Abstract

Advances in understanding the effects of early education have benefited public policy and developmental science. Although preschool has demonstrated positive effects on life-course outcomes, limitations in knowledge on program scale, subgroup differences, and dosage levels have hindered progress. We report the effects of the Child-Parent Center Education Program on indicators of well-being up to 25 years later for over 1,400 participants. This established, publicly-funded intervention begins in preschool and provides up to 6 years of service in inner-city Chicago schools. Relative to the comparison group receiving the usual services, program participation was independently linked to higher educational attainment, socioeconomic status (SES) including income, health insurance coverage as well as lower rates of justice-system involvement and substance abuse. Evidence of enduring effects was strongest for preschool, especially for males and children of high school dropouts. The positive influence of 4 or more years of service was limited primarily to education and SES. Dosage within program components was mostly unrelated to outcomes. Findings demonstrate support for the enduring effects of sustained school-based early education to the end of the third decade of life.

The effects of educational enrichment in the early years of life are a central focus of developmental science and are increasingly used to prioritize social programs and policies. In the past two decades, evidence has grown that preschool or “prekindergarten” programs enhance well-being in many domains, and can promote economic benefits to society (1–3). Although the most enduring effects on school success and crime prevention are found among economically disadvantaged children (4), preschool programs can promote well-being across the entire socioeconomic spectrum (5, 6).

The magnitude, breadth, and duration of impacts for preschool have been found to be more consistent and stronger than many prevention strategies (7). This pattern is likely due to the greater dosage, intensity, and scope of services. Preschools typically provide 500 hours per year. These enrichment experiences appear to initiate a pattern of cumulative advantages (7–9) that can translate to enduring life-course effects (10). Recent evidence on Head Start (11), however, suggests that enduring effects are not inevitable, and may depend on later social contexts (12).

Although evidence is strong that programs of relatively high quality can promote well-being, four major weaknesses reduce the strength and generalizability of evidence (13). The most widely documented limitation is that evidence on long-term effects is primarily from small-sample efficacy trials rather than effectiveness trials or studies of large-scale sustained programs (2, 4). Studies of sustained and routinely implemented programs are essential to translational research yet long-term evidence is meager (1, 7) and none have continued past age 25, which is most predictive of later development (14).

Three other less recognized limitations also have hindered progress. One is inadequate attention to program dosage, a prominent and modifiable characteristic. Although some studies show that the length of participation is positively associated with short-term outcomes (7, 15), longer-term effects have been rarely investigated as have the added or synergistic benefits of later intervention. The second limitation is that variations in effects by child, family, and social context are under-investigated. Their identification provides valuable information for tailoring or strengthening services. Differences by gender vary by study and outcome, and long-term effects on high-risk samples warrant greater investigation. Finally, attrition is rarely taken into account in estimating effects. Studies frequently lose up to 50% of their original samples in follow-up (16, 17). The power and precision of subgroup effects can be especially compromised. Bias reduction methods to account for attrition and other selection processes have become more integrated in estimation (18).

To assess the effects of a large-scale sustained early education in public schools, the Chicago Longitudinal Study (CLS) (19) has prospectively documented the life-course development of 1,539 families (93% African American), the majority of whom participated in the Child-Parent Center (CPC) Education Program. CPC is the second oldest (after Head Start) federally funded preschool, and has been implemented in the Chicago Public Schools since 1967 (20). In addition to providing comprehensive services to economically disadvantaged families, the program has preschool and school-age components that enable assessments of the timing and length of participation.

In this study, we investigate links between CPC participation and well-being by age 28. While previous studies of publicly-funded programs (21) including CPC (22) have showed positive evidence, due to the age of assessment in early adulthood, a full range of economic, health, and family outcomes has not been assessed. Moreover, unlike previously, we examine differential effects by timing and length of intervention as well as child and family attributes. We also take into account through propensity score analysis the potential biasing effects of attrition and selection bias. Our major questions are: (1) Is CPC participation beginning in preschool and continuing into school-age associated with multiple domains of well-being? (2) Do estimated effects vary by child and family characteristics as well as dosage levels? (3) Are effects consistent across models for reducing bias in estimates?

Born in 1979–1980, the CLS sample is the entire cohort of 989 children who completed preschool and kindergarten (half- or full-day) in all 20 CPCs and 550 low-income children who did not attend the program in preschool but participated in a full-day kindergarten intervention in five randomly selected schools. 15% attended Head Start with most others in home care. That the comparison group participated in an enrichment program minimizes bias in group selection. First- to third-grade program services are offered to all students. Table 1 shows the patterns of participation and for inclusion in the follow-up (13).

