Abstract

It has been suggested that adult metabolic dysfunction may be more severe in individuals who become obese as children compared with those who become obese later in life. To determine whether adult metabolic function differs if diet-induced weight gain occurs during the peripubertal age vs. if excess weight gain occurs after puberty, male C57Bl/6J mice were fed a low-fat (LF; 10% kcal from fat) or high-fat (HF; 60% kcal from fat) diet starting during the peripubertal period (pHF; 4 wk of age) or as adults (aHF; 12 wk of age). Both pHF and aHF mice were hyperinsulinemic and hyperglycemic, and both showed impaired glucose tolerance and insulin resistance compared with their LF-fed controls. However, despite a longer time on diet, pHF mice were relatively more insulin sensitive than aHF mice, which was associated with higher lean mass and circulating IGF-I levels. In addition, HF feeding had an overall stimulatory effect on circulating corticosterone levels; however, this rise was associated only with elevated plasma ACTH in the aHF mice. Despite the belief that adult metabolic dysfunction may be more severe in individuals who become obese as children, data generated using a diet-induced obese mouse model suggest that adult metabolic dysfunction associated with peripubertal onset of obesity is not worse than that associated with adult-onset obesity.

Keywords: age at onset of obesity, childhood obesity, insulin-like growth factor type I

limited exercise and excess food consumption are fueling an obesity pandemic across all age groups. In the US, 35.5% of adults and 17% of children and adolescents are considered obese (7, 8, 30). Since obesity is known to increase the risk of developing cardiovascular disease and diabetes, both of which reduce the average life expectancy, considerable resources have been devoted to understanding, preventing, and reversing obesity. Of particular concern is the long-term consequences of obesity in children, since some retrospective studies indicate that obesity in children increases their risk of developing metabolic disease in adulthood (17, 19–21, 26, 28). This may be due to the fact that the cumulative time spent in the obese state dictates the severity of metabolic disease and/or that obesity prior to puberty alters developmental patterns (which may include changes in central signaling, structural growth, and sexual maturation), thereby altering the initiation/progression of metabolic disease in the adult. However, the view that childhood obesity leads to more severe adult metabolic dysfunction is not universally accepted. A recent retrospective review of the literature revealed that children on the lower end of the body mass index range are at a greater risk of developing obesity and its associated pathologies as adults (23). It is also becoming apparent that the developmental age (prenatal, neonatal, childhood, adolescence) at which excess nutrient intake occurs may dictate either a positive or negative metabolic phenotype in adulthood (19, 26, 32, 37, 40). Differentiating between these possibilities in the clinical setting is challenging, and controlled studies cannot be conducted due to ethics concerns. Therefore, researchers have utilized a number of animal models to better understand the metabolic consequences of obesity. A large number of studies examining the metabolic impact of diet (high-fat)-induced obesity (DIO) have been conducted in rodent models, but to our knowledge no studies have been conducted to determine specifically whether adult metabolic function differs if diet-induced weight gain occurs during the peripubertal age vs. whether excess weight gain occurs after puberty. Therefore, the current study compared weight gain, body composition, and glucose homeostasis as well as IGF-I and glucocorticoid levels, in male C57Bl6 mice fed either a low-fat (LF) or a high-fat (HF) diet starting during the peripubertal period (4 wk of age), with mice starting LF and HF diets as adults (12 wk of age).

METHODS

Animals.

Experimental procedures used to generate data in Figs. 1, A–C, 2, 3, and 4 were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) of the University of Cordoba, where these studies were performed. A second group of mice was generated at the Jesse Brown Veterans Affairs (VA) Medical Center in Chicago to determine the impact of prepubertal-onset vs. adult-onset obesity in body composition (see below; Fig. 1D); this specific experimental procedure was approved by the IACUC of the University of Illinois at Chicago and the Jesse Brown VA Medical Center. C57Bl/6J male mice were bred in-house and maintained under standard conditions of light (12:12-h light-dark cycle) and temperature (22–24°C), with free access to food (standard rodent chow)/tap water. At 4 (peripubertal) or 12 wk (adult) of age, a set of mice were fed a LF diet or HF diet [10 or 60% kcal, respectively, from fat (primarily animal fat); Research diets]. It should be noted that mice were randomly selected (1–2 pups·litter−1·diet−1·age−1) from litters ranging from two to nine pups/litter, where the average litter size within group was modestly higher in peripubertal groups compared with adult groups (pLF 6 ± 0.5 vs. aLF 4 ± 0.4; pHF 6 ± 0.5 vs. aHF 4 ± 0.3). Prior to euthanasia or glucose and insulin tolerance tests (see below for details), the mice were acclimated to laboratory personnel and handling to minimize stress. Mice starting the LF or HF diets at the beginning of the peripuberal period (pLF and pHF, respectively) were euthanized after 16 wk of diet [20 wk of age, the period of time in which we have reported previously that mice become hyperglucemic and hyperinsulinemic (24)], whereas mice starting diets as adults (aLF and aHF) were euthanized after 13 wk of diet [25 wk of age, the period of time in which mice are also hyperglucemic and hyperinsulinemic (seeresults)] by decapitation, without anesthesia, under fed conditions. It should be noted that in the present study we focused the comparisons mainly between controls (LF) and obese (HF) mice within group (diet starting as peripuberal or as adult) since the main goal of this study was to determine the impact of age at onset of obesity in metabolic function.

