Abstract

Ras family small GTPases serve as binary molecular switches to regulate a broad array of cellular signaling cascades, playing essential roles in a vast range of normal physiological processes, with dysregulation of numerous Ras-superfamily G-protein-dependent regulatory cascades underlying the development of human disease. However, the physiological function for many “orphan” Ras-related GTPases remain poorly characterized, including members of the Rit subfamily GTPases. Rit is the founding member of a novel branch of the Ras subfamily, sharing close homology with the neuronally expressed Rin and Drosophila Ric GTPases. Here, we highlight recent studies using transgenic and knockout animal models which have begun to elucidate the physiological roles for the Rit subfamily, including emerging roles in the regulation of neuronal morphology and cellular survival signaling, and discuss new genetic data implicating Rit and Rin signaling in disorders such as cancer, Parkinson’s disease, autism, and schizophrenia.

Keywords: Ras GTPase, Rin, MAPK, Neuron, Signaling

1. Introduction

The Ras superfamily of low molecular weight GTP-binding proteins is a group of structurally related, and evolutionarily conserved proteins, which share the ability to undergo guanine nucleotide-dependent conformational change [1]. Functioning with their allied regulatory and effector protein networks, Ras-related GTPases serve as critical cellular biotimers, coupling diverse cellular stimuli to the regulation of signal transduction pathways that contribute to almost every aspect of cellular physiology. All Ras family guanosine triphosphate phosphatases (GTPases) contain five conserved amino acid motifs (G1–G5) with distinct roles in phosphate binding (G1 and G3), GTP binding and hydrolysis (G4 and G5), and effector protein binding (G2), as detailed by extensive mutagenesis and structural studies [1]. The activation of Ras superfamily GTPases is initiated by the exchange of bound GDP for GTP, resulting in a conformational change within the effector loop (G2 domain) allowing for effector protein binding [2, 3]. Activation is under the control of guanine nucleotide exchange factors (GEFs) which favor the release of GDP. The hydrolysis of bound GTP to GDP returns Ras family members to the “inactive” conformational state [3]. GTPase-activating proteins (GAPs) accelerate the intrinsic GTPase activity of Ras superfamily GTPases, comprising a second set of regulatory proteins [3].

Over 160 members of Ras superfamily members have been discovered and grouped into five broad families – Ras, Rho, Rab, Arf and Ran [2–4]. The members of each family can be further subdivided into evolutionarily conserved subfamilies reflecting additional levels of structural, biochemical, and functional conservation [1]. The vertebrate Rit and Rin proteins, along with Drosophila homolog D-Ric, comprise the Rit subfamily GTP-binding proteins [4]. Here, we discuss recent progress in the characterization of the physiological function of this novel branch of the Ras subfamily.

2. Rit subfamily GTPases

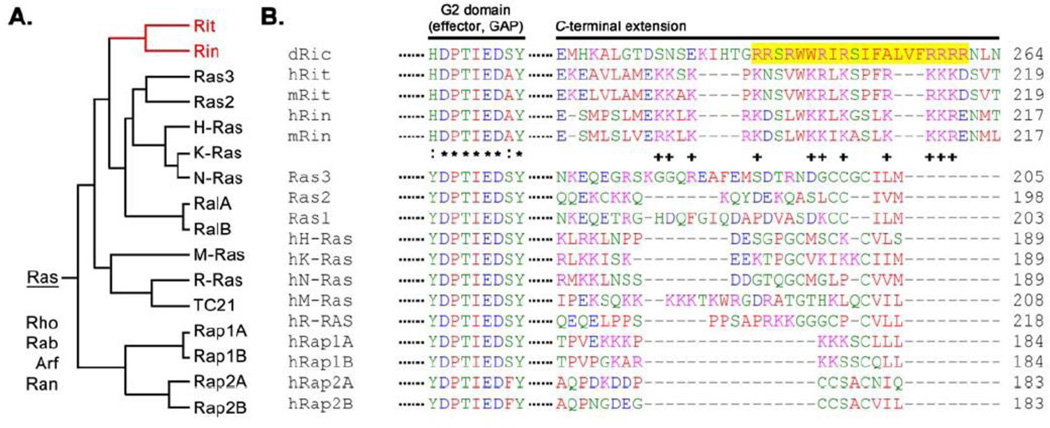

The first member of the Rit subfamily, Ras-related protein which interacted with calmodulin (Ric), was identified in a screen for calmodulin-binding proteins expressed in the Drosophila retina [5]. A subsequent homology search for Ric-related genes by Wes et al. identified the vertebrate Rit (Ric-related gene expressed throughout the organism) and Rin (Ric-related gene expressed in neural tissues) [5], each containing a well-conserved GTPase core (G1–G5) (Fig. 1A). Lee et al [6] used a degenerate RT-PCR based cloning strategy, while Shao et al. [7] used an expression cloning strategy from retina, to independently identify these novel GTPases. In keeping with their names, Northern blot analysis has shown Rit to be widely expressed, while Rin mRNA is detected exclusively in the brain [5, 6]. In addition, Rit and Rin display distinct patterns of developmental expression, with Rit being expressed throughout development, while Rin expression is delayed to later stages of embryonic neuronal development (E14), with highest Rin expression found in the adult brain [6, 8]. Rit and Rin share 64% amino acid identity, and share 66% and 71% identity respectively, with dRic [5, 6]. When compared with other Ras subfamily GTPases, Rit and Rin share a unique G2 domain (HDPTIEDAY, conserved across vertebrates), while the highly related G2 domain of Ric varies by only a single amino acid (HDPTIEDSY) (Fig. 1B) [5, 6]. Whether this substitution alters the spectrum of effector proteins regulated by Ric, relative to those identified for Rit and Rin, remains to be determined.

Figure 1. Rit subfamily small GTPases.

(A) Rit, Rin, and Drosophila dRic define a novel subfamily of the Ras-related small GTPases. (B) Amino acid sequence alignment of the G2 (effector) and C-terminal extension domains of human Rit and Rin, M. Racemosus Ras 3 and Ras 2, human H-, K-, N-, M-, R-Ras, RalA/B, TC21, Rap1A/B, and Rap2A/B proteins. The Rit subfamily contains a unique G2 domain (effector loop) and polybasic C-terminus but lacks classic CAAX prenylation motifs. The highlighted sequence is the calmodulin binding motif of dRIC. :, substitution of residue between Rit GTPases and the larger Ras family; *, conserved residues across the entire Ras family of GTPases; +, conserved polybasic residues within Rit family proteins.

Rit shares a highly conserved C-terminus with Rin (52%) but not dRic [5], and this domain has been shown to direct plasma membrane association [5, 6]. Rit and Rin do not contain canonical lipid modification motifs (particularly prenylation, palmitoylation, or myristoylation) found to direct membrane localization for the majority of the Ras family [9] (Fig. 1B). Instead, the extended C-terminus of the Rit GTPases contains a conserved polybasic region (Fig. 1) [5]. The association of this polybasic cluster with phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate [PI(4,5)P2] and phosphatidylinositol 3,4,5-trisphosphate [PI(3,4,5)P3] lipids has been found to direct plasma membrane targeting [10], suggesting that PI lipid second messengers play a central role in the regulation of Rit/Rin signaling. Additional studies are necessary to explore how a polybasic-nonlipid membrane targeting motif might impart unique regulatory properties to Rit family GTPases.

Biochemical studies have revealed that Rit and Rin possess selective and high affinity GDP and GTP binding, and exhibit canonical GTPase activity [6, 7]. Furthermore, mutation of the glutamine residue in Rit and Rin (Rit-Q79L and Rin-Q78L), found to play a critical role in GTP hydrolysis for Ras (Gln61 in H-, N-, and K-Ras) [7], disrupts the intrinsic GTPase activity of both mutant proteins. Rin is activated by growth factors including nerve growth factor (NGF) [8, 11], epidermal growth factor (EGF) [8, 12], neurotrophic peptide pituitary adenylate cyclase activated polypeptide 38 (PACAP38) [13], phorbol 12-myristate and ionomycin [12]. Interestingly, expression of constitutively activated (CA) H-RasQ61L stimulates GTP-Rin levels in neuronal but not non-neuronal cells, while expression of a dominant negative (DN) H-RasS17N mutant disrupts NGF-induced Rin activation [8]. These results suggest that Rin may function as a downstream target of Ras signaling, similar to that for the Ral GTPases [14], but additional studies are needed to build upon these intriguing observations.