Table 1.

Patterns of participation and sample recovery of Child-Parent Center (CPC) Education Program and comparison groups in the Chicago Longitudinal Study

| Study category | Total Sample |

CPC Intervention Group |

Comparison Group |

|---|---|---|---|

| Original sample | 1539 | 989 | 550 |

| Program participation | |||

| No. in center-based preschool (Head Start) | 1073 | 989 | (84) |

| Full-day kindergarten, % | 74.2 | 59.9 | 100 |

| No. (%) with CPC school-age participation | 850 (55) | 684 (69) | 166 (30) |

| No.(%) with CPC extended intervention (4–6 y) | 553 (36) | 553 (56) | 0 (0) |

| No. lost (%) due to mobility, mortality, or other | 171 (11) | 104 (11) | 67 (12) |

| Sample recovery and characteristics by age 28 | |||

| No. (%) with educational attainment/employment | 1386 (90) | 900 (91) | 486 (88) |

| No. (Min, Max) for family, health, and justice outcomes | 1304,1473 | 850,950 | 454,523 |

| % sample recovery | 85,96 | 86,96 | 83,95 |

| Average age on August 31, 2008 | 28.29 | 28.27 | 28.32 |

| No. of covariates equivalent with compar. group (of 20) | -- | 18 | -- |

Cases for program participation cover the 6-year period (1983–1989) that defines enrollment in the CPC intervention. 176 cases in the preschool comparison group were eligible to receive limited services in the CPC kindergarten but enrolled in different classrooms. Some cases in the comparison group participated in the school-age program because it was open to any child enrolled in elementary school from first to third grade. Cases were lost during post-program years primarily because they moved from Chicago and could not be located, were deceased, or did not have sufficient identifying information to track.

In this alternative-intervention, quasi-experimental design, groups matched on age, eligibility for intervention, and family poverty. In support of the interpretability of estimates, group comparisons at the beginning of the study and at follow-up show similarity on preprogram characteristics (Table 1 and table S). Sample characteristics have been consistent over time.

Located in or close to elementary schools, the CPC program provides educational and family-support services between the ages of 3 and 9. The key goal stated by founder Lorraine Sullivan is that the centers “are designed to reach the child and parent early, develop language skills and self-confidence, and to demonstrate that these children, if given a chance, can meet successfully all the demands of today’s technological, urban society” (23). The program emphasizes basic skills in language arts and math through relatively structured but diverse learning experiences that include whole-class instruction, small-group and individualized activities, and frequent field trips. All teachers are certified and have bachelor’s degrees. Classes are small and are staffed by aides. In addition to the head teacher in each site, the parent resource teacher and outreach representative direct multi-faceted and intensive services in the parent resource room. The scope of services helped ensure high participation. Heavy outreach by staff also led to participation by families most in need (13).

As shown in Table 1, 90.1% of the original sample had follow-up data on educational attainment or socioeconomic status (mean age 28.3 years). Recovery rates for the groups were nearly identical. They ranged from 82% to 94% for other outcomes. Well-being was defined in five domains: educational attainment, socioeconomic status (SES), health status and behavior, criminal behavior, and family outcomes (tables S3–S5). High school completion, for example, was a high school diploma or equivalent. One indicator of SES was a composite index of education and income. Measures were a combination of administrative and survey data from many sources (e.g., education, crime, and income records) and are theoretically related to the ultimate goal of economic independence.

We estimated effects using probit, linear, and negative binomial regression analysis adjusted for 15 preprogram attributes and weighted by attrition propensities through Inverse Probability Weighting (IPW) (24). IPW has been shown to yield the most efficient estimates (25). The weight was 1/p1, where p1 is the predicted probability of being in the recovery sample (Ri = 1; otherwise 0) for each outcome (i) as a function of 26 predictors known to influence attrition (table S6). Standard errors were corrected for site clustering. Robustness of estimates was fully assessed.

A summary of findings for select outcomes is shown in Table 2 (tables S9). For brevity, we focus on extended intervention for 4 to 6 years versus fewer. Unadjusted group differences are also reported (table S8). We emphasize domains in which two or more indicators shows significance at the .05 level.

Table 2.