Fig. 1.

Effects of age at onset of diet-induced obesity (DIO) weight gain. A: growth curves of mice starting low-fat (LFD) or high-fat diets (HFD) at 4 (peripubertal; left) or 12 wk of age (adult; right). B: postmortem fat depot weight (sum of subcutaneous and urogenital fat depots). C: plasma leptin levels. D: fat mass and lean mass of peripubertal (left) or adult onset of LFD/HFD (right) from a separate set of unanesthetized mice, as assessed by by whole body NMR. *P < 0.05 and ***P < 0.001, significant impact of diets within age group. BW, body weight.

Fat depots and liver were weighed, and blood and tissues (hypothalamus, pituitary, liver, and adrenal glands) were immediately collected, snap-frozen in liquid-nitrogen, and stored at −80°C for further analysis as described below. As mentioned above, changes in body composition (lean and fat mass) over the course of the diet were assessed in unanesthetized mice by whole body nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR; MiniSpec LF50; Bruker Optics, Manning Park, Billerica, MA).

Glucose and insulin tolerance tests.

Glucose tolerance tests (GTT; 1 g/kg ip glucose, overnight-fasted condition) were performed in pLF and pHF groups at 17 wk of age (13 wk of diet) and in aLF and aHF groups at 22 wk of age (10 wk of diet) and between 0700 and 1000. Insulin tolerance tests [ITT; 1 U/kg ip insulin, fed condition; Actrapid (Novo-Nordisk, Bagsvaerd, Denmark)] were performed in pLF and pHF mice at 19 wk of age (15 wk of diet) and in aLF and aHF groups at 23 wk of age (11 wk of diet) between 0700 and 1000.

Circulating glucose and hormones.

Glucose levels were determined from fresh tail vein or trunk blood samples using the Glucocard glucometer (Arkray, Amstelveen, The Netherlands). The remaining trunk blood was immediately mixed with MiniProtease inhibitor (Roche, Barcelona, Spain), placed on ice, and centrifuged, and plasma was stored at −80°C until hormone analysis. Hormones were assessed using commercial ELISA kits for mouse insulin, leptin (Millipore, Madrid, Spain), adrenocotricotropin hormone (ACTH; Phoenix; Karlsruhe, Germany), corticosterone, and IGF-I (Immunodiagnostics Systems, Boldon, UK).

Quantitative real-time RT-PCR.

Total RNA was extracted from tissues, reverse transcribed, and amplified by quantitative real-time RT-PCR, as described previously (4, 5). Primer sequence, melting temperature, and length of PCR product are provided in Table 1. mRNA copy numbers of all transcripts were adjusted by cyclophilin A mRNA in hypothalamus, pituitary, and adrenal gland extracts or by a normalization factor (NF) calculated from the mRNA copy numbers of three separate housekeeping genes (hypoxanthine-ribosyltransferase, β-actin, and cyclophilin A) using the GeNorm 3.3 application in liver extracts, where NF or cyclophilin A mRNA levels did not vary significantly between experimental groups within tissue type (data not shown).

Table 1.

Specific set of primers for amplification of mouse transcripts used for quantitative real-time RT-PCR

| Template | Genbank Accession No. | Primer Sequence | Nucleotide Position | Product Length |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyclophilin A | NM_008907.1 | Sense: TGGTCTTTGGGAAGGTGAAAG | Sn 421 | 109 |

