Abstract

Objectives

Most existing tools for measuring health literacy (HL) focus on reading comprehension and numeracy in English speakers. The aim of this study was to develop a generic HL measure for Japanese adults.

Methods

A questionnaire survey was conducted among participants in multiphasic health examinations at a Japanese healthcare facility. HL was measured using the 14-item health literacy scale (HLS-14) that was adapted from the HL scale specific to diabetic patients developed by Ishikawa and colleagues. The 14 items consist of five items for functional HL, five items for communicative HL, and four items for critical HL. The reliability and validity of the HLS-14 were assessed among 1,507 eligible respondents aged 30–69 years.

Results

Explanatory factor analysis produced a three-factor solution that was very similar to the original HL scale. Cronbach’s alpha indicated satisfactory internal consistency of the functional, communicative, and critical HL scores (0.83, 0.85, and 0.76, respectively). There were no floor or ceiling effects in each HL score. Confirmatory factor analysis revealed an acceptable fit of the three-factor model (comparative fit index = 0.912, normed fit index = 0.905, root mean square error of approximation = 0.082). When the two groups with a total HL score above and below the median (50), respectively, were compared, those who could obtain medication information satisfactorily and those who wanted to participate in making medication decisions were more frequently observed in the group with the higher score.

Conclusions

The HLS-14 demonstrated adequate reliability and validity as a generic HL measure for Japanese adults. This scale can be utilized for measuring functional, communicative, and critical HL in the clinical and public health contexts.

Keywords: Health literacy, Adult, Japan, Questionnaire, Validity

Introduction

Health information helps people to understand aspects of their own health and engage in self-management. The recent developments in information technology have provided the general public with free access to a wide range of health information. However, the efficacious use of this information requires that individuals are health literate, i.e., that they possess adequate cognitive and social skills underlying the motivation and ability of individuals to gain access to, understand, and use information in ways which promote and maintain good health [1]. Low literacy has negative impacts on various patient behaviors and health outcomes [2–4], and health literacy (HL) is now recognized as a key factor in terms of both clinical “risk” and personal “assets” [5].

A number of tools for measuring HL have been developed and used in research studies. Most of these were designed to assess reading comprehension and numeracy in English speakers [6, 7]. The concept of HL has recently begun to attract notice in Japan, where nearly 100 % of the population over the age of 15 can read and write the Japanese language. There have been some attempts to develop self-rated scales for measuring HL in Japanese speakers [8–12]. One of these, developed by Ishikawa and colleagues [8], has the advantage of dealing with all three levels of HL: (1) functional literacy—sufficient basic skills in reading and writing to be able to function effectively in everyday situations, a definition which is broadly compatible with the narrow definition of HL; (2) communicative literacy—more advanced skills to participate actively in everyday activities, to extract information and derive meaning from different forms of communication, and to apply new information to changing circumstances; (3) critical literacy—more advanced skills to analyze information critically and to use this information to exert greater control over life events and situations [13]. Unfortunately, the HL scale is not generic, rather it is specific to diabetic patients. In order to develop a generic HL measure for Japanese adults, we adapted the HL scale specific to diabetic patients developed by Ishikawa and colleagues [8] for use with various people. We assessed the reliability and validity of our HL scale among middle-aged Japanese men and women.

Methods

Subjects

A questionnaire survey was conducted between September and December 2010 at the Japanese Red Cross Kumamoto Health Care Center. About 2,000 participants in multiphasic health examinations were asked to fill out a questionnaire anonymously. Details of the questionnaire survey have been described elsewhere [14]. The study protocol was approved by the ethics committees of the Japanese Red Cross Kumamoto Healthcare Center and Daito Bunka University, and the study was conducted in accordance with the Guidelines for Epidemiological Studies by the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare and the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology.

A total of 1,978 participants who agreed to participate in the questionnaire survey were given the questionnaire to complete then and there. After the exclusion of those who did not answer age or gender questions (N = 105) and those who (had) worked in the medical and pharmaceutical fields (N = 166), 1,707 subjects (1,056 men and 651 women) remained. Of these, those aged less than 30 years (N = 4) and those aged ≥70 years (N = 81) were excluded because there was an insufficient number of subjects available in these age categories. Among the remaining 1,622 subjects (998 men and 624 women) aged 30–69 years, the 1,507 subjects (946 men and 561 women) who completely filled out the HL scale were included in this study.

