Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a common inflammatory skin disease characterized by wet, oozing, erythematous, pruritic lesions in the acute stage and xerotic, lichenified plaques in the chronic stage. It frequently coexists with asthma and allergic rhinitis, sharing some mechanistic features with these diseases as part of the "atopic march." Controversy exists as to whether immune abnormalities, epidermal barrier defects, or both are the primary factors responsible for disease pathogenesis. In AD patients, there is often a coexisting irritant or allergic contact dermatitis (ICD or ACD, respectively), which clinically are sometimes difficult to distinguish from AD. ACD shares molecular mechanisms with AD, including increased cellular infiltrates and cytokine activation (Gittler et al., 2012). In this issue of the Journal, Newell et al. used an experimental contact sensitization model with dinitrochlorobenzene (DNCB) to gain insight into the unique immune phenotype of AD patients (Newell et al., 2013).

Epidermal barrier defects characterize lesional and non-lesional AD skin

The stratum corneum, including terminal differentiation proteins such as filaggrin (FLG), corneodesmosin, and loricrin, is a first-line defense against irritants and allergens. The genomic expression of key barrier molecules, which comprise the epidermal differentiation complex on chromosome 1q21, have been previously shown to be downregulated in AD patients in both lesional but also non-lesional skin (Suárez-Fariñas et al., 2011). Furthermore, frequent mutations in the FLG gene (found in up to 30–50% of AD patients) have been associated with severity of AD [as identified by the Scoring of AD (SCORAD) index]. These differentiation abnormalities contribute to the barrier defect in AD, ultimately resulting in increased transepidermal water loss, xerosis, and greater penetration of various agents (Gittler et al., 2012). In humans, FLG deficiency has been linked to increased risk of the other atopic diseases, as well as to greater susceptibility to common triggers of AD (including allergens and microbes). Murine models with reduced FLG exhibit greater passive transfer of protein allergens and reduced thresholds to irritants (Irvine et al., 2011). These studies provide the basis for the “outside-in" hypothesis of AD, which states that transfer of external triggers across a dysfunctional barrier elicits the disease’s characteristic immune responses. While FLG and other defects in the barrier have been linked to AD pathogenesis, there are notable limitations to this hypothesis. For example, an inverse correlation has been established between the expression levels of several terminal differentiation molecules and AD disease severity (as measured by the SCORAD index) (Suárez-Fariñas et al., 2011). This raises the possibility of a reactive epidermal barrier to a primary immune insult. Furthermore, impressive reductions in key terminal differentiation molecules, extending far beyond FLG, have been found even in non-lesional AD skin. Also, a majority of AD patients do not harbor FLG mutations, and even those with them have been shown to outgrow the disease (Guttman-Yassky et al., 2011). Collectively, these observations suggest that barrier dysfunction is not the sole contributor to disease pathogenesis.

