Summary

Studies of aging and longevity are revealing how diseases that shorten life can be controlled to improve the quality of life and lifespan itself. Two strategies under intense study to accomplish these goals are rapamycin treatment and calorie restriction. New strategies are being discovered including one that uses low-dose myriocin treatment. Myriocin inhibits the first enzyme in sphingolipid synthesis in all eukaryotes and we showed recently that low-dose myriocin treatment increases yeast lifespan at least in part by down-regulating the sphingolipid-controlled Pkh1/2-Sch9 (ortholog of mammalian S6 kinase) signaling pathway. Here we show that myriocin treatment induces global effects and changes expression of approximately forty percent of the yeast genome with 1252 genes up-regulated and 1497 down-regulated (p < 0.05) compared to untreated cells. These changes are due to modulation of evolutionarily conserved signaling pathways including activation of the Snf1/AMPK pathway and down-regulation of the Protein Kinase A (PKA) and Target of Rapamycin Complex 1 (TORC1) pathways. Many processes that enhance lifespan are regulated by these pathways in response to myriocin treatment including respiration, carbon metabolism, stress resistance, protein synthesis and autophagy. These extensive effects of myriocin match those of rapamycin and calorie restriction. Our studies in yeast together with other studies in mammals reveal the potential of myriocin or related compounds to lower the incidence of age-related diseases in humans and improve health span.

Keywords: TORC1, AMPK, S6 Kinase, aging, myriocin, sphingolipids

Introduction

Recent progress in aging research opens the possibility of reducing the incidence of age-related diseases in humans and improving the quality of life or health span as well as increasing overall lifespan. One promising pharmacological strategy for simultaneously reducing many diseases of aging uses the natural product rapamycin to inhibit the evolutionarily conserved target of rapamycin protein kinase complex 1 (TORC1) (Kapahi et al. 2010; Longo et al. 2012). Rapamycin treatment and calorie restriction enhance lifespan in a wide range of organisms and they appear to do so by regulating similar processes such as autophagy (Fontana et al. 2010; Rubinsztein et al. 2011). The capacity of rapamycin to reduce age-related diseases, particularly cancers, is being tested in multiple clinical trials. We recently presented another strategy for reducing aging and enhancing lifespan that involves down-regulating sphingolipid synthesis by myriocin treatment (Huang et al. 2012). Here we show that myriocin modulates a wide array of signal transduction pathways and cellular processes, similar to those controlled by caloric restriction and rapamycin.

Myriocin is a natural product produced by several fungal species that inhibits the activity of serine palmitoyltransferase (SPT), the first enzyme in sphingolipid biosynthesis. Myriocin enhances chronological lifespan (CLS), measured as length of viability in stationary or a Go phase (Longo et al. 2012), in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by reducing the activity of a signaling pathway composed of the sphingolipid-controlled Pkh1 and Pkh2 protein kinases and one of their downstream targets, the Sch9 protein kinase (Huang et al. 2012). Pkh1/2 are redundant, functional homologs of mammalian phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase 1, while Sch9 is related to mammalian S6 kinase (Urban et al. 2007) and both kinases have proven roles in regulating lifespan (Fabrizio et al. 2001; Selman et al. 2009; Longo et al. 2012). Sch9 is under dual control, so besides phosphorylation of residue T570 in its activation loop by Pkh1 or Pkh2, it must also be phosphorylated at several C-terminal residues by TORC1 to be active (Urban et al. 2007). Dual regulation enables cells to fine tune the balance between growth rate and stress resistance by integrating nutrient and stress signals from both TORC1 and sphingolipids.

Myriocin also appeared to increase CLS independently of Sch9, since the already long lifespan of sch9Δ cells was enhanced by myriocin treatment (Huang et al. 2012). To gain a more global view of how myriocin improves lifespan, we compared the transcriptional profile of myriocin-treated and untreated cells. This comparison reveals multiple signaling pathways and cellular processes that respond to myriocin treatment including TORC1 and protein kinase A, which have known evolutionarily conserved roles in aging, since reducing their activity enhances lifespan (Fontana et al. 2010; Longo et al. 2012). Validation experiments show that myriocin treatment reduces the activity of these kinases and modulates processes they control. Surprisingly, myriocin treatment induces activity of the SNF1/AMP-activated protein kinase (AMPK), a key regulator of energy metabolism and stress survival. AMPKs are evolutionarily conserved and the human protein has many roles in normal physiology and diseases including ones associated with aging (Hardie et al. 2012). Snf1/AMPK, TORC1 and PKA all regulate autophagy in yeast (De Virgilio 2012) and we show that this process is activated by myriocin treatment. By promoting the breakdown and reutilization of intracellular substrates and maintenance of organelle homeostasis, autophagy enhances lifespan in many organisms (Rubinsztein et al. 2011). Myriocin treatment also influences other protein kinases and cellular processes and further effort will be needed to determine if any of these contribute to lifespan enhancement.

Results

Myriocin Treatment Changes Expression of Many Genes

To identify new signaling pathways and cellular processes controlled by sphingolipids and that might also enhance CLS, we examined gene expression in cells grown for 8–9 generations to log phase (A600nm of 2) in the presence of myriocin. This strategy lowers SPT activity and the rate of sphingolipid synthesis and lengthens lifespan, at least in part, by reducing activity of the Pkh1/2-Sch9 signaling pathway (Fig. 1) (Huang et al. 2012). Myriocin-treated cells display global transcriptional changes compared to untreated cells with 1252 annotated genes up-regulated and 1497 down-regulated (2749 genes, p < 0.05, FDR of 0.08, Table S1).

Fig. 1. Summary of Pathways and Processes Vital for Long Life with Potential Links to Myriocin Treatment.

(A) This diagram summarizes known links between inducers (nutrients and stresses), signaling pathways, transcription factors (TFs), cellular processes vital of CLS, and GO terms enriched in the myriocin-responsive gene set. Activation, inhibition and repression are not indicated in order to emphasize linkage relationships. Details about signaling pathways can be found in a review (De Virgilio 2012). TFs are ones with known roles in longevity and were selected from those predicted to control expression of myriocin-responsive genes (Table S3). Shown in red (up-regulated genes) or green-shaded boxes (down-regulated genes) at the bottom of the Figure are enriched GO terms which support inclusion of the indicated signaling pathways, transcription factors and cellular processes. Abbreviations: HAP, Hap2/3/4/5 complex; NDP, nitrogen discrimination pathway; AA syn, amino acid biosynthesis.