| Antisense: TGTCCACAGTCGGAAATGGT | As 529 | |||

| β-Actin | NM_007393.2 | Sense: CTGGGACGACATGGAGAAGA | Sn 313 | 205 |

| Antisense: ACCAGAGGCATACAGGGACA | As 517 | |||

| HPRT | NM_013556 | Sense: CAGTCAACGGGGGACATAAA | Sn 471 | 183 |

| Antisense: AGAGGTCCTTTTCACCAGCAA | As 653 | |||

| GHR | BC075720 | Sense: GATTTTACCCCCAGTCCCAGTTC | Sn 1125 | 198 |

| Antisense: GACCCTTCAGTCTTCTCATCCACA | As 1322 | |||

| IGF-I | NM_010512.3 | Sense: TCGTCTTCACACCTCTTCTACCT | Sn 31 | 202 |

| Antisense: ACTCATCCACAATGCCTGTCT | As 232 | |||

| IGFALS | NM_008340.3 | Sense: GCTCAGCGTCTTTTGCAGTT | Sn 204 | 107 |

| Antisense: AGGGGATGGAGGACAGGTT | As 310 | |||

| IGFBP-1 | NM_008341.3 | Sense: ATTAGCTGCAGCCCAACAGA | Sn 776 | 124 |

| Antisense: GAGTCCAGCTTCTCCATCCA | As 899 | |||

| IGFBP-2 | NM_008342.2 | Sense: GCGGGTACCTGTGAAAAGAGA | Sn 422 | 135 |

| Antisense: ACTGCTACCACCTCCCAACA | As 556 | |||

| IGFBP-3 | NM_008343.2 | Sense: GGCAGCCTAAGCACCTACCT | Sn 500 | 97 |

| Antisense: CAACCTGGCTTTCCACACTC | As 596 | |||

| CRF | NM_205769.1 | Sense: TCTGGATCTCACCTTCCACCT | Sn 630 | 95 |

| Antisense: CCATCAGTTTCCTGTTGCTGT | As 724 | |||

| POMC | DQ315472 | Sense: CCCTACAGGATGGAGCACTT | Sn 7 | 127 |

| Antisense: CGTTCTTGATGATGGCGTTT | As 133 | |||

| MCR2 | NM_008560.2 | Sense: CTGTTCCCTTTGATGCTGGT | Sn 797 | 207 |

| Antisense: AGGGTTATTTGGGCAGAAGG | As 1003 | |||

| 11βHSD1 | NM_001044751.1 | Sense: TTGCTCTGGATGGGTTCTTTT | Sn 661 | 206 |

| Antisense: CACCTCGCTTTTGCGTAGAG | As 865 |

HPRT, hypoxanthine-phosphoribosyltransferase; GHR, growth hormone receptor; IGFALS, IGF acid labile subunit; IGFBP, IGF-binding protein; CRF, corticotropin-releasing factor; POMC, proopiomelanocortin; MCR2, melanocortin receptor 2; 11βHSD1, 11β-hydroxysteriod dehydrogenase.

Statistical analysis.

Comparison of the response to GTT/ITT was assessed by two-way-ANOVA, followed by Bonferroni test for multiple comparisons. Because of the large sample number, tissue samples from mice starting diets during the peripubertal period (pLF and pHF) were processed separately from tissue samples of mice starting diets as adults (aLF and aHF). Therefore, direct comparisons of mRNA levels were made between diets within age and differences assessed by Student's t-tests. All data are expressed as means ± SE, where P < 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism 5 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA).

RESULTS

Effects of age at onset of DIO weight gain and body composition.

Mean body weights over the course of LF or HF feeding are shown in Fig. 1A. HF feeding in peripubertal mice augmented the rate of weight gain dramatically between 4 and 12 wk of age compared with LF-fed controls (pHF 1.52 g/wk vs. pLF 0.84 g/wk). Although the rate of growth slowed between 12–20 wk of age in both diet groups, it remained elevated in the pHF mice (pHF 0.77 g/wk vs. pLF 0.40 g/wk). NMR analysis of whole body composition revealed that the enhanced growth observed in the pHF mice was due to an increase in lean mass as well as an increase in fat mass (Fig. 1D).

When HF feeding was initiated in adult mice, the rate of weight gain between 12 and 20 wk of age exceeded that observed in age-matched pHF mice (aHF 1.23 g/wk vs. pHF 0.77 g/wk). In a separate set of mice, NMR analysis of whole body composition revealed that the enhanced growth observed in aHF mice was due to an increase fat mass, whereas lean mass did not differ from aLF mice (Fig. 1D).

Despite the fact that pHF were supplied excess calories for a longer period of time (16 wk), postmortem fat depot weights did not differ from those of aHF mice (Fig. 1B), which was reflected in similar levels of circulating leptin (Fig. 1C). Mean body weights, fat depot weights, and circulating leptin levels of aLF mice were modestly but significantly greater than pLF mice, which is likely due to the fact that aLF mice were maintained on a standard chow diet (17% kcal from fat) until the LF diet was started (10% kcal from fat) at 12 wk of age.

Effects of age at onset of DIO on glucose homeostasis.