Means and Group Differences for Selected Adult Outcomes Adjusted for Attrition by Inverse Probability Weighting (IPW) and Preprogram Characteristics

| Preschool1 | School-Age2 | Extended-13 | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadj diff. |

Interv | Comp | Adj. diff. |

Unadj diff. |

Interv | Comp | Adj. diff. |

Unadj diff. |

Interv | Comp | Diff. | |

| Educational Attainment | ||||||||||||

| On time graduation, % | 9.6** | 44.3 | 36.6 | 7.7* | 7.9** | 44.4 | 35.3 | 9.1* | 12.1** | 48.6 | 31.3 | 17.3** |

| Highest grade completed | 0.3** | 12.1 | 11.9 | 0.3* | 0.2t | 12.1 | 12.0 | 0.0 | 0.3** | 12.2 | 12.0 | 0.3* |

| BA or AA degree, % | 0.8 | 8.4 | 8.5 | −0.1 | 1.4 | 8.8 | 7.4 | 1.4 | 2.1 | 9.5 | 8.3 | 1.2 |

| Socioeconomic Status | ||||||||||||

| SES ≥ 4, % | 7.1* | 34.4 | 28.6 | 5.7* | 2.8 | 32.8 | 31.6 | 1.2 | 6.7* | 35.9 | 30.3 | 5.6* |

| Average annual income | 932** | 11,582 | 10,796 | 786* | 54 | 11,250 | 11,278 | −28 | 1,102t | 11,822 | 10,942 | 880 |

| Food stamp participation, ages 24–27, % | 2.5 | 49.1 | 44.8 | 4.3 | −2.9 | 43.9 | 52.0 | −8.1* | −1.8 | 45.0 | 48.9 | −3.9 |

| Health status and behavior | ||||||||||||

| Any insurance, % | 10* | 75.9 | 63.9 | 12.0** | 0.3 | 70.5 | 73.7 | −3.1 | 6.7* | 75.7 | 69.6 | 6.1** |

| Substance abuse (excluding alcohol), % | −6.5** | 13.7 | 18.9 | −5.2* | −0.1 | 16.1 | 14.7 | 1.4 | −3.6 | 14.3 | 16.2 | −1.9 |

| Crime and justice system involvement | ||||||||||||

| Any adult arrest, % | −6.2* | 47.9 | 54.3 | −6.4* | 4.9t | 52.4 | 47.5 | 4.9t | −1.5 | 51.1 | 49.7 | 1.4 |

| Any felony charge, % | −6.4** | 19.3 | 24.6 | −5.3* | 1.2 | 21.6 | 20.4 | 1.2 | −3.2 | 19.5 | 21.2 | −1.7 |

Note.

Adjusted for school-age participation, 8 indicators of pre-program risk status, sex of child, race/ethnicity, child welfare history by age 4, neighborhood poverty at 1980, a dummy-coded variable for missing data on risk status, and home environment at ages 0–5.

Adjusted for preschool participation, 8 indicators of pre-program risk status, sex of child, race/ethnicity, child welfare history by age 4, neighborhood poverty at 1980, a dummy-coded variable for missing data on risk status, and home environment at ages 0–5.

Adjusted for 8 indicators of pre-program risk status, sex of child, race/ethnicity, child welfare history by age 4, neighborhood poverty at 1980, a dummy-coded variable for missing data on risk status, and home environment at ages 0–5.

All adjusted models used robust standard errors, and attrition was adjusted through including inverse probability weighting (IPW) of being in the study sample as a sampling weight in the model. Sample sizes vary by measures.

p < .01

p < .05, and

t < .10

Relative to the comparison group, the preschool group had significantly higher levels of educational attainment for 4 of 6 measures, including highest grade completed (12.2 vs. 11.9, p = 0.03) and attendance in a 4-year college (14.7% vs. 11.2%; p = 0.04). These educational advantages translated to higher economic status, including occupational prestige (2.8 vs. 2.5; p = 0.03), an SES composite score (education and income) of 4 or higher (34.4% vs. 28.6%; p = 0.03; scale of 0–8), and annual income ($11,582 vs. $10,796; p = 0.001). Moreover, a higher percentage had an occupational prestige level of 4 or higher (28.2% vs. 21.4%; p = 0.01), synonymous with postsecondary training. No differences were detected for degree completion or employment (table S9).