Measures

The questionnaire consisted of three parts. In the first part, the participants were asked about their experiences and perspectives on seeking medicine information and making medication decisions. In the second part, their HL was measured using the 14-item health literacy scale (HLS-14) that was adapted from the HL scale specific to diabetes patients developed by Ishikawa and colleagues [8]. In the third part, their quality of life was measured using the SF-8 Japanese version. The answers to the questions in the second part, together with those in the first part, were analyzed in this study.

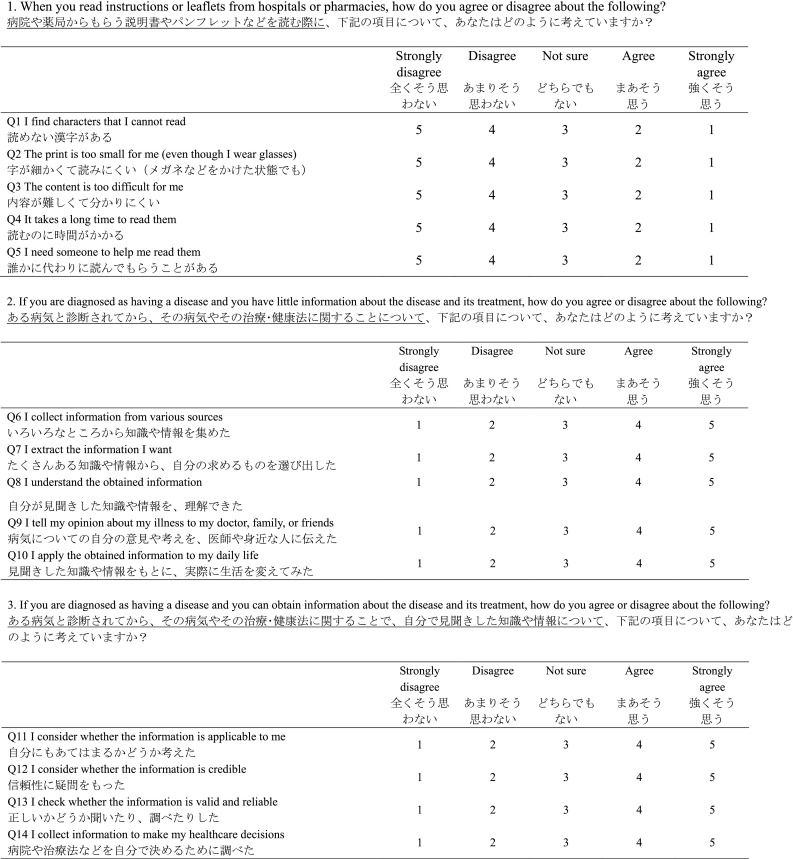

The HLS-14 is shown in the “Appendix”. It contains five items pertaining to functional HL, five items pertaining to communicative HL, and four items pertaining to critical HL. The 14 items are the same as those on the original HL scale [8], while the interrogative sentences have been modified so as not to be specific to diabetic patients. Response options have been changed from a 4-point scale that indicates how often the item happens to them (‘never’ to ‘often’) [8] to a 5-point scale that indicates how much the respondent agrees or disagrees with the item (‘strongly disagree’ to ‘strongly agree’) [9]. The scores on the items were summed up for each respondent to give the total HL score, as well as functional, communicative, and critical HL scores. Higher scores indicate a better HL.

Statistical analysis

Reliability

Explanatory factor analysis with promax rotation was performed to determine the factor structure of the HLS-14. Factor loadings of ≥0.4 were considered to be appropriate. Internal consistency was assessed by Cronbach’s alpha, where a value of ≥0.7 was considered satisfactory [15, 16]. The percentages of subjects with the lowest and highest scores were calculated to identify floor and ceiling effects. If the percentage was >15 %, the effect was considered to be present [16].

Validity

Confirmatory factor analysis was performed to assess the construct validity of the HLS-14. Model fitness was assessed by the comparative fit index (CFI), normed fit index (NFI), and root mean square error of approximation (RMSEA). For CFI and NFI, a value closer to 1 indicates better fit, and for RMSEA, a value of <0.10 is considered to be acceptable [17].

