Abstract

Positron emission tomography (PET) has become a vital imaging modality in the diagnosis and treatment of disease, most notably cancer. A wide array of small molecule PET radiotracers have been developed that employ the short half-life radionuclides 11C, 13N, 15O, and 18F. However, PET radiopharmaceuticals based on biomolecular targeting vectors have been the subject of dramatically increased research in both the laboratory and the clinic. Typically based on antibodies, oligopeptides, or oligonucleotides, these tracers have longer biological half-lives than their small molecule counterparts and thus require labeling with radionuclides with longer, complementary radioactive half-lives, such as the metallic isotopes 64Cu, 68Ga, 86Y, and 89Zr. Each bioconjugate radiopharmaceutical has four component parts: biomolecular vector, radiometal, chelator, and covalent link between chelator and biomolecule. With the exception of the radiometal, a tremendous variety of choices exists for each of these pieces, and a plethora of different chelation, conjugation, and radiometallation strategies have been utilized to create agents ranging from 68Ga-labeled pentapeptides to 89Zr-labeled monoclonal antibodies. Herein, the authors present a practical guide to the construction of radiometal-based PET bioconjugates, in which the design choices and synthetic details of a wide range of biomolecular tracers from the literature are collected in a single reference. In assembling this information, the authors hope both to illuminate the diverse methods employed in the synthesis of these agents and also to create a useful reference for molecular imaging researchers both experienced and new to the field.

Introduction

Over the course of the past fifty years, advances in medical imaging have revolutionized clinical practice, with a wide variety of imaging modalities playing critical roles in the diagnosis and treatment of disease. Today, clinicians have at their disposal a remarkable range of medical imaging techniques, from more conventional modalities like ultrasound, conventional radiography (X-rays), X-ray computed tomography (CT scans), and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to more specialized methodologies such as single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and positron emission tomography (PET).

In recent years, medical imaging research has experienced a paradigm shift from its foundations in anatomical imaging towards techniques aimed at probing tissue phenotype and function.1 Indeed, both the cellular expression of disease biomarkers and fluctuations in tissue metabolism and microenvironment have emerged as extremely promising targets for imaging.2 Without question, the unique properties of radiopharmaceuticals have given nuclear imaging a leading role in this movement. The remarkable sensitivity of PET and SPECT combines with their ability to provide information complementary to the anatomical images produced by other modalities to make these techniques ideal for imaging biomarker- and microenvironment-targeted tracers.3,4 Both relatively young modalities, SPECT and PET have had an impact on medicine (and oncology in particular), which belies their novelty, and both have been the topic of numerous thorough and well-reasoned reviews.5–9 Both modalities have become extremely important in the clinic, and while PET is generally more expensive on both the clinical and pre-clinical levels, it also undoubtedly possesses a number of significant advantages over its single-photon cousin, most notably the ability to quantify images, higher sensitivity (PET requires tracer concentrations of ∼10−8 to 10−10 M, while SPECT requires concentrations approaching 10−6 M), and higher resolution (typically 6–8 mm for SPECT, compared to 2–3 mm or lower for PET). Therefore, in the interest of scope, the article at hand will limit itself to the younger and higher resolution of the techniques: positron emission tomography.

Regardless of the broader perspective, any discussion of PET benefits from a brief description of the underlying physical phenomena. Starting from the beginning, a positron released by a decaying radionuclide will travel in a tissue until it has exhausted its kinetic energy. At this point, it will encounter its antiparticle, an electron, and the two will mutually annihilate, completely converting their mass into two 511 keV γ-rays that must, due to conservation of momentum, have equal energies and travel 180° relative to one another. These γ-rays will then leave the tissue and strike waiting coincidence detectors; importantly, only when signals from two coincidence detectors simultaneously trigger the circuit is an output generated. The two principal advantages of PET thus lie in the physics: the short initial range of the positrons results in high resolution, and the coincidence detection methodology allows for tremendous sensitivity.

In the early 1950s, Brownell10 and Sweet11 developed the first devices for creating images using the coincident detection of γ-rays emitted from positron-electron annihilation events. At the same time, these researchers and others were pioneering the oncologic applications of positron imaging, specifically the imaging of brain tumors.10–14 Not until the 1970s, however, did the field take the next important practical step forward: tomographic systems and computer analysis were first applied to positron imaging, innovations which paved the way for the widespread clinical use of the modality.

Since the advent of PET in both the clinic and medical research laboratories, a number of positron-emitting isotopes have been developed for use in radiopharmaceuticals. For years, the field was dominated by small molecule tracers, radiopharmaceuticals whose short biological half-lives favor the use of non-metallic radionuclides with correspondingly short radioactive half-lives, such as 18F, 15O, 13N, and 11C (Table 1). In many ways, this is still true: [18F]-fluoride and the ubiquitous [18F]-fluorodeoxyglucose ([18F]-FDG) are the only FDA-approved PET radiopharmaceuticals commonly employed in oncology ([13N]-NH3 and [82Rb]-RbCl are FDA-approved but are used principally for myocardial perfusion scans). Further still, an examination of the list of PET radiotracers currently in NIH-sponsored clinical trials reveals an overwhelming majority of agents with non-metallic radionuclides, including among others the promising agents [18F]-FLT, [18F]-FES, [18F]-FDHT, [18F]-FMISO, [18F]-FACBC, [18F]-fluoroethylcholine, [18F]-deshydroxycholine, [18F]-FMAU, [11C]-acetate, [11C]-choline, [11C]-MeAIB, [11C]-MET, [124I]-IAZGP, and [124I]-FIAU.15

Table 1.

| Radionuclide | Half-life | Decay mode (% branching ratio) | Production route | E(β+)/keV | β+ end-point energy/keV | Abundance, Iβ+/% | Eγ/keV (intensity, Iγ/%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 11C | 1223.1 (12) s | β+ (100) | 14N(p,a)11C | 385.6 (4) | 960.2 (9) | 99.759 (15) | 511.0 (199.5) |

| 13N | 9.965 (4) m | β+ (100) | 16O(p,a)13N | 491.82 (12) | 1198.5 (3) | 99.8036 (20) | 511.0 (199.6) |

| 15O | 122.24 (16) s | β+ (100) |

15N(p,n)15O 14N(d,n)15O |

735.28 (23) | 1732.0 (5) | 99.9003 (10) | 511.0 (199.8) |

| 18F | 109.77 (5) m | β+ (100) |

18O(p,n)18F 20Ne(d,a)18F |

249.8 (3) | 633.5 (6) | 96.73 (4) | 511.0 (193.5) |

| 124I | 4.1760 (3) d | ε + β+ (100) β+ (22.7 [13]) |

124Te(p,n)124I | 687.04 (85) 974.74 (85) |

1,534.9 (19) 2,137.6 (19) |

11.7 (10) 10.7 (9) |

511.0 (45) 602.7 (62.9) 722.8 (10.4) 1,691.0 (11.2) |

ε = electron capture; m = minutes; d = days; s = seconds. Where positrons or γ-rays of different energies are emitted, only those with abundances of greater than 10% are listed. Unless otherwise stated, standard deviations are given in parentheses.

Yet despite the significant successes of small molecule probes labeled with non-metallic isotopes, these radionuclides possess a few critical limitations. First, the short half-lives of the most common non-metallic radionuclides - approximately 20 min for 11C, 10 min for 13N, 2 min for 15O, and 110 min for 18F - allow only for investigations of biological processes on the order of minutes or a few hours using tracers with rapid pharmacokinetic profiles. Second, both the short half-lives of the radionuclides and the frequent necessity of incorporating the radioisotopes into the core structure of the tracer (rather than in an appended chelator or prosthetic group) often necessitate demanding and complex syntheses. Third, the clinical and pre-clinical use of short half-life, non-metallic radionuclides often requires a local cyclotron facility; in its absence, the radionuclide in question will undergo many half-lives of decay while in transit. Given the resources required for the construction and operation of medical cyclotrons, this is simply not an option in many locations.

These limitations have been brought into focus by the increasing study and development of biomolecular targeting agents for cancer, including short peptides, antibodies, antibody fragments, and natural and non-natural oligonucleotides. Given that Nature herself has designed or inspired these agents, they often show sensitivities and specificities for cancer cell biomarkers that far exceed those of their small molecule counterparts. However, these biomolecular tracers typically have biological half-lives that are much longer than the radioactive half-lives of the most common non-metallic positron-emitting radionuclides; further, though less pressing, many of these biomolecules are incompatible with the chemistry required for direct labeling with non-metallic radionuclides.16–19

Given the enormous potential of biomolecular imaging agents, significant effort has been dedicated to the production, purification, and radiochemistry of positron-emitting radioisotopes of the metals Zr, Y, Ga, and Cu. These isotopes, specifically 64Cu, 68Ga, 86Y, and 89Zr, have radioactive half-lives (roughly 12.7, 1.1, 14.7, and 78.4 h, respectively) that favorably complement the biological half-lives of many biomolecular targeting vectors (Table 2). Although all four radiometals emit positrons, each has a characteristic positron range, which is the principal factor in determining imaging resolution. 64Cu and 89Zr emit very low energy positrons, producing image resolution comparable to that of 18F. 86Y and 68Ga, in contrast, emit higher energy positrons, which can result in slightly lower imaging resolutions, though this can be corrected through the use of mathematical algorithms.20 Further still, and equally critical, all four metals form stable chelate complexes that may be employed for the radiolabeling of biomacromolecules. To be sure, not all biomolecular PET tracers are labeled with radiometals, nor are all radiometallated PET tracers biomolecules. An 18F-labeled variant of the integrin-targeting RGD peptide21 and an 124I-labeled carbonic anhydrase-targeting antibody22 have produced very exciting results and are currently being employed in human studies. Moreover, a few radiometal-based small molecule tracers have also proved extremely promising, most notably [64Cu]-Cu(PTSM)23 and [64Cu]-Cu(ATSM),24 with the latter currently in a multi-center clinical trial as an imaging agent for hypoxia.25–28 Yet, despite these exceptions, the single most important application of positron-emitting radiometals is the development of tracers based on peptides, antibodies, and oligonucleotides.

