Background: Fungal sterol regulatory element-binding protein cleavage requires the Golgi Dsc E3 ligase complex of undefined structure.

Results: Biochemical and bioinformatic analyses provide insight into Dsc E3 ligase architecture, indicating that Dsc2 is a ubiquitin-binding rhomboid pseudoprotease.

Conclusion: The five Dsc E3 ligase subunits form subcomplexes and display defined connectivity.

Significance: Multisubunit E3 ligase complexes in the ER and Golgi exhibit conserved subunit organization.

Keywords: ER-associated Degradation, Hypoxia, Transcription Factors, Ubiquitin, Ubiquitin Ligase, SREBP

Abstract

The membrane-bound sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP) transcription factors regulate lipogenesis in mammalian cells and are activated through sequential cleavage by the Golgi-localized Site-1 and Site-2 proteases. The mechanism of fission yeast SREBP cleavage is less well defined and, in contrast, requires the Golgi-localized Dsc E3 ligase complex. The Dsc E3 ligase consists of five integral membrane subunits, Dsc1 through Dsc5, and resembles membrane E3 ligases that function in endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation. Using immunoprecipitation assays and blue native electrophoresis, we determined the subunit architecture for the complex of Dsc1 through Dsc5, showing that the Dsc proteins form subcomplexes and display defined connectivity. Dsc2 is a rhomboid pseudoprotease family member homologous to mammalian UBAC2 and a central component of the Dsc E3 ligase. We identified conservation in the architecture of the Dsc E3 ligase and the multisubunit E3 ligase gp78 in mammals. Specifically, Dsc1-Dsc2-Dsc5 forms a complex resembling gp78-UBAC2-UBXD8. Further characterization of Dsc2 revealed that its C-terminal UBA domain can bind to ubiquitin chains but that the Dsc2 UBA domain is not essential for yeast SREBP cleavage. Based on the ability of rhomboid superfamily members to bind transmembrane proteins, we speculate that Dsc2 functions in SREBP recognition and binding. Homologs of Dsc1 through Dsc4 are required for SREBP cleavage and virulence in the human opportunistic pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. Thus, these studies advance our organizational understanding of multisubunit E3 ligases involved in endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation and fungal pathogenesis.

Introduction

Sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs)2 are basic helix-loop-helix leucine zipper transcription factors and central regulators of lipid synthesis in mammalian cells (1, 2). SREBPs are synthesized as endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-bound proteins with two transmembrane helices and cytosolic N- and C-terminal domains. In cholesterol-rich cells, SREBP cleavage-activating protein (SCAP) binds to SREBP and retains it in the ER. In cholesterol-depleted cells, SCAP transports SREBP to the Golgi where SREBP undergoes proteolytic cleavage to release its N-terminal transcription factor domain (2). The Golgi Site-1 and Site-2 proteases act sequentially to cleave SREBP in mammalian cells, resulting in activation of genes required for cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis.

The SREBP pathway is conserved in the fission yeast Schizosaccharomyces pombe with two key differences. First, low oxygen triggers cleavage of yeast SREBP named Sre1 that controls genes required for hypoxic growth (3–5). Second, homologs of the Site-1 and Site-2 proteases have not been identified in fission yeast. A recent genetic screen and genetic selection in our laboratory identified six dsc (defective for SREBP cleavage) genes that are required for Sre1 cleavage (6, 7). dsc1–5 code for integral membrane proteins that form a complex in the Golgi, and dsc6 codes for Cdc48, a highly conserved AAA-ATPase (called p97/VCP in mammals) with segregase activity that functions in the ubiquitin-proteasome pathway (7, 8). Dsc1 is the fission yeast homolog of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Tul1, a Golgi membrane RING (really interesting new gene) E3 ligase (9). RING E3 ligases act by bringing ubiquitin conjugating enzymes (E2) to the substrate, thus facilitating ubiquitination. Partial truncation of the Dsc1 RING domain or mutation of a conserved RING domain residue makes Dsc1 non-functional for Sre1 cleavage (7). Consistent with this, the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Ubc4 is also required for Sre1 cleavage (7). Dsc2, Dsc3, and Dsc4 are largely uncharacterized multi-span transmembrane proteins. Dsc2 has a predicted C-terminal ubiquitin-associated (UBA) domain and Dsc3 has a predicted N-terminal ubiquitin-like domain (7). Dsc5 is homologous to S. cerevisiae Ubx2 and Ubx3 and contains a C-terminal ubiquitin regulatory X (UBX) domain (10). Similar to other UBX proteins (11), Dsc5 binds Cdc48, recruiting Cdc48 to the Dsc E3 ligase (6). The way in which the multiple subunits of this E3 ligase assemble is unknown.

ER-associated degradation (ERAD) is a protein quality control pathway in which misfolded ER lumenal and membrane proteins are targeted to the proteasome for degradation (12, 13). Previously, we noted that subunits of the Golgi Dsc E3 ligase show sequence similarity to components of both the Hrd1 and gp78 membrane E3 ligases involved in ERAD (7, 12, 13): Dsc1 is a multi-span transmembrane RING E3 ligase such as Hrd1 and gp78; Dsc2 resembles Derlin family proteins; Dsc3 shows homology to Herp/Usa1; and Dsc5 shows homology to Ubx2 (6). Recent work from Kopito and co-workers (14) extensively mapped protein-protein interactions among subunits of the Hrd1 and gp78 E3 ligases and identified the UBA domain-containing protein UBAC2 as a functional subunit of the gp78 E3 ligase. UBAC2 is an ER rhomboid pseudoprotease that binds UBXD8 and regulates UBXD8 localization between the ER and lipid droplets (15). Despite our detailed knowledge of ERAD machinery components, much remains to be learned about how these multisubunit complexes are organized and the requirements for their assembly.

In this study, we performed a comprehensive analysis of the subunit organization of the Dsc E3 ligase in fission yeast. We used co-immunoprecipitation and blue native (BN)-PAGE to determine the interactions among the Dsc proteins. The data suggest that the Dsc E3 ligase assembles in hierarchical fashion and that the components form subcomplexes with one another. Characterization of Dsc2 identified this protein as a member of the UBAC2 family of rhomboid pseudoproteases that contain a C-terminal UBA domain (14). The UBA domain of Dsc2 is capable of binding poly-ubiquitin chains and Lys63-linked di-ubiquitin in vitro. Interestingly, the UBA domain of Dsc2 was not essential for Sre1 cleavage, suggesting that Dsc E3 ligase may have additional cellular functions. In the human fungal pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus, hypoxic adaptation and virulence require SREBP and homologs of Dsc1 through Dsc4 (16, 17). Thus, our findings are relevant to mechanisms of fungal pathogenesis. Given similarities between the Dsc and ERAD E3 ligase complexes, this study also provides a framework for understanding the organization of other E3 ligase complexes.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

General materials were obtained from Fisher and Sigma with the following exceptions: yeast extract, peptone, and agar from BD Biosciences; oligonucleotides were from Integrated DNA Technologies; digitonin were from EMD Chemicals; dithiobis[succinimidyl propionate] and EZ-link plus activated peroxidase were from Thermo Scientific; peptides N-glycosidase (PNGase) F and prestained protein standards were from New England Biolabs; isopropyl-1-thio-β-galactopyranoside and NativeMark unstained protein standard were from Invitrogen; Native PAGE materials were from Novex; MagneGST was from Promega; alkaline phosphatase, Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor, mouse anti-GFP antibody, and anti-HA monoclonal 12CA5 IgG were from Roche Applied Science; mouse anti-ubiquitin monoclonal P4D1 IgG and anti-Myc monoclonal 9E10 IgG were from Santa Cruz Biotechnology; horseradish peroxidase-conjugated, affinity-purified donkey anti-rabbit and anti-mouse IgG were from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories; protein A-agarose was from Repligen; and In vivo2 400 Hypoxic Work station was from Biotrace.

Yeast Strains and Culture

S. pombe cells were grown to log phase at 30 °C in YES medium (5 g/liter yeast extract plus 30 g/liter glucose and supplements, 225 mg/liter each of uracil, adenine, leucine, histidine, and lysine) as reported (16). Strains used in this study are described in supplemental Table 1. Dr. Colin Gordon (Medical Research Council of UK) kindly gifted the mts3–1 strain. Standard techniques were employed to generate epitope-tagged versions of proteins and delete sequences coding for amino acids 298–372 in dsc2. Random spore mating generated dsc1–3xHA, dsc4–13xMyc, and dsc5–3xHA strains in dsc deletion backgrounds.

