Abstract

Objectives

To investigate the risk factors and prognosis associated with acute exacerbation (AE) in patients with rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD).

Design

A retrospective case–control study.

Setting

A single academic hospital.

Participants

51 consecutive patients diagnosed with RA-ILD between 1995 and 2012. All patients fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of the American College of Rheumatology for RA. ILD was diagnosed on the basis of clinical presentation, pulmonary function tests, high-resolution CT (HRCT) findings and lung biopsy findings.

Main outcome measures

Overall survival and cumulative AE incidence were analysed using Kaplan-Meier method. Cox hazards analysis was used to determine significant variables associated with AE occurrence and survival status.

Results

A total of 11 patients (22%) developed AE, with an overall 1-year incidence of 2.8%. Univariate analysis revealed that older age at ILD diagnosis (HR 1.11; 95% CI 1.02 to 1.21; p=0.01), usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) pattern on HRCT (HR 1.95; 95% CI 1.07 to 3.63; p=0.03) and methotrexate usage (HR 3.04; 95% CI 1.62 to 6.02; p=0.001) were associated with AE. Of 11 patients who developed AE during observation period, 7 (64%) died of initial AE. In survival, AE was a prognostic factor for poor outcome (HR 2.47; 95% CI 1.39 to 4.56; p=0.003).

Conclusions

In patients with RA-ILD, older age at ILD diagnosis, UIP pattern on HRCT and methotrexate usage are associated with the development of AE. Furthermore, AE has a serious impact on their survival.

Keywords: Rheumatology

Article summary.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Acute exacerbation has a serious impact on the survival of patients with rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease.

Given its retrospective study design, it is subject to several possible biases. Therefore, prospective studies are necessary to confirm our results.

Introduction

Acute exacerbation (AE) is a recently established and an increasingly recognised occurrence in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF).1 AE is characterised by acute deterioration in respiratory status, with newly developed bilateral ground-glass opacities and/or consolidations on chest radiographs or CT scans. It should be in the absence of other alternative causes such as infection, left heart failure, pulmonary embolism or an identifiable cause of lung injury. AE reportedly occurs not only in patients with IPF but also in patients with other interstitial lung diseases (ILDs), including idiopathic non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP), collagen vascular disease-associated ILDs (CVD-ILDs) and other forms of ILD.2–4 The in-hospital mortality associated with AE in patients with CVD-ILD was demonstrated to be as high as that in patients with IPF,1–4 suggesting that AE may be associated with poor prognosis in patients with CVD-ILD.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, systemic, autoimmune disorder of unknown aetiology that primarily involves joints.5 ILD is one of the common extra-articular manifestations.6 7 The reported prevalence is variable (1–58%) and depends on the detection and diagnostic method, or the selected population.8–13 We and Park et al4 previously reported that RA-associated ILD (RA-ILD) was the most common CVD-ILD associated with AE.3 However, the risk factors and prognosis associated with AE in patients with RA-ILD are not clarified.

In the current study, we attempted to elucidate the cumulative incidence of AE, its risk factors and prognostic factors in patients with RA-ILD.

Materials and methods

Subjects

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Hamamatsu University School of Medicine (approval number 24–191). Patient approval or informed consent was waived because the study involved a retrospective review of patient records and images. We retrospectively reviewed 51 consecutive patients diagnosed with RA-ILD between 1995 and 2012 at Hamamatsu University Hospital in Japan. All patients fulfilled the diagnostic criteria of the American College of Rheumatology for RA.14 Patients with other coexisting CVD were excluded. In addition, because our aim was to investigate the features of AE among patients with a chronic course of RA-ILD, patients with no evidence of chronic ILD were also excluded. Chronic ILD was defined as the ILD which had been stable for over 3 months.

ILD was diagnosed on the basis of clinical presentation, pulmonary function tests, high-resolution CT (HRCT) findings and lung biopsy findings. HRCT findings, such as bilateral areas with ground-glass attenuation, reticular opacities and honeycomb patterns, were interpreted and defined as ILD by a consensus between radiologists and pulmonologists. All cases underwent transbronchial lung biopsy and bronchoalveolar lavage, and 21 (41%) cases underwent surgical lung biopsy (SLB) to definitively diagnose ILD or rule out other diseases. The patients with environmental exposures, suspected of drug-induced pneumonia (ILD developed within 1 year after initiation of new drug) or with other known causes of ILD were excluded after considering exposure history and the findings of appropriate tests and histopathological examinations.

