Abstract

Secondary amines undergo redox-neutral reactions with aminobenzaldehydes under conventional and microwave heating to furnish polycyclic aminals via amine α-amination/N-alkylation. This unique α-functionalization reaction proceeds without the involvement of transition metals or other additives. The resulting aminal products are precursors for various quinazolinone alkaloids and their analogues.

Keywords: C–H bond functionalization, Redox Isomerization, Aminals, Quinazolinone alkaloids, Friedländer condensation

Introduction

The transformation of simple amines into value-added building blocks via α-C–H bond functionalization remains an active area of research.1 While the majority of current approaches are oxidative in nature, redox-neutral2 methods offer an attractive alternative. Perhaps the earliest example of a non-oxidative α-functionalization of an amine can be traced back to Pinnow who in 1895 reported the unusual reaction outlined in Scheme 1.3 Exposure of nitroaniline 1 to reducing conditions provided benzimidazole 3 in addition to the expected diamine 2. Product 3 results from the functionalization of a methyl group, presumably via intramolecular H-transfer to an intermediate nitroso compound.

Scheme 1.

Examples of amine α-amination via C–H bond functionalization.

Reactions of this type in which a tertiary amine undergoes functionalization in α-position were later classified under the term tert-amino effect. Several reviews on this topic have appeared.4 Other classic examples of the tert-amino effect that lead to amine α-amination are shown in Scheme 1. Meth-Cohn et al. reported the acid catalyzed isomerization of imines 4 to dihydrobenzimidazoles 5, species that readily air-oxidize to the corresponding benzimidazolium salts.5 This interesting rearrangement is thought to proceed via a 1,6-hydride transfer from an amine α-C–H bond to an iminium ion. Reinhoudt and coworkers, in addition to many other key contributions,6 reported the thermal rearrangement of imine 6 to aminal 7.6b This reactions involves a 1,5-hydride shift/ring closure sequence. Akiyama et al.7 and our group8 independently reported the Brønsted acid catalyzed formation of aminals related to 7 by employing a one pot cascade strategy starting form primary amines and tertiary ortho-aminobenzaldehydes. In addition to standard condensation based approaches to aminals,9 a number of oxidative amine α-aminations have also been reported.10

Our interest in the area of C–H functionalization was sparked by an unexpected discovery. In the course of performing Friedländer reactions11 to prepare a number of quinolines, we observed the formation of an interesting pyrrolidine-containing byproduct. Specifically, the supposedly innocent base pyrrolidine was found to undergo an unexpected reaction with ortho-aminobenzaldehyde 8a to form aminal 9a under mild conditions (Scheme 2). In this process, an amine α-C–H bond is replaced by a C–N bond, concomitant with a reductive N-alkylation of the amine.12–14 Here we provide a full account of this process, along with the application to the synthesis of several quinazolinone alkaloids.

Scheme 2.

Serendipitously discovered redox-neutral formation of aminals.

Reaction Development

Following our initial discovery, the condensation of pyrrolidine and ortho-aminobenzaldehydes was evaluated under a range of conditions. Alcoholic solvents, in particular ethanol, provided better results than solvents such as toluene, DMF, THF and acetonitrile. An excess amount of pyrrolidine proved beneficial to shorten reaction times while the use of pyrrolidine as solvent led to inferior results. Under optimized reaction conditions, a range of aminobenzaldehydes was allowed to react with three equivalents of pyrrolidine in ethanol under reflux (Scheme 3). Various aminobenzaldehydes with different substitution patterns and electronic properties proved to be suitable substrates, providing products in generally good yields. Electron-poor aminobenzaldehydes were found to be particularly reactive, whereas more electron-rich substrates furnished products in good yields after somewhat prolonged reaction times. Heterocyclic aminoaldehydes gave ring-fused aminals in excellent yields. An ethyl substituent on the nitrogen atom of the aminobenzaldehyde was tolerated.

Scheme 3.

Reactions of pyrrolidine with various ortho-aminobenzaldehydes.

The aminal formation was also explored with regard to amines other than pyrrolidine (Scheme 4). Interestingly, piperidine gave very little conversion under the original reaction conditions (reflux in ethanol). However, a reaction of piperidine and aminobenzaldehyde 8c performed in a sealed tube at 140 °C led to a reasonable conversion to product. Even under these more forcing conditions, morpholine proved to be a poor substrate. Azepane showed a higher reactivity than piperidine, and azocane was found to be reactive enough to undergo the reaction under the original reflux conditions. Cyclic amines with benzylic α-C–H bonds such as tetrahydroisoquinoline (THIQ) were identified as highly reactive substrates, typically providing good yields of aminal products. Notably, shortly after our initial communication on these results, Dang and Bai independently reported a related procedure with ortho-phenylthio-ortho-amino pyrimidinealdehyde.15

Scheme 4.

Reactions of ortho-aminobenzaldehydes with various cyclic amines.

Several of the aminal products were characterized by X-ray crystallography (Figure 1). Interestingly, the pyrrolidine-derived aminal 9c exhibits a bent structure whereas piperidine-based aminal 10a adopts a relatively planar conformation.

Figure 1.

Top and side views of the X-ray crystal structures of 9c (left) and 10a (right).

Reaction Mechanism

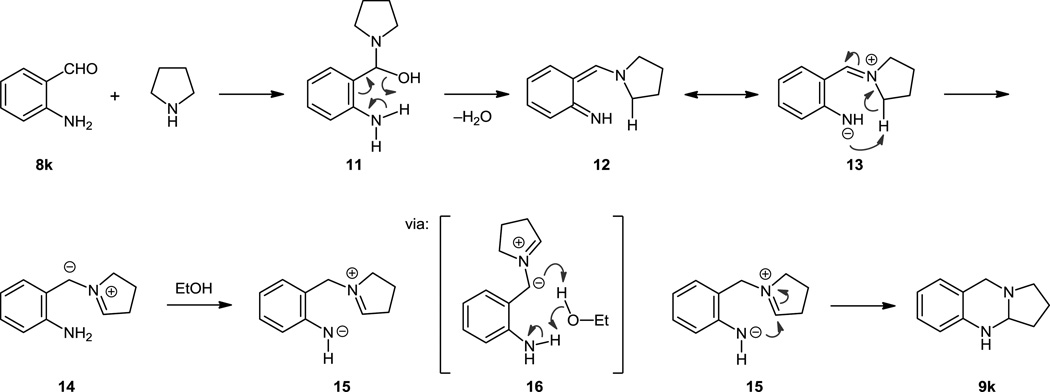

In collaboration with the Houk group, we have recently performed a combined computational and experimental study to delineate the mechanism of the aminal formation.12c Density functional theory calculations revealed a partially unexpected reaction pathway. Perhaps the most surprising finding is that simple iminium ions are most likely not involved in the overall process. The lowest energy pathway for aminal formation is outlined in Scheme 5, exemplified in the prototypical reaction of unsubstituted aminobenzaldehyde 8k and pyrrolidine. In the first step, 8k and pyrrolidine react to form N,O-acetal 11. Rather than fragmenting into an iminium ion as originally assumed, 11 undergoes elimination of water via a six-membered transition state with participation of the NH2-group to directly form ortho-azaquinonemethide 12. Natural population analysis of 12 indicated a significant contribution from a zwitterionic resonance-structure 13 with a negative charge on the aniline nitrogen and an iminium ion at the heterocycle, restoring the aromaticity of the system. The rate determining step of the overall transformation is the rearrangement of azaquinonemethide 12/13 to azomethine ylide 14 via 1,6-proton abstraction. The alternative 1,6-hydride transfer process was ruled out. Another proton transfer step follows, converting azomethine ylide 14 to zwitterion 15. Interestingly, ethanol acts as a proton-shuttle in this instance (via 16). Ultimately, zwitterion 15 collapses into product 9k. Support for this computationally derived mechanism was obtained from various deuterium-labeling studies and trapping of azaquinonemethide and azomethine ylide intermediates (vide infra).

Scheme 5.

Mechanism of the aminal formation.

Reaction Optimization Under Microwave Conditions

Following our original publication, Polshettiwar and Varma reported the use of microwave irradiation to accelerate the formation of aminals from secondary amines and ortho-aminobenzaldehydes.16 According to these authors, the reaction is best performed under solvent-free conditions with 4 equivalents of the cyclic amine. Specifically, reaction times between 40–60 min at 130 °C were reported to give rise to good yields of product. Surprisingly, the same reaction conditions are purportedly applicable to a broad range of substrates, including cyclic amines such as pyrrolidine, piperidine and morpholine, substrates that we had found to exhibit vastly different reactivities. In our hands, the findings by Polshettiwar and Varma were largely irreproducible. Our own efforts to identify efficient microwave conditions are the subject of the following discussion.

Morpholine, a substrate that was previously shown to exhibit poor reactivity under conventional heating conditions was selected for performance optimization under microwave irradiation. Specifically, the reaction of aminobenzaldehyde 8c with morpholine to give aminal 10b was investigated under a variety of conditions (Table 1). No reaction was observed when the reaction was conducted with four equivalents of morpholine under neat conditions at 130 °C (entry 1). This reaction was also performed in the presence of a silicon carbide heating element (HE) under otherwise identical conditions (entry 2). While no change was observed in this instance, we have found previously that the presence of a HE can dramatically impact the outcome of related reactions.13 Typically, improved substrate conversions are observed in the presence of a HE even at the same bulk temperature. Curiously, Polshettiwar and Varma reported the formation of 10b in 65% yield under the conditions in entry 1, although it is not clear whether or not a HE was used. Microwave instrument calibration can certainly affect reaction outcomes and differences in yields are to be expected among different instruments, even when the exact same settings are used. However, we found that even when the title reaction was conducted under neat conditions at 200 °C for one hour in presence of a HE, the conversion remained low and only 16% of aminal 10b was formed (entry 3). A further increase in reaction temperature to 250 °C proved detrimental as decomposition was found to dominate under these conditions. As in conventional heating, the addition of alcoholic solvents led to superior results over the neat reaction conditions, a finding that is consistent with the reaction mechanism and the role of solvent as a proton shuttle (see structure 16 in Scheme 5). Relatively drastic reaction conditions were required to obtain a reasonable amount of morpholine-containing aminal 10b. This product was obtained in 49% yield following a reaction time of 60 min at 270 °C. A HE was used in all subsequent reactions that were performed under microwave irradiation.

Table 1.

Optimization of reaction conditions for morpholine, a relatively unreactive amine.

| |||||

| Entry | Solvent (concentration) | HEa | Temperature [°C] |

Time [min] |

Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | - | no | 130 | 45 | NR |

| 2 | - | yes | 130 | 45 | NR |

| 3b | - | yes | 200 | 60 | 16 |

| 4 | - | yes | 250 | 60 | tracec |

| 5 | EtOH (2 M) | no | 130 | 60 | NR |

| 6 | n-BuOH (2 M) | yes | 130 | 60 | NR |

| 7 | n-BuOH (0.5 M) | yes | 130 | 60 | NR |

| 8b | PhMe (2 M) | no | 200 | 45 | 6 |

| 9b | n-BuOH (0.5 M) | yes | 200 | 45 | 20 |

| 10b | n-BuOH (0.25 M) | no | 200 | 45 | 14 |

| 11b | n-BuOH (0.25 M) | yes | 200 | 60 | 21 |

| 12d | n-BuOH (0.25 M) | yes | 250 | 60 | 29 |

| 13 | n-BuOH (0.25 M) | yes | 250 | 60 | 26 |

| 14 | n-BuOH (0.25 M) | yes | 270 | 60 | 49 |

HE = silicon carbide heating element;

The reaction was incomplete;

decomposition was observed;

with 3 equiv of morpholine.

