Abstract

Propagation of inflammatory signals from the airspace to the vascular space is pivotal in lung inflammation, but mechanisms of intercompartmental signaling are not understood. To define signaling mechanisms, we microinfused single alveoli of blood-perfused rat lung with TNF-α, and determined in situ cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) by the fura-2 ratio method, cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) activation and P-selectin expression by indirect immunofluorescence. Alveolar TNF-α increased [Ca2+]i and activated cPLA2 in alveolar epithelial cells, and increased both endothelial [Ca2+]i and P-selectin expression in adjoining perialveolar capillaries. All responses were blocked by pretreating alveoli with a mAb against TNF receptor 1 (TNFR1). Crosslinking alveolar TNFR1 also increased endothelial [Ca2+]i. However, the endothelial responses to alveolar TNF-α were blocked by alveolar preinjection of the intracellular Ca2+ chelator BAPTA-AM, or the cPLA2 blockers AACOCF3 and MAFP. The gap-junction uncoupler heptanol had no effect. We conclude that TNF-α induces signaling between the alveolar and vascular compartments of the lung. The signaling is attributable to ligation of alveolar TNFR1 followed by receptor-mediated [Ca2+]i increases and cPLA2 activation in alveolar epithelium. These novel mechanisms may be relevant in the alveolar recruitment of leukocytes.

Introduction

Airborne pathogens, a major cause of lung inflammatory disease, induce leukocyte influx into alveolar spaces (1). Increasing interest in this pathophysiology has focused on the role of cytokines such as TNF-α that are released by alveolar macrophages and thereby exert the chemotactic effect of recruiting leukocytes from perialveolar capillaries (2, 3). A central unanswered question is how the chemotactic signal crosses the alveolar wall to reach the capillaries.

The alveolar barrier restricts transport of macromolecules of a size similar to that of cytokines (∼15–20 kDa). After secretion in alveoli, cytokines such as TNF-α remain in the alveolar space (4, 5) and leak into the circulation only in alveolar barrier injury (6). Hence, with the barrier intact, alveolar cytokines are unlikely to have rapid access to perialveolar capillaries. Despite this poor access, instilled TNF-α in the airspace induces neutrophil influx (7). Although mechanisms are unclear, a receptor-mediated process may be involved, because soluble TNF receptor–IgG chimera, anti–TNF-α Abs, and absence of TNF receptor-1 (TNFR1) attenuate neutrophil influx to airspace pathogens and aerosolized lipopolysaccharide (8–11).

Our main goal was to test the hypothesis that instillation of TNF-α into the alveolar space sends a signal to the adjoining capillary endothelium. Because TNF-α mobilizes Ca2+, we selected cytosolic Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) as a marker of the signaling (12–15). Frequently, [Ca2+]i subserves gap junction– or paracrine-based intercellular communication (16, 17) that may be relevant. Endothelial [Ca2+]i transients induce vascular expression of the leukocyte trafficking receptor P-selectin that may initiate neutrophil influx (18, 19). Using our recently developed methods for quantifying [Ca2+]i and P-selectin expression in situ (20, 21), we tested these possibilities in intact alveolocapillary units of the rat lung. We report a novel mechanism in which intra-alveolar infusion of TNF-α induced a rapid proinflammatory response in adjacent capillaries.

Methods

Antibodies and other reagents.

Goat anti-rat TNFR1 mAb E-20 was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc. (Santa Cruz, California, USA) (22). Rabbit anti-rat cytosolic phospholipase A2 (cPLA2) Ab was purchased from Genetics Institute Inc. (Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA). Fab fragment of rabbit anti-goat IgG and donkey anti-mouse IgG were purchased from Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc. (West Grove, Pennsylvania, USA). FITC-conjugated donkey anti-goat IgG came from ICN Biomedicals Inc. (Costa Mesa, California, USA). Goat anti-mouse IgG (Fc-specific; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Missouri, USA) and goat anti-rabbit IgG (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories Inc.) were also purchased. Mouse anti-rat P-selectin mAbs RMP-1 and RP-2 were gifts of A.C. Issekutz (Department of Pediatrics, Microbiology-Immunology and Pathology, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada) (23).

Other agents used were fura-2 AM and HOECHST 33342 (Molecular Probes Inc., Eugene, Oregon, USA), TNF-α, arachidonic acid, linoleic acid, heptanol, indomethacin (all from Sigma Chemical Co.), saponin (ICN Biomedicals Inc.), the PLA2 inhibitors AACOCF3, MAFP, and BEL, the Ca2+i chelator 1,2-bis-(o-aminophenophenoxyethane)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid tetra-(acetoxymethyl)-ester (BAPTA-AM; Calbiochem-Novabiochem Corp., San Diego, California, USA), MK886 (Biomol Research Laboratories, Plymouth Meeting, Pennsylvania, USA), and WEB 2170BS (gift of Boehringer Ingelheim Inc., Ridgefield, Connecticut, USA). Intracapillary infusions were given in vehicle consisting of 2% dextran (70 kDa; Pharmacia Biotech Inc., Piscataway, New Jersey, USA), 1% FBS (Gemini Bio-Products Inc., Calabasas, California, USA), HEPES solution at pH 7.4 and osmolarity of 295 ± 5 mOsm, containing (in mmol/L) 150 Na+, 5 K+, 1 Ca2+, and 10 glucose. Intra-alveolar infusions were given in vehicle consisting of 0.1% delipidated BSA (fraction V; Sigma Chemical Co.) and Ringer’s solution at pH 7.4 and osmolarity of 295 ± 5 mOsm, containing (in mmol/L) 137 Na+, 2.7 K+, 1 Ca2+, and 28 lactate.

Lung fluorescence microscopy.

The microscopy methods have been described (20, 21). Briefly, lungs excised from anesthetized Sprague-Dawley rats were continuously pump-perfused at 14 mL/min with autologous rat blood at 37°C. Lungs were constantly inflated at an airway pressure of 5 cmH2O. Pulmonary artery and left atrial pressures were held at 10 cmH2O and 5 cmH2O, respectively. The lung surface was kept moist with normal saline at 37°C and viewed by epifluorescence microscopy.

