SUMMARY

Immunosuppression therapy following organ transplantation is a significant factor in the development and progression of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV)-induced post-transplant Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS). Switching from cyclosporine to the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin is reported to promote KS regression without allograft rejection. Examining the underlying molecular basis for this clinical observation, we find that KSHV infection selectively upregulates mTOR signaling in primary human lymphatic endothelial cells (LEC) but not blood endothelial cells (BEC), and sensitizes LEC to rapamycin-induced apoptosis. Viral transcriptome analysis revealed that while infected BEC display conventional latency, KSHV-infected LEC support a radically different program involving widespread deregulation of both latent and lytic genes. ORF45, a lytic gene selectively expressed in infected LEC, is required for mTOR activation and critical for rapamycin sensitivity. These studies reveal the existence of a unique herpesviral gene expression program corresponding to neither canonical latency nor lytic replication with important pathogenetic and therapeutic consequences.

INTRODUCTION

Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS), the most common neoplasm in untreated AIDS patients (Dezube, 1996), is an opportunistic tumor that can arise from endothelium infected with Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) (Moore and Chang, 1995). The disease presents as highly vascularized proliferative lesions, typically on the skin, often with accompanying inflammatory changes (Ganem, 2010). In immunocompetent hosts, KS is an indolent condition (Brooks, 1986), but is more widespread and aggressive in immune deficiency states, including organ transplantation and AIDS (Dezube, 1996).

The principal targets of KSHV infection in KS lesions are elongated “spindle” cells thought to be of endothelial origin because they express multiple endothelial markers (e.g. CD31, CD34, CD36) (Boshoff et al., 1995; Ensoli et al., 2001). Whether these cells originate from infection of lymphatic endothelial cells (LEC) or blood endothelial cells (BEC) has been controversial. The idea that KS is a malignancy of lymphatic endothelium gained popularity when spindle cells were found to stain for LEC-specific markers [vascular endothelial growth factor 3 (VEGR3), podoplanin, lymphatic vessel endothelial hyaluronan 1 (LYVE-1), and D2-40] (Weninger et al., 1999). However, subsequent studies showed that KSHV infection of primary endothelial cells alters the expression of endothelial markers in a way that may confound lineage assignment (Hong et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2004). For example, viral infection of BEC efficiently induces expression of PROX1 and other LEC markers (Hong et al., 2004). Conversely, KSHV infection of LEC can shift their host transcript profile to one exhibiting BEC-like characteristics (Wang et al., 2004). As such, the endothelial lineage from which KS is derived has remained a matter of debate.

Immunodeficiency is a major factor in the development of KS (Beral et al., 1990), and the growth of solid organ transplantation has led to a rise in cases of post-transplant KS. This has posed a dilemma for the treating physician: reduction or full withdrawal of immunosuppressive drugs can lead to KS tumor regression, but also enhances the risk of graft injury or loss. Recently, it has been documented in renal transplant recipients with post-transplant KS that switching their immunosuppression from traditional cyclosporine therapy to the mTOR inhibitor rapamycin leads to the regression of their KS lesions without allograft rejection (Stallone et al., 2005). Although biopsies of KS tumors show evidence of mTOR pathway activation (Stallone et al., 2005), it has been unclear if this activation is truly essential for KS cell survival, or if the therapeutic benefit of rapamycin in this setting is principally due it its reduced capacity for immune suppression. To better understand the therapeutic action of rapamycin in KS, we have examined the effect of KSHV infection on mTOR signaling and rapamycin sensitivity in primary microvascular LEC and BEC. Our results reveal striking and previously unanticipated differences in KSHV transcription for these two lineages that lead to selective mTOR signaling and rapamycin sensitivity in endothelial cells of lymphatic but not vascular origin. These phenotypes can be attributed to the expression of a specific viral gene, ORF45, only within the context of KSHV infection that is unique to the LEC lineage, thus providing a molecular link between KSHV infection and rapamycin sensitivity.

RESULTS

Differential rapamycin sensitivity of KSHV-infected LEC and BEC

In this work, we employ the recombinant virus rKSHV.219, which constitutively expresses green fluorescent protein (GFP) and a puromycin resistance gene (Vieira and O’Hearn, 2004). As such, cells latently infected with rKSHV.219 display both green fluorescence and selectability in puromycin. In addition, rKSHV.219 harbors a red fluorescent protein (RFP) gene under the control of a viral promoter that is only active during lytic replication. Primary dermal microvascular LEC and BEC were infected with rKSHV.219 and subjected to two weeks of puromycin selection to generate the two polyclonal, stably infected cell lines LEC.219 and BEC.219, respectively. Microscopic examination of both lines showed that elongated spindling is only evident with LEC.219 and is not exhibited by BEC.219 upon stable infection (Figure 1A, 4 top panels). Merged GFP+RFP images (bottom panels) in Figure 1A showed that all of the infected cells are stably carrying the rKSHV.219 episome (green) with what seems to be very low level RFP expression (yellow). Flow cytometry analysis of LEC.219 (Figure 1B) and BEC.219 (Figure S1B) confirmed the stable rKSHV.219 infection with 100% of the cells being GFP+ (left panels) along with little or no RFP signal above background (right panels). Another KSHV isolate, derived from a recombinant bacmid BAC16 (Brulois et al., 2012), behaved identically following infection of LEC (Figure S1), indicating that these phenotypic differences are not unique to rKSHV.219 and likely reflect the influence of endothelial lineage on infection.

Figure 1. Establishment of LEC.219 and BEC.219.

(A) Brightfield (4 top panels) and fluorescent (2 bottom panels) images of mock and stably infected primary dermal LEC and BEC were taken at 10X magnification on a Nikon Eclipse Ti-E fluorescence microscope. GFP signal (green) indicates stable rKSHV.219 infection and GFP+RFP (yellow) is a marker for cells undergoing lytic KSHV infection. (B) Flow cytometry analysis of GFP-expressing cells (GFP vs. FSC-H left panels) in LEC.219 determines the percentage of cells that are stably infected and the RFP signal (RFP vs. FSC-H right panels) is supposed to reflect lytic cells. See also Figure S1.

Figure 4. mTORC1 is activated by ERK2/RSK1 signaling to TSC2 in LEC.219 but not in BEC.219.

The phosphorylation status of relevant signaling pathways was determined by immunoblotting with indicated antibodies. (A) Western blots of the substrates of mTORC1 signaling, p70 S6K (that phosphorylates S6) and 4EBP1, in mock and stably infected (inf) LEC and BEC were performed. (B) The MAPK pathway (MEK/ERK/RSK) and PI3K/AKT pathway converge at TSC2 to regulate mTORC1 signaling. (C) PI3K/AKT signaling to TSC2 T1462 shows no contribution to the mTORC1 activation in LEC.219. (D) ERK2/RSK1 signals to TSC2 S1798 in LEC.219 without any contribution from upstream MEK1/2. See also Figure S3.

