Abstract

The portacaval anastamosis (PCA) rat is a model to examine nutritional consequences of portosystemic shunting in cirrhosis. Alterations in body composition and mechanisms of diminished fat mass following PCA were examined. Body composition of male Sprague-Dawley rats with end-to-side PCA and pair-fed sham-operated (SO) controls were studied 3 wk after surgery by chemical carcass analysis (n=8 each) and total body electrical conductivity (n=6 each). Follistatin, a myostatin antagonist, or vehicle was administered to PCA and SO rats (n=8 in each group) to examine whether myostatin regulated fat mass following PCA. The expression of lipogenic and lipolytic genes in white adipose tissue (WAT) was quantified by real-time PCR. Body weight, fat-free mass, fat mass, organ weights, and food efficiency were significantly lower (P < 0.001) in the PCA than SO rats. Adipocyte size and triglyceride content of epididymal fat in PCA rats were significantly lower (P < 0.01) than in SO rats. Myostatin expression was higher in the WAT of PCA compared with SO rats and was accompanied by an increase in phospho-AMP kinase Thr172. Follistatin increased whole body fat and WAT mass, adipocyte size, and expression of lipogenic genes in WAT in PCA, but not in SO rats. Myostatin and phospho-AMP kinase protein and lipolytic gene expression were lower with follistatin. We conclude that PCA results in loss of fat mass due to an increased expression of myostatin in adipose tissue with lower lipogenic and higher fatty acid oxidation gene expression.

Keywords: carcass analysis, total body electrical conductivity, fat mass, lipogenesis, fatty acid oxidation, AMP kinase

in addition to sarcopenia or skeletal muscle loss, reduced fat mass has also been shown to be an independent predictor of outcome in cirrhotic patients (1, 34). The creation of an end-to-side portacaval anastamosis (PCA) in rats results in nutritional, biochemical, behavioral, and endocrine consequences at 3 wk after surgery that are similar to those observed in human cirrhosis with portosystemic shunting (11, 14, 15). An increased phosphorylation and activation of skeletal muscle AMP kinase (AMPK)-α, a critical cellular energy sensor, suggests that lower energy supplies may be responsible for impaired muscle protein synthesis following PCA (12, 19). The contribution of the reduction in fat mass to the changes in body composition and the mechanisms responsible for this following PCA are not known (10, 11, 15). Adipose tissue is the major energy store in the body, and reduction in fat mass is likely to contribute to reduction in whole body energy supplies (32). An understanding of the mechanisms contributing to the lower fat mass following PCA is important because of the regulatory role of fatty acids on skeletal muscle protein turnover (42). In the present study, we examined the contribution of reduced fat mass to changes in body composition and the potential mechanisms for reduced fat mass following PCA.

Our laboratory has previously shown that higher expression of myostatin, a member of the transforming growth factor-β superfamily, in PCA rats was responsible for the lower skeletal muscle mass in this model (12, 13). The regulation of fat mass by myostatin has been shown in studies on myostatin knockout mice, follistatin (myostatin antagonist) transgenic mice, and exogenous administration of myostatin (21, 25, 28, 36). The signaling pathways involving myostatin have been extensively studied in skeletal muscle, but its role in adipose tissue and lipid metabolism has not been examined in conditions associated with loss of fat mass (16, 38). In the present study, we examined the expression of myostatin in white adipose tissue (WAT) following PCA, its relation to fat mass, adipocyte size, and triglyceride content, and the expression of genes regulating lipogenesis and lipolysis. To establish a mechanistic link between myostatin and adipose tissue mass, we administered follistatin, a myostatin antagonist to PCA rats, and examined the response of whole body fat mass, epididymal fat mass, expression of myostatin, and genes regulating lipogenesis and lipolysis in the adipose tissue.

ANIMALS AND METHODS

Animals

Male Sprague-Dawley rats (weight 200–260 g), with an end-to-side PCA (n=30) or sham surgery (n=30), were obtained from Charles River (Wilmington, MA). Animals were housed individually in wire mesh-bottom cages under strictly controlled conditions of temperature, lighting (12:12-h light-dark cycles), and humidity. Following 3 days of recovery after the surgery, all sham-operated control rats were pair fed (SO) to the PCA rats. All animals were placed on standard rat chow (Harlan Teklad standard rat chow, no. 8604: protein 24.5%; fat 4.4%; 3.93 kcal/g) for 3 wk. Food and water intake were measured daily. Animals were weighed, and their fat-free mass was measured using total body electrical conductivity (TOBEC) at weekly intervals for 3 wk. The preoperative weight of each animal was used as a baseline weight during the experiment. Food efficiency was calculated as the gain in total body weight per gram of food intake (g weight gain/g food intake) (15). All animals had access to food and water up to 1 h before being killed. At necropsy, anatomic patency of the shunt was confirmed in all animals. There were no deaths or animal dropouts during the study.

Fecal Fat Excretion

Fecal fat excretion was quantified because fat malabsorption can contribute to alterations in fat mass. The stool consistency was visually inspected each day, and fresh feces was collected to quantify fat content using previously described methods (39). In brief, ∼0.5 g of feces was dried in a convection oven at 65°C for 24 h and treated with 18 N sulfuric acid, and the fat was extracted with 10 ml of ether with constant shaking for 25 min. The extraction with ether was repeated to ensure complete removal of fecal fat. All studies were done in triplicate on at least two samples of feces from each animal.

