Abstract

Hydrocele of the canal of Nuck is a rare cause of inguinal swelling in females. We present the case of a 9-year-old girl, who underwent omphalocele repair shortly after birth. She presented with a painless swelling in the right inguinal region; it was of a hard elastic consistency and ultrasound image showed an oval lesion containing fluid, located in the subcutaneous soft tissue. Removal of the lesion and histological examination of the surgical specimen confirmed cyst of the canal of Nuck.

Keywords: Ultrasound, Hydrocele, Canal of Nuck

Riassunto

L’idrocele del canale di Nuck è una rara causa di tumefazione inguinale nelle donne. Presentiamo il caso di una bambina di 9 anni, operata alla nascita per onfalocele, con una tumefazione nella regione inguinale destra non dolente, di consistenza duro-elastica, che all’ecografia appariva come una formazione ovalare a contenuto fluido localizzata nel contesto dei tessuti molli sottocutanei. L’asportazione della lesione e l’esame istologico hanno confermato la diagnosi di cisti del canale di Nuck.

Introduction

The most frequent causes of palpable inguinal masses in female patients include inguinal hernia, lymphadenopathy, Bartholin’s cyst, soft tissue tumor (lipoma, leiomyoma) and endometriosis of the round ligament [1–7]. In contrast, hydrocele of the canal of Nuck is rarely the cause of palpable inguinal masses in female patients. Failure of complete obliteration of an outpouching of the parietal peritoneum in the inguinal canal may result in hydrocele of the canal of Nuck. We present the case of a 9-year-old girl with a swelling in the inguinal region; she had undergone omphalocele repair shortly after birth. The elements of ultrasound (US) diagnosis and the various causes of inguinal swelling are discussed.

Case report

A 9-year-old girl was referred to our department of radiology due to a palpable mass in the right inguinal region, which had appeared 6 months earlier. The patient’s clinical history included prenatal US diagnosis of medium-sized omphalocele (2.5–5 cm) with herniation of some loops of the small intestine, treated by surgical positioning of the herniated viscera in the abdominal cavity and closure of the abdominal wall defect a few hours after birth.

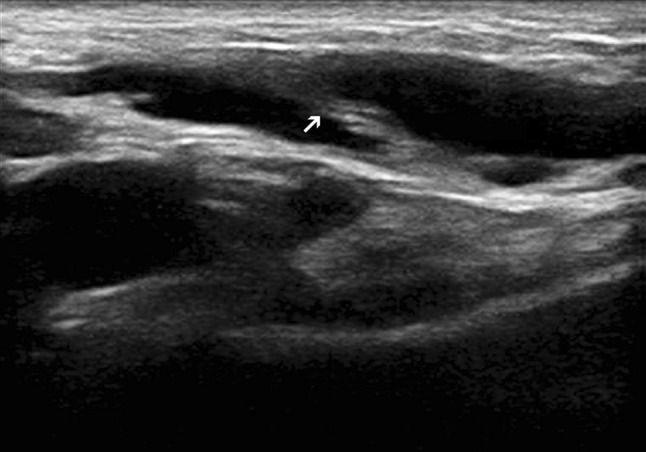

Physical examination revealed a painless inguinal swelling, irreducible and of a hard elastic consistency with no sign of inflammation of the overlying skin. US examination of the right inguinal region carried out on Esaote My Lab Twice using a linear probe (10–18 MHz) revealed a 9.5 × 45-mm oval-shaped mass with regular margins; it contained fluid and was located in the subcutaneous tissues; a thin hyperechoic septum was visible inside the lesion (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Longitudinal scan. Oval-shaped fluid-filled lesion with well-defined margins, located in the subcutaneous soft tissues of the right inguinal region. Inside the lesion a thin hyperechoic septum is visible (arrow)