Rit has been shown to be activated by diverse cellular stimuli, including mitogens such as NGF [15–18], EGF [16, 18], bone morphogenetic protein 7 (BMP7) [15, 18], neurotrophic polypeptide PACAP38, and by elevated cellular cAMP levels [18–20]. In addition, active Gsα, Giα and Gqα, but not G12α, are capable of stimulating Rit and have been shown to contribute to a PACAP38-Epac-dependent Rit activation cascade [19, 20]. Subsequent studies have found that Gsα and Giα are required for PACAP38-mediated Rin activation [13]. In contrast to Rin, Rit is also activated by diverse cellular stresses including interferon-γ (IFNγ) [18, 21], tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) [18], DNA damage [18], and oxidative stress [18, 22].

The vast majority of Ras family GTPases function as molecular switches regulated primarily through nucleotide exchange facilitated by regulatory proteins, including the actions of selective GEFs and GAPs [23]. In response to appropriate cellular stimulation, both Rit and Rin GTPases undergo rapid activation and remain GTP-bound for prolonged periods [8, 11–13, 15–22]. This is similar to the activation kinetics seen for the Rap G-proteins [24, 25], rather than the transient activation observed following mitogen-dependent Ras stimulation [8, 16, 24, 25]. Thus, it appears that Rit and Rin undergo a canonical GTP/GDP cycle, likely under the control of regulatory GEF and GAP proteins [7]. While these regulatory proteins remain to be identified, Rin has been found to associate with the son of sevenless (mSOS) GEF [12]. In addition, expression of the SynGAP and GAP1 Ras-GAP proteins, but not the Rap1-specific Rap1-GAP, has been shown to decrease cellular levels of GTP-bound Rin [12]. However, direct in vitro evidence is lacking in support of these proteins functioning as Rin GEFs/GAPs. A similar knowledge gap exists for Rit: with expression of the RasGEFs SOS and GRF found to elevate Rit-GTP levels in cultured cells [8]. Interestingly, while Epac (exchange protein directly activated by cAMP) is required for PACAP38-mediated Rit activation, in vitro GEF analysis indicates that Epac is not a direct RitGEF [19]. Instead, a recent study found that Src-dependent TrkA receptor transactivation was involved in PACAP38-dependent Rit activation, with RNA interference suggesting that SOS1/2 GEFs were required for Rit activation [20].

3. Rit subfamily-dependent signal transduction pathways

Ras family G-proteins relay cellular signals to defined cellular effectors, resulting in the activation of diverse signaling pathways including mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) family protein kinases, phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K)/Akt [protein kinase B (PKB)], and RalGEFs, among others [2]. Although early studies in NIH3T3 cells failed to identify common effectors for Rit, Rin, and Ras [26, 27], Shao et al. [7, 28] utilized a yeast-two-hybrid strategy to identify the Ras-binding domain (RBD) of Raf1 (Raf-RBD), AF6, RalGDS and Rlf, and the p110 catalytic subunit of PI3K as Rit and Rin binding partners [7]. These interactions appeared to be GTP-dependent, since the putative dominant-negative Rit (Rit-S35N) and Rin (Rin-S34N) mutants failed to interact [7]. The GTP-dependence of binding was confirmed by in vitro binding assays using radiolabeled GTPγS- or GDP-preloaded Rit/Rin proteins [7]. Since these initial studies, an emerging picture indicates that Rit and Rin share not only overlapping, but also distinct effectors, with Ras (Fig. 3).

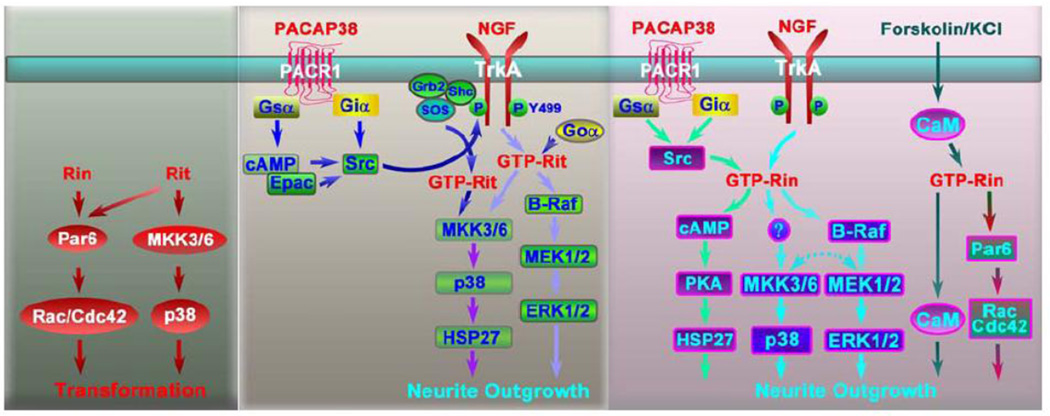

Figure 3. Rit subfamily GTPase-mediated signal transduction pathways in cell transformation and neurite outgrowth.

(A) Rit- and Rin-induced signaling in cell transformation and tumorigenesis. (B) Rit-dependent signaling in neurite outgrowth. Rit triggers neurite outgrowth via both ERK and p38 MAPK pathways and contributes to both NGF- and PACAP38-induced neuronal differentiation. PACAP-dependent neuronal differentiation involves PACR1-Epac-Src cascade mediated transactivation of the TrkA receptor, resulting in Rit activation and neurite elongation. (C) Rin-dependent signaling in neurite outgrowth. Rin-induced neurite outgrowth has been found to depend upon ERK, p38, calmodulin and Rac/Cdc42 signaling. The contribution of Rin to NGF-induced neurite outgrowth requires both ERK and p38 signaling, whereas PACAP38-mediated neurite elongation involves Src-dependent Rin activation, leading to cAMP-PKA-HSP27 signaling. Rin-B-Raf directed crosstalk between the ERK and p38 MAPK cascades may exist, but remains uncharacterized (dashed arrow).

3.1 ERK MAPK

Ras activation of Raf/MEK/ERK pathway is one of the best characterized signal transduction pathways in biology [29, 30]. Although Rit and Rin associate in a GTP-dependent manner with Raf family kinases, Raf-1 (C-Raf) and B-Raf, binding only results in B-Raf activation [11, 16], suggesting that Rit/Rin direct B-Raf-specific ERK signaling. Consistent with this notion, activated Rit- and Rin-dependent ERK activation is enhanced by B-Raf co-expression [11, 16], and inhibited by expression of a dominant-negative B-Raf mutant [16]. Expression of constitutively active Rit and Rin has been shown to stimulate ERK activity [15–17, 31]. In contrast, expression of Rin-Q78L does not elicit robust ERK activation [8, 32], instead promoting only modest ERK phosphorylation [11]. Rit-Q79L triggers MEK phosphorylation [16], and pretreatment with the MEK inhibitor PD98059, blocks both Rit and Rin-mediated ERK activation [11, 16], suggesting that Rit and Rin are both capable of regulating the MEK-ERK signaling cascade. Together, these data strongly implicate the B-Raf- MEK1-ERK cascade as operating downstream of Rit subfamily signaling.