Body Composition

The study was done in three phases in distinct groups of animals. In the first phase of the study, chemical carcass analysis was performed in the PCA (n=8) and SO rats (n=8). All animals were killed using intraperitoneal pentobarbitone at 3 wk after surgery. Before the carcass analysis, the liver, gastrocnemius muscle, kidneys, testes, and spleen were harvested and weighed. In addition, mesenteric fat that included omentum, perinephric, retroperitoneal, and epididymal pad of fat were used as a direct measure of visceral fat mass. After weighing, ∼100 mg of skeletal muscle were separated for quantifying the hydration index, and the remaining tissue was used for chemical carcass analysis, along with the other organs harvested and the remaining carcass.

In a separate group of PCA (n=6) and SO animals (n=6), TOBEC was performed at 3 wk after surgery. The animals were then killed using intraperitoneal pentobarbitone; blood was collected from the abdominal aorta; and organs were harvested, blotted dry of blood, weighed, rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80°C for subsequent assays.

Finally, in a third group of animals, follistatin, a myostatin antagonist, prepared as described earlier (12) in the dose of 10 μg/100 g body wt (n=8 for PCA and SO in each treatment group) or an equal volume of phosphate-buffered saline as control (n=8 for PCA and SO in each treatment group) was administered intraperitoneally three times a week for the 2 wk (weeks 3 and 4 after surgery), the changes in body composition were measured using TOBEC, and gene expression was studied. The response of skeletal muscle to follistatin has been reported elsewhere (12).

Chemical Carcass Analysis

Chemical carcass analysis was performed in a subgroup of rats with end-to-side PCA (n=8) or SO rats (n=8) 3 wk after surgery. Animals were killed, and organs were harvested and weighed, following which chemical carcass analysis was performed (8). In brief, the animals were shaved, and the organs harvested as described earlier. The whole carcass, including the organs that had been weighed, were pulverized and completely dried in a mechanical convection oven at 60°C to reach a stable weight for 3 days. The water content in the carcass was measured by the difference between the original wet weight and the final dry weight.

A precisely weighed amount (0.5 g) of the powdered carcass sample was mixed with 0.5 ml ethyl alcohol (100%) and 10 ml ethyl ether and vortexed for 30 min, and the supernatant ether layer was removed following centrifugation at 1,800 rpm for 4 min. Residual fat was extracted by an additional 10 ml of ethyl ether. The pellet was then air dried for 3 h and then placed in a convection oven at 60°C over night. The dried sample was weighed three times at two hourly intervals until a constant weight was achieved. The fat content was calculated as the difference between the original weight and weight of the pellet after ether extraction.

Hydration Index

Hydration index of the whole body and skeletal muscle was calculated using the following formula: (wet weight − dry weight)/wet weight. The wet weight and dry weight of the carcass or skeletal muscle were measured by complete drying of a precisely weighed amount of the pulverized carcass or a sample of the skeletal muscle in a convection oven, as described above.

Proportion of Visceral Fat Content

The proportion of visceral fat in the abdomen was obtained as the ratio of the visceral fat to the whole body weight. Nonvisceral fat mass was obtained in the animals that were subjected to chemical carcass analysis as the difference between the visceral fat mass and total body fat mass.

Measurement of Fat-Free Mass Using TOBEC

In a subsequent group of rats (n=6 each in PCA and SO rats), fat-free mass was measured at 3 wk after surgery, using the TOBEC body analyzer for small animals (SA-3000) fitted with the 114 × 318 mm measuring chamber (SA-3114) (EC Systems, Springfield, IL) using the methods previously described by our laboratory (13).

Tissue Extraction and Processing

Tissue was processed as previously described (11). In brief, a part of the epididymal fat was homogenized, and RNA extracted using the TRI reagent per the manufacturer's protocol (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The isolated RNA was resuspended in diethyl pyrocarbonate-treated water and quantified by spectrophotometry, and the quality was assessed by electrophoresis in a 1.2% formaldehyde agarose gel. First-strand cDNA synthesis was performed using 1 μg of total RNA using BD Clontech kit (Hercules, CA) per manufacturer's protocol. Oligonucleotide primers used for the various genes were as published earlier (11, 13). Other primers used included the following: adiponectin (forward: 5′-AAT CCT GCC CAG TCA TGA AG, reverse: 5′-TCT CCA GGA GTG CCA TCT CT); adiponectin receptor 1 (forward: 5′-GAC AAA GCC CTC AGC GAT, reverse: 5′-CTT CTA CTG CTC CCC ACA GC); adiponectin receptor 2 (forward: 5′-ACC CAC ACC CTT GCT TCA TC, reverse: 5′-GCT AGC CAT GAG CAT TAG CC); acyl-CoA carboxylase (forward: 5′-AGG AAG ATG GTG TCC GCT CTG, reverse: 5′-GGG GAG ATG TGC TGG GTC AT); acyl-CoA oxidase (forward: 5′-CCC GTA GCA CTC TCC TTG AG, reverse: 5′-TTG GAA ACC ACT GCC ACA TA); fatty acid synthase (forward: 5′-TCG AGA CAG ATC GTT TGA GC, reverse: 5′-TCA AAA AGT GCA TCC AGC AG); fatty acyl-CoA binding protein (forward: 5′-GAA GCG CCT GAA GAC TCA GC, reverse: 5′-TTC AGC TTG TTC CAC GAG TCC); peroxisome proliferator activated receptor (PPAR)-α (forward 5′-TGA ACA AAG ACG GCA TG, reverse: 5′-TCA AAC TTG GGT TCC ATG AG); sterol regulatory element binding protein-1 (forward: 5′-AGC GCT ACC GTT CCT CTA TC, reverse: 5′-GCG CAA GAC AGC AGA TTT AT); stearoyl-CoA desaturase (forward 5′-GCT TCC AGA TCC TCC CTA CC, reverse 5′-CAA CAA CCA ACC CTC TCG TT); tumor necrosis factor-α (forward: 5′-ACG ATT ATC ACG CTA C-3, reverse: 5′-TCA ATG CCT AAG TTG GA-3).

