Abstract

A 77-year-old woman was referred to our staff for evaluation of a “cystic” mass in the antecubital fossa. The recent medical history included surgical excision of a median-nerve schwannoma. The postoperative course had been uneventful. The sonographic examination revealed kinking of the brachial artery; color Doppler imaging showed aliasing at the level of the kink. The case illustrates the value of ultrasound in the diagnosis of fluid-filled lesions of the elbow, including those that are rare and unexpected

Keywords: Elbow, Kinking, Brachial artery

Riassunto

Il caso in esame si riferisce a una paziente, 77 anni di età, giunta alla nostra osservazione per la comparsa di una massa “cistica” a livello della fossa cubitale. In anamnesi vi era un intervento chirurgico per la rimozione di uno Schwannoma del nervo mediano, con decorso post-operatorio regolare. L’esame ecografico evidenziava kinking dell’arteria brachiale, il color-Doppler aliasing in corrispondenza della tortuosità. Abbiamo ritenuto il caso meritevole di pubblicazione per la rarità e perché conferma l’importanza dell’ecografia nel corretto inquadramento delle lesioni a contenuto liquido nel gomito, anche quando inusuali e inattese.

Introduction

Surgical access to the antecubital fossa may be required in the presence of tumors or nerve compression. The latter can be caused by fractures, ganglia [1], or neoplasms [2]. Surgery can be associated with early and late complications. The former are frequently vascular in nature and include hematomas caused by injury to the basilic, cephalic, or median cubital vein. Late complications are generally functional [3] and may include limitation of flexion/extension of the elbow caused by the formation of adhesions. One of the most important neurological complications is median nerve damage with symptoms of both sensory and motor deficits [4]. In cases of antecubital fossa tumors, there is also the risk of local recurrence at the surgical site.

Delayed vascular complications are less common, but they are reported from time to time. These phenomena are frequently caused by trauma; as postoperative complications, they are relatively rare. They generally consist of pseudoaneurysms of the brachial artery [5].

To our knowledge, brachial artery kinking has never been reported after surgical procedures involving the antecubital fossa. The apparent rarity of this complication prompted us to report the following case, which is being published with the informed consent of the patient.

Case report

The patient, a 77-year-old woman, was seen by our staff for evaluation of a “cystic” mass at the level of the antecubital fossa, which caused only mild limitation of elbow flexion. The history included surgical removal of a median-nerve schwannoma at the site of the mass about a year before. The procedure had not been associated with any intra- or post-operative complications and the post-surgical course had been uneventful.

The physical examination revealed a roundish, well-delimited, painless mass approximately 2 cm in diameter. It was firm-to-elastic in consistency, compressible, and non-tender on compression. The mass was not characterized by pulsation coincident with the arterial pulse.

A sonographic examination performed with a Toshiba Aplio 500 system (Toshiba Corporation, Japan) and a high-frequency transducer (18LX7, 7-18 MHz) revealed kinking of the brachial artery (Fig. 1), which formed a loop and then continued on its normal course into the deeper tissues of the arm (Fig. 2a–c). Color Doppler imaging confirmed the vascular nature of the mass, and spectral analysis demonstrated arterial flow with aliasing at the level of the tortuosity (Fig. 3a, b).

Fig. 1.

Diagram of the brachial artery kinking observed after surgical excision of a median nerve schwannoma