To examine whether the HL scores were associated with experiences and perspectives on seeking medicine information and making medication decisions, the study subjects were divided into two groups according to a total HL score of above or below the median (50). The percentages of affirmative answers were compared between the higher and lower scoring groups using the chi-square test. Age and gender differences in the HL scores were examined using two-way analysis of variance (ANOVA).

All statistical analyses except for the confirmatory factor analysis were performed using SAS ver. 9.2 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Confirmatory factor analysis was performed using the IBM SPSS Amos ver. 20.0 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Significant levels were set at p < 0.05.

Results

Subjects

Of the 1,622 nonmedical respondents aged 30–69 years, 1,507 (92.9 %) completely filled out the HLS-14 questionnaire. The response rate for each item ranged from 96.4 % (Q12: I consider whether the information is credible) to 99.5 % (Q2: The print is too small for me). Table 1 shows the characteristics of the study subjects.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the study subjects

| Total, N (%) | Men, N (%) | Women, N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 1,507 (100.0) | 946 (68.2) | 561 (37.2) |

| Age of subjects (years) | |||

| 30–39 | 195 (12.9) | 117 (12.4) | 78 (13.9) |

| 40–49 | 461 (30.6) | 293 (31.0) | 168 (29.9) |

| 50–59 | 533 (35.4) | 339 (35.8) | 194 (34.6) |

| 60–69 | 318 (21.1) | 197 (20.8) | 121 (21.6) |

| Medication | |||

| Yes | 469 (31.1) | 302 (31.9) | 167 (29.8) |

| No | 1,038 (68.9) | 644 (68.1) | 394 (70.2) |

Reliability

The explanatory factor analysis revealed a factor structure that was very similar to that of the original HL scale [8]. Table 2 shows the factor structure of the HLS-14. The initial factor solution indicated three factors with eigenvalues of 3.86, 2.53, and 0.71, respectively, which jointly accounted for 109 % of the total variance. The promax rotation indicated that all five items for functional HL loaded on the second factor and that all five items for communicative HL loaded on the first factor. Among the four items for critical HL, three loaded on the third factor; the remaining item ‘Q11: I consider whether the information is applicable to me’ loaded mainly on the first factor, with a factor loading of <0.4 on the third factor.

Table 2.

Factor structure of the 14-item health literacy scale (HLS-14)

| Mean | SD | Factor loadings | Communality | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Factor 1 | Factor 2 | Factor 3 | |||||

| Functional health literacy | |||||||

| Q1 | Find characters that I cannot read | 3.8 | 0.9 | 0.06 | 0.69 | −0.02 | 0.49 |

| Q2 | Feel that the print is too small for me to read | 3.7 | 1.0 | −0.05 | 0.72 | 0.05 | 0.51 |

| Q3 | Feel that the content is too difficult for me to understand | 3.5 | 1.0 | −0.02 | 0.87 | −0.01 | 0.76 |

| Q4 | Feel that it takes a long time to read them | 3.6 | 1.0 | −0.04 | 0.78 | −0.01 | 0.61 |

| Q5 | Need someone to help me read them | 4.5 | 0.8 | 0.07 | 0.47 | −0.02 | 0.23 |

| Communicative health literacy | |||||||

| Q6 | Collect information from various sources | 3.9 | 1.0 | 0.72 | −0.05 | 0.07 | 0.57 |

| Q7 | Extract the information I want | 3.6 | 0.9 | 0.80 | −0.02 | 0.01 | 0.65 |

| Q8 | Understand the obtained information | 3.5 | 0.8 | 0.83 | 0.09 | −0.14 | 0.61 |

| Q9 | Communicate my opinion about my illness | 3.4 | 0.9 | 0.62 | −0.02 | 0.00 | 0.38 |

| Q10 | Apply the obtained information to my daily life | 3.4 | 0.9 | 0.65 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 0.47 |

| Critical health literacy | |||||||

| Q11 | Consider whether the information is applicable to me | 3.8 | 0.8 | 0.45 | 0.00 | 0.28 | 0.41 |

| Q12 | Consider whether the information is credible | 2.9 | 0.8 | −0.08 | −0.08 | 0.58 | 0.31 |

| Q13 | Check whether the information is valid and reliable | 3.4 | 0.9 | 0.09 | 0.03 | 0.81 | 0.75 |

| Q14 | Collect information to make my healthcare decisions | 3.2 | 1.0 | 0.14 | 0.05 | 0.67 | 0.57 |

