Abstract

Objectives

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is the second most common form of neurodegenerative dementia after Alzheimer's disease (AD). DLB is characterised by intracytoplasmic inclusions called Lewy bodies that are often seen in the brainstem. Because modulation of the respiratory rhythm is one of the most important functions of the brainstem, patients with DLB may exhibit dysrhythmic breathing. This hypothesis has not yet been systematically studied. Therefore, we evaluated the association between DLB and dysrhythmic breathing.

Design

In this cross-sectional study consecutive inpatients who were admitted for the evaluation of progressive cognitive impairment were enrolled. We assessed breathing irregularity using polysomnographic recordings on bed rest with closed eyes, without reference to the clinical differentiation among DLB, AD and having no dementia.

Setting

Single centre in Japan.

Participants

14 patients with DLB , 21 with AD and 12 without dementia were enrolled in this study.

Primary outcome measures

The coefficient of variation (CV) of the breath-to-breath time was calculated. We also examined the amplitude spectrum A(f) obtained using the fast Fourier transform and Shannon entropy S of A(f) in patients with DLB compared with patients with AD and patients without dementia.

Results

The values of CV and entropy S were significantly higher in patients with DLB than in patients with AD and patients without dementia. No significant differences were observed between patients with AD and patients without dementia.

Conclusions

Patients with DLB exhibit dysrhythmic breathing compared with patients with AD and patients without dementia. Dysrhythmic breathing is a new clinical feature of DLB and the spectral analysis of breathing patterns can be clinically useful for the diagnostic differentiation of DLB from AD.

Keywords: RESPIRATORY MEDICINE (see Thoracic Medicine), SLEEP MEDICINE

Article summary.

Strengths and limitations of this study

Dysrhythmic breathing is a completely novel topic in DLB.

This study is a cross-sectional, small-sized pilot study.

The patholocgical diagnosis of DLB could not be obtained.

Introduction

Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) is a neurodegenerative disease characterised by parkinsonism, visual hallucinations and cognitive fluctuations. DLB is now thought to be the second most common form of dementia after Alzheimer's disease (AD), affecting 15–25% of elderly demented patients.1 The clinical diagnostic criteria for DLB were first published in 1996 and modified in 2005.1 2 The central feature of DLB is progressive cognitive decline. The core features include recurrent visual hallucinations, spontaneous features of parkinsonism and fluctuating cognition with pronounced variations in attention and alertness. These diagnostic criteria require clinical evaluation by a trained neurologist and include few objective markers. Although Single Photon Emission CT (SPECT) and 123I-metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) myocardial scintigraphy are useful for making the differential diagnosis of DLB,3–5 these examinations are too expensive to be generally utilised. DLB is characterised by intracytoplasmic inclusions called Lewy bodies that consist of filamentous protein granules composed of α-synuclein and ubiquitin. Lewy bodies are often seen in the brainstem and in limbic and cortical neurons.2 However, the brainstem serves as the connection among the cerebral hemispheres and the cerebellum, and is responsible for basic vital functions. Modulation of the respiratory rhythm is one of the most important functions of the brainstem. In cases of brain disorders, such as Wallenberg syndrome and brain tumours, it is known that respiratory patterns sometimes become ataxic. Because brainstem neurodegeneration is often seen in patients with DLB, the respiratory patterns of patients with DLB might be dysrhythmic. However, this hypothesis has not yet been systematically studied and no controlled data have been published to date. The current investigation was performed in patients with DLB, AD and patients without dementia to assess and compare breathing patterns. In addition, we evaluated the usefulness of the measurement of breathing patterns as a novel tool to aid the differential diagnosis of dementia.