The optimized microwave conditions were applicable to a range of substrate combinations. For more reactive starting materials, microwave heating at 200 °C was sufficient. As outlined in Scheme 6, drastic rate accelerations were observed for the reaction of pyrrolidine with aminobenzaldehydes 8c and 8k. Products 9c and 9k were obtained in excellent yields in only 10 or 30 min, respectively. Applying the same reaction parameters to the substantially less reactive piperidine in a reaction with 8c resulted in the formation of aminal 10a in excellent yield (reaction time 30 min). Combining piperidine with the less reactive aminobenzaldehyde 8k required for the reaction to be performed at 250 °C in order to obtain reasonable yields of aminal 10i. The latter aminal was found to not be readily accessible using standard reflux conditions. Good yields of aminal products could also be obtained for N-methyl- and N-phenyl piperazine, substrates that previously failed to undergo the desired reactions.

Scheme 6.

Optimized microwave conditions for other substrates.

A range of other amines that had not previously been explored in the aminal formation were also evaluated, including sterically encumbered substrates. Shown in Scheme 7 is a side-by-side comparison for reactions conducted either at reflux or microwave heating in n-butanol. Tetrahydrobenzoazepine 17a underwent the condensation cleanly to provide aminal 18 in high yield. Microwave heating proved superior not only in regard to reaction time but also yield. The same observation was made for 1-substituted tetrahydroisoquinolines 17b and 17c and 1-phenyl tetrahydro-β-carboline 17d. All corresponding aminal products were obtained in excellent yields.

Scheme 7.

Direct comparison of reflux vs. microwave conditions for various amines.

Regioselectivity of the Aminal Formation

An interesting situation arises for nonsymmetrical amines for which, at least in principle, different regioisomeric products may be formed (Scheme 8). In a reaction of aminobenzaldehyde 8k and 2-methylpyrrolidine, conducted at 180 °C under microwave irradiation, products 22 and 23 were obtained in a 2.4:1 ratio. This reflects a preference for functionalization of a tertiary C–H bond over a secondary C–H bond. This electronic effect apparently outweighs any potential steric issues. The outcome of this reaction was essentially independent of the reaction temperature and is very similar to what was observed in a reaction of 8c and 2-methylpyrrolidine, conducted under reflux in ethanol.12a As outlined previously in Scheme 4, THIQ leads to exclusive functionalization of a benzylic C–H bond when allowed to react with 8k under reflux in ethanol. Aminal 10f was formed as the only product in excellent yield. Based on the different available α-C–H bonds (benzylic vs. aliphatic), this outcome is entirely expected. We were thus surprised to observe the formation of small amounts of the regioisomeric product 24 when the reaction was conducted under microwave irradiation. At a temperature of 250 °C, a substantial amount of 24 was obtained (16%) although 10f was still formed as the major product. Extension of the reaction time from 30 min to two hours led to the isolation of 24 as the major product in 47% yield. In both cases, the combined yields of 10f and 24 were essentially identical. These observations suggest that 10f is the kinetic product of this transformation whereas 24 represents the thermodynamically more stable aminal. Furthermore, there appears to be a pathway for product isomerization. Computational results are consistent with the experimental findings.12c While the pathway leading to the formation of 24 was calculated to be higher in energy than that of 10f, the free energy of 24 is lower than that of 10f. Qualitatively similar observations were made in reactions of THIQ with 8c, although product 10e dominates in all cases. While this outcome is consistent with computational results (the difference in free energy between 10e and 25 was found to be smaller than that of 10f and 24), the reaction of THIQ with 8c could not be performed at 250 °C as this resulted in substantial decomposition. A reaction of 8c with 2-methylpiperidine led to the two expected regioisomeric products. Interestingly, the preference for functionalization of the tertiary C–H bond over a secondary C–H bond is more pronounced than was seen for 2-methylpyrrolidine.

Scheme 8.

Regioselectivity of the aminal formation.

We next evaluated the impact of electronic factors on product distributions (Scheme 9). Three different 2-arylpyrrolidines were allowed to react with aminobenzaldehyde 8k under identical conditions. The expected contra-steric preference for benzylic C–H bond over aliphatic C–H bond functionalization was observed in all instances. However, the electronics of the aryl ring exerted a marked influence on product distributions. Consistent with expectations, an electron-donating group placed in the para-position of the aromatic ring led to an increase in benzylic product, whereas an electron withdrawing group in the same position resulted in a reduced ratio of benzylic to aliphatic functionalization. Notably, the overall product yields were excellent in all cases.

Scheme 9.

Impact of electronic factors on the regioselectivity and yield of the aminal formation.

A related study was performed for three different methylbenzyl amines, substrates that were previously found to resist aminal formation under reflux conditions. A clear trend was again observed with regard to electronics: the more electron-rich the substrate, the higher the yield of aminal product. However, this conclusion has to be considered as tentative because aminal products 30a– c might differ in their propensity to hydrolyze, potentially affecting product yields. Perhaps not surprisingly, no trace amounts of products were observed that would have been the result of methyl group functionalization.

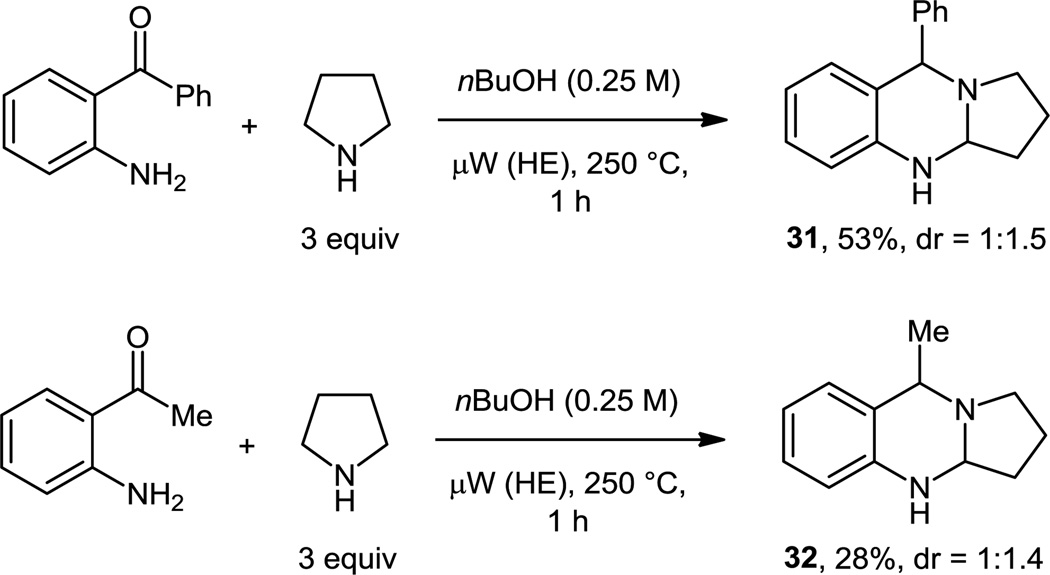

Reactions of Aminoketones

Previous attempts to expand the substrate scope from aminobenzaldehydes to related aminoketones had met with limited success. However, a reaction of aminobenzophenone with pyrrolidine, conducted under microwave irradiation at 250 °C, gave rise to the corresponding aminal (Scheme 10). Product 31 was isolated as a 1:1.5 mixture of diastereomers in 53% yield, following a reaction time of one hour. Aminoacetophenone also underwent the corresponding reaction, albeit less efficiently. In this case, intermediate enamine formation might prevent higher yields. Polshettiwar and Varma reported the unlikely formation of 32 in 45% yield (reaction performed under neat conditions in a microwave reactor, 60 min at 130 °C).16

Scheme 10.

Aminal formation with aminoketones.

Competing Side Reactions

In the course of our studies, we made additional observations that outline the complexity of the overall process, including potentially competing, undesired reaction pathways (Scheme 11). As expected for this particularly challenging substrate combination, aminobenzaldehyde 8k and morpholine underwent aminal formation only reluctantly (Scheme 11). Even a reaction conducted at 250 °C for two hours gave rise to 33 in only 12% yield. Interestingly, in addition to 33, the unexpected product 34a was observed in 38% yield. A simple switch from n-butanol to toluene as the solvent and an increase in substrate concentration allowed for the isolation of 34a in 70% yield. Related aminobenzaldehyde self-condensation products are well known.17 In particular, products in which the morpholine subunit is replaced with simple alkoxy groups have been well characterized.

Scheme 11.

Formation of aminobenzaldehyde self-condensation products.

In order to establish whether compounds such as 34a could intervene in other aminal forming reactions, we exposed a solution of aminobenzaldehyde in ethanol to one equivalent of pyrrolidine at room temperature for two days. No trace of aminal 9k was observed under these conditions. However, pyrrolidine-containing aminobenzaldehyde self-condensation product 34b was obtained in 61% yield. Notably, corresponding reactions conducted with piperidine or morpholine at room temperature gave none of the trimeric condensation products. In order to establish whether aminobenzaldehyde self-condensation products can still participate in aminal formation, we exposed 34a to 12 equivalents of pyrrolidine (200 °C, 30 min). Indeed, aminal 9k was obtained as a product, albeit in only 36% yield, establishing the reversibility of aminobenzaldehyde self-condensation.

Aminal Formation under Decarboxylative Conditions

As part of our initial study, we established that substitution of pyrrolidine for proline in a reaction with aminobenzaldehyde 8c gave rise to the identical aminal product 9c although the reaction was less efficient than that with pyrrolidine.12a However, upon further optimization, we achieved efficient formation of 9c in 85% yield for a reaction conducted under reflux in n-butanol at slightly lower concentration (Scheme 12). These conditions were applicable to other decarboxylative aminal formations such as the reaction of 8c with pipecolic acid to give 10a in 84% yield, and the reaction of 8m with proline to give aminal 9m in 85% yield. The ability of α-amino acids with a secondary amine to undergo the aminal formations is perfectly consistent with the intermediacy of azomethine ylides, as the latter species are known to be readily formed upon decarboxylative condensation of an α-amino acid with an aldehyde.18,19

Scheme 12.

Decarboxylative formation of aminals.

Driven by the notion that the decarboxylative formation of aminals based on amino acids might enable control over product regioselectivity, we tested this approach in the formation of aminals that might otherwise be difficult to prepare in regioselective fashion (Scheme 13). A reaction of aminobenzaldehyde 8c and amino acid 35 led to the expected product 25, albeit in only 25% yield. In addition, aminal 10e was isolated as the main product in 47% yield. Apparently, isomerization of the initially formed azomethine ylide is competitive with the direct pathway leading to aminal 25, possibly involving intermediate formation of THIQ that can engage 8c to form 10e. In contrast to what was seen for 35, the reactions of trans-4-hydroxyproline and trans-3-hydroxyproline with aminobenzaldehyde 8k were fully regioselective. Unfortunately, the efficiency of these processes was poor and the results shown in Scheme 13 represent the best yields that could be obtained under a variety of conditions (including reactions conducted under reflux). Our group13h and others20 have previously shown that trans-4-hydroxyproline forms N-alkyl pyrroles when allowed to react with aldehydes at elevated temperatures. This process becomes competitive with aminal formation when the reaction is conducted at higher temperatures.

Scheme 13.

Regioselectivity in the decarboxylative aminal formation.