Age at initiation of LF and HF feeding did not alter fed insulin or glucose levels measured in trunk blood samples, where both pHF and aHF mice were hyperinsulinemic and hyperglycemic compared with their LF-fed controls (Fig. 2, A and B). Consistent with these findings, pHF and aHF mice displayed impaired glucose tolerance and insulin resistance (Fig. 2, C–G) compared with their LF-fed controls. Age at onset of diet did not dramatically alter the area under the curve (AUC) for GTTs or ITTs when calculated using 0–120 min of sampling (Fig. 2, E and F, respectively). However, since early changes in endogenous glucose levels during ITTs are attributed to muscle uptake, whereas later changes in glucose levels are due to compensatory increases in hepatic gluconeogenesis (12), ITT AUCs were also calculated using 0- to 60-min samples (Fig. 2G). Interestingly, this showed that pHF mice, despite a longer time on diet, remained relatively more insulin sensitive than aHF mice. Therefore, it would be interesting to analyze insulin signaling in peripheral tissues in future studies; however, at this moment and with the available animals, we were unable to perform this experiment.

Fig. 2.

Effects of age at onset of DIO glucose homeostasis. A and B: plasma insulin (A) and plasma glucose levels (B) in mice with peripubertal- and adult-onset obesity after 16 or 13 wk of diet, respectively. C: glucose tolerance test (GTT) performed in peripubertal-onset obese mice at 17 wk of age = 13 wk of diet (left), and adult-onset obese mice at 22 wk of age = 10 wk of diet (right). D: insulin tolerance tests (ITT) performed in peripubertal-onset obese mice at 19 wk of age = 15 wk of diet (left), and adult-onset obese mice at 23 wk of age = 11 wk of diet (right). E: GTT area under the curve (AUC). F and G: ITT AUC. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, significant impact of diets within age group. aStatistical difference in glucose levels at t = 0 of GTT pLF (peripubertal groups of mice on LFD) and pHF mice (peripubertal groups of mice on HFD); P < 0.05.

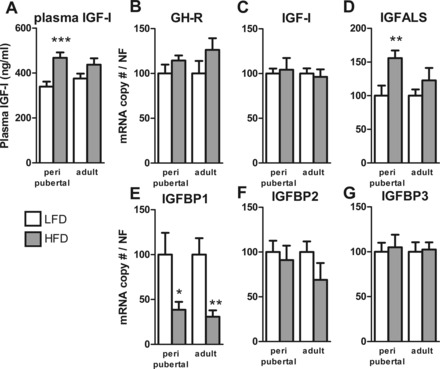

Effects of age at onset of DIO on the IGF-I system.

It has been hypothesized that hyperinsulinemia decreases concentrations of insulin-like growth factor binding protein (IGFBP)-1 and IGFBP-2, leading to increased availability of IGF-I (1, 35); however, a clear elevation in total or free IGF-I in obesity is controversial (1, 10, 11). In the current study, total circulating IGF-I levels were elevated in pHF mice but not in aHF mice (Fig. 3A) relative to their LF-fed controls. We were not able to measure free IGF-I in this study since, to the best of our knowledge, no commercial assay is available to measure free IGF-I in mice. However, given the fact that the liver is responsible for producing the majority of IGF-I found in the circulation and that GH is critical in maintaining optimum production of hepatic IGF-I (22), we assessed end points important in hepatic IGF-I production and transport/stability. Hepatic expression of growth hormone receptor and IGF-I were not altered by diet or age at initiation (Fig. 3, B and C). However, hepatic expression of IGF acid labile subunit (IGFALS) of pHF but not aHF mice was elevated relative to LF-fed controls (Fig. 3D). In addition, hepatic expression of IGFBP-1 was reduced in both pHF and aHF relative to their LF-fed controls, whereas hepatic expression of IGFBP-2 or IGFBP-3 was not altered (Fig. 3, F and G).

Fig. 3.

Effects of age at onset of DIO on the IGF-I system. A: plasma IGF-I levels in mice with peripubertal- and adult-onset obese mice after 16 or 13 wk of HFD, respectively, and their LFD controls. Relative hepatic mRNA levels of IGF-I (B), growth hormone receptor (GHR; C), IGF acid labile subunit (IGFALS; D), IGF-binding protein-1 (IGFBP-1; E), IGFBP-2 (F), and IGFBP-3 (G) in mice with peripubertal- and adult-onset obesity after 16 or 13 wk of HFD and their LFD controls. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, significant impact of diets within age group.

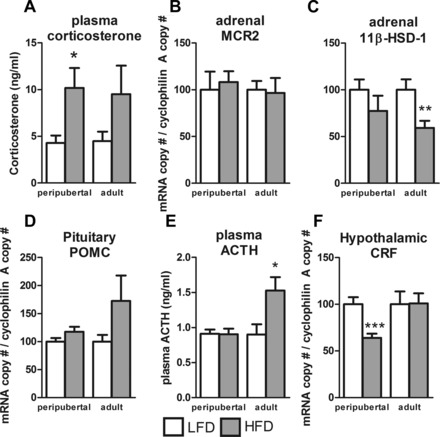

Effects of age at onset of DIO on the adrenal axis.