Methods

Subjects

The study population comprised consecutive inpatients of the Department of Geriatric Medicine at the University of Tokyo Hospital, who were admitted for evaluation of progressive cognitive impairment. The patients underwent neuropsychological assessments, including the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE), blood tests and neuroimaging tests (MRI and SPECT). The diagnosis was performed at a consensus conference of physicians and neurologists. The diagnosis of DLB was based on the clinical diagnostic criteria proposed by McKeith et al.2 And AD was diagnosed in accordance with the National Institute of Neurological and Communicative Disorders and Stroke and the Alzheimer’s disease and Related Disorders Association.6 The group without dementia comprised patients who did not fit the criteria for dementia in the medical and neurological examinations. Between November 2010 and June 2012, 70 patients were enrolled in this study.

Exclusion criteria

We evaluated the breathing patterns of patients with DLB, with AD and patients without dementia. Patients with cognitive impairments other than AD or DLB (eg, normal pressure hydrocephalus and vascular dementia) were excluded.

Breathing irregularities are associated with certain environments such as high altitudes, medical conditions, such as heart failure and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and the usage of opioids or levodopa.7 8 We excluded one patient who reported breathing problems, including dyspnoea. We also excluded four patients who were taking levodopa and dopamine agonists. No patients were using opioids. We excluded three patients whose recorded respiratory signal data were insufficient due to noise.

Recordings of respiration

The patients underwent 30 min or more of recordings of respiration on bed rest with closed eyes in the inpatient ward by using the device for polysomnography (Somnotrac Pro, CareFusion, San Diego, California, USA). The recordings included two EEG leads (C3-A2 and O2-A1), electro-oculogram and submental electromyogram (EMG). Oronasal thermistor channel and arterial oxygen saturation (finger oximetry) were also monitored. All recordings were scored visually by an experienced rater according to the standard criteria.9

Five consecutive minutes of stable respiratory signals measured while the patients were awake were extracted from the recordings. Stable respiratory signals during wakefulness were identified using the respiratory signals themselves, arterial oxygen saturation, EMG and EEG. Wakefulness was confirmed using EEG. When the amplitude of the EMG signal that detected any body movements was high, that part of the signal was considered to have occurred during movement and was determined to be inappropriate for analysis. Epochs including apnoeas and hypopneas were also excluded.

Analysis of respiratory signals

Five minutes of stable respiratory signals were analysed. The breath-to-breath time was calculated for each respiration. To assess breathing irregularities, the coefficient of variation, CV ((SD/mean)×100) for the breath-to-breath time was calculated. The respiratory rate was also calculated.

In addition, we examined the amplitude spectrum A(f) obtained using fast Fourier transform (FFT) for analysing oscillation patterns in the respiratory signals. A(f) represents the amplitude distribution as a function of frequency. To avoid the possibility of spectral leakage, the signals were windowed by multiplying them by a Hamming window (w(n)):

Then, the amplitude spectrum of the respiratory signals was analysed using the FFT of the Hamming-windowed signal.10 Furthermore, according to Shannon entropy, we determined the spectral entropy S based on normalised A(f) to assess breathing irregularities:

|

To reduce the influence of artifact in the respiratory signals and FFT, we restricted the frequency of analysing Shannon entropy. Based on the results of the breath-to-breath time analysis (1.7–7.6 s, namely 0.13–0.59 Hz), we determined the validated frequency of 0.1–0.6 Hz.

Statistical analysis

The distribution of data was examined using the Shapiro-Wilk test. If data were normally distributed, one-way analysis of variance with Games-Howell post hoc tests was applied for group comparisons. If the data deviated significantly from normality, the Kruskal-Wallis test was used, followed by evaluation with the Mann-Whitney U test for multiple comparisons, with the p values being corrected according to the Bonferroni method. In correlation analysis, the Spearman rank correlation coefficient was used. The χ² test was used to compare categorical variables, such as gender.

The diagnostic cut-off points for the CV value and Shannon entropy S to discriminate between DLB and AD were estimated for each outcome by maximising the Youden index. The discrimination ability was assessed by the area under the curve (AUC). Using this threshold, the sensitivity and specificity were calculated.