Interception of Reactive Intermediates

Various studies were performed in an effort to obtain experimental evidence for the intermediacy of azome-thine ylides and ortho-azaquinonemethides.18,21 Since aldehydes are known to be potent dipolarophiles, we speculated that [3+2] cycloaddition products such as 38 may be isolated under appropriate conditions (Scheme 14). We further reasoned that a reduction in the amount of pyrrolidine in combination with an increased reaction molarity might render the [3+2] pathway competitive with aminal formation. Indeed, a reaction conducted with aminobenzaldehyde 8c and pyrrolidine in a 2:1 ratio and one molar concentration resulted in the formation of aminal 9c in 74% yield, in addition to [3+2] cycloaddition product 38. The latter was recovered as a single diastereomer in 18% yield. The yield of 38 was increased to 27% at the expense of aminal formation when the reaction was conducted in toluene under otherwise identical conditions. It was subsequently established that the [3+2] cycloaddition is reversible under certain conditions. Exposure of 38 to five equivalents of pyrrolidine for 10 min at 200 °C led to the isolation of aminal 9c in 55% yield. Starting material 38 was recovered in 42% yield.

Scheme 14.

Attempted capture of azomethine ylide intermediates.

Other efforts were aimed at trapping an azomethine ylide in an intramolecular process. In previous work on another project, we have successfully demonstrated the formation of azomethine ylide intermediates upon benzoic acid catalyzed condensation of 3-pyrroline with aldehydes, a process that ultimately leads to the formation of N-alkyl pyrroles.13g Specifically, a reaction of substituted salicylaldehyde 39 and 3-pyrroline resulted in the formation of [3+2] cycloaddition product 40 as a single diastereomer in 53% yield (Scheme 14). Based on this precedent, we prepared aminobenzaldehyde 41 bearing a pendant dipolarophile. Surprisingly, a reaction of 41 with pyrrolidine, conducted under the typical aminal-forming conditions gave neither aminal nor the expected cycloaddition product 43. Instead, quinoline 42 was generated in 61% yield. The formation of 42 most likely involves the initial isomerization of 41 to the corresponding enamine, presumably by conjugate addition of pyrrolidine and subsequent elimination. Alternatively, the requisite enamine could be formed via a dienolate intermediate. No formation of 42 was observed when 41 was heated in the absence of pyrrolidine.

Support for the intermediacy of ortho-azaquinonemethides was obtained from a reaction of aminobenzaldehyde 44 and pyrrolidine, conducted under reflux in ethanol (Scheme 15). The expected product 45 was obtained in 7% yield, in addition to 47 (7%), conjugate addition product 48 (42%), aminal 49 (20%) and recovered starting material 44 (9%). The formation of 45 is fully consistent with an ortho-azaquinonemethide undergoing an endo-selective hetero-Diels-Alder reaction (via 46). Given the mostly zwitterionic nature of the ortho-azaquinonemethide, the cycloaddition may not be fully concerted. Importantly, we could show that 45 does not form via an alternate pathway involving 47. Exposure of 47 to pyrrolidine under reflux in ethanol did not result in the formation of any trace of 45 within 48 hours. An aza-Baylis-Hillman-type pathway was ruled out on the basis that this would have to involve an iminium ion, species that are unlikely to exist under these conditions. An intramolecular Baylis-Hillman-type pathway to the formation of 47 (conjugate addition of pyrrolidine to 44 with simultaneous attack of the aldehyde) was ruled out since this would involve the unlikely formation of an intermediate with a ten-membered ring. Moreover, heating 44 by itself or in the presence of Hünig’s base or N-methylpyrrolidine led to no reaction.

Scheme 15.

Attempts to capture azaquinonemethide intermediates.

In another attempt to capture an ortho-azaquinonemethide intermediate, we decided to evaluate an amine containing a pendant dieneophile. However, a reaction of aminobenzaldehyde 8c with pyrrolidine 50 did not give rise to any of the desired cycloaddition product 53. Interestingly, in addition to the expected aminal products 51 (15%) and 52 (3%), we observed the formation of aminal 54 (29%) and quinoline 55 (27%) as the major products. A plausible pathway for the formation of 54 and 55 is outlined in Scheme 15. Upon reaction of 8c with 50 to give the typical azomethine ylide intermediate 56, the latter could undergo a transformation to dienamine 57, either by a concerted proton transfer or a protonation/deprotonation event. Stepwise hydrolysis of dienamine 57 via an intermediate such as 58 could result in enamine 59, a species that could subsequently cyclize to aminal 54. Importantly, the regioisomer of 54 was not observed, ruling out any pathways that would involve the formation of free 2-methylpyrrolidine. Formation of quinoline 55 is readily explained by Friedländer condensation of 8c with acetaldehyde, a byproduct from the hydrolysis of 58.

Synthesis of Quinazolinone Alkaloids

There are a sizable number of natural products that contain aminal substructures.22 Moreover, the ring-fused aminals obtained from aminobenzaldehydes and secondary amines represent direct precursors of certain quinazolinone alkaloids and are thus ideally suited to generate analogues of these biologically active species.23,24 Oxidation of aminals to quinazolinones is readily accomplished under reflux in acetone with potassium permanganate as the oxidant (Scheme 16). Deoxyvasicinone, rutaecarpine, mackinazolinone, and the unnatural analogue 60 could thus be obtained in good yields via oxidation of the corresponding aminals. Selective oxidation of aminals to amidines without affecting the benzylic position was achieved via iodine-promoted oxidation of deprotonated precursors. This allowed for the synthesis of deoxyvasicine and vasicine. A limitation of the two-step vasicine synthesis is the poor yield obtained for the starting material 37. As a potential solution to this shortcoming, we found that the decarboxylative aminal formation of hydroxyprolines proceeds much more efficiently with aminobenzaldehyde 8c than 8k. This finding was applied to the synthesis of 62, a novel regioisomer of vasicinone. Reaction of trans-4-hydroxyproline with 8c provided regioselective access to aminal 61 in 50% yield. Subsequent oxidation with potassium permanganate, followed by removal of the bromine substituents via hydrogenolysis provided 62 in 32% overall yield in just three steps from commercially available materials.

Scheme 16.

Synthesis of quinazolinone alkaloids and analogues.

Conclusion

Ring-fused aminals are readily available via condensation of secondary amines with ortho-aminobenzaldehydes. These reactions feature simultaneous reductive N-alkylation and oxidative α-amination, effectively rendering the process redox-neutral. While many of the aminal-forming reactions can be performed with conventional heating methods, microwave heating proved to be beneficial in all cases and for some substrates it is required. The aminal products are valuable precursors to various quinazolinone alkaloids and their analogues. The reaction exhibits interesting mechanistic features and ortho-azaquinonemethides and azomethine ylides have been identified as reactive intermediates. The overall process adds to the growing number of reactions that involve non-pericyclic reaction pathways of azomethine ylides, an area that is expected to experience further growth.

General Information

Reagents and solvents were purchased from commercial sources and were used as received unless otherwise stated. Toluene, THF, Et2O, and triethylamine were distilled prior to use. All secondary amines were purified by distillation prior to use. Microwave reactions were carried out in a CEM Discover reactor. Silicon carbide (SiC) passive heating elements were purchased from Anton Paar. Purification of reaction products was carried out by flash column chromatography using Sorbent Technologies Standard Grade silica gel (60 Å, 230–400 mesh). Analytical thin layer chromatography was performed on EM Reagent 0.25 mm silica gel 60 F254 plates. Visualization was accomplished with UV light or potassium permanganate, and Dragendorff-Munier stains followed by heating. Melting points were recorded on a Thomas Hoover capillary melting point apparatus and are uncorrected. Infrared spectra were recorded on an ATI Mattson Genesis Series FT-Infrared spectrophotometer. Proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectra (1H-NMR) were recorded on a Varian VNMRS-500 MHz and are reported in ppm using the solvent as an internal standard (CDCl3 at 7.26 ppm). Data are reported as app = apparent, s = singlet, d = doublet, t = triplet, q = quartet, m = multiplet, comp = complex, br = broad; and coupling constant(s) in Hz. Proton-decoupled carbon nuclear magnetic resonance spectra (13C-NMR) were recorded on a Varian VNMRS-500 MHz and are reported in ppm using the solvent as an internal standard (CDCl3 at 77.0 ppm). Mass spectra were recorded on a Finnigan LCQ-DUO mass spectrometer. Optical rotations were measured using a 1 mL cell with a 1 dm path length on a Jasco P–2000 polarimeter at 589 nm and at 25 °C. Products 9a–o,12a 10a,12a 10b,12c 10c–h 12a, 10i,25a 22–24,12c 38,12c 39–40,13g 44–45,12c 47– 49,12c 54,12a 55,25b 60,25c deoxyvasicinone,12b rutaecarpine,12a mackinazolinone,25d deoxyvasicine25e and vasicine25f were previously reported and their published characterization data matched our own in all regards.

General Microwave Procedure

A 10 mL microwave reaction tube was charged with a 10 × 8 mm SiC passive heating element, aminobenzaldehyde (1 mmol), n-BuOH (0.25 M) and amine (3 equiv). The reaction tube was sealed with a Teflon-lined snap cap, and heated in a microwave reactor (Note: SiC passive heating elements must not be used in conjunction with stir bars because they may score glass and cause vessel failure). After cooling with compressed air flow, the reaction mixture was transferred to a round bottom flask and the vessel was rinsed with EtOAc (4 × 2 mL). Solvent was then removed in vacuo and the residue was loaded onto a short column and purified by silica gel chromatography.

General Reflux Procedure

A 10 mL round bottom flask was charged with a magnetic stir bar, aminobenzaldehyde (1 mmol), n-BuOH (4 mL) and amine (3 equiv). The resulting mixture was heated at reflux until the starting material was consumed as determined by TLC. Solvent was then removed in vacuo and the residue was loaded onto a short column and purified by silica gel chromatography.

General Oxidation Procedure

A 10 mL round bottom flask was charged with a magnetic stir bar, aminal (0.25 mmol), acetone (2.5 mL) and potassium permanganate (5 equiv). The resulting mixture was heated at reflux for 2 h. The solution was filtered through a pad of celite and the filtrate was washed with acetone (20 mL). Solvent was removed in vacuo and the residue was loaded onto a short column and purified by silica gel chromatography.

Compound 10j

Following the general microwave procedure, 10j was obtained from 2-amino-3,5-dibromobenzaldehyde and N-phenylpiperazine after 1 h at 250 °C. 10j was isolated as a tan solid in 73% yield (Rf = 0.31 in hexanes/EtOAc 85:15 v/v).

mp: 164–168 °C.

IR (KBr) 3317, 2952, 2925, 2830, 2785, 1599, 1491, 1458, 1325, 1267, 1250, 1214, 1145, 930, 844, 771, 757, 691, 608 cm−1.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 7.43 (app dd, J = 2.3, 0.8 Hz, 1H), 7.33–7.28 (comp, 2H), 7.04 (d, J = 1.4 Hz, 1H), 7.00–6.96 (comp, 2H), 6.98 (app tt, J = 7.3, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 4.31 (br s, 1H), 4.19–4.08 (m, 1H), 3.92 (d, J = 15.5 Hz, 1H), 3.74 (d, J = 15.5 Hz, 1H), 3.52 (dd, J = 11.7, 3.0 Hz, 1H), 3.37–3.26 (comp, 2H), 3.21 (dd, J = 11.8, 6.2 Hz, 1H), 3.04 (ddd, J = 11.5, 6.3, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 2.56 (ddd, J = 11.0, 7.0, 3.6 Hz, 1H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 150.8, 138.6, 132.6, 129.3, 128.8, 121.9, 120.5, 116.7, 109.6, 109.1, 68.0, 54.8, 53.6, 49.2, 49.1.

m/z (ESI–MS) 423.9 [M+H]+.

Compound 10k

Following the general microwave procedure, 10k was obtained from 2-amino-3,5-dibromobenzaldehyde and N-methylpiperazine after 1 h at 250 °C. Compound 10k was isolated as an off-white solid in 59% yield (Rf = 0.18 in EtOAc/MeOH 90:10 v/v).

mp: 116–119 °C.

