Abstract

Racial disparities in mental health outcomes have been widely documented in noninstitutionalized community psychiatric samples, but few studies have specifically examined the effects of race among individuals with the most severe mental illnesses. A sample of 925 individuals hospitalized for severe mental illness was followed for a year after hospital discharge to examine the presence of disparities in mental health outcomes between African American and white individuals diagnosed with a severe psychiatric condition. Results from a series of individual growth curve models indicated that African American individuals with severe mental illness experienced significantly less improvement in global functioning, activation, and anergia symptoms and were less likely to return to work in the year following hospitalization. Racial disparities persisted after adjustment for sociodemographic and diagnostic confounders and were largely consistent across gender, socioeconomic status, and psychiatric diagnosis. Implications for social work research and practice with minorities with severe mental illness are discussed.

Keywords: ethnicity, mental health outcomes, race, schizophrenia, severe mental illness

Race has been described as one of the most critical factors for understanding social problems in the contemporary United States (Gallagher, 2007). Within the past several decades, social work researchers have begun turning to the issue of race to understand the disparities related to mental health care of those who are the most disabled in our society (Newhill & Harris, 2008). In a comprehensive report on the status of mental health care for racial and ethnic minorities in the United States, former Surgeon General David Satcher concluded that minorities suffer a disproportionate burden of mental illness because they often have less access to services than other Americans, receive lower quality care, and are less likely to seek help when they are in distress. The report concluded that there is a large gap between the need for services and the services actually provided. Major contributors to these disparities include poverty, stigma, and discrimination (Rank, 2004; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS], 2001; Wilson, 2009).

Although the documentation of racial disparities in mental health services and outcomes among the general population of people with mental illness provided by the surgeon general's report was an important advance for the field, little is known about how these broader findings apply to individuals with severe and persistent mental illness. Severe and persistent mental illnesses (for example, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and recurrent major depression) often produce the most serious and long-term psychosocial disabilities (Murray & Lopez, 1996). Many individuals with these illnesses also live in poverty and thus are usually dependent on public mental health services for care (Hudson, 2005). The question of whether race remains a factor in this disabled and frequently impoverished population is of critical importance for ensuring that effective services are available to those most in need. To date, however, most research on racial disparities in mental health services and outcomes has focused on noninstitutionalized community samples, such as the National Comorbidity Studies (Kessler, Mcgonagle, Zhao, & Nelson, 1994) and the Healthcare for Communities Survey (Sturm et al., 1999), which frequently excluded those with the most severe and persistent mental illnesses, such as schizophrenia.

Of the studies that have examined racial disparities and severe mental illness, most have focused almost exclusively on the overdiagnosis of certain mental health conditions and disparities in the use of certain forms of treatment, such as inpatient care and depot pharmacotherapy. These studies have consistently found that African Americans with severe mental illness tend to be disproportionately diagnosed with psychotic conditions such as schizophrenia, even though there is little to no difference in actual prevalence rates (Buchanan & Carpenter, 2005), and less frequently diagnosed with mood disorders compared with their white counterparts (Barnes, 2008; Snowden & Cheung, 1990; Strakowski, Shelton, & Kolbrener, 1993). In addition, racial minorities, particularly African Americans, are prescribed more psychotropic medications at higher doses, are more likely to receive injectable medicines (Citrome, Levine, & Allingham, 1996; Segal, Bola, & Watson, 1996), and are more likely to be hospitalized involuntarily than white Americans (Rosenfield, 1984). Despite these differences, some studies have shown that racial minority individuals with severe mental illness use similar (if not higher) rates of inpatient and outpatient mental health services (Folsom et al., 2007; Kilbourne et al., 2005), although such individuals are disproportionately underrepresented in case management services (Barrio et al., 2003). In general, research has shown that at some of the lowest socioeconomic levels, the service gap between white and nonwhite people can shrink (for example, Alegría et al., 2002). One compelling explanation for this phenomenon is that most people with severe mental illness are eligible for Medicaid, which may equalize access to care by removing the well-documented racial disparities in private insurance coverage (Snowden & Thomas, 2000).

Although the picture of racial disparities in mental health services among people with severe mental illness is clearly complex and evidence is only recently emerging with regard to Hispanic and Latino populations, findings have consistently indicated that African Americans with severe mental illness receive a different standard of care. The treatment of such individuals disproportionately consists of greater use of inpatient psychiatric services (Rosenfield, 1984; Snowden, Hastings, & Alvidrez, 2009), injectable medications (Shi et al., 2007), and less costly outpatient treatment options (Kuno & Rothbard, 2002). Although this does not necessarily mean that African Americans receive less care, the care they do receive may be suboptimal and less able to meet their needs. Unfortunately, the critical question of whether African Americans with severe mental illness experience less favorable mental health treatment outcomes has been infrequently addressed. One study by Gift, Harder, Ritzler, and Kokes (1985) examined 217 individuals hospitalized for a severe mental illness and followed these individuals for two years post–hospital discharge. They found that at two years' follow-up African American participants had greater psychotic symptoms after discharge than white participants. However, no information was provided on how these symptoms, which were significantly elevated at baseline, might have differentially changed over time between races. Another study by Chinman, Rosenheck, and Lam (2000) found that in a large sample of individuals with severe mental illness, white participants receiving case management services tended to experience greater reduction in symptoms than African Americans. Although such studies point to the possibility of disparities in important mental health outcomes between African American and white individuals with severe mental illness, most have made use of cross-sectional designs and have generally used modest sample sizes. In addition, few studies have examined outcomes other than symptom reduction, such as level and quality of community psychosocial functioning and employment, and most have not accounted for the confounding effects of socioeconomic status (SES) or differential psychiatric diagnosis.