Underlined values indicate the greatest factor loadings

SD standard deviation

Table 3 shows the internal consistency and floor and ceiling effects of the HLS-14. The internal consistency of each HL score, as indicated by Cronbach’s alpha, was satisfactory. The total correlations for each set of items ranged from 0.44 to 0.76 for the functional HL score, from 0.58 to 0.72 for the communicative HL score, and from 0.45 to 0.71 for the critical HL score. When the item ‘Q11: I consider whether the information is applicable to me’ was removed from the critical HL items, Cronbach’s alpha of the critical HL score, as well as that of the total HL score, decreased by 0.01–0.02. Similar to the original HL scale [8], we decided to count this item among the critical HL items. There were no floor or ceiling effects in each HL score.

Table 3.

Internal consistency and floor and ceiling effects of the 14-item health literacy scale (HLS-14)

| Mean ± SD | Cronbach’s alpha | Lowest score, N (%) | Highest score, N (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total health literacy score, Q1–Q14 | 50.3 ± 6.8 | 0.81 | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.1) |

| Functional health literacy score, Q1–Q5 | 19.1 ± 3.6 | 0.83 | 1 (0.1) | 120 (8.0) |

| Communicative health literacy score, Q6–Q10 | 17.8 ± 3.6 | 0.85 | 10 (0.7) | 41 (2.7) |

| Critical health literacy score, Q11–Q14 | 13.4 ± 2.7 | 0.76 | 12 (0.8) | 16 (1.1) |

Validity

The confirmatory factor analysis revealed an acceptable fit of the three-factor model, with an CFI = 0.912, NFI = 0.905, and RMSEA = 0.082 (90 % confidence interval 0.078–0.088). Figure 1 shows the path diagrams of the confirmatory factor model. In the preliminary analysis, no significant correlation was found between the functional HL score and the critical HL score (γ = 0.00, p = 0.90). Therefore, the correlation between functional HL and critical HL was not incorporated into the confirmatory factor model. Standardized factor loadings ranged from 0.46 (Q5: I need someone to help me read them) to 0.89 (Q3: The content is too difficult for me). There was a positive correlation between the communicative HL score and the critical HL score, while the functional HL score was not correlated with the communicative HL score.

Fig. 1.

Path diagrams of the confirmatory factor model. Rectangles Observed variables (items), ellipses latent variables (factors), values on the single-headed arrows standardized factor loadings, values on the double-headed arrows correlation coefficients. Model fitness: comparative fit index = 0.912, normed fit index = 0.905, root mean square error of approximation = 0.082 (90 % confidence interval 0.078–0.088)

Table 4 shows the comparison between the higher and lower scoring groups in seeking medicine information and making medication decisions. Compared with the lower scoring group, the higher scoring group tended to use more than one information source for seeking medicine information. Those who could obtain all the information they want and those who had never seen unknown medical words at hospitals or pharmacies were more frequently observed in the higher scoring group. Those who wanted their views taken into account in medication decisions and those who preferred to choose between various alternative medicines accounted for 66 and 75 % of subjects, respectively, in the higher scoring group and 50 and 58 %, respectively, of subjects in the lower scoring group.

Table 4.

Comparison between the higher and lower scoring groups in seeking medicine information and making medication decisions

| Higher score, N (%) | Lower score, N (%) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Number of subjects | 764 (50.7) | 743 (49.3) | |

| Number of information sources used by subjectsa | |||

| 1 | 265 (34.8) | 292 (39.5) | 0.003 |

| 2 | 248 (32.5) | 265 (35.9) | |

| 3+ | 249 (32.7) | 182 (24.6) | |

| Unknown | 2 | 4 | |

| I can obtain all the information I want | |||

| Yes | 502 (67.1) | 417 (57.1) | <0.001 |

| No | 246 (32.9) | 313 (42.9) | |

| Unknown | 16 | 13 | |

| I have seen unknown medical words at hospitals or pharmacies | |||

| Yes | 411 (55.0) | 418 (58.5) | <0.001 |

| No | 336 (45.0) | 296 (41.5) | |

| Unknown | 17 | 29 | |

| I want my views taken into account in medication decisions | |||

| No | 504 (66.3) | 367 (49.7) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 256 (33.7) | 372 (50.3) | |

