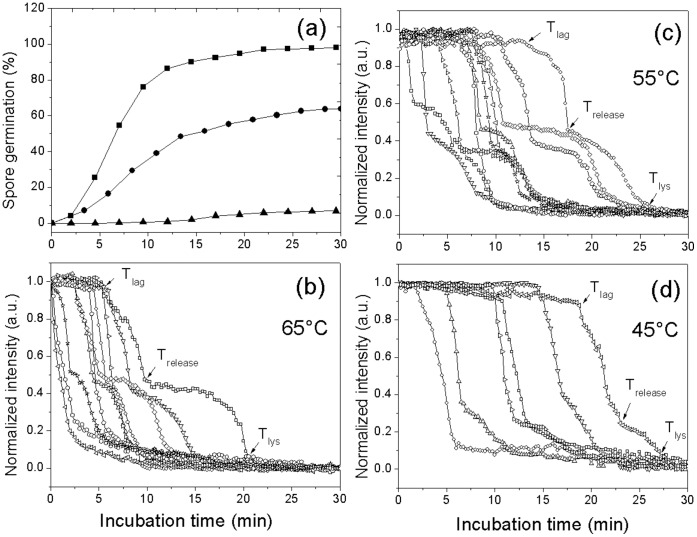

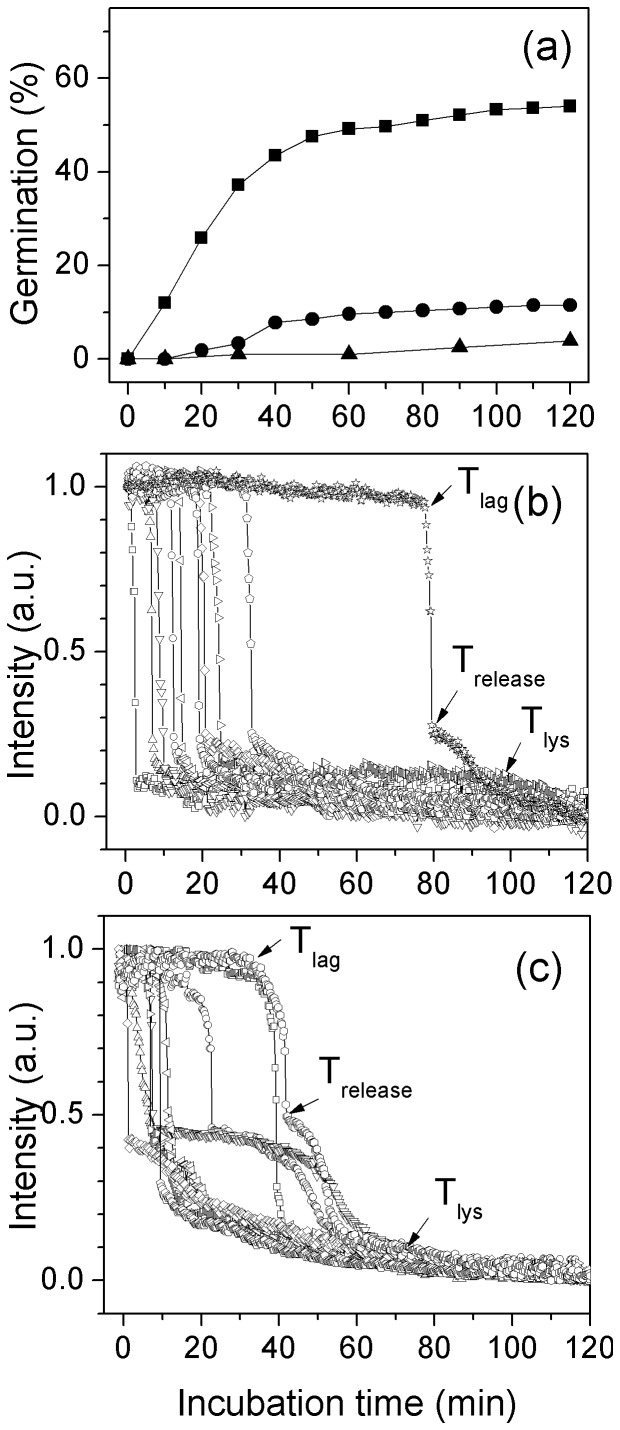

Kinetics of Germination of Multiple Individual G. stearothermophilus Spores with L-valine or AGFK