In this research, we used individual growth curve modeling in a large longitudinal sample (N = 925) of African American and white individuals with severe mental illness to examine the presence of racial disparities in mental health outcomes after psychiatric hospital discharge. The study participants were then assessed in the community every 10 weeks for a year on a number of broad symptom and functioning domains, and racial differences in rates of improvement in these domains were examined after adjusting for socioeconomic, diagnostic, and other potential confounding variables.

METHOD

Participants

This research was conducted using existing data collected as part of the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study, the methods of which have been described in detail elsewhere (Monahan et al., 2001). Participants included individuals recruited from psychiatric inpatient units in three cities (Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania; Kansas City, Missouri; and Worcester, Massachusetts). Participants were included in the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study if they had been hospitalized for less than 21 days, spoke English as a primary language, were between the ages of 18 and 40, and carried a medical chart diagnosis of schizophrenia, schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, major depression, dysthymia, bipolar disorder, brief reactive psychosis, delusional disorder, alcohol or other drug abuse or dependence, or a personality disorder. In total, 1,695 patients were recruited, 1,136 (71%) of whom agreed to participate. Individuals who agreed to participate were younger, less likely to be diagnosed with schizophrenia, and more likely to be diagnosed with a substance use or personality disorder (Steadman et al., 1998). Of those individuals who participated, 925 (81%) had complete data available for at least one follow-up period and were either African American or Caucasian (only 2% [n = 21] of the sample was Hispanic, and thus these individuals were excluded from further analysis).

Among the 925 participants included from the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study, 70% were Caucasian and 30% were African American. Ages ranged between 18 and 40 years (M = 29.90, SD = 6.20), and 58% of the participants were male. Psychiatric diagnosis was evaluated using the Diagnostic and Statistic Manual of Mental Disorders, Third Edition Revised (DSM–III–R) checklist (J'anca & Helzer, 1990), with 55% of the sample diagnosed with mood disorders, 22% with substance use disorders, 21% with psychotic disorders, and 2% with a personality disorder and no Axis I disorder. Nearly half (42%) of the participants were diagnosed with both a psychiatric and substance use disorder. The majority of participants were voluntarily hospitalized (67%), and most had at least one previous psychiatric hospitalization (71%). Among these characteristics, African Americans were significantly older [t(923) = −2.25, p = .025], more likely to be diagnosed with psychotic disorders [χ2(3, N = 925) = 50.15, p < .001], and had lower SES [t(923) = 3.90, p < .001]. No other racial differences in demographic or clinical characteristics were found.

Measures

Mental Health Outcomes

Critical outcomes of mental health treatment and community functioning were assessed in the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study using a variety of measures of psychiatric symptomatology and functional outcome. Psychiatric symptomatology was measured using the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS) (Overall & Gorham, 1962), which has been widely used in psychiatric research and repeatedly shown to be a reliable and valid measure of psychopathology. The instrument consists of 18 items, rated on a scale from 1 = not present to 7 = very severe, assessing the symptom domains of thought disturbance (conceptual disorganization, hallucinatory behavior, unusual thought content, grandiosity), suspiciousness/hostility (hostility, suspiciousness, uncooperativeness), anergia (emotional withdrawal, motor retardation, blunted affect, disorientation), activation (excitement, tension, unusual mannerisms/posturing), and anxiety/depression (somatic concern, anxiety, guilt feelings, depressive mood), which have been supported by numerous factor-analytic studies (Shafer, 2005). The anergia domain assessed by the BPRS is reflective of the negative symptoms of schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, which encompass a deficit in cognitive and motivational functioning, such as reduced affect and social and emotional withdrawal.

Functional outcomes were assessed using the Global Assessment of Functioning (GAF) (Endicott, Spitzer, Fleiss, & Cohen, 1976) scale, a brief scale on activities of daily living (ADL) (Monahan et al., 2001) and self-reported competitive employment status. The GAF has been widely used to assess global functioning in people with psychiatric disorders and is used to assess the fifth Axis in the DSM, which covers functional impairment. The GAF consists of a global measure of functioning that is rated on a scale of 1 to 100, with 1 indicative of poor functioning and 100 indicative of excellent functioning. Ratings are anchored every 10 units (91–100, 81–90, and so on) and based on impairment in social, vocational/educational, and symptom domains. The ADL scale was created for the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study and consists of six items asking participants how much difficulty (from 0 = none to 3 = unable to do it) they have with completing their own housework, shopping, managing their finances, using transportation (for example, driving a car or riding a bus) cooking, and doing laundry. This scale demonstrated adequate internal consistency in this study (α = .75).

SES

SES was assessed to control for the presence of potentially large racial differences that might stem from differences in economic, educational, and occupational status. Hollingshead and Redlich's (1958) classic index was used to measure SES. This measure of SES has been widely used in the psychiatric and sociological literature and takes into account both education and occupation prior to hospitalization to compute an overall index of SES, with higher scores indicating greater SES.

Procedures

On recruitment to the MacArthur Violence Risk Assessment Study, participants were assessed while hospitalized using the aforementioned mental health outcome and socioeconomic measures. The same mental health outcome battery was then readministered every 10 weeks for one year to examine changes in symptomatology and functioning after hospital discharge. Of the 1,136 individuals who participated at baseline, 925 (81%) had at least some follow-up data available for analysis. Previous reports comparing the individuals available for follow-up with the complete sample assessed at baseline indicated that those who completed follow-up assessments were more likely to have bipolar disorder, less likely to have a history of substance abuse, less likely to be gravely disabled, and less likely to have a history of violence (Steadman et al., 1998). The majority (59%) of participants available at follow-up had complete data for all five study periods, 18% had follow-up data for four study periods, 9% for three study periods, 8% for two study periods, and 6% for one study period. No significant racial differences were observed between individuals with available follow-up data and those lost to attrition [χ2(1, N = 1,115) = .002, not significant] or between individuals with a greater percentage of follow-up data [χ2(4, N = 925) = 7.04, not significant]. Sensitivity analyses examining racial disparities in mental health outcomes after adjusting for attrition revealed no substantive change in results. All participants provided written informed consent prior to participation, and the study was reviewed annually by the institutional review boards of the participating sites.

