Abstract

Object

Although several clinical trials utilizing the adeno-associated virus (AAV) type 2 serotype 2 (2/2) are now underway, it is unclear whether this particular serotype offers any advantage over others in terms of safety or efficiency when delivered directly to the CNS.

Methods

Recombinant AAV2–green fluorescent protein (GFP) serotypes 2/1, 2/2, 2/5, and 2/8 were generated following standard triple transfection protocols (final yield 5.4 × 1012 particles/ml). A total of 180 μl of each solution was stereotactically infused, covering the entire rostrocaudal extent of the caudoputamen in 4 rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) (3.0 ± 0.5 kg). After 6 weeks’ survival, the brain was formalin fixed, cut at 40 μm, and stained with standard immunohistochemistry for anti-GFP, anticaspase-2, and cell-specific markers (anti–microtubule-associated protein-2 for neurons and anti–glial fibrillary acidic protein for glia). Unbiased stereological counting methods were used to determine cell number and striatal volume.

Results

The entire striatum of each animal contained GFP-positive cells with significant labeling extending beyond the borders of the basal ganglia. No ischemic/necrotic, hemorrhagic, or neoplastic change was observed in any brain. Total infusate volumes were similar across the 4 serotypes. However, GFP-labeled cell density was markedly different. Adeno-associated virus 2/1, 2/2, and 2/5 each labeled < 8000 cells/mm3, whereas serotype 8 labeled > 21,000 cells, a 3- to 4-fold higher transduction efficiency. On the other hand, serotype 8 also labeled neurons and glia with equal affinity compared with neuronal specificities > 89% for the other serotypes. Moderate caspase-2 colabeling was noted in neurons immediately around the AAV2/1 injection tracts, but was not seen above the background anywhere in the brain following injections with serotypes 2, 5, or 8.

Conclusions

Intrastriatal delivery of AAV2 yields the highest cell transduction efficiencies but lowest neuronal specificity for serotype 8 when compared with serotypes 1, 2, and 5. Only AAV2/1 revealed significant caspase-2 activation. Careful consideration of serotype-specific differences in AAV2 neurotropism, transduction efficiency, and potential toxicity may affect future human trials.

Keywords: adeno-associated virus, apoptosis, convection-enhanced delivery, gene therapy, nonhuman primate

Adeno-associated virus type 2 is an attractive vector for CNS gene therapy because of its transduction characteristics, persistence in nondividing cells, lack of histological toxicity, and established safety in clinical trials.17,22,33 As clinicians begin to target larger regions of interest necessary for the treatment of widely distributed neurodegenerative and neoplastic processes, refinements in viral delivery and vector design will provide the ability to transduce larger cell numbers and volumes in the adult brain. Because direct injection of AAV2 only provides efficient neuronal transduction at the injection site,27 CED, first developed by Oldfield and Bankiewicz,1–3,6,9,11,13,21 has emerged as an important tool for delivering large vector volumes to the CNS of patients with Parkinson disease7,16,23 and certain lysosomal storage disorders.26,37 In addition to enhancing viral delivery methods, higher CNS-specific transduction efficiency has been achieved by cross-packaging AAV2 genomes recombinantly with endogenous AAV capsid sequences from human (AAV2/1 and AAV2/5)15,30 and nonhuman primates (AAV2/7 and AAV2/8).10 To date, the only available data comparing the safety and efficacy profiles of these newer AAV2 pseudotypes in the CNS come from rodent studies. In general, these studies show that most recombinant pseudotypes have significantly higher transduction efficiencies4,5,14,28,34 and similarly transient inflammatory responses compared with standard AAV2/2.25,31 No similar comparative efficacy data are available from the CNS of humans or nonhuman primates and relatively little toxicity data exists with CED of AAV pseudotypes in nonhuman primates. With the exception of a single study reporting necrotic plaques in the striatum of a nonhuman primate rhesus macaque following infusion of an AAV2/2 GFP construct,8 most studies in monkeys and humans have failed to find convincing evidence of AAV2-mediated viral toxicity. This study aims to evaluate potential toxicity, neurotropism, and transduction efficiency of 3 recombinantly pseudo-typed AAV2 constructs (2/1, 2/5, and 2/8) and the standard nonpseudotyped AAV2/2 serotype following CED into the primate striatum, to facilitate the rational selection of AAV vectors for use in human intracerebral gene therapy trials.

Methods

Vector Construction and Production

Adenovirus-free AAV2 serotype stocks for AAV2/1, AAV2/2, AAV2/5, and AAV2/8 were generated by the Harvard Gene Therapy Initiative using established protocols.25 The expression cassette incorporated a CMV promoter and an EGFP sequence flanked by human β-globulin inserted between AAV2 inverted terminal repeats (terminal repeat 2–CMV–β-globin–EGFP–β-globin–terminal repeat 2). A 3-plasmid transduction protocol was used to package the AAV2-EGFP genomes in AAV1, AAV2, AAV5, and AAV8 capsids. Adeno-associated virus 2/2 was purified by heparin column chromatography while AAV2/1, 2/2, and 2/8 were purified by an iodixanol density gradient. The isolated virus was dialyzed extensively against 0.1 M PBS (pH 7.4) and titered by dot blot hybridization, yielding between 2.7 × 1012 and 1.6 × 1013 genomic copies/ml. Viral titers were matched by diluting each with an appropriate volume of 0.1 M PBS for a final common vector titer of 2.7 × 1012 genomic copies/ml.

Convection-Enhanced Delivery of AAV2

All animal handling protocols and surgical procedures in this study were approved by the Massachusetts General Hospital Subcommittee on Research Animal Care in accordance with the Association for Assessment and Accreditation of Laboratory Animal Care International and conform to the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals (Institute of Laboratory Animal Resources, National Research Council. Washington, DC: National Academy Press, 1996). Four young male nonhuman primate monkeys (Macaca mulatta) weighing 3.0 ± 0.5 kg at the time of surgery were obtained from the Biomedical Research Foundation/Charles River Laboratories in Houston, Texas. During a 45-day quarantine each animal was screened for tuberculosis and simian B virus.