Previous work [29] has shown that G. stearothermophilus spores are able to germinate in the presence of L-valine or AGFK. Consequently we used DIC microscopy to analyze the germination of multiple individual G. stearothermophilus spores with L-valine or AGFK at multiple temperatures (Fig. 4 and 5; Table 3; and data not shown). G. stearothermophilus spores germinated faster with AGFK than L-valine at 65°C, and as expected, germination with these nutrients was faster at 65°C than at 55°C or 45°C, while no germination was observed when G. stearothermophilus spores were incubated with 1 mM L-valine at 37°C or 25°C (Table 3; and data not shown). The slower germination of these spores at lower temperatures was due primarily to longer T lag values as: i) many spores did not even germinate in the observation times at the lower temperatures, and thus have very long T lag values; ii) ΔT release values increased only slightly at lower temperatures; and iii) ΔT lys values were essentially unchanged at low and high temperatures.

Figure 4. L-Valine germination of multiple individual G. stearothermophilus spores.

Heat activated spores (30 min, 100°C) were germinated at various temperatures with 1 mM L-valine in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0), and germination of individual spores was monitored by DIC microscopy as described in Methods. Germination of ≥264 individual spores at 65°C(▪), 55°C (•), or 45°C (▴) was shown in (a). Kinetics of germination of ten individual spores at 65°C (b), 55°C (c), or 45°C (d) was given in (b–d).

Figure 5. Germination of multiple individual G. stearothermophilus spores with AGFK at different temperatures.

Heat activated (30 min, 100°C) spores were germinated at various temperatures with AGFK and 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0), and germination of individual spores was monitored by DIC microscopy as described in Methods. Germination of ≥220 individual spores at 65°C (▴), 55°C (•), or 45°C (▪) was shown in (a). Kinetics of germination of ten individual spores at 65°C (b), 55°C (c), or 45°C (d) was given in (b–d).

Table 3. Mean values and standard deviations of T lag, T release, ΔT release, T lys, and ΔT lys values for individual germinating G. stearothermophilus spores*.

| Strains and germination conditions | No. of spores examined (% spore germination) | T lag (min) | T release (min) | ΔT release (min) | T lys | ΔT lys (min) | |

| 1 mM L-valine | 65°C, 30 min | 264 (98.1) | 5.0±3.9 | 6.4±4.0 | 1.4±0.8 | 13.1±5.6 | 6.7±3.4 |

| 55°C, 30 min | 351 (63.8) | 9.5±6.6 | 11.2±6.6 | 1.7±0.8 | 16.7±6.7 | 5.4±3.1 | |

| 45°C, 30 min | 275 (6.9) | 10.6±6.7 | 12.8±6.1 | 2.2±1.0 | 16.8±6.9 | 4.0±1.8 | |

| Decoated, 65°C, 30 min | 224 (89.7) | 8.3±5.0 | 10.1±5.6 | 2.8±1.9 | 20.8±6.5 | 9.7±6.8 | |

| 1 mM AGFK | 65°C, 30 min | 302 (94.7) | 3.0±1.7 | 4.3±2.0 | 1.3±0.8 | 10.6±5.2 | 6.3±4.3 |

| 55°C, 30 min | 407 (26.5) | 6.8±4.5 | 8.5±4.6 | 1.7±0.6 | 13.8±5.1 | 5.3±2.0 | |

| 45°C, 30 min | 220 (16.4) | 7.8±8.2 | 11.3±9.0 | 3.6±2.5 | 17.4±7.6 | 6.1±10.7 | |

| Decoated, 65°C, 30 min | 396 (76.0) | 5.5±5.0 | 7.9±5.4 | 2.3±1.4 | 20.3±7.9 | 12.4±6.8 | |

| 60 mM CaDPA (no activation) | 65°C, 120 min | 380 (99.0) | 4.4±3.9 | 5.3±3.8 | 2.5±1.2 | 7.8±3.7 | 0.9±0.5 |

| 25°C, 120 min | 510 (68.8) | 56.9±26.5 | 60.4±26.8 | 3.5±1.1 | 77.2±26.4 | 23.4±9.1 | |

