Abstract

Epigenetics is increasingly being recognized as a central component of physiological processes as diverse as obesity and circadian rhythms. Primarily acting through DNA methylation and histone posttranslational modifications, epigenetic pathways enable both short- and long-term transcriptional activation and silencing, independently of the underlying genetic sequence. To more quantitatively study the molecular basis of epigenetic regulation in physiological processes, the present review informs the latest techniques to identify and compare novel DNA methylation marks and combinatorial histone modifications across different experimental conditions, and to localize both DNA methylation and histone modifications over specific genomic regions.

Keywords: DNA methylation, histone posttranslational modifications, ChIP-SEQ, mass spectrometry

THE PAST AND PRESENT OF EPIGENETIC RESEARCH

epigenetics can be broadly defined as the study of heritable changes in phenotype that do not involve mutations to the DNA sequence, such as DNA methylation, histone posttranslational modifications, and noncoding RNAs (25). The oft-quoted examples of female X-chromosome inactivation in mammals (27) and position effect variegation in Drosophila melanogaster (56) emphasize the diversity of systems in which epigenetics is relevant. Recently, epigenetics has emerged as an important determinant in animal physiology. For instance, undernourishment of pregnant Wistar rats correlates with impaired locomoter ability of the fetus after birth, even if the fetus is supplied with proper nutrition (53). In addition, female offspring of obese and type II diabetic C57BL/6J female mice fed a diet with standard fat caloric value during the later stages of pregnancy were more resistant to subsequent high-fat diet-induced obesity than their male siblings (16), suggesting that epigenetic influences over the same physiological pathway can differ between sexes. Finally, the generally deleterious effect of stress has been demonstrated to have an epigenetic component. Although epigenetic events are generally perceived to occur in relatively long time scales, significant increases and decreases in histone methylation, namely H3 lysine 9 and 27 methylation levels, respectively, in the hippocampus were observed as quickly as 45 min after acute restraint stress in adult Sprague-Dawley rats (26).

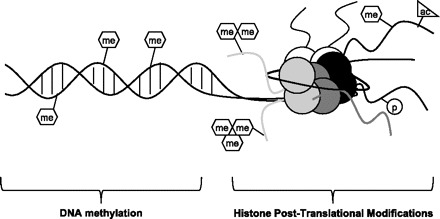

As epigenetic regulation becomes an increasingly important area of research within animal physiology, the appropriate technique to study epigenetics becomes an increasingly important consideration. In this review, we present the latest methods to study two of the major pathways in epigenetic regulation: DNA methylation and histone posttranslational modification (Fig. 1), and their potential to being applied to physiology studies.

Fig. 1.

Major branches of epigenetic regulation. Independent of genetic sequence, CpG island methylation and histone (white, gray, and black circles) posttranslational modifications (PTMs) are capable of positively and negatively regulating transcription. me, methylation (mono-, di-, and tri-methylated are possibilities for lysine residues, while mono- and di- are possibilities for arginine); p, phosphorylation; ac, acetylation.

DNA METHYLATION

DNA methylation is a common modification that occurs mostly on cytosines at CpG dinucleotides. Surprisingly, CpG dinulceotides are less common in mammalian genomes than would be expected by chance, largely due to the natural deamination of methylated cytosines into thymine (6). Accumulation of CpGs often occurred at promoter sequences, termed CpG islands, and can serve as methylation sites for imprinted genes(34). DNA methylation is commonly associated with silencing of the targeted DNA, such as repeat elements in pericentromeric DNA, the inactive X-chromosome in female cells or Barr body, and individual genes during genetic imprinting. The DNA methyltransferase Dnmt1 is responsible for de novo methylation that occurs during transcription and is maintained throughout the life of the cell (60). Cell type-specific methylation can also occur during development and likely makes an epigenetic contribution to cell identity (22). Although DNA methylation has long been associated with silencing, the mechanism remains unclear. What is known is that methylated cytosines can be bound by proteins that contain methyl binding domains (MBD) (40). These proteins can recruit histone deacetylases, proteins that have also been associated with silencing (41). Interactions with other histone modifying enzymes has lead to the idea that DNA methylation is one of many epigenetic components required for silencing of genes and heterochromatin formation (8). Methods to locate the sites of DNA methylation at specific loci as well as on a global scale have been developed over the last three decades (11). The methods discussed below utilize a powerful technique to distinguish between unmethylated and methylated cytosines by treating DNA with sodium bisulfite. This treatment facilitates the conversion of unmethylated cytosines to uracil (11). Amplification of the treated DNA causes uracil to be replaced with a thymine, and therefore methylated cytosines are located by preservation of cytosine at a particular nucleotide position when searching the amplified DNA against a reference genome, whereas unmethylated cytosines appear as substitutions from C to T.