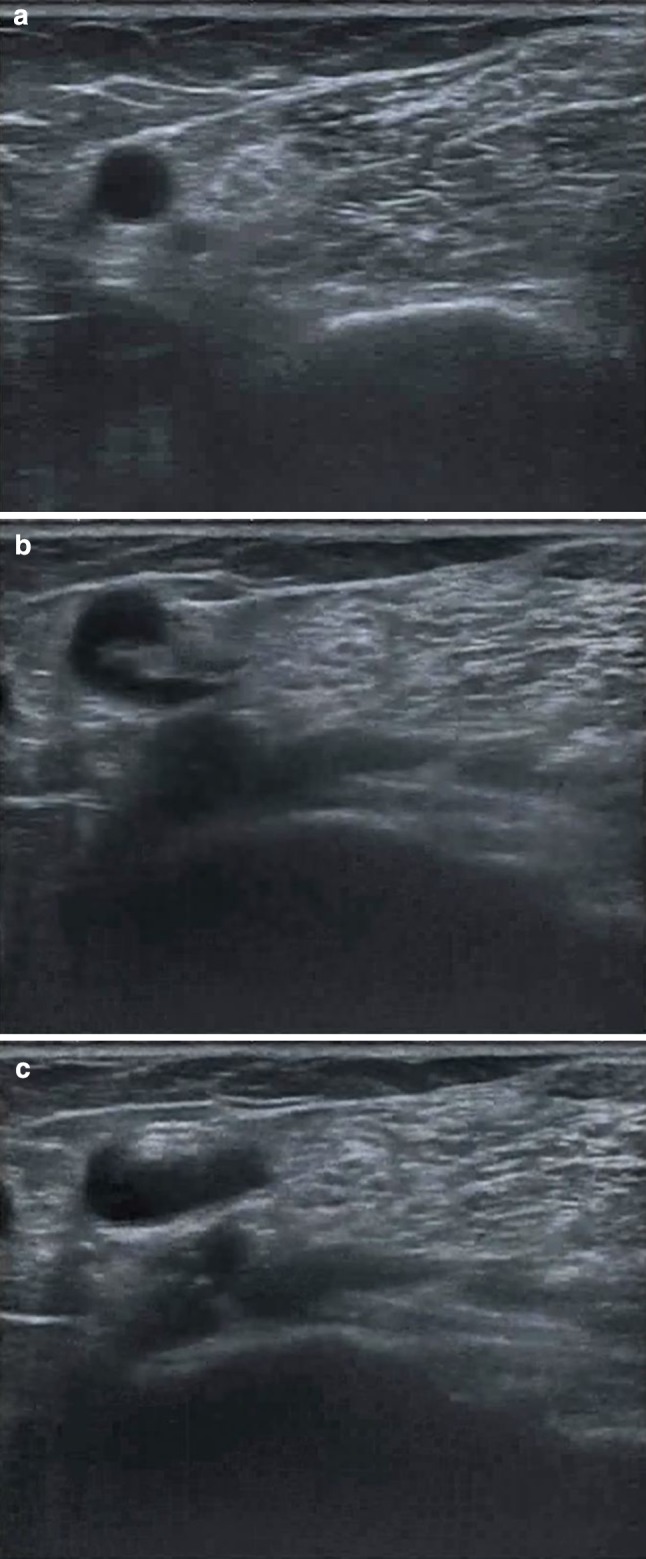

Fig. 2.

B-mode images reveal 360° torsion of the brachial artery. a Transverse scan of the proximal segment of the artery along its short axis. b Transverse scan of the middle segment of the artery reveals kinking. c Oblique transverse scan showing the normal course of the distal segment of the artery