To decipher the biological meaning of myriocin-responsive genes, we analyzed their gene ontology (GO) terms (Fig. 1 and Table S2). The top ranking GO terms for up-regulated genes include many associated with long lifespan such as Energy Generation, Oxidative Phosphorylation, Mitochondrion, Stress Responses, and Autophagy (Fig. 1, Pink boxes and Table S2) (Fabrizio et al. 2010; Longo et al. 2012). Terms with less established roles in lifespan and aging include the Actin Cytoskeleton, Endocytosis and Peroxisomes. The highest ranked GO term, Vacuolar Protein Catabolic Process, will be addressed below as it contains connections to CLS. The most prominent GO terms linked with down-regulated genes include Ribosome, Cytoplasmic and Mitochondrial Translation (Fig. 1, green box, Table S2), known components of longevity, and Endoplasmic Reticulum, Glycoprotein and Lipid Biosynthesis, whose roles in yeast lifespan are less established (Table S2) (Fabrizio et al. 2010; Longo et al. 2012).

Since myriocin treatment alters expression of a large number of genes, the effect of using more stringent cutoff criteria on the apparent biological meaning of our dataset was examined. Requiring a 2-fold change in gene expression or using p<0.001 (FDR of 0.01) reduces the dataset from 3241 (before removal of non-annotated genes) to just under 900 genes, but does not significantly change the major GO categories, indicating that the GO terms associated with the 2749 annotated genes in our dataset have a high likely hood of representing true responses to myriocin treatment.

As a further check on the predictive value of our myriocin-responsive gene set, we examined the overlap with a set of 2347 genes controlled by Sch9 (Huber et al. 2011), since overlap is expected because myriocin treatment reduces Sch9 activity (Huang et al. 2012). We find that 741 genes are regulated in the same direction in both data sets, indicating statistically significant overlap (p< 0.001) (Table 1).

Table 1.

Overlap of genes regulated by myriocin treatment and known signaling pathways known to play roles in yeast lifespan (significance calculated by using the Chi-Square test).

| Gene sets compared to 2749 myriocin-responsive genes |

Gene matches/ Genes in Reference |

p value | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Sch9-regulated genes | 741/2347 | <0.001 | (Huber et al. 2011) |

| Calorie restriction (0.5% Glu) | 73/160 | <0.001 | (Lee & Lee 2008) |

| Environmental stress response | 414/867 | <0.001 | (Gasch et al. 2000) |

| Snf1-regulated genes Snf1-Nrg1/2 “ “ |

95/745 116/413 |

0.002 <0.001 |

(Young et al. 2003) (Vyas et al. 2005) |

| TORC1-regulated genes | 280/793 | <0.001 | (Urban et al. 2007) |

Additional pathways and processes regulated by sphingolipids were uncovered by examining overlap between myriocin-responsive genes and published data. Calorie restriction and the TORC1, PKA and Snf1/AMPK signaling pathways modulate key functions in the diauxic shift including regulation of genes with proven roles in long lifespan (Fontana et al. 2010; De Virgilio 2012; Longo et al. 2012). We find a significant overlap between myriocin-responsive genes and genes controlled by calorie restriction (Lee & Lee 2008) (Table 1), which supports the premise that myriocin treatment affects signaling pathways and processes similar to those used by calorie restriction to increase lifespan. The signaling pathways also stand out as links between CLS and genes or GO terms in our myriocin-responsive gene list based on the current literature: these connections are shown diagrammatically in Fig. 1. Finally, a literature search shows that the same signaling pathways control many of the transcription factors predicted to regulate expression of myriocin-responsive genes and their associated GO terms which are enriched in our gene set (Fig. 1 and Table S3).

Acetic acid accumulation in culture medium during a CLS assay has been implicated as a major factor in viability loss (Burtner et al. 2009; Longo et al. 2012). To show that myriocin treatment is not simply enhancing CLS by preventing acetic acid killing, we assayed CLS in medium buffered to pH 6 with a citrate-phosphate buffer (Burtner et al. 2009; Longo et al. 2012). Three common strains backgrounds (DBY746, BY4741 and BY4743) were examined and myriocin treatment increased CLS in all strains (Fig. S1A), supporting our hypothesis that myriocin is reprogramming cells for a long lifespan, not simply increasing lifespan by preventing acetic acid killing.

The effect of myriocin on growth rate was examined also, since a slightly higher dose of myriocin than was used in most of the experiments described here (600 ng/ml instead of 400 ng/ml) was needed to increase CLS in BY4741 and BY4743 cells. Myriocin reduces growth rate for about 24 hrs, but thereafter cells grow rapidly and reach the same density or a higher density than untreated cells by 72 hrs of incubation (Fig. S1B), similar to our previous data for DBY746, R1158 and BY4741 cells (Huang et al. 2012).

Myriocin Treatment Reduces PKA Activity

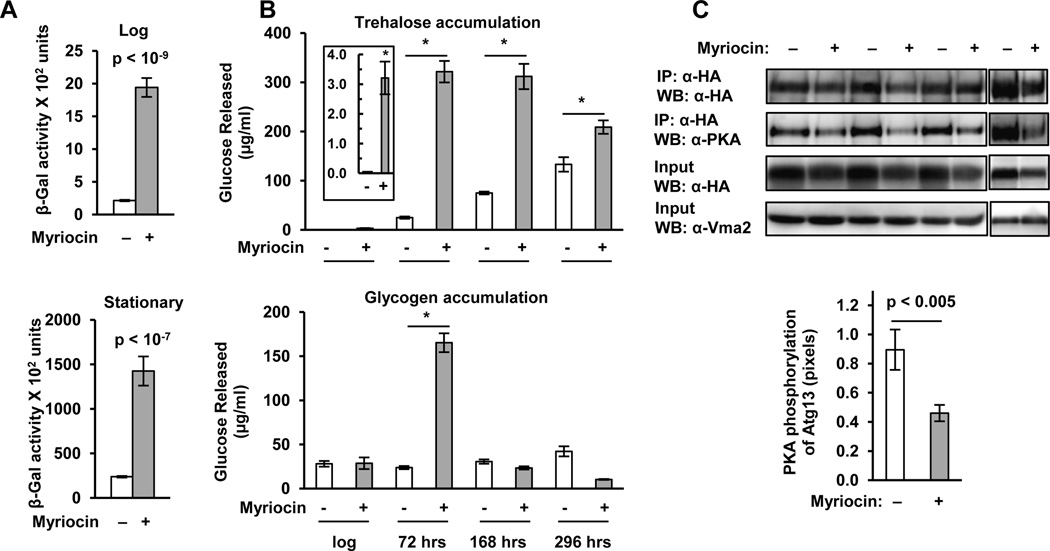

Increased stress resistance is a common feature of mutant strains or treatments that increase CLS (Fabrizio et al. 2001; Longo et al. 2012). Since Cellular Response to Stress is a high ranking GO term in our gene set (Fig. 1 and Table S2), we compared the myriocin-response genes to a set of genes that respond to a variety of environmental stresses and found significant overlap (Table 1). We also directly examined expression of stress response genes. Log phase cells have low stress resistance, but environmental stresses or the diauxic shift activate stress defenses by reducing the activity of the PKA and TORC1-Sch9 pathways which allows the Msn2/4 transcription factors (Fig. 1) to move from the cytosol to the nucleus and activate stress response genes with STRE elements in their promoter (Gasch et al. 2000; De Virgilio 2012). To demonstrate that myriocin treatment activates genes with STRE elements, we used a STRE-lacZ reporter gene. Myriocin treatment induces lacZ expression 9-fold in log phase cells and 6-fold in stationary phase cells (Fig. 2A), verifying that myriocin increases expression of genes with STRE promoter elements.

