Abstract

Background:

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is a common sleep disorder associated with several adverse health outcomes. Given the close association between OSA and obesity, lifestyle and dietary interventions are commonly recommended to patients, but the evidence for their impact on OSA has not been systematically examined.

Objectives:

To conduct a systematic review and meta-analysis to assess the impact of weight loss through diet and physical activity on measures of OSA: apnea-hypopnea index (AHI) and oxygen desaturation index of 4% (ODI4).

Methods:

A systematic search was performed to identify publications using Medline (1948-2011 week 40), EMBASE (from 1988-2011 week 40), and CINAHL (from 1982-2011 week 40). The inverse variance method was used to weight studies and the random effects model was used to analyze data.

Results:

Seven randomized controlled trials (519 participants) showed that weight reduction programs were associated with a decrease in AHI (-6.04 events/h [95% confidence interval -11.18, -0.90]) with substantial heterogeneity between studies (I2 = 86%). Nine uncontrolled before-after studies (250 participants) showed a significant decrease in AHI (-12.26 events/h [95% confidence interval -18.51, -6.02]). Four uncontrolled before-after studies (97 participants) with ODI4 as outcome also showed a significant decrease in ODI4 (-18.91 episodes/h [95% confidence interval -23.40, -14.43]).

Conclusions:

Published evidence suggests that weight loss through lifestyle and dietary interventions results in improvements in obstructive sleep apnea parameters, but is insufficient to normalize them. The changes in obstructive sleep apnea parameters could, however, be clinically relevant in some patients by reducing obstructive sleep apnea severity. These promising preliminary results need confirmation through larger randomized studies including more intensive weight loss approaches.

Citation:

Araghi MH; Chen YF; Jagielski A; Choudhury S; Banerjee D; Hussain S; Thomas GN; Taheri S. Effectiveness of lifestyle interventions on obstructive sleep apnea (OSA): systematic review and meta-analysis. SLEEP 2013;36(10):1553-1562.

Keywords: Lifestyle Intervention, systematic review, meta-analysis, obstructive sleep apnea, obesity

INTRODUCTION

Obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) is an increasingly prevalent condition characterized by repetitive obstruction of the upper airway during sleep accompanied by episodic hypoxia, arousal, and sleep fragmentation.1 Apart from its impact on daytime alertness and cognitive function with increased risk of road and workplace accidents, OSA is associated with increased risk of cardiovascular disease and metabolic disorders.2–3 OSA is also associated with increased cardiovascular and all-cause mortality.4 Common predisposing factors for OSA include older age, male gender, craniofacial abnormalities, and, importantly, excess adiposity.5

OSA and excess adiposity often accompany each other with the prevalence of OSA being high among obese individuals, and with the majority of patients presenting with OSA being overweight or obese.6 OSA is twice as prevalent in obese compared to normal weight individuals.1,6–7 A 10% weight gain was observed to be associated with a 32% increase in the apnea-hypopnea index (AHI), a key measure for OSA, while a 10% weight loss was associated with a 26% reduction in AHI.8 While obesity is an important reversible risk factor for OSA, it has been estimated that 58% of moderate to severe OSA in adults is attributable to obesity,1 highlighting the importance of other contributory factors that impinge on airway anatomy and control. Given the increasing prevalence of obesity worldwide, the prevalence of OSA is likely to increase dramatically.

Several treatment options are available for OSA to improve airway patency during sleep. The most commonly employed treatment is continuous positive airway pressure (CPAP), which is effective in improving airway patency and AHI, and results in reduced daytime sleepiness.9 Using CPAP treatment, however, can be problematic, resulting in inadequate adherence and/or discontinuation of treatment.10 Given the issues with CPAP usage and adherence, and the important association between OSA and obesity, lifestyle change with weight reduction is a common clinical recommendation. Lifestyle change is also likely to improve the cardiometabolic abnormalities that often accompany OSA, including insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes mellitus, dyslipidemia, and hypertension.11–14

Evidence for the efficacy of lifestyle change and weight loss on OSA is available from both observational and randomized controlled clinical trials, but this evidence has not been systematically reviewed. We sought to assess the effectiveness of lifestyle loss interventions on severity of OSA. In particular, we were interested in determining the mean changes in AHI and oxygen desaturation index of 4% (ODI4) following termination of lifestyle interventions. We also tried to assess the impact of these interventions on common symptoms of OSA such as daytime sleepiness.

METHODS

Data Sources and Searches

Our study protocol was registered with International Prospective Register Of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) (Registration Number: CRD42011001511).15

A systematic search was performed to identify relevant publications using Medline (from 1948), Embase (from 1988), CINAHL (from 1983), Opengrey, OAIster, Zetoc, BioMed Central, NLM Gateway, Cochrane Library, ISRCTN, and www.clinicaltrials.gov (from database inception to April 2011). We also checked reference lists and unpublished studies. The search terms used were (“obstructive sleep apnea” or “obstructive sleep apnoea” or “sleep disordered breathing”) and (“lifestyle” or “exercise” or “weight loss” or “weight” or “diet” or “physical activity”).

Study Selection

To be eligible for inclusion, research papers had to report data on adult patients (≥ 18 years old; male and female) with confirmed diagnosed OSA (AHI ≥ 5 events/h or ODI4 ≥ 5 episodes/h) and investigated lifestyle modification interventions (defined as a comprehensive program of diet and/or exercise therapy16 without treatment with CPAP at the start of the interventions). Surgical and pharmacological interventions were excluded. Randomized and non-randomized studies that compared a lifestyle modification intervention with no intervention, usual care, or placebo were eligible for inclusion. Uncontrolled before-and-after studies were also included to provide supportive evidence given the small number of comparative studies identified.

Based on the above inclusion criteria, titles and abstracts were screened independently by two authors (AJ, SC) with access to full-text where necessary to select studies into the review. Disagreements on inclusion decisions were resolved by discussion.

Data Extraction and Quality Assessment

We used a standardized form to extract data including: citation information and study design, patients' demographic and clinical characteristics, length of weight loss intervention, length of follow-up, and change in body mass index (BMI), AHI, ODI4, and daytime sleepiness pre- and post- intervention. Extracted data were checked for accuracy by AJ and SC. Authors were contacted to provide additional data where needed.

We assessed the randomized controlled studies for methodological quality using Cochrane risk of bias tools. These studies were assessed for random sequence generation, allocation concealment, blinding (where blinding of the participants is not possible, blinding of outcome assessors and data analysts were assessed instead), incomplete outcome data, selective outcome reporting, and any other biases. We assessed uncontrolled before-and-after studies for methodological quality using relevant items from the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group (EPOC) risk of bias tool for interrupted time series studies, and items used by Chambers and colleagues17 for assessing case series. The details on methodological quality assessment of randomized controlled studies and uncontrolled before-after studies are summarized in Tables S1 and S2 in the supplemental material.

