Abstract

We previously demonstrated that intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) administration of protein kinase C (PKC) or protein kinase A (PKA) inhibitors reversed morphine antinociceptive tolerance in 3-day morphine-pelleted mice. The present study aimed at evaluating whether pre-treating mice with a PKC or PKA inhibitor prior to pellet implantation would prevent the development of morphine tolerance and physical dependence. Antinociception was assessed using the warm-water tail immersion test and physical dependence was evaluated by quantifying/scoring naloxone-precipitated withdrawal signs. While drug-naïve mice pelleted with a 75 mg morphine pellet for 3 days developed a 5.8-fold tolerance to morphine antinociception, mice pre-treated i.c.v. with the PKC inhibitors bisindolylmaleimide I, Go-7874 or Go-6976, or with the myristoylated PKA inhibitor, PKI-(14–22)-amide failed to develop any tolerance to morphine antinociception. Experiments were also conducted to determine whether morphine-pelleted mice were physically dependent when pre-treated with PKC or PKA inhibitors. The same inhibitor doses that prevented morphine tolerance were evaluated in other mice injected s.c. with naloxone and tested for precipitated withdrawal. The pre-treatment with PKC or PKA inhibitors failed to attenuate or block the signs of morphine withdrawal including jumping, wet-dog shakes, rearing, forepaw tremor, increased locomotion, grooming, diarrhea, tachypnea and ptosis. These data suggest that elevations in the activity of PKC and PKA in the brain are critical to the development of morphine tolerance. However, it appears that tolerance can be dissociated from physical dependence, indicating a role for PKC and PKA to affect antinociception but not those signs mediated through the complex physiological processes of withdrawal.

Keywords: Morphine, Tolerance, Physical dependence, Antinociception, Protein kinase C, Protein kinase A

1. Introduction

Opioids such as morphine are the most widely used drugs for the alleviation of moderate to severe chronic pain. Systemically administered morphine produces antinociception via actions at both spinal and supra-spinal sites (Barton et al., 1980). Morphine activates descending systems within the brainstem that inhibit dorsal horn nociceptive neurons (Basbaum and Fields, 1984) as well as directly inhibiting spinal cord neurons to prevent transmission to supra-spinal centers (Yaksh and Noueihed, 1985).

However, repeated use of opioids induces tolerance that results in the loss of drug effect or requires escalating doses to produce pain relief. The neurobiological mechanisms of the development of opioid tolerance are multifaceted and only partially understood. Important mechanisms involved in opioid tolerance are cellular and molecular adaptation processes like receptor uncoupling from G-protein (desensitization), opioid agonist-induced receptor internalization or opioid receptor down-regulation leading to a decrease in the number of functional binding sites (Hsu and Wong, 2000; Williams et al., 2001; He et al., 2002; Freye and Latasch, 2003).

The second messenger pathways activating protein kinase C (PKC) and protein kinase A (PKA) have been shown to play an integral role in the development and expression of tolerance to the inhibitory effects of opioids (Narita et al., 1996; Bernstein and Welch, 1997; Smith et al., 1999; Bailey et al., 2006). In our laboratory, intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) administration of PKC or PKA inhibitors not only reversed morphine antinociceptive tolerance (Javed et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2007) but also reinstated the morphine-induced behaviors of antinociception, hypothermia and Straub tail, 72 h after implantation of a 75 mg morphine pellet, to the same extent observed following acute administration of morphine (Smith et al., 2006). These data suggested that elevations in the activity of PKC and PKA in the brain are critical to the expression of morphine tolerance.

The present study aimed at evaluating whether pre-treating mice with PKC or PKA inhibitors prior to pellet implantation would prevent the development of morphine tolerance and physical dependence. We found that mice pre-treated with the PKC inhibitors bisindolylmaleimide I hydrochloride [Bis; (2-[1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-1H-indol-3-yl]-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)-maleimide hydrochloride], Go-7874 hydrochloride [Go-7874; 12-(2-Cyanoethyl)-6,7,12,13-tetrahydro-13-methyl-5-oxo-5H-indolo(2,3-a)pyrrolo(3,4-c)-carbazole], Go-6976 [12-(2-Cyanoethyl)-6,7,12,13-tetrahydro-13-methyl-5-oxo-5H-indolo(2,3-a)pyrrolo(3,4-c) carbazole], or the myristoylated PKA inhibitor, PKI (14–22) amide [PKI-(14–22)-amide; Myr-N-Gly-Arg-Thr-Gly-Arg-Arg-Asn-Ala-Ile-NH2] failed to develop morphine tolerance as assessed in the tail immersion test. However, these same mice became physically dependent on chronic morphine.

