Abstract

Background

Persistent wound drainage after hip arthroplasty is a risk factor for periprosthetic infection. Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) has been used in other fields for wound management although it is unclear whether the technique is appropriate for total hip arthroplasty.

Questions/purposes

We determined (1) the rate of wound complications related to use of NPWT for persistent incisional drainage after hip arthroplasty; (2) the rate of resolution of incisional drainage using this modality; and (3) risk factors for failure of NPWT for this indication.

Methods

In a pilot study we identified 109 patients in whom NPWT was used after hip arthroplasty for treating postoperative incisional drainage between April 2006 and April 2010. On average, the NPWT was placed on postoperative Day 3 to 4 (range, 2–9 days) and applied for 2 days (range, 1–10 days). We then determined predictors of subsequent surgery. Patients were followed until failure or a minimum of 1 year (average, 29 months; range, 1–62 months).

Results

Eighty-three patients (76%) had no further surgery and 26 patients (24%) had subsequent surgery: 11 had superficial irrigation and débridement (I&D), 12 had deep I&D with none requiring further surgery, and three ultimately had component removal. Predictors of subsequent surgery included international normalized ratio level greater than 2, greater than one prior hip surgery, and device application greater than 48 hours. There were no wound-related complications associated with NPWT.

Conclusions

The majority of our patients had cessation of wound drainage with NPWT.

Level of Evidence

Level IV, therapeutic study. See Guidelines for Authors for a complete description of levels of evidence.

Introduction

Postoperative incisional drainage reportedly occurs in 1% to 3% of patients undergoing primary total joint arthroplasty [4, 22]. Persistent wound drainage lasting greater than 48 hours after hip arthroplasty is a risk factor for periprosthetic joint infection (PJI) [4, 14, 22]. Patel et al. [10] estimated that each day of persistent wound drainage increases the risk of infection by 42%. Although many of the risk factors for persistent wound drainage are also independent risk factors for PJI, including malnutrition [4], excess anticoagulation [6], obesity [12], diabetes [21], and a higher American Society of Anesthesiologists score [12], it is also believed that the path that allows fluid to egress from the wound is a potential conduit for retrograde bacterial contamination into the wound. Thus, one goal in managing persistent postoperative wound drainage is to minimize the time to achieve a dry, healed wound.

In the immediate postoperative period, there are no standard guidelines for treating persistent wound drainage. Some surgeons perform local wound management using absorbent dressings [4] silver-impregnated dressings [11], and compression wraps [3]. Others routinely prescribed oral antibiotics during the period of wound drainage despite a lack of evidence for this practice [4]. Jaberi et al. [4] recommended superficial irrigation and débridement (I&D) if persistent drainage does not resolve despite nonoperative measures and deep I&D with modular component exchange if deep involvement is evident.

Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) has been used in multiple surgical fields for wound management. A number of studies in the plastic and general surgery literature [1, 2, 15, 16] have shown NPWT to decrease local tissue edema, decrease the time to wound healing, and improve split-thickness skin graft survival. In orthopaedics, it has been used to treat open fractures [8], fasciotomy wounds [24, 25], hematomas [19], and at-risk closed surgical incisions after high-energy orthopaedic trauma [13, 20]. These studies show that use of NPWT is associated with a decrease in the number of days that postoperative hematomas and surgical incisions over high-energy fractures drain as well as a decreased incidence of wound dehiscences and total infections. We were able to identify only one prior study applying the use of NPWT to the field of total joint arthroplasty. Pachowsky et al. randomized patients undergoing hip arthroplasty to a standard dry dressing versus the incisional NPWT and then analyzed the presence and volume of postoperative seroma using ultrasound. They reported finding a seroma in 90% of standard dressing patients and only 44% of NPWT patients with mean volumes of 5.08 mL and 1.97 mL, respectively [7]. However, they had a small sample size and no discussion of the clinical importance of the presence of ultrasound-confirmed seromas (eg, relation to incisional drainage or infection), thus limiting the applicability of their findings. No study to date has evaluated the use of NPWT in the setting of persistent incisional drainage after THA.