Data Analysis

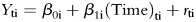

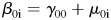

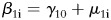

Individual growth curve modeling was used to examine differential trajectories of mental health outcomes between African American and white participants over the course of one year after hospital discharge. Individual growth curve modeling is a form of hierarchical linear modeling for repeated measures data, where multiple measurement occasions are nested within individuals (Raudenbush & Bryk, 2002). A typical unconditional growth model is presented in equations 1–3.

- Level 1:

1 - Level 2:

2

3

The level 1 equation represents scores on outcome Y for individual i at time t as a function of his or her intercept, β0i, and rate of change, β1i, plus error, rti. For this research, the growth covariate, Time, was coded such that 0 = baseline, 1 = follow-up 1, 2 = follow-up 2, and so on, so that the model intercept can be interpreted as the participant's initial status on Y. Equations for level 2 then represent a participant's initial status and rate of change on outcome Y as a function of the average initial status, γ00, and rate of change, γ10, for the sample plus individual variation in these parameters (that is, μ0i and μ1i). Variability in intercept and slope parameters is captured by T, a symmetrical 2 x 2 matrix containing variance components τ00, τ11, and τ01, reflecting the variance of the individual intercept and slope parameters as well as covariance between the intercept and slope parameters, respectively. Variability in these parameters can then be predicted by person-level covariates, such as race, in conditional growth models to determine how individual characteristics affect baseline levels and rates of change for outcomes of interest.

Analysis in this research proceeded by first fitting unconditional growth curve models for each mental health outcome domain assessed. Results of these models indicated significant variability in initial status and rates of change for all measured outcomes [all χ2(1–2, N = 925) > 31.00, all p < .001]. Subsequently, conditional growth models were constructed with race as a predictor of initial status and rates of change in mental health outcomes to examine racial disparities in outcomes during hospitalization and following hospital discharge. In addition, baseline age, sex, SES, and the presence of a psychotic diagnosis were all entered as confounding covariates that might account for racial differences in mental health outcome growth parameters, given the differences between races that emerged at baseline in a number of these characteristics and their likely effect on outcome. Psychiatric diagnosis was dichotomized into those with and without a psychotic disorder for the purposes of analysis. Baseline symptom severity or functional disability was also adjusted for in outcome analyses of symptomatology and functioning, respectively. The presence of primary or comorbid substance use was considered as a potential confounding covariate, given the higher proportion of African American participants who were diagnosed with substance use problems (69% versus 52%, χ2[1, N = 925] = 21.23, p < .001). However, substance use was not observed to be a consistent predictor of mental health outcomes in this sample above and beyond the other confounding covariates, and its inclusion in the models did not significantly alter the results. Consequently, a diagnosis of substance use problems was not included as a covariate in the final models. Finally, moderator analyses were used to examine the degree to which racial differences in mental health outcomes demonstrating significant disparities were constant across gender, SES, and psychiatric diagnosis.

All growth models were fit using restricted maximum likelihood with Gaussian distributions, with the exception of employment data, which were estimated using penalized quasi-likelihood estimates with a binomial distribution. A first-order autoregressive error structure suitable for longitudinal data was also used in linear mixed-effects models when appropriate. In addition, because employment data reflected reentry into the workforce after hospitalization, parameter estimates at baseline (Time = 0) were not appropriate, and thus intercept estimates reflect employment status at the first follow-up (Time = 1). Nonlinear transformations were used for skewed data, and continuous variables were transformed to a z metric to ease interpretation of model parameters. Missing data were handled during analysis using the expectation maximization approach when computing restricted maximum likelihood parameter estimates (Dempster, Laird, & Rubin, 1977). Hochberg's (1988) correction was applied between analyses to adjust for inference testing on multiple outcomes that might artificially inflate Type I error rates. All analyses were conducted using R version 2.5.0 (R Development Core Team, 2007).

RESULTS

Do Mental Health Outcomes Differ between African American and White Individuals after Hospital Discharge?