2. Results

2.1. Prevention of morphine antinociceptive tolerance

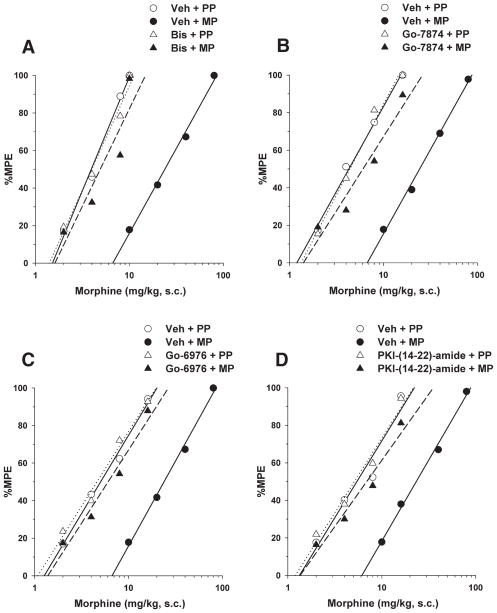

Morphine administered s.c. elicited dose-dependent antinociception in the tail immersion test in both placebo and morphine pellet-implanted mice at 72 h following implantation (Figs. 1A–D). Morphine-pelleted mice pre-treated with vehicle i.c.v. were 5.5-fold tolerant to the antinociceptive effect of acute morphine compared to placebo-pelleted mice. As seen in Fig. 1A, i.c.v. pre-treatment with the PKC inhibitor Bis (44.4 nmol/mouse), 1 h before pellet implantation, completely prevented the development of morphine tolerance. In other words, s.c. morphine was equally potent in placebo- and morphine-pelleted mice injected with Bis i.c.v. The inhibitors selective for inhibiting the conventional PKC isoforms (α, β, γ) were also effective in preventing morphine tolerance. Both Go-7874 (15 nmol/mouse) and Go-6976 (25 nmol/mouse), administered i.c.v. 1 h prior to pellet implantation, also completely prevented morphine tolerance (Figs. 1B, C). The myristoylated PKA inhibitor PKI-(14–22-)-amide was also tested. PKI-(14–22-)amide (5 nmol/mouse), administered i.c.v. 1 h prior to and at 24 and 48 h following pellet implantation, prevented the development of morphine tolerance (Fig. 1D). Table 1 reveals that morphine implantation resulted in tolerance, as indicated by non-overlapping 95% C.L. of the ED50 and significant potency-ratio values. In addition, these values were not significantly different between placebo- and morphine-pelleted mice treated with PKC or PKA inhibitors. The range of inhibitor doses used in this tolerance prevention study were 2- to 4-fold higher than those shown to completely reverse tolerance in our previous studies (Smith et al., 2003, 2006; Javed et al., 2004; Dalton et al., 2005). We also have found that doses as much as 2-fold higher than those used in this study failed to elicit behaviors or toxicity (unpublished findings). No behaviors or toxicity were observed in the animals in this study.

Fig. 1.

Prevention of morphine antinociceptive tolerance in mice by pre-treatment with bisindolylmaleimide I (A), Go-7874 (B), Go-6976 (C) or PKI-(14–22)-amide (D). Mice were injected i.c.v. with vehicle (Veh), bisindolylmaleimide I (Bis; 44.4 nmol/mouse), Go-7874 (15 nmol/mouse) or Go-6976 (25 nmol/mouse) 1 h prior to placebo pellets (PP) or 75 mg morphine pellets (MP). PKI-(14–22)-amide was administered i.c.v. 1 h prior to pellet implantation and at 24 and 48 h following pellet implantation. At 72 h following implantation mice were challenged with various doses of morphine s.c. and their tail immersion latencies were determined for construction of dose–response curves. Data are expressed as mean % MPE ± S.E.M. Each data point represents 6–10 mice.

Table 1.

Morphine antinociceptive tolerance

| Treatment | Morphine ED50 value

|

Potency ratio

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| (mg/kg (95% C.L.)) | (95% C.L.) | ||

| Veh+PP | 6.9 (6.3 to 7.6) | ||

| Veh+MP | 38.2 (34.4 to 42.4)3 | vs. Veh+PP | 5.5 (4.7 to 5.9)a |

| Bis+PP | 7.1 (6.2 to 8.0) | ||

| Bis+MP | 6.8 (6.2 to 7.3) | vs. Bis+PP | 0.9 (0.8 to 0.9) |

| Go-7874+PP | 6.4 (4.8 to 6.9) | ||

| Go-7874+MP | 6.3 (5.4 to 7.2) | vs. Go-7874+PP | 1.0 (0.9 to 01.0) |

| Go-6976+PP | 7.0 (5.6 to 7.5) | ||

| Go-6976+MP | 6.7 (5.9 to 7.2) | vs. Go-6976+PP | 0.9 (0.8 to 0.9) |

| PKI-(14–22)-amide+PP | 6.6 (5.3 to 7.6) | ||

| PKI-(14–22)-amide+MP | 6.2 (5.1 to 6.8) | vs. PKI-(14–22)-amide+PP | 0.9 (0.8 to 0.9) |