We therefore determined (1) the rate of wound complications related to use of NPWT for persistent incisional drainage after hip arthroplasty; (2) the rate of resolution of incisional drainage using this modality; and (3) risk factors for failure of the NPWT for this indication.

Patients and Methods

Using our institutional arthroplasty database and the hospital billing database for this pilot study, we identified 134 patients undergoing hip arthroplasty who had a NPWT (Wound VAC®; KCI, San Antonio, TX, USA) placed in the intraoperative or immediate postoperative periods between April 1, 2006, and April 1, 2010. According to our institutional protocol, the indication for using postoperative NPWT for incisional drainage is persistent serous or serosanguinous drainage that persists despite observation, dressings, and local wound care. Contraindications for use of postoperative incisional NPWT were (1) clinical evidence of surgical site infection such as erythema or purulent drainage; and (2) clinical signs of hematoma such as wound swelling, fluctuance, and bloody drainage. We excluded 12 patients for whom NPWT was used for management of an open surgical wound, in patients who were being actively treated for a PJI, and in cases of intraoperative application of the NPWT. Patients were followed until failure or a minimum of 1 year (average, 29 months; range, 1–62 months). Thirteen patients were treated for persistent wound drainage but were excluded as a result of lack of appropriate clinical followup leaving us with 109 patients for analysis. This cohort represented 2% (109 of 5627) of all patients undergoing hip arthroplasty operated on during this 4-year period. The mean age of our cohort was 64 years (range, 34–88 years) and had an approximately even sex distribution (55 male, 54 female) (Table 1). The average body mass index (BMI) was 31 kg/m2 (range, 17–58 kg/m2), the mean American Society of Anesthesiologists score 3 (range, 1–4), and Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) 2 (range, 0–6). Although the majority of patients (68%) had undergone a primary hip arthroplasty, the study cohort included 23 (21%) revision hip arthroplasties in patients who had a mean of two prior ipsilateral hip surgeries (range, 1–5). All data were obtained from the electronic and paper medical records. We obtained institutional review board approval before initiation of this study and patient medical records were used to collect our data.

Table 1.

Demographics of patients treated with Wound VAC® for persistently draining wounds after hip arthroplasty

| Total number of patients | 109 (55 male; 54 female) |

| Mean age (years) | 64 (range, 34–88) |

| Mean clinical followup (months) | 29 (range, 1–62) |

| Mean BMI (kg/m2) | 31 (range. 17–58) |

| Mean ASA | 3 (range, 1–4) |

| Mean CCI | 2 (range, 0–6) |

| Surgical procedures | |

| THA | 74 (68%) |

| DJD | 69 (93%) |

| FNF | 4 (5%) |

| AVN | 1 (2%) |

| Hemiarthroplasty | 4 (4%) |

| Conversion hip arthroplasty | 8 (7%) |

| Revision hip arthroplasty | 23 (21%) |

| Femur | 6 (26%) |

| Acetabulum | 7 (30%) |

| Both | 7 (30%) |

| Head-liner | 3 (15%) |

BMI = body mass index; ASA = American Society of Anesthesiologists; CCI = Charlson Comorbidity Index; DJD = degenerative joint disease; FNF = femoral neck fracture; AVN = avascular necrosis.

Since 2006, the routine postoperative wound management protocol for patients undergoing hip arthroplasty at our institution has been to leave the sterile operative dressing on for 24 to 48 hours. If the wound is dry after removal of the operative dressing, no further dressing is applied. However, if there is any drainage from the incision, a sterile gauze dressing is reapplied and changed as needed but no less frequently than once a day. The NPWT was ordered at the discretion of the treating surgeon when standard wound management failed to demonstrate resolution of postoperative incisional drainage as determined by the need to change more than one sterile gauze dressing per day as a result of saturation by postoperative day (POD) 3 to 4. The prophylactic antibiotics protocol was the same among all patients as dictated by Surgical Care Improvement Project guidelines. Specifically, patients received 24 hours of prophylactic antibiotics and in no cases were antibiotics reinitiated at the time of placement of the VAC. The protocol before 2006 would have been to perform surgical débridement once it was determined that the drainage required more than one dressing change per day beyond POD 3 despite local wound care and observation [4].

