Abstract

Purpose

To evaluate the equivalence of the PROMIS® wave 1 physical functioning item bank, by age (50 years or older versus 18-49).

Materials and methods

A total of 114 physical functioning items with 5 response choices were administered to English- (n=1504) and Spanish-language (n=640) adults. Item frequencies, means and standard deviations, item-scale correlations, and internal consistency reliability were estimated. Differential Item Functioning (DIF) by age was evaluated.

Results

Thirty of the 114 items were fagged for DIF based on an R-squared of 0.02 or above criterion. The expected total score was higher for those respondents who were 18-49 than those who were 50 or older.

Conclusions

Those who were 50 years or older versus 18-49 years old with the same level of physical functioning responded differently to 30 of the 114 items in the PROMIS® physical functioning item bank. This study yields essential information about the equivalence of the physical functioning items in older versus younger individuals.

Keywords: Survey Research, Physical function, Item Response Theory (IRT), Differential Item Functioning (DIF)

Introduction

The number of people over the age of 65 in the U.S. is growing at an historically unparalleled rate. Furthermore, the racial and ethnic composition of this population is also changing with the percentage of minorities projected to grow from 16% in 2000 to 26% in 2030 [1]. A large proportion of these minority elders will consist of Latinos, the fastest growing minority group in the U.S. and among older adults [2-5]. According to the 2009 California Health Interview Survey (CHIS), the percentage of Latinos who were over 65 grew from 4% to 5%, and according to the 2010 census data, this percentage grew from 14% to 18% [6,7]. Latinos have gone from comprising 5% of the total U.S. population in 1970, to 9% in 1990, and 12% in 2000 [3,4]. While the overall U.S. population increased by 13% from 1990 to 2000, the Latino population increased by 58% [4,6]. The U.S. Bureau of Census projects that the proportion of Latinos in the U.S. general population will increase significantly due to immigration, greater longevity, higher birth rates, and lower infant mortality rates [5,8,9].

The National Institutes of Health (NIH) Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) was a research initiative designed to develop, validate, and standardize item banks [10]. With the advent of the patient's perspective in health evaluation, the goal of PROMIS® was to develop item banks that would measure key symptoms of chronic conditions enabling accurate measurement of patient reported outcomes. These item banks would be openly available to researchers. Item banks go beyond static questionnaires by calibrating all items on a same underlying metric. Assessment is more flexible and efficient by selecting individualized subsets of items, thus allowing for the use of Computer Adaptive Testing (CAT). One key goal of the PROMIS® initiative was to improve precision and enhance the comparability of health outcomes measures. Comparison between different subgroups assumes items mean the same to people of different groups. If subjects respond differently according to some external variable, there is lack of equivalence in the comparison.

Physical functioning, a central component of physical health, is a fundamental aspect of health for older persons. It is one of the strongest predictors of mortality and health care utilization [11,12]. A 124-item physical functioning item bank was administered to 1504 adults in English for the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) project [11]. The PROMIS® physical functioning bank includes items assessing mobility (lower extremity), dexterity (upper extremity), axial or central (neck and back function), and activities that overlap more than one domain (daily living activities) [12].

A total of 114 of the 124 items in the PROMIS® physical functioning item bank was translated into Spanish using a rigorous method [13-15] involving 2 initial forward translations, 1 reconciled version, 1 back-translation by a native English speaker, comparison of original with back-translation, and reviews by 3 bilingual experts from different Spanish-speaking countries. Fifteen cognitive interviews with native-Spanish speakers followed to evaluate item-comprehension. The items were divided into three groups and each group was debriefed by five subjects. The Spanish translated items were administered to 640 adult Spanish-speaking Latinos [16].

While Differential Item Functioning (DIF) of the PROMIS® physical functioning items between English- and Spanish-language respondents has been evaluated [17], the equivalence of responses for the older and younger respondents has not yet been evaluated. This paper presents analyses comparing the PROMIS® physical functioning items in those 50 or older versus those 18-49. This study is especially relevant given that physical functioning decreases with age and is a primary outcome measure in older persons. Therefore, the PROMIS® physical functioning item bank is only equivalent in measurement across ages, if older and younger subjects with the same level of underlying physical functioning respond equally to these items.