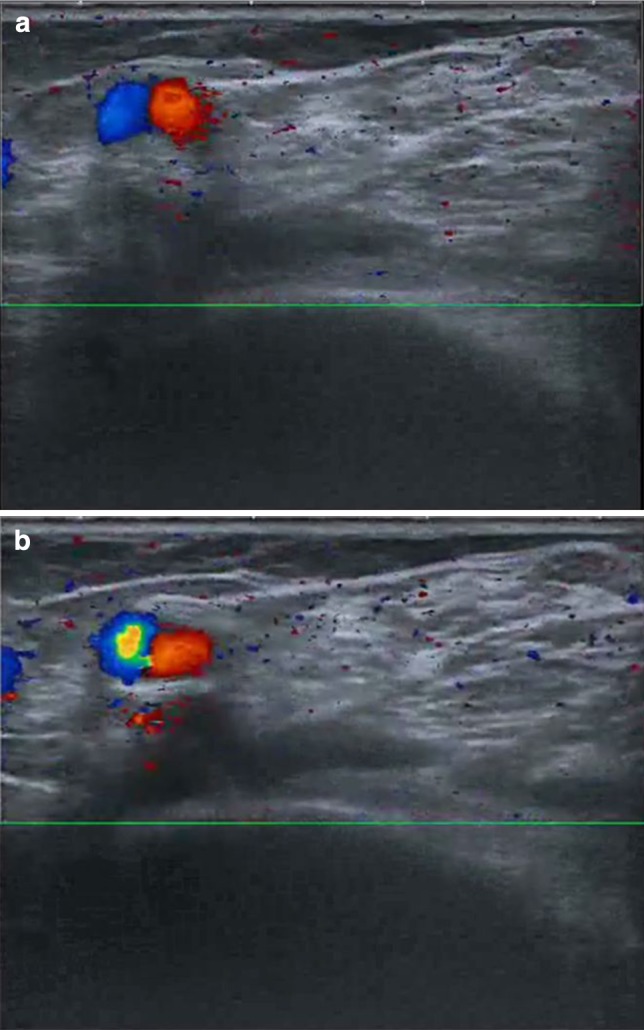

Fig. 3.

The color Doppler examination reveals two abrupt changes of direction in the course of the artery. a Transverse scan of the middle-proximal segments: change in direction characterized by the presence of red and blue signal in the same scan. b Transverse scan of the middle-distal segments: aliasing is seen at the level of the kink

Conclusions

Cystic masses at the level of the elbow generally involve the posterior and lateral compartments; anterior-compartment masses at the level of the antecubital fossa are less common. The antecubital fossa is delimited mainly by musculotendinous and aponeurotic structures: the supinator and brachial muscles, which form the floor of the fossa; the round pronator and brachioradial muscles, which represent the medial and lateral walls; and the bicipital aponeurosis, which forms the roof [6]. The antecubital fossa contains the distal tendon of the biceps brachialis, the median nerve, and the brachial artery. There are also three locoregional bursae: the cubital interosseous, the bicipitoradial, and the supinator bursae [7]. The presence in this fossa of an elastic mass can thus be caused by inflammation of one of these bursae (the brachioradial bursa in particular), a vascular alteration (brachial artery aneurysm), a periarticular lesion (ganglion), as well as benign and malignant tumors (hemangioma, synovial sarcoma).

The imaging work-up of these masses is based mainly on magnetic resonance and ultrasonography [8]. Ultrasound is considered the first-level study of choice for “cystic” lesions of the elbow because it is easy to perform, rapid, relatively low in cost, and widely available. The combination of sonographic and color Doppler imaging techniques can be used to distinguish solid and fluid-filled masses, but it also represents a simple, safe method for identifying vascular lesions. Thanks to its high spatial resolution, ultrasound is also useful for identifying the lesion’s relations with the joint capsule. The case described above confirms the importance of ultrasound in characterizing fluid-filled masses in the cubital fossa, including those that are relatively uncommon.

Conflict of interest

None.

References

- 1.McFarlane J, Trehan R, Olivera M, Jones C, Blease S, Davey P. A ganglion cyst at the elbow causing superficial radial nerve compression: a case report. J Med Case Rep. 2008;25(2):122. doi: 10.1186/1752-1947-2-122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jou IM, Wang HN, Wang PH, Yong IS, Su WR. Compression of the radial nerve at the elbow by a ganglion: two case reports. J Med Case Rep. 2009;3:7258. doi: 10.4076/1752-1947-3-7258. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Verhaar J, van Mameren H, Brandsma A. Risks of neurovascular injury in elbow arthroscopy: starting anteromedially or anterolaterally? Arthroscopy. 1991;7(3):287–290. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(91)90129-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zancolli ER, 3rd, Zancolli EP, 4th, Perrotto CJ. New mini-invasive decompression for pronator teres syndrome. J Hand Surg Am. 2012;37(8):1706–1710. doi: 10.1016/j.jhsa.2012.05.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moran D, Roche-Nagle G, Ryan R, Brophy D, Quinlan W, Barry M (2008) Pseudoaneurysm of the brachial artery following humeral fracture. Vasc Endovascular Surg 42:65 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Ellis H, Feldman S, Harrup-Griffiths W. The clinical anatomy of the antecubital fossa. Br J Hosp Med (Lond) 2010;71(1):M4–M5. doi: 10.12968/hmed.2010.71.Sup1.45982. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Berquist TH (2005) MRI of the musculoskeletal system, Italian 5th edn. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, New York, p 664

- 8.Draghi F, Danesino GM, de Gautard R, Bianchi S. Ultrasound of the elbow: examination techniques US appearance of the normal and pathologic joint. J Ultrasound. 2007;10:76–84. doi: 10.1016/j.jus.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]