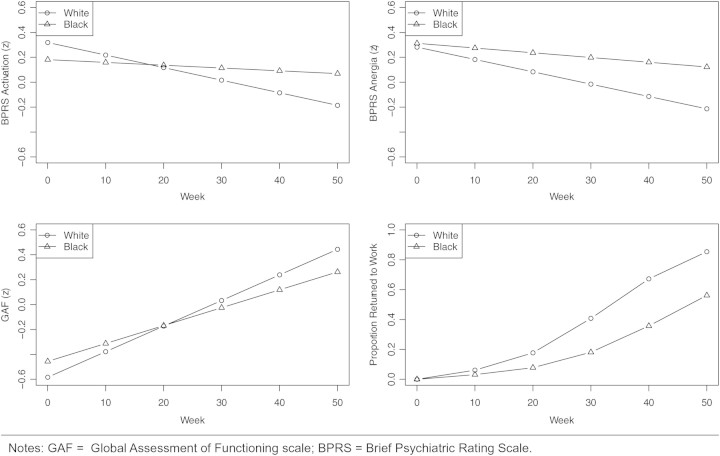

We began our analysis of racial disparities in mental health outcomes in the year following psychiatric discharge by examining the growth trajectories of African American and white participants for a variety of symptom and functional outcomes. As can be seen in Table 1, racial differences in symptomatology at baseline emerged seldom for the broad symptom domains assessed. The one exception to this pattern was activation symptoms, where a nonsignificant trend pointed to fewer mood elevation symptoms among African Americans at baseline compared with white Americans. Despite racial similarities in baseline symptomatology, several key differences emerged in longitudinal symptom improvement between races. Although positive psychotic symptoms of thought disturbance and suspiciousness were equally improved among both races, highly significant differences were found favoring white participates for improvement in activation and anergia or negative symptoms. As can be seen in Figure 1, white participants experienced substantial improvement in these symptom domains after hospital discharge, whereas African Americans showed little to no improvement in activation and anergia symptomatology. No significant differences between races were found in rates of improvement for anxiety/depression symptoms.

Table 1:

Racial Differences in Symptom Outcomes after Psychiatric Hospital Discharge among Individuals with Severe Mental Illness (N = 925)

| Thought Disturbance |

Hostility/Suspiciousness |

Activation |

Anergia |

Anxiety/Depression |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | B | SE | pa | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | B | SE | p |

| Age | 0.02 | 0.03 | .974 | −0.05 | 0.03 | .366 | −0.00 | 0.03 | .974 | 0.03 | 0.02 | .482 | 0.11 | 0.03 | <.001 |

| Sex (0 = female, 1 = male) | 0.06 | 0.05 | .560 | −0.12 | 0.05 | .091 | 0.08 | 0.05 | .347 | 0.02 | 0.05 | .703 | −0.25 | 0.06 | <.001 |

| SES | −0.08 | 0.03 | .024 | −0.04 | 0.03 | .425 | −0.03 | 0.03 | .425 | −0.11 | 0.02 | <.001 | 0.00 | 0.03 | .881 |

| Psychotic diagnosis | 1.26 | 0.07 | <.001 | 0.20 | 0.07 | .003 | 0.45 | 0.07 | <.001 | 0.58 | 0.06 | <.001 | −0.55 | 0.07 | <.001 |

| Race (0 = white, 1 = AA) | 0.02 | 0.06 | .718 | 0.12 | 0.06 | .171 | −0.14 | 0.06 | .103 | 0.03 | 0.05 | .718 | −0.04 | 0.06 | .718 |

| Time | −0.07 | 0.01 | <.001 | −0.09 | 0.01 | <.001 | −0.08 | 0.01 | <.001 | −0.07 | 0.01 | <.001 | −0.17 | 0.01 | <.001 |

| Time × Age | 0.01 | 0.01 | .558 | 0.02 | 0.01 | .081 | 0.02 | 0.01 | .081 | 0.01 | 0.01 | .429 | 0.00 | 0.01 | .733 |

| Time × Sex | 0.02 | 0.01 | .876 | 0.00 | 0.02 | .926 | −0.00 | 0.02 | .926 | 0.02 | 0.01 | .876 | 0.02 | 0.01 | .876 |

| Time × SES | 0.00 | 0.01 | .962 | −0.00 | 0.01 | .962 | −0.02 | 0.01 | .294 | −0.01 | 0.01 | .962 | −0.01 | 0.01 | .401 |

| Time × Psychotic diagnosis | −0.15 | 0.02 | <.001 | −0.06 | 0.02 | .009 | −0.03 | 0.02 | .108 | −0.07 | 0.02 | <.001 | 0.09 | 0.02 | <.001 |

| Time × Race | 0.03 | 0.02 | .170 | −0.02 | 0.02 | .204 | 0.08 | 0.02 | <.001 | 0.06 | 0.02 | .001 | −0.03 | 0.02 | .170 |

Notes: Continuous variables, with the exception of time, were placed on a z-metric to ease interpretation of parameters. SES = socioeconomic status; AA = African American.

ap Values are adjusted for the analysis of multiple symptom outcome measures using Hochberg's correction.

Figure 1:

One-Year Trajectories of Symptom and Functional Improvement among African American and White Participants after Psychiatric Hospital Discharge

With regard to functional outcome, both global assessment of functioning and ADL scores differed between African American and white participants at baseline, with African American participants demonstrating significantly greater functioning and daily living skills than white participants (see Table 2). Despite this functional advantage, improvement in both global assessment of functioning scores and employment outcomes were significantly different between races after adjusting for baseline differences in functioning. As shown in Figure 1, although both African American and white participants experienced substantial gains in global assessment of functioning scores, improvement in African American participants was both slower and more modest. When examining rates of return to competitive employment, a substantially greater proportion of white participants were reemployed by the end of the study, with 85% of white participants returning to work within a year after hospital discharge compared with only 56% of African American participants. These symptom and functional outcome disparities could not be accounted for by differences in SES. No significant differences emerged between races in improvement in activity of daily living scores. Taken together, these findings point to significant racial disparities in several, but not all, domains of symptom and functional outcomes studied among people with severe mental illness who are discharged to the community from psychiatric hospitalization.