Next, we examined the effects of rapamycin treatment on each infected cell population. The growth curves of mock and stably infected LEC and BEC were plotted over a 3-day time course during treatment with either DMSO or 10 nM rapamycin (Figures 2A & B). Figure 2A shows that mock LEC displays only minor growth retardation when cultured in rapamycin (dotted blue line) versus DMSO (solid blue line). Interestingly, LEC showed a 2-fold reduction in growth rates when infected with KSHV (solid red line). However, when these cells were exposed to rapamycin, they showed a dramatic loss of growth; indeed, by Day 3 the infected cell mass in the rapamycin-treated LEC.219 culture was lower than it was at the onset of the experiment, suggesting that substantial cell death had occurred. By contrast, BEC cultures behaved very differently (Figure 2B): infected BEC grew nearly identically to uninfected BEC (solid lines), and both lines displayed comparable slowing of growth in the presence of rapamycin (dotted lines).

Figure 2. Rapamycin causes a growth phenotype in LEC.219 that is specific to rKSHV.219 infection.

Mock and stably infected primary dermal LEC (A) and BEC (B) were treated with either DMSO (solid lines) or 10 nM rapamycin (dotted lines) and their cell densities at Day 0, 1, 2, and 3 was determined by the SRB-based In Vitro Toxicology Assay Kit (Sigma) with their respective growth curves plotted above. Error bars represent the standard deviation from the mean (n=3).

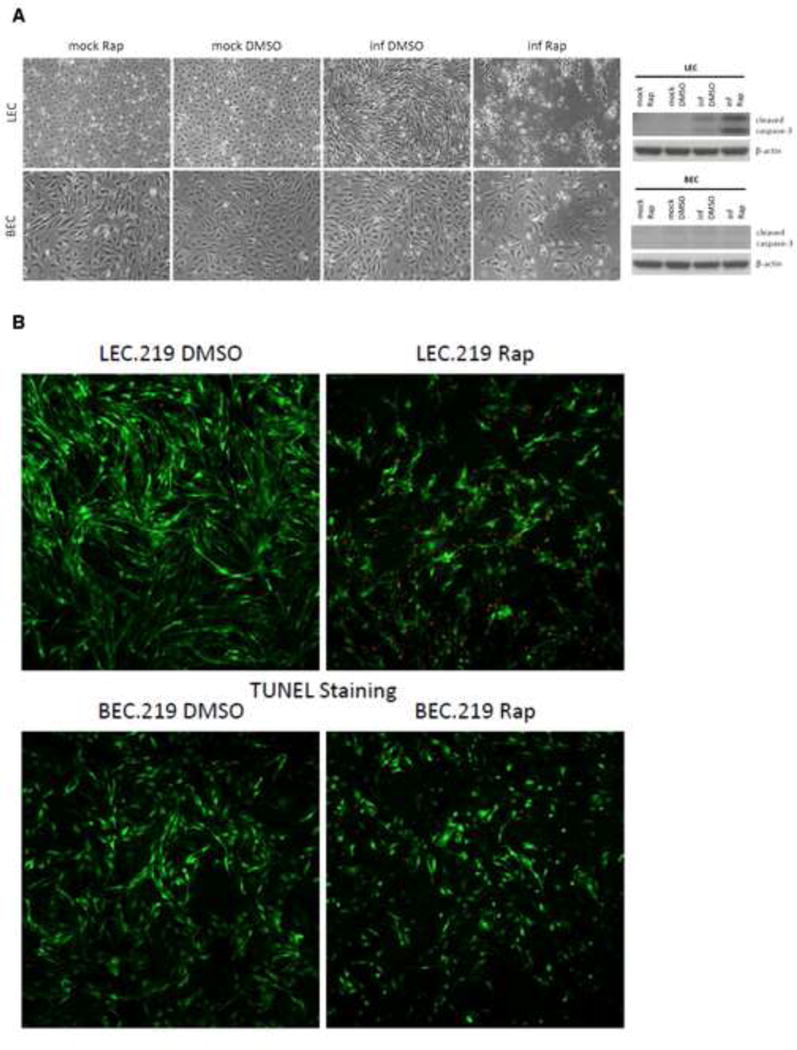

Brightfield images show that rapamycin treatment of LEC.219 clearly produced major cytopathic changes that were not seen in untreated LEC.219 (Figure 3A). Infected BEC did not display these morphologic changes, though they clearly grew to a lower cell density than their LEC counterparts, in keeping with the growth curves of Figure 2. To see if apoptosis was contributing to this phenotype, we examined these cultures by Western blotting for apoptotic marker cleaved caspase-3 (Figure 3A, right panels, and Figure S2). Infected LEC displayed slightly enhanced cleavage of caspase-3 over uninfected LEC, but this cleavage was dramatically increased following treatment with rapamycin. By contrast, infected BEC did not undergo apoptosis under either condition. These results were confirmed by TUNEL staining: infected BEC showed no TUNEL staining in either the presence or absence of rapamycin (Figure 3B, bottom panels); while infected LEC showed dramatic TUNEL staining after exposure to rapamycin (Figure 3B, top panels).

Figure 3. Rapamycin induces infection-specific apoptosis in LEC.219 but not in BEC.219.

(A) Brightfield images of mock and stably infected LEC and BEC treated with either DMSO or 10 nM rapamycin for 3 days were taken at 10X magnification on a Nikon Eclipse Ti-E fluorescence microscope. Cells were harvested and cell lysates were analyzed by Western blotting with the antibodies indicated. (B) Cells were treated with either DMSO or 10 nM rapamycin for 3 days and then processed for TUNEL staining. Infected cells are GFP-positive (green) while TUNEL staining is depicted in red. See also Figure S2.

mTORC1 is activated by ERK2/RSK1 signaling to TSC2 in LEC.219 but not in BEC.219

Since rapamycin targets the mTOR signaling pathway, we examined the status of this pathway in primary endothelial cells and its alterations by KSHV infection. mTOR signaling is known to control cell growth primarily by regulating cap-dependent translation and ribosome biogenesis through the phosphorylation of p70 S6K and 4EBP1, respectively, by the raptor-associated mTOR complex 1 (mTORC1) (Weber and Gutmann, 2012). Rapamycin binds cytosolic protein FK-binding protein 12 (FKBP12) and the resulting rapamycin-FKBP12 complex inhibits mTORC1 allosterically (Chung et al., 1992). mTORC1 signaling is reliably assayed by p70 S6K phosphorylation at residue T389 (Chung et al., 1992). While 4EBP1 phosphorylation can also indicate mTORC1 signaling status, this response is more variable in cultured cell lines (Choo et al., 2008).

To begin, we examined the state of mTORC1 signaling in LEC and BEC before and after stable infection with KSHV by Western blot analysis. As shown in Figure 4A, there was an increase in p70 S6K phosphorylation in LEC upon stable infection that leads to increased ribosomal protein S6 phosphorylation, while KSHV infection in BEC does not affect mTORC1 signaling. These changes were not mirrored by 4EBP1 phosphorylation, which is known to be a less reliable marker of pathway activation in many cultured cells (Choo et al., 2008). Similar to BEC, we saw no upregulation of p70 S6K or 4EBP1 phosphorylation following stable KSHV infection of two other lineages of large vessel-derived primary human endothelial cells, HUVEC (derived from umbilical vein) and HAEC (derived from aortic endothelium) (Figure S3A). Consistent with these observations, KSHV is not linked to proliferative lesions of large-vessel endothelium in vivo.