Dysregulation of adrenal axis function is thought to play a major role in the development of obesity and insulin resistance (36). Therefore, we examined the impact of age at onset of obesity on the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis, and the results are shown in Fig. 4. There was an overall stimulatory effect of HF feeding (2-way ANOVA, P = 0.0182) on corticosterone levels, which reached significance only in pHF mice (P = 0.1 for aHF vs. aLF) (Fig. 4A). Although expression of ACTH receptor (MCR2) was not altered in the adrenal gland (Fig. 4B), adrenal expression of 11β-hydroxysteriod dehydrogenase, an enzyme involved directly in the production of corticosterone, was suppressed in aHF mice but not pHF mice relative to LF-fed controls (Fig. 4C). In aHF mice but not pHF mice, pituitary proopiomelanocortin mRNA levels tended to be elevated (P = 0.09; Fig. 4D), which was associated with a significant elevation in plasma ACTH levels (Fig. 4E). The ability of pHF but not aHF mice to maintain normal ACTH secretion may be due to the fact that hypothalamic CRF input to the pituitary may be reduced, as indicated by a significant reduction in hypothalamic expression of CRF (Fig. 4F).

Fig. 4.

Effects of age at onset of DIO on the adrenal axis. Plasma levels of corticosterone (A), mRNA levels of adrenal melanocortin receptor 2 (MCR2; B), and adrenal 11β-hydroxysteriod dehydrogenase (11βHSD1; C). mRNA levels of pituitary proopiomelanocortin (POMC; D), plasma levels of adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH; E), and mRNA levels of hypothalamic corticotropin releasing factor (CRF; F). All samples were collected from mice with peripubertal- and adult-onset obesity after 16 or 13 wk of HFD, respectively, and their LFD controls. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, and ***P < 0.001, significant impact of diets within age group.

DISCUSSION

The prevalence of obesity in the childhood/adolescent population is alarmingly high (30), raising questions about the impact of childhood/adolescent excess weight gain on adult metabolic function. Although some studies suggest that metabolic dysfunction is more severe in adults who became obese during adolescence (17, 28), this assumption has been challenged recently (23). Given the difficulties in designing controlled experiments in humans to accurately address this issue, the current study used a common model of DIO, where male C57Bl6/J mice are fed a diet rich in animal fat (60% kcal from fat) starting at 4 wk of age (representing the start of the peripubertal period). These mice rapidly gain fat mass and by 16 wk of HF feeding are obese, hyperlipidemic, insulin resistant, and glucose intolerant relative to mice fed a LF diet (10% kcal from fat) (27). We hypothesized that adult metabolic function of mice starting the HF diet during the peripubertal period (pHF) would be more impaired than that of mice that began HF-feeding as adults (aHF). However, the current results indicate that this is not the case, because fat mass and glucose homeostasis were similar between pHF and aHF mice, although pHF mice consumed the HF diet for a longer period of time.

Although we cannot rule out the possibility that differences in fat mass and glucose homeostasis may arise if these mice are followed for a longer period of time, the current results do support the notion that peripubertal onset of obesity does not lead to a more severe metabolic phenotype in the young adult relative to the impact of weight gain after puberty. One factor that may likely contribute to the relative maintenance of metabolic function in pHF mice is the increase in lean mass, which was not observed in aHF mice. These findings are consistent with previous reports, which used NMR to examine body composition in HF-fed mice and reported a pronounced increase in lean mass in pHF compared with LF- or chow-fed controls (34), whereas studies that began HF feeding in adult mice reported little or no change in lean mass (18). Given the primary role of muscle in whole body energy utilization (12), an increase in total lean mass might serve a protective role in maintaining glucose homeostasis to counterbalance the negative impact of fat accumulation. In humans (9, 13, 16) as well as mice (15), childhood/adolescence onset of obesity also accelerates skeletal growth and maturation.

