Abstract

Objective

To investigate factors hypothesized to moderate the effects of a dissonance-based eating disorder prevention program, including initial elevations in thin-ideal internalization, body dissatisfaction, eating disorder symptoms, and older participant age.

Method

Adolescent female high school and college students with body image concerns (N = 977; M age = 18.6) were randomized to a dissonance-based thin-ideal internalization reduction program or an assessment-only control condition in three prevention trials.

Results

The intervention produced (a) significantly stronger reductions in thin-ideal internalization for participants with initial elevations in thin-ideal internalization and a threshold/subthreshold DSM-5 eating disorder at baseline, (b) significantly greater reductions in eating disorder symptoms for participants with versus without a DSM-5 eating disorder at baseline, and (c) significantly stronger reductions in body dissatisfaction for late adolescence/young adulthood versus mid-adolescent participants. Baseline body dissatisfaction did not moderate the intervention effects.

Conclusion

Overall, intervention effects tended to be amplified for individuals with initial elevations in risk factors and a DSM-5 eating disorder at baseline. Results suggest that this prevention program is effective for a broad range of individuals, but is somewhat more beneficial for the subgroups identified in the moderation analyses.

Keywords: eating disorders, prevention, moderation, risk factors

Subthreshold and threshold eating disorders affect about 10% of young women, often show a chronic course, and are associated with functional impairment, mental health service utilization, medical complications, and increased risk for future obesity, depression, suicide, substance abuse, anxiety disorders, and health problems (Johnson, Cohen, Kasen, & Brook, 2002; Stice, Marti, & Rohde, in press; Wilson, Becker, & Heffernan, 2003). Because more than 50% of individuals seeking treatment for eating disorders receive a diagnosis for Eating Disorders Not Otherwise Specified (EDNOS; Fairburn & Bohn, 2005), the American Psychiatric Association suggested multiple changes for the upcoming fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Eating disorders (www.dsm5.org/Pages/Default.aspx). Symptoms with limited empirical support (amenorrhea) were eliminated, the frequency and duration criteria for bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder were reduced, and new diagnostic categories were also added (e.g., binge eating disorder, purging disorder, atypical anorexia nervosa, and subthreshold bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder). Despite the significance of eating disorders, less than a third of individuals with eating disorders receiving treatment (Johnson et al., 2002; Stice et al., in press), suggesting it would be useful to develop effective eating disorder prevention programs.

Mounting empirical support has emerged for a dissonance-based eating disorder prevention program (Stice, Mazotti, Weibel, & Agras, 2000). The dissonance intervention program is a selective prevention program that targets girls and young women at elevated risk for developing an eating disorder because of body dissatisfaction. Whereas universal prevention aims to reach an entire population, selective prevention focuses on those at elevated risk for developing problems. In the dissonance-based program, adolescent girls and young women with body image concerns who have internalized the thin-ideal voluntarily engage in verbal, written, and behavioral exercises in which they critique this ideal. These exercises theoretically makes them experience cognitive dissonance about pursuing the thin-ideal, which motivates the young women to reduce their thin-ideal internalization, leading to a decrease in body dissatisfaction, negative affect, ineffective dieting, and eating disorder symptoms.

Efficacy trials show that the dissonance prevention program produces greater reductions in eating disorder risk factors, eating disorder symptoms, functional impairment, mental health service utilization, and future onset of threshold/subthreshold eating disorders relative to assessment-only and alternative-intervention conditions with some effects persisting over 3-year follow-up (e.g., Stice et al., 2000; Stice, Shaw, Burton, & Wade, 2006; Stice, Marti, Spoor, Presnell, & Shaw, 2008b). Efficacy trials conducted in independent labs have found that dissonance-based prevention programs produce greater reductions in eating disorder risk factors and symptoms relative to an assessment-only control condition (Mitchell, Mazzeo, Rausch, & Cooke, 2007) and an alternative intervention (Becker, Smith, & Ciao, 2006). Consistent with the intervention theory for the dissonance-based eating disorder prevention program, there is evidence that reductions in thin-ideal internalization mediate the effects of the intervention on change in outcomes (Seidel, Presnell, & Rosenfield, 2009; Stice, Presnell, Gau, & Shaw, 2007). In support of the thesis that dissonance induction contributes to intervention effects, participants assigned to high dissonance-induction versions of this intervention later reported lower eating disorder symptoms than those assigned to low dissonance-induction versions of this intervention (Green, Scott, Diyankova, Gasser, & Pederson, 2005; McMillan, Stice, & Rohde, 2011). Effectiveness trials in which high school and college clinicians recruited young women with body image concerns and delivered the intervention under ecologically valid conditions have also provided support for this prevention program, including significant reductions in eating disorder symptoms throughout 3-year follow-up (Stice, Rohde, Gau, & Shaw, 2009; Stice, Rohde, Shaw, & Gau, 2011).