Data Synthesis and Analysis

Outcomes (AHI, ODI4, BMI, ESS) were combined using random effects model of DerSimonian and Laird,18 and expressed as weighted mean differences. Randomized controlled trials and uncontrolled before-and-after studies were analyzed separately.

For randomized controlled studies, data included in the analysis were the change from baseline to post- intervention between intervention and control groups. For uncontrolled studies, the data analyzed were the changes post intervention compared to baseline for a single group. In the latter analysis with ODI4 as the outcome, data from the intervention arm of one RCT19 were regarded as an “uncontrolled before-after studies” and were also included. The meta-analysis was performed using RevMan 5.1 (Update Software, 2011). In order to weight the studies, the inverse variance method was used.20 Meta-regression of data from before-after studies and intervention arms of RCTs was carried out using restricted maximum likelihood estimators (REML) to examine the association between reduction in weight and change in AHI and also between baseline AHI and change in AHI. We assessed the presence of potential publication bias using Dear and Begg's test21 implemented by “select-Meta” package in R.22 Statistical heterogeneity was assessed using the Chi2 test and the I2 statistic, with I2 greater than 50% indicating at least moderate heterogeneity. A P value < 0.05 was considered to be statistical significance.

RESULTS

Study Characteristics

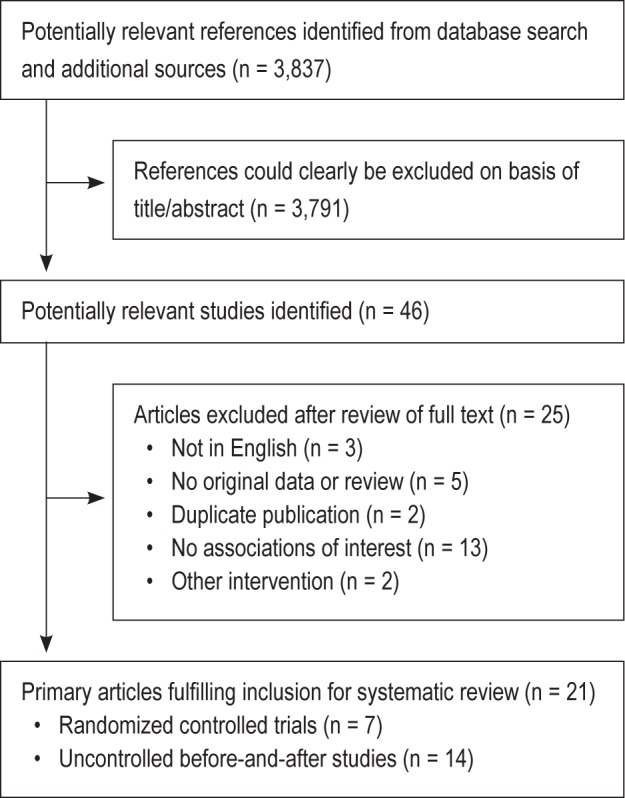

A total of 3,837 references were retrieved by the search. The flow of the studies is shown in Figure 1. Review of the titles and abstracts allowed for the exclusion of 3,791 publications. We reviewed the full text of 46 studies that were potentially suitable for inclusion in the systematic review. After excluding duplicate studies and those that did not meet the inclusion criteria, we identified 21 studies representing 893 patients for inclusion. We included 7 randomized controlled trials14,23–28 with a total of 519 participants, and 14 uncontrolled before-and-after studies19,29–41 with a total number of 374 participants.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of study selection.

All studies assessed the effect of weight loss through lifestyle modification interventions such as diet, exercise, or using both methods on patients with OSA. The length of the intervention varied from 4 weeks to 24 months. Descriptive data for the included studies are presented in Tables S3 and S4 in the supplemental material.

Most studies were performed in Finland and the Unites States. The rest of the studies were from Sweden, Spain, Australia, Canada, and Brazil. The sample size varied from 8 to 264 individuals, with an average age of the participants being 49 years. Despite the attempt to contact authors to provide data, we could not obtain data regarding BMI change for one randomized controlled study.24 With the agreement with the independent reviewers, the observational study by Johansson and colleagues32 was recognized as an independent study from their previous randomized controlled study14 and was eligible for inclusion.

A very-low calorie diet ([VLCD] intake < 800 kcal/d) intervention was used by 13 studies.14,19,24-25,28,30-32,34-36,38,42 Four studies used combined interventions23,29,33,39 including VLCD with either exercise or cognitive behavioral therapy. Exercise intervention was used by 4 studies.26–27,37,41 Five studies reported ODI4 as the outcome measure19,30,33–35; 6 studies reported both AHI and ODI414,23,26,32,36,40; and 10 studies only reported AHI as the outcome.24–25,28–29,31–32,37–39,41

The baseline BMI average varied from 29.0 to 54.6 kg/m2. For the sleep outcome, AHI varied from 10/h to 66.5/h and for ODI4 varied from 30/h to 51/hour.