IR (KBr) 3389, 2933, 2842, 2897, 2516, 1594, 1475, 1346, 1323, 1285, 1143, 1079, 900, 856, 706 cm−1.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 7.40 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.00 (s, 1H), 4.27 (br s, 1H), 4.12–3.75 (comp, 2H), 3.68 (d, J = 15.1 Hz, 1H), 2.91 (br s, 1H), 2.78 (br s, 1H), 2.67–2.36 (comp, 4H), 2.34 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 138.7, 132.5, 128.7, 122.1, 109.4, 108.9, 67.9, 59.1, 54.7, 54.7, 50.0, 45.8. m/z (ESI–MS) 362.0 [M+H]+.

Compound 18

Following the general microwave procedure, 18 was obtained from 2-amino-3,5-dibromobenzaldehyde (0.25 mmol) and 2,3,4,5-tetrahydro-1H–benzo[c]azepine (17a)25g (2 equiv) after 30 min at 200 °C in n-butanol (1 mL). 18 was isolated as a tan solid in 91% yield (Rf = 0.40 in hexanes/EtOAc 70:30 v/v).

mp: 124–127 °C.

IR (KBr) 3372, 2925, 2849, 1590, 1477, 1451, 1364, 1357, 1292, 1259, 1173, 1061, 946, 880, 749, 635 cm−1.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 7.45 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.33–7.06 (comp, 4H), 6.97 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 5.50 (d, J = 2.5 Hz, 1H), 4.78 (br s, 1H), 4.04 (d, J = 15.5 Hz, 1H), 3.63 (d, J = 15.5 Hz, 1H), 3.34 (ddd, J = 13.5, 7.3, 3.1 Hz, 1H), 3.27–3.02 (comp, 2H), 2.88 (ddd, J = 14.7, 9.3, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 1.96–1.82 (m, 1H), 1.82–1.68 (m, 1H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 141.7, 139.5, 137.8, 132.2, 130.0, 129.1, 128.9, 128.4, 126.1, 123.3, 109.1, 108.9, 74.4, 54.3, 53.1, 35.2, 26.0.

m/z (ESI–MS) 409.0 [M+H]+.

Compound 19

Following the general microwave procedure, 19 was obtained from 2-amino-3,5-dibromobenzaldehyde (0.25 mmol) and 1-methyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline (17b)25h (2 equiv) after 30 min at 200 °C in n-butanol (1 mL). 19 was isolated as a tan solid in 88% yield (Rf = 0.14 in hexanes/EtOAc 93:7 v/v).

mp: 121–123 °C.

IR (KBr) 3409, 2993, 2920, 2838, 1589, 1478, 1391, 1374, 1294, 1131, 1095, 1038, 933, 884, 753, 725, 700 cm−1.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 7.57 (dd, J = 7.7, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.46 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.38–7.25 (comp, 2H), 7.17 (dd, J = 7.3, 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.12 (d, J = 1.5 Hz, 1H), 4.63 (br s, 1H), 4.55 (d, J = 17.0 Hz, 1H), 3.72 (d, J = 17.0 Hz, 1H), 3.17–3.06 (m, 1H), 2.92 (app td, J = 10.9, 3.5 Hz, 1H), 2.85–2.69 (comp, 2H), 1.73 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 139.5, 137.6, 134.1, 132.2, 129.2, 128.6, 127.4, 126.7, 124.7, 120.5, 109.1, 107.9, 69.8, 51.2, 46.3, 29.6, 26.4.

m/z (ESI–MS) 409.0 [M+H]+.

Compound 20

Following the general microwave procedure, 20 was obtained from 2-amino-3,5-dibromobenzaldehyde (0.25 mmol) and 6,7-dimethoxy-1-phenyl-1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline (17c)25i (2 equiv) after 1.5 h at 200 °C in n-butanol (1 mL). 20 was isolated as a white solid in 93% yield (Rf = 0.29 in hexanes/EtOAc 70:30 v/v).

mp: 73–76 °C.

IR (KBr) 3412, 2931, 2831, 1609, 1589, 1515, 1472, 1290, 1251, 1233, 1168, 1140, 1021, 793, 754, 699 cm−1.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 7.46 (dd, J = 2.3, 0.7 Hz, 1H), 7.44–7.36 (comp, 2H), 7.31–7.21 (comp, 3H), 6.94 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 6.63 (s, 1H), 6.20 (s, 1H), 4.77 (br s, 1H), 3.91–3.79 (comp, 4H), 3.60 (s, 3H), 3.45 (d, J = 16.9 Hz, 1H), 3.30 (ddd, J = 16.0, 12.4, 6.1 Hz, 1H), 3.01 (app td, J = 11.7, 3.6 Hz, 1H), 2.82 (ddd, J = 11.7, 6.1, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 2.72 (ddd, J = 16.0, 3.7, 1.6 Hz, 1H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 148.4, 147.7, 145.9, 137.6, 132.3, 132.2, 128.8, 128.3, 127.5, 127.4, 126.4, 121.4, 111.0, 110.7, 108.2, 108.1, 75.9, 56.0, 55.8, 51.7, 45.9, 29.3.

m/z (ESI–MS) 530.9 [M+H]+.

Compound 21

Following the general microwave procedure, 21 was obtained from 2-amino-3,5-dibromobenzaldehyde (0.25 mmol) and 1-phenyl-2,3,4,9-tetrahydro-1H–pyrido[3,4-b]indole (17d)25j (2 equiv) after 1 h at 200 °C in n-butanol (1 mL). 21 was obtained as an oil in 87% yield (Rf = 0.35 in hexanes/EtOAc 70:30 v/v).

IR (KBr) 3398, 3056, 2903, 2841, 1589, 1463, 1298, 1171, 1106, 1028, 1016, 979, 932, 858, 743, 698 cm−1.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 7.58 (app d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.55–7.46 (comp, 3H), 7.38–7.28 (comp, 4H), 7.27–7.22 (comp, 2H), 7.17 (app dtd, J = 20.1, 7.1, 1.2 Hz, 2H), 6.99 (br s, 1H), 4.93 (br s, 1H), 3.93 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 3.56 (d, J = 16.8 Hz, 1H), 3.26–3.05 (comp, 2H), 3.03–2.92 (m, 1H), 2.92–2.79 (m, 1H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 142.9, 137.1, 136.5, 135.6, 132.5, 129.0, 128.8, 128.7, 128.4, 127.4, 126.7, 122.6, 121.9, 120.0, 119.1, 111.4, 109.3, 108.8, 73.3, 50.7, 46.8, 21.8.

m/z (ESI–MS) 510.0 [M+H]+.

Compound 25

Following the general microwave procedure, 10e was obtained from 2-amino-3,5-dibromobenzaldehyde and 1,2,3,4-tetrahydroisoquinoline (2.0 mmol) after 1 h at 220 °C. 10e was isolated in 69% yield and matches reported spectroscopic data in all regards.12c In addition, 25 was recovered as a pale yellow solid in 14% yield (Rf = 0.20 in hexanes/EtOAc 80:20 v/v).

mp: 135–138 °C.

IR (KBr) 3384, 3067, 2926, 1701, 1685, 1676, 1589, 1560, 1478, 1342, 1290, 1265, 1128, 1030, 855, 738 cm−1.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 7.40 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 7.21–7.13 (comp, 3H), 7.07–7.00 (comp, 2H), 4.73–4.69 (m, 1H), 4.29 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 4.24 (s, 1H), 3.92 (d, J = 15.0 Hz, 1H), 3.80 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 3.69 (d, J = 15.0 Hz, 1H), 3.36 (dd, J = 17.0, 4.8 Hz, 1H), 2.89 (dd, J = 17.0, 3.2 Hz, 1H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 139.3, 133.4, 132.4, 129.9, 129.1, 128.8, 126.5, 126.4, 126.2, 121.6, 108.9, 108.8, 66.1, 54.7, 49.7, 34.5.

m/z (ESI–MS) 395.0 [M+H]+.

Compound 26

Following the general microwave procedure, 26 was obtained from 2-aminobenzaldehyde (0.25 mmol) and 2-methylpiperidine (2 equiv) after 30 min at 250 °C. 26 was isolated as a tan semi-solid in 64% yield. In addition, 27 was obtained as a white solid in 15% yield (1:1 mixture of diasteomers). Characterization data for 26: (Rf = 0.17 in hexanes/EtOAc 70:30 v/v).

IR (KBr) 3405, 2917, 2849, 1643, 1480, 1451, 1371, 1296, 1162, 1122, 858 cm−1.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 7.41 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.03 (s, 1H), 4.35 (d, J = 17.0 Hz, 1H), 4.24 (br s, 1H), 3.45 (d, J = 17.0 Hz, 1H), 2.49–2.44 (comp, 2H), 1.77–1.51 (comp, 6H), 1.31 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 138.2, 132.1, 128.9, 120.5, 109.1, 107.7, 77.2, 67.6, 51.0, 49.3, 38.0, 25.8, 20.3.

m/z (ESI–MS) 361.1 [M+H]+.

Compound 28a

Following the general microwave procedure, 28a was obtained from 2-amino-3,5-dibromobenzaldehyde (0.25 mmol) and 2-(4-methoxyphenyl)pyrrolidine25k after 30 min at 200 °C in n-butanol (1 mL). 28a was isolated as a clear oil in 83% yield. In addition, 29a was obtained as a white semisolid in 14% yield (1:1 mixture of diastereomers). Characterization data for 28a: (Rf = 0.23 in hexanes/EtOAc 90:10 v/v).

IR (KBr) 2856, 2360, 2342, 1734, 1700, 1507, 1473, 1457, 1247, 1172, 830, 668 cm−1.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 7.43 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 7.40–7.31 (m, 2H), 6.91 (s, 1H), 6.88–6.81 (m, 2H), 4.75 (br s, 1H), 3.78 (s, 3H), 3.68 (d, J = 17.0 Hz, 1H), 3.56 (d, J = 17.0 Hz, 1H), 3.16 (app td, J = 8.7, 3.1 Hz, 1H), 2.77–2.68 (m, 1H), 2.29–2.14 (m, 1H), 2.13–1.95 (comp, 3H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 159.2, 138.5, 136.1, 132.3, 129.3, 127.8, 121.3, 114.1, 108.4, 107.9, 79.3, 55.5, 50.2, 45.7, 43.4, 21.1.

m/z (ESI–MS) 438.9 [M+H]+.

Compound 28b

Following the general microwave procedure, 28b was obtained from 2-amino-3,5-dibromobenzaldehyde (0.25 mmol) and 2-phenylpyrrolidine25k after 30 min at 200 °C in n-butanol (1 mL). 28b was isolated as a clear oil in 64% yield. In addition, 29b was obtained as a white semi-solid in 33% yield (1:1 mixture of diastereomers). Characterization data for 28b: (Rf = 0.32 in hexanes/EtOAc 90:10 v/v).

IR (KBr) 3410, 2954, 1593, 1475, 1445, 1285, 1178, 1149, 1121, 993, 756, 699 cm−1.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 7.54–7.38 (comp, 3H), 7.38–7.29 (comp, 2H), 7.29–7.21 (m, 1H), 6.91 (s, 1H), 4.79 (br s, 1H), 3.68 (d, J = 17.0 Hz, 1H), 3.58 (d, J = 17.0 Hz, 1H), 3.19 (app td, J = 8.7, 3.5 Hz, 1H), 2.84–2.67 (m, 1H), 2.31–2.20 (m, 1H), 2.14–1.96 (comp, 3H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 144.0, 138.2, 132.08, 129.1, 128.5, 127.5, 126.3, 121.0, 108.2, 107.7, 79.3, 50.2, 45.5, 43.4, 21.1.

m/z (ESI–MS) 409.0 [M+H]+.