Table 2.

Physical decay characteristics of common PET radiometals40

| Radionuclide | Half-life | Decay mode (% branching ratio) | Production route | E(β+)/keV | β+ end-point energy/keV | Abundance, Iβ+/% | Eγ/keV (intensity, Iγ/%) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 64Cu | 12.701(2) h | ε + β+ (61.5 [3]) β+ (17.6 [22]) β− (38.5 [3]) |

64Ni(p,n)64Cu | 278.21 (9) | 653.03 (20) | 17.60 (22) | 511.0 (35.2) | 84, 85 |

| 68Ga | 67.71 (9) m | ε + β+ (100) β+ (89.14 [12]) |

68Ge/68Ga | 836.02 (56) | 1889.1 (12) | 87.94 (12) | 511.0 (178.3) | 160, 70, 161 |

| 86Y | 14.74 (2) h | ε + β+ (100) β+ (31.9 [21]) |

86Sr(p,n)86Y | 535 (7) | 1221 (14) | 11.9 (5) | 443.1 (16.9) 511.0 (64) 627.7 (36.2) 703.3 (15) 777.4 (22.4) 1076.6 (82.5) 1153.0 (30.5) 1854.4 (17.2) 1920.7 (20.8) |

77 |

| 89Zr | 78.4 (12) h | ε + β+ (100) β+ (22.74 [24]) |

89Y(p,n)89Zr | 395.5 (11) | 902 (3) | 22.74 (24) | 511.0 (45.5) 909.2 (99.0 |

79, 83, 162–164 |

ε = electron capture; m = minutes; h = hours; s = seconds. Where positrons or γ-rays of different energies are emitted, only those with abundances of greater than 10% are listed. Unless otherwise stated, standard deviations are given in parentheses.

Importantly, the basic strategy for the incorporation of a radiometal into a biomolecule differs somewhat from the synthesis of a small molecule radiotracer containing a non-metallic PET radionuclide. In small molecule tracers, the radionuclide most often replaces an isotopologue (e.g. [11C]-acetate or [15O]-H2O) or is incorporated into the basic structure of a molecule with either the intent of strategically altering the behavior of the parent molecule (e.g. [18F]-FDG) or, more likely, disturbing the activity of the parent molecule as little as possible (e.g. [18F]-FDHT or [18F]-FES). In contrast, in biomolecular tracers, the radiometal is almost never directly attached to the biomolecule itself. Rather, the radionuclide is bound to a chelating moiety (e.g. DOTA29 or EDTA30), which is first covalently appended to the biomolecule with the intent of altering the vector's biochemical properties as little as possible.31,32

As new targets are described and radiometals become more available to the wider molecular imaging community, the amount of research into radiometal-based PET tracers has exploded in recent years. For example, over 60% of all publications describing 89Zr-PET have been published in the last four years (with well over 20% in 2010 alone).33 Indeed, the dramatic growth in this area and the expansion in the availability of radiometals have had the dual effects of broadening the appeal of biomolecular PET imaging and opening the field to investigators who previously may have left the development of PET probes to dedicated radiochemistry and molecular imaging laboratories. However, the frenetic pace of the field and the array of choices in chelation, conjugation, and metallation strategies may serve as an obstacle to those who are interested in the development of radiometallated PET tracers but lack significant bioconjugation or radiochemical experience.

This perspective aims at lowering this barrier. Here, we strive to create a practical guide to the synthesis of radiometal-based PET tracers. To this end, we have compiled the experimental details of chelator choice, conjugation strategy, and radiometallation conditions from the syntheses of a wide array of 64Cu-, 68Ga-, 86Y-, and 89Zr-labeled PET agents. Typically, reviews discuss the structure, behavior, biology, and imaging applications of these agents, with the experimental details touched upon only briefly or simply referenced.7,16,34–37 All too often, however, the search for a specific conjugation or metallation protocol results in an elongated, and in some cases circuitous, trek through the literature to find a simple incubation time or buffer concentration. Importantly, we do not strive for an exhaustive review of the radiochemistry or imaging applications of radiometal-based PET tracers. Others - most notably Carolyn Anderson and her coworkers at the Washington University School of Medicine and Martin Brechbiel and his coworkers at the National Cancer Institute - have produced well-written and remarkably thorough reviews on these topics.3,30,34,38–45

The core of this perspective lies not in the text but rather in the series of tables containing the practical details of chelator conjugation and radiometallation from a diverse collection of 64Cu-, 68Ga-, 86Y-, and 89Zr-labeled bioconjugates. We have elected not to include two types of macromolecular radiopharmaceuticals, bispecific antibodies and biomolecule-based nanoparticles, in the interest of space and scope, though these have been addressed well elsewhere.46–49 Further, it is important to note that some of the conjugation strategies described herein are now, for the most part, obsolete with respect to their original vector; for example, a number of syntheses for DOTATOC will be outlined, though this DOTA-modified somatostatin analogue is now widely commercially available. Yet we believe it is important to detail these conjugation methods nonetheless, for the synthetic routes themselves may prove useful in the future for the creation of conjugates with different biomolecular vectors. In collecting these techniques in one place, we hope not only to shed light upon the diverse methods employed in the synthesis of these agents but also, and perhaps more importantly, to create a useful reference for both experienced molecular imaging scientists and researchers new to the field.

The anatomy of a PET bioconjugate

A radiometallated PET bioconjugate has four component parts, each of which must be carefully considered during the design and synthesis of the tracer: (1) the biomolecular targeting vector, (2) the radiometal, (3) the chelator, and (4) the linker connecting the chelator and the biomolecule (Fig. 1). A detailed discussion of the possible targeting vectors lies outside the scope of this work, though biomolecules ranging from cyclic pentapeptides and short oligonucleotides to 40-amino acid peptides, antibody fragments, and full antibodies have been employed.30 Of course, the most important facet of the biomolecule moiety is its specificity for its biomarker target. Indeed, a wide array of biomarkers have been exploited. Most often, the chosen target is a cell surface marker protein or receptor, such as the somatostatin receptor family (SSTr),50 integrin family (e.g. αvβ3),51 gastrin-releasing peptide receptor (GRPR),52 and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR).53 In more specialized cases, disialogangliosides (e.g. GD2), mRNA gene products, and even the low pH environment of tumors have been targeted by antibodies,54 oligonucleotides,55 and short peptides,56 respectively. Targeting cytosolic proteins and enzymes with antibodies and oligopeptides is rare due to the considerable difficulty of getting large biomolecules into the cytoplasm. However, significant progress is being made in the development of cell- and nucleus-penetration strategies, and this technology may prove productive for intracellular or intranuclear PET imaging agents in the near future.

Fig. 1.

The anatomy of a PET bioconjugate.

Radiometals: properties and production

The principal radiometals employed for the labeling of biomolecular tracers are 64Cu, 68Ga, 86Y, and 89Zr. Of course, these are not the only positron-emitting radiometals. Some metallic radioisotopes, such as 60Cu, 61Cu, 62Cu, 82Rb, 52mMn, and 94mTc, have been used in PET studies to varying degrees, but their half-lives make them far better suited for small molecule tracers (e.g. [60Cu]-Cu(ATSM)).57–60 Other positron-emitting radiometals, including 45Ti ([45Ti]-transferrin61), 52Fe ([52Fe]-citrate/transferrin62), 55Co ([55Co]-antiCEA F(ab′)263,64), 66Ga ([66Ga]-octreotate65), 110mIn ([110mIn]-octreotate66), and 74As ([74As]-bavituximab67,68), have been employed in the synthesis of biomolecular radiopharmaceuticals.41 However, these will not receive more than a brief discussion here, due to either the lack of more than one or two radiotracers per isotope, the limited availability of the radionuclide in question, or decay characteristics that make the isotope sub-optimal for use in a clinical PET radiopharmaceutical.40

The selection of a radiometal from the four main candidates, 64Cu, 68Ga, 86Y, and 89Zr, is a critical factor in determining the ultimate properties of a PET bioconjugate. In this regard, one of the most important considerations is matching the radioactive half-life of the isotope to the biological half-life of the biomolecule. For example, 68Ga is an inappropriate choice for labeling fully intact IgG molecules, for the radionuclide will decay through a number of half-lives before the antibody reaches its fully optimal biodistribution within the body. Therefore, the longer lived radiometals 64Cu, 86Y, and especially 89Zr are most often employed for immunoPET with fully intact mAbs. That said, 68Ga has been used successfully in the construction of PET bioconjugates based on antibody fragments with shorter biological half-lives. Conversely, 89Zr would be an inappropriate choice for a short peptide radiotracer; in this case, the multi-day radioactive half-life of 89Zr would far exceed what is typically a multi-hour biological half-life of the peptide, resulting in poor PET counting statistics and unnecessarily increased radiation dose to the patient. Thus, 64Cu, 86Y, and 68Ga are most often employed for oligopeptide PET tracers. It is important to note that 64Cu and 86Y occupy a favorablef middle ground with respect to radioactive half-life, allowing these radionuclides to be utilized advantageously in both antibody- and peptide-based based tracers.

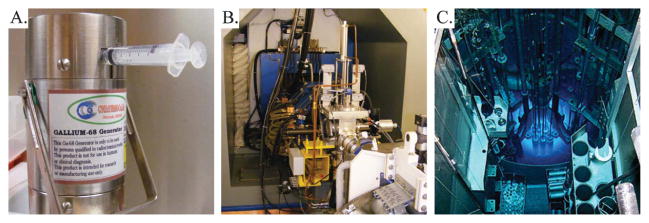

The production of radiometals in high radionuclidic purity and specific activity is essential to the development of effective bioconjugates for PET imaging, and while an in-depth understanding of the nuclear reactions and purification chemistry behind their production may not be necessary for the biomedical use of these isotopes, a brief overview of the processes surely has merit. The production methods for radionuclides fall into three general categories: generator, cyclotron, and nuclear reactor (Fig. 2). Of the positron-emitting radiometals addressed in this perspective, 68Ga is generator-produced, while 64Cu, 86Y, and 89Zr are produced using a medical cyclotron.