Fig. 2. Myriocin Treatment Reduces PKA Pathway Activity.

(A) Activation of environmental stress response genes is indicated by units of β-galactosidase activity in DBY746 cells (pSTRE-lacZ) treated or not treated with myriocin and grown to log (A600nm of 2) or stationary phase (72 hrs). The average ± S.D. of 3 cultures is indicated in each bar graph. (B) Accumulation of trehalose (upper panel) and glycogen (lower panel) was determined in DBY746 cells (+/− myriocin). The insert in the upper panel shows the trehalose content of log phase cells (A600nm of 2). Average ± S.D. values for 3 cultures are indicated in each bar graph (* = p < 0.001). (C) The level of PKA-mediated phosphorylation of Atg13 was determined in DBY746 (pRS426, ATG13-HA) cells grown to an A600nm of 1 by immunoblotting of Atg13-HA protein in extracts (input) or protein that was immunoprecipitated (IP) and blotted for total HA-tagged protein (anti-HA) or protein phosphorylated by PKA (anti-Atg13P). Vma2 is the protein loading control. Quantification of the ratio of PKA-phosphorylated Atg13 to total Atg13 for the four blots shown in the upper panel is summarized in the lower panel.

We confirmed the STRE-lacZ and GO term data by examining heat and oxidative stress resistance. Myriocin treatment increases resistance to heat and oxidative stress (H2O2, Fig. S2) in log phase cells and further increases resistance in stationary phase cells. Oxidative stress induced by menadione, a superoxide generator, is bolstered by myriocin treatment in log but not stationary phase cells (Fig. S2). These data verify our microarray results and show that myriocin down-regulates the PKA and TORC1-Sch9 pathways to allow Msn2/4 to activate gene expression and promote stress resistance (Gasch et al. 2000; De Virgilio 2012).

The highest ranking GO term in the up-regulated gene set is Vacuolar Protein Catabolic Process and it contains many genes functioning in stress resistance and longevity including trehalose metabolism, which is the most statistically significant metabolic process represented in this GO term. The PKA pathway prevents trehalose buildup in log phase cells by both transcriptional and post-translational mechanisms (De Virgilio 2012). As another way to show that myriocin-treatment stimulates metabolic remodeling in log phase cells by reducing PKA activity, we examined trehalose metabolism. There is a significant increase in the trehalose content of log phase cells treated with myriocin and the level continues to rise in stationary phase cells (Fig. 2B). PKA also controls glycogen accumulation and the level of glycogen in myriocin-treated cells is higher than in untreated cells at 72 hrs of incubation or the end of the diauxic shift (Fig. 2B).

The PKA and TORC1 pathways independently inhibit autophagy by phosphorylation of the Atg13 protein, which impairs formation of pre-autophagosomal structures (Stephan et al. 2009). As another way to demonstrate that myriocin treatment reduces PKA activity, we measured Atg13 phosphorylation by using an antibody that detects PKA-specific phosphorylation (Stephan et al. 2009). Myriocin treatment produces a statistically significant decrease in PKA-mediated phosphorylation of Atg13 (Fig. 2C). This decrease should promote autophagy and we verify this prediction as shown below.

We showed previously that down-regulating sphingolipid synthesis by use of a doxycycline (Dox)-regulated promoter (tetO7) to reduce expression of the LCB1 or LCB2 genes, which encode subunits of SPT, increased CLS, indicating that CLS extension by myriocin treatment is due to down-regulation of sphingolipid synthesis and not to a non-specific effect (Huang et al. 2012). To further establish that the myriocin-mediated effects we report here are due to down-regulation of SPT activity, we examined the effect of down-regulating LCB1 expression on PKA-mediated phosphorylation of Atg13. For these experiments cells with a tetO7-LCB1 gene were treated with Dox and Atg13 phosphorylation by PKA was examined (Fig. S3A). The data indicate that Dox treatment significantly reduces Atg13 phosphorylation, similar to what we find in myriocin-treated cells.

Myriocin Treatment Reduces TORC1 Activity

TORC1 controls ribosome formation and protein synthesis in response to nutrients and stresses in multiple ways, some of which are well delineated (Loewith & Hall 2011). Both rapamycin treatment and calorie restriction down-regulate ribosome formation and translation by lowering expression of many genes required for these processes (Loewith & Hall 2011; De Virgilio 2012). Myriocin produces similar effects since Ribosome and Translation are two of the highest ranking GO terms associated with genes down-regulated by myriocin treatment (Fig. 1 and Table S2). However, these genes and GO terms could appear in the myriocin-responsive gene set because Sch9 activity is reduced via the Pkh1/2-Sch9 (T570-P) pathway rather than by reduced TORC1 phosphorylation of C-terminal Sch9 residues (Fig. 1) (Urban et al. 2007). To determine if myriocin treatment reduces TORC1 activity, C-terminal Sch9 phosphorylation was examined. We find a 60% reduction in Sch9 C-terminal phosphorylation in cells treated with a standard dose of myriocin (Fig. 3A, 400 ng/ml) and a 72% reduction (p < 0.001) with a higher dose of myriocin (600 ng/ml, data not shown). These data show that myriocin treatment down-regulates TORC1 activity towards Sch9.

Fig. 3. Myriocin Treatment Reduces TORC1 Pathway Activity.

(A) Myriocin treatment reduces TORC1-mediated phosphorylation of C-terminal residues in Sch9. Immunoblots of cell-free extracts made from DBY746 (pRS416, SCH9-5HA) cells (+/− myriocin) and grown to an A600nm of 1 are shown. Top panel – extracts were chemically treated to cleave Sch9 and the phosphorylated (+P) and dephosphorylated (−P) species are indicated (Urban et al. 2007). Middle panel – Vma2 level used as a loading control in chemically-treated extracts. Bottom panel – untreated extracts blotted for total Sch9-5HA protein. The average ± S.D. of the ratio of pixels in the +P and −P species from four replicas is shown graphically. (B) Myriocin treatment promotes TORC1-dependent dephosphorylation of Gln3. Assay of mobility shift of Myc-tagged Gln3 in DBY746 (pRS314,GLN3×13Myc) cells (+/− myriocin) grown to an A600nm of 1. Rapamycin-treated cells are a positive control for indicating strong down-regulation of the TORC1 pathway. (C) Expression of the MEP2-lacZ reporter gene is shown as β-galactosidase activity in DBY746 (YCpMEP2-lacZ) cells grown to an A600nm of 2. The average ± S.D. of 3 cultures is indicated in each bar graph.

