Abstract

Objective

To determine if girls with Duarte variant galactosemia (DG) have an increased risk of developing premature ovarian insufficiency based on prepubertal anti-Mullerian hormone (AMH) levels.

Design

Cross-sectional study.

Setting

University research laboratory.

Patient(s)

Study volunteers included 57 girls with DG, 89 girls with classic galactosemia (GG), and 64 control girls between the ages of < 1 month and 10.5 years.

Intervention(s)

Blood sampling.

Main Outcome Measure(s)

We determined AMH and FSH levels in study volunteers with and without Duarte variant or GG.

Result(s)

FSH levels were significantly higher and AMH levels significantly lower in girls with GG than in age-stratified control girls, but there was no significant difference between FSH and AMH levels in girls with DG and control girls.

Conclusion(s)

Although > 80% of girls with GG in this study demonstrated low to undetectable AMH levels consistent with diminished ovarian reserve, 100% of girls with DG in our study demonstrated no apparent decrease in AMH levels or increase in FSH levels, suggesting that these girls are not at increased risk for premature ovarian insufficiency.

Keywords: POI, galactosemia, Duarte, DG, ovarian function, AMH, MIS, FSH

Duarte galactosemia (DG) is a mild variant of galactose-1-P-uridy-lyltransferase (GALT) deficiency that affects > 1 in 5,000 newborns; affected individuals carry one severe, or G, allele of the GALT gene and one Duarte, or D/D2, allele (1). In contrast to patients with classic galactosemia (GG), who demonstrate ≤ 1% normal GALT activity in hemolysates, patients with DG demonstrate, on average, 25% normal GALT enzyme activity levels (1). Of infants flagged for possible galactosemia by newborn screening protocols, the number eventually diagnosed with DG outnumber those diagnosed with GG almost ten to one (2, 3).

Unlike with GG, infants with DG typically do not exhibit acute or potentially lethal symptoms, even on a milk-based diet; however, these infants may demonstrate elevated galactose metabolites, especially red blood cell (RBC) galactose-1-phosphate (gal-1P) and urinary galactitol (4). Beyond the first year of life, RBC gal-1P levels tend to normalize, but RBC galactitol and galactonate, plasma galactose and galactitol, and urinary galactitol and galactonate levels may remain elevated, especially if the child continues to consume dairy products (3). Do these elevated galactose metabolites forewarn that children with DG are at increased risk for developing galactosemia-associated complications later in life? Although few long-term complications have been reported in older children or adults with DG, the fact that most Duarte patients are lost to follow-up early in childhood has left this question largely unanswered (2).

Given the uncertainty of long-term outcome in DG and the possible role of dietary galactose as a mediator of outcome, clinical centers and the families they serve have struggled with the question of what is the best diet for an infant with DG? Some health care providers have recommended no intervention or follow-up surveillance for their DG patients, others have recommended careful dietary galactose restriction for the first year of life only, and yet others have recommended that mothers who wish to breast-feed their DG infants alternate feedings between breast-milk and soy formula (2). In short, there has been no uniform standard of care.

In an effort to begin addressing the question of long-term outcome in DG, Ficicioglu et al. (4) conducted follow-up studies on 28 children aged 1–6 years. Of this cohort, 17 children had been treated with galactose restriction for the first year of life; the other 11 children had remained on a normal milk diet. All 28 children scored within the normal range on age-appropriate tests of development, cognition, and language skills (4), supporting the conclusion that DG is indeed benign. In an independent study, however, Powell et al. (5) revealed potential evidence of a problem. Those authors compared newborn screening records collected from the greater Atlanta area in 1988–2001 with information in the Metropolitan Atlanta Developmental Disabilities Surveillance Program and the Special Education Database of Metropolitan Atlanta. Of 59 DG children identified in the study cohort, none had been diagnosed with cognitive disability, cerebral palsy, hearing loss, vision impairment, or an autism spectrum disorder. However, the proportion of DG children who had received special educational services, predominantly for speech or language difficulties, was notably above that of control subjects (5). Whether this disparity reflects an innate difference in these children’s abilities, or rather, a difference in their access to special services, remains unclear.