All of the statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS software program (V.19.0, SPSS inc, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Statistical significance was defined as p values <0.05.

Results

Patient characteristics

Fourteen patients with DLB, 21 with AD and 12 without dementia were enrolled in this study. Among the 14 patients in the DLB group, 9 patients had probable DLB and 5 patients had possible DLB. The diagnoses in the five possible DLB patients were all supported by the typical findings in SPECT: generalised low uptake, reduced occipital activity and relatively preserved hippocampal blood flow. Table 1 shows the characteristics of the patients. The age and sex distributions were not significantly different among the three groups. No significant difference was found between the DLB group and the AD group in the MMSE. The use of medications for hypertension, hyperlipidaemia and diabetes mellitus were similar between the groups. Four patients in the DLB group, five patients in the AD group and no patients in the group without dementia had taken donepezil.

Table 1.

Characteristics of patients with DLB, with AD and without dementia

| Characteristics | Patients with DLB | Patients with AD | Patients without dementia | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of patients | n=14 | n=21 | n=12 | p Value |

| Age (years) | 81.5 (5.6) | 79.6 (7.8) | 78.5 (4.3) | n.s. |

| Sex (men/women) | 6/8 | 7/14 | 4/8 | n.s. |

| MMSE | 21.0 (3.8) | 21.2 (3.4) | 27.8 (2.1) | <0.001* |

| Hypertension | 4 | 9 | 3 | n.s. |

| Hyperlipidaemia | 2 | 1 | 0 | n.s. |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1 | 1 | 1 | n.s. |

Values expressed as mean (SD) or number.

*One-way analysis of variance with Games-Howell post hoc tests (DLB vs AD: n.s., DLB vs without dementia: p<0.001, AD vs without dementia: p<0.001)

AD, Alzheimer's disease; DLB, dementia with Lewy bodies; MMSE, Mini-Mental State Examination; n.s., not significant.