For Sre1 cleavage assays, S. pombe strains were grown in YES medium. After centrifugation to sediment the cells, the oxygenated medium was removed using aspiration. Resuspension in deoxygenated YES medium was completed inside the In vivo2 400 Hypoxic Work station. The chamber maintains anoxia, using a combination of hydrogen and nitrogen gases in the presence of palladium catalyst. Medium was equilibrated for at least 24 h before use. Cells were grown to exponential phase with agitation at a temperature of 30 °C for 6 h and then quantified by optical density. Cells (2 × 107) were harvested and processed for protein extraction as described previously (3). To isolate microsomes, pelleted cells (5 × 107) were resuspended in 50 μl of B88 buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.2, 150 mm KOAc, 5 mm MgOAc, and 250 mm sorbitol) plus protease inhibitors (leupeptin (10 μg/ml), pepstatin A (5 μg/ml), and PMSF (1 mm)) and subjected to a 10-min Vortex Genie cycle with glass beads. The supernatant of an initial clearing centrifugation at 500 × g (5 min at 4 °C) was again centrifuged at 20,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. The pellet, containing membrane proteins, was resuspended in 50 μl of SDS lysis buffer (10 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 100 mm NaCl, 1% SDS, 1 mm EDTA, and 1 mm EGTA) plus protease inhibitors. Membrane samples were diluted with an equal volume of urea lysis buffer (50 mm Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, 6 m urea) and heated at 37 °C for 30 min to minimize protein aggregation. Immunoblotting was utilized for protein analysis. Where indicated, microsomal protein was deglycosylated by treatment with PNGase F according to the manufacturer's instructions (New England Biolabs).

Antibody Preparation

Rabbit polyclonal antisera generated to Sre1 (aa 1–240), Sre2 (aa 1–426), Dsc1 (aa 20–319), Dsc2 (aa 250–372), Dsc3 (aa 1–190), Dsc4 (aa 150–281), and Dsc5 (aa 251–427) were described previously (6, 7). Antiserum to Cdc48 was a gift from R. Hartmann-Petersen (University of Copenhagen) (18). HRP conjugation of Dsc antisera was prepared using the Thermo Scientific (Pierce) EZ-link Plus activated peroxidase kit, according to the manufacturer's instructions.

Co-immunoprecipitation

Pulldown assays were done as described previously (6). Briefly, 5 × 108 log phase S. pombe cells were washed in PBS (1 mm KH2PO4, 3 mm Na2HPO4·7H2O, pH 7.4, 155 mm NaCl) and subjected to glass bead lysis (0.5 mm, Sigma) in digitonin lysis buffer (50 mm HEPES, pH 6.8, 1% (w/v) digitonin, 50 mm KOAc, 2 mm MgOAc, 1 mm CaCl2, 200 mm sorbitol, 1 mm NaF, 0.3 mm Na3VO4), supplemented with protease inhibitors (leupeptin (10 μg/ml), pepstatin A (5 μg/ml), PMSF (1 mm), and the Complete EDTA-free protease inhibitor). Insoluble cellular debris was pelleted at 100,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C. A total of 1.5 mg of protein from the lysate in 0.7 ml was incubated with 1 μg of anti-Myc 9E10 IgG, 1 μg of anti-HA IgG, or 5 μl of anti-Dsc serum for 15 min at 4 °C prior to mutation with 40 μl of protein A beads for 16 h at 4 °C. After three washes with 1 ml of digitonin lysis buffer, immunopurified proteins were eluted by boiling in SDS-PAGE loading buffer. The precipitates were analyzed by immunoblotting with Dsc antisera or HRP-conjugated versions of the Dsc antisera.

The co-immunoprecipitation protocol used to study the interaction between Sre2 and the Dsc complex was performed, as described above, with modifications. Strains carrying a temperature-sensitive allele of the E2 ubiquitin conjugating enzyme Ubc4 (ubc4-P61S) were grown at 23 °C to reach exponential phase and then shifted to non-permissive 36 °C for 2 h (7). The cells were pelleted, washed, and resuspended in PBS. In vivo cross-linking of 5 × 108 cells was achieved with 2 mm dithiobis[succinimidyl propionate] for 30 min at 36 °C, followed by quenching with 20 mm Tris (pH 8.0). Cells were washed and lysed with glass beads in Nonidet P-40 lysis buffer (50 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 100 mm NaCl, 1.5 mm MgCl2, and 1% Nonidet P-40) supplemented with protease inhibitors. Cellular debris was removed by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 2 min. One milligram of total lysate was incubated with 5 μl of anti-Sre2 serum, and isolated proteins were detected using HRP-conjugated Dsc antisera.

Blue Native PAGE

Exponentially growing yeast cells (25 × 107) were pelleted by centrifugation, resuspended in buffer A (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 100 mm NaCl, 20 mm imidazole, 10% glycerol, and 2 mm 6-aminocaproic acid), and lysed by vortexing with glass beads. Lysates were pre-cleared by centrifugation at 500 × g for 5 min, and the supernatant was subjected to 20,000 × g spin for 20 min to pellet membranes. The pellet was resuspended in buffer A containing 1% digitonin and nutated for 1 h at 4 °C, followed by centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 20 min. The supernatant was collected and used as digitonin-solubilized membranes. Ten micrograms of digitonin-solubilized membranes were mixed with 10X sample buffer [0.5 M 6-aminocaproic acid, 100 mm BisTris, pH 7.0 and 5% G-250] and loaded onto a 3–12% Native-PAGE (BisTris). Electrophoresis was carried out, using cathode buffer [50 mm Tricine, 15 mm BisTris, pH 7.0], containing 0.02% G-250, and anode buffer [50 mm BisTris, pH 7.0]. Separated proteins were transferred to a PVDF membrane and immunoblotting was performed, using different anti-Dsc sera. For size determination, NativeMark unstained protein standards supplemented with 1% digitonin and 1X sample buffer were used. Sample replicates were analyzed side-by-side by Blue Native-PAGE. Following transfer, membranes were probed with anti-Dsc antibodies. Membranes were stripped by incubating at 50 °C for 30 min in buffer containing 62.5 mm Tris, pH 6.8, 2% SDS, and 1% 2-mercaptoethanol and reprobed with different anti-Dsc antibodies to determine co-migration of subcomplexes.

In Vitro Binding Assay

In vitro binding of recombinant proteins to ubiquitin in yeast lysates was performed as described with the following modifications (6). GST was expressed using pGEX-KG in DH5α Escherichia coli cells induced by 0.6 mm isopropyl-1-thio-β-galactopyranoside and purified using glutathione-Sepharose beads (GE Healthcare). The GST-UBAC2UBA construct, containing the UBA domain of Homo sapiens UBAC2 (aa 293–344), was a generous gift from J. C. Christianson (University of Oxford). The homologous C-terminal sequence of Dsc2 (aa 298–372) was cloned into pGEX-KG and named GST-Dsc2UBA. E. coli cells expressing these GST fusion proteins were induced as above, lysed by sonication in PBS plus protease inhibitors, incubated for 90 min with 1% (w/v) Triton X-100, and cleared by centrifugation at 15,000 × g for 20 min at 4 °C.

For binding assays, MagneGST beads (25 μl) were blocked in PBS containing 1% bovine serum albumin and then incubated with either GST-UBA lysate (1 mg) or purified GST (50 μg) in 0.5 ml of PBS for 1 h at 4 °C. Beads were washed three times with PBS and once with binding buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.2, 150 mm KOAc, 5 mm MgOAc, 250 mm sorbitol, 0.2% Nonidet P-40, protease inhibitors) and incubated with S. pombe mts3–1 cytosol (0.7 mg) in 0.1 ml of binding buffer for 30 min at 4 °C. After three washes with binding buffer, bound proteins were eluted by boiling in SDS-PAGE loading buffer, separated by SDS-PAGE, and evaluated by Western blotting with anti-ubiquitin (P4D1) antibody as described previously (19). Samples were also probed with anti-GST (HRP) antibody. S. pombe cytosol from mts3–1 cells was prepared by shifting cells that were grown overnight at 25 °C to non-permissive temperature (36 °C) for 4 h and lysing them with glass beads in B88 buffer plus protease inhibitors. The lysate was centrifuged at 100,000 × g for 10 min at 4 °C, and the supernatant was used as cytosol. For reactions with purified ubiquitin, poly-ubiquitin chains were generated as described previously (20). GST-UBA lysates or purified GST was immobilized on MagneGST beads, incubated with 10 μm ubiquitin in 250 μl B88 buffer plus 0.2% Nonidet P-40 and protease inhibitors (leupeptin (10 μg/ml), pepstatin A (5 μg/ml), and PMSF (1 mm)) for 30 min at 4 °C, washed with B88 buffer plus 0.2% Nonidet P-40 and protease inhibitors, and eluted by pipetting in SDS lysis buffer. Protein samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE using gradient gels and Western blotting.