| Unknown | 4 | 4 | |

| I prefer to choose between various alternative medicines | |||

| No | 571 (75.0) | 432 (58.3) | <0.001 |

| Yes | 190 (25.0) | 309 (41.7) | |

| Unknown | 3 | 2 | |

The study subjects were divided into two groups according to a total health literacy score of above or below the median (50)

aInformation sources were (1) physicians, (2) pharmacists, (3) friends/relatives, (4) books/dictionaries, (5) Internet, (6) drugstores, (7) pharmaceutical makers, and (8) public agencies

Table 5 shows the age and gender differences in the HL scores. Two-way ANOVA revealed significant age and gender differences in the total, functional, communicative, and critical HL scores. When the comparison test was performed by age group, women had significantly higher scores than men in all age groups except for the age groups 50–59 and 60–69 years for the functional HL score.

Table 5.

Age and gender differences in the health literacy scores

| 30–39 years | 40–49 years | 50–59 years | 60–69 years | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Men | Women | p | Men | Women | p | Men | Women | p | Men | Women | p | |

| Total health literacy score | ||||||||||||

| Mean | 49.9 | 53.5 | *** | 50.4 | 52.7 | *** | 48.9 | 50.6 | ** | 48.8 | 51.3 | ** |

| SD | 7.0 | 5.6 | 6.4 | 6.1 | 6.5 | 7.2 | 7.2 | 7.1 | ||||

| Functional health literacy score | ||||||||||||

| Mean | 19.3 | 20.5 | ** | 19.1 | 19.8 | * | 18.4 | 18.6 | 19.1 | 19.4 | ||

| SD | 3.4 | 3.2 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.5 | ||||

| Communicative health literacy score | ||||||||||||

| Mean | 17.2 | 18.6 | * | 17.9 | 18.7 | * | 17.5 | 18.2 | * | 17.1 | 18.3 | ** |

| SD | 4.0 | 2.8 | 3.3 | 3.4 | 3.3 | 3.8 | 3.8 | 3.9 | ||||

| Critical health literacy score | ||||||||||||

| Mean | 13.4 | 14.5 | ** | 13.4 | 14.2 | ** | 13.0 | 13.7 | ** | 12.6 | 13.6 | ** |

| SD | 2.8 | 2.1 | 2.5 | 2.5 | 2.6 | 2.8 | 2.9 | 3.1 | ||||

Two-way analysis of variance revealed significant age and gender differences in the total, functional, communicative, and critical health literacy scores

*** p < 0.001, ** p < 0.01, * p < 0.05 between men and women

Discussion

It is essential to measure HL in target populations to offer health information according to their HL level. We propose a generic HL measure for Japanese adults that is based on the HL scale specific to diabetic patients developed by Ishikawa and colleagues [8]. Most existing tools for measuring HL focus on reading comprehension and numeracy (i.e., functional HL) in English speakers [6, 7]. To our knowledge, our HL scale (the HLS-14) is a unique tool that aims to measure functional, communicative, and critical HL in both the clinical and public health contexts which has been proven to have adequate reliability and validity among middle-aged Japanese men and women.

Explanatory factor analysis produced a three-factor solution and confirmatory factor analysis revealed an acceptable fit of the three-factor model. The internal consistency of each HL score was satisfactory. These results confirm that the 14 items on the HLS-14 represent functional, communicative, and critical HL as originally designed. In the explanatory factor analysis, the item ‘Q11: I consider whether the information is applicable to me’ loaded both on the first factor, indicating communicative HL, and on the third factor, indicating critical HL. A similar result was obtained for the original HL scale [8]. This item is counted among the critical HL items, but it may measure advanced skills that combine communicative HL and critical HL. Overall, the HLS-14 has a successful structure for measuring HL at three different levels (i.e., functional, communicative, and critical HL) [13].