Acute exacerbation

AE was defined using recently proposed criteria1 that were slightly modified for adaptation to RA-ILD: previous diagnosis of RA-ILD; unexplained worsening or development of dyspnoea within 30 days of onset; new bilateral ground-glass abnormalities and/or consolidation superimposed on a reticular or honeycomb pattern on HRCT; no evidence of pulmonary infection on negative respiratory culture, including endotracheal aspirate or bronchoalveolar lavage and serological test results for respiratory pathogens; exclusion of alternative causes such as left heart failure, pulmonary embolism or an identifiable cause of lung injury. Patients with AE were required to meet all five criteria. In our institution, cultures of sputum, blood, urine and bronchoalveolar lavage fluid, and serological tests examined for mycobacteria, fungi, bacteria and some viruses were routinely performed. Echocardiography and, if necessary, CT scanning with intravenous contrast were performed to rule out left heart failure or pulmonary thromboembolism. The patients who developed acute pneumonitis within 1 year after initiation of drug for RA were excluded because drug-induced pneumonitis was not completely ruled out. Patients who did or did not develop AE during the observation period were classified into the AE and non-AE groups, respectively.

Data collection

All clinical and laboratory data were collected from medical records. The observation period was calculated from the date of diagnosis of RA-ILD to the last visit. The AE-free period was defined as the time elapsed between the date of RA-ILD diagnosis and the first AE occurrence (AE group) or the last visit (non-AE group).

Review of radiographic findings

HRCT images taken at the time of RA-ILD diagnosis were reviewed. These images comprised 1–2.5 mm collimation sections at 10 mm intervals. They were reconstructed by a high spatial frequency algorithm, and were displayed at window settings appropriate for viewing the lung parenchyma (window level, −600 to −800 Hounsfield units; window width, 1200–2000 Hounsfield units). HRCT images were randomised and reviewed independently by two expert chest radiologists (with 23 and 12 years of experience) who were unaware of the related clinical information. Interobserver agreement was classified as follows: poor (κ=0–0.20), fair (κ=0.21–0.40), moderate (κ=0.41–0.60), good (κ=0.61–0.80) and excellent (κ=0.81–1.00).

RA-ILD on HRCT was classified as a usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) pattern or a non-UIP pattern according to recent guideline with slight modification.15 Briefly, a UIP pattern on HRCT was characterised by the following: subpleural and basal predominance; reticular abnormalities; honeycombing with or without traction bronchiectasis and the absence of features listed as inconsistent with a UIP pattern; including upper or mid-lung predominance, peribronchovascular predominance, extensive ground-glass abnormalities, profuse micronodules, discrete cysts, diffuse mosaic attenuation/air-trapping and consolidation in bronchopulmonary segment(s)/lobe(s). If the HRCT pattern did not meet the criteria, it was interpreted as a non-UIP pattern. Disagreements regarding HRCT interpretation were resolved by a consensus between both radiologists.

Review of histopathological findings

SLB specimens were obtained from at least two sites. A diagnosis of RA-ILD was originally made in all cases on the basis of histological features evaluated by a lung pathologist at our hospital, correlated with the clinical and radiological findings. All SLB specimens were also reviewed by a second lung pathologist with 36 years of experience. The histological classification of interstitial pneumonia was based on the consensus statement criteria for idiopathic interstitial pneumonias,16 and histological patterns that could not be classified according to the criteria were categorised as unclassified interstitial pneumonia.

Statistical analysis

All values are expressed as median (range) or number (%). The Mann-Whitney U test was used for non-parametric comparisons involving continuous data, whereas Fisher's exact test was used for comparing categorical data. Interobserver agreement on HRCT pattern was analysed using the κ statistic test. Survival was evaluated using the Kaplan-Meier method and the log-rank test according to observation period. The cumulative AE incidence was obtained from a Kaplan-Meier survival curve by treating AE as the death variable according to AE-free period. The 1-year AE incidence was based on person-year method and calculated by dividing the number of patients who developed AE by the total of AE-free period (year) of all the patients. Cox hazards analysis was used to determine significant variables associated with survival and AE occurrence. In all analyses, p<0.05 was considered statistically significant. All data were analysed using commercially available software (JMP V.9.0.3a, SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina, USA).

Results

Patient characteristics

A total of 82 patients with RA-ILD were identified from medical records at Hamamatsu University Hospital. Of these, 11 patients with other coexisting CVDs, 8 with no evidence of chronic ILD and an initial acute/subacute course of ILD and 3 suspected of drug-induced pneumonitis were excluded. In addition, nine patients for whom no initial HRCT images were available for review were also excluded. The remaining 51 patients with RA-ILD were included in this study (table 1 and figure 1).

Table 1.