Fig. 2.

Three methods for the production of radionuclides: (A) 68Ga generator, (B) cyclotron, and (C) nuclear reactor. The authors acknowledge David Nickolaus of the Missouri University Research Reactor for the photo of the nuclear reactor.

68Ga is produced via the electron capture decay of its parent radionuclide, 68Ge. In the laboratory and clinic, 68Ga can be produced using a compact, cost-effective, and convenient 68Ge/68Ga generator system, which is capable of providing 68Ga for PET tracers for 1–2 years before being replaced.69 The 68Ga is eluted from the generator in 0.1 M HCl, providing a 68GaCl3 starting material for radiolabeling.70 Despite its convenience, the system does have some limitations, most notably high eluent volumes that often must be pH-adjusted prior to radiolabeling reactions, 68Ge break-through from the generator, and metal-based impurities. However, a number of purification techniques have been developed to circumvent the problems presented by the trace impurities in the 68Ga eluent.

86Y is the first of the three cyclotron-produced radiometals to be addressed here. 86Y is most often produced through the 86Sr(p,n)86Y reaction via bombardment of an isotopically enriched 86SrCO3 or 86SrO target with 8–15 MeV protons.71–74 A range of purification methods have been employed, including combinations of precipitation, ion exchange chromatography, chromatography with a Sr-selective resin, and electrolysis.75–77

89Zr has been produced via both the 89Y(p,n)89Zr and 89Y(d,2n)89Zr reactions. In the past, these methods have been used to successfully produce the radiometal using 13 MeV protons and 16 MeV deuterons, respectively, though both pathways have been complicated and limited by problematic purification protocols.78–80 A significant improvement upon these methods was provided by another production strategy that yielded 89Zr via the bombardment of 89Y on a copper target with 14 MeV protons, oxidation of Zr0 to Zr4+ with H2O2, and purification via anion exchange chromatography and subsequent sublimation steps.81,82 In the last few years, these methods have been improved upon further through the use of an 89Y thin-foil target (99% purity, 0.1 mm width), the optimization of bombardment conditions (15 MeV, 15 μA, 10° angle of incidence), and an improved solid phase hydroxamate resin purification to produce 89Zr reliably and reproducibly in very high specific activity (470–1195 μCi/mmol) and radionuclidic purity (>99.99%).83

Finally, 64Cu can be produced with either a nuclear reactor or a cyclotron via a variety of reaction pathways.3 In a nuclear reactor, 64Cu can be produced through the 63Cu(n,γ)64Cu and 64Zn(n,p)64Cu pathways. On a biomedical cyclotron, carrier-free 64Cu can be produced using the 64Ni(p,n)64Cu and 64Ni(d,2n)64Cu reactions.84–88 The former pathway has proven more successful and is currently used to provide 64Cu to research laboratories throughout the United States. In this method, the 64Cu is processed and purified via anion exchange chromatography to yield no carrier-added 64Cu2+. The expense of the enriched 64Ni target is a limitation of this production pathway, though a technique for the recycling of 64Ni has ameliorated this issue somewhat. In the last few years, a number of groups have worked to develop methods for the production of 64Cu using Zn targets through the 64Zn(d,2p)64Cu,66Zn(d,α)64Cu, and 68Zn(p,αn)64Cu reactions.89–92 These efforts have yielded some promising results but have failed to supplant the cyclotron-based 64Ni(p,n)64Cu pathway as the main route for 64Cu production.

Radiometal chelation chemistry

With both the targeting vectors and radiometals in hand, the spotlight next falls on how to combine these two essential parts of the PET bioconjugate. Indeed, both the formation of a kinetically inert metal chelate and the stable covalent attachment of the chelator moiety to the biomolecule are essential to the creation of an effective radiopharmaceutical. To this end, a wide variety of metal-chelating molecules have been synthesized, studied, and, in many cases, made bifunctional to facilitate their conjugation to a biomolecular vector (Fig. 3 and 4, vide infra). Transition metal chelators fall into two broad classes: macrocylic chelators and acyclic chelators. Each has its own unique set of advantages: while macrocyclic chelators typically offer greater kinetic stability, acyclic chelators usually have faster rates of metal binding. Generally, transition metal chelators offer at least four (and usually six or more) coordinating atoms, arrayed in a configuration that suits the preferred geometry of the oxidation state and d-orbital electron configuration of the metal in question. Yet simply having a generic chelator with well-organized and plentiful donor atoms is not enough; in every case, an appropriate chelator must be chosen to suit the selected radiometal (Table 3). Of course, however, some (e.g. DOTA) are more universally applicable than others (e.g. DiamSar). The most relevant oxidation states for the metals discussed here are Zr(IV), Ga(III), Y(III), and Cu(II); in vivo, only Cu(II) is at significant risk for reduction reactions. In terms of the commonly-employed ‘hard-soft’ system of classification, Zr(IV) is considered a very hard cation, with Y(III) and Ga(III) close behind on the spectrum. Cu(II), which is a borderline acid, straddles the hard/soft border and is thus easily the softest of the four.

Fig. 3.

Selected chelators and bifunctional chelators for 64Cu, 68Ga, 86Y, and 89Zr.

Fig. 4.

Selected chelators and bifunctional chelators for 64Cu, 68Ga, 86Y, and 89Zr.

Table 3.

Coordination number, donor set, and geometrya for selected complexes of Cu(II), Ga(III), Y(III), and Zr(IV)30

| Metal | Chelator | Ligand Donor Set | Total CN | Coordination Geometry | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cu(II) | DTPA | N3O3 | 6 | — | 165 |

| NOTA | N3O3 | 6 | distorted trigonal prism | 166, 167 | |

| DOTA | N4O2 | 6 | distorted octahedron | 168–170 | |

| TETA | N4O2 | 6 | distorted octahedron | 168–170 | |

| CB-TE2A | N4O2 | 6 | distorted octahedron | 101, 171 | |

| EC | N2S2 | 4 | distorted square planar | 172 | |

| DIAMSAR | N6 | 6 | distorted octahedron or trigonal prism | 173 | |

| Ga(III) | EDTA | N2O4 | 6 | distorted octahedron | 174, 175 |

| HBED | N2O4 | 6 | — | 176, 177 | |

| DTPA | N3O3 | 6? | — | 175 | |

| NOTA | N3O3 | 6 | distorted octahedron | 168, 178 | |

| DOTA | N4O2 | 6 | distorted octahedron | 168 | |

| TETA | N4O2 | 6 | distorted octahedron | 168 | |

| CB-TE2A | N4O2 | 6 | distorted octahedron | 30, 179 | |

| DFO | O6 | 6 | — | 180 | |

| Y(III) | DTPA | N3O5 | 8 | monocapped square antiprism | 116, 181, 182 |

| DOTA | N4O4 | 8 | square antiprism | 114, 116, 182 | |

| TETA | N4O2 | 8? | distorted dodecahedron(?) | 183 | |

| Zr(IV) | DFO | O6 | 7 or 8 | — | 125 |

| DOTA | N4O4 | 8? | square antiprism? | 115 | |

| EDTA | N2O4 | 8 | distorted dodecahedron | 181, 184 | |

| DTPA | N3O5 | 8 | distorted dodecahedron | 181, 184 |

Question marks denote uncertainty in coordination number or geometry, and “—” denotes that the coordination geometry is not known.

Cu(II) has a rich chelation chemistry, capable of the formation of four-, five-, and six-coordinate complexes, with geometries ranging from square planar to trigonal bipyrimidal and octahedral.3,30,32,36,42,93 Due to its position on the border between hard and soft metals, Cu(II) exhibits a great affinity for nitrogen donors, though it is also known to bind either harder oxygen or softer sulfur donors as well. Generally, a copper chelator will feature a mixture of uncharged nitrogen and anionic oxygen or sulfur donors in order to neutralize the charge of the dicationic metal. Alone in solution, the metal forms a five-coordinate aquo-complex with rapid water-exchange rates that translate into facile substitution reactions with other ligands.94 Due to its 3d9 electronic structure, Cu(II) prefers a square planar coordination geometry. In consequence, both macrocyclic and acyclic tetradentate chelators have been developed for bioconjugation, including those with N4 (e.g. cyclam), N2O2, and N2S2 (e.g. bis(aminothiolate)-based ligands) donor sets.95,96 Due to the critical importance of kinetic stability, however, the complexation of Cu(II) with its maximum of six donor atoms has become more popular than the use of tetradentate chelators. To this end, both six-coordinate macro-cyclic and acyclic chelators have been employed with donor sets including N2O4 (e.g. EDTA), N3O3 (e.g. DTPA or NOTA), N4O2 (e.g. DOTA or CB-TE2A), and N6 (e.g. SarAr, DiamSar, and AmBaSar).54,97–101 Of these options, CB-TE2A and the SarAr family seem to be particularly promising, given their high kinetic and thermodynamic stability. The possibility of the reduction of Cu(II) to Cu(I) under physiological conditions with certain ligand sets must also be noted. In some cases (e.g. 64Cu-ATSM), this reduction may be essential to the pharmacodynamics of the radiotracer; however, in most situations, it is an extremely undesirable behavior that compromises the integrity of the radiopharmaceutical.24

