Abstract

Placental abruption (PA), a pregnancy-related vascular disorder, is a leading cause of maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality. The success of identifying genetic susceptibility loci for PA, a multi-factorial heritable disorder, has been limited. We conducted a genome-wide association study (GWAS) and candidate gene association study using 470 PA cases and 473 controls from Lima, Peru. Genotyping for common genetic variations (single nucleotide polymorphisms, SNPs) was conducted using the Illumina Cardio-Metabo Chip platform. Common variations in 35 genes that participate in mitochondrial biogenesis (MB) and oxidative phosphorylation (OS) were selected for the candidate gene study. Regression models were fit to examine associations of each SNP with risk of PA. In pathway analyses, we examined functions and functional relationships of genes represented by the top GWAS hits. Genetic risk scores (GRS), based on top hits of the GWAS and candidate gene analyses, respectively, were computed using the risk allele counting method. The top hit in the GWAS analyses was rs1238566 (empirical P-value=1.04e-4 and FDR-adjusted P-value=5.65E-04) in FLI-1 gene, a megakaryocyte-specific transcription factor. Networks of genes involved in lipid metabolism and cell signaling were significantly enriched by the 51 genes whose SNPs were among the top 200 GWAS hits (P-value <2.1e-3). SNPs known to regulate MB (e.g. CAMK2B, NR1H3, PPARG, PRKCA, and THRB) and OP (e.g., COX5A, and NDUF family of genes) were associated with PA risk (P-value <0.05). GRS was significantly associated with PA risk (trend P-value <0.001 and 0.01 for GWAS and candidate gene based GRS, respectively). Our study suggests that integrating multiple analytical strategies in genetic association studies can provide opportunities for identifying genetic risk factors and novel molecular mechanisms that underlie PA.

Keywords: Placental abruption, genome-wide association study, pathway analyses, candidate gene, genetic risk score

Introduction

Placental abruption (PA) is the separation of the placenta from the uterus prior to delivery of the fetus [1-3]. This pregnancy-related vascular disorder complicates about 1% of all births and is associated with significant complications in the mother and her offspring [1-3]. The success of identifying genetic susceptibility loci for PA, a multi-factorial heritable disorder, has been limited [4-13]. Findings from the only PA-related genome-wide association study (GWAS) from our team provided suggestive evidence supporting associations of variations in maternal cardiometabolic genes with risk of PA. We previously identified variations in SNPs in novel (SMAD2 MIR17HG, and DGKB) and candidate (AGT, KDR, F2, and THBD) genes that may be associated with PA [14]. However, the previous GWAS study was conducted among 253 PA cases and 258 controls, limiting the study’s statistical power to identify significant associations. The need to conduct larger PA-related GWAS studies and the opportunities they provide to investigate genetic variations in recently recognized molecular pathways that lead to PA, such as mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative stress, motivated the current study.

Impaired placental function and oxidative phosphorylation,pathways implicated in the pathogenesis of PA, have their origins extending to mitochondrial dysfunction [15,16]. Mitochondria are semi-autonomous cytoplasmic organelles of the eukaryotic system that produce adenosine triphosphate by the coupling of oxidative phosphorylation to respiration, providing a major source of energy to the cell [15,16]. Approximately 1,500 proteins encoded by nuclear DNA (nDNA) regulate mitochondrial biogenesis and maintain mitochondrial structure and function by regulating oxidative phosphorylation, apoptosis, and mitochondrial DNA replication,transcription, and translation [17]. While most previous work on genetic variations and mitochondrial dysfunction has focused on variations in mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA), recently, investigators have noted that single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) in nDNA may be associated with mitochondrial dysfunction (and related disease conditions) through subtle changes in encoded proteins that alter mitochondrial biogenesis and/or oxidative phosphorylation activity [18]. On the basis of this emerging literature and our recent observation that PA risk is associated with increased mtDNA copy number abundance [19], a marker of mitochondrial dysfunction, we hypothesized that variations in mitochondrial biogenesis- and oxidative phosphorylation-related genes are associated with PA risk.

The current study extends our previous GWAS study by doubling the size of study participants (470 PA cases and 473 controls), testing of specific hypothesis linking genetic variation in mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation-related genes with PA risk, and employing multiple analytical approaches to investigate genetic risk factors of PA.

Methods

Study setting and study population

This study was conducted as part of the Peruvian Abruptio Placentae Epidemiology (PAPE) study. The study setting and study population were described before [14]. Briefly, study participants were recruited and enrolled among women who were admitted for obstetrical services to the Hospital Nacional Dos de Mayo, Instituto Especializado Materno Perinatal, and Hospital Madre-Niño San Bartolomé in Lima, Peru, between August 2002 and May 2004 and between September 2006 and September 2008.

Hospital admission and delivery logs were monitored daily to identify PA cases among new admissions to antepartum, emergency room, and labor and delivery wards of participating hospitals. PA was diagnosed based on evidence of retroplacental bleeding (fresh blood) entrapped between the decidua and the placenta or blood clots behind the placenta and any two of the following: (i) vaginal bleeding in late pregnancy not due to placenta previa or cervical lesions; (ii) uterine tenderness and/or abdominal pain; (iii) fetal distress or death. Controls were selected from among pregnant women who delivered at participating hospitals during the study period and did not have a diagnosis of PA in the current pregnancy.

Institutional Review Boards of participating institutions approved the project protocol. All participants provided written informed consent.

Data collection

Trained research personnel conducted participant interviews using standardized structured questionnaires to collect information on socio-demographic characteristics and risk factors including maternal age, marital status, employment status during pregnancy, medical history, and smoking and alcohol consumption (both before and during the current pregnancy). A brief physical examination was conducted to measure maternal height, weight, and mid-arm circumference. Medical records were reviewed to abstract information on course and outcomes of the pregnancy [14]. Blood specimens collected from 470 PA cases and 473 controls were processed for assessment of genetic variation as described below.

