Abstract

Introduction

The ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS) degrades 80 – 90% of intracellular proteins. Cancer cells take advantage of the UPS for their increased growth and decreased apoptotic cell death. Thus, the components that make up the UPS represent a diverse group of potential anti-cancer targets. The success of the first-in-class proteasome inhibitor bortezomib not only proved that the proteasome is a feasible and valuable anti-cancer target, but also inspired researchers to extensively explore other potential targets of this pathway.

Areas covered

This review provides a broad overview of the UPS and its role in supporting cancer development and progression, especially in aspects of p53 inactivation, p27 turnover and NF-κB activation. Also, efforts toward the development of small molecule inhibitors (SMIs) targeting different steps in this pathway for cancer treatment are reviewed and discussed.

Expert opinion

Whereas some of the targets in the UPS, such as the 20S pro-teasome, Nedd8 activating enzyme and HDM2, have been well-established and validated, there remains a large pool of candidates waiting to be investigated. Development of SMIs targeting the UPS has been largely facilitated by state-of-the-art technologies such as high-throughput screening and computer-assisted drug design, both of which require a better understanding of the targets of interest.

Keywords: cancer therapy, deubiquitinases, E3 ligases, proteasome, small molecule inhibitors, ubiquitin

1. Introduction

The ubiquitin–proteasome system (UPS) is a rather complicated system in charge of degrading 80 – 90% of intracellular proteins that are aberrantly folded or typically short-lived. The remaining 10 – 20% of intracellular proteins, composed of membrane-associated proteins and alien proteins captured during endocytosis, are degraded by the lysosome [1]. Generally speaking, the UPS is made up of six components: ubiquitin (Ub), the Ub-activating enzyme (E1), a group of Ub-conjugating enzymes (E2s), a larger group of Ub ligases (E3), the proteasome and the deubiquitinases (DUBs). Protein degradation by the UPS is a highly-controlled process that involves two distinct and successive steps: i) ubiquitination, which adds a poly-Ub tag to the targeted protein and ii) proteasomal degradation, which degrades the tagged protein into oligopeptides.

The UPS plays an important role in both cell proliferation and survival (i.e., evasion of apoptosis). It regulates the turnover of key proteins involved in cell-cycle progression, such as the cyclins, p27 and p53. It also plays an essential role in regulating one of the most important cell survival pathways, the NF-κB pathway. Knowing this, cancer cells utilize the UPS to achieve aberrant growth and resistance to apoptosis, which provides us with a unique, selective target for the discovery of novel drugs in the fight against cancer. In this review, the supporting roles of the UPS in cancer cell growth and anti-apoptosis are discussed and the potential therapeutic targets in the UPS highlighted. We also elaborate on the most recent progress in the development of small molecule inhibitors against different components of the Ub–proteasome pathway for cancer treatment.

2. The UPS

2.1 Ubiquitination

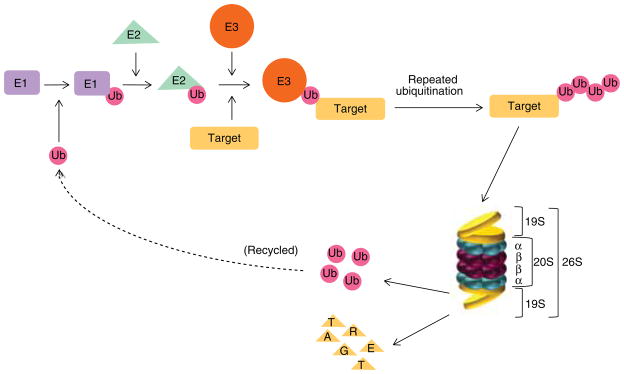

Ubiquitination is a multi-step process that transfers Ub to specific target proteins. Ub is a highly conserved small (8.5 kDa) regulatory protein consisting of 76 amino acids, seven of which are lysines. Ub conjugation occurs through an enzymatic cascade that involves three distinct enzymes, Ub-activating (E1), Ub-conjugating (E2) and Ub-ligating (E3). Ub is first activated by the ATP-dependent formation of a thioester linkage between the C-terminus of Ub and the cysteine residue of E1, then transferred to an E2 through an additional thio-ester intermediate, and finally transferred from the E2- to the E3-bound substrate directly or via a third high-energy thio-ester intermediate, resulting in the formation of an isopeptide bond between the C-terminus of an Ub and the lysine residue of the substrate or another Ub (Figure 1).

Figure 1. A schematic diagram of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway and the structure of the 26S proteasome.

Protein degradation by the UPS involves two distinct and successive steps, ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation. Ubiquitin conjugation occurs through an enzymatic cascade that involves three distinct enzymes, Ub-activating (E1), Ub-conjugating (E2) and Ub-ligating (E3). Ubiquitin is first activated by E1, then transferred to an E2, and finally transferred from the E2- to the E3-bound substrate. The poly-ubiquitinated proteins with a ubiquitin chain containing four or more K48-linkages are then directed to the 26S proteasome complex where the poly-ubiquitin chain will be removed and recycled and the protein substrates degraded into oligopeptides. The 26S proteasome complex is composed of the 20S catalytic core and two 19S regulatory particles. The 20S core is formed by two identical α rings and two identical β rings stacked in a symmetrical manner with the outside α rings surrounding the inner β rings. Each α or β ring contains seven different subunits, named α1-α7 or β1-β7, respectively. The 19S regulatory particle binds to both ends of the 20S core proteasome.

The human Ub system is thought to encode one E1, approximately 50 E2s and over 500 E3s, forming an E1–E2–E3 hierarchical pyramid. Ube1 (Uba1 in yeast) was thought to be the sole E1 responsible for Ub activation for a long time. This has been recently challenged by the discovery of an uncharacteristic E1 enzyme, designated as Ub-like modifier activating enzyme 6 (Uba6) [2].

The E2s are characterized by the presence of a highly conserved Ub-conjugating catalytic (UBC) fold, and classified based on the existence of additional extensions to this UBC fold: no extension (class I), N-terminal extension (class II), C-terminal extension (class III), and both N- and C-terminal extensions (class IV) [3].

The E3s can be categorized into two major types based on their homology of E2-binding domains and how they facilitate Ub transfer from E2 to the substrate: the HECT (Homology to E6AP C-terminus) domain E3s, which form an intermediate with Ub through a conserved cysteine residue before transfer to the substrate, and the RING (Really Interesting New Gene) finger E3s, which act as a scaffold to bring the E2-Ub close to the substrate for the direct transfer of Ub from the E2. The HECT domain E3s contain about 30 members with E6-AP (E6-associated protein) being the first one discovered. The RING finger E3s, which contain > 500 members, can be simply subdivided into single subunit, dimeric or multisubunit E3s. The dimeric RING finger E3s are either homodimers (e.g., cIAP and TRAF2) or heterodimers (e.g., HDM2–HDMX dimer and BRCA1-BARD1 dimer). The multisubunit RING finger E3s are exemplified by the CRLs (cullin RING Ub ligases), the best characterized being SCF (Skp1-Cul1-F box protein), APC/C (anaphase promoting complex/cyclosome) and the FANC (fanconi anemia complementation) groups [4].

Depending on the lysine residue involved in the formation of the poly-Ub chain, there are several types of Ub linkages with different physiological roles including K11, K48 and K63 linkages. The K48-linked poly-Ub chains are best known for their role in targeting proteins for proteasomal degradation, whereas the K63-linked poly-Ub chains are involved in DNA repair, DNA replication and signal transduction processes. The cellular functions of K11-linked poly-Ub chains are less well-understood; recent studies have revealed their function in cell cycle control [5]. It is generally thought that the specificity of linkage in the poly-Ub chains is determined by E2s, at least in reactions involving RING finger E3s. The E2s currently reported to be responsible for the assembly of K11-, K48-, and K63-linked poly-Ub chains are Ube2S, Ube2K/Ubc1 or Ube2R1/Cdc34, and Ube2N/Ubc13–Uev1A heterodimer, respectively [6].

2.2 Proteasomal degradation

The poly-ubiquitinated proteins with a Ub chain containing four or more K48-linkages are then directed to the 26S proteasome complex where the poly-Ub chain will be removed and recycled and the protein substrates degraded into oligopeptides [7–9].

The 26S proteasome (2.4 MDa) is a multi-subunit protease complex composed of the 20S catalytic core (700 kDa) and two 19S regulatory particles (700 kDa) (Figure 1). The 20S core is formed by two identical α rings and two identical β rings stacked in a symmetrical manner with the outside α rings surrounding the inner β rings. Each α or β ring contains seven different subunits, named α1–α7 or β1–β7, respectively, among which mainly β1, β2 and β5 possess pro-teolytic activity. The β1 subunit possesses caspase-like or peptidyl-glutamyl peptide-hydrolyzing-like (PGPH-like) activity which preferentially cleaves after acidic residues, such as aspartate and glutamate; the β2 subunit possesses trypsin-like activity which preferentially cleaves after basic residues, such as arginine and lysine; and the β5 subunit possesses chymotrypsin-like activity which preferentially cleaves after hydrophobic residues, such as tyrosine and phenylalanine [7–9]. The 19S regulatory particle binds to both ends of the 20S core proteasome and is composed of a ‘lid’ and a ‘base’ (Figure 1). The ‘lid’ contains at least nine non-ATPase subunits, which remove the poly-Ub chain from the substrate by a process called deubiquitination (also see Section 2.3). The ‘base’ contains six ATPase and four non-ATPase subunits. It is responsible for the opening of the gate of the 20S proteasome, unfolding of the substrate proteins and promotion of their entry into the 20S proteasome [7–9]. Compared to the 20S core, the 19S regulatory particle is far less well characterized.