Elevated IGF-I levels may also contribute to the increase in lean mass in pHF mice. Elevated adult IGF-I levels have also been reported by others using the same pHF mouse model (15, 41) as well as in prepubertal (1 yr of age) diet-induced obese primates (39). In addition, elevated IGF-I levels have been observed in obese children and adolescents (25, 31); however, some but not all studies have reported elevated IGF-I in obese adults (1, 10, 38). The variability in the adult data could be due in part to differences in the age at obesity onset in the study population, which was not considered in these studies. Variability may also be due to differences in absolute fat mass, where adipose tissue can produce IGF-I and may contribute to the circulating pool (29). Although there are discrepancies in the literature with respect to the impact of obesity on total IGF-I, it has been proposed that DIO leads to an increase in the level of bioavailable IGF-I by changing circulating levels of IGF-I binding proteins, which are known to positively or negatively impact the biological function of IGF-I (1, 10, 11). Although we did not assess free IGF-I in the current study, indirect evidence suggest that levels may be elevated, particularly in pHF mice. First, the hepatic expression of IGFBP-1 was reduced in both pHF and aHF mice, which is consistent with previous reports showing a decrease in circulating IGFBP-1 in obese humans and mice (1, 10, 11), where IGFBP-1 is thought to retain IGF-I in the circulation, thereby reducing its biological effect. In addition, hepatic expression of IGFBP-1 and expression of IGFALS were increased in pHF but not in aHF mice. The majority of circulating IGF-I is bound to IGFALS and IGFBP-3, and this ternary complex serves to increase the half-life of IGF-I (14). The importance of IGFALS in maintaining bioactive IGF-I is supported by the observation that inactivating mutations in IGFALS are associated with reduced total IGF-I levels, short stature, and insulin resistance (6). It should be noted that the metabolic dysfunction of IGFALS mutant subjects may be due not only to impairment of structural growth but also directly to the loss of IGF-I, since IGF-I has been reported to directly enhance insulin signaling (3, 33). Therefore, we might speculate that DIO during the adolescent growth spurt enhances both total and bioavailable IGF-I, where IGF-I in conjunction with insulin increases lean mass. IGF-I levels may remain high in obese adults, who initially gained excess weight as children, and this could help to counterbalance the expected obesity-related morbidities.

Dysregulation of glucocorticoid production may exacerbate the onset of obesity and its related morbidities in adulthood (36). In the current study, high-fat feeding did indeed elevate corticosterone levels, which has been reported in some, but not all, DIO mouse studies (2). These differences could be attributed to differences in diet composition, duration of diet, and background strain as well as time and method of sampling. Despite similar elevations in corticosterone levels in current study, age at onset of HF feeding did have differential effects on expression of genes within the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis associated with glucocorticoid production, suggesting that there may be differences in the negative feedback regulation and/or that other factors not measured account for these differences. Understanding the mechanisms behind these differences will require dynamic sampling.

In contrast to the commonly accepted view that childhood-onset obesity exacerbates metabolic dysfunction in the adult (17, 19–21, 26, 28), the current results do not support this hypothesis, at least in the case of weight gain occurring during the peripubertal period in C57Bl6/J mice fed a diet rich in animal fat. In fact, the inability of aHF mice to respond to HF feeding by increasing lean mass and IGF-I levels, coupled with alterations in adrenal axis function, may set the stage for a more rapid decline in metabolic function compared with pHF mice. It should be noted that in the current study we tested the impact of DIO only during the peripubertal period, where studies in humans and mice have indicated that prenatal/neonatal overnutrition may have opposite effects (17, 19, 26–28, 32). Although additional studies will be required to tease apart these differences and unveil their molecular mechanisms, these initial observations demonstrate clearly that the age at onset of obesity should be considered when designing studies to examine metabolic function in different physiological/genomic states since it may produce important and specific changes in body composition, adrenal axis function, and insulin sensitivity.

GRANTS

This work has been funded by the following grants: Fundacion Alfonso Martin Escudero (to J. Cordoba-Chacon), Fundacion Caja Madrid (to M. D. Gahete), a Department of Veterans Affairs, Veterans Health Administration, Office of Research and Development Merit Award (Veterans Affairs Merit Grant no. BX-11-014), National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases Grant R01-DK-088133 (to R. D. Kineman), and BFU2008-01136/BFI, BFU2010-19300, CIBERobn, CTS-5051, and RYC-2007-00186 (to A. I. Pozo-Salas, A. Moreno-Herrera, J. P. Castaño, and R. M. Luque).

DISCLOSURES

The authors have no conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, to disclose.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