School-age participation was associated with a higher rate of on-time high school graduation while extended intervention was linked to highest grade completed (12.2 vs. 12.0, p = 0.02), SES composite (35.9% vs. 30.3%; p = 0.036) but only the occupational prestige index (3.1 vs 2.7, p = 0.017; tables S9). Based on the alternative extended-intervention contrast, only on-time high school graduation differed between groups (table S9). This conservative test minimizes any possible synergistic effect of intervention, however, because kindergarten achievement was included.

The preschool group had a higher rate of health insurance coverage (75.9% vs. 63.9%; p < 0.01), including private insurance (49.1% vs. 39.5%; p = 0.01). They also had significantly lower rates of substance abuse (13.7% vs. 18.9%; p = 0.01) and drug and alcohol abuse (16.5% vs. 23.0%; p < 0.001; table S9). The extended program group had higher rates of insurance coverage but this difference was not found for the alternative contrast.

The preschool group also had lower rates of crime and justice involvement for any arrests (47.9% vs. 54.3%; p = 0.03), felony arrests (19.3% vs. 24.6%; p = 0.02), and incarceration (15.2% vs. 21.1%; p = 0.04). Because the latter two outcomes were measured from official records, they are more severe and have higher costs. No differences were detected for the number of arrests or for convictions. School-age and extended intervention were unrelated to justice involvement. For public aid and family outcomes, no meaningful differences were found (table S9).

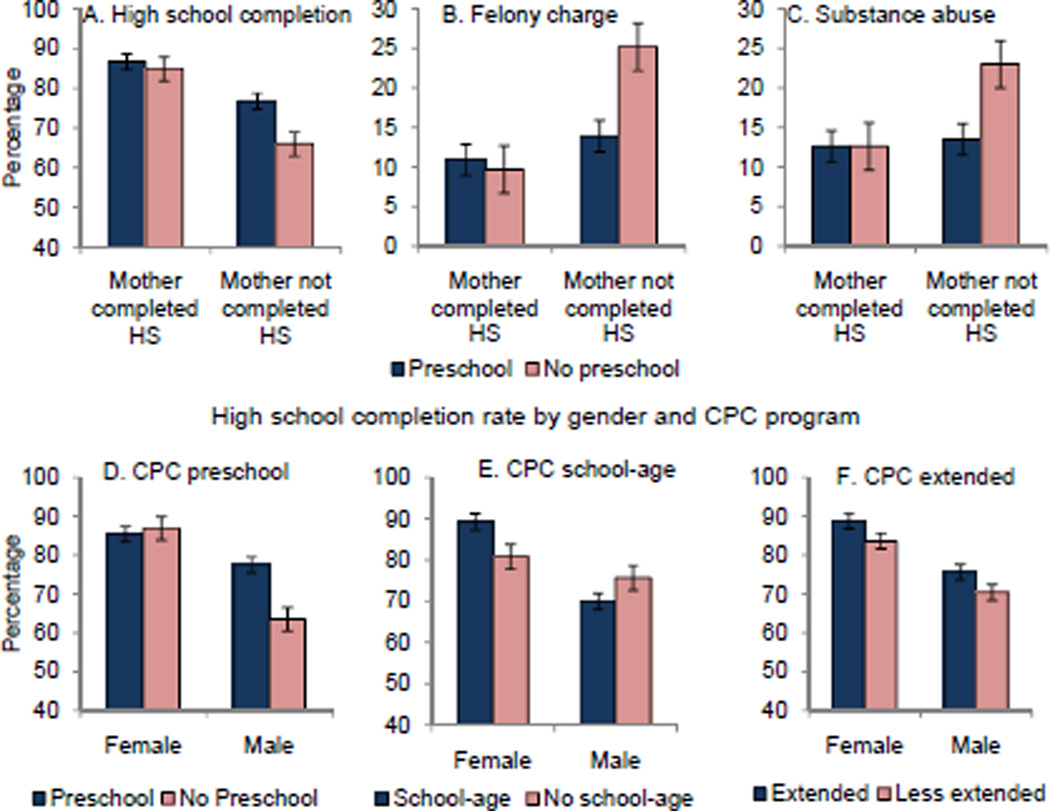

Although subgroup differences were detected, they were limited to specific outcomes and intervention components (table S11). The most consistent evidence was for gender and parent education. Figure 1 shows the primary findings. Male preschool participants showed substantially greater well-being than the male comparison group for high school completion (77.5% vs. 63.5%; p < 0.001) and substance abuse (33.7% vs. 42.9%; p = 0.002) whereas female program groups had similar rates. In contrast, females showed comparatively greater effects of school-age intervention than males. Because this latter finding was not found for another outcome, cautious interpretation is warranted.