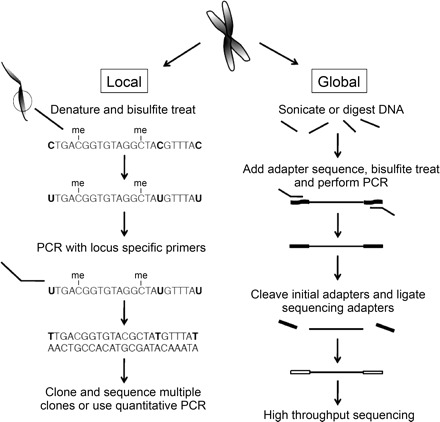

When the identification of DNA methylation at individual loci is required, bisulfite treatment followed by various types of PCR amplification and sequencing methods can be employed (Fig. 2). Some methods were developed to detect only the presence or absence of methylation at a locus (24). DNA was bisulfite converted and subjected to PCR with primers that would anneal to converted CpGs (unmethylated) or unconverted CpGs (methylated). The methylation status was determined by running the PCR reaction on an agarose gel and scoring for the presence or absence of a band for each set of primers. More quantitative approaches were also developed to determine how often a CpG or set of CpGs was methylated. Perhaps the easiest way to identify and quantify methylation sites at specific loci is to treat with bisulfite, perform PCR using primers that anneal outside of the region of interest (avoiding CpGs when designing primer sites), clone the DNA fragments into a sequencing vector, and sequence enough individual clones of the DNA to quantify the fraction of cells with methylated cytosines (10). This method has also been altered to take advantage of more quantitative methods of PCR, where bisulfite-treated DNA is amplified using real-time PCR or pyrosequencing (15, 47). Both ways of quantifying the levels of methylated cytosines can yield an accurate a relatively fast analysis of DNA methylation as a specific locus.

Fig. 2.

Local and global approaches to identifying cytosine methylation sites are shown. Local detection involves denaturing and bisulfite treatment of DNA before amplification of a particular locus. The unmethylated cytosines are shown in bold and are converted to thymines during the process. Unmethylated cytosines are indicated and can be identified during sequencing as remaining as cytosines. A method for global methylation detection is shown where the DNA is sonicated before bisulfite treatment. Adapters are used to ensure only converted DNA is used for sequencing. The second adapters are specific for next-generation sequencing chips.

Global analysis of DNA methylation has been limited due to a high volume of DNA that must be sequenced. One technique has solved this problem by using chromatin immunoprecipitation to enrich for methylated DNA, followed by detection on a microarray (MeDIP) (55). An antibody against methylated cytosine is used to isolate methylated DNA, which is then allowed to hybridize to a microarray with spots that include promoter regions. Input DNA is used as a background signal for determining the relative abundance of methylation at a particular locus. There is no need for bisulfite conversion since the enriched DNA should contain mostly methylated DNA. One drawback is that the resolution depends on the microarray chip being used and therefore does not have the potential to map cytosine methylations to individual nucleotide positions, especially in CpG rich promoters. Methods that can achieve single base resolution are those that utilize next-generation sequencing of bisulfite-treated genomic DNA.

These methods are more recent, owing to the fact that sequencing machines capable of scanning entire genomes are also recent. They involve preparing DNA for sequencing by digesting with an appropriate restriction endonuclease or sonicating to yield small fragments. Adapters with DnpI sites are added to the DNA fragments, and the DNA is bisulfite treated to convert any unmethylated cytosines to uracils, in the DNA fragments as well as the adapters. PCR is performed to amplify the sequences with primers that only anneal to bisulfite-converted adapters and therefore eliminate any partially converted or unconverted fragments from moving to the next step. The adapters are removed via digestion with DnpI, and new sequencing adapters are added that are compatible with next generation sequencing chips. The results can be striking and provide single-base pair resolution of DNA methylation. Two groups did this for the Arabidopsis genome in 2008 (12, 35). Cokus et al. (12) were able to show patterns of methylation relative to entire chromosomes or chromosome features such as coding regions and transposable elements. More importantly, they analyzed methylation patterns in methyltransferase mutant strains and showed that previous conclusions about one mutant strain might need to be refined after taking a more global view of its methylation defects. This technique, now shown to produce high-quality data, can be applied to a wide range of cells and allows researchers to screen mutants generated in the lab as well as naturally occurring mutant cells, such as cancer cells.