In addition to the constitutive proteasome described thus far, which contains catalytic subunits β1, β2 and β5, there also exists the immunoproteasome, which harbors different sets of catalytic subunits designated as β1i, β2i and β5i, correspondingly. On cytokine stimulation, especially interferon-γ and tumor necrosis factor-α, the expression of β1i, β2i and β5i dramatically increases and cooperatively assembles into the nascent 20S core particles to form immunoprotea-somes. The immunoproteasome is a key component during antigen processing in the immune response. Compared to the constitutive proteasome, the immunoproteasome possesses enhanced chymotrypsin- and trypsin-like activities and reduced caspase-like activity. This specialized enzymatic property endows the ability of the immunoproteasome to generate peptides that are suitable for MHC class I-mediated antigen presentation [10,11].

2.3 Deubiquitination

Deubiquitination is a process that removes Ub chains from the substrate. This process is executed by a family of isopeptidases called DUBs, which are able to cleave the isopeptide bond between the Ub and the substrate. The human genome encodes approximately one-hundred DUBs that can be divided into six subclasses: USPs (Ub-specific proteases), UCHs (Ub C-terminal hydrolases), MJDs (Machado–Joseph disease protein domain proteases), OUTs (ovarian tumor domain-containing proteases), JAMMs (JAB1/MPN/MOV34 domain-associated metalloenzymes), and the recently discovered MCPIP (monocyte chemotactic protein-induced protein) [12]. All of them are cysteine proteases except the JAMMs, which are metalloenzymes. Structural and functional analyses have revealed that different subclasses of DUBs have different preferences towards the type of poly-Ub chain linkages they act on. The USP group is the largest subclass of the DUB family with > 60 members.

Of note, there are three DUBs directly associated with the proteasome 19S regulatory particle, namely UCH-L5/UCH37, USP14/Ubp6 and POH1/Rpn11, belonging to the UCH, USP and JAMM subclasses, respectively. There are several differences between these proteasome-associated DUBs. First, Rpn11 is a constituent subunit of the 19S regulatory particle lid, whereas USP14 and UCH37 are not. Second, Rpn11 preferentially cleaves K63-linked poly-Ub chains, whereas UCH37 prefers K48-linked. Third, Rpn11 cleaves at the base of the Ub chain (where it is linked to the substrate) while UCH37 and USP14 mediate a stepwise removal of Ub from the substrate by disassembling the chain from its distal tip. Finally, Rpn11-mediated deubiquitination promotes substrate degradation, whereas USP14 and UCH37-mediated deubiquitination suppresses substrate degradation. Rpn11 is responsible for the main DUB activity at the proteasome and shows degradation-coupled activity that is suppressed until the proteasome is committed to degrade the substrate. In contrast, removal of Ub from a substrate prior to its committed proteasomal degradation can antagonize the degradation by promoting substrate dissociation from the proteasome, and both USP14 and UCH37 are believed to suppress substrate degradation in this way. Association with Rpn13, a subunit of the 19S regulatory particle base, and incorporation into the 19S regulatory particle are required for the full activation of UCH37. Similarly, the DUB activity of USP14 requires its binding to Rpn1, another non-ATPase subunit of the 19S regulatory particle base.

3. Selected substrates of the UPS as novel anticancer targets

3.1 HDM2–HDMX–p53

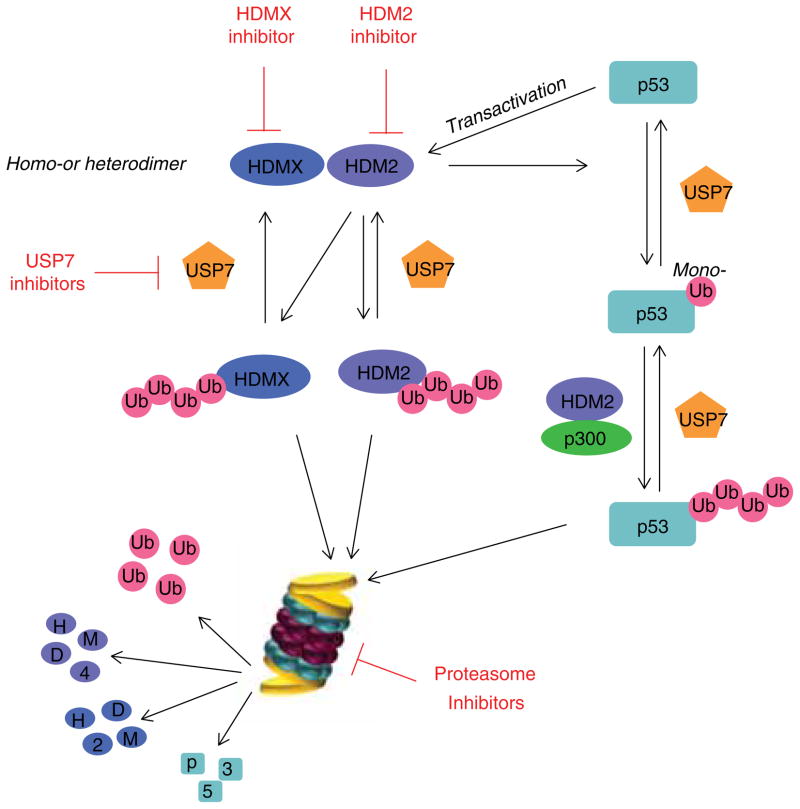

p53 is one of the two most important tumor suppressors (the other is retinoblastoma protein or RB) characterized in the past thirty years. Around 22 million cancer patients have defects in p53 signaling, with 50% harboring mutant p53 and the other 50% having functionally inactivated wild-type p53 [13]. The transactivtion activity of p53 is crucial for its tumor-suppressing function. The stability of p53 is negatively regulated by HDM2 (MDM2 in mice) and HDMX (MDMX or MDM4 in mice) E3 ligases. Amplification and/or overexpression of HDM2, leading to the inactivation of wild-type p53, have been observed in many clinical samples. Intriguingly, HDM2 itself is the product of a p53-inducible gene, forming a negative feedback loop between these two proteins. As an E3 ligase, HDM2 mediates p53 ubiquitination in the nucleus in a complex with p300/CBP and transcriptional coactivators that serve as a scaffold and are now being considered to be E4 Ub-modifying enzymes (Figure 2). Whereas HDM2 catalyzes p53 mono-ubiquitination, which is not sufficient for proteasomal degradation, the HDM2–p300 complex mediates the final p53 poly-ubiquitination, which is subject to proteasomal degradation [14]. X-ray crystallography has revealed that the interaction between p53 and HMD2 involves primarily three hydrophobic residues, Phe19, Trp23 and Leu26, from a short α-helix (amino acids 13 – 29) in the transactivation domain of p53 and a small, but deep, hydrophobic pocket at the N-terminus of HDM2, an important piece of information that has been used to develop small molecule inhibitors that interfere with HMD2-p53 binding [15].

Figure 2. Regulation of p53 stability by the ubiquitin-proteasome system.

The stability of p53 is negatively regulated by HDM2–HDMX heterodimer or HDM2–HDM2 homodimer E3 ligases. Whereas HDM2 catalyzes p53 mono-ubiquitination, which is not sufficient for proteasomal degradation, the HDM2–p300 complex mediates the final p53 poly-ubiquitination, which is subject to proteasomal degradation. On the other hand, HDM2 itself is the product of a p53-inducible gene, forming a negative feedback loop between these two proteins. Both p53 and HDM2 are substrates of USP7/HAUSP. HAUSP preferentially forms a stable HAUSP–HDM2 complex, even in the presence of excess p53. As a result, HAUSP stabilizes HDM2, leading to p53 poly-9ubiquitination and degradation. Restoration of p53 activity can be achieved by inhibitors of HDM2, HDMX, USP7 or the proteasome.

Adapted from Brown et al. with modifications [13].

On the other hand, both p53 and HDM2 are substrates of USP7/HAUSP, a DUB that efficiently cleaves high molecular weight K48-linked poly-Ub chains. Intriguingly, both p53 and HDM2 specifically recognize the N-terminus of HAUSP in a mutually exclusive manner. HAUSP preferentially forms a stable HAUSP HDM2 complex, even in the presence of excess p53 [16]. As a result, HAUSP stabilizes HDM2, leading to p53 polyubiquitination and degradation. In this regard, HAUSP inhibitors are currently under active development in an attempt to restore p53 function in human cancer cells (Figure 2).

Collectively, and taking into account that p53 inactivation is a crucial step in the development of many types of cancers, restoring p53 function is, and has been, a hotspot for cancer drug development for some time. Different strategies are being employed to achieve this, including Ube1 inhibition to prevent Ub activation, HDM2 inhibition to block p53 polyubiquitination, and USP7/HAUSP inhibition to promote HDM2 degradation.

3.2 SCFSkp2–p27Kip1 axis

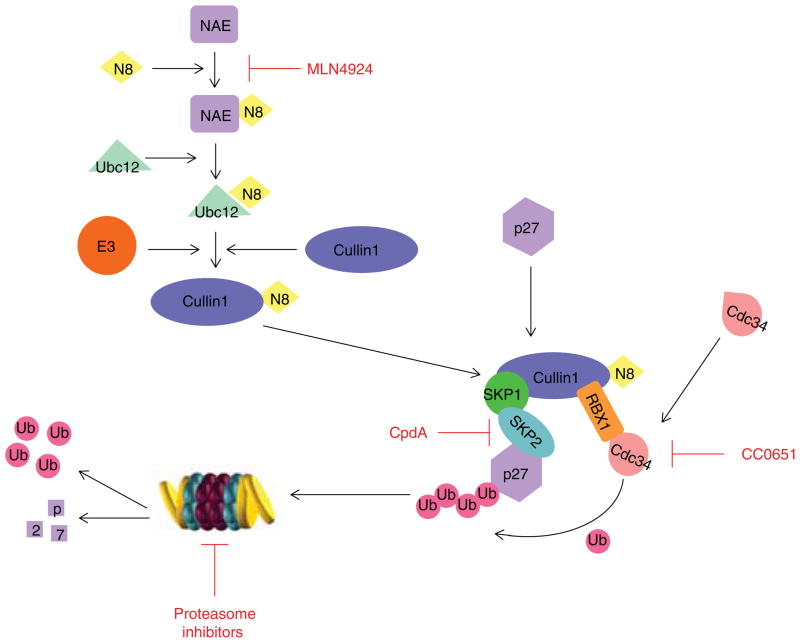

The p27Kip1 protein is a major gatekeeper of mammalian cell cycle progression that negatively regulates the action of cyclin-dependent kinases. Proteasomal degradation of p27 is required for the cellular transition from quiescence to the proliferative state. The efficient targeting of p27 for proteasomal degradation is mediated by the E3 ligase complex SCFSkp2 (Figure 3) [17].