Ketamine hydrochloride (10 mg/kg) and xylazine (0.5 mg/kg) were administered intramuscularly before placement in an MR imaging–compatible stereotactic head frame. Animals were imaged at 1.5 T, and T2-weighted coronal sequences were acquired (GE Sigma; TR = 4500 msec, TE = 100/10 msec, 3-mm acquisition slices). The operative coordinates for 6 injection sites per hemisphere were planned from magnified coronal images using OsiriX software (www.osirix-viewer.com) based on standard Cartesian coordinates from The Rhesus Monkey Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates by Paxinos et al.29 Injection coordinates were then correlated with head frame landmarks to generate frame-based measurements for surgery.

In a dedicated primate surgical facility, animals were prepared and sterilely draped for surgery as described in detail previously.35 All portions of the intracranial surgery were performed under deep halothane anesthesia (0.5%–2.0% volume) without use of any paralytic agents. After unilateral or bilateral craniotomy, and durotomy, the injection catheters were stereotactically guided to 6 striatal targets, 2 in the caudate head and 4 along the rostrocaudal length of the postcommissural putamen. Thirty microliter infusions of a selected AAV2 serotype (2/1, 2/2, 2/5, or 2/8) were simultaneously delivered to each of the 6 striatal targets using separately controlled precision micropumps (BAS Beehive infusion pumps, Bioanalytical Systems Inc.), ramped to a maximum flow rate of 0.5 μl/min. Total delivery volume was 180 μl of 2.7 × 1012 genomic copies/ml of viral vector (3.60 × 1011 viral genomes to each hemisphere) over 90 minutes. Cannula design, preparation of loading lines, and CED followed the method of Hadaczek et al.12 modified with the use of a custom-made multicatheter headstage capable of independently and simultaneously targeting 6 cannulae.32 Fifteen minutes after infusion, the needles were raised at a rate of 1 mm/minute until clear of the cortical surface. The dura was reapproximated and the skin was closed in 2 layers with absorbable suture after placement of a small sterile titanium plate to cover the craniectomy site. Animals were extubated and allowed to recover spontaneously under close observation. They were then returned to their cages and had free access to food and water within 3 hours of surgery. Animals 9306 and 8706 were treated with a unilateral recombinant AAV2/2-EGFP injection. Animal 7806 was treated bilaterally with AAV2/1-EGFP in the left striatum and AAV2/5-EGFP in the right striatum. Animal 9106 was treated bilaterally with AAV2/ 2-EGFP in the left striatum and AAV2/8 in the right striatum.

Tissue Preparation and Immunohistochemistry

At the end of the 6-week survival period animals were killed in accordance with the guidelines of the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Briefly, after deep sedation with ketamine hydrochloride (30 mg/ kg intramuscularly), a lethal dose of sodium pentobarbital (86 mg/kg Beuthanasia solution) was given intravenously. Once pupillary and digit-compression reflexes disappeared, the animal was transcardially perfused with 1 L of ice-cold heparinized PBS (10 U/ml) followed by 1 L of freshly depolymerized 4% paraformaldehyde. The brains were then removed from the skulls, sliced into 2-mm slabs in the coronal plane using a brain matrix/cutting mold, and postfixed in 10% neutral buffer formalin at 4°C for 48 hours. Brain slabs were then sunk over 2 days in graded sucrose solutions, snap frozen in a bath of liquid isopentane, and cut on a freezing-sliding microtome (Leica) into 40-μm-thick sections. Sections were then rinsed in 0.1 M PBS and postfixed in acetone, then precooled to −20°C for 3–5 minutes. The sections were rinsed in PBS and placed in blocking solution (10% fetal bovine serum, 0.5% Triton X-100 in PBS) for 1 hour at room temperature.

Immunohistochemistry was performed on every tenth section with primary antibodies against GFP (1:1000, Molecular Probes), neuronal-specific nuclear protein (1:100, clone A60, Millipore), neuronal dendritic marker MAP2 (1:100, Millipore), GFAP (1:200, Zymed Laboratories, Inc.), and caspase-3 (1:200, Cell Signaling Technology). Tissue sections were analyzed on a Nikon E1000 microscope equipped with an X-Cite 120 fluorescence illuminator unit (EXFO Life Sciences). Images were acquired with a Retiga EX cooled charge-coupled device camera (QImaging) and captured with Volocity image analysis software (version 4, Improvision).

Stereological Analysis

Unbiased stereological counting methods using Stereo Investigator image-capture equipment and software (MicroBrightField, Inc.) attached to a microscope (Axioskop 2+, Carl Zeiss) equipped with a motorized, computer-controlled stage as well as an oil-immersion lens (magnification 40) were used to estimate cell numbers and striatal volume. In every tenth section (at 400-μm intervals) we defined a region of interest and counting volume by outlining the caudate and putamen separately at low magnification (2.5), taking care to exclude the internal capsule from the internal contour. To estimate the number of labeled cells within the reference volume, a modified optical fractionator-disector method36 was used to count profile tops under oil immersion (magnification 40) within a 200 × 200–μm counting grid placed sequentially over the region of interest every 1000 μm, but starting from a random point. The Gunderson coefficient of error for each animal was < 5%. Total striatal volume was estimated using a Cavalieri method from the same sections contoured above. From these numbers, we were able to calculate transduction efficiency expressed as the number of GFP-labeled cells/mm3 of striatal tissue. Quantitative analysis of GFP-labeled cell type was undertaken using a confocal microscope (LSM510 META, Carl Zeiss) to unequivocally identify GFAP or MAP2 colocalization within a cell using an extremely thin optical plane.