Smaller and harder than Cu2+, the Ga3+ cation typically binds ligands containing multiple anionic oxygen donors and adopts a coordination number of six, though complexes with four or five donor atoms are also known.36,38,44,102,103 Aqueous pH is particularly important in Ga3+ chelation chemistry: the low pKa of the Ga(H2O)63+ complex results in low solubility at physiological pH, while under basic conditions the affinity of the metal for hydroxide anions can result in its dissociation from chelators to form gallium hydroxide species. Tetradentate chelators with NO3, NS3, and N2S2 donor sets have been used.104–106 These polydentate ligands often combine with one or two water molecules or halides to place the metal in a distorted octahedral or distorted square pyramidal geometry; however, in some cases, the Ga3+ can adopt a simple four-coordinate distorted tetrahedral geometry. Acyclic and macrocylic hexadentate chelators are more common for Ga3+, including those with N2O2S2 (e.g. bis(aminothiolate)-based ligands), N2O4 (HBED), N3O3 (NOTA), N3S3 (TACN-TM), N4O2 (DOTA), and O6 (DFO) donor sets.102,107–110 Complexes bearing these ligands almost always adopt a distorted octahedral geometry. Amongst these, DOTA is easily the most commonly employed in bioconjugates. However, the ligand has two drawbacks that limit its suitability for 68Ga3+.111 A central cavity that is too large for the cation limits the stability of the complex, and sluggish complexation kinetics require reaction times and temperatures that are less than ideally compatible with the short half-life of 68Ga and the stability of some biomolecular constructs, respectively. In contrast, TACN-TM and HBED- and NOTA-based ligands are particularly promising chelation systems for 68Ga due to their high thermodynamic and kinetic stability.103,112,113

The chemistry of Y(III) provides a significant change of pace from the previous two metals. Much larger than the three other common PET radiometals, the closed-shell, hard Y3+ cation often reaches coordination numbers of eight or nine. Donor sets of N2O4 (EDTA), N3O3 (NOTAM), N3O5 (DTPA), N4O4 (DOTA), and N4O2 (TETA) have all been used to chelate the metal, with water molecules or other exogenous ligands filling the remaining coordination sites.114–117 The DOTA and DTPA ligands, however, form much more stable complexes with the metal than TETA and EDTA, indicating better chelator-metal matches in the former cases. The higher coordination numbers also result in more exotic geometries: the DTPA complex adopts a monocapped square antiprism structure, the EDTA complex assumes a distorted dodecahedron geometry, and the DOTA complex results in a square antiprism structure. To date, DOTA- and DTPA-based chelators have been used in the vast majority of 86Y bioconjugate strategies, though future studies will no doubt expand the range of chelating moieties employed in these tracers.118–120

89Zr is easily the most recent addition to the family of common PET radiometals, and the relative scarcity of aqueous chelation chemistry studies reflects this fact. The highly cationic Zr4+ center exhibits a strong preference for ligands bearing multiple anionic oxygens and can accommodate up to nine coordinating atoms. The metal makes eight-coordinate, dodecahedral complexes with DTPA (N3O5), EDTA (N2O4 with two additional water ligands), and DOTA (N4O4, though the evidence here is less clear).121,122 However, the overwhelming majority of 89Zr-bioconjugates employ DFO as the chelating ligand.123,124 No solid state or NMR structural studies are available, though DFT calculations suggest that seven- or eight-coordinate species involving one or two water molecules in addition to the ligand's six oxygen donors are most likely.125 Given the considerable potential of 89Zr as a PET radiometal, the continued development of novel high-stability chelating systems is needed.

Conjugation strategies

The final piece of the anatomy of a radiometal PET bioconjugate is the covalent attachment of the chelator to the biomolecule. This link must be stable under physiological conditions and must not significantly compromise the binding strength and specificity of the biomolecule. Three bond-types comprise the overwhelming majority of chelator-biomolecule attachments: peptide, thiourea, and thioether bonds (Fig. 5). The first of these three attachments is formed through the reaction of an activated carboxylic acid and a primary amine, the second via an isothiocyanate and an amine, and the third via a thiol and a maleimide. These are not, however, the only options for the conjugation reaction; the reactions of vinylsulfones with thiols, bromoacetamides with amines, and bromoacetamides with thiols have also been employed in more unique cases. Further still, and more recently, the set of bioorthogonal cycloaddition reactions, broadly termed “click chemistry” reactions, have also been applied to chelator conjugations (vide infra).

Fig. 5.

The three principal types of bioconjugation reactions: (A) peptide bond formation via reaction of a primary amine with a carboxylic acid activated with a succinimidyl ester (NHS), a sulfosuccinimidyl ester (SNHS), tetrafluorophenol (TFP), or a peptide coupling reagent (e.g. HATU, HOBT, etc.); (B) thioether bond formation via reaction of a thiol and a maleimide; and (C) thiourea bond formation via reaction of an isothiocyanate and a primary amine.

To facilitate the formation of these covalent links, bifunctional chelators are often employed. Bifunctional chelators are molecules bearing both metal-binding moieties and either reactive bond-making functionalities or pendant linker arms (Fig. 3 and 4). Given the preponderance of available primary amines and free thiols on many biomolecules, the corresponding activated ester, isothiocyanate, and maleimide groups are usually incorporated into the bifunctional chelator. These molecules can be synthesized and isolated from known chelators (e.g. DOTA-NHS from DOTA), designed and synthesized de novo as bifunctional chelators (e.g. p-SCN-Bn-DOTA), or generated in situ prior to or during the conjugation reaction (e.g. DOTA(tBu)3-NHS from DOTA(tBu)3). In some cases, the modification to a chelator that confers bifunctionality is made at a point that otherwise may have been a metal donor site, for example the addition of an activated ester to a carboxylate arm in DOTA-NHS; in other situations, for example p-SCN-Bn-DOTA, a bifunctional linker is built into the backbone of the chelator so as to minimize any interference with the molecule's ability to bind to metal ions.

Both the number of chelates per biomolecule and the control over their placement can vary widely. The smaller size, well-established protecting group chemistry, and highly controlled and automated synthesis of peptide and nucleic acid vectors often allow for only a single chelator moiety, positioned at one terminus of the oligomer. In contrast, the method by which bifunctional chelators are typically conjugated to antibodies, i.e. the simple incubation of a given number of equivalents of bifunctional chelator with a solution of antibody, results in both a variable number of chelating moieties per antibody and their indeterminate placement on the macromolecule. The number of chelators per antibody can be determined fairly easily using isotopic dilution methods and can be controlled simply by altering the molar ratio of the bifunctional chelator in the conjugation reaction. Generally, more chelators per antibody is preferable, because higher specific activities can be attained. The control and knowledge of chelator placement, however, is harder to come by; the apprehension here, of course, is that the presence of a chelator in the binding region of the antibody can negatively effect its ability to bind to the antigen. Therefore, the goal in antibody conjugation is simple: attach as many chelators per antibody as possible, without compromising the immunoreactivty of the biomolecule.

Significantly, the conjugation of the chelator is almost always performed prior to radiometallation. Thus, the final step in the construction of a PET radiometal bioconjugate is the radiolabeling of the biomolecule-linker-chelator construct. The goal of this final step is the incorporation of as much activity as possible, as quickly as possible, without damaging the biomolecule. Therefore, temperature and pH conditions that favor rapid metallation reactions must be balanced against the concern for the integrity of the biomolecule. For example, while metallating a DOTA-conjugated antibody with 64Cu may proceed most quickly and efficiently at 90 °C, such high temperatures risk denaturing the antibody, and lower temperatures should be employed as a result.

In the preceding pages, it has become clear that the imaging scientist has many choices to make and factors to consider in the development and construction of a radiometal-based PET bioconjugate. In the final section of this perspective, we will provide a practical overview of the design and synthesis strategies used for PET bioconjugates currently described in the literature.

The construction of 68Ga bioconjugates

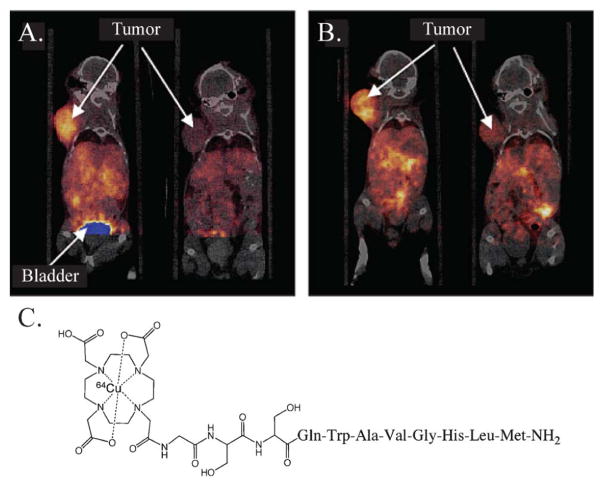

The short half-life and facile production of 68Ga have made it one of the radionuclides of choice for peptide-based PET bioconjugates.126 Tracers have been developed to target a wide array of cancer biomarkers, including epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), gastrin releasing peptide receptor (GRPR), integrin αvβ3, and melanocortin-1 receptor (MC1-R).127–130 However, the 68Ga peptide bioconjugates that have had the greatest impact in the clinic are without question the family of 68Ga-somatostatin analogues (SST).131–134 SST-receptors (SSTR) are over-expressed in neuroendorcrine tumors, prostate carcinomas, breast carcinomas, lymphomas, and small-cell lung cancers, among others, and 68Ga-somatostatin analogues, particularly 68Ga-DOTATOC, have been used to great effect in the imaging of these malignancies (Fig. 6).135

Fig. 6.

A 78-year-old woman with neuroendocrine tumor of unknown primary origin: (A) 68Ga-DOTATOC PET depicts diffuse bone metastases, (B) CT shows only part of widespread bone involvement, and (C) the structure of 68Ga-DOTATOC. Reprinted by permission of the Society of Nuclear Medicine from: D. Putzer, M. Gabriel, B. Henninger, D. Kendler, C. Uprimny, G. Dobrozemsky, C. Decristoforo, R. J. Bale, W. Jaschke and I. J. Virgolini, Journal of Nuclear Medicine, 2009, 50, 1214–1221. Fig. 2.155

A wide variety of chelators, conjugation strategies, and metallation procedures have been employed in the synthesis of 68Ga-labeled peptides (see Table 4 for experimental details and references). DOTA and NOTA-conjugated peptides are most common by a wide margin, though HBED and DFO have also been used. Given the solid-phase synthesis of many peptides, the conjugation of the chelator to the peptide is often performed while the peptide is still attached to a solid resin support. This can be achieved via the manual manipulation of the peptide-coated resin and subsequent incubation with a bifunctional chelator, or using an automated peptide synthesizer. In the latter scenario, a pre-prepared bifunctional chelator is not needed; rather, a monoreactive precursor is added to the automated synthesizer and is coupled to the growing peptide chain via an activated, bifunctional intermediate. Despite the preponderance of solid-phase methods, a number of in situ conjugations have also been reported using bifunctional chelators such as DOTA-NHS, HBED-CC-NHS, p-SCN-Bn-NOTA, and NH2-Bn-NOTA. Generally, peptide and isothiocyanate-based conjugations are performed at a slightly basic pH (8–9.5), due to the participation of a deprotonated primary amine in the bond-forming reactions. Further still, the peptide-chelator conjugates are almost always purified via RPHPLC or C18 cartridge prior to radiolabeling.