Figure 3. Regulation of p27Kip1 stability by the ubiquitin-proteasome system.

The efficient targeting of p27 for proteasomal degradation is mediated by the E3 ligase complex SCFSkp2 in collaboration with the E2 enzyme Cdc34. The SCFSkp2 complex consists of cullin1 (the scaffold), Rbx1/Roc1 (for E2-ubiquitin conjugate recognition), Skp1 (an adaptor protein linking the F-box protein to cullin1), and Skp2 (an F-box protein required for substrate recognition). To be active, cullin1 in the SCFSkp2 complex must be covalently modified by the ubiquitin-like protein Nedd8 through a process called neddylation. Neddylation is an enzymatic cascade similar to ubiquitination where Nedd8 is activated by NAE (NEDD8 Activating Enzyme), conjugated to an E2 enzyme called UBC12, and finally transferred to the substrate cullin1. Restoration of p27 can be achieved by inhibitors of NAE, Cdc34, SCFSkp2 or the proteasome.

The SCFSkp2 complex belongs to the CRL superfamily of RING finger E3s, and this complex consists of cullin1 (the scaffold), Rbx1/Roc1 (for E2-Ub conjugate recognition), Skp1 (an adaptor protein linking the F-box protein to cullin1) and Skp2 (an F-box protein required for substrate recognition) [18]. Overexpression of Skp2 mRNA and protein levels was observed in many aggressive cancers and was commonly associated with down-regulation of p27 levels and loss of tumor differentiation [19–23].

To be active, cullin1 in the SCFSkp2 complex needs to be covalently modified by the Ub-like protein Nedd8 through a process called neddylation. Neddylation occurs through an enzymatic cascade similar to ubiquitination where Nedd8 is activated by NAE (NEDD8 Activating Enzyme), conjugated to an E2 enzyme called UBC12, and finally transferred to the substrate, cullin1 in this case (Figure 3) [24].

Cdc34 is the E2 in charge of catalyzing the K48-linked poly-Ub chain in conjunction with the CRL superfamily of RING finger E3s. High expression of Cdc34 mRNA and protein has been reported in pediatric T-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia, hepatocellular carcinoma and multiple myeloma [25].

As discussed, the restoration of p27 can be achieved by suppressing the activity of SCFSkp2 at multiple levels by inhibitors of NAE, Cdc34 or SCFSkp2 (Figure 3).

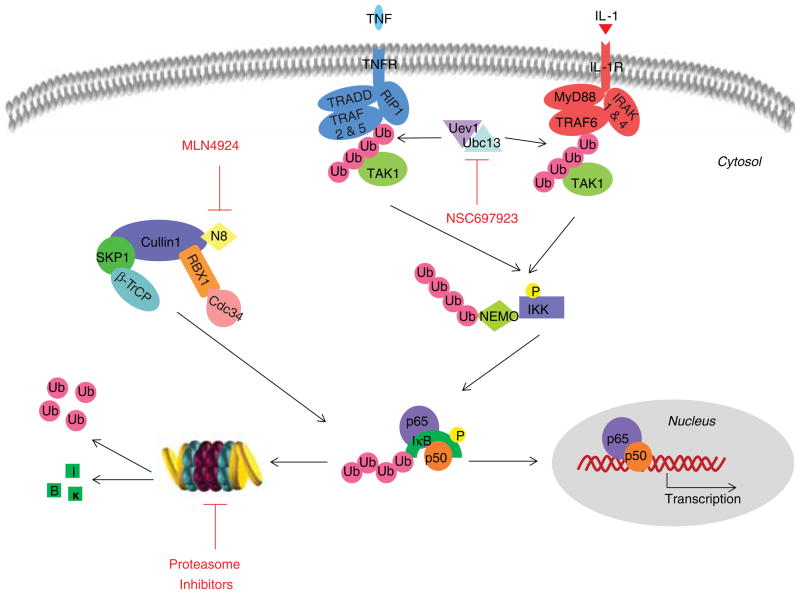

3.3 NF-κB signaling

Constitutive NF-κB activation has been observed in a wide variety of tumor types, including both solid and hematopoietic malignancies [26]. The activity of NF-κB signaling is delicately regulated at multiple levels. Under normal circumstances, the NF-κB complex is trapped in the cytoplasm by IκB (inhibitor of kappa B), preventing its translocation to the nucleus and consequent activation. On stimulation of cell surface receptors, the E3 ligase TRAF6 (TNF receptor-associated factor 6), together with the E2 enzyme Ubc13–Uev1, catalyzes the formation of K63-linked poly-Ub chains that interact with the TAK1 (TGF-β activated kinase-1) complex and promote its autophosphorylation and activation. The K63-linked poly-Ub chain also recruits the IκB kinase (IKK) complex into close proximity with TAK1, thereby facilitating the phosphorylation of IKK by TAK1. Activated IKK in turn phosphorylates IκB, which is then poly-ubiquitinated by the E3 ligase complex SCFβ-TrCP for proteasomal degradation, eventually resulting in the release and activation of NF-κB (Figure 4) [27].

Figure 4. Regulation of NF-κB activation by the ubiquitin-proteasome system.

The activity of NF-κB signaling is delicately regulated at multiple levels. Under normal circumstances, the NF-κB complex is trapped in the cytoplasm by IκB, preventing its translocation to the nucleus and subsequent activation. On stimulation of cell surface receptors, the E3 ligase TRAF6, together with the E2 enzyme Ubc13–Uev1, catalyzes the formation of K63-linked poly-ubiquitin chains that interact with the TAK1 complex and promote its autophosphorylation and activation. The K63-linked poly-ubiquitin chain also recruits the IKK complex into close proximity with TAK1, thereby facilitating the phosphorylation of IKK by TAK1. Activated IKK in turn phosphorylates IκB, which is then poly-ubiquitinated by the E3 ligase complex SCFβ-TrCP for proteasomal degradation, eventually resulting in the release and activation of NF-κB. NF-κB activation can be suppressed by inhibitors of NAE, Ubc13–Uev1A or the proteasome.

Adapted from Iwai with modifications [27].

Different strategies have been explored in order to suppress the aberrantly active NF-κB signaling pathway, including Ube1 inhibitors to inhibit Ub activation, NAE inhibitors to abolish SCFβ-TrCP activation, Ubc13–Uev1A inhibitors to decrease TRAF6 function, as well as proteasome inhibitors to prevent IκB degradation (Figure 4).

3.4 Proteasome

It is well known that many cell cycle-related proteins must be degraded by the proteasome for cell cycle progression. Because of their continuously active proliferating capacity, tumor cells are more heavily dependent on proteasomal function for the over degradation of those suppressive proteins that would otherwise halt their growth and division. Elevated proteasomal activity has been detected in many types of cancers that could be selectively targeted by inhibitors specifically designed to inhibit the enzymatic activity of β1, β2 and β5 subunits.

4. Development of small molecule inhibitors by targeting the UPS for cancer therapy

4.1 E1 inhibitors

4.1.1 Ub activating enzyme inhibitor

PYR-41 is the first cell permeable inhibitor identified to specifically inhibit Uba1 (Table 1) [28]. Circumstantial evidence suggested that PYR-41 functions by covalently modifying Uba1, perhaps on its active site cysteine. Functional studies then revealed that PYR-41 inhibits cytokine-induced NF-κB activation through inhibition of both upstream TRAF6 ubiquitination (required for its E3 ligase activity) and downstream IκB ubiquitination (required for its proteasomal degradation). PYR-41 also stabilized p53 by preventing its ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation, thereby preferentially killing transformed cells with wild-type p53 [28]. PYZD-4409 is another Uba1 inhibitor structurally related to PYR-41 [29]. PYZD-4409 induced cell death preferentially in hematologic malignant cell lines and primary patient samples over normal hematopoietic cells. Besides stabilization of p53 and cyclin D3, PYZD-4409-induced cell death was associated with induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress. The antitumor effect of PYZD-4409 was validated in a mouse leukemia model via interperitoneal injection [29].

Table 1.