HISTONE POSTTRANSLATIONAL MODIFICATIONS

From methylation (37, 59) and acetylation to phosphorylation (43) and ubiquitination (54), the diversity of posttranslational modifications (PTMs) on histones serve as binding sites for effector proteins, forming what is referred to as a “histone code” of epigenetic regulation (Fig. 1) (28). Unlike CpG island methylation, histone PTMs are able to positively and negatively regulate transcription, and it should not be surprising that the broad epigenetic influence of histone PTMs is relevant to many fields within physiology. For instance, in the circadian regulation of transcription, one of the primary transcription factors, CLOCK, was demonstrated to acetylate lysine 14 (H3K14) and lysine 9 (H3K9) of histone H3 (14, 63). The histone acetyltransferase activity of CLOCK is essential for activating the expression of numerous downstream targets essential for circadian rhythm, namely mPer1 and Dbp. Acetylation, like all the known types of histone PTMs, is a reversible process. In the aforementioned situation of circadian rhythm regulation, CLOCK promotes expression of the nicotinamide phosphoribosyltransferase (NAMPT), the enzyme responsible for producing NAD. This allows for SIRT1 to deacetylate the histones on the NAMPT promoter, providing a negative-feedback loop and a circadian regulation of this specific promoter(39). An additional example highlighting the consequence of deacetylation is in regulation of apoptosis, senescence, and aging, where another histone deacetylase, SIRT6, was demonstrated to deacetylate H3K9 specifically on the promoters of NF-κB transcription factors, effectively repressing their expression (29). Homozygous mutants of SIRT6 lead to ectopic expression of those factors and exhibit increased apoptotic resistance and increased senescence; the collective influence of these effects likely accelerate aging.

To study the relation between histone PTMs and a particular physiological response, one must first be able to identify and quantify specific histone PTMs. The earliest detection methods involved incorporation of radiolabeled isotopes, such as [14C]acetate or [3H]acetate (2), and additional biochemical procedures, such as acid hydrolysis of the histones to release the radiolabeled acetic acid, confirming the radiolabeled moiety on the histones was an acetyl group (1). A more recent and common detection method is Western blotting. Excluding the cost of the primary antibodies, Western Blots are cost effective and have remarkable sensitivity in detection, as little as 30 pg of protein (7), compared with most other methods. However, there are some important limitations to Western blots. First and foremost, Western blots inherently require an a priori knowledge of what to probe and are unsuitable for global unbiased analyses on the relevant histone PTMs in a particular process. Second, quantification by Western blot typically requires determination of the area of the signal, either by software or a reflective densitometer, both of which provide rather imprecise measurements limited over a particular range of concentrations (7). Third, the quality of Western blot analysis is dependent on the specificity of the primary antibody. For instance, histone biotinylation has been documented in various sources, where much of the original evidence relied on biotin-specific antibodies (9, 31). Yet, a recent study showed that these antibodies cross-react with acetyl groups and, in fact, histone biotinylation does not occur in vivo (23). In addition to cross-reactivity, an important criteria for antibody quality is its susceptibility to epitope occlusion, whereby PTMs near the epitope sterically prevent antibody binding. These limitations of the classic Western blotting technique require the researcher to consider carefully the appropriate method for studying histone PTMs.

MASS SPECTROMETRY BASED PROTEIN SEQUENCING

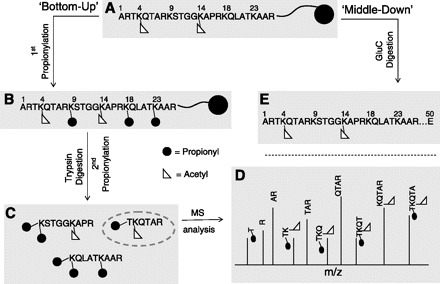

Mass spectrometry (MS) has recently emerged as an alternative method for quantitative and unbiased analysis of histone PTMs, and this review will cover several variations of MS analysis (Fig. 3). In all variations, MS measures the mass-to-charge (m/z) ratio of peptides based on their behavior in the gas phase. While peptide isomers (e.g., PEPTIDE vs. PTPEDIE) have the same mass, known as the precursor ion mass, sequential fragmentation of those isomers into their substituent amino acids and the subsequent m/z measurement of those fragments provide unambiguous identification of the peptide sequence, as well as precise localization of any PTM on specific residues (50). In practice, this is typically achieved with tandem MS, where the instrument takes both an MS and MS/MS spectra containing the precursor ions and the fragmentation ions of a particular precursor, respectively. Fragmentation is commonly achieved with collision-induced dissociation (CID), which results in preferential cleavage of adjacent amino acids at the peptide bond.

Fig. 3.