Although these trials support the efficacy and effectiveness of this prevention program, it is important to investigate moderators of the effects of prevention programs. Identifying subgroups that show larger intervention effects would allow prevention scientists to target individuals most likely to benefit from this prevention program. Identifying subgroups that show weaker intervention effects would allow prevention scientists to exclude those unlikely to benefit from the intervention and might inform the design of more effective prevention programs for these subgroups.

One past report investigated moderators of intervention effects on change in the continuous measures of eating disorder risk factors and symptoms (Stice, Marti, Shaw, & O’Neil, 2008a); the dissonance intervention produced significantly stronger reductions in outcomes for individuals with the greatest initial thin-ideal internalization, body dissatisfaction, and elevated eating disorder symptoms. Theoretically, young women who report the strongest subscription to the thin-ideal experience the greatest cognitive dissonance from participating in this intervention, which should produce stronger reductions in thin-ideal internalization, body dissatisfaction, and eating disorder symptoms. Young women with the greatest body dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptoms are putatively more likely to actively participate in the intervention because they are more motivated, which may contribute to the larger intervention effects. The larger effects for those with initially higher body dissatisfaction and eating disorder symptoms may also have been partially driven by the fact that these individuals had more room for reduction in outcomes. Echoing these findings, intervention effects for a computer-based eating disorder prevention program were significantly stronger for individuals at highest risk for eating disorders because of elevated weight concerns (Celio et al., 2000). Our previous report that investigated moderators was conducted with data from a single trial, which limited the sensitivity to identifying moderators that affected a small portion of the sample, such as those with eating disorders at baseline. To increase sensitivity for detecting moderators, we combined data from three large trials, one efficacy trial and two large effectiveness trials (Stice et al., 2006; Stice, Rohde, Shaw, & Gau, 2009; Stice, Rohde, Durant, & Shaw, 2012). Our combined sample includes data from 977 participants from 12 high schools and 8 universities in 3 geographical regions. We focused on moderators of effects from pretest to posttest because this is typically when the intervention effects are largest, which should also increase sensitivity to detecting moderators.

We tested the hypotheses that the dissonance intervention would produce greater reductions in outcomes for individuals with high versus low thin-ideal internalization and body dissatisfaction at baseline. The larger sample size also permitted a test of whether the dissonance intervention produced stronger reductions in outcomes for those who met criteria for the new DSM-5 eating disorders at baseline relative to those free of these eating disorders, which follows from earlier evidence that the intervention produced larger effects for those with initial elevations in eating disorder symptoms. We thought it particularly important to expressly test whether this intervention produces stronger effects for individual with versus without a DSM-5 eating disorder because if the effects were stronger for the former group, it would suggest that it might be useful to offer this prevention program in an indicated fashion to groups of individuals with eating disorders, rather than only populations at risk for future eating disorders. Consistent with this idea, a recent trial found that a cognitive behavioral body satisfaction intervention produced large reductions in eating disorder risk factors and symptoms for individuals with subthreshold eating disorders (Jacobi, Völker, Trockel, & Taylor, 2012). Finally, a meta-analytic review found that eating disorder prevention programs tend to produce smaller intervention effects for adolescents under the age of 15 versus older women (Stice, Shaw, & Marti, 2007). Older adolescents may have struggled with body image concerns more intensively and for a longer duration, which might make them engage more effectively in eating disorder prevention programs. Further, younger adolescents may not have adequate abstract reasoning skills to appreciate the concept of the thin-ideal. Thus, we tested the hypothesis that the dissonance intervention would produce significantly larger reductions in outcomes for older versus younger participants.