AD is primarily Th2 and Th22 polarized

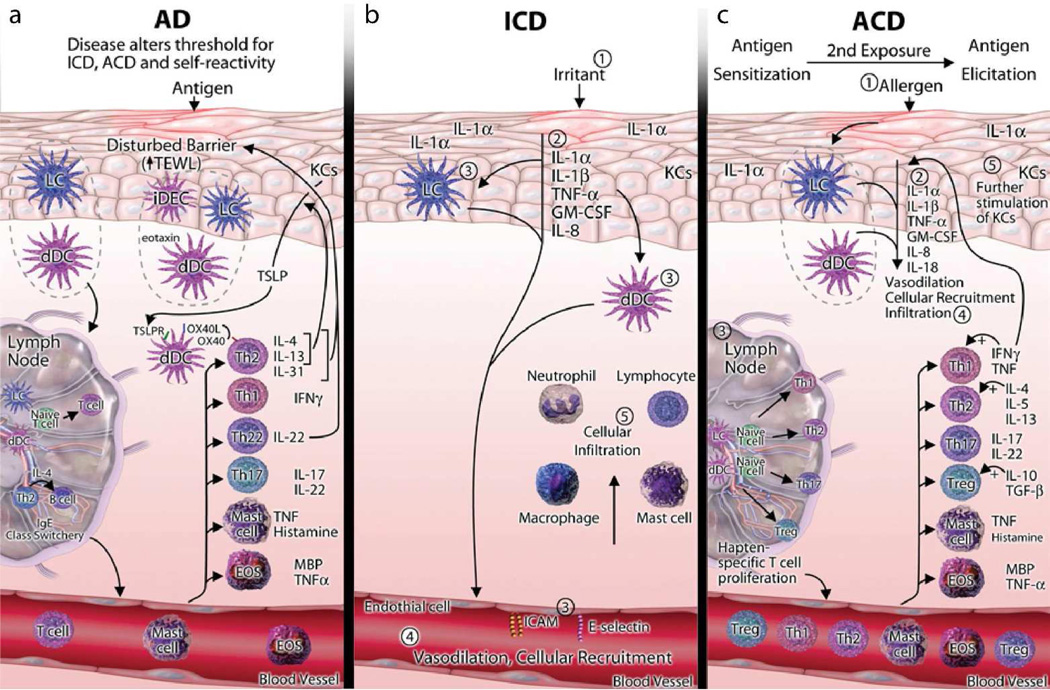

The historical immune paradigm for AD characterized it largely as a Th2-mediated disease with high levels of interleukin (IL)-4, IL-13, and Th2-polarizing chemokines (i.e. CCL17, CCL18, CCL22). Recent work has implicated additional key Th2-associated cytokines and factors, including IL-31, thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), and OX40. Th2 signaling has been demonstrated to produce many of the molecular findings seen in AD skin, with the exception of the characteristic epidermal hyperplasia. Allergen-specific Th2 T-cells can be found in AD but not in non-atopic controls (Ardern-Jones et al., 2007). More recently, Th22 T-cells and their cytokine, IL-22, have been shown to play a key role in the pathogenesis of AD, potentially accounting for the increased epidermal thickness. Langerhans cells (LCs) and/or CD11c+ dermal dendritic cells (dDCs), which are upregulated in AD, have been associated with both Th2 and Th22 polarization, possibly explaining the predominance of these T-cell subsets in the disease (Fujita et al., 2011; Gittler et al., 2012). AD has also been shown to have a Th1 component in the chronic phase, and a Th17 component in the acute stage (Gittler et al., 2012; Guttman-Yassky et al., 2011). Thus, concepts of the AD immune phenotype have become increasingly complex, with evidence for activation of several pathways beyond the Th2 axis (Figure 1a). Recently, the “background” or non-lesional disease phenotype has also been shown to display increased cellular infiltrates (i.e. T-cells, DCs, and LCs) as well as increased expression of inflammatory mediators, compared to normal skin (Suárez-Fariñas et al., 2011), possibly influenced by systemic cytokine activation and genetic or environmental factors that remain to be identified.

Figure 1.