DNA extraction and genotyping

The Gentra PureGene Cell kit for DNA preparations (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) was used to extract DNA from blood specimens collected from 470 PA cases and 473 controls. Genotyping to characterize genome-wide variation in cardiovascular and metabolism genes was conducted using the Illumina Cardio-Metabochip (Illumina Inc, San Diego, CA) platform [14]. Briefly, the Cardio-Metabo Chip is a high-density custom array that captures DNA variation at regions previously related to diseases and traits relevant to metabolic and atherosclerotic-cardiovascular endpoints using 217,697 SNPs.

Data quality control and preprocessing

Rigorous quality control procedures were applied to the DNA before analyses [20]. Individuals were excluded (n=48) if they had genotyping failure for more than 10% of the sites. SNPs were excluded if the minor allele frequency was less than 1%, if the SNP failed to be genotyped in more than 10% of the study population, or if the SNP was not in Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium among controls (critical P=0.0001). After these QC procedures, a total of 124,499 SNPs and 470 PA cases and 473 controls remained for analyses. Population stratification was assessed using the genomic inflation factor [21] and adjustment for the first four principal components in regression models[22].

Candidate gene/SNP selection

A total of 35 genes that were involved in mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation were selected based on literature (Supplementary Table 1). There were a total of 322 SNPs representing these genes in the Cardio-Metabo Chip. Of these 322 SNPs, 310 SNPs were excluded because they were rare (12 SNPs with MAF <1%) and/or in significant linkage disequilibrium (298 SNPs with R2 >0.8) with another SNP in the set. A total of 11 SNPs in 9 candidate genes remained for further analysis.

Statistical analyses

Logistic regression models were fit to evaluate associations between each SNP and risk of PA in both the genome-wide and candidate gene analyses. Bonferroni correction was used to account for multiple testing (P-value threshold 0.05/124,499 SNPs=8.03e-6) in overall genome-wide level analyses. In addition to assessment of the empirical P-value, we also computed false discovery rate (FDR) for a less conservative assessment of statistical significance [23]. For the secondary candidate SNP-PA association analyses, we used P <0.05 as a cut-off to determine statistical significance.

Ingenuity Pathway Analyses (IPA, Ingenuity, Redwook, CA) was used to evaluate functions and functional relationships of genes represented by top 200 hits from our current PA GWAS analysis. In IPA, each gene identifier was mapped to its corresponding gene object in the Ingenuity Pathways Knowledge Base (IPKB). These genes were overlaid onto a global molecular network developed from information contained in the IPKB. Gene-enrichment of networks was assessed using network score based on a modified Fisher’s exact test. The network score, negative log of P-values of Fisher tests, was used to rank biological significance of gene function networks in relation to PA.

Using risk allele counting method, we computed genetic risk scores (GRS) for top hits from the GWAS and candidate gene analyses [24]. The top 10-15 risk alleles that were common (higher MAF) and not in LD with other SNPs in the set were selected from each analysis. We assumed the additive genetic risk model corresponding to a linear increase of PA risk to the presence of 0, 1, and 2 risk alleles. In addition, we assumed equal risk of PA conferred by each locus. Participants were categorized into four groups defined by the 25th, 50th, and 75th percentile GRS scores among control participants (i.e., Group 1: 0-25%ile, Group 2: 25-50%ile, Group 3: 50-75%ile, and Group 4: 75-100%ile). Regression models were then fit to examine associations of the genetic score with PA risk using Group 1 (0-25%ile group) as a referent.

Statistical analyses were conducted using PLINK v1.07, SAS, and R software. Pathway analyses were conducted using IPA v6 software [25].

Results

Selected socio-demographic and medical/obstetric characteristics of participants are shown in Table 1. Average maternal age of PA cases and controls was 28 years. PA cases and controls were similar with respect to their frequency of high school completion and employment during pregnancy. They also had comparable mean pre-pregnancy BMI (average 24 kg/m2 for both). However, compared with controls, PA cases were more likely to be smokers during pregnancy, and have a history of preeclampsia, eclampsia or PA. As expected, PA cases delivered low birth weight infants more frequently and had shorter gestational lengths, compared with controls.

Table 1.

Socio-demographic and reproductive characterstics and infant outcomes in the study population, Lima, Peru

| Maternal Characteristics | Placental Abruption | |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Cases (n=470) | Controls (n=473) | |

| Maternal age at delivery, years* | 27.7 (6.7) | 27.7 (6.6) |

| <35 | 380 (11.2) | 388 (10.8) |

| ≥35 | 90 (18.0) | 85 (17.4) |

| Nulliparous | 41 (8.4) | 12 (2.41) |

| Less than High school education | 353 (72.3) | 356 (71.3) |

| Employed during pregnancy | 213 (43.5) | 223 (44.8) |

| Planned pregnancy | 195 (40.5) | 207 (42.2) |

| No prenatal vitamin | 154 (31.6) | 148 (29.7) |

| Smoked during pregnancy | 18 (3.7) | 9 (1.8) |

| Alcohol use during pregnancy | 21 (4.2) | 26 (5.3) |

| Pre-pregnancy BMI, kg/m2 * | 23.8 (3.8) | 23.7 (3.9) |

| <18.5 | 24 (5.3) | 15 (3.1) |

| 18.5-24.9 | 288 (64.0) | 322 (67.5) |

| 25.0-29.9 | 111 (24.7) | 103 (21.6) |

| ≥30.0 | 27 (6.0) | 37 (7.8) |

| Chronic hypertension | 22 (4.6) | 12 (2.4) |

| Preeclampsia or Eclampsia | 134 (27.9) | 37 (7.4) |

| History of placental abruption | 5 (1.1) | 0 (0) |

| Infant birthweight, grams* | 2430 (863) | 3158 (690) |

| Gestational age at delivery, weeks* | 35.4 (4.1) | 38.3 (2.7) |

Mean (standard deviation), otherwise number (%).