Method

Participants and Procedure

For this report, we combined data from an efficacy trial involving roughly equivalent numbers of high school and college students (trial 1; Stice et al., 2008b), an effectiveness trial involving high school students (trial 2; Stice, Rohde, Gau, & Shaw, 2009), and an effectiveness trial involving college students (trial 3; Stice et al., 2012). In total, 977 female participants were randomized to either the dissonance intervention or an assessment-only control condition (M age = 18.6, SD = 4.6; M BMI = 24.3; range = 13-48; SD = 5.2). The combined sample included 5.9% Asian/Pacific Islander, 4.3% African American, 9.9% Hispanic, 0.6% Native American, 73.8% Caucasian, and 5.6% who specified other or mixed racial heritage. Parental education, a proxy for socioeconomic status, was 12.3% high school graduate or less, 18.9% some college, 36.1% college graduate, and 32.7% advanced graduate/professional degree.

Participants were recruited using direct mailings, flyers, and leaflets inviting young women with body image concerns to participate in a study evaluating body acceptance interventions at the various schools. Assessors obtained written consent from all participants (and their parents if they were minors) before data collection. Participants had to verbally affirm that they had body image concerns during a phone screen. We attempted to exclude students who met full threshold criteria for Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th ed.; DSM–IV; American Psychiatric Association, 1994) anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, or binge eating disorder, but numerous individuals met criteria for the newly proposed DSM-5 threshold and subthreshold eating disorders at baseline.

For this report, we only included participants assigned to the dissonance intervention or assessment-only control condition from trial 1. Participants from the trials 2 and 3 were randomly assigned to the dissonance intervention or assessment-only control conditions (in which educational brochures about body image and eating disorders were distributed). In trial 1 we delivered a 3 1-hr session version of the dissonance intervention, whereas in trials 2 and 3 we delivered a 4 1-hr session version of the intervention, which contained virtually identical content. Groups contained 5 – 10 participants. A scripted intervention manual was used for standardization purposes. The intervention was delivered by a graduate research assistant and an undergraduate co-facilitator in trial 1 and by school counselors or nurses in trials 2 and 3. Facilitator training involved reading the facilitators guide and intervention script, observing delivery of the sessions or session components, and then supervised delivery of the sessions under the guidance of Dr. Stice. In trials 2 and 3, all sessions were recorded and reviewed by the investigators for fidelity of intervention delivery and supervision. Greater details regarding fidelity and competence ratings are reported elsewhere (Stice et al., 2006; Stice, et al., 2009).

Dissonance Intervention

Participants voluntarily engaged in verbal, written, and behavioral exercises in which they critiqued the thin-ideal. These exercises were conducted in group sessions and homework exercises. For example, participants engage in counter-attitudinal role-plays in which participants attempted to dissuade facilitators from pursuing the thin-ideal and wrote a letter to a hypothetical teenage girl telling her about the costs associated with the pursuit of the thin-ideal. The intervention content is presented in detail elsewhere (Stice et al., 2008; 2009).

Assessment-Only Control Condition

Participants in trial 1 were given a referral list. Those who met criteria for an eating disorder at any follow-up were encouraged to seek treatment (as were participants in all conditions in all trials). Participants in trials 2 and 3 received a 2-page brochure produced by the National Eating Disorders Association in 2002 about body image and eating disorders, offering recommendations to improve body image.

We used the survey and blinded interview data participants provided at pretest and posttest for this report. Assessors had to demonstrate high inter-rater agreement (κ > .80) with expert raters using a dozen recorded training interviews conducted with individuals with or without eating disorders before collecting data. They also had to demonstrate inter-rater κ values of .80 or higher for a randomly selected 5% of the interviews and maintain high test-retest agreement (κ > .80 or greater) for 5% of randomly selected interviews that were re-conducted by the same assessor. Participants were paid for completing assessments. The respective local institutional review boards in Texas, Pennsylvania and Oregon approved this project.

Measures

Thin-ideal internalization

Thin-ideal internalization was assessed with the Ideal-Body Stereotype Scale-Revised (Stice et al., 2006). This scale has shown internal consistency (α = .91), test-retest reliability (r = .80), and predictive validity for bulimic symptom onset (Stice et al., 2006).