While expression of constitutively active Rit promotes ERK activation in a variety of cultured cells, the importance of Rit to endogenous ERK regulation appears more nuanced. For example, while expression of a DN-Rit mutant [17], or RNAi-dependent silencing of endogenous Rit, attenuate NGF-TrkA-dependent ERK activation in PC6 cells [16], Rit inhibition does not affect PACAP38-mediated ERK activation in PC6 cells [19]. Furthermore, BDNF-dependent ERK activation is not altered in primary hippocampal neurons isolated from Rit−/− mice [33]. Together, these data demonstrate that while Rit is capable of coupling upstream stimuli to ERK activation, its importance/specific contribution to ERK signaling is likely to vary in a receptor and cell type-dependent fashion. RNAi-mediated Rin silencing does not alter PACAP38-dependent ERK activation in PC6 cells, which is consistent with a minor role for Rin in regulating ERK signaling [11]. However, Rin silencing has been shown to inhibit NGF-mediated B-Raf activation [11], suggesting that Rin might contribute to an ERK-independent signaling pathway downstream of B-Raf.

3.2 p38 MAPK

An emerging literature suggests that Rit and Rin utilize signal transduction cascades distinct from those activated by other Ras family members (Fig. 3). Specifically, a series of recent studies indicate that p38, but not ERK, MAPK signaling plays a central role in Rit-dependent control of cell growth and cellular behavior. Gene silencing studies indicate that Rin is required for neurotrophin-mediated p38 activation, but that Rin function is not required for p38 activation in response to a diverse array of additional stimuli [11], comparable to the emerging role for Rit in ERK signaling (see above). However, it should be noted that Rin is expressed exclusively in neurons [5, 6], and the actual contribution of Rin to signal transduction may not be understood until studies have been performed in primary neurons. Strikingly, co-expression of B-Raf results in a synergistic increase in Rin-mediated ERK and p38 phosphorylation in PC6 cells [11], suggesting an unexpected role for B-Raf in Rin-dependent p38 signaling. Indeed, while p38 inhibition reduces Rin-mediated neurite outgrowth in PC6 cells it enhances neurite outgrowth in Rin/B-Raf co-expressing cells [11]. These data are consistent with the role for B-Raf in generating integrated and cooperative ERK and p38 MAPK signaling downstream of Rin, which may be critical for regulation of neuronal functions as diverse as differentiation and survival [11]. However, mechanistic insight into how B-Raf might contribute to Rin-dependent p38 activation is lacking, and the importance of p38 signaling to Rin function awaits further characterization, particularly the analysis of this cascade in primary neurons.

In contrast to the limited role for Rin, in vitro studies suggest that Rit directs p38 activation [19, 27] downstream of a broad array of extracellular stimuli, including not only a number of growth factors and cytokines, but also in response to DNA damage and reactive oxygen species (ROS) in cultured cells [16, 18, 19, 21]. Furthermore, ROS-mediated p38 activation is impaired in Rit-null (Rit−/−) mouse embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) and primary hippocampal neurons [34], and both the amplitude and duration of p38 activation in response to heat stress is significantly blunted in D-Ric null Drosophila (dRic−/−)[33]. Taken together these results suggest that Rit plays a critical, and evolutionarily conserved, role in controlling p38 MAPK activity in response to both mitogens and environmental stress.

Although p38 signaling is commonly associated with the induction of cell death, recent work has identified a survival cascade in which p38 promotes MK2 kinase activation within a novel HSP27 scaffolded complex [35–37]. Association with the scaffolded complex allows MK2 to phosphorylate both HSP27 and Akt, to promote survival [35, 36, 38]. Using RNAi silencing methods, the HSP27-scaffolded p38-MK2 signaling complex was shown to be critical for Rit-dependent Akt activation [18]. Moreover, Rit was found to contribute to stress-dependent p38-MK2-HSP27-Akt activation in cultured cells [18], and ROS-dependent p38, MK2, HSP27 and Akt activation was found to be impaired in Rit−/− MEFs [22]. Importantly, disruption of the p38-MK2-HSP27 cascade does not alter H-Ras-mediated Akt activation, suggesting that Rit might selectively associate with the scaffolded complex. In support of this model, Rit was found to co-immunoprecipitate with p38, MK2, HSP27, and Akt, whereas H-Ras failed to associate with either HSP27 or Akt [18]. Thus, Rit associates with and is required for stress-dependent activation of a scaffolded p38-MK2-HSP27-Akt survival signaling cascade.

3.3 Par6-Rac/Cdc42

Hoshino et al. [39] identified ternary complexes containing either Rit or Rin, Rac/Cdc42, and Par6, suggesting that Rit and Rin might function as upstream regulators of Par6-Rac/Cdc42 signaling (Fig. 3). Par6 association was GTP-dependent and mediated through the PDZ domain, although neither Rit nor Rin contain a canonical C-terminal PDZ interaction sequence [40]. These results are in agreement with an earlier study, in which Rin was found to activate Rac, Cdc42 and RhoA when expressed in PC12 cells [32]. Importantly, co-transfection of constitutively active Rit/Rin with PAR6, and constitutively active Rac/Cdc42, resulted in a synergistic increase in NIH3T3 cell transformation [39], providing experimental support for a physiological role for PAR6-dependent signaling. Hoshino et al. [32] has also shown that expression of active Rin in pheochromocytoma cells (PC12) results in neuronal differentiation by directing Rac/Cdc42-dependent signaling. However, the contribution of Par6 to this pathway awaits characterization.

A subsequent study by Rudolph et al. [41] has challenged the nature of Rit/Par6 association. While Rit was found to associate with all three members of the mammalian Par6 family (Par6A-C) in this study, Rit co-immunoprecipitated with full-length, ΔPDZ, and ΔN (deletion of N-terminal 1–153 aa that contains PB1 and CRIB domains) mutants of Pac6C, suggesting that Rit binding does not depend on the PDZ domain. In addition, Par6C was found to associate most strongly with Rit-S35N, a dominant-negative mutant, suggesting that Par6 binding is not GTP-dependent. Indeed, in vitro binding studies found that GDP- and GTPγS-Rit displayed equivalent, and rather low affinity, Par6 binding. These data suggest that the Rit/PAR6 association observed following overexpression is not the result of direct PAR6 binding, but instead might be mediated by interaction of Rit with the larger scaffolded Par6 complex [41]. Taken together, these studies suggest that Rit/Rin-Par6 association may be complex, and that while PAR6 signaling may represent an important effector pathway, elucidation of the role for Par6 in Rit/Rin-mediated signaling will require additional investigation.

3.4 RalGEFs

Shao et al. [7, 28] identified the RalGDS gene family member, RGL3 (RalGDS-like 3), as a Rit interacting protein using a yeast-two-hybrid strategy [28]. RGL3 association required an intact Rit effector domain and was GTP-dependent, the hallmarks of authentic effector interaction. Importantly, Rit has been shown to direct Ral activation in a manner that was enhanced by co-expression of RGL3. Taken together, these data indicate that Rit directs a RGL3-Ral signaling cascade. However, the contribution of Ral signaling to Rit function remains poorly understood [42].

3.5 Calmodulin

A sequence within the C-terminus of Rin (193–217 aa) and dRic (242–261 aa), but not Rit, has also been shown to permit calmodulin (CaM)-binding [5, 6]. Indeed, Ric was originally isolated in a screen for CaM binding proteins, making CaM the first authenticated Rit family interacting protein [5]. Despite this long history, the contribution of CaM to Rin and dRic function remains poorly characterized (Fig. 3). The CaM binding domain overlaps the polybasic membrane targeting region in Rin [10], although it remains unclear whether CaM association might result in dissociation of Rin or Ric from the plasma membrane. Studies by Hoshino and Nakamura indicate that IQGAP1, an actin binding protein, forms a ternary complex with Rin and CaM [32], and may contribute to Rin-dependent neurite outgrowth in PC12 cells. Interestingly, expression of activated Ric alters wing vein and compound eye development in adult Drosophila [43] and a reduction in endogenous CaM was found to exacerbate these defects, suggesting that calmodulin binding may negatively regulate endogenous Ric function.