Fig. 1.

Well-being for selected outcomes by maternal education, gender, and program groups. Error bars represent ±1 SE. Means and rates on the outcome are adjusted for 15 preprogram characteristics (table S2) and attrition by IPW. Extended intervention is 4 or more years of CPC participation from preschool to third grade versus participation for 3 years of less. Outcomes were measured by age 28 from multiple source including administrative data and adult surveys. Mothers education was measured by age 3 of the study participant.

In addition, preschool participants whose parents were high school dropouts showed significantly larger effects than participants of graduates for high school completion, felony arrest, and substance abuse. For example, preschool participants of high school dropouts had a rate of felony arrest (13.9%) that was nearly half the rate for the comparison group of school dropouts (25.2%). A similar risk indicator— 4 or more family risks—also moderated preschool impacts on felony arrest and substance abuse. While these findings support the compensatory value of intervention, we found no differences by race/ethnicity, early home environment, and other factors. A similar pattern was found for extended intervention.

For program dosage within components, length of preschool was unrelated to well-being (table S12). School-age participation for 2 or 3 years was linked to higher rates of on-time high school graduation (48.5% vs. 35.5%; p < 0.05). Relative to 4 years, extended intervention for 5 or 6 years was linked only to a lower rate of arrest for violence (13.4% vs. 20.8%; p < 0.01) but this was also found for the alternative contrast (14.1% vs. 19.3%; p = 0.02).