J.C.-C., J.P.C., R.D.K., and R.M.L. did the conception and design of the research; J.C.-C., M.D.G., A.I.P.-S., A.M.-H., R.D.K., and R.M.L. performed the experiments; J.C.-C., M.D.G., R.D.K., and R.M.L. analyzed the data; J.C.-C., M.D.G., R.D.K., and R.M.L. interpreted the results of the experiments; J.C.-C. and R.M.L. prepared the figures; J.C.-C., R.D.K., and R.M.L. drafted the manuscript; J.C.-C., M.D.G., J.P.C., R.D.K., and R.M.L. edited and revised the manuscript; J.C.-C. and R.M.L. approved the final version of manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Arafat AM, Weickert MO, Frystyk J, Spranger J, Schofl C, Mohlig M, Pfeiffer AF. The role of insulin-like growth factor (IGF) binding protein-2 in the insulin-mediated decrease in IGF-I bioactivity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94: 5093–5101, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Auvinen HE, Romijn JA, Biermasz NR, Havekes LM, Smit JW, Rensen PC, Pereira AM. Effects of high fat diet on the Basal activity of the hypothalamus-pituitary-adrenal axis in mice: a systematic review. Horm Metab Res 43: 899–906, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Clemmons DR. Role of insulin-like growth factor in maintaining normal glucose homeostasis. Horm Res 62, Suppl 1: 77–82, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Córdoba-Chacón J, Gahete MD, Castaño JP, Kineman RD, Luque RM. Somatostatin and its receptors contribute in a tissue-specific manner to the sex-dependent metabolic (fed/fasting) control of growth hormone axis in mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 300: E46–E54, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Córdoba-Chacón J, Gahete MD, Pozo-Salas AI, Martínez-Fuentes AJ, de Lecea L, Gracia-Navarro F, Kineman RD, Castaño JP, Luque RM. Cortistatin is not a somatostatin analogue but stimulates prolactin release and inhibits GH and ACTH in a gender-dependent fashion: potential role of ghrelin. Endocrinology 152: 4800–4812, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Domené HM, Scaglia PA, Jasper HG. Deficiency of the insulin-like growth factor-binding protein acid-labile subunit (ALS) of the circulating ternary complex in children with short stature. Pediatr Endocrinol Rev 7: 339–346, 2010 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Finucane MM, Stevens GA, Cowan MJ, Danaei G, Lin JK, Paciorek CJ, Singh GM, Gutierrez HR, Lu Y, Bahalim AN, Farzadfar F, Riley LM, Ezzati M; Global Burden of Metabolic Risk Factors of Chronic Diseases Collaborating Group (Body Mass Index). National, regional, and global trends in body-mass index since 1980: systematic analysis of health examination surveys and epidemiological studies with 960 country-years and 9.1 million participants. Lancet 377: 557–567, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Ogden CL. Prevalence of obesity and trends in the distribution of body mass index among US adults, 1999–2010. JAMA 307: 491–497, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Freedman DS, Khan LK, Serdula MK, Dietz WH, Srinivasan SR, Berenson GS. Inter-relationships among childhood BMI, childhood height, and adult obesity: the Bogalusa Heart Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 28: 10–16, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Frystyk J, Brick DJ, Gerweck AV, Utz AL, Miller KK. Bioactive insulin-like growth factor-I in obesity. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 94: 3093–3097, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gahete MD, Córdoba-Chacón J, Anadumaka CV, Lin Q, Brüning JC, Kahn CR, Luque RM, Kineman RD. Elevated GH/IGF-I, due to somatotrope-specific loss of both IGF-I and insulin receptors, alters glucose homeostasis and insulin sensitivity in a diet-dependent manner. Endocrinology 152: 4825–4837, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goren HJ, Kulkarni RN, Kahn CR. Glucose homeostasis and tissue transcript content of insulin signaling intermediates in four inbred strains of mice: C57BL/6, C57BLKS/6, DBA/2, and 129X1. Endocrinology 145: 3307–3323, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He Q, Karlberg J. Bmi in childhood and its association with height gain, timing of puberty, and final height. Pediatr Res 49: 244–251, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Heath KE, Argente J, Barrios V, Pozo J, Díaz-González F, Martos-Moreno GA, Caimari M, Gracia R, Campos-Barros A. Primary acid-labile subunit deficiency due to recessive IGFALS mutations results in postnatal growth deficit associated with low circulating insulin growth factor (IGF)-I, IGF binding protein-3 levels, and hyperinsulinemia. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 93: 1616–1624, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ionova-Martin SS, Wade JM, Tang S, Shahnazari M, Ager JW, 3rd, Lane NE, Yao W, Alliston T, Vaisse C, Ritchie RO. Changes in cortical bone response to high-fat diet from adolescence to adulthood in mice. Osteoporos Int 22: 2283–2293, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Johnson W, Stovitz SD, Choh AC, Czerwinski SA, Towne B, Demerath EW. Patterns of linear growth and skeletal maturation from birth to 18 years of age in overweight young adults. Int J Obes (Lond) 36: 535–541, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Juonala M, Magnussen CG, Berenson GS, Venn A, Burns TL, Sabin MA, Srinivasan SR, Daniels SR, Davis PH, Chen W, Sun C, Cheung M, Viikari JS, Dwyer T, Raitakari OT. Childhood adiposity, adult adiposity, and cardiovascular risk factors. N Engl J Med 365: 1876–1885, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kobayashi-Hattori K, Amuzie CJ, Flannery BM, Pestka JJ. Body composition and hormonal effects following exposure to