3.6 Transcriptional regulation

Ras family proteins play key roles in signal propagation to the nucleus, regulating a range of transcription factors. Transcriptional transactivation reporter assays indicate that Rit is capable of potently stimulating SRF (serum-responsive factor), NFκB (nuclear factor κB), Elk1 [E twenty-six (ETS)-like transcription factor 1], and c-Jun promoters in NIH3T3 cells [26, 27]. Interestingly, both Rit-mediated c-Jun transcriptional activity and NIH 3T3 transformation (see 4.1 below) have been shown to require p38, but not ERK, MAPK signaling [27].

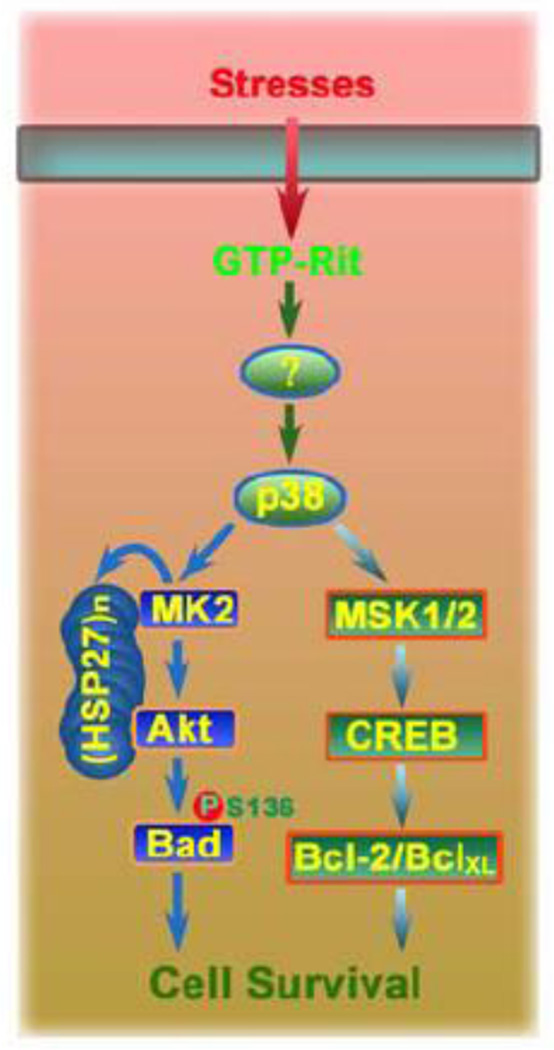

The importance of p38 signaling to Rit-dependent transcriptional control is an emerging theme. Rit signaling contributes to PACAP38-initiated cAMP response element-binding protein (CREB)-mediated transcription in PC6 cells predominantly through regulation of p38 signaling [19], and a recent study identified a critical role for a novel Rit-p38-MSK1/2 pathway in stress-mediated CREB activation [44] (Fig. 4). RNAi-mediated Rit silencing, or inhibition of p38 or MSK1/2 kinases, was found to disrupt stress-mediated CREB-dependent transcription, resulting in increased cell death. Furthermore, ectopic expression of active Rit stimulated CREB-Ser133 phosphorylation, to induce expression of the anti-apoptotic Bcl-2 and BclXL proteins, and promote cell survival. These data indicate that Rit-p38-MSK1/2 signaling may play an important role in stress-dependent regulation of CREB-dependent gene expression.

Figure 4. Rit regulates p38-dependent survival signaling.

Rit family GTPases function as critical regulators of an evolutionarily conserved, p38 MAPK-dependent, signaling cascade that functions as an important survival mechanism in cells responding to environmental stress. Rit-p38 pro-survival signaling has been shown to involve MK2-HSP27-Akt and MSK1/2-CREB pathways, which in part control Bcl-2 family proteins to promote survival.

Transcriptional reporter analysis has also been used to explore Rin-mediated gene expression. Importantly, as opposed to Rit, these studies to date have failed to identify a role for Rin in Elk-1, NFκB, SRF, or c-Jun promoter regulation [26]. However, GDP-bound Rin has been found to interact with the N-terminus of the Brn-3a transcription factor, and gene reporter assays suggest that Rin binding stimulates Brn 3a-mediated transactivation of the egr-1 promoter [45]. In keeping with these binding studies, egr-1 promoter transcription is upregulated by wild-type, but not by expression of constitutively active, GTP-bound Rin. Additional studies are needed to determine the physiological importance of Rin to the regulation of Brn3a-regulated genes.

4. Rit subfamily-mediated cellular functions

Ras-related small GTP-binding proteins function as molecular switches to control a wide range of physiological processes through the regulation of diverse effector pathways. While the regulatory role of many Ras family GTPases is well established, there are a large number of “orphan” GTPases, whose physiological functions remain to be determined [1]. This is particularly true within the Ras branch, in which structurally related GTPase proteins, despite often sharing common downstream effector targets and overlapping regulatory modulators, have been found to perform non-redundant cellular functions [4, 46]. A series of recent genetic linkage studies and the creation of knockout mouse and Drosophila models have begun to define the physiological function for Rit family GTPases.

4.1 Cellular transformation

The role for Ras GTPases in carcinogenesis is well established. Mutational activation of Ras occurs in ~20% of human cancers, resulting in stabilization of the mutant protein in its constitutively active GTP-bound conformation [47]. As the number of Ras-related GTPases has expanded, studies have shown that while not mutated in human cancer, a number of Ras-related proteins can mimic the transforming and differentiating capabilities of oncogenic Ras [4]. Some of the earliest studies to suggest that Rit and Rin regulate distinct biological functions involved analysis of their roles in growth control and transformation. NIH3T3 cells expressing active Rit, but not Rin, display enhanced proliferation rates, proliferation under conditions of growth factor deprivation, anchorage-independent growth as shown by soft agar colony formation, and tumorigenicity in nude mice [26, 27]. These properties are shared with by all members of the Ras (H-, N-, and K-Ras) and R-Ras subfamilies (R-Ras, TC21, and M-Ras) [4]. However, while activated Ras and R-Ras GTPases direct primary foci formation, neither Rit nor Rin induces morphologically transformed NIH3T3 cells. Instead, Rit and Rin cooperate with other oncogenes to enhance foci formation [26]. In addition, recent studies suggest that Rit-mediated transformation requires p38 rather than ERK activation, which is opposite to that seen with Ras [27], supporting the notion that Rit stimulates proliferative pathways that are distinct from those regulated by other Ras family GTPases. Importantly, increased Rit expression is associated with metastatic leiomyosarcomas [48], and the RIT1 gene was found to be amplified or mutated in hepatocellular carcinoma, with amplification correlated with significantly reduced survival rates in patients [49]. Together these data suggest that dysregulated Rit signaling may play an important role in tumor development and progression, and additional studies are warranted to explore its involvement in cancer.

4.2 Neurotrophic signaling and differentiation

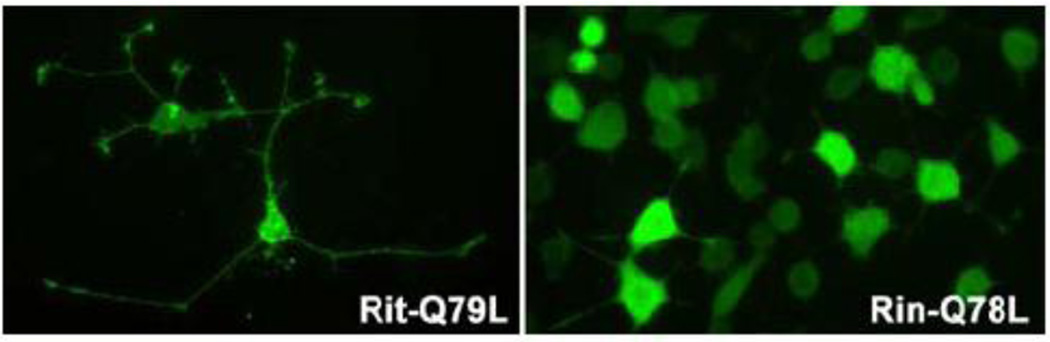

Pheochromocytoma cells respond to the expression of activated Ras family GTPases by the cessation of cell growth and the extension of axon-like processes [50]. Rit, Rin, and dRic each have the capacity to induce ligand-independent neurite outgrowth in pheochromocytoma cells (Fig. 2) and SHSY5Y cells [31].