Results

Intraoperative and Perioperative Morbidity Associated With CED Procedure

The operative procedure, including the 90-minute infusion of vector, was well tolerated in all of the animals. The first 2 animals were treated with unilateral injections of 180 μl of vector and the second 2 animals with bilateral injections (180 μl of vector in each hemisphere); the bilateral injections were equally well tolerated. At the multiple needle injection sites on the cortical surface, no signs of tissue disruption or hemorrhage were noted. Within 1 hour after surgery, each animal regained alertness to the level of self-grooming. No adverse behavioral events such as vomiting, ataxia, seizure, or posturing indicative of pain were observed in any animal. All incisions healed well without signs of infection. Weight gain, grooming, and social interaction were indistinguishable from other unoperated animals within the colony. All animals survived the planned 6-week postsurgical survival period.

Histological Assessment After CED of AAV2 Pseuodtypes

The entire postfixed brain was cut into serial 2-mm slabs in the coronal plane for gross examination. No evidence of hemosiderin staining within the parenchyma or on the cortical surface was found to suggest gross intracranial hemorrhage. Microscopic examination of the striatum at magnifications of 10 and 40 revealed no obvious necrosis, ischemia, reactive gliosis, perivascular cuffing, or evidence of neoplastic proliferation. It was occasionally possible to locate small holes within the parenchyma of the caudoputamen that were consistent with the location of the cannula infusion tracts. These tracts measured < 100 μm in diameter.

Serotype-Specific Differences

Number of GFP-Positive Cells per Striatum

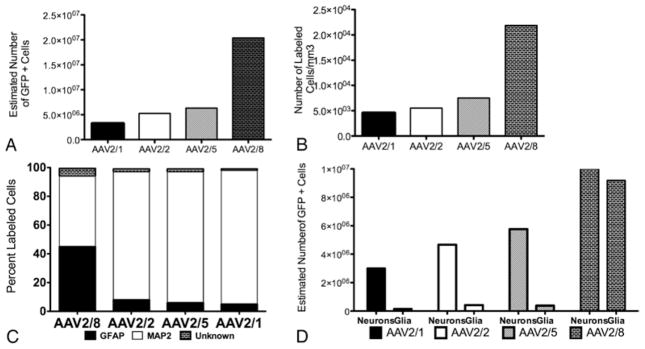

The number of GFP-positive cells in the striatum was determined by immunostaining fixed sections of brain tissue using a primary antibody to GFP and a fluorescent-conjugated secondary antibody as shown for AAV2/2 in Fig. 1. Unbiased stereological counts were performed under a magnification of 40 and demonstrated similar numbers of transduced cells (labeled cells/striatum) between AAV2/1 (3.2 × 106 cells), AAV2/2 (5.3 × 106 cells), and AAV2/5 (6.3 × 106 cells). Higher numbers of transduced cells were observed with AAV2/8 transduction (2.0 × 107 cells). As expected, no GFP-positive cells were found in the contralateral striatum of the first 2 animals that received single-hemisphere CED. The number of GFP-labeled cells is represented in Fig. 2A.

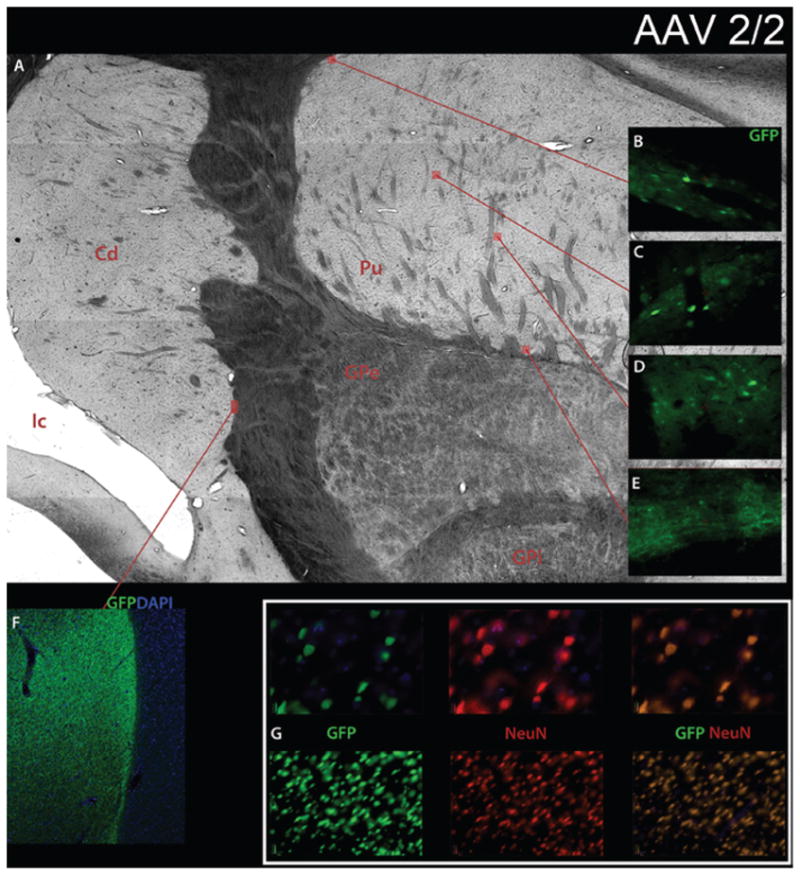

Fig. 1.