Compound 28c

Following the general microwave procedure, 28c was obtained from 2-amino-3,5-dibromobenzaldehyde (0.25 mmol) and 2-(4-trifluoromethylphenyl)pyrrolidine25k after 30 min at 200 °C in n-butanol (1 mL). 28c was isolated as a clear oil in 58% yield. In addition, 29c was obtained as a white semi-solid in 37% yield (1:1 mixture of diasteromers). Characterization data for 28c: (Rf = 0.34 in hexanes/EtOAc 90:10 v/v).

IR (KBr) 3414, 2955, 1593, 1475, 1406, 1325, 1164, 1126, 1071, 1017, 840 cm−1.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 7.61–7.57 (comp, 4H), 7.45 (d, J = 2.0 Hz, 1H), 6.93 (s, 1H), 4.77 (br s, 1H), 3.73–3.53 (comp, 2H), 3.20 (app td, J = 8.7, 3.3 Hz, 1H), 2.86–2.67 (m, 1H), 2.31–2.15 (m, 1H), 2.15–1.95 (comp, 3H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 148.4, 137.8, 132.3, 129.9, 129.7, 129.2, 127.0, 125.6 (q, JC–F = 3.6 Hz), 120.8, 108.4, 108.3, 79.1, 50.2, 45.4, 43.6, 21.2.

m/z (ESI–MS) 477.0 [M+H]+.

Compound 30a

Following the general microwave procedure, 30a was obtained from 2-amino-3,5-dibromobenzaldehyde and N-methyl-p-methoxybenzylamine25l after 30 min at 250 °C. 30a was obtained as a clear oil in 41% yield (Rf = 0.36 in hexanes/EtOAc/Et3N 69:30:1 v/v/v).

IR (KBr) 3409, 2950, 2835, 1611, 1595, 1510, 1484, 1346, 1301, 1247, 1170, 1126, 1035, 957, 805 cm−1.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 7.44 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 7.38–7.33 (comp, 2H), 6.99 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 6.94–6.88 (comp, 2H), 4.90 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 4.75 (br s, 1H), 3.81 (s, 3H), 3.77 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H), 3.64 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H), 2.27 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 160.0, 139.0, 132.8, 132.6, 129.1, 128.8, 122.2, 114.2, 108.5, 108.4, 75.3, 55.6, 53.2, 40.2.

m/z (ESI–MS) 412.9 [M+H]+.

Compound 30b

Following the general microwave procedure, 30b was obtained from 2-amino-3,5-dibromobenzaldehyde and N-methylbenzylamine after 30 min at 250 °C. 30b was obtained as a light yellow solid in 29% yield (Rf = 0.38 in hexanes/EtOAc/Et3N 69:30:1 v/v/v).

mp: 108–112 °C.

IR (KBr) 3058, 2937, 1684, 1594, 1485, 1447, 1339, 1275, 1158, 1103, 1040, 1013, 983, 864, 742, 698 cm−1.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 7.48–7.41 (comp, 3H), 7.41–7.31 (comp, 3H), 7.00 (d, J = 1.0 Hz, 1H), 5.01 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 4.79 (br s, 1H), 3.77 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H), 3.65 (d, J = 15.9 Hz, 1H), 2.32 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 140.5, 138.6, 132.4, 129.0, 128.7, 128.5, 127.2, 121.8, 108.3, 108.2, 75.2, 52.5, 40.3.

m/z (ESI–MS) 383.0 [M+H]+.

Compound 30c

Following the general microwave procedure, 30c was obtained from 2-amino-3,5-dibromobenzaldehyde and N-methyl-p-trifluoromethylbenzylamine25m after 30 min at 250 °C. 30c was obtained as a clear oil in 20% yield (Rf = 0.37 in hexanes/EtOAc/Et3N 69:30:1 v/v/v).

IR (KBr) 3399, 2945, 1618, 1595, 1486, 1411, 1325, 1273, 1161, 1125, 1125, 1067, 1014, 856, 823, 739 cm−1.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 7.63 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.56 (d, J = 8.2 Hz, 2H), 7.47 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 7.00 (d, J = 2.3 Hz, 1H), 5.09 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 4.84 (br s, 1H), 3.71 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H), 3.58 (d, J = 16.3 Hz, 1H), 2.37 (s, 3H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 144.8, 137.9, 132.5, 130.6 (q, JC–F = 31.4 Hz), 129.1, 127.6, 125.6 (q, JC–F = 3.8 Hz), 123.9 (q, JC–F = 272.3 Hz), 121.6, 108.7, 108.5, 74.3, 51.4, 40.6.

m/z (ESI–MS) 451.1 [M+H]+.

Compound 31

Following the general microwave procedure, 31 was obtained from 2-aminobenzophenone (0.5 mmol) and pyrrolidine after 1h at 250 °C. 31 was isolated as a yellow semi-solid in 53% yield (1:1.5 mixture of diastereomers) (Rf = 0.36 in hexanes/EtOAc 70:30 v/v).

IR (KBr) 3219, 2956, 2871, 2368, 2602, 1473, 1364, 1300, 1248, 1152, 1089, 1029, 1007, 940, 923, 756, 703 cm−1.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 7.39−7.27 (comp, 7H), 7.24–7.19 (comp, 3H), 7.08 (app td, J = 8.4, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.02 (app td, J = 7.5, 1.5 Hz, 1H), 6.91 (dd, J = 7.5, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 6.73–6.60 (comp, 3H), 6.58–6.53 (comp, 2H), 4.92 (s, 1H), 4.58 (s, 1H), 4.37 (d, J = 43 Hz, 1H), 4.11 (br s, 1H), 3.89−3.84 (m, 1H), 3.75 (br s, 1H), 3.05 (app td, J = 8.5, 3.7 Hz, 1H), 2.90 (app td, J = 8.9, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 2.86–2.77 (m, 1H), 2.24−2.12 (comp, 2H), 2.10− 1.85 (comp, 4H), 1.85–1.72 (comp, 2H), 1.66–1.58 (m, 1H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 144.2, 143.6, 143.0, 129.6, 129.4, 128.8, 128.6, 128.3, 128.1, 127.6, 127.5, 127.1, 126.8, 126.6, 119.2, 118.6, 117.1, 116.6, 113.9, 104.7, 73.7, 69.9, 65.0, 61.0, 50.8, 50.0, 32.7, 30.4, 21.3, 20.0.

m/z (ESI−MS) 251.1 [M+H]+.

Compound 32

Following the general microwave procedure, 32 was obtained from 2-aminoacetophenone (0.5 mmol) and pyrrolidine after 1h at 250 °C. 32 was isolated as a tan oil in 28% (1:1.4 mixture of diastereomers) (Rf = 0.25 in EtOAc/MeOH 95:5 v/v).

IR (KBr) 3330, 2965, 2874, 1633, 1609, 1496, 1445, 1372, 1342, 1266, 1188, 1101, 1035, 938, 753 cm−1.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 7.12–7.06 (m, 1H), 7.06–6.93 (comp, 3H), 6.79–6.71 (m, 1H), 6.69–6.61 (m, 1H), 6.58–6.54 (m, 1H), 6.48–6.42 (m, 1H), 4.70 (app t, J = 4.5 Hz, 1H), 4.07–4.02 (m, 1H), 3.96–3.90 (m, 1H), 3.90–3.83 (m, 1H), 3.64 (br s, 1H), 3.13 (app td, J = 9.0, 4.3 Hz, 1H), 2.97 (app td, J = 8.3, 4.3 Hz, 1H), 2.72– 2.61 (m, 1H), 2.52–2.42 (m, 1H), 2.20–1.80 (comp, 7H), 1.75–1.63 (comp, 2H), 1.52–147 (comp, 3H), 1.46–1.42 (comp, 3H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 143.1, 141.6, 128.0, 127.0(6), 127.0(5), 126.1, 125.3, 122.6, 118.5, 117.0, 115.5, 113.8, 72.6, 64.2, 56.2, 52.4, 49.6, 47.9, 32.9, 31.2, 24.9, 21.0, 20.4, 19.1.

m/z (ESI–MS) 189.1 [M+H]+.

Compound 33

Following the general microwave procedure, 33 was obtained from 2-aminobenzaldehyde and morpholine after 2 h at 250 °C. 33 was obtained as a light yellow solid in 12% yield (Rf = 0.36 in EtOAc/MeOH 90:10 v/v).

mp: 78–81 °C.

IR (KBr) 3357, 2979, 2852, 1608, 1493, 1456, 1362, 1342, 1290, 1274, 1126, 1045, 1030, 930, 857, 743, 699 cm−1.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 7.04 (app td, J = 7.8, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 6.93 (app d, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 6.72 (app td, J = 7.5, 1.2 Hz, 1H), 6.58 (dd, J = 7.8, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 4.11–3.73 (comp, 6H), 3.70 (d, J = 15.3 Hz, 1H), 3.58 (dd, J = 11.3, 5.5 Hz, 1H), 3.06–2.87 (m, 1H), 2.52–2.32 (m, 1H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 141.7, 127.4, 127.0, 119.0, 118.6, 115.3, 69.8, 67.2, 67.1, 55.1, 49.2.

m/z (ESI–MS) 189.3 [M+H]+.

In addition, 34a was obtained as a white solid in 38% yield (Rf = 0.19 in hexanes/EtOAc 70:30 v/v).

mp: 251–253 °C.

IR (KBr) 3318, 2024, 2955, 2855, 2807, 1612, 1498, 1479, 1450, 1368, 1308, 1216, 1115, 1094, 1072, 1020, 963, 892, 871, 749 cm−1.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 7.30–7.21 (comp, 4H), 7.15–7.02 (comp, 3H), 7.02–6.97 (m, 1H), 6.94–6.81 (comp, 3H), 6.71 (app d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 5.82 (s, 1H), 5.31 (d, J = 3.2 Hz, 1H), 4.84 (br s, 1H), 4.54 (s, 1H), 3.87–3.82 (comp, 4H), 3.45–3.31 (m, 2H), 2.84 (app dt, J = 11.6, 4.6 Hz, 2H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 146.3, 144.4, 140.7, 130.7, 129.1, 129.0, 128.8, 128.7, 128.5, 127.9, 125.3, 124.4, 124.2, 123.7, 123.3, 123.3, 120.00, 117.4, 84.8, 70.4, 67.7, 64.5, 50.5.

m/z (ESI–MS) 397.0 [M+H]+.

Compound 34b

A 10 mL round bottom flask was charged with 2-aminobenzaldehyde (0.363 g, 3 mmol), absolute ethanol (4 mL) and pyrrolidine (0.083 mL, 1 mmol) and was stirred at room temperature for 2 days. After this time, solvent was removed in vacuo and the residue was purified by silica gel chromatography. 34b was obtained as a light yellow solid in 61% yield (Rf = 0.26 in hexanes/EtOAc 70:30 v/v).

mp: 184–187 °C.

IR (KBr) 3375, 3050, 2967, 2800, 1734, 1610, 1572, 1494, 1480, 1447, 1369, 1334, 1305, 1243, 1218, 1128, 1070, 1007, 963, 952, 873, 792, 742 cm−1.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 7.31–7.18 (comp, 3H), 7.14 (app d, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.11–7.00 (comp, 3H), 7.00– 6.93 (comp, 2H), 6.92–6.80 (comp, 2H), 6.71 (app d, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 5.95 (s, 1H), 5.29 (d, J = 1.8 Hz, 1H), 4.85 (br s, 1H), 4.50 (s, 1H), 3.37–3.22 (m, 2H), 2.95–2.78 (m, 2H), 2.03–1.82 (comp, 4H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 145.9, 144.2, 140.8, 130.2, 129.4, 128.9, 128.5, 128.4, 128.3, 127.8, 127.8, 124.6, 124.2, 123.6, 123.5, 123.1 119.9, 117.4, 83.8, 70.8, 63.8, 51.2, 23.8.

m/z (ESI–MS) 381.0 [M+H]+.