A summary of small molecule inhibitors targeting E1s, E2s and E3s.

| Target | Substrate | Inhibitor | Chemical nature | Mechanism of action | Discoverer/developer | Dev. stage | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E1 | |||||||

| Uba1 | Ub | PYR-41 | Pyrazone | Inhibits the active site cysteine residue | Proof of principle | [28] | |

| NAE | Nedd8 | MLN4924 | Deazapurine | Forms Nedd8-MLN4924 adduct at NAE active site | Millennium | Phase II | [30] |

| E2 | |||||||

| Cdc34 | SCF E3 complex | CC0651 | Allosteric | Proof of principle | [33] | ||

| Ubc13–Uev1A | TRAF6 E3 | NSC697923 | Inhibits formation of Ubc13–Ub conjugate | Proof of principle | [34] | ||

| Compound Ia | Peptoid | Disrupt Ubc13–Uev1 interaction | Proof of principle | [35] | |||

| Rad6B | SMI#8, SMI#9 | Triazine | Proof of principle | [36] | |||

| E3 | |||||||

| HDM2/HDMX | p53 | Nutlin-3 RO5045337 (RG7112) & RO5503781 |

Cis-imidazoline Cis-imidazoline |

Inhibits p53 binding pocket on HDM2 | Roche | Prototype Phase I | [37] |

| MI-63, MI-219/AT-219, MI-319 | Spiro-oxindole | Ascenta | Prototype | [38,40] | |||

| MI-773 (SAR405838) | Spiro-oxindole | Sanofi | Phase I | ||||

| PXN727 & PXN822 | Isoquinolinone | Priaxon | Pre-clinical | [42] | |||

| TDP521252 & TDP665759 | Benzodiazepinedione | J & J | [43,44] | ||||

| JNJ-26854165 (serdemetan) | Tryptamine | Inhibits the binding of HDM2–p53 complex to the proteasome | J & J | Terminated | [45] | ||

| HLI98s & HLI373 | 5-Deazaflavin | Inhibits ligase activity by binding to HDM2 RING domain | Proof of principle | [46,47] | |||

| MEL23 & MEL24 | Tetrahydro- β-carboline with barbituric acid group | Inhibits ligase activity of HDM2–HDMX heterodimer | Proof of principle | [48] | |||

| SJ-172550 | Inhibits p53 binding pocket on HDMX | Proof of principle | [49] | ||||

| RO-2443 & RO-5963 | Indolyl hydantoins | Dual HDM2/HDMX antagonist | Roche | Proof of principle | [50] | ||

| SCH 900242 (MK-8242) | Merck | Phase I | |||||

| CGM097 | Novartis | Phase I | |||||

| SCFSkp2 | p27kip1, p21cip1′ |

Compound A | Interferes SKP1–Skp2 interaction | Proof of principle | [51] | ||

| p57kip2′ | C1, C2, C16, C20 | Interferes Skp2–Cks1 interface | Proof of principle | [52] | |||

| APC/C | Spindle assembly checkpoint | TAME | Prevents APC/C activation by Cdc20 and Cdh1 | Proof of principle | [53] | ||

4.1.2 NEDD8 activating enzyme inhibitor

MLN4924 is a NAE inhibitor that inhibits cullin neddylation (see Section 3.2) (Table 1). MLN4924 treatment disrupted CRL-mediated protein turnover, resulting in the accumulation of CRL substrates p27, NRF2, CDC25A, HIF1α and IκB (substrates of SCFSkp2, Cul3-ROC1, SCFFbw7, VCB-Cul2-VHL and SCFβ-TrCP, respectively) [30]. Interestingly, in most human cancer cell lines tested, with the exception of activated B cell-like (ABC) diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), MLN4924-associated cell death involves a novel mechanism of action, uncontrolled DNA synthesis during S-phase of the cell cycle, leading to DNA damage and induction of apoptosis. This mechanism suggests that actively cycling cells are more susceptible to NAE inhibition [30]. In the case of ABC-DLBCL, MLN4924-assocaited cell death involves rapid accumulation of IκB and potent suppression of NF-κB transcriptional activity [31]. MLN4924 is structurally related to AMP, a tight binding product of the NAE reaction. A follow-up study revealed that MLN4924 binds to the nucleotide-binding site of NAE and forms a covalent NEDD8-MLN4924 adduct by NAE. This adduct is a mimetic of NEDD8-AMP, but cannot be further utilized in subsequent intraenzyme reactions, resulting in the blockage of NAE function [32].

4.2 E2 inhibitors

4.2.1 Cdc34 inhibitor

CC0651 (Table 1) is an allosteric inhibitor of human Cdc34 identified through a small-molecule screen against SCFSkp2 [33]. Structural analysis has revealed that CC0651 inserts into a cryptic binding pocket on Cdc34 distant from the catalytic site, causing large-scale secondary structural rearrangement of Cdc34. This rearrangement does not affect hCdc34 interaction with E1 or E3 enzymes or the formation of the Ub thio-ester linkage, but instead interferes with the discharge of Ub to acceptor lysine residues. CC0651 and some of its analogs showed specific in vivo interaction with Cdc34, with concomitant effects on p27Kip1 accumulation and cell proliferation [33]. This pioneer study sheds light on the feasibility of selectively inhibiting Ub transfer at the E2 step.

4.2.2 Ubc13–Uev1A inhibitors

NSC697923 (Table 1) is an inhibitor of the Ubc13–Uev1A E2 enzyme identified from a screen for small-molecule compounds that may inhibit NF-κB activation in DLBCL cells [34]. Ubc13–Uev1A is involved in the formation of K63-linked poly-Ub chains that are required for IKK activation (see Section 3.3). NSC697923 specifically inhibits the formation of the Ubc13–Ub thio-ester conjugate. By inhibiting Ubc13-mediated activation of IKK, NSC697923 caused suppression of the constitutive NF-κB signaling in DLBCL cells, resulting in reduced proliferation and viability of both immortalized and primary cells [34].

Considering that both Ubc13 and UevA1 subunits are essential for K63-linked poly-Ub chain synthesis catalyzed by this E2 enzyme, an alternative strategy to inhibit the function of this E2 enzyme is to prevent the formation of the Ubc13–Uev1A heterodimer. A set of small molecules that efficiently antagonize the Ubc13–Uev1 interaction was identified by yeast two-hybrid screening combined with virtual screening [35]. These compounds inhibited K63-linked poly-ubiquitination of PCNA and TNFα-mediated activation of NF-κB and sensitized tumor cells to chemotherapeutic agents. One of these compounds significantly inhibited invasiveness, clonogenicity and tumor growth of prostate cancer cells in a mouse xenograft model [35].

4.2.3 Rad6B inhibitor

Rad6 is an E2 essential for post-replication DNA repair. Rad6B is able to ubiquitinate histones in the absence of an E3 ligase. It also mediates K63-linked poly-ubiquitination of β-catenin, which is insensitive to proteasomal degradation, thereby stabilizing it. Rad6B, along with the E3 ligase Rad18, mediates mono-ubiquitination and K63-linked poly-ubiquitination of PCNA. The Rad6B gene was found to be overexpressed in mouse and human breast cancer cell lines and tumors [36]. All of this suggests the important role of Rad6 in maintaining genomic integrity and the potential of Rad6 as an anti-cancer drug target. A set of Rad6B small molecule inhibitors was identified by Rad6B X-ray structure-based virtual screening and verified by their effect on Rab6B-mediated ubiquitination of histone H2A [36]. These compounds (including SMI#8 and SMI#9; Table 1) dock to the catalytic site of Rad6B and inhibit the formation of the Rad6B-Ub thio-ester. In cells, they inhibited Rad6B-induced histone H2A ubiquitination, downregulated intracellular β-catenin, induced G2/M arrest and apoptosis, and inhibited proliferation and migration of metastatic human breast cancer cells [36]. This study provides proof of principle for Rad6B as a druggable target for cancer therapy.

4.3 E3 inhibitors

4.3.1 HDM2–p53 inhibitors

Several series of non-peptide small molecule HDM2 antagonists have been developed to mimic the Phe19, Trp23 and Leu26 residues in p53 and their interaction with HMD2 in the well-defined deep hydrophobic pocket.

Nutlins are a series of cisimidazoline analogs identified as HDM2 antagonists, with Nutlin-3 being the most potent (Table 1) [37]. These inhibitors disrupt the interaction between HDM2 and p53 by binding to the p53 binding pocket on HDM2. Nutlin treatment resulted in accumulation of p53 and increased expression of its target gene p21, eventually leading to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in cancer cells with wild-type p53 but not in those with mutant p53 [37]. Two Nutlin derivatives, RO5045337 (RG7112) and RO5503781, are currently being evaluated in clinical studies (Table 1).

Spiro-oxindoles are a series of compounds that were discovered in a search for chemical moieties that can mimic the interaction of Trp23 with HMD2, with MI-63 being the most potent prototype drug [38,39]. MI-63 is highly effective in activating p53 and inhibiting cancer cell growth when p53 is wild-type. MI-63 has excellent specificity over cancer cells with deleted p53 and shows minimal toxicity to normal cells. Despite this, MI-63 has a poor pharmacokinetic (PK) profile and is unsuitable for in vivo evaluation. Extensive modifications of MI-63 led to the discovery of MI-219 (later called AT-219), which has a desirable PK profile [40]. Both MI-219 and its analog MI-319 produced over 500 times-higher potency than p53 peptide, the natural HDM2 binding target, in binding to HDM2 in the fluorescence polarization-based competitive binding assay [41]. The most advanced compound in this series, MI-773 (SAR405838), has now entered a clinical trial (Table 1).

PXN727 and PXN822 (Table 1) are isoquinolinone compounds developed by Priaxon AG and also bind to the p53 binding pocket on HDM2. Both are orally bioavailable and active in mouse xenografts. PXN822 is significantly more potent than its precursors [42].

TDP521252, TDP665759 and their precursor, TDP222669, are classified as benzodiazepinedione compounds identified by Johnson & Johnson as HDM2 antagonists to also mimic the α-helix of p53 and dissociate HDM2 from wild-type p53 (Table 1) [43,44].

JNJ-26854165 (serdemetan, Table 1) is another HDM2 antagonist developed by Johnson & Johnson which inhibits the binding of HDM2–p53 complex to the proteasome [45].

The HLI98 series (Table 1) are the first group of compounds reported to directly target HDM2’s Ub ligase activity. In cells, the compounds allowed for the stabilization of p53 and activation of p53-dependent transcription and apoptosis, although other p53-independent toxicity was also observed [46]. HLI373 is a derivative of HLI98s developed in an attempt to improve the potency and solubility of HLI98s [47]. HLI373 retains the 5-dimethylaminopropyla-mino side chain, but lacks the 10-aryl group. Although the HLI compound series inhibits HDM2 ligase activity in cells, it remains unclear whether this is a consequence of blocking E2–HDM2 interactions or altering the RING finger structure of HDM2.

MEL23 and MEL24 are a class of HDM2 inhibitors that were identified in a cell-based assay and found to inhibit the E3 ligase activity of the HDM2–HDMX heterodimer (Table 1) [48]. While they have some activity against HDM2 alone, MEL compounds preferentially inhibit the ligase activity of the HDM2–HDMX heterodimer. Additionally, neither was found to inhibit the formation of the HDM2–HDMX heterodimer, nor did they inhibit the formation of the p53–HDM2 complex [48].