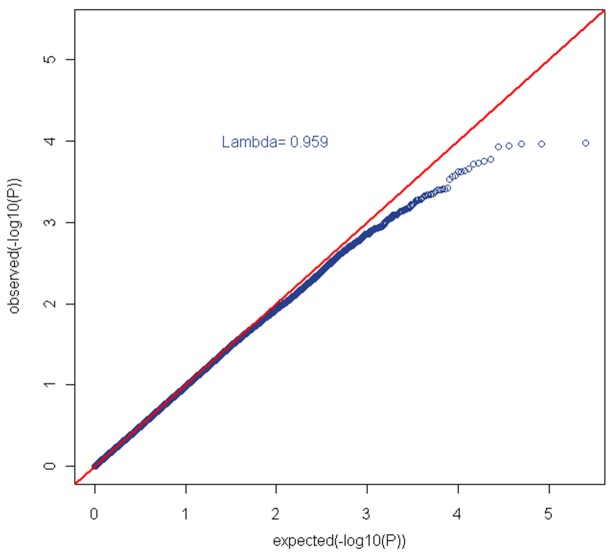

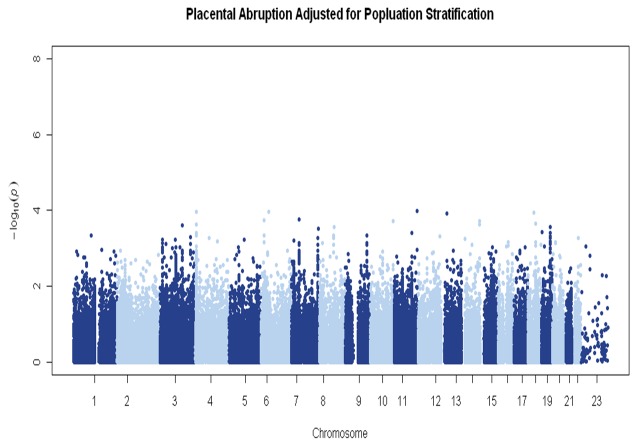

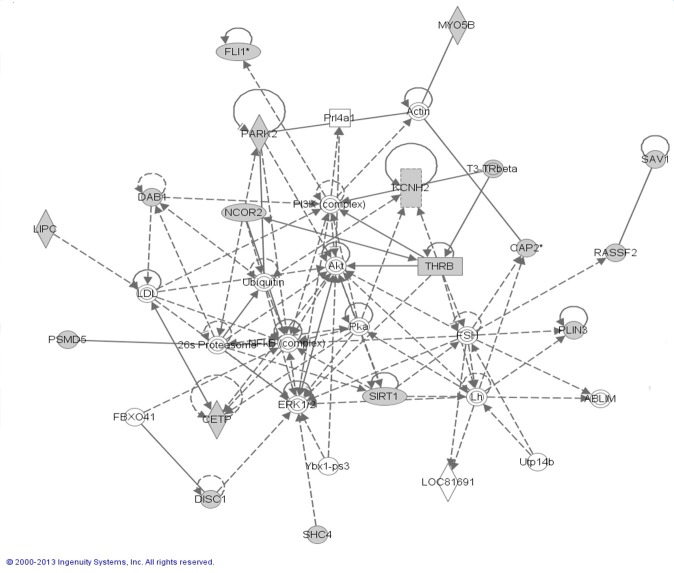

We did not observe significant genomic inflation (λ=0.96) (Figure 1). In genome-wide analyses, none of the P-values for SNP-PA associations surpassed the stringent criteria for significant associations (Bonferroni corrected P-value 8.03e-6) (Figure 2). FLI-1 gene (rs1238566, P-value=1.04e-4, FDR=5.65e-4), a megakaryocyte-specific transcription factor,was the top hit in the GWAS analyses. Genes represented by the top GWAS hits are shown in Table 2. A total of 51 genes were represented by the top 200 GWAS hits (with P-values <2.1e-3, FDR <2.0e-3); and, these were evaluated for functions and functional relationships using IPA. The top networks enriched by these genes included networks of lipid metabolism (score=40, P-value=4.25e-18) and cell signaling (score=26, P-value=5.11e-12) (Table 3 & Figure 3). In additional to these 51 genes, the top networks included other well-described genes in lipid metabolism (e.g., FLI-1, CETP, LIPC, and THRB) and cell signaling (e.g., Akt, NFKB, and PI3K) (Figure 3). In candidate gene analyses, SNPs in genes related to mitochondrial biogenesis (e.g., CAMK2B, NR1H3, PPARG, PRKCA, and THRB) or oxidative phosphorylation (e.g., COX5A, and NDUF family of genes) were significantly associated with PA risk (P-values <0.05) (Table 4).

Figure 1.

Q-Q plot (λ=0.96).

Figure 2.

Manhattan plot of genome-wide association study of placental abruption.

Table 2.