Compound 36

Following the general microwave procedure, 36 was obtained from 2-aminobenzaldehyde (0.25 mmol) and trans-4-hydroxy-L-proline (2.1 equiv) after 15 min at 150 °C in n-butanol (1 mL). 36 was obtained as a white solid in 18% yield (1:1.2 mixture of diasteromers) (Rf = 0.17 in EtOAc/MeOH 90:10 v/v).

mp: 126–129 °C.

IR (KBr) 3284, 2922, 2806, 2361, 1610, 1491, 1379, 1267, 1152, 1091, 1018, 822, 746 cm−1.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 7.07–6.92 (comp, 4H), 6.77 (app t, J = 7.6 Hz, 1H), 6.70 (app t, J = 7.3 Hz, 1H), 6.60 (app d, J = 7.8 Hz, 1H), 6.51 (app d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 4.56 (br s, 1H), 4.52–4.47 (m, 1H), 4.47–4.40 (m, 1H), 4.23–4.15 (comp, 2H), 4.07 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 3.88 (d, J = 15.8 Hz, 1H), 3.83 (d, J = 16.0 Hz, 1H), 3.30 (dd, J = 9.7, 5.9 Hz, 1H), 3.17 (dd, J = 10.4, 6.2 Hz, 1H), 2.96 (app d, J = 10.4 Hz, 1H), 2.73 (app d, J = 9.7 Hz, 1H), 2.50–2.39 (comp, 2H), 2.20–2.00 (comp, 3H), 1.76 (app d, J = 13.8 Hz, 1H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) 142.7, 142.6, 127.4, 127.3, 119.7, 119.3, 118.6, 118.4, 116.0, 114.7, 104.8, 103.0, 70.9, 70.8, 70.4, 69.9, 60.8, 59.6, 50.1, 49.3, 44.1, 43.3.

m/z (ESI–MS) 191.2 [M+H]+.

Compound 37

Following the general microwave procedure, 37 was obtained from 2-aminobenzaldehyde (0.25 mmol) and trans-4-hydroxy-L-proline (2.1 equiv) after 15 min at 150 °C in n-butanol (1 mL). 37 was obtained as a white solid in 11% yield (1:1.1 mixture of diasteromers) (Rf = 0.21 in EtOAc/MeOH 90:10 v/v).

mp: 128–130 °C.

IR (KBr) 3271, 2924, 2841, 2784, 1609, 1493, 1451, 1378, 1303, 1263, 1151, 1132, 1087, 1037, 992, 843, 752 cm−1.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 7.06 (app t, J = 7.7 Hz, 1H), 7.04–6.98 (m, 1H), 6.99–6.91 (comp, 2H), 6.75 (app t, J = 7.4 Hz, 1H), 6.72–6.66 (comp, 2H), 6.50 (app d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 4.35 (app dt, J = 7.6, 3.8 Hz, 1H), 4.27 (br s, 1H), 4.21 (d, J = 16.2 Hz, 1H), 4.09–4.05 (m, 1H), 3.90 (d, J = 15.0 Hz, 1H), 3.87–3.79 (comp, 3H), 3.21 (app td, J = 9.3, 4.0 Hz, 1H), 2.99 (app td, J = 9.0, 4.6 Hz, 1H), 2.91 (app td, J = 9.2, 6.0 Hz, 1H), 2.53– 2.41 (comp, 2H), 2.42–2.27 (comp, 2H), 1.93–1.73 (comp, 3H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 142.5, 142.4, 127.4(2), 127.4(0), 127.3, 127.2, 120.4, 118.8, 118.3, 114.6, 104.8, 104.3, 77.2, 76.9, 73.8, 71.6, 52.0, 49.3, 49.0, 48.5, 33.0, 32.0.

m/z (ESI–MS) 191.1 [M+H]+.

Synthesis of compound 41

A 50 mL round bottom flask was charged with sodium hydride (0.077 g, 1.934 mmol), dimethylformamide (10 mL) and 18-crown-6 (0.025 mL, 0.117 mmol) and cooled to 0 °C under nitrogen atmosphere. 2,2,2-trifluoro-N-(2-formylphenyl)acetamide25n (0.4 g, 1.842 mmol) dissolved in dimethylformamide (5 mL) was added to the solution dropwise. The solution was stirred for 20 min at room temperature, then (E)-ethyl 4-bromobut-2-enoate (0.381 mL, 2.211 mmol) dissolved in dimethylformamide (5 mL) was added dropwise. The mixture was heated at 60 °C for 4 h. After this time, the solvent was removed in vacuo and the residue was dissolved in dichloromethane (20 mL). The organic layer was washed with distilled water (1 × 15mL) and brine (1 × 15 mL) and dried over Na2SO4. The solid was filtered off, solvent removed in vacuo and purified by silica gel chromatography. (E)-Ethyl 4-(2,2,2-trifluoro-N-(2-formylphenyl)acetamido)but-2-enoate was isolated in 42% yield (Rf = 0.29 in hexanes/EtOAc 80:20 v/v).

A 10 mL round bottom flask fitted with a magnetic stir bar was charged with (E)-Ethyl 4-(2,2,2-trifluoro-N-(2-formylphenyl)acetamido)but-2-enoate (0.050 g, 0.152 mmol) and absolute ethanol (1.5 mL). To this stirring mixture, 1 mL of a 5% w/v aqueous sodium bicarbonate solution was added dropwise, resulting in the formation of a precipitate. The resulting mixture was heated at reflux until a homogenous solution resulted. This solution was then removed from its heat source and allowed to stir for 2 hours. After this time, 10 mL of brine was added to the solution and the product was extracted with dichloromethane (3 × 10 mL). The organic layer was washed again with brine (10 mL), dried over sodium sulfate and filtered and the solvent was subsequently removed in vacuo. The crude mixture was loaded onto a column and purified by silica gel chromatography. Compound 41 was obtained as a yellow oil in 90% yield (Rf = 0.23 in hexanes/EtOAc 90:10 v/v).

IR (KBr) 3334, 2981, 2747, 1717, 1659, 1580, 1520, 1432, 1276, 1180, 1041, 753 cm−1.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 9.84 (s, 1H), 8.55 (br s, 1H), 7.50 (dd, J = 7.7, 1.6 Hz, 1H), 7.42–7.34 (m, 1H), 7.00 (app dt, J = 15.7, 4.4 Hz, 1H), 6.78–6.70 (m, 1H), 6.58 (d, J = 8.5 Hz, 1H), 5.99 (dt, J = 15.7, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 4.17 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 4.09–4.05 (m, 2H), 1.26 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 3H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 194.2, 166.0, 150.0, 143.9, 136.7, 135.9, 121.9, 118.7, 115.7, 110.9, 60.4, 43.2, 14.2.

m/z (ESI–MS) 234.0 [M+H]+.

Compound 42

A 10 mL round-bottom flask fitted with a magnetic stir bar was charged with aminobenzaldehyde 41 (0.117 g, 0.5 mmol), absolute ethanol (2 mL) and pyrrolidine (0.123 mL, 1.5 mmol). The resulting mixture was heated at reflux for 14 hours and the solvent was subsequently removed in vacuo. The crude mixture was loaded onto a column and purified by silica gel chromatography. Compound 42 was obtained as a yellow oil in 61% yield (Rf = 0.19 in hexanes/EtOAc 75:25 v/v).

IR (KBr) 3420, 3065, 2982, 2938, 1733, 1571, 1497, 1465, 1368, 1340, 1255, 1158, 1030, 908, 788, 753, 638, 616 cm−1.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 8.84 (d, J = 2.2 Hz, 1H), 8.08 (app d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 8.07–8.05 (m, 1H), 7.77 (app d, J = 8.3 Hz, 1H), 7.68 (ddd, J = 8.3, 7.2, 1.1 Hz, 1H), 7.52 (app t, J = 7.2 Hz, 1H), 4.17 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 2H), 3.79 (s, 2H), 1.25 (app td, J = 7.1, 0.4 Hz, 3H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 170.6, 151.6, 147.2, 132.7, 129.2, 129.1, 127.8, 127.5, 127.0, 126.8, 61.2, 38.7, 14.2.

m/z (ESI–MS) 216.2 [M+H]+.

Compound 51

Following the general reflux procedure, 51 was obtained from 2-amino-3,5-dibromobenzaldehyde (0.5 mmol) and 2-allylpyrrolidine (50)25o after 24 h heating at reflux in absolute ethanol (2 mL). 51 and 52 were obtained together as an off-white solid in 15% and 3% yields, respectively. In addition, 54 and 55 were obtained in 29% and 27% yields, respectively. Characterization data of 51: (Rf = 0.13 in hexanes/EtOAc 90:10 v/v).

mp: 75–77 °C.

IR (KBr) 3414, 2889, 1593, 1490, 1341, 1109, 914, 863 cm−1.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 7.38 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 6.99 (s, 1H), 5.88–5.69 (m, 1H), 5.22–4.97 (comp, 2H), 4.78 (d, J = 4.1 Hz, 1H), 4.33–4.11 (comp, 2H), 3.78 (d, J = 17.1 Hz, 1H), 2.89–2.78 (m, 1H), 2.56–2.43 (m, 1H), 2.43–2.34 (m, 1H), 2.28–1.95 (comp, 2H), 1.83–1.54 (comp, 2H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 139.5, 135.3, 132.2, 128.8, 120.4, 116.8, 108.0, 107.5, 71.7, 57.6, 46.2, 38.8, 31.2, 27.8.

m/z (ESI–MS) 373.2 [M+H]+.

Deoxyvasicine

To a 25 mL round bottom flask was added compound 9k (0.174 g, 1.0 mmol) and THF (5 mL). The mixture was cooled to −78 °C under nitrogen atmosphere in a dry ice/acetone bath and stirred for 5 min. Butyllithium solution (2.5 M in hexanes, 0.42 mL, 1.05 equiv) was added to the mixture and was allowed to stir 1 h. I2 (0.329 g, 1.3 mmol) dissolved in THF (5 mL) was added to the solution dropwise and this was stirred for 30 min. Triethylamine (0.418 mL, 3 mmol) was added to the solution, which was then allowed to warm to room temperature and stir for 30 min. The mixture was then quenched with distilled water (15 mL), extracted with EtOAc (3 × 15 mL) and the solvent was removed in vacuo. The resulting residue was purified by silica gel chromatography with NEt3/MeOH/EtOAc (1:10:89) as the eluent. Deoxyvasicine was obtained as a tan solid in 85% yield and matched reported spectroscopic data in all regards.25e

Vasicine

To a 10 mL round bottom flask was added compound 37 (0.014 g, 0.074 mmol) and Et2O (1 mL). The mixture was cooled to −78 °C under nitrogen atmosphere in a dry ice/acetone bath and stirred for 5 min. Butyllithium solution (2.5 M in hexanes, 0.031 mL, 1.05 equiv) was added to the mixture and was allowed to stir 1 h. I2 (0.021 g, 0.081 mmol) dissolved in Et2O (1 mL) was added to the solution dropwise and this was stirred for 30 min. Triethylamine (0.031 mL, 0.221 mmol) was added to the solution, which was then allowed to The mixture was then quenched with distilled water (5 mL), extracted with EtOAc (3 × 5 mL) and the solvent was removed in vacuo. The resulting residue was purified by silica gel chromatography with NEt3/MeOH/EtOAc (1:10:89) as the eluent. Vasicine was obtained as a tan solid in 79% yield (Rf = 0.16 in i-PrNH2/MeOH/EtOAc 2:10:88 v/v/v) and matches reported spectroscopic data in all regards.25f

Compound 61

Following the general microwave procedure, 61 was obtained from 2-amino-3,5-dibromobenzaldehyde (0.25 mmol) and trans-4-hydroxy-L-proline (2.1 equiv) after 30 min at 150 °C in n-butanol (1 mL). 61 was isolated as a tan solid in 50% yield (1:1.2 mixture of diasteromers) (Rf = 0.19 in EtOAc/MeOH 95:5 v/v).

mp: 122–125 °C.