Fluorophores were excited by mercury lamp illumination directed through appropriate filters. Fluorescence emission was collected through objective lenses (Wplan FL ×40 UV; Olympus America Inc., Melville, New York, USA, or Ph3 Neofluar ×100; Carl Zeiss Jena GmbH, Jena, Germany) and dichroic and emission filters (400DCLPO2 and 510WB40; Omega Optical Inc., Brattleboro, Vermont, USA, or DM500 and O-515; Olympus America Inc.) by image intensifier (KS1381; Video Scope International Ltd., Sterling, Virginia, USA) and video camera (CCD-72; Dage-MTI Inc., Michigan City, Indiana, USA), then subjected to digital image analysis (MCID-M4; Imaging Research Inc., St. Catharine’s, Ontario, Canada).

Substance delivery.

For intra-alveolar infusions, a single alveolus was selected. The microscope objective was adjusted until the maximum diameter of the alveolus came into focus. By micropuncture, the alveolus was infused to fill 3–4 neighboring (nonmicropunctured) alveoli. One of the nonmicropunctured alveoli was selected for imaging. Intracapillary infusions were given either by capillary micropuncture or by a wedged venous microcatheter (PE-10; Baxter Diagnostics Inc., Deerfield, Illinois, USA) as described (20, 21). Agents were infused in the following concentrations: fura-2 AM, 10 μM; HOECHST 33342, 5 μg/mL; TNF-α, 10–10,000 U/mL; arachidonic acid, 0.1–10 μM; linoleic acid, 10 μM; BAPTA-AM, 40 μM; heptanol, 3 mM; AACOCF3, 1 μM; MAFP, 25 μM; BEL, 1 μM; indomethacin, 20 μM; MK886, 1 μM; WEB 2170BS, 50 μM; saponin, 0.01%. These substances were all given by alveolar infusion. TNF-α, fura-2, and heptanol were also given by capillary infusion. BAPTA-AM was given in Ca2+-free Ringer’s solution. Capillary blood cell–free or Ca2+-free conditions were established by infusion of 2% dextran HEPES solution that was either Ca2+-rich or Ca2+-free (containing 0.5 mmol/L EGTA), 10 minutes before measurements were taken.

[Ca2+]i imaging.

Our in situ methods have been reported (20). For epithelial and endothelial [Ca2+]i determinations, fura-2 AM (which deesterifies intracellularly to impermeant fura-2), was given for 30 minutes by intra-alveolar or intracapillary infusion, respectively. Infused alveoli were washed with 3% reconstituted bovine surfactant (Survanta; Abbott Laboratories, Columbus, Ohio, USA). Alveoli and capillaries loaded with fura-2 were excited at 340 nm and 380 nm, and [Ca2+]i was determined from the computer-generated 340:380 ratio based on a Kd of 224 nmol/L and appropriate calibration parameters (20, 24). Dominant oscillation frequency and amplitude were determined for [Ca2+]i oscillations of amplitude greater than 15 nM using fast Fourier transformation (Origin V 4.0; Microcal Software Inc., Northampton, Massachusetts, USA).

Indirect immunofluorescence in situ.

These methods have been described (21). To determine epithelial TNFR1 expression, an alveolus was infused first with E-20 (10 μg/mL) or control mAb RP-2 (10 μg/mL) for 10 minutes, then with the secondary FITC-conjugated mAb (75 μg/mL) for 1 minute. Unbound fluorescence was removed by infusion of Ringer’s solution. To determine endothelial P-selectin expression, RMP-1 (35 μg/mL) was infused into a single capillary for 10 minutes, then secondary FITC-conjugated mAb (1:20) was infused for 1 minute. Unbound fluorescence was removed by blood flow in less than 30 seconds (21). Residual FITC fluorescence indicated expression of the targeted antigen. To assess activation of cPLA2, we adapted an immunofluorescence assay reported in vitro (25) that involves permeabilization of the cell membrane by 0.5% Triton X-100. Membrane permeabilization not only permits cell loading with primary and secondary Abs, but also causes loss of unbound cytoplasmic molecules such as nonactivated cPLA2 when cells are subsequently washed. Hence, no immunofluorescent staining for cytoplasmic cPLA2 is detectable in unstimulated cells. However, in activated cells, staining occurs on the translocated fraction of cPLA2 that becomes membrane bound and thus remains intracellular. Therefore, to carry out the assay, we first infused an alveolus for 5 minutes with TNF-α or vehicle, then fixed and permeabilized the alveolus by infusion of 4% paraformaldehyde and 0.5% Triton X-100 for 10 minutes and 4 minutes, respectively. We then infused the alveolus with anti-rat cPLA2 Ab (1:5) and FITC-conjugated IgG (1:10), followed by alveolar washes with infusions of Ringer’s solution. Residual fluorescence indicated the presence of activated, membrane-bound cPLA2 (25). Alveolar epithelial nuclei were stained in situ by alveolar infusion of HOECHST 33342 (26) followed by a wash.

Receptor crosslinking in situ.

Crosslinking of the alveolar TNFR1 was performed by sequential intra-alveolar infusions of E-20 (10 μg/mL), secondary anti-goat IgG (60 μg/mL), and finally Ringer’s solution to wash the alveolus. For control, the isotype-matched mAb RP-2 (10 μg/mL) replaced E-20 in the crosslinking protocol.

Statistics.

All data are mean ± SEM. Values of several groups were compared using the Wilcoxon and Friedman test for dependent groups, and Kruskal-Wallis and Mann-Whitney U tests for independent groups. Linear regression analysis was performed using SigmaPlot (Jandel Scientific Software, San Rafael, California, USA). Statistical significance was accepted at P < 0.05.

Results

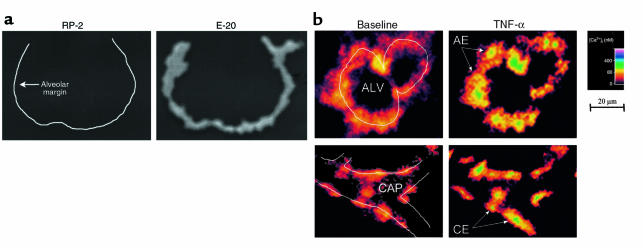

Using indirect immunofluorescence in situ, we confirmed the uniform presence of TNFR1 in alveoli (Figure 1a). No alveolar fluorescence was detected with the isotype-matched control mAb RP-2, which recognizes rat tissue but not alveolar epithelial antigen. Epithelial [Ca2+]i was determined in several cells of the imaged alveolus. Endothelial responses were similar in lung venular and alveolar septal capillaries, therefore we have not distinguished between these locations in reporting the data.