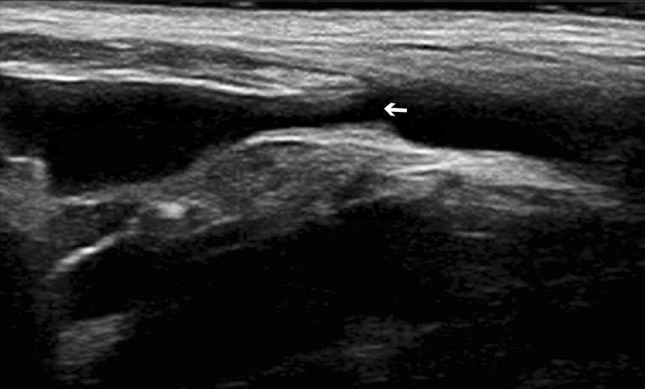

The apex of the mass was located along the inguinal canal (Fig. 2) and it was possible to trace communication with the peritoneal cavity (Fig. 3). The mass was irreducible at compression by the US probe. Color Doppler US revealed no vascularization of the wall or the internal septa. US outcome thus suggested hydrocele of the canal of Nuck. Removal of the lesion and histological analysis confirmed this diagnosis. Written informed consent was obtained from the patient’s parents for the publication of this case report and accompanying images.

Fig. 2.

Longitudinal scan. Communication between the cystic lesion and the abdominal cavity through the non-completely obliterated inguinal canal (arrow)

Fig. 3.

Longitudinal reconstruction of the entire structure. The proximal portion of the lesion communicates with the peritoneal cavity (asterisk); the distal portion extends into the labia majora (arrow)

Discussion

In females, the canal of Nuck is an outpouching of the parietal peritoneum extending along the round ligament into the inguinal canal in the fetus. It is the female equivalent of the processus vaginalis testis in males which extends along the testes in the descent from the lumbar region to the scrotum. Normally, it undergoes complete obliteration during the first year of life [1]. Incomplete obliteration creates a potential passageway for indirect inguinal hernia. Partial proximal obliteration may result in a sac containing serous fluid (hydrocele or cysts of the canal of Nuck).

Discrepancy between secretion and reabsorption of the secretory membrane that covers the vaginal process causes the swelling of the cyst and therefore the appearance of inguinal swelling. This discrepancy arises from a change in the lymphatic drainage which may be of traumatic, infectious or idiopathic origin [2, 3]. Clinically, hydrocele of the canal of Nuck appears as an irreducible, painless or mildly painful swelling in the inguinal area and labium. US is the easiest and most accurate imaging method for identifying a tubular or oval cystic lesion at the inguinal canal.

Some authors [1, 2] have described a comma-shaped tail extending from the lesion into the inguinal canal, while others describe the appearance as “a cyst within the cyst” [3] or a cystic mass with thin multiple septa [4, 5]. The graded compression technique allows observation of a fluid-filled canal which connects the cyst with the abdominal cavity [2]. Differential diagnosis of inguinal masses in female patients includes inguinal hernia (in which the fallopian tubes, ovaries, uterus and even ovarian cysts may slip into the hernial sac), lymphadenopathy, Bartholin’s cyst and soft tissue tumor (lipoma, leiomyoma) and endometriosis of the round ligament [1, 6, 7]. Other pathologies are rare, such as vascular abnormalities (arterial and venous aneurysms), ganglion cyst of the femoralcoxal joint or paraspinal abscess extending into the inguinal region [3].

Omphalocele and gastroschisis are the two most common congenital malformations of the abdominal wall. Omphalocele is defined as a midline malformation of variable size with protrusion of bowels and other organs, covered only by a thin transparent sac externally and internally by the peritoneum, Wharton’s jelly and amnion; the umbilical cord is attached to the sac. Gastroschisis is an abdominal wall defect, usually of small size, located immediately to the right of the normally inserted umbilical cord with herniation of the bowels and sometimes the genitourinary tract; there is no sac overlying the eviscerated bowel loops. Omphalocele is caused by failure of the bowels to return into the abdomen after normal herniation into the umbilical cord during the 6th to 10th week of embryological development [8]. Gastroschisis may be secondary to vascular insufficiency due to premature involution of the right umbilical vein or the right omphalomesenteric artery [9].