Clinical characteristics

| Characteristics | Total N=51 (100) | Non-AE group† N=40 (78) | AE group‡ N=11 (22) | p Value§ |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age, years (range) | ||||

| At RA diagnosis | 61 (28–82) | 60 (28–81) | 65 (42–82) | 0.15 |

| At ILD diagnosis | 62 (31–83) | 62 (31–83) | 69 (58–83) | 0.15 |

| At AE onset | 72 (60–86) | |||

| Sex male, n (%) | 29 (57) | 23 (58) | 6 (55) | 0.86 |

| Observation period, years (range) | 8.5 (1–17) | 9 (1–17) | 6.4 (2–14) | 0.45 |

| AE-free period, years (range) | 7 (1–17) | 9 (1–17) | 6 (2–14) | 0.19 |

| Smoking habit, n (%) | ||||

| Never | 20 (39) | 18 (45) | 2 (18) | 0.15 |

| Former | 24 (47) | 16 (40) | 8 (73) | |

| Current | 7 (14) | 6 (15) | 1 (9) | |

| RF, IU/mL (range)¶ | 197 (6–2666) | 189 (6–2666) | 205 (39–2530) | 0.47 |

| DAS28-CRP, score (range)¶ | 1.95 (1.02–5.13) | 2.53 (1.02–5.13) | 1.82 (1.47–2.3) | 0.62 |

| PaO2, torr (range) | 82.4 (67–109) | 81 (67–102) | 85.8 (74–109) | 0.19 |

| %FVC, % (range) | 91.1 (50.6–130) | 87.5 (51–130) | 95 (60–125) | 0.38 |

| HRCT pattern, n (%) | ||||

| UIP pattern | 14 (27) | 8 (20) | 6 (55) | 0.02* |

| Non-UIP pattern | 37 (73) | 32 (80) | 5 (45) | |

| Death during observation period, n (%) | ||||

| Caused by respiratory failure | 9 (18) | 2 (5) | 7 (64) | 0.02* |

| Caused by other diseases | 3 (6) | 3 (8) | 0 (0) | |

Data are presented as n (%), median (range).

When HRCT pattern was identified as a UIP pattern, the positive predictive value and negative predictive value for AE occurrence was 42.9% and 86.5%, respectively.

In the AE group, seven patients died of respiratory failure caused by AE. In the non-AE group, two died of respiratory failure caused by bacterial pneumonia or pneumocystis pneumonia, one of gastric bleeding and two of unknown causes.

*p < 0.05.

†Non-AE group, patients who did not develop AE during observation period.

‡AE group, patients who developed AE during observation period.

§Non-AE group versus AE group.

¶At the first AE occurrence (AE group) or the last visit (non-AE group).

AE, acute exacerbation; DAS28-CRP, disease activity score 28 C reactive protein; %FVC, predicted forced vital capacity; HRCT, high resolution CT; ILD, interstitial lung disease; PaO2, arterial oxygen pressure; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; RF, rheumatoid factor; UIP pattern, usual interstitial pneumonia pattern.

Figure 1.

Number of patients included in this study. Eighty-two patients with rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD) were assessed for eligibility. From these, 31 patients were excluded, and 51 patients with chronic course of RA-ILD were included. During observation period, 11 patients developed acute exacerbation.

The median age at the onset of RA and diagnosis of RA-ILD was 61 (range 28–82) years and 62 (range 31–83) years, respectively. The median observation period and AE-free period was 8.5 (range 1–17) years and 7 (range 1–17) years, respectively.

During the observation period, 11 patients (22%) developed AE. The median age at the onset of AE was 72 (range 60–86) years. There were no statistically significant differences in age at the onset of RA, age at diagnosis of RA-ILD, sex, observation period, AE-free period, smoking habits, predicted forced vital capacity at diagnosis of RA-ILD and arterial oxygen pressure at diagnosis of RA-ILD between the AE and non-AE groups. Also there were no statistically significant differences in articular disease activities (RF and disease activity score 28 C reactive protein (DAS28-CRP)) at the last visit (non-AE group) or the first AE occurrence (AE group).

In the AE group, 7 of 11 patients (64%) died of respiratory failure caused by initial AE during the observation period. In the non-AE group, 2 of 40 patients (5%) died of respiratory failure. Regarding death caused by respiratory failure, there was a statistically significant difference in the mortality rate between the AE and non-AE groups (p=0.02).

Extra-articular manifestations except for ILD had been observed in 8 (16%) of 51 patients (pericarditis in 2 patients, pleuritis in 1, neuropathy in 2, cutaneous vasculitis in 2, glomerulonephritis in 1, rheumatoid nodule in 2). There were three (27%) patients with extra-articular manifestations beyond ILD in AE group while five (13%) in non-AE group. No significant difference in the incidence was observed between AE group and non-AE group (p=0.26).

HRCT pattern

Of the 51 patients with RA-ILD, 14 (27%) exhibited the UIP pattern on HRCT. HRCT images of 8 of 40 patients (20%) in the non-AE group and 6 of 11 (55%) patients in the AE group demonstrated a UIP pattern. Interobserver agreement between both radiologists was moderate (κ statistic test, κ=0.44). The number of patients who exhibited a UIP pattern on HRCT was significantly higher in the AE group than in the non-AE group (table 1).