Mice were injected i.c.v. with vehicle (Veh), bisindolylmaleimide I (Bis; 44.4 nmol/mouse), Go-7874 (15 nmol/mouse) or Go-6976 (25 nmol/mouse) 1 h prior to placebo pellets (PP) or 75 mg morphine pellets (MP). PKI-(14–22)-amide was administered i.c.v. 1 h prior to pellet implantation and at 24 and 48 h following pellet implantation. At 72 h following implantation mice were challenged with various doses of morphine s.c. and their tail immersion latencies were determined for construction of dose– response curves as well as calculation of ED50 values and potency ratios.

Significantly different than Veh+PP group based on non-overlapping 95% C.L.s.

Significantly different potency ratio since lower 95% C.L. is greater than 1.

2.2. Naloxone-precipitated withdrawal in morphine-tolerant mice

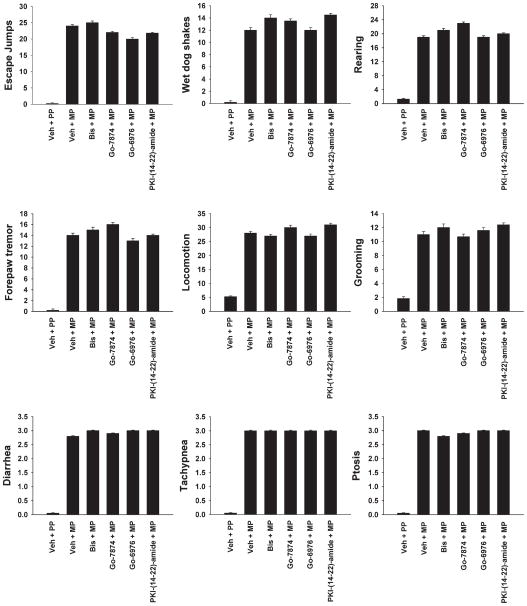

Experiments were conducted to determine whether morphine-pelleted mice were physically dependent when pre-treated with PKC or PKA inhibitors. The PKC inhibitor doses that prevented morphine tolerance were evaluated in other mice injected s.c. with naloxone and tested for precipitated withdrawal. Vehicle, Bis, Go-7874 or Go-6976 was injected i.c.v. 1 h prior to placebo or morphine pellet implantation. Seventy-two hours later, mice were injected with naloxone (1 mg/kg, s.c.). As seen in Fig. 2, morphine-pelleted mice pre-treated with vehicle i.c.v. exhibited jumping, wet-dog shakes, rearing, forepaw tremor, increased locomotion, grooming, diarrhea, tachypnea and ptosis after naloxone administration. The PKC inhibitors Bis, Go-7874 or Go-6976 did not block the counted or the scored signs of withdrawal. Similarly, pre-treatment with PKI-(14–22)-amide i.c.v. at 1 h prior to and at 24 and 48 h following pellet implantation, failed to attenuate or block the signs of morphine withdrawal. Naloxone administered in placebo-pelleted mice injected with vehicle or inhibitors failed to elicit any signs of opioid withdrawal. Thus, it appears that tolerance can be dissociated from physical dependence, indicating a role for PKC and PKA to affect antinociception but not those signs mediated through the complex physiological processes of withdrawal.

Fig. 2.

Influence of pre-treatment with bisindolylmaleimide I, Go-7874, Go-6976 or PKI-(14–22)-amide on withdrawal signs elicited by naloxone in morphine-dependent mice. Mice were injected i.c.v. with vehicle (Veh), bisindolylmaleimide I (Bis; 44.4 nmol/mouse), Go-7874 (15 nmol/mouse) or Go-6976 (25 nmol/mouse) 1 h prior to placebo pellets (PP) or 75 mg morphine pellets (MP). PKI-(14–22)-amide was administered i.c.v. 1 h prior to pellet implantation and at 24 and 48 h following pellet implantation. At 72 h later, mice were injected with naloxone (1 mg/kg, s.c.) and withdrawal signs were measured over 20 min. Escape jumps, wet-dog shakes, rearing, forepaw tremor, locomotion and grooming were counted, whereas diarrhea, tachypnea and ptosis were evaluated as absent (0) or present (1) during each 5-min epoch for 15 min. Data are expressed as mean ± S.E.M.