Quantitative real-time PCR.

Real-time PCR for quantification of mRNA was performed on a Stratagene Mx 3000 P (Stratagene, La Jolla, CA) using a SYBR protocol on the fluorescence temperature cycler. Results were expressed as fold change in expression of each gene in the PCA compared with control SO animals using a relative quantification method. In addition, the gene product for myostatin in fat was confirmed by gene sequencing. All PCR products were separated on a 1.5% Tris-acetic acid agarose electrophoresis to confirm product presence and size.

Western blot analysis.

The expression of myostatin and adiponectin protein was quantified by Western blot assays as described earlier (11). In brief, epididymal fat samples (100 mg) were homogenized in 1 ml of lysis buffer (1% Triton X, 50 mM Tris, 6.4 mM NaCl, 1 mM EDTA, 1 mM sodium pyrophosphate, 1 mM sodium orthovanadate, 10 mM sodium chloride) with protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). The homogenate was subsequently centrifuged at 10,000 g at 4°C for 30 min to remove the tissue debris. The protein concentration of the supernatant was quantified using a Bio-Rad DC protein assay. Twenty micrograms of protein from each sample were then separated using SDS-PAGE 4–20% gradient gel under reducing conditions. After an overnight electrotransfer to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes (Bio-Rad), the membranes were stained with Ponceau S to confirm equal loading and uniformity of transfer, and then they were destained in Tris-buffered saline with Tween [TBST; 0.05 M Tris, pH 7.4, 0.1 M NaCl, 0.1% Tween 20 (Sigma-Aldrich)] and blocked in TBST containing 10% nonfat milk at room temperature for 4 h. Membranes were incubated in primary antibody in TBST overnight at 4°C, followed by washing in TBST. The membranes were then incubated in the appropriate secondary antibody conjugated to peroxidase for 1 h at room temperature. Membranes were washed in TBST, and horseradish peroxidase activity was detected using enhanced chemiluminescent reagent (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ). Band intensities were quantified by densitometry (Bio-Rad GL710) using multianalyst software (Bio-Rad). Myostatin antibody (1:200 dilution) detected 15-, 25-, and 42-kDa bands, as reported earlier (11), and the active protein in the 25 kDa was used to quantify the expression of myostatin in these studies.

Adipose Tissue Triglyceride and DNA Content

Adipose tissue triglyceride content in the epididymal fat was measured by determination of glycerol using the enzyme glycerol phosphate oxidase after hydrolysis with lipoprotein lipase. The manufacturer protocol was followed for the kit (Pointe Scientific, Canton, MI). Adipose tissue DNA content was measured with an ultrasensitive fluorescent DNA stain (Picogreen dsDNA reagent kit), obtained from Molecular Probes (Eugene, OR), using the manufacturer's protocol.

Adipocyte Size

Epididymal fat tissue was fixed in 10% formaldehyde and embedded in paraffin block, and 10-μm sections were stained with hematoxylin and eosin and examined under a light microscope for examination of cell size, inflammatory cell infiltration, and nuclear location in the cells. Briefly, microphotographs of isolated adipocytes were acquired from fields that were occupied mainly by fat cells and had minimal stromal-vascular region. A light microscope equipped with a charge-coupled device camera (Olympus XI 91) was used to quantify the area of 800–1,000 cells using ImagePro software (Media Cybernetics, Bethesda, MD). The area of the cells was then expressed as a proportion of the total number of cells examined. The mean area of the adipocytes was also calculated.

Plasma Adiponectin

Plasma adiponectin was quantified using an ELISA kit (Alpco Diagnostics, Salem, NH) using the manufacturer's protocol in triplicate in all samples. The values were expressed as mean ± SD.

The animals received humane treatment, and the studies were in compliance with the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) guidelines at Case Western Reserve University and the guidelines for the American Physiological Society. This study was approved by the IACUC at the Cleveland Clinic and at Case Western Reserve University.

Statistical Analysis

Sample size was calculated based on our laboratory's previous data correlating TOBEC with chemical carcass analysis in normal rats (13). A minimum of six animals were examined in each group. All data are expressed as means ± SD, unless stated otherwise. Results were compared using a standard statistical package (SPSS 14; SPSS, Chicago, IL). Unpaired Student's “t”-test was used to compare the data in the PCA and SO rats. The Mann-Whitney test was used to compare skewed data.

RESULTS

The PCA rats gained significantly less weight than the comparable SO rats in groups subjected to TOBEC and carcass analysis, as shown in Table 1. There was no evidence of ascites or subcutaneous edema in the animals at the time of necropsy. The average food intake was similar in the PCA and SO rats. However, the food efficiency was significantly lower in the PCA rats compared with the SO rats. Both the fat-free mass and fat mass were significantly lower in the PCA rats (Table 1). None of the rats in either group developed steatorrhea or diarrhea. Fecal fat quantification showed that the amount of fat in the PCA (55 ± 3 mg/g dry fecal wt) and SO (57 ± 2 mg/g dry fecal wt) rats was similar (P > 0.1). The skeletal muscle hydration index in the PCA rats (0.74 ± 0.02) was similar (P > 0.1) to that in the SO rats (0.73 ± 0.01). The whole body hydration index was also similar (P > 0.1) in the PCA (0.673 ± 0.005) and SO animals (0.683 ± 0.009). Rectal temperatures in the PCA (38.8 ± 0.2°C) and SO rats (38.9 ± °C) were also similar (P > 0.1).

Table 1.