“Bottom-up” and “middle-down” mass spectrometry (MS). A: the principles of analyzing a hypothetical histone with K4 and K14 acetylation using “bottom up” or “middle down” MS. B: derivatization of the protein with propionic anhydride effectively caps unmodified and monomethylated lysine residues with a propionyl group (black circle), preventing trypsin digestion at those sites. Lysines containing other PTMs, like acetylation (white triangle), usually are not digested efficiently by trypsin. C: trypsin digestion produces various histone peptides. D: MS/MS spectra are collected for a particular peptide precursor (gray dashed circle from C) to reveal peptide sequence information (MS spectra of all the precursors are not shown). Note that the connectivity between K4 and K14 acetylation is lost as both modifications are on different peptides. Thus one does not know if original histone protein contains the 2 marks together or individually. E: GluC digest results in a larger histone peptide for “middle-down” MS analysis and preserves the connectivity of K4 and K14 acetylation.

One common tool to reduce the ion complexity of the MS and MS/MS spectra is to resolve peptides over time via reversed-phase liquid chromatography (RP-LC), such that more hydrophobic peptides elute later than more hydrophilic peptides. A useful feature of LC is the ability to directly connect the instrument to the mass spectrometer, where the eluted peptides in the liquid phase are ionized into the gas phase and are directed via an electric potential from the LC column to the mass spectrometer. Such a technique is known as electrospray ionization (ESI), and the instrument setup is known as LC-MS (20). Alternatively, peptides can be spotted onto a solid-phase matrix, where ionization from laser irradiation ejects the peptides from the matrix into the gas phase and the peptides are similarly directed to the mass spectrometer. This technique is known as matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionization (MALDI) and the entire instrument setup for this type of analysis is known as MALDI-MS. Due to the unique interface of MALDI-MS, recent innovations allow direct protein digestion and peptide ionization from immobilized tissue spreads, a technique known as MALDI-imaging (38). Thus MS and MS/MS information is obtained at particular locations on a tissue, providing a more biologically relevant spatial context of where peptide PTMs originate.

Often, intact proteins are not subjected to MS analysis and are instead digested via site-specific proteases such as trypsin into peptides that are themselves subjected to MS analysis. Trypsin is especially favorable for its substrate specificity of lysine or arginine (44), except if those residues are methylated. Digestion of proteins into small, approximately <20-amino acid peptides, and MS sequencing of those digests is known as “bottom-up” sequencing. Although bottom-up sequencing has been applied to a variety of proteins, this review will concern mostly with the application of bottom-up sequencing with histones and their PTMs.

Using bottom up to characterize histone modifications is a relatively new technique that has evolved from a discovery tool to a method for quantitatively measuring the abundances of PTMs on core histones (46, 52, 62). The general method used for analysis of histones by bottom-up MS begins with derivatization of histones extracted from cells by propionic anhydride to block unmodified lysines from trypsin cleavage, producing predictable histone peptides of mainly +2 charge (18). The derivatization step produces peptides that are of the approximately same length regardless of the modification status within the cell and therefore reduces the complexity of peptides that must be analyzed to determine abundances. If two samples are compared, such as from two organisms with different genetic backgrounds or one organism in two different physiological states, a heavy isotope of propionic anhydride can be used for one sample to produce a mass shift on those peptides and allow for both samples to be mixed and analyzed simultaneously in the same MS run. Bottom-up MS is not limited to simultaneous comparison of only two samples, and other methods can be applied for more high-throughput comparison (58).

When MS is applied to the analysis of histone modifications it can result in the identification of dozens of unique PTMs in a single experiment. The abundances of each modified form of a peptide can be determined by finding the intensity for all modified forms of the peptide and then comparing the intensity for one modification state to the sum of all modification states. For instance, propionylation of lysine 23 on histone H3 was recently identified and shown to be formed interestingly by the p300 acetyltransferase and to be depleted by the Sir2 deacetylase, using MS analysis (36). MS can also highlight interesting correlations of histone modifications between evolutionarily divergent organisms, where for instance, monomethylation of lysine 4 on histone H3 is conserved from human and the mouse M. musculus to the ciliate T. thermophila and the yeast S. cerevisiae, while acetylation of that same residue is mostly observed with human, and to a lesser extent in mouse and ciliates (17).

“MIDDLE-DOWN” AND “TOP-DOWN” MS

While bottom-up MS allows for unambiguous and facile sequencing of small peptides in a complex digest mixture, one cannot determine the connectivity of those peptides in the context of the original polypeptide chain. Stated differently, one cannot know the complete set of PTMs on a single protein from bottom-up sequencing. For proteins where all the sites of modification occur on a single tryptic peptide, the loss of connectivity is not a problem. However, histones such as H3 are extensively modified throughout the length of the amino-terminal tail. One solution is to sequence a larger peptide that encompasses more sites of modification, and for histone H3, this means digesting the protein not with trypsin, but rather with another protease such as GluC that cleaves at fewer sites along the polypeptide. Thus, as opposed to bottom-up MS, this type of sequencing of larger peptides provides a more bird's eye view of the entire protein and is called middle-down MS.