The question of whether girls or women with DG are at increased risk for premature ovarian insufficiency (POI) has been particularly difficult to address, because most DG patients are lost to follow-up long before puberty. Ficicioglu et al. measured FSH levels in 12 of their young study volunteers (4), finding no abnormalities; however, owing to quiescence of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis in childhood, FSH is a notoriously insensitive marker of ovarian function for this age group (6, 7). Some women with DG come to clinical attention as adults when they give birth to a child with galactosemia, and these women are, by definition, fertile; however, obvious ascertainment bias precludes extending outcomes from these women to the DG population at large.

Herein, we have addressed the question of ovarian function in a cohort of 57 girls with DG by analyzing their plasma anti-Müllerian hormone (AMH) and FSH levels compared with age-stratified control girls. Earlier studies have defined the normal ranges for AMH in healthy girls and women of different ages, and have demonstrated that AMH is a highly sensitive and reproducible indicator of ovarian status (8–18). Furthermore, we have previously reported that > 80% of girls and women with GG demonstrate profoundly diminished levels of serum or plasma AMH (7). FSH levels historically have been used in an attempt to assess ovarian function in GG (19), and we have previously confirmed that girls with GG have significantly higher levels of FSH during infancy/very early childhood and then again in puberty and beyond (7). Here we asked the simple question: Are AMH levels, or FSH levels, detected in girls with DG statistically distinguishable from those in control girls? The answer was clear: Unlike AMH and FSH levels in girls with GG, AMH and FSH levels in girls with DG were indistinguishable from those in control girls. These data support the conclusion that, unlike their counterparts with GG, girls with DG are not at increased risk for POI.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Subjects

All case (DG or GG) and control samples were collected from girls between the ages of < 1 month to 10.5 years. For details, see the Supplemental Materials and Methods (available online at www.fertstert.org).

Assays

Sample collection/storage

All blood samples were drawn into sodium heparin tubes from girls ≤ 10.5 years old. For details, see the Supplemental Materials and Methods.

AMH measurements

AMH levels in plasma or serum were determined using the AMH/Müllerian-inhibiting substance ELISA kit from Diagnostic Systems Laboratories. For details, see the Supplemental Materials and Methods.

FSH measurements

Levels of FSH in plasma or sera were quantified using a kit from Abbott-Architect. For details, see the Supplemental Materials and Methods.

Statistical Analyses of AMH and FSH Levels

We used linear regression to examine the relationship between hormone levels and galactosemia status (DG, GG, or control) separately in three distinct age groups (< 3 months, 3 months to < 18 months, and ≥ 18 months). For details, see the Supplemental Materials and Methods.

RESULTS

Study Volunteers

Samples were obtained from 64 control girls, 57 patients with DG, and 89 patients with GG, ranging in age from < 1 month to 10.5 years (Table 1). Patients from each cohort were stratified into three age groups, birth to 3 months (neonatal), > 3 months to 18 months (“mini puberty”), and > 18 months to 10.5 years (prepubertal). The values detected in our control groups corresponded to normal ranges that have been published previously for those age groups (18, 20, 21).

TABLE 1.

Subjects enrolled in this study.

| n | Age | Age, y (mean ± SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Control | ||

| 26 | 0–3 mo | 0.08 ± 0.06 |

| 15 | > 3–18 mo | 0.63 ± 0.34 |

| 23 | > 18 mo to 10.5 y | 6.18 ± 2.94 |

| 64 | Total | |

| DG | ||

| 30 | 0–3 mo | 0.10 ± 0.08 |

| 20 | > 3–18 mo | 0.93 ± 0.27 |

| 7 | > 18 mo to 10.5 y | 5.11 ± 3.46 |

| 57 | Total | |

| GG | ||

| 7 | 0–3 mo | 0.13 ± 0.10 |

| 20 | > 3–18 mo | 0.92 ± 0.37 |

| 62 | > 18 mo to 10.5 y | 5.67 ± 2.39 |

| 89 | Total | |

Note: DG = Duarte galactosemia; GG = classic galactosemia.