Transduction of nonhuman primate striatum by recombinant AAV2/2. Sections were double-stained for neuronal-specific nuclear protein (NeuN-neurons) and EGFP (AAV-transgene). A: Brightfield low-power mosaic image of striatum. Original magnification × 100. B–E: Windows of fluorescence GFP staining. Original magnification × 10. F: Low-power fluorescence mosaic image with GFP and 4,6′-diamino-2-phenylindole-dihydrochloride (DAPI) demonstrating high transduction efficiency at the border between the caudate and internal capsule. Original magnification × 10. G: GFP, NeuN, and combined GFP and NeuN fluorescence images with DAPI showing high transduction efficiency in GFP window, high neuronal density in NeuN window, and complete overlap in GFP and NeuN combined window with the recombinant AAV2/2 construct. Original magnification × 4 (lower row), × 20 (upper row). Cd = caudate; GPe = globus pallidus externus; GPi = globus pallidus internus; Ic = internal capsule; Pu = putamen.

Fig. 2.

Graphs showing number of GFP positively labeled cells (A), transduction efficiency (B), cell type specificity (C), and estimated transduction number of neurons and glia (D), using unbiased stereological counts. A: Number of positively labeled cells in striatum with single-sided injection, in which AAV2/8 > AAV2/5 > AAV2/2 > AAV2/1. B: Transduction efficiency (number of GFP-positive cells/mm3), in which AAV2/8 > AAV2/5 > AAV2/2 > AAV2/1. C: Cell type specificity (percentage of labeled cells) demonstrating almost complete neuronal specificity with AAV2/1, AAV2/2, and AAV2/5, but mixed cell type specificity withAAV2/8. D: Cell type specificity applied to stereological results from panel A, for estimated total number of transduced neurons and glia in striatum.

Density of GFP-Positive Cells in Striatum

Unbiased stereological counts also demonstrated similar transduction efficiency (labeled cells/mm3) between AAV2/1 (4551 cells/mm3), AAV2/2 (5538 cells/mm3), and AAV2/5 (7533 cells/mm3), but greater transduction efficiency with AAV2/8 (21,855 cells/mm3). Transduction efficiency is represented in Fig. 2B.

Cell Type Specificity and Estimates of Total Transduction Events

Adeno-associated virus 2/1, 2/2, and 2/5 transduced neurons almost exclusively (93%, 89%, and 91%, respectively), while AAV2/8 transduced a more even distribution of neurons (49%) and glia (45%; Figs. 2C and 3). Applying cell type specificity to the total number of striatal transduced cells, the estimate of labeled neurons was greatest for AAV2/8 (1.00 × 107 neurons), followed by AAV2/5 (5.77 × 106 neurons), AAV2/2 (4.67 × 106 neurons), and AAV2/1 (3.01 × 106 neurons; Fig. 2D). The highest number of glial cells labeled in the striatum was noted with AAV2/8 (9.18 × 106 glial cells), followed by AAV2/2 (4.20 × 105 glial cells), AAV2/5 (3.80 × 105 glial cells), and AAV2/1 (1.62 × 105 glial cells). Serotype specificity results were also applied to the transduction efficiency stereological results (Fig. 2D).

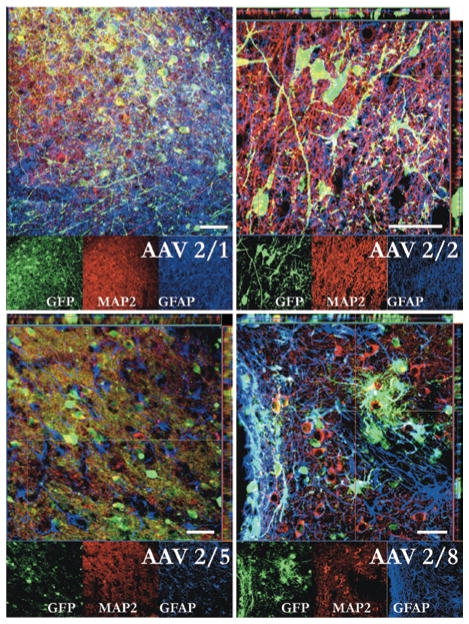

Fig. 3.

Serotype-specific transduction differences between recombinant AAV2/1, 2/2, 2/5, and 2/8. Triple-labeled confocal micrographs with merged images (larger images) and single channels (smaller images) in GFP, MAP2 (neurons), and GFAP (glia). Adeno-associated virus 2/1, 2/2, and 2/5 show predominantly neuronal colabeling of MAP2 and GFP, whereas AAV2/8 demonstrates an almost equal combination of GFAP and MAP2 with GFP. Counts from confocal images were used to generate cell type specificity measurements. Bar = 100 μm.

Caspase-3 Activation

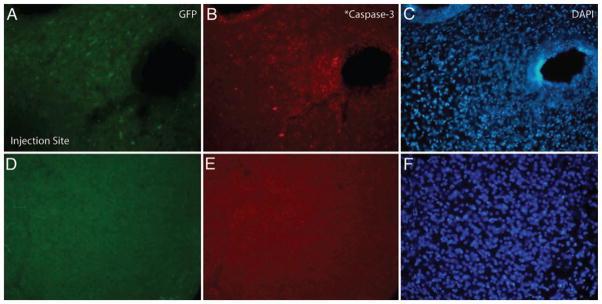

Adeno-associated virus 2/2, 2/5, and 2/8 convected tissue demonstrated no caspase-3 activation in the entire transduced volume (Fig. 4). Of the 4 serotypes, only AAV2/1 activated caspase-3, and then only in cells immediately near the injection site.

Fig. 4.

Caspase-3 activation near the injection tract of AAV2/1. Green fluorescent protein, caspase-3, and DAPI fluorescence images near (A–C) and away from (D–F) injection tract. Caspase-3 activation noted surrounding and around the injection tract (B) of AAV2/1, but not noted with other serotypes. Caspase-3 activation not observed beyond the needle tract (E) in any serotype.