Figure 2. Rit subfamily GTPases promote neurite outgrowth in PC6 cells.

Expression of constitutively active Rit (Rit-Q79L) and Rin (Rin-Q78L) is sufficient for the induction of neurite outgrowth. Cells expressing Flag tagged-RitQ79L and -RinQ78L were visualized by anti-Flag immunostaining with FITC-conjugated secondary antibody.

Neuritogenesis has been used to examine Rit family signaling [11, 16, 17, 31, 32, 43, 51] and to identify critical roles for Rit and Rin in NGF- and PACAP38-mediated signaling [11, 13, 16, 17, 19]. As opposed to cellular transformation (see section 4.1), Rin loss results in a more profound inhibition of neurite outgrowth in PC6 cells than does Rit silencing. The marked selective effect of Rin loss on neurotrophin-mediated neurite outgrowth indicates that Rin provides a function that is distinct from Rit, and cannot be compensated for by any other Ras family GTPase. Despite this critical insight, the selective contribution(s) of Rin signaling to neuronal function largely remain poorly defined. However, Rit and Rin have been found to be capable of mobilizing distinct downstream signaling cascades in response to neurotrophin activation. While both Rit and Rin contribute to NGF-mediated activation of ERK- and p38-dependent signaling cascades [11, 16], Rit-dependent p38 activation is required for PACAP38-mediated neurite formation [19], whereas Rin loss inhibits PACAP38-mediated neuronal differentiation without disrupting MAPK signaling. Instead, Rin loss was found to attenuate PACAP38-mediated HSP27 activation by disrupting PKA signaling [13]. While these data suggest that a novel Rin-PKA-HSP27 pathway plays a critical role in PACAP38-mediated differentiation signaling, studies examining the impact of Rin loss on primary neurons are lacking. Thus, the importance of this pathway awaits future investigation.

4.3 Neuronal morphogenesis, autism, and schizophrenia

Neurons extend two distinct classes of neurites, axons and dendrites, each with distinct morphology and functional properties [52]. This cellular polarity underlies directional signaling in neuronal circuits, and a growing literature suggests that the modulation of intracellular signaling cascades, including Ras and Rho subfamily GTPases, represents a mechanism for regulating axonal and dendritic growth [53]. In vivo, the dendritic arbor often undergoes expansion after significant axonal growth has occurred, however, the signaling networks that allow spatiotemporal separation of axonal and dendritic growth remain poorly characterized.

Using two culture models Lein et al. [15] identified a role for Rit in the regulation of neuronal morphogenesis. Hippocampal neurons establish axons and dendrites in a cell-autonomous fashion [54] contrary to sympathetic neurons which form axons but do not develop dendrites in culture unless stimulated with bone morphogenetic protein 7 (BMP7) [55]. Expression of activated Rit was found to enhance axonal growth, but had the opposite effect on dendritic growth, with transfected hippocampal and sympathetic neurons extending fewer and shorter dendrites. The morphogenic effects of active Rit signaling were lost upon blockade of MEK-ERK signaling. This is reminiscent of the contribution of Rit-ERK signaling to Gαo-induced neurite outgrowth in Neuro2a cells [51]. However, MEK inhibition did not alter axonal or dendritic growth in control sympathetic or hippocampal neurons, and additional studies are needed to better elucidate the role of ERK in Rit function. Importantly, expression of a dominant-negative Rit mutant had the opposite effect in primary neurons, blocking axonal growth but promoting dendritic growth [15]. In vivo analysis finds the dendritic growth of newborn hippocampal neurons to be impaired in the dentate gyrus of Rit null mice [34], with immature neurons displaying significantly shortened dendrites and decreased dendritic complexity in Rit−/− mice. The enhancement of dendritic growth generated by disruption of Rit signaling in cultured neurons paralleled the effects of BMP7 exposure, suggesting that BMP7 may act by inhibiting Rit activity. Instead, stimulation of hippocampal neurons with BMP, which enhances dendritic growth [56], increased levels of GTP-bound active Rit [57]. BMP7 also increased GTP-bound Rit levels in PC6 cells [15]. However, in PC6 cells pretreated with NGF, which mirrors sympathetic neuron cultures in which NGF is required for survival [55], subsequent BMP7 exposure resulted in lower levels of active Rit. These findings suggest a model in which cross-talk between BMP- and NGF-mediated signaling cascades might control local Rit signaling to regulate axonal versus dendritic growth in response to local environmental cues. Indeed, Rit has been linked to the regulation of Rac1/Cdc42 and Par/aPKC (see section 3.3) pathways known to be involved in establishing neuronal polarity [58], but whether compartmentalized Rit signaling functions as a critical control element in neuronal morphogenesis awaits further study.

Rit signaling has also been implicated in interferon-γ (IFNγ)-dependent dendritic remodeling [21]. IFNγ stimulates levels of GTP-bound active Rit in hippocampal neurons, and expression of dominant-negative Rit was shown to inhibit IFNγ-induced dendritic retraction in cultured sympathetic and hippocampal neurons [21]. Canonical IFNγ signaling involves activation of the JAK-STAT pathway, whose function is essential for IFNγ-sensitive gene expression [59] and dendritic retraction [60]. Thus, it was surprising that Rit signaling was not required for IFNγ-dependent STAT1 activation. Instead, Rit silencing in pheochromocytoma cells was shown to suppress IFNγ-elicited activation of p38 MAPK signaling, and pharmacological inhibition of p38 signaling significantly attenuated IFNγ-mediated dendritic retraction in sympathetic and hippocampal neurons [21]. Dendritic retraction is critical for synaptic refinement during neurodevelopment and experience-dependent synaptic remodeling, but excessive regression is thought to contribute to the functional defects associated with trauma, neurodegenerative disease, and neurodevelopmental disorders. A recent expression profiling study of the superior temporal cortex identified an increase in RIT1 transcript levels in subjects affected with autism, leading to the suggestion that Rit represents an autism spectrum disorder susceptibility gene [61]. Since abnormal assembly of synapses and dendritic spines are contributing factors in autism’s pathogenesis [62], the involvement of Rit signaling to the regulation of synaptic development and function warrants additional study.

Although the contribution of Rin to neuronal morphology has yet to be examined in vivo, it is noteworthy that several recent studies have suggested that the RIT2 (Rin) gene might be involved in the pathogenesis of schizophrenia. These include a report of a significant enrichment of common interstitial deletions near the RIT2 gene in patients affected with schizophrenia when compared with control subjects [63], and the identification of a family with familial schizophrenia bearing a 18q12.3 duplication, in which the telomeric breakpoint disrupted the RIT2 gene, but no known gene was located within the duplicated region [64]. Importantly, interstitial deletions encompassing band 18q12.3 define the del(18)(q12.2q21.1) syndrome, which is characterized by moderate to severe mental retardation, seizure, language delay, mild dysmorphic features, a lack of major congenital abnormalities, and behavioral problems (i.e., autism spectrum disorder, hyperactivity, aggression)[65–68]. Among the deleted genes in this region, RIT2 was identified as a candidate gene for language delay, mental retardation, and behavioral abnormalities [65]. Although the contribution of Ras to cancer signaling has been most intensively investigated, calcium-mediated Ras activation plays a central role in coupling electrical activity to changes in nervous system development and function [69, 70]. Consistent with the critical role of Ras signaling in neuronal plasticity, mutations within Ras-signaling pathways are associated with diseases causing cognitive and learning deficits [71–73]. A common theme emerging from genome-wide approaches to schizophrenia is the identification of genes involved in calcium-signaling, synaptic regulation, and synaptic development. When the identification of Rin as a putative contributor to the genetic susceptibility of schizophrenia is considered along with its limited neuronal pattern of expression [5, 6], known contributions to neurotrophin-mediated differentiation [11, 13, 32], and potential to be regulated in a calcium/calmodulin-dependent fashion [43], it is clear that additional in vivo functional studies are necessary to assess the biological effects of Rin signaling within the CNS.