Top hits of analyses examining genome-wide genetic variations and placental abruption risk

| Gene | SNP | Minor Allele | MAF | Odds Ratio | Empirical P-value | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FLI1 | rs1238566 | G | 0.34 | 1.46 (1.21-1.77) | 1.05E-04 | 5.65E-04 |

| C6orf108 | rs7832 | A | 0.07 | 2.14 (1.48-3.18) | 1.08E-04 | 5.65E-04 |

| LOC647946 | rs10502722 | C | 0.41 | 0.7 (0.59-0.85) | 1.13E-04 | 5.65E-04 |

| ZAR1L | rs206136 | G | 0.11 | 0.56 (0.41-0.74) | 1.19E-04 | 5.65E-04 |

| CAP2 | rs1320995 | C | 0.35 | 0.67 (0.56-0.83) | 1.77E-04 | 5.65E-04 |

| TECPR2 | rs4900536 | G | 0.35 | 0.70 (0.57-0.83) | 1.89E-04 | 5.65E-04 |

| DPP6 | rs2024366 | G | 0.14 | 1.65 (1.27-2.17) | 2.97E-04 | 7.55E-04 |

| PLIN3 | rs3760950 | A | 0.38 | 1.42 (1.18-1.72) | 3.74E-04 | 7.55E-04 |

| CAP2 | rs1320994 | G | 0.37 | 0.71 (0.58-0.85) | 4.48E-04 | 7.55E-04 |

| PSMD5 | rs10760117 | A | 0.18 | 1.52 (1.18-1.88) | 4.53E-04 | 7.55E-04 |

| FRRS1 | rs951125 | G | 0.21 | 0.67 (0.53-0.84) | 4.59E-04 | 7.55E-04 |

| NCOR2 | rs12582168 | G | 0.43 | 0.72 (0.60-0.87) | 4.77E-04 | 7.55E-04 |

| EDIL3 | rs350477 | A | 0.24 | 0.67 (0.55-0.86) | 6.03E-04 | 7.76E-04 |

| KIF16B | rs8117456 | C | 0.22 | 1.48 (1.16-1.81) | 6.71E-04 | 7.76E-04 |

| CAP2 | rs9383287 | G | 0.38 | 0.72 (0.59-0.86) | 6.73E-04 | 7.76E-04 |

| CETP | rs891144 | A | 0.18 | 0.66 (0.51-0.83) | 6.94E-04 | 7.76E-04 |

| MYO5B | rs17716496 | C | 0.17 | 0.66 (0.52-0.84) | 7.04E-04 | 7.76E-04 |

| KIF16B | rs1028540 | A | 0.39 | 1.38 (1.15-1.66) | 7.35E-04 | 7.76E-04 |

| LOC253039 | rs4837796 | G | 0.19 | 1.48 (1.16-1.83) | 8.10E-04 | 8.10E-04 |

Abbreviations: MAF = Minor Allele Frequency in Controls.

Table 3.

SNPs in candidate genes and risk of placental abruption

| Gene | SNP | Minor Allele | MAF | Odds Ratio | Empirical P-value | FDR |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAMK2B | Chr7:44221559 | G | 0.27 | 0.77 (0.63-0.95) | 0.01 | 0.02 |

| NR1H3 | Chr11:47237338 | A | 0.16 | 1.31 (1.02-1.68) | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| PPARG | Chr3:12309555 | A | 0.16 | 1.44 (1.11-1.84) | 0.005 | 0.02 |

| PPARG | Chr3:12336385 | A | 0.47 | 1.19 (0.99-1.44) | 0.07 | 0.04 |

| PPARG | Chr3:12440243 | A | 0.18 | 1.30 (1.02-1.62) | 0.03 | 0.04 |

| PRKCA | Chr17:61738444 | G | 0.29 | 0.82 (0.67-1.02) | 0.06 | 0.04 |

| THRB | rs9814223 | A | 0.35 | 0.83 (0.68-0.99) | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| COX5A | Chr15:73013139 | G | 0.14 | 0.76 (0.59-1.00) | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| NDUFA10 | Rs4149549 | A | 0.21 | 1.23 (0.98-1.54) | 0.07 | 0.04 |

| NDUFA12 | Rs11107847 | A | 0.43 | 0.83 (0.70-1.01) | 0.05 | 0.04 |

| NDUFC2 | Rs627297 | C | 0.17 | 0.74 (0.59-0.95) | 0.01 | 0.02 |

Abbreviations: MAF = Minor Allele Frequency in Controls.

Figure 3.

Top network represented by genes represented by top hits of GWAS analysis.

Table 4.

Significant networks represented by top GWAS hits

| Molecules in Network | Score | Focus Molecules (#) | Top Functions | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26s Proteasome, ABLIM, Actin, Akt, CAP2, CETP, DAB1, DISC1, ERK1/2, FBXO41, FLI1, FSH, KCNH2, LDL, Lh, LIPC, LOC81691, MY058, NCOR2, NFKB, PARK2, PI3K, PLN3, Prl4a1, PSMD5, RASSF2, SAV1, SHC4, SIRT1, T3-Trbeta, THRB, Ubiquitin, Utp14b, Ybx1-ps3 | 40 | 17 | Small Molecule Biochemistry, Lipid Metabolism, Cellular development | 4.25E-18 |

| AMICA1, BTN2A2, BTN3A1, BTN3A2, C12orf29, C6orf108, CC2D2A, DDX6OL, DPP6, EML2, FAM108B1, FSTL4, GABARAP, GSDMD, IFNG, KCTD7, KIF16B, LUZP1, MORC2, NLN, PHB, PHLDB2, PITPNC1, PLEKHO2, RAB12, RAB20, RAB43, RNASE7, SCAPER, SLC16A13, SMAGP, TECPR2, TGM2, UBC, ZFX | 26 | 12 | Cell Death and Survival, Cell-to-Cell Signaling and Interaction,Cellular Function and Maintenance | 5.11E-12 |

The networks were generated through the use of Ingenuity Pathways Analysis (Ingenuity® Systems, www.ingenuity.com). Each gene identifier was mapped to its corresponding gene object in the Ingenuity Pathways Knowledge Base (IPKB) and overlaid onto a global molecular network developed from information contained in the IPKB. Scores, corresponding to degree of enrichment, are negative log of p-values of Fisher test. Genes in bold (focus molecules) are genes that are represented by top hit SNPs in our genome-wide association study of placental abruption.