Another branch of TORC1 signaling regulates Gln3, a transcription activator of genes involved in nitrogen metabolism (Fig. 1) (De Virgilio 2012). Active TORC1 phosphorylates Gln3 which binds to Ure2 and is tethered in the cytosol (Beck & Hall 1999). Reducing TORC1 activity releases bound Tap42-Sit4 phosphatase and enables it to dephosphorylate Gln3, which translocates to the nucleus and activates transcription of genes such as MEP2 encoding an ammonium transporter (Marini et al. 1997). Gln3 dephosphorylation can be observed as a shift to a faster migrating species on SDS-PAGE (Beck & Hall 1999) and we find that myriocin treatment causes partial shifting of Gln3 to a faster migrating species (Fig. 3B). The mobility shift is not as complete as seen in cells treated with rapamycin, indicating that myriocin does not down-regulate TORC1 as strongly as rapamycin.

As another measure of the effect of myriocin on TORC1 activity, we used a MEP2-lacZ reporter gene and find a 3-fold induction of β-galactosidase activity in myriocin-treated cells (Fig. 3C). Again, rapamycin treatment more strongly down-regulates TORC1 activity as seen by the 65-fold increase in β-galactosidase activity. The data presented in Fig. 3 show that myriocin treatment down-regulates TORC1 activity and they validate the enrichment of the GO terms and processes that are regulated by TORC1 (Fig. 1) including enrichment of the GO term Nitrogen Compound Biosynthetic Process (Table S2).

Myriocin Treatment Activates Snf1

We noted previously that oxygen consumption is higher in myriocin-treated cells than in untreated cells, which implies that myriocin induces Snf1 activity and up-regulates Snf1-dependent gene expression which is vital for increasing respiration (Huang et al. 2012). Enrichment of genes linked to the GO terms Energy Generation, Oxidative Phosphorylation and Mitochondrion in the myriocin up-regulated gene set also supports Snf1 activation in myriocin-treated cells (Fig. 1 and Table S2), as does the significant overlap with genes regulated by Snf1/Adr1 (Table 1).

To garner more direct support for Snf1 activation in myriocin-treated cells, we examined expression of the ADH2-lacZ reporter gene whose transcription is driven primarily by the Adr1 transcription factor when Snf1 is active (Young et al. 2003). ADH2-lacZ expression is low in glucose-repressed, untreated log phase cells but is 20-fold higher in myriocin-treated cells (Fig. 4A). This effect of myriocin is present even in stationary phase cells where glucose no longer represses Snf1 activity. Thus, myriocin activates the Snf1-Adr1 pathway in the presence of glucose and seems to do so even after glucose is consumed and cells enter the post-diauxic state. The Nrg1 and Nrg2 proteins mediate glucose repression of genes with STRE and related promoter elements (Vyas et al. 2005). The significant overlap of genes regulated by Nrg1/2 and genes induced by myriocin treatment (Table 1) is another indication that myriocin treatment activates Snf1 activity. Another indication of Snf1 activation in myriocin-treated log phase cells is the 10-fold increase in CAT8 expression (Table S1): CAT8 expression is repressed by Mig1 in log phase cells (De Virgilio 2012) but myriocin relieves this inhibition.

Fig. 4. Myriocin Treatment Activates the Snf1 Pathway.

(A) Activation of the ADH2-lacZ reporter gene is shown as β-galactosidase activity in DBY746 (pBGM18-ADH2-lacZ) cells grown to log (A600nm of 2) or stationary phase (72 hrs). The average ± S.D. of 3 cultures is indicated in each bar graph (* = ρ < 1 × 10−7). (B) Effect of myriocin treatment on the phosphorylation level of endogenous Snf1 residue T210 was determined in DBY746 cells grown to an A600nm of 1 by immunoblotting for total Snf1 protein (top panel), phospho-T210 (middle panel) or the Vma2 protein loading control (bottom panel). Quantification of the ratio of phosphorylated T210 to total Snf1 for the four samples analyzed in the upper two panels is summarized in the bar graph. (C) The viability of DBY746 and snf1 mutant cells was determined in cells treated or not treated with myriocin. Survival (viable colonies) values were normalized to the day 1 (24 hr) time point because snf1 mutant cells begin to die at this time. DBY746 cells treated with myriocin grow slowly and do not reach stationary phase until around day 2, which is why their viability rises from day 1 to day 2. The dotted line represents the data for DBY746 cells treated with myriocin but normalized to day 3, as in a standard CLS assay.

To verify that myriocin treatment produces global cellular effects because of a reduction in SPT activity, we examined the effect of Dox treatment in cells carrying the tetO7-LCB1 allele on expression of the ADH2-lacZ reporter gene. The data show that Dox treatment produces a statistically significant induction of ADH2-lacZ expression in both log and stationary phase cells (Fig. S3B). Thus, effects of myriocin treatment are due to a reduction of SPT activity.

Activation of Snf1 requires phosphorylation of residue T210 in the activation loop, which is catalyzed by Sak1, Tos3 or Elm1 (Momcilovic & Carlson 2011). Examination of T210 in myriocin-treated or untreated cells shows that treatment enhances phosphorylation by 57% in early log phase cells (Fig. 4B). This result is consistent with higher expression of ADH2-lacZ in myriocin-treated log phase cells (Fig. 4A), higher oxygen consumption, enrichment for Snf1-controlled genes in the myriocin up-regulated gene set and GO term enrichment results (Fig. 1).

Snf1-defective cells are unable to remodel energy metabolism during the diauxic shift and lose viability faster than wild-type cells (Powers et al. 2006; De Virgilio 2012). Since myriocin treatment activates Snf1, we wondered if activation simply contributes to enhancement of viability during a CLS assay or whether it is absolutely required. Our data show that Snf1 is absolutely required in order for myriocin to increase survival because snf1Δ cells die at the same rapid rate during the diauxic shift whether treated or not treated with myriocin (Fig. 4C). The positive control shows that myriocin treatment does enhance CLS in wild-type cells as shown previously (Huang et al. 2012).

Snf1 is required for induction of peroxisomal genes and formation of peroxisomes (Simon et al. 1992). Since Peroxisome is an enriched GO term in the myriocin up-regulated gene set (Table S2), we determined if myriocin-treated cells contain more peroxisomes than untreated cells. Using the Pot1-GFP reporter protein to label peroxisomes, we find a 2.5-fold increase (ρ = 6E-26) in the number of peroxisomes in log phase wild-type cells treated with myriocin (Fig. S4). The data presented in Figs. 4 and S4 strongly support the hypothesis that myriocin treatment increases Snf1 activity in log phase cells under conditions where glucose normally represses activation.