Body dissatisfaction

Items from the Satisfaction and Dissatisfaction with Body Parts Scale (Berscheid, Walster, & Bohrnstedt, 1973) assessed satisfaction with nine body parts that are often of concern to females (e.g., stomach, thighs, and hips). This scale has shown internal consistency (α = .94), 3-week test-retest reliability (r = .90), and predictive validity for bulimic symptom onset (Stice et al., 2006).

Eating pathology

The semistructured Eating Disorder Diagnostic Interview assessed DSM–IV eating disorder symptoms. Items assessing symptoms in the past month were summed to create an overall eating disorder symptom composite, which served as a key outcome. A square root transformation was used to normalize this composite. The symptom composite showed internal consistency (α = .92), 1-week test–retest reliability (r = .90), sensitivity to detecting effects from eating disorder prevention and treatment interventions, and predictive validity for future onset of depression in past studies of adolescent girls and young women (Burton & Stice, 2006; Stice et al., 2009). We also determined whether or not participants met criteria of a DSM-5 eating disorder at pretest, which included anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, purging disorder, atypical anorexia nervosa, subthreshold bulimia nervosa, and subthreshold binge eating disorder (Stice et al., in press presents details about how each was operationalized). Test-retest reliability was assessed by randomly selecting a subset of 184 participants who were interviewed by the assessors and then re-interviewed by the same assessor within a week from these studies and one other (Stice et al., in press); the test-retest reliability was κ = .79 for DSM-5 eating disorders. Inter-rater agreement for the eating disorder diagnoses was assessed by randomly selecting subset of 207 participants who were re-interviewed by a second blinded assessor for these studies and one other (Stice et al., in press); the inter-rater agreement was κ = .75 for DSM-5 eating disorders.

Results

Participants in the two groups were compared on all baseline measures. Table 1 provides means and standard deviations for the three outcomes at pretest and posttest for both conditions. Groups did not significantly differ with regard to baseline study outcomes with the exception that participants in the dissonance condition had significantly higher eating disorder symptom scores than those in the control condition (t = 3.00, (975), p = .003). However, because this effect accounted for less than 1% of the variance in symptoms, suggesting this effect was primarily due to the fact that with an N = 977, we had power to detect trivial differences between groups. Nonetheless, all models controlled for baseline eating disorder symptoms. Fifty participants (5.1%) were diagnosed with a DSM-5 threshold eating disorder and baseline and another 38 (3.9%) were diagnosed with a DSM-5 Feeding and Eating Disorder Not Elsewhere Classified. Separate models were estimated for each combination of moderators and the contrast of dissonance intervention versus the control condition. Analysis was performed using SPSS and R. The outcome variables thin-ideal internalization, body dissatisfaction, and eating disorder symptoms were assessed at pretest and posttest. The continuous variables were centered, following Aiken and West (1991). Each model contained the baseline measure of the outcome variable, a dummy variable for the dissonance versus the control condition, two dummy variables to control for trial, two dummy variables to control for state, and the moderator. We tested whether all possible 2-way interactions predicted posttest outcome scores controlling for the baseline version of the outcome. Two-way interactions were constructed by multiplying condition (dummy coded) by each moderator. Table 2 provides the results of all 12 interactions tested.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Pretest | Posttest | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||

| Variable | M | SD | M | SD |

| Thin-ideal internalization | ||||

| Dissonance | 3.67 | 0.56 | 3.35 | 0.70 |

| Control | 3.67 | 0.50 | 3.57 | 0.55 |

| Body dissatisfaction | ||||

| Dissonance | 3.44 | 0.74 | 3.04 | 0.85 |

| Control | 3.29 | 0.74 | 3.21 | 0.79 |

| Eating disorder symptoms a | ||||

| Dissonance | 13.71 | 13.63 | 7.77 | 9.38 |

| Control | 11.31 | 11.28 | 9.02 | 10.07 |

Note.

Tabled means and standard deviations are nontransformed symptom counts.

Table 2.