SJ-172550 is identified as the first small molecule inhibitor of HDMX (Table 1) [49]. It reversibly binds to the p53-binding pocket of HDMX, thereby displacing p53. It was confirmed that the cell death mediated by SJ-172550 was p53-dependent. Furthermore, the effect of SJ-172550 is additive when combined with an HDM2 inhibitor, suggesting the importance of targeting both negative regulators of p53 in cancer cells [49].

RO-2443 and RO-5963 are indolyl hydantoins recently reported as the first-in-class dual HDM2/HDMX antagonists (Table 1) [50]. They potently block p53 binding with both HDM2 and HDMX by driving homo- and/or heterodimerization of HDM2 and HDMX proteins. Structural studies have revealed that the inhibitors bind into and occlude the p53 pockets of HDM2 and HDMX by inducing the formation of dimeric protein complexes kept together. This mode of action effectively stabilized p53 and activated p53 signaling in cancer cells, leading to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis. As a dual HDM2/HDMX antagonist, RO-5963 restored the p53 apoptotic activity in the presence of high levels of HDMX and may offer a more effective therapeutic modality for HDMX overexpressing cancers [50].

Aside from the above discussed HDM2–p53 inhibitors, there are two more candidates that have entered clinical trials, SCH 900242 (MK-8242) from Merck and CGM097 from Novartis (Table 1). Neither of their structures has been disclosed.

4.3.2 SCF inhibitors

The Skp2–p27 axis is an attractive target for cancer drug discovery. Compound A (CpdA) was identified in an in vitro high-throughput screen searching for compounds that could inhibit p27Kip1 ubiquitination (Table 1) [51]. It was found to specifically target SCFSkp2 by interfering with the Skp1/Skp2 interaction and thereby preventing the incorporation of Skp2 into the SCF complex. By stabilizing the SCFSkp2 substrate p27, CpdA induced G1 cell-cycle arrest as well as SCFSkp2- and p27-dependent cell killing, which was shown to be caspase-independent and occurred through activation of autophagy. In the models of multiple myeloma, CpdA overcame resistance to dexamethasone, doxorubicin and melphalan, and acted synergistically with the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib. Although further structural optimization of CpdA is needed due to its lack of potency, this compound offered the necessary grounds for targeting multisubunit E3 complexes by interfering with their protein–protein interaction [51].

Another great example of targeting SCFSkp2 complex by interfering with protein–protein interactions came from Wu et al.’s work [52]. In that study, a diverse set of small molecule inhibitors specific to SCFSkp2 activity was identified using in silico virtual ligand screening targeted to the binding interface of SCFSkp2 for p27. These compounds (such as C1, C2, C16 and C20, Table 1) selectively inhibited Skp2-mediated p27 degradation by reducing p27 binding to SCFSkp2 without affecting the stability of other Skp2 substrates. In cancer cells, the compounds induced p27 accumulation in a Skp2-dependent manner and elicited cell cycle arrest [52].

4.3.3 APC/C inhibitors

Tosyl-L-arginine methyl ester (TAME) was initially identified as an inhibitor of cyclin proteolysis in mitotic Xenopus egg extract (Table 1). Sometime later, the E3 ligase APC/C was found to be the target of TAME [53]. TAME binds to APC/C and prevents its activation by the Cdh1 and Cdc20 activator proteins. Treatment of cells with the cell-permeable prodrug of TAME caused a robust mitotic arrest in metaphase without perturbing the spindle. TAME was more effective in promoting mitotic arrest and inducing apoptosis than microtubule inhibitors, such as taxanes and the vinca alkaloids, which induce mitotic arrest by activating the spindle assembly checkpoint and consequently inhibiting the APC/C, as TAME provides a specific and direct inhibition of APC/C [53].

4.4 20S proteasome inhibitors

A wide range of proteasome inhibitors has been developed during the past decade, including peptide boronates (e.g., botezomib, delanzomib and MLN9708), peptide epoxyke-tones (e.g., carfilzomib, oprozomib, ONX-0914 and PR-924), peptide aldehydes (e.g., MG132 and IPSI-001), and non-peptidic β-lactones (e.g., marizomib) [54–56].

4.4.1 Bortezomib and other peptide boronates

Bortezomib (PS341, Velcade®) (Table 2) is the first proteasome inhibitor to enter clinical use. As a peptide boronate, it forms tetrahedral adducts with the N-terminal Thr1 of the catalytic β subunits of the proteasome, which are further stabilized by two extra hydrogen bonds. Therefore, although bortezomib is a reversible inhibitor, the dissociation rate is very slow [57,58].

Table 2.

A summary of small molecule inhibitors targeting 20S core proteasome and immunoproteasome.

| Targets | Inhibitors | Chemical nature | Mechanism of action | Developer | Dev. stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 20S Core | Bortezomib (PS341) | Boronate | β5 > β1 | Millennium | FDA approved |

| MLN-9708 | Boronate | β5 > β1 | Millennium | Phase I – II | |

| Delanzomib (CEP-18770) | Boronate | β5 > β1 | Cephalon | Phase I – II | |

| Carfizomib (PR-171) | Epoxyketone | β5, β5i | ONXY | FDA approved | |

| Oprozomib (ONX-0912) | Epoxyketone | β5, β5i | ONXY | Phase I – II | |

| Marizomib (NPI-0052) | β-lactone | β5 > β2 > β1 | Nereus | Phase I | |

| Immunoproteasome | ONX-0914 (PR-957) | Boronate | β5i | ONXY | Pre-clinical |

| PR-924 | Boronate | β5i | |||

| IPSI-001 | Aldehyde | β5i, β1i |

Treatment with bortezomib results in stabilization of two important negative regulators of the cell cycle, p27KIP1 and p53 [59,60], both of which are known proteasome substrates [61,62]. Inhibition of proteasomal activity by bortezomib also suppresses NF-κB signaling by preventing IκB degradation and the generation of NF-κB subunits p50 and p52 from their precursors, p105 and p100, respectively [63,64]. Bortezomib treatment also accumulates the pro-apoptotic protein Bax, thereby shifting the pro- and anti-apoptosis balance towards apoptosis [64,65]. Additionally, proteasome inhibition has been shown to induce endoplasmic reticulum stress and oxidative stress in cancer cells [66].

Occurrence of bortezomib resistance is one of the major driving forces for the development of second-generation proteasome inhibitors [67]. The results from cell-based studies suggest that the mechanisms mediating bortezomib resistance include increased mRNA and protein expression of the proteasomal β5 subunit, mutations in the β5 subunits that impair bortezomib binding, upregulation of the endoplasmic reticulum chaperone protein GRP78, upregulation of multidrug transporter P-glycoprotein, as well as constitutive activation of NF-κB signaling [68–73].

MLN9708 and delanzomib (CEP-18770) are two peptide boronate-based second-generation proteasome inhibitors (Table 2). MLN9708 is sophisticatedly designed as a prodrug in the form of a boronic ester so that it is orally bioavailable [57,58]. Delanzomib is also orally bioavailable which has shown proteasome-inhibitory activity similar to that of bortezomib in hematologic and solid tumor cell lines, as well as in primary cells from multiple myeloma patients [74].

4.4.2 Carfilzomib and other peptide epoxyketones

Carfilzomib (PR-171, Kyprolis®) is the second proteasome inhibitor approved by the FDA (Table 2). It belongs to the peptide epoxyketone class of proteaome inhibitors. This class represents the most specific and potent proteasome inhibitors discovered thus far. The α,β-epoxyketone moiety interacts with both the hydroxyl group and the free α-amino group of Thr1 in the catalytic β subunits of the proteasome, leading to the formation of the morpholino adduct in an irreversible way [57,58]. This gives epoxyketone-based proteasome inhibitors greater potency as new protein synthesis and proteasome assembly are required for recovery of proteasome activity. Additionally, because the free α-amino group required for adduct formation is not present in serine and cysteine proteases, these proteases are not affected by epoxyketones, which confers epoxyketones the specificity towards proteasome. Carfilzomib has been shown to be more specific than borzetomib, with little or no off-target activity outside of the proteasome [75]. In addition to targeting the β5 subunit in the constitutive proteasome, carfilzomib also targets the correlated β5i subunit in the immunoproteasome, which appears to be preferentially expressed in multiple myeloma [76].

Oprozomib (ONX-0912 or PR-047) is another peptide epoxyketone-based proteasome inhibitor (Table 2) that showed similar potency to carfilzomib in cytotoxicity assays. More importantly, it is orally bioavailable; orally administered oprozomib showed equivalent antitumor activity to intravenously administered carfilzomib in human tumor xenograft and mouse syngeneic models [77].

ONX-0914 and PR-924 are peptide epoxyketone-based immunoproteasome inhibitors (Table 2), both of which are able to selectively and irreversibly inhibit the β5i subunit. ONX-0914 is 20–40-fold more selective towards the β5i subunit than both the β5 and β1i subunits [78].

4.4.3 Other 20S proteasome inhibitors

Marizomib (salinosporamide A, NPI-0052) is a proteasome inhibitor with a β-lactone backbone (Table 2). The carbonyl group of the β-lactone can interact with the hydroxyl group of Thr1 in catalytic β subunits, leading to the formation of an acylester adduct. Although this is a reversible process, the dissociation rate of the covalent adduct is extremely slow. In addition to the acylester bond, marizomib also forms a cyclic tetrahydrofuran ring with the proteasome, making the reaction irreversible [57,79].

MG132 and IPSI-001 are peptide aldehyde-based protea-some inhibitors (Table 2). This class of compounds inhibits the proteasome by forming a covalent hemiacetal bond with the hydroxyl group of the N-terminal threonine (Thr1) in the catalytic β subunits. This inhibition is reversible and the dissociation rate is relatively fast. MG132 (A-LLL-al) was among the first proteasome inhibitors developed. Although it is a potent proteasome inhibitor, the fact that MG132 is rapidly oxidized into inactive carbonic acid in vivo largely prevented its therapeutic development [56–58].