Myriocin Treatment Enhances Autophagy

The significance of autophagy in aging and lifespan have quickly gained recognition both in yeasts (Alvers et al. 2009) and more complex organisms (Rubinsztein et al. 2011). Since Autophagy is an enhanced GO term in our myriocin up-regulated gene set (Fig. 1 and Table S2) and is known to be controlled by the four signaling pathways shown in Fig. 1 that play roles in lifespan, we determined if myriocin treatment activates autophagy in log phase cells when nutrients are abundant and autophagic flux is at a low basal level. The Atg8-GFP reporter protein enters the autophagy pathway during autophagosome formation and, when autophagosomes fuse with vacuoles, GFP is cleaved off Atg8 (Cheong & Klionsky 2008). In myriocin-treated WT cells, free GFP appears sooner and at a 2 to 3-fold higher level than in untreated cells (Fig. 5A), supporting the premise that myriocin induces autophagy. To verify that free GFP is produced by autophagy, we used atg1Δ cells that cannot execute autophagy. Free GFP does not appear in these cells, indicating that autophagy is required for production of free GFP in myriocin-treated cells (Fig. 5A).

Fig. 5. Myriocin Treatment Induces Autophagy.

(A) Effect of myriocin treatment on the induction of autophagy was quantified by measuring cleavage of GFP from the Atg8-GFP protein in wild-type DBY746 cells (upper panel) or atg1Δ cells (lower panel), each carrying pGFP-AUT7(414). Cell-free extracts were made from cells grown to the A600nm indicated below the lower panel and immunoblotted for the proteins indicated at the left of each panel. The ratio of cleaved GFP to total Atg8-GFP is indicated below the top panel. (B) CLS of DBY746 or atg1Δ cells (+/− myriocin). On day 1 (72 hrs of incubation) cells were transferred from SDC medium to water so that the value of autophagy to survival could be evaluated. Values are the average of three cultures ± S.D.

As a second way to demonstrate that down-regulating sphingolipid synthesis increases autophagic flux, we assayed cells carrying the tetO7-LCB1 gene. Treating such cells with Dox also enhances the rate of autophagic flux and flux is prevented by deleting ATG1 (Fig. S3C). Thus, both ways of reducing the rate of sphingolipid synthesis produce an increase in autophagic flux.

If extension of CLS by myriocin treatment depends on autophagy, then CLS should be reduced in atg1Δ cells. Autophagy only limits CLS in our culture medium if glucose or other nutrients are inadequate when cells reach stationary phase. To achieve such limitation, cells were transferred to water after 72 hrs of growth (Longo et al. 2012). With these culture conditions atg1Δ cells die faster than wild-type cells (Fig. 5B). Unlike snf1Δ cells, atg1Δ cells respond to myriocin treatment and live longer than untreated wild-type cells; but they do not live as long as myriocin-treated wild-type cells. Similar results were observed in Dox-treated tetO7-LCB1 cells carrying an atg1Δ mutation (Fig. S3D), indicating that this method of reducing sphingolipid synthesis produces effects that are similar to what is seen in myriocin-treated cells (Fig. 5B).

Discussion

The data presented here demonstrate the wide-ranging influence of myriocin on gene expression, signaling pathways and cellular processes (Tables S1 and S2). From this wide range we focused on understanding how myriocin can reduce signs of aging and enhance lifespan through modulation of the Snf1, TORC1, Sch9 and PKA pathways (Fig. 1, Tables S1 and S2). These pathways link nutrient availability to growth and balance growth with stress protection to govern longevity in yeasts and other organisms (Fontana et al. 2010; De Virgilio 2012; Hardie et al. 2012; Longo et al. 2012). Since these pathways work as part of a network (Zaman et al. 2009; De Virgilio 2012), myriocin is likely to modulate the network in multiple ways and we sought to establish some of these by direct experiments.

The most obvious effect of chronic low dose myriocin treatment is to reduce the level of some but not all sphingolipids, which then lowers Pkh1/2-Sch9 pathway activity and modulates downstream processes that enhance CLS, similar to what occurs in sch9Δ cells (Huang et al. 2012) (Fig. 1). Less obvious and more challenging to establish are effects of myriocin treatment on the lipid composition and function of membranes that may be important for aging and longevity. Our microarray data show that myriocin treatment reduces lipid and glycoprotein biosynthesis and functions of the endoplasmic reticulum (GO terms, Table S2), the main compartment for lipid synthesis: down-regulating these during log phase growth could affect membrane functions.

One function of the plasma membrane is to sense environmental stresses and trigger cellular responses. Stressing the plasma membrane stimulates the Rho1 GTPase to increase activity of the Pkc1-Mpk1 MAP kinase pathway, the prime controller of cell wall integrity (Levin 2011). But Rho1 has other functions. It has not been clear how stresses control TORC1, but recently Rho1 was shown to bind to and inactivate TORC1 following membrane stress (Yan et al. 2012). Myriocin treatment, by reducing the rate of sphingolipid synthesis, may induce membrane stress and activate Rho1 so that it lowers TORC1 activity. Moreover, this idea is supported by the finding that deactivation of TORC1 by membrane stress reduces Sch9 phosphorylation (Yan et al. 2012), similar to what myriocin treatment does to TORC1 phosphorylation of Sch9 C-terminal residues (Fig. 3A).

Myriocin treatment may reduce PKA activity by multiple means including through the membrane stress-Rho1-TORC1 pathway (Yan et al. 2012). Another potential route is by down-regulating the TORC1-Sch9 pathway, which is known to stimulate Mpk1 kinase activity. Activated Mpk1 increases phosphorylation of Bcy1, the inhibitory subunit of PKA, and this leads to a reduction in PKA activity (Soulard et al. 2010). Another possible avenue for myriocin to reduce PKA activity is by producing membrane stress that triggers the Rho1-Pkc1-Mpk1 pathway to phosphorylate Bcy1 (Levin 2011). Less likely, but still a possibility are mechanisms that reduce the rate of Mpk1 dephosphorylation, with one known mechanism employing the Tap42-Sit4 phosphatase (De Virgilio 2012). Further studies will be necessary to sort through these and other possibilities that do not involve membrane stress but do involve cross-talk between the PKA pathway and the TORC1-Sch9 and Snf1 pathways (Chen & Powers 2006; De Virgilio 2012).

The mechanisms for regulating Snf1/AMPK activity in yeast are not entirely understood, but it is clear that activity is low when the concentration of glucose is high in culture medium and it is also clear that activity requires phosphorylation of T210 (Ruiz et al. 2012). Enzyme activity is controlled by the Snf4/γ and the Sip1p/Sip2p/Gal83p/β regulatory subunits, which interact with the catalytic Snf1/α subunit to form a heterotrimer, and also independently of the heterotrimer by the phosphatases Reg1-Glc7 (PP1) and Sit4, which dephosphorylate T210 (Ruiz et al. 2012). One way that myriocin treatment may enhance Snf1 activity is through down-regulation of PKA, which could increase Snf1 activity in several ways (Barrett et al. 2012). These possibilities will all need to be examined in the DBY746 strain background because of strain-specific influences on Snf1 activity (Barrett et al. 2012).