Interaction effects for the different outcomes

| Interaction | β - Coefficient | t- value |

|---|---|---|

| Thin-ideal internalization × condition | ||

| Thin-ideal internalization | −0.07 | −2.10 |

| Body dissatisfaction | −0.06 | −1.80* |

| Eating disorder symptoms | −0.11 | −2.11** |

| Body dissatisfaction × condition | ||

| Thin-ideal internalization | 0.25 | 0.76 |

| Body dissatisfaction | −0.02 | −0.68 |

| Eating disorder symptoms | −0.07 | −1.93 |

| Eating disorder at baseline × condition | ||

| Thin-ideal internalization | −0.02 | −0.43 |

| Body dissatisfaction | 0.06 | 1.50 |

| Eating disorder symptoms | −0.11 | −2.90** |

| Age × condition | ||

| Thin-ideal internalization | −0.04 | −1.23 |

| Body dissatisfaction | −0.07 | −2.12* |

| Eating disorder symptoms | 0.00 | 0.06 |

Note.

p < .01.

p < .05

Moderating Effects of Baseline Thin-ideal internalization

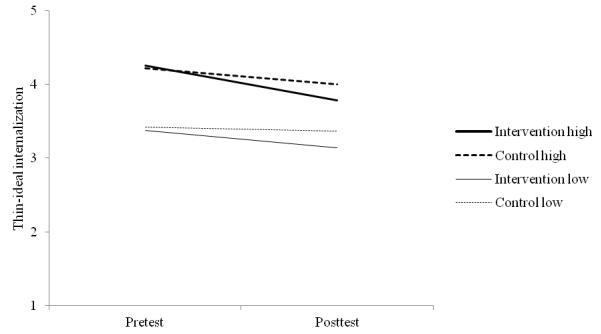

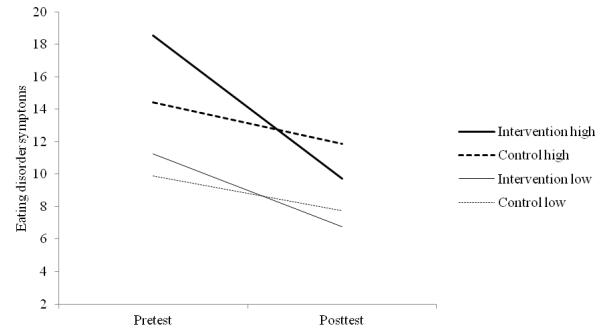

A significant interaction revealed that the effect of the dissonance prevention program on thin-ideal internalization reduction was significantly stronger for participants with higher versus lower initial thin-ideal internalization scores (t = −2.109, (960), p = .044, d = .10). Baseline thin-ideal internalization did not significantly moderate intervention effects on change in body dissatisfaction. Another significant interaction revealed that the intervention effect on eating disorder symptom reduction was significantly stronger for participants with higher versus lower initial thin-ideal internalization scores (t = −2.928, (968), p = .003, d = .14). Figures 1 a, and b provide the mean outcomes for the dissonance intervention versus control condition at pretest and posttest for individuals with low versus high baseline thin-ideal internalization.

Figure 1a.

Change in thin-ideal internalization for participants with high and low thin-ideal internalization

Figure 1b.

Change in eating disorder symptoms for people with high and low thin-ideal internalization at pretest

Moderating Effects of Baseline Body dissatisfaction

Baseline body dissatisfaction did not significantly moderate the intervention effets on thin-ideal internalization and body dissatisfaction reductions. However, a marginal interaction suggested that the intervention produced larger eating disorder symptom reduction for those with higher versus lower baseline body dissatisfaction scores (t = −1.932, (969), p = .054, d = .09).

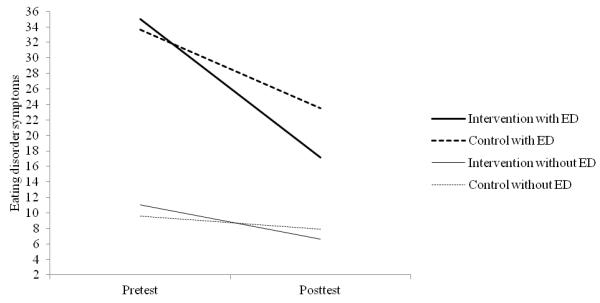

Moderating Effects of Baseline DSM-5 Eating Disorder Diagnoses

Baseline eating disorder diagnoses did not moderate the intervention effects on thin-ideal internalization or body dissatisfaction reduction. However, a significant interaction revealed that the intervention effect of eating disorder symptoms was significantly larger for those with versus without a baseline eating disorder diagnosis (two-way interaction: t = −2.856, (970), p = .004, d = .14). Figure 2 provides the mean eating disorder symptom scores at pretest and posttest for individuals with an eating disorder versus no eating disorder at baseline.