RESULTS

Proper N-linked Glycosylation of Dsc1 Requires dsc2, dsc3, and dsc4

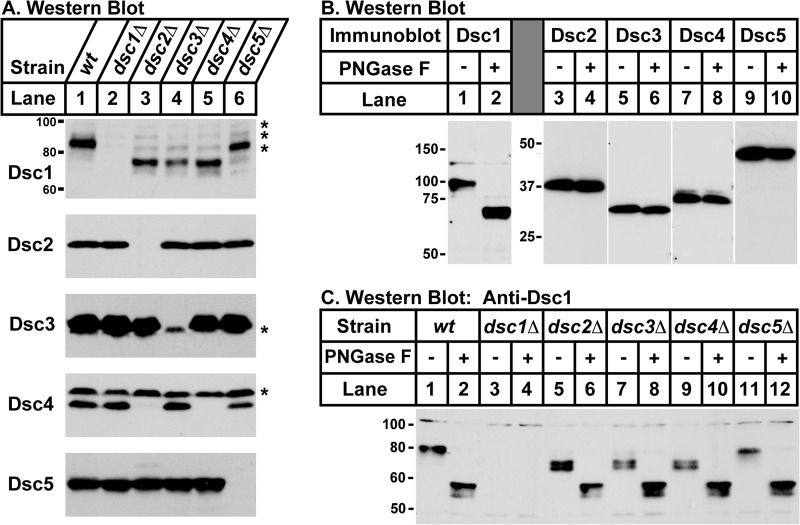

The Dsc E3 ligase contains five subunits (Dsc1 through Dsc5) that form a stable membrane protein complex in the Golgi (6, 7). To begin to probe the organization of the Dsc E3 ligase complex, we examined Dsc protein expression in the absence of individual complex subunits. We generated S. pombe strains lacking a single Dsc subunit and assayed levels of the other Dsc proteins in microsomal fractions by immunoblot. Dsc protein expression was unaltered in dsc mutant strains with two exceptions (Fig. 1A). First, Dsc4 was absent in dsc2Δ cells (Fig. 1A, lane 3, fourth panel). Wild-type and dsc2Δ cells showed equivalent expression of dsc4 mRNA and treatment of cells with proteasome inhibitor restored Dsc4 protein (data not shown), suggesting that Dsc4 stability requires Dsc2. Second, the mobility of Dsc1 increased in dsc2Δ, dsc3Δ, and dsc4Δ cells but not dsc5Δ cells (Fig. 1A, top panel). To determine whether this mobility difference was due to altered post-translational modification, we tested whether the Dsc proteins were glycosylated or phosphorylated. Treatment of microsomal proteins with the glycosidase PNGase F increased the mobility of Dsc1 (Fig. 1B), indicating that Dsc1 contained N-linked glycosylation. The mobility of Dsc2, Dsc3, Dsc4, and Dsc5 was not altered by glycosidase treatment. Consistent with this finding, the first luminal segment of Dsc1 contains five potential N-linked glycosylation sites (Asn52, Asn92, Asn115, Asn158, and Asn220), and N-linked glycosylation at three sites (Asn52, Asn115, and Asn220) has been validated by mass spectrometry (21). The mobility of Dsc proteins on SDS-PAGE was not altered by phosphatase treatment, indicating that the change in Dsc1 mobility was not due to altered phosphorylation (data not shown). Dsc1 mobility was identical in all strains following PNGase F treatment (Fig. 1C), demonstrating that the difference observed in dsc2Δ, dsc3Δ, and dsc4Δ strains was due to altered N-linked glycosylation of Dsc1. The interdependence of Dsc proteins for expression and N-linked glycosylation indicated that specific protein-protein interactions underlie Dsc E3 ligase assembly.

FIGURE 1.

Dsc1 N-linked glycosylation requires Dsc2, Dsc3, and Dsc4. A, microsomes isolated from wild-type (lane 1) and deletion mutants (lanes 2–6) were subjected to immunoblotting with Dsc protein antisera. Asterisks denote nonspecific proteins detected by antisera. B, Western blot of wild-type microsomes (20 μg) incubated in the absence (−) or presence (+) of PNGase F probed with indicated Dsc antiserum. C, microsomes (20 μg) from wild-type (lanes 1 and 2) or indicated deletion strains (lanes 3–12) were incubated in the absence (−) or presence (+) of PNGase F, and the products were analyzed by Western blot using Dsc1 antiserum. Experiments were performed a minimum of two times. Representative results are shown.

Dsc E3 Ligase Subunits Have Defined Connectivity

To explore the connectivity among the Dsc E3 ligase subunits, we performed co-immunoprecipitation assays in wild-type and dsc mutant cells. Digitonin-solubilized membranes were used for immunoprecipitation with Dsc antisera. In cases where the antisera did not function for immunoprecipitation, strains expressing functional epitope-tagged Dsc proteins were used. For completeness, we included the cdc48-3 (A586V) strain. Cdc48 binds to the Dsc E3 ligase complex through the UBX domain of Dsc5 and is required for Sre1 cleavage under low oxygen (6).

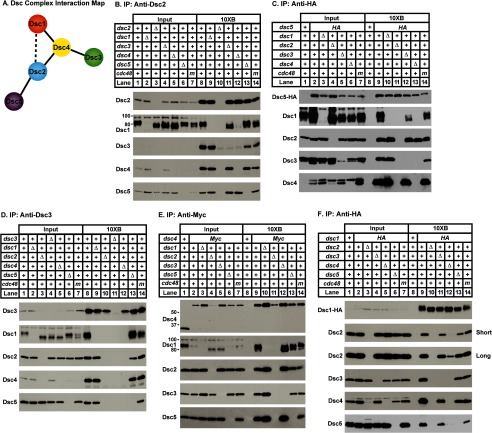

Co-immunoprecipitation in a mild detergent showed a definitive pattern for binding within the Dsc E3 ligase complex (Fig. 2A). When Dsc2 was precipitated, the remaining subunits co-purified in wild-type, dsc1Δ, dsc3Δ, dsc5Δ, and cdc48-3 cells (Fig. 2B, lanes 8–14). In the dsc4Δ strain, recovery of Dsc1 and Dsc3 was lost (Fig. 2B, lane 12), indicating that the binding of Dsc1 and Dsc3 to Dsc2 requires Dsc4. When Dsc5 was precipitated, the remaining subunits co-purified in wild-type, dsc1Δ, dsc3Δ, and cdc48-3 cells (Fig. 2C, lanes 9, 10, 12, and 14). Deletion of dsc2 disrupted Dsc5 binding to all other Dsc subunits, indicating that Dsc5 interacts with the complex via Dsc2 (Fig. 2C, lane 11). Deletion of dsc4 disrupted Dsc5 binding to Dsc1 and Dsc3 (Fig. 2C, lane 13). Therefore, Dsc5 and Dsc2 form a subcomplex, and Dsc2 connects Dsc5 to Dsc4.

FIGURE 2.

Dsc E3 ligase subunits have defined connectivity. A, model illustrating the results from co-immunoprecipitation experiments in B–F. Complexes observed in wild-type cells and deletion mutants are indicated by lines between subunits. Connections do not denote direct protein-protein interactions. Solid lines represent major interactions, and a dashed line represents a minor interaction between Dsc2 and Dsc1. B, digitonin-solubilized extracts from indicated wild-type and mutant strains were immunoprecipitated with anti-Dsc2 antibody and equal amounts of total (lanes 1–7) and 10× bound fractions (10xB; lanes 8–14) were analyzed for binding of the other Dsc proteins, using HRP-conjugated Dsc antisera. +, wild-type allele; Δ, deletion; m, cdc48-3. C, indicated wild-type and dsc5–3xHA strains were used for co-immunoprecipitation experiments with anti-HA antibody as in B. D, indicated wild-type and mutant strains were used for co-immunoprecipitation experiments with anti-Dsc3 antiserum as above. E, indicated wild-type and dsc4–13xMyc strains were used for co-immunoprecipitation experiments with anti-Myc antibody as above. F, indicated wild-type and dsc1–3xHA strains were used for co-immunoprecipitation experiments with anti-HA antibody as above. Both short and long exposure times are displayed for the anti-Dsc2 immunoblot. Experiments were performed a minimum of three times. Representative results are shown.

In a Dsc3 co-immunoprecipitation, the remaining subunits co-purified in wild-type, dsc1Δ, dsc5Δ, and cdc48-3 cells (Fig. 2D, lanes 8, 9, 13, and 14). Deletion of dsc4 disrupted Dsc3 binding to all other Dsc subunits, an indication that Dsc3 interacts with the complex via Dsc4 (Fig. 2D, lane 12). Likewise, deletion of dsc2 disrupted Dsc3 binding to the complex, consistent with the loss of Dsc4 in dsc2Δ cells (Fig. 1A). When Dsc4 was precipitated, the remaining subunits co-purified in wild-type, dsc1Δ, dsc3Δ, dsc5Δ, and cdc48-3 cells (Fig. 2E, lanes 9, 10, 12, 13, and 14). Deletion of dsc2 disrupted Dsc4 binding to all other Dsc subunits, possibly due to reduced levels of Dsc4-Myc in this strain (Fig. 2E, lane 4). Lastly, when Dsc1 was precipitated, the remaining subunits co-purified in wild-type, dsc3Δ, dsc5Δ, and cdc48-3 cells (Fig. 2F, lanes 9, 11, 13, and 14). Deletion of dsc4 disrupted Dsc1 binding to all other Dsc subunits, indicating that Dsc1 interaction with the complex requires Dsc4 (Fig. 2F, lane 12). However, longer exposure times revealed a weak, Dsc4-independent interaction between Dsc1 and Dsc2 (Fig. 2F, lane 12). Deletion of dsc2 also disrupted Dsc1 binding to all other Dsc subunits, possibly due to low levels of Dsc4 in this strain (Fig. 2F, lane 3). Collectively, these protein-protein interaction data support a model in which Dsc2-Dsc4 form a core complex to which the peripheral subunits Dsc1, Dsc3, and Dsc5 bind (Fig. 2A). Dsc1 connects to the complex via Dsc4 with some contribution from Dsc2; Dsc3 connects via Dsc4; and Dsc5 connects via Dsc2. Although this is the simplest interpretation of the results, in the absence of in vitro binding studies, we cannot exclude the possibility that Dsc4 is required for Dsc2 direct binding to Dsc3.