Remodeling energy metabolism from the fermentative to the respiratory mode as glucose declines during the diauxic shift is a key determinant of CLS and bolstering respiration in log phase cells has a strong enhancing effect on CLS, based upon studies of tor1Δ and sch9Δ mutants and CR-treated wild-type cells (Pan & Shadel 2009; Pan et al. 2011). Mitochondrial functions including Electron Transport, Oxidative Phosphorylation and the Citric Acid Cycle are highly enriched in our myriocin up-regulated gene set and GO terms (Fig. 1 and Tables S1 and S2), consistent with myriocin enhancing respiration and increasing CLS (Huang et al. 2012). Many genes involved in respiration are regulated by the TORC1-Sch9 pathway, although the mechanisms for such control are poorly understood (Pan et al. 2011). To better understand how myriocin enhances respiration we compared the myriocin up-regulated genes to a set of mitochondrial genes regulated by Sch9 (Lavoie & Whiteway 2008). Forty-two genes are common between the two datasets (p = 1.06E-9, binomial test). Analysis of the transcription factors that regulate these common genes (YEASTRACT, direct evidence) shows that more than 70% are regulated by the Hap2/3/4/5 (HAP) complex, indicating that these genes are probably up-regulated because myriocin reduces TORC1-Sch9 pathway activity. The HAP complex belongs to an evolutionarily conserved family of transcription factors, initially identified as binding to CCAAT sequences, which play roles in cancer, neurodegenerative disorders and other diseases. The yeast HAP complex is a central regulator of mitochondrial functions and coordinates expression of nuclear and mitochondrial genes (Buschlen et al. 2003). A comparison of genes regulated by Hap2 and myriocin revealed 73 genes in common (p = 1.93E-13, binomial test). These data support the idea that myriocin enhances respiration and other mitochondrial functions to increase CLS, at least in part, by activating the HAP complex through down-regulation of the TORC1-Sch9 pathway (Fig. 1).

While data from validation experiments support an effect of myriocin on a specific signaling pathway, the data also support roles for additional pathways (Fig. 1). Data for stress protection (Figs. 2A, 2B and S2) argue that myriocin down-regulates the PKA pathway, but they also argue for down-regulation of the TORC1 and Sch9 pathways and up-regulation of Snf1 (Fig. 1) (De Virgilio 2012). Similarly, all of these pathways must be modulated by myriocin in order for autophagy to be induced. Trehalose is an important stress protectant and likely serves as a carbon source late in stationary phase (De Virgilio 2012). Its accumulation is controlled at the transcriptional level and myriocin influences this control (Trehalose GO term enrichment, p = 1.7E-04). Accumulation is also controlled at the post-translational level and myriocin may be involved. Higher accumulation in myriocin-treated cells (Fig. 2B) is consistent with several observations that trehalose promotes longer lifespan (Ocampo et al. 2012)

Glycogen normally accumulates during the diauxic shift and is used for energy generation in stationary phase (Wilson et al. 2010). Mutations or nutritional treatments that enhance glycogen accumulation generally increase CLS (Longo & Fabrizio 2002). Myriocin treatment caused an accumulation of glycogen by the end of the diauxic shift but not at later times (Fig. 2B). Glycogen accumulation is controlled at the transcriptional level primarily by the PKA pathway, but the Snf1 and TOR pathways also exert influences (Wilson et al. 2010; De Virgilio 2012). Our data show that myriocin influences accumulation at the transcriptional level (Glycogen GO term enrichment, p = 0.004) including induction of GSY2 (2.2-fold), GPH1 (2.8-fold), GLC3 (3-fold) and GDB1 (5.5-fold). Glycogen accumulation is also controlled post-translationally and myriocin may modulate some of these mechanisms.

Although we have not analyzed the role of phosphatases in mediating effects of myriocin on cells, they are likely to be important and we discuss a few of the many possibilities. The Tap42-Sit4 phosphatase binds to active TORC1 and this prevents substrate dephosphorylation. But Tap42-Sit4 is released upon TORC1 down-regulation and can act on substrates such as Mpk1 (De Virgilio 2012). The ceramide-activated Sit4-containing phosphatase impinges on the cell cycle (Nickels & Broach 1996) and this may play a role in the reduced growth rate of myriocin-treated cells (Huang et al. 2012). Like myriocin-treated cells, sit4Δ cells have an increased CLS (Barbosa et al. 2011). Myriocin treatment may lower ceramide levels and reduce Sit4-phosphatase activity (at least in stationary phase) thereby increasing lifespan. Sit4 and Reg1-Glc7 also regulate Snf1 activity by dephosphorylating T210 while Reg1-Glc7 regulates glycogen accumulation and many other processes (Ruiz et al. 2012), some of which may be affected by myriocin treatment.

The idea of promoting a longer and healthier life by down-regulating TOR has received much attention (Kapahi et al. 2010; Bjedov & Partridge 2011), particularly since 2009 when it was found to enhance lifespan in mice (Harrison et al. 2009). Rapamycin and analogs are being tested in more than 1000 clinical trials, either alone or in combination with other drugs, to treat cancers and other diseases (http://clinicaltrials.gov). Our studies along with studies in mammals, suggest that myriocin or related compounds may be as potentially useful as rapamycin for chronic drug therapy to lower the incidence of age-related diseases. Research in rodents has shown, for example, that low doses of myriocin have potential for treating diabetes, cardiomyopathy and atherosclerosis (Summers 2010). Although working by similar mechanisms, myriocin, rapamycin, and other strategies to reduce aging may each have unique effects on cellular networks so that a combination of strategies may provide greater health benefits than any single strategy.

Experimental procedures

Yeast strains and plasmids are listed in Supplemental Information. CLS and stress resistance assays used cells grown in SDC medium buffered to pH 4.5 with 200 mM succinate or in the same medium buffered to pH 6.0 (where indicated) (Huang et al. 2012). CLS was measured as previously described (Huang et al. 2012). Drug treatments were performed in medium containing a total of 0.3% ethanol with or without drug. This was done by first adding a calculated volume of 95% ethanol to the medium followed by diluting a stock solution of drug (200 µg myriocin/ml or 100 µg rapamycin/ml, both in 95% EtOH and both from Sigma) to give a concentration of 400 ng/ml. Statistical significance was determined by using the two-tailed Student’s t-test or, where indicated, the Chi Square or binomial tests.