Figure 2.

Change in eating disorder symptoms for participants with and without cating disorder at pretest

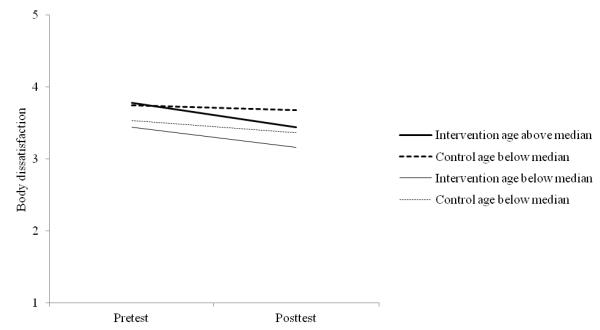

Moderating Effects of Participant’s Age

Age at baseline did not significantly moderate the intervention effects on thin-ideal-internalization or eating disorder symptom reduction. However, a significant interaction indicated that the intervention effects on body dissatisfaction were significantly stronger for older versus young participants (t = −2.118, (954), p = .034, d = .10). Figure 3 provides the mean body dissatisfaction scores at pretest and posttest for those older versus younger participants.

Figure 3.

Change in body dissatisfaction for participants with age above and below the median

Discussion

Results indicated that the effects of the dissonance prevention program on eating disorder symptoms and thin-ideal internalization were significantly stronger for participants who reported initial elevations in thin-ideal internalization. These findings converge with evidence the intervention effects were larger for this population in the high-school/college efficacy trial (Stice et al., 2008a). Results align with the intervention theory for this prevention program in that young women with the greatest initial internalization of the thin-ideal would be expected to experience more dissonance from critiquing the thin-ideal in the sessions and home exercises, which putatively generates the stronger reductions in the outcomes.

Second, results indicated that the dissonance prevention program produced stronger reductions in eating disorder symptoms for those with versus without a DSM-V eating disorder at baseline. This effect may have emerged because these individuals were more likely to engage in the intervention or simply because they had more room for a reduction in symptoms than participants free of an eating disorder. It is also possible that those young women with eating disorders experienced greater dissonance regarding pursuit of the thin-ideal, which may have contributed to the stronger intervention effects. This finding dovetails with evidence that this prevention program produced larger effects for those with initial elevations in eating disorder symptoms in the high school/college efficacy trial (Stice et al., 2008a). It also aligns with evidence that a cognitive behavioral body satisfaction intervention produced strong effects (mean d = .43) for individuals who reported initial elevated eating disorder symptoms at baseline than have been observed in earlier evaluations of this intervention (Jacobi et al., 2012).

Third, there was evidence of an intervention effect on body dissatisfaction for participants of older age at baseline, extending findings from a meta analyses that indicated that found that prevention programs on average produce larger effects for older adolescents and young adults versus middle adolescents (Stice et al., 2007). Maggs and colleagues (1996) found that prevention programs are typically more effective when delivered during the developmental period when the disorder emerges. Eating disorders usually do not emerge until late adolescence (Stice et al., in press), which may explain why this prevention program produced weaker effects for younger adolescents. Moreover, older adolescents might be better able to grasp the abstract concept of the societally promoted thin-ideal.

There was limited evidence that elevated body dissatisfaction amplified intervention effects, as was observed in the analyses of moderators of the effects from the high school/collage efficacy trial (Stice et al., 2008a); one of the interactions involving this moderator was a marginal trend. This pattern of findings suggests that this is not a particularly robust moderator. It is also possible that there was a restriction in range for body dissatisfaction because an inclusion criterion for the trials was body image concerns, but the fact that the standard deviations were smaller for thin-ideal internalization, which showed stronger moderating effects, suggests that a restriction in range probably did not explain the weak moderating effects for body dissatisfaction.

