Abstract

Current observations link vitamin D deficiency to many autoimmune diseases. There are limited data on vitamin D in Alopecia Areata, an autoimmune disease which in our experience shows seasonality in most of its remitting-relapsing forms. Our results demonstrate the presence of insufficiency of 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25OH-D) in many patients with various clinical forms, correlated with the expected increase of the values of Parathyroid Hormone (PTH). This could suggest the possible clinical use of vitamin D in the management of this frustrating disease.

Keywords: Alopecia Areata, autoimmunity, seasonality, vitamin D

Despite the high prevalence of autoimmune diseases, their etiology and pathogenesis remain not fully understood with regards to the factors implicated in their pathogenesis. Current data link vitamin D deficiency to many autoimmune diseases including type 1 Diabetes Mellitus, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, Rheumatoid Arthritis, inflammatory bowel diseases, autoimmune Thyroiditis and Psoriasis. This suggests that vitamin D might be an environmental factor that normally participates in the control of self-tolerance. This could happen through its ability to prevalently inhibit immune responses TH1.1

The optimal level for 25-hydroxyvitamin D (25OHD), the most stable and reliable parameter to evaluate vitamin D status and responsible for bone health, begins at 30 ng/ml even though the 25OHD level required to maintain optimal immune system homeostasis has not been established yet (although several reports estimate it would be superior to 40 ng/ml).2 Vitamin D deficiency is frequently found in countries where wintertime UV light is absent and although diet should integrate this lack, it appears often inadequate to do so. The most frequently reported associations were detected between the relatively high prevalence of Multiple Sclerosis, Diabetes I and inflammatory bowel disease in northern regions, and the lower exposure to sunlight in these geographical locations.

Some years ago we demonstrated a statistical significant seasonality in the appearance of Alopecia Areata (AA) in the majority of adult patients suffering from remitting-relapsing forms, independently from an atopic diathesis.3 Its prevalence was higher in the autumn/winter months and appeared few weeks before the classic seasonal period of telogen effluvium. This can be explained by the greater exposure of the follicular autoantigens in the Catagen phase preceding the seasonal molt or with the presence of a protective factor related to summer and it disappears with the cold period. Subsequently we also noticed that the seasonal relapses were influenced year by year via the trend of average temperatures for the period and therefore, presumably, on whether or not the subjects could be exposed outdoors.4

A recent Turkish paper has shown a vitamin D deficiency in severe forms of AA.5 This research, however, was performed in only 42 cases, and during summer, when it is possible—at least in our experience—that these patients were exposed outdoors less than the healthy population for reasons of psychological distress. At this point we decided to check a larger group of 156 patients affected by chronic relapsing/remitting AA with an involvement of more than 25% of the scalp area, mean age 37.7 (45 males with mean age 32.2, 111 females with mean age 40.1, not overweight and not in steroid therapy for at least one year), enrolled in “National Mediterranean Alopecia Areata Association” (www.alopecia-italy.com) between October/March 2010 and 2012 (Table 1). This research aimed to verify that, in the autumn/winter periods of two consecutive years, the observed patients presented a vitamin D deficiency assessed by a chemilumiscence assay of plasmatic 25OHD. Parathyroid hormone (PTH) was also evaluated with the same method. Almost all patients had participated in a previous study that showed an imbalance of the hypothalamic-pituitary adrenal axis in chronic-relapsing forms of the disease, presenting a significantly low level of plasmatic DHEA-S in the presence of normal or slightly increased cortisol levels (evaluated by RIA assay). This alteration is probably primitive because it is already present during the first episode of the disease as well as in younger patients, and it is probably important in the pathogenesis of the disease, given the recognized anxiolytic/antidepressant and immunomodulating abilities of DHEA.6

Table 1. Case study (Patients with chronic/relapsing AA with > 25% scalp hair area affected).