Discussion

The goal of using AAV2 vectors for intracerebral gene therapy has taken an important initial step with the commencement of clinical trials.17,22,33 As Phase II efficacy data emerges, the need for increased transduction efficiency and volume will be even more important for effectively treating the large human cerebrum. The ability to modulate vector cell type specificity will open new applications for CNS gene therapy. To date, several in vivo studies support the use of alternative AAV serotypes for these challenges, but with the exception of AAV1,11 pseudotyped AAV vectors have only been studied in small animal models.5,14,20,24,28,34 To better characterize the potential benefits of pseudotyped AAV vectors for CNS gene therapy, we used CED to compare AAV2/1, 2/5, and 2/8 against AAV2/2 in a nonhuman primate model. While significant transgene expression was observed with all serotypes, our main result suggests that AAV 2/8 has the highest transduction efficiency and broadest cell type distribution. Cell type specificity was primarily neuronal with AAV2/1, 2/2, and 2/5. Adeno-associated virus 2/8 transduced neuronal and glia almost evenly. To place these findings in context with the literature of intracerebral and more specifically, striatal delivery of AAV serotypes, we summarized several reports in Table 1. Two major trends emerge from these studies. First, transduction efficiency is typically best with AAV2/8.14,34 Second, both AAV2/2 and the newer AAV2/1, 2/5, and 2/8 serotypes transfect neurons, with the exception of 1 report suggesting that cell type specificity is predominantly promoter driven for AAV2/8-GFP.20 Putting these results in a larger context, with specific attention to vector design (promoter, reporter gene), animal model (species-specific tropism), and delivery method (titer, CED), we compared our results with the literature with a specific focus on transduction efficiency, total transduction, and cell type specificity.

TABLE 1.

Review of transduction efficiency, specificity, and vector characteristics after striatal CED*

| Authors & Year |

Study Characteristics |

Transduction Efficiency |

Cell Type Specificity |

|||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Species | Promoter | Titer† | Gene | AAV2/1 | AAV2/2 | AAV2/5 | AAV2/8 | AAV2/1 Neurons |

AAV2/1 Glia |

AAV2/2 Neurons |

AAV2/2 Glia |

AAV2/5 Neurons |

AAV2/5 Glia |

AAV2/8 Neurons |

AAV2/8 Glia |

|

| Sanchez et al., 2008 | NHP | CMV | 360 | EGFP | + | + | ++ | +++ | +++ | — | +++ | — | +++ | — | ++ | ++ |

| Harding et al., 2006 | mouse | CAG | 9.3 | GFP | NA | + | ++ | +++ | NA | NA | +++ | — | ++ | + | +++ | — |

| Burger et al., 2004 | rat | CBA | 60 | GFP | +++ | + | +++ | NA | +++ | — | +++ | — | +++ | — | NA | NA |

| Hadaczek et al., 2006 | NHP | CMV | 150, 360 |

TK/ AADC |

NA | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | +++ | — | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Hadaczek et al., 2009 | NHP | CMV | 230 | hrGFP | + | NA | NA | NA | — | +++ | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Bankiewicz et al., 2000 | NHP | CMV | 360 | AADC | NA | + | NA | NA | NA | NA | +++ | — | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| McBride et al., 2008 | mouse | CMV | 25– 100 |

hrGFP | no stereology |

NA | NA | NA | +++ | — | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA |

| Paterna et al., 2004 | rat | CBA | 2 | EGFP | NA | + | ++ | NA | NA | NA | +++ | — | +++ | — | NA | NA |

| Taymans et al., 2007 | mouse | CMV | 1 | EGFP | +++ | + | ++ | ++ | +++ | — | +++ | — | +++ | — | +++ | — |

| Lawlor et al., 2009 | rat | CMV, GFAP |

3 | EGFP | NA | NA | NA | ++ | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | +++ (CMV) |

+++ (GFAP) |

AADC = aromatic L-amino acid decarboxylase; NA = not applicable; NHP = nonhuman primate; — = no transduction; + = few positive cells; ++ = many positive cells; +++ = complete saturation of cells.

Unit × 109 viral genomes/hemisphere.

The gene therapy literature uses several methods to quantify AAV transduction, including transduction efficiency, total transduction cell number, and transduction volume. Of these 3 methods, transduction efficiency is the easiest to compare across in vivo models. In a small animal model, Harding et al.14 demonstrated the relative transduction efficiency of AAV8 > AAV5 > AAV2 serotypes in mouse striatum, which were similar to our trans-duction efficiency of AAV2/8 > AAV2/5 > AAV2/2 in the primate brain. Burger et al.5 used total cell transduction to compare AAV2/1, 2/2, and 2/5 in rat striatum, where AAV2/1 and 2/5 outperformed AAV2/2 by 8-fold and 10-fold, respectively. Total cell transduction differences were more modest in our study, with the exception of a 4-fold increase with AAV2/8, possibly due to the differences between the CMV and CBA promoters used.5 Transduction volume is used by several studies to compare AAV sero-types28,34 but these values were difficult to compare across species and delivery methods. Nonhuman primate models have been used for striatal delivery of AAV2 and AAV1. We measured a transduction efficiency of 5538 cells/mm3 over the entire caudoputamen whereas Hadaczek et al.12 reported a transduction efficiency of 11,600 neurons/mm3 in the putamen and 4500 neurons/mm3 in the globus pallidus using a similar promoter, vector volume, and titer of AAV2-CMV-TK. Although we cannot directly compare transduction volumes between studies because of different convection parameters, the same group recently used AAV1-hrGFP to transduce an average striatal volume of 707 ± 125 mm3 (approximately 50% of total striatal volume) using 4.6 × 1011 DNase 1–resistant vector particles of plasmid AAV1-CMV-hrGFP.11 This total striatal transduction volume was significantly smaller than the putamen transduction volume of 837.7 mm3 (75% total putamen), using less than one-third of the vector dose (1.5 × 1011 viral genomes/ml of pAAV2-CMV-TK). The ratio of transduction volumes between these 2 nonhuman primate studies (AAV2 > AAV1) was also observed with our total cell transduction and transduction efficiency stereological results.