Effect of Lifestyle Intervention on Obstructive Sleep Apnea

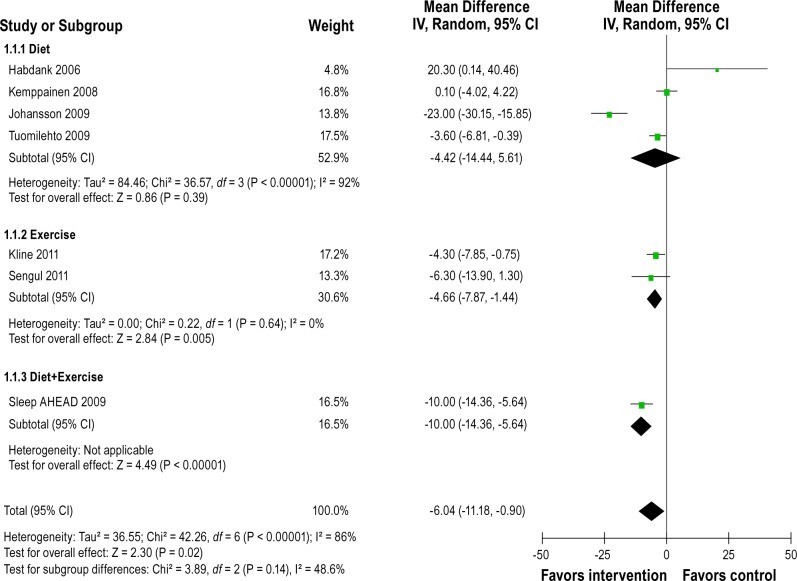

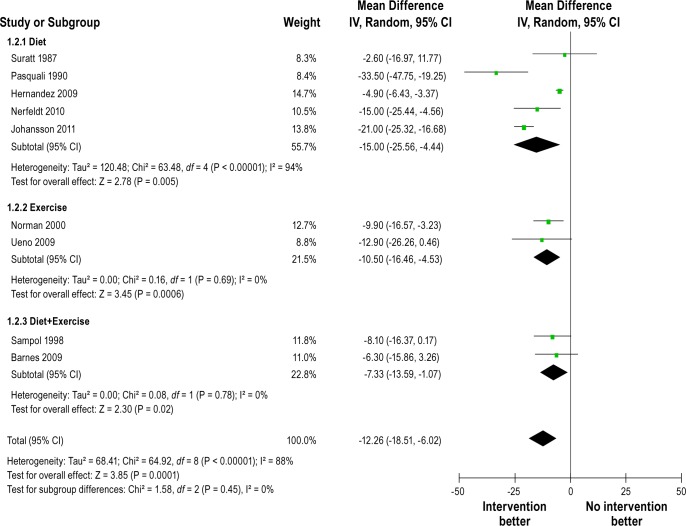

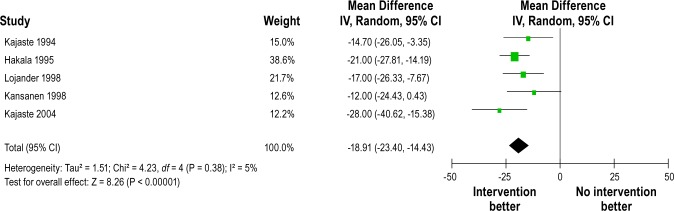

Figure 2 shows the forest plot of differences in AHI changes between intervention and control groups after intervention in randomized controlled studies. The pooled mean reduction in AHI was -6.04/h (-11.18 to -0.90). Heterogeneity between studies was high (Q = 42.26, df = 6, P < 0.00001, I2 = 86%). Figure 3 shows forest plot of AHI changes after intervention from before-and-after studies. The pooled mean reduction in AHI was -12.26/h (-18.51 to -6.02). Substantial heterogeneity was observed between studies (Q = 64.92, df = 8, P < 0.00001, I 2 = 88%). All 5 uncontrolled studies with ODI4 outcome reported significant reduction in amount of oxygen desaturation after the intervention. Figure 4 shows forest plot of ODI4 changes after intervention in uncontrolled studies. The pooled mean reduction in ODI4 was -18.91 (-23.40 to -14.43). There was little heterogeneity between studies (Q = 4.23, df = 4, P = 0.38, I2 = 5%).

Figure 2.

Forest plot of differences in AHI (events/h) changes between intervention and control groups after intervention in randomized controlled studies. IV, inverse varience method; Random, random effects model; CI, confidence intervals.

Figure 3.

Forest plot of AHI (events/h) changes after intervention in uncontrolled before-after studies. IV, inverse varience method; Random, random effects model; CI, confidence intervals.

Figure 4.

Forest plot of ODI4 (episodes/h) changes after intervention in uncontrolled before-and-after studies. IV, inverse varience method; Random, random effects model; CI, confidence intervals.

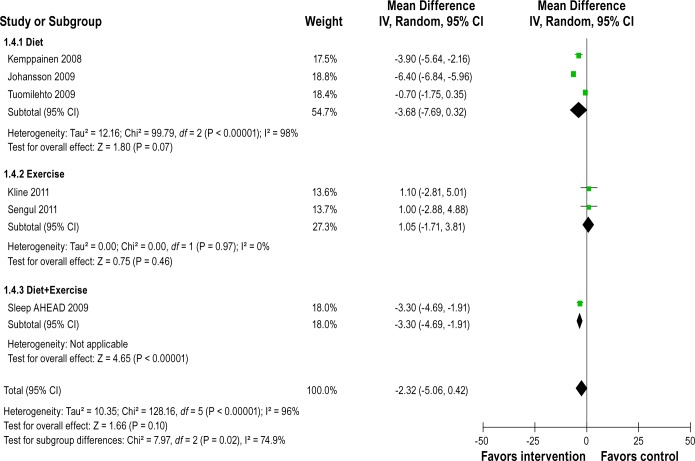

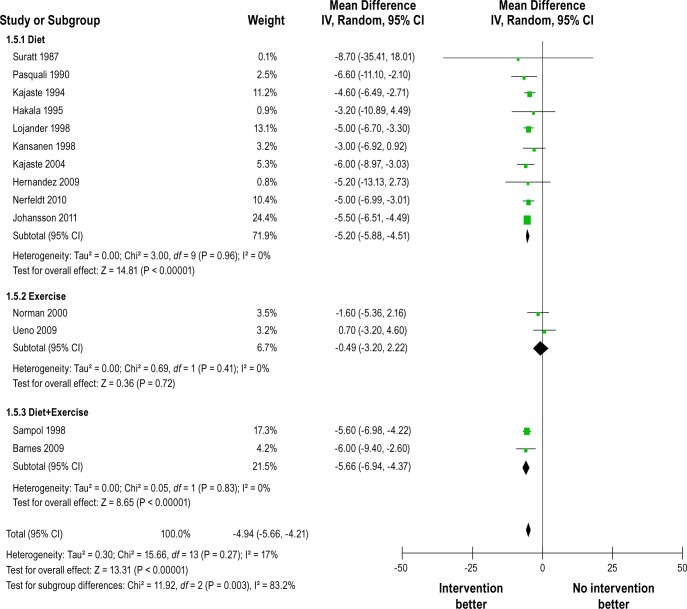

Effect of Lifestyle Intervention on Body Mass Index

Figure 5 shows forest plot of differences in BMI changes between intervention and control groups after intervention in randomized controlled studies. They reported a reduction in BMI after the interventions. The pooled mean change in BMI was -2.32 kg/m2 (-5.06 to 0.42), but heterogeneity between studies was very high (Q = 128.16, df = 5, P < 0.0001, I2 = 96%). Figure 6 shows BMI changes after intervention in uncontrolled before-and-after studies. They also reported significant reduction in BMI. The pooled mean change in BMI was -4.94 kg/m2 (-5.66 to -4.21). No heterogeneity was observed within each type of lifestyle interventions (e.g., diet, exercise, and both combined), but significant reduction in BMI appeared to have been observed only in diet or combined interventions and not in exercise interventions (test for differences between subgroups, P = 0.003).