Larger histone peptides, though, carry more positive charge. Possession of extra charges has important consequences for both chromatography and MS. In terms of chromatography, although RP-LC can still be applied to middle-down MS, weak-cation exchange (WCX) hydrophilic interaction chromatography (HILIC) allows for greater resolution of highly modified peptides (61). In WCX-HILIC, an increasingly acidic pH gradient protonates the stationary phase to elute the peptides. Unlike RP-LC, this means that more hydrophilic peptides, such as those containing acetylation, elute later than more hydrophobic peptides, such as those containing methylation.

In terms of MS, CID fragmentation of highly positively charged peptides results in nonrandom cleavage of the peptide backbone, producing insufficient sequence coverage. Electron transfer dissociation (ETD) does not suffer from such a limitation, and due to the molecular mechanism of ETD (51), the peptide undergoes an intramolecular arrangement and fragments not between the carbonyl and amine of the peptide bond, as in CID, but rather between the amine and α-carbon. Despite the difference in fragmentation, unambiguous sequencing of the GluC-digest histone peptide can still be readily achieved and combinations of PTMs that before were missed by bottom-up MS can now be detected and quantified.

The best solution to extrapolate the original connectivity of all the PTMs on a protein, though, is to simply not digest the protein at all. This type of sequencing is known as “top-down” MS (29a). By its nature, top-down MS ensures 100% sequence coverage of the protein, allowing for truly unambiguous protein identification. Critical to the application of top-down MS is effective and high-throughput chromatography of intact proteins. A recent study published a two-step chromatography workflow where the first step relies on a gel column to resolve undigested proteins by molecular weight (33). Unlike standard size-exclusion chromatography, the lower molecular weight proteins elute first. The fractions are then resolved by standard reversed-phase liquid chromatography in the second step for MS analysis. Similar to middle-down, ETD is the fragmentation of choice for top-down MS. However, ETD fragmentation in top-down MS produces highly complex spectra filled with highly charged peaks of ion fragments. Thus a second ion/ion reaction typically between the ETD-generated fragments and deprotonated benzoic acid can be used to reduce the charge states of the peptide fragments, and thus the complexity of the spectra (13). At the expense of simpler spectra, many of the peptide fragments with larger masses are now beyond the dynamic range of most mass spectrometers.

The ability of middle-down and top-down MS to detect a more complete set of PTMs can be illustrated with a diverse set of proteins, from phosphorylation sites of cardiac myosin binding protein (21) to the methylation and acetylation sites of histones extracted from butyrate-treated human cells (19). Interesting conclusions can arise from such studies that could only have been attained by the larger sequence coverage of middle-down and top-down MS; for instance, a connection between K4 methylation and general acetylation on histone H3 was observed (19). Here, the levels of histone H3K4 methylation were found to increase with the abundance and number of histone acetylation sites, and no K4 methylation was observed on H3 species that did not contain at least one acetylation site. Thus, with bottom-up, mddle-down, and top-down MS, a scientist is equipped with the analytical tools to identify and quantify PTMs of not only histones, but also of any protein of interest.

CHROMATIN IMMUNOPRECIPITATION

The above methods for detecting histone modifications are excellent for providing a global view of single modification abundances or the distribution of modifications relative to neighboring residues on histone tails. Often times more resolution is needed to identify the locations of modifications at individual promoters or coding sequences. Methods have been developed using antibodies to enrich for nucleosomes containing a particular modified histone and the associated DNA (chromatin immunoprecipitation or ChIP). Antibodies that recognize a given histone modification can be incubated with fragmented chromatin to bind nucleosomes containing the modification of interest. The DNA associated with the nucleosomes can be detected by Southern blot, quantitative PCR, detection on a microarray, or sequenced using next-generation sequencing technology (32, 45, 49, 57).

The first high-resolution method used for indentifying histone locations was ChIP-chip, where antibodies were used to enrich for histone modifications and the associated DNA was hybridized to a microarray (4, 30, 48). This technique is limited to the coverage provided by the microarray, which might not cover the entire genome, and could provide less than optimal resolution for the positions of modifications. In 2005, Bernstein et al. (4) used this technique to map H3K4 di- and trimethylation and H3K9/K14 acetylation on two human chromosomes, and found correlations with H3K4me3 and transcription start sites, as well as conservation of methylation sites between human and mouse. Their coverage of two chromosomes, although pivotal at the time, did not sample 98% of the genome. Full genome coverage has been made more routine through the development of high-throughput sequencing technologies.