Materials and Methods

Data were collected from English-language adults from the U.S. general population and multiple disease groups (n=21,133). Of these, 1,532 were recruited from primary research sites associated with PROMIS® network sites. The majority of the data were collected by YouGov Polimetrix, a polling firm based in Palo Alto, CA [18]. Using a sample-matching procedure, this company obtains a representative sample of the general population [19]. Other than the online sample being more educated, the PROMIS® online panel had similar demographic characteristics as the US census [20]. Respondents for the Spanish sample were recruited from the Spanish-speaking subjects participating in the Toluna online panel, an independent survey technology provider [16,17]. The Spanish sample was relatively younger and less educated than the English sample.

Descriptive statistics including item frequencies, and means and standard deviations for the physical functioning items were estimated using Stata 9. Item Response Theory (IRT) assumptions were previously evaluated and reported elsewhere [17].

DIF was assessed by comparing responses of those 50 or older (n=889) versus those 18-49 (n=1253). Even though our original intention was to analyze the English- and Spanish-speaking samples separately, we did not have sufficient power in the Spanish-speaking sample even when dichotomizing those 50 or older versus younger. Therefore, DIF was assessed simultaneously for the English- and Spanish-speaking respondents. There was one missing value for the age variable in the English sample and therefore this individual was excluded from the analysis. There was no missing data in the Spanish sample. DIF is present if the probability of selecting a particular response varies by age group when controlling for the underlying level of physical functioning. We evaluated DIF using ordinal logistic regression with IRT-based trait scores estimated from DIF-free “anchor” items (iterative purification) as the conditioning variable. An R2 difference of less than 0.02 between nested models was used to identify potential anchor items. We examined the magnitude of DIF for those 50 or older versus those 18-49 using test characteristic curves separately for all physical functioning items and for the items identified as having DIF. We assessed DIF at the individual level by plotting theta estimates ignoring DIF versus theta estimates accounting for DIF. DIF analyses were run using Lordif software [21].

Results

One hundred percent of the Spanish-speaking sample was Hispanic while 11% of the English-speaking sample reported being Hispanic and 75% being Non-Hispanic White. Thirteen percent of the Spanish-speaking sample reported reading and speaking only Spanish, 48% speaking Spanish better than English, 39% reading and speaking both languages equally, and only 1 person reported reading and speaking English better than Spanish. Thirty-three percent reported speaking only Spanish at home, 51% speaking more Spanish than English at home, and 15% speaking both equally at home.

The average age of the Spanish-speaking sample was 38 with a range from 18 to 77. Fourteen percent of the sample was 50 years or older. The average age of the English-speaking sample was 51 with a range from 18 to 93. Fifty-three percent was 50 years or older. Fifty-eight percent of the Spanish-speaking sample were female, while fifty-two percent were female in the English-speaking sample. Fourteen percent reported less than a completed high school education in the Spanish sample, while 2% did in the English sample. Socio demographic characteristics of the sample are provided in table 1.

Table 1.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Characteristics of Spanish (n=640) and English (n=1504) Physical Function Sample.

| Spanish | English | Comparison | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age: (mean/SD/range) | 37.6 (11.3) 18-77 | 51.1 (18.3) 18-93 | t(1869)=20.8; pr<.0001 |

| SASH score1: (mean/SD/range) | 2.02 (0.53) 1-2.75 | ||

| Age categories: (n/%) | |||

| 18-24 | 100 (16) | 137 (9) | chi(4)=309.9; pr<0.0001 |

| 25-34 | 145 (23) | 196 (13) | |

| 35-44 | 226 (35) | 222 (15) | |

| 45-49 | 82 (13) | 146 (10) | |

| 50+ | 87 (14) | 802 (53) | |

| Gender: (n/%) | |||

| Male | 271 (42) | 716 (48) | 2-sided pr<0.0261 |

| Female | 369 (58) | 788 (52) | |

| Race/Ethnicity: (n/%) | |||

| Hispanic | 640 (100) | 158 (11) | |

| Non-Hispanic White | - | 1123 (75) | |

| Non-Hispanic Black or African American | - | 156 (10) | |

| Non-Hispanic other race | - | 63 (4) | |

| Education: (n/%) | |||

| Less than High School Grad/GED | 91 (14) | 23 (2) | chi(4)=169.4; pr<0.0001 |

| HS graduate/GED | 142 (22) | 270 (18) | |

| Some college | 199 (31) | 581 (39) | |

| College degree | 156 (24) | 381 (25) | |

| Advanced degree | 52 (8) | 247 (16) |

SASH Score: Short Acculturation Scale for Hispanics (SASH); the rating scale ranges from 1 (“Only Spanish”) to 5 (“Only English”) and an average score <3.0 reflects low acculturation.