Figure 1.

In situ lung imaging. (a) Images of a single alveolus show indirect immunofluorescence for a nonspecific mAb (RP-2) and an anti-TNFR1 mAb (E-20). Line in left image was drawn from parallel bright-field image. Replicated 3 times. (b) Images show the 340:380 ratio color-coded for [Ca2+]i in an alveolus (ALV) and its adjoining capillary (CAP). Line sketches depict alveolar and capillary margins. Individual alveolar epithelial (AE) and capillary endothelial (CE) cells are indicated. Images were obtained in the same alveolus and capillary at baseline (left) and 5 minutes after alveolar infusion of 1,000 U/mL TNF-α (right). Replicated 8 times.

Because our procedures involved alveolar micropuncture, we confirmed that no capillary fluorescence was detectable 30 minutes after an intra-alveolar infusion of FITC-conjugated IgG, which ruled out macromolecular leakage across the alveolar membrane (n = 3; not shown).

Intra-alveolar TNF-α.

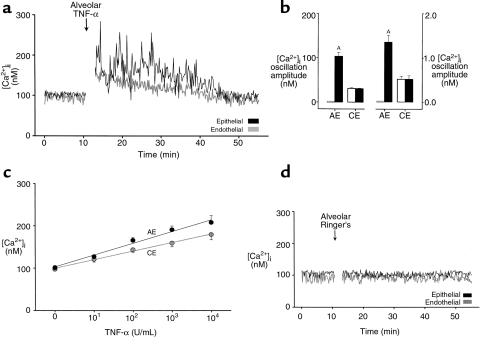

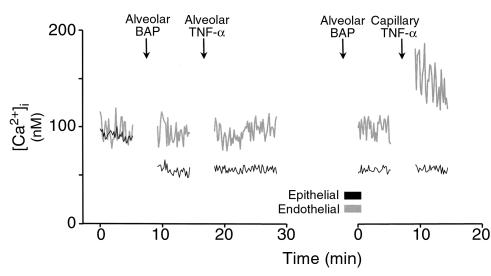

We gave intra-alveolar TNF-α infusion for 10 seconds. As exemplified by the alveolocapillary unit shown in Figure 1b, [Ca2+]i increased in all epithelial and endothelial cells in the imaged area (P < 0.05). The [Ca2+]i increases, consisting of marked [Ca2+]i oscillations in epithelial cells (Figure 2, a and b), occurred in less than 2 minutes and persisted for more than 20 minutes. By contrast, oscillations were not enhanced in endothelial cells. Increases in mean [Ca2+]i were concentration dependent for both cell types (Figure 2c). Alveolar infusion of Ringer’s solution had no effect on [Ca2+]i (Figure 2d).

Figure 2.

[Ca2+]i responses to intra-alveolar infusion of TNF-α. (a) Tracings are from an epithelial cell of an alveolus and an endothelial cell of an adjoining capillary as indicated. TNF-α injected at 1,000 U/mL. Replicated 8 times. (b) Data show amplitude (left panel) and frequency (right panel) of [Ca2+]i oscillations. Open bars, baseline; filled bars, 5 minutes after alveolar TNF-α infusion (1,000 U/mL). AP < 0.05 vs. baseline; n = 8 experiments. AE, alveolar epithelial cells; CE, capillary endothelial cells. (c) Group [Ca2+]i responses 5 minutes after alveolar TNF-α infusion. Each point is mean ± SEM of 4 experiments. Lines were drawn by linear regression (P < 0.001). (d) Single experiment tracings show [Ca2+]i responses to intra-alveolar infusion of Ringer’s solution. Replicated 4 times.

Intracapillary TNF-α.

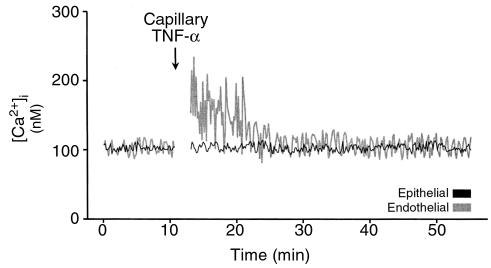

The single experiment tracings in Figure 3 depict [Ca2+]i responses to intracapillary infusion of TNF-α. Not only did mean [Ca2+]i increase (P < 0.05), but there was a marked increase in the amplitude of [Ca2+]i oscillations (P < 0.05). Moreover, the [Ca2+]i increases were sustained for shorter durations than were those for alveolar infusions (P < 0.05). Epithelial [Ca2+]i did not increase.

Figure 3.

Single experiment tracings show [Ca2+]i responses to intracapillary infusion of TNF-α (1,000 U/mL). Replicated 5 times.

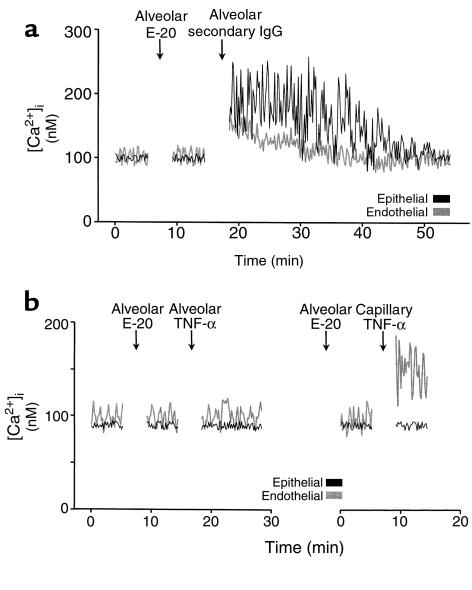

E-20 ligation.