4.4 Regulation of dopamine (DA) transporter

Dopaminergic signaling plays critical roles in the regulation of movement and cognition. Presynaptic reuptake of dopamine controls extracellular dopamine (DA) levels, with the dopamine transporter (DAT) serving as a primary mechanism for terminating DA signaling [74]. Because of this central regulatory function [75], DAT function plays a critical role in neuropsychiatric disorders, including autism. DAT activity is down-regulated by protein kinase C (PKC) signaling, with a domain within the DAT C-terminus contributing to basal and PKC-stimulated internalization [76]. Rin was recently identified as a protein that interacts with the DAT C-terminal endocytic domain [77]. Importantly, PKC-mediated DAT internalization was attenuated following RNA-mediated Rin silencing, supporting a role for Rin signaling in the regulation of DAT trafficking. In light of these findings, it is interesting that a recent report identified Rin as being significantly enriched in dopaminergic neurons [78]. Furthermore, genome-wide association methods have identified Rin as a gene associated with Parkinson’s disease susceptibility [79, 80] with Rin expression significantly reduced in the substantia nigra of PD patients [80, 81]. Whether this putative disease link arises from the ability of Rin to regulate DAT trafficking, and therefore govern dopamine levels, awaits further investigation.

4.5 Cell survival

Cells mobilize diverse signaling cascades following stress exposure to protect against injury. Ras family GTPases play critical roles in this process, controlling the activation and integration of signaling pathways capable of promoting either cell survival or death [29, 30, 82–84]. In keeping with a role for Rit in survival signaling, one of the earliest reports of biological function found that active Rit conferred cellular resistance to serum-withdrawal-induced death in both PC6 cells and sympathetic neurons [17]. Subsequent studies in PC6 cells have described a more general protective role for Rit signaling in response to an array of stresses, and have shown that Rit silencing renders cells susceptible to stress-dependent apoptosis [18, 44]. Importantly, these same stresses stimulate Rit activation, further supporting a role for Rit signaling as a crucial survival mechanism in response to stress [18]. To date, Rit-mediated protection has been found to rely predominantly on p38 MAPK signaling, including p38-dependent activation of both Akt- and CREB-dependent survival signaling pathways (see Section 3.2), with blockade of either cascade inhibiting Rit-dependent stress protection [18, 22, 44]. Together, these studies suggest that Rit signaling plays a central role in determining whether stress-mediated p38 activation results in cell death or recovery (Fig. 3) [18, 44].

The recent generation of both knockout and transgenic Rit family GTPase genetic models has provided additional insight into the role of Rit survival signaling. The restricted number of small Ras-related GTPases expressed in Drosophila has made it a valuable model for analyzing the physiological roles of Ras superfamily G-proteins, and D-Ric null flies were generated to address the physiological function of Ric signaling. D-RIC null Drosophila are viable, fertile, and display no apparent defects in patterning or apoptosis in developing embryonic or larval tissues, indicating that Ric signaling does not play an essential role during development [33]. However, adult D-RIC null flies display reduced resistance to a variety of environmental stresses, suggesting an evolutionarily conserved role for Rit subfamily GTPases in stress response signaling [33]. Earlier studies had found that D-p38a knockout flies shared a similar sensitivity to stress without observable developmental defects, leading to studies showing that p38 signaling is impaired in D-RIC null flies in response to heat shock [33]. Together, these studies provide genetic evidence that RIC signaling promotes survival in response to cellular stress in a fashion that relies upon p38 and cannot be compensated for by other Drosophila Ras family GTPases.

Consistent with the notion that Rit subfamily GTPase function is not required for proliferation, Rit−/− mice are born without any gross morphological or anatomical defects, indicating that Rit is not essential for embryonic development in mice. However, embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) derived from Rit−/− embryos display a selective vulnerability to oxidative stress, without altering cell survival following endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-stress or DNA damage [33], supporting the idea that other Ras family GTPases cannot compensate for the loss of Rit in survival signaling. The increase in apoptosis coincided with a selective disruption in ROS-mediated stimulation of the pro-survival p38-MK2-HSP27-Akt signaling cascade [18, 33]. Supporting this finding is the recent characterization of a transgenic mouse model with restricted overexpression of active Rit to postnatal neurons [85]. Rit was found to confer dramatically increased oxidative stress resistance to both hippocampal and cortical neurons in a p38-dependent manner. Notably, Rit has also been identified as a critical player in the survival of immature hippocampal neurons following brain injury [34]. While, hippocampal development is not disrupted in Rit null mice, Rit−/− hippocampal neural cultures display increased cell death and blunted p38 MAPK and Akt activation in response to oxidative stress, without affecting brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF)-dependent MAPK signaling. When compared to wild-type hippocampal cultures, Rit loss rendered immature neurons sensitive to oxidative damage, without altering the survival of neural progenitor cells. In keeping with previous studies demonstrating that traumatic brain injury (TBI) results in the selective death of immature hippocampal neurons, Rit−/− mice exhibited a significantly greater loss of adult-born immature neurons within the dentate gyrus following TBI [34]. Taken together, gene-targeting studies reveal an evolutionarily conserved, and critical, pro-survival function for the Rit-p38 cascade in cells adapting to oxidative stress.

5. Conclusions

The conservation from flies to humans first implied an evolutionarily conserved function for the Rit subfamily proteins. Recent studies using cell culture systems and investigations with transgenic models have allowed significant progress to be made regarding the cellular function of this novel GTPase subfamily, including the realization that convergent extracellular stimuli cause activation of both Ras and Rit GTPases, and the identification of critical roles for Rit-dependent signaling in the regulation of proliferation, neuronal morphogenesis, and cell survival. Despite these insights, the cellular function of Rit and Rin remains elusive, and the molecular identity of Rit subfamily GEFs and GAPs remains largely unknown. Our understanding of Rit signal transduction continues to evolve, but it is now appreciated that Rit proteins can activate diverse signaling pathways through their interaction with an expanding number of effector proteins. These include unique regulatory roles for Rit GTPases in the control of cellular MAPK cascades and evidence that Rit signaling networks also facilitate interactions with other Ras-like GTPases, including both Ral and Rho family GTPases. Current understanding of Rin-dependent signaling trails that of Rit, and generation of Rin knockout models is needed to address this knowledge gap. Although Rit and Rin are regulators of cell proliferation and differentiation, the degree to which they overlap with Ras protein function remains an area of active research, and focused studies are needed to identify Rit/Rin-specific effector cascades. The importance of this work is highlighted by recent human genome-wide association studies implicating Rit and Rin signaling in disorders from Parkinson’s disease, to autism, and schizophrenia. Whether aberrant Rit/Rin function contributes to these neurological disorders remains to be addressed. In summary, despite recent advances in the delineation of Rit subfamily-mediated signaling, a greater understanding of the mechanism of Rit activation and the intricacies of Rit-dependent signaling networks are future challenges needed to define the physiological functions of this novel Ras GTPase subfamily.

Table 1.

Rit subfamily G proteins-associated effectors

| Accessory Effector | Rit | Rin | by mean | Effects | Authors and References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AF6 | + | + | y2b | ND | Shao [7] |

| RalGDS-RID | + | + | y2b | ND | Shao [7] |

| Rlf | + | + | y2b | ND | Shao [7] |

| RGL3 | + | − | y2b; i.p. | RalA activation | Shao [28] |

| Calmodulin | − | + | y2b; i.p. | Neurite outgrowth | Wes [5]; Hoshino [32]; Lee [6] |

| Rac | ND | + | p.d. | Transformation | Hoshino [32] |

| Cdc42 | ND | + | p.d. | Transformation | Hoshino [32] |

| Par6 | + | + | i.p.; p.d. | Transformation | Rudolph [41]; Hoshino [39] |

| B-Raf | + | + | i.p.; p.d. | Neurite outgrowth | Shi [11, 16] |

| C-Raf | + | + | i.p.; p.d. | not activated by Rit/Rin | Shi [11, 16] |

| p38 MAPK | + | ND | i.p.; p.d. | Neurite outgrowth; cell survival | Shi [18] |

| MK2 | + | ND | i.p. | Cell survival | Shi [18] |

| HSP27 | + | ND | i.p. | Cell survival | Shi [18] |

| Akt | + | ND | i.p. | Cell survival | Shi [18] |

| SOS | ND | + | i.p. | ND | Hoshino [12] |

| PIP lipids | + | + | binding | Membrane anchoring | Heo [10] |

+, positive association; −, lack of interaction; i.p., immunoprecipitation; p.d., GST-pulldown; ND, not determined; RGL3, RalGDS-like 3; y2b, yeast two hybrid

Highlights.