When HRCT pattern was identified as a UIP pattern, the positive predictive value and negative predictive value for AE occurrence was 42.9% and 86.5%, respectively.

Diagnostic accuracy of HRCT pattern for histopathological pattern

Among the 51 patients, 21 (41%) underwent SLB. Histopathological analysis revealed UIP in 12 patients, NSIP in 7, desquamative interstitial pneumonia in 1 and an unclassified interstitial pneumonia in 1. The diagnostic accuracy of HRCT pattern for histopathological pattern was evaluated in 21 histopathologically confirmed patients. The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value of HRCT for histopathological evidence of UIP is 41.7%, 100%, 100% and 56.3%, respectively (table 2).

Table 2.

Diagnostic accuracy of HRCT pattern for histopathological pattern in 21 histopathologically confirmed patients

| Histopathological pattern |

Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| UIP | Other pattern | ||

| UIP pattern on HRCT | 5 | 0 | 5 |

| Non-UIP pattern on HRCT | 7 | 9 | 16 |

| Total | 12 | 9 | 21 |

Data are presented as number.

Other pattern means other histopathological pattern except for UIP including non-specific interstitial pneumonia, desquamative interstitial pneumonia and unclassifiable interstitial pneumonia.

The sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value and negative predictive value of HRCT for histopathological evidence of UIP is 41.7%, 100%, 100% and 56.3%, respectively.

HRCT, high resolution CT; UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia.

Treatment for RA

Of the 51 patients, 37 (73%) had received treatment for RA at their final visit (non-AE group) or at AE onset (AE group). Specifically, 29 patients (57%) had received corticosteroids, 17 (33%) received immunosuppressants except for methotrexate (MTX), 10 (20%) received MTX and 17 (33%) received other drugs. There were 6 (55%) patients who had received MTX in AE group while 4 (10%) patients in non-AE group and statistically significant difference was observed among the groups (p=0.001; table 3).

Table 3.

Treatment for RA at final visit† or AE onset‡

| Total N=51 | Non-AE group§ N=40 (78%) | AE group¶ N=11 (22%) | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Treatment, yes | 37 (73) | 27(68) | 10 (91) | 0.12 |

| Corticosteroid | 29 (57) | 22 (55) | 7 (64) | 0.61 |

| Immunosuppressant except for MTX | 17 (33) | 14 (35) | 3 (27) | 0.63 |

| MTX | 10 (20) | 4 (10) | 6 (55) | 0.001* |

| Other drugs | 17 (33) | 13 (33) | 4 (36) | 0.81 |

Data are presented as n (%) and compared between non-AE group and AE group using Fisher's exact test.

Immunosuppressant except for MTX included azathioprine (n=1), cycrophosphaminde (n=1), etanercept (n=2), mizoribine (n=7) and tacrolimus (n=6).

Other drugs included actarit (n=2), bucillamine (n=5), meloxicam (n=1) and salazosulfapyridine (n=11).

*p<0.05.

†In non-AE group.

‡In AE group.

§Non-AE group, patients who did not develop AE during the observation period.

¶AE group, patients who developed AE during observation period.

AE, acute exacerbation; ILD, interstitial lung disease; MTX, methotrexate; RA, rheumatoid arthritis.

None of the patients had received MTX earlier in the AE group, whereas two in non-AE group had received MTX during observation period but discontinued prior to final visit. Thus, there were 6 (55%) patients who had experienced MTX treatment during observation period in AE group and 6 (15%) patients in non-AE group. Median cumulative MTX dose were 1952 mg (384–3872) in six patients who had experienced MTX among AE group and 802 mg (32–2496) in six patients among non-AE group. No statistically significant difference was observed between two groups in cumulative MTX dose (p=0.20).

Articular disease activities (RF and DAS28-CRP) were compared between patients who had received MTX at the last visit or at the first AE occurrence, and those who had not. Median RF (range) were 112 (16–334) and 284 IU/mL (6–2666; p=0.25), median DAS28-CRP (range) were 1.94 (1.02–3.87) and 1.97 (1.02–5.13; p=0.78), respectively. There were no statistically significant differences in articular disease activities.