Figure 4a shows that alveolar infusion of mAb E-20 alone had no effect on [Ca2+]i, although a subsequent alveolar infusion of the crosslinking secondary Ab induced [Ca2+]i increases in epithelial and endothelial cells (P < 0.05). These responses were not different from those for alveolar infusion of TNF-α. The left panel in Figure 4b shows that alveolar infusion of E-20 followed by infusion of TNF-α did not increase epithelial or endothelial [Ca2+]i. Therefore, E-20 blocked [Ca2+]i responses to alveolar TNF-α (P < 0.05). The right panel are data from the same alveolocapillary unit, showing that with E-20 in the alveolus, capillary TNF-α still induced endothelial [Ca2+]i increases (P < 0.05). Therefore, alveolar infusion of E-20 did not block endothelial [Ca2+]i responses to TNF-α given by capillary infusion.

Figure 4.

E-20 ligation in a single alveolocapillary unit. Intra-alveolar infusion of Ab E-20 was followed by alveolar infusion of (a) secondary IgG or (b) TNF-α (1,000 U/mL), given either by alveolar (left panel) or capillary (right panel) infusion. Replicated 4 times.

In experiments that are not shown here, we confirmed that the nonspecific mAb RP-2 caused no [Ca2+]i responses, either as the primary mAb in the crosslinking protocol (n = 3) or as a control for the inhibitory effect of E-20 (n = 3). Hence, the crosslinking and blocking effects of E-20 were specific to receptor ligation. We also confirmed that when E-20 and TNF-α were both given sequentially by capillary infusion, endothelial [Ca2+]i increases were blocked (P < 0.05). However, capillary infusion of E-20 did not block [Ca2+]i increases to alveolar infusion of TNF-α (n = 4; not shown).

Ca2+i chelation.

A 15-minute alveolar infusion of the membrane-permeable intracellular Ca2+i chelator BAPTA-AM blocked both epithelial and endothelial [Ca2+]i responses to alveolar TNF-α (P < 0.05; Figure 5, left). However, capillary infusion of TNF-α still induced an endothelial [Ca2+]i increase (P < 0.05; Figure 5, right). Therefore, alveolar infusion of BAPTA-AM blocked the endothelial response because it blocked the epithelial response. Capillary perfusion with Ca2+-free HEPES also blocked endothelial [Ca2+]i increases induced by alveolar TNF-α (P < 0.05), indicating that endothelial Ca2+ entry was required for the response (n = 4; not shown).

Figure 5.

Ca2+ chelation in a single alveolocapillary unit. BAP (BAPTA-AM), 40 μM. TNF-α, 1,000 U/mL. Alveolar or capillary routes of infusion are indicated. Replicated 4 times.

Not shown are experiments in which we determined that heptanol (a cell uncoupler; ref. 27), given by either the alveolar or the capillary route, had no inhibitory effects on either epithelial or endothelial responses to alveolar infusion of TNF-α (n = 4 each). Capillary perfusion with blood cell–free, Ca2+-rich HEPES solution did not abolish the endothelial [Ca2+]i response to alveolar TNF-α (n = 4, not shown). Hence, the [Ca2+]i signal in endothelial cells did not result from adherence and emigration of intravascular neutrophils.

Activation of cPLA2.

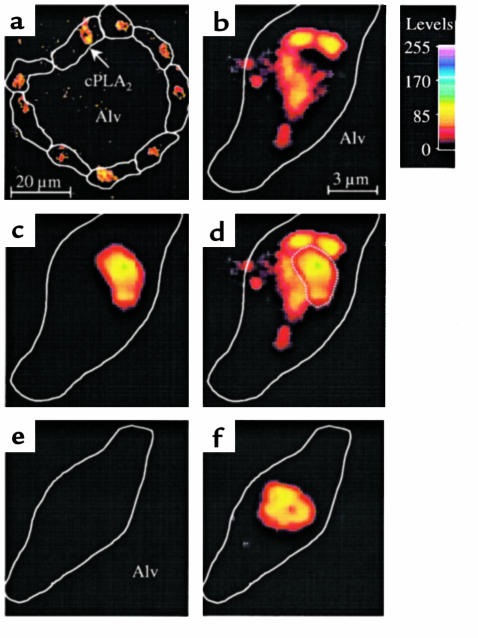

TNF-α causes Ca2+-dependent activation of cPLA2, leading to arachidonate release (28). Activated cPLA2 translocates to cellular membranes and the nuclear envelope (25). Immunofluorescence of membrane-bound cPLA2 was detectable in several epithelial cells in single alveoli infused with TNF-α (Figure 6a). Overlaying images for cPLA2 immunofluorescence (Figure 6b) and nuclear fluorescence (Figure 6c) revealed close apposition of cPLA2 to the nucleus (Figure 6d), indicating that cPLA2 was translocated to the perinuclear region. No cPLA2 staining was detected when alveoli were infused with Ringer’s solution before immunofluorescence labeling (Figure 6e), although nuclear staining was positive (Figure 6f).

Figure 6.

Translocation of cPLA2 in single alveoli. An alveolus was infused with 1,000 U/mL TNF-α (a–d) or with Ringer’s solution (e and f). Then the alveolus was stained for both the immunofluorescence of cPLA2 (a, b, e) and the nuclear fluorescence of HOECHST 33324 (c and f). The alveolus was washed and imaged at low (a) and high (b–f) magnifications as indicated by the scale bars. Color code shows fluorescence intensities. Cell margins identified by bright-field microscopy are depicted by line sketches. Alv, alveolar lumen. Images for cPLA2 and nuclear fluorescence were combined by image overlay (d, f). Nuclear outline is indicated by dotted line (d). Replicated 4 times.

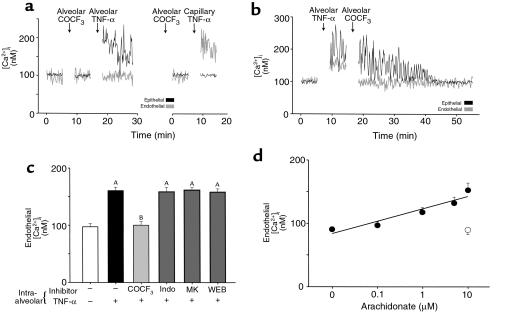

Alveolar infusions of the cPLA2 inhibitor AACOCF3, given 10 minutes before alveolar TNF-α infusion, blocked the endothelial [Ca2+]i response (P < 0.05) but not the epithelial response (Figure 7a, left). Endothelial [Ca2+]i increases were rescued in the presence of intra-alveolar AACOCF3 by capillary infusion of TNF-α (P < 0.05; Figure 7a, right). We interpret this to mean that AACOCF3 given by the alveolar route did not block direct endothelial responses to TNF-α.