Cell-specific tropism of AAV serotypes is also well characterized in small animal models. Several groups reported neuronal transduction with AAV2/2, AAV2/5, and AAV2/8 in mouse brain,14,28,34 and with AAV2/1, 2/2, and 2/5 in rat striatum.5 Lawlor et al.20 demonstrated promoter-specific tropism with AAV2/8 in rat brain, where the CMV promoter yielded predominantly neuronal specificity, the GFAP promoter predominantly glial specificity, and the myelin basic protein promoter predominantly oligodendroglial specificity.20 Nonhuman primate models also demonstrate primarily neuronal cell type specificity with striatal convection of AAV2.12 Interestingly, Hadaczek et al.11 demonstrated predominantly astrocyte-specific transduction with AAV1 in nonhuman primate striatum, which contrasted the neuronal labeling of efferent targets from the same injection, including subthalamic nucleus and globus pallidus, and neuronal labeling seen after separate convection in the basal forebrain.11 The authors proposed that these local differences in AAV1 tropism were due to regional neuronal phenotype differences. Our report, like others involving rhesus non-human primates,1,12 confirms the predominant neuronal specificity of AAV2/2 in the striatum, but in contrast to Hadaczek et al.11 we describe neuronal cell tropism for AAV2/1 using similar CMV promoters. Older AAV purification methods have been shown to dramatically impact AAV tropism by protein contaminates19 but both iodixanol density gradient (AAV2/1-EGFP) and ion exchange chromatography (AAV1-hrGFP) are well regarded for providing low contaminant vectors. While Hadaczek et al.11 used a different species of nonhuman primate from our rhesus model (cynomolgus monkeys [Macaca fascicularis]), to our knowledge no species-specific effect has been reported within the nonhuman primate genus for serotype specificity using AAV. Our cell-specificity results for AAV2/5 (91% neuronal, 6% glial) are comparable to small animal studies. Finally, AAV2/8 showed a higher percentage of glial cell transduction in our study when compared with rodent studies. If future AAV2/8 studies support promoter-directed cell tropism in nonhuman primate experiments, AAV2/8 may offer greater flexibility for cell type specific gene therapy.

Regarding safety, AAV2/2 vectors have been generally considered safe and have entered clinical trials with considerable supporting data in this regard, showing little direct tissue toxicity. One report18 previously suggested that AAV2/8-GFP is capable of producing neurotoxic levels of the reporter transgene GFP, but only in dopamine-producing neurons at a vector dose of 5 × 1010 viral genomes. In this report, our limited investigation of AAV-mediated tissue toxicity, using caspase-3 staining as a marker of apoptosis, revealed some positive staining near the injection site of AAV2/1, but not for other vectors. As far as we know, this finding has not been reported in the literature, and represents a potential future focus of investigation. We did not observe significant toxicity with any serotype and the viral titers and method of delivery in this study did not appear to induce neurotoxicity.

The data presented in this report may suggest that for certain applications, AAV2/8 may offer a better profile for transgene delivery into the CNS with higher transduction efficiencies and the ability to transduce both neurons and glia efficiently. Additional studies examining GFAP and myelin basic protein promoters may be of interest to better assess the degree to which the cell type specificity of AAV2/8 in the nonhuman primate brain can be specifically engineered. While a high specificity to neurons may add to the safety profile by not transducing antigen-presenting cells, Hadaczek et al.11 makes the argument that avoiding glial transduction limits the therapeutic potential in 2 important ways. Neuronal-specific transduction is limited to 20% of the CNS cell population, reducing potential expression of secreted factors. Secondly, by not targeting glial cells such as oligodendrocytes, demyelinating diseases may not be amenable to gene therapy using AAV2/2 vectors. One value of extending AAV serotype testing to nonhuman primate models is better approximation of the challenges with delivering vectors over large brain volumes. We believe that the differences observed could be exploited to maximize the success of human intracerebral gene delivery. While species-specific differences limit direct translation from this nonhuman primate model to clinical trials, we believe that the significant vector differences in gene delivery in this report show support for further investigation of alternative sero-types for human intracerebral gene therapy.

Conclusions

Convection-enhanced delivery of alternative AAV serotypes provides significant opportunities for improving transduction efficiency and broadening cell type specificity with CNS gene therapy. We compared AAV2/1, 2/5, and 2/8 against AAV2/2 in nonhuman primates using CED, to better characterize these differences. For certain applications, AAV2/8 may offer a better profile for transgene delivery into the CNS with higher transduction efficiencies, and the ability to transduce both neurons and glia effectively. Future experiments may focus on promoter-specific effects of novel serotypes to provide broader applications of gene therapy for human disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the Harvard Gene Therapy Initiative at Harvard Medical School for AAV2/1, AAV2/2, AAV2/5, and AAV2/8 vector stocks. The authors thank John Bringas and Krystof S. Bankiewicz, M.D., Ph.D., Department of Neurosurgery, University of California, San Francisco, for their generous technical advice.

Abbreviations used in this paper

- AAV2

adeno-associated virus type 2

- AAV2/2

AAV2 serotype 2

- CBA

CMV/chicken β-actin

- CED

convection-enhanced delivery

- CMV

cytomegalovirus

- EGFP

enhanced green fluorescent protein

- GFAP

glial fibrillary acidic protein

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- hrGFP

humanized Renilla reniformis GFP

- MAP

microtubule-associated protein

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- TK

thymidine kinase

Footnotes

Author contributions to the study and manuscript preparation include the following. Conception and design: Carter, Sanchez, Tierney, Gale, Alavian, Mulligan. Acquisition of data: Carter, Sanchez, Tierney, Gale, Alavian. Analysis and interpretation of data: Carter, Sanchez, Tierney, Gale, Alavian. Drafting the article: Carter, Sanchez, Tierney, Gale, Alavian. Critically revising the article: Carter, Sanchez, Tierney, Gale, Alavian. Reviewed final version of the manuscript and approved it for submission: all authors. Statistical analysis: Carter, Sanchez, Tierney, Gale, Alavian. Administrative/ technical/material support: all authors. Study supervision: Carter.