Table 2:

Racial Differences in Functional Outcomes after Psychiatric Hospital Discharge among Individuals with Severe Mental Illness (N = 925)

| Global Assessment of Functioning |

Activities of Daily Living |

Return to Work |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Predictor | B | SE | pa | B | SE | p | B | SE | p |

| Age | −0.02 | 0.02 | .378 | 0.08 | 0.03 | .017 | —b | — | — |

| Sex (0 = female, 1 = male) | 0.06 | 0.05 | .710 | −0.04 | 0.06 | .976 | — | — | — |

| SES | 0.04 | 0.02 | .098 | −0.10 | 0.03 | .001 | — | — | — |

| Psychotic diagnosis | −0.15 | 0.06 | .029 | −0.05 | 0.07 | .467 | — | — | — |

| Race (0 = white, 1 = AA) | 0.13 | 0.05 | .033 | −0.23 | 0.06 | .001 | — | — | — |

| Time | 0.23 | 0.01 | <.001 | −0.08 | 0.01 | <.001 | 0.97 | 0.08 | <.001 |

| Time × Age | −0.02 | 0.01 | .085 | 0.01 | 0.01 | .085 | −0.09 | 0.05 | .085 |

| Time × Sex | 0.00 | 0.02 | .958 | 0.00 | 0.01 | .958 | 0.35 | 0.10 | .001 |

| Time × SES | 0.02 | 0.01 | .033 | −0.01 | 0.01 | .084 | 0.03 | 0.05 | .522 |

| Time × Psychotic diagnosis | −0.05 | 0.02 | .039 | 0.01 | 0.02 | .533 | 0.16 | 0.12 | .378 |

| Time × Race | −0.06 | 0.02 | .005 | 0.01 | 0.01 | .430 | −0.26 | 0.11 | .038 |

Notes: Continuous variables, with the exception of time, were placed on a z metric to ease interpretation of parameters. SES = socioeconomic status; AA = African American.

ap Values are adjusted for the analysis of multiple functional outcome measures using Hochberg's correction.

bEffects on baseline status for returning to work were not estimated because no participants had returned to work while in the hospital at baseline. Effects on the model intercept reflect effects on week 10 return to work status and are not shown to avoid misinterpretation.

Are Racial Disparities in Mental Health Outcomes Equal across Gender, SES, and Diagnosis?

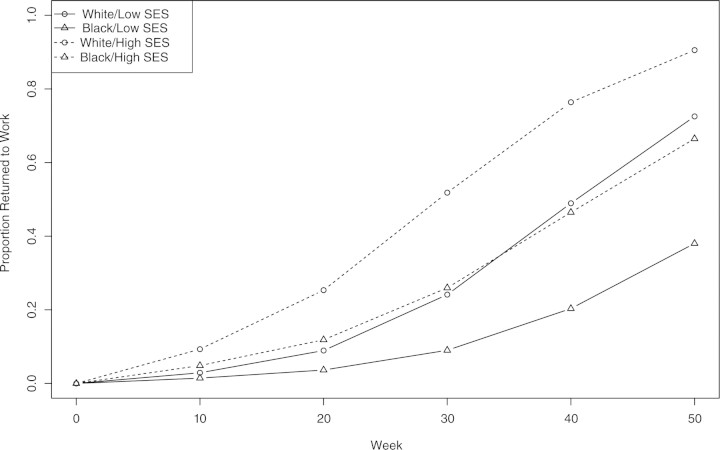

Having found that African Americans with severe mental illness tended to have less favorable improvement in select symptom and functional domains in the year following their psychiatric discharge compared with white Americans, we proceeded to conduct a series of moderator analyses to examine whether these disparities in mental health outcomes remained constant across gender, SES, and psychiatric diagnosis. As can be seen in Table 3, the only significant interaction with race at baseline was a disordinal interaction between race and gender on activation symptoms, with white men showing greater mania symptoms at baseline compared with African American men, and African American women showing greater mania symptoms at baseline compared with white women. No significant interactions between race and gender, SES, or psychiatric diagnosis were found for symptom trajectories previously showing disparities between races. However, a trend-level interaction between race and SES was found for probability of returning to work after hospital discharge (uncorrected p = .061), which did not survive multiple comparison corrections. As shown in Figure 2, the disparities between African Americans and white participants in post-discharge reemployment were exacerbated for individuals with low SES. No other significant interactions with race on functioning were observed. Overall, these findings point to racial disparities in symptom and functional improvement that are largely stable across gender, SES, and psychiatric diagnosis.

Table 3:

Moderator Analyses of the Effects of Gender, Socioeconomic Status (SES), and Diagnosis on Racial Differences in Mental Health Outcomes after Psychiatric Hospital Discharge among Individuals with Severe Mental Illness (N = 925)

| Symptoms |

Functioning |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Activation |

Anergia |

Global Assessment of Functioning |

Return to Work |

|||||||||

| Predictor | B | SE | pa | B | SE | p | B | SE | p | B | SE | p |

| Race × Sex | −0.32 | 0.12 | .027 | 0.13 | 0.11 | .931 | 0.09 | 0.11 | 1.000 | —b | — | — |

| Race × SES | −0.04 | 0.06 | 1.000 | 0.02 | 0.06 | 1.000 | −0.05 | 0.06 | 1.000 | — | — | — |

| Race × Psychotic diagnosis | 0.08 | 0.14 | 1.000 | −0.03 | 0.12 | 1.000 | −0.16 | 0.12 | .797 | — | — | — |

| Time × Race × Sex | 0.05 | 0.04 | .894 | −0.07 | 0.03 | .188 | −0.06 | 0.04 | .422 | −0.09 | 0.08 | 1.000 |

| Time × Race × SES | 0.03 | 0.02 | .489 | 0.01 | 0.02 | 1.000 | 0.02 | 0.02 | 1.000 | 0.09 | 0.05 | .242 |

| Time × Race × Psychotic diagnosis | −0.03 | 0.04 | 1.000 | −0.05 | 0.04 | .885 | 0.06 | 0.04 | .758 | −0.01 | 0.09 | 1.000 |

Notes: Continuous variables, with the exception of time, were placed on a z metric to ease interpretation of parameters. Main effects of race and control variables (age, sex, SES, and psychotic diagnosis) on initial status and change are not duplicated here to reduce visual clutter, and are presented in Tables 1 and 2. SES = socioeconomic status.

ap Values are adjusted for the analysis of multiple outcome measures using Hochberg's correction.

bInteractions with baseline status for returning to work were not estimated because no participants had returned to work while in the hospital at baseline. Interactions with the model intercept reflect interactions with week 10 return to work status and are not shown to avoid misinterpretation.