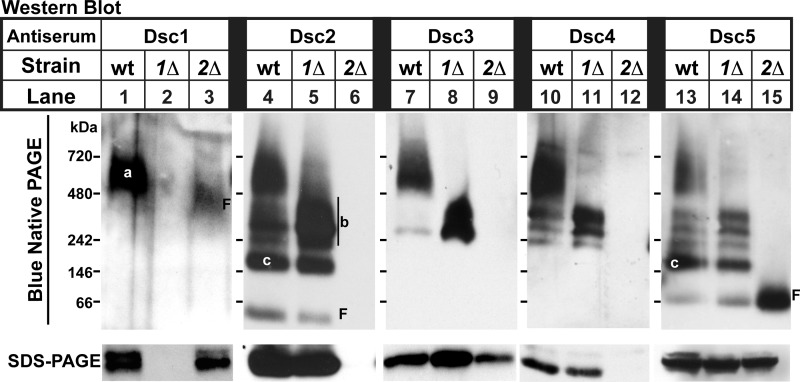

Dsc Proteins Form Subcomplexes

Next, we used BN-PAGE combined with Western blotting to further survey complex connectivity and validate Dsc subunit interactions. Analysis of digitonin-solubilized membranes revealed multiple complexes of Dsc proteins in wild-type cells (Fig. 3, lanes 4, 7, 10, and 13). BN-PAGE studies of these complexes in dsc mutants together with the co-immunoprecipitation results from Fig. 2 allowed identification of individual Dsc subcomplexes. Complex (a) contained each of the five Dsc subunits and represented the complete Dsc E3 ligase complex (Fig. 3, lane 1). Deletion of dsc2 resulted in a faster migrating Dsc1 that lacked other Dsc subunits (Fig. 3, lanes 3, 6, 9, 12, and 15). Consistent with this, Dsc1 failed to bind other Dsc subunits in dsc2Δ cells in the co-immunoprecipitation assay (Fig. 2F, lane 10), possibly due to the absence of Dsc4 in dsc2Δ cells (Fig. 3, lane 12). Assuming that no other Dsc subunits exist, Dsc1 is likely a homo-oligomer in dsc2Δ cells given the high molecular mass of this complex (∼480 kDa) and the mass of Dsc1 on SDS-PAGE (∼85 kDa, Fig. 1A).

FIGURE 3.

Dsc proteins form multiple subcomplexes. Digitonin-solubilized membranes (15 μg for Dsc1 blot and 10 μg for Dsc2-Dsc5 blots) from wild-type and indicated deletion strains were separated by blue native PAGE and analyzed, using anti-Dsc antisera (upper panel). Samples were subjected to blue native PAGE in triplicate and immunoblotted using anti-Dsc1, anti-Dsc2, and anti-Dsc3 antibodies. Membranes probed with anti-Dsc2 and anti-Dsc3 were stripped and reprobed with anti-Dsc5 and anti-Dsc4, respectively. Native molecular weights are represented by dashes in each panel. Bands corresponding to subcomplexes are labeled a–c, and F denotes free protein. SDS-PAGE analysis was performed in parallel, using an aliquot of each sample (lower panel). Experiments were performed a minimum of four times. Representative results are shown.

Dsc2 formed multiple complexes in wild-type cells (Fig. 3, lane 4). Deletion of dsc1 increased the abundance of Dsc2 complexes containing Dsc3, Dsc4, and Dsc5 (Fig. 3, lane 5, labeled b), consistent with the predicted complex organization (Fig. 2A). In addition, wild-type cells contained a Dsc2-Dsc5 complex (labeled c) (Fig. 3, lanes 4 and 13). Wild-type cells also contained small amounts of unincorporated, free Dsc2 and Dsc5 (Fig. 3, lanes 4 and 13). As expected, deletion of dsc2 prevented Dsc5 assembly with other Dsc subunits and resulted in the accumulation of free Dsc5 (Fig. 3, lane 15). Dsc3 was not detected in dsc2Δ cells by BN-PAGE despite its presence in the extract as judged by SDS-PAGE (Fig. 3A, lane 9, lower panel). Collectively, the BN-PAGE studies demonstrate the existence of Dsc subcomplexes and confirm the Dsc E3 ligase subunit organization obtained from the co-immunoprecipitation studies.

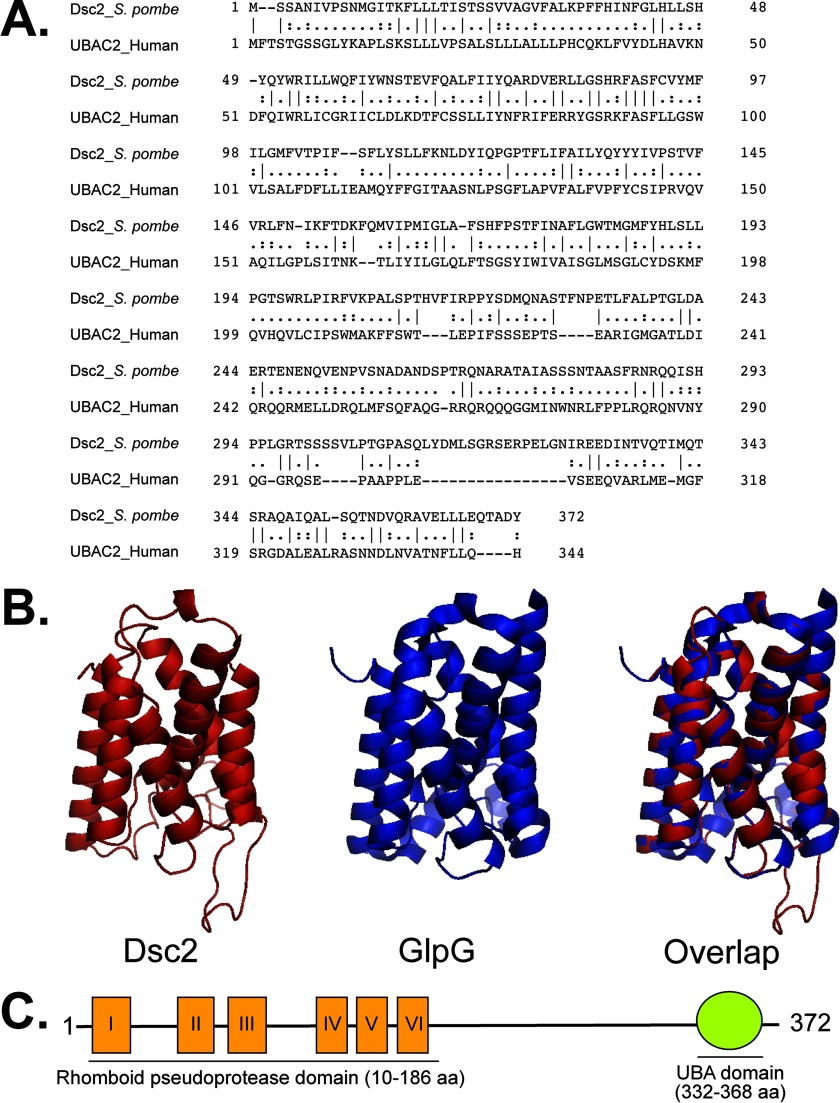

Dsc2 Is a Rhomboid Pseudoprotease

Our data indicated a central role for Dsc2 in the Dsc E3 ligase complex organization. Dsc2 has been localized to the Golgi (7) but is otherwise uncharacterized (7). A BLASTP search against the mammalian Refseq database revealed that Dsc2 is homologous to human UBAC2, a UBA domain-containing rhomboid pseudoprotease (Fig. 4A) (13, 14). As with UBAC2, computational analyses of Dsc2 structure revealed homology between Dsc2 and the prokaryotic rhomboid protease GlpG (Fig. 4B) (22, 23). Rhomboid proteases such as E. coli GlpG are multi-span serine proteases that mediate intramembrane proteolysis (24). However, Dsc2 lacks the Ser-His catalytic dyad required for intramembrane substrate proteolysis. Functions are emerging for a family of rhomboid pseudoproteases that lack catalytic activity, including UBAC2 and Derlin proteins that act in ER-associated degradation (14, 25, 26). Similar to UBAC2, Dsc2 contains six predicted transmembrane segments followed by a C-terminal UBA domain (Fig. 4C) (13, 14). Together, these data indicate that Dsc2 is a Golgi-localized rhomboid pseudoprotease with a predicted UBA domain.