| Decoated, 65°C, 120 min | 310 (66.1) | 29.4±25.8 | 31.2±25.9 | 1.8±1.7 | 44.2±29.8 | 13.0±12.0 | |

| 1 mM Dodecylamine(no activation) | 65°C, 120 min | 557 (54.0) | 21.7±17.7 | 23.4±17.9 | 1.7±1.1 | 36.3±22.9 | 12.9±13.1 |

| 55°C, 120 min | 470 (11.5) | 14.9±19.8 | 16.7±20.0 | 1.9±1.3 | 39.8±23.0 | 23.0±14.5 | |

| 45°C, 120 min | 515 (3.9) | 67.8±30.1 | 68.7±30.2 | 0.9±0.8 | 78.5±32.1 | 9.9±5.4 | |

| Decoated, 65°C, 30 min | 432 (94.9) | 5.1±3.1 | 8.3±3.4 | 3.2±1.5 | – | – | |

Heat-activated G. stearothermophilus spores were germinated for 30 min with 1 mM L-valine or 1 mM AGFK at 65°C in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0), unactivated G. stearothermophilus spores were germinated at 65°C for 120 min with 60 mM CaDPA or with 1 mM dodecylamine in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0), and decoated G. stearothermophilus spores (heat-activated or unactivated) were germinated with different germinants at 65°C for 30 or 120 min. Kinetic parameters for individual germinations were determined by analysis of ≥100 spores that germinated as described in Methods.

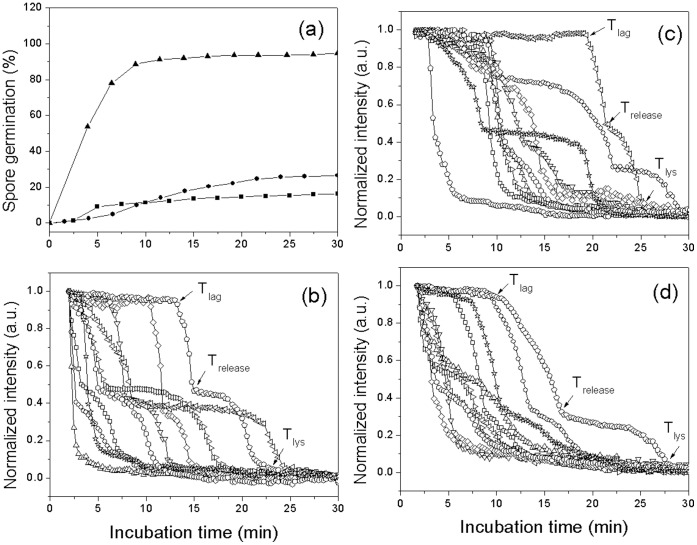

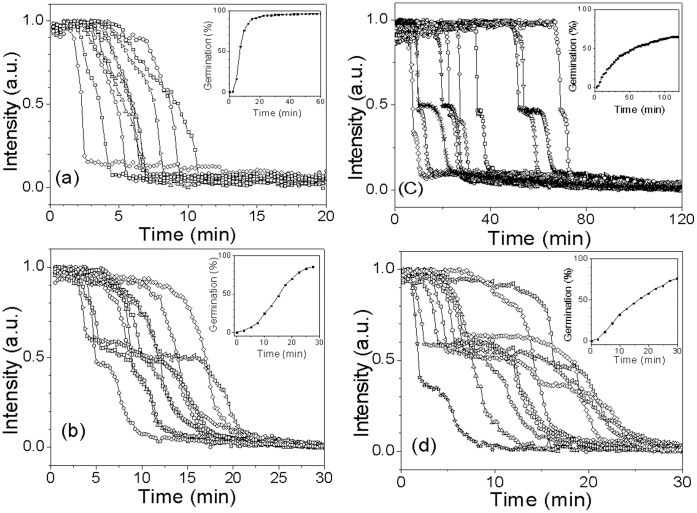

Kinetics of Non-nutrient Germination of Individual G. stearothermophilus Spores

In addition to nutrients, spores can germinate with a variety of non-nutrients [2], [3], including lysozyme, CaDPA, cationic surfactants, high pressures and some salts. Unlike the case with nutrient germination, exogenous CaDPA induced germination of G. stearothermophilus spores at 25°C (Fig. 6; Table 3). However, CaDPA germination of G. stearothermophilus spores was faster at 65°C due largely to a much shorter average T lag value than at 25°C, although the ΔT release values were almost identical at these two temperatures. The average ΔT lys value for CaDPA germination at 25°C was also much longer than for CaDPA germination at 65°C.