3. Discussion

3.1. Prevention of morphine antinociceptive tolerance by PKC inhibition

The present study demonstrates that the PKC inhibitor bisindolylmaleimide I (PKCα, βI, βII, ε δ, ζ) (Toullec et al., 1991; Coultrap et al., 1999), as well as the more selective PKC isoform inhibitors (α, βI, βII, γ) Go-7874 (Gschwendt et al., 1995) and Go6976 (Wenzel-Seifert et al., 1994), prevented the development of morphine antinociceptive tolerance. In contrast, this laboratory had previously reported (Javed et al., 2004; Smith et al., 2006) that the PKC inhibitors could acutely reverse tolerance in mice implanted 72 h earlier with morphine pellets. Granados-Soto et al. (2000) demonstrated that a 5-day morphine infusion in rats resulted in an increased phosphorylating activity and in significantly higher levels of PKCα and PKCγ in the dorsal spinal horn. In addition, chronic morphine treatment in mice enhanced cytosolic PKC activity in the brainstem (Narita et al., 1994) and up-regulated membrane-bound PKC in the limbic forebrain including the nucleus accumbens (Narita et al., 2002). Morphine tolerance was prevented when mice were co-infused for 5 days with the antisense oligonucleotide to PKCα and morphine (Hua et al., 2002). A similar attenuated morphine tolerance was observed in PKCγ null mutant mice, suggesting that the level of PKC available for kinase phosphorylation is critical to the development of antinociceptive tolerance (Zeitz et al., 2001). We have recently used pseudosubstrate and RACK (receptors for activated C-kinase) peptides inhibitors that can inhibit only a single PKC isoform, and we demonstrated that the PKCα, γ and ε but not the PKCβI, βII, δ, θ, ε, η and ξ isoforms appear to contribute to the expression of morphine tolerance in mice (Smith et al., 2007).

3.2. Prevention of morphine antinociceptive tolerance by PKA inhibition

The present study also demonstrated that the PKA inhibitor, PKI-(14–22)-amide, 1 h before and 24 and 48 h after morphine pellet implantation completely prevented the development of morphine antinociceptive tolerance. PKI-(14–22)-amide is a selective myristoylated peptide fragment of the autoregulatory domain of PKA (Glass et al., 1989). Pre-treatment with antisense oligodeoxynucleotide to PKA mRNA prevented the development of morphine tolerance, clearly demonstrating that PKA is also critical to the formation of tolerance (Shen et al., 2000). PKI-(14–22)-amide is a competitive catalytic domain inhibitor that required additional injections at 24 and 48 h due to its short duration of action. In contrast, ATP-binding site PKC inhibitors form a covalent bond, and were shown to reverse tolerance for at least 24 h (Smith et al., 2002), and cause significant decreases in spinal PKC levels (Granados-Soto et al., 2000). This could explain why a single dose of PKC inhibitor could be injected, while three doses of PKI-(14–22)-amide were needed to prevent tolerance.

3.3. Role of PKC and PKA inhibitors in morphine physical dependence

The most interesting aspect of this study was that tolerance, but not physical dependence, was prevented by PKC and PKA inhibitor pre-treatment. This laboratory earlier reported on the dissociation between tolerance and dependence when acutely administered PKC inhibitors reversed tolerance but failed to block naloxone-precipitated withdrawal (Smith et al., 2002). Conversely, Cerezo et al., (2002) demonstrated that PKC signaling mechanisms, but not PKA, contribute to hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenocortical hyperactivity during morphine withdrawal in rats. In a later study the same authors reported that myocardial levels of PKA, PKCδ and PKCζ were significantly increased, while PKCα was decreased, in morphine withdrawn rats. Increased autonomic activity during morphine withdrawal result in tachycardia and a pressor response (Michaud and Couture, 2003). PKA and PKC activity could contribute to adaptive increases in autonomic activity in the heart during opioid withdrawal.

The dissociation between tolerance and physical dependence (Table 2) could also be accounted for by the inadequate dose and limited distribution of the drug from the i.c.v. location to brain sites mediating physical dependence. Yet, physical dependence was decreased when the PKC inhibitor 1-(5-isoquinolinesulfonyl)-2-methylpiperazine and morphine were continuously infused for 3 days from osmotic minipumps to cannulae implanted i.c.v. (Tokuyama et al., 1995). Similarly, Fundytus and Coderre (1996) demonstrated significant decreases in naloxone-precipitated withdrawal in rats infused i.c.v. with the PKC inhibitor chelerythrine for 7 days and s.c. with morphine from implanted osmotic minipumps. Thus, continuously infusing rats i.c.v. for 3 or 7 days could have provided adequate PKC inhibitor doses and sufficient diffusion to brain sites mediating physical dependence. In addition, Bohn et al., 2000 demonstrated that in mice lacking beta-arrestin-2, desensitization of the mu-opioid receptor does not occur after chronic morphine treatment, and that these animals fail to develop antinociceptive tolerance. However, the deletion of beta-arrestin-2 does not prevent the chronic morphine-induced up-regulation of adenylyl cyclase activity, a cellular marker of dependence, and the mutant mice still become physically dependent on the drug. Taken together, the method of pre-treating the mice with a single dose of PKC inhibitor i.c.v., and three acute doses of the short acting peptide PKI-(14–22)-amide, could account for our ability to prevent tolerance but fail to prevent the development of physical dependence.