The use of antibodies to enrich for DNA associated with histone modifications followed by high-throughput sequencing is referred to as ChIP-seq and has an enormous amount of power to characterize the importance of histone modifications relative to genes and their expression status (45). This method has been applied to human T cells for a variety of histone modifications. Using microarray data as a measure of the expression level of each gene, the authors were able to confirm that some modifications are associated with actively transcribed genes, while others are associated with silent genes (3). Novel correlations between the location of some modifications and transcriptional activity were also noted. Other studies in embryonic stem cells, using ChIP-chip, showed that antagonist modifications can be present on the same promoter, creating “bivalent domains” where both active and repressive modifications coexist (5). Following differentiation, one modification is removed allowing the other to maintain an active or repressed chromatin state. This chromatin plasticity followed by expression memory will be interesting to explore outside of the context of stem cell differentiation and see if it is a more common phenomenon by which cells tag promoters with opposing marks and let the cellular fate determine which mark remains.

GRANTS

B. A. Garcia acknowledges funding support from Princeton University, the National Science Foundation (CBET-0941143), the American Society for Mass Spectrometry Research award sponsored by the Waters, and a New Jersey Commission on Cancer Research SEED grant. A. G. Evertts and B. M. Zee were supported by Predoctoral Training Grant T3Z-CA-009528.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest (financial or otherwise) are declared by the authors.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of the Garcia lab for enlightening discussion.