FIGURE 4.

Dsc2 is a rhomboid pseudoprotease. A, pairwise alignment of S. pombe Dsc2 and human UBAC2 performed, using EMBOSS stretcher alignment program. The two proteins showed 20% identity and 38% similarity in primary sequence. B, homology modeling of Dsc2 was performed, using E. coli GlpG (Protein Data bank code 2XOV; A) and SWISS MODEL. Dsc2 has a rhomboid fold with six transmembrane helices. C, Dsc2 contains two distinct domains, an N-terminal rhomboid pseudoprotease domain, and a C-terminal UBA domain as predicted by the Phyre server and HHPRED (22, 23). Predicted transmembrane regions (yellow boxes) were assigned using the model in B.

Dsc2 UBA Domain Binds Ubiquitin

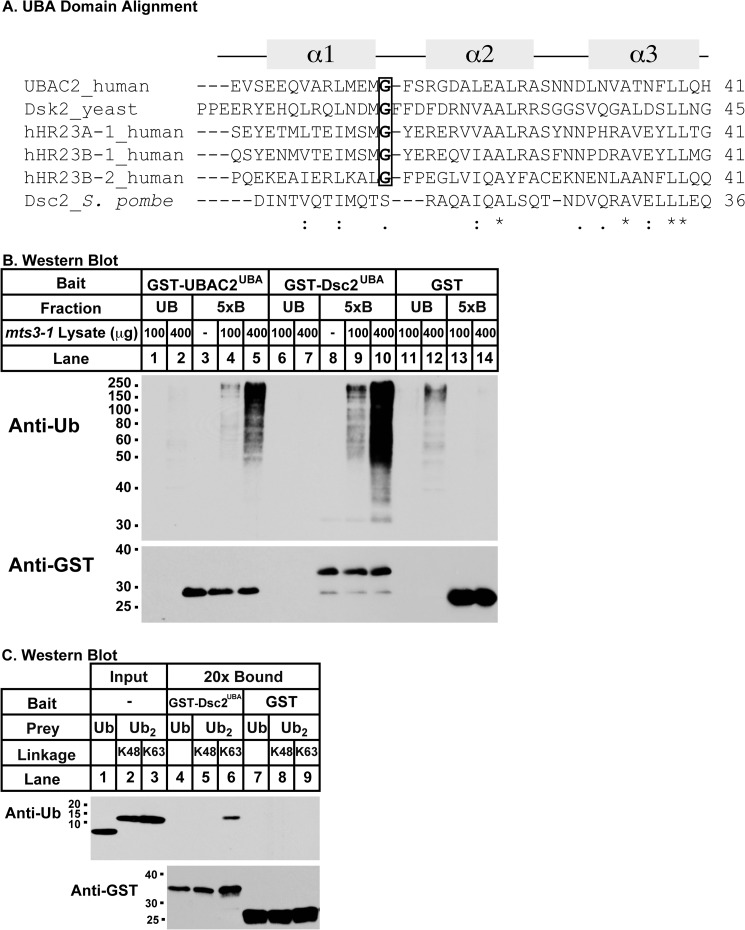

Bioinformatic analysis predicted that Dsc2 contains a UBA domain at its C terminus (Fig. 5A). UBA domains form a three-helix bundle with low sequence conservation (27), requiring validation of their ubiquitin binding properties. Based on the topology of homologous rhomboid pseudoproteases (25), the Dsc2 UBA domain is predicted to reside in the cytosol where it could bind ubiquitin. We used in vitro binding assays to evaluate the ability of Dsc2 UBA domain to bind ubiquitin.

FIGURE 5.

Dsc2 UBA domain binds ubiquitin. A, UBA domains from different proteins (human UBAC2, hHR23A-1, hHR23B-1, hHR23B-2, yeast Dsk2) were aligned with the putative UBA domain of S. pombe Dsc2, using Clustal W. Conserved residues are marked by an asterisk, and the helices of UBA domains are depicted as α1, α2, and α3. B, mts3-1 lysate enriched for poly-ubiquitinated proteins was used to evaluate ubiquitin (Ub) binding of GST-tagged UBA domains from Dsc2 (lanes 1–5) and UBAC2 (lanes 6–10) with GST alone as a negative control. Unbound fractions and 5× bound (5xB) fractions were immunoblotted with anti-ubiquitin P4D1 (upper panel) and anti-GST (lower panel) monoclonal antibodies. C, binding of GST-Dsc2UBA (lanes 4–6) and GST (lanes 7–9) to mono-ubiquitin, lysine 48-linked di-ubiquitin and lysine 63-linked di-ubiquitin. Input and 20× bound (20xB) fractions were analyzed by immunoblot using anti-ubiquitin P4D1 (upper panel) and anti-GST (lower panel) monoclonal antibodies. Experiments were performed a minimum of two times. Representative results are shown.

Recombinant GST-Dsc2UBA (aa 298–372) that included the UBA domain was purified from E. coli and assayed for binding to poly-ubiquitinated proteins using yeast lysate from mts3-1 cells. The temperature-sensitive mts3-1 strain contains a mutation in the 19 S proteasome cap such that growth at the non-permissive temperature blocks proteasome function, leading to accumulation of poly-ubiquitinated proteins (28). Purified GST-UBAC2UBA (aa 293–344) and GST served as positive and negative controls, respectively (14). Both Dsc2UBA and UBAC2UBA specifically bound poly-ubiquitinated proteins (Fig. 5B). To test whether Dsc2UBA binds ubiquitin directly, we assayed binding of GST- Dsc2UBA to purified mono-ubiquitin, Lys48-linked di-ubiquitin, and Lys63-linked di-ubiquitin. Under these conditions, Dsc2UBA bound to Lys63-linked di-ubiquitin chains but not to mono-ubiquitin or Lys48-linked di-ubiquitin chains (Fig. 5C). Collectively, these data demonstrate that Dsc2 (aa 293–372) contains a functional UBA domain capable of directly binding di-ubiquitin in vitro. Additional studies are required to investigate whether the Dsc2 UBA domain shows linkage specificity in ubiquitin chain binding.

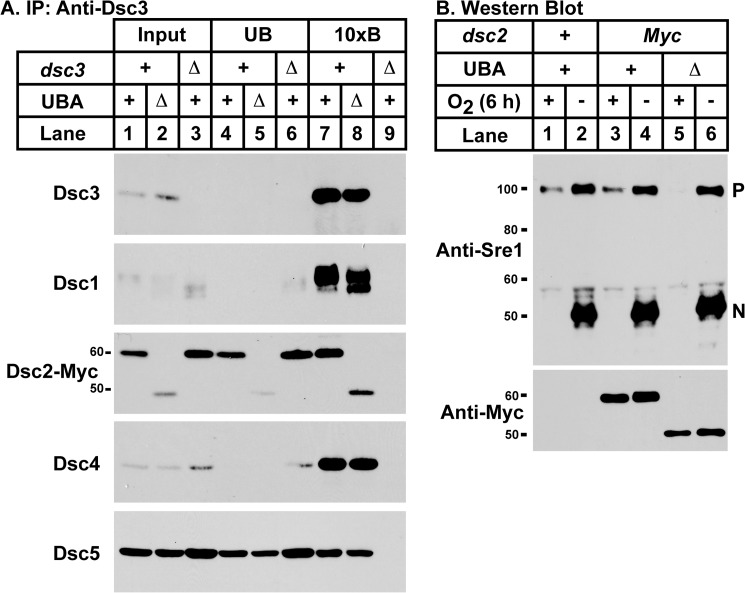

Dsc2 UBA Domain Is Dispensable for Complex Assembly and Sre1 Cleavage

To explore the function of the Dsc2 UBA domain, we tested whether Dsc E3 ligase complex formation was altered in cells expressing dsc2ΔUBA-13xMyc. Dsc2 antiserum was generated against a region that included the UBA domain, so dsc2–13xMyc strains were used to monitor Dsc2 expression. Dsc3 binding to the other Dsc subunits requires Dsc2 (Fig. 2D, lane 10), so a Dsc3 IP was used to independently assay the role of the UBA domain in complex assembly. Despite lower Dsc2–13xMyc protein expression in the dsc2ΔUBA-13xMyc strain, Dsc3 bound to Dsc1, Dsc2, Dsc4, and Dsc5 equally in dsc2–13xMyc and dsc2ΔUBA-13xMyc cells (Fig. 6A), indicating that complex assembly does not require the Dsc2 UBA domain. In addition, although Sre1 cleavage requires dsc2 (7), dsc2ΔUBA-13xMyc cells showed wild-type Sre1 cleavage activity after incubation under low oxygen for 6 h (Fig. 6B). These data indicate that the Dsc2 UBA domain is not essential for either Dsc E3 ligase complex assembly or Sre1 cleavage.

FIGURE 6.