Table 2.

Dissociation between tolerance and physical dependence to morphine

| The effect of PKC or PKA inhibition

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Tolerance | Physical dependence | |

| Prior to morphine | Prevention | No effect |

| After chronic morphine | Reversal | No effect |

The pre-treatment of mice with PKC or PKA inhibitors prevents the development of morphine antinociceptive tolerance whereas acute administration of the same inhibitors reverses the state of tolerance in morphine-tolerant mice. Either of the two treatments failed to prevent or reverse the physical dependence of mice on chronic morphine.

3.4. Perspectives

In summary, PKC and PKA play a pivotal role in maintaining mice in a state of morphine tolerance through increased activation of the phosphatidyl inositol and the adenylyl cyclase pathways. The pre-treatment of mice with PKC or PKA inhibitors prevents the development of morphine antinociceptive tolerance whereas acute administration of the same inhibitors reverses the state of tolerance in morphine-tolerant mice. The lack of ability to prevent the development of physical dependence could be due to an inadequate dose, and lack of diffusion to the sites of action. Clearly, PKC and PKA play a role in dependence, since their protein level was reported to be increased in tissues from morphine withdrawal rats. Further studies are needed to better understand the role played by PKC and PKA not only in the development of opioid dependence but also in naloxone-precipitated withdrawal.

4. Experimental procedures

4.1. Animals

Male Swiss Webster mice (Harlan Laboratories, Indianapolis, IN) weighing 25–30 g were housed 6 to a cage in animal care quarters and maintained at 22 ± 2 °C on a 12 h light–dark cycle. Food and water were available ad libitum. The mice were brought to a test room (22 ± 2 °C, 12 h light–dark cycle), marked for identification and allowed 18 h to recover from transport and handling. Protocols and procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Virginia Commonwealth University Medical Center and comply with the recommendations of the IASP (International Association for the Study of Pain).

4.2. Surgical implantation of pellets

Mice were anesthetized with 2.5% isoflurane before shaving the hair around the base of the neck. Adequate anesthesia was noted by the absence of the righting-reflex and lack of response to toe-pinch, according to IACUC guidelines. The skin was cleansed with 10% povidone iodine (General Medical Corp., Prichard, WV) and rinsed with alcohol before making a 1 cm horizontal incision at the base of the neck. The underlying subcutaneous space toward the dorsal flanks was opened using a sterile glass rod. Maintenance of a stringent aseptic surgical field minimized any potential contamination of the pellet, incision and subcutaneous space. A placebo pellet or 75 mg morphine pellet was inserted in the space before closing the site with Clay Adams Brand, MikRon® AutoClip® 9 mm Wound Clips (Becton Dickinson and Co., Sparks, MD) and again applying iodine to the surface. The animals were allowed to recover in their home cages where they remained throughout the experiment.

4.3. Intracerebroventricular injections

Intracerebroventricular (i.c.v.) injections were performed as described by Pedigo et al. (1975). Mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and a horizontal incision was made in the scalp. A free-hand 5 μl injection of the drug or vehicle was made in the lateral ventrical (2 mm rostral and 2 mm lateral at a 45° angle from the bregma). The extensive experience of this laboratory has made it possible to inject drugs with greater than 95% accuracy. Immediately after testing, the animals were euthanized to minimize any type of distress, according to IACUC guidelines. It is worth mentioning that the PKA inhibitor PKI-(14–22)-amide was administered each day for 3 successive days by i.c.v. injection without implantation of a cannula. However, no central nervous system damage was observed following this repetitive i.c.v. administration.

4.4. Tail immersion test

The warm-water tail immersion test was performed according to Coderre and Rollman (1983) using a water bath with the temperature maintained at 56 ± 0.1 °C. Before injecting the mice, a baseline (control) latency was determined. Only mice with a control reaction time from 2 to 4 s were used. The average baseline latency for these experiments was 3.0 ± 0.1 s. The test latency after drug treatment was assessed at the appropriate time, and a 10 s maximum cut-off time was imposed to prevent tissue damage. Antinociception was quantified according to the method of Harris and Pierson (1964) as the percentage of maximum possible effect (%MPE) which was calculated as: %MPE = [(test latency –control latency)/(10–control latency)]×100. Percent MPE was calculated for each mouse using at least 6 mice per drug.