Omphalocele and gastroschisis are frequently associated with other congenital malformations: in 74.4 % of cases of omphalocele and 16.6 % of cases of gastroschisis [10]. Disorders associated with omphalocele include chromosomal abnormalities, non-chromosomal genetic syndromes (Beckwith–Wiedemann syndrome, Goltz syndrome, Marshall-Smith syndrome, Meckel–Gruber syndrome, Oto-palato-digital type II syndrome, CHARGE syndrome and fetal valproate syndrome), sequences of malformations such as ectopia cordis, body stalk anomaly, bladder exstrophy, cloacal exstrophy, complex omphalocele–exstrophy–imperforate anus–spinal defects (OEIS) and pentalogy of Cantrell [11, 12] as well as non-syndromic multiple congenital anomalies (MCA). Malformations of the musculoskeletal, urogenital, cardiovascular and central nervous systems are the most common birth defects in patients with omphalocele.

Conclusions

Hydrocele of the canal of Nuck is a rare disease [4], but this condition should be included in the differential diagnosis in female patients in the presence of a palpable swelling of the inguinal region. US examination requires familiarity with the normal and pathological US anatomy of the area. Few conditions can be confused with hydrocele of the canal of Nuck but it should be kept in mind that some types of malignant lymphomas may mimic cysts with fluid content. However, they are characterized by a strong vascularization [4] and Color Doppler should therefore always be performed in the presence of a cystic lesion.

Initially, the finding of a palpable inguinal mass in a girl who had undergone abdominal wall defect repair soon after birth raised suspicion of inguinal or adnexal hernia. However, the absence of hyperechoic elements suggesting the presence of omental tissue, intestinal loops or ovaries, ruled out this possibility.

To our knowledge, the association between hydrocele of the canal of Nuck and omphalocele repair has not previously been reported. At present, the absence of similar cases in the literature does not permit the assumption of a direct correlation between the two conditions.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.Park SJ, Lee HK, Hong HS, Kim HC, Kim DH, Park JS, et al. Hydrocele of the canal of Nuck in a girl: ultrasound and MR appearance. Br J Radiol. 2004;77(915):243–244. doi: 10.1259/bjr/51474597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yigit H, Tuncbilek I, Fitoz S, Yigit N, Kosar U, Karabulut B. Cyst of the canal of Nuck with demonstration of the proximal canal: the role of the compression technique in sonographic diagnosis. J Ultrasound Med. 2006;25(1):123–125. doi: 10.7863/jum.2006.25.1.123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Stickel WH, Manner M. Female hydrocele (cyst of the canal of Nuck): sonographic appearance of a rare and little-known disorder. J Ultrasound Med. 2004;23(3):429–432. doi: 10.7863/jum.2004.23.3.429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Safak AA, Erdogmus B, Yazici B, Gokgoz AT. Hydrocele of the canal of Nuck: sonographic and MRI appearances. J Clin Ultrasound. 2007;35(9):531–532. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ozel A, Kirdar O, Halefoglu AM, Erturk SM, Karpat Z, Lo Russo G, et al. Cysts of the canal of Nuck: ultrasound and magnetic resonance imaging findings. JUS. 2009;12(3):125–127. doi: 10.1016/j.jus.2009.05.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gokhale S. Sonography in identification of abdominal wall lesions presenting as palpable masses. J Ultrasound Med. 2006;25:1199–1209. doi: 10.7863/jum.2006.25.9.1199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Narci A, Korkmaz M, Albayrak R, Sözübir S, Güvenç BH, Köken R, et al. Preoperative sonography of nonreducible inguinal masses in girls. J Clin Ultrasound. 2008;36(7):409–412. doi: 10.1002/jcu.20422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ledbetter DJ. Gastroschisis and omphalocele. Surg Clin N Am. 2006;86:249–260. doi: 10.1016/j.suc.2005.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Christison-Lagay ER, Kelleher CM, Langer JC. Neonatal abdominal wall defects. Semin Fetal Neonatal Med. 2011;16(3):164–172. doi: 10.1016/j.siny.2011.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Stoll C, Alembik Y, Dott B, Roth MP. Omphalocele and gastroschisis and associated malformations. Am J Med Genet A. 2008;146A(10):1280–1285. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.32297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen CP. Syndromes and disorders associated with omphalocele (II): OEIS complex and pentalogy of Cantrell. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;46(2):103–110. doi: 10.1016/S1028-4559(07)60003-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen CP. Syndromes and disorders associated with omphalocele (III): single gene disorders, neural tube defects, diaphragmatic defects and others. Taiwan J Obstet Gynecol. 2007;46(2):111–120. doi: 10.1016/S1028-4559(07)60004-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]