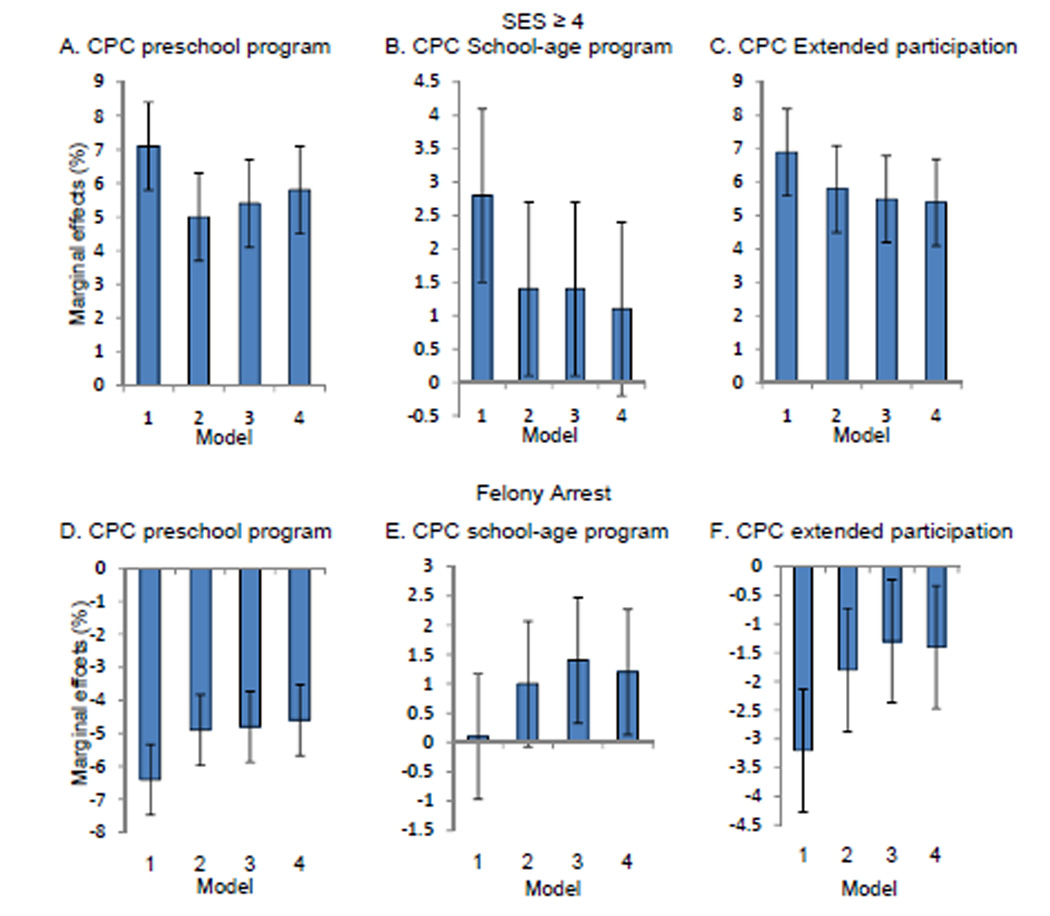

To assess the robustness of estimates, we tested five additional model specifications for each intervention contrast, ranging from no adjustment on preprogram attributes to inclusion of covariates, and IPW-attrition and IPW-selection adjusted models. For the latter, the inverse of the estimated propensity score for program participation (17 predictors; table S6) was multiplied by IPW-attrition and this product was the model weight. Other propensity methods such as matching yielded similar findings (table S7, Fig. S4).

We found evidence of consistency across model specifications. The predominant pattern is shown in Figure 2 for moderate or higher SES and felony arrest. This generalized to subgroup estimates reported above. Among the four specifications shown, the unadjusted group differences for SES (7.1 points) and felony arrest (6.4 points) are slightly higher than the adjusted rates but the type of adjustment, including the double correction, did not affect estimates in any meaningful way. The reduction over the comparison group in felony arrest was 27% whereas for SES it was an increase of 20%. These findings strengthen confidence in the beneficial effects of intervention.

Fig. 2.

Robustness estimates for SES and felony arrest by model specification. Error bars represent ±1 SE. The y axis represents marginal effects in percentage points. Models are adjusted for 15 preprogram characteristics (table S2) except Model 1. Models 1 is unadjusted. Model 2 is adjusted with covariates. Model 3 is adjusted for attrition by IPW. Model 4 is adjusted for attrition and program selection by IPW. Base rates of unadjusted comparison group are (A) 29.3%. (B) 32.4%, (C) 31.4%, (D) 25.6%, (E) 21.5%, and (F) 22.7%.

The interpretation of findings as the true influence of intervention is further supported by corroboration that five sets of mediators can account for effects. In this model, participation impacts well-being through the accumulation of cognitive skills, social adjustment, motivation, and family and school support behaviors from school entry up to early adulthood (26). We found that these mediators explained 60% or more of the observed effects of preschool and nearly 40% or more for extended intervention (table S13). The mediators completely accounted for effects on SES, education, and felony arrest. The process of influence is initiated by the impact on cognitive skills at age 5 and parent involvement and continues through socio-emotional adjustment, school quality and reductions in problem behavior. These paths have been found for outcomes at younger ages (20, 27).

Overall, we found that the most consistent and enduring effects were for preschool participation starting at age 3. Its impact was broad, including education, SES, health behavior, and crime outcomes. Since the program affected multiple indicators within these domains, impacts are unlikely to be artifacts of measurement. Findings for later intervention were limited primarily to education while those for extended intervention were exclusive to education and economic well-being. Because of the high avoidable costs of school dropout and related problems (28, 29), our findings strengthen evidence that sustained, publicly-funded early education can be a cost-effective strategy for promoting well-being.

The enduring effects of the program were observed within a social context characterized by high levels of risk that substantially counteract the positive influences of early experience (30, 31). In addition to residing in neighborhoods of persistent poverty where the majority of students fail to complete high school, over half of participants changed schools frequently, only 25% of participants attended schools of relatively high quality. That the program, especially in preschool, showed such broad and practically significant effects on well-being despite these environmental challenges is encouraging for prevention programming.

That male participants and those from higher risk families showed the largest preschool effects is consistent with prior studies (3, 4, 7), and given our estimation, cannot be due to differential attrition. The advantage for males was found even with no initial group differences (table S2). These findings suggest that early interventions can reduce health disparities, especially if they impact educational attainment, a key path to later health and SES (10, 32). One implication is that national goals of increasing quality and years of healthy life can be achieved in part through access to quality educational programs.

The study also shows the potential limits of the long-term effects of dosage within program components. Although extended intervention linked to well-being, the number of years of preschool and extended services was unrelated to most outcomes. Consistent with other studies (2, 33), greater dosage of school-age intervention was linked to high-school graduation. These results suggest that among high quality programs there may be a threshold beyond which effects diminish. In previous studies (34, 35), however, preschool and extended-intervention dosage was associated with improved child and adolescent well-being including school readiness, remedial education, child maltreatment, and delinquency.