4.5. Naloxone-precipitated withdrawal

Withdrawal was precipitated in mice at 72 h from pellet implantation with naloxone (1 mg/kg, s.c.) and was scored according to the method described by Vaupel et al. (1997). Mice were allowed for 30 min to habituate to an open-topped, square, clear Plexiglas observation chamber (26×26×26 cm) with lines partitioning the bottom into quadrants then given naloxone. Withdrawal commenced within 1 min after naloxone administration. Withdrawal signs were measured over 20 min. Signs quantified by counting their occurrences were jumping (escape jumps), wet-dog shakes, rearing, forepaw tremor, quadrant crossing (locomotion) and grooming. Other signs, evaluated as absent (0) or present (1) during each 5-min epoch for 15 min, included diarrhea, tachypnea and ptosis. The maximal score for each of the quantal signs was 3 (1 point per 5-min epoch).

4.6. Drugs and chemicals

The placebo and 75 mg morphine pellets were obtained from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA), Bethesda, MD. Morphine sulfate (Mallinckrodt, St. Louis, MO) was dissolved in pyrogen-free isotonic saline (Baxter Healthcare, Deerfield, IL). Bisindolylmaleimide I [Bis; (2-[1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-1H-indol-3-yl]-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)-maleimide hydrochloride], Go-7874 hydrochloride [Go-7874; 12-(2-Cyanoethyl)-6,7,12,13-tetrahydro-13-methyl-5-oxo-5H-indolo (2,3-a)pyrrolo(3,4-c)-carbazole hydrochloride], Go-6976 [12-(2-Cyanoethyl)-6,7,12,13-tetrahydro-13-methyl-5-oxo-5H-indolo(2,3-a)pyrrolo(3,4-c) carbazole], and myristoylated PKI (14–22) amide [PKI-(14–22)-amide; Myr-N-Gly-Arg-Thr-Gly-Arg-Arg-Asn-Ala-Ile-NH2] were purchased from Calbiochem (San Diego, CA, USA). Bis, Go-7874 and PKI-(14–22)-amide were dissolved in distilled water, whereas Go-6976 was dissolved in 10% dimethyl sulfoxide, 20% cremophor, 70% distilled water. We have previously published on the use of this vehicle for i.c.v. injections (Smith et al., 1999, 2002, 2003, 2006). The control vehicle-injected mice were injected with 10% DMSO, 20% cremophor, 70% distilled water.

4.7. Experimental design and statistical analysis

In the first series of experiments, morphine dose–response curves were generated in placebo- and morphine-pelleted mice 72 h following pellets implantation, to test for the development of tolerance. Baseline measures of tail immersion were obtained prior to subcutaneous (s.c.) morphine administration. The following experiments then examined the effects of i.c.v. pre-treatment with the PKC inhibitors Bis (44.4 nmol/mouse), Go-7874 (15 nmol/mouse) and Go-6976 (25 nmol/mouse) as well as the PKA inhibitor PKI-(14–22)-amide (5 nmol/mouse) on the expression of antinociceptive tolerance to morphine.

In another series of experiments, placebo- and morphine-pelleted mice were administered naloxone to evaluate the precipitation of both counted and scored signs of withdrawal. A final series of experiments was conducted to determine whether the i.c.v. pre-treatment with the PKC or PKA inhibitors would block naloxone-precipitated withdrawal in morphine-dependent mice.

Morphine effective dose-50 (ED50) values were calculated using least-squares linear regression analysis followed by calculation of 95% confidence limits (95% C.L.) by the method of Bliss (1967). Tests for parallelism were conducted before calculating the potency-ratio values with 95% C.L. by the method of Colquhoun (1971). Colquhoun notes that a potency-ratio value of greater than one, with the lower 95% C.L. greater than one, is considered a significant difference in potency between groups.

Data are expressed as mean values ± S.E.M. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by the post hoc “Student–New-man–Keuls” test were performed to assess significance using the Instat 3.0 software (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). The counted withdrawal signs of jumping, wet-dog shakes, rearing, forepaw tremor, and quadrant crossing, and grooming were counted and subjected to two-factor ANOVA. The scored signs of diarrhea, tachypnea and ptosis were analyzed with the chi-square χ2 test. P<0.05 was considered significant.

Acknowledgments

We thank Joshua A. Seager and David L. Stevens for valuable technical assistance during these studies. This work was funded by the National Institute on Drug Abuse grants: DA-01647 and DA-020836.