Characteristics of PCA and sham rats

| PCA | Sham | |

|---|---|---|

| N | 14 | 14 |

| Preoperative weight, g | 235.8±7.1 | 235.8±6.9 |

| Weight at 3 wk, g | 239.6±7.1 | 354.2±5.5b,c |

| Growth, %change in weight | 1.7±1.4 | 51.2±11.0d |

| Daily food intake, g | 24.8±1.8 | 26.2±0.5a |

| Food efficiency | 0.002±0.009 | 0.22±0.008b |

| FFM at week 3, g | 208.6±4.9 | 286.7±4.9b |

| Fat mass at week 3, g | 27.6±2.9 | 67.5±3.8d |

| Fat/body weight, % | 11.5±1.0 | 19±0.9d |

Values are means ± SD; N, no. of rats. Data are from animals in both chemical carcass analysis [n=8 in portacaval anastamosis (PCA) and sham each] and total body electrical conductivity (n=6 in PCA and sham each). FFM, fat-free mass. Fat/body weight, ratio of fat mass to body weight. aNonsignificant between PCA and sham. bP < 0.001 between PCA and sham. cP < 0.001 between preoperative weight and weight at 3 wk. dP < 0.0001 between PCA and sham.

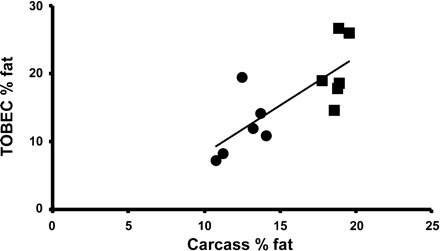

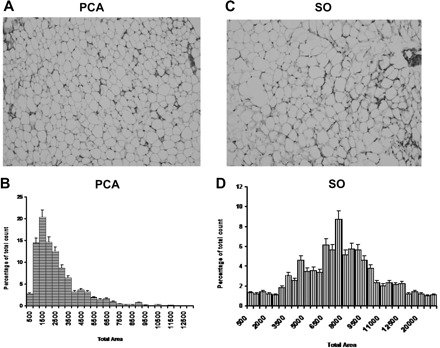

The individual organ weights in the PCA and SO rats group are shown in Table 2. The liver, skeletal muscle, spleen, and testes weights, as well as the ratio of these weights to the fat-free mass, were significantly lower in the PCA compared with SO rats. In Fig. 1, fat mass quantified using chemical carcass analysis showed a high correlation with that obtained by TOBEC (r2=0.77; P < 0.01). As shown in Table 3, using carcass analysis, it was observed that the whole body fat mass was significantly lower (P < 0.0001) in the PCA compared with the SO rats. The visceral and nonvisceral fat masses were significantly lower in the PCA rats compared with the SO rats. These differences persisted even when the data were expressed as a proportion of the total body weight. The triglyceride-to-DNA (mg/μg) ratio was used to quantify the triglyceride content per cell. It was significantly lower (P < 0.05) in PCA (0.034 ± 0.01) compared with SO rats (0.057 ± 0.008). These changes were accompanied by smaller adipocytes in PCA rats compared with SO rats on microscopy (Fig. 2). Plasma adiponectin levels were significantly higher (P < 0.05) in PCA (602.8 ± 37.8 μg/ml) compared with SO (373.8 ± 19.6 μg/ml).

Table 2.

Organ weights in PCA and sham rats

| PCA | Sham | |

|---|---|---|

| Liver, g | 7.9±0.5 | 13.6±0.6a |

| Gastrocnemius, g | 0.77±0.04 | 1.26±0.05a |

| Testes, g | 1.05±0.06 | 1.82±0.04a |

| Kidney, g | 1.4±0.05 | 1.6±0.06 |

| Heart, g | 1.4±0.04 | 1.5±0.07 |

| Spleen, g | 0.58±0.05 | 0.84±0.04b |

| Liver/FFM, mg/g | 38.3±2.6 | 48.1±2.5a |

| Muscle/FFM, mg/g | 37.2±1.7 | 45.0±1.6b |

| Testes/FFM, mg/g | 50.6±2.8 | 63.8±2.2a |

Values are means ± SD of 14 animals in each group. Liver/FFM, muscle/FFM, testes/FFM: ratio of liver, muscle, and testes weight to FFM, respectively. aP < 0.001 between PCA and sham. bP < 0.01 between PCA and sham.

Fig. 1.

The whole body fat mass measured using total body electrical conductivity (TOBEC) in the portacaval anastamosis (PCA; ●) and sham-operated, pair-fed (SO) control rats (■) at 3 wk after surgery showed a high correlation (r2=0.77; P < 0.01) with that measured using direct chemical carcass analysis.

Table 3.

Fat mass in the different compartments in the chemical carcass analysis group

| Compartment | PCA | Sham |

|---|---|---|

| Whole body fat mass, g | 26.7±1.4 | 61.2±2.0a |

| Fat/body weight, % | 12.1±0.5 | 18±0.6a |

| Visceral fat mass, g | 13.9±0.8 | 25.7±1.6a |

| Visceral fat/body weight, % | 6.3±0.2 | 7.6±0.6a |

| Nonvisceral fat mass, g | 13.0±1.1 | 35.5±2.2b |

| Nonvisceral fat/body weight, % | 5.9±0.5 | 10.4±0.5a,d |

| Visceral fat/nonvisceral fat (ratio) | 1.12±0.1 | 0.75±0.1c |

Values are means ± SD of 8 animals in each group. aP < 0.0001, bP < 0.001, and cP < 0.05 between PCA and sham rats. dP < 0.05 between visceral fat/body weight and nonvisceral fat/body weight in sham animals.

Fig. 2.

A and C: representative photomicrographs of white adipose tissue (WAT) from PCA and SO control rats. B and D: adipocyte distribution by size is shown, demonstrating that a significant proportion of adipocytes is larger in SO than PCA rats (n=6 in each group). Values are means ± SD.