Dsc complex assembly and Sre1 cleavage do not require the Dsc2 UBA domain. A, Dsc3 was immunopurified from digitonin-solubilized extracts of dsc2–13xMyc, dsc2ΔUBA-13xMyc, and dsc2–13xMyc dsc3Δ cells, using anti-Dsc3 antiserum. Equal amounts of input (lanes 1–4), unbound (lanes 5–8), and 10× bound (10xB; lanes 9–12) fractions were analyzed by immunoblot with anti-Myc IgG 9E10 monoclonal antibody or HRP-conjugated Dsc antisera. B, Western blot probed with affinity purified anti-Sre1 IgG of phosphatase-treated whole cell lysates from wild-type, dsc2–13xMyc, and dsc2ΔUBA-13xMyc cells grown for 6 h in the presence (+) or absence (−) of oxygen. P denotes full-length Sre1 protein, and N denotes the cleaved nuclear form. Experiments were performed a minimum of two times. Representative results are shown.

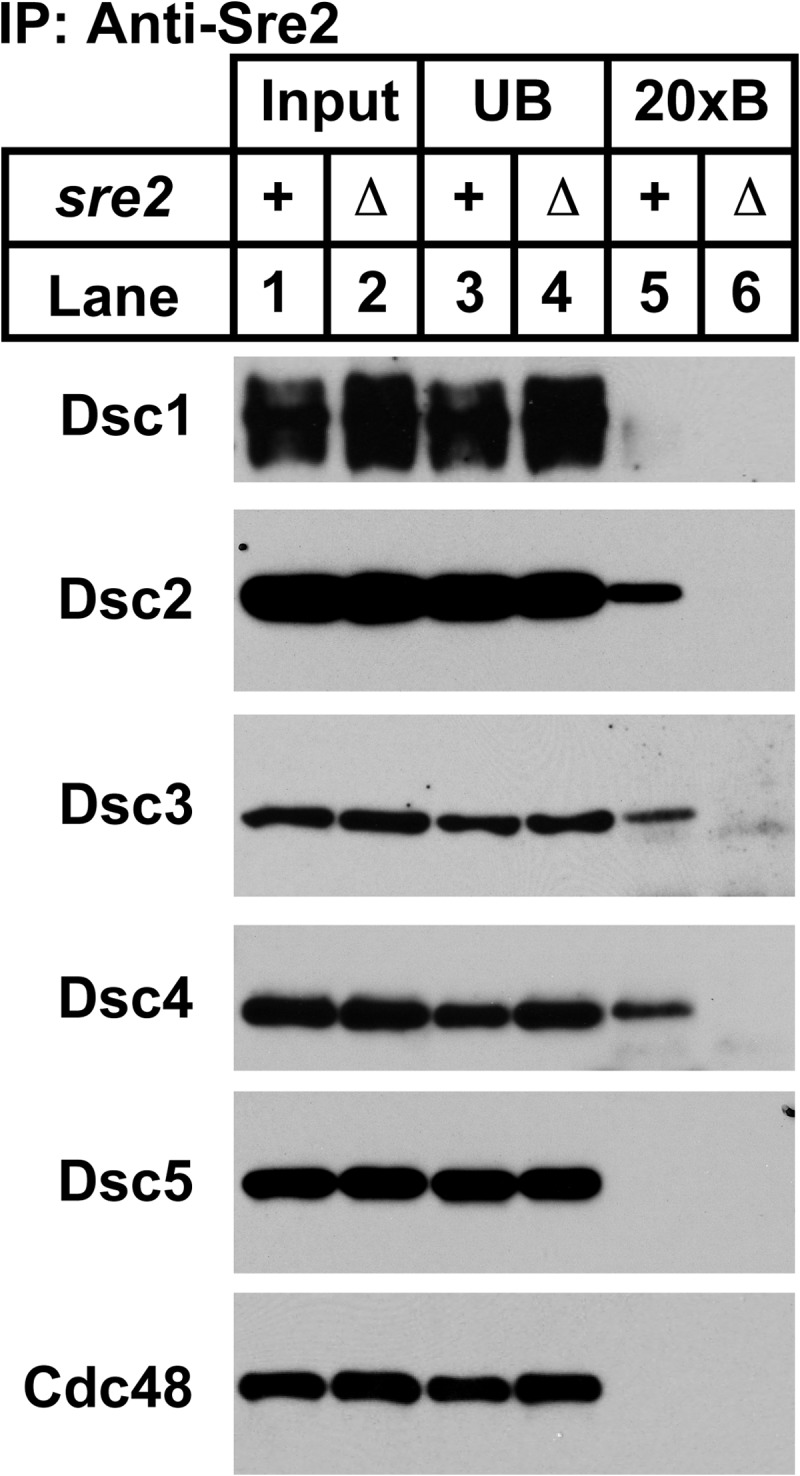

Sre2 Forms a Complex with Dsc2-Dsc4-Dsc3

Fission yeast contains a second SREBP transcription factor called Sre2 that is not regulated by oxygen (3). Similar to Sre1, cleavage of Sre2 requires the Dsc E3 ligase (7). Dsc2 binds Sre2 in cross-linker-treated cells, and detection of binding requires inhibition of Sre2 cleavage. Previously, we assayed binding between Dsc2 and Sre2 in a strain carrying a truncation of the Dsc1 C-terminal RING domain, but this approach prevented assessment of Sre2 binding to an intact Dsc E3 ligase complex (7). To investigate the Dsc subunits to which Sre2 binds, we alternatively inhibited Sre2 cleavage using a temperature-sensitive mutant of the E2 ubiquitin conjugating enzyme Ubc4 that is required for yeast SREBP cleavage (7). After a 2-h incubation at the non-permissive temperature, ubc4-P61S and ubc4-P61S sre2Δ cells were cross-linked, lysed, and immunoprecipitated with Sre2 antiserum prior to Dsc protein Western blotting. Sre2 interacted with Dsc2, Dsc3, and Dsc4, but not Dsc1, Dsc5, or Cdc48 (Fig. 7A, lane 5). The interaction was specific as no Dsc subunits were detected, using sre2Δ cells (Fig. 7A, lane 6). Based on our model for Dsc E3 ligase architecture (Fig. 2A), Sre2 interacts with a core module of Dsc2-Dsc4-Dsc3.

FIGURE 7.

Sre2 binds to Dsc2-Dsc3-Dsc4. Cell lysates from cross-linked ubc4-P61S and ubc4-P61S sre2Δ cells were used to immunopurify Sre2. Equal amounts of input (lanes 1 and 2), unbound (lanes 3 and 4), and 20× bound (20xB; lanes 5 and 6) fractions were analyzed by immunoblotting using HRP-conjugated Dsc antisera. Experiments were performed a minimum of three times. Representative results are shown.

DISCUSSION

Mammalian SREBP transcription factors are proteolytically activated through a well defined mechanism that requires the sequential action of the Golgi Site-1 and Site-2 proteases (2). In contrast, activation of fission yeast SREBPs, Sre1 and Sre2, occurs through a poorly defined mechanism that requires the multisubunit Golgi Dsc E3 ligase (6, 7). In this study, we used co-immunoprecipitation assays to define the protein interaction network of the Dsc E3 ligase (Fig. 2A). Dsc2 and Dsc4 are core components of the complex, whereas Dsc1, Dsc3, and Dsc5 are peripheral subunits. Blue native PAGE analysis confirmed these subunit interactions and revealed the presence of subcomplexes. Dsc2 formed multiple complexes that lacked the Dsc1 E3 ligase subunit in wild-type cells, suggesting that these subcomplexes may represent assembly intermediates. Although we cannot directly determine subunit stoichiometry, BN-PAGE indicated that Dsc1 may form homo-oligomers like the E3 ligase subunit Hrd1 of the multisubunit Hrd1 E3 ligase complex that functions in ERAD (29).

The luminal domain of Dsc1 is N-glycosylated, and glycosylation required the presence of Dsc2, Dsc3, and Dsc4, but not Dsc5 (Fig. 1). This change in glycosylation may be due to an altered conformation of Dsc1 in the absence of other subunits or differential Dsc1 localization. Unlike mammalian cells, fission yeast glycoproteins retain the high mannose structures obtained from ER core glycosylation after entering Golgi (30, 31), and thus, available enzymatic assays do not allow us to distinguish between ER and Golgi glycoproteins. However, these glycosylation results indicate that Dsc5 is somehow different from the other subunits: Dsc5 may assemble last or perhaps Dsc5 binding to a complex of Dsc1-Dsc2-Dsc3-Dsc4 is reversible or regulated.

Dsc2 Is a UBAC2-like Rhomboid Pseudoprotease

Rhomboid proteases are intramembrane cleaving proteases with a Ser-His catalytic dyad (24). Functions have recently been reported for inactive rhomboid proteases that retain the rhomboid structural fold but have lost residues required for catalytic activity (24). Two rhomboid pseudoproteases with key roles in ERAD are Derlin-1 and UBAC2 (14, 25). Previously, we identified Dsc2 as having sequence homology to Derlin family proteins and predicted Dsc2 to have four transmembrane helices and a C-terminal UBA domain (7). We now report that Dsc2 is a homolog of mammalian UBAC2, a rhomboid pseudoprotease with a C-terminal UBA domain (14). Using homology modeling, we showed that, similar to other rhomboid pseudoproteases, Dsc2 has significant structural similarity to E. coli rhomboid protease GlpG but that the catalytic Ser-His dyad is missing. The major structural difference between Derlin-1 and UBAC2 is the presence of a C-terminal UBA domain in UBAC2. Given that Dsc2 has a C-terminal UBA domain, we classify Dsc2 as a UBAC2-like rhomboid pseudoprotease.