The mean score on each item tended to be higher for the functional HL items than for the communicative HL items and the critical HL items (Table 2). Functional HL is defined as basic skills, while communicative HL and critical HL are defined as advanced skills [13]. The higher scores on functional HL items are consistent with the definitions of three levels of HL. As shown in the confirmatory factor model, the functional HL score was not correlated with the communicative HL score or the critical HL score (Fig. 1). This result suggests that the measurement of functional HL cannot substitute for the measurement of communicative HL and critical HL, although communicative HL and critical HL must be based on functional HL. Due to a lack of tools for measuring communicative HL and critical HL, epidemiological data on these advanced skills are scarce. The use of HLS-14 may contribute to promoting a better understanding of advanced skills beyond reading comprehension and numeracy.

The item ‘Q5: I need someone to help me read them’ had the minimum factor loading among the 14 items in the confirmatory factor model. The score on this item showed a skewed distribution, with a mean of 4.5 on a 5-point scale, whereas no ceiling effect was found in the functional HL score. The study subjects were recruited from participants in multiphasic health examinations, who may be healthier and less impaired in reading and writing skills than clinical patients. The skewed distribution of scores may also be due partly to the study setting. This item is commonly used as a single-item screener to identify patients with inadequate HL [6, 7]. However, according to our results, caution should be taken when applying the single-item screener to relatively healthy people in a public health context or using it in a well-educated population like the Japanese.

The HLS-14 is relatively a short questionnaire and easy to use. Because of the self-administered character of the questionnaire (interviews are not required), it easy to use in a large-scale survey in both the clinical and public health contexts. The response rate for each item ranged from 96.4 to 99.5 %, indicating that the HLS-14 was well accepted. The <100 % response rate may be due to the voluntary response character of the questionnaire survey. Another possible explanation is that people without experience of suffering from a disease may have found some items difficult to answer. A qualitative interview survey among Dutch patients suggested the need for revisions in the Dutch version of the HL scale [18]. Similarly, a qualitative assessment of the questionnaire may help improve the questionnaire to achieve a 100 % response rate.

When the subjects were categorized into two groups based on the total HL score of above and below the median (50), those who could obtain medication information satisfactorily and those who wanted to participate in making medication decisions were more frequently observed in the higher scoring group. This result suggests the possibility that the use of HLS-14 may help identify individuals with a potential ability to share in decision-making [19]. The HL scores showed significant differences between age groups, but there was no age-related trend between age 30 and 69 years. Women had significantly higher scores than men independently of age. It is known that women are more sensitive to discomfort and more inclined to report discomforts to family, friends, and professionals, whereas men are more reluctant to seek help [20–22]. A better awareness of symptoms and more willingness to seek help in women may increase their access to health information, and subsequently, may contribute to the development of HL. Further studies using the HLS-14 should be conducted to confirm the impact of HL on health behavior and to identify influential factors in the development of HL.

This study provides evidence for the reliability and validity of the HLS-14; however, it has a number of potential limitations. First, popular HL measures, such as the Rapid Estimate of Adult Literacy in Medicine (REALM) and the Test of Functional Health Literacy in Adults (TOFHLA), are unavailable in Japanese. We therefore could not examine the correlations between our HL scale and these measures, although this study revealed that the HL scores were significantly associated with experiences and perspectives on seeking medicine information and making medication decisions. Second, the study subjects were recruited from participants in multiphasic health examinations, who may be relatively healthy people with an interest in health issues. Moreover, because of the voluntary response on the questionnaire survey, people who found it difficult to fill in the questionnaire may have been not returned a completed form and therefore have been excluded from the analysis. Further study is needed to examine whether the HLS-14 is acceptable to people with a wide range of HL level. Third, sociodemographic characteristics were not collected in the questionnaire survey. Therefore, we could not adjust for socioeconomic status in the comparison of HL scores. The age and gender differences in the HL scores must be confirmed in a population-based study with adjustment for socioeconomic status.