How might KSHV infection effect mTORC1 pathway activation in LEC? In most cells, mTORC1 is under negative regulation by the upstream tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), specifically the TSC2 subunit, which acts to control the activity of the mTORC1 regulatory G protein Rheb (Garami et al., 2003). TSC2 is, in turn, regulated by a number of signaling pathways. These include the AKT-dependent phosphorylation of TSC2 from the PI3K pathway along with ERK- and RSK-dependent phosphorylation of TSC2 from the MAPK pathway (summarized in Figure 4B) (Inoki et al., 2002; Ma et al., 2005; Potter et al., 2002; Roux et al., 2004). The best characterized regulator of TSC2 is phosphorylation by activated AKT (Huang and Manning, 2009), and some evidence suggests KSHV gene products can upregulate AKT (Sodhi et al., 2004; Tomlinson and Damania, 2004). However, we found no changes in AKT phosphorylation upon stable KSHV infection of LEC (Figure 4C and Figures S3B & C). Consistent with this, we observed a lack of an increase in TSC2 phosphorylation at residue T1462, the target of AKT (Figure 4C and Figure S3C). The consistent absence of T1462 phosphorylation upregulation in TSC2 strongly suggests that the PI3K/AKT pathway does not contribute to the activation of mTORC1 in LEC.219.

Recent work indicates that two signaling molecules from the MAPK pathway can also converge on TSC2: (i) activated ERK protein (typically activated by upstream MEK) can phosphorylate TSC2 at S664 (Ma et al., 2005); and (ii) activated RSK can phosphorylate TSC2 at S1798 (Roux et al., 2004). There is crosstalk between these regulators, since activated ERK can phosphorylate and activate RSK (see Figure 4B). Accordingly, examination of the phosphorylation state of each of these sites showed clear enhancement of phosphorylation of TSC2 at S1798 by KSHV infection, while phosphorylation at S664 was unchanged (Figure 4D and Figure S3C). This strongly suggests RSK as the regulator responsible for mTORC1 activation in stably infected LEC. To affirm this, we examined the state of RSK1 activation in LEC.219, by examining its phosphorylation at T573 (C-terminus) and T359+S363 (activation loop); these are targets of ERK phosphorylation that lead to RSK1 autophosphorylation at S380. As shown in Figure 4D, all of these sites underwent increased phosphorylation in LEC.219 but not BEC.219, confirming selective RSK activation in LEC by KSHV infection. Parenthetically, the phosphorylation of eIF4B, another downstream substrate of RSK1, was also increased in LEC.219 (Figure 4D).

These results imply that infected LEC should have upregulation of upstream MEK and ERK (Figure 4B). Indeed, when we examined the activation state of ERK in LEC.219 (Figure 4D), we discovered strongly enhanced phosphorylation of ERK2. However, neither ERK1 nor MEK displayed activation. Interestingly, there is no change in the ERK-dependent phosphorylation of TSC2 at S664, suggesting that whatever mechanism activates ERK2 may alter the substrate preferences of the enzyme in ways that are not yet understood. Similarly, although activated RSK was able to phosphorylate TSC2 at S1798 (Figure 4D), we did not observe phosphorylation of another RSK substrate, raptor (Carriere et al., 2008), and how this selectivity is achieved is also unclear. Nonetheless, the results of Figure 4 suggest that manipulation of mTORC1 signaling by KSHV is being effected through the release from inhibition by TSC2 that is induced by ERK2-mediated activation of RSK1.

These findings were all observed with LEC of dermal microvascular origin. We next asked if similar signaling properties existed among LEC and BEC harvested from lung (another frequent site of KS involvement). Figure S3D shows that LEC and BEC from lung behave identically to their dermal counterparts with respect to infection- induced ERK2, RSK1, and mTORC1 activation that lead to rapamycin sensitivity, indicating that these are properties of the lymphatic endothelial lineage rather than which tissue the cells are derived.

LEC.219 exhibits dysregulated lytic gene expression while BEC.219 is latent

Like all herpesviruses, KSHV can exist in two alternative transcriptional states upon infection: latency or lytic replication. In latency, viral gene expression is restricted to only a handful of viral genes with no production of viral progeny, while lytic replication involves the expression of all viral genes in a temporally ordered cascade that leads to the production of infectious virions and lysis of the host cell (Renne et al., 1996). Latency is the default pathway of in vitro KSHV infection in most cell types (Bechtel et al., 2003), but is reversible: lytic replication can be triggered in latently infected cells by treatment with chemicals such as phorbol esters and histone deacetylase complex (HDAC) inhibitors or by ectopic expression of the viral latent/lytic switch protein RTA (Replication and Transcription Activator) (Sun et al., 1998; Yu et al., 1999).

The selective activation of ERK2 and RSK1 by KSHV infection in LEC.219 is reminiscent of signaling resulting from the expression of KSHV ORF45 (Kuang et al., 2011; Kuang et al., 2008; Kuang et al., 2009). But ORF45 is known to be a lytic gene (Zhu et al., 1999), and it has generally been presumed that the default pathway of gene expression in cultured cells is latency (Bechtel et al., 2003). Accordingly, we examined the expression of ORF45 and several other lytic proteins in LEC.219 and BEC.219 by Western blotting. As shown in Figure 5A and Figure S4A, ORF45 was indeed selectively expressed during stable KSHV infection in LEC but not BEC. Moreover, other known lytic proteins, including RTA and K-bZIP, were also selectively turned on in LEC.219, while the latency marker LANA (ORF73) was comparably expressed in both cell lineages (Figure 5A and Figure S4A). Kaposin B, the product of a gene expressed at very low levels in latency but strongly induced in the lytic cycle, is also upregulated in LEC.219 and not detectable in BEC.219. Again, this pattern of expression was specific to LEC: stably infected HUVEC and HAEC resembled the latent BEC.219 cell line when blotted for these same markers (Figure S4B, middle and right panels). Moreover, LEC from lung showed the same pattern of dysregulated expression of viral lytic proteins like their counterparts from the dermis, while pulmonary BEC again showed strong restriction of lytic protein expression (Figure S4C).

Figure 5. LEC.219 exhibits extensive lytic gene expression while BEC.219 displays latent transcription.

(A) Expression of viral proteins was analyzed by Western blotting with indicated antibodies. (B) Viral gene expression in the stably infected lines was assessed with our custom KSHV tiling microarray. The microarray data is ordered by genome position and are displayed for 13,444 unique probes. Zero-transformation of infected hybridization was performed against uninfected hybridization and the color bar indicates the fold change relative to their mock-infected controls (log2 scale). The blue arrows point out specific hybridization signals. See also Figure S4.

To examine viral gene expression more comprehensively, the KSHV transcriptomes in stably infected dermal LEC and BEC were compared by transcript profiling with a custom genomic KSHV tiling microarray (Chandriani and Ganem, 2010; Chandriani et al., 2010). Consistent with the immunoblotting results of Figure 5A and Figures S4A, B, & C, the viral gene expression profiles in these stably infected lines are dramatically different: LEC.219 displays extensive transcription from across much of the viral genome (Figure 5B and Figure S4D, left and middle panels), including many known lytic genes, while transcripts detected in BEC.219 are highly restricted and correspond largely to known latency genes (e.g. ORF71-73) (Figure 5B and Figure S4D, left and middle panels). The BEC.219 pattern also includes RNAs from ORF75 and K15, as well as RNAs hybridizing at unannotated sequences antisense to the Kaposin and microRNA loci; the latter may be due to non-specific hybridization to repetitive sequences in these regions. The previously described transcripts originating from the puromycin/GFP/RFP cassette insertion site in rKSHV.219 were also observed in all stably infected samples and are thought to be artifacts of the inserted cassette (Chandriani and Ganem, 2010). Of note, the viral transcriptome of the HUVEC.219 and HAEC.219 cell lines more closely resemble that of BEC.219 (Figure 5B).