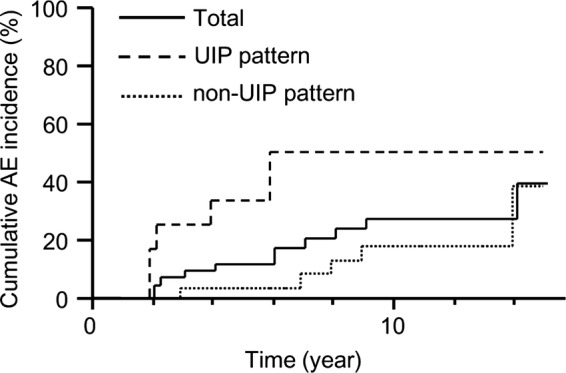

AE incidence

The cumulative AE incidence in patients with RA-ILD is shown in figure 2. The 5-year AE incidence was 11% (95% CI 2% to 21%) in all patients, 33% (95% CI 7% to 60%) in patients with a UIP pattern on HRCT (UIP pattern group) and 3% (95% CI 0% to 9%) in patients with a non-UIP pattern on HRCT (non-UIP pattern group). The AE incidence was significantly higher in UIP pattern group than in non-UIP pattern group (log-rank test, p=0.018). The overall 1-year AE incidence was 2.8%. The 1-year AE incidence was 6.5% in the UIP pattern group and 1.7% in the non-UIP pattern group.

Figure 2.

Cumulative acute exacerbation (AE) incidence in patients with rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Patients with usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) pattern on high resolution CT (HRCT) had a significantly higher incidence of AE compared with non-UIP pattern on HRCT (log-rank p=0.018).

Univariate analysis (table 4) revealed that older age at ILD diagnosis (HR 1.11; 95% CI 1.02 to 1.21; p=0.01), UIP pattern on HRCT (HR 1.95; 95% CI 1.07 to 3.63; p=0.03) and MTX usage (HR 3.04; 95% CI 1.62 to 6.02; p=0.001) were associated with the development of AE.

Table 4.

Risk factors for AE occurrence according to univariate cox hazard analysis

| HR | 95% CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at RA diagnosis | 1.03 | 0.97 to 1.10 | 0.35 |

| Age at ILD diagnosis | 1.11 | 1.02 to 1.21 | 0.01* |

| Sex, male | 0.90 | 0.49 to 1.69 | 0.73 |

| Smoking habit, yes | 1.60 | 0.81 to 4.10 | 0.19 |

| UIP pattern on HRCT, yes | 1.95 | 1.07 to 3.63 | 0.03* |

| PaO2 at ILD diagnosis | 1.05 | 0.98 to 1.12 | 0.14 |

| %FVC at ILD diagnosis | 1.02 | 0.99 to 1.06 | 0.24 |

| Treatment for RA at final visit† or AE onset‡ | |||

| Corticosteroids | 0.97 | 0.53 to 1.92 | 0.94 |

| Immunosuppressant except for MTX | 0.76 | 0.35 to 1.41 | 0.39 |

| MTX | 3.04 | 1.62 to 6.02 | 0.001* |

| Other drugs | 0.98 | 0.50 to 1.80 | 0.96 |

*p<0.05.

†In non-AE group.

‡In AE group.

AE, acute exacerbation; %FVC, predicted forced vital capacity; HRCT, high resolution CT; ILD, interstitial lung disease; MTX, methotrexate; PaO2, arterial oxygen pressure; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia.

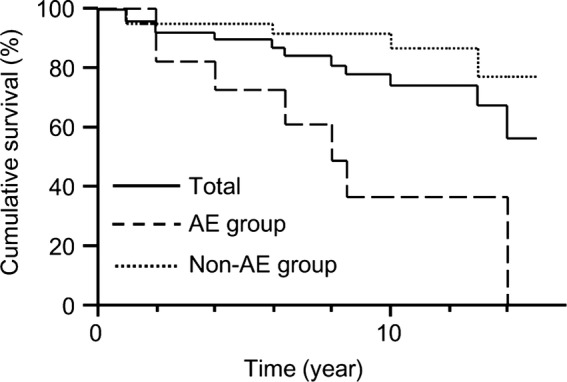

Survival

The overall survival of patients with RA-ILD and the survival according to HRCT pattern subgroup are as shown in figure 3. The 5-year survival was 90% (95% CI 81% to 98%) in all patients, 70% (95% CI 44% to 94%) in the UIP pattern group and 97% (95% CI 92% to 100%) in the non-UIP pattern group. Survival was significantly poorer in the UIP pattern group than in the non-UIP pattern group (log-rank test, p=0.04).

Figure 3.

Overall survival and the survival according to high-resolution CT (HRCT) pattern subgroup. Patients with usual interstitial pneumonia (UIP) pattern on HRCT had a significantly worse survival compared with those with non-UIP pattern on HRCT (log-rank p=0.04).

The survival statistics of AE group and non-AE group are shown in figure 4. Significantly worse survival was demonstrated in the AE group compared with the non-AE group (log-rank test, p=0.001).

Figure 4.

Survival of acute exacerbation (AE) group and non-AE group. Patients who developed AE during observation periods (AE group) had a significantly worse survival compared with those who did not (non-AE group; log-rank p=0.001).