In conclusion, the HLS-14 demonstrated adequate reliability and validity as a generic HL measure for Japanese adults. This scale can be utilized for measuring functional, communicative, and critical HL in both the clinical and public health contexts. The use of HLS-14 may contribute to promoting a better understanding of advanced skills beyond reading comprehension and numeracy.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Health Labour Sciences Research Grant from the Ministry of Health, Labour, and Welfare (Grand Number 24230101) and the Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (C) from Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (Grand Number 23590814). We would like to thank Dr. Shuichi Mihara for his help with the questionnaire survey.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Appendix: 14-item Health literacy scale

References

- 1.World Health Organization (WHO). The WHO health promotion glossary (WHO/HPR/HEP/98.1). Available at: http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/about/HPG. Accessed 1 Mar 2013.

- 2.Dewalt DA, Berkman ND, Sheridan S, Lohr KN, Pignone MP. Literacy and health outcomes: a systematic review of the literature. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19:1228–1239. doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.40153.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ishikawa H, Yano E. Patient health literacy and participation in the health-care process. Health Expect. 2008;11:113–122. doi: 10.1111/j.1369-7625.2008.00497.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ngoh LN. Health literacy: a barrier to pharmacist–patient communication and medication adherence. Pharm Today. 2009;15:45–57. doi: 10.1331/JAPhA.2009.07075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nutbeam D. The evolving concept of health literacy. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67:2072–2078. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Powers BJ, Trinh JV, Bosworth HB. Can this patient read and understand written health information? JAMA. 2010;304:76–84. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jordan JE, Osborne RH, Buchbinder R. Critical appraisal of health literacy indices revealed variable underlying constructs, narrow content and psychometric weaknesses. J Clin Epidemiol. 2011;64:366–379. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ishikawa H, Takeuchi T, Yano E. Measuring functional, communicative, and critical health literacy among diabetic patients. Diabetes Care. 2008;31:874–879. doi: 10.2337/dc07-1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ishikawa H, Nomura K, Sato M, Yano E. Developing a measure of communicative and critical health literacy: a pilot study of Japanese office workers. Health Promot Int. 2008;23:269–274. doi: 10.1093/heapro/dan017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitsutake S, Shibata A, Ishii K, Okazaki K, Oka K. Developing Japanese version of the eHealth Literacy Scale (eHEALS) (in Japanese). Jpn J Public Health. 2011;58:361–71. [PubMed]

- 11.Tokuda Y, Okubo T, Yanai H, Doba N, Paasche-Orlow MK. Development and validation of a 15-item Japanese health knowledge test. J Epidemiol. 2010;20:319–328. doi: 10.2188/jea.JE20090096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Okamoto M, Kyutoku Y, Sawada M, Clowney L, Watanabe E, Dan I, Kawamoto K. Health numeracy in Japan: measures of basic numeracy account for framing bias in a highly numerate population. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:104. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-12-104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nutbeam D. Health literacy as a public health goal: a challenge for contemporary health education and communication strategies into the 21st century. Health Promot Int. 2000;15:259–267. doi: 10.1093/heapro/15.3.259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suka M, Odajima T, Orii T, Doi Y, Nakayama T, Yamamoto M, Sugimori H. A questionnaire survey on drug information: information-seeking behaviors and public attitudes toward drug information (in Japanese). J Jpn Soc Healthc Adm. 2011;48:49–55.

- 15.Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334. doi: 10.1007/BF02310555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terwee CB, Bot SD, de Boer MR, van der Windt DA, Knol DL, Dekker J, Bouter LM, de Vet HC. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hu L, Bentler PM. Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Struct Equ Modeling. 1999;6:1–55. doi: 10.1080/10705519909540118. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.van der Vaart R, Drossaert CH, Taal E, ten Klooster PM, Hilderink-Koertshuis RT, Klaase JM, van de Laar MA. Validation of the Dutch functional, communicative and critical health literacy scales. Patient Educ Couns. 2012;89:82–88. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2012.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coulter A, Ellins J. Effectiveness of strategies for informing, educating, and involving patients. BMJ. 2007;335:24–27. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39246.581169.80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Verbrugge LM. Sex differentials in health. Public Health Rep. 1982;97:417–437. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Oksuzyan A, Juel K, Vaupel JW, Christensen K. Men: good health and high mortality. Sex differences in health and aging. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2008;20:91–102. doi: 10.1007/BF03324754. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Galdas PM, Cheater F, Marshall P. Men and health help-seeking behaviour: literature review. J Adv Nurs. 2005;49:616–623. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03331.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]