Figure 7.

Effects of cPLA2 and its products. (a and b) Tracings from single experiments. Alveolar or capillary routes of TNF-α infusion are indicated. Replicated 4 times each. (c) Group data for indicated inhibitors given in 10-minute alveolar infusions before alveolar infusion of TNF-α; n = 4 for each. AP < 0.05 vs. baseline (open bar). BP < 0.05 vs. TNF-α (solid bar). COCF3, AACOCF3; indo, indomethacin; MK, MK886; WEB, WEB 2170BS. (d) Alveoli were permeabilized by 10-minute saponin infusions. Then arachidonate was infused into permeabilized (closed circles) and control (open circle) alveoli. Each point is the mean ± SEM of 4 experiments. Line was drawn by linear regression (P < 0.001).

AACOCF3 given by alveolar infusion 5 minutes after alveolar infusion of TNF-α terminated the endothelial [Ca2+]i response in less than 2 minutes (P < 0.05; Figure 7b), indicating that even after the onset of the endothelial response it was quickly abrogated by the cPLA2 inhibitor. Similarly to AACOCF3, alveolar infusion of MAFP, an inhibitor of both Ca2+-dependent PLA2 (cPLA2) and Ca2+-independent PLA2 (iPLA2), blocked endothelial responses to alveolar TNF-α (P < 0.05). However, BEL, which inhibits iPLA2, had no inhibitory effect on the endothelial [Ca2+]i response (n = 4 each; not shown).

Endothelial responses to alveolar infusion of TNF-α were not blocked by preinfusing alveoli with indomethacin (a cyclooxygenase blocker), MK886 (a 5-lipoxygenase–activating protein inhibitor), or WEB 2170BS (the platelet-activating factor receptor antagonist) (Figure 7c), suggesting that these mechanisms were not essential to the observed responses. However, in permeabilized alveoli, arachidonate infusion induced concentration-dependent increases of endothelial [Ca2+]i (P < 0.05; Figure 7d). Hence, arachidonate induced endothelial responses from the alveolar aspect of the capillary. No arachidonate effects occurred in nonpermeabilized alveoli. These findings were replicated by intra-alveolar linoleate (10 μM), which also caused endothelial [Ca2+]i increases in capillaries adjacent to permeabilized, but not nonpermeabilized, alveoli (P < 0.05, n = 4; not shown).

P-selectin.

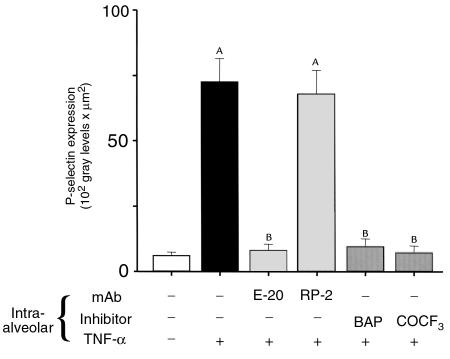

Endothelial [Ca2+]i increase may induce expression of the leukocyte-endothelial adhesion molecule P-selectin (18, 21). We quantified P-selectin expression in intact venular capillaries using our previously described methods (21). As shown in Figure 8, within 5 minutes of alveolar infusion of TNF-α, P-selectin expression increased approximately 10-fold above baseline. This increase was blocked by anti-TNFR1 mAb, BAPTA-AM, and AACOCF3. Neither infusion with Ringer’s solution nor the isotype-matched control mAb RP-2 had any observable effects.

Figure 8.

P-selectin expression in lung capillaries. Capillaries were stained for P-selectin expression 5 minutes after alveolar infusion as indicated. AACOCF3 (COCF3) or mAbs were given 10 minutes before TNF-α infusion; BAP (BAPTA-AM, 40 μM) was given 15 minutes before TNF-α infusion (1,000 U/mL). P-selectin expression was quantified as the product of mean fluorescence intensity and fluorescent area 1 minute after washout of unbound FITC-IgG with blood flow; n = 4 for each. AP < 0.05 vs. baseline (open bar). BP < 0.05 vs. TNF-α alone (black bar).

Discussion

We show here the existence of novel epithelial-endothelial signaling mechanisms in the lung. To summarize our findings: (a) Alveolar infusion of TNF-α increased endothelial [Ca2+]i. (b) Crosslinking alveolar TNFR1 replicated the response. (c) Immune inhibition of alveolar TNFR1 blocked the response. (d) The response was also blocked by alveolar injections of the intracellular [Ca2+]i chelator BAPTA-AM and cPLA2 blockers. (e) Alveolar infusion of TNF-α increased [Ca2+]i and activated cPLA2 in alveolar epithelial cells. (f) Alveolar infusion of TNF-α enhanced P-selectin expression in endothelial cells.

Our main conclusions are as follows. First, from finding (a), we conclude that an alveolar stimulus induced Ca2+ signaling in endothelial cells of perialveolar capillaries. Second, from findings [(b) and (c)] we conclude that the TNF-α effect followed ligation of alveolar TNFR1. Third, from findings (d) and (e) we conclude that the endothelial [Ca2+]i response was attributable to the epithelial [Ca2+]i increase and to activation of epithelial cPLA2. Fourth, from finding (f) we conclude that the endothelial response was proinflammatory. In addition, the gap-junction uncoupler heptanol failed to inhibit endothelial responses to alveolar TNF-α, thereby ruling out a gap-junctional basis for alveolocapillary signaling. Taken together, these findings are the first evidence that adjacent epithelial and endothelial cells of the alveolocapillary junction communicate Ca2+ signals through a receptor-mediated mechanism initiated in the epithelium.

Methodological considerations

Compartmental localization.

Alveolar leak of TNF-α given by intra-alveolar infusion could be ruled out because: (a) Intra-alveolar TNF-α–induced endothelial effects were blocked by intra-alveolar infusion of E-20, BAPTA-AM, or cPLA2 blockers. However, TNF-α given directly in capillaries still caused endothelial [Ca2+]i increases. These results indicate that TNF-α did not leak across the alveolar wall. (b) Intracapillary infusion of E-20 blocked endothelial [Ca2+]i increases in response to capillary TNF-α but not to alveolar TNF-α. Hence, again, intra-alveolar TNF-α did not ligate endothelial receptors. (c) FITC-IgG given by intra-alveolar injection was not detectable in the vascular space, showing that macromolecules did not rapidly diffuse across the alveolar epithelial barrier. (d) Capillary infusion of TNF-α did not induce [Ca2+]i transients in adjacent alveolar epithelial cells, indicating that TNF-α did not freely move between vascular and alveolar spaces.