Two GRS were computed using 14 SNPs identified in the GWAS analyses and 11 SNPs in 9 genes identified in the candidate gene association analyses, respectively (Supplementary Table 2). Both GRS were significantly associated with risk of PA (linear trend P-values <0.001 and 0.01 for the genome-wide GRS and the candidate GRS, respectively) (Table 5). Participants in the highest GRS Group (Group4), GRS >17.1 in the GWAS analysis and GRS >10.0 in the candidate gene analysis, had 5.45 (95% CI: 3.68-8.06) and 1.91 (95% CI: 1.20-3.06) fold higher risk of PA, respectively, compared with participants in the lowest GRS Group, Group 1 (GRS <10.9 in the GWAS analysis and GRS <8.0 in the candidate gene analysis)(Table 5).

Table 5.

Genetic risk score (GRS) and risk of placental abruption

| Genetic Risk Score (GRS)* | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||||

| Group 1 0-25%ile | Group 2 25-50%ile | Group 3 50-75%ile | Group 4 75-100%ile | P | |

| Genome-wide Association Analysis | |||||

| Intervals | <10.9 | 10.9-13.9 | 14.0-17.0 | ≥17.1 | |

| Cases, n (%) | 49 (10) | 45 (10) | 140 (30) | 236 (50) | |

| Controls, n (%) | 142 (30) | 69 (15) | 138 (29) | 124 (26) | |

| OR (95% CI)** | 1.00 | 1.85 (1.12-3.05) | 2.90 (1.97-4.33) | 5.45 (3.68-8.06) | <0.001 |

| Candidate Gene Analysis | |||||

| Intervals | <8 | 8-8.9 | 9-9.9 | ≥10 | |

| Cases, Number (%) | 34 (8) | 72 (17) | 113 (27) | 197 (47) | |

| Controls, Number (%) | 58 (14) | 80 (19) | 103 (25) | 175 (42) | |

| OR (95% CI)** | 1.00 | 1.55 (0.91-2.64) | 1.88 (1.14-3.11) | 1.91 (1.20-3.06) | 0.01 |

GRS computed from 14 SNPs that are top hits from GWAS analyses, and 11 SNPs that are top hits from the candidate gene association analyses.

Odds ratios (and 95% confidence intervals) from logistic regression models adjusted for age, sex, and population admixture, linear trend P-values.

Discussion

In genome-wide and candidate gene association analyses, we identified several SNPs, genes, and pathways that are related to PA risk. In the GWAS analysis among PA cases and controls, the top hit was rs1238566 (P-value=1.04e-4) in FLI-1 gene. None of the SNPs reached statistical significance after correction for multiple testing using the conservative Bonferroni correction. Networks enriched by 51 genes represented by the top 200 GWAS hits (P-values <2.1e-3) included networks of lipid metabolism (e.g., FLI-1, CETP, LIPC, and THRB) and cell signaling (e.g., Akt, NFKB, and PI3K).In candidate gene analysis, SNPs in genes participating in mitochondrial biogenesis (e.g. CAMK2B, NR1H3, PPARG, PRKCA, and THRB) or oxidative phosphorylation (e.g., COX5A, and NDUF family of genes) were significantly associated with PA risk (P-values <0.05). GRS computed using risk alleles identified from both the GWAS and candidate gene analyses were associated with risk of PA.

Most previous studies of common genetic variations and risk of PA [26-30] were small candidate gene studies. The only other GWAS by our group [14] identified several novel and candidate SNPs that are potentially related to PA risk. Several of the top SNPs identified in the previous study were significantly associated with PA risk, at the P <0.05 level, in our expanded sample. These included SNPs in the DGKB (chr7:14154194, P-value=6e-04), SMAD2 (chr-18:453999981, P-value=2e-04), and MIR17HG (rs4773624, P-value=0.003). In addition, a SNP in previously identified candidate gene, the CETP gene (rs891144, P-value=6.94E-04), was among the top hits in the GWAS analyses in our study. Ali et al. [31], in their case-control study among women with idiopathic PA, placenta previa, and normal pregnancies, found that the B2 allele frequency in idiopathic PA was higher than its frequency in placenta previa or normal pregnancy (P-value <0.05).

The top GWAS hit in our study, rs1238566, is a SNP in the FLI-1 gene, a megakaryocyte-specific transcription factor. The A allele of this SNP is weakly (P=0.08) associated with increased expression of the FLI-1 gene in lymphoblastoid cell lines [32]. Coagulation defects, where megakaryocytes play key roles, such as decreased platelets, elevated prothrombin time, decreased fibrinogen levels, and elevated fibrin split products, have closely been associated with the clinical events of PA. Therefore, the finding that a variation in the FLI-1 gene may be associated with PA risk is of high significance.