Figure 6. Germination of multiple individual G. stearothermophilus spores with CaDPA.

Unactivated spores were germinated with CaDPA at various temperatures, and germination of individual spores was followed by DIC microscopy as described in Methods. Germination at 65°C (▪) or 25°C (•), with germination of ≥380 individual spores examined was shown in (a). Kinetics of germination of ten individual spores at 65°C (b) or25°C (c) was given in (b, c).

Another group of non-nutrient germinants is cationic surfactants, with dodecylamine being the one that has been best studied [31].With 1 mM dodecylamine at 65°C, only ∼ 50% of G. stearothermophilus spores germinated in 120 min, a slow germination compared to those with other germinants, and dodecylamine germination was minimal at 45°C (Fig. 7; Table 3). As seen with CaDPA germination at low and high temperatures, most of the decrease in the rate of germination with dodecylamine at the lower temperature was due to much longer average T lag values.

Figure 7. Germination of multiple individual G. stearothermophilus spores with dodecylamine.

Unactivated spores were germinated at various temperatures with 1(pH 8.0), and germination of ≥470 individual spores was monitored by DIC microscopy. Germination at 65°C (▪), 55°C (•) and 45°C (▴) was shown in (a). Kinetics of germination of ten individual spores at 65°C (b) or 55°C (c) was given in (b, c).

Kinetics of Germination of Individual Decoated G. stearothermophilus Spores

Since at least some proteins involved in spore germination in Bacillus species are located in the spore coats, in particular the CLE CwlJ [2], we also examined the effect of chemical decoating on G. stearothermophilus spores’ germination with nutrient and non-nutrient germinants, all at 65°C (Fig. 8; Table 3). With L-valine and AGFK, the rate of germination of decoated G. stearothermophilus spores decreased by ∼ 15%, while T lag values increased ∼1.5 fold. However, the amount and rate of CaDPA germination of the decoated spores were markedly lower than with intact spores, as the average T lag value increased >6-fold while the average T lys value increased∼13-fold, although the average ΔT release value was essentially unchanged from that for intact spores. Decoating also greatly increased the rate of dodecylamine germination of G. stearothermophilus spores markedly, largely by decreasing the average T lag value (Table 3).

Figure 8. Germination of multiple individual decoated G. stearothermophilus spores.

Heat activated (30 min, 100°C (a,b), or unactivated spores (c,d) were germinated at 65°C with 1 mM L-valine (a); 1 mM AGFK (b); 60 mM CaDPA (c); and 1 mM dodecylamine (d), in 10 mM sodium phosphate buffer (pH 8.0), and germination of individual spores was monitored by DIC microscopy as described in Methods. The insets in the various panels show the percentages of spore germination when ≥224 individual spores (Table 2) were monitored.

Discussion

The work in this communication has revealed a number of similarities in the properties of spores of G. stearothemophilus and Bacillus species, in particular the nearly identical DPA concentrations in these spores’ core. However, there were some differences. One was the lack of change in the Raman spectrum of proteins in G. stearothermophilus spores upon incubation at 95°C. This behavior, as well as the high temperature needed for heat activation of G. stearothermophilus spores, is undoubtedly a reflection of G. stearothermophilus being a thermophile, and is consistent with both the high temperature optimum for germination of spores of this species and their extremely high wet heat resistance compared to spores of B. cereus and B. subtilis [10]. The second difference, and a more intriguing one was the highly variable lag period between T release and the initiation of the second fall in G. stearothermophilus spores’ DIC image intensity during spore germination with all germinants tested, as this has been seen only rarely in germination of spores of Bacillus species [19], [32]. While we have no good explanation for this difference, it is as if there is a much higher threshold for the signal event that begins G. stearothermophilus spore cortex degradation by CLEs following CaDPA release than with spores of Bacillus species. However, these signaling mechanisms are not well understood, so we have no good mechanistic explanation for this difference between spores of these two genera.