Antibody ligation.

As far as we know, these are the first crosslinking data reported in situ. Crosslinking TNFR1 effectively mimics TNF-α–induced responses (29). We confirmed TNFR1 expression on the alveolar apical surface. Crosslinking resulted in epithelial and endothelial [Ca2+]i responses comparable to those generated by alveolar infusion of TNF-α. However, no responses were obtained either with the primary mAb alone or by replacing a nonspecific primary mAb in the crosslinking protocol. These findings affirm that TNF-α–induced responses require both ligation and aggregation of TNFR1.

Alveolocapillary [Ca2+]i oscillations.

A consistent feature in these experiments was that the epithelial and endothelial responses to alveolar TNF-α were different. Although mean [Ca2+]i increased in both cell types, high amplitude [Ca2+]i oscillations occurred only in epithelial cells, probably because only alveolar TNFR1 was ligated. Thus, enhanced endothelial [Ca2+]i oscillations could also be induced by directly ligating endothelial TNFR1 by capillary infusion of TNF-α. [Ca2+]i oscillations are attributed to Ca2+-dependent ligational properties of endosomal inositol triphosphate receptors (1, 4, 5, 30), as well as to oscillatory inositol triphosphate release (31). In most cell types, [Ca2+]i oscillations are relatively short-lived (30). In contrast, [Ca2+]i oscillations in our experiments were prolonged well in excess of the duration of TNF-α exposure. Hence, relatively brief periods of alveolar receptor ligation may generate sustained [Ca2+]i responses in alveolocapillary cells.

Interactions between TNF-α and cPLA2.

Our in situ assay for cPLA2 activation indicates a novel pulmonary role for cPLA2, namely its involvement in alveolocapillary signal propagation. Alveolar epithelial cells constitutively express cPLA2 (32). Both TNF-α and sustained [Ca2+]i increases activate cPLA2 (28, 33, 34). By immunofluorescence assay, we determined that intra-alveolar TNF-α induced membrane translocation and probably activation of cPLA2 in alveolar epithelium (25). Translocation was predominantly localized to the perinuclear region, the preferential site of agonist-stimulated phospholipid hydrolysis by cPLA2 (35).

Activation of cPLA2 was supported by the inhibitory effects of the cPLA2 blockers AACOCF3 and MAFP, which block both the Ca2+-dependent and the Ca2+-independent cytosolic isoforms (cPLA2 and iPLA2, respectively) (36, 37). Although nonspecific effects may occur, we point out that these agents blocked the endothelial, but not the epithelial [Ca2+]i responses to alveolar TNF-α. Because the agents did not block Ca2+ mobilization per se, we may rule out nonspecific effects in causing the inhibition of the endothelial [Ca2+]i responses. Interestingly, BEL, which selectively inhibits iPLA2 (36), had no inhibitory effect. Taken together, these results suggest that the observed endothelial responses resulted from activation of Ca2+-dependent cPLA2 in alveolar epithelium.

Products of cPLA2 activation.

Activation of cPLA2 yields arachidonate, prostaglandins, leukotrienes, and platelet-activating factor (38, 39). All of these products could potentially act as paracrine mediators. However, inhibitors of prostaglandin or leukotriene synthesis, or of the platelet-activating factor receptor, had no inhibitory effects on alveolocapillary signal propagation. Hence, to the extent that we can determine, these products did not convey the propagated signal. Although unidentified products may have contributed to the endothelial effect of alveolar TNF-α, cPLA2 specifically releases arachidonate from the sn-2 position of phospholipids (35). Therefore, the alveolocapillary signal may have been conveyed by arachidonate.

To the extent that arachidonate is secreted (37) and directly causes Ca2+ entry into cells (40, 41), it may have exerted a paracrine effect. We cannot directly confirm arachidonate secretion into the alveolocapillary space, but there is indirect support of this possibility. First, increases of endothelial [Ca2+]i induced by alveolar TNF-α were inhibited by external Ca2+ depletion, indicating that the response resulted from Ca2+ entry, consistent with the action of arachidonate. Second, alveolar arachidonate evoked endothelial [Ca2+]i increases in permeabilized alveoli. This mimics a possible vascular effect of basolaterally secreted arachidonate from alveolar epithelial cells.

We considered that arachidonate may also be secreted into the alveolar lumen by alveolar epithelial cells, and that the luminal fatty acid may cross the alveoli and act on adjacent capillaries. Although to our knowledge transalveolar fatty acid transport has not been confirmed, fatty acids are capable of crossing cell membranes (42), and when present in the alveolar lumen, they may cross the alveolar barrier by entering cells apically and exiting basolaterally. We tested this possibility for 2 polyunsaturated fatty acids, arachidonate and linoleate, given by intra-alveolar infusion. Both are known to increase [Ca2+]i in cultured cells (43). However, in intact alveoli, neither was apparently transported across the alveolar barrier at a sufficient level to evoke [Ca2+]i transients in the adjoining capillary. By contrast, in permeabilized alveoli, arachidonate and linoleate both induced endothelial [Ca2+]i increases. These findings indicate that an alveolar barrier to FFA transport existed, and that its elimination was necessary to allow sufficient action of alveolar FFAs on adjacent capillaries. The barrier may be attributable to transport limitations across cell membranes as well as to fatty acid metabolism within the cell. We interpret that to the extent that arachidonate released by alveolar epithelial cells caused the observed endothelial responses, its substantive effect resulted from basolateral rather than apical secretion.

P-selectin.