Breathing patterns

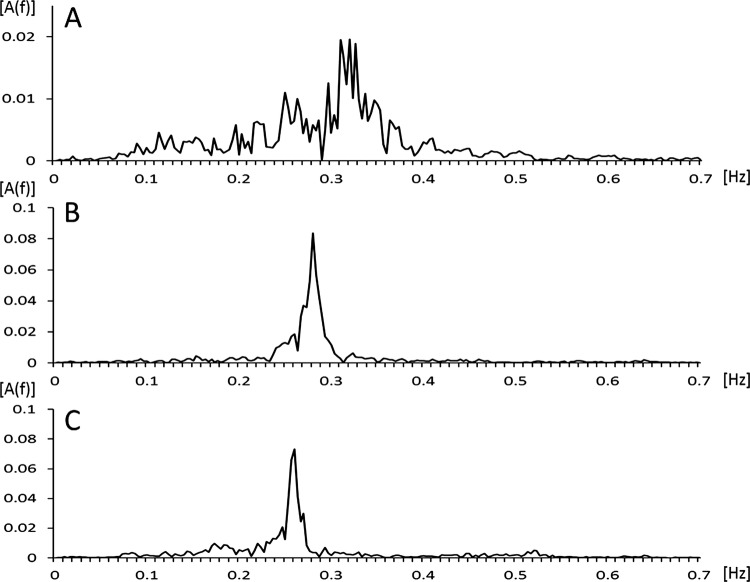

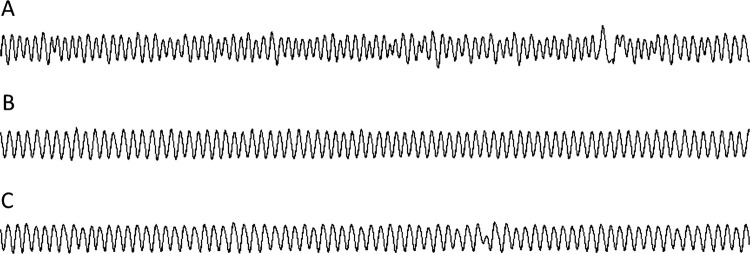

Figure 1 shows examples of flow signals during wakefulness for a patient with DLB, with AD and without dementia. Figure 2 shows examples of the characteristic patterns of the amplitude spectrum A(f). The patient with AD and without dementia exhibited a sharp peak in the spectrum. However, the amplitude spectrum of the patient with DLB was distributed over the whole displayed frequency area. These tracings indicate the occurrence of more irregular breathing patterns in the patient with DLB compared with that observed in the patient with AD and the patient without dementia.

Figure 1.

Typical flow patterns of a patient with DLB (A), a patient with AD (B) and a patient without dementia (C) observed in epochs of 5 min. Respiratory pattern is more irregular in the patient with DLB as compared with the patient with AD and the patient without dementia. AD, Alzheimer's disease; DLB, dementia with Lewy bodies.

Figure 2.

The typical power spectrum of a patient with DLB (A), a patient with AD (B) and a patient without dementia (C) obtained by fast Fourier transform. The amplitude spectrum of the patient with DLB is distributed over the whole displayed frequency. AD, Alzheimer's disease; A(f), amplitude spectrum; DLB, dementia with Lewy bodies.

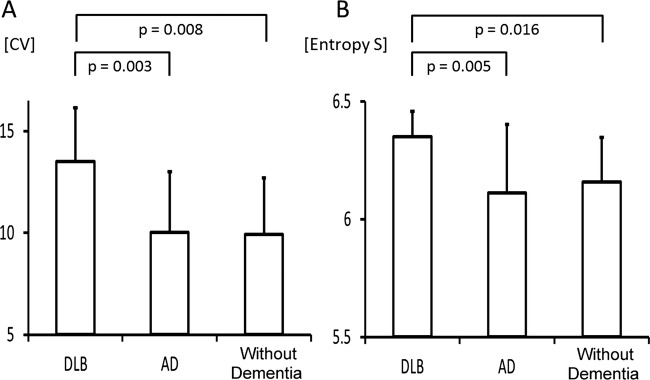

The respiratory rates calculated from the average breath-to-breath time in patients with DLB, with AD and patients without dementia were 16.2 (3.2), 17.7 (2.7) and 18 (2.3)/min, respectively (mean (SD)). These differences were not statistically significant. However, the CV value for the breath-to-breath time in patients with DLB was significantly higher than in either the patients with AD or the patients without dementia (13.5 (2.6), 10 (3) and 9.9 (2.8), respectively; figure 3A). To discriminate the patients with DLB from those with AD using the CV value, the most favourable diagnostic threshold was found to be 10.2 (AUC=0.79). This threshold had a sensitivity of 92.9% and a specificity of 61.9%.

Figure 3.

(A) Coefficient of variation for breath-to-breath respiratory time in patient with DLB, patient with AD and patients without dementia. One-way analysis of variance with Games-Howell post hoc tests; significant differences in DLB versus AD (p =0.003) and DLB versus without dementia (p=0.008). (B) The comparison of Shannon entropy S in DLB patients, AD patients and patients without dementia. One-way analysis of variance with Games-Howell post hoc tests; significant differences in DLB versus AD (p=0.005) and DLB versus without dementia (p=0.016). Values are mean±SD. AD, Alzheimer's disease; CV, coefficient of variation; DLB, dementia with Lewy bodies; n.s., not significant.

The results of the comparison of Shannon entropy S are summarised in figure 3B. The values of Shannon entropy S were significantly higher in patients with DLB than in patients with AD and patients without dementia (6.35 (0.11), 6.11 (0.29) and 6.16 (0.19), respectively). To discriminate patients with DLB from those with AD using the Shannon entropy S value, the most favourable diagnostic threshold was found to be 6.18 (AUC=0.77). This threshold had a sensitivity of 100% and a specificity of 57.1%.