Table 4.

Guide to the construction of 68Ga-peptide bioconjugates

| Chelator | Target | Conjugation | Radiometallationa | Purification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOTA | VAP-1185 | Peptide was coupled on the bead to DOTA(tBu)3 using an automated peptide synthesizer. Removal of the peptide from the support, deprotection, and RP-HPLC followed. | 68Ga eluent was adjusted to pH 5.5 with NaOAc, followed by addition of the peptide and incubation for 10–20 min at 90–100 °C. | None reported |

| EGFR127 | Peptide in borate buffer (0.08 M, pH 9.4) was added to dry DOTA-NHS. The pH of the resultant solution was adjusted to 9.0 with additional borate, and the mixture was allowed to stir overnight at RT, followed by RP-HPLC. | Peptide was incubated with 68Ga for 1 min at 90 °C via microwave in either NaOAc (pH 5.0, for use with non-concentrated eluent) or HEPES (pH 4.7, for use with concentrated eluent). | C18 cartridge | |

| GRPR128,186 | Peptide on resin was mixed with a pre-incubated solution of DOTA(tBu)3 and HATU in N-methylpyrrolidone (adjusted to pH 7–8 using DIPEA), followed by cleavage from resin, deprotection, and purification. | 68Ga eluent was dried and redissolved in NaOAc (0.1 M, pH 4.8), followed by addition of the peptide and incubation for 10 min at 90 °C. | C18 cartridge | |

| NTR187 | Peptide was coupled on the bead to DOTA(tBu)3 using an automated peptide synthesizer. Removal of the peptide from the support, deprotection, and purification followed. | Peptide was incubated with 68Ga in NaOAc (concentration not noted, pH 4.5) for 10 min at 95 °C. | None reported | |

| SSTR126,188,189 GRPR126 | Peptide was coupled on the bead to DOTA(tBu)3 using an automated peptide synthesizer. Removal of the peptide from the support, deprotection, and purification followed. | 68Ga eluent was adjusted to pH 3.5–3.8 with 1 M HEPES and incubated with the peptide for 4 min at 90 °C. | C18 cartridge | |

| GRPR190,191 | Peptide was coupled on the bead to DOTA(tBu)3 with HATU using an automated peptide synthesizer. Removal of the peptide from the support, deprotection, and purification followed. | 68Ga eluent was dried and redissolved in NaOAc (0.1 M, pH 4.8), followed by addition of peptide and incubation for 10 min at 90 °C. | C18 cartridge | |

| MC1-R192,193 | Deprotected peptide was dissolved in DMF with DIEA (1.5%) and added to a solution of DOTA(tBu)3 and HATU, which had beenincubated in DMF for 10 min at RT. The resultant solution was stirred at RT for 1 h, followed by precipitation, deprotection, and RP-HPLC. | Peptide was incubated with 68Ga in NaOAc (0.1 M, pH 4.8) for 15 min at 90 °C. | C18 cartridge | |

| SSTR132,133 | DOTA(tBu)3, HATU, and DIEA (1 : 1 : 1) were incubated with DMF for 10 min at RT, followed by addition of the peptide (in DMF with 1.5% DIEA) and stirring for 4 h at RT. Extraction, deprotection, and RP-HPLC followed. | Peptide was incubated with 68Ga in NaOAc (0.4 M, pH 4.8–5.5) for 15–25 min at 95 °C. | C18 cartridge | |

| SSTR134 | Conjugate was purchased from a commercial supplier. | Peptide was incubated with 68Ga in NaOAc (0.1 M, pH 4.5) for 5 min at 95 °C. | C18 cartridge | |

| SSTR135 | Conjugate was purchased from a commercial supplier. | 68Ga eluent in 0.05 M HCl/acetone (2 : 98) was added directly to the peptide in water and incubated for 10 min at 100 °C. | C18 cartridge | |

| SSTR148 | Hydroxylamine-modified peptide was incubated with deprotected acetyl-Bn-DOTA in 1 : 1 CH3CN : H2O (adjusted to pH 4 with TFA) for 18 h at RT, followed by RP-HPLC. | Experimental details were not given, though radiometallation was reported in publication. | None noted | |

| HBED | VEGFR194 |

|

Peptide solution (0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.0) was combined with 10 μL 68Ga solution and 10 μL 2.1 M HEPES, for a final pH of 4.2. Time and temperature were not noted. | Size exclusion chromatography |

| NOTA | VEGFR194,195 | Peptide modified with NHS-PEG group was incubated with p-NH2-Bn-NOTA in carbonate buffer (pH 8.0) for 1 h, followed by C4 RP-HPLC. | Same as above | Size exclusion chromatography |

| αvβ3129,196 GRPR196 | Peptide was incubated with p-SCN-Bn-NOTA in NaHCO3 (0.1 M, pH 9.0) for 5 h at RT, followed by RP-HPLC. | Peptide was incubated with 68Ga in NaOAc (0.1 M, pH 5) for 10–15 min at 40–45 °C. | RP-HPLC | |

| αvβ3197 | Peptide was incubated with p-SCN-Bn-NOTA in NaHCO3 (0.1 M, pH 9.5) for 20 h at RT, followed by RP-HPLC. | 68Ga eluent was adjusted to pH 6.0 with 7% NaHCO3 solution, followed by addition of peptide for 10 min at RT. | RP-HPLC | |

| SSTR131 | Peptide on resin was mixed with a pre-incubated solution of NODAGA(tBu)3 and HATU in N-methylpyrrolidone (adjusted to pH 7–8 using DIPEA), followed by cleavage from resin, deprotection, and RP-HPLC. | Peptide was incubated with 68Ga in NaOAc (0.4 M, pH 5) or HEPES (0.1 M, pH 5.8) for 25 min at 95 °C | C18 cartridge | |

| DFO | SSTR198 | Peptide bearing an activated succinimidyl ester was incubated with DFO mesylate in DMF with DCC/HOBT. Time, temperature, and intermediate purification were not noted. | Peptide (in 0.1% AcOH) was incubated with 68Ga (in 0.1 M NH4OAc, pH 4.5) for 5 min at RT. | None reported |

| DTPA | LDL199,200 | Peptide was reacted with cyclic DTPA anhydride in HEPES buffer (0.1 M, pH 7) for 30 min at RT, followed by size exclusion chromatography. Other buffer types were reported to work for this reaction as well. | 68Ga eluent was dried and re-dissolved in NaOAc (0.4 M, pH 7.0), followed by addition of peptide and incubation for 1–30 min at RT. | Size exclusion chromatography |

| None (HSA)201 | Peptide was incubated with mixed acid anhydride DTPA in aqueous buffer (type and concentration not noted) for 12 h at 4 °C, followed by size exclusion chromatography. | DTPA-HSA solution pH was lowered to 3.1 with 1 M HCl, followed by addition of 68Ga solution (in 1 : 3 EtOH:0.9% NaCl), incubation at RT for 30 min, and final adjustment of pH to 5.5 with 0.1 M NaOH. | Size exclusion chromatography |

Some protocols call for the use of gentisic acid (typically 1–5 mg mL−1) to protect the biomolecule from radiolysis.

The metallation procedures for the peptide-chelator constructs follow the same general course, though the experimental details can vary considerably. The most common buffers for the metallation reaction are NaOAc, HEPES, NaH2PO4/Na2HPO4, and Na2CO3/NaHCO3, and these are used in concentrations ranging from 0.1 M to 0.5 M. The pH for the reaction depends on the chelator: 5–6 for NOTA-based chelators, 3.8–5.5 for DOTA-based chelators, 4–5 for HBED, and 4–5 for DFO. Reaction times and temperatures likewise vary depending on the chelator employed, ranging from 5 min at room temperature for DFO to 25 min at 95 °C and 20 min at 100 °C for DOTA. Often, the radiolabeling reaction is quenched by the addition of free chelator to scavenge excess unreacted radiometal. Finally, the purification of the resultant radiolabeled peptides is most often achieved using C18 cartridges (e.g. Waters Sep-PakTM), RP-HPLC, or size exclusion chromatography.

68Ga has also been used for the labeling of antibody fragments and affibody molecules, though far fewer examples exist than for 68Ga-peptides (see Table 5 for experimental details and references). In these cases, HBED, DOTA, and DTPA have been employed as the chelators of choice. The conjugation reactions are usually performed via the incubation of a solution of antibody fragment with a bifunctional chelator, such as DOTA-NHS or HBEDCC-TFP; however, in the case of one affibody construct, solid phase peptide synthesis and a monoreactive chelator precursor are used as described above for the peptide-based conjugates. Again, all of the macromolecules are purified subsequent to conjugation in order to remove excess chelator. Despite the relatively few examples, the metallation reactions are performed using an array of buffer types (HEPES, phosphate, and NH4OAc) and concentrations (0.1 M to 1.25 M). The time, temperature, and pH of the metallation reactions are all dependent on the identity of the chelator, though in a few cases, these conditions are not noted in the literature. After a suitable incubation, the radiolabeling reaction is often quenched with the addition of free chelator, and in all cases, the resultant radiometallated conjugate is purified with size exclusion chromatography. It thus becomes clear that the labeling of antibody fragments does not yet have standardized methodologies, which is a limitation that will be resolved as more examples of these extremely promising radiotracers come to light.