The NPWT was applied at the bedside in the following manner. After cleaning the surgical incision with alcohol, strips of the clear NPWT adhesive dressing are placed around the incision to prevent maceration of the wound edges (Fig. 1A). Then, a strip of the black Granufoam™ (KCI) measuring the length of the incision is placed over the adhesive layer. Finally, a second layer of adhesive is placed on top of the Granufoam™, the vacuum tubing applied, and the suction set at 125 mmHg of continuous pressure (Fig. 1B) for 24 to 48 hours. Although the protocol was followed in the majority of cases, we did find some variability in the timing and patterns of use of the NPWT. The NPWT in most cases was initially placed on POD 3 or 4 (72%) (range POD 2–9) (Fig. 2), applied in most cases for 2 days (75%) (range, 2 to > 5 days) (Fig. 3), and in 10 cases (9%), a second application of the NPWT was used for persistent drainage despite the initial application.

Fig. 1A–B.

Clinical images of the application of the NPWT for incisional drainage after hip arthroplasty. (A) Strips of the adhesive are placed around the perimeter of the incision to prevent skin edge maceration. (B) The sponge, cut to the length of the incision, is covered by a second layer of adhesive and the suction tubing is applied.

Fig. 2.

Graph depicting the application of the NPWT based on POD. In the majority of cases, the NPWT was placed on POD 3 to 4.

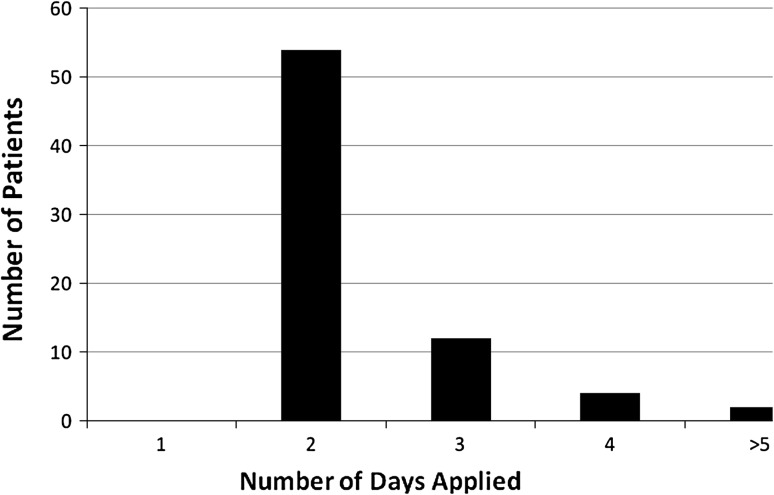

Fig. 3.

Graph depicting the length of application of the NPWT. In the majority of cases, the NPWT was applied for 48 hours.

After application of the NPWT, we documented any evidence of local skin complications associated with the intervention such as skin blistering, tearing, or maceration noted in the medical record. Unfortunately, the volume of drainage was not routinely or consistently quantified in the medical record and thus we could not analyze this variable. For all patients requiring subsequent surgery, operative notes were reviewed for signs of overt clinical infection (eg, gross purulence). We defined failure as further surgery for (1) persistent wound drainage requiring more than one local dressing change per day present 24 hours after removal of the NPWT device or (2) subsequent PJI. These included patients who had to return to the operating room for I&D with or without modular component exchange as well as patients who ultimately required two-stage exchange arthroplasty for PJI.

In the acute postoperative period (ie, within 4–6 weeks of index procedure), we defined PJI based on intraoperative culture data, whereas chronic PJI was defined by the 2011 Musculoskeletal Infection Society (MSIS) definition [9]: (1) presence of draining sinus; or (2) pathogen isolated by culture from two separate samples of the affected joint; or (3) when four of the following six criteria exist: elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate or C-reactive protein, elevated synovial white blood cell count, elevated synovial neutrophil percentage, presence of purulence in the affected joint, or isolation of microorganism in one culture, or greater than five neutrophils per high-powered field (HPF) in five HPFs from histological analysis. Because we did not routinely send intraoperative specimens for frozen section and histological analysis, we used a modification of the MSIS minor criteria whereby we defined infection by existence of three of the five remaining criteria.