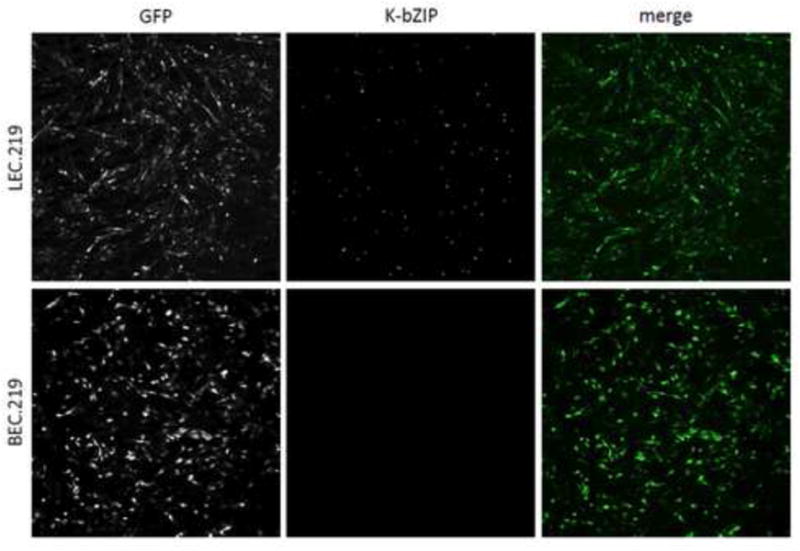

To clarify what fraction of the LEC.219 cell population are expressing these traditionally designated lytic markers, immunofluorescence assays (IFA) were performed on LEC.219 and BEC.219. K-bZIP staining of LEC.219 cells shows that the majority of the stably infected (GFP+) mass culture exhibits lytic protein expression while K-bZIP staining is completely absent in BEC.219 (Figure 6). This observation, coupled with the fact that LEC.219 cells were selected for continued growth in puromycin for 2 weeks and revealed little RFP expression from rKSHV.219 (Figure 1), affirms that, as suggested by the array pattern, the majority of the LEC.219 cells are not in the traditional lytic cycle that kills cells but are displaying a unique transcriptional program that allows expression of numerous lytic genes in the context of continued cell survival and proliferation. This is not to say that some cells in LEC.219 are not undergoing classical lytic replication. Examination of the culture supernatant does in fact reveal the presence of infectious virions, as judged by the ability to transfer GFP expression to naïve SLK cells (Figure S5). Quantitation of virus production from stably infected dermal and lung LEC and BEC (dLEC/dBEC and lLEC/lBEC) show supernatant viral titers of ~103 infectious units/mL from the stably infected lymphatic lines; this is over 1000-fold lower than the titer expected from a comparable number of lytically induced Vero or SLK cells (Myoung and Ganem, 2011a; Vieira and O’Hearn, 2004). Finally, the fact that the pattern of transcript accumulation in LEC.219 is visibly different from that in lytically induced iSLK.219 cells, as judged by examination on tiling arrays (Figure S4D, right panel), further supports that the predominant program in LEC.219 is not traditional KSHV lytic replication. Consistent with their latent gene expression profile, stably infected dermal BEC and lung BEC do not spontaneously produce any virus (Figure S5).

Figure 6. The majority of LEC.219 cells are displaying dysregulated lytic protein expression.

K-bZIP staining of LEC.219 (top panels) reveals that the majority of stably infected LEC cells are displaying dysregulated lytic protein expression while the lack of K-bZIP staining in BEC.219 (bottom panels) confirms its latency. The individual signal for GFP (left panels) and K-bZIP (middle panels) are in black and white while GFP and nuclear K-bZIP staining is green and blue, respectively, in the merged images (right panels). See also Figure S5.

KSHV ORF45 is required for mTORC1 activation in LEC.219 and plays a key role in rapamycin sensitivity during viral infection

Since ORF45 protein expression is readily detected in LEC.219 (Figure 5A and Figures S4A, B, & C), we set out to determine if this lytic gene is indeed responsible for the signaling observed in LEC during stable KSHV infection. First, ORF45 was stably expressed in primary dermal LEC by lentiviral transduction and the state of mTORC1 signaling in these cells were examined by immunoblotting. Figure 7A shows that isolated ORF45 expression phenocopies the signaling phenotype of stable KSHV infection in this lineage: mTORC1 is activated (increase in p-p70 S6K leading to increased p-S6), accompanied by evidence of activation of ERK2 and RSK1 and phosphorylation of TSC2 at T1798. Next we asked if siRNA mediated silencing of ORF45 in the context of stable KSHV infection would ablate mTORC1 activation (Figure 7B). LEC.219 cells were transfected with two different siRNAs directed against ORF45 to produce strong reductions in the levels of ORF45 protein in the cells compared to control siRNAs (Kuang et al., 2009). As expected, this resulted in loss of ERK2 and RSK1 activation, with loss of TSC2 phosphorylation at S1798 activation and corresponding loss of the signature of mTORC1 activation –increased phosphorylation of p70 S6K and accumulation of p-S6. These results firmly establish that the dysregulated expression of lytic gene ORF45 is the principal driver of mTORC1 activation in KSHV-infected LEC.

Figure 7.

KSHV ORF45 is required for mTORC1 activation in LEC.219 and plays a role in rapamycin sensitivity during viral infection(A) KSHV ORF45 was expressed in primary dermal LEC by lentiviral transduction and immunoblotting of mTORC1 signaling was performed. LEC transduced with the empty vector was used as the negative control. (B) Knockdown of ORF45 expression in LEC.219 was accomplished by transient transfection of 2 different ORF45 siRNAs. Experimental controls include an untransfected sample and transient transfection of 2 different negative control siRNAs. (C) LEC transduced with vector or ORF45 lentivirus was treated with either DMSO or 10 nM rapamycin (Rap) for 3 days. (D) Mock and stably infected LEC were each transfected with 10 nM Negative siRNA #2 and ORF45 siRNA #1 (2 days) and then treated with either DMSO or Rap for 3 days. See also Figure S6.

To explore the relationship between ORF45 expression and rapamycin sensitivity, uninfected primary LEC expressing only ORF45 and stably infected LEC.219 were treated with either DMSO or rapamycin and assayed for apoptosis. Figure 7D and Figure S6B show that, as expected, there is induction of apoptosis when LEC.219 is exposed to rapamycin. However, when ORF45 expression was knocked down in LEC.219, these infected cells became less sensitive to rapamycin-induced apoptosis, as reflected by significantly less cleaved caspase-3 (Figure 7D and Figure S6B) and cleaved PARP (Figure 7D). Thus, ORF45 expression is a key driver of rapamycin sensitivity in KSHV-infected LEC. However, when we examined uninfected LEC stably transduced with ORF45 expression, a strikingly different result was observed. As shown in Figure 7C, even though clear activation of mTORC1 signaling was evident (and 10 nM rapamycin is able to abolish this signaling), rapamycin treatment did not trigger enhanced apoptosis, as judged by immunoblotting for cleaved caspase-3 (no change in upper p19 band and absence of lower p17 cleavage product) and cleaved PARP (Figure 7C). ORF45-transduced BEC also behaved similarly (Figure S6A). Taken together, these results indicate while ORF45 expression in LEC.219 is necessary for rapamycin sensitivity, its expression alone in uninfected LEC is not sufficient for it.