These findings indicate the diversity of breathing frequencies, that is, respiratory dysrhythmia, in patients with DLB.

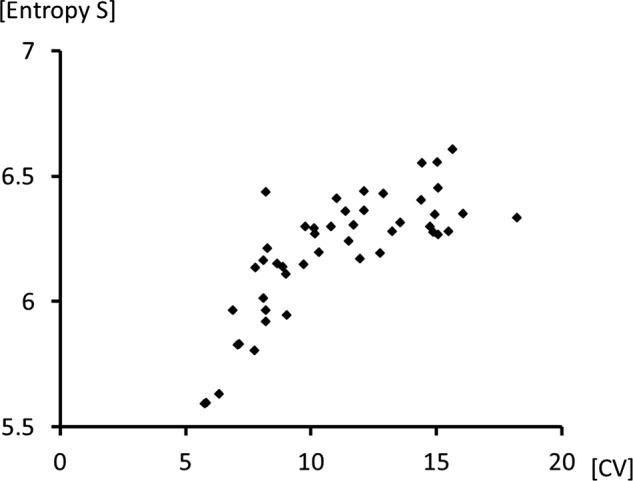

Comparison of CV and Shannon entropy S

To assess breathing irregularities, we used two different methods, namely, we compare CV and Shannon entropy S. These two methods are independent approaches to the assessment of breathing patterns; however, a significant correlation (Spearman r=0.78, p<0.001) was observed between these two values (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Scatter plot showing the relationship between the coefficient of variation for breath-to-breath respiratory time and the value of Shannon entropy S. A significant correlation (r=0.78, p<0.001) was found between the coefficient of variation (CV) and the Shannon entropy S.

Discussion

In this study, we observed that patients with DLB exhibit dysrhythmic breathing compared to patients with AD and patients without dementia.

The modulation of the respiratory rhythm is closely associated with the brainstem.11 In particular, the pre-Bötzinger complex (pre-BötC) and the retro-trapezoid nucleus/parafacial respiratory group (RTN/pFRG) are thought to be very important for respiratory rhythm regulation.12–14 For this reason, respiratory dysrhythmia may occur in cases of brainstem disorders, such as Wallenberg syndrome and brain tumours. In patients with DLB, Lewy bodies are often seen in the brainstem; however, it remains unknown whether the localisation and density of Lewy bodies are strongly associated with the symptoms of DLB. It is possible, considering the neurodegenerative aspects of DLB, that localisation of Lewy bodies in the brainstem causes respiratory dysrhythmia. One report has indicated that visual hallucinations are associated with increased numbers of Lewy bodies in the temporal lobe and amygdala, each of these areas being implicated in the generation of complex visual images.15 In addition, concerning the association between respiration and DLB, Mizukami et al16 reported the occurrence of decreased ventilatory responses to hypercapnia in patients with DLB. Furthermore, respiratory insufficiency, sleep-disordered breathing and central respiratory failure are known to occur in patients with multiple system atrophy,17 18 which is an α-synucleinopathies, similar to DLB.

In this study, we also analysed the breathing patterns of patients without dementia. The CV for breath-to-breath time in patients without dementia was not significantly different from that reported in previous studies of control patients.19 20 Although the complication with hypertension was greater in AD group than in DLB group, no significant differences were found in the measures of breathing patterns between patients with hypertension and the patients without hypertension (data not shown).

Patients with DLB exhibit many clinical features other than dementia, visual hallucinations and parkinsonism. For example, Rapid Eye Movement sleep behaviour disorder, severe autonomic dysfunctions, such as orthostatic hypotension, repeated syncope and systematised delusions, can be seen in patients with DLB.21 Furthermore, in a previous study, we reported a high frequency of periodic limb movements in patients with DLB.22 The results of the current study indicating that DLB patients exhibit dysrhythmic breathing compared with normal patients suggest that irregular breathing patterns may be a new clinical feature of DLB.