It is important to consider the possibility that these findings are due to chance. We did not correct for multiple testing because one would expect less than one chance finding given that we only tested 12 interactions. The fact that 33% of the effects were significant and the fact that findings replicate results from an early report examining moderators of intervention effects suggests that the findings are not false positive findings. Nonetheless, for readers who wish to apply a Bonferroni correction, only the two interactions with p-values that are less than .0042 would be considered significant (the moderating effect of thin-ideal internalization on change in eating disorder symptoms and the moderating effect of eating disorder diagnoses on change in eating disorder symptoms).

It is also important to acknowledge that the interactive effects reported herein are small in magnitude. This pattern of findings suggests that the dissonance eating disorder prevention programs is effective for a broad range of individuals, but is somewhat more effective for the subgroups identified in the moderation analyses.

Limitations

It is important to consider the limitations of the current study. First, we relied on self-report data from interviews and surveys, which introduces the possibility of reporter bias that might have distorted our estimates of intervention effects. Yet, shared method bias would have been manifest in main effects, rather than interactive effects. Second, we conjectured that participants who reported initial elevations in thin-ideal internalization might experience greater dissonance induction from the session exercises. However, we did not include a direct measure of dissonance, as it is usually inferred from attitudinal change in research studies. Finally, because the data set was merged from three separate trials, it is possible that the slightly different approaches to recruitment and intervention content introduced noise into the data set, even though we controlled for trial, which might have attenuated the magnitude of effects.

Implications for Prevention and Future Research

The fact that the moderating effects were relatively small suggests that the dissonance prevention program produces beneficial effects for a wide range of individuals, implying that it would be useful to disseminate this prevention program broadly. However, the moderating effects do indicate that if this prevention program can only be offered to a small subset of individuals, it might be prudent to focus on those with body image concerns that are paired with elevated thin-ideal internalization and/or DSM-5 eating disorders. Indeed, results suggest it would be worth testing whether offering this intervention to individuals with DSM-5 eating disorders (indicated prevention) in a randomized trial. Results may also imply that it might be valuable to test whether offering the dissonance intervention in treatment setting produces reductions in symptoms, as well as pursuit of the thin-ideal, which is often a residual symptom in those treated for eating disorders. Last, results suggest that the dissonance prevention program has greater effects for older adolescents and young adults, which suggests that it might be best to target this age period with the existing dissonance prevention program and to develop a version of this program that is adapted for younger adolescents. It is our hope that the knowledge reported herein will help clinicians deliver this evidence-based prevention program to those most likely to show the greatest benefit and to inform the design of prevention programs that are effective for those who show less benefits from extant dissonance-based eating disorder prevention programs.

Highlights.

- The Body Project produced larger effects for youth with elevated thin-ideal internalization at baseline.

- The Body Project produced larger effects for youth with threshold/subthreshold eating disorders at baseline.

- The Body Project also produced larger effects for older adolescents than for younger adolescents.

- The Body Project is effective for a wide range of persons, but somewhat more effective for the subgroups identified herein.

Acknowledgments

** This study was supported by Grants MH/DK061957, MH070699, and MH086582 from the National Institutes of Health.

*** We thank project research assistants Heather Amrhein, Cara Bohon, Emily Burton, Jessica Finley, Cassie Goodin, Krisa Heim, Erica Marchand, Natalie McKee, Janet Ng, Julie Pope, Kathryn Presnell, Emily Wade, and Julie Walker.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Aiken LS, West SG. Multiple Regression: Testing and interpreting interactions. Sage; Newbury Park, CA: 1991. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association . Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. 4th ed Author; Washington, DC: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association [Retrieved July 20th 2012];DSM-V Development. (n.d.) from www.dsm5.org/Pages/Default.aspx.