| Cases examined |

156 (not obese and not in steroid therapy since one year at least) |

| Gender |

45 M, 111 F |

| Mean age (years) |

37.8 (Men 32.2, Women 40.1) |

| Duration of disorder |

49 mo (6m-20y) |

| Positive family history |

42% |

| Clinical forms |

49 (31,5%) AA multilocularis, 69 (44%) Ophyasis, 38 (24,5%) AT-AU |

| Activity of the disease* |

57% active, 43% in stationary/remission phase |

| Observation period |

October–March 2010–2012 |

| Controls |

148 (18 M, 130 F) |

| Mean age (years) | 34.5 |

* Evaluated by perilesional Trichogram (AT/AU excluded)

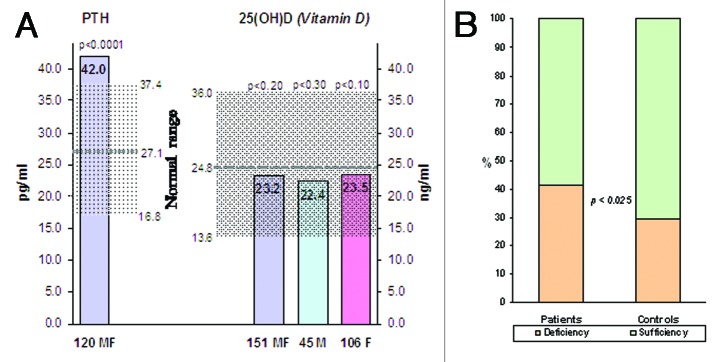

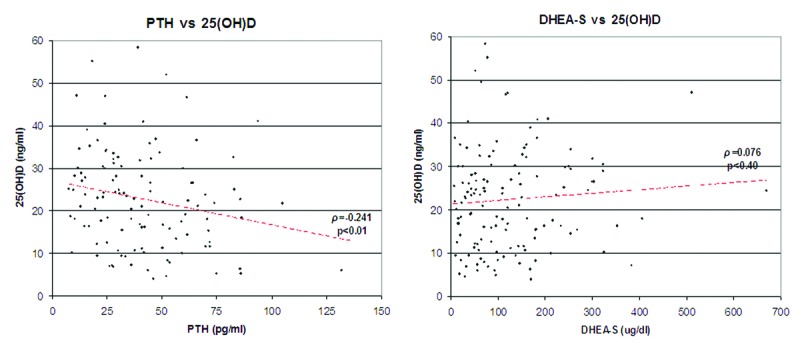

Our results confirm the presence of insufficiency/deficiency of 25OHD in the patients’ group, although the results were not significantly different compared with our 148 controls (18 males, 130 females, mean age 34.5). This is due to the universal tendency to lower values of 25OHD also in the “normal” population of our latitudes (Fig. 1A).7 It has to be pointed out, however, that the state of true deficiency, under 20 ng/ml,8 is present in 42.4% of patients, and, in particular, in 44.4% of men and 41.5% of women, significantly higher (p < 0.025), using the z-test, than the 29.5% of healthy controls (Fig. 1B). It is also significant in our patients the parallel compensatory increase of PTH, which confirms the presence of a real deficiency of vitamin D (r = -0.24, p < 0.01). On the other hand a significant direct correlation between levels of 25OHD and DHEA-S (r = 0.076, p < 0.40) has not been found, suggesting that we are probably facing two independent factors of risk for the onset/persistence of the disease (Fig. 2). All correlations were measured by Spearman rho and statistically verified by t-test.

Figure 1. (A) 25(OH)D in Patients and Controls. (B) Percentage of cases by deficiency cut-off level of 25OHD.

Figure 2. Negative correlation for 25OHD/PTH, no correlation for reduced values of 25OH D/DHEA-S.