DISCUSSION

The significance of mTORC1 signaling in KSHV biology came to the forefront when mTORC1 inhibitor rapamcyin was shown to contribute to the regression of KS lesions in renal transplant patients affected by post-transplant KS (Stallone et al., 2005). The initial aim of this study was to set up a relevant in vitro cell culture model to aid in the elucidation of the mechanism of this therapeutic effect. The key findings of this study are: (i) stable KSHV infection of primary LEC (but not BEC) sensitizes the infected cells to rapamycin-induced apoptosis; (ii) infected LEC exhibits mTORC1 activation while infected BEC does not; and (iii) this differential upregulation of mTORC1 signaling is a reflection of a much broader dysregulation of viral gene expression in LEC not present in BEC that is still consistent with cell survival. In this section, we discuss the significance of these findings and place them in the context of earlier work on KS and the biology of KSHV in particular and herpesviruses in general.

mTOR signaling and KSHV infection

Two prior studies have examined the impact of KSHV infection on signaling pathways that converge on mTOR, though these were not conducted in primary dermal microvascular endothelial cells, the cells most relevant to KS. One study described that an hTERT- immortalized HUVEC cell line stably infected by KSHV showed mTOR activation that was accompanied by an increase in PI3K and AKT phosphorylation (Wang and Damania, 2008). Ectopic expression of the viral proteins K1 and vGPCR have been shown to activate both PI3K and AKT (Sodhi et al., 2004; Tomlinson and Damania, 2004), and K1 mRNA was detected in this stably-infected HUVEC line (Guilluy et al., 2011). HUVEC are derived form the endothelium of large veins, which are not thought to be the progenitor of KS spindle cells. We have examined stable KSHV infection of HUVEC, but chose to use primary cells in our study, since immortalization is known to affect many signaling pathways. In these cells, we did not observe PI3K/AKT/mTOR activation (Figure S3A) and their viral gene expression profile did not show clear expression of K1 and vGPCR mRNAs (Figure 5B). We think it is likely that the differences observed between these studies are most probably referable to hTERT–mediated immortalization. Of note, we have also studied infection and mTOR signaling in HAEC, another lineage of endothelium derived from large vessels. These cells also failed to show infection-related upregulation of AKT and mTOR signaling (Figure S3A). The effect of KSHV infection on mTORC1 thus appears quite specific for the lymphatic endothelial lineage.

The other major published study of KSHV and mTOR was conducted in primary effusion lymphoma (PEL), a tumor of B cell origin that is also strongly linked to KSHV infection. Interestingly, PEL cell proliferation was strongly inhibited by rapamycin, both in vitro and after implantation subcutaneously or intraperitoneally in nude mice (Sin et al., 2007). The effect of rapamycin in these malignant B cells was largely cytostatic, in contrast to the apoptotic effects we observed in KSHV-infected LEC. These data are certainly compatible with KSHV induction of mTORC1 signaling in these B cells. However, since PEL lines are derived from human patients, no companion isogenic uninfected B cell lines exist; thus it is difficult to say with certainty whether in this lineage mTOR upregulation is directly caused by viral infection or is due to other signaling changes linked to the transformed phenotype. It is also difficult to make inferences about endothelial KS lesions using a B-cell model.

We did not observe AKT activation in LEC.219 (Figure 4C and Figures S3B & C) and saw no change in TSC2 phosphorylation at T1462 (Figure 4C and Figure S3C), the downstream substrate of AKT that is crucial for the regulation of mTORC1 signaling (Inoki et al., 2002; Potter et al., 2002). This suggests that AKT signaling is not the prime driver of mTORC1 activation in these cells. Rather, the phenotype appears to be related to activation of ERK/RSK signaling (Figure 4D and Figure S3C & D) – another pathway known to activate mTORC1 through phosphorylation of a distinct site on TSC2 (S1798) (Roux et al., 2004). We observed an imbalanced activation of ERK2 over ERK1, which is the characteristic signature of a recently described viral activity of ORF45 (Kuang et al., 2011; Kuang et al., 2008; Kuang et al., 2009), canonically described as an immediate-early lytic gene product that has been detected in KS lesions (Dittmer, 2003; Zhu et al., 1999). ORF45 was initially described as an inhibitor of IRF7 activation (Zhu et al., 2002), blunting the induction of type I interferon following infection. More recently, ORF45 has also been linked to selective upregulation of ERK2 phosphorylation, downstream of MEK, with resulting activation of RSK (Kuang et al., 2011; Kuang et al., 2008; Kuang et al., 2009), and here we show that this RSK1 activation has the expected consequence on mTORC1 activation. The striking reproduction of this unusual signaling phenotype in infected LEC, together with the direct demonstration of ORF45 expression in these cells, strongly points to ORF45 as the culprit here – an inference that was directly validated by siRNA-mediated ablation of ORF45 expression in LEC.219 (Figure 7B).

Stable KSHV infection of LEC not only triggers mTORC1 signaling but also makes these infected cells dependent on this pathway for their survival since the inhibition of this signaling by rapamycin triggers apoptosis. In this sense, KSHV-infected LEC can be said to be “addicted” to mTORC1 signaling. The burden of the expanded gene expression program in LEC.219 may be responsible for the difference in proliferation between mock and infected LEC (Figure 2A) and increased stress resulting from this deregulated expression may lead to enhanced dependence on mTORC1 signaling. Even though ORF45 is necessary for this addiction (Figure 7D and Figure S6B), its expression alone in uninfected LEC is not sufficient for it (Figure 7C). The addiction of LEC.219 to mTORC1 signaling appears to require the expression of other KSHV genes/ORFs. Presumably, other viral genes (and/or host genes regulated by them) may be cooperating with or linked to ORF45 expression during KSHV infection to make the cells dependent upon continued mTORC1 activation. The identification of these genes and the elucidation of their mechanisms will be important subjects for future investigation, and can be expected to shed considerable light on interactions of mTOR signaling with other cellular processes.

KSHV gene expression in different endothelial lineages

The textbook understanding of herpesvirus gene expression posits two states, latency and lytic replication. Nuanced variants on this scheme have been recognized– for example, the recognition that several different latency programs exist in EBV (Speck and Ganem, 2010), influenced in part by cell type and by other unknown factors. But all of these latency programs involve highly restricted gene expression and in no case is a clearly lytic gene expressed.