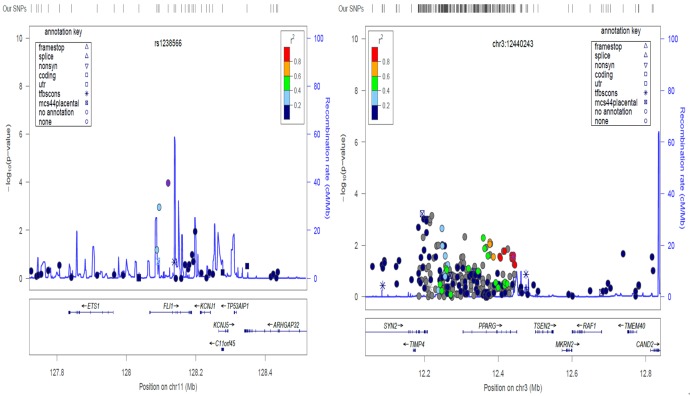

We assessed recombination rates and LD of SNPs near putative associated variants identified in the genome-wide and candidate gene association analyses. The regional SNP association plots illustrating the complex genetic architecture for rs1238566 (from the genome-wide analysis) and chr3:12440243 (from the candidate gene analysis) are shown in Figure 4. Other genes in the neighborhood of these SNPs, such as the ETS1 gene that has been shown to be involved in connective tissue metabolism, fibrosis, inflammation, and related disease conditions (e.g. SLE), are putative candidates as genetic susceptibility factors of PA [33,34].

Figure 4.

Regional SNP association plot for the top GWAS SNP rs1238566 and candidate SNP chr3:12440243. Estimated local recombination rate and –log10 P-values are plotted in blue on the right and left side of the y-axis, respectively. The genomic position is shown on the x-axis. Linkage disequilibrium (r2) of a nearby SNP with the index SNP is shown by purple color.

In pathway analyses of genes represented by top hits of the GWAS analyses, lipid metabolism and cell signaling networks were identified. Dyslipidemia has been associated with a number of pregnancy complications that include preeclampsia, a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy that has been closely related to PA [35]. Recent evidence also points to lipid-related high risk profiles (e.g., higher cholesterol, LDL, and lower HDL) for cardiovascular diseases among women with history of PA, supporting potential risk similarities of PA with other cardiovascular diseases in the general population [36]. However, significant gap remains in our understanding of direct relationships between lipid abnormalities, or genetic factors that underlie these abnormalities and risk of PA. Cell signaling which is a broad category that encompasses a diverse set of cellular interactions is a critical component of cellular function.As described in our previous report, and supported by current findings, several candidates (such as the SMAD family of genes and the DPP6 gene) in cell-signaling pathways may have roles in risk of PA [14]. Further research into the extent of their roles and the specific signaling pathways that are important is warranted.

Several mechanisms may explain why variation in mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation related genes might contribute to mitochondrial dysfunction and PA. Oxidative stress-induced damage to mitochondrial structural elements (e.g., lipid membranes) may alter mitochondrial gene expression and promote a deficiency in oxidative phosphorylation [37]. Variation in genes related to mitochondrial biogenesis may confer susceptibility to damage from oxidative stress and variation in genes related to oxidative phosphorylation may accentuate the deficiency in oxidative phosphorylation that results from mitochondrial dysfunction. In the current candidate gene association analyses, we found that several SNPs in mitochondrial biogenesis (e.g., CAMK2B, NR1H3, PPARG, PRKCA, and THRB) and oxidative phosphorylation (e.g., COX5A, and NDUF family of genes) related genes are associated with risk of PA. Of these, the PPARG and NDUF genes were represented by several SNPs. The role of PPARG in placentation has been well documented [38,39]. Interestingly, investigators have put forth thesis indicating that PPARG mediates defective placentation (e.g., inhibition of trophoblast invasion) that results from oxidized LDL in cytotrophoblasts of villous and extravillous cells [40]. The NDUF gene, encoding the NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase protein,is part of the enzyme complex in the electron transport chain of mitochondria [41]. While the gene and other genes in the family, and their variants have been reported in relation to other diseases such as AIDS and prostate cancer, to our knowledge, no previous study reported variation in this gene in relation to pregnancy complications [42,43]. Future studies are needed to further explore the role of these sets of genes in placentation and PA risk.

GRS based on risk allele genotypes of multiple SNPs have been used to summarize genetic effects among ensemble of markers that do not individually achieve significance in association studies [44]. In the current study, both GRS computed using top hits of SNPs in the GWAS and candidate gene analyses were significantly associated with risk of PA. One potential limitation of our GRS-based analyses is the fact that we used the same data set for training and testing. We conducted cross-validation to assess the utility of the GRS [45]. Based on that test, we observed that the GWAS based GRS had an agreement of 64% with the true value (PA cases and controls), while the candidate-based GRS score has an agreement of 55% with the true value. However, sensitivity of the GWAS-based GRS score was 82% while sensitivity of the candidate-based GRS score was 71%. Specificity for the two scores, respectively, was 46% and 34%. A significant overestimation of the PA risk was observed. Based on previous suggestions by Thomsen et al. [45], the validity of our GRS scores should be examined in other study populations with different indices of diseases.

Other limitations of our study merit consideration.Although our study is the largest to date on the topic, we may still be underpowered to detect significant associations between genetic variations, particularly less common variations, and risk of PA. This is particularly true for small effect sizes. Potential misclassifications of sub-clinical PA may further limit our study power. Absence of a replication cohort and lack of follow-up functional studies are other limitations of our study. Finally, generalizability of our findings should be confirmed by studies that are conducted in study populations that differ in genetic and other characteristics from ours.

Some strengths of our study deserve mention. We used multiple (GWAS, pathway, candidate, and GRS) analytic approaches to examine associations between genetic susceptibility and risk of PA. These different approaches provided us with the opportunity to identify genetic risk that may be associated with PA, a multigenic complex disorder. In our candidate gene analyses, we have specifically drawn attention to mitochondrial biogenesis and oxidative phosphorylation, an emerging little explored pathway that is significant in placental pathophysiology, pregnancy complications, and outcomes. Our study was conducted among a high-risk under-investigated study population and relatively less problem of population stratification are other strengths of the study.