Immune mechanism in the pathogenesis of ICD, ACD, and AD. (a) In patients with AD, a disturbed epidermal barrier leads to increased permeation of antigens, which encounter Langerhans cells (LCs), inflammatory dendritic epidermal cells (iDECs), and dermal dendritic cells (dDCs), activating TH2 T-cells to produce IL-4 and IL-13. DCs then travel to lymph nodes, where they activate effector T-cells and induce IgE class-switching. IL-4 and IL-13 stimulate KCs to produce TSLP. TSLP activates OX40 ligand–expressing dDCs to induce inflammatory TH2 T-cells. Cytokines and chemokines, such as IL-4, IL-5, IL-13, eotaxins, CCL17, CCL18, and CCL22, produced by TH2 T-cells and DCs stimulate skin infiltration by DCs, mast cells, and eosinophils (EOS). TH2 and TH22 T-cells predominate in patients with AD, but TH1 and TH17 T-cells also contribute to its pathogenesis. The TH2 and TH22 cytokines (IL-4/IL-13 and IL-22, respectively) were shown to inhibit terminal differentiation and contribute to the barrier defect in patients with AD. Thus both the barrier defects and immune activation alter the threshold for ICD, ACD, and self-reactivity in patients with AD. (b) In patients with ICD, exposure to an irritant exerts toxic effects on KCs, activating innate immunity with release of IL-1α, IL-1β, tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-α, granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GM-CSF), and IL-8 from epidermal KCs. In turn, these cytokines activate LCs, dDCs, and endothelial cells, all of which contribute to cellular recruitment to the site of KC damage. Infiltrating cells include neutrophils, lymphocytes, macrophages, and mast cells, which further promote an inflammatory cascade. (c) In the sensitization phase of ACD, similar to ICD, allergens activate innate immunity through KC release of IL-1α, IL-1β, TNF-α, GM-CSF, IL-8, and IL-18, inducing vasodilation, cellular recruitment, and infiltration. LCs and dDCs encounter the allergen and migrate to the draining lymph nodes, where they activate hapten-specific T-cells, which include TH1, TH2, TH17 and regulatory T (Treg) cells. These T-cells proliferate and enter the circulation and site of initial exposure, along with mast cells and EOS. On reencountering the allergen, the elicitation phase occurs, in which the hapten-specific T-cells, along with other inflammatory cells, enter the site of exposure and, through release of cytokines and consequent stimulation of KCs, induce an inflammatory cascade. MBP, major basic protein (reprinted from Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Vol 131, Issue 2, JK Gittler, JG Krueger, and E Guttman-Yassky, 300–313, copyright 2013 with permission from Elsevier).

The interplay between barrier defects and immune abnormalities

In addition to its role as a physical barrier, the epidermis contributes to inflammatory responses. Keratinocytes (KCs) in AD are key producers of TSLP, which acts via OX40L on dDCs to polarize T-cells towards a Th2 phenotype (Gittler et al., 2012). Th2 cytokines IL-4, IL-13, and IL-31, along with Th22-derived IL-22, have been demonstrated to supress terminal differentiation molecules (i.e. FLG and LOR), ultimately disrupting barrier function (Figure 1a). These findings led to the “inside-out” hypothesis of AD, suggesting that the epidermal changes are reactions to Th2 and Th22 signaling (Guttman-Yassky et al., 2011). Recent studies have shown that the barrier and immune defects are interactive players in the pathogenesis of AD (Gittler et al., 2012). Moreover, immune activation through epicutaneous antigen exposure is an important mechanism that perpetuates the inflammation and immune-driven epidermal changes that characterize AD. Understanding the mechanisms of immune sensitization to topical antigens in AD patients may help us to understand the factors that participate in disease onset.

New insights into AD pathogenesis obtained through contact sensitization

Molecules such as DNCB and other haptens provide a useful model for epicutaneous allergen exposure through intact or disturbed skin. Newell et al. elegantly showed equivalent penetration of DNCB, an almost universally sensitizing epicutaneous allergen, in AD patients, regardless of FLG mutation status. Through sensitization with DNCB, they showed Th2 polarization and attenuated hypersensitivity reactions in non-lesional AD skin compared to skin from healthy volunteers (Newell et al., 2013). Their data show that the unique immune phenotype of AD patients is perpetuated by allergen challenge regardless of mutation status.

Several important questions remain unanswered about contact sensitization in atopic individuals. While DNCB provides an excellent experimental model for studying contact hypersensitivity, it is not an allergen that leads to ACD in a clinical setting. Penetration of “true” allergens that typically affect allergic individuals, such as nickel and rubber accelerators, may be more influenced by barrier defects and a patient’s genetic background than DNCB. While Newell et al. demonstrated that background immune abnormalities in AD skin contribute to the distinct Th2 polarization upon DNCB challenge, their approach does not address whether this holds true for commonly encountered allergens. Furthermore, compared to DNCB’s almost universal potential for sensitization, clinically relevant allergens affect different individuals with varying degrees of severity, and therefore immune differences among AD patients might influence allergen reactivity. In addition, both ACD and ICD are more common in AD patients. Although ACD is a delayed-type hypersensitivity reaction relying on antigen presentation in sensitized individuals, it has been suggested that ICD (Figure 1b) is a prerequisite for ACD (Figure 1c) (Bonneville et al., 2007). ICD, which occurs via activation of innate immunity by KCs upon exposure to toxic irritants, may decrease the threshold for generating a ACD reactions. This threshold may be decreased further in AD patients with defective barriers, increasing overall rates of allergen sensitization. However, despite the increased prevalence of allergic responses in AD, the resulting immune reactions are attenuated in these patients as compared with controls. This hyporesponsiveness may possibly be explained by altered LC or dDC function or differences in T-cell subsets in AD patients compared to non-atopic individuals.