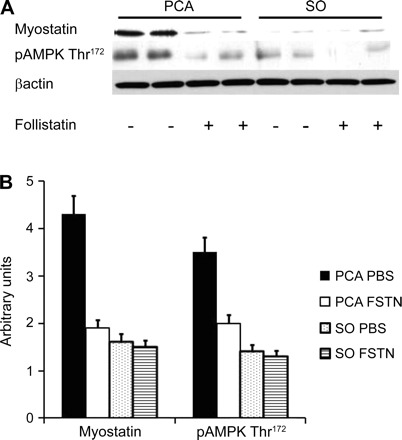

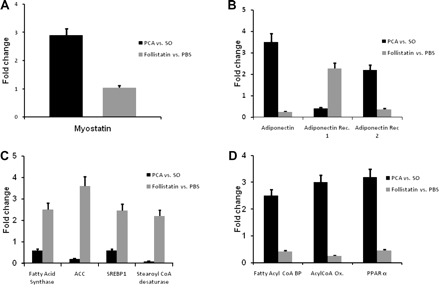

The expression of myostatin gene and protein was higher (P < 0.05) in WAT in PCA compared with SO rats (Figs. 3 and 4). This was accompanied by higher expression of phosphorylated AMPK Thr172 in the adipose tissue and reversed by follistatin (Fig. 3). There was no expression of myostatin protein in hepatic tissue (data not shown). Adiponectin gene expression was significantly higher (P < 0.001) in WAT in PCA compared with SO controls. Expression of adiponectin receptor 1 gene was lower and that of adiponectin receptor 2 gene higher in the WAT of PCA compared with SO controls that were reversed with follistatin (Fig. 4B). Decreased expression of genes regulating lipogenesis (acyl-CoA carboxylase, fatty acid synthase, stearoyl-CoA desaturase, sterol regulatory element binding protein 1) and increased expression of genes regulating fatty acid oxidation (acyl-CoA oxidase, fatty acyl-CoA binding protein, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor-α) were observed in the WAT of PCA compared with SO rats. Blocking myostatin with follistatin results in an increase in whole body weight and fat mass (Table 4), and the alteration in gene expression was reversed following follistatin administration (Fig. 4, C and D).

Fig. 3.

A: representative Western blots in PCA and SO rats for myostatin and phosphorylated adenosine monophosphate kinase (pAMPK) Thr172 with follistatin (FSTN; myostatin antagonist) and vehicle [phosphate-buffered saline (PBS)] for 2 wk. B: arbitrary densitometry of Western blots (n=8 in each group) of PCA and SO control rats treated with FSTN or vehicle alone. Myostatin protein expression was significantly higher in PCA rats and was accompanied by higher expression of pAMPK Thr172 in PCA rats treated with vehicle alone compared with SO rats. These were reversed following a reduction in expression of myostatin by follistatin in the PCA rats. Values are means ± SD.

Fig. 4.

Histograms showing relative expression of mRNA by real-time PCR of genes regulating adipose tissue mass and fatty acid metabolism expressed as fold change in PCA compared with SO control rats (solid bars) and the response to FSTN compared with PBS used a vehicle in the PCA rats (shaded bars). ACC, acyl-CoA carboxylase; Acyl-CoA Ox., acyl-CoA oxidase; Adiponectin Rec., adiponectin receptor; Fatty Acyl-CoA BP, fatty acyl-CoA binding protein; PPAR, peroxisome proliferator activated receptor; SREBP, sterol regulatory element binding protein. A: relative expression of myostatin was significantly elevated (P < 0.01) in WAT of PCA rat compared with SO rats. Relative expression of myostatin in WAT did not change (P > 0.1) in response to FSTN compared with vehicle (PBS) alone in the PCA rats. B: relative expression of mRNA by real-time PCR of adiponectin and its receptors in WAT of PCA rats. Adiponectin gene expression was significantly (P < 0.001) higher in WAT of PCA rats compared with SO control rats. Adiponectin receptor 1 expression was lower (P < 0.01), and that of adiponectin receptor 2 was higher (P < 0.01), in PCA compared with SO control rats. In response to FSTN, these alterations were reversed in the PCA rats compared with those administered vehicle (PBS) alone. C: relative expression of genes regulating fatty acid synthesis (fatty acid synthase, ACC, SREBP1, stearoyl-CoA desaturase) were significantly lower in PCA compared with SO control rats. In response to FSTN, a myostatin antagonist, these changes were reversed. D: the expression of genes regulating fatty acid oxidation (fatty acyl-CoA BP; acyl-CoA oxidase; PPAR-α) was significantly (P < 0.01) higher in the PCA compared with SO control rats. FSTN reversed these alterations in the PCA rats compared with those administered vehicle (PBS) alone. Values are means ± SD.

Table 4.

Response of adipose tissue to follistatin in PCA and sham rats

| PCA + Vehicle | PCA + Follistatin | Sham + Vehicle | Sham + Follistatin | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 8 | 8 | 8 | 8 |

| Preoperative weight, g | 266±10.8a | 270.6±7.7a | 269.4±4.9a | 269.5±6.0a |

| Weight at kill, g | 295.2±40.3a | 358.2±28.1c | 383.6±22.5b,c | 381.4±26.6b,c |

| Total body fat mass, g | 39±8.2e | 68.9±13.1f | 76.7±3.8f | 74.2±10.1f |

| Epididymal fat mass, g | 2.8±1.5h | 3.7±1.5i | 3.7±0.6i | 3.9±0.5i |

Values are means ± SD; N, no. of rats. Superscripted a vs. b, e vs. f, g vs. h, and g vs. i: P < 0.01. Superscripted b vs. c, h vs. i: P < 0.05.