While there were the notable differences between G. stearothermophilus and Bacillus spore properties noted above, the overall features of the nutrient and non-nutrient germination kinetics of individual spores of this species were very much like those of Bacillus species. Thus CaDPA release for all G. stearothermophilus spore germinations examined began only after a highly variable T lag period but ΔT release took only a few min, with T release followed by cortex hydrolysis that was completed at T lys. Almost always, ΔT lys was longer than ΔT release, and most of the heterogeneity in the germination between individual spores was in ΔT lag values, as seen previously with spores of Bacillus species [18], [32], [33]. The effects of activation treatments on the germination G. stearothermophilus were also largely, if not completely on T lag values, as average ΔT release and ΔT lys values in nutrient germination of unactivated and maximally activated spores were essentially identical. Optimal heat activation also decreases average T lag values for nutrient germination of spores of Bacillus species [34]. Since a major factor determining the T lag period for nutrient germination of spores of Bacillus species is spores’ levels of functional GRs [33], this further suggests that heat activation of G. stearothermophilus spores for 30 min at 100°C makes these spores’ GRs optimally functional, perhaps by some conformational protein changes as has been suggested for spores of Bacillus species [35]. The mechanism of nitrite activation of spores has never been analyzed in detail, but could be due to covalent modification of the spore cortex by nitrous acid [36]. However, this could equally well be due to nitrous acid modification of GRs.

It was also notable that germination at suboptimal temperatures greatly increased T lag values for nutrient germination of G. stearothermophilus spores, especially given that lower percentages of these spores germinated at lower temperatures in the observation periods used. In contrast, there was essentially no effect on ΔT lys values as the germination temperature was lowered, indicating that the temperature sensitive step in nutrient germination of G. stearothermophilus spores is in T lag, and probably is on the GRs themselves, although there was also a small increase in ΔT release times as germination temperature was lowered. The effect of temperature on kinetics of the germination of individual spores has not been studied with spores of Bacillus species.

Decoating of G. stearothermophilus spores had only a minimal effect on their nutrient germination, with the biggest effect being 1.5 to 2-fold increases in ΔT lys values. The G. stearothermophilus genome has the genes for the two redundant CLEs, CwlJ and SleB, involved in cortex hydrolysis during spore germination in Bacillus species. With Bacillus spores, decoating largely removes or inactivates CwlJ [37], and presumably a decrease in CwlJ level is the reason for the increased ΔT lys values in decoated G. stearothermophilus spores. However, we do not know if all G. stearothermophilus CwlJ is inactivated by the decoating regimen we used. Indeed, decoating or loss of CwlJ by mutation increases values of ΔT release in nutrient germination of spores of several Bacillus species 6- to 10-fold [38], [39], while the increase in decoated G. stearothemophilus spores was at most 2-fold. Thus with G. stearothermophilus spores either CwlJ is not essential for rapid CaDPA release in spore germination, or some active CwlJ survives the decoating regimen used. We favor the latter possibility, since CwlJ is essential for CaDPA germination of spores of Bacillus species [37], [40], while significant CaDPA germination still took place with decoated G. stearothermophilus spores. However, the average T lag value for CaDPA germination increased ∼ 7-fold in decoated G. stearothermophilus spores. Thus it seems most likely that CwlJ is also the primary target of CaDPA in triggering germination of G. stearothermophilus spores.

Along with nutrient germination, G. stearothermophilus spore germination with the non-nutrients CaDPA and dodecylamine also decreased markedly at suboptimal temperatures, again largely due to effects on T lag. However, the latter effect is almost certainly not on GRs, which are not involved in CaDPA and dodecylamine germination of spores of Bacillus species [31], [37]. Indeed, as noted above, CaDPA probably triggers G. stearothermophilus spore germination by activating the CLE CwlJ, while in Bacillus spores dodecylamine likely triggers germination by triggering the opening of the CaDPA channel in the spores’ inner membrane that is composed at least in part of SpoVA proteins [41]. Interestingly, decoating of G. stearothermophilus spores significantly increased these spores’ germination with dodecylamine primarily by decreasing T lag values, just as with spores of Bacillus species [31]. Why this should be is not completely clear, but decoating may allow easier access of dodecylamine to the SpoVA CaDPA channel than in an intact spore.

In summary, the analysis of the dynamics of the germination of multiple individual G. stearothermophilus spores with a variety of germinants indicates that the general features of the germination of these spores appear to be quite similar to those of spores of Bacillus species.