Abbreviations

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PKA

protein kinase A

- ED50

50% effective dose

- %MPE

percent maximum possible effect

- i.c.v

intracerebroventricular

- s.c

subcutaneous

- Bis

(2-[1-(3-dimethylaminopropyl)-1H-indol-3-yl]-3-(1H-indol-3-yl)-maleimide hydrochloride

- Go-7874

Go-7874 12-(2-Cyanoethyl)-6,7,12,13-tetrahydro-13-methyl-5-oxo-5H-indolo(2,3-a)pyrrolo(3,4-c)-carbazole

- Go-6976

12-(2-Cyanoethyl)-6,7,12,13-tetrahydro-13-methyl-5-oxo-5H-indolo(2,3-a)pyrrolo(3,4-c) carbazole

- PKI-(14–22)-amide

Myr-N-Gly-Arg-Thr-Gly-Arg-Arg-Asn-Ala-Ile-NH2

References

- Bailey CP, Smith FL, Kelly E, Dewey WL, Henderson G. How important is protein kinase C in mu-opioid receptor desensitization and morphine tolerance? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:558–565. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barton C, Basbaum AI, Fields HL. Dissociation of supraspinal and spinal actions of morphine: a quantitative evaluation. Brain Res. 1980;188:487–498. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(80)90047-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basbaum AI, Fields HL. Endogenous pain control systems: brainstem spinal pathways and endorphin circuitry. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1984;7:309–338. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.07.030184.001521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernstein MA, Welch SP. Effects of spinal versus supraspinal administration of cyclic nucleotide-dependent protein kinase inhibitors on morphine tolerance in mice. Drug and Alcohol Depend. 1997;44:41–46. doi: 10.1016/s0376-8716(96)01320-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bliss CI. Statistics in Biology. McGraw-Hill; New York, NY: 1967. p. 439. [Google Scholar]

- Bohn LM, Gainetdinov RR, Lin FT, Lefkowitz RJ, Caron MG. Mu-opioid receptor desensitization by beta-arrestin-2 determines morphine tolerance but not dependence. Nature. 2000;408:720–723. doi: 10.1038/35047086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerezo M, Laorden ML, Milanés MV. Inhibition of protein kinase C but not protein kinase A attenuates morphine withdrawal excitation of rat hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis. Eur J Pharmacol. 2002;452:57–66. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(02)02245-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coderre TJ, Rollman GB. Naloxone hyperalgesia and stress-induced analgesia in rats. Life Sci. 1983;32:2139–2146. doi: 10.1016/0024-3205(83)90103-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colquhoun D. Lectures on Biostatistics: an Introduction to Statistics with Applications in Biology and Medicine. Clarendon Press; Oxford: 1971. pp. 327–333. [Google Scholar]