Figure 5.

Forest plot of differences in BMI (kg/m2) changes between intervention and control groups after intervention in randomized controlled studies. IV, inverse varience method; Random, random effects model; CI, confidence intervals.

Figure 6.

Forest plot of BMI (kg/m2) changes after intervention in uncontrolled before-and-after studies. IV, inverse varience method; Random, random effects model; CI, confidence intervals.

Effect of Lifestyle Intervention on Daytime Sleepiness

Data on the effect of weight loss interventions on common OSA symptoms was markedly lacking across studies. For the meta-analysis, we presented the results from RCTs14,27–28 first and then presented the results from before-after studies29,32,36 as a subgroup. Figure S1 in the supplemental material shows the forest plot of differences in Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) across RCTs and before-after studies. The pooled mean reduction of ESS from RCTS was -1.04 (-2.31 to 0.23) and no heterogeneity was found between studies (Q = 2.14, df = 2, P = 0.11, I 2 = 0%). The pooled mean reduction of ESS from before-after studies was -2.87 (-4.30, -1.44); small heterogeneity was found between studies (Q = 3.16, df = 2, P = 0.21, I2 = 37%).

Sensitivity Analysis and Investigation of Heterogeneity

We re-run the meta-analysis excluding studies judged to be of lower quality. The overall findings remained unchanged in the sensitivity analysis.