In conclusion, in the comparison of patients vs. controls, patients have more rates of 25OHD deficiency and higher mean values of PTH of the controls, with significant inverse correlation between them. We confirm that the decreased level of 25OHD was not correlated with pattern or extent of hair loss.5 These results encourage clinical trials to evaluate the potential role of vitamin D in clinical management of chronic relapsing-remitting cases of AA, considering that vitamin D has been shown to provide clinical benefits in animal autoimmunity models, and that initial observations indicate that vitamin D supplementation may be preventive in human autoimmune diseases, such as Multiple Sclerosis and—above all—Diabetes Mellitus, where the risks are significantly reduced in infants treated with vitamin D, and—this seems to be very important—with a dose-response effect.9 Furthermore, dermatologists have noticed some time ago the therapeutic properties of vitamin D and its derivatives in Psoriasis, a disease where, beyond the pro-differentiating role of vitamin, certainly come into play its ability to inhibit the immunitary TH1 responses through the Induction of Dendritic Cells with tolerogenic properties and the activation of regulatory T cells.10 Indeed it has already been suggested that activation of these same cells can explain the possible efficacy also in the treatment of AA with analogs of vitamin D.11

Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest

No potential conflicts of interest were disclosed.

Footnotes

Previously published online: www.landesbioscience.com/journals/dermatoendocrinology/article/24411

References

- 1.Arnson Y, Amital H, Shoenfeld Y. Vitamin D and autoimmunity: new aetiological and therapeutic considerations. Ann Rheum Dis. 2007;66:1137–42. doi: 10.1136/ard.2007.069831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Souberbielle JC, Body JJ, Lappe JM, Plebani M, Shoenfeld Y, Wang TJ, et al. Vitamin D and musculoskeletal health, cardiovascular disease, autoimmunity and cancer: Recommendations for clinical practice. Autoimmun Rev. 2010;9:709–15. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2010.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.d’Ovidio R, d’Ovidio F. Recidive stagionali dell'Alopecia Areata. G Ital Dermatol Venereol. 1995;295:130–4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.d’Ovidio R. Alopecia Areata. G Ital Tricol 2009; 24:5-40. Available from: http://www.sitri.it/GITri.download/gitri24.pdf.zip

- 5.Yilmaz N, Serarslan G, Gokce C. Vitamin D concentration are decreased in patients with alopecia areata. Vitam Trace Elem. 2012;1:105–9. doi: 10.4172/2167-0390.1000105. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.d’Ovidio R, d’Ovidio FD. Hyposecretion of the Adrenal Androgen Dehydroepiandrosterone Sulfate (DHEA-S) in the Majority of the Alopecia Areata Patients: Is it a Primitive and Pathogenic Perturbation of Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis? Int J Trichology. 2011;3:43–4. doi: 10.4103/0974-7753.82130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carnevale V, Modoni S, Pileri M, Di Giorgio A, Chiodini I, Minisola S, et al. Longitudinal evaluation of vitamin D status in healthy subjects from southern Italy: seasonal and gender differences. Osteoporos Int. 2001;12:1026–30. doi: 10.1007/s001980170012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ross AC, Manson JE, Abrams SA, Aloia JF, Brannon PM, Clinton SK, et al. The 2011 report on dietary reference intakes for calcium and vitamin D from the Institute of Medicine: what clinicians need to know. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96:53–8. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-2704. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Antico A, Tampoia M, Tozzoli R, Bizzaro N. Can supplementation with vitamin D reduce the risk or modify the course of autoimmune diseases? A systematic review of the literature. Autoimmun Rev. 2012;12:127–36. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2012.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Penna G, Roncari A, Amuchastegui S, Daniel KC, Berti E, Colonna M, et al. Expression of the inhibitory receptor ILT3 on dendritic cells is dispensable for induction of CD4+Foxp3+ regulatory T cells by 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3. Blood. 2005;106:3490–7. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-05-2044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim DH, Lee JW, Kim IS, Choi SY, Lim YY, Kim HM, et al. Successful treatment of alopecia areata with topical calcipotriol. Ann Dermatol. 2012; 24341-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]