DISCUSSION

The present study showed that loss of fat mass, in addition to muscle mass, occurred following portosystemic shunting. We also observed that adipocytes were smaller, expression of genes regulating fatty acid synthesis was lower, while those responsible for fatty acid oxidation in adipose tissue were higher, in PCA compared with SO rats. Myostatin expression was elevated in adipose tissue following PCA. Reduced fat mass, as well as the altered expression of genes regulating adipose tissue fatty acid metabolism in the PCA rat, were reversed by administration of myostatin antagonist, follistatin.

Loss of both visceral and nonvisceral fat mass was observed after 3 wk of PCA compared with SO, pair-fed rats. These observations were similar to those reported in patients with cirrhosis of the liver in whom worsening severity of liver disease was accompanied by a progressive reduction in whole body fat mass (17). The proportion of visceral fat mass was similar to that of the subcutaneous fat mass in the PCA, whereas, in the SO rats, the proportion of the subcutaneous fat mass was higher than that of the visceral fat mass. PCA rats had smaller adipocytes with lower triglyceride per cell, as determined from the area of the cells and the triglyceride-to-DNA ratio. The loss of adipose tissue mass in the PCA rat was due to a combination of impaired expression of genes regulating fatty acid synthesis and increased expression of genes regulating fatty acid oxidation. Lower food intake in the PCA rat may have contributed to these changes, but our studies using pair feeding of the SO control rats demonstrate that these changes are independent of caloric intake. Reversal of these alterations with follistatin provides compelling evidence that myostatin plays a critical role in energy regulation in portosystemic shunting. Even though follistatin binds to other proteins, including activin, its dominant effect, at least, in the skeletal muscle, is due to inhibition of myostatin (6, 24, 28). This suggests that, in the adipose tissue also, response to follistatin may be due to myostatin antagonism. Previous studies have suggested that myostatin increases the expression of AMPK in skeletal muscle (7, 12). Our data are consistent with previous metabolic studies, that adipose tissue lipogenesis is reduced by 60–80% and lipolysis increased twofold in PCA compared with pair-fed SO rats (31), and provide the mechanism for these observations.

Regulation of adipocyte size and expression of genes regulating fatty acid metabolism is a novel finding in this study. Prior studies have shown that exogenous myostatin causes loss of fat mass in vivo (43) and blocks adipogenesis in vitro in the mesenchymal stem cell line, C3H 10T1/2 cells (35). Paradoxically, myostatin knockout mice have lower fat mass, and in vitro studies on the adipocyte committed NIH 3T3 cells suggest that myostatin promotes adipogenesis (2, 36). Our observations of an increased expression of myostatin in the epididymal fat following PCA is consistent with the recent report of a lower body mass and lower fat mass in transgenic mice with increased expression of myostatin in adipose tissue (16). In contrast to our observations on the regulation of adipose tissue mass by local production of myostatin, others have reported that, in myostatin knockout mice, an alteration in skeletal muscle myostatin, but not in adipose tissue, contributes to the change in adipose tissue mass in mice fed either normal chow or high-fat diet (20). This difference could be due to the absence of myostatin from in utero in the knockout mice, in contrast to the postdevelopmental increase in myostatin expression in the fully differentiated adipocytes that were blocked using follistatin. Previous studies have shown that the effect of myostatin on adipocytes depends on the stage of development of the adipocytes (2, 16, 20, 22). Myostatin promotes adipogenesis at a sensitive time before preadipocyte stage, but not after this stage (2). An increased expression of myostatin following PCA in these postpubertal mature rats may have a different effect on adipocyte mass and triglyceride content by regulating the expression of genes responsible for fatty acid oxidation and synthesis. Another observation in the mice with adipose tissue-specific increase in expression of myostatin was the metabolic consequences that included higher insulin sensitivity and an increased metabolic rate with similar food intake and activity that were accompanied by decreased whole body and fat mass (16). In our study, we did not measure metabolic rate, but did observe a lower body weight and fat mass compared with the SO rats, despite similar food intake. An increase in expression of genes responsible for increased fatty acid oxidation may have contributed to the lower fat mass following PCA. We speculate that the increased fatty acid oxidation following PCA may also contribute to the hypermetabolism reported in human cirrhosis (27).

The lower fat mass in the PCA rat was accompanied by higher expression of adiponectin gene in WAT. Higher plasma adiponectin in the PCA rat with lower whole body and visceral fat mass may seem surprising, since adiponectin is secreted by adipocytes (29). This was, however, similar to previous reports of the inverse relation between plasma adiponectin and body fat mass (41). Our observations are also consistent with previous reports that greater visceral adiposity in patients with metabolic syndrome was accompanied by lower plasma adiponectin concentrations, and reduction in whole body fat mass following bariatric surgery results in an increase in plasma adiponectin (4, 9, 40). Studies on the interaction between adiponectin and myostatin will clarify the role of these factors on lipid and glucose metabolism.

Failure to gain whole body and fat-free weight by the PCA rats compared with SO rats, despite similar food intake ensured by pair feeding, was reflected in lower food efficiency. This is not due to defective absorption of nutrients, as evidenced by similar fecal fat content and the absence of overt diarrhea or steatorrhea in our animals. These observations are consistent with previous studies that have demonstrated that protein and fat absorption were not affected by PCA (3, 18, 30). One possible explanation for the lower food efficiency in the PCA rats may be reduced protein synthesis in the skeletal muscle that contributes to over 40% of the fat-free mass (33). This is supported by our observation that the expression of myostatin was increased and that of insulin-like growth factor was reduced following PCA (13). These alterations in gene expression contribute to lower skeletal muscle mass related to lower protein synthesis and impaired regeneration of atrophic muscles (26). An alternate mechanism for the lower food efficiency in the PCA rat may be related to hypermetabolism, as occurs in human cirrhosis (27), but this has not been measured following PCA. In the present studies, even though resting energy expenditure was not measured, rectal temperature was similar in the PCA and SO rats. Finally, a higher rate of protein breakdown in the fat-free compartment following PCA could also result in lower food efficiency, but our previous studies on expression of proteolytic genes do not support this explanation (12, 13). Direct studies on whole body and skeletal muscle protein turnover and resting energy expenditure in the PCA rats will be required to address these issues.