In the KSHV field, there has been significant suspicion that this simple model may not always be applicable. It has been suggested that traditional in vitro models of KSHV infection, in which latency is generally the default pathway, may not reproduce important features of viral gene expression relevant to KS (Mesri et al., 2010). There is good evidence that both latent and lytic gene products may play important roles in KS pathogenesis (Ganem, 2010; Mesri et al., 2010). While the effects of latent gene expression on cell survival and signaling have been much commented upon, there is considerable evidence linking lytic expression to KS development. For example, lytic replication leads to paracrine production of factors that can trigger an inflammatory and angiogenic microenvironment that is thought to be conducive to KS development (Cesarman et al., 2000). Lytic replication can also lead to a pool of virus from which new latently infected cells can be derived (Grundhoff and Ganem, 2004). Interruption of lytic replication in human hosts strongly reduces the development of new KS lesions (Martin et al., 1999). The virus-encoded vGPCR has been long suspected to possibly play an important role in KS pathogenesis, based on the observations that (i) mice expressing a vGPCR transgene display angioproliferative lesions with some features of KS (Sodhi et al., 2004) and (ii) cultured cells expressing vGPCR as a single gene display upregulation of VEGF expression (Bais et al., 1998). vGPCR is a potent signaling molecule that can upregulate many other molecules that impact on cell survival or inflammation and are implicated in KS, including NF-κB and p38 (Cannon et al., 2003). However, the vGPCR is classically annotated as a delayed-early lytic gene (Arvanitakis et al., 1997), and lytically infected cells strongly shut off host gene expression and also fail to proliferate (Glaunsinger and Ganem, 2004). Advocates of the vGPCR’s role in KS pathogenesis have proposed that perhaps an intermediate state of viral gene expression might exist in which sporadic lytic genes can be expressed in the absence of the full lytic program (Mesri et al., 2010), but to date evidence for such a cycle in human cells has been lacking. Mouse cells display widespread aberrant KSHV gene expression following infection (Austgen et al., 2012; Mutlu et al., 2007), but mice are nonpermissive hosts for KSHV (Austgen et al., 2012), and therefore the relevance of these observations to humans has been uncertain.

However, the present data indicates that during KSHV infection in primary human LEC, a genetic program with such formal properties exists and evidence of such unique gene expression in any herpesvirus infection in cells of its native host species is of significant importance. The spindling exhibited by LEC.219 but not BEC.219 in Figure 1A is the first clue that there may be a difference in viral gene expression between the two cell lines. Spindling is due to NF-κB activation, which can be mediated by several viral proteins (Cannon et al., 2003; Grossmann et al., 2006). Differential expression of one or more of these proteins may be responsible for this phenotypic difference. But the lack of RFP detected in both stably infected LEC and BEC (Figure 1A & B and Figure S1B) would otherwise indicate classic herpesviral latency in both cell lines, although the expression of RFP from rKSHV.219 has not always been a faithful marker for lytic replication (Myoung and Ganem, 2011b). This is why it was surprising to find that LEC.219 displays dysregulated expression of numerous lytic cycle genes, including RTA, K-bZIP, ORF45 and many others (Figure 5B and Figure S4D, left and middle panels) in the context of continued cell survival and proliferation. Possible evidence of this aberrant program in KS lesions has been suggested by the lack of significant correlation between the pattern of lytic mRNA levels in KS biopsy specimens to the pattern of lytic mRNAs in reactivated PEL cells, with the latter following the highly ordered cascade of gene expression needed for viral replication (Dittmer, 2011). But we emphasize that the existence of this unique gene expression program does not in itself constitute evidence for or against a role for the vGPCR in KS development. The fact that mouse endothelial precursor cells displaying dysregulated KSHV transcription can induce an angioproliferative lesion in mice establishes that ectopic lytic gene expression can have a pathologic phenotype with some features of KS (Mutlu et al., 2007). Our data now show that such a state can exist in human cells, and in fact selectively occurs in an endothelial lineage long suspected of playing an important role in KS.

Lastly, we note that KSHV gene expression is not the only feature affecting the phenotype of microvascular endothelium. Cheng et al (2011) have recently shown that KSHV-infected LEC “spheroid” cultures, 3-dimensional array of cells embedded in a fibrin matrix, promoted a Notch-induced endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition that is also observed (albeit at low frequency) in KS biopsies (Cheng et al., 2011). These conditions also further upregulated the limited set of lytic genes that was investigated. Ultimately, the tumorigenic potential of KSHV may be dependent on both tissue microenvironment and cell-type specificity.

Implications for human KS

We emphasize that these results, being the product of an in vitro system, cannot be rigorously used to produce an unambiguous model of KS histogenesis in vivo. Certainly, the facts that (i) transplant-associated KS responds to rapamycin, and (ii) KSHV-infected LEC are uniquely sensitized to this drug, are compatible with the idea that KS derives from lymphatic endothelium. However, this conclusion is not absolutely mandated by our findings. Earlier findings that KSHV infection itself reprograms the expression of host lineage markers continue to confound the issue of lineage origins of KS (Hong et al., 2004; Wang et al., 2004). But we note that a recent IHC study shows that in early (patch/plaque) KS lesions, cells with the properties of infected LEC (LANA+, LYVE1+,CD34-) represented ~20% of all spindle cells in the lesion – indicating that infected LEC are not rare in vivo, at least during the early stages of KS (Pyakurel et al., 2006). If these infected LEC exhibit similar viral gene expression to that observed in LEC.219, early KS hyperplasia could be promoted through both cell–autonomous and paracrine mechanisms mediated by these cells. In the later (nodular) stages, such cells were much less frequent (<3%). This could indicate that such cells are selected against (e.g. by cell-mediated immune responses) or are at a growth disadvantage (entirely consistent with their slower growth in culture upon infection; Figure 2A). It is also possible that these cells give rise to the later, more dominant cell type (LANA+ cells expressing both BEC and LEC markers) through reprogramming. Clearly, more work will need to be done to determine the role of infected lymphatic endothelium in the natural history of KS in vivo, but this will not be a simple task, given the absence any relevant animal models for this complex angioproliferative and inflammatory state.

Finally, we note that the fact that LEC can be sensitized to rapamycin-mediated killing by KSHV infection raises the possibility that the observed therapeutic effects of the drug in post-transplant KS may not be due solely to its reduced capacity for immune suppression. If so, then rapamycin and its congeners may find use in the treatment of other forms of KS, including the classical form unlinked to immune deficiency.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell culture

LEC, BEC, HUVEC, and HAEC were purchased from Lonza and cultured in EBM-2 media supplemented with either the EGM-2 MV bullet added for microvascular cells (LEC and BEC) or the EGM-2 bullet added for macrovascular cells (HUVEC and HAEC). SLK cell lines were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin-streptomycin (Invitrogen). Cells were treated with Hybri-Max DMSO (Sigma) and InSolution rapamycin (EMD Biosciences).

Virus preparation and establishment of stable infection

rKSHV.219 stocks were prepared from the iSLK.219 cell line and stable infection was established as described in the Supplemental Experimental Procedures (Myoung and Ganem, 2011a). All stably infected primary endothelial cell lines were selected and maintained with 0.25 μg/mL puromycin (Invivogen).

Flow cytometry analysis

Stably infected cells were subjected to flow cytometry analysis with a FACSCaliber or LSRII (BD Biosciences) and the resulting data was analyzed by FlowJo software. Cells were prepared for flow cytometry analysis by trypsinization and the subjected to fixation with 1% paraformaldehyde (PFA).