In summary, our study suggests that integrating multiple genomic analytical strategies provides opportunities for identifying novel biological pathways for exploring the underlying molecular mechanisms for PA. In addition, our GRS analyses support the promise of using genetic association studies in PA risk prediction. Future studies that involve larger discovery and replication samples, functional follow-up of confirmed PA-associated variants, and risk-prediction, among others, may enhance efforts to understand PA pathomechanisms and facilitate the development of prevention strategies.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by grants from the National Institute of Health, the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (R01HD059827, T32HD052462) and the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (K01HL10374).

Disclosure of conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

Supporting Information

References

- 1.Ananth CV, Oyelese Y, Yeo L, Pradhan A, Vintzileos AM. Placental abruption in the United States, 1979 through 2001: temporal trends and potential determinants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:191–198. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.05.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Flenady V, Koopmans L, Middleton P, Frøen JF, Smith GC, Gibbons K, Coory M, Gordon A, Ellwood D, McIntyre HD. Major risk factors for stillbirth in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2011;377:1331–1340. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)62233-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rasmussen S, Irgens LM, Bergsjø P, Dalaker K. The occurrence of placental abruption in Norway 1967-1991. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand. 1996;75:222–228. doi: 10.3109/00016349609047091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ananth CV, Peltier MR, Chavez MR, Kirby RS, Getahun D, Vintzileos AM. Recurrence of ischemic placental disease. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;110:128–133. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000266983.77458.71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ananth CV, Savitz DA, Williams MA. Placental abruption and its association with hypertension and prolonged rupture of membranes: a methodologic review and meta-analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;88:309–318. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00088-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Benedetto C, Marozio L, Tavella AM, Salton L, Grivon S, Di Giampaolo F. Coagulation disorders in pregnancy: acquired and inherited thrombophilias. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1205:106–117. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2010.05674.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kramer MS, Usher RH, Pollack R, Boyd M, Usher S. Etilogic Determinants of Abruptio Placentae. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;89:221–226. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(96)00478-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kupferminc MJ, Eldor A, Steinman N, Many A, Bar-Am A, Jaffa A, Fait G, Lessing JB. Increased frequency of genetic thrombophilia in women with complications of pregnancy. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:9–13. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199901073400102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Misra DP, Ananth CV. Risk factor profiles of placental abruption in first and second pregnancies:heterogeneous etiologies. J Clin Epidemiol. 1999;52:453–461. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(99)00017-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Toivonen S, Keski‐Nisula L, Saarikoski S, Heinonen S. Risk of placental abruption in first‐degree relatives of index patients. Clin Genet. 2004;66:244–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2004.00294.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.van der Molen EF, Arends GE, Nelen WL, van der Put NJ, Heil SG, Eskes TK, Blom HJ. A common mutation in the 5, 10-methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase gene as a new risk factor for placental vasculopathy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:1258–1263. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.105199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.de Vries JI, Dekker G, Huijgensb P, Jakobs C, Blomberg B, van Geijn HP. Hyperhomocysteinaemia and protein S deficiency in complicated pregnancies. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1997;104:1248–1254. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1997.tb10970.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams MA, Lieberman E, Mittendorf R, Monson RR, Schoenbaum SC. Risk factors for abruptio placentae. Am J Epidemiol. 1991;134:965–972. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a116181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moore A, Enquobahrie DA, Sanchez SE, Ananth CV, Pacora PN, Williams MA. A genome-wide association study of variations in maternal cardiometabolic genes and risk of placental abruption. Int J Mol Epidemiol Genet. 2012;3:305. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Crimi M, Rigolio R. The mitochondrial genome,a growing interest inside an organelle. Int J Nanomedicine. 2008;3:51. doi: 10.2147/ijn.s2482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wallace DC. Mitochondrial DNA mutations in disease and aging. Environ Mol Mutagen. 2010;51:440–450. doi: 10.1002/em.20586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Modica-Napolitano JS, Kulawiec M, Singh KK. Mitochondria and human cancer. Curr Mol Med. 2007;7:121–131. doi: 10.2174/156652407779940495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Singh KK, Kulawiec M. Cancer Epidemiology. Springer; 2009. Mitochondrial DNA polymorphism and risk of cancer; pp. 291–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams MA, Sanchez SE, Ananth CV, Hevner K, Qiu C, Enquobahrie DA. Maternal blood mitochondrial DNA copy number and placental abruption risk: results from a preliminary study. Int J Mol Epidemiol Genet. 2013;4:120. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laurie CC, Doheny KF, Mirel DB, Pugh EW, Bierut LJ, Bhangale T, Boehm F, Caporaso NE, Cornelis MC, Edenberg HJ. Quality control and quality assurance in genotypic data for genome‐ wide association studies. Genet Epidemiol. 2010;34:591–602. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Devlin B, Roeder K. Genomic control for association studies. Biometrics. 1999;55:997–1004. doi: 10.1111/j.0006-341x.1999.00997.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu C, DeWan A, Hoh J, Wang Z. A comparison of association methods correcting for population stratification in case–control studies. Ann Hum Genet. 2011;75:418–427. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-1809.2010.00639.