Univariate analysis (table 5) revealed that older age at ILD diagnosis (HR 1.08; 95% CI 0.99 to 1.17; p=0.057) and UIP pattern on HRCT (HR 1.74; 95% CI 0.97 to 3.12; p=0.06) showed a trend towards poor outcome, while AE (HR 2.47; 95% CI 1.39 to 4.56; p=0.003) was significantly associated with poor survival.

Table 5.

Prognostic factors for survival, univariate cox hazard analysis

| HR | 95% CI | p Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age at RA diagnosis | 0.98 | 0.93 to 1.04 | 0.48 |

| Age at ILD diagnosis | 1.08 | 0.99 to 1.17 | 0.057 |

| Sex, male | 1.14 | 0.63 to 2.22 | 0.67 |

| Smoking habit, yes | 1.70 | 0.87 to 4.35 | 0.13 |

| UIP pattern on HRCT, yes | 1.74 | 0.97 to 3.12 | 0.06 |

| PaO2 at ILD diagnosis | 1.05 | 0.98 to 1.11 | 0.15 |

| %FVC at ILD diagnosis | 1.01 | 0.98 to 1.04 | 0.55 |

| AE during observation period, yes | 2.47 | 1.39 to 4.56 | 0.003* |

| Treatment for RA at final visit† or AE onset‡ | |||

| Corticosteroids | 1.23 | 0.67 to 2.65 | 0.52 |

| Immunosuppressant except for MTX | 0.69 | 0.32 to 1.27 | 0.25 |

| MTX | 1.44 | 0.67 to 2.68 | 0.31 |

| Other drugs | 0.76 | 0.36 to 1.41 | 0.40 |

*p < 0.05.

†In non-AE group.

‡In AE group.

AE, acute exacerbation; %FVC, predicted forced vital capacity; HRCT, high resolution CT; ILD, interstitial lung disease; MTX, methotrexate; PaO2, arterial oxygen pressure; RA, rheumatoid arthritis; UIP, usual interstitial pneumonia.

Discussion

To our knowledge, the current study is the first to focus on the risk factors and prognosis associated with AE in patients with RA-ILD. The overall 1-year AE incidence was 2.8% among the RA-ILD patients. Univariate analysis identified that a UIP pattern on HRCT, MTX usage and older age at ILD diagnosis were associated with the development of AE. Furthermore, AE was a prognostic factor for poor survival.

The 1-year AE incidence among patients with IPF has been reported to be 5–19%,17 18 whereas that among patients with other ILDs was 4.2% for idiopathic NSIP, 3.3% for CVD-ILD and 5.6% for CVD-UIP.4 In the current study, the 1-year AE incidence among patients with a UIP pattern on HRCT was 6.5% and cumulative incidence was significantly higher in UIP pattern group than in non-UIP pattern group. Therefore, a UIP pattern on HRCT was associated with the development of AE. In a previous report of small number of biopsy-proven cases, AE incidence among patients with RA-UIP was reported to be 11.1%, similar to that among patients with IPF.4 The correlation between pathological and radiological UIP patterns has been established in IPF, but not in RA-ILD.19 In the current study, determination of a UIP pattern on HRCT exhibited high specificity and positive predictive values for the detection of pathological UIP pattern. Therefore, a typical UIP pattern on HRCT was assumed to be highly suggestive of pathological UIP pattern in patients with RA-ILD as well as IPF.15 19 Collectively, these results suggest that AE incidence in a subgroup with pathological UIP pattern or a UIP pattern on HRCT may be higher than that in other patterns.

The current study also identified that MTX usage was associated with the development of AE. MTX is widely used to treat RA, although its toxicity affects the pulmonary system. Diagnostic criteria for MTX-associated pneumonitis (MTX-pneumonitis) have been proposed previously.20 However, the specificity of the criteria has not been fully examined as yet. MTX-pneumonitis typically occurs with the acute/subacute onset early in the course of MTX treatment,20–23 in particular, mostly within the first year24 and often presents a hypersensitive pneumonitis pattern. Patients with MTX-pneumonitis generally respond to discontinuation of MTX or corticosteroid treatment and have a favourable prognosis.20–23 In the current study, 6 of 11 patients with AE had received MTX, and five of the six patients had been treated for three or more years. The remaining patient had been treated for 1 year. In all six patients, their respiratory conditions progressively deteriorated despite discontinuation of MTX, and they poorly responded to high-dose corticosteroid. Consequently, on the basis of inconsistency in terms of MTX treatment duration and clinical features, we diagnosed these patients with AE of RA-ILD.