Funding Statement

Authors PS and YL acknowledge support by a Department of Defense Multi-disciplinary University Research Initiative through the U.S. Army Research Laboratory and the U.S. Army Research Office under contract number W911F-09-1-0286. Authors TZ and ZD also acknowledge support by a grant from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31228001) and a grant from the National High Technology Research and Development Program of China (No. 2012AA092103). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1. Paredes-Sabja D, Setlow P, Sarker MR (2011) Germination of spores of Bacillales and Clostridiales species: mechanisms and proteins involved. Trends Microbiol 19: 85–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Setlow P (2003) Spore germination. Curr Opin Microbiol 6: 550–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Paidhungat M, Setlow P (2002) Spore germination and outgrowth. In: Hoch JA, Losick R, Sonenshein AL, editors. Bacillus subtilis and its relatives: from genes to cells. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology. 537–548.

- 4. Moir A (2006) How do spores germinate? J Appl Microbiol 101: 526–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Cowan AE, Koppel DE, Setlow B, Setlow P (2003) A soluble protein is immobile in dormant spores of Bacillus subtilis but is mobile in germinated spores: Implications for spore dormancy. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 100: 4209–4214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pelczar PL, Igarashi T, Setlow B, Setlow P (2007) Role of GerD in germination of Bacillus subtilis spores. J Bacteriol 189: 1090–1098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wang G, Yi X, Li YQ, Setlow P (2011) Germination of individual Bacillus subtilis spores with alterations in the GerD and SpoVA proteins, which are important in spore germination. J Bacteriol 193: 2301–2311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Onyenwoke RU, Brill JA, Farahi K, Wiegel J (2004) Sporulation genes in members of the low G+C Gram-type-positive phylogenetic branch (Firmicutes). Arch Microbiol 182: 182–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Feeherry F, Munsey DT, Rowley DB (1987) Thermal inactivation and injury of Bacillus stearothermophilus spores. Appl Environ Microbiol 53: 365–370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gerhardt P, Marquis RE (1989) Spore thermoresistance mechanisms. In: Smith I, Slepecky RA, Setlow P, editors. Regulation of prokaryotic development. Washington, DC: American Society for Microbiology. 43–63.

- 11. Burgess SA, Lindsay D, Flint SH (2010) Thermophilic bacilli and their importance in dairy processing. Int J Food Microbiol 144: 215–225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Prevost S, Andre S, Remize F (2010) PCR detection of thermophilic spore-forming bacteria involved in canned food spoilage. Curr Microbiol 61: 525–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Loshon CA, Fliss ER, Setlow B, Foerster HF, Setlow P (1986) Cloning and sequencing of genes for small, acid-soluble spore proteins of Bacillus cereus, Bacillus stearothermophilus and “Thermoactinomyces thalpophilus”. J Bacteriol 167: 168–173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Setlow B, Setlow P (1996) Role of DNA repair in Bacillus subtilis spore resistance. J Bacteriol 178: 3486–3495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Clements MO, Moir A (1998) Role of the gerI operon of Bacillus cereus 569 in the response of spores to germinants. J Bacteriol 180: 6729–6735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Paidhungat M, Setlow B, Driks A, Setlow P (2000) Characterization of spores of Bacillus subtilis which lack dipicolinic acid. J Bacteriol 182: 5505–5512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Huang SS, Chen D, Pelczar PL, Vepachedu VR, Setlow P, et al. (2007) Levels of Ca2+-dipicolinic acid in individual Bacillus spores determined using microfluidic Raman tweezers. J Bacteriol 189: 4681–4687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Zhang P, Kong L, Wang G, Setlow P, Li YQ (2010) Combination of Raman tweezers and quantitative differential interference contrast microscopy for measurement of dynamics and heterogeneity during the germination of individual bacterial spores. J Biomed Opt 15: 056010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kong L, Zhang P, Wang G, Setlow P, Li YQ (2011) Characterization of bacterial spore germination using integrated phase contrast microscopy, Raman spectroscopy and optical tweezers. Nat Protocols 6: 625–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bagyan I, Noback M, Bron S, Paidhungat M, Setlow P (1998) Characterization of yhcN, a new forespore-specific gene of Bacillus subtilis . Gene 212: 179–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chen D, Huang SS, Li YQ (2006) Real-time detection of kinetic germination and heterogeneity of single Bacillus spores by laser tweezers Raman spectroscopy. Anal Chem 78: 6936–6941. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Williams RW, Cutrera T, Dunker AK, Peticolas WL (1980) The estimation of protein secondary structure by laser Raman. Spectroscopy from the amide III’ intensity distribution. FEBS Lett 115: 306–308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kitagawa T, Hirota S (2002) Raman spectroscopy of proteins. In: Chalmers JM Griffiths PR, editors. Handbook of vibrational spectroscopy, vol. 5. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley. 3426–3446.