IPSI-001 is an immunoproteasome inhibitor that selectively inhibits the β5i and β1i subunits, potently suppressing proliferation and inducing apoptosis in MM cell lines as well as in patient samples. More importantly, it was able to overcome conventional and novel drug resistance, including resistance to bortezomib [80].

Besides the above-discussed peptidic proteasome inhibitors, a growing group of natural dietary or medicinal products have been found to possess proteasome-inhibitory activity, including epigallocatechin-3-gallate (EGCG), celastrol and curcumin [81–83]. It must be kept in mind that natural products tend to have multiple cellular targets with the proteasome being only one of them. EGCG is a flavonoid which can irreversibly inhibit the proteasomal β5 subunit through covalent binding [81]. Notably, EGCG is able to interact with not only the β5 subunit of the constitutive proteasome but also the β5i subunit of the immunoproteasome with an even greater affinity [84].

Additionally, some natural cyclic peptides have been found to reversibly inhibit proteasome function in a non-covalent manner. These compounds include TMC-95A, a cyclic tri-peptide and argyrin A, a cyclic octapeptide. Both are able to inhibit proteasomal activity in the low nanomolar range [85,86]. The shortcoming for the development of these cyclic peptides, however, is that their de novo synthesis is quite difficult and expensive.

4.5 19S Proteasome inhibitors

4.5.1 Proteasome recognition inhibitors

Ubistatin A and ubistatin B are two small molecules that disrupt substrate recognition by the 19S regulatory particle of the proteasome (Table 3) [87]. They were identified in a chemical genetic screen in Xenopus extracts for small molecules that inhibit cell cycle machinery. Ubistatins blocked the binding of ubiquitinated substrates to the proteasome by targeting the Ub–Ub interface of K48-linked chains, the same interface recognized by Ub-chain receptors of the proteasome [87]. These compounds supported the idea that the Ub chain itself could be another potential target for pharmacological intervention in the Ub–proteasome pathway.

Table 3.

A summary of small molecule inhibitors targeting 19S regulatory particle of the proteasome and the DUBs.

| Targets | Biological effects | Inhibitors | Refs. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ub–Ub interface | Substrate recognition by the 19S regulatory particle | Ubistatins | [87] |

| USP14 and UCH-L5/UCH37 | Proteasome-associated DUB, antagonize substrate degradation | b-AP15 | [88] |

| USP7/HAUSP | Deubiquitinates p53 and Hdm2, redistributes | P5091 | [89] |

| PTEN subcellular localization | P22077 | [90] | |

| HBX19818 | [91] | ||

| Multiple DUBs including USP9x, USP5, USP14, and UCH-L5/UCH37 | Regulate survival protein stability and 26S proteasome function | WP-1130 | [92] |

4.5.2 USP14 and UCH-L5/UCH37 inhibitors

b-AP15 (Table 3) was identified in a screen for compounds that induce the lysosomal apoptosis pathway [88]. It was found to reversibly inhibit the activity of UCH37 and USP14. Inhibition of both UCH37 and USP14 by b-AP15 resulted in blockage of cleavage of K48-linked Ub chains and accumulation of poly-ubiquitinated proteins. Consistent with the accumulation of cell-cycle inhibitors such as CDKN1A, CDKN1B and p53, b-AP15 treatment induced G2/M arrest without causing genotoxicity. Treatment with b-AP15 inhibited tumor progression in four different in vivo solid tumor models and inhibited organ infiltration in an acute myeloid leukemia model. More importantly, the cellular response to b-AP15 is distinct from that of bortezomib not only with regard to the involvement of apoptosis regulators, but also the differential sensitivity of the NCI-60 tumor cell line panel. b-AP15 induced apoptosis in tumor cells with mutant p53 or overexpressed Bcl-2, two characteristics that greatly affect bortezomib sensitivity. Therefore, b-AP15 not only provides experimental evidence that proteasome-associated DUBs represent a new category of anticancer drug targets, but also indicates that this class of inhibitors could have great therapeutic potential as they seem to exhibit a different therapeutic spectrum than 20S proteasome inhibitors [88].

4.6 DUB inhibitors

The development of DUB inhibitors is much more recent than that of proteasome and E3 ligase inhibitors. To our knowledge, no DUB inhibitors have entered clinical trials yet. Besides the proteasome-associated DUB inhibitors discussed above, USP7/HAUSP inhibitors are the most studied due to its role in restoring p53 function.

4.6.1 USP7/HAUSP inhibitors

P5091 (Table 3) was discovered using an Ub-phospholipase A2 enzyme (Ub-PLA2) reporter assay in a high-throughput screen for inhibitors of USP7 [89]. P5091 actively inhibits USP7 at concentrations as low as 5 – 10 μM in the cellular environment, resulting in HDM2 poly-ubiquitination and accelerated degradation by the proteasome, and consequently increased steady-state protein levels of p53 and p21. More importantly, studies in multiple myeloma cells revealed that P5091 was able to overcome bortezomib-resistance and inhibit bone marrow stromal cell-induced growth of these cells. It was well tolerated, inhibited tumor growth and angiogenesis, triggered apoptosis and prolonged survival in mouse models. Furthermore, combined treatment of P5091 and lenalidomide, dexamethasone, or the HDAC inhibitor vorinostat (SAHA) induced synergistic antimultiple myeloma activity in vitro [89].

P22077 (Table 3) is an analog of P5091. The best selectivity of P22077 was observed when cells were treated with 20 μM P22077. In addition to the altered levels of HDM2, p53 and p21 associated with its use, P22077 treatment also caused reduced levels of DNA damage proteins DDB1, RBX1, DCAF7 and DCAF11, all of which are subunits of E3 ligases, indicating a previously unknown functional link between USP7 and enzymes involved in DNA repair [90].

HBX19818 (Table 3) is a recently identified USP7 inhibitor which selectively inhibits USP7 activity with an IC50 of 28.1 μM [91]. It irreversibly binds to USP7 through nucleophilic attack of its catalytic site, resulting in chloride release and the formation of a covalent bond with the Cys223 located on the USP7 active site. In tumor cells, HBX19818 treatment recapitulated the USP7 knockdown phenotype that leads to G1 arrest. Despite the accumulation of functionally active p53 in p53 wild-type cells, the observation that cell viability was affected by HBX19818 at a similar level regardless of the p53 status suggests the involvement of mechanisms other than upregulation of p53 in the cellular response [91].

4.6.2 Partially selective DUB inhibitor

WP1130 (Table 3) was initially identified as a Jak2 kinase inhibitor. However, WP1130 did not directly inhibit Jak2 kinase activity. Instead, it was found to be a partially selective DUB inhibitor, directly inhibiting DUB activity of USP9x, USP5, USP14 and UCH37, which are known to regulate survival protein stability and 26S proteasome function [92]. In cell culture treated models, WP1130 induced a rapid and marked accumulation of poly-ubiquitinated (K48-and K63-linked) proteins into juxtanuclear aggresomes without affecting 20S proteasomal activity. WP1130-mediated inhibition of tumor-activated DUBs also results in the downregulation of antiapoptotic proteins and upregulation of proapoptotic proteins, such as MCL-1 and p53, respectively [92]. The anti-proliferative and apoptotic effects of WP1130 have been validated in various tumor models including chronic myelogenous leukemia, melanoma and mantle cell lymphoma [93–95].

5. Conclusions

The UPS plays an important role in cancer cell survival (i.e., evasion of apoptosis) and proliferation by destroying negative cell-cycle regulators p27 and p53 and promoting the activation of NF-κB signaling. The successful application of proteasome inhibitors bortezomib and carfilzomib in the treatment of multiple myeloma patients has paved the way for targeting the UPS as a feasible and effective way to treat cancer. Immunoproteasome inhibitors are under active development in the hope of providing more targeted therapies in the treatment of hematological malignancies. With the tremendous effort that has been made in the past decade, two more classes of inhibitors targeting NAE and HMD2 are now on their way to help in the fight against cancer. Although DUB inhibitors are much less studied compared to E3 ligase and proteasome inhibitors, one of them, a USP7 inhibitor, is now drawing more and more attention and is currently under active pre-clinical development. Along this line, several other previously less popular targets, such as Cdc34, Ubc13–Uev1A and the SCF complex, are now being studied by several groups. Considering the complexity of the UPS and the diversity of E3s and DUBs, making continuous efforts to better understand these components is necessary to lead in the identification of novel therapeutic targets.

6. Expert opinions

6.1 Identification and validation of new drug targets in the UPS

Much emphasis has been placed on the identification of specific and targeted molecular therapy for the treatment of many cancer types. To establish a new targeted therapy, at least two criteria have to be met: a validated therapeutic target, and a highly specific inhibitor (or activator) towards that target. In the UPS, a few targets have been well-established and validated, including NAE, HDM2 and the proteasomal β1, β2 and β5 subunits. Identification of new molecular targets requires continual deciphering of the encrypted Ub code. One should keep in mind that although the UPS is ubiquitously present in all cell types, the identification of a novel therapeutic target within this system could still prove to be tumor type-specific or at least superior in one tumor type over another. For example, the current clinical application of pro-teasome inhibitors is still limited to multiple myeloma and lymphomas with limited success in solid tumors.

Compared to the proteasome, targeting E3 ligases is thought to be a more specific approach in the manipulation of this pathway as it only affects a small subset of very defined proteins. However, because of their known functional redundancy, inhibiting one E3 ligase might not be sufficient to prevent degradation of the protein substrate of interest. For example, two distinct E3 ligases, the nuclear ligase SCFSkp2 and the cytoplasmic ligase KPC (Kip1 ubiquitination-promoting complex), are both involved in the ubiquitination and proteasomal degradation of p27 [96].