Currently, DLB and AD are diagnosed according to their respective clinical diagnostic criteria,2 6 and differentiation of these two diseases is frequently difficult. Our findings of different breathing patterns between patients with DLB and AD suggest the usefulness of the spectral analysis of breathing for discriminating patients with DLB from those with AD. Because the diagnostic threshold had a high sensitivity in our study, the spectral analysis of breathing may be useful for making an exclusive diagnosis. While the utilisation of SPECT and MIBG myocardial scintigraphy are limited to well-equipped hospitals, the spectral analysis of breathing can be performed more easily and with lower expenses. As a screening tool for the diagnosis of DLB, the spectral analysis of breathing patterns may be cost-effective and useful.

The FFT is an important tool for digital signal processing of the information commonly encoded in the sinusoids that form the signal. Additionally, the important information to be evaluated is the frequency and amplitude of the component sinusoids. To reduce spectral noise, a Hamming window is used that involves the multiplication of the signal by a smooth curve. The result is plotted graphically in terms of amplitude and frequency. In addition, we used Shannon entropy in this study to quantify the variability of the amplitude spectrum, namely breathing irregularities. This measure has been widely used in a range of biological applications in which quantitative descriptions of data regularity are required.23 24 The Shannon entropy indicates the degree of uncertainty and is higher when the variability of the parameter is greater.

There are several limitations to the current study. First, we included patients with possible DLB and probable DLB in the same DLB group. In addition, we did not make a pathological diagnosis of DLB or AD. A prospective investigation on the course of breathing patterns and cognitive impairment, including the eventual pathological diagnosis, should be examined in a future study. Second, no arterial blood gas analyses were performed. Therefore, a possible effect of hypercapnia or hypocapnia on breathing cannot be excluded. To evaluate more precisely, arterial blood gas analyses should be examined in a future study, as well. Third, we could not make the raters of respiratory measures completely blinded to the clinical symptoms of the patients, although the final diagnosis of dementia had been made independently, and the analysis of respiratory measures had been performed objectively according to the predetermined protocol. Finally, the number of patients in each group was relatively small. We could not rule out the contribution of other comorbid factors to irregular breathing. However, our data provide the first evidence of irregular breathing in DLB patients. In a future study, an additional investigation involving a larger number of patients should be performed.

In conclusion, we found that DLB patients exhibit dysrhythmic breathing compared with that observed in AD patients and patients without dementia. Ataxic breathing may be a new clinical feature of DLB, and the spectral analysis of breathing patterns may be clinically useful for the diagnostic differentiation of DLB from AD.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank all participants.

Footnotes

Contributors: SH was involved in design, analysis, interpretation and drafting of the article. YY was responsible for conception, design, analysis, interpretation and drafting of the article. YU-K and KI were involved in design. MT and TM were involved in analysis. MA and YO were involved in design and interpretation. All authors had full access to the data and take responsibility for its integrity and the accuracy of the analysis.