In the present study, we also validated the use of a noninvasive method to measure fat-free mass and fat mass following PCA. Previous reports of the validity of TOBEC have primarily used normal control rats (37). We have demonstrated for the first time that TOBEC is a valid measure of fat-free mass after an intervention that results in lower body weight and portacaval shunting. The chemical carcass analysis showed that there was a high correlation with TOBEC-derived fat-free mass. Previous studies have suggested that TOBEC does not reliably measure the total body content of water when the ratio between intracellular and extracellular water is chronically or acutely altered (5). In the PCA rat, renal handling of water has been reported to be abnormal and could have potentially altered the tissue water content and, consequently, the hydration indexes (23). Our studies on the hydration indexes, however, showed that both skeletal muscle and the whole body hydration were similar in the PCA and SO rats.

In conclusion, the present studies demonstrated that, following PCA, loss of whole body weight was a consequence of a loss in both fat mass and fat-free mass that were observed as lower food efficiency, but these alterations were not accompanied by changes in tissue hydration. Reduced fat mass was due to lower adipocyte size, increased expression of genes regulating fatty acid oxidation, and lower fatty acid synthesis in adipose tissue. These alterations were due to increased expression of myostatin, since the changes were reversed by the myostatin antagonist, follistatin. Reduced adipose tissue energy stores could contribute to the accelerated starvation of cirrhosis and its consequences, including impaired skeletal muscle protein synthesis.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the author(s).