6.2 Development of small-molecule inhibitors of UPS

The development of small-molecule inhibitors has been considerably accelerated due to the establishment of various cell-free and cell-based high-throughput screening (HTS) assays. The establishment of such HTS assays, however, is contingent on our knowledge regarding the ultimate target (s) of interest. For example, the proteasomal activity assay was established based on the characterization of peptide sequences specifically degraded by β1, β2 or β5 subunits. Additionally, characterization of the crystal structure of interested enzymes, for example, the proteasomal β5 subunit, has largely facilitated computer-assisted drug design and optimization. Therefore, a better understanding of all the players in the UPS not only helps target validation but also assists in inhibitor development.

According to the mechanisms of action, small-molecule inhibitors targeting the UPS generally fall into three different classes. The largest such group includes those inhibitors that directly bind to the enzyme active site and inhibit its activity. The second group is made up of those that ultimately interfere with protein–protein interactions, preventing their binding. The third group being the allosteric inhibitors, whose use results in protein conformational changes. Interference with protein–protein interaction was once considered impracticable; accumulated knowledge in regards to protein–protein interfaces has led to the development of several inhibitors that either prevents the enzyme–substrate interaction or the formation of an E3 ligase complex. This again reinstates the importance of understanding the biochemical and biological properties of protein targets of interest for the development of small-molecule inhibitors.

Although two FDA-approved proteasome inhibitors entered clinical use, neither is orally available. Therefore, one of the directions of the development of proteasome inhibitors is the development of oral proteasome inhibitors. Oral administration is not only convenient but also seems to produce milder side effects.

One of the biggest challenges in the development of DUB inhibitors lies in the fact that most DUBs are cysteine pro-teases, a group of proteases very difficult to target when compared to other types. Cysteine protease inhibitors generally lack specificity and bioavailability, and are metabolically unstable. Additionally, the irreversible inhibitors capable of alkylating the active site cysteine in those enzymes are generally reactive to all other thiols as well. Moreover, compared to E3 ligase and proteasome inhibitors, the mechanisms by which DUB inhibitors interact with their corresponding DUBs are much less defined.

6.3 Exploring potential drug combinations for UPS inhibition

While bortezomib has been successfully used to treat multiple myeloma patients, drug resistance remains an emerging problem. In an effort to overcome borzetomib resistance, combinations of two drugs targeting different components of the UPS have been tested. For example, it has been reported that the SCF inhibitor, CpdA, and bortezomib were synergistically effective in bortezomib-resistant multiple myeloma cell lines [51]. Moreover, the USP7/HAUSP inhibitor P5091 was also reported to be capable of overcoming bortezomib-resistance in multiple myeloma cells and inhibiting bone marrow stromal cell-induced growth of these cells [89]. In addition, encouraging in this regard is a study where the blockade of the E2 enzyme Cdc34, using a dominant-negative strategy, was found to enhance the antimyeloma activity of bortezomib [25]. With the recent discovery of Cdc34 inhibitors, one would expect that the Cdc34 inhibitors work collaboratively with bortezomib.

Although bortezomib treatment suppresses NF-κB activation, constitutive NF-κB activity was found to be one of the mechanisms mediating bortezomib resistance. In order to better inhibit NF-κB signaling, some combinations are worth trying, such as an NAE inhibitor in combination with bortezomib, or an Ubc13–Uev1A inhibitor in combination with bortezomib.

Article highlights.

The UPS is extensively involved in different aspects of cancer development and progression, such as dysregulated cell growth and resistance to apoptosis, making it a source of valuable molecular targets for anti-cancer drugs.

The UPS regulates the turnover of p53 and p27Kip1 as well as the activation of NF-κB signaling, thereby supporting cancer cell survival and proliferation.

A wide range of proteasome inhibitors has been developed, including peptide boronates (e.g., botezomib, delanzomib and MLN9708), peptide epoxyketones (e.g., carfilzomib, oprozomib, ONX-0914 and PR-924), peptide aldehydes (e.g., MG132 and IPSI-001), non-peptidic β-lactones (e.g., Marizomib) and some natural products, among which bortezomib and carfilzomib are now used in the clinic.

HDM2 inhibitors are being actively developed in hopes of restoring cellular p53 function. Those inhibitors either inhibit the p53-binding pocket on HDM2 or inhibit the E3 ligase activity of HDM2. Several HDM2 inhibitors have successfully entered clinical trials.

NAE activity is required for activation of cullin, a component of the Cullin-RING E3 ligases. MLN4924 is a NAE inhibitor developed to disrupt Cullin-RING E3 ligase-mediated protein turnover. It is currently being evaluated in clinical trials.

Although no DUB inhibitors have yet entered clinical trials, several inhibitors of USP7/HAUSP and proteasome-associated DUBs do exist and have shown appreciable therapeutic potential in pre-clinical studies.

This box summarizes key points contained in the article

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by the National Cancer Institute grants (1R01CA20009, 3R01CA120009–04S1 and 5R01CA127258–05) to QP Dou.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

The authors state no conflict of interest and have received no payment in preparation of this manuscript.

Bibliography

Papers of special note have been highlighted as either of interest

(•) or of considerable interest

(••) to readers.