IR (KBr) 3302, 2940, 2819, 2360, 2342, 1596, 1483, 1375, 1285, 1258, 1152, 1023, 862, 683 cm−1.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 7.43 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.39 (d, J = 2.1 Hz, 1H), 7.04 (s, 1H), 7.01 (s, 1H), 4.63 (dd, J = 5.4, 2.2 Hz, 1H), 4.58–4.52 (m, 1H), 4.52–4.45 (m, 1H), 4.38 (br s, 1H), 4.34–4.29 (m, 1H), 4.22 (d, J = 16.6 Hz, 1H), 4.17 (br s, 1H), 4.07 (d, J = 15.7 Hz, 1H), 3.84–3.72 (comp, 2H), 3.22 (dd, J = 10.2, 6.4 Hz, 1H), 3.07 (dd, J = 10.0, 5.6 Hz, 1H), 2.83–2.73 (comp, 2H), 2.48 (ddd, J = 13.7, 7.6, 5.1 Hz, 1H), 2.23 (ddd, J = 14.0, 7.3, 2.3 Hz, 1H), 2.15 (ddd, J = 14.0, 5.3, 2.8 Hz, 1H), 1.88–1.79 (m, 1H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 139.1(3), 139.1(0), 132.5, 132.3, 129.1, 129.0, 122.0, 121.0, 109.9, 109.4, 108.6, 108.4, 70.9, 70.7, 70.5, 69.9, 60.0, 59.0, 49.4, 48.4, 44.5, 43.3.

m/z (ESI–MS) 349.2 [M+H]+.

Compound 62

To a 10 mL round bottom flask was added 61 (0.05 g, 0.144 mmol), acetone (4 mL) and potassium permanganate (0.068 g, 0.431 mmol). The solution was heated at reflux for 2 h, after which time the solution was cooled to room temperature and filtered through a pad of celite. The filtrate was washed with acetone (10 mL) and methanol (10 mL) and solvent was removed in vacuo. The residue was purified by column chromatography, resulting in the isolation of (R)-5,7-dibromo-2-hydroxy-2,3-dihydropyrrolo[2,1-b]quinazolin-9(1H)-one as a tan solid in 64% yield (Rf = 0.28 in EtOAc).

To a 10 mL round bottom flask was added (R)-5,7-dibromo-2-hydroxy-2,3-dihydropyrrolo[2,1-b]quinazolin-9(1H)-one (0.0073 g, 0.02 mmol), methanol (1 mL), 10% Pd/C (2.158 mg, 0.1 equiv) and triethylamine (8.48 µL, 3 equiv). The atmosphere was evacuated and replaced with hydrogen gas using a three-way glass adaptor. The solution was stirred for 2 h and was then filtered. The filtrate was washed with methanol (15 mL) and the solvent was removed in vacuo. 62 was obtained as a white solid in 98% yield (Rf = 0.16 in EtOAc/MeOH v/v).

mp: 168–171 °C.

[α]D25 −35.0 (c 0.167, CHCl3).

IR (KBr) 3395, 2917, 2849, 2357, 1682, 1633, 1607, 1454, 1392, 1277, 773 cm−1.

1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) 8.21 (app d, J = 8.0 Hz, 1H), 7.75–7.67 (m, 1H), 7.61 (app d, J = 8.2 Hz, 1H), 7.43 (app t, J = 7.5 Hz, 1H), 4.87–4.77 (m, 1H), 4.32 (app d, J = 13.2 Hz, 1H), 4.21 (dd, J = 13.2, 4.8 Hz, 1H), 3.40 (dd, J = 17.5, 5.7 Hz, 1H), 3.18 (app d, J = 17.5 Hz, 1H), 2.92 (br s, 1H).

13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 160.9, 157.5, 148.8, 134.3, 126.7, 126.5, 126.4, 120.5, 65.8, 55.2, 42.3.

m/z (ESI–MS) 203.0 [M+H]+.

Acknowledgment

Financial support from the NIH–NIGMS (grant R01GM101389-01) is gratefully acknowledged. Partial support (microwave purchase) was provided by the National Science Foundation through grant CHE-0911192. A.Y.P. gratefully acknowledges financial support from the Russian Federation President Grant (order N2057). D.S. is a fellow of the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation and the recipient of an Amgen Young Investigator Award.

Biographies

Matthew T. Richers was born in Scotch Plains, NJ in 1987. In 2009, he obtained his B.Sc. in chemistry at The College of New Jersey. He is currently pursuing a Ph.D. in organic chemistry at Rutgers University in the laboratory of Prof. Daniel Seidel. His research focuses on the facile synthesis of nitrogen-containing heterocyclic compounds.

Indubhusan Deb was born in West Bengal, India. He obtained his B.Sc. (Honors in Chemistry) degree from the University of Calcutta and his M.Sc. degree from Banaras Hindu University in 2002. He performed his graduate work with Prof. I. N. N. Namboothiri at the Indian Institute of Technology Bombay and received his Ph.D. in 2008. He subsequently moved to Rutgers University where he carried out postdoctoral research with Prof. Daniel Seidel. Since 2011, he is pursuing postdoctoral research in Prof. Naohiko Yoshikai’s research group at Nanyang Technological University, Singapore, where his research is focused on transition metal catalyzed C–H bond functionalization for the synthesis of heterocycles.

Alena Yu. Platonova was born in Russia in 1987. She received both her B.Sc. (2008) and M.Sc. (2010) degrees from the Ural State Technical University and is currently conducting her Ph.D. research under the supervision of Prof. Yu. Yu. Morzherin. In 2011 Alena joined the group of Prof. Daniel Seidel at Rutgers University for a ten-month internship as a Russian Federation President Fellow. Her research interests are focused on the synthetic chemistry of nitrogen-containing heterocycles.

Chen Zhang was born in Fuzhou (P. R. of China) in 1982. He received his B.Sc. degree from the University of Science and Technology of China in 2005. In September of 2005, Chen joined the Seidel group at Rutgers University and received his Ph.D. in 2010. From 2010–2011, he performed his postdoctoral research in the group of Prof. Scott E. Denmark at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. Chen is currently conducting research in medicinal chemistry at Xizang Haisco Pharmaceutical Group CO., LTD in China.

Daniel Seidel was born in Mühlhausen, Thüringen (Germany) and studied chemistry at the Friedrich-Schiller-Universität Jena (Diplom 1998). His Ph.D. research at the University of Texas at Austin (1998–2002) under the supervision of Prof. Jonathan L. Sessler involved the development of new methods for the synthesis of expanded porphyrin analogues. From 2002–2005, Daniel was an Ernst Schering Postdoctoral Fellow in the group of Prof. David A. Evans at Harvard University. He started his independent career at Rutgers University in August of 2005 and was promoted to Associate Professor with tenure in 2011. Research in his group is focused on new concepts for asymmetric catalysis and synthetic methodology.

References

- 1.Selected reviews on amine α-functionalization: Murahashi S-I. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 1995;34:2443. Doye S. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2001;40:3351. doi: 10.1002/1521-3773(20010917)40:18<3351::aid-anie3351>3.0.co;2-b. Tobisu M, Chatani N. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:1683. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503866. Campos KR. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2007;36:1069. doi: 10.1039/b607547a. Murahashi S-I, Zhang D. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;37:1490. doi: 10.1039/b706709g. Li C-J. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009;42:335. doi: 10.1021/ar800164n. Jazzar R, Hitce J, Renaudat A, Sofack-Kreutzer J, Baudoin O. Chem. Eur. J. 2010;16:2654. doi: 10.1002/chem.200902374. Yoo W-J, Li C-J. Top. Curr. Chem. 2010;292:281. doi: 10.1007/128_2009_17. Yeung CS, Dong VM. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1215. doi: 10.1021/cr100280d. Sun C-L, Li B-J, Shi Z-J. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1293. doi: 10.1021/cr100198w. Liu C, Zhang H, Shi W, Lei AW. Chem. Rev. 2011;111:1780. doi: 10.1021/cr100379j. Wendlandt AE, Suess AM, Stahl SS. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:11062. doi: 10.1002/anie.201103945. Klussmann M, Jones KM. Synlett. 2012;23:159. Zhang C, Tang CH, Jiao N. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2012;41:3464. doi: 10.1039/c2cs15323h. Mitchell EA, Peschiulli A, Lefevre N, Meerpoel L, Maes BUW. Chem. Eur. J. 2012;18:10092. doi: 10.1002/chem.201201539. Pan SC. Beilstein J. Org. Chem. 2012;8:1374. doi: 10.3762/bjoc.8.159.

- 2.a) Burns NZ, Baran PS, Hoffmann RW. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:2854. doi: 10.1002/anie.200806086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Newhouse T, Baran PS, Hoffmann RW. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009;38:3010. doi: 10.1039/b821200g. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pinnow J. Ber. 1895;28:3039. See also: Ruiz MDR, Vasella A. Helv. Chim. Acta. 2011;94:785.

- 4.a) Meth-Cohn O, Suschitzky H. Adv. Heterocycl. Chem. 1972;14:211. [Google Scholar]; b) Verboom W, Reinhoudt DN. Recl. Trav. Chim. Pays-Bas. 1990;109:311. [Google Scholar]; c) Meth-Cohn O. Adv. Heterocycl. Chem. 1996;65:1. [Google Scholar]; d) Quintela JM. Recent Res. Devel. Org. Chem. 2003;7:259. [Google Scholar]; e) Matyus P, Elias O, Tapolcsanyi P, Polonka-Balint A, Halasz-Dajka B. Synthesis. 2006:2625. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Meth-Cohn O, Naqui MA. Chem. Commun. 1967:1157. See also: Ryabukhin SV, Plaskon AS, Volochnyuk DM, Shivanyuk AN, Tolmachev AA. J. Org. Chem. 2007;72:7417. doi: 10.1021/jo0712087. Che X, Zheng L, Dang Q, Bai X. Synlett. 2008:2373.

- 6.a) Verboom W, Reinhoudt DN, Visser R, Harkema S. J. Org. Chem. 1984;49:269. [Google Scholar]; b) Verboom W, Hamzink MRJ, Reinhoudt DN, Visser R. Tetrahedron Lett. 1984;25:4309. [Google Scholar]; c) Nijhuis WHN, Verboom W, Reinhoudt DN, Harkema S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:3136. [Google Scholar]; d) Nijhuis WHN, Verboom W, Abu ElFadl A, Harkema S, Reinhoudt DN. J. Org. Chem. 1989;54:199. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mori K, Ohshima Y, Ehara K, Akiyama T. Chem. Lett. 2009;38:524. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang C, Murarka S, Seidel D. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:419. doi: 10.1021/jo802325x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Overview of aminal-forming reactions: Hiersemann M. In: Comprehensive Organic Functional Group Transformations II. Katritzky ART, Richard JK, editors. Vol. 4. Oxford, UK: Elsevier Ltd; 2005. p. 411.