The goal of alveolocapillary signaling is to induce enhanced expression of leukocyte adhesion receptors in endothelial cells, in order to activate leukocyte influx. We tested this hypothesis in the context of P-selectin expression. Alveolar TNF-α enhanced endothelial P-selectin expression within 5 minutes. This response resembles the [Ca2+]i-dependent P-selectin expression we recently reported in pressure-stressed lung capillaries (21). Although platelets also express P-selectin, we previously reported that these capillaries are free of adherent platelets, and that P-selectin expression occurs in the presence of cell-free capillary infusion (21). Because endothelial P-selectin expression is a hallmark of early inflammation (44) and may precede neutrophil adhesion and emigration (19), we interpret that receptor-mediated alveolocapillary signaling evoked a rapid proinflammatory effect in perialveolar capillaries.

Inhibition of the P-selectin response permitted interpretation of the sequence of signaling events. Because alveolar E20 blocked all responses, we consider TNFR1 ligation to be the first step in the sequence. All intra-alveolar interventions such as BAPTA-AM and AACOCF3 that blocked epithelial responses also blocked endothelial [Ca2+]i increases and P-selectin expression. Hence, the epithelial responses were causal to endothelial signals that led to P-selectin expression. Although we did not directly determine kinetics along the signaling pathway, we determined that the epithelial [Ca2+]i increases and the resulting endothelial [Ca2+]i increases were detectable in 2 minutes, whereas epithelial cPLA2 activation and endothelial P-selectin expression were detectable in 5 minutes. These results agree with reported time courses of P-selectin upregulation and cPLA2 translocation (45, 46). Based on these considerations, we conclude that alveolar TNF-α caused rapid capillary expression of a leukocyte adhesion receptor. This resulted from sequential events in which alveolar TNFR1 ligation caused [Ca2+]i increase and cPLA2 activation in alveolar epithelium, which was followed by an increase of endothelial [Ca2+]i in adjacent capillaries.

Conclusions

Our findings provide the first direct evidence that alveoli communicate inflammatory signals to perialveolar capillaries. This intercompartmental signaling may be essential for effective host defense against airspace pathogens. Previous reports indicate that alveolar neutrophil influx after lung instillation of TNF-α occurs over a period of hours (7). Here we show that intra-alveolar TNF-α causes an endothelial proinflammatory response in minutes. This indicates that an alveolar stimulus is capable of immediately inducing alveolocapillary signaling, although the full scope of the response may develop over a much longer period. To summarize, TNF-α initiates ligation and clustering of the alveolar epithelial TNFR1, mobilization of epithelial [Ca2+]i, and the translocation and perhaps activation of epithelial cPLA2. This may, through basolateral arachidonate secretion from alveolar epithelial cells, account for endothelial [Ca2+]i influx and therefore enhanced expression of P-selectin. The extent to which these findings apply to other inflammatory ligands in the alveolus requires further investigation.

Acknowledgments

Anti–P-selectin mAbs RMP-1 and RP-2 were kindly provided by A. Issekutz. This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grants HL-57556, HL-36024, and HL-53625 to J. Battacharya. W.M. Kuebler was a research fellow of the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (1997–1999).

Footnotes

Wolfgang M. Kuebler’s current address is: Institute for Surgical Research, University of Munich, Marchioninistr. 15, 81366 Munich, Germany.