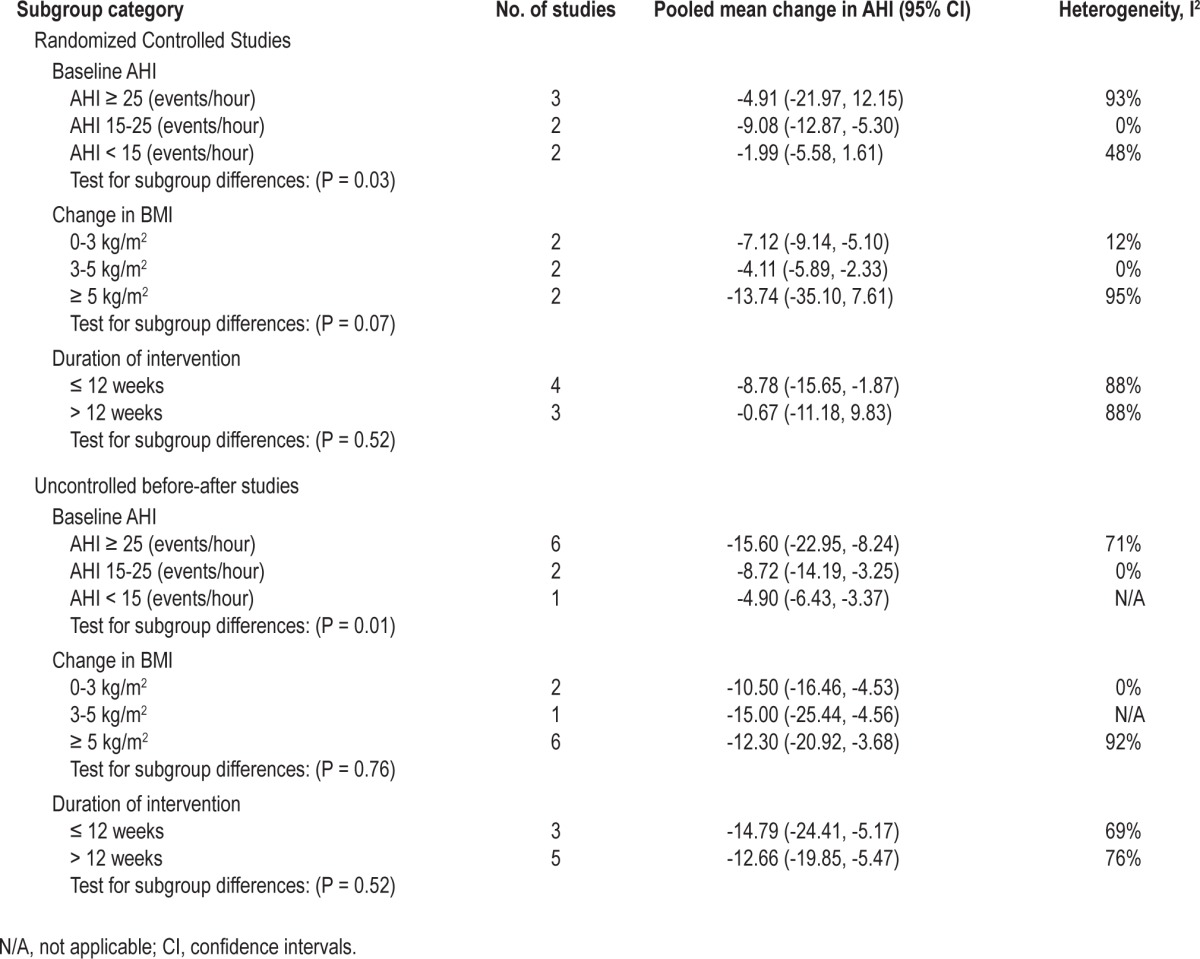

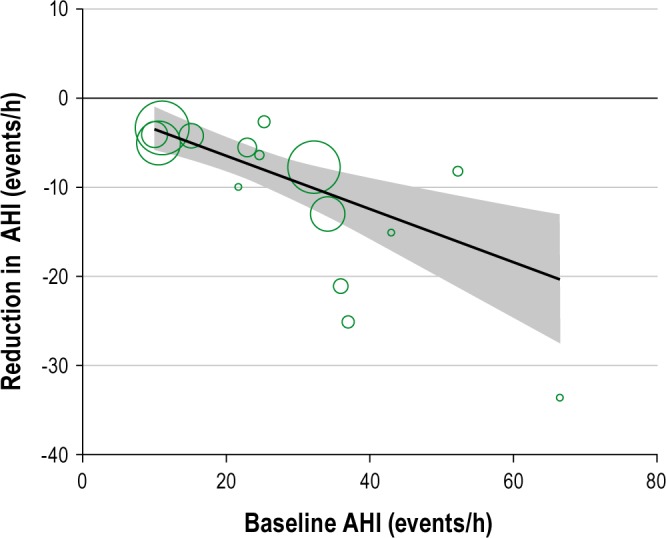

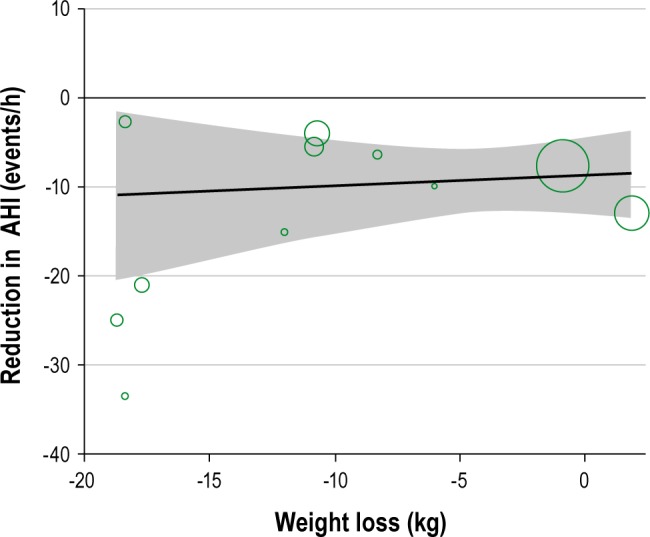

Substantial heterogeneity was observed between studies in the meta-analyses of AHI and BMI. We attempted to explore the source of heterogeneity by performing subgroup analyses and stratified the studies according to the baseline level of AHI (> 25, 15-25, < 15 events/h), change in BMI (0-3, 3-5, ≥ 5 kg/ m 2), and duration of intervention, (≤ 12 weeks, > 12 weeks) (Table 1). The results indicate that the greatest source of heterogeneity comes from studies with higher AHI at the baseline and also with greater change in the BMI. Meta-regression of the studies suggested positive correlation between baseline AHI and change in AHI (r = -0.41, P = 0.001; Figure 7) and between weight loss and change in AHI (r = 0.56, P = 0.186) although the latter did not reach statistical significance, partly due to the small number of studies (Figure 8).

Table 1.

The result of subgroup analysis

Figure 7.

Meta-regression of baseline AHI against reduction AHI (the shaded area represents the 95% confidence intervals).

Figure 8.

Meta-regression of reduction in weight against reduction in AHI (the shaded area represent the 95% confidence intervals).

Assessment of Publication Bias

We assessed the presence of potential publication bias using Dear and Begg's test.21 There was no evidence of publication bias across 21 studies. We computed a simulation-based P-value to assess the null hypothesis of no selection bias across studies; the overall computed P-value was 0.76, which strongly supports our previous indication. Using estimated weight function, which is a proportional to the probability that a study is published introduced by Dear and Begg,21 showed random configuration (no observable trend) of the estimated weight function, which visually confirmed the lack of bias across the studies. Using Dear and Begg, the estimated weight function for our study was as follows: 0.330, 0.088, 0.359, 0.999, 0.179, 0.385, 0.174, 0.194, 0.153, 0.999, and 0.195.

DISCUSSION

The increasing prevalence of OSA, driven by increasing levels of obesity necessitates an approach to treatment that not only addresses the symptoms of OSA, but also the obesity that contributes to OSA development and severity.1 Addressing obesity will also improve cardiometabolic outcomes that frequently accompany OSA. Bariatric surgery is recommended for those with the greatest severity of obesity and accompanying comorbidities. Bariatric surgery, however, is not without risk, is not widely available, and its long-term outcomes are unknown. For the majority of patients with OSA, lifestyle change and weight loss are recommended by guidelines,43 but the evidence base for this recommendation remains unexamined through systematic review and meta-analysis.

This study provides a systematic review of the literature and quantitative assessments of the effect of the non-surgical and non-pharmaceutical interventions on OSA. Based on the 21 studies included representing 893 patients with OSA, we detected a reduction in AHI after completion of the interventions. Subgroup analysis showed that the great source of the heterogeneity comes from the studies with severe OSA at baseline, and meta-regression indicated a linear relationship between baseline AHI and reduction in AHI. While the latter suggests a greater intervention effect in patients with more severe OSA, possible influence of regression to the mean cannot be ruled out,44 which is a statistical feature that can be caused due to enrolment of participants in trials based on a single baseline OSA evaluation and included individuals with OSA defined at varying in terms of severity across trials.

Our results indicated that interventions that employed physical activity alone were not successful in reducing AHI compared to dietary approaches. A combination of diet and physical activity, however, resulted in significant reductions in AHI. While physical activity alone may not be as effective for weight loss as dietary interventions, it has a role in weight loss maintenance. One of the biggest issues with lifestyle weight loss intervention is sustainability of reduced weight. Data on longer follow-up periods are extensively lacking. Tuomilehto and colleagues28 indicated that after one-year follow-up, the average weight loss of their participants was 11 kg. Kajaste and colleagues19 also indicated that at 6-month follow-up, the mean reduction of weight loss was 19 kg and at 2-year follow-up was 13 kg, which demonstrated that the participants were enthusiastic to sustain to the changes. The result of the 2-year dietary weight loss intervention by Nerfeldt and colleagues36 indicated that sustained improvement in OSA severity was acquired following long-term weight loss maintenance. Similar improvements were obtained following a 1-year weight loss program by Johansson and colleagues.14 Using anti-obesity medication could be considered as a promising approach to achieve weight loss maintenance in long term.45–47 Thus, more long-term studies are required to examine the effectiveness of such treatment schemes in improvement of sleep apnea.

The meta-analysis of seven randomized controlled trials involving 519 participants detected a reduction in AHI after completion of the intervention. Substantial heterogeneity was observed across studies. We explored the sources of heterogeneity by performing subgroup analysis; we categorized the studies according to their baseline AHI, change in BMI, and duration of the intervention. The results showed that a great source of heterogeneity originated from studies with baseline AHI > 25/hour and higher change in BMI ≥ 5 kg/m2. The pooled estimate of these studies also showed a reduction in BMI. The meta-analysis of fourteen uncontrolled before-and-after studies involving 374 participants showed a reduction in AHI and ODI4. We observed mild heterogeneity across studies with AHI as their OSA outcome. The source of heterogeneity was assessed by performing subgroup analysis. The results showed that great source of heterogeneity originated from studies with baseline AHI > 25/hour and higher change in BMI ≥ 5 kg/m.2 The pooled estimate of these studies also showed a reduction in BMI.

Overall, few studies demonstrated normalization of AHI with the interventions employed. For the seven randomized controlled studies that have reported AHI as their outcome, only two studies14,23 attained a reduction in AHI more than 10/ hour. In nine uncontrolled studies that also reported AHI as their outcome, only three studies32,36,38 reported a reduction in AHI more than 10/hour. The significant reduction in ODI4 has been achieved by all five uncontrolled studies. It seems that the interventions may have greater impact on reduction of ODI4 than AHI. Apart from OSA, obesity has effects on ventilation, which may explain the greater effect observed with ODI4.