Figure 2:

Interactions between Race and Socioeconomic Status (SES) on Return to Work One Year after Hospital Discharge

DISCUSSION

Racial disparities in mental health services and outcomes have been widely described in non-institutionalized community samples. Previous studies have generally indicated that racial and ethnic minorities with mental health conditions have less access to mental health services, receive poorer quality services when they are available and, as a result, carry a greater burden from psychiatric conditions than their white counterparts (HHS, 2001). Few studies, however, have specifically examined differences in mental health outcomes among individuals with the most serious of mental disorders. A clearer understanding of the degree to which racial and ethnic minority individuals who suffer from a severe mental illness have less favorable mental health outcomes once they are discharged to the community is particularly important for mobilizing appropriate social work and behavioral health services for this population.

In this study, we investigated racial disparities in mental health symptom and psychosocial functioning domains by examining the outcomes of 925 African American and white individuals with severe mental illness who were followed and interviewed every 10 weeks over the course of one year subsequent to hospital discharge. Overall, the results revealed that, despite mixed evidence on service disparities in minority groups with severe mental illness, disparities in mental health outcomes between African American and white individuals do exist. In particular, African American participants demonstrated less improvement in symptoms, specifically activation/mania symptoms and negative symptoms than their white counterparts. Furthermore, after hospital discharge, significantly fewer African American participants were able to return to work, and their global assessment of functioning was less improved compared with white participants. These racial differences persisted even after adjusting for sociodemographic and diagnostic confounders and were largely stable across gender, SES, and psychiatric diagnosis. Together these findings point to the need for more effective community mental health services for minorities with a severe mental illness.

The results of this research are generally consistent with those studies of noninstitutionalized samples and individuals with less severe psychiatric disabilities. Such studies have also found that African Americans have less favorable mental health outcomes after treatment (Sue, Fujino, Hu, Takeuchi, & Zane, 1991; Williams et al., 2007), which may be due to differences in the quality of (Virnig et al., 2004) or access to services (Snowden, 2001). Although differences in specific mental health outcomes vary across studies, less improvement in psychiatric symptomatology has been a consistent theme among investigations of African Americans in noninstitutionalized samples (HHS, 2001). What is particularly striking about this research is that studies thus far have indicated that the black–white gap in service delivery may be smallest among individuals with severe mental illness (Alegría et al., 2002; Snowden & Thomas, 2000). Racial disparities in mental health outcomes are then to be expected among non-institutionalized samples where disparities in services are large. However, this investigation indicates that even if service disparities among African Americans with severe mental illness are not as striking as noninstitutionalized samples, such individuals still have poorer mental health outcomes after hospitalization.

It is also interesting to note that moderator analyses of racial disparities in functioning did suggest that the racial gap in the likelihood of returning to work post–hospital discharge was greater among individuals with lower SES. Although these findings did not meet conventional levels of statistical significance and did not survive multiple comparison corrections, they do support the notion that even among relatively less affluent individuals with severe mental illness, individuals with fewer resources are likely to have particularly poor work outcomes. Further, although significant disparities in improvement in a variety of symptom and functional domains were observed in this research, not all domains studied exhibited a black–white gap. Most notably, the positive symptom domains of thought disorder and suspiciousness, which are most effectively treated with antipsychotic medication, showed equal rates of improvement among African American and white participants. In contrast, those domains that showed the most marked differences in improvement between races included anergia and activation symptoms, global functioning, and reemployment. These domains may rely more heavily on psychosocial treatments for their effective management than positive psychotic symptoms. As such, improvement in access to and the quality of psychosocial treatments for minorities with severe mental illness might be one of the most critical factors for improvement of mental health outcomes among this population.

Although this investigation has important implications for social work research and practice with racial and ethnic minority groups with severe mental illness, our findings are tempered by a number of limitations. First, although we were able to robustly document the presence of mental health outcome disparities between African American and white individuals with severe mental illness, this research could not determine why these disparities exist. A variety of explanations can be offered for the findings of this research, with the most likely being racial differences in the receipt of and the quality of mental health services. Unfortunately, data on treatments received by the individuals in our sample were not available for many of the participants and no information was collected on the quality of services that participants received. Previous studies have indicated that African Americans with severe mental illness receive different types of care from the mental health system compared with other racial groups, including greater inpatient and emergency care (Rosenfield, 1984; Snowden et al., 2009), more frequent use of injectable medications (Shi et al., 2007), and less costly and perhaps less effective treatments (Kuno & Rothbard, 2002). Studies have also shown that African Americans are the least likely to receive a follow-up appointment after psychiatric hospitalization compared with white Americans (Virnig et al., 2004). All of these service disparities could contribute to poorer mental health outcomes among African Americans with severe mental illness. It will be particularly important for future research to examine more closely how differences in the quality, amount, and type of services African Americans with severe mental illness receive compared with other groups affect their psychiatric and functional recovery in the community.

The collection of service data in this population is not a trivial task because many individuals with severe mental illness do not have stable housing and their receipt of services becomes difficult to track, particularly if a significant length of time has passed since the last research contact. Follow-up studies attempting to document service disparities among people with severe mental illness could then profit from frequent data collection points. In terms of documenting quality of services, which is more difficult than mere quantity of service contacts, the schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team has devised a rigorous methodology for assessing the quality of services offered to individuals with schizophrenia, based on research evidence (Lehman et al., 1998a). This has been used to document the poor quality of care that people with schizophrenia receive in the community (Lehman et al., 1998b), and a similar initiative could be promising for assessing the quality of care African Americans with severe mental illness receive.