REFERENCES

- 1. Allfrey VG, Faulkner R, Mirsky AE. Acetylation and methylation of histones and their possible role in the regulation of RNA synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 51: 786–794, 1964 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Allfrey VG, Pogo BG, Littau VC, Gershey EL, Mirsky AE. Histone acetylation in insect chromosomes. Science 159: 314–316, 1968 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Barski A, Cuddapah S, Cui K, Roh TY, Schones DE, Wang Z, Wei G, Chepelev I, Zhao K. High-resolution profiling of histone methylations in the human genome. Cell 129: 823–837, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Bernstein BE, Kamal M, Lindblad-Toh K, Bekiranov S, Bailey DK, Huebert DJ, McMahon S, Karlsson EK, Kulbokas EJ, 3rd, Gingeras TR, Schreiber SL, Lander ES. Genomic maps and comparative analysis of histone modifications in human and mouse. Cell 120: 169–181, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bernstein BE, Mikkelsen TS, Xie X, Kamal M, Huebert DJ, Cuff J, Fry B, Meissner A, Wernig M, Plath K, Jaenisch R, Wagschal A, Feil R, Schreiber SL, Lander ES. A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells. Cell 125: 315–326, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Bird AP. DNA methylation and the frequency of CpG in animal DNA. Nucleic Acids Res 8: 1499–1504, 1980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Blake MS, Johnston KH, Russell-Jones GJ, Gotschlich EC. A rapid, sensitive method for detection of alkaline phosphatase-conjugated anti-antibody on Western blots. Anal Biochem 136: 175–179, 1984 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Cedar H, Bergman Y. Linking DNA methylation and histone modification: patterns and paradigms. Nat Rev Genet 10: 295–304, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Chew YC, West JT, Kratzer SJ, Ilvarsonn AM, Eissenberg JC, Dave BJ, Klinkebiel D, Christman JK, Zempleni J. Biotinylation of histones represses transposable elements in human and mouse cells and cell lines and in Drosophila melanogaster. J Nutr 138: 2316–2322, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Clark SJ, Harrison J, Paul CL, Frommer M. High sensitivity mapping of methylated cytosines. Nucleic Acids Res 22: 2990–2997, 1994 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Clark SJ, Statham A, Stirzaker C, Molloy PL, Frommer M. DNA methylation: bisulphite modification and analysis. Nat Protoc 1: 2353–2364, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Cokus SJ, Feng S, Zhang X, Chen Z, Merriman B, Haudenschild CD, Pradhan S, Nelson SF, Pellegrini M, Jacobsen SE. Shotgun bisulphite sequencing of the Arabidopsis genome reveals DNA methylation patterning. Nature 452: 215–219, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Coon JJ, Ueberheide B, Syka JE, Dryhurst DD, Ausio J, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF. Protein identification using sequential ion/ion reactions and tandem mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 102: 9463–9468, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Doi M, Hirayama J, Sassone-Corsi P. Circadian regulator CLOCK is a histone acetyltransferase. Cell 125: 497–508, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Eads CA, Danenberg KD, Kawakami K, Saltz LB, Blake C, Shibata D, Danenberg PV, Laird PW. MethyLight: a high-throughput assay to measure DNA methylation. Nucleic Acids Res 28: E32, 2000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Gallou-Kabani C, Vigé A, Gross MS, Boileau C, Rabes JP, Fruchart-Najib J, Jais JP, Junien C. Resistance of high-fat diet in the female progeny of obese mice fed a control diet during the periconceptual, gestation, and lactation periods. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 292: E1095–E1100, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Garcia BA, Hake SB, Diaz RL, Kauer M, Morris SA, Recht J, Shabanowitz J, Mishra N, Strahl BD, Allis CD, Hunt DF. Organismal differences in post-translational modifications in histones H3 and H4. J Biol Chem 282: 7641–7655, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Garcia BA, Mollah S, Ueberheide BM, Busby SA, Muratore TL, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF. Chemical derivatization of histones for facilitated analysis by mass spectrometry. Nat Protoc 2: 933–938, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Garcia BA, Pesavento JJ, Mizzen CA, Kelleher NL. Pervasive combinatorial modification of histone H3 in human cells. Nat Methods 4: 487–489, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Gaskell S. Electrospray: Principles and Practice. J Mass Spectrom 32: 677–688, 1997 [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ge Y, Rybakova IN, Xu Q, Moss RL. Top-down high-resolution mass spectrometry of cardiac myosin binding protein C revealed that truncation alters protein phosphorylation state. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 12658–12663, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Geiman TM, Muegge K. DNA methylation in early development. Mol Reprod Dev 77: 105–113, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Healy S, Perez-Cadahia B, Jia D, McDonald MK, Davie JR, Gravel RA. Biotin is not a natural histone modification. Biochim Biophys Acta 1789: 719–733, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Herman JG, Graff JR, Myohanen S, Nelkin BD, Baylin SB. Methylation-specific PCR: a novel PCR assay for methylation status of CpG islands. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 93: 9821–9826, 1996 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ho DH, Burggren WW. Epigenetics and transgenerational transfer: a physiological perspective. J Exp Biol 213: 3–16, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hunter RG, McCarthy KJ, Milne TA, Pfaff DW, McEwen BS. Regulation of hippocampal H3 histone methylation by acute and chronic stress. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 106: 20912–20917, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Jaenisch R, Bird A. Epigenetic regulation of gene expression: how the genome integrates intrinsic and environmental signals. Nat Genet 33: 245–254, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Jenuwein T, Allis CD. Translating the histone code. Science 293: 1074–1080, 2001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Kawahara TL, Michishita E, Adler AS, Damian M, Berber E, Lin M, McCord RA, Ongaigui KC, Boxer LD, Chang HY, Chua KF. SIRT6 links histone H3 lysine 9 deacetylation to NF-kappaB-dependent gene expression and organismal life span. Cell 136: 62–74, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29a. Kelleher NL, Lin HY, Valaskovic GA, Aaserud DJ, Fridriksson EK, McLafferty FW. Top down versus bottom up protein characterization by tandem high-resolution mass spectrometry. J Am Chem Soc 121: 806–812, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 30. Kim TH, Barrera LO, Zheng M, Qu C, Singer MA, Richmond TA, Wu Y, Green RD, Ren