The 114 physical function items had 5 response options each: 1=worst physical function (cannot do or unable to do activity) and 5=best physical function (health does not limit at all in doing activity). Sufficient unidimensionality of the physical functioning items in the English sample [10] and the Spanish sample [17] were reported previously.

Identification of DIF

Thirty of the 114 items were fagged for age DIF based on the R2 of 0.02 or above criterion; 28 uniform and 2 non-uniform (Table 2). Items with uniform DIF have the same direction of DIF along the entire range of physical function; the item response curves for the two groups do not cross. In non-uniform DIF items, these lines cross along the physical function continuum, indicating that the direction of the DIF changes with more or less functioning.

Table 2.

Items with Age DIF (28 - uniform DIF and 2 - non-uniform DIF).

| Items with Uniform DIF | |

|---|---|

| English | Spanish |

| Does your health now limit you in doing vigorous activities, such as running, lifting heavy objects, participating in strenuous sports? | ¿Limita su salud en este momento su capacidad para realizar actividades vigorosas, como correr, levantar objetos pesados o participar en deportes enérgicos? |

| Does your health now limit you in bending, kneeling, or stooping? | ¿Limita su salud en este momento su capacidad para inclinarse, arrodillarse o agacharse? |

| Does your health now limit you in doing heavy work around the house like scrubbing floors, or lifting or moving heavy furniture? | ¿Limita su salud en este momento su capacidad para realizar trabajos pesados en el hogar, como fregar (restregar) los pisos (el suelo), o levantar o mover muebles pesados? |

| Are you able to exercise for an hour? | ¿Puede hacer ejercicio durante una hora? |

| Are you able to run or jog for two miles (3 km)? | ¿Puede correr o trotar dos millas (3 km)? |

| Are you able to go up and down stairs at a normal pace? | ¿Puede subir y bajar escaleras a un paso normal? |

| Are you able to do yard work like raking leaves, weeding, or pushing a lawn mower? | ¿Puede realizar trabajos en el jardín, como rastrillar las hojas, desyerbar o empujar una cortadora de césped? |

| Are you able to exercise hard for half an hour? | ¿Puede hacer ejercicio intenso durante media hora? |

| Are you able to run at a fast pace for two miles (3 km)? | ¿Puede correr dos millas (3 km) a un ritmo rápido? |

| Are you able to squat and get up? | ¿Puede ponerse en cuclillas y levantarse? |

| Are you able to brush your teeth? | ¿Puede cepillarse los dientes? |

| Are you able to sit on the edge of a bed? | ¿Puede sentarse en el borde de una cama? |

| Does your health now limit you in hiking a couple of miles (3 km) on uneven surfaces, including hills? | ¿Limita su salud en este momento su capacidad para caminar un par de millas (3 km) sobre superficies irregulares, incluso en colinas? |

| Does your health now limit you in doing strenuous activities such as backpacking, skiing, playing tennis, bicycling or jogging? | ¿Limita su salud en este momento su capacidad para realizar actividades vigorosas, como practicar el excursionismo con mochila, esquiar, jugar al tenis, correr en bicicleta o trotar? |

| Are you able to jump up and down? | ¿Puede saltar hacia arriba y hacia abajo? |

| Are you able to run a short distance, such as to catch a bus? | ¿Puede correr una distancia corta, como para alcanzar un autobús?7 |

| Does your health now limit you in doing moderate activities, such as moving a table, pushing a vacuum cleaner, bowling, or playing golf? | ¿Limita su salud en este momento su capacidad para realizar actividades moderadas como mover una mesa, empujar una aspiradora, jugar al bowling o al golf, o trabajar en el jardín? |

| Does your health now limit you in participating in active sports such as swimming, tennis, or basketball? | ¿Limita su salud en este momento su capacidad para participar en deportes activos, como la natación, el tenis o el baloncesto? |

| Are you able to run five miles (8 km)? | ¿Puede correr cinco millas (8 km)? |

| Does your health now limit you in climbing several fights of stairs? | ¿Limita su salud en este momento su capacidad para subir varios pisos de escaleras? |

| Are you able to run 100 yards (100 m)? | ¿Puede correr 100 yardas (100 m)? |

| Are you able to climb up 5 fights of stairs? | ¿Puede subir 5 tramos de escaleras? |