UBAC2 was identified as an interacting partner of UBXD8 and the E3 ligase gp78 in a comprehensive analysis of the mammalian ERAD pathway (14). UBXD8 (also called FAF2) is a UBA, UAS, and UBX domain-containing membrane protein with a hairpin structure that is involved in degradation of ERAD substrates (14, 32–34). Interestingly, UBAC2 recruits UBXD8 to gp78 just as Dsc2 recruits Dsc5 to Dsc1. This conservation of E3 ligase architecture suggests functional conservation between the Dsc E3 ligase and mammalian ERAD ligases.

The molecular function of UBAC2 is unknown, but UBAC2 knockdown stabilizes the Hrd1-targeted ERAD substrates mutant α1 antitrypsin and transthyretin (14). Recently, UBAC2 was also found to function in the ER retention of UBXD8, thereby preventing UBXD8 localization to lipid droplets (15). Under certain cellular conditions UBXD8 localizes to lipid droplets, recruits p97/VCP through its UBX domain, and regulates the lipid droplet proteome (15, 35). UBXD8 is the closest human homolog of fission yeast Dsc5, suggesting that the function of these two proteins could be preserved through evolution. Using immunoprecipitation and BN-PAGE, we detected a stable binary complex between Dsc2-Dsc5 in wild-type cells that may perform analogous functions in yeast lipid homeostasis. Dsc2 plays a key role in Dsc E3 ligase function. Structurally, Dsc2 is a central component of the Dsc E3 ligase as no subcomplexes of other Dsc proteins form in its absence (Fig. 3) and the stability of Dsc4 requires Dsc2. Beyond its structural role, we speculate that Dsc2 functions in SREBP recognition by the Dsc E3 ligase for two reasons. First, Dsc2 cross-links to Sre2, suggesting a direct role for Dsc2 in SREBP binding. Second, rhomboid pseudoprotease family members bind transmembrane proteins (24). An exciting area for future studies will be to understand how rhomboid pseudoproteases, such as Derlins, UBAC2, and Dsc2, function in their respective E3 ligase complexes.

Dsc2 Contains a C-terminal UBA Domain

Consistent with the sequence homology between Dsc2 and UBAC2, we identified a functional UBA domain present at the C terminus of Dsc2 that binds Lys63 di-ubiquitin chains in vitro (Fig. 5C) (14). UBA domains are small (∼40 residues) ubiquitin-binding domains present in different protein families that mediate ubiquitin-dependent proteolysis and signaling (36). UBA domains show low sequence similarity but maintain a common structural fold comprised of three α helices. Structures are reported for >20 UBA domains from different species and the majority of them use a MGF motif present at the end of α1 helix and LL motif present at α3 for direct contact with ubiquitin (37, 38). Sequence alignment of the Dsc2 UBA domain with five other UBA domains indicates that the MGF motif is absent in Dsc2 but indicates that the LL motif, along with other conserved residues in α3, is present (Fig. 5A). It is possible that Dsc2 UBA domain folds similarly as other UBA domains but utilizes different residues in or around α1 helix to bind ubiquitin. Determining the structure of Dsc2 UBA domain would address this question.

The Dsc2 UBA domain bound directly to Lys63 di-ubiquitin but not Lys48 di-ubiquitin or mono-ubiquitin, under the conditions tested. UBA domains bind di- and tetra-ubiquitin of Lys48, Lys63 linkage, linear chain ubiquitin, and mono-ubiquitin in vitro with different affinities (38–41). Despite our ability to only detect an interaction with Lys63 di-ubiquitin in our assay, the Dsc2 UBA domain may recognize other ubiquitin configurations. For example, the ubiquitin binding affinities for the Dsc2 UBA domain in isolation could be different from that of full-length Dsc2. Structurally, Lys63 linked di- and tetra-ubiquitin adopt an open conformation with the Ile44 hydrophobic patch exposed, whereas Lys48 linked di- and tetra-ubiquitin adopt a closed cyclic conformation with the conserved hydrophobic patches shielded (42). Thus, structural differences could affect our ability to detect binding to Lys48 di-ubiquitin. Further detailed biochemical studies will be required to test whether the Dsc2 UBA domain exhibits linkage specificity in ubiquitin binding.

Mechanism for Yeast SREBP Cleavage

Bioinformatic analyses of the Golgi Dsc E3 ligase indicated sequence similarity to membrane-bound multisubunit RING E3 ligase complexes functioning in ERAD such as the Hrd1 E3 ligase in yeast and the Hrd1 and gp78 E3 ligases in mammalian cells (7, 12, 14). Now, our studies of the Golgi Dsc E3 ligase architecture reveal structural conservation of the interactions among Dsc1-Dsc2-Dsc5 and mammalian gp78-UBAC2-UBXD8. These accumulating data suggest that the Dsc E3 ligase may function in degradation of Golgi proteins. However, despite our improved knowledge of the Dsc E3 ligase architecture, the mechanism by which yeast SREBPs are proteolytically activated remains unknown. Previous studies implicated the proteasome in Sre1 proteolytic activation, but no direct evidence for this exists (7). In addition, although Sre1 cleavage requires the E2 ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme Ubc4 and the RING domain of the Dsc1 E3 ligase, ubiquitination of yeast SREBPs has not been demonstrated. Finally, although the Dsc E3 ligase contains functional domains found in ERAD E3 ligases, such as the Dsc2 UBA domain and the Dsc5 UBX domain, these domains are not essential for SREBP cleavage (Fig. 6) (6). One explanation is that these domains are functionally redundant for SREBP cleavage and that SREBP cleavage proceeds through an ERAD-like mechanism. Alternatively, the Dsc E3 ligase may have two independent functions: 1) mediator of SREBP cleavage and 2) an E3 ligase functioning in Golgi protein degradation. Identification of the yeast SREBP protease and additional Dsc E3 ligase substrates are important steps toward resolving these questions. Given the extensive parallels between the Golgi Dsc E3 ligase and the ERAD ligases, a detailed understanding of Dsc E3 ligase structure and function will advance our understanding of mammalian ERAD.

Lastly, studies from Cramer and co-workers (16, 43) using the pathogenic fungus Aspergillus fumigatus demonstrate that the SREBP homolog SrbA controls the hypoxic response, azole drug resistance, and iron homeostasis. Importantly, SrbA is required for A. fumigatus virulence in mouse models of disease. Similar to Sre1, SrbA activation requires homologs of dsc1 to dsc4, and a dsc5 homolog awaits characterization (17). Given this functional conservation, we expect that the architecture of the Aspergillus Dsc E3 ligase will resemble that of S. pombe. Thus, this study provides insight into the organization of the Dsc E3 ligase in this important human opportunistic pathogen.

Acknowledgments

We thank Emerson Stewart and Christine Nwosu for preliminary studies and strains and Shan Zhao for outstanding technical support. We are grateful to the following investigators for sharing strains and reagents: John Christianson (University of Oxford), Christopher Berndsen and Cynthia Wolberger (The Johns Hopkins University), Hiroaki Seino (Osaka City University, Osaka, Japan), Colin Gordon (Medical Research Council of UK), and Rasmus Hartmann-Petersen (University of Copenhagen, Denmark).

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants R01 HL077588 (to P. J. E.) and F31 HL097668 (S. J. L.).

This article contains supplemental Table 1.

- SREBP

- sterol regulatory element-binding protein

- BN-PAGE

- blue native PAGE

- ERAD

- ER-associated degradation

- UBA

- ubiquitin-associated

- UBX

- ubiquitin regulatory X

- aa

- amino acids.