Patients returned for routine clinical and radiographic followup at 6 weeks, 3 months, 6 months, annually, or earlier if there was concern for recurrent infection. When there was clinical concern for infection, patients returned for more frequent followup and also had serology and joint aspiration performed. As a retrospective study, there were cases of conflicting or missing data. Of the data on the dependent variables we analyzed, the only instances of missing or conflicting data pertained specifically to the initial application and use of the Wound VAC®. Specifically, although there was always a dated order for the Wound VAC® application, in 30% of patients, there was not a dated order for its discontinuation. Therefore, we had to confirm the presence of a Wound VAC® based on the daily progress notes. For any discrepancies between the electronic and paper medical record based on the dates of Wound VAC® application, we used the paper chart as the final arbitrator.

To determine factors associated with failure of the use of the NPWT for this indication, we collected potential predictive variables that may have influenced the outcome. Patient-related variables included BMI and CCI. Surgical variables included number of prior ipsilateral hip surgeries and perioperative variables included occurrence of an international normalized ratio (INR > 2.0). During the period of this study, patients were placed on venous thromboembolism prophylaxis consisting of warfarin with a goal INR 1.8–2.0. Variables related to the NPWT included the following: POD NPWT applied, number of days the NPWT was applied, and a second application. Using the aforementioned variables, multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to assess the risk of treatment failure. The regression analysis was performed in a backward stepwise manner. Statistical analyses were done with R 2.14.1 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

We found no instances of skin blistering, maceration, or skin tearing related to the use of NPWT. In addition, of the patients who required I&D in the immediate postoperative period despite the NPWT application, there was no evidence of gross purulence or other overt clinical signs of infection and no confirmed cases of PJI based on culture data.

A total of 83 patients (76%) had no further surgery after application of the NPWT, whereas 26 patients (24%) did. Eleven of these patients underwent superficial I&D and 12 patients required deep I&D with modular component exchange during the same hospitalization. None of these patients required further surgery, thus resulting in a component retention rate of 97% (106 of 109). Three patients ultimately required component removal and a two-stage exchange arthroplasty at 20, 35, and 41 months after the index arthroplasty (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

The flowchart illustrates the clinical outcomes after use of the NPWT for persistent wound drainage after hip arthroplasty. In 76% of patients, a dry wound was achieved after NPWT application. Of those that required surgery, 88% were successfully treated with isolated I&D. Only three patients underwent two-stage exchange arthroplasty. Sx = symptoms.

Positive predictors of NPWT failure included INR level greater than 2 (odds ratio [OR], 4.2; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.2–15.3; p = 0.03), greater than one prior hip surgery (OR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.2–4.5; p < 0.01), and NPWT application greater than 48 hours (OR, 2.3; 95% CI, 1.2–4.2; p = 0.01) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Predictors of failure based on multivariate regression analysis

| Variable | OR (95% CI) | p value |

|---|---|---|

| INR > 2 | 3.33 (1.06–10.52) | 0.04 |

| Multiple prior ipsilateral hip surgeries | 2.32 (1.24–4.31) | 0.008 |

| Multiple VAC applications | 5.00 (1.06–23.71) | 0.04 |

| VAC application > 48 hours | 1.93 (1.11–3.37) | 0.02 |

OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval; INR = international normalized ratio.

Discussion

Postoperative wound drainage after total joint arthroplasty is a vexing clinical problem for orthopaedic surgeons without clearcut clinical practice guidelines. Although in the majority of cases it is self-limiting, in a certain proportion of patients, the drainage persists and increases the risk of surgical site infection [10, 14]. In other surgical disciplines NPWT has been used to promote wound healing for at-risk surgical wounds [13, 19, 20], although none of these studies evaluate the use of NPWT for the management of persistent incisional drainage for hip arthroplasty. We sought to review our institutional experience with this technique to establish (1) the rate of wound complications related to use of NPWT; (2) the rate of obtaining a dry wound using this modality; and (3) risk factors for failure of the NPWT for this indication.