Excessive daytime sleepiness is a common symptom of OSA. Few studies—three randomized controlled trials14,27–28 and three before-after studies29,32,36—examined the impact of lifestyle intervention on excessive daytime sleepiness or other symptoms of OSA. The range of changes in ESS across the studies varied from 1.2 to 4. It should be taken into account that OSA symptoms are not necessarily related to OSA severity,48 and lack of data on subjective measurement of daytime sleepiness does not minimize the importance of recognition of adverse consequences of untreated OSA.48–49 Future studies should include assessment of OSA symptoms and quality of life using validated instruments.

Weight has a significant impact on OSA status.1 The mechanisms are complex, with many factors contributing to the relationship between obesity and OSA. These include anatomical narrowing of the upper airway and physiological alterations in airway control.40 Additionally, obesity affects ventilation through increased abdominal pressure secondary to visceral adiposity accompanied by impaired diaphragmatic and ribcage movement. A number of RCTs14,23,28 investigating the impact of weight loss on severity of OSA have reported that a mean range of weight loss by 10% to 16% can reduce AHI by 20% to 50%. Three uncontrolled before-after studies29,36,38 on weight loss also reported that the average weight reduction by 13% and 30% is associated by decrease in AHI by 10% to 50%. A prospective analysis from the Wisconsin Sleep Cohort8 demonstrated that there is a dose-response relationship between weight and AHI. Although the results from these studies suggest that weight reduction can be beneficial in OSA treatment, the lack of control groups, randomized design, and sufficient sample size provide less reliable evidence. Thus, it is important to interpret the findings from such studies with caution. The exact mechanism underlying the effect of weight loss is yet to be confirmed.

The results from the studies with physical activity weight loss shows that they did not report any significant change in body weight and BMI. It might indicate that improvement in OSA might goes beyond the weight loss.50 It can be argued that the interventions have an impact on alteration of metabolic activity of central fat tissue, which contributes to development of OSA.51 There are several hypotheses regarding the impact of increased physical activity and reduced AHI.50–52 It has been previously suggested that thermogenic enhancement, energy alterations and body reinstatement are effectively contribute to changes in sleep-awake cycle.53 It has been found that exercise training normalizes chemoreceptor sensitivity in athletes, which can improve breathing.54 Netzer and colleagues suggested that increased physical activity was associated with improvement in muscle tonus of upper airways.54 They did not detect any significant changes in body weight.54 In a similar study, exercise training found to be associated with enhanced potency of pharyngeal muscles.55 The final hypothesis suggests that possible cause of decrease in AHI is increased strength of tongue muscles as a result of inspiratory and expiratory pressure following an increase in physical activity.56

Compared to bariatric surgery, lifestyle weight loss interventions such as diet and physical activity—with lower cost and fewer adverse outcomes—are a viable treatment option for OSA. Based on current evidence examined, however, these interventions, are unlikely to normalize breathing during sleep. Nevertheless, a sufficient change in AHI is likely to reduce the severity of OSA, which will, in turn, reduce its cardiovascular consequences.57 The meta-regression carried out, although not statistically significant (most likely due to lack of statistical power) shows that the greatest weight loss is associated with greatest improvement in AHI. At least 5%, and preferably 10%, weight loss is required to be beneficial to making the greatest impact on OSA parameters and cardiovascular health.14 Importantly, those with greatest AHI at baseline, who are at greatest risk for cardiovascular consequences of OSA, are most likely to benefit from the lifestyle interventions employed.

The most dramatic weight loss has been observed with bariatric surgery and interventions employing very low calorie diets (intake < 800 kcal/d).58–60 A systematic review of randomized weight loss trials with a minimum follow-up of a year suggested that VLCD achieved up to 10% weight reduction from baseline after a year, compared with pharmacologic treatment (8%).61 Obesity is a modifiable risk factor for OSA,62 and epidemiological studies have shown that approximately 90% of diabetic obese patients had OSA.63 The long-term outcomes of bariatric surgery and VLCD interventions are unclear, with both being associated with varying degrees of weight regain and potentially the resurgence of OSA.64 The findings from studies employing VLCDs, however, demonstrate that this approach may be useful clinically for reducing measures of OSA.

Our study has several limitations, particularly that the data analyzed are limited to those reported in publications. The quality of included studies was generally poor, and there are many inherent weaknesses in uncontrolled studies, such as temporal trends unrelated to the intervention and regression to the mean. Consequently, while the results of our meta-analysis showed pattern of improvement of OSA parameter outcome in OSA patients, the significant heterogeneity between studies in some of the outcomes and potential biases in the evidence mandate a cautious interpretation of the findings and call for further evidence of higher quality.

In conclusion, lifestyle weight loss interventions cannot be accepted as a curative treatment for sleep apnea. It is well known that weight reduction as a treatment for normalization of sleep among OSA patients is more difficult than weight gain prevention among these individuals. Lifestyle weight loss interventions can be used in early stage of the disease. There is a now need for larger randomized controlled trials aiming for at least 10% weight loss with long-term follow-up to determine the efficacy of lifestyle interventions for OSA. In the meantime, given that there are cardiometabolic benefits of weight loss, there is a need for a more proactive role in treating obesity among the OSA patient population.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

This was not an industry supported study. Dr. Taheri has received grant support from ResMed, Novo Nordisk, and Lilly. The other authors have indicated no financial conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Marzieh Hosseini Araghi, Yen-Fu Chen, Alison Jagielski, Sopna Choudhury, Shakir Hussain, and Shahrad Taheri have received funding from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) through the Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care for Birmingham and Black Country (CLAHRC-BBC) program. The views expressed in this publication are not necessarily those of the NIHR, the Department of Health, NHS South Birmingham, University of Birmingham or the CLAHRC BBC Theme 8 Management/Steering Group.

Footnotes

A commentary on this article appears in this issue on page 1419.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

Quality assessment of randomized controlled trials

Quality assessment of uncontrolled before-after studies

Key characteristics of included studies

Key characteristics of study participants

Forest plot of Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) changes after intervention across the studies. IV, inverse varience method; Random, random effects model; CI, confidence intervals.