REFERENCES

- 1. Shao W., Espenshade P. J. (2012) Expanding roles for SREBP in metabolism. Cell Metab. 16, 414–419 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Espenshade P. J., Hughes A. L. (2007) Regulation of sterol synthesis in eukaryotes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 41, 401–427 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Hughes A. L., Todd B. L., Espenshade P. J. (2005) SREBP pathway responds to sterols and functions as an oxygen sensor in fission yeast. Cell 120, 831–842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Porter J. R., Burg J. S., Espenshade P. J., Iglesias P. A. (2010) Ergosterol regulates sterol regulatory element binding protein (SREBP) cleavage in fission yeast. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 41051–41061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Todd B. L., Stewart E. V., Burg J. S., Hughes A. L., Espenshade P. J. (2006) Sterol regulatory element binding protein is a principal regulator of anaerobic gene expression in fission yeast. Mol. Cell Biol. 26, 2817–2831 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Stewart E. V., Lloyd S. J., Burg J. S., Nwosu C. C., Lintner R. E., Daza R., Russ C., Ponchner K., Nusbaum C., Espenshade P. J. (2012) Yeast sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP) cleavage requires Cdc48 and Dsc5, a ubiquitin regulatory X domain-containing subunit of the Golgi Dsc E3 ligase. J. Biol. Chem. 287, 672–681 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Stewart E. V., Nwosu C. C., Tong Z., Roguev A., Cummins T. D., Kim D. U., Hayles J., Park H. O., Hoe K. L., Powell D. W., Krogan N. J., Espenshade P. J. (2011) Yeast SREBP cleavage activation requires the Golgi Dsc E3 ligase complex. Mol. Cell 42, 160–171 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Stolz A., Hilt W., Buchberger A., Wolf D. H. (2011) Cdc48: a power machine in protein degradation. Trends Biochem. Sci. 36, 515–523 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Reggiori F., Pelham H. R. (2002) A transmembrane ubiquitin ligase required to sort membrane proteins into multivesicular bodies. Nat. Cell Biol. 4, 117–123 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ryan C. J., Roguev A., Patrick K., Xu J., Jahari H., Tong Z., Beltrao P., Shales M., Qu H., Collins S. R., Kliegman J. I., Jiang L., Kuo D., Tosti E., Kim H. S., Edelmann W., Keogh M. C., Greene D., Tang C., Cunningham P., Shokat K. M., Cagney G., Svensson J. P., Guthrie C., Espenshade P. J., Ideker T., Krogan N. J. (2012) Hierarchical modularity and the evolution of genetic interactomes across species. Mol. Cell 46, 691–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Alexandru G., Graumann J., Smith G. T., Kolawa N. J., Fang R., Deshaies R. J. (2008) UBXD7 binds multiple ubiquitin ligases and implicates p97 in HIF1α turnover. Cell 134, 804–816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Hirsch C., Gauss R., Horn S. C., Neuber O., Sommer T. (2009) The ubiquitylation machinery of the endoplasmic reticulum. Nature 458, 453–460 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Olzmann J. A., Kopito R. R., Christianson J. C. (2012) The mammalian endoplasmic reticulum-associated degradation system. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol., DOI 10.1101/cshperspect.a013185 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Christianson J. C., Olzmann J. A., Shaler T. A., Sowa M. E., Bennett E. J., Richter C. M., Tyler R. E., Greenblatt E. J., Harper J. W., Kopito R. R. (2012) Defining human ERAD networks through an integrative mapping strategy. Nat. Cell Biol. 14, 93–105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Olzmann J. A., Richter C. M., Kopito R. R. (2013) Spatial regulation of UBXD8 and p97/VCP controls ATGL-mediated lipid droplet turnover. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 1345–1350 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Willger S. D., Puttikamonkul S., Kim K. H., Burritt J. B., Grahl N., Metzler L. J., Barbuch R., Bard M., Lawrence C. B., Cramer R. A., Jr. (2008) A sterol-regulatory element binding protein is required for cell polarity, hypoxia adaptation, azole drug resistance, and virulence in Aspergillus fumigatus. PLoS. Pathog. 4, e1000200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Willger S. D., Cornish E. J., Chung D., Fleming B. A., Lehmann M. M., Puttikamonkul S., Cramer R. A. (2012) Dsc orthologs are required for hypoxia adaptation, triazole drug responses, and fungal virulence in Aspergillus fumigatus. Eukaryot Cell 11, 1557–1567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hartmann-Petersen R., Wallace M., Hofmann K., Koch G., Johnsen A. H., Hendil K. B., Gordon C. (2004) The Ubx2 and Ubx3 cofactors direct Cdc48 activity to proteolytic and nonproteolytic ubiquitin-dependent processes. Curr. Biol. 14, 824–828 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Penengo L., Mapelli M., Murachelli A. G., Confalonieri S., Magri L., Musacchio A., Di Fiore P. P., Polo S., Schneider T. R. (2006) Crystal structure of the ubiquitin binding domains of rabex-5 reveals two modes of interaction with ubiquitin. Cell 124, 1183–1195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Pickart C. M., Raasi S. (2005) Controlled synthesis of polyubiquitin chains. Methods Enzymol. 399, 21–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zielinska D. F., Gnad F., Schropp K., Wiśniewski J. R., Mann M. (2012) Mapping N-glycosylation sites across seven evolutionarily distant species reveals a divergent substrate proteome despite a common core machinery. Mol. Cell 46, 542–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Kelley L. A., Sternberg M. J. (2009) Protein structure prediction on the Web: a case study using the Phyre server. Nat. Protoc. 4, 363–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Söding J., Biegert A., Lupas A. N. (2005) The HHpred interactive server for protein homology detection and structure prediction. Nucleic Acids Res. 33, W244-W248 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Lemberg M. K. (2013) Sampling the membrane: function of rhomboid-family proteins. Trends Cell Biol. 23, 210–217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Greenblatt E. J., Olzmann J. A., Kopito R. R. (2011) Derlin-1 is a rhomboid pseudoprotease required for the dislocation of mutant α-1 antitrypsin from the endoplasmic reticulum. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 18, 1147–1152 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Zettl M., Adrain C., Strisovsky K., Lastun V., Freeman M. (2011) Rhomboid family pseudoproteases use the ER quality control machinery to regulate intercellular signaling. Cell 145, 79–91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mueller T. D., Kamionka M., Feigon J. (2004) Specificity of the interaction between ubiquitin-associated domains and ubiquitin. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 11926–11936 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gordon C., McGurk G., Wallace M., Hastie N. D. (1996) A conditional lethal mutant in the fission yeast 26 S protease subunit mts3+ is defective in metaphase to anaphase transition. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 5704–5711 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Carvalho P., Stanley A. M., Rapoport T. A. (2010) Retrotranslocation of a misfolded luminal ER protein by the ubiquitin-ligase Hrd1p. Cell 143, 579–591 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gemmill T. R., Trimble R. B. (1999) Overview of N- and O-linked oligosaccharide structures found in various yeast species. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1426, 227–237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ziegler F. D., Cavanagh J., Lubowski C., Trimble R. B. (1999) Novel Schizosaccharomyces pombe N-linked GalMan9GlcNAc isomers: role of the Golgi GMA12 galactosyltransferase in core glycan galactosylation. Glycobiology 9, 497–505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Mueller B., Klemm E. J., Spooner E., Claessen J. H., Ploegh H. L. (2008) SEL1L nucleates a protein complex required for dislocation of misfolded glycoproteins. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 12325–12330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lee J. N., Zhang X., Feramisco J. D., Gong Y., Ye J. (2008) Unsaturated fatty acids inhibit proteasomal degradation of Insig-1 at a postubiquitination step. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 33772–33783 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Lee J. N., Kim H., Yao H., Chen Y., Weng K., Ye J. (2010) Identification of Ubxd8 protein as a sensor for unsaturated fatty acids and regulator of triglyceride synthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 21424–21429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Suzuki M., Otsuka T., Ohsaki Y., Cheng J., Taniguchi T., Hashimoto H., Taniguchi H., Fujimoto T. (2012) Derlin-1 and UBXD8 are engaged in dislocation and degradation of lipidated ApoB-100 at lipid droplets. Mol. Biol. Cell 23, 800–810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Su V., Lau A. F. (2009) Ubiquitin-like and ubiquitin-associated domain proteins: significance in proteasomal degradation. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 66, 2819–2833 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Ohno A., Jee J., Fujiwara K., Tenno T., Goda N., Tochio H., Kobayashi H., Hiroaki H., Shirakawa M. (2005) Structure of the UBA domain of Dsk2p in complex with ubiquitin molecular determinants for ubiquitin recognition. Structure 13, 521–532 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Tse M. K., Hui S. K., Yang Y., Yin S. T., Hu H. Y., Zou B., Wong B. C., Sze K. H. (2011) Structural analysis of the UBA domain of X-linked inhibitor of apoptosis protein reveals different surfaces for ubiquitin-binding and self-association. PloS One 6, e28511. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Hurley J. H., Lee S., Prag G. (2006) Ubiquitin-binding domains. Biochem. J. 399, 361–372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Raasi S., Varadan R., Fushman D., Pickart C. M. (2005) Diverse polyubiquitin interaction properties of ubiquitin-associated domains. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 12, 708–714 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Matta-Camacho E., Kozlov G., Trempe J. F., Gehring K. (2009) Atypical binding of the Swa2p UBA domain to ubiquitin. J. Mol. Biol. 386, 569–577 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Datta A. B., Hura G. L., Wolberger C. (2009) The structure and conformation of Lys63-linked tetraubiquitin. J. Mol. Biol. 392, 1117–1124 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Blatzer M., Barker B. M., Willger S. D., Beckmann N., Blosser S. J., Cornish E. J., Mazurie A., Grahl N., Haas H., Cramer R. A. (2011) SREBP coordinates iron and ergosterol homeostasis to mediate triazole drug and hypoxia responses in the human fungal pathogen Aspergillus fumigatus. PLoS Genet. 7, e1002374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]