- 1.Lee DH, Goldberg AL. Proteasome inhibitors: valuable new tools for cell biologists. Trends Cell Biol. 1998;8:397–403. doi: 10.1016/s0962-8924(98)01346-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jin J, Li X, Gygi SP, Harper JW. Dual E1 activation systems for ubiquitin differentially regulate E2 enzyme charging. Nature. 2007;447:1135–8. doi: 10.1038/nature05902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.van Wijk SJ, Timmers HT. The family of ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (E2s): deciding between life and death of proteins. FASEB J. 2010;24:981–93. doi: 10.1096/fj.09-136259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Metzger MB, Hristova VA, Weissman AM. HECT and RING finger families of E3 ubiquitin ligases at a glance. J Cell Sci. 2012;125:531–7. doi: 10.1242/jcs.091777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Matsumoto ML, Wickliffe KE, Dong KC, et al. K11-linked polyubiquitination in cell cycle control revealed by a K11 linkage-specific antibody. Mol Cell. 2010;39:477–84. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6•.Komander D, Rape M. The ubiquitin code. Annu Rev Biochem. 2012;81:203–29. doi: 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060310-170328. A comprehensive review describing all aspects of the ubiquitin chains and linkage specificity. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7••.Glickman MH, Ciechanover A. The ubiquitin-proteasome proteolytic pathway: destruction for the sake of construction. Physiol Rev. 2002;82:373–428. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00027.2001. One of the most comprehensive reviews regarding the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goldberg AL, Akopian TN, Kisselev AF, et al. New insights into the mechanisms and importance of the proteasome in intracellular protein degradation. Biol Chem. 1997;378:131–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gallastegui N, Groll M. The 26S proteasome: assembly and function of a destructive machine. Trends Biochem Sci. 2010;35:634–42. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Strehl B, Seifert U, Kruger E, et al. Interferon-gamma, the functional plasticity of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, and MHC class I antigen processing. Immunol Rev. 2005;207:19–30. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2005.00308.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Angeles A, Fung G, Luo H. Immune and non-immune functions of the immunoproteasome. Front Biosci. 2012;17:1904–16. doi: 10.2741/4027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fraile JM, Quesada V, Rodriguez D, et al. Deubiquitinases in cancer: new functions and therapeutic options. Oncogene. 2012;31:2373–88. doi: 10.1038/onc.2011.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown CJ, Lain S, Verma CS, et al. Awakening guardian angels: drugging the p53 pathway. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9:862–73. doi: 10.1038/nrc2763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moll UM, Petrenko O. The MDM2-p53 interaction. Mol Cancer Res. 2003;1:1001–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15••.Kussie PH, Gorina S, Marechal V, et al. Structure of the MDM2 oncoprotein bound to the p53 tumor suppressor transactivation domain. Science. 1996;274:948–53. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5289.948. Crystallography study revealing the MDM2-p53 interface. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hu M, Gu L, Li M, et al. Structural basis of competitive recognition of p53 and MDM2 by HAUSP/USP7: implications for the regulation of the p53-MDM2 pathway. PLoS Biol. 2006;4:e27. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bloom J, Pagano M. Deregulated degradation of the cdk inhibitor p27 and malignant transformation. Semin Cancer Biol. 2003;13:41–7. doi: 10.1016/s1044-579x(02)00098-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zheng N, Schulman BA, Song L, et al. Structure of the Cul1-Rbx1-Skp1-F boxSkp2 SCF ubiquitin ligase complex. Nature. 2002;416:703–9. doi: 10.1038/416703a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kudo Y, Kitajima S, Sato S, et al. High expression of S-phase kinase-interacting protein 2, human F-box protein, correlates with poor prognosis in oral squamous cell carcinomas. Cancer Res. 2001;61:7044–7. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gstaiger M, Jordan R, Lim M, et al. Skp2 is oncogenic and overexpressed in human cancers. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2001;98:5043–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.081474898. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hershko D, Bornstein G, Ben-Izhak O, et al. Inverse relation between levels of p27(Kip1) and of its ubiquitin ligase subunit Skp2 in colorectal carcinomas. Cancer. 2001;91:1745–51. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20010501)91:9<1745::aid-cncr1193>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masuda TA, Inoue H, Sonoda H, et al. Clinical and biological significance of S-phase kinase-associated protein 2 (Skp2) gene expression in gastric carcinoma: modulation of malignant phenotype by Skp2 overexpression, possibly via p27 proteolysis. Cancer Res. 2002;62:3819–25. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chiarle R, Fan Y, Piva R, et al. S-phase kinase-associated protein 2 expression in non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma inversely correlates with p27 expression and defines cells in S phase. Am J Pathol. 2002;160:1457–66. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)62571-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Merlet J, Burger J, Gomes JE, Pintard L. Regulation of cullin-RING E3 ubiquitin-ligases by neddylation and dimerization. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:1924–38. doi: 10.1007/s00018-009-8712-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chauhan D, Li G, Hideshima T, et al. Blockade of ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme CDC34 enhances anti-myeloma activity of Bortezomib/Proteasome inhibitor PS-341. Oncogene. 2004;23:3597–602. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Prasad S, Ravindran J, Aggarwal BB. NF-kappaB and cancer: how intimate is this relationship. Mol Cell Biochem. 2010;336:25–37. doi: 10.1007/s11010-009-0267-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27•.Iwai K. Diverse ubiquitin signaling in NF-kappaB activation. Trends Cell Biol. 2012;22:355–64. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2012.04.001. Excellent review regarding the regulation of NF-kappaB activation by diverse ubiquitin signals. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Yang Y, Kitagaki J, Dai RM, et al. Inhibitors of ubiquitin-activating enzyme (E1), a new class of potential cancer therapeutics. Cancer Res. 2007;67:9472–81. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-0568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu GW, Ali M, Wood TE, et al. The ubiquitin-activating enzyme E1 as a therapeutic target for the treatment of leukemia and multiple myeloma. Blood. 2010;115:2251–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-07-231191. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30••.Soucy TA, Smith PG, Milhollen MA, et al. An inhibitor of NEDD8-activating enzyme as a new approach to treat cancer. Nature. 2009;458:732–6. doi: 10.1038/nature07884. Identification of MLN4924 as the inhibitor of never-before-targeted NEDD8-activating enzyme with anti-tumor activity in human tumor xenograft mouse model. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Milhollen MA, Traore T, Adams-Duffy J, et al. MLN4924, a NEDD8-activating enzyme inhibitor, is active in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma models: rationale for treatment of NF-{kappa}B-dependent lymphoma. Blood. 2010;116:1515–23. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-03-272567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brownell JE, Sintchak MD, Gavin JM, et al. Substrate-assisted inhibition of ubiquitin-like protein-activating enzymes: the NEDD8 E1 inhibitor MLN4924 forms a NEDD8-AMP mimetic in situ. Mol Cell. 2010;37:102–11. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2009.12.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33••.Ceccarelli DF, Tang X, Pelletier B, et al. An allosteric inhibitor of the human Cdc34 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme. Cell. 2011;145:1075–87. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.05.039. Identification of the first inhibitor of an E2 enzyme, which is Cdc34, raising the possibility of selectively inhibit ubiquitin transfer at the central step in the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pulvino M, Liang Y, Oleksyn D, et al. Inhibition of proliferation and survival of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma cells by a small-molecule inhibitor of the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Ubc13-Uev1A. Blood. 2012;120:1668–77. doi: 10.1182/blood-2012-02-406074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Scheper J, Guerra-Rebollo M, Sanclimens G, et al. Protein-protein interaction antagonists as novel inhibitors of non-canonical polyubiquitylation. PLoS One. 2010;5:e11403. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0011403. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sanders MA, Brahemi G, Nangia-Makker P, et al. Novel inhibitors of rad6 ubiquitin conjugating enzyme: design, synthesis, identification, and functional characterization. Mol Cancer Ther. 2013;12:373–83. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-12-0793. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37••.Vassilev LT, Vu BT, Graves B, et al. In vivo activation of the p53 pathway by small-molecule antagonists of MDM2. Science. 2004;303:844–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1092472. Identification of nutlins as potent and selective small-molecule inhibitors of MDM2 with anti-tumor activity in human tumor xenograft mouse model. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ding K, Lu Y, Nikolovska-Coleska Z, et al. Structure-based design of spiro-oxindoles as potent, specific small-molecule inhibitors of the MDM2-p53 interaction. J Med Chem. 2006;49:3432–5. doi: 10.1021/jm051122a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ding K, Lu Y, Nikolovska-Coleska Z, et al. Structure-based design of potent non-peptide MDM2 inhibitors. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:10130–1. doi: 10.1021/ja051147z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Shangary S, Qin D, McEachern D, et al. Temporal activation of p53 by a specific MDM2 inhibitor is selectively toxic to tumors and leads to complete tumor growth inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:3933–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0708917105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mohammad RM, Wu J, Azmi AS, et al. An MDM2 antagonist (MI-319) restores p53 functions and increases the life span of orally treated follicular lymphoma bearing animals. Mol Cancer. 2009;8:115. doi: 10.1186/1476-4598-8-115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cheok CF, Verma CS, Baselga J, Lane DP. Translating p53 into the clinic. Nat Rev Clin Oncol. 2011;8:25–37. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2010.174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Koblish HK, Zhao S, Franks CF, et al. Benzodiazepinedione inhibitors of the Hdm2:p53 complex suppress human tumor cell proliferation in vitro and sensitize tumors to doxorubicin in vivo. Mol Cancer Ther. 2006;5:160–9. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-05-0199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grasberger BL, Lu T, Schubert C, et al. Discovery and cocrystal structure of benzodiazepinedione HDM2 antagonists that activate p53 in cells. J Med Chem. 2005;48:909–12. doi: 10.1021/jm049137g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wade M, Li YC, Wahl GM. MDM2, MDMX and p53 in oncogenesis and cancer therapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:83–96. doi: 10.1038/nrc3430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang Y, Ludwig RL, Jensen JP, et al. Small molecule inhibitors of HDM2 ubiquitin ligase activity stabilize and activate p53 in cells. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:547–59. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kitagaki J, Agama KK, Pommier Y, et al. Targeting tumor cells expressing p53 with a water-soluble inhibitor of Hdm2. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008;7:2445–54. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-08-0063. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Herman AG, Hayano M, Poyurovsky MV, et al. Discovery of Mdm2-MdmX E3 ligase inhibitors using a cell-based ubiquitination assay. Cancer Discov. 2011;1:312–25. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Reed D, Shen Y, Shelat AA, et al. Identification and characterization of the first small molecule inhibitor of MDMX. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:10786–96. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.056747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Graves B, Thompson T, Xia M, et al. Activation of the p53 pathway by small-molecule-induced MDM2 and MDMX dimerization. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:11788–93. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1203789109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Chen Q, Xie W, Kuhn DJ, et al. Targeting the p27 E3 ligase SCF(Skp2) results in p27- and Skp2-mediated cell-cycle arrest and activation of autophagy. Blood. 2008;111:4690–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-112904. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wu L, Grigoryan AV, Li Y, et al. Specific small molecule inhibitors of Skp2-mediated p27 degradation. Chem Biol. 2012;19:1515–24. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.09.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Zeng X, Sigoillot F, Gaur S, et al. Pharmacologic inhibition of the anaphase-promoting complex induces a spindle checkpoint-dependent mitotic arrest in the absence of spindle damage. Cancer Cell. 2010;18:382–95. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2010.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Buac D, Shen M, Schmitt S, et al. From bortezomib to other inhibitors of the proteasome and beyond. Curr Pharm Des. 2013;19(22):4025–38. doi: 10.2174/1381612811319220012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shen M, Dou QP. Proteasome inhibition as a novel strategy for cancer treatment. In: Johnson DE, editor. Cell death signaling in cancer biology and treatment. Springer; New York: 2013. pp. 303–29. [Google Scholar]

- 56•.de Bettignies G, Coux O. Proteasome inhibitors: dozens of molecules and still counting. Biochimie. 2010;92:1530–45. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2010.06.023. Comprehensive reviews about proteasome inhibitors. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57•.Kisselev AF, van der Linden WA, Overkleeft HS. Proteasome inhibitors: an expanding army attacking a unique target. Chem Biol. 2012;19:99–115. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.01.003. Comprehensive reviews about proteasome inhibitors. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58•.Borissenko L, Groll M. 20S proteasome and its inhibitors: crystallographic knowledge for drug development. Chem Rev. 2007;107:687–717. doi: 10.1021/cr0502504. Comprehensive reviews about proteasome inhibitors. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59•.Hideshima T, Mitsiades C, Akiyama M, et al. Molecular mechanisms mediating antimyeloma activity of proteasome inhibitor PS-341. Blood. 2003;101:1530–4. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-08-2543. Identification of the molecular mechanisms of bortezomib in multiple myeloma cells. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Hideshima T, Richardson P, Chauhan D, et al. The proteasome inhibitor PS-341 inhibits growth, induces apoptosis, and overcomes drug resistance in human multiple myeloma cells. Cancer Res. 2001;61:3071–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61••.Pagano M, Tam SW, Theodoras AM, et al. Role of the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway in regulating abundance of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p27. Science. 1995;269:682–5. doi: 10.1126/science.7624798. The original study showing the regulation of p27 by the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shkedy D, Gonen H, Bercovich B, Ciechanover A. Complete reconstitution of conjugation and subsequent degradation of the tumor suppressor protein p53 by purified components of the ubiquitin proteolytic system. FEBS Lett. 1994;348:126–30. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)00582-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Magnani M, Crinelli R, Bianchi M, Antonelli A. The ubiquitin-dependent proteolytic system and other potential targets for the modulation of nuclear factor-kB (NF-kB) Curr Drug Targets. 2000;1:387–99. doi: 10.2174/1389450003349056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64•.Mitsiades N, Mitsiades CS, Poulaki V, et al. Molecular sequelae of proteasome inhibition in human multiple myeloma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:14374–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.202445099. Characterization of the gene expression profiles in bortezomib-treated multiple myeloma cells. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pigneux A, Mahon FX, Moreau-Gaudry F, et al. Proteasome inhibition specifically sensitizes leukemic cells to anthracyclin-induced apoptosis through the accumulation of Bim and Bax pro-apoptotic proteins. Cancer Biol Ther. 2007;6:603–11. doi: 10.4161/cbt.6.4.4226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Fribley A, Zeng Q, Wang CY. Proteasome inhibitor PS-341 induces apoptosis through induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress-reactive oxygen species in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma cells. Mol Cell Biol. 2004;24:9695–704. doi: 10.1128/MCB.24.22.9695-9704.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]