References

- 1.Nicod LP. Pulmonary defense mechanisms. Respiration. 1999;66:2–11. doi: 10.1159/000029329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strieter RM, Kunkel SL. Acute lung injury: the role of cytokines in the elicitation of neutrophils. J Investig Med. 1994;42:640–651. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ward PA. Role of complement, chemokines, and regulatory cytokines in acute lung injury. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996;796:104–112. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb32572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nelson S, et al. Compartmentalization of intraalveolar and systemic lipopolysaccharide-induced tumor necrosis factor and the pulmonary inflammation response. J Infect Dis. 1989;159:189–194. doi: 10.1093/infdis/159.2.189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wiener Kronish J, Albertine K, Matthay M. Differential responses to the endothelial and epithelial barriers of the lung in sheep to Escherichia coli endotoxin. J Clin Invest. 1991;88:864–875. doi: 10.1172/JCI115388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kurahashi K, et al. Pathogenesis of septic shock in Pseudomonas aeruginosa pneumonia. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:743–750. doi: 10.1172/JCI7124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koh Y, Hybertson BM, Jepson EK, Repine JE. Tumor necrosis factor induced acute lung leak in rats: less than with interleukin-1. Inflammation. 1996;20:461–469. doi: 10.1007/BF01487039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Skerret SJ, et al. Role of the type 1 TNF receptor in lung inflammation after inhalation of endotoxin or Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:L715–L727. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1999.276.5.L715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mulligan MS, Ward PA. Immune complex-induced lung and dermal vascular injury: differing requirements for tumor necrosis factor-α and IL-1. J Immunol. 1992;149:331–339. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ulich TR, et al. Intratracheal administration of endotoxin and cytokines. IV. The soluble tumor necrosis factor receptor type I inhibits acute inflammation. Am J Pathol. 1993;142:1335–1338. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lukacs NW, Strieter RM, Chensue SW, Widmer M, Kunkel SL. TNF-α mediates recruitment of neutrophils and eosinophils during airway inflammation. J Immunol. 1995;154:5411–5417. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bick RJ, et al. Temporal effects of cytokines on neonatal cardiac myocyte Ca2+ transients and adenylate cyclase activity. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:H1937–H1944. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1997.272.4.H1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Koller H, Thiem K, Siebler M. Tumour necrosis factor-α increases intracellular Ca2+ and induces a depolarization in cultured astroglial cells. Brain. 1996;119:2021–2027. doi: 10.1093/brain/119.6.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Corkey BE, et al. Ca2+ responses to interleukin 1 and tumor necrosis factor in cultured human skin fibroblasts. Possible implications for Reye syndrome. J Clin Invest. 1991;87:778–786. doi: 10.1172/JCI115081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schumann MA, Gardner P, Raffin TA. Recombinant human tumor necrosis factor-α induces calcium oscillation and calcium-activated chloride current in human neutrophils. The role of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:2134–2140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Boitano S, Dirksen ER, Sanderson MJ. Intercellular propagation of calcium waves mediated by inositol trisphosphate. Science. 1992;258:292–295. doi: 10.1126/science.1411526. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Osipchuk Y, Cahalan M. Cell-to-cell spread of calcium signals by ATP receptors in mast cells. Nature. 1992;359:241–244. doi: 10.1038/359241a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Datta YH, et al. Peptido-leukotrienes are potent agonists of von Willebrand factor secretion and P-selectin surface expression in human umbilical vein endothelial cells. Circulation. 1995;92:3304–3311. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.92.11.3304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Walter UM, Issekutz AC. Role of E- and P-selectin in migration of monocytes and polymorphonuclear leucocytes to cytokine and chemoattractant-induced cutaneous inflammation in the rat. Immunology. 1997;92:290–299. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2567.1997.d01-2314.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ying X, Minamiya Y, Fu C, Bhattacharya J. Ca2+ waves in lung capillary endothelium. Circ Res. 1996;79:898–908. doi: 10.1161/01.res.79.4.898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuebler WM, Ying X, Singh B, Issekutz AC, Bhattacharya J. Pressure is pro-inflammatory in lung venular capillaries. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:495–502. doi: 10.1172/JCI6872. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Skoff AM, Lisak RP, Bealmear B, Benjamins JA. TNF-α and TGF-β act synergistically to kill Schwann cells. J Neurosci Res. 1998;53:747–756. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-4547(19980915)53:6<747::AID-JNR12>3.0.CO;2-V. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Walter UM, et al. Characterization of a novel adhesion function blocking monoclonal antibody to rat/mouse P-selectin generated in the P-selectin deficient mouse. Hybridoma. 1997;16:249–257. doi: 10.1089/hyb.1997.16.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Grynkiewicz G, Poenie M, Tsien RY. A new generation of Ca2+ indicators with greatly improved fluorescence properties. J Biol Chem. 1985;260:3440–3450. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schievella AR, Regier MK, Smith WL, Lin L-L. Calcium-mediated translocation of cytosolic phospholipase A2 to the nuclear envelope and endoplasmic reticulum. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:30749–30754. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.51.30749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Daly CJ, Gordon JF, McGarth JC. The use of fluorescent nuclear dyes for the study of blood vessel structure and function: novel application of existing techniques. J Vasc Res. 1992;29:41–48. doi: 10.1159/000158930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Christ GJ, Spektor M, Brink PR, Barr L. Further evidence for the selective disruption of intercellular communication by heptanol. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:H1911–H1917. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.1999.276.6.H1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hoeck WG, Ramesha CS, Chang DJ, Fan N, Heller RA. Cytoplasmic phospholipase A2 activity and gene expression are stimulated by tumor necrosis factor: dexamethasone blocks the induced synthesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1993;90:4475–4479. doi: 10.1073/pnas.90.10.4475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Riches DW, et al. Cooperative signaling by tumor necrosis factor receptors CD120a (p55) and CD120b (p75) in the expression of nitric oxide and inducible nitric oxide synthase by mouse macrophages. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:22800–22806. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.35.22800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fewtrell C. Ca2+ oscillations in non-excitable cells. Annu Rev Physiol. 1993;55:427–454. doi: 10.1146/annurev.ph.55.030193.002235. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hirose K, Kadowaki S, Tanabe M, Takeshima H, andno M., II Spatiotemporal dynamics of inositol 1,4,5-triphosphate that underlies complex Ca2+ mobilization patterns. Science. 1999;284:1527–1530. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5419.1527. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Neagos G, Feyssa A, Peters-Golden M. Phospholipase A2 in alveolar type II epithelial cells: biochemical and immunologic characterization. Am J Physiol. 1993;264:L261–L268. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1993.264.3.L261. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wiegmann K, et al. Human 55-kDa receptor for tumor necrosis factor coupled to signal transduction cascades. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:17997–18001. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hayakawa M, et al. Arachidonic acid-selective cytosolic phospholipase A2 is crucial in the cytotoxic action of tumor necrosis factor. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:11290–11295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Peters-Golden M, Song K, Marshall T, Brock T. Translocation of cytosolic phospholipase A2 to the nuclear envelope elicits topographically localized phospholipid hydrolysis. Biochem J. 1996;318:797–803. doi: 10.1042/bj3180797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ackermann EJ, Conde-Frieboes K, Dennis EA. Inhibition of macrophage Ca2+-independent phospholipase A2 by bromoenol lactone and trifluoromethyl ketones. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:445–450. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.1.445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Balsinde J, Dennis EA. Distinct roles in signal transduction for each of the phospholipase A2 enzymes present in P388D1 macrophages. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:6758–6765. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.12.6758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nemenoff RA, et al. Phosphorylation and activation of a high molecular weight form of phospholipase A2 by p42 microtubule-associated protein 2 kinase and protein kinase 2. J Biol Chem. 1993;268:1960–1964. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tithof PK, Peters-Golden M, Ganey PE. Distinct phospholipases A2 regulate the release of arachidonic acid for eicosanoid production and superoxide anion generation. J Immunol. 1998;160:953–960. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Broad LM, Cannon TR, Taylor CW. A non-capacitative pathway activated by arachidonic acid is the major Ca2+ entry mechanism in rat A7r5 smooth muscle cells stimulated with low concentrations of vasopressin. J Physiol (Lond) 1999;517:121–134. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7793.1999.0121z.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shuttleworth TJ. Arachidonic acid activates the noncapacitative entry of Ca2+ during [Ca2+]i oscillations. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:21720–21725. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.36.21720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Abumrad N, Harmon C, Ibrahimi A. Membrane transport of long-chain fatty acids: evidence for a facilitated process. J Lipid Res. 1998;39:2309–2318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schaloske R, Sonnemann J, Malchow D, Schlatterer C. Fatty acids induce release of Ca2+ from acidosomal stores and activate capacitative Ca2+ entry in Dictyostelium discoideum. Biochem J. 1998;327:233–238. doi: 10.1042/bj3320541. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ley K, et al. Sequential contribution of L- and P-selectin to leukocyte rolling in vivo. J Exp Med. 1995;181:669–675. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.2.669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McEver RP, Beckstead KL, Moore KL, Marshall-Carlson L, Bainton DF. GMP-140, a platelet alpha-granule membrane protein, is also synthesized by vascular endothelial cells and is localized in Weibel-Palade bodies. J Clin Invest. 1989;84:92–99. doi: 10.1172/JCI114175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hirabayashi T, et al. Critical duration of intracellular Ca2+ response required for continuous translocation and activation of cytosolic phospholipase A2. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:5163–5169. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.8.5163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]