Viability assays

The Sulforhodamine B (SRB)-based In Vitro Toxicology Assay Kit (Sigma) was used for determining cell density and the In Situ Cell Death Detection Kit (Roche) was used for TUNEL staining. Both assays were performed according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

rKSHV.219 infection sensitizes LEC, but not BEC, to rapamycin-induced apoptosis

mTORC1 is activated in LEC.219 but not in BEC.219

LEC.219 exhibits dysregulated viral gene expression while BEC.219 is latent

mTORC1 activation and rapamycin sensitivity in LEC.219 requires KSHV lytic gene ORF45

Acknowledgments

We thank J. Myoung for providing the iSLK.219 cell line for the production of rKSHV.219, M. Holdorf for providing the transcriptional profile of latent and lytic iSLK.219, J. Vieira (University of Washington) for providing Vero.219 for the establishment of iSLK.219, and F. Zhu (Florida State University) for providing the iSLK.BAC16 cell line for the production of KSHV BAC16. Funding was provided by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, G.W. Hooper Foundation, and Novartis Institutes for BioMedical Research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Accession numbers

Microarray data are deposited in NCBI GEO under accession number

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental Information includes six figures and Supplemental Experimental Procedures that can be found with this article online at

References

- Arvanitakis L, Geras-Raaka E, Varma A, Gershengorn MC, Cesarman E. Human herpesvirus KSHV encodes a constitutively active G-protein-coupled receptor linked to cell proliferation. Nature. 1997;385:347–350. doi: 10.1038/385347a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austgen K, Oakes SA, Ganem D. Multiple defects, including premature apoptosis, prevent Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus replication in murine cells. J Virol. 2012;86:1877–1882. doi: 10.1128/JVI.06600-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bais C, Santomasso B, Coso O, Arvanitakis L, Raaka EG, Gutkind JS, Asch AS, Cesarman E, Gershengorn MC, Mesri EA. G-protein-coupled receptor of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus is a viral oncogene and angiogenesis activator. Nature. 1998;391:86–89. doi: 10.1038/34193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bechtel JT, Liang Y, Hvidding J, Ganem D. Host range of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus in cultured cells. J Virol. 2003;77:6474–6481. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.11.6474-6481.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beral V, Peterman TA, Berkelman RL, Jaffe HW. Kaposi’s sarcoma among persons with AIDS: a sexually transmitted infection? Lancet. 1990;335:123–128. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(90)90001-l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boshoff C, Schulz TF, Kennedy MM, Graham AK, Fisher C, Thomas A, McGee JO, Weiss RA, O’Leary JJ. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus infects endothelial and spindle cells. Nat Med. 1995;1:1274–1278. doi: 10.1038/nm1295-1274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brooks JJ. Kaposi’s sarcoma: a reversible hyperplasia. Lancet. 1986;2:1309–1311. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)91436-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brulois KF, Chang H, Lee AS, Ensser A, Wong LY, Toth Z, Lee SH, Lee HR, Myoung J, Ganem D, et al. Construction and Manipulation of a New Kaposi’s Sarcoma-Associated Herpesvirus Bacterial Artificial Chromosome Clone. J Virol. 2012;86:9708–9720. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01019-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon M, Philpott NJ, Cesarman E. The Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus G protein-coupled receptor has broad signaling effects in primary effusion lymphoma cells. J Virol. 2003;77:57–67. doi: 10.1128/JVI.77.1.57-67.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carriere A, Cargnello M, Julien LA, Gao H, Bonneil E, Thibault P, Roux PP. Oncogenic MAPK signaling stimulates mTORC1 activity by promoting RSK-mediated raptor phosphorylation. Curr Biol. 2008;18:1269–1277. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2008.07.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cesarman E, Mesri EA, Gershengorn MC. Viral G protein-coupled receptor and Kaposi’s sarcoma: a model of paracrine neoplasia? J Exp Med. 2000;191:417–422. doi: 10.1084/jem.191.3.417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandriani S, Ganem D. Array-based transcript profiling and limiting-dilution reverse transcription-PCR analysis identify additional latent genes in Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J Virol. 2010;84:5565–5573. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02723-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chandriani S, Xu Y, Ganem D. The lytic transcriptome of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus reveals extensive transcription of noncoding regions, including regions antisense to important genes. J Virol. 2010;84:7934–7942. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00645-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng F, Pekkonen P, Laurinavicius S, Sugiyama N, Henderson S, Gunther T, Rantanen V, Kaivanto E, Aavikko M, Sarek G, et al. KSHV-initiated notch activation leads to membrane-type-1 matrix metalloproteinase-dependent lymphatic endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition. Cell Host Microbe. 2011;10:577–590. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.10.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Choo AY, Yoon SO, Kim SG, Roux PP, Blenis J. Rapamycin differentially inhibits S6Ks and 4E-BP1 to mediate cell-type-specific repression of mRNA translation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:17414–17419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809136105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung J, Kuo CJ, Crabtree GR, Blenis J. Rapamycin-FKBP specifically blocks growth-dependent activation of and signaling by the 70 kd S6 protein kinases. Cell. 1992;69:1227–1236. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90643-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dezube BJ. Clinical presentation and natural history of AIDS—related Kaposi’s sarcoma. Hematol Oncol Clin North Am. 1996;10:1023–1029. doi: 10.1016/s0889-8588(05)70382-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmer DP. Transcription profile of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus in primary Kaposi’s sarcoma lesions as determined by real-time PCR arrays. Cancer Res. 2003;63:2010–2015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dittmer DP. Restricted Kaposi’s sarcoma (KS) herpesvirus transcription in KS lesions from patients on successful antiretroviral therapy. MBio. 2011;2:e00138–00111. doi: 10.1128/mBio.00138-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ensoli B, Sgadari C, Barillari G, Sirianni MC, Sturzl M, Monini P. Biology of Kaposi’s sarcoma. Eur J Cancer. 2001;37:1251–1269. doi: 10.1016/s0959-8049(01)00121-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ganem D. KSHV and the pathogenesis of Kaposi sarcoma: listening to human biology and medicine. J Clin Invest. 2010;120:939–949. doi: 10.1172/JCI40567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garami A, Zwartkruis FJ, Nobukuni T, Joaquin M, Roccio M, Stocker H, Kozma SC, Hafen E, Bos JL, Thomas G. Insulin activation of Rheb, a mediator of mTOR/S6K/4E-BP signaling, is inhibited by TSC1 and 2. Mol Cell. 2003;11:1457–1466. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(03)00220-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glaunsinger B, Ganem D. Lytic KSHV infection inhibits host gene expression by accelerating global mRNA turnover. Mol Cell. 2004;13:713–723. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(04)00091-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann C, Podgrabinska S, Skobe M, Ganem D. Activation of NF-kappaB by the latent vFLIP gene of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus is required for the spindle shape of virus-infected endothelial cells and contributes to their proinflammatory phenotype. J Virol. 2006;80:7179–7185. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01603-05. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grundhoff A, Ganem D. Inefficient establishment of KSHV latency suggests an additional role for continued lytic replication in Kaposi sarcoma pathogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2004;113:124–136. doi: 10.1172/JCI200417803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guilluy C, Zhang Z, Bhende PM, Sharek L, Wang L, Burridge K, Damania B. Latent KSHV infection increases the vascular permeability of human endothelial cells. Blood. 2011;118:5344–5354. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-03-341552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong YK, Foreman K, Shin JW, Hirakawa S, Curry CL, Sage DR, Libermann T, Dezube BJ, Fingeroth JD, Detmar M. Lymphatic reprogramming of blood vascular endothelium by Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Nat Genet. 