Rit is ubiquitously expressed while the closely related Rin GTPase is expressed in neurons

Rit and Rin are activated in response to diverse stimuli including mitogens and cellular stresses

Rit and Rin regulate diverse signaling pathways, sharing overlapping and distinct cellular effectors with Ras

Rit controls neuronal morphogenesis, promotes survival in cells adapting to stress, and has been implicated in cancer.

Rin function remains poorly characterized but the RIT2 gene has been linked to schizophrenia, autism, and Parkinson’s disease

Acknowledgements

We apologize to the scientists whose work was not cited due to space constraints. Research by the authors was supported by Public Health Service Grant NS045103 from National Institute of Neurological Diseases and Stroke (NINDS) (DAA), 2P20 RR020171 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR) (DAA), KSCHIRT 12-1A from the Kentucky Spinal Cord and Head Injury Research Trust (DAA), and the University of Kentucky 2012–2013 Research Professorship (DAA). The content of this article is the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Abbreviations

- CA

constitutively active

- cAMP

cyclic adenosine monophosphate

- CaM

Calmodulin

- CCI

controlled cortical impact

- CREB

cAMP response element binding protein

- CRIB

Cdc42/Rac interactive binding

- DA

dopamine

- DAT

dopamine transporter

- DN

dominant negative

- EGF

epidermal growth factor

- ERK

extracellular-signal regulated protein kinase

- GAP

GTPase activating protein

- GTPase

guanosine triphosphatase

- Epac

exchange protein directly activated by cAMP

- GEF

guanine nucleotide exchange factor

- GPCR

G protein coupled receptor

- HSP27

heat shock protein 27

- IFNγ

interferon-γ

- JNK

c-jun N-terminal protein kinase

- MAPK

mitogen-activated protein kinase

- MEFs

mouse embryonic fibroblasts

- MK2

MAPK-activated protein kinase 2 (MAPKAPK2)

- MKK

MAPK kinase (also MAP2K)

- MSK1/2

mitogen- and stress-activated protein kinase 1/2

- NGF

nerve growth factor

- PACAP38

pituitary adenylate cyclase activated polypeptide 38

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- PI3K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- PKA