In conclusion, early education programs can impact life-course outcomes necessary for economic success and good health. The findings of this study indicate that while there are limits to the effects of the CPC program for particular outcomes and groups, impacts which endured provide a strong foundation for the investment in and promotion of early childhood learning.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grants from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (HD034294) and the McKnight Foundation. We thank the Chicago Public Schools for invaluable collaboration on the study over the years. We also are grateful to the Illinois Departments of Human Services, Corrections, Child and Family Services, and Public Aid; Circuit and Juvenile Courts of Cook County; City Colleges of Chicago; Chapin Hall Center for Children at the University of Chicago; and the Health Survey Center at the University of Minnesota for assistance and cooperation in data collection.

Contributor Information

Arthur J. Reynolds, University of Minnesota.

Judy A. Temple, University of Minnesota.

Suh-Ruu Ou, University of Minnesota.

Irma A. Arteaga, University of Missouri.

Barry A. B. White, University of Minnesota.

References and Notes

- 1.Camilli G, Vargas S, Ryan S, Barnett WS. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2010;112:579. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Temple JA, Reynolds AJ. Econ. of Educ. Rev. 2007;26:126. doi: 10.1016/j.econedurev.2013.07.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zigler E, Gilliam WS, Jones SM. A vision for universal preschool education. New York: Cambridge University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karoly LA, Kilburn MR, Cannon JS. Early childhood intervention: Proven results, future promise. Santa Monica, CA: RAND; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Melhuish EC, et al. Science. 2008;321:1161. doi: 10.1126/science.1158808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gormley WT, Phillips D, Gayer T. Science. 2008;320:1723. doi: 10.1126/science.1156019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reynolds AJ, Temple JA. Ann. Rev. Clin. Psych. 2008;4:109. doi: 10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.3.022806.091411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Consortium for Longitudinal Studies. As the twig is bent…lasting effects of preschool programs. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum; 1983. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schweinhart LJ, et al. Lifetime effects: The High/Scope Perry Preschool study through age 40. Ypsilanti, MI: High/Scope Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Braveman P, Barclay C. Pediatrics. 2009;124:S163. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-1100D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.DHHS US. Head Start impact study: Final report. Washington, DC: Author; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pianta RC, Belsky J, Houts R, Morrison F. Science. 2007;315:1795. doi: 10.1126/science.1139719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.For further information, materials and methods are available as supporting material on Science Online.

- 14.Lachman ME. Ann. Rev. Psych. 2004;55:305–331. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.55.090902.141521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nation M, et al. Am. Psych. 2003;58:449. [Google Scholar]

- 16.McCormick MC, et al. Pediatrics. 2006;117:771. doi: 10.1542/peds.2005-1316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Johnson DL, Blumenthal J. J of Prim. Prev. 2004;25:195. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Imbens GW, Wooldridge JM. J. of Econ. Lit. 2009;47:5. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chicago Longitudinal Study. User’s guide, version 7. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reynolds AJ. Success in early intervention: The Chicago Child-Parent Centers. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Garces E, Thomas D, Currie J. Am. Econ. Rev. 2002;92:999. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reynolds AJ, et al. Arch. Ped. & Adol. Med. 2007;161:730. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.161.8.730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Naisbitt N. Child-Parent Education Centers: ESEA Title I, Activity I. Chicago: Unpublished report; 1968. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robins JM, Hernan MA, Brumback B. Epidemiology. 2000;11:550. doi: 10.1097/00001648-200009000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirano K, Imbens GW, Ridder G. Econometrica. 2003;71:1161. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reynolds AJ, Ou S. Child Dev. 2011;82:555. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01562.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reynolds AJ, Ou S, Topitzes JW. Child Dev. 2004;75:1299. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2004.00742.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cohen MA. The costs of crime and justice. New York: Routledge; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 29.O’Connell ME, Boat T, Warner KE. Preventing mental, emotional, and behavioral disorders among young people. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2009. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sampson RJ, Sharkey P, Raudenbush SW. PNAS. 2008;105:845. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710189104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chase-Lansdale PL, et al. Science. 2003;299:1548. doi: 10.1126/science.1076921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Singh-Manoux A, et al. Int. Jour. of Epidem. 2004;33:1072. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hawkins JD, et al. Arch. Ped.& Adol. Med. 2008;162:1133. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.162.12.1133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reynolds AJ. Early Child. Res. Quart. 1995;10:1. doi: 10.1016/j.ecresq.2019.08.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Reynolds AJ, Ou S, Temple JA. Child Welf. 2003;82:379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.