| Are you able to run ten miles (16 km)? | ¿Puede correr diez millas (16 km)? |

| Does your health now limit you in doing eight hours of physical labor? | ¿Limita su salud en este momento su capacidad para realizar ocho horas de trabajo físico? |

| Are you able to walk at a normal speed? | ¿Puede caminar a una velocidad normal? |

| Are you able to kneel on the floor? | ¿Puede arrodillarse en el piso (suelo)? |

| Are you able to sit down in and stand up from a low, soft couch? | ¿Puede sentarse y levantarse de un sofá bajo y blando? |

| Does your health now limit you in getting in and out of the bathtub? | ¿Limita su salud en este momento su capacidad para entrar y salir de la tina o bañera? |

| Items with Non-Uniform DIF | |

| Does your health now limit you in walking several hundred yards/meters? | ¿Limita su salud en este momento su capacidad para caminar varios cientos de yardas/metros? |

| Does your health now limit you in walking more than a mile (1.6 km)? | ¿Limita su salud en este momento su capacidad para caminar más de una milla (1.6 km)? |

DIF impact

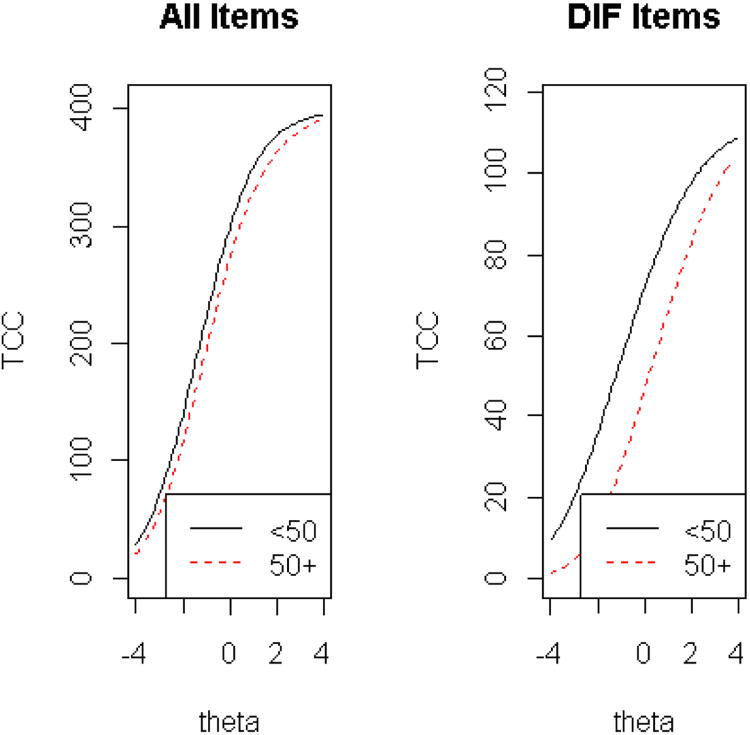

The impact of age DIF items on Test Characteristic Curves (TCCs) is shown in figure 1. The graph on the left of figure 1 shows the TCC for all 114 items while the graph on the right shows the TCC for just the 30 items with DIF. These curves indicate that the expected physical functioning total score is higher for those respondents who are younger than 50, controlling for underlying physical functioning. These differences need to be compared to the Minimally Important Difference (MID) for the PROMIS® physical functioning scale. Estimates have not yet been published, but preliminary analyses suggest an MID around 0.20 of a SD.

Figure 1.

Impact of DIF on test characteristic curves.

Discussion

Limitations in physical functioning are major health-related problems affecting the elderly. As the proportion of older persons and diversity of this segment of the population increases, it becomes more important to have adequate survey measures to assess them equivalently. One of the goals of PROMIS® is to improve precision and enhance the comparability of health outcomes measures across subgroups [10,11]. Comparison between different age groups is only possible when items mean the same to people from the different groups.

The limitations of this study are worth noting. The sample had higher education levels than what the Census data for the general US population in 2010 [22]. Furthermore, the sample was primarily recruited online and therefore was comprised of computer literate subjects. No heritage of country of birth was collected, so no conclusion can be drawn about this factor either, as it compares with the general US population. Further analyses would be helpful to better characterize the sample used. Furthermore, the possible causes of the identified DIF are unclear, thus, we cannot determine if these items should be dropped or adjusted in analyses. Further studies, including qualitative work, are needed to guide decisions about when to drop items versus adjust for the DIF identified in this study.

Thirty of the 114 items showed differential item functioning between respondents over 50 versus those 18-49. Because physical functioning is an important concept to be measured in an aging population, future studies need to evaluate the impact of this DIF and examine possible causes.