As a retrospective observational investigation, our study had several notable limitations. First, we had no concurrent control group of patients with persistent drainage who were treated with a modality other than NPWT. Although our findings establish the number of failures of the intervention, we cannot judge whether it reduces the rate of subsequent surgery. Second, although NPWT was used by many surgeons at our institution to manage prolonged incisional wound drainage, we had no defined protocol for either its initiation or discontinuation. As a result, we are unable to provide recommended guidelines for the exact protocol for use of the device on postoperative draining wounds, yet we do not believe this limitation substantially interferes with the results that we do report. Third, like with any retrospective study, there were instances of ambiguous and/or missing data points resulting from omissions or conflicting data in the electronic and paper medical records. Such instances were few and in all cases were able to be reconciled. As such, we do not believe this limitation influenced our results to a substantial degree. Fourth, we were unable to quantify the amount of drainage before application of the NPWT or after removal of the device because these data were not routinely collected in the medical record. As such, we were unable to investigate the influence of the NPWT output as a variable but plan to do so in a future prospective study. Fifth, we were unable to determine the nutritional status of the patients in this study, because it was not our institutional protocol to routinely obtain preoperative nutrition laboratory values such as albumin, prealbumin, or transferring our patients undergoing hip arthroplasty. This is an important limitation to note because nutrition is reportedly a key component of wound healing [4]. We plan to investigate its role in a future prospective study. Lastly, 13 patients were eliminated from our study as a result of the lack of a minimum 12-month followup. Although it is possible that the lack of followup of these patients may have affected our results, we do not believe they would have resulted in a substantial impact on our results and conclusions.

We believe our lack of local skin complications is the result of the technique used, in which strips of adhesive dressing are placed directly on the skin around the incision and the foam is placed on top of this adhesive barrier directly over only the incision to prevent skin edge maceration. In addition, we found no cases of PJI that appeared to be related to the NPWT application. Our findings of no wound-related complications are consistent with prior literature in other fields [5, 7, 17–20, 23]. Reddix et al. studied the effect of NPWT on wound complications (eg, dehiscences, infections) associated with the treatment of acetabular fractures in morbidly obese patients and found no wound complications in 19 consecutive patients over 5 years [13]. In a randomized controlled trial comparing NPWT with standard postoperative dressings in a cohort of blunt trauma patients with high-risk fracture types (tibial plateau, pilon, calcaneus) requiring operative fixation, Stannard et al. similarly demonstrated a decreased incidence of wound dehiscence and total infections in the NPWT group [20].

Use of the Wound VAC® for persistent incisional drainage after hip arthroplasty was associated with resolution of drainage in 76% of our patients. Although our study lacked a concurrent control group, we are able to compare our results with historical control data previously published from our institution [4]. Before 2006, our institutional protocol for the management of persistent postoperative drainage was use of prophylactic oral antibiotics and local wound management. If substantial drainage persisted on or after POD 4, I&D was performed at the discretion of the treating surgeon. Jaberi et al. reported the results of 83 patients who required surgical I&D as a result of persistent drainage and found the intervention prevented further surgery in 76% of patients, whereas 20 (24%) patients required further treatment (repeat I&D, N = 3; two-stage exchange arthroplasty, N = 11; resection arthroplasty, N = 5; suppressive antibiotics, N = 1) [4]. Our current cohort of 109 patients with persistently draining surgical wounds represents a similar group of patients who would have previously met indications for surgical débridement. After using NPWT, 76% of patients experienced cessation of wound drainage. Furthermore, of those patients who ultimately required operative intervention in our cohort, a single débridement resolved the drainage in 88% of cases similar to the surgical results of Jaberi et al. Thus, when the NPWT application fails, it does not appear to compromise the ability of a subsequent surgical débridement to resolve wound drainage.