Similar to AE in patients with IPF, the aetiology of AE in RA-ILD is unknown; however, several reports have suggested that AE may be a distinct manifestation of the primary disease process, a distinct condition associated with undiagnosed infection, or a subsequent acceleration of a fibroproliferative process caused by acute direct stress to the lung.1 In the current study, DAS28-CRP in all patients with AE showed low disease activity or remission at the time of AE occurrence, and no significant difference in articular disease activities was observed between AE group and non-AE group or regardless of MTX treatment; therefore, RA activity may not be related to AE occurrence, a finding similar to that of a previous study.4 MTX possibly accelerates the fibroproliferative process of RA-ILD. It was reported that MTX treatment was a risk factor for RA-ILD progression.12 For RA-ILD, MTX may be associated not only with newly developing drug-induced pneumonitis but also with deterioration of pre-existing ILD, including AE.

This study found that patients with a UIP pattern on HRCT had significantly poorer survival than those with a non-UIP pattern. In addition, AE was a prognostic factor for poor outcome. AE has a serious impact on the survival of patients with IPF,18 and it may also affect the prognosis in other ILDs.3 4 Consistent with these reports, the current study revealed that 7 (64%) of 11 patients with AE died of respiratory failure, giving rise to high in-hospital mortality, and that survival in the AE group was significantly poorer than that in the non-AE group. Therefore, AE is suggested to be a predictor of poor prognosis in patients with RA-ILD as well as patients with IPF.

Other prognostic factors in RA-ILD have been reported, including pathological UIP,25–29 UIP pattern on HRCT30 and age at RA-ILD onset.31 In the current study, pathological UIP could not be identified as prognostic factors because the number of biopsy-proven cases were small. However, we observed similar results regarding UIP pattern on HRCT and age at RA-ILD onset.

In our study, the average time between age at the onset of RA and that of RA-ILD was relatively shorter than some previous reports.7 8 However, Gabbay et al11 reported that nearly 60% of the patients have ILD in the recent onset RA. In another point of view, since the current authors’ institution is regional referral centre for ILD, referral bias might have increased the proportion of patients with early-stage ILD, leading above results.

This study had several limitations. First, given its retrospective study design, it is subject to several possible biases. For instance, selection and recall bias may exist. Second, because of the relatively small sample size, it may be difficult to determine the precise incidence of AE and the number of event (AE occurrence or death) was too small to perform multivariate analysis. In this analysis, the incidence of extra-articular manifestations beyond ILD and the proportion of current/former smokers in AE group were higher than those in non-AE group (27% vs 13% and 82% vs 55%, respectively), with no statistically significant differences. Such differences might be statistically significant in a larger study. Therefore, larger studies are necessary to confirm our results. Third, because the presence of a UIP pattern on HRCT had low sensitivity and negative predictive value for the detection of pathologic UIP, it was likely that some patients with a non-UIP pattern on HRCT may have had pathological UIP. HRCT criteria used in our study do not aim to detect pathological UIP but to clinically diagnose IPF and to exclude alternative diagnosis.15 The frequency of honeycombing on HRCT differs between RA-ILD and IPF, and some ILDs by other causes including RA-ILD have some of the findings inconsistent with UIP. Therefore, HRCT pattern in RA-ILD may be more frequently interpreted as non-UIP pattern than that in IPF. In our study, two of five patients with histopathological UIP in the absence of a UIP pattern on HRCT developed AE. Thus, SLB may have to be considered for these patients to make pathological diagnosis and to predict AE. Finally, RA includes a variety of manifestations. Therefore, other comorbidities may have affected the results.

In conclusion, older age at ILD diagnosis, UIP pattern on HRCT and MTX usage are associated with the development of AE in patients with RA-ILD. Furthermore, the mortality associated with AE is high and AE is prognostic factor for poor outcome. Larger prospective studies investigating AEs in RA-ILD are indicated.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the help of Dr T Tsuchiya in the statistical advice. This study was partly supported by the Diffuse Lung Diseases Research Group from the ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan.

Footnotes

Contributors: HH, YN, TS and KC designed the research; HH, DH, TF and NI contributed in acquisition of the data; HH, YN, TJ, HS, TC, MK, NE and TS interpreted and analysed the data. HH, YN, TJ and TC wrote the paper; HS, MK, DH, NE, TF, NI, TS and KC revised the paper. All authors approved the final version of the paper.