Cells for stress resistance assays were grown in SDC medium for the time indicated in figure legends, diluted to an A600nm of 1.0 in K-phosphate buffer (pH 6.0), treated with hydrogen peroxide or menadione for 30 min (log phase) or 60 min (stationary phase) at room temperature with mixing, serially diluted (10-fold), spotted onto YPD plates, and incubated at 30°C for 2–3 days. For heat stress resistance, cells were serially diluted (10-fold dilution starting with an A600nm = 1), spotted onto YPD plates, and incubated at either 55°C (heat-shocked) or 30°C (control) for 45–180 min. Plates were incubated for 2–3 days at 30°C. β-galactosidase activity units are expressed as nmoles o-nitrophenol hydrolyzed/min/ml of cells (Untreated log phase cells = 51 µm3, myriocin-treated = 45 µm3, untreated CLS D1 = 82 µm3 and myriocin-treated CLS D1 = 59 µm3). Peroxisomes were examined in cells carrying Pot1-GFP using a Nikon A1 spinning disk confocal microscope (TE2000) with a 60X oil objective and 4X digital zoom. Procedures for extract preparation, immunoblotting and immunoprecipitations are described in detail in the Supplemental Information along with information about the antibodies used in each assay.

For microarray analyses, three cultures of DBY746 cells were grown from 0.002 to 2 A600 units/ml in SDC medium (pH 6) with and without myriocin (300ng/ml) as described previously (Huang et al. 2012). RNA was isolated (RNeasy mini kit, Qiagen) and then processed for microarray analyses by the University of Kentucky Microarray Core Facility using GeneChip Yeast Genome 2.0 Arrays (Affymetrix, Santa Clara, CA). Raw data files (CEL files) were processed by using the Partek® Genomics Suite™ (Partek Incorporated., USA) (2010). Background correction was performed with the GC-RMA function followed by log 2 transformations (base 2) and median polish summarization of the raw data. Differentially expressed genes were detected by using one-way ANOVA analysis. The false discovery rate (FDR) was determined by the method of Benjamini-Hochberg. The DAVID web-based software was used for analysis of GO term enrichment and clustering (Huang et al. 2009).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank Drs. B. Andre, M. Carlson, J. Goodman, M. Hall, P. Herman, Y. Jiang, D. Klionsky, R. Loewith, and T. Young for reagents and suggestions, Dr. C. Moncman for assistance with microscopy and Dr. T. Young for comments on the manuscript. Work by J.L. is for partial fulfillment of the Ph.D. requirements of Sichuan University and he is funded by the China Scholarship Council. R.D. is funded by grant AG024277 from the NIH. K. L. is funded by NSFC (30671181/C0603). Microscopy facilities were supported in part by NIH Grant Number P20GM103486 from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences.

Footnotes

Author contributions

Dr. Dickson and Jun Liu designed the study. Jun Liu performed most experiments but a few were done by Dr. Huang and Mr. Withers. Dr. Blalock oversaw the microarray analyses and statistical tests. All authors contributed reagents and suggestions to the studies. Dr. Dickson wrote the text and the other authors contributed to the final text presentation.

Supplemental Information

Additional supporting information may be found in the online version of this article:

Fig. S1. Myriocin treatment enhances CLS in medium buffered to pH 6.

Fig. S2. Myriocin treatment enhances heat and oxidative stress resistance.

Fig. S3. Down-regulation of LCB1 expression produces cellular effects that mirror those produced by myriocin treatment.

Fig. S4. Myriocin treatment induces peroxisome proliferation.

Table S1. Myriocin-responsive genes.

Table S2. GO terms enriched in the myriocin-responsive genes.

Table S3. Transcription factors predicted to regulate expression of myriocin-responsive genes.