Badik. Ovarian function in Duarte galactosemia. Fertil Steril 2011.

AMH Levels in DG and Control Samples were Indistinguishable in All Three Age Groups

Neonates

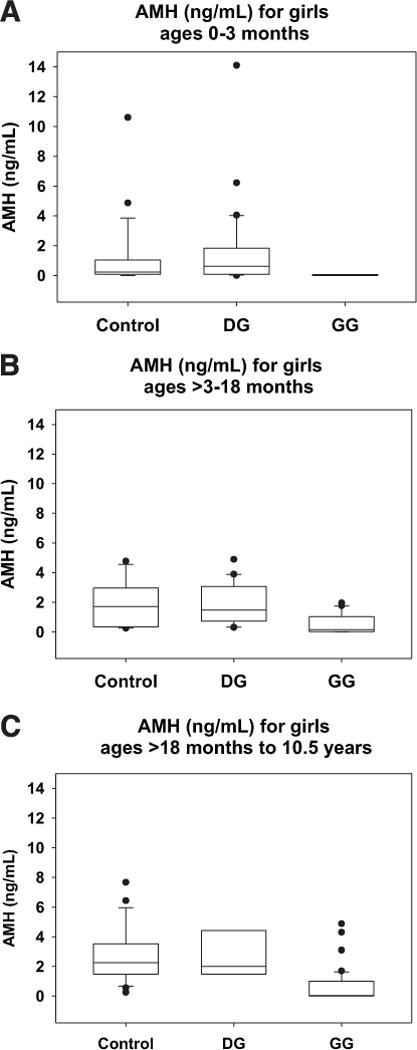

We measured serum or plasma AMH levels as an indicator of ovarian status in 30 newborn girls with DG, 7 newborn girls with GG, and 26 newborn control girls. Previously published data indicate that in normal healthy girls AMH levels are low to undetectable at birth and rise to detectable levels by age 3 months (8, 18, 20, 21). Sir-Petermann et al. (21) also demonstrated low but detectable levels of AMH in 2-month-old girls, regardless of birth weight, with values for normal-birth-weight girls matching our values reported here for control girls (Fig. 1A). As illustrated in Figure 1A, although the AMH levels in GG newborns were lower than those detected in control girls (Wald Test = −3.1; P = .002), there was no significant difference in the AMH levels between DG and control girls in this age group (Wald test = 0.38; P = .71).

FIGURE 1.

Box and whisker plots of AMH values by age group and diagnostic category (A) girls ages 0 to 3 months, (B) girls ages > 3 to 18 months, and (C) girls ages > 18 months to 10.5 years. The bottom and top of each box represent the 25th and 75th percentiles of the data set, respectively, and the horizontal line within each box represents the 50th percentile for that data set. The lower and upper whiskers represent the 10th and 90th percentiles for the data set, respectively, and any data points falling outside of the box are plotted.

≥ 3 to 18 months

We measured serum or plasma AMH levels in 20 DG girls, 20 GG girls, and 15 control girls in the > 3- to 18-month age group (Fig. 1B). The upper age limit for this range was selected to distinguish between girls experiencing “mini-puberty” with an active hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis as indicated by elevated FSH levels (6) and older prepubertal girls in whom this axis should be quiescent. For control girls, FSH levels are generally considered to be quiescent by 18 months (6, 22, 23), although they can remain elevated longer in some populations, such as girls with Turner syndrome (18, 24, 25). The AMH levels of DG girls in this age range were not significantly different from those of control girls (Wald test = 0.41; P = .67), whereas the AMH levels of the GG girls in this age range were significantly lower than those of control girls (Wald test = −3.8; P < .001).