Table 5.

Guide to the construction of 68Ga-antibody bioconjugates

| Chelator | Target | Conjugation | Radiometallationa | Purification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| HBED | EGFR112 EpCAM112,202 |

|

Antibody solution (0.1 M phosphate buffer, pH 7.0) was combined with 68Ga eluent and 2.1 M HEPES (for a final pH of 4.1–4.5) and incubated for 5–10 min at RT (40 °C). | Size exclusion chromatography |

| DOTA | HER2203–205 | Active DOTA ester was first formed via reaction of DOTA with NHS and subsequently EDC at RT, followed by cooling to 4 °C for 1 h and incubation with antibody fragment solution (0.1 M sodium phosphate, pH 7.0) overnight at 4 °C. Excess DOTA was removed with centrifugal filtration. | Antibody solution (in 1 M NH4OAc stock) was combined with 68Ga eluent (in 0.1 M HCl) and incubated for 15 min at 37 °C. Final reaction pH was not noted. | Size exclusion chromatography |

| HER2206–208 | Affibody was synthesized using standard solid phase synthesis and Fmoc chemistry, followed by conjugation on the bead with DOTA(tBu)3-NHS and subsequent deprotection, removal from the bead, and purification. | 68Ga eluent (in 0.1 M HCl) was combined (∼1 : 1) with affibody in NH4OAc (1.25 M, pH 4.2) and incubated for 10 min at 90 °C. | None noted | |

| DTPA | hPSP209,210 | Antibody was incubated with DTPA cyclic anhydride in aqueous solution (buffer conditions not described), followed by size exclusion chromatography to remove excess DTPA. | 68Ga eluent was evaporated to dryness, reconstituted in NH4OAc buffer (0.1 M), and incubated with antibody. Time, pH, and temperature were not noted. | Size exclusion chromatography |

| DTPA | CD45211 | Antibody was incubated with p-SCN-DTPA, mx-DTPA, or CHX-A″-DTPA in HEPES buffer (0.05 M, pH 9.5) for 20 h at RT, followed by size exclusion chromatography. | 68Ga eluent pH was adjusted to ∼5 with 1 M NaOAc, followed by addition of antibody for 10 min at RT. Reaction was quenched with DTPA. | Size exclusion chromatography |

Some protocols call for the use of gentisic acid (typically 1–5 mg mL−1) to protect the biomolecule from radiolysis.

Finally, a small number of oligonucleotide-based 68Ga-labeled bioconjugates have also been developed (see Table 6 for experimental details and references).136–138 2′-Deoxyphosphodiester (PO), 2′-deoxyphosphorthioate (PS), 2′-O-methyl phosphodiester (OMe), and locked nucleic acid (LNA) oligonucleotides have been synthesized and radiolabeled for gene expression imaging. In all cases, DOTA has been used as the chelator for 68Ga and is incorporated into the oligonucleotide using a DOTA-SNHS bifunctional chelate. Metallations have been performed in either NaOAc or HEPES buffer at pH 4.5–5.5, using short incubations at 90–100 °C (in some cases, microwave-assisted). Finally, the completed, radiolabeled oligonucleotides are typically purified with reverse-phase C4 or C18 cartridges (e.g. Waters Sep-PakTM).

Table 6.

Guide to the construction of radiometallated oligonucleotide bioconjugates

| Chelator | Nuclide | Type | Conjugation | Radiometallation | Purification |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOTA | 86Y | RNA oligomer120 | Amine-modified oligomer was incubated with p-SCN-Bn-DOTA in NaHCO3 buffer (0.7 M, pH 9.0) for 2 h at 40 °C, followed by purification via EtOH precipitation and size exclusion chromatography. | Oligomer was incubated with 86Y in NH4OAc buffer (0.5 M, pH 7.0) for 30–60 min at 90 °C. Reaction quenched with DTPA. | RP-HPLC |

| 86Y | RNA oligomer138 | Amine-modified oligomer was incubated with DOTA-NHS in NaHCO3 buffer (0.7 M, pH 8.1) for 2 h at 40 °C, followed by purification via size exclusion chromatography. | Oligomer was incubated with 86Y in NH4OAc buffer (0.5 M, pH 6.0) for 45 min at 90 °C. Reaction quenched with DTPA. | C18 cartridge | |

| 64Cu | PNA-peptide conjugate55,212 | Amine-modified PNA/peptide conjugate on a solid support was reacted with DOTA(tBu)3 and HATU on a peptide synthesizer for 60 min, followed by cleavage, deprotection, and RP-HPLC. | Conjugate was incubated with 64Cu in NH4OAc buffer (0.1 M, pH 5.5) for 15 min at 90 °C. | RP-HPLC | |

| 64Cu | PNA213 | DOTA(tBu)3 (in N-methylpyrrolidone) was combined with HATU (in DMF) and base (DIEA and 2,6-lutidine in DMF) and subsequently manually reacted with resin-bound PNA for 1 h at RT, followed by cleavage, deprotection, and RP-HPLC. | 64CuCl2 was converted to 64Cu-citrate with NH4-citrate (0.1 M, pH 7.0) and incubated with PNA in buffer for 1–2 h at 60 °C. Reaction quenched with DTPA. | Centrifugal column filtration | |

| 68Ga | RNA oligomer138 | Amine-modified oligomer was incubated with DOTA-NHS in NaHCO3 buffer (0.7 M, pH 8.1) for 2 h at 40 °C, followed by purification via size exclusion chromatography. | Oligomer was incubated with 68Ga in NH4OAc buffer (0.5 M, pH 4.1–4.7) for 45 min at 90 °C. Reaction quenched with DTPA. | C18 cartridge | |

| 68Ga | DNA, PS, and OMe oligomers137,214 | Activated ester was formed via the incubation of DOTA with SNHS and EDC in H2O from 4 °C to RT over 30 min. This mixture was added to amine-modified oligonucleotide solution in carbonate buffer (1 M, pH 9) overnight at 4 °C, followed by purification via size exclusion chromatography and C18 cartridge. | 68Ga eluent was adjusted to pH 5.5 with NaOAc, followed by addition of oligonucleotide for 10 min at 100 °C. | C18 cartridge | |

| 68Ga | DNA-LNA oligomer136,214 | Amine modified oligomer was incubated with DOTA-SNHS in Na2B4O7 buffer (adjusted to pH 8.5–10 with 5 M NaOH) overnight at 4 °C, followed by purification by centrifugal column filtration. | Oligomer was added to purified 68Ga eluent (HEPES, pH 4.6–5.0) and heated to 90 °C for 1 min in a microwave. | C4 cartridge | |

| SBTG2DAP | 64Cu | PNA-peptide conjugate215 | Using an automated peptide synthesizer, diaminopropanoate-modified PNA/peptide conjugate on a solid support was reacted with two equivalents of S-benzoyl thioglycolic acid using HATU and N-methylmorpholine in DMF. | Conjugate was incubated with 64Cu in NH4OAc buffer (0.1 M, pH 5.5) for 30 min at 90 °C. | RP-HPLC |

The construction of 64Cu bioconjugates

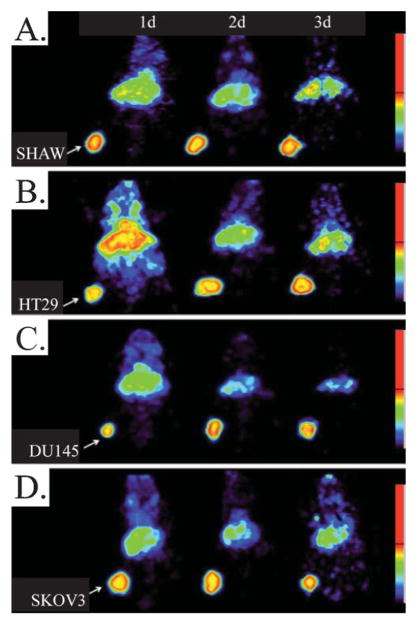

Given its intermediate half-life, favorable decay properties, relative accessibility, and well-established chelation chemistry, 64Cu has become a versatile and widely utilized radiometal for bioconjugate tracers. A variety of 64Cu-peptides have been developed, targeting biomarkers including SSTR, integrin αvβ3, GRPR, MC1-R, integrin α4β1, formyl peptide receptor (FPR), natriuretic peptide receptor (NPR), and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor (VEGFR), among many others (Fig. 7, see Table 7 for experimental details and references). The chelators employed in these conjugates are almost as diverse as the peptides themselves, with DOTA and CB-TE2A leading the way, but with TETA, NOTA, BPM-TACN, and DiamSar also used in some agents. As in the 68Ga peptides, both solid- and solution-phase chelator conjugation strategies have been used. For those involving bifunctional chelators, peptide and isothiocyanate-based conjugations are typically performed at slightly basic pH (8–9.5), because these reactions require a deprotonated primary amine to proceed. Also like the 68Ga cases, the post-conjugation purification of the peptide-chelator construct by RP-HPLC or C18 cartridge is a common practice. The buffers most often chosen for radiometallations are NH4OAc and NaOAc, typically utilized at concentrations ranging from 0.1 M to 0.5 M. However, incubation time, temperature, and pH vary according to the chelator. For example, the radiolabeling of DOTA-based conjugates is typically performed at pH 5–6.5 with 30–60 min incubations at temperatures ranging from room temperature to 95 °C. In contrast, the metallation of DiamSar-based conjugates can be performed at pH 8.0 with a 60 min incubation at room temperature. In many cases, unreacted 64Cu is scavenged after radiolabeling with free chelator (e.g. EDTA or DTPA), and after the successful radiometallation reaction, the overwhelming majority of the 64Cu-peptide conjugates are purified using RP-HPLC.

Fig. 7.