2004;36:683–685. doi: 10.1038/ng1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang J, Manning BD. A complex interplay between Akt, TSC2 and the two mTOR complexes. Biochem Soc Trans. 2009;37:217–222. doi: 10.1042/BST0370217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inoki K, Li Y, Zhu T, Wu J, Guan KL. TSC2 is phosphorylated and inhibited by Akt and suppresses mTOR signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:648–657. doi: 10.1038/ncb839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang E, Fu B, Liang Q, Myoung J, Zhu F. Phosphorylation of eukaryotic translation initiation factor 4B (EIF4B) by open reading frame 45/p90 ribosomal S6 kinase (ORF45/RSK) signaling axis facilitates protein translation during Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV) lytic replication. J Biol Chem. 2011;286:41171–41182. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.280982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang E, Tang Q, Maul GG, Zhu F. Activation of p90 ribosomal S6 kinase by ORF45 of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus and its role in viral lytic replication. J Virol. 2008;82:1838–1850. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02119-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuang E, Wu F, Zhu F. Mechanism of sustained activation of ribosomal S6 kinase (RSK) and ERK by kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus ORF45: multiprotein complexes retain active phosphorylated ERK AND RSK and protect them from dephosphorylation. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:13958–13968. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M900025200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Chen Z, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Pandolfi PP. Phosphorylation and functional inactivation of TSC2 by Erk implications for tuberous sclerosis and cancer pathogenesis. Cell. 2005;121:179–193. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin DF, Kuppermann BD, Wolitz RA, Palestine AG, Li H, Robinson CA. Oral ganciclovir for patients with cytomegalovirus retinitis treated with a ganciclovir implant. Roche Ganciclovir Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1999;340:1063–1070. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199904083401402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mesri EA, Cesarman E, Boshoff C. Kaposi’s sarcoma and its associated herpesvirus. Nat Rev Cancer. 2010;10:707–719. doi: 10.1038/nrc2888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore PS, Chang Y. Detection of herpesvirus-like DNA sequences in Kaposi’s sarcoma in patients with and without HIV infection. N Engl J Med. 1995;332:1181–1185. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199505043321801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutlu AD, Cavallin LE, Vincent L, Chiozzini C, Eroles P, Duran EM, Asgari Z, Hooper AT, La Perle KM, Hilsher C, et al. In vivo-restricted and reversible malignancy induced by human herpesvirus-8 KSHV: a cell and animal model of virally induced Kaposi’s sarcoma. Cancer Cell. 2007;11:245–258. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.01.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myoung J, Ganem D. Generation of a doxycycline-inducible KSHV producer cell line of endothelial origin: maintenance of tight latency with efficient reactivation upon induction. J Virol Methods. 2011a;174:12–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jviromet.2011.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myoung J, Ganem D. Infection of primary human tonsillar lymphoid cells by KSHV reveals frequent but abortive infection of T cells. Virology. 2011b;413:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2010.12.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potter CJ, Pedraza LG, Xu T. Akt regulates growth by directly phosphorylating Tsc2. Nat Cell Biol. 2002;4:658–665. doi: 10.1038/ncb840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pyakurel P, Pak F, Mwakigonja AR, Kaaya E, Heiden T, Biberfeld P. Lymphatic and vascular origin of Kaposi’s sarcoma spindle cells during tumor development. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1262–1267. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renne R, Zhong W, Herndier B, McGrath M, Abbey N, Kedes D, Ganem D. Lytic growth of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (human herpesvirus 8) in culture. Nat Med. 1996;2:342–346. doi: 10.1038/nm0396-342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roux PP, Ballif BA, Anjum R, Gygi SP, Blenis J. Tumor-promoting phorbol esters and activated Ras inactivate the tuberous sclerosis tumor suppressor complex via p90 ribosomal S6 kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:13489–13494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0405659101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sin SH, Roy D, Wang L, Staudt MR, Fakhari FD, Patel DD, Henry D, Harrington WJ, Jr, Damania BA, Dittmer DP. Rapamycin is efficacious against primary effusion lymphoma (PEL) cell lines in vivo by inhibiting autocrine signaling. Blood. 2007;109:2165–2173. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-06-028092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sodhi A, Montaner S, Patel V, Gomez-Roman JJ, Li Y, Sausville EA, Sawai ET, Gutkind JS. Akt plays a central role in sarcomagenesis induced by Kaposi’s sarcoma herpesvirus-encoded G protein-coupled receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:4821–4826. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400835101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Speck SH, Ganem D. Viral latency and its regulation: lessons from the gamma-herpesviruses. Cell Host Microbe. 2010;8:100–115. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.06.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stallone G, Schena A, Infante B, Di Paolo S, Loverre A, Maggio G, Ranieri E, Gesualdo L, Schena FP, Grandaliano G. Sirolimus for Kaposi’s sarcoma in renal-transplant recipients. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:1317–1323. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa042831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun R, Lin SF, Gradoville L, Yuan Y, Zhu F, Miller G. A viral gene that activates lytic cycle expression of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:10866–10871. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.18.10866. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomlinson CC, Damania B. The K1 protein of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus activates the Akt signaling pathway. J Virol. 2004;78:1918–1927. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.4.1918-1927.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vieira J, O’Hearn PM. Use of the red fluorescent protein as a marker of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus lytic gene expression. Virology. 2004;325:225–240. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.03.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang HW, Trotter MW, Lagos D, Bourboulia D, Henderson S, Makinen T, Elliman S, Flanagan AM, Alitalo K, Boshoff C. Kaposi sarcoma herpesvirus-induced cellular reprogramming contributes to the lymphatic endothelial gene expression in Kaposi sarcoma. Nat Genet. 2004;36:687–693. doi: 10.1038/ng1384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Damania B. Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus confers a survival advantage to endothelial cells. Cancer Res. 2008;68:4640–4648. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-5988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber JD, Gutmann DH. Deconvoluting mTOR biology. Cell Cycle. 2012;11:236–248. doi: 10.4161/cc.11.2.19022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weninger W, Partanen TA, Breiteneder-Geleff S, Mayer C, Kowalski H, Mildner M, Pammer J, Sturzl M, Kerjaschki D, Alitalo K, et al. Expression of vascular endothelial growth factor receptor-3 and podoplanin suggests a lymphatic endothelial cell origin of Kaposi’s sarcoma tumor cells. Lab Invest. 1999;79:243–251. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y, Black JB, Goldsmith CS, Browning PJ, Bhalla K, Offermann MK. Induction of human herpesvirus-8 DNA replication and transcription by butyrate and TPA in BCBL-1 cells. J Gen Virol. 1999;80(Pt 1):83–90. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-1-83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu FX, Cusano T, Yuan Y. Identification of the immediate-early transcripts of Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J Virol. 1999;73:5556–5567. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5556-5567.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu FX, King SM, Smith EJ, Levy DE, Yuan Y. A Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesviral protein inhibits virus-mediated induction of type I interferon by blocking IRF-7 phosphorylation and nuclear accumulation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:5573–5578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082420599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.