Portions of this work were presented in poster form on September 23, 2008, at the CNS Annual Meeting in Orlando, Florida, and on May 24, 2009, at the World Society for Stereotactic and Functional Neurosurgery Annual Meeting in Toronto, Canada.

Disclosure

Vector stocks were kindly donated by the Harvard Gene Therapy Initiative at Harvard Medical School. Dr. Sanchez was supported by an NIH/National Cancer Institute T-32 Training Program in Cancer Biology grant (no. 2T32CA071345-11; Surgical Oncology). Material costs for the research were provided by a grant from the HighQ Foundation (now known as the CHDI Foundation).

References

- 1.Bankiewicz KS, Eberling JL, Kohutnicka M, Jagust W, Pivirotto P, Bringas J, et al. Convection-enhanced delivery of AAV vector in parkinsonian monkeys; in vivo detection of gene expression and restoration of dopaminergic function using pro-drug approach. Exp Neurol. 2000;164:2–14. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bankiewicz KS, Forsayeth J, Eberling JL, Sanchez-Pernaute R, Pivirotto P, Bringas J, et al. Long-term clinical improvement in MPTP-lesioned primates after gene therapy with AAV-hAADC. Mol Ther. 2006;14:564–570. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bobo RH, Laske DW, Akbasak A, Morrison PF, Dedrick RL, Oldfield EH. Convection-enhanced delivery of macromolecules in the brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1994;91:2076–2080. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.6.2076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Broekman ML, Comer LA, Hyman BT, Sena-Esteves M. Adeno-associated virus vectors serotyped with AAV8 capsid are more efficient than AAV-1 or -2 serotypes for widespread gene delivery to the neonatal mouse brain. Neuroscience. 2006;138:501–510. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.11.057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Burger C, Gorbatyuk OS, Velardo MJ, Peden CS, Williams P, Zolotukhin S, et al. Recombinant AAV viral vectors pseudo-typed with viral capsids from serotypes 1, 2, and 5 display differential efficiency and cell tropism after delivery to different regions of the central nervous system. Mol Ther. 2004;10:302–317. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2004.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cunningham J, Pivirotto P, Bringas J, Suzuki B, Vijay S, Sanftner L, et al. Biodistribution of adeno-associated virus type-2 in nonhuman primates after convection-enhanced delivery to brain. Mol Ther. 2008;16:1267–1275. doi: 10.1038/mt.2008.111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eberling JL, Jagust WJ, Christine CW, Starr P, Larson P, Bankiewicz KS, et al. Results from a phase I safety trial of hAADC gene therapy for Parkinson disease. Neurology. 2008;70:1980–1983. doi: 10.1212/01.wnl.0000312381.29287.ff. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Emborg ME, Carbon M, Holden JE, During MJ, Ma Y, Tang C, et al. Subthalamic glutamic acid decarboxylase gene therapy: changes in motor function and cortical metabolism. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2007;27:501–509. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forsayeth JR, Eberling JL, Sanftner LM, Zhen Z, Pivirotto P, Bringas J, et al. A dose-ranging study of AAV-hAADC therapy in Parkinsonian monkeys. Mol Ther. 2006;14:571–577. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.04.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gao GP, Alvira MR, Wang L, Calcedo R, Johnston J, Wilson JM. Novel adeno-associated viruses from rhesus monkeys as vectors for human gene therapy. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11854–11859. doi: 10.1073/pnas.182412299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hadaczek P, Forsayeth J, Mirek H, Munson K, Bringas J, Pivirotto P, et al. Transduction of nonhuman primate brain with adeno-associated virus serotype 1: vector trafficking and immune response. Hum Gene Ther. 2009;20:225–237. doi: 10.1089/hum.2008.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hadaczek P, Kohutnicka M, Krauze MT, Bringas J, Pivirotto P, Cunningham J, et al. Convection-enhanced delivery of adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV2) into the striatum and transport of AAV2 within monkey brain. Hum Gene Ther. 2006;17:291–302. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hamilton JF, Morrison PF, Chen MY, Harvey-White J, Pernaute RS, Phillips H, et al. Heparin coinfusion during convection-enhanced delivery (CED) increases the distribution of the glial-derived neurotrophic factor (GDNF) ligand family in rat striatum and enhances the pharmacological activity of neurturin. Exp Neurol. 2001;168:155–161. doi: 10.1006/exnr.2000.7571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harding TC, Dickinson PJ, Roberts BN, Yendluri S, Gonzalez-Edick M, Lecouteur RA, et al. Enhanced gene transfer efficiency in the murine striatum and an orthotopic glioblastoma tumor model, using AAV-7- and AAV-8-pseudotyped vectors. Hum Gene Ther. 2006;17:807–820. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.17.807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hildinger M, Auricchio A, Gao G, Wang L, Chirmule N, Wilson JM. Hybrid vectors based on adeno-associated virus serotypes 2 and 5 for muscle-directed gene transfer. J Virol. 2001;75:6199–6203. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.13.6199-6203.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kaplitt MG, Feigin A, Tang C, Fitzsimons HL, Mattis P, Lawlor PA, et al. Safety and tolerability of gene therapy with an adeno-associated virus (AAV) borne GAD gene for Parkinson’s disease: an open label, phase I trial. Lancet. 2007;369:2097–2105. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60982-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kells AP, Hadaczek P, Yin D, Bringas J, Varenika V, Forsayeth J, et al. Efficient gene therapy-based method for the delivery of therapeutics to primate cortex. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:2407–2411. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0810682106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Klein RL, Dayton RD, Leidenheimer NJ, Jansen K, Golde TE, Zweig RM. Efficient neuronal gene transfer with AAV8 leads to neurotoxic levels of tau or green fluorescent proteins. Mol Ther. 2006;13:517–527. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klein RL, Dayton RD, Tatom JB, Henderson KM, Henning PP. AAV8, 9, Rh10, Rh43 vector gene transfer in the rat brain: effects of serotype, promoter and purification method. Mol Ther. 2008;16:89–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lawlor PA, Bland RJ, Mouravlev A, Young D, During MJ. Efficient gene delivery and selective transduction of glial cells in the mammalian brain by AAV serotypes isolated from nonhu-man primates. Mol Ther. 2009;17:1692–1702. doi: 10.1038/mt.2009.170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lieberman DM, Laske DW, Morrison PF, Bankiewicz KS, Oldfield EH. Convection-enhanced distribution of large molecules in gray matter during interstitial drug infusion. J Neurosurg. 1995;82:1021–1029. doi: 10.3171/jns.1995.82.6.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mandel RJ, Manfredsson FP, Foust KD, Rising A, Reimsnider S, Nash K, et al. Recombinant adeno-associated viral vectors as therapeutic agents to treat neurological disorders. Mol Ther. 2006;13:463–483. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2005.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Marks WJ, Jr, Ostrem JL, Verhagen L, Starr PA, Larson PS, Bakay RA, et al. Safety and tolerability of intraputaminal delivery of CERE-120 (adeno-associated virus serotype 2-neurturin) to patients with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease: an open-label, phase I trial. Lancet Neurol. 2008;7:400–408. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(08)70065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McBride JL, Boudreau RL, Harper SQ, Staber PD, Monteys AM, Martins I, et al. Artificial miRNAs mitigate shRNA-mediated toxicity in the brain: implications for the therapeutic development of RNAi. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2008;105:5868–5873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801775105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.McFarland NR, Lee JS, Hyman BT, McLean PJ. Comparison of transduction efficiency of recombinant AAV serotypes 1, 2, 5, and 8 in the rat nigrostriatal system. J Neurochem. 2009;109:838–845. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2009.06010.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McPhee SW, Janson CG, Li C, Samulski RJ, Camp AS, Francis J, et al. Immune responses to AAV in a phase I study for Canavan disease. J Gene Med. 2006;8:577–588. doi: 10.1002/jgm.885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Passini MA, Watson DJ, Wolfe JH. Gene delivery to the mouse brain with adeno-associated virus. Methods Mol Biol. 2004;246:225–236. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-650-9:225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Paterna JC, Feldon J, Büeler H. Transduction profiles of recombinant adeno-associated virus vectors derived from sero-types 2 and 5 in the nigrostriatal system of rats. J Virol. 2004;78:6808–6817. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.13.6808-6817.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Paxinos G, Haung XF, Petrides M, Toga AW. The Rhesus Monkey Brain in Stereotaxic Coordinates. 2. San Diego: Academic Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rabinowitz JE, Rolling F, Li C, Conrath H, Xiao W, Xiao X, et al. Cross-packaging of a single adeno-associated virus (AAV) type 2 vector genome into multiple AAV serotypes enables transduction with broad specificity. J Virol. 2002;76:791–801. doi: 10.1128/JVI.76.2.791-801.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Reimsnider S, Manfredsson FP, Muzyczka N, Mandel RJ. Time course of transgene expression after intrastriatal pseudotyped rAAV2/1, rAAV2/2, rAAV2/5, and rAAV2/8 transduction in the rat. Mol Ther. 2007;15:1504–1511. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sanchez CE, Gale J, Tierney TS, Mulligan RC, Carter BS. AAV2-mediated gene delivery to the non-human primate striatum: development of a multi-catheter injection system for reproducible single-measure intraoperative convection enhanced delivery. Presented at the Annual Meeting of the Congress of Neurological Surgeons; Orlando, Florida. September 20–25, 2008; [Accessed August 24, 2010]. (Poster) ( http://2008.cns.org/posterbrowser.aspx) [Google Scholar]