We found three groups of patients in whom the NPWT had a higher failure rate: patients with elevated INR > 2.0, patients with prior ipsilateral hip surgeries, and patients in whom the NPWT was applied for greater than 48 hours. Coagulopathy is a known risk factor for the development of postoperative hematoma, wound drainage, delayed wound healing, and ultimately of PJI [10]. This also suggests NPWT may be more effective in the setting of a draining seroma as compared with a draining hematoma. Patients who have had greater than one prior ipsilateral hip surgery were also at increased risk of failing NPWT treatment. Presumably, the increased number of operations on the hip results in compromise to the soft tissues envelope and vascularity to the area, which could lead to more challenging closure, thereby resulting in prolonged drainage and delayed wound healing. Additionally, we found use of the NPWT for greater than 48 hours was associated with treatment failure. We believe this use of the NPWT potentially represents a marker of failure rather than is causally related to treatment failure.

Our institutional experience with the use of NPWT for persistent incisional drainage after hip arthroplasty demonstrated no wound complications related to the technique and was associated with resolution of drainage in 76% of our patients. Based on our data, which demonstrate a higher failure rate in patients with more than one prior hip surgery or with a postoperative INR ≥ 2, a lower threshold for surgical intervention may be warranted in these situations. However, to more clearly define both the proper clinical indications and optimal protocol for using NPWT for persistent incisional drainage after hip arthroplasty, a well-designed prospective randomized controlled trial is necessary.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mitch Maltenfort PhD, for assistance with the statistical analysis of the article.

Footnotes

Each author certifies that he or she, or a member of his or her immediate family, has no funding or commercial associations (eg, consultancies, stock ownership, equity interest, patent/licensing arrangements, etc) that might pose a conflict of interest in connection with the submitted article.

All ICMJE Conflict of Interest Forms for authors and Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research editors and board members are on file with the publication and can be viewed on request.

Each author certifies that his or her institution approved the human protocol for this investigation, that all investigations were conducted in conformity with ethical principles of research, and that informed consent for participation in the study was obtained.