mycotoxin deoxynivalenol in the high-fat diet-induced obese mouse. Mol Nutr Food Res 55: 1070–1078, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koletzko B, von Kries R, Monasterolo RC, Subias JE, Scaglioni S, Giovannini M, Beyer J, Demmelmair H, Anton B, Gruszfeld D, Dobrzanska A, Sengier A, Langhendries JP, Cachera MF, Grote V. Infant feeding and later obesity risk. Adv Exp Med Biol 646: 15–29, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lauer RM, Clarke WR. Childhood risk factors for high adult blood pressure: the Muscatine Study. Pediatrics 84: 633–641, 1989 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li L, Law C, Power C. Body mass index throughout the life-course and blood pressure in mid-adult life: a birth cohort study. J Hypertens 25: 1215–1223, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu JL, Yakar S, LeRoith D. Mice deficient in liver production of insulin-like growth factor I display sexual dimorphism in growth hormone-stimulated postnatal growth. Endocrinology 141: 4436–4441, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lloyd LJ, Langley-Evans SC, McMullen S. Childhood obesity and risk of the adult metabolic syndrome: a systematic review. Int J Obes (Lond) 36: 1–11, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luque RM, Kineman RD. Impact of obesity on the growth hormone axis: evidence for a direct inhibitory effect of hyperinsulinemia on pituitary function. Endocrinology 147: 2754–2763, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Madsen AL, Larnkjær A, Mølgaard C, Michaelsen KF. IGF-I and IGFBP-3 in healthy 9 month old infants from the SKOT cohort: breastfeeding, diet, and later obesity. Growth Horm IGF Res 21: 199–204, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McMillen IC, Rattanatray L, Duffield JA, Morrison JL, MacLaughlin SM, Gentili S, Muhlhausler BS. The early origins of later obesity: pathways and mechanisms. Adv Exp Med Biol 646: 71–81, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Muhlhausler BS. Nutritional models of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Methods Mol Biol 560: 19–36, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Must A, Jacques PF, Dallal GE, Bajema CJ, Dietz WH. Long-term morbidity and mortality of overweight adolescents. A follow-up of the Harvard Growth Study of 1922 to 1935. N Engl J Med 327: 1350–1355, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Nam SY, Marcus C. Growth hormone and adipocyte function in obesity. Horm Res 53, Suppl 1: 87–97, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ogden CL, Carroll MD, Kit BK, Flegal KM. Prevalence of obesity and trends in body mass index among US children and adolescents, 1999–2010. JAMA 307: 483–490, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ong KK, Langkamp M, Ranke MB, Whitehead K, Hughes IA, Acerini CL, Dunger DB. Insulin-like growth factor I concentrations in infancy predict differential gains in body length and adiposity: the Cambridge Baby Growth Study. Am J Clin Nutr 90: 156–161, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Patel MS, Srinivasan M. Metabolic programming in the immediate postnatal life. Ann Nutr Metab 58, Suppl 2: 18–28, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rao MN, Mulligan K, Tai V, Wen MJ, Dyachenko A, Weinberg M, Li X, Lang T, Grunfeld C, Schwarz JM, Schambelan M. Effects of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-I/IGF-binding protein-3 treatment on glucose metabolism and fat distribution in human immunodeficiency virus-infected patients with abdominal obesity and insulin resistance. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 95: 4361–4366, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ravussin Y, Gutman R, Diano S, Shanabrough M, Borok E, Sarman B, Lehmann A, LeDuc CA, Rosenbaum M, Horvath TL, Leibel RL. Effects of chronic weight perturbation on energy homeostasis and brain structure in mice. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 300: R1352–R1362, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Renehan AG, Frystyk J, Flyvbjerg A. Obesity and cancer risk: the role of the insulin-IGF axis. Trends Endocrinol Metab 17: 328–336, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roberge C, Carpentier AC, Langlois MF, Baillargeon JP, Ardilouze JL, Maheux P, Gallo-Payet N. Adrenocortical dysregulation as a major player in insulin resistance and onset of obesity. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 293: E1465–E1478, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sachdev HS, Fall CH, Osmond C, Lakshmy R, Dey Biswas SK, Leary SD, Reddy KS, Barker DJ, Bhargava SK. Anthropometric indicators of body composition in young adults: relation to size at birth and serial measurements of body mass index in childhood in the New Delhi birth cohort. Am J Clin Nutr 82: 456–466, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Scacchi M, Pincelli AI, Cavagnini F. Growth hormone in obesity. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord 23: 260–271, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Terasawa E, Kurian JR, Keen KL, Shiel NA, Colman RJ, Capuano SV. Body weight impact on puberty: effects of high-calorie diet on puberty onset in female rhesus monkeys. Endocrinology 153: 1696–1705, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wells JC, Chomtho S, Fewtrell MS. Programming of body composition by early growth and nutrition. Proc Nutr Soc 66: 423–434, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wu S, Aguilar AL, Ostrow V, De Luca F. Insulin resistance secondary to a high-fat diet stimulates longitudinal bone growth and growth plate chondrogenesis in mice. Endocrinology 152: 468–475, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]