protein kinase A

- PKC

protein kinase C

- PMA

phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate

- RGL3

RalGDS-like 3

- Ric

Ras-related protein which interacted with calmodulin

- Rin

Ric (Ras)-related gene expressed in neural tissues

- Rit

Ric (Ras)-related gene expressed throughout the organism

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

- RTK

receptor tyrosine kinase

- SOS

son of sevenless

- TBI

traumatic brain injury

- TNFα

tumor necrosis factor α

- TrkA

tropomyosin receptor kinase A

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Colicelli J. Sci STKE. 2004;2004:RE13. doi: 10.1126/stke.2502004re13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wennerberg K, Rossman KL, Der CJ. Journal of cell science. 2005;118:843–846. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rojas AM, Fuentes G, Rausell A, Valencia A. The Journal of cell biology. 2012;196:189–201. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201103008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Reuther GW, Der CJ. Current opinion in cell biology. 2000;12:157–165. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)00071-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wes PD, Yu M, Montell C. The EMBO journal. 1996;15:5839–5848. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lee CH, Della NG, Chew CE, Zack DJ. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 1996;16:6784–6794. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-21-06784.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shao H, Kadono-Okuda K, Finlin BS, Andres DA. Archives of biochemistry and biophysics. 1999;371:207–219. doi: 10.1006/abbi.1999.1448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spencer ML, Shao H, Tucker HM, Andres DA. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:17605–17615. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111400200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ahearn IM, Haigis K, Bar-Sagi D, Philips MR. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2012;13:39–51. doi: 10.1038/nrm3255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heo WD, Inoue T, Park WS, Kim ML, Park BO, Wandless TJ, Meyer T. Science. 2006;314:1458–1461. doi: 10.1126/science.1134389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shi GX, Han J, Andres DA. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:37599–37609. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M507364200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoshino M, Nakamura S. Biochemical and biophysical research communications. 2002;295:651–656. doi: 10.1016/s0006-291x(02)00731-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shi GX, Jin L, Andres DA. Molecular and cellular biology. 2008;28:4940–4951. doi: 10.1128/MCB.02193-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wolthuis RM, Bos JL. Current opinion in genetics & development. 1999;9:112–117. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(99)80016-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lein PJ, Guo X, Shi GX, Moholt-Siebert M, Bruun D, Andres DA. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2007;27:4725–4736. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5633-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shi GX, Andres DA. Molecular and cellular biology. 2005;25:830–846. doi: 10.1128/MCB.25.2.830-846.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spencer ML, Shao H, Andres DA. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2002;277:20160–20168. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201092200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shi GX, Jin L, Andres DA. Molecular and cellular biology. 2011;31:1938–1948. doi: 10.1128/MCB.01380-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi GX, Rehmann H, Andres DA. Molecular and cellular biology. 2006;26:9136–9147. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00332-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shi GX, Jin L, Andres DA. Molecular biology of the cell. 2010;21:1597–1608. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-12-1033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andres DA, Shi GX, Bruun D, Barnhart C, Lein PJ. Journal of neurochemistry. 2008;107:1436–1447. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2008.05708.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cai W, Rudolph JL, Harrison SM, Jin L, Frantz AL, Harrison DA, Andres DA. Molecular biology of the cell. 2011;22:3231–3241. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-05-0400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cherfils J, Zeghouf M. Physiol Rev. 2013;93:269–309. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00003.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sasagawa S, Ozaki Y, Fujita K, Kuroda S. Nature cell biology. 2005;7:365–373. doi: 10.1038/ncb1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stork PJ. Nature cell biology. 2005;7:338–339. doi: 10.1038/ncb0405-338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rusyn EV, Reynolds ER, Shao H, Grana TM, Chan TO, Andres DA, Cox AD. Oncogene. 2000;19:4685–4694. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sakabe K, Teramoto H, Zohar M, Behbahani B, Miyazaki H, Chikumi H, Gutkind JS. FEBS letters. 2002;511:15–20. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03264-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shao H, Andres DA. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2000;275:26914–26924. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002241200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McKay MM, Morrison DK. Oncogene. 2007;26:3113–3121. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1210394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Frebel K, Wiese S. Biochemical Society transactions. 2006;34:1287–1290. doi: 10.1042/BST0341287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hynds DL, Spencer ML, Andres DA, Snow DM. Journal of cell science. 2003;116:1925–1935. doi: 10.1242/jcs.00401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoshino M, Nakamura S. The Journal of cell biology. 2003;163:1067–1076. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200308070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cai W, Rudolph JL, Harrison SM, Jin L, Frantz AL, Harrison DA, Andres DA. Molecular biology of the cell. 2011;22:3231–3241. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E11-05-0400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cai W, Carlson SW, Brelsfoard JM, Mannon CE, Moncman CL, Saatman KE, Andres DA. J Neurosci. 2012;32:9887–9897. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0375-12.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wu R, Kausar H, Johnson P, Montoya-Durango DE, Merchant M, Rane MJ. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2007;282:21598–21608. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611316200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rane MJ, Pan Y, Singh S, Powell DW, Wu R, Cummins T, Chen Q, McLeish KR, Klein JB. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2003;278:27828–27835. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M303417200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rane MJ, Coxon PY, Powell DW, Webster R, Klein JB, Pierce W, Ping P, McLeish KR. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2001;276:3517–3523. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M005953200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zheng C, Lin Z, Zhao ZJ, Yang Y, Niu H, Shen X. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2006;281:37215–37226. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M603622200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hoshino M, Yoshimori T, Nakamura S. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2005;280:22868–22874. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M411592200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ivarsson Y. FEBS letters. 2012;586:2638–2647. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2012.04.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Rudolph JL, Shi GX, Erdogan E, Fields AP, Andres DA. Biochimica et biophysica acta. 2007;1773:1793–1800. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2007.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ferro E, Trabalzini L. Cellular signalling. 2010;22:1804–1810. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2010.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Harrison SM, Rudolph JL, Spencer ML, Wes PD, Montell C, Andres DA, Harrison DA. Developmental dynamics : an official publication of the American Association of Anatomists. 2005;232:817–826. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.20346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Shi GX, Cai W, Andres DA. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2012;287:39859–39868. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.384248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Calissano M, Latchman DS. Oncogene. 2003;22:5408–5414. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Raaijmakers JH, Bos JL. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2009;284:10995–10999. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R800061200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pylayeva-Gupta Y, Grabocka E, Bar-Sagi D. Nat Rev Cancer. 2011;11:761–774. doi: 10.1038/nrc3106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee YF, John M, Falconer A, Edwards S, Clark J, Flohr P, Roe T, Wang R, Shipley J, Grimer RJ, Mangham DC, Thomas JM, Fisher C, Judson I, Cooper CS. Cancer research. 2004;64:7201–7204. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Li JT, Liu W, Kuang ZH, Zhang RH, Chen HK, Feng QS. Zhonghua yi xue yi chuan xue za zhi = Zhonghua yixue yichuanxue zazhi = Chinese journal of medical genetics. 2004;21:43–46. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Greene LA, Tischler AS. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 1976;73:2424–2428. doi: 10.1073/pnas.73.7.2424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Kim SH, Kim S, Ghil SH. Neuroreport. 2008;19:521–525. doi: 10.1097/WNR.0b013e3282f9e473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Craig AM, Banker G. Annu Rev Neurosci. 1994;17:267–310. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ne.17.030194.001411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Barnes AP, Polleux F. Annu Rev Neurosci. 2009;32:347–381. doi: 10.1146/annurev.neuro.31.060407.125536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dotti CG, Sullivan CA, Banker GA. J Neurosci. 1988;8:1454–1468. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.08-04-01454.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Lein P, Johnson M, Guo X, Rueger D, Higgins D. Neuron. 1995;15:597–605. doi: 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90148-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Withers GS, Higgins D, Charette M, Banker G. Eur J Neurosci. 2000;12:106–116. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2000.00889.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Lein PJ, Guo X, Shi GX, Moholt-Siebert M, Bruun D, Andres DA. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2007;27:4725–4736. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5633-06.2007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Arimura N, Kaibuchi K. Neuron. 2005;48:881–884. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Platanias LC. Nature reviews. 2005;5:375–386. doi: 10.1038/nri1604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kim IJ, Drahushuk KM, Kim WY, Gonsiorek EA, Lein P, Andres DA, Higgins D. J Neurosci. 2004;24:3304–3312. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3286-03.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Garbett K, Ebert PJ, Mitchell A, Lintas C, Manzi B, Mirnics K, Persico AM. Neurobiol Dis. 2008;30:303–311. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Ebert DH, Greenberg ME. Nature. 2013;493:327–337. doi: 10.1038/nature11860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Glessner JT, Reilly MP, Kim CE, Takahashi N, Albano A, Hou C, Bradfield JP, Zhang H, Sleiman PM, Flory JH, Imielinski M, Frackelton EC, Chiavacci R, Thomas KA, Garris M, Otieno FG, Davidson M, Weiser M, Reichenberg A, Davis KL, Friedman JI, Cappola TP, Margulies KB, Rader DJ, Grant SF, Buxbaum JD, Gur RE, Hakonarson H. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2010;107:10584–10589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1000274107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Liao HM, Chao YL, Huang AL, Cheng MC, Chen YJ, Lee KF, Fang JS, Hsu CH, Chen CH. Schizophrenia research. 2012;139:229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2012.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bouquillon S, Andrieux J, Landais E, Duban-Bedu B, Boidein F, Lenne B, Vallee L, Leal T, Doco-Fenzy M, Delobel B. European journal of medical genetics. 2011;54:194–197. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmg.2010.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Buysse K, Menten B, Oostra A, Tavernier S, Mortier GR, Speleman F. American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 2008;146A:1330–1334. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cody JD, Sebold C, Malik A, Heard P, Carter E, Crandall A, Soileau B, Semrud-Clikeman M, Cody CM, Hardies LJ, Li J, Lancaster J, Fox PT, Stratton RF, Perry B, Hale DE. American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 2007;143A:1181–1190. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Feenstra I, Vissers LE, Orsel M, van Kessel AG, Brunner HG, Veltman JA, van Ravenswaaij-Arts CM. American journal of medical genetics. Part A. 2007;143A:1858–1867. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Finkbeiner S, Greenberg ME. Neuron. 1996;16:233–236. doi: 10.1016/s0896-6273(00)80040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ye X, Carew TJ. Neuron. 2010;68:340–361. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Schubbert S, Shannon K, Bollag G. Nat Rev Cancer. 2007;7:295–308. doi: 10.1038/nrc2109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Thomas GM, Huganir RL. Nature reviews. Neuroscience. 2004;5:173–183. doi: 10.1038/nrn1346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Tidyman WE, Rauen KA. Current opinion in genetics & development. 2009;19:230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.gde.2009.04.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Giros B, Jaber M, Jones SR, Wightman RM, Caron MG. Nature. 1996;379:606–612. doi: 10.1038/379606a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Eriksen J, Jorgensen TN, Gether U. J Neurochem. 2010;113:27–41. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2010.06599.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Holton KL, Loder MK, Melikian HE. Nature neuroscience. 2005;8:881–888. doi: 10.1038/nn1478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Navaroli DM, Stevens ZH, Uzelac Z, Gabriel L, King MJ, Lifshitz LM, Sitte HH, Melikian HE. The Journal of neuroscience : the official journal of the Society for Neuroscience. 2011;31:13758–13770. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2649-11.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Zhou Q, Li J, Wang H, Yin Y, Zhou J. Neurobiology of aging. 2011;32:313–326. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2009.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Latourelle JC, Dumitriu A, Hadzi TC, Beach TG, Myers RH. PloS one. 2012;7:e46199. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0046199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Pankratz N, Beecham GW, DeStefano AL, Dawson TM, Doheny KF, Factor SA, Hamza TH, Hung AY, Hyman BT, Ivinson AJ, Krainc D, Latourelle JC, Clark LN, Marder K, Martin ER, Mayeux R, Ross OA, Scherzer CR, Simon DK, Tanner C, Vance JM, Wszolek ZK, Zabetian CP, Myers RH, Payami H, Scott WK, Foroud T, Consortium PG. Annals of neurology. 2012;71:370–384. doi: 10.1002/ana.22687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Bossers K, Meerhoff G, Balesar R, van Dongen JW, Kruse CG, Swaab DF, Verhaagen J. Brain Pathol. 2009;19:91–107. doi: 10.1111/j.1750-3639.2008.00171.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Reichardt LF. Philosophical transactions of the Royal Society of London. Series B, Biological sciences. 2006;361:1545–1564. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2006.1894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Cox AD, Der CJ. Oncogene. 2003;22:8999–9006. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Takeda K, Ichijo H. Genes to cells : devoted to molecular & cellular mechanisms. 2002;7:1099–1111. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.2002.00591.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Cai W, Rudolph JL, Sengoku T, Andres DA. Neuroscience letters. 2012;531:125–130. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2012.10.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]