≥ 18 months to 10.5 years

We also measured serum or plasma AMH in 7 DG girls, 62 GG girls, and 23 control girls in the ≥ 18-month to 10.5-year age range (Fig. 1C). The AMH levels in serum or plasma from these “older prepubertal” DG girls were also not significantly different from those of control girls (Wald test = −0.14; P = .89), whereas the AMH levels in GG samples were, again, significantly lower than those of control girls (Wald test = −7.72; P < .001).

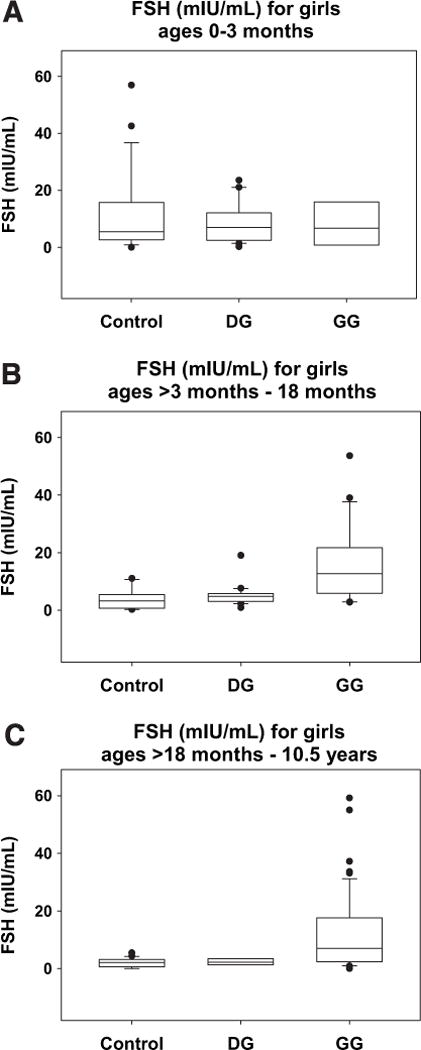

FSH Measurements Further Suggest Normal Ovarian Function in DG Girls

Consistent with the AMH results described above, FSH values measured in the same samples also suggested normal ovarian function in prepubertal girls with DG (Fig. 2). In brief, for FSH values measured in neonatal cases and controls there was no statistically significant difference between DG and control girls (Wald test = −0.385; P = .73) or between GG and control girls (Wald test = −0.51; P = .62) In contrast, in the “minipuberty” age group (> 3 to 18 months), DG and control FSH values remained low (~5 mIU/mL) and showed no difference between groups (Wald test = 1.56; P = .14), whereas GG FSH values rose markedly (to > 15 mIU/mL) and were significantly different from those of control girls (Wald test = 5.04; P < .001). Finally, in the older prepubertal age group, DG and control FSH values again remained low (< 4 mIU/mL) and showed no significant difference (Wald test = 0.73; P = .47), whereas FSH levels in the GG girls, though relatively lower (< 10 mIU/mL) than the “minipuberty” GG levels, were nonetheless significantly different from those in control girls (Wald test = 4.57; P < .001). Of note, in these older prepubertal GG girls, FSH was expected to return to baseline despite apparent ovarian dysfunction due to quiescence of the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis in this age group.

FIGURE 2.

Box and whisker plots of FSH values by age group and diagnostic category (A) girls ages 0 to 3 months, (B) girls ages > 3 to 18 months, and (C) girls ages > 18 months to 10.5 years. The bottom and top of each box represent the 25th and 75th percentiles of the data set, respectively, and the horizontal line within each box represents the 50th percentile for that data set. The lower and upper whiskers represent the 10th and 90th percentiles for the data set, respectively, and any data points falling outside of the box are plotted.