- Becker CB, Smith LM, Ciao AC. Peer facilitated eating disorders prevention: A randomized effectiveness trial of cognitive dissonance and media advocacy. Journal of Counseling Psychology. 2006;53:550–555. [Google Scholar]

- Berscheid E, Walster E, Bohrnstedt G. The happy American body: A survey report. Psychology Today. 1973;7:119–131. [Google Scholar]

- Burton E, Stice E. Evaluation of a healthy-weight treatment program for bulimia nervosa: A preliminary randomized trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2006;44:1727–1738. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2005.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Celio A, Winzelberg A, Wilfley D, Eppstein-Herald D, Springer E, Dev P, et al. Reducing risk factors for eating disorders: Comparison of an Internet- and a classroom-delivered psychoeducational program. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2000;68:650–657. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn CG, Bohn K. Eating disorder NOS (EDNOS): an example of the troublesome “not otherwise specified” (NOS) category in DSM-IV. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2005;43:691–701. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2004.06.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green M, Scott N, Diyankova I, Gasser C, Pederson E. Eating disorder prevention: An experimental comparison of high level dissonance, low level dissonance, and no-treatment control. Eating Disorders: The Journal of Treatment & Prevention. 2005;13:157–169. doi: 10.1080/10640260590918955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobi C, Völker U, Trockel MT, Taylor CB. Effects of an Internet-based intervention for subthreshold eating disorders: A randomized controlled trial. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2012;50:93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2011.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JG, Cohen P, Kasen S, Brook JS. Eating disorders during adolescence and the risk for physical and mental disorders during early adulthood. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2002;59:545–552. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.6.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggs JL, Schulenberg J, Hurrelmann K. Developmental transitions during adolescence: Health promotion implications. In: Schulenberg J, Maggs J, Hurrelmann K, editors. Health risks and developmental transitions during adolescence. Cambridge University Press; New York: 1996. pp. 522–543. [Google Scholar]

- McMillan W, Stice E, Rohde P. High- and low-level dissonance-based eating disorder prevention programs with young women with body image concerns: An experimental trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:129–134. doi: 10.1037/a0022143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell KS, Mazzeo SE, Rausch SM, Cooke KL. Innovative interventions for disordered eating: Evaluating dissonance-based and yoga interventions. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2007;40:120–128. doi: 10.1002/eat.20282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seidel A, Presnell K, Rosenfield D. Mediators in the dissonance eating disorder prevention program. Behaviour Research and Therapy. 2009;47:645–653. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2009.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Marti N, Rohde P. Prevalence, incidence, impairment, and course of the proposed DSM-5 eating disorder diagnoses in an 8-year prospective community study of young women. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. doi: 10.1037/a0030679. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Marti CN, Shaw H, O’Neil K. General and program-specific moderators of two eating disorder prevention programs. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2008a;41:611–617. doi: 10.1002/eat.20524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Marti N, Spoor S, Presnell K, Shaw H. Dissonance and healthy weight eating disorder prevention programs: Long-term effects from a randomized efficacy trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2008b;76:329–340. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.76.2.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Mazotti L, Weibel D, Agras WS. Dissonance prevention program decreases thin-ideal internalization, body dissatisfaction, dieting, negative affect, and bulimic symptoms: A preliminary experiment. International Journal of Eating Disorders. 2000;27:206–217. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-108x(200003)27:2<206::aid-eat9>3.0.co;2-d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Presnell K, Gau J, Shaw H. Testing mediators of intervention effects in randomized controlled trials: An evaluation of two eating disorder prevention programs. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2007;75:20–32. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.75.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Rohde P, Durant S, Shaw H. A preliminary trial of a prototype Internet dissonance-based eating disorder prevention program for young women with body image concerns. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:907–916. doi: 10.1037/a0028016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Rohde P, Gau J, Shaw H. An effectiveness trial of a dissonance-based eating disorder prevention program for high-risk adolescent girls. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2009;77:825–834. doi: 10.1037/a0016132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Rohde P, Shaw H, Gau J. An effectiveness trial of a selected dissonance-based eating disorder prevention program for female high school students: Long-term effects. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2011;79:500–508. doi: 10.1037/a0024351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Shaw H, Burton E, Wade E. Dissonance and healthy weight eating disorder prevention programs: A randomized efficacy trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:263–275. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stice E, Shaw H, Marti CN. A meta-analytic review of eating disorder prevention programs: Encouraging findings. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology. 2007;3:233–257. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson GT, Becker CB, Heffernan K. Eating disorders. In: Mash EJ, Barkley RA, editors. Child psychopathology. 2nd ed Guilford Press; New York: 2003. pp. 687–715. [Google Scholar]