Another limitation of this research is that individuals in this study were restricted to those with available follow-up data, and such individuals were less disabled and less likely to have a history of violence at study baseline. The exclusion of individuals not available at follow-up may restrict the generalizability of these findings. Furthermore, a relatively restricted number of functional domains were assessed, and it is possible that racial disparities in functional outcomes exist beyond those of global assessment of functioning and employment. In addition, differences in improvement in global assessment of functioning scores may also reflect differential rates of symptom improvement, as Global Assessment of Functioning scale ratings are based on a composite view of a person's psychosocial functioning, which includes psychological, social, and occupational domains. Future studies are needed to more comprehensively assess the degree to which racial disparities exist within specific functional domains (for example, interpersonal functioning, family functioning). The use of the DSM–III–R may also have resulted in the diagnosis of some individuals that is not consistent with the current Diagnostic and Statistic Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition Text Revision (DSM–IV–TR) diagnostic system. However, specific individual psychiatric diagnoses were not the focus of this study, and our broad classification of people with and without a psychotic disorder would have likely remained the same in the current nosology system, as there were few changes to psychotic disorder criteria between the DSM–III–R and DSM–IV–TR. Finally, only sociodemographic and diagnostic moderators of mental health outcome disparities were examined in this research, and it will be important for future studies to examine other potential moderators of outcome disparities in severe mental illness, such as family structure, treatment availability, and community supports.

The primary strength of our study is that this is the first long-term longitudinal investigation that has examined racial disparities in diverse mental health outcomes while accounting for likely sociodemographic and diagnostic confounders in a large sample of people with severe mental illness. Currently, however, it is not clear whether these results can be generalized to other racial and ethnic minority populations. Disparities in mental health services have been observed in nonwhite Hispanics (Hough et al., 1987) and other minority samples (HHS, 2001). However, this investigation focused only on African American individuals with severe mental illness, and as such is not able to determine the degree to which disparities exist within and between other minority–majority groups, although initial findings from other groups suggest the likely possibility of outcome disparities beyond African American minorities (Ortega & Rosenheck, 2002). The systematic study of mental health outcomes in additional minority populations with severe mental illness is urgently needed.

In summary, this research found that despite few differences in baseline mental health outcomes on psychiatric hospitalization, African Americans with severe mental illness experienced significantly less favorable trajectories of improvement in a variety of critical symptom and functional outcome domains when followed for a year post–hospital discharge. These findings call attention to the existence of disparities in mental health outcomes between minority and majority groups of individuals with severe mental illness. Such results highlight the importance of future investigations seeking to identify service and discriminatory mechanisms that contribute to poorer mental health outcomes among minority populations with severe psychiatric disabilities and point to the need to improve psychosocial and social work interventions for this population to reduce the observed disparities in service outcomes.

REFERENCES

- Alegría M., Canino G., Ríos R., Vera M., Calderón J., Rusch D., Ortega A. N. Inequalities in use of specialty mental health services among Latinos, African Americans, and non-Latino whites. Psychiatric Services. 2002;53:1547–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.53.12.1547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barnes A. Race and hospital diagnoses of schizophrenia and mood disorders. Social Work. 2008;53:77–83. doi: 10.1093/sw/53.1.77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrio C., Yamada A. M., Hough R. L., Hawthorne W., Garcia P., Jeste D. V. Ethnic disparities in use of public mental health case management services among patients with schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services. 2003;54:1264–1270. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.54.9.1264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan R. W., Carpenter W. T. Schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders. In: Kaplan B. J., Sadock V. A., editors. Kaplan & Sadock's comprehensive textbook of psychiatry. 8th ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2005. pp. 1329–1550. vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Chinman M. J., Rosenheck R. A., Lam J. A. Client–case manager racial matching in a program for homeless persons with serious mental illness. Psychiatric Services. 2000;51:1265–1272. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.51.10.1265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Citrome L., Levine J., Allingham B. Utilization of depot neuroleptic medication in psychiatric inpatients. Psychopharmacology Bulletin. 1996;32:321–326. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dempster A. P., Laird N. M., Rubin D. B. Maximum likelihood from incomplete data using the EM algorithm. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society, Series B (Methodological) 1977;39:1–38. [Google Scholar]

- Endicott J., Spitzer R. L., Fleiss J. L., Cohen J. The Global Assessment Scale: A procedure for measuring overall severity of psychiatric disturbance. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1976;33:766–771. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770060086012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folsom D. P., Gilmer T., Barrio C., Moore D. J., Bucardo J., Lindamer L. A., et al. A longitudinal study of the use of mental health services by persons with serious mental illness: Do Spanish-speaking Latinos differ from English-speaking Latinos and Caucasians. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2007;164:1173–1180. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06071239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher C. A. New directions in race research. Social Forces. 2007;86:553–559. [Google Scholar]