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Benjamini Y, Yekutieli D. The Control of the False Discouvery Rate in Multiple Testing Under Dependency. Ann Statist. 2001;29:1165–1188. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iwata M, Maeda S, Kamura Y, Takano A, Kato H, Murakami S, Higuchi K, Takahashi A, Fujita H, Hara K. Genetic risk score constructed using 14 susceptibility alleles for type 2 diabetes is associated with the early onset of diabetes and may predict the future requirement of insulin injections among Japanese individuals. Diabetes Care. 2012;35:1763–1770. doi: 10.2337/dc11-2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Purcell S, Neale B, Todd-Brown K, Thomas L, Ferreira MA, Bender D, Maller J, Sklar P, De Bakker PI, Daly MJ. PLINK: a tool set for whole-genome association and population-based linkage analyses. Am J Hum Genet. 2007;81:559–575. doi: 10.1086/519795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Malinowska A, Chmurzynska A. Polymorphism of genes encoding homocysteine metabolism–related enzymes and risk for cardiovascular disease. Nutr Res. 2009;29:685–695. doi: 10.1016/j.nutres.2009.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nurk E, Tell GS, Refsum H, Ueland PM, Vollset SE. Associations between maternal methylenetetrahydrofolate reductase polymorphisms and adverse outcomes of pregnancy: the Hordaland Homocysteine Study. Am J Med. 2004;117:26–31. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2004.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Parle‐McDermott A, Mills JL, Kirke PN, Cox C, Signore CC, Kirke S, Molloy AM, O’Leary VB, Pangilinan FJ, O’Herlihy C. MTHFD1 R653Q polymorphism is a maternal genetic risk factor for severe abruptio placentae. Am J Med Genet A. 2005;132:365–368. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.30354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Trabetti E. Homocysteine, MTHFR gene polymorphisms,and cardio-cerebrovascular risk. J Appl Genet. 2008;49:267–282. doi: 10.1007/BF03195624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zdoukopoulos N, Zintzaras E. Genetic risk factors for placental abruption: a HuGE review and meta-analysis. Epidemiology. 2008;19:309–323. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181635694. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ali AFM, Fateen B, Ezzet A, Badawy H, Ramadan A, El-tobge A. Idiopathic abruptio placentae is associated with a molecular variant of the cholesteryl ester transfer protein gene. Obstetrics & Gynecology. 2000;95:S37–S38. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liang L, Morar N, Dixon AL, Lathrop GM, Abecasis GR, Moffatt MF, Cookson WO. A cross-platform analysis of 14,177 expression quantitative trait loci derived from lymphoblastoid cell lines. Genome Res. 2013;23:716–726. doi: 10.1101/gr.142521.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Feng W, Chumley P, Hua P, Rezonzew G, Jaimes D, Duckworth MW, Xing D, Jaimes EA. Role of the Transcription Factor Erythroblastosis Virus E26 Oncogen Homolog-1 (ETS-1) as Mediator of the Renal Proinflammatory and Profibrotic Effects of Angiotensin II. Hypertension. 2012;60:1226–1233. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.112.197871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Geisinger MT, Astaiza R, Butler T, Popoff SN, Planey SL, Arnott JA. Ets-1 Is Essential for Connective Tissue Growth Factor (CTGF/CCN2) Induction by TGF-β1 in Osteoblasts. PLoS One. 2012;7:e35258. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Enquobahrie DA, Williams MA, Butler CL, Frederick IO, Miller RS, Luthy DA. Maternal plasma lipid concentrations in early pregnancy and risk of preeclampsia. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:574–581. doi: 10.1016/j.amjhyper.2004.03.666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Veerbeek JH, Smit JG, Koster MP, Uiterweer EDP, van Rijn BB, Koenen SV, Franx A. Maternal Cardiovascular Risk Profile After Placental Abruption. Hypertension. 2013;61:1297–1301. doi: 10.1161/HYPERTENSIONAHA.111.00930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lee HC, Wei YH. Mitochondrial role in life and death of the cell. J Biomed Sci. 2000;7:2–15. doi: 10.1007/BF02255913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Barak Y, Nelson MC, Ong ES, Jones YZ, Ruiz-Lozano P, Chien KR, Koder A, Evans RM. PPAR gamma is required for placental, cardiac, and adipose tissue development. Mol Cell. 1999;4:585–595. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80209-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ruebner M, Langbein M, Strissel PL, Henke C, Schmidt D, Goecke TW, Faschingbauer F, Schild RL, Beckmann MW, Strick R. Regulation of the human endogenous retroviral Syncytin‐1 and cell–cell fusion by the nuclear hormone receptors PPARγ/RXRα in placentogenesis. J Cell Biochem. 2012;113:2383–2396. doi: 10.1002/jcb.24110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fournier T, Pavan L, Tarrade A, Schoonjans K, Auwerx J, Rochette‐Egly C, Evain‐Brion D. The Role of PPAR‐γ/RXR‐α Heterodimers in the Regulation of Human Trophoblast Invasion. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;973:26–30. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Loublier S, Bayot A, Rak M, El-Khoury R, Bénit P, Rustin P. The NDUFB6 subunit of the mitochondrial respiratory chain complex I is required for electron transfer activity: A proof of principle study on stable and controlled RNA interference in human cell lines. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;414:367–372. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.09.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hendrickson SL, Lautenberger JA, Chinn LW, Malasky M, Sezgin E, Kingsley LA, Goedert JJ, Kirk GD, Gomperts ED, Buchbinder SP. Genetic variants in nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes influence AIDS progression. PLoS One. 2010;5:e12862. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0012862. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wang L, McDonnell SK, Hebbring SJ, Cunningham JM, St Sauver J, Cerhan JR, Isaya G, Schaid DJ, Thibodeau SN. Polymorphisms in mitochondrial genes and prostate cancer risk. Cancer Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:3558–3566. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Dudbridge F. Power and predictive accuracy of polygenic risk scores. PLoS Genet. 2013;9:e1003348. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1003348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Thomsen TF, McGee D, Davidsen M, Jørgensen T. A cross-validation of risk-scores for coronary heart disease mortality based on data from the Glostrup Population Studies and Framingham Heart Study. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:817–822. doi: 10.1093/ije/31.4.817. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.