- 24. Zhang P, Kong L, Setlow P, Li YQ (2010) Characterization of wet-heat inactivation of single spores of Bacillus species by dual-trap Raman spectroscopy and elastic light scattering. Appl Environ Microbiol 76: 1796–1805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Coleman WH, Chen D, Li YQ, Cowan AE, Setlow P (2007) How moist heat kills spores of Bacillus subtilis . J Bacteriol 189: 8458–8466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Coleman WH, Zhang P, Li YQ, Setlow P (2010) Mechanism of killing of spores of Bacillus cereus and Bacillus megaterium by wet heat. Lett Appl Microbiol 50: 507–514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Benevides JM, Tsuboi M, Bamford JK, Thomas GJ Jr (1997) Polarized Raman spectroscopy of double-stranded RNA from bacteriophage phi6: local Raman tensors of base and backbone vibrations. Biophys J 72: 2748–2762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Benevides JM, Thomas GJ Jr (1983) Characterization of DNA structures by Raman spectroscopy: high-salt and low-salt forms of double helical poly(dG-dC) in H2O and D2O solutions and application to B, Z and A-DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 11: 5747–5761. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Foerster HF (1983) Activation and germination characteristics observed in endospores of thermophilic strains of Bacillus . Arch Microbiol 134: 175–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Foerster HF (1985) The effects of alterations in the suspending medium on low-temperature activation of spores of Bacillus stearothermophilus Ngb101. Arch Microbiol 142: 185–189. [Google Scholar]

- 31. Setlow B, Cowan AE, Setlow P (2003) Germination of spores of Bacillus subtilis with dodecylamine. J Appl Microbiol 95: 637–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kong L, Zhang P, Setlow P, Li YQ (2010) Characterization of bacterial spore germination using integrated phase contrast microscopy, Raman spectroscopy and optical tweezers. Anal Chem 82: 3840–3847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Setlow P, Liu J, Faeder JR (2012) Heterogeneity in bacterial spore population. In: E Abel-Santos, editor. Bacterial spores: current research and applications. Norwich, UK: Horizon Scientific Press. 201–216.

- 34.Setlow P, Johnson EA (2012) Spores and their significance. In: Doyle MP, Buchanan R, editors. Food microbiology, fundamentals and frontiers. Washington, DC: ASM Press. 45–79.

- 35. Zhang P, Setlow P, Li YQ (2009) Characterization of single heat-activated Bacillus spores using laser tweezers Raman spectroscopy. Opt Expr 17: 16481–16491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ando Y (1980) Mechanism of nitrite-induced germination of Clostridium perfringens spores. J Appl Microbiol 49: 527–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Paidhungat M, Ragkousi K, Setlow P (2001) Genetic requirements for induction of germination of spores of Bacillus subtilis by Ca2+-dipicolinate. J Bacteriol 183: 4886–4893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Peng L, Chen D, Setlow P, Li YQ (2009) Elastic and inelastic light scattering from single bacterial spores in an optical trap allows monitoring of spore germination dynamics. Anal Chem 81: 4035–4042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Setlow B, Peng L, Loshon CA, Li YQ, Christie G, et al. (2009) Characterization of the germination of Bacillus megaterium spores lacking enzymes that degrade the spore cortex. J Appl Microbiol 107: 318–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Heffron JD, Lambert EA, Sherry N, Popham DL (2010) Contributions of four cortex lytic enzymes to germination of Bacillus anthracis spores. J Bacteriol 192: 763–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Vepachedu VR, Setlow P (2007) Role of SpoVA proteins in the release of dipicolinic acid during germination of Bacillus subtilis spores triggered by dodecylamine or lysozyme. J Bacteriol 189: 1565–1572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]