Funding: This study was partly supported by a grant to the Diffuse Lung Diseases Research Group from the minisry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Institutional Review Board of the Hamamatsu University School of Medicine approved this study (approval number 24–191) and waived patient approval or informed consent because the study involved a retrospective review of patient records and images.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Collard HR, Moore BB, Flaherty KR, et al. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis clinical research network investigators. Acute exacerbations of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;176:636–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Churg A, Wright JL, Tazelaar HD. Acute exacerbations of fibrotic interstitial lung disease. Histopathology 2011;58:525–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Suda T, Kaida Y, Nakamura Y, et al. Acute exacerbation of interstitial pneumonia associated with collagen vascular diseases. Respir Med 2009;103:846–53 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Park IN, Kim DS, Shim TS, et al. Acute exacerbation of interstitial pneumonia other than idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2007;132:214–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee DM, Weinblatt ME. Rheumatoid arthritis. Lancet 2001;358:903–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanoue LT. Pulmonary manifestations of rheumatoid arthritis. Clin Chest Med 1998;19:667–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Turesson C, O'Fallon WM, Crowson CS, et al. Extra-articular disease manifestations in rheumatoid arthritis: incidence trends and risk factors over 46 years. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:722–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Norton S, Koduri G, Nikiphorou E, et al. A study of baseline prevalence and cumulative incidence of comorbidity and extra-articular manifestations in RA and their impact on outcome. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2013;52:99–110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Carmona L, González-Alvaro I, Balsa A, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis in Spain: occurrence of extra-articular manifestations and estimates of disease severity. Ann Rheum Dis 2003;62:897–900 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dawson JK, Fewins HE, Desmond J, et al. Fibrosing alveolitis in patients with rheumatoid arthritis as assessed by high resolution computed tomography, chest radiography, and pulmonary function tests. Thorax 2001;56:622–7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gabbay E, Tarala R, Will R, et al. Interstitial lung disease in recent onset rheumatoid arthritis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1997;156:528–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gochuico BR, Avila NA, Chow CK, et al. Progressive preclinical interstitial lung disease in rheumatoid arthritis. Arch Intern Med 2008;168:159–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mori S, Cho I, Koga Y, et al. Comparison of pulmonary abnormalities on high-resolution computed tomography in patients with early versus longstanding rheumatoid arthritis. J Rheumatol 2008;35:1513–21 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Arnett FC, Edworthy SM, Bloch DA, et al. The American Rheumatism Association 1987 revised criteria for the classification of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1988;31:315–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Raghu G, Collard HR, Egan JJ, et al. ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Committee on Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis. An official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT statement: idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: evidence-based guidelines for diagnosis and management. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;183:788–824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society International Multidisciplinary Consensus Classification of the Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002;165:277–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hyzy R, Huang S, Myers J, et al. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Chest 2007;132:1652–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Song JW, Hong SB, Lim CM, et al. Acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: incidence, risk factors and outcome. Eur Respir J 2011;37:356–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim EJ, Collard HR, King TE., Jr Rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease: the relevance of histopathologic and radiographic pattern. Chest 2009;136:1397–405 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kremer JM, Alarcón GS, Weinblatt ME, et al. Clinical, laboratory, radiographic, and histopathologic features of methotrexate-associated lung injury in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a multicenter study with literature review. Arthritis Rheum 1997;40:1829–37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Alarcón GS, Kremer JM, Macaluso M, et al. Risk factors for methotrexate-induced lung injury in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. A multicenter, case-control study. Methotrexate-Lung Study Group. Ann Intern Med 1997;127:356–64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salliot C, van der Heijde D. Long-term safety of methotrexate monotherapy in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a systematic literature research. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1100–4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Imokawa S, Colby TV, Leslie KO, et al. Methotrexate pneumonitis: review of the literature and histopathological findings in nine patients. Eur Respir J 2000;15:373–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saravanan V, Kelly CA. Reducing the risk of methotrexate pneumonitis in rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2004;43:143–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nakamura Y, Suda T, Kaida Y, et al. Rheumatoid lung disease: prognostic analysis of 54 biopsy-proven cases. Respir Med 2012;106:1164–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Yousem SA, Colby TV, Carrington CB. Lung biopsy in rheumatoid arthritis. Am Rev Respir Dis 1985;131:770–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lee HK, Kim DS, Yoo B, et al. Histopathologic pattern and clinical features of rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Chest 2005;127:2019–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yoshinouchi T, Ohtsuki Y, Fujita J, et al. Nonspecific interstitial pneumonia pattern as pulmonary involvement of rheumatoid arthritis. Rheumatol Int 2005;26:121–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Park JH, Kim DS, Park IN, et al. Prognosis of fibrotic interstitial pneumonia: idiopathic versus collagen vascular disease-related subtypes. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2007;175:705–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kim EJ, Elicker BM, Maldonado F, et al. Usual interstitial pneumonia in rheumatoid arthritis-associated interstitial lung disease. Eur Respir J 2010;35:1322–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Koduri G, Norton S, Young A, et al. ERAS (Early Rheumatoid Arthritis Study). Interstitial lung disease has a poor prognosis in rheumatoid arthritis: results from an inception cohort. Rheumatology (Oxford) 2010;49:1483–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.