Coronal microPET images with co-registered CT of mice bearing PC-3 xenografts in the axillary thorax at (A) 1 h and (B) 24 h. The mice were injected i.v. with a GRPR-targeting 64Cu-bombesin analogue, 64Cu-DOTA-GSS-BN(7–14). The mice on the left (A) were not injected with blocking agent, while the mice on the right (B) received 100 μg of Tyr4-BN as an inhibitor. Adapted with permission from J. J. Parry, T. S. Kelly, R. Andrews and B. E. Rogers, Bioconjugate Chemistry, 2007, 18, 1110–1117.156 Copyright 2007 American Chemical Society.

Table 7.

Guide to the construction of 64Cu-peptide bioconjugates

| Chelator | Target | Conjugationa | Radiometallationb,c |

|---|---|---|---|

| DOTA | GRPR156,216,217 SSTR218 |

Peptide was coupled to DOTA(tBu)3 or DOTA(tBu)3-NHS using an automated peptide synthesizer and standard Fmoc chemistry, followed by cleavage from the resin, deprotection, and purification. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NH4OAc (0.1 M, pH 5.5) for 30 min at RT. |

| MC1-R219,220 | Peptide was coupled to DOTA(tBu)3 using an automated peptide synthesizer and standard Fmoc chemistry, followed by cleavage from the resin, deprotection, and purification. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NaOAc (0.1 M, pH 5.5) for 60 min at 65 °C. | |

| GRPR221 | Peptide was coupled to DOTA(tBu)3 while still on the peptide synthesizer, followed by cleavage from resin, deprotection, and purification. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NH4OAc (0.4 M, pH 7) for 40 min at 70 °C. | |

| αvβ6222 | Peptide was coupled to DOTA(tBu)3 using HATU/DIEA while peptide was still on the resin, followed by cleavage from the resin, deprotection, and purification. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NH4OAc (1 M, pH 7–8) for 60 min at RT. Reaction quenched with EDTA. | |

| GRPR223 | The method of DOTA incorporation method is unclear; however, a tributyl anhydride of DTPA was used for the acylation of prolines in similar DTPA-modified conjugates, so a similar strategy may have been used here. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NH4OAc (0.5 M, pH 6.5) for 30 min at 80 °C. | |

| αvβ3224–228 GRPR229 VEGFR230,231 UPar232 IL-18R233,c |

DOTA was activated for coupling via reaction with EDC and N- hydroxysulfosuccinimide (SNHS) (10 : 5 : 4) in water (pH 5.5) for 30 min at 4 °C. Peptide (in water, buffer, or saline) was then added to the solution, the pH was adjusted to 8.5 with 0.1 M NaOH, and the resultant solution was stirred for 16 h at 4 °C. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NaOAc (0.1 M, pH 5–6.5) for 30–60 min at 40–50 °C. In some cases the reaction was quenched with EDTA. | |

| MC1-R234,235 αvβ3235,c |

DOTA was activated for coupling via reaction with EDC and SNHS (1 : 1 : 0.8) in water (pH 5.5) for 30 min at 4 °C. Peptide (in phosphate buffer or water) was then added to the solution, the pH was adjusted to 8.5–9.0 with 0.1 M NaOH, and the resultant solution was stirred for 16 h at 4 °C. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NaOAc (0.1 M, pH 5.5) for 60 min at 37–50 °C. | |

| αvβ3236 | DOTA was initially activated for coupling via 1 : 1 : 1 reaction with SNHS and EDC in water (pH 5.5) for 40 min at RT. Peptide in phosphate buffer (30 mM, pH 8.5) was then added to the solution, the pH was adjusted to 8.5 with 0.1 M NaOH, and the resultant solution was stirred for 1 h at RT and then 16 h at 4 °C. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NaOAc (0.1 M, pH 6.3) for 60 min at 45 °C.c | |

| αvβ3224 | Peptide was incubated with (tBu)3 DOTA, HBTU, and Hunig's Base in DMF overnight at RT, followed by deprotection, and purification. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NaOAc (0.5 M, pH 5.5) for 45 min at 50 °C. | |

| NPR237,238 | Peptide was incubated with DOTA-NHS overnight in Na2HPO4 buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.5) at RT. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NH4OAc (0.1 M, pH 5.5) for 60 min at 43 °C. | |

| GC-C239 | Peptide was incubated with DOTA-NHS in HEPES buffer (0.3 M, pH 8.5) overnight at 4 °C. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NH4OAc (0.4 M, pH 6.0) for 1 h at 80 °C. Reaction quenched with EDTA. | |

| FPR240 | Peptide was incubated with DOTA-NHS in water (pH 8.5) overnight at 4 °C. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NH4OAc (0.1 M, pH 5.5) for 30 min at 40 °C. | |

| VEGFR195,241 | p-NH2-Bn-DOTA was activated via reaction with NHS-PEG-maleimide in buffer (15 mM NaOAc, 50 mM Na2CO3, 115 mM NaCl, pH 8.0) at RT for 1 h, followed by quenching of excess maleimide with Tris HCl (1 M, pH 8.0), the addition of peptide, incubation for 1 h at RT, and RP-HPLC with a C4 column.d | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NaOAc (0.1 M, pH 5.3–5.5) for 60 min at 55 °C. Reaction quenched with EDTA.d | |

| Low pH242 | Peptide was incubated with DOTA-maleimide in PBS (pH 7, with 2 mM EDTA) overnight at 4 °C.d | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NH4OAc (0.5 M, pH 5.5) for 30 min at RT. Reaction quenched with EDTA. | |

| CB-TE2A | MC1-R243 | Peptide was coupled to CB-TE2A using standard Fmoc/HBTU chemistry on a peptide synthesizer, followed by cleavage from the resin and deprotection. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NH4OAc (0.1 M, pH 8) for 60 min at 95 °C. |

| SSTR244 | Peptide was reacted while still on the resin with CB-TE2A that had been pre-activated with DIEA and DCC, followed by cleavage from the resin, deprotection, and purification. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NH4OAc (0.1 M, pH 8) for 90 min at 95 °C. | |

| SSTR50,245 | CB-TE2A was dissolved in DMF with DIEA and DIC and stirred for 25 min at RT before adding the solution to the peptide-containing resin. The resultant mixture was agitated for 3 h before filtration, washing, cleavage, and purification. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NH4OAc (0.1 M, pH 8) for 60–90 min at 95 °C. | |

| α4β1246 | CB-TE2A was dissolved in DMF with DIEA and DIC and stirred for 25 min at RT before adding the solution to the peptide-containing resin. The resultant mixture was agitated overnight before filtration, washing, cleavage, and purification. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NH4OAc (0.14 M, pH 7) for 60 min at 95 °C. | |

| GRPR221 | Peptide was coupled to CB-TE2A precursor on peptide synthesizer, followed by cleavage from resin, deprotection, and purification. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NH4OAc (0.4 M, pH 7) for 40 min at 70 °C. | |

| αvβ6222 | CB-TE2A was pre-activated with DIC in DIEA and subsequently reacted with resin-bound peptide for 30 min at RT, followed by cleavage from the resin, deprotection, and purification. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NH4OAc (1 M, pH 7.5–8.5) for 60 min at 95 °C. Reaction quenched with EDTA. | |

| αvβ399,247,248 | Peptide was reacted with CB-TE2A in the presence of DIC and HOBT in anhydrous DMF, followed by deprotection and purification. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NH4OAc (0.1 M, pH 8) for 45–120 min at 95 °C. | |

| TETA | SSTR249,250 | Lys-protected peptide was conjugated in situ to TETA via reaction with DIEA, DIC/HOBT, and HBTU in DMF (time and temperature not noted), followed by deprotection and purification. | Peptide incubated with 64Cu in NH4OAc (0.1 M, pH 5.5) for 30 min at RT. |

| SSTR50 | Peptide was coupled to TETA(tBu)3 using standard Fmoc chemistry on an automated peptide synthesizer. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NH4OAc (0.1 M, pH 5.5) for 1 h at RT. | |

| SSTR245,251–253 | Peptide was coupled to TETA(tBu)3 using standard Fmoc chemistry on an automated peptide synthesizer. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NH4OAc (0.1 M, pH 5.5–6.5) for 1 h at RT-37 °C. | |

| GC-C239 | The activated ester of TETA was formed with EDC and SNHS in sodium phosphate buffer (0.2 M, pH 8.0), followed by the addition of peptide and incubation overnight at 4 °C. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NH4OAc (0.4 M, pH 6.0) for 1 h at 80 °C. Reaction quenched with EDTA. | |

| α3β199,254 | Resin-bound peptide was combined with HBTU, DIEA, and TETA (from DMSO stock) and stirred for 4 h at RT, followed by cleavage from resin and deprotection. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NH4OAc (0.1 M, pH 5.5, 1% BSA) for 15–30 min at RT. Reaction quenched with EDTA. | |

| NOTA | GRPR255,256 | NOTA was activated for coupling via reaction with SNHS and EDC in MES buffer (0.1 M, pH 4.7) for 10 min at RT. Peptide (in phosphate buffer, pH 7.4) was then added to the solution, the pH was adjusted to 7.4 with 10% NaOH, and the resultant solution was stirred for 16 h at RT. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NH4OAc (0.4 M, pH 7.0) for 1 h at 70 °C. Reaction quenched with DTPA. |

| GC-C239 | The activated ester of NOTA was formed with EDC and SNHS in sodium phosphate buffer (0.2 M, pH 8.0), followed by the addition of peptide and incubation overnight at 4 °C. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NH4OAc (0.4 M, pH 6.0) for 1 h at 80 °C. Reaction quenched with EDTA. | |

| GRPR196 αvβ3196 | Peptide was incubated with p-SCN-Bn-NOTA in NaHCO3 buffer (0.1 M, pH 9.0) for 5 h at RT. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NaOAc (0.1 M, pH 6.5) for 15 min at 40 °C. | |

| CPTA | SSTR249 | Lys-protected peptide was conjugated in situ to CPTA via reaction with DIC and HOBT in DMF (time and temperature were not noted), followed by deprotection and purification. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NH4OAc (0.1 M, pH 5.5). Time and temperature were not noted. |