DISCUSSION

Premature ovarian insufficiency is the most common long-term complication experienced by girls and women with GG (19, 26) The purpose of the present study was to determine whether girls with DG may also be at increased risk for POI. Ascertainment is difficult, because most girls with DG are lost to follow-up as young children, and those who return to clinical attention as adults typically do so because they have given birth to a child with galactosemia. Given these constraints, we chose to address the question by comparing levels of two circulating hormones, AMH and FSH, in serum or plasma samples from cohorts of girls with DG and GG and control girls, aged birth to 10.5 years. Although FSH values can vary considerably in prepubertal girls and throughout the menstrual cycle after puberty, AMH appears to be a more reliable measure of ovarian function in prepubertal girls. It may also be drawn at any time in the menstrual cycle after puberty. Our results confirm that diminished ovarian reserve is prevalent in girls with GG, but we see no evidence of diminished ovarian reserve in girls with DG.

Recent studies have demonstrated no clear evidence of cognitive, developmental, or speech complications in DG patients (4). Furthermore, studies of AMH levels in adult galactosemia carriers, ascertained as the mothers of GG patients, demonstrated no clear depression of AMH levels, and they were not more likely to have difficulties conceiving. These data suggest that women who have on average 50% normal GALT levels have normal ovarian function (27, 28). Additionally, our data suggest that DG women, who have on average 25% normal GALT levels, have normal ovarian reserve.

We studied AMH and FSH levels in plasma or serum samples from young girls, because as a direct result of newborn screening for galactosemia, large numbers of asymptomatic infants and toddlers with DG come to clinical attention and have blood drawn as part of their routine diagnostic work-up. Many of these children then return to the clinic as toddlers to have a galactose challenge which entails an additional blood draw. Samples are therefore available with little if any ascertainment bias in their selection.

We subdivided samples from both case and control groups according to age, because AMH levels are age dependent and comparisons are valid only between age-matched groups (18, 20). Furthermore, endocrine development in prepubertal girls can be logically divided into two phases: a “mini-puberty,” which consists of a postnatal surge in gonadotropin levels persisting until between ages 12 and 24 months, and a period of quiescence in the hypothalamic-pituitary-ovarian axis that ends just before puberty (6, 22, 29). We therefore divided our samples into age groups defined as neonatal (< 3 months), when circulating AMH is present at extremely low levels even in controls, minipuberty (> 3–18 months), and prepubertal (≥ 18 months to 10.5 years). We realize that some girls may begin puberty before age 10.5 years but think that this was not true for the DG or control girls in our study, because none showed elevated FSH; we therefore kept the age cutoff of 10.5 years to retain the maximum number of “older” DG samples in the study. Across each of the three age groups, the AMH and FSH levels in girls with DG were statistically indistinguishable from those in control girls.

Finally, although these results are certainly encouraging news for girls and women with DG, they must be interpreted with some caution. Our study group was relatively small, especially in the oldest group, and some of these girls may have experienced galactose-restricted diets, at least as infants. Additional studies with larger numbers of older girls and women with DG whose diet history is known, ascertained in an unbiased manner, as well as prospective data on the experiences of girls and women with DG entering puberty or attempting to conceive, would be especially informative.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are especially grateful to the many wonderful study volunteers and their families, without whose participation this project would have been impossible. They also thank the staff of the Emory Genetics Laboratory for their assistance with obtaining clinical laboratory discards and other members of the Fridovich-Keil laboratory, especially Emily Ryan, for their many contributions and support. Finally, the authors thank the staff members of the Reproductive Endocrine Reference Laboratory at Massachusetts General Hospital and the Yerkes Biomarker Core Laboratory at Emory (especially Joi Murphy) for assistance with the AMH and FSH analyses.

Supported by National Institutes of Health grant RO1 DK059904 (J.L.F-K.) and National Research Service Award 2 T32 DK007298-31 (J.R.B.).