- 33.Sands MS, Davidson BL. Gene therapy for lysosomal storage diseases. Mol Ther. 2006;13:839–849. doi: 10.1016/j.ymthe.2006.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taymans JM, Vandenberghe LH, Haute CV, Thiry I, Deroose CM, Mortelmans L, et al. Comparative analysis of adeno-associated viral vector serotypes 1, 2, 5, 7, and 8 in mouse brain. Hum Gene Ther. 2007;18:195–206. doi: 10.1089/hum.2006.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tierney TS, Pradilla G, Wang PP, Clatterbuck RE, Tamargo RJ. Intracranial delivery of the nitric oxide donor diethyl-enetriamine/nitric oxide from a controlled-release polymer: toxicity in cynomolgus monkeys. Neurosurgery. 2006;58:952–960. doi: 10.1227/01.NEU.0000210182.48546.8F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.West MJ, Slomianka L, Gundersen HJ. Unbiased stereological estimation of the total number of neurons in the subdivisions of the rat hippocampus using the optical fractionator. Anat Rec. 1991;231:482–497. doi: 10.1002/ar.1092310411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Worgall S, Sondhi D, Hackett NR, Kosofsky B, Kekatpure MV, Neyzi N, et al. Treatment of late infantile neuronal ceroid lipofuscinosis by CNS administration of a serotype 2 adeno-associated virus expressing CLN2 cDNA. Hum Gene Ther. 2008;19:463–474. doi: 10.1089/hum.2008.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]