B. A high-resolution map of active promoters in the human genome. Nature 436: 876–880, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Kothapalli N, Camporeale G, Kueh A, Chew YC, Oommen AM, Griffin JB, Zempleni J. Biological functions of biotinylated histones. J Nutr Biochem 16: 446–448, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kuo MH, Allis CD. In vivo cross-linking and immunoprecipitation for studying dynamic Protein:DNA associations in a chromatin environment. Methods 19: 425–433, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Lee JE, Kellie JF, Tran JC, Tipton JD, Catherman AD, Thomas HM, Ahlf DR, Durbin KR, Vellaichamy A, Ntai I, Marshall AG, Kelleher NL. A robust two-dimensional separation for top-down tandem mass spectrometry of the low-mass proteome. J Am Soc Mass Spectrom 20: 2183–2191, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Li E, Beard C, Jaenisch R. Role for DNA methylation in genomic imprinting. Nature 366: 362–365, 1993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Lister R, O'Malley RC, Tonti-Filippini J, Gregory BD, Berry CC, Millar AH, Ecker JR. Highly integrated single-base resolution maps of the epigenome in Arabidopsis. Cell 133: 523–536, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Liu B, Lin YH, Darwanto A, Song XH, Xu GL, Zhang KL. Identification and characterization of propionylation at histone H3 lysine 23 in mammalian cells. J Biol Chem 284: 32288–32295, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Martin C, Zhang Y. The diverse functions of histone lysine methylation. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 6: 838–849, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. McDonnell LA, van Remoortere A, van Zeijl RJ, Dalebout H, Bladergroen MR, Deelder AM. Automated imaging MS: toward high throughput imaging mass spectrometry. J Proteomics 73: 1279–1282, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Nakahata Y, Sahar S, Astarita G, Kaluzova M, Sassone-Corsi P. Circadian control of the NAD+ salvage pathway by CLOCK-SIRT1. Science 324: 654–657, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Nan X, Meehan RR, Bird A. Dissection of the methyl-CpG binding domain from the chromosomal protein MeCP2. Nucleic Acids Res 21: 4886–4892, 1993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Nan X, Ng HH, Johnson CA, Laherty CD, Turner BM, Eisenman RN, Bird A. Transcriptional repression by the methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 involves a histone deacetylase complex. Nature 393: 386–389, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Nowak SJ, Corces VG. Phosphorylation of histone H3: a balancing act between chromosome condensation and transcriptional activation. Trends Genet 20: 214–220, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Olsen JV, Ong S, Mann M. Trypsin cleaves exclusively C-terminal to arginine and lysine. Mol Cell Proteomics 3: 608–614, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Park PJ. ChIP-seq: advantages and challenges of a maturing technology. Nat Rev Genet 10: 669–680, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Plazas-Mayorca MD, Zee BM, Young NL, Fingerman IM, LeRoy G, Briggs SD, Garcia BA. One-pot shotgun quantitative mass spectrometry characterization of histones. J Proteome Res 8: 5367–5374, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Reed K, Poulin ML, Yan L, Parissenti AM. Comparison of bisulfite sequencing PCR with pyrosequencing for measuring differences in DNA methylation. Anal Biochem 397: 96–106, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Roh TY, Cuddapah S, Zhao K. Active chromatin domains are defined by acetylation islands revealed by genome-wide mapping. Genes Dev 19: 542–552, 2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Spencer VA, Sun JM, Li L, Davie JR. Chromatin immunoprecipitation: a tool for studying histone acetylation and transcription factor binding. Methods 31: 67–75, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Steen H, Mann M. The ABC's (and XYZ's) of peptide sequencing. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 5: 699–711, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Syka JE, Coon JJ, Schroeder MJ, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF. Peptide and protein sequence analysis by electron transfer dissociation mass spectrometry. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101: 9528–9533, 2004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Syka JE, Marto JA, Bai DL, Horning S, Senko MW, Schwartz JC, Ueberheide B, Garcia B, Busby S, Muratore T, Shabanowitz J, Hunt DF. Novel linear quadrupole ion trap/FT mass spectrometer: performance characterization and use in the comparative analysis of histone H3 post-translational modifications. J Proteome Res 3: 621–626, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Teran-Garcia M, Rankinen T, Bouchard C. Genes, exercise, growth, and the sedentary, obese child. J Appl Physiol 105: 988–1001, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Weake VM, Workman JL. Histone ubiquitination: triggering gene activity. Mol Cell 29: 653–663, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Weber M, Davies JJ, Wittig D, Oakeley EJ, Haase M, Lam WL, Schubeler D. Chromosome-wide and promoter-specific analyses identify sites of differential DNA methylation in normal and transformed human cells. Nat Genet 37: 853–862, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Weiler KS, Wakimoto BT. Heterochromatin and gene expression in Drosophila. Annu Rev Genet 29: 577–605, 1995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Wu J, Smith LT, Plass C, Huang TH. ChIP-chip comes of age for genome-wide functional analysis. Cancer Res 66: 6899–6902, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Wu WW, Wang G, Baek SJ, Shen RF. Comparative study of three proteomic quantitative methods, DIGE, cICAT, and iTRAQ, using 2D gel- or LC-MALDI TOF/TOF. J Proteome Res 5: 651–658, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Wysocka J, Allis CD, Coonrod S. Histone arginine methylation and its dynamic regulation. Front Biosci 11: 344–355, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Yoder JA, Soman NS, Verdine GL, Bestor TH. DNA (cytosine-5)-methyltransferases in mouse cells and tissues. Studies with a mechanism-based probe. J Mol Biol 270: 385–395, 1997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Young NL, DiMaggio PA, Plazas-Mayorca MD, Baliban RC, Floudas CA, Garcia BA. High throughput characterization of combinatorial histone codes. Mol Cell Proteomics 8: 2266–2284, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zhang L, Eugeni EE, Parthun MR, Freitas MA. Identification of novel histone post-translational modifications by peptide mass fingerprinting. Chromosoma 112: 77–86, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Zhang X, Dube TJ, Esser KA. Working around the clock: circadian rhythms and skeletal muscle. J Appl Physiol 107: 1647–1654, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]