- Gift T. E., Harder D. W., Ritzler B. A., Kokes R. F. Sex and race of patients admitted for their first psychiatric hospitalization: Correlates and prognostic power. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1985;142:1447–1449. doi: 10.1176/ajp.142.12.1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hochberg Y. A sharper Bonferroni procedure for multiple tests of significance. Biometrika. 1988;75:800–802. [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead A. B., Redlich F. C. Social class and mental illness: A community study. New York: Wiley; 1958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hough R. L., Landsverk J. A., Karno M., Burnam M. A., Timbers D. M., Escobar J. I., Regier D. A. Utilization of health and mental health services by Los Angeles Mexican Americans and non-Hispanic whites. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1987;44:702–709. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800200028005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hudson C. G. Socioeconomic status and mental illness: Tests of the social causation and selection hypotheses. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry. 2005;75:3–18. doi: 10.1037/0002-9432.75.1.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- J'anca A., Helzer J. DSM-III-R criteria checklist. DIS Newsletter. 1990;7:17. [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R. C., Mcgonagle K. A., Zhao S., Nelson C. B. Lifetime and 12-month prevalence of DSM–III–R psychiatric disorders in the United States: Results from the National Comorbidity Study. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1994;51:8–19. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1994.03950010008002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne A. M., Bauer M. S., Han X., Haas G. L., Elder P., Good C. B., et al. Racial differences in the treatment of veterans with bipolar disorder. Psychiatric Services. 2005;56:1549–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.56.12.1549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuno E., Rothbard A. B. Racial disparities in antipsychotic prescription patterns for patients with schizophrenia. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:567–572. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.4.567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman A. F., Steinwachs D. M., Dixon L. B., Goldman H. H., Osher F., Postrado L., et al. Translating research into practice: The schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) treatment recommendations. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1998;24:1–10. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lehman A. F., Steinwachs D. M., Dixon L. B., Postrado L., Scott J. E., Fahey M., et al. Patterns of usual care for schizophrenia: Initial results from the schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) client survey. Schizophrenia Bulletin. 1998;24:11–20. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.schbul.a033303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monahan J., Steadman H., Silver E., Appelbaum P., Robbins P., Mulvey E., et al. Rethinking risk assessment: The MacArthur Study of Mental Disorder and Violence. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Murray C.J.L., Lopez A. D. The global burden of disease. Boston: Harvard University Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Newhill C. E., Harris D. African American consumers' perceptions of racial disparities in mental health services. Social Work in Public Health. 2008;23:107–124. doi: 10.1080/19371910802151861. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega A. N., Rosenheck R. Hispanic client-case manager matching: Differences in outcomes and service use in a program for homeless persons with severe mental illness. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease. 2002;190:315–323. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200205000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Overall J. E., Gorham D. R. The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale. Psychological Reports. 1962;10:799–812. [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing (Version 2.5.0) [Computer software] Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Rank M. R. One nation, underprivileged: Why American poverty affects us all. New York: Oxford University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Raudenbush D.S.W., Bryk D.A.S. Hierarchical linear models: Applications and data analysis methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenfield S. Race differences in involuntary hospitalization: Psychiatric vs. labeling perspectives. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1984;25:14–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal S. P., Bola J. R., Watson M. A. Race, quality of care, and antipsychotic prescribing practices in psychiatric emergency services. Psychiatric Services. 1996;47:282–286. doi: 10.1176/ps.47.3.282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shafer A. Meta-analysis of the Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale factor structure. Psychological Assessment. 2005;17:324–335. doi: 10.1037/1040-3590.17.3.324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi L., Ascher-Svanum H., Zhu B., Faries D., Montgomery W., Marder S. R. Characteristics and use patterns of patients taking first-generation depot antipsychotics or oral antipsychotics for schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services. 2007;58:482–488. doi: 10.1176/ps.2007.58.4.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowden L. R. Barriers to effective mental health services for African Americans. Mental Health Services Research. 2001;3(4):181–187. doi: 10.1023/a:1013172913880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowden L. R., Cheung F. K. Use of inpatient mental health services by members of ethnic minority groups. American Psychologist. 1990;45:347–355. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.45.3.347. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowden L. R., Hastings J. F., Alvidrez J. Overrepresentation of black Americans in psychiatric inpatient care. Psychiatric Services. 2009;60:779–785. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.6.779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snowden L. R., Thomas K. Medicaid and African American outpatient mental health treatment. Mental Health Services Research. 2000;2:115–120. doi: 10.1023/a:1010161222515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steadman H. J., Mulvey E. P., Monahan J., Robbins P. C., Appelbaum P. S., Grisso T., et al. Violence by people discharged from acute psychiatric inpatient facilities and by others in the same neighborhoods. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1998;55:393–401. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.55.5.393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strakowski S. M., Shelton R. C., Kolbrener M. L. The effects of race and comorbidity on clinical diagnosis in patients with psychosis. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 1993;54:96–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturm R., Gresenz C., Sherbourne C., Minnium K., Klap R., Bhattacharya J., et al. The design of Healthcare for Communities: A study of health care delivery for alcohol, drug abuse, and mental health conditions. Inquiry. 1999;36:221–233. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue S., Fujino D. C., Hu L., Takeuchi D. T., Zane N.W.S. Community mental health services for ethnic minority groups: A test of the cultural responsiveness hypothesis. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 1991;59:533–540. doi: 10.1037//0022-006x.59.4.533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services [HHS] Rockville, MD: Author; 2001. Mental health: Culture, race, and ethnicity—A supplement to mental health: A report of the surgeon general. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Virnig B., Huang Z., Lurie N., Musgrave D., McBean A. M., Dowd B. Does Medicare managed care provide equal treatment for mental illness across races? Archives of General Psychiatry. 2004;61:201–205. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.2.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams D. R., Gonzalez H. M., Neighbors H., Nesse R., Abelson J. M., Sweetman J., Jackson J. S. Prevalence and distribution of major depressive disorder in African Americans, Caribbean blacks, and non-Hispanic whites: Results from the National Survey of American Life. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2007;64:305–315. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.3.305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson W. J. Toward a framework for understanding forces that contribute to or reinforce racial inequality. Race and Social Problems. 2009;1:3–11. [Google Scholar]