References

- 1.Braakenburg A, Obdeijn MC, Feitz R, van Rooij IA, van Griethuysen AJ, Klinkenbijl JH. The clinical efficacy and cost effectiveness of the vacuum-assisted closure technique in the management of acute and chronic wounds: a randomized controlled trial. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;118:390–397. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000227675.63744.af. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.DeFranzo AJ, Argenta LC, Marks MW, Molnar JA, David LR, Webb LX, Ward WG, Teasdall RG. The use of vacuum-assisted closure therapy for the treatment of lower-extremity wounds with exposed bone. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2001;108:1184–1191. doi: 10.1097/00006534-200110000-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hahn GJ, Grant D, Bartke C, McCartin J, Carn RM. Wound complications after hip surgery using a tapeless compressive support. Orthop Nurs. 1999;18:43–49. doi: 10.1097/00006416-199905000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaberi FM, Parvizi J, Haytmanek CT, Joshi A, Purtill J. Procrastination of wound drainage and malnutrition affect the outcome of joint arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:1368–1371. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0214-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Masden D, Goldstein J, Endara M, Xu K, Steinberg J, Attinger C. Negative pressure wound therapy for at-risk surgical closures in patients with multiple comorbidities: a prospective randomized controlled study. Ann Surg. 2012;255:1043–1047. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182501bae. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Minnema B, Vearncombe M, Augustin A, Gollish J, Simor AE. Risk factors for surgical-site infection following primary total knee arthroplasty. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2004;25:477–480. doi: 10.1086/502425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pachowsky M, Gusinde J, Klein A, Lehrl S, Schulz-Drost S, Schlechtweg P, Pauser J, Gelse K, Brem MH. Negative pressure wound therapy to prevent seromas and treat surgical incisions after total hip arthroplasty. Int Orthop. 2012;36:719–722. doi: 10.1007/s00264-011-1321-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Parrett BM, Matros E, Pribaz JJ, Orgill DP. Lower extremity trauma: trends in the management of soft-tissue reconstruction of open tibia-fibula fractures. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2006;117:1315–1322. doi: 10.1097/01.prs.0000204959.18136.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Parvizi J, Zmistowski B, Berbari EF, Bauer TW, Springer BD, Della Valle CJ, Garvin KL, Mont MA, Wongworawat MD, Zalavras CG. New definition for periprosthetic joint infection: from the Workgroup of the Musculoskeletal Infection Society. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011;469:2992–2994. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-2102-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Patel VP, Walsh M, Sehgal B, Preston C, DeWal H, Di Cesare PE. Factors associated with prolonged wound drainage after primary total hip and knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:33–38. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Percival SL, Slone W, Linton S, Okel T, Corum L, Thomas JG. The antimicrobial efficacy of a silver alginate dressing against a broad spectrum of clinically relevant wound isolates. Int Wound J. 2011;8:237–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2011.00774.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pulido L, Ghanem E, Joshi A, Purtill JJ, Parvizi J. Periprosthetic joint infection: the incidence, timing, and predisposing factors. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2008;466:1710–1715. doi: 10.1007/s11999-008-0209-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reddix RN, Jr, Tyler HK, Kulp B, Webb LX. Incisional vacuum-assisted wound closure in morbidly obese patients undergoing acetabular fracture surgery. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2009;38:446–449. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Saleh K, Olson M, Resig S, Bershadsky B, Kuskowski M, Gioe T, Robinson H, Schmidt R, McElfresh E. Predictors of wound infection in hip and knee joint replacement: results from a 20 year surveillance program. J Orthop Res. 2002;20:506–515. doi: 10.1016/S0736-0266(01)00153-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scherer LA, Shiver S, Chang M, Meredith JW, Owings JT. The vacuum assisted closure device: a method of securing skin grafts and improving graft survival. Arch Surg. 2002;137:930–933. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.137.8.930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Schoemann MB, Lentz CW. Treating surgical wound dehiscence with negative pressure dressings. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2005;51:15S–20S. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stannard JP, Atkins BZ, O’Malley D, Singh H, Bernstein B, Fahey M, Masden D, Attinger CE. Use of negative pressure therapy on closed surgical incisions: a case series. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2009;55:58–66. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stannard JP, Gabriel A, Lehner B. Use of negative pressure wound therapy over clean, closed surgical incisions. Int Wound J. 2012;9(Suppl 1):32–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-481X.2012.01017.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stannard JP, Robinson JT, Anderson ER, McGwin G, Jr, Volgas DA, Alonso JE. Negative pressure wound therapy to treat hematomas and surgical incisions following high-energy trauma. J Trauma. 2006;60:1301–1306. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000195996.73186.2e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stannard JP, Volgas DA, McGwin G, 3rd, Stewart RL, Obremskey W, Moore T, Anglen JO. Incisional negative pressure wound therapy after high-risk lower extremity fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2012;26:37–42. doi: 10.1097/BOT.0b013e318216b1e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vince K, Chivas D, Droll KP. Wound complications after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 2007;22:39–44. doi: 10.1016/j.arth.2007.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Weiss AP, Krackow KA. Persistent wound drainage after primary total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty. 1993;8:285–289. doi: 10.1016/S0883-5403(06)80091-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilkes RP, Kilpad DV, Zhao Y, Kazala R, McNulty A. Closed incision management with negative pressure wound therapy (CIM): biomechanics. Surg Innov. 2012;19:67–75. doi: 10.1177/1553350611414920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang CC, Chang DS, Webb LX. Vacuum-assisted closure for fasciotomy wounds following compartment syndrome of the leg. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2006;15:19–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zannis J, Angobaldo J, Marks M, DeFranzo A, David L, Molnar J, Argenta L. Comparison of fasciotomy wound closures using traditional dressing changes and the vacuum-assisted closure device. Ann Plast Surg. 2009;62:407–409. doi: 10.1097/SAP.0b013e3181881b29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]