Acknowledgments

This paper was supported in part by an NIH cooperative agreement (1U54AR057951). Sylvia H. Paz and Ron D. Hays were supported in part by a grant from the NIA (P30AG021684). Sylvia H. Paz was also supported by NIH/NCRR/NCATS UCLA CTSI Grant Number UL1TR000124. Ron D. Hays was also supported by UCLA/DREW Project EXPORT, NIMHD, (2P20MD000182). The papers' contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH.

Abbreviations

- PROMIS®

Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System

- CHIS

California Health Interview Survey

- IRT

Item Response Theory

- DIF

Differential Item functioning

- TCC

Test Characteristic Curves

References

- 1.http://seniorjournal.com/NEWS/SeniorStats/5-05-31ProfleOlderAm2004.html

- 2.US Bureau of the Census. Current Population Reports Series P-20, no 455. US Govt. Printing Office; Washington, DC: Mar, 1991. The Hispanic population in the United States. [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Census Bureau. (NP-T4-F) Projections of the total resident population by 5-year age groups, race, and Hispanic origin with special age categories. Census 2000 US Demographic profile and population center; Washington, D.C. 20033: [Google Scholar]

- 4.U.S. Census Bureau. Current population reports (P25-1130) Population projections of the US by age, sex, race, and Hispanic origin [Google Scholar]

- 5.http://www.census.gov/population/www/socdemo/hispanic/hispanic_pop_presentation.html

- 6.www.chis.ucla.edu

- 7.http://www.census.gov/prod/cen2010/briefs/c2010br-02.pdf

- 8.Shorris E. Latinos: A biography of the people. W.W. Norton & Co; New York: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Morales LS, Lara M, Kington RS, Valdez RO, Escarce JJ. Socioeconomic, cultural, and behavioral factors affecting hispanic health outcomes. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2002;13:477–503. doi: 10.1177/104920802237532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cella D, Riley W, Stone A, Rothrock N, Reeve B, et al. The Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) developed and tested its first wave of adult self-reported health outcome item banks: 2005-2008. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1179–1194. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2010.04.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rose M, Bjorner JB, Becker J, Fries JF, Ware JE. Evaluation of a preliminary physical function item bank supported the expected advantages of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System (PROMIS®) J Clin Epidemiol. 2008;61:17–33. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.06.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bruce B, Fries JF, Ambrosini D, Lingala B, Gandek B, et al. Better assessment of physical function: item improvement is neglected but essential. Arthritis Res Ther. 2009;11:R191. doi: 10.1186/ar2890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bonomi AE, Cella DF, Hahn EA, Bjordal K, Sperner-Unterweger B, et al. Multilingual translation of the Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy (FACT) quality of life measurement system. Qual Life Res. 1996;5:309–320. doi: 10.1007/BF00433915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cella D, Hernandez L, Bonomi AE, Corona M, Vaquero M, et al. Spanish language translation and initial validation of the functional assessment of cancer therapy quality-of-life instrument. Med Care. 1998;36:1407–1418. doi: 10.1097/00005650-199809000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lent L, Hahn E, Eremenco S, Webster K, Cella D. Using cross-cultural input to adapt the Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) scales. Acta Oncol. 1999;38:695–702. doi: 10.1080/028418699432842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.http://us.toluna.com/

- 17.Paz SH, Spritzer KL, Morales LS, Hays RD. Evaluation of the Patient-Reported outcomes Information System (PROMIS®) Spanish-Language Physical Functioning Items. Qual Life Res 2012 Nov 3. 2012 doi: 10.1007/s11136-012-0292-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.http://research.yougov.com/services/scientific_research/ from http://www.polimetrix.com

- 19.Rivers D. Sample matching: representative sampling from Internet panels. Palo Alto, CA: Polimetrix, Inc; 2006. p. 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu H, Cella D, Gershon R, Shen J, Morales LS, et al. Representativeness of the Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Internet panel. J Clin Epidemiol. 2010;63:1169–1178. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2009.11.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi SW, Gibbons LE, Crane PK. Lordif: An R Package for Detecting Differential Item Functioning Using Iterative Hybrid Ordinal Logistic Regression/Item Response Theory and Monte Carlo Simulations. J Stat Softw. 2011;39:1–30. doi: 10.18637/jss.v039.i08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.http://www.census.gov/hhes/socdemo/education/data/cps/2010/tables.html