- Coultrap SJ, Sun H, Tenner TE, Jr, Machu TK. Competitive antagonism of the mouse 5-hydroxytryptamine3 receptor by bisindolylmaleimide I, a “selective” protein kinase C inhibitor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;290:76–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dalton GD, Smith FL, Smith PA, Dewey WL. Alterations in brain Protein Kinase A activity and reversal of morphine tolerance by two fragments of native Protein Kinase A inhibitor peptide (PKI) Neuropharmacology. 2005;48:648–657. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2004.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freye E, Latasch L. Development of opioid tolerance—molecular mechanisms and clinical consequences. Anasthesiol Intensivmed Notfallmed Schmerzther. 2003;38:14–26. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-36558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fundytus ME, Coderre TJ. Chronic inhibition of intracellular Ca2+ release or protein kinase C activation significantly reduces the development of morphine dependence. Eur J Pharmacol. 1996;300:173–181. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00871-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glass DB, Cheng HC, Mende-Mueller L, Reed J, Walsh DA. Primary structural determinants essential for potent inhibition of cAMP-dependent protein kinase by inhibitory peptides corresponding to the active portion of the heat-stable inhibitor protein. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:8802–8810. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Granados-Soto V, Kalcheva I, Hua X, Newton A, Yaksh TL. Spinal PKC activity and expression: role in tolerance produced by continuous spinal morphine infusion. Pain. 2000;85:395–404. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(99)00281-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gschwendt M, Furstenberger G, Leibersperger H, Kittstein W, Lindner D, Rudolph C, Barth H, Kleinschroth J, Marme D, Schachtele C. Lack of an effect of novel inhibitors with high specificity for protein kinase C on the action of the phorbol ester 12-O-tetradecanoylphorbol-13-acetate on mouse skin in vivo. Carcinogenesis. 1995;16:107–111. doi: 10.1093/carcin/16.1.107. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris LS, Pierson AK. Some narcotic antagonists in the benzomorphan series. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1964;143:141–148. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He L, Fong J, von Zastrow M, Whistler JL. Regulation of opioid receptor trafficking and morphine tolerance by receptor oligomerization. Cell. 2002;108:271–282. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00613-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hsu MM, Wong CS. The roles of pain facilitatory systems in opioid tolerance. Acta Anaesthesiol Sin. 2000;38:155–166. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua XY, Moore A, Malkmus S, Murray SF, Dean N, Yaksh TL, Butler M. Inhibition of spinal protein kinase Calpha expression by an antisense oligonucleotide attenuates morphine infusion-induced tolerance. Neuroscience. 2002;113:99–107. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(02)00157-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Javed RR, Dewey WL, Smith PA, Smith FL. PKC and PKA inhibitors reverse tolerance to morphine-induced hypothermia and supraspinal analgesia in mice. Eur J Pharmacol. 2004;492:149–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2004.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michaud N, Couture R. Cardiovascular and behavioural effects induced by naloxone-precipitated morphine withdrawal in rat: characterization with tachykinin antagonists. Neuropeptides. 2003;37:345–354. doi: 10.1016/j.npep.2003.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita M, Makimura M, Feng Y, Hoskins B, Ho IK. Influence of chronic morphine treatment on protein kinase C activity: comparison with butorphanol and implication for opioid tolerance. Brain Res. 1994;650:175–179. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(94)90224-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita M, Mizoguchi H, Kampine JP, Tseng LF. Role of protein kinase C in desensitization of spinal delta-opioid-mediated antinociception in the mouse. Br J Pharmacol. 1996;118:1829–1835. doi: 10.1111/j.1476-5381.1996.tb15610.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita M, Mizuo K, Shibasaki M, Narita M, Suzuki T. Up-regulation of the G(q/11alpha) protein and protein kinase C during the development of sensitization to morphine-induced hyperlocomotion. Neuroscience. 2002;111:127–132. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(01)00515-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedigo NW, Dewey WL, Harris LS. Determination and characterization of the antinociceptive activity of intraventricularly administered acetylcholine in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1975;193:845–852. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Gomes AB, Gallagher A, Stafford K, Yoburn BC. Role of cAMP-dependent protein kinase (PKA) in opioid agonist-induced mu-opioid receptor downregulation and tolerance in mice. Synapse. 2000;38:322–327. doi: 10.1002/1098-2396(20001201)38:3<322::AID-SYN11>3.0.CO;2-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith FL, Gabra BH, Smith PA, Redwood MC, Dewey WL. Determination of the role of conventional, novel and atypical PKC isoforms in the expression of morphine tolerance in mice. Pain. 2007;127:129–139. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2006.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith FL, Javed RR, Elzey MJ, Dewey WL. The expression of a high level of morphine antinociceptive tolerance in mice involves both PKC and PKA. Brain Res. 2003;985:78–88. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(03)03170-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith FL, Javed RR, Elzey MJ, Welch SP, Selley D, Sim-Selley L, Dewey WL. Prolonged reversal of morphine tolerance with no reversal of dependence by protein kinase C inhibitors. Brain Res. 2002;958:28–35. doi: 10.1016/s0006-8993(02)03394-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith FL, Javed RR, Smith PA, Dewey WL, Gabra BH. PKC and PKA inhibitors reinstate morphine-induced behaviors in morphine tolerant mice. Pharmacol Res. 2006;54:474–480. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2006.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith FL, Lohman AB, Dewey WL. Influence of phospholipid signal transduction pathways in morphine tolerance in mice. Br J Pharmacol. 1999;128:220–226. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjp.0702771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tokuyama S, Feng Y, Wakabayashi H, Ho IK. Possible involvement of protein kinases in physical dependence on opioids: studies using protein kinase inhibitors, H-7 and H-8. Eur J Pharmacol. 1995;284:101–107. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(95)00370-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toullec D, Pianetti P, Coste H, Bellevergue P, Grand-Perret T, Ajakane M, Baudet V, Boissin P, Boursier E, Loriolle F. The bisindolylmaleimide GF 109203X is a potent and selective inhibitor of protein kinase C. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:15771–15781. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaupel DB, Kimes AS, London ED. Further in vivo studies on attenuating morphine withdrawal: isoform-selective nitric oxide synthase inhibitors differ in efficacy. Eur J Pharmacol. 1997;324:11–20. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(97)00061-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wenzel-Seifert K, Schachtele C, Seifert R. N-protein kinase C isoenzymes may be involved in the regulation of various neutrophil functions. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;200:1536–1543. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams JT, Christie MJ, Manzoni O. Cellular and synaptic adaptations mediating opioid dependence. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:299–343. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.1.299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yaksh TL, Noueihed R. The physiology and pharmacology of spinal opiates. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1985;25:433–462. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.25.040185.002245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeitz KP, Malmberg AB, Gilbert H, Basbaum AI. Reduced development of tolerance to the analgesic effects of morphine and clonidine in PKC gamma mutant mice. Pain. 2001;94:245–253. doi: 10.1016/S0304-3959(01)00353-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]