REFERENCES

- 1. Alberino F, Gatta A, Amodio P, Merkel C, Di PL, Boffo G, Caregaro L. Nutrition and survival in patients with liver cirrhosis. Nutrition 17: 445–450, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Artaza JN, Bhasin S, Magee TR, Reisz-Porszasz S, Shen R, Groome NP, Meerasahib MF, Gonzalez-Cadavid NF. Myostatin inhibits myogenesis and promotes adipogenesis in C3H 10T(1/2) mesenchymal multipotent cells. Endocrinology 146: 3547–3557, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Assal JP, Levrat R, Cahn T, Renold AE. Metabolic consequences of portacaval shunting in the rat. Effects on weight, food intake, intestinal absorption and hepatic morphology. Z Gesamte Exp Med 154: 87–100, 1971 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Balagopal P, George D, Yarandi H, Funanage V, Bayne E. Reversal of obesity-related hypoadiponectinemia by lifestyle intervention: a controlled, randomized study in obese adolescents. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 90: 6192–6197, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Battistini N, Virgili F, Bedogni G, Gambella GR, Bini A. In vivo total body water assessment by total body electrical conductivity in rats suffering perturbations of water compartment equilibrium. Br J Nutr 70: 433–438, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Benabdallah BF, Bouchentouf M, Rousseau J, Bigey P, Michaud A, Chapdelaine P, Scherman D, Tremblay JP. Inhibiting myostatin with follistatin improves the success of myoblast transplantation in dystrophic mice. Cell Transplant 17: 337–350, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen Y, Ye J, Cao L, Zhang Y, Xia W, Zhu D. Myostatin regulates glucose metabolism via the AMP-activated protein kinase pathway in skeletal muscle cells. Int J Biochem Cell Biol 42: 2072–2081, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Clark RG, Tarttelin MF. Some effects of ovariectomy and estrogen replacement on body composition in the rat. Physiol Behav 28: 963–969, 1982 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Coughlin CC, Finck BN, Eagon JC, Halpin VJ, Magkos F, Mohammed BS, Klein S. Effect of marked weight loss on adiponectin gene expression and plasma concentrations. Obesity (Silver Spring) 15: 640–645, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Coy DL, Srivastava A, Gottstein J, Butterworth RF, Blei AT. Postoperative course after portacaval anastomosis in rats is determined by the portacaval pressure gradient. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 261: G1072–G1078, 1991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Dasarathy S, Dodig M, Muc SM, Kalhan SC, McCullough AJ. Skeletal muscle atrophy is associated with an increased expression of myostatin and impaired satellite cell function in the portacaval anastamosis rat. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 287: G1124–G1130, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Dasarathy S, McCullough AJ, Muc S, Schneyer A, Bennett CD, Dodig M, Kalhan SC. Sarcopenia associated with portosystemic shunting is reversed by follistatin. J Hepatol 54: 915–921, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dasarathy S, Muc S, Hisamuddin K, Edmison JM, Dodig M, McCullough AJ, Kalhan SC. Altered expression of genes regulating skeletal muscle mass in the portacaval anastomosis rat. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol 292: G1105–G1113, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dasarathy S, Mullen KD, Conjeevaram HS, Kaminsky-Russ K, Wills LA, McCullough AJ. Preservation of portal pressure improves growth and metabolic profile in the male portacaval-shunted rat. Dig Dis Sci 47: 1936–1942, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dasarathy S, Mullen KD, Dodig M, Donofrio B, McCullough AJ. Inhibition of aromatase improves nutritional status following portacaval anastomosis in male rats. J Hepatol 45: 214–220, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Feldman BJ, Streeper RS, Farese RV, Jr, Yamamoto KR. Myostatin modulates adipogenesis to generate adipocytes with favorable metabolic effects. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103: 15675–15680, 2006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Figueiredo FA, Perez RM, Freitas MM, Kondo M. Comparison of three methods of nutritional assessment in liver cirrhosis: subjective global assessment, traditional nutritional parameters, and body composition analysis. J Gastroenterol 41: 476–482, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Fisher B, Lee S, Fedor EJ, Levine M. Intestinal absorption and nitrogen balance following portacaval shunt. Ann Surg 167: 41–46, 1968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fujita S, Dreyer HC, Drummond MJ, Glynn EL, Cadenas JG, Yoshizawa F, Volpi E, Rasmussen BB. Nutrient signalling in the regulation of human muscle protein synthesis. J Physiol 582: 813–823, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Guo T, Jou W, Chanturiya T, Portas J, Gavrilova O, McPherron AC. Myostatin inhibition in muscle, but not adipose tissue, decreases fat mass and improves insulin sensitivity. PLos One 4: e4937, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Hamrick MW, Pennington C, Webb CN, Isales CM. Resistance to body fat gain in “double-muscled” mice fed a high-fat diet. Int J Obes (Lond) 30: 868–870, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kim HS, Liang L, Dean RG, Hausman DB, Hartzell DL, Baile CA. Inhibition of preadipocyte differentiation by myostatin treatment in 3T3–L1 cultures. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 281: 902–906, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lauterburg B, Bircher J. Defective renal handling of water in the rat with a portacaval shunt. Eur J Clin Invest 6: 439–444, 1976 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lee SJ, Lee YS, Zimmers TA, Soleimani A, Matzuk MM, Tsuchida K, Cohn RD, Barton ER. Regulation of muscle mass by follistatin and activins. Mol Endocrinol 24: 1998–2008, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Lin J, Arnold HB, la-Fera MA, Azain MJ, Hartzell DL, Baile CA. Myostatin knockout in mice increases myogenesis and decreases adipogenesis. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 291: 701–706, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Machida S, Booth FW. Insulin-like growth factor 1 and muscle growth: implication for satellite cell proliferation. Proc Nutr Soc 63: 337–340, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Muller MJ, Bottcher J, Selberg O, Weselmann S, Boker KH, Schwarze M, von zur MA, Manns MP. Hypermetabolism in clinically stable patients with liver cirrhosis. Am J Clin Nutr 69: 1194–1201, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Nakatani M, Kokubo M, Ohsawa Y, Sunada Y, Tsuchida K. Follistatin-derived peptide expression in muscle decreases adipose tissue mass and prevents hepatic steatosis. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 300: E543–E553, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Nishida M, Funahashi T, Shimomura I. Pathophysiological significance of adiponectin. Med Mol Morphol 40: 55–67, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Pantzar N, Bergqvist PB, Bugge M, Olaison G, Lundin S, Jeppsson B, Westrom B, Bengtsson F. Small intestinal absorption of polyethylene glycol 400 to 1,000 in the portacaval shunted rat. Hepatology 21: 1167–1173, 1995 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pector JC, Winand J, Verbeustel S, Hebbelinck M, Christophe J. Effects of portacaval diversion on lipid metabolism in rat adipose tissue. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab Gastrointest Physiol 234: E759–E783, 1978 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Penicaud L, Cousin B, Leloup C, Lorsignol A, Casteilla L. The autonomic nervous system, adipose tissue plasticity, and energy balance. Nutrition 16: 903–908, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pitts GC, Ushakov AS, Pace N, Smith AH, Rahlmann DF, Smirnova TA. Effects of weightlessness on body composition in the rat. Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 244: R332–R337, 1983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Plauth M, Schutz ET. Cachexia in liver cirrhosis. Int J Cardiol 85: 83–87, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Rebbapragada A, Benchabane H, Wrana JL, Celeste AJ, Attisano L. Myostatin signals through a transforming growth factor beta-like signaling pathway to block adipogenesis. Mol Cell Biol 23: 7230–7242, 2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Reisz-Porszasz S, Bhasin S, Artaza JN, Shen R, Sinha-Hikim I, Hogue A, Fielder TJ, Gonzalez-Cadavid NF. Lower skeletal muscle mass in male transgenic mice with muscle-specific overexpression of myostatin. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 285: E876–E888, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Robin JP, Heitz A, Le MY, Lignon J. Physical limitations of the TOBEC method: accuracy and long-term stability. Physiol Behav 75: 105–118, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Rodgers BD, Garikipati DK. Clinical, agricultural, and evolutionary biology of myostatin: a comparative review. Endocr Rev 29: 513–534, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Squibb RL, Aguirre A, Braham JE, Scrimshaw NS, Brigeforth E. Effect of age, sex and feeding regimen on fat digestibility in individual rats as determined by a rapid extraction procedure. J Nutr 64: 625–634, 1958 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Swarbrick MM, Havel PJ. Physiological, pharmacological, and nutritional regulation of circulating adiponectin concentrations in humans. Metab Syndr Relat Disord 6: 87–102, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Thornton-Jones ZD, Kennett GA, Benwell KR, Revell DF, Misra A, Sellwood DM, Vickers SP, Clifton PG. The cannabinoid CB1 receptor inverse agonist, rimonabant, modifies body weight and adiponectin function in diet-induced obese rats as a consequence of reduced food intake. Pharmacol Biochem Behav 84: 353–359, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Wicklmayr M, Rett K, Schwiegelshohn B, Wolfram G, Hailer S, Dietze G. Inhibition of muscular amino acid release by lipid infusion in man. Eur J Clin Invest 17: 301–305, 1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Zimmers TA, Davies MV, Koniaris LG, Haynes P, Esquela AF, Tomkinson KN, McPherron AC, Wolfman NM, Lee SJ. Induction of cachexia in mice by systemically administered myostatin. Science 296: 1486–1488, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]