References

- Alvers AL, Fishwick LK, Wood MS, Hu D, Chung HS, Dunn WA, Jr, Aris JP. Autophagy and amino acid homeostasis are required for chronological longevity in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Aging Cell. 2009;8:353–369. doi: 10.1111/j.1474-9726.2009.00469.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbosa AD, Osorio H, Sims KJ, Almeida T, Alves M, Bielawski J, Amorim MA, Moradas-Ferreira P, Hannun YA, Costa V. Role for Sit4p-dependent mitochondrial dysfunction in mediating the shortened chronological lifespan and oxidative stress sensitivity of Isc1p-deficient cells. Mol. Microbiol. 2011;81:515–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2011.07714.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett L, Orlova M, Maziarz M, Kuchin S. Protein kinase A contributes to the negative control of Snf1 protein kinase in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot. Cell. 2012;11:119–128. doi: 10.1128/EC.05061-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beck T, Hall MN. The TOR signalling pathway controls nuclear localization of nutrient- regulated transcription factors. Nature. 1999;402:689–692. doi: 10.1038/45287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bjedov I, Partridge L. A longer and healthier life with TOR down-regulation: genetics and drugs. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2011;39:460–465. doi: 10.1042/BST0390460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burtner CR, Murakami CJ, Kennedy BK, Kaeberlein M. A molecular mechanism of chronological aging in yeast. Cell Cycle. 2009;8:1256–1270. doi: 10.4161/cc.8.8.8287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buschlen S, Amillet JM, Guiard B, Fournier A, Marcireau C, Bolotin-Fukuhara M. The S. Cerevisiae HAP complex, a key regulator of mitochondrial function, coordinates nuclear and mitochondrial gene expression. Comp Funct Genomics. 2003;4:37–46. doi: 10.1002/cfg.254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen JC, Powers T. Coordinate regulation of multiple and distinct biosynthetic pathways by TOR and PKA kinases in S. cerevisiae. Curr. Genet. 2006;49:281–293. doi: 10.1007/s00294-005-0055-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheong H, Klionsky DJ. Biochemical methods to monitor autophagy-related processes in yeast. Meth. Enzymol. 2008;451:1–26. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(08)03201-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Virgilio C. The essence of yeast quiescence. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2012;36:306–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00287.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrizio P, Hoon S, Shamalnasab M, Galbani A, Wei M, Giaever G, Nislow C, Longo VD. Genome-wide screen in Saccharomyces cerevisiae identifies vacuolar protein sorting, autophagy, biosynthetic, and tRNA methylation genes involved in life span regulation. PLoS Genet. 2010;6:e1001024. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1001024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabrizio P, Pozza F, Pletcher SD, Gendron CM, Longo VD. Regulation of longevity and stress resistance by Sch9 in yeast. Science. 2001;292:288–290. doi: 10.1126/science.1059497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fontana L, Partridge L, Longo VD. Extending healthy life span--from yeast to humans. Science. 2010;328:321–326. doi: 10.1126/science.1172539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasch AP, Spellman PT, Kao CM, Carmel-Harel O, Eisen MB, Storz G, Botstein D, Brown PO. Genomic expression programs in the response of yeast cells to environmental changes. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2000;11:4241–4257. doi: 10.1091/mbc.11.12.4241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardie DG, Ross FA, Hawley SA. AMPK: a nutrient and energy sensor that maintains energy homeostasis. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2012;13:251–262. doi: 10.1038/nrm3311. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harrison DE, Strong R, Sharp ZD, Nelson JF, Astle CM, Flurkey K, Nadon NL, Wilkinson JE, Frenkel K, Carter CS, Pahor M, Javors MA, Fernandez E, Miller RA. Rapamycin fed late in life extends lifespan in genetically heterogeneous mice. Nature. 2009;460:392–395. doi: 10.1038/nature08221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nature Protocols. 2009;4:44–57. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Liu J, Dickson RC. Down-regulating sphingolipid synthesis increases yeast lifespan. PLoS Genet. 2012;8:e1002493. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1002493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huber A, French SL, Tekotte H, Yerlikaya S, Stahl M, Perepelkina MP, Tyers M, Rougemont J, Beyer AL, Loewith R. Sch9 regulates ribosome biogenesis via Stb3, Dot6 and Tod6 and the histone deacetylase complex RPD3L. EBMO J. 2011;30:3052–3064. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2011.221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapahi P, Chen D, Rogers AN, Katewa SD, Li PW, Thomas EL, Kockel L. With TOR, less is more: a key role for the conserved nutrient-sensing TOR pathway in aging. Cell Metab. 2010;11:453–465. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2010.05.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lavoie H, Whiteway M. Increased respiration in the sch9Delta mutant is required for increasing chronological life span but not replicative life span. Eukaryot. Cell. 2008;7:1127–1135. doi: 10.1128/EC.00330-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee YL, Lee CK. Transcriptional response according to strength of calorie restriction in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol Cells. 2008;26:299–307. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levin DE. Regulation of cell wall biogenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae: the cell wall integrity signaling pathway. Genetics. 2011;189:1145–1175. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.128264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Loewith R, Hall MN. Target of rapamycin (TOR) in nutrient signaling and growth control. Genetics. 2011;189:1177–1201. doi: 10.1534/genetics.111.133363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo VD, Fabrizio P. Regulation of longevity and stress resistance: a molecular strategy conserved from yeast to humans? Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2002;59:903–908. doi: 10.1007/s00018-002-8477-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longo VD, Shadel GS, Kaeberlein M, Kennedy B. Replicative and Chronological Aging in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Cell Metab. 2012;16:18–31. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.06.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marini AM, Soussi-Boudekou S, Vissers S, Andre B. A family of ammonium transporters in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell Bio. 1997;17:4282–4293. doi: 10.1128/mcb.17.8.4282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Momcilovic M, Carlson M. Alterations at dispersed sites cause phosphorylation and activation of SNF1 protein kinase during growth on high glucose. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:23544–23551. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.244111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickels JT, Broach JR. A ceramide-activated protein phosphatase mediates ceramide-induced G1 arrest of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Genes Dev. 1996;10:382–394. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.4.382. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ocampo A, Liu J, Schroeder EA, Shadel GS, Barrientos A. Mitochondrial respiratory thresholds regulate yeast chronological life span and its extension by caloric restriction. Cell Metab. 2012;16:55–67. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2012.05.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y, Schroeder EA, Ocampo A, Barrientos A, Shadel GS. Regulation of yeast chronological life span by TORC1 via adaptive mitochondrial ROS signaling. Cell Metab. 2011;13:668–678. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2011.03.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pan Y, Shadel GS. Extension of chronological life span by reduced TOR signaling requires down-regulation of Sch9p and involves increased mitochondrial OXPHOS complex density. Aging. 2009;1:131–145. doi: 10.18632/aging.100016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Powers RW, 3rd, Kaeberlein M, Caldwell SD, Kennedy BK, Fields S. Extension of chronological life span in yeast by decreased TOR pathway signaling. Genes Dev. 2006;20:174–184. doi: 10.1101/gad.1381406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinsztein DC, Marino G, Kroemer G. Autophagy and aging. Cell. 2011;146:682–695. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz A, Liu Y, Xu X, Carlson M. Heterotrimer-independent regulation of activation-loop phosphorylation of Snf1 protein kinase involves two protein phosphatases. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2012;109:8652–8657. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1206280109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selman C, Tullet JM, Wieser D, Irvine E, Lingard SJ, Choudhury AI, Claret M, Al-Qassab H, Carmignac D, Ramadani F, Woods A, Robinson IC, Schuster E, Batterham RL, Kozma SC, Thomas G, Carling D, Okkenhaug K, Thornton JM, Partridge L, Gems D, Withers DJ. Ribosomal protein S6 kinase 1 signaling regulates mammalian life span. Science. 2009;326:140–144. doi: 10.1126/science.1177221. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simon M, Binder M, Adam G, Hartig A, Ruis H. Control of peroxisome proliferation in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by ADR1, SNF1, (CAT1, CCR1) and SNF4 (CAT3) Yeast. 1992;8:303–309. doi: 10.1002/yea.320080407. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soulard A, Cremonesi A, Moes S, Schutz F, Jeno P, Hall MN. The rapamycin-sensitive phosphoproteome reveals that TOR controls protein kinase A toward some but not all substrates. Mol. Biol. Cell. 2010;21:3475–3486. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E10-03-0182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stephan JS, Yeh YY, Ramachandran V, Deminoff SJ, Herman PK. The Tor and PKA signaling pathways independently target the Atg1/Atg13 protein kinase complex to control autophagy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2009;106:17049–17054. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903316106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Summers SA. Sphingolipids and insulin resistance: the five Ws. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2010;21:128–135. doi: 10.1097/MOL.0b013e3283373b66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Urban J, Soulard A, Huber A, Lippman S, Mukhopadhyay D, Deloche O, Wanke V, Anrather D, Ammerer G, Riezman H, Broach JR, De Virgilio C, Hall MN, Loewith R. Sch9 is a major target of TORC1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Mol. Cell. 2007;26:663–674. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vyas VK, Berkey CD, Miyao T, Carlson M. Repressors Nrg1 and Nrg2 regulate a set of stress-responsive genes in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Eukaryot. Cell. 2005;4:1882–1891. doi: 10.1128/EC.4.11.1882-1891.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson WA, Roach PJ, Montero M, Baroja-Fernandez E, Munoz FJ, Eydallin G, Viale AM, Pozueta-Romero J. Regulation of glycogen metabolism in yeast and bacteria. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2010;34:952–985. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2010.00220.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan G, Lai Y, Jiang Y. The TOR complex 1 is a direct target of Rho1 GTPase. Mol. Cell. 2012;45:743–753. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.01.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young ET, Dombek KM, Tachibana C, Ideker T. Multiple pathways are co-regulated by the protein kinase Snf1 and the transcription factors Adr1 and Cat8. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:26146–26158. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M301981200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zaman S, Lippman SI, Schneper L, Slonim N, Broach JR. Glucose regulates transcription in yeast through a network of signaling pathways. Mol. Syst. Biol. 2009;5:245. doi: 10.1038/msb.2009.2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.