- 10.Selected recent examples of oxidative amine α-aminations: Zhang Y, Fu H, Jiang Y, Zhao Y. Org. Lett. 2007;9:3813. doi: 10.1021/ol701715m. Liu XW, Zhang YM, Wang L, Fu H, Jiang YY, Zhao YF. J. Org. Chem. 2008;73:6207. doi: 10.1021/jo800624m. Xuan J, Cheng Y, An J, Lu L-Q, Zhang X-X, Xiao W-J. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:8337. doi: 10.1039/c1cc12203g. Mao XR, Wu YZ, Jiang XX, Liu XH, Cheng YX, Zhu CJ. RSC Adv. 2012;2:6733. Lao ZQ, Zhong WH, Lou QH, Li ZJ, Meng XB. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2012;10:7869. doi: 10.1039/c2ob26430g. Yan YZ, Zhang YH, Feng CT, Zha ZG, Wang ZY. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:8077. doi: 10.1002/anie.201203880. Xia QQ, Chen WZ. J. Org. Chem. 2012;77:9366. doi: 10.1021/jo301568e.

- 11.a) Friedländer P. Ber. 1882;15:2572. [Google Scholar]; b) Marco-Contelles J, Perez-Mayoral E, Samadi A, Carreiras MD, Soriano E. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:2652. doi: 10.1021/cr800482c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.a) Zhang C, De CK, Mal R, Seidel D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008;130:416. doi: 10.1021/ja077473r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b) Zhang C, De CK, Seidel D. Org. Synth. 2012;89:274. [Google Scholar]; c) Dieckmann A, Richers MT, Platonova AY, Zhang C, Seidel D, Houk KN. submitted. doi: 10.1021/jo400483h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Other examples of redox-neutral amine α-functionalization from our group: Murarka S, Zhang C, Konieczynska MD, Seidel D. Org. Lett. 2009;11:129. doi: 10.1021/ol802519r. Murarka S, Deb I, Zhang C, Seidel D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:13226. doi: 10.1021/ja905213f. Zhang C, Seidel D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:1798. doi: 10.1021/ja910719x. Deb I, Seidel D. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;51:2945. Haibach MC, Deb I, De CK, Seidel D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:2100. doi: 10.1021/ja110713k. Zhang C, Das D, Seidel D. Chem. Sci. 2011;2:233. Deb I, Das D, Seidel D. Org. Lett. 2011;13:812. doi: 10.1021/ol1031359. Deb I, Coiro DJ, Seidel D. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:6473. doi: 10.1039/c1cc11560j. Das D, Richers MT, Ma L, Seidel D. Org. Lett. 2011;13:6584. doi: 10.1021/ol202957d. Ma L, Chen W, Seidel D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:15305. doi: 10.1021/ja308009g. Das D, Sun AX, Seidel D. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013;52 doi: 10.1002/anie.201300021.

- 14.Selected articles on redox-neutral amine α-functionalization: Pastine SJ, McQuaid KM, Sames D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2005;127:12180. doi: 10.1021/ja053337f. Ryabukhin SV, Plaskon AS, Volochnyuk DM, Shivanyuk AN, Tolmachev AA. Synthesis. 2007:2872. doi: 10.1021/jo0712087. Indumathi S, Kumar RR, Perumal S. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:1411. Belskaia NP, Deryabina TG, Koksharov AV, Kodess MI, Dehaen W, Lebedev AT, Bakulev VA. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:9128. Oda M, Fukuchi Y, Ito S, Thanh NC, Kuroda S. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:9159. Barluenga J, Fananas-Mastral M, Aznar F, Valdes C. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2008;47:6594. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802268. Polonka-Balint A, Saraceno C, Ludányi K, Bényei A, Matyus P. Synlett. 2008:2846. Ruble JC, Hurd AR, Johnson TA, Sherry DA, Barbachyn MR, Toogood PL, Bundy GL, Graber DR, Kamilar GM. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:3991. doi: 10.1021/ja808014h. Cui L, Peng Y, Zhang L. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:8394. doi: 10.1021/ja903531g. Vadola PA, Sames D. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:16525. doi: 10.1021/ja906480w. Pahadi NK, Paley M, Jana R, Waetzig SR, Tunge JA. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009;131:16626. doi: 10.1021/ja907357g. Zhou G, Zhang J. Chem. Commun. 2010;46:6593. doi: 10.1039/c0cc01946a. Mao H, Xu R, Wan J, Jiang Z, Sun C, Pan Y. Chem. Eur. J. 2010;16:13352. doi: 10.1002/chem.201001896. Kang YK, Kim SM, Kim DY. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:11847. doi: 10.1021/ja103786c. Dunkel P, Turos G, Benyei A, Ludanyi K, Matyus P. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:2331. Zhou GH, Liu F, Zhang JL. Chem. Eur. J. 2011;17:3101. doi: 10.1002/chem.201100019. Barluenga J, Fananas-Mastral M, Fernandez A, Aznar F. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2011:1961. Mori K, Ehara K, Kurihara K, Akiyama T. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011;133:6166. doi: 10.1021/ja2014955. Ghavtadze N, Narayan R, Wibbeling B, Wuerthwein E-U. J. Org. Chem. 2011;76:5185. doi: 10.1021/jo200896y. Cao WD, Liu XH, Wang WT, Lin LL, Feng XM. Org. Lett. 2011;13:600. doi: 10.1021/ol1028282. Xue XS, Yu A, Cai Y, Cheng J-P. Org. Lett. 2011;13:6054. doi: 10.1021/ol2025247. He Y-P, Du Y-L, Luo S-W, Gong L-Z. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011;52:7064. Jurberg ID, Peng B, Woestefeld E, Wasserloos M, Maulide N. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012;51:1950. doi: 10.1002/anie.201108639. Zhang L, Chen L, Lv J, Cheng J-P, Luo S. Chem. Asian J. 2012;7:2569. doi: 10.1002/asia.201200674. Mahoney SJ, Fillion E. Chem. Eur. J. 2012;18:68. doi: 10.1002/chem.201103155. Chen LJ, Zhang L, Lv J, Cheng J-P, Luo SZ. Chem. Eur. J. 2012;18:8891. doi: 10.1002/chem.201201532. Sugiishi T, Nakamura H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:2504. doi: 10.1021/ja211092q. Han Y-Y, Han W-Y, Hou X, Zhang X-M, Yuan W-C. Org. Lett. 2012;14:4054. doi: 10.1021/ol301559k.

- 15.Zheng L, Yang F, Dang Q, Bai X. Org. Lett. 2008;10:889. doi: 10.1021/ol703049j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Polshettiwar V, Varma RS. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:7165. [Google Scholar]

- 17.a) McGeachin SG. Can. J. Chem. 1966;44:2323. [Google Scholar]; b) Jircitano AJ, Sommerer SO, Shelley JJ, Westcott BL., Jr Acta Crystallogr., Sect. C: Cryst. Struct. Commun. 1994:C50–445. [Google Scholar]; c) Kolchinski AG. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2004;174:207. [Google Scholar]; d) Xiao XS, Fanwick PE, Cushman M. Synth. Commun. 2004;34:3901. [Google Scholar]; e) Sridharan V, Ribelles P, Ramos MT, Menendez JC. J. Org. Chem. 2009;74:5715. doi: 10.1021/jo900965f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Selected reviews on azomethine ylide chemistry: Padwa A. Vol. 1. Wiley; New York, N. Y.: 1984. 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition Chemistry. Padwa A. Editor 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition Chemistry. Vol. 2. Wiley; New York, N. Y.; 1984. Padwa A, Pearson WH. Synthetic Applications of 1,3-Dipolar Cycloaddition Chemistry Toward Heterocycles and Natural Products. Vol. Wiley; Chichester, U. K.: 2002. p. 59. Najera C, Sansano JM. Curr. Org. Chem. 2003;7:1105. Coldham I, Hufton R. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:2765. doi: 10.1021/cr040004c. Pandey G, Banerjee P, Gadre SR. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:4484. doi: 10.1021/cr050011g. Pinho e Melo TMVD. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2006:2873. Bonin M, Chauveau A, Micouin L. Synlett. 2006:2349. Nair V, Suja TD. Tetrahedron. 2007;63:12247. Najera C, Sansano JM. Top. Heterocycl. Chem. 2008;12:117. Stanley LM, Sibi MP. Chem. Rev. 2008;108:2887. doi: 10.1021/cr078371m. Nyerges M, Toth J, Groundwater PW. Synlett. 2008:1269. Pineiro M, Pinho e Melo TMVD. Eur. J. Org. Chem. :5287. Burrell AJM, Coldham I. Curr. Org. Synth. 2010;7:312. Anac O, Gungor FS. Tetrahedron. 2010;66:5931. Adrio J, Carretero JC. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:6784. doi: 10.1039/c1cc10779h.

- 19.Related reactions that involve decarboxylative amino acid functionalization: Cohen N, Blount JF, Lopresti RJ, Trullinger DP. J. Org. Chem. 1979;44:4005. Bi H-P, Zhao L, Liang Y-M, Li C-J. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2009;48:792. doi: 10.1002/anie.200805122. Bi H-P, Chen W-W, Liang Y-M, Li C-J. Org. Lett. 2009;11:3246. doi: 10.1021/ol901129v. Bi H-P, Teng Q, Guan M, Chen W-W, Liang Y-M, Yao X, Li C-J. J. Org. Chem. 2010;75:783. doi: 10.1021/jo902319h. Yan Y, Wang Z. Chem. Commun. 2011;47:9513. doi: 10.1039/c1cc12885j. Wang Q, Wan C, Gu Y, Zhang J, Gao L, Wang Z. Green Chem. 2011;13:578. Xu W, Fu H. J. Org. Chem. 2011;76:3846. doi: 10.1021/jo2002227. Yang D, Zhao D, Mao L, Wang L, Wang R. J. Org. Chem. 2011;76:6426. doi: 10.1021/jo200981h. Wang Q, Zhang S, Guo FF, Zhang BQ, Hu P, Wang ZY. J. Org. Chem. 2012;77:11161. doi: 10.1021/jo302299u.

- 20.a) Aly MF, Ardill H, Grigg R, Leongling S, Rajviroongit S, Surendrakumar S. Tetrahedron Lett. 1987;28:6077. [Google Scholar]; b) Azizian J, Karimi AR, Kazemizadeh Z, Mohammadi AA, Mohammadizadeh MR. J. Org. Chem. 2005;70:1471. doi: 10.1021/jo0486692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c) Yadav JS, Reddy BVS, Jain R, Reddy CS. Tetrahedron Lett. 2007;48:3295. [Google Scholar]; d) Sridhar R, Srinivas B, Kumar VP, Reddy VP, Kumar AV, Rao KR. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2008;350:1489. [Google Scholar]; e) Karimi AR, Behzadi F, Amini MM. Tetrahedron Lett. 2008;49:5393. [Google Scholar]; f) Kumar MA, Krishna AB, Babu BH, Reddy CB, Reddy CS. Synth. Commun. 2008;38:3456. [Google Scholar]; g) Meshram HM, Prasad BRV, Kumar DA. Tetrahedron Lett. 2010;51:3477. [Google Scholar]; h) Reddy VP, Kumar AV, Rao KR. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011;52:777. [Google Scholar]; i) Kumar AV, Rao KR. Tetrahedron Lett. 2011;52:3237. [Google Scholar]; j) Mao H, Wang SC, Yu P, Lv HQ, Xu RS, Pan YJ. J. Org. Chem. 2011;76:1167. doi: 10.1021/jo102218v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.For selected reports on ortho-aza-quinone methides, see: Steinhagen H, Corey EJ. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1999;38:1928. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-3773(19990712)38:13/14<1928::AID-ANIE1928>3.0.CO;2-1. Wojciechowski K. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2001:3587. Modrzejewska H, Wojciechowski K. Synlett. 2008:2465. Wang C, Pahadi N, Tunge JA. Tetrahedron. 2009;65:5102. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2009.04.071. Robertson FJ, Kenimer BD, Wu J. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:4327.