Footnotes

J.R.B. has nothing to disclose. U.C. has nothing to disclose. T.J.G. has nothing to disclose. J.B.S. has nothing to disclose. M.P.E. has nothing to disclose. C.F. has nothing to disclose. K.F. has nothing to disclose. J.L.F-K. has nothing to disclose.

Presented as an abstract at the 93rd Annual Meeting of the Endocrine Society, Boston, Massachusetts, June 4–7, 2011.

References

- 1.Fridovich-Keil J, Walter J. Galactosemia. In: Valle D, Beaudet A, Vogelstein B, Kinzler K, Antonarakis S, Ballabio A, editors. The Online Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease—OMMBID. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2008. www.ommbid.com. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fernhoff PM. Duarte galactosemia: how sweet is it? Clin Chem. 2010;56:1045–6. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.147371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ficicioglu C, Hussa C, Gallagher PR, Thomas N, Yager C. Monitoring of biochemical status in children with Duarte galactosemia: utility of galactose, galactitol, galactonate, and galactose 1-phosphate. Clin Chem. 2010;56:1177–82. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2010.144097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ficicioglu C, Thomas N, Yager C, Gallagher PR, Hussa C, Mattie A, et al. Duarte (DG) galactosemia: a pilot study of biochemical and neurodevelopmental assessment in children detected by newborn screening. Mol Genet Metab. 2008;95:206–12. doi: 10.1016/j.ymgme.2008.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Powell KK, van Naarden Braun K, Singh RH, Shapira SK, Olney RS, Yeargin-Allsopp M. Long-term speech and language developmental issues among children with Duarte galactosemia. Genet Med. 2009;11:874–9. doi: 10.1097/GIM.0b013e3181c0c38d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chellakooty M, Schmidt IM, Haavisto AM, Boisen KA, Damgaard IN, Mau C, et al. Inhibin A, inhibin B, follicle-stimulating hormone, luteinizing hormone, estradiol, and sex hormone-binding globulin levels in 473 healthy infant girls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2003;88:3515–20. doi: 10.1210/jc.2002-021468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sanders RD, Spencer JB, Epstein MP, Pollak SV, Vardhana PA, Lustbader JW, et al. Biomarkers of ovarian function in girls and women with classic galactosemia. Fertil Steril. 2009;92:344–51. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2008.04.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gruijters MJ, Visser JA, Durlinger AL, Themmen AP. Anti-Mullerian hormone and its role in ovarian function. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;211:85–90. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.09.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hehenkamp WJ, Looman CW, Themmen AP, de Jong FH, Te Velde ER, Broekmans FJ. Anti-mullerian hormone levels in the spontaneous menstrual cycle do not show substantial fluctuation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2006;91:4057–63. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-0331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.La Marca A, Pati M, Orvieto R, Stabile G, Carducci Artenisio A, Volpe A. Serum antimullerian hormone levels in women with secondary amenorrhea. Fertil Steril. 2006;85:1547–9. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.10.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.la Marca A, Stabile G, Artenisio AC, Volpe A. Serum anti-mullerian hormone throughout the human menstrual cycle. Hum Reprod. 2006;21:3103–7. doi: 10.1093/humrep/del291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.la Marca A, Volpe A. Anti-mullerian hormone (AMH) in female reproduction: is measurement of circulating AMH a useful tool? Clin Endocrinol (Oxf) 2006;64:603–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2006.02533.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Visser JA, deJong FH, Laven JS, Themmen AP. Anti-mullerian hormone: a new marker for ovarian function. Reproduction. 2006;131:1–9. doi: 10.1530/rep.1.00529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Somunkiran A, Yavuz T, Yucel O, Ozdemir I. Anti-mullerian hormone levels during hormonal contraception in women with polycystic ovary syndrome. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2007;134:196–201. doi: 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tsepelidis S, Demeestere I, Delbaere A, Gervy C, Englert Y. Anti-mullerian hormone and its role in the regulation of ovarian function. Review of the literature. Rev Med Brux. 2007;28:165–71. In French. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Tsepelidis S, Devreker F, Demeestere I, Flahaut A, Gervy C, Englert Y. Stable serum levels of anti-mullerian hormone during the menstrual cycle: a prospective study in normo-ovulatory women. Hum Reprod. 2007;22:1837–40. doi: 10.1093/humrep/dem101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wachs DS, Coffler MS, Malcom PJ, Chang RJ. Serum antimullerian hormone concentrations are not altered by acute administration of follicle stimulating hormone in polycystic ovary syndrome and normal women. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:1871–4. doi: 10.1210/jc.2006-2425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hagen CP, Aksglaede L, Sorensen K, Main KM, Boas M, Cleemann L, et al. Serum levels of anti-mullerian hormone as a marker of ovarian function in 926 healthy females from birth to adulthood and in 172 Turner syndrome patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;95:5003–10. doi: 10.1210/jc.2010-0930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fridovich-Keil J, Gubbels C, Spencer J, Sanders R, Land J, Rubio-Gozalbo E. Ovarian function in girls and women with GALT-deficiency galactosemia. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2011;34:357–66. doi: 10.1007/s10545-010-9221-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guibourdenche J, Lucidarme N, Chevenne D, Rigal O, Nicolas M, Luton D, et al. Anti-mullerian hormone levels in serum from human foetuses and children: pattern and clinical interest. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2003;211:55–63. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2003.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sir-Petermann T, Marquez L, Carcamo M, Hitschfeld C, Codner E, Maliqueo M, et al. Effects of birth weight on antimullerian hormone serum concentrations in infant girls. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;95:903–10. doi: 10.1210/jc.2009-1771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Forest MG. Pituitary gonadotropin and sex steroid secretion during the first two years of life. In: Grumbach MM, editor. Control of the onset of puberty. Baltimore: Williams and Wilkins; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Grumbach MM, Gluckman Peter D. The human fetal hypothalamus and pituitary gland: the maturation of neuroendocrine mechanisms controlling the secretion of fetal pituitary growth hormone, prolactin, gonadotropins, andrenocorticotropin-related peptides, and thyrotropin. In: Tulchinsky D, Little AB, editors. Maternal-fetal endocrinology. Philadelphia: W.B. Saunders; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aso K, Koto S, Higuchi A, Ariyasu D, Izawa M, Miyamoto Igaki J, et al. Serum FSH level below 10 mIU/mL at twelve years old is an index of spontaneous and cyclical menstruation in Turner syndrome. Endocr J. 2010;57:909–13. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.k10e-092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hagen CP, Main KM, Kjaergaard S, Juul A. FSH, LH, inhibin B and estradiol levels in Turner syndrome depend on age and karyotype: longitudinal study of 70 Turner girls with or without spontaneous puberty. Hum Reprod. 2010;25:3134–41. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deq291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bosch AM, Grootenhuis MA, Bakker HD, Heijmans HS, Wijburg FA, Last BF. Living with classical galactosemia: health-related quality of life consequences. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e423–8. doi: 10.1542/peds.113.5.e423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kaufman FR, Devgan S, Donnell GN. Results of a survey of carrier women for the galactosemia gene. Fertil Steril. 1993;60:727–8. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(16)56232-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Knauff EA, Richardus R, Eijkemans MJ, Broekmans FJ, de Jong FJ, Fauser BC, et al. Heterozygosity for the classical galactosemia mutation does not affect ovarian reserve and menopausal age. Reprod Sci. 2007;14:780–5. doi: 10.1177/1933719107308614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ross GT. Follicular development: the life cycle of the follicle and puberty. In: Grumbach MM, editor. Control of the onset of puberty. Baltimore: Williams & Wilkins; 1990. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.