| Bis(2-mercaptoacetamide) | VPAC257,258 | Protected chelator precursors were incorporated into the peptide via automated, solid-phase peptide synthesis using standard Fmoc/DIC/HOBT chemistry. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in glycine buffer (0.2 M, pH 9), SnCl2·2H2O (0.1 M), and HCl (0.05 M) for 20–45 min at 90 °C. |

| BPM-TACN | GRPR259 | Peptide was dissolved in DMF with chelator and HBTU. Subsequently, DIPEA was added, and the resultant solution was stirred for 20 h at RT. | 64Cu in NH4OAc (0.1 M) was added to peptide in 1 : 1 MeCN : H2O and incubated for 30 min at 40 °C. |

| DiamSar | αvβ3247 | Peptide was reacted with DiamSar in the presence of DIC and HOBT in anhydrous DMF, followed by deprotection. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NH4OAc (0.1 M, pH 8.0) for 1 h at RT. |

| AmBaSar | αvβ3260 | AmBaSar was activated for coupling via reaction with EDC and SNHS (1 : 1 : 0.8) in water (pH 5.5) for 30 min at 4 °C. Peptide (in water) was then added to the solution, the pH was adjusted to 8.6 with 0.1 M NaOH, and the resultant solution was stirred for 16 h at RT. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NH4OAc (0.1 M, pH 5.0) for 60 min at RT. |

| αvβ3261 | AmBaSar, HATU, HOAt, and DMSO were stirred at RT for 10 min, followed by the addition of DIPEA and peptide to the solution at 0 °C and incubation for 3 h at RT. | Peptide was incubated with 64Cu in NH4OAc (0.1 M, pH 5.0) for 30 min at RT. |

Unless otherwise noted, peptide-chelator constructs were purified with RP-HPLC or C18 cartridge prior to radiolabeling.

Unless otherwise noted, final radiometallated peptides were purified by RP-HPLC or C18 cartridge.

Some protocols call for the use of gentisic acid (typically 1–5 mg mL−1) to protect the biomolecule from radiolysis.

Purified via size exclusion chromatography

The 12.7 h half-life of 64Cu has allowed it to be utilized in antibody-based conjugates as well as those derived from peptides (see Table 8 for experimental details and references). Indeed, 64Cu-labeled antibody radiotracers have been developed against an array of biomarker antigens, for example human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 (HER2), prostate specific membrane antigen (PSMA), epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR), and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA). As with the 64Cu-peptides, a number of chelators have been used, including DOTA, CPTA, DO3A, TETA, and SarAr. The conjugation strategies for antibodies rely almost exclusively on incubation with bifunctional chelators, either generated in situ or synthesized and isolated (or purchased) beforehand. As is now clearly becoming a trend, the antibody-chelator constructs are almost always purified after conjugation by size exclusion chromatography or centrifugation with a high molecular weight filter membrane. The metallation procedures closely resemble those used for 64Cu-peptides: the most common buffers are NaOAc, NH4OAc, and NH4-citrate at concentrations of 0.1–0.25 M. The incubation time, temperature, and pH vary according to chelator; however, the incubation temperatures seldom rise above 43 °C due to concerns over antibody stability. Again, in many cases, unreacted 64Cu is scavenged after radiolabeling with free chelator (e.g. EDTA or DTPA). Finally, the radiometallated antibody bioconjugates are typically purified via size exclusion chromatography (e.g. HPLC, FPLC, or GE Life Sciences PD-10 columns) or centrifugal column filtration (e.g. Amicon Ultra-4 30,000 MWCO centrifugal filtration units).

Table 8.

Guide to the construction of 64Cu-antibody bioconjugates

| Chelator | Target | Conjugation | Radiometallationa | Purification |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| DOTA | HER2262 | Reduced affibody (in PBS, pH 7.4) was incubated with maleimide-modified DOTA (from a stock in DMSO) for 2 h at RT, followed by purification via overnight dialysis. | Affibody was incubated with 64Cu in NaOAc (0.1 M, pH 5.5) for 1 h at 40 °C. | Size exclusion chromatography |

| HER2263,264 CEA264 |

Activated DOTA was prepared via the combination of DOTA, SNHS and EDC (1 : 1 : 0.1) in water (pH 5.5) for 30 min at 4 °C. This solution was then adjusted to pH 7.3 with Na2HPO4 (0.2 M, pH 9.2), added to antibody (in NaH2PO4, 0.1 M, pH 7.5), and incubated overnight at 4 °C. Centrifugal column filtration followed. | Antibody was incubated with 64Cu in NH4-citrate (0.1 M, pH 5.5) for 50–60 min at 43 °C. Reaction quenched with EDTA. | Size exclusion chromatography | |

| αvβ351 EGFR53,265,266 |

Activated DOTA was prepared via the combination of DOTA, EDC, and SNHS (10 : 5 : 4) in water (pH 5.5) for 30 min at RT. This solution was then added to antibody, the pH of the reaction mixture was adjusted to 8.5 with 0.1 M NaOH, and the solution was incubated overnight at 4 °C. Size exclusion chromatography followed for purification. | Antibody was incubated with 64Cu in NaOAc (0.1 M, pH 6.5) for 1 h at 40 °C. | Size exclusion chromatography | |

| HER2267 | Antibody was incubated with DOTA-NHS (from DMSO stock) in borate-buffered saline (0.1 M pH 8.5) for 16 h at RT, followed by size exclusion chromatography. | Antibody was incubated with 64Cu in NaOAc (0.25 M, pH 6.0) for 1.5 h at 40 °C. Reaction quenched with EDTA. | Size exclusion chromatography | |

| CEA268 TAG-72269 |

Antibody was first dialyzed against PBS (pH 7.2) and NaHCO3 (0.1 M, pH 8.5). DOTA-NHS was then added to the antibody solution and incubated for 2 h at RT, followed by dialysis for purification. | Antibody was incubated with 64Cu in NH4-citrate (0.1 M, pH 5.5) for 45 min at 43 °C. | Size exclusion chromatography | |

| CD22270 | Antibody was incubated with DOTA-NHS in tetramethyl ammonium phosphate (0.1 M, pH 8) for 2.5 h at 37 °C, followed by centrifugal column filtration. | Antibody was incubated with 64Cu in NH4OAc (0.25 M, pH 7) for 1 h at 40 °C. Reaction quenched with EDTA. | Centrifugal column filtration | |

| PSMA271 | Antibody was incubated with DOTA-NHS in Na2HPO4 (0.1 M, pH 7.5) for 24 h at 4 °C, followed by dialysis for purification. | Antibody was incubated with 64Cu in NH4OAc (0.25 M, final pH 5.5) for 40 min at 40 °C. Reaction quenched with DTPA. | None listed | |

| EGFR272 | Antibody was incubated with (tBu)3 DOTA-NHS in Na2HPO4 buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4) for 16 h at 4 °C, followed by centrifugal column filtration. | Antibody was incubated with 64Cu in NH4-citrate (0.1 M, pH 5.5) for 1 h at 40 °C. | Size exclusion chromatography | |

| L1-CAM273 | Antibody in phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 8) was added to DOTA-NCS variants. The pH was adjusted to 9–10 with Na3PO4, and the solution was incubated for 16 h at 4 °C, followed by centrifugal column filtration. | Antibody was incubated with 64Cu in NaOAc (0.1 M, pH 5.5) for 1 h at RT. Reaction quenched with EDTA. | Size exclusion chromatography | |

| CPTA | L1-CAM273,274 | Antibody was incubated with CPTA-NHS in sodium phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7) for 2 h at RT, followed by centrifugal column filtration. | Antibody was incubated with 64Cu in NaOAc (0.1 M, pH 5.5) for 1 h at RT. Reaction quenched with EDTA. | Size exclusion chromatography |

| DO3A | L1-CAM273 | Antibody in phosphate buffer (0.1 M, pH 8) was added to DO3A-Bn-NCS. The pH was adjusted to 9–10 with Na3PO4, and the solution was incubated for 16 h at 4 °C, followed by centrifugal column filtration. | Antibody was incubated with 64Cu in NaOAc (0.1 M, pH 5.5) for 1 h at RT. Reaction quenched with EDTA. | Size exclusion chromatography |

| CEA268 |

|

Antibody was incubated with 64Cu in NH4-citrate (0.1 M, pH 5.5) for 45 min at 43 °C. | Size exclusion chromatography | |

| CEA268 | Antibody was incubated DO3A-VS in PBS (adjusted to pH 9.0 with 0.1 M NaOH) for 18 h at RT, followed by dialysis. | Antibody was incubated with 64Cu in NH4-citrate (0.1 M, pH 5.5) for 45 min at 43 °C. | Size exclusion chromatography | |

| TETA | CC17,275 | Antibody in ammonium phosphate (0.1 M, pH 8.0) was incubated with excess Br-benzyl-TETA and fresh 2-iminothiolane in triethanolamine (50 mM) for 30 min at 37 °C, followed by centrifugal column filtration. | Antibody was incubated with 64Cu in NH4-citrate (0.1 M, pH 5.5) for 15–30 min at RT. | Size exclusion chromatography |

| SarAr | GD254 | Antibody was incubated with SarAr and EDC in NaOAc (0.1 M, pH 5.0) for 30 min at 37 °C, followed by size exclusion HPLC. | Antibody was incubated with 64Cu in NaOAc (0.1 M, pH 5.0) for 30 min at 37 °C. | None reported |

Some protocols call for the use of gentisic acid (typically 1–5 mg mL−1) to protect the biomolecule from radiolysis.

SATA = S-acetylthioacetate

A small number of peptide nucleic acid (PNA) and hybrid PNA-oligopeptide 64Cu-labeled conjugates have also been created for mRNA-targeted imaging (see Table 6 for experimental details and references). These conjugates have employed either DOTA or SBTG2DAP as the chelating moieties, with solid-phase Fmoc synthesis techniques analogous to those for peptides used to incorporate the chelators into the oligomers. Radiolabeling reactions have been performed in either NH4OAc or NH4-citrate buffer (pH 5.5–6.0), with incubations of 15–120 min at temperatures ranging from 60 to 90 °C.

The construction of 86Y bioconjugates