Funding: This work was supported by grants-in-aid for young scientists and scientific research from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture of Japan (grant code 24591154), and Research Grants from the Mitsui Sumitomo Insurance Welfare Foundation.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Ethics approval: The study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Graduate School of Medicine, University of Tokyo, and written informed consent was obtained from all participants before the study.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.McKeith IG, Galasko D, Kosaka K, et al. Consensus guidelines for the clinical and pathologic diagnosis of dementia with Lewy bodies: report of the consortium on DLB international workshop. Neurology 1996;47:1113–24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McKeith IG, Dickson DW, Lowe J, et al. Diagnosis and management of dementia with Lewy bodies: third report of the DLB consortium. Neurology 2005;65:1863–72 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lobotesis K, Fenwick JD, Phipps A, et al. Occipital hypoperfusion on SPECT in dementia with Lewy bodies but not AD. Neurology 2001;56:643–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoshita M, Taki J, Yamada M. A clinical role for [(123)I]MIBG myocardial scintigraphy in the distinction between dementia of the Alzheimer's-type and dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2001;71:583–8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hanyu H, Shimizu S, Hirao K, et al. Comparative value of brain perfusion SPECT and [(123)I]MIBG myocardial scintigraphy in distinguishing between dementia with Lewy bodies and Alzheimer's disease. Eur J Nucl Med Mol Imaging 2006;33: 248–53 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McKhann G, Drachman D, Folstein M, et al. Clinical diagnosis of Alzheimer's disease: report of the NINCDS-ADRDA Work Group under the auspices of Department of Health and Human Services Task Force on Alzheimer's Disease. Neurology 1984;34:939–44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rice JE, Antic R, Thompson PD. Disordered respiration as a levodopa-induced dyskinesia in Parkinson's disease. Mov Disord 2002;17:524–27 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ferguson LM, Drummond GB. Acute effects of fentanyl on breathing pattern in anaesthetized subjects. Br J Anaesth 2006;96: 384–90 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Iber C, Ancoli-Israel S, Chesson A, et al. For the American Academy of Sleep Medicine. The AASM manual for the scoring of sleep and associated events; rules, terminology and technical specifications. 1st edn Westchester, IL: American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stearns SD, Hush DR. Nonrecursive Digital Systems, In: Steams SD, Hush DR. eds. Digital signal analysis. 2nd edn EnglewoodCliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall International Editions, 1990:155–62 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ahn SH, Kim JH, Kim DU, et al. Interaction between sleep-disordered breathing and acute ischemic stroke. J Clin Neurol 2013;9:9–13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mulkey DK, Stornetta RL, Weston MC, et al. Respiratory control by ventral surface chemoreceptor neurons in rats. Nat Neurosci 2004;7:1360–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Onimaru H, Homma I. A novel functional neuron group for respiratory rhythm generation in the ventral medulla. J Neurosci 2003;23:1478–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith JC, Ellenberger HH, Ballanyi K, et al. Pre-Bötzinger complex: a brainstem region that may generate respiratory rhythm in mammals. Science 1991;254:726–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harding AJ, Broe GA, Halliday GM. Visual hallucinations in Lewy body disease relate to Lewy bodies in the temporal lobe. Brain 2002;125:391–403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mizukami K, Homma T, Aonuma K, et al. Decreased ventilatory response to hypercapnia in dementia with Lewy bodies. Ann Neurol 2009;65:614–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schwarzacher SW, Rüb U, Deller T. Neuroanatomical characteristics of the human pre-Bötzinger complex and its involvement in neurodegenerative brainstem diseases. Brain 2011;134:24–35 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Glass GA, Josephs KA, Ahlskog JE. Respiratory insufficiency as the primary presenting symptom of multiple-system atrophy. Arch Neurol 2006;63:978–81 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wuyts R, Vlemincx E, Bogaerts K, et al. Sigh rate and respiratory variability during normal breathing and the role of negative affectivity. Int J Psychophysiol 2011;82:175–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamauchi M, Tamaki S, Yoshikawa M, et al. Differences in breathing patterning during wakefulness in patients with mixed apnea-dominant vs obstructive-dominant sleep apnea. Chest 2011;140:54–61 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pao WC, Boeve BF, Ferman TJ, et al. Polysomnographic findings in dementia with Lewy bodies. Neurologist 2013;19:1–6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hibi S, Yamaguchi Y, Umeda-Kameyama Y, et al. The high frequency of periodic limb movements in patients with Lewy body dementia. J Psychiatr Res 2012;46:1590–4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Webber CL, Jr, Zbilut JP. Dynamical assessment of physiological systems and states using recurrence plot strategies. J Appl Physiol 1994;76:965–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Larsen PD, Trent EL, Galletly DC. Cardioventilatory coupling: effects of IPPV. Br J Anaesth 1999;82:546–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.