REFERENCES

- 1.Young T, Peppard PE, Taheri S. Excess weight and sleep-disordered breathing. J Appl Physiol. 2005;99:1592–9. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00587.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Somers VK, White DP, Amin R, et al. Sleep apnea and cardiovascular disease: an American Heart Association/American College of Cardiology Foundation Scientific Statement from the American Heart Association Council for High Blood Pressure Research Professional Education Committee, Council on Clinical Cardiology, Stroke Council, and Council on Cardiovascular Nursing. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2008;52:686–717. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2008.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tasali E, Ip MS. Obstructive sleep apnea and metabolic syndrome: alterations in glucose metabolism and inflammation. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:207–17. doi: 10.1513/pats.200708-139MG. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marshall NS, Wong KK, Liu PY, Cullen SR, Knuiman MW, Grunstein RR. Sleep apnea as an independent risk factor for all-cause mortality: the Busselton Health Study. Sleep. 2008;31:1079–85. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Young T, Skatrud J, Peppard PE. Risk factors for obstructive sleep apnea in adults. JAMA. 2004;291:2013–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.16.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rajala R, Partinen M, Sane T, Pelkonen R, Huikuri K, Seppalainen AM. Obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome in morbidly obese patients. J Intern Med. 1991;230:125–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2796.1991.tb00419.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lettieri CJ, Eliasson AH, Andrada T, Khramtsov A, Raphaelson M, Kristo DA. Obstructive sleep apnea syndrome: are we missing an at-risk population? J Clin Sleep Med. 2005;1:381–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Peppard PE, Young T, Palta M, Dempsey J, Skatrud J. Longitudinal study of moderate weight change and sleep-disordered breathing. JAMA. 2000;284:3015–21. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.23.3015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Veasey SC, Guilleminault C, Strohl KP, Sanders MH, Ballard RD, Magalang UJ. Medical therapy for obstructive sleep apnea: a review by the Medical Therapy for Obstructive Sleep Apnea Task Force of the Standards of Practice Committee of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. Sleep. 2006;29:1036–44. doi: 10.1093/sleep/29.8.1036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sawyer AM, Gooneratne NS, Marcus CL, Ofer D, Richards KC, Weaver TE. A systematic review of CPAP adherence across age groups: clinical and empiric insights for developing CPAP adherence interventions. Sleep Med Rev. 2011;15:343–56. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2011.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grunstein RR, Stenlof K, Hedner JA, Peltonen M, Karason K, Sjostrom L. Two year reduction in sleep apnea symptoms and associated diabetes incidence after weight loss in severe obesity. Sleep. 2007;30:703–10. doi: 10.1093/sleep/30.6.703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Loube DI, Loube AA, Mitler MM. Weight loss for obstructive sleep apnea: the optimal therapy for obese patients. J Am Diet Assoc. 1994;94:1291–5. doi: 10.1016/0002-8223(94)92462-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Nahmias J, Kirschner M, Karetzky MS. Weight loss and OSA and pulmonary function in obesity. N J Med. 1993;90:48–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johansson K, Neovius M, Lagerros YT, et al. Effect of a very low energy diet on moderate and severe obstructive sleep apnoea in obese men: a randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2009;339:b4609. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b4609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.International Prospective Register Of Systematic Reviews. The impact of lifestyle interventions and weight loss on obstructive sleep apnoea: a systematic review and meta-analysis (Registeration Number: CRD42011001511) 2011 [cited 2011 24/01/2012] Available from: http://www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/

- 16.Douglas NJ. Systematic review of the efficacy of nasal CPAP. Thorax. 1998;53:414–5. doi: 10.1136/thx.53.5.414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chambers D, Rodgers M, Woolacott N. Not only randomized controlled trials, but also case series should be considered in systematic reviews of rapidly developing technologies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2009;62:1253–60. e4. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2008.12.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DerSimonian R, Laird N. Meta-analysis in clinical trials. Control Clin Trials. 1986;7:177–88. doi: 10.1016/0197-2456(86)90046-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kajaste S, Brander PE, Telakivi T, Partinen M, Mustajoki P. A cognitive-behavioral weight reduction program in the treatment of obstructive sleep apnea syndrome with or without initial nasal CPAP: a randomized study. Sleep Med. 2004;5:125–31. doi: 10.1016/j.sleep.2003.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sutton A, Abrams K, Jones D, Sheldon T, Song F. Chichester: Wiley; 2000. Methods for meta-analysis in medical research; p. 58. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dear KBG, Begg CB. An approach for assessing publication bias prior to performing a meta-analysis. Statistical Science. 1992;7:237–45. [Google Scholar]