Although it remains unclear where the primary abnormality lies in skewing T-cells towards a Th2 phenotype in AD, insight is provided by DNCB-induced Th2 polarization through non-lesional AD skin, which we previously characterized with barrier and immune defects. Collectively, these concepts suggest that increased antigen penetration and/or altered antigen-presenting cell function in non-lesional AD skin result in an initial Th2-polarized response that can amplify over time into clinically inflamed lesions. Newell et al.'s finding that ACD in the context of AD is immunologically distinct, showing a Th2 rather than the conventional Th1 polarization, highlights the central role of the Th2 pathway in disease pathogenesis. In fact, emerging studies targeting IL-4R in AD patients show promising initial results (Simpson, 2013), supporting the pathogenic role of Th2. Future studies are needed to address the role of allergic sensitization to common allergens in programming the AD immune phenotype.

Clinical Implications/Pullquote.

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is Th2-polarized and often co-occurs with contact dermatitis.

A new study in this month's issue using contact sensitization provides insights into the Th2 skewing of AD.

Th2 skewing is independent of filaggrin status.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

ND was supported by grant number 5UL1RR024143-02 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the NIH, and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. NG was supported by NIH MSTP grant GM07739. EGY was supported by the Dermatology Foundation Physician Scientist Career Development Award.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- AD

atopic dermatitis

- ACD

allergic contact dermatitis

- ICD

irritant contact dermatitis

- DNCB

dinitrochlorobenzene

- FLG

filaggrin

- KCs

keratinocytes

- IL-

interleukin-

- TSLP

thymic stromal lymphopoietin

- LCs

Langerhans cells

- dDCs

dermal dendritic cells

- Th-

helper T-cells

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors state no conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- Ardern-Jones MR, Black AP, Bateman EA, et al. Bacterial superantigen facilitates epithelial presentation of allergen to T helper 2 cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:5557–5562. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700733104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonneville M, Chavagnac C, Vocanson M, et al. Skin contact irritation conditions the development and severity of allergic contact dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2007;127:1430–1435. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujita H, Shemer A, Suárez-Fariñas M, et al. Lesional dendritic cells in patients with chronic atopic dermatitis and psoriasis exhibit parallel ability to activate T-cell subsets. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128:574–582. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gittler JK, Krueger JG, Guttman-Yassky E. Atopic dermatitis results in intrinsic barrier and immune abnormalities: Implications for contact dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131:300–313. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.06.048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guttman-Yassky E, Nograles KE, Krueger JG. Contrasting pathogenesis of atopic dermatitis and psoriasis--Part II: Immune cell subsets and therapeutic concepts. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:1420–1432. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2011.01.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Irvine AD, McLean W, Leung DYM. Filaggrin Mutations Associated with Skin and Allergic Diseases. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:1315–1327. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1011040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newell L, Polak ME, Perera J, et al. Sensitization via healthy skin programmes Th2 responses in individuals with atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 2013 Mar 25; doi: 10.1038/jid.2013.148. advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simpson EL. Treatment of Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Atopic Dermatitis With REGN668/SAR231893 (IL-4Rα mAb): Analysis of Pooled Phase 1B Studies Shows Significant Improvement in Skin Disease and Pruritus. AAD Annual Meeting: Late-breaking sessions; Presented at the AAD Annual Meeting: Late-breaking sessions; 2013. (Abstr.) [Google Scholar]

- Suárez-Fariñas M, Tintle SJ, Shemer A, et al. Nonlesional atopic dermatitis skin is characterized by broad terminal differentiation defects and variable immune abnormalities. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;127:954–964. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2010.12.1124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]