- 22.R Development Core Team. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2012. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foster GD, Borradaile KE, Sanders MH, et al. A randomized study on the effect of weight loss on obstructive sleep apnea among obese patients with type 2 diabetes: the Sleep AHEAD study. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:1619–26. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.266. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Habdank K, Paul T, Sen M, Ferguson AK. Randomized Controlled Trial Evaluating the Effectiveness of a Weight Loss Strategy in Overweight Patients with Obstructive Sleep Apnea. American Thoracic Society. 2006:A868. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kemppainen T, Ruoppi P, Seppa J, et al. Effect of weight reduction on rhinometric measurements in overweight patients with obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Rhinol. 2008;22:410–5. doi: 10.2500/ajr.2008.22.3203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kline CE, Crowley EP, Ewing GB, et al. The effect of exercise training on obstructive sleep apnea and sleep quality: a randomized controlled trial. Sleep. 2011;34:1631–40. doi: 10.5665/sleep.1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sengul YS, Ozalevli S, Oztura I, Itil O, Baklan B. The effect of exercise on obstructive sleep apnea: a randomized and controlled trial. Sleep Breath. 2011;15:49–56. doi: 10.1007/s11325-009-0311-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tuomilehto HP, Seppa JM, Partinen MM, et al. Lifestyle intervention with weight reduction: first-line treatment in mild obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2009;179:320–7. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200805-669OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Barnes M, Goldsworthy UR, Cary BA, Hill CJ. A diet and exercise program to improve clinical outcomes in patients with obstructive sleep apnea--a feasibility study. J Clin Sleep Med. 2009;5:409–15. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hakala K, Mustajoki P, Aittomaki J, Sovijarvi AR. Effect of weight loss and body position on pulmonary function and gas exchange abnormalities in morbid obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1995;19:343–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hernandez TL, Ballard RD, Weil KM, et al. Effects of maintained weight loss on sleep dynamics and neck morphology in severely obese adults. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009;17:84–91. doi: 10.1038/oby.2008.485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Johansson K, Hemmingsson E, Harlid R, et al. Longer term effects of very low energy diet on obstructive sleep apnoea in cohort derived from randomised controlled trial: prospective observational follow-up study. BMJ. 2011;342:d3017. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d3017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kajaste S, Telakivi T, Mustajoki P, Pihl S, Partinen M. Effects of a cognitive-behavioural weight loss programme on overweight obstructive sleep apnoea patients. J Sleep Res. 1994;3:245–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2869.1994.tb00138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kansanen M, Vanninen E, Tuunainen A, et al. The effect of a very low-calorie diet-induced weight loss on the severity of obstructive sleep apnoea and autonomic nervous function in obese patients with obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. Clin Physiol. 1998;18:377–85. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2281.1998.00114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lojander J, Mustajoki P, Ronka S, Mecklin P, Maasilta P. A nurse-managed weight reduction programme for obstructive sleep apnoea syndrome. J Intern Med. 1998;244:251–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1998.00387.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nerfeldt P, Nilsson BY, Mayor L, Udden J, Friberg D. A two-year weight reduction program in obese sleep apnea patients. J Clin Sleep Med. 2010;6:479–86. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Norman JF, Von Essen SG, Fuchs RH, McElligott M. Exercise training effect on obstructive sleep apnea syndrome. Sleep Res Online. 2000;3:121–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pasquali R, Colella P, Cirignotta F, et al. Treatment of obese patients with obstructive sleep apnea syndrome (OSAS): effect of weight loss and interference of otorhinolaryngoiatric pathology. Int J Obes. 1990;14:207–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sampol G, Munoz X, Sagales MT, et al. Long-term efficacy of dietary weight loss in sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome. Eur Respir J. 1998;12:1156–9. doi: 10.1183/09031936.98.12051156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Suratt PM, McTier RF, Findley LJ, Pohl SL, Wilhoit SC. Changes in breathing and the pharynx after weight loss in obstructive sleep apnea. Chest. 1987;92:631–7. doi: 10.1378/chest.92.4.631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ueno LM, Drager LF, Rodrigues AC, et al. Effects of exercise training in patients with chronic heart failure and sleep apnea. Sleep. 2009;32:637–47. doi: 10.1093/sleep/32.5.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Suratt PM, McTier RF, Findley LJ, Pohl SL, Wilhoit SC. Effect of very-low-calorie diets with weight loss on obstructive sleep apnea. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;56:182S–4S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/56.1.182S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Scottish Intercollegiate Guidelines Network (SIGN) Management of obstructive sleep apnoea/hypopnoea syndrome in adults (guideline no. 73) 2003 [cited; Available from: www.sign.ac.uk. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Barnett AG, van der Pols JC, Dobson AJ. Regression to the mean: what it is and how to deal with it. Int J Epidemiol. 2005;34:215–20. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Apfelbaum M, Vague P, Ziegler O, Hanotin C, Thomas F, Leutenegger E. Long-term maintenance of weight loss after a very-low-calorie diet: a randomized blinded trial of the efficacy and tolerability of sibutramine. Am J Med. 1999;106:179–84. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(98)00411-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mathus-Vliegen EM. Long-term maintenance of weight loss with sibutramine in a GP setting following a specialist guided very-low-calorie diet: a double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel group study. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2005;59(Suppl 1):S31–8. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602172. discussion S9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Richelsen B, Tonstad S, Rossner S, et al. Effect of orlistat on weight regain and cardiovascular risk factors following a very-low-energy diet in abdominally obese patients: a 3-year randomized, placebo-controlled study. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:27–32. doi: 10.2337/dc06-0210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Dixon JB, Dixon ME, Anderson ML, Schachter L, O'Brien PE. Daytime sleepiness in the obese: not as simple as obstructive sleep apnea. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007;15:2504–11. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Young T, Blustein J, Finn L, Palta M. Sleep-disordered breathing and motor vehicle accidents in a population-based sample of employed adults. Sleep. 1997;20:608–13. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.8.608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Santos RV, Tufik S, De Mello MT. Exercise, sleep and cytokines: is there a relation? Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11:231–9. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2007.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vgontzas AN, Bixler EO, Chrousos GP. Sleep apnea is a manifestation of the metabolic syndrome. Sleep Med Rev. 2005;9:211–24. doi: 10.1016/j.smrv.2005.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Driver HS, Taylor SR. Exercise and sleep. Sleep Med Rev. 2000;4:387–402. doi: 10.1053/smrv.2000.0110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Youngstedt SD, O'Connor PJ, Dishman RK. The effects of acute exercise on sleep: a quantitative synthesis. Sleep. 1997;20:203–14. doi: 10.1093/sleep/20.3.203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Netzer N, Lormes W, Giebelhaus V, et al. [Physical training of patients with sleep apnea] Pneumologie. 1997;51(Suppl 3):779–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Giebelhaus V, Strohl KP, Lormes W, Lehmann M, Netzer N. Physical Exercise as an Adjunct Therapy in Sleep Apnea-An Open Trial. Sleep Breath. 2000;4:173–6. doi: 10.1007/s11325-000-0173-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.O'Donnell DE, McGuire M, Samis L, Webb KA. General exercise training improves ventilatory and peripheral muscle strength and endurance in chronic airflow limitation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;157:1489–97. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.157.5.9708010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Milleron O, Pilliere R, Foucher A, et al. Benefits of obstructive sleep apnoea treatment in coronary artery disease: a long-term follow-up study. Eur Heart J. 2004;25:728–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ehj.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Lettieri CJ, Eliasson AH, Greenburg DL. Persistence of obstructive sleep apnea after surgical weight loss. J Clin Sleep Med. 2008;4:333–8. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Sjostrom L, Lindroos AK, Peltonen M, et al. Lifestyle, diabetes, and cardiovascular risk factors 10 years after bariatric surgery. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:2683–93. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Fritscher LG, Mottin CC, Canani S, Chatkin JM. Obesity and obstructive sleep apnea-hypopnea syndrome: the impact of bariatric surgery. Obes Surg. 2007;17:95–9. doi: 10.1007/s11695-007-9012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Franz MJ, VanWormer JJ, Crain AL, et al. Weight-loss outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis of weight-loss clinical trials with a minimum 1-year follow-up. J Am Diet Assoc. 2007;107:1755–67. doi: 10.1016/j.jada.2007.07.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Punjabi NM. The epidemiology of adult obstructive sleep apnea. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2008;5:136–43. doi: 10.1513/pats.200709-155MG. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Foster GD, Sanders MH, Millman R, et al. Obstructive sleep apnea among obese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:1017–9. doi: 10.2337/dc08-1776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Douketis JD, Macie C, Thabane L, Williamson DF. Systematic review of long-term weight loss studies in obese adults: clinical significance and applicability to clinical practice. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005;29:1153–67. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Quality assessment of randomized controlled trials

Quality assessment of uncontrolled before-after studies

Key characteristics of included studies

Key characteristics of study participants

Forest plot of Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS) changes after intervention across